Abstract

Background:

Food taboos among rural women have been identified as one of the factors contributing to maternal undernutrition in pregnancy.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to explore some of the taboos and nutritional practices among pregnant women attending antenatal care at a General Hospital in Dawakin Kudu LGA, Kano, Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study involving 220 pregnant women. Interviewer-administered structured questionnaire was used to interview the respondents, which showed various sociodemographic information, cultural nutritional processes, taboos of the community, and a 24 h food recall. The ages, parities, and gestational ages of the women were collated. Descriptive statistics was used. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Association between sociodemographic factors and nutritional practices and taboos was determined using Chi-square test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

At the end of the study, 200 participants (91%) gave complete information. Most of the women, 70% (140/200) were in the 20–39 years age range with mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 23.7 (6.1) years, mostly uneducated, 70% (140/200), and unemployed, 51% (102/200). Most of the women did a child spacing of 12–24 months, 62% (124/200) with mean (SD) child spacing interval of 26.32 (10.19) months. Gestational age at booking was mostly 13–26 weeks, 48% (96/200) with an average of 26.60 (8.01). Most of the women had 1–4 children, 54.5% (109/200) with mean (SD) of 2.47 (2.50). Most of the women agreed that they had adequate intake of oil, 86% (172/200), meat/fish, 92% (194/200), fruit/vegetables 56% (112/200), and had 3 meals/day 80% (152/200), and did not practice pica 83% (166/200). All of the women, 100% (200/200) believe that women should eat more during pregnancy in order to have healthy babies. They were mostly supported by their husbands, 53% (106/200) and less likely by the community, 34% (17/200). The nutritional practices and taboos of the women showed a statistically significant association with age, parity, and support received from husband and community (P < 0.05). Educational status is not associated with their nutritional practices and taboos.

Conclusion:

Although sociocultural indices of the respondents were poor, their intake of good nutrition and abstinence from nutrition taboos were satisfactory. Further studies are intended to objectively study the nutritional practices/taboos in pregnancy.

Keywords: Northwest Nigeria, Nutritional practices, Pregnant women, Taboos

Introduction

Food taboos among rural women have been identified as one of the factors contributing to maternal undernutrition in pregnancy.[1] Pregnant and lactating women in various parts of the world are forced to abstain from nutritious and beneficial foods.[2,3,4] In various studies, it was seen that pregnant women in various parts of the world are forced to abstain from nutritious foods as a part of their traditional food habits.[5,6]

Food taboo is a deliberate avoidance of a food item for reasons other than simple dislike from food preferences.[7] In some societies, food taboos are often meant to protect the human individual and the observation, for example, that certain allergies and depression are associated with each other could have led to declaring food items taboo that were identified as causal agents for the allergies.[7] It is believed that any food taboo, acknowledged by a particular group of people as part of its ways, aids in the cohesion of this group, helps that particular group maintain its identity in the face of others, and, therefore, creates a sense of belonging.[7] The avoidance of certain food items and incorrect knowledge regarding their benefits can deprive women from adequate nutrition, especially during the critical periods of pregnancy when it is of great benefit to the mother and her fetus.[8]

In the mid-west state of Nigeria, meat and eggs are not usually given to children, because parents believe it will make the children steal.[9] In some parts of Ishan, Afemai, and Isoko Divisions pregnant women avoid snails, whereas pregnant women of the Asaba Division are neither allowed to eat eggs nor drink milk, “because it is feared the children may develop bad habits after birth.”[9] Women tribals of the Ika division are forbidden to consume porcupine as that is thought to cause a delay in labor.[9]

A document prepared by the Food and Nutrition Unit in the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development indicated that milk, eggs, and goat's meat are the major food items prohibited during pregnancy in most parts of the country.[10] Another study by Beddada showed that milk and green vegetables are prohibited during pregnancy in many areas.[11] Major reasons given by the women as to why they avoid some foods include fear of difficult delivery as a result of big babies following the consumption of foods presumed to increase the size of the fetus.[12,13] Other reasons include fear of abortions and discoloration of the fetal body.[12]

Maternal nutrition during pregnancy has gained interest over the years due to the understanding that there is an increased physiologic, metabolic and nutritional demand associated with pregnancy. This has been regarded as an important determinant for fetal growth.[14] Infant size, such as birth weight and length, was reported to affect not only infant mortality but also childhood morbidity.[15,16]

Although severe undernutrition, which could lead to permanent changes in structure and metabolism in the fetus, is uncommon in developed countries, the imbalance or relative deficiency of nutrients could affect fetal growth.[17,18] Undernutrition is a common finding in developing countries and incidence of 10–40% has been reported in a rural community in Eastern part of Nigeria.[19]

Researchers from western parts of Nigeria have reported that 75% of pregnant women had inadequate dietary energy intake[20] and another from the Eastern part reported that 15% adhere to traditional beliefs or taboos about feeding practices in pregnancy.[21]

Women in developing countries suffer from nutritional deficiencies, but sociocultural factors including superstition and taboos that may be associated with malnutrition are not well studied. This study was therefore undertaken to explore some of the taboos and nutritional practices among pregnancy women attending antenatal care (ANC) at a General Hospital in Dawakin Kudu LGA, Kano, Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study involving randomly selected 220 pregnant women who attended antenatal clinic at the general hospital, Dawakin Kudu, Kano State between September 31, 2009 and March 30, 2010. Kano is the most populous state in Nigeria. Ethical approval and informed consent were obtained. Dawakin Kudu is a rural community in Kano State, Nigeria, and about 12 km from Kano metropolis. The women are housewives, but some engage in subsistent farming and petty trading. They engage in farming during the rainy season, poultry, and livestock rearing. Their method of farming is not mechanized as they resorted to local tools and feeds for their livestock's and poultry. The major crops grown include maize, millet, groundnuts, cowpea, cassava, and vegetable. The same piece of land is reused from year to year after application of manure.

Sample size was determined by using the formula for sample size calculation for descriptive studies as stated below:[22]

n = z2 P q/d2

(n = Sample size, z = Standard normal deviation = 1.96 at 95% Confidence limit, P = Prevalence rate = 15%, q = 1 − P = 1–15% =0.775, d = Error margin = 5%).

Documented prevalence of food taboo from a similar previous study was 15%.[21] This was substituted in the above equation giving a minimum sample size of 179. This was increased to 220 to account for drop-outs or nonresponse.

Interviewer-administered, validated, structured questionnaire was used to interview 220 respondents, and this showed various sociodemographic information, nutrient intake, and taboos of the community and a 24 h food recall. The 24 h food recall was conducted by requesting the respondent to mention specifically the various types of food she ate the past 24 h preceding the interview (These included the previous day meals). The questionnaires were administered in Hausa. Questions related to nutritional practices such as should a pregnant woman take some eggs, meats, fish, vegetables/fruits, and groundnuts. The participants were expected to answer either yes or no. In this survey, the opinion of the respondent was sampled using the questionnaire. Questions asked include did you eat adequate meal (the respondent's subjective assessment of her food intake as being enough in quantity and quality)?, did you eat three square meals (as adjudged as adequate meal including breakfast, lunch and dinner)?, did you eat adequate oil?, did you eat substances that are largely nonnutritive, such as paper, clay, metal, chalk, soil, glass, or sand?, did you eat adequate meat/fish?, and did you take adequate fruits/vegetables?. On food taboos, the respondents were asked what their views are about nutrition and pregnancy: Nutrition does not matter, pregnant women should eat less to avoid big babies, pregnant women should eat more to have healthy babies, and pregnant women should avoid animal-based food. The respondent also answered either yes or no as appropriate. The participants were selected by simple random sampling techniques. To participate in the study, a respondent should be 18 years and above, give an informed consent, and should have booked for ANC in the facility. All socioeconomic classes were included in the study. Their sociodemographic variables and responses on nutritional practices were collated. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Numbers, mean, standard deviation (SD), and simple percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Association between sociodemographic factors and nutritional practices and taboos was determined using Chi-square test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

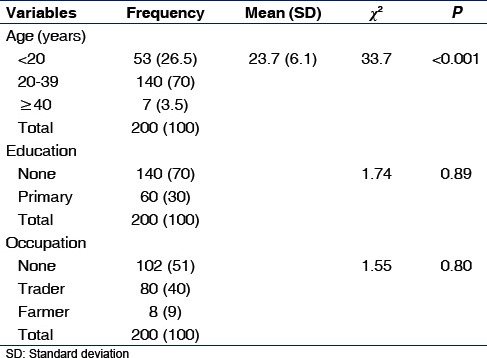

At the end of the study, 200 participants (91%) gave complete information. The women who dropped from the study did so because they felt the interview was taking much of their time. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Most of the women, 70% (140/200) were in the 20–39 years age range with mean (SD) age of 23.7 (6.1) years, mostly uneducated, 70% (140/200) and unemployed, 51% (102/200). Age showed a statistically significant association with the nutritional practices and taboos of the women (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, n=200

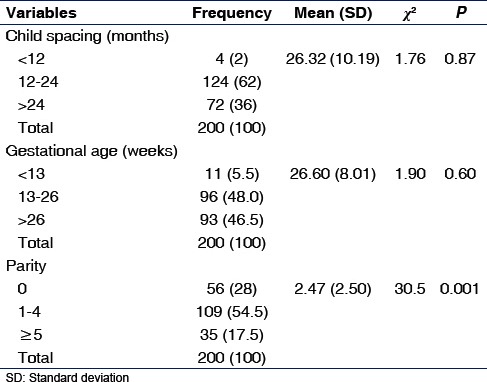

Table 2 shows the obstetrics characteristics of the participants. Most of the women did a child spacing of 12–24 months, 62% (124/200) with mean (SD) child spacing interval of 26.32 (10.19) months. Gestational age at booking was mostly 13–26 weeks, 48% (96/200) with mean (SD) of 26.60 (8.01) weeks. Most of the women had 1–4 children, 54.5% (109/200) with mean (SD) of 2.47 (2.50). Other than parity, the other parameters did not show any statistically significant association with the nutritional practices and taboos of the women.

Table 2.

Obstetrics characteristics, n=200

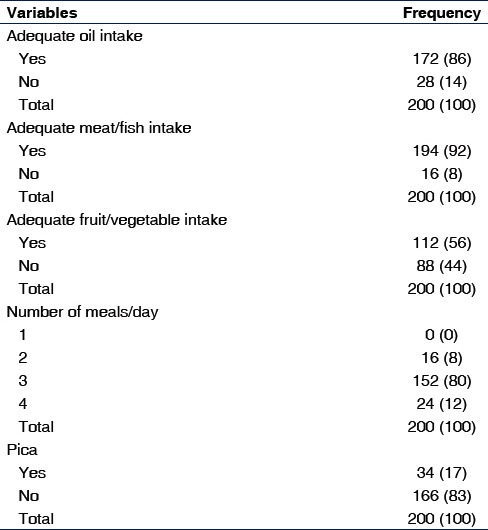

Table 3 shows nutrition Information. Most of the women agreed that they had adequate intake of oil, 86% (172/200), meat/fish, 92% (194/200), fruit/vegetables 56% (112/200), and had 3 meals/day 80% (152/200), and did not practice pica 83% (166/200).

Table 3.

Nutrition information, n=200

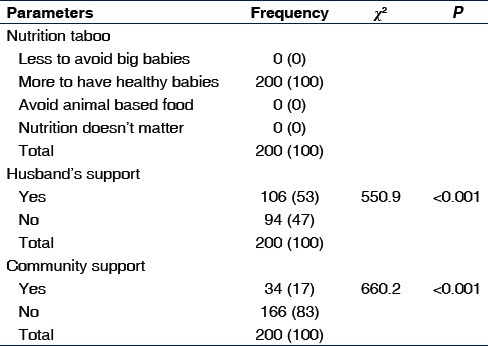

Table 4 showed the women perception of nutritional taboos and sources of support. All of the women, 100% (200/200) believe that women should eat more during pregnancy in order to have healthy babies. They were mostly supported by their husbands, 53% (106/200) and less likely by the community, 34% (17/200). The nutritional practices and taboos of the women showed a statistically significant association with support received from husband and community (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Nutritional taboos and support received by the pregnant women, n=200

Discussion

Undernutrition, especially during pregnancy, is prevalent in developing countries, and incidence of 10–40% has been reported in by some studies in Nigeria.[17,18,19]

The mean age, parity, and gestational age at booking (age of pregnancy at the time a women first attended ANC) reported in this study is comparable to 25.2 years, 3.6 and 7 months, respectively, reported in a previous study, although no correlation was found between nutritional practices/taboo among ages and parity.[23]

All the respondents believed that pregnant women should eat more to ensure healthy babies. The prevalence of food taboos observed in this study is therefore relatively low when compared to prevalence rates reported elsewhere in Africa.[21,24,25] It is thought that the relatively low prevalence of food taboos observed in this study is due to the better engagement in farming and availability of livestock products. Because most of the women were engaged in one form of trade or the other, it means that they may be able to afford some nutritious diet for themselves. Contrary to a previous study[23] that reported that food taboo correlated well with educational standards attained by the women, the present study did not report a high prevalence of food taboo despite the poor literacy status. In Nigeria, practically all women avoided livestock products such as meat, milk, and cheese.[24,25] This is one of the serious disadvantages of observing food taboos since the major sources of protein which are essential nutrients needed for the rapidly growing fetus are avoided. The present study in the contrary showed that these women took adequate meat and fish.

The high intake of meat, fish, fruit, and vegetable in this study was commendable. Some researchers have suggested that a dietary pattern characterized by high intake of vegetables, plant foods, and vegetable oils decreases the risk of preeclampsia.[26]

Palm oil/groundnut oil intake was also good among the respondents (86%). It has been shown that maternal Vitamin A status in the later part of pregnancy is significantly associated with fetal growth and maturation.[27] Therefore, red palm oil, a rich source of bioavailable Vitamin A, could be used as a diet-based approach for improving Vitamin A status in pregnancy.[27] The safety of red palm oil consumption has been established.[28,29] Evidence has been provided for the health benefits of red palm oil, including supporting cardiovascular health in both experimental animals and humans.[27,30]

Most of the respondents in this study did not practice pica. Pica is a deliberate desire for substances that are largely nonnutritive, such as paper, clay, metal, chalk, soil, glass, or sand. It is prevalent among pregnant women across Sub-Saharan African countries, such as Kenya, Ghana, Rwanda, Nigeria, Tanzania, and South Africa.[31,32] It is associated with medicinal treatment, spiritual and ceremonial behavior as well as chronic hunger, folk medicine, traditional cultural activities and social customs. The prevalence varies and may be as low as 0% or as high as 68%.[33] The prevalence of 17% reported in the current study is lower than 45.6%[27] or 74%[33] reported in other studies. The reason for this prevalence was unclear but may be due to religious or cultural reasons. The merits and demerits of pica have been extensively studied.[31,32,33]

The present study reports that 53% of the women received support from their spouses, whereas only 17% received any form of support from the community. The support was in the form of companionship, empathy, and assistance with chores and logistics received from her husband, friends, relatives, unions, or community. Pregnancy is typically considered a vulnerable period for women and one important risk factor affecting maternal well-being is a lack of social support.[34] Low social support is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight and preterm labor.[35] The nutritional practices and taboos of the women in the present study showed a statistically significant association with age, parity, and support received from husband and community (P < 0.05). Educational status is not associated with their nutritional practices and taboos. Previous studies have reported that educational or literacy level was associated with nutritional practices but did not test the effect of social supports.[36,37]

The limitation of this study is that use of questionnaires means that individual opinion was assessed, and these may not be objective.

Although the study was done among rural women who are largely uneducated, their nutritional practices and abstinence from nutrition taboos were commendable. They should, however, be advised to improve on their fruits and vegetable intake, and social support should also be advocated for these women. Further studies are intended to objectively study the nutritional status of these women.

Financial support and sponsorship

No financial support and sponsorship received by the author.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the technical support provided by Professor Hafeez Abubakar, a nutritional biochemist of Biochemistry Department of Bayero University, Kano.

References

- 1.Oni OA, Tukur J. Identifying pregnant women who would adhere to food taboos in a rural community: A community-based study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16:68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos-Torres MI, Vásquez-Garibay E. Food taboos among nursing mothers of Mexico. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21:142–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartini TN, Padmawati RS, Lindholm L, Surjono A, Winkvist A. The importance of eating rice: Changing food habits among pregnant Indonesian women during the economic crisis. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ankita P, Hardika K, Girija K. A study on taboos and misconceptions associated with pregnancy among rural women of Surendranagar district. Healthline. 2013;4:40–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manderson L, Mathews M. Vietnamese attitudes towards maternal and infant health. Med J Aust. 1981;1:69–72. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb135323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell J, Mackerras D. The traditional humoral food habits of pregnant Vietnamese-Australian women and their effect on birth weight. Aust J Public Health. 1995;19:629–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer-Rochow VB. Food taboos: Their origins and purposes. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szostak-Wegierek D. Importance of proper nutrition before and during pregnancy. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2000;4(3 Suppl 1):77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogbeide O. Nutritional hazards of food taboos and preferences in Mid-West Nigeria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27:213–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/27.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Nutrition Unit, Ministry of Planning and Economic Development. Social and cultural aspects of food consumption patterns in Ethiopia. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddada B. Traditional practices in relation to pregnancy and childbirth. In: Baashir T, Bannerman R, Rushwan H, Sharaf I, editors. Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children. Vol. 2. Cairo: WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office Technical Publication; 1982. pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leslie J, Pelto G, Rasmussen K. Nutrition of women in developing countries. Food Nutr Bull. 1988;10:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sood A, Kapil U. Traditional advice not always good. World Health Forum. 1984;5:149. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey KM, Barker DJ. Fetal nutrition and adult disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(Suppl 5):S1344–52. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1344s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutch L, Ashurst H, Macfarlane A. Birth weight and hospital admission before the age of 2 years. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:900–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.7.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hack M, Fanaroff AA. Outcomes of children of extremely low birthweight and gestational age in the 1990’s. Early Hum Dev. 1999;53:193–218. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews F, Yudkin P, Neil A. Influence of maternal nutrition on outcome of pregnancy: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1999;319:339–43. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fall CH, Yajnik CS, Rao S, Davies AA, Brown N, Farrant HJ. Micronutrients and fetal growth. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1747S–56S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1747S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ene-Obong HN, Enugu GI, Uwaegbute AC. Determinants of health and nutritional status of rural Nigerian women. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19:320–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojofeitimi EO, Ogunjuyigbe PO, Sanusi RA, Orji EO, Akinola A, Liasu SA. Poor dietary intake of energy and retinol among pregnant women: Implication for pregnancy outcome in South-West Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2008;7:480–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madiforo AN. Superstition and nutrition among pregnant women in Nwangele local government area of imo state. J Res Natl Dev. 2010;8:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox N, Hunn A, Mathers N. Sampling and Sample Size Calculation. United Kingdom: The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber; 2007. pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demissie T, Muroki N, Kogi-Makau W. Food taboos among pregnant women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1998;12:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ojofeitimi EO, Elegbe I, Babafemi J. Diet restriction by pregnant women in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1982;20:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(82)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebomoyi E. Nutritional beliefs among rural Nigerian mothers. Ecol Food Nutr. 1988;22:43–52. doi: 10.1080/03670244.1988.9991053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ademuyiwa MO, Sanni SA. Consumption pattern and dietary practices of pregnant women in Odeda local government area of Ogun state. Int J Biol Vet Agric Food Eng. 2013;7:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Samuelsen SO, Torjusen H, Trogstad L, Alexander J, et al. A dietary pattern characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oils is associated with reduced risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous pregnant Norwegian women. J Nutr. 2009;139:1162–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyanza EC, Joseph M, Premji SS, Thomas DS, Mannion C. Geophagy practices and the content of chemical elements in the soil eaten by pregnant women in artisanal and small scale gold mining communities in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manorama R, Chinnasamy N, Rukmini C. Multigeneration studies on red palm oil, and on hydrogenated vegetable oil containing mahua oil. Food Chem Toxicol. 1993;31:369–75. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manorama R, Rukmini C. Nutritional evaluation of crude palm oil in rats. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(4 Suppl):1031S–3S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.1031S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Rmalli SW, Jenkins RO, Watts MJ, Haris PI. Risk of human exposure to arsenic and other toxic elements from geophagy: Trace element analysis of baked clay using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Environ Health. 2010;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbett RW, Ryan C, Weinrich SP. Pica in pregnancy: Does it affect pregnancy outcomes? MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28:183–9. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngozi PO. Pica practices of pregnant women in Nairobi, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2008;85:72–9. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v85i2.9609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Larouche J, Brender W. Psychosocial predictors of labor/delivery complications and infant birth weight: A prospective multivariate study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21:137–48. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:715–25. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payghan BS, Kadam SS, Reddy RM. A comparative study of nutritional awareness among urban-rural pregnant mothers. Res Rev J Med Health Sci. 2014;3:95–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fouda LM, Ahmed MH, Shehab NS. Nutritional awareness of women during pregnancy. J Am Sci. 2012;8(7):494–502. [Google Scholar]