Abstract

The expectation of obstetrics is a perfect outcome. Obstetrics malpractice can cause morbidity and mortality that may engender litigation. Globally, increasing trend to litigation in obstetrics practice has resulted in high indemnity cost to the obstetrician with consequent frustration and overall danger to the future of obstetrics practice. The objective was to review litigations and the Obstetrician in Clinical Practice, highlighting medical ethics, federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO’s) ethical responsibility guideline on women's sexual and reproductive health and right; examine the relationship between medical ethics and medical laws; X-ray medical negligence and litigable obstetrics malpractices; and make recommendation towards the improvement of obstetrics practices to avert misconduct that would lead to litigation. Review involves a literature search on the internet in relevant journals, textbooks, and monographs. Knowledge and application of medical ethics are important to the obstetricians to avert medical negligence that will lead to litigation. A medical negligence can occur in any of the three triads of medicare viz: Diagnosis, advice/counseling, and treatment. Lawsuits in obstetrics generally center on errors of omission or commission especially in relation to the failure to perform caesarean section or to perform the operation early enough. Fear of litigation, high indemnity cost, and long working hours are among the main reasons given by obstetricians for ceasing obstetrics practice. Increasing global trend in litigation with high indemnity cost to the obstetrician is likely to jeopardize the future of obstetrics care especially in countries without medical insurance coverage for health practitioners. Litigation in obstetrics can be prevented through the Obstetrician's mindfulness of its possibility; acquainting themselves of the medical laws and guidelines related to their practice; ensuring adequate communication with, and consent of patients during treatment together with proper and correct documentation of cases. The supervision of resident-in-training, development and implementation of obstetrics protocol, and continuing medical education of obstetricians are also important factors to the prevention of litigation in obstetrics.

Keywords: Clinical practice, Litigation, Obstetrician

Introduction

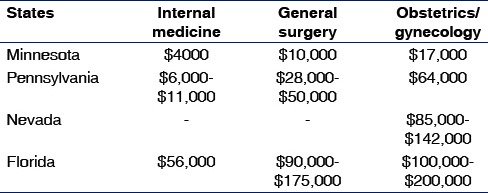

Obstetrics, its practice and outcome has over the years elicited a combination of hilarious excitement and painful sorrow depending on its endpoint. In the words of Chou.[1] “A perfect baby is the expectation of all parents, and a perfect outcome is the mission of obstetrics.” Maternal and perinatal deaths which incidentally occur in high rates in developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa constitute unsalutatory dreadful events to obstetricians, their patients, and indeed all communities alike.[2,3] It is the expectation of every pregnant woman being attended to by an obstetrician that she will end up with a perfect delivery and a perfect baby. Any outcome to the contrary engenders distress and disappointment and in some cases where deleterious outcome is traceable to negligence, perceived or real, outright litigation. Litigations commonly occur in obstetrics practice especially in developed countries and are powered by four major stakeholders in the medical-legal debate, viz: The pregnant patient and her environment – notably, husband, parents, relatives, friends, and the media; the health-care providers – doctors, nurses and paramedical workers; the insurance companies; and the legal practitioners.[1] Litigation in obstetrics is believed to be a result of a complex of events when malpractice (presumed or real) impacts on the attitude of pregnant women and their environment. A study conducted in United Kingdom reported that as high as 75% of senior obstetricians and gynecologists in the North Thames (West) Region had been involved in litigation.[4] Similarly, an article in Washington Post reported that 76% of Obstetrics/Gynecology (Obs/Gyns) professionals have been sued at least once and these doctors have one of the highest malpractice insurance rates of any medical profession.[5] The increasing rates of litigation in obstetrics have had the negative effect of increasing medical indemnity rates paid by obstetricians, thereby increasing their apprehension to obstetrics practice or even outright withdrawal from the practice.[6] Malpractice insurance cost as indicated by the United States Government Accountability Office varies from state to state, and between various specialties. Costs have consistently remained the highest for Obs/Gyn practice as shown in Table 1 for the three specialties of internal medicine, general surgery and Obs/Gyn, for four states of USA – Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Florida.[7,8]

Table 1.

Distribution by selected states in USA for costs of medical indemnity with respect to three specialties for 2009

The literature is virtually devoid of information on litigations in obstetrics practice in developing countries like Nigeria. Although a number of presentations has reported cases of medical malpractice and disciplinary actions taken by the medical controlling bodies.[9] This review highlights medical ethics, ethical codes including FIGO's ethical responsibilities in relation to women's sexual and reproductive health and right. It also examines the relationship among medical ethics and medical laws, X-rays medical negligence, and litigable obstetrics malpractices, and finally makes recommendation towards the improvement of obstetric practices to avert misconduct that would lead to litigations.

Method of Literature Search

The search of the literature involved a googling of the subject matter-“litigation and the obstetrician,” and “ethics in obstetrics” in the internet, which revealed several articles and briefs related directly or indirectly to the subject matter. In respect of litigation and the obstetrician, a total of 140 articles/publications was viewed from which 16 related to the subject matter were read and cited in this article viz presentation by Chou on a perfect baby and perfect outcome as expectation of the parent and Obstetrician, respectively.[1] Maternal/perinatal mortality;[3] UK/US study on Litigation and Obstetrics.[4,5] Increased rate in obstetrics, high indemnity cost and increasing aversion in obstetrics practice;[6,7,8] ethical code 12 and 13 and FIGO professional and ethical guidelines.[10,11] National commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral research/Belmot report;[12,13] medical negligence, lawsuit, and C-section are litigation in obstetrics issues;[14,15] obstetrics and litigation backlash.[16,17] Other sources of information on this article included; policy document from Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria on integrated maternal and newborn and child health strategy; world health organization and supranational agencies’ document on 2005 maternal mortality estimate; textbooks on ethics, human right, and medical law; handbooks and other monographs related to medical law and ethics; FIGO ethical professional and ethical responsibility guidelines concerning sexual and reproductive right and presentations made at the 45th scientific conference and annual general meeting of the society of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Nigeria.

Medical ethics, ethical codes and guiding principles of ethics

Medical ethics has been defined as the principles or norms that regulate the conduct of the relationships between medical practitioners and other groups with whom they come in contact in the course of their practice.[18] These include professional colleagues, other health professionals, the patient, the government, and other stakeholders in healthcare.

Code of Ethics is defined as a set of principles or rough guides to practice developed following serious breach of ethical standards.[19] For example, the Nuremberg code of 1947 and Helsinki Declaration of 1964 were developed to guide medical practice and research on human subjects, following inhuman experimentation conducted on human subjects.[20] The ethical codes of most nations of the world are related to the Hippocratic Oath of the 4th century B.C. sworn to by qualified medical doctors. The Code of Medical Ethics in Nigeria (COMIN) is a legal document that has been developed from the revision of the 1995 edition of the “Rules of Professional Conduct for Medical and Dental Practitioners in Nigeria.” These rules and regulations that guide the professional conduct of medical practitioners is a statutory provision contained in section 1; sub-section 2 (c) of the Medical and Dental Practitioners Act (CAP 221) Laws of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The COMIN has eight parts - Preamble and General guidelines, Professional conducts, malpractice, improper relationships with colleagues or patients, aspects of private medical or dental practice, self-advertisement and related offenses, convictions for criminal offences and Miscellaneous.[21] Every medical practitioner, obstetricians inclusive practicing medicine in Nigeria is expected to acquaint himself or herself with the provisions of this document so as to be properly guided to avoid medical malpractices in order not run afoul of the law.

Federation of gynecology and obstetrics ethical responsibilities on women's sexual and reproductive health[10]

The International FIGO plays a foremost role in the development of ethical, sexual, and reproductive rights guidelines that streamline professional obstetrics practice, through its committee on the ethical aspect of human reproduction and women's health.[22] In 2001, FIGO conducted a women sexual and reproductive right project in six countries – Nigeria, Sudan, Ethiopia, India, Pakistan, and Mexico. One of the most important components of this project is the development of a human right based code of ethics to guide Obs/Gyn professionals on women's sexual and reproductive healthcare. The consensus code of ethics which emerged from the project was presented at the 17th FIGO world Congress in Santiago Chile. There are three major thematic groupings of this ethical and professional responsibility guideline domiciled under professional competence, women's autonomy and confidentiality, and responsibility to the community.[11,22,23] The practicing Obs/Gyn professional is expected to be conversant with the provisions of this ethical and professional responsibility guidelines in order to not only improve professional care to obstetrics patient but also to protect self from inappropriate medical conduct that may engender litigations or disciplinary sanctions.

The guiding principles of ethics is in the main derived from the content of the Belmont report which was the submission, in 1979 of United States National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research that was established following the termination of the Tuskegee Alabama syphilis study carried out on indigent black Americans between 1932 and 1972. The setting-up of this commission was carried out along with the congressional passage of the National Research Act in 1974 essentially to guide and control issues related to human research and experimentation.[12,13] The Belmont Report provided an analytical framework to guide the resolution of ethical problems arising from research involving human subjects. The four key principles of bioethical analysis – respect for persons, beneficence, justice, and non-maleficence, have the first three contained in the Belmont report. Implicit in the principle of beneficence (do good) is non-–maleficence (do no harm) which became recognized as a distinct and fourth key principle. These four key principles of bioethical analysis constitute a consensus resolution of different bioethical orientations notably from the works of two American bioethicists - Tom Beauchamp and James Childress and the British expert - Gillon.[24,25] In addition to these four key principles, three others have been recognized in modern bioethical analysis – veracity, fidelity, and scientific validity.

There are two levels of occurrence of the principle of respect for person viz; autonomy of capable persons which upholds patient's right to voluntary informed consent, and choice based on comprehension of available options, for example, patient's right to family size determination, and protection of persons incapable of autonomy. There are three groups of persons falling into this category - the unconscious, the mentally sub-normal and the child–all of who require the protection of their autonomy, for example, the decision on the treatment of an unconscious pregnant woman. This protection requires either the presence of a living will especially in the case of the unconscious patient or the obtaining of consent from the surrogate or where not feasible a clergyman, or the Ethical Committee of a health institution or as a last resort, the judiciary. The overriding of patient's autonomy is referred to as medical paternalism. Strong paternalism is the overriding of the autonomy of a capable person and is not ethically permissible. While weak paternalism is the overriding of the autonomy of an incapable person which is permissible if performed for the overall well-being of a person. The principles of Beneficence refer to the ethical responsibility to do and maximize good, emphasizing what is in the best interest of the patient with respect to preventive and curative healthcare. The principles of Non–Maleficence refers to the ethical duty of the health practitioners to do no harm or cause pain to the patient as in the giving and suturing of episiotomy without local anesthesia in a parturient woman. The principles of Justice refer to the ethical responsibility to uphold fairness and equity in the discharge of healthcare to patients – irrespective of gender, race, social or economic status. It refers to the equitable distribution of potential benefits and risks. The ethical principles of veracity enjoin health practitioners to tell the truth-explaining the potential benefits and risks alike involved in whatever treatment being giving to, and procedure being carried out on the patient. The principles of fidelity refer to the ethical responsibility of the health practitioners to carry out whatever promises made to a patient in relation to activities for which he or she has been employed. The ethical principle of scientific validity enjoins the medical practitioners to ensure professional competence and scientific soundness in the conduct of medicare or research on patient.

Medical ethics and the law

Medical jurisprudence or medical law is defined as that aspect of the law which governs the relationship between the healthcare provider and the patient. The medical practitioner is bound by certain laws depending on the circumstances of his practice. These laws include: Civil and criminal laws of the land which apply to him as a citizen; the medical law which applies to him specifically as a medical doctor; codes of medical ethics which are guidelines that regulate the conduct of his practice; Public service rules and regulations which applied to medical doctors working in the public service; and military law for medical practitioners serving in the armed forces.[10,12,26] Legal values and ethical principles, usually, complement each other and assist to uphold the medical rights of patients. Discordance, however, does occur occasionally between ethical values and valuations compared to legal principles and valuations. For example, while the apartheid policy was considered to be legal in South Africa some years ago, the practice of segregation on the basis of race and color was adjudged to be ethically unacceptable.[14] Similarly, some countries uphold the legality of nontherapeutic abortion which was considered to be ethically unacceptable in yet other countries. Legal judgments may be upheld in technical grounds which do not apply in respect of ethical considerations. In general, when the provisions of the law clashes with the ethical principle, the provision of the law shall prevail. For example, the law court judge may order the disclosure of information obtained from a patient which ordinarily should constitute a breach of confidentiality.

Medical negligence

Medical negligence is said to occur when a health professional performs his duty in a health institution in such a manner that the avoidable harm befalls a patient.[15,26] In a strict sense, medical negligence occurs when a medical doctor omits to do what a reasonable doctor would do, or performs an act which a prudent and reasonable practitioner would refrain from doing and as a result of which some damage is done to the patient. For example, when a doctor leaves an abdominal towel or surgical instrument within the abdomen of a patient following surgery. Medical negligence is attributable to a doctor in relation to his patient only. This implies that a doctor is not considered to be negligent to a case that does not concern him, for example, a doctor may be at a scene of a road traffic accident and yet refused to do something, and He is not bound by the law to do something.

Duty of care refers to the legal requirement of a medical doctor possessing special knowledge and skills to attend to patients consulting for this medical expertise.[26] This implies that the medical practitioner should employ knowledge, expertise, and caution to ensure that undue harm does not befall his patient and this is irrespective of whether the said treatment is being given freely or on contractual terms. Duty of care often applies to persons whom the medical practitioner has had prior contact with as patient, although it may also apply to patients that he may have no prior contact with such as patients requiring emergency or call duty attention. The implication of this is that any doctor on call who fails to attend to his call duty and makes no arrangement for the coverage of such duty by another doctor is liable to account for any injuries or harm that may befall any patient attending during the period of the call duty.

When a doctor fails to perform up to the requisite standard of care and skill expected of him to the extent that injury or harm occurs to the patient, breach of duty of care is said to occur. There are three conditions expected to be present before a health professional can be said to be medically negligent:[26]

Existence of a duty of care to the plaintiff patient

Breach of the duty of care by the doctor

Damage or injury to the patient traceable to that breach of care.

Damage refers to loss or injury which the patient has suffered as a result of the breach of duty of care while claim of damage is compensation for what the patient has suffered. Damage may be physical or emotional–injury, pain, loss of earnings, reduction in life expectancy or quality-of-life and is, usually, quantified in monetary terms for compensation to be made possible. The onus of proof for medical negligence is, usually, on a balance of probabilities and lies on the patient in contradistinction to that in criminal cases where the proof is expected beyond all shadow of reasonable doubt. When every reasonable precaution has been taken in medical practice to avert harm to a patient and yet this occurs, duty of care has not been breached and, therefore, no negligence occurred. The situation is known in law as mere inadvertence and medical practitioner is not liable, for example, when a pregnant woman with premature rupture of fetal membrane at term undergoing cesarean section performed by duly competent physician throws up amniotic fluid embolus and dies on the table or when a pregnant patient embarking on cesarean section reacts to an anesthetic drug and dies-even before the caesarean section has commenced. A Medical negligence can occur in any of the three triads of medicare viz: Diagnosis, Advice/Counseling and treatment.

Diagnosis – related negligence

Medical negligence can occur when incorrect diagnosis is made in spite of the glaring presence of the signs and symptoms attributable to the ailment, for example, the inability of a medical practitioner to diagnose pre-eclampsia in a pregnant patient with obvious signs of hypertension, edema, and significant proteinuria, or when a woman with three previous cesarean sections, ordinarily requiring another C-section is allowed to go into labor-probably rupturing her uterus and dies.

Advice/counseling–related negligence

Negligence may occur when a patient has not been sufficiently advised or counseled on his/her medical condition to prevent harm from occurring, for example, a patient who had had a minor operation and requiring to stay in bed over a period of time, may if not counseled to do so, fall down from dizziness and sustained injuries, the hospital is liable of counseling-related negligence.

Treatment-related negligence

Treatment-related negligence can occur when harm occurs from treatment given without obtaining the consent of the patient or when a wrong medication has been administered for an ailment or even when a patient needing protection is neglected, for example, a woman who has had a minor gynecological surgery under anesthesia falls off from the theatre table and injured herself, because she was unattended to.

Litigations and the implication to obstetrics practice

Medical malpractice is said to occur when a registered medical practitioner carries out medical practice that does not conform to professionally accepted standard, methods or decorum as stipulated in the provisions of the code of medical ethics in the Medical and Dental Practitioners Act.[21] Professional medical malpractice should be brought to the attention of the Medical and Dental Council either by an aggrieved person, a medical colleague or any other means whatsoever for appropriate scrutiny and necessary action.[21] Medical malpractice constitutes medical negligence which can be litigious. Lawsuits in obstetrics generally center on errors of omission or commission, most common of which includes; Errors or omission in antenatal screening and diagnosis; Errors in ultrasound diagnosis; The neurologically impaired infant; Neonatal encephalopathy; Stillborn or neonatal death; Shoulder dystocia, with either brachial plexus injury or hypoxic injury; Vaginal birth after cesarean section; Operative vaginal delivery and training programs for residency and nursing.[15,16] The obstetricians’ liability exposure is, usually, more marked with faulty residency supervision and increased used of nurse midwives and nurse practitioners.[16] Apart from errors from antenatal screening and diagnosis, errors in ultrasound and screening, and training programs, the remaining six-listed most common cause of lawsuit in obstetrics are related to failure to perform caesarean section or to perform the operation early enough. This implies, therefore, that early resort to caesarean section at the suspicion of impairment of fetal well-being is likely to avert obstetric litigation. The consequence of this may be the likelihood of an overall increasing rate of caesarean section.[17] This is, however not corroborated by the report of Dranove and Watanabe.[27] Litigation trend is increasing in obstetrics practice with concomitant high awards especially for cerebral palsy, to the extent that accompanying high insurance risks in obstetrics practice is constituting a serious threat to the future of obstetrics.[6,28,29] In a study carried out among 826 Obs/Gyn practitioners in Australia, only 44% intended to continue obstetrics practice after 5 years. The main reasons given for ceasing obstetrics were intention to specialize in gynecology, fear of litigation, high indemnity costs, family disruption, and long working hours.[6]

Conclusion and Recommendation

The rising trend in litigations in obstetrics practice although presently observed in the developed countries none the less represent global phenomena that will likely spread in the not too distance future to the developing countries, especially with increasing education, human rights awareness, and overall socio-economic emancipation of the people of these countries. The impact of this to the practicing Obstetricians/Gynecologists, as well as the health institutions, is likely to be devastating in countries where the health practitioners are seldom covered with the medical insurance. Obs/Gyn professionals should be mindful of this development and be prepared to face the inevitable challenge.

Reducing litigations in obstetrics requires that the Obs/Gyn practitioner develops a high index of mindfulness of the possibility of litigation from medical malpractice. He is, therefore, expected to first and foremost, be conversant with the various medical laws and codes that govern his medical practice. Communication of the various risks of any treatment must be clearly made to the patient as of right. The health professional should adhere strictly to proper documentation with respect to consent and also procedures, activities, and time. Proper medical record keeping often provides good legal documents of defense in cases of litigation. Obs/Gyn consultant must ensure thorough supervision of their residents-in-training, and young consultant should enlist the advice of older ones in the management of certain conditions. Treatment protocols should be developed not only to guide practitioners but also to standardize and streamline patient's care. The Obs/Gyn practitioners should adhere strictly to this protocol irrespective of how basic some of them may be. For example, scrubbing protocol before surgery and counting protocol for surgical instrument and abdominal mops after surgery. Medical equipments should always be kept in good working conditions, be upgraded as appropriate and if necessary be changed entirely to ensure patient's safety. Continuing medical education, training and re-training of Obs/Gyn practitioners, irrespective of the status, especially on new and emerging trends in obstetrics practice are very important in the improvement of the safety and quality of patient's care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chou MM. Litigation in obstetrics: A lesson learnt and a lesson to share. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FMOH. Integrated, Maternal and New Born and Child Health Strategy. Abuja: FMOH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva: WHO; 2007. World Health Organization. Maternal mortality in 2005: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent C, Bark P, Jones A, Olivieri L. The impact of litigation on obstetricians and gynaecologists. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;14:381–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alice Langholt. Has Your OBGYN Been Sued for Malpractice? [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.life123.com/parenting/pregnancy/prenatal.care/malpractice.shtml .

- 6.MacLennan AH, Spencer MK. Projections of Australian obstetricians ceasing practice and the reasons. Med J Aust. 2002;176:425–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. General Accounting Office: Medical Malpractice Insurance. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.citizen.org/documents/GAO2_17_04.pdf .

- 8.National Bureau of Economic Research. Do Medical Malpractice Costs Affect the Delivery of Health Care? National Bureau of Economic Research. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 19]. Available from: http://www.nber.org/bah/fall04/w10709.html . [PubMed]

- 9.Alakija O. A Handbook on Medical Ethics and Medical Jurisprudence. 4th ed. Lagos, Nigeria: Medi Success Publication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethical Issues in Obstetrics and Gynecology by the FIGO Committee for the Study of Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women's Health. November. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.FIGO Professional and Ethical Responsibilities Concerning Sexual and Reproductive Rights. Dec. 2004. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.figo.org/Codeofethics . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report. Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington: DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78.0012; 1978. p. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James HJ. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osuagwu EM. Negligence in Medical and Hospital services in Nigeria – Paper Presented at the Psychiatric Hospital, Yaba Lagos; May. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen John Apartheid South Africa; an insider's overview of the origin and effects of separate development 2005. I universe. :xi. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen John Apartheid South Africa; an insider's overview of the origin and effects of separate development 2005. I universe. p. xi.

- 17.Fuglenes D, Oian P, Kristiansen IS. Obstetricians’ choice of cesarean delivery in ambiguous cases: Is it influenced by risk attitude or fear of complaints and litigation? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:48.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commonwealth Medical Association Trust (COMMAT). Consultation on Medical Ethics and Women's Health, including Sexual and Reproductive Health, as a Human Right. NY, USA: 1997. Jan 23-26, [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzodike VO. Ethical codes and statements. In: Uzodike VO, editor. Medical Ethics: Its Foundation, Philosophy and Practice (With Special Reference to Nigeria and Developing Countries) Enugu, Nigeria: Computer Edge Publishers; 1998. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva: Prepared by CIOMS in Collaboration with WHO; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Code of Medical Ethics in Nigeria (Revised edition January, 2004). Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adinma JI. International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics/Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics of Nigeria (FIGO/SOGON) Human Rights Code of Ethics on Women's Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare for Health Professionals in Nigeria. FIGO/SOGON Women's Sexual and Reproductive Rights Project (WOSRRIP) 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogwuche AS. Compendium of Medical Law. 1st ed. Ikoyi, Nigeria: Maiyati Chambers; 2002. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 29]. Available from: http://library.nsa.gov.ng/handle/123456789/352 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heintzelman CA. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and its Implications for the 21st Century. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 21]. Available from: http/www.socialworker.com/Tuskegee.htm .

- 25.Beauchamp TL, Walters L. Contemporary Issues in Bioethics. 5th ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillon R, editor. Principles of Health Care Ethics. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dranove D, Watanabe Y. Influence and deterrence: How obstetricians respond to litigation against themselves and their colleagues. Am Law Econ Rev. 2009;12:69–94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obstetrics and litigation backlash. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 19]. Available at http://www.rightdiagnosis.com/news/obstetrics_and_litigation_backlash.htm .

- 29.Gibson CS, MacLennan AH, Hague WM, Haan EA, Priest K, Chan A, et al. Associations between inherited thrombophilias, gestational age, and cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]