Summary

Cells require nucleotides to support DNA replication and to repair damaged DNA. In addition to de novo synthesis, cells recycle nucleotides from the DNA of dying cells or from cellular material ingested through the diet. Salvaged nucleosides come with the complication that they can contain epigenetic modifications. Since epigenetic inheritance of DNA methylation mainly relies on copying of the modification pattern from parental strands1-3, random incorporation of pre-modified bases during replication could have profound implications for epigenome fidelity and yield adverse cellular phenotypes. Although the salvage mechanism of 5-methyl-2′deoxycytidine (5mdC) has been investigated before4-6, currently it remains unknown how cells deal with the recently identified oxidised forms of 5mdC – 5-hydroxymethyl-2′deoxycytidine (5hmdC), 5-formy-2′deoxycytidine (5fdC) and 5-carboxyl-2′deoxycytidine (5cadC)7-10. Here we demonstrate that enzymes of the nucleotide salvage pathway display substrate selectivity, effectively protecting newly synthesized DNA from the incorporation of epigenetically modified forms of cytosine. Thus cell lines and animals can tolerate high doses of these modified cytidines without any deleterious effects on physiology. Interestingly, by screening cancer cell lines for growth defects following exposure to 5hmdC, we unexpectedly identify a subset of cell lines where 5hmdC or 5fdC administration leads to cell lethality. Using genomic approaches we discover that the susceptible cell lines overexpress cytidine deaminase (CDA). CDA converts 5hmdC and 5fdC into variants of uridine that are incorporated into DNA, resulting in accumulation of DNA damage and ultimately, cell death. Our observations extend current knowledge of the nucleotide salvage pathway by revealing the metabolism of oxidised epigenetic bases, and suggest a therapeutic option for cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, that have CDA overexpression and are resistant to treatment with other cytidine analogues11.

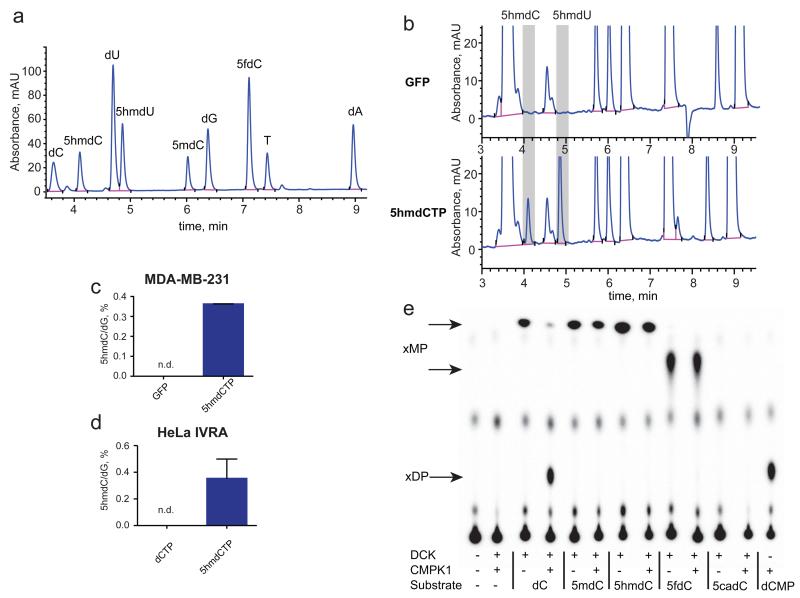

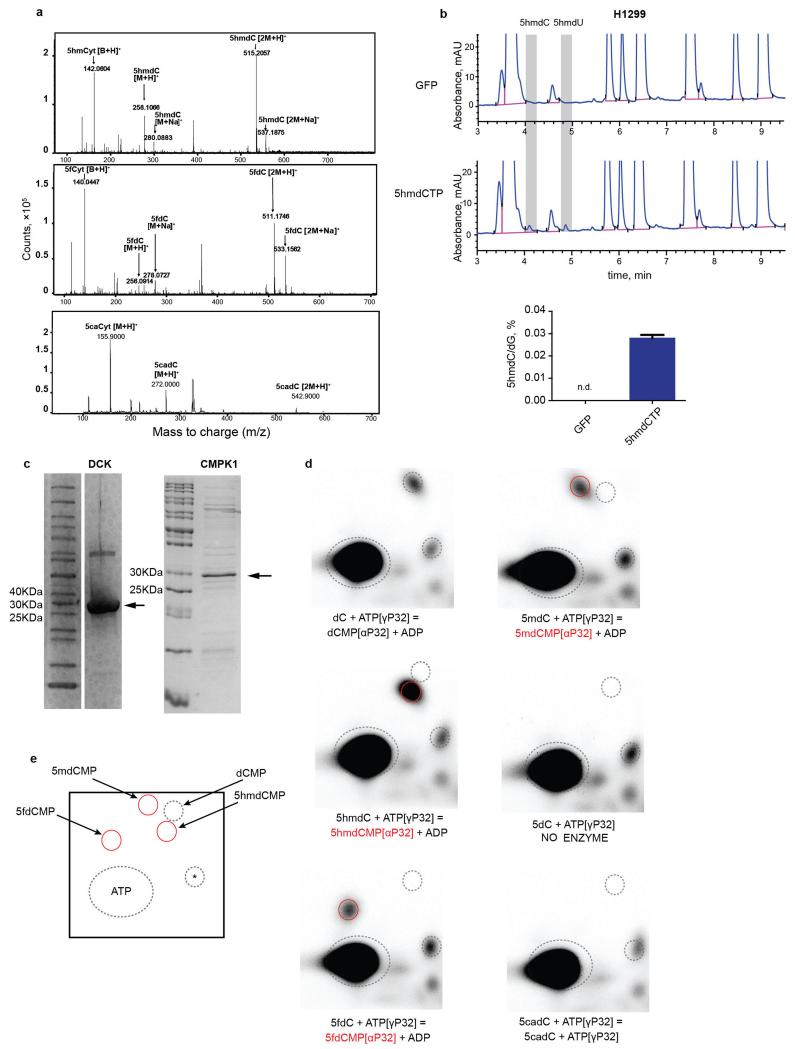

Modified cytidines can enter deoxynucleotide pools, because salvage and nutrient uptake pathways can recover nucleosides, rather than simpler degradation products such as uric acid in the salvage of purines12. Previous biochemical work suggested that 5mdC is not incorporated in the DNA, but is salvaged as thymidine4-6. Salvage of oxidised 5-methylcytosine (5mCyt) variants has not been previously characterised. We rationalised that, if nucleosides are recovered in un-phosphorylated forms (through import) or monophosphate forms (through intracellular hydrolysis), the barrier restricting their incorporation into the DNA may lie in the nucleotide salvage enzymes or DNA polymerases. Providing cells with a final substrate for DNA polymerases, in the form of deoxynucleoside triphosphate, would allow decoupling of DNA synthesis from salvage enzyme activity. Therefore, we transfected two human cancer cell lines - MDA-MB-231 and H1299 with 5-hydroxymethyl-2′deoxycytidine triphosphate (5hmdCTP), isolated DNA and analysed base composition by HPLC-UV, which was calibrated with a set of nucleoside standards (Fig. 1a). After 5hmdCTP transfection, two additional nucleosides were observed in the hydrolysed DNA that correspond to 5hmdC and 5hmdU (Fig. 1b, c, Extended Data Fig. 1b). This indicates that DNA polymerases can incorporate 5hmdC into DNA and also demonstrates strong deaminase activity acting on either the nucleotide or on the incorporated base, resulting in the presence of 5hmUra in the DNA. The capacity for DNA polymerases to use 5hmdCTP was also evident in an in vitro replication assay13 (Fig. 1d), demonstrating that human DNA polymerases are not selective against the incorporation of 5hmdC into DNA. Therefore, if salvage pathways can convert pre-existing sources of 5hmdC into their nucleotide triphosphate forms, this could result in their incorporation into cellular DNA and potentially lead to deleterious effects on the epigenome.

Figure 1. DNA polymerase and nucleoside kinase activities on modified nucleosides.

a, HPLC-UV (260 nm) chromatogram of nucleosides mixed in equimolar amounts. b, HPLC-UV examination of nucleosides derived from DNA extracted from MDA-MB-231 cells nucleoporated with 5hmdCTP. c, The abundance of 5hmdC relative to dG in nucleoporated MDA-MB-231 (n=3, standard deviation is shown, n.d. = not detected). d, 5hmdCTP incorporation assessed by in vitro replication assay (IVRA) performed in HeLa cells, measured by HPLC-UV (n=5, standard deviation is shown, n.d.= not detected). e, TLC separation of reaction products of DCK and CMPK1 kinases, which were supplied with different modified cytidine substrates. xMP indicates cytidine monophosphates; xDP indicates cytidine diphosphates.

The final triphosphate form of cytidine in a cell is produced by sequential phosphorylation by three classes of cytidine kinases. First, deoxycytidine kinase (DCK) produces a monophosphate, which is then converted into a diphosphate by cytidine monophosphate kinases (CMPK1, CMPK2), and subsequently into a triphosphate by the family of nucleoside diphosphate kinases (NDPKs)14. Since NDPKs phosphorylate both purine and pyrimidine nucleosides15, and CMPK2 is found in the mitochondria16, we directed our efforts on examining the substrate selectivity of DCK and CMPK1. Recombinant DCK was able to transfer the phosphate from ATP[γ-32P] to 5mdC, 5hmdC and 5fdC, but not 5cadC (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1d), while CMPK1 phosphorylated only unmodified cytidine monophosphate (Fig. 1e). In agreement with previous work on 5mdC4, we can conclude that the inability of CMPK1 to create diphosphates of modified nucleotides provides the main barrier to the formation of respective dCTPs, limiting their availability for DNA polymerases, which can instead accept modified dCTPs.

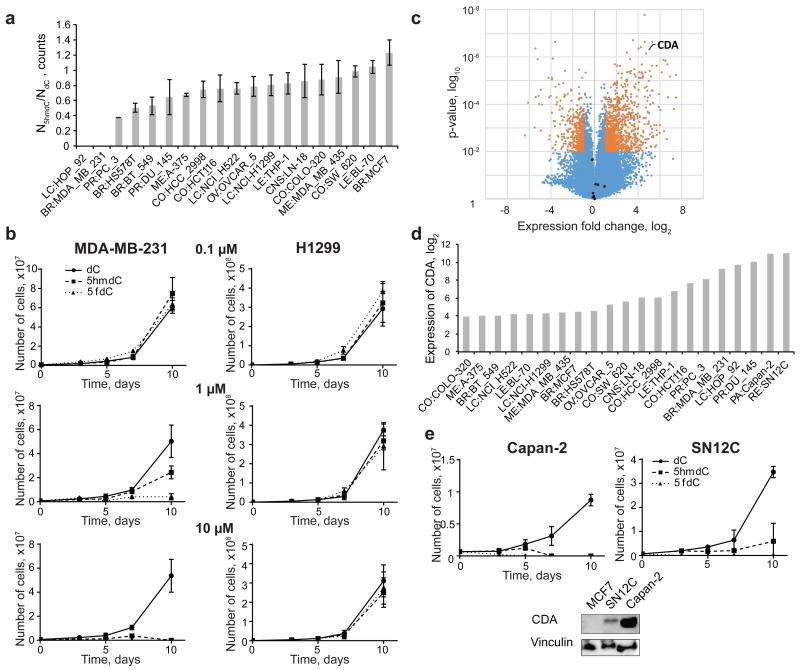

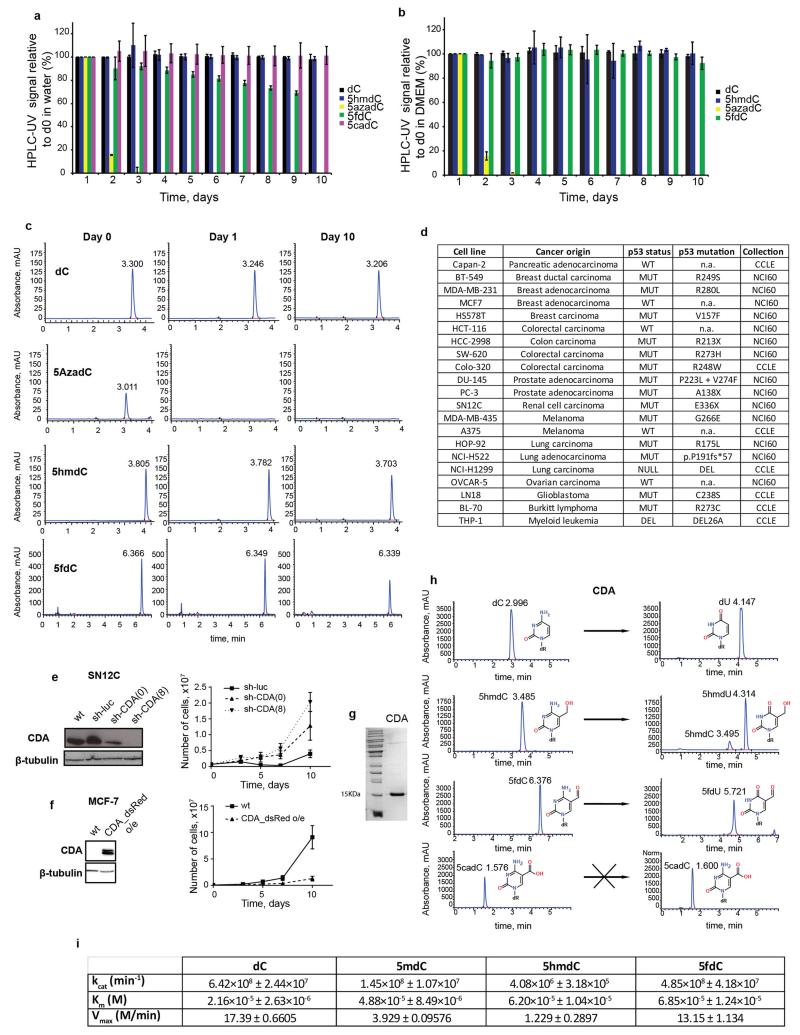

Given this inherent selectivity of the nucleotide salvage pathway kinase CMPK1 for unmodified cytidine, we hypothesized that the introduction of abundant biologically modified cytidine variants would have little adverse effect on the physiology of a cell, unless they significantly impaired nucleotide metabolism. First, we determined that biological cytidine variants retain 70-100% of their original form after incubation in water and cell culture media for 10 days at 37°C, while 80% of the synthetic variant 5-aza-2′deoxycytidine (5azadC) decomposed by day 2 in agreement with previous observations17 (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b,c). Next, a panel of 19 human cell lines was selected, sampling various tissue origins and p53 mutation statuses (Extended Data Fig. 2d)18. When cell growth media was supplemented with 10 μM 5hmdC or dC, the majority of the cell lines continued to proliferate at a normal rate. However, two cell lines (HOP-92 and MDA-MB-231) unexpectedly ceased to proliferate in presence of 5hmdC (Fig. 2a). 10 μM 5hmdC was lethal and 1 μM 5hmdC caused mild growth inhibition (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, 5fdC was more potent at 1 and 10 μM doses in the MDA-MB-231 cell line, but displayed the same cell line selectivity as 5hmdC (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Identification of cytidine deaminase (CDA) overexpression as a primary determinant for cytotoxic action of natural cytidine variants.

a, Ratio of live cells after 10 days of treatment with 5hmdC versus dC (n=3, standard deviation is shown). b, Growth curves of MDA-MB-231 and H1299 cell lines treated with 3 different concentrations of dC, 5hmdC and 5fdC over a period of 10 days (n=3, standard deviation is shown). c, Volcano plot illustrating analysis of gene expression of MDA-MB-231 and HOP-92 versus MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cell lines. Shown in orange are the genes, which are significantly different between the groups (p<0.01; >2 fold change). Dots in black show nucleoside transporters (SCL29A1, SLC29A2, SLC29A3, SLC29A4, SLC28A1, SLC28A2, SLC28A3) and kinases (DCK, CMPK1). d, CDA expression levels from NCI60 and CCLE global gene expression datasets for different cancer cell lines. e, Western blot confirming CDA overexpression in SN12C and Capan-2 cell lines. Growth curves of Capan-2 and SN12C after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC, 5fdC and dC (n=3, standard deviation is shown).

Genetic alterations or gene expression differences could modify the response of a cell line to biologically modified cytidine variants. By comparing the existing gene expression profiles of the cell lines (NCI60 and CCLE projects19,20) that we established as sensitive to modified cytidine variants to two randomly chosen resistant ones, we identified 1380 differentially expressed genes (p<0.01, >2-fold change). Interestingly, by focussing on differentially expressed genes known to be in involved in nucleoside metabolism, we identified cytidine deaminase (CDA) overexpression in the 5hmdC sensitive cell types, which had the 9th lowest p value of all the genes (Fig. 2c, Extended Table 1). Importantly, none of the other known genes involved, either in nucleoside transport or cytidine recycling, were differentially expressed (Fig. 2c). To identify other cell lines with CDA overexpression, we ranked the 21 available cell lines according to their CDA mRNA levels (Fig. 2d). SN12C and Capan-2 cell lines had the highest CDA expression, which was confirmed at the protein level by Western blot (Fig. 2e). Examination of 5hmdC and 5fdC tolerance revealed that a 10 μM dose substantially inhibited the growth of both cell lines, suggesting that the expression level of CDA is predictive of cytotoxicity for these epigenetic cytidine variants (Fig. 2e).

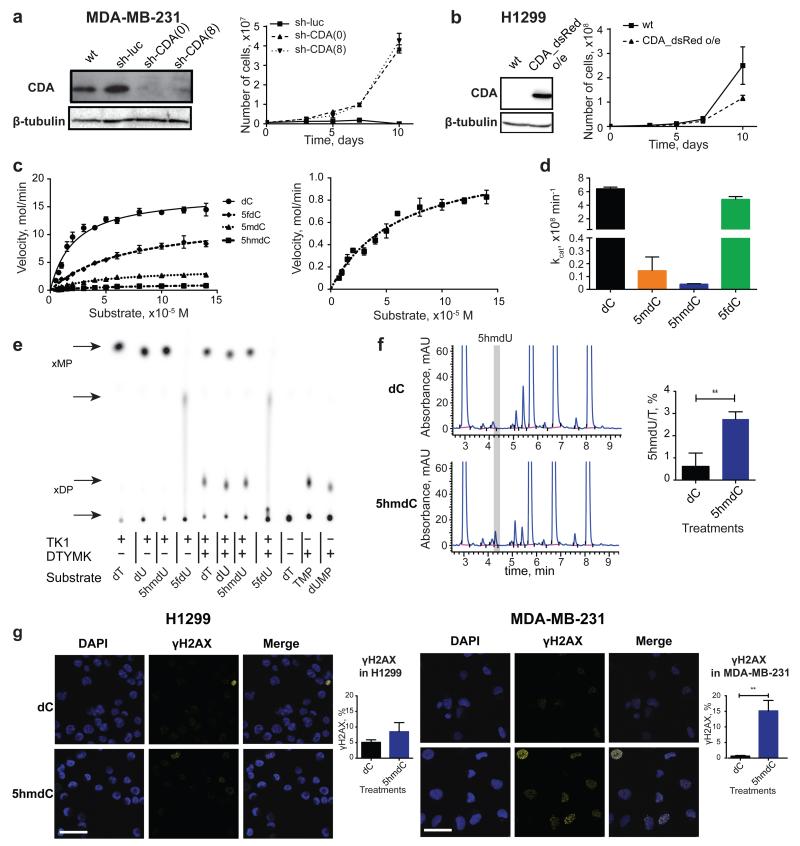

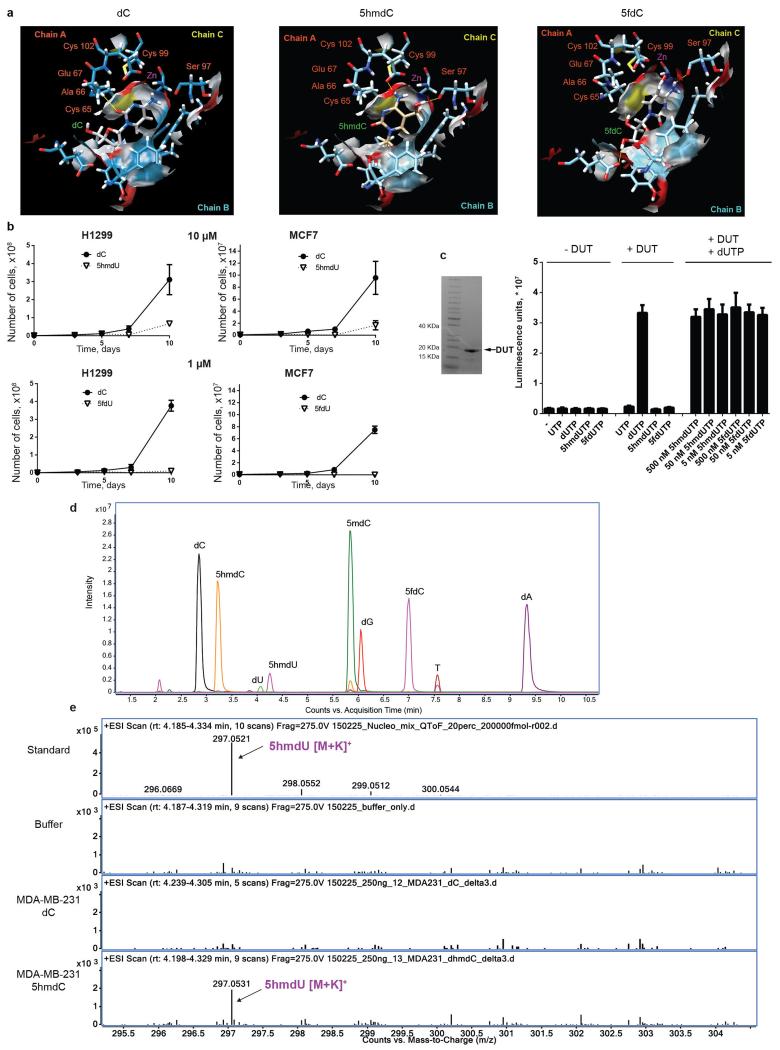

To determine whether CDA overexpression is necessary for selective cytotoxicity, we manipulated CDA levels in the identified cell lines. Cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and SN12C) with stable shRNA knock-down of CDA were able to survive 10 μM 5hmdC (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 2e). Furthermore, stable overexpression of CDA in normally 5hmdC-resistant cell lines (H1299 and MCF-7) induced substantial growth inhibition (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 2f). These experiments clearly established that CDA overexpression is predictive, necessary and sufficient for cytotoxic activity. In vitro measurements of recombinant CDA protein activity were performed with various cytidine variants. First, we determined that CDA deaminates 5mdC, 5hmdC and 5fdC, but not 5cadC, creating thymidine and respective variants of uridine (Extended Data Fig. 2g, h). Second, reaction kinetic data fitted well with a pseudo zero-order kinetics model (R2>0.9) revealing that, after dC, the second best substrate (i.e. second highest kcat) for CDA is 5fdC (Fig. 3c, d, Extended Data Fig. 2h). This was unexpected, because the catalytic activity does not follow a simple relationship with the dimensions of the 5′ modification as it does in the case of AID and APOBEC enzymes21. Molecular docking of cytidine variants to the CDA structure22 suggested that 5fdC docks to the catalytic site with nearly 180° rotation when compared to unmodified cytidine, retaining the amino group position close to the active site containing Zn2+ (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Contrary, 5hmdC docks in the active site by displacing the amino group, which provides a potential explanation for the lower catalytic turnover observed (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Molecular mechanism of CDA-dependent cytotoxicity of cytidine variants.

a, Western blot showing knock-down of CDA by sh-RNA in the MDA-MB-231 cell line. Right panel illustrates growth curves of derived stable cell lines after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC (n=3, standard deviation is shown). (0) and (8) indicates two different sh-RNA constructs used for the experiments. b, Western blot showing overexpression of CDA after lentiviral transduction of H1299 cells with a construct overexpressing CDA (CDA_dsRed). The right panel shows the growth curve after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC (n=3, standard deviation is shown). c, CDA activity fitted to the Michaelis-Menten model. The right panel shows a zoomed-in curve, when 5hmdC was used as a substrate. d, kcat values of CDA supplied with cytidine variants. e, TLC separation of reaction products of TK1 and DTYMK kinases, which were exposed to different modified uridine substrates. xMP indicates monophosphates and xDP indicates diphosphates. f, HPLC-UV chromatogram of nucleosides from DNA of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 10 μM 5hmdC or dC for 3 days. The right panel shows the abundance of 5hmdU relative to T (n=3, standard deviation is shown, t-test, p=0.0057). g, γH2AX immunofluorescence in MDA-MB-231 and H1299 cell lines at day 3 after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC or dC. Scale bar = 50 μm. Below are quantifications of cells showing positive signals (n=3, standard deviation is shown, t-test, p=0.0017).

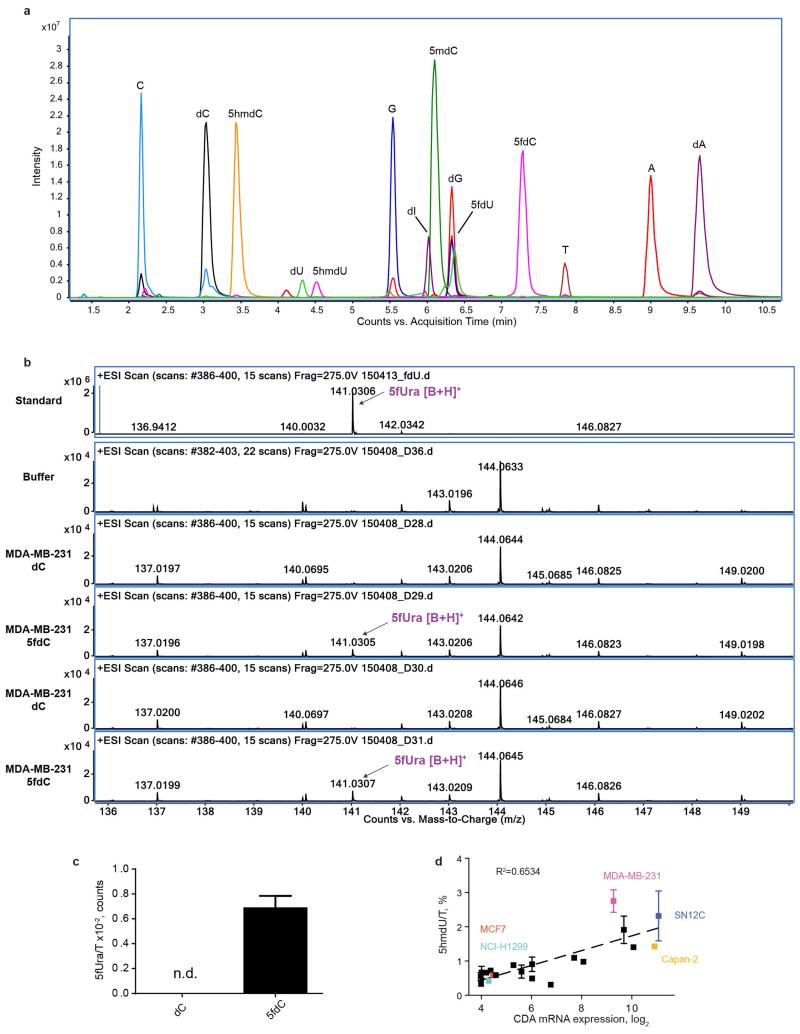

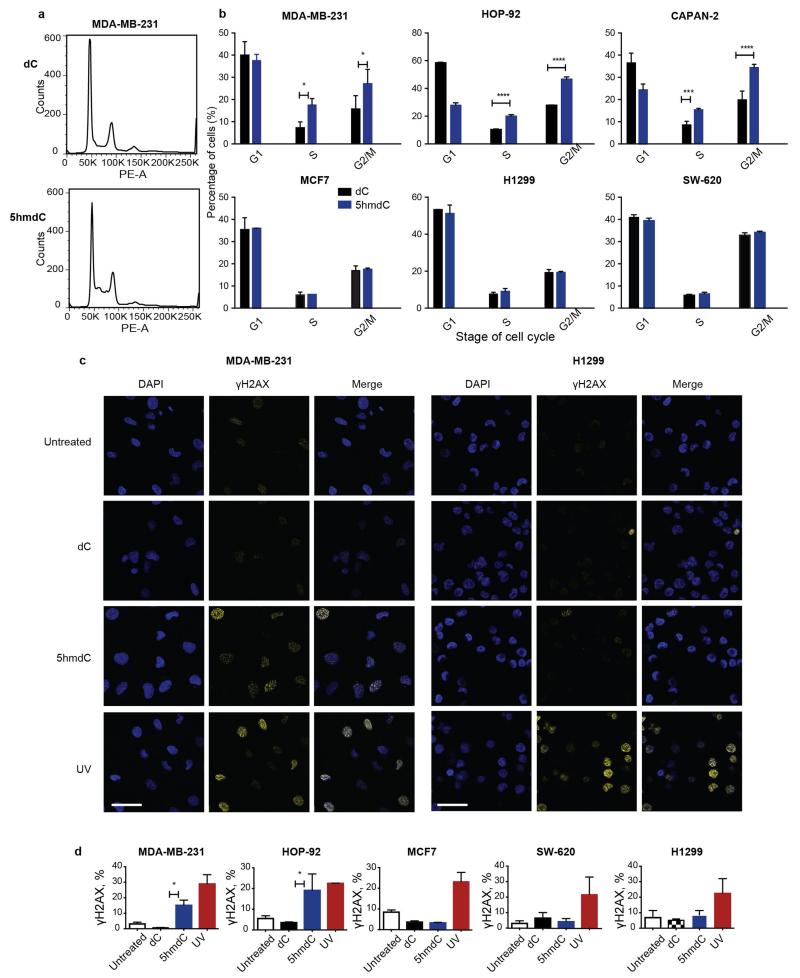

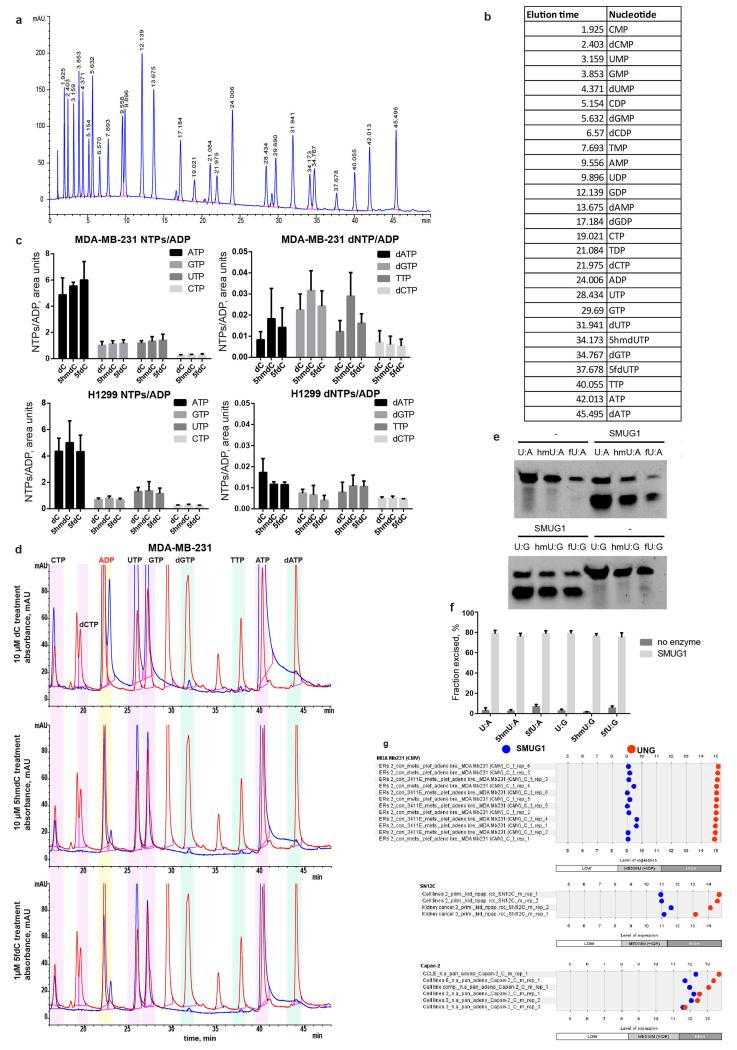

The deamination of dC and 5mdC results in dU and T, which are the normal precursors for thymidine triphosphate (TTP) synthesis. Conversely, deamination of 5hmdC and 5fdC produces 5hmdU and 5fdU, respectively, which are not canonical nucleosides. When phosphorylated and incorporated into DNA, 5hmdU and 5fdU are toxic to the cells (Extended Data Fig. 3b) as they are recognized as damaged bases and trigger extensive uracil glycosylase activity resulting in DNA breaks23. Therefore, we asked whether the uptake of 5hmdC in CDA overexpressing cells leads to its conversion into 5hmdU and to its incorporation into DNA, potentially explaining cell type specific lethality. First, we determined activities of thymidine kinase (TK) and thymidylate kinase (DTYMK) on 5hmdU and 5fdU. In contrast to the inability of CMPK1 to act on equivalent cytidine variants, TK and DTYMK phosphorylated both uridine variants (Fig. 3e). Notably, the corresponding triphosphates are not substrates nor potent inhibitors of dUTPase, a robust enzyme that removes dUTP from cells (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Finally, analysis of the genomic DNA composition of 5hmdC and 5fdC treated MDA-MB-231 cells identified 5hmUra and 5fUra, but no detectable change in 5hmCyt or 5fdCyt levels in the DNA (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 3d, e and Extended Data Fig. 4a, b, c). Overall, in all the cell lines examined, a linear correlation was observed between CDA expression and the amount of 5hmdU in the DNA after treatment with 5hmdC (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Signs of extensive DNA damage were detected by phosphoH2AX staining in 5hmdC-treated CDA overexpressing cells (MDA-MB-231). In contrast, a cell line expressing low level of CDA (H1299) had no obvious phospho-H2AX (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 5c, d). Also, increased numbers of cells in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle were observed in CDA overexpressing cell lines, consistent with cell cycle arrest triggered by a DNA damage response (Extended Data Fig. 5a). We did not observe deviations in the dNTP pools of treated cells, indicating that the cell death is likely to be caused by extensive base excision by SMUG1 DNA glycosylase, which recognises 5hmUra and 5fUra triggering repair and DNA double stranded breaks (Extended Data Fig. 6). Together, these observations demonstrate that CDA deaminates 5hmdC and 5fdC creating 5hmdU and 5fdU (respectively), which are incorporated into the DNA, leading to cell cycle arrest and eventually death.

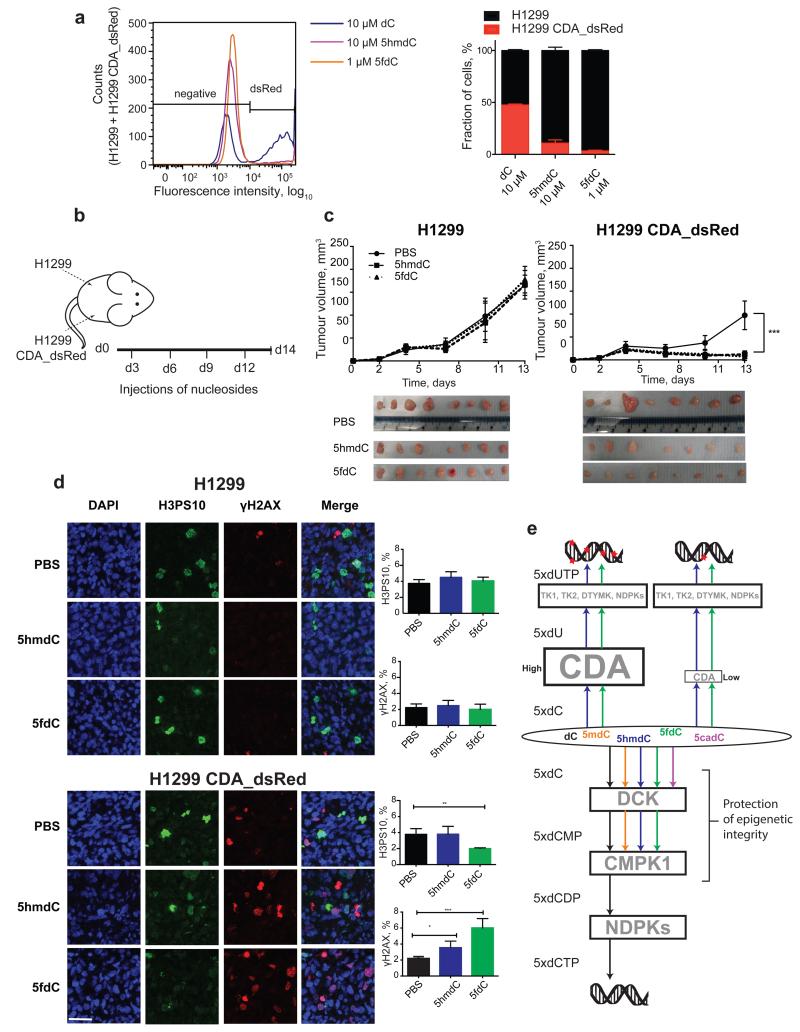

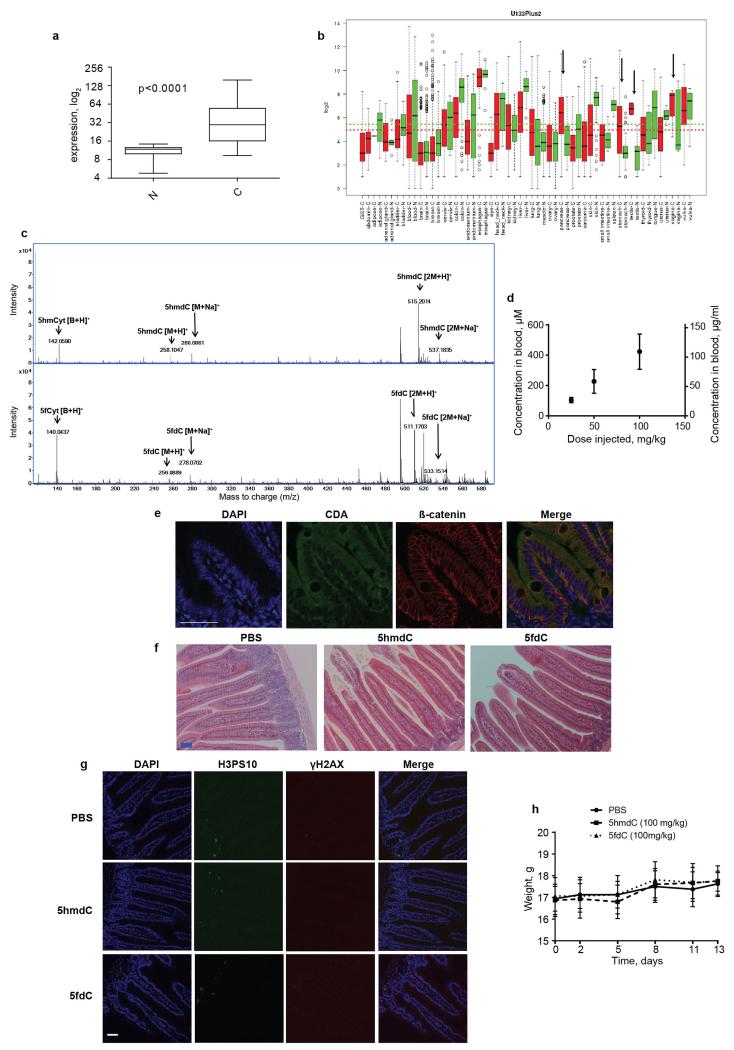

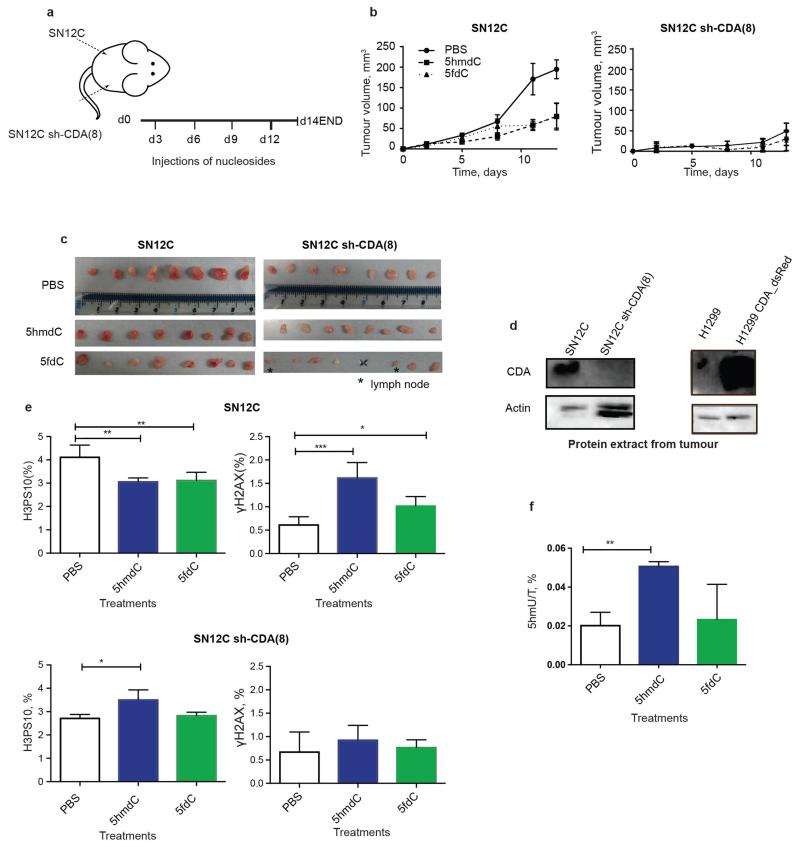

CDA overexpression has been linked to resistance to cytidine analogues – such as gemcitabine, cytosine arabinoside or 5-azacytidine – that are currently used in cancer treatment, presenting a major obstacle to their use11,24-26. Our observations regarding biological nucleoside variants demonstrate an opposite effect: CDA overexpression sensitises cells to otherwise non-toxic 5hmdC and 5fdC. Since cancers originating in the pancreas27, stomach, testis and vagina have up-regulated CDA expression28 (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b), we postulated that administration of 5hmdC and 5fdC could have a selective activity against these tumour cells. We first tested whether cytotoxic activity is cell autonomous for CDA overexpressing H1299 cells in the presence of wild type (wt, CDA low) H1299 cells. Both 5hmdC and 5fdC were able to selectively eliminate CDA overexpressing cells, suggesting that secreted CDA or 5hmdU is insufficient for cytotoxicity (Fig. 4a). Tolerance to and stability of 5hmdC and 5fdC in vivo was determined in immunocompromised BALB/cOlaHsd-Foxn1nu/nu mice after they received a range of doses (12.5 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg) of 5hmdC and 5fdC by intraperitoneal injection. Half an hour after injection, we were able to detect 5hmdC and 5fdC in the bloodstream, and to quantify 5hmdC using RapidFire MS (Extended Data Fig. 7c, d). We observed no adverse effects on behaviour, injection site, weight or histology in the panel of tissues studied, even though some tissues (kidney and intestine) express CDA (Extended Data Fig. 7e, f, g, h, data not shown). To determine whether cytidine variants have an effect on tumour growth in proliferating cells, we subcutaneously injected H1299 wt and CDA overexpressing cells into each side of an animal, which was later treated with 5hmdC or 5fdC (Fig. 4b). Xenografts with CDA overexpression grew slightly slower (reaching 64% of wt tumour volume), and the volume of the tumour was further reduced 2-fold in animals treated with 5hmdC or 5fdC (Fig. 4c). CDA-overexpressing tumours showed a 2-fold decrease in the number of proliferating cells and a 3-fold increase in the number of cells with DNA damage in 5fdC-injected animals, but smaller differences in animals that were 5hmdC-injected (Fig. 4d). Similar CDA-dependent effects on tumour volume and proliferation were observed when SN12C wt and SN12C CDA knock-down cells were used in the xenograft assay (Extended Data Fig. 8).

Figure 4. In vivo evaluation of cytidine variants and the proposed model of epigenetic nucleoside variants in the nucleoside recycling pathway.

a, wt and CDA_dsRed overexpressing H1299 cells were mixed at equal ratios and exposed to the indicated variants of cytidine. Representative histogram (left) and quantitation of the results (right) are shown (n=3, standard deviation is shown, 10,000 events recorded). Lower concentration of 5fdC was used to demonstrate higher cytotoxic potency. b, Schematic illustration of xenograft establishment and treatment with nucleoside variants. c, Volume of tumours, calculated by assuming that tumours were spheres with their diameters measured using Vernier calipers (n=8 in 5fdC and n=7 in 5hmdC experiments, standard deviation is shown, two-way ANOVA with repeated measures Holm-Sidak correction, p<0.0001). Dissected tumours are illustrated in the photo below. d, Evaluation of proliferation (immunofluorescence, H3PS10) and DNA damage (immunofluorescence, γH2AX) in dissected tumour samples. Scale bar = 50 μm (n=4, standard deviation is shown, one way ANOVA, H3PS10 p=0.0057, γH2AX p(5hmdC vs PBS)=0.0491, p(5fdC vs PBS)=0.0001). e, Model of metabolism of epigenetic nucleoside variants.

Here, we have characterised the metabolism of newly discovered biologically modified nucleosides, leading to a model in which the selectivity of CMPK1 prevents random incorporation of modified cytosines (Fig. 4e). Interestingly, we have discovered that 5hmdC and 5fdC, but not 5cadC, are deaminated by CDA at different rates, resulting in the cytotoxic 5hmdU and 5fdU. Our data on oxidised epigenetic bases is similar to the proposed mechanism of 5mdC salvage, in which CMPK1 is rate limiting in the production of the diphosphate, whereas 5mdC deamination produces a normal T4-6. We did not observe any adverse effects during the administration of 5hmdC and 5fdC in mice, presumably because the cytotoxic threshold is only reached in highly proliferating and CDA overexpressing cells, in which there is substantial incorporation of nucleoside variants in the DNA, reflected by the CDA-dependent regression of xenografts. Together with recent publications demonstrating the importance of and therapeutic opportunities targeting MTH1, which surveys damaged nucleosides29,30, our data extend the current understanding of the metabolism of biological cytidine variants and provide a novel avenue for cancer therapy.

Methods

Purification of DCK, CMPK1, CDA, TMPK and DUT

Human DCK with a C-terminal 6xHis tag was cloned in pET28a(+) and expressed in E. coli BL21 RIPL (Life Technologies) for 4 hrs at 37°C following induction with 1 mM IPTG in LB. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 8, 300 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free, Roche). The protein was bound to a Hi-TRAP HP 5 ml column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0-500 mM imidazole in the lysis buffer, supplemented with 10% glycerol. The fractions were assessed by electrophoresis and ones containing the protein were pooled, concentrated with Amicon 3 kDa centrifugal filter units (Millipore) and separated on a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). The protein was again concentrated using Amicon columns, supplemented with final 10 mM DTT and 40% of glycerol, snap frozen and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Human CMPK1 was tagged at the C-terminus with 6xHis and purified using a similar workflow to DCK with the following exceptions: the lysis buffer was 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors (Complete Mini, Roche); after the gel filtration step the protein was bound to an anion exchange column HiTrap Q HP 5 ml (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a 20 column volumes linear gradient of 0-1 M NaCl. The salt was removed by dialysis in 50 mM Tris pH 8, the protein concentrated and 10 mM DTT added to the final preparation, prior to storage in 40% glycerol at −80°C. C-terminal 6xHis tagged CDA was purified in a similar workflow to CMPK1 with the following modifications: the protein was expressed for 19h at 37°C; the lysis buffer was 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA and protease inhibitors (Complete Mini, Roche); following HiTRAP purification, 6xHis tag was cleaved by thrombin (Sigma); cleaved tag and un-cleaved protein was removed by separation using a HiTRAP HP 5 ml column and collection of the flow-through. Subsequently, the protein was purified using gel filtration as indicated above and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Protein purity was assessed by electrophoresis and CDA was additionally identified by MS. Human TMPK1 with a C-terminal 6xHis tag was cloned in pET28a(+) and expressed in E. coli BL21 RIPL (Life Technologies) for 4 hrs at 37°C following induction with 1 mM IPTG in LB. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7, 300 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free, Roche) and lyzed with a French press (EmulsiFlex C5, Avestin) at 15000 psi equipped with a recirculating cooler (F250, Julabo) set at 4°C. The protein was bound to a Hi-TRAP HP 5 ml column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0-500 mM imidazole in the lysis buffer, supplemented with 10% glycerol. The fractions were assessed by electrophoresis and ones containing the protein were pooled, concentrated with Amicon 3 kDa centrifugal filter units (Millipore), supplemented with 40% of glycerol, snap frozen in aliquots and stored at −80°C. Human DUT with a C-terminal 6xHis tag was cloned in pET28a(+) and expressed in E. coli BL21 RIPL (Life Technologies) for 4 hrs at 37°C following induction with 0.2 mM IPTG in LB. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free, Roche) and lyzed with a French press (EmulsiFlex C5, Avestin) at 15,000 psi equipped with a recirculating cooler (F250, Julabo) set at 4°C. The protein was bound to a Hi-TRAP HP 5 ml column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0-500 mM imidazole in the lysis buffer, supplemented with 10% glycerol. The fractions were assessed by electrophoresis and ones containing the protein were pooled, concentrated with Amicon 3 kDa centrifugal filter units (Millipore), supplemented with 40% of glycerol, snap frozen and stored in aliquots at −80°C. TK was purchased and the purity assessed by SDS PAGE (8180-TK-050, R&D Systems).

Nucleoside stability

Nucleosides were obtained from the following sources: 5hmdC (PY-7588, Berry & Associates), 5fdC (PY-7589, Berry & Associates), 5cadC (PY-7593, Berry & Associates), 5AZAdC (A3656, Sigma Aldrich), ATP solution (Thermo Fisher), [γ-32P] ATP (Perkin Elmer), dC (Sigma Aldrich, D3897), dCMP (Sigma Aldrich, D7625), 5hmdCTP (Bioline, BIO-39046). 100 μM solutions of 5hmdC, 5fdC and 5AZAdC were prepared in HPLC grade water (Thermo Fisher) or in DMEM medium (Lonza). The solutions were incubated at 37°C for 10 days. A sample was taken every 24 h and subjected to HPLC-UV analysis.

Enzyme assays

The substrate selectivity of DCK and CMPK1 kinases were measured by 32P transfer and detection using one (1D) or two (2D) dimensional thin layer chromatography (TLC). 1 μg of DCK kinase was incubated in 100 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM [γ-32P] ATP and 200 μM of the respective nucleoside in a 50 μl reaction volume at 37°C for 2 h. 1 μl of products was separated via 2D TLC on glass-backed AVICEL cellulose plates (Analtech) as described31. CMPK1 was assayed through a coupled assay with DCK following the conditions described in 32 with 1 μg DCK, 1 μg CMPK1 and 1 mM substrate. TK (8180-TK-050, R&D Systems) and TMPK1 were assayed through a coupled assay with 1 μg TK, 1 μg TMPK1 and 1 mM substrate in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 2.5 μCi [γ-32P] ATP at 37°C. 1D TLC was performed using glass-backed TLC sheets (PEI cellulose F, Millipore) as described before32. The plates were exposed to storage phosphor screen (GE Heathcare), which was scanned using Phosphoimager (Biorad) and images analysed with ImageLab software (Biorad). CDA kinetic activity data was collected as described33 by monitoring the absorbance at 260 nm with a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2, Molecular devices) using 45 ng of enzyme (500 ng for 5hmdC) and the data fitted according to pseudo zero order Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetic model by Prism software (GraphPad). 1 μg DUT was assayed in 50 mM Tris pH7.5, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA with 5 μM of substrate in 40 μl reaction volume for 10 min at 37°C. The generated pyrophosphate was detected with a bioluminescent coupled assay (PPiLight™ inorganic pyrophosphate assay LT07-500, Lonza). The plate was then read in a GloMax instrument (Promega).

Molecular docking

A tetramer was generated with CDA structure 1MQ034 and subject to DockPrep in Chimera 1.8 (www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera). Substrates were dC (ZINC18286013)35, 5hmdC (ZINC77300654)35 and 5fdC (CSID:10291642) (www.chemspider.com) downloaded as .mol files and subjected to .mol2 files conversion in Chimera. Docking was subsequently performed with SwissDock (www.swissdock.ch/docking)36. The model with the lowest ΔG of ligand was then visualized and analysed with Chimera.

In vitro replication assay

The assay was carried out following protocols for nuclear extract and cytoplasmic fraction preparation and for the replication assay37,38. The reaction contained 0.3 mM of each canonical nucleotide, except dCTP which was substituted by 5hmdCTP. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 0.1 M EDTA final. DNA was extracted with phenol chloroform, treated with RNase A/T1 (Thermo Fisher) and free nucleotides removed with a Mini Quick Spin DNA column (Roche) prior to HPLC assay.

DNA glycosylase assay

The single stranded DNA oligonucleotide substrates (5′-FAM CATAAAGTGXAAAGCCTGGA, where X = Ura, 5hmUra or 5fUra) were purchased from AtdBio and their complementary strand from IDT (all HPLC purified). Recombinant human SMUG1 (NEB) was incubated with annealed oligonucleotides as described before39. The reaction products were resolved on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide TBE-Urea gel (Invitrogen) and quantified using ChemiDoc (BioRad) with blot detection protocol for Alexa 488.

Quantitation of nucleosides by HPLC

Genomic DNA was extracted with Gene Jet Genomic DNA extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher) or TRI Reagent (Sigma Aldrich), incubated with RNase A/T1 (Thermo Fisher) in buffer 2 (NEB), phenol/chloroform extracted and precipitated with ethanol. 1-10 μg of DNA was hydrolysed as described before40. Nucleosides were resolved with an Agilent UHPLC 1290 instrument fitted with Eclipse Plus C18 RRHD 1.8 μm, 2.1×150 mm column and detected with Agilent 1290 DAD fitted with a Max-Light 60 mm cell. Buffer A was 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 6.5, buffer B was 40% acetonitrile, and the flow rate 0.4 ml/min. The gradient was between 1.8-100% of 40% acetonitrile with the following steps: 1-2 min, 100% A; 2-16 min 98.2% A -1.8% B; 16-18 min 70% A – 30% B; 18 -20 min 50% A- 50 % B; 20-21.5 min 25% A 75% B; 21.5-24.5 min 100% B.

Quantitation of nucleotides by HPLC

MDA_MB_231 and H1299 treated with 10 μM dC, 10 μM 5hmdC and 1 μM 5fdC. Metabolites were extracted at day three as described before41. Briefly, cells were washed in PBS and scraped on ice. The pellet was washed again in cold PBS and extraction was done with 50 μl of ice cold 50% ACN per mg of pellet. The samples were vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min. Insoluble material was pelleted at 20000 g for 10 min and supernatants were dried using a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific). Metabolites were dissolved in 30 μl of buffer A and 20 μl was used for chromatography. HPLC was performed as described41 with some minor modifications as listed below. Nucleotides were resolved with an Agilent UHPLC 1290 instrument fitted with Eclipse Plus C18 RRHD 1.8 μm, 2.1×150 mm column and detected with Agilent 1290 DAD fitted with a Max-Light 60 mm cell at 254, 260 and 280 nm. Buffer A consisted of 100 mM KH2PO4 (60221, Sigma) with 8 mM tetrabutylammoniumbisulfate (98479, Sigma) set at pH 5.5. Buffer B consisted of Buffer A with 25 % MeOH. After 8 min at 0% buffer B, the gradient started with a linear increase of buffer B to 35% in 19 min, followed by a linear increase from 35% to 38% buffer B in 5 min and from 38% to 100% buffer B in 22 min. After an 8 min hold at 100% Buffer B, the gradient was reversed from 100% to 0% buffer B in 2 min, followed by a hold at 0% buffer B for 2 min. The column temperature was set at 30°C and the flow rate was 0.4 ml/min. The compounds were identified by comparing their retention times and their UV spectra with those of known standards, which were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The integrated area was used to quantify the relative abundance of nucleotides by normalizing each peak area to the ADP area as an indication of loaded amount.

Cell culture and transfections

Cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using Lonza Mycoalert Kit. Cell proliferation assays were done by seeding cells in p60 plates or in a T25 flask with appropriate concentrations of 5hmdC, 5fdC or dC in the growth media. The cells were passaged, counted and the media was replaced every two days. Before counting, 1 volume of Trypan blue solution (Lonza) was added to an aliquot of single cell suspension. The live cells were counted by TC-20 Cell Counter (Bio-Rad). NTPs were introduced by nucleofection. 106 MDA-MB-231 cells were nucleofected with 50 mM 5hmdC in a 100 μl volume using an Amaxa nucleofector kit (Lonza), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, cells were seeded in a 6 well plate, 24 h later washed twice with PBS, and 48 h later DNA extracted for HPLC analysis.

Production of stable cell lines

Stable cell lines were generated via lentiviral infection using a standard protocol42 with 2nd generation packaging plasmids (pCMV-VSVG, pCMV-dR8.9, a generous gift from Bruno Amati, IIT, Milan). CDA knock-down was achieved by infecting MDA-MB-231 and SN12C cell lines with pLKO.1 vectors containing 5 different shRNA constructs (SHCLND-NM_001785, Sigma-Aldrich) and a control pLKO.1 containing shRNA silencing Luciferase (a gift from Xin Lu, Oxford Ludwig Cancer Research). Infected cells were selected by incubation with 1.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) for 60 hrs. Two cell lines with the lowest CDA mRNA (shRNA TRCN0000051290 and TRCN0000051288) levels were further assessed by immunoblotting and used for experiments. Lentivirus for CDA overexpression was generated with pLenti-puro (39481, Addgene, Ie-Ming Shih laboratory) expressing dsRed-IRES-CDA. H1299 and MCF-7 were infected as above. Infected cells were selected with puromycin at 2 μg/ml for 60 hrs.

Immunoblotting, FACS and immunofluorescence

For Western blot analysis, 106 cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free, Roche)) and sonicated. Cleared lysates were electrophoresed and immunoblotted with the following primary antibodies: α-CDA (Sigma, SAB1300717 1:250), α-actin (Abcam, ab185058 1:75000). Chemiluminescent detection, after incubation of the membranes with appropriate secondary antibodies, was done through a CCD camera using the ChemiDoc System (Bio-Rad) with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad, version 4.0). For FACS analysis, 5×105 cells were trypsinised, washed in PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol for 1 h on ice. The pelleted cells were resuspended in 250 μl of staining solution (50 μg/ml Propidium Iodide (P4864, Sigma), 0.1 mg/ml RNaseA and 0.05% Triton×100) and incubated at 37°C for 40 min. Controls were used for G1 (serum starvation overnight) and G2 (0.1μg/μl nocodazole overnight). Fluorescence of 10,000 cells was recorded with a FACS Canto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysed using FlowJo software (Version 7.6.5, TreeStar). For immunofluorescence, cells were grown on coverslips and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were washed twice in PBS and permeabilised for 10 minutes in 0.2% TritonX-100. After 2 washes in PBS, cells were blocked for 1 h in 3% BSA (Sigma Aldrich), dissolved in PBS and incubated with γH2A.X antibody (Millipore, 05-636, 1:500) overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Cells were then washed 3 times in PBS and incubated with anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa546 (1:400, Life Technologies) and DAPI (Sigma Aldrich). Coverslips were then washed 3 times in PBS and mounted with mounting media (Vectashield). Tiled pictures were automatically taken with a Zeiss 710 microscope with a 20× lens. The amount of nuclear fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ.

Gene expression analysis and public datasets

Datasets used in the study: GSE36139 (GPL15308)43, GSE32474 (GPL570)44. Gene expression analysis comparing was done on the data from the NCI-60 panel45 as follows. Affy HG-U133 Plus 2.0 microarray data was downloaded from CellMiner database (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/loadDownload.do) and cel files were extracted for triplicate experiments done on BR:MCF7, ME:MDA_MB_435, BR:MDA_MB_231 and LC:HOP_92 cell lines. Data was then imported into ArrayStar v11 (DNAStar) and signal normalisation and intensity correction was done using RMA Quantile method. Experiment was designed by grouping BR:MCF7, ME:MDA_MB_435 cell lines into “Resistant” group and BR:MDA_MB_231 and LC:HOP_92 cell lines into “Sensitive” group. Differential expression between the groups was determined using the Student’s t-test with Benjamini Hochberg multiple testing correction. Genes were called as differentially expressed when p<0.01 and fold change >2. The full dataset is included in Extended Table 1. To derive CDA expression values in tumours, GPL1530843 and GPL57044 were analysed directly on the NCBI portal with GEO2R. p-values were adjusted with Benjamini Hochberg correction.

Toxicology and dose determination in animal experiments

Animal work was done after approval by the UK Home Office and University of Oxford Local Ethical review. Three 5-7 week old BALB/cOlaHsd-Foxn1nu/nu (Harlan) mice per dose were injected (IP) with 25, 50, 100 mg/kg of 5hmdC and 12.5, 25, 50, 100 mg/kg of 5fdC. Animals were monitored for any deviations from normal behaviour. At 30 minutes post injection, a few drops of blood were collected through tail vein bleeding using Microvette CB300 (Sarstedt) to assess the amounts of the compounds in the bloodstream.

Mass spectrometry analysis of serum samples

Serum was isolated by centrifugation of Microvettes according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Sarstedt). The samples were brought up to 200 μl with water and 3 volumes of methanol, and 150 μl of chloroform added. After intense vortexing, 450 μl of water was added, samples were vortexed again and centrifuged at 14,000 rcf for 1 min. The aqueous phase containing the soluble molecules was collected and dried in a Speedvac (Thermo Scientific). The dried pellets were then resuspended in 10 μl water, then 3 μl diluted further into 50 μl of water to load on a RapidFire 360 high throughput sample delivery system. The samples were aspirated by vacuum at −40 bar for 400 ms into a 10 μl sample loop and loaded onto a graphitised carbon SPE cartridge running buffer 5 mM ammonium formate at a flow of 1.5 ml/min. The matrix components not retained on the cartridge were diverted to waste for 4500 ms, followed by elution of the retained components with 95% acetonitrile 5mM ammonium formate for 4500 ms at a flow of 1 ml/min, then analysed using an Agilent 6530 QTof mass spectrometer. The SPE was then re-equilibrated for 4500 ms with 5 mM ammonium formate. Data was collected in positive ion mode using a 2 Gb data collection, Gas temperature 300°C, Drying gas 8 l/min, Nebuliser gas 35 psig, Vcap 3500 V, fragmentor voltage 175 V. The amount of nucleoside was measured against a standard curve produced by dissolving known amounts of 5hmdC and 5fdC in foetal bovine serum and processed as indicated above. Data was analysed using an Agilent Mass Hunter Qualitative B.06 and Quantitative analysis B.05. Standard curve analysis was determined by using a quadratic curve fit algorithm for each nucleoside with an R2 >0.98 in all instances.

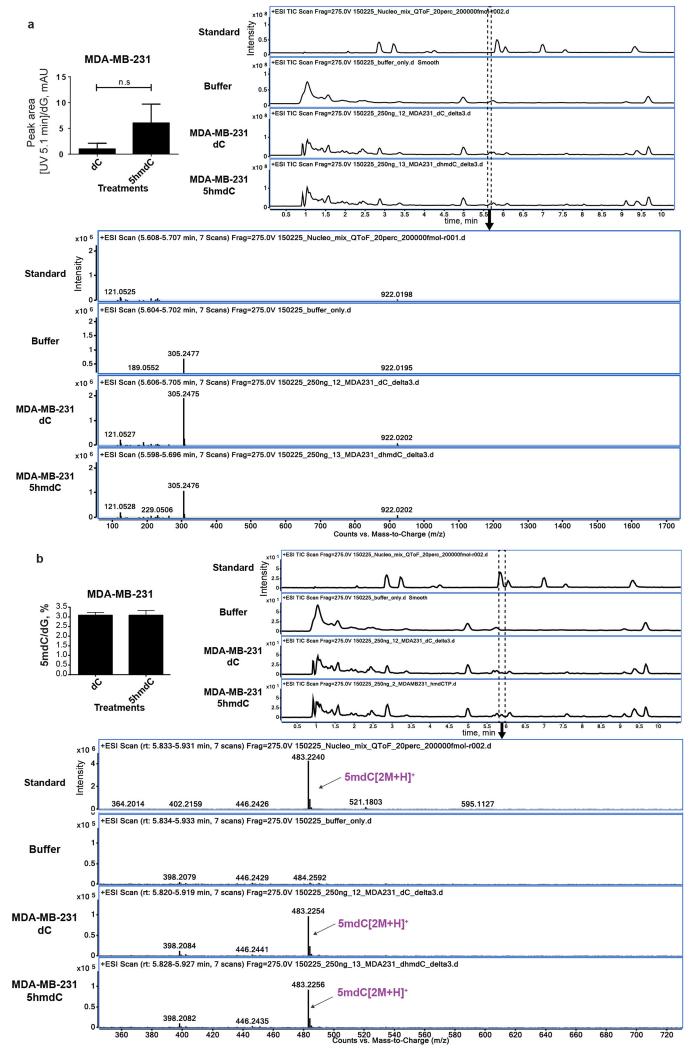

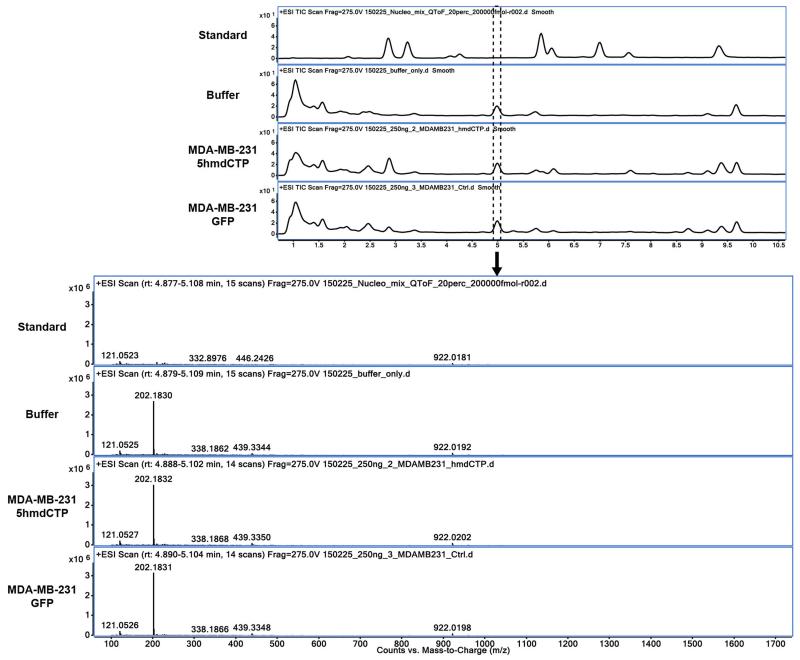

Nucleoside analysis by mass spectrometry (HPLC-QToF)

Samples were dried in a speed-vac and re-suspended in 10 μl of water. For the analysis by HPLC-QToF, a 1290 Infinity UHPLC was fitted with a BEH C18 XP Column, (130Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm X 150 mm; Waters) and coupled to a 6560 Ion mobility Q-TOF LC/MS mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with an Jetstream ESI-AJS source. The data were acquired in QToF only mode using positive electrospray ionisation (ESI+). Two reference ions, m/z 121.0508 and 922.0097 were used as internal standards. The Dual AJS ESI settings were as follows: gas temperature: 150°C, The drying gas: 5 l/min, nebulizer 35 psig, sheath gas temperature 360°C, sheath gas flow 12 l/min, VCap: 4000 V and nozzle voltage: 300 V. The fragmentor of the MS TOF was set to 275 V.

The gradient used to elute the nucleosides started by a 1 minute isocratic gradient composed with 99.5 % Buffer A (10 mM ammonium acetate pH 6) and 0.5 % buffer B (composed of 40 % CH3CN) with a flow rate of 0.350 ml/min and was followed by the subsequent steps:: 1-2 min, 98.2 % A; 2-16 min 80 % A; 16-18 min 50 % A; 18 -20 min 25 % A; 20.20-21.5 min 0 % A; 21.5-22.5 min 100% B; 22.5-24.5 min 99.5 % B. The gradient was followed by a 5 min post time to re-equilibrate the column.

The raw MS data was analysed using the MassHunter Qual Software package (Agilent Technologies, version B7.0), and the masses / retention times used for the characterization of nucleosides and their adducts are summarized in Extended table 2. For the identification of compounds, raw MS data was processed using the molecular feature extraction function in the MassHunter software, followed by metabolite searching through mass / isotope matching using the PCDL software (version B.07.00 build 7024.0) and the METLIN database (https://metlin.scripps.edu/index.php). For each nucleoside, precursor ions corresponding to the M+H, M+Na, M+K, 2M and base only species were extracted, and the most intense ion species observed for each nucleoside was used for quantitation. Identities of peaks eluting at 4.5 and 5.1 min (Fig. 1b and 3f) are shown in the Extended Data Fig. 9 and 10.

Subcutaneus xenografts

Animal work was done after approval by the UK Home Office and University of Oxford Local Ethical review. 106 cells in a 50% suspension of MatriGel (200 μl) were injected into 5-7 week old BALB/cOlaHsd-Foxn1nu/nu (Harlan) mice, 8 animals per group in each flank following the scheme: SN12C/H1299 left, SN12C shCDA8/H1299 dsRedCDA right. When the tumours reached palpable size, 8 mice were assigned to each treatment group: PBS, 100 mg/kg of 5hmdC and 100 mg/kg 5fdC. The compounds were administered every 72 h (4 doses in total). Tumour size was measured every 3 days by Vernier caliper and the animal cohort sacrificed when the cumulative tumour diameter in the first animal reached 12 mm. Tumour volume was calculated assuming that the tumours were spheres with the following formula: 4/3 π (D/2)3, in which D represents the diameter of the tumour.

Histology

Organs and tumours were collected and immediately 10% formalin fixed for 48 h. They were then embedded in wax and 4 μm thick sections cut. All sections were stained with H&E. Tumours were additionally stained with a Masson’s Trichrome Stain Kit (Sigma Aldrich) according to the manufacturer instructions.

Immunofluorescence of tissues and tumours

4 μm thick sections were subjected to antigen retrieval with a pressure cooker in Tris buffer pH 9 (10mM Tris base, 0.05% Tween 20). They were then blocked in 3% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes and incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C with the following antibodies: γH2A.X (Millipore, 05-636, 1:200) and PH3 (Millipore, 06-570, 1:200) or β-catenin (BD Transduction Laboratories, 610153, 1:250) and CDA (Sigma Aldrich, SAB1300717, 1:100). The slides were then washed vigorously 3 times in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with an appropriate secondary antibody, Alexa546 and Alexa488 conjugated (1:400, Life Technologies) and DAPI (Sigma Aldrich). Coverslips were then washed 3 times in PBS and mounted with mounting media (Vectashield). Images were acquired with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope with a 20× objective. For quantification of DNA damage and proliferation in tumours, tiled images with Z stacks were acquired to cover the entire central section of the tumour. Image J was used to quantify the immunofluorescence signal.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. DNA polymerase and nucleoside kinase activities on modified nucleosides.

a, MS confirmation of 5hmdC, 5fdC and 5cadC in the purchased nucleosides. b, HPLC-UV chromatogram of nucleosides from DNA extracted from H1299 cells transfected with 5hmdCTP. The abundance of 5hmdC relative to dG is illustrated in the right panel (n=3, standard deviation is shown, n.d.= not detected). c, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of recombinant purified DCK and CMPK1 enzymes used in the study. d, Two-dimensional TLC images of DCK reaction products. Dotted lines indicate reference points, which aid in tracking the migration localisation of the nucleosides. The monophosphate in each reaction is circled in red (representative picture, n=3). e, schematic map of nucleoside migration on two dimensional TLC plate (* indicates a background spot coming from ATP and used as a reference point)

Extended Data Figure 2. Stability of the nucleosides and CDA activity.

a,b Quantification of nucleosides by HPLC-UV during 10 days of incubation in water (a) and DMEM (b) at 37°C (n=3, standard deviation is shown). c, Representative HPLC-UV chromatograms at days 0, 2 and 10 with retention times indicated above each peak. d, Cell lines used in the study and their characteristics. e, Western blot showing knock-down of CDA by sh-RNA in the SN12C cell line. Right panel illustrates the growth of the cell line during treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC (n=3, standard deviation is shown). f, Western blot showing expression of CDA in wt and lentivirally transduced MCF7 cell line. Growth curve after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC is shown on the right (n=3, standard deviation is shown). g, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of recombinant purified CDA enzyme used in this study. h, HPLC-UV chromatograms showing the retention times and identity of substrates and CDA catalysed products. i, List of Km, kcat and vmax values of catalytic activity of CDA catalysing the deamination of cytidine variants.

Extended Data Figure 3. Mechanism of CDA catalysed deamination of epigenetic nucleosides, their cytotoxicity and dUTPase activity.

a, Molecular docking of dC, 5hmdC and 5fdC on the CDA active site (PDB 1MQ0). The detailed view of the catalytic pocket is shown with the modified nucleoside in the centre. Chains A, B and C indicate units of the tetramer, which CDA forms to deaminate four nucleosides. Thin yellow lines show compatible distances for the formation of hydrogen bonds. b, Growth curves of H1299 and MCF7 cell lines treated with 10 and 1 μM of dC, 5hmdU and 5fdU over a period of 10 days (n=3, standard deviation is shown). c, Coomassie stained gel demonstrating recombinant purified DUT (MW=18 kDa) and in vitro measurements of dUTPase activity using non canonical uridine triphosphates (n=3, standard deviation is shown). d, Extracted ion chromatogram of nucleoside standards analysed by HPLC-QToF mass spectrometry. Each nucleoside intensity was measured using the merged m/z values of the M+H+, M+Na+, M+K+, 2M+H+ and Base+H+ and a symmetric single m/z expansion of +/− 0.02. e, The most prominent ion of 5hmdU was identified in 5hmdC treated MDA-MB-231 cells.

Extended Data Figure 4. Mass spectrometry identification of 5fUra and UV quantitation of 5hmdU in the DNA.

a, Extracted ion chromatogram of nucleoside standards with 5fdU analysed by HPLC-QToF mass spectrometry (as in Extended data Fig. 3d). b, Weak, but consistent signal of 5fUra is identified in DNA of 5fdC treated MDA-MB-231 cells, but not dC treated cells or buffer alone. Two representative examples are shown. c, Relative quantification of 5fUra signal from three biological MS replicates (standard deviation is shown). d, Relationship between measured 5hmdU/T in the DNA of cell lines treated with 10 μM 5hmdC for 3 days and CDA expression levels. The cell lines used in this study are in coloured font (n=3, standard deviation is shown).

Extended Data Figure 5. Effect of 5hmdC administration on the cell cycle and DNA damage.

a,b, Propidium iodide FACS assay of the cell cycle. Shown are two representative plots (a) of MDA-MB-231 cells at day 3 of treatment with dC and 5hmdC (10 μM) and (b) quantification for all the cell lines analysed (n=3, standard deviation is shown). Two way ANOVA: p (S: 5hmdC vs dC MDA-MB-231) = 0.0027, p (G2-M: 5hmdC vs dC MDA-MB-231) =0.0149. HOP-92 p<0.0001, p (S: 5hmdC vs dC Capan-2) = 0.0005, p (G2-M: 5hmdC vs dC Capan-2) <0.0001 (n=3, standard deviation is shown, 10,000 events acquired). c, γH2AX immunofluorescence in MDA-MB-231 and H1299 cell lines at day 3 after treatment with 10 μM 5hmdC or dC. Scale bar = 50μm. d, Fraction of cells showing a γH2AX signal above background (n=3, standard deviation is shown). ANOVA with Sidak correction for multiple comparisons: p (5hmdC vs dC MDA-MB-231) =0.0208, p (5hmdC vs dC HOP-92) =0.0135.

Extended Data Figure 6. Quantification of intracellular nucleotides by ion-pair HPLC and SMUG1 glycosylase activity.

a, Illustrative chromatogram of all standards indicated in b mixed together. b, Retention times of nucleotides were determined by analysing each standard separately and are indicated in the table. c, An average relative abundance of NTP and dNTP levels in cells treated with dC, 5hmdC and 5fdC (n=3, error bars represent SD). d, Representative chromatograms of indicated experiments (blue) overlaid with standards separated on the same run (red). e, Typical image of denaturing PAGE electrophoresis of DNA incubated with SMUG1 and cleaved with APE1. f, Quantification of the DNA oligonucleotides with excised bases. g, expression of SMUG1 and uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG) in MDA_MB_231, SN12C and Capan-2 cell lines (Genevestigator).

Extended Data Figure 7. CDA expression in human cancer and normal tissues and toxicity evaluation of 5hmdC and 5fdC in mice.

a, CDA overexpression in pancreatic cancer (t-test, p<0.0001). b, CDA expression across a panel of cancer (red) versus normal (green) tissues (GENT database). Arrows indicate cancer types with an evident difference between normal (N) and cancerous tissues (C). c, 5hmdC and 5fdC detection in the blood (MS) of intraperitoneally injected mice at 30 minutes post injection. d, Label free MS quantification of 5hmdC in the blood of animals injected with doses of 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg (standard error of the mean is shown, n=3 (100 mg/ml), n=4 (25 and 50 mg/ml)). e, Immunohistochemistry showing CDA expression in the intestine. Scale bar = 50 μm. f, Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the intestine of mice injected with PBS and 100 mg/kg of 5hmdC and 5fdC. Tissue was removed 5 days after the injection. Scale bar = 50 μm. g, Immunofluorescence evaluation of proliferation (H3PS10) and DNA damage (γH2AX) in the intestine of mice treated with PBS and 100 mg/kg of 5hmdC and 5fdC 5 days after treatment. In parallel, the protocol was done on testis of irradiated mice, where positive signals for γH2AX were observed (data not shown). Scale bar = 50 μm. h, Weight of the mice plotted over the treatment period (n=16 per group).

Extended Data Figure 8. Evaluation of wt SN12C cell line and CDA knock-down in a mouse xenograft model.

a, Schematic illustration of xenograft establishment and treatment with nucleoside variants. b, Tumour diameter was measured by Vernier Caliper and volume calculated by assuming that tumours were spheres (n=8, standard deviation is shown, two way ANOVA with repeated measures and Holm-Sidak correction, p value<0.0001). c, Photos of the dissected tumours (* indicates dissected lymph nodes found after histological analysis). d, Western blot showing CDA expression in tumours extracted from mice. e, Quantification of proliferation (H3PS10) and DNA damage (γH2AX) using confocal microscopy and ImageJ of the central section of the tumour. Scale bar = 50 μm (n=4, standard deviation is shown, one way ANOVA, SN12C H3PS10 p=0.0033 for PBS compared with 5hmdC and p=0.0046 with 5fdC, γH2AX p=0.0003 for PBS compared with 5hmdC and p=0.0436 with 5fdC; SN12CshCDA_8 p=0.0130 for PBS compared with 5hmdC). f, 5hmdU quantified from a HPLC-UV chromatogram of nucleosides from DNA extracted from tumours of mice treated with 5hmdC and PBS (n=4, standard deviation is shown, one way ANOVA p=0.0041).

Extended Data Figure 9. Identification and quantification of compounds resulting peaks in HPLC-UV.

a, The abundance of molecule eluting at 5.1 min (5.7 min on the HPLC-QToF) is not significantly different between dC and 5hmdC treated samples. It is a common component of DNA hydrolysis buffer. b, 5mCyt in the DNA does not change after treatment with 5hmdC. Identity of 5mdC in the samples is confirmed by HPLC-QToF MS.

Extended Data Figure 10. Identification and quantification of compounds resulting peaks in HPLC-UV.

Compound eluting at 4.5 min (5.0 min on the HPLC-QToF) is an abundant component of DNA hydrolysis buffer generating a m/z of 202.18.

Extended data Table 1.

Extended data Table 2.

| Name | Formula | RT | m/z | Mass | Mass (DB) | Diff (DB, mDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2′deoxycytidine | C9 H13 N3 O4 | 2.854 | 228.1019 | 227.0941 | 227.0906 | −3.48 |

| 2′-Deoxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)cytidine | C10 H15 N3 O5 | 3.231 | 258.1139 | 257.1061 | 257.1012 | −4.92 |

| 2′-Deoxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)uridine | C10 H14 N2 O6 | 4.253 | 259.0967 | 258.0889 | 258.0852 | −3.76 |

| 2′-Deoxyuridine | C9H12N2O5 | 4.074 | 229.0883 | 228.0805 | 228.0746 | −5.9 |

| 2′-Deoxy-5-methylcytidine | C10 H15 N3 O4 | 5.845 | 242.117 | 241.1092 | 241.1063 | −2.94 |

| 2′-Deoxyguanosine | C10 H13 N5 O4 | 6.055 | 268.1072 | 267.1 | 267.0968 | −3.23 |

| 2′-Deoxy-5-formylcytidine | C10 H13 N3 O5 | 6.995 | 256.097 | 255.0892 | 255.0855 | −3.73 |

| 2′-Deoxythymidine | C10 H14 N2 O5 | 7.564 | 243.1017 | 242.0939 | 242.0903 | −3.59 |

| 2′-Deoxyadinosine | C10 H13 N5 O3 | 9.331 | 252.112 | 251.1049 | 251.1018 | −3.04 |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Ludwig Cancer Research and BBSRC for funding; Prof. Rob Klose, Dr. Thomas Milne, Dr Gareth Bond, Dr. Mary Muers and members of the Kriaucionis laboratory for the valuable discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Mark Shipman for his technical assistance in image acquisition and analysis; Indrika Ratnayaka and Richard Lisle for assistance with histology; Stephen Laird and Jordan Tanner for help with animal experiments; Prof. Xin Lu, Dr. Serena Lunardi and Dr. Gareth Bond for providing cell lines; Panagis Filippakopoulos for advice on molecular docking. Benedikt Kessler was supported by the John Fell Fund 133/075 (BMK) and the Wellcome Trust 097813/Z/11/Z.

References

- 1.Riggs AD. X inactivation, differentiation, and DNA methylation. Cytogenetics and cell genetics. 1975;14:9–25. doi: 10.1159/000130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wigler M, Levy D, Perucho M. The somatic replication of DNA methylation. Cell. 1981;24:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruenbaum Y, Cedar H, Razin A. Substrate and sequence specificity of a eukaryotic DNA methylase. Nature. 1982;295:620–622. doi: 10.1038/295620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilpo JA, Vilpo LM. Nucleoside monophosphate kinase may be the key enzyme preventing salvage of DNA 5-methylcytosine. Mutation research. 1993;286:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90186-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jekunen A, Puukka M, Vilpo J. Exclusion of exogenous 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine from DNA in human leukemic cells. A study with [2(−14)C]- and [methyl-14C]5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine. Biochemical pharmacology. 1983;32:1165–1168. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jekunen A, Vilpo JA. 5-Methyl-2′-deoxycytidine. Metabolism and effects on cell lethality studied with human leukemic cells in vitro. Molecular pharmacology. 1984;25:431–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. doi:10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tahiliani M, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. doi:10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito S, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. doi:10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaffeneder T, et al. The discovery of 5-formylcytosine in embryonic stem cell DNA. Angewandte Chemie. 2011;50:7008–7012. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103899. doi:10.1002/anie.201103899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frese KK, et al. nab-Paclitaxel potentiates gemcitabine activity by reducing cytidine deaminase levels in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:260–269. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0242. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loffler M, Fairbanks LD, Zameitat E, Marinaki AM, Simmonds HA. Pyrimidine pathways in health and disease. Trends in molecular medicine. 2005;11:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershey HV, Stieber JF, Mueller GC. Dna synthesis in isolated HeLa nuclei. A system for continuation of replication in vivo. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1973;34:383–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arner ES, Eriksson S. Mammalian deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1995;67:155–186. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boissan M, et al. The mammalian Nm23/NDPK family: from metastasis control to cilia movement. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2009;329:51–62. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0120-7. doi:10.1007/s11010-009-0120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Johansson M, Karlsson A. Human UMP-CMP kinase 2, a novel nucleoside monophosphate kinase localized in mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:1563–1571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707997200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M707997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin KT, Momparler RL, Rivard GE. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of chemical stability of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 1981;70:1228–1232. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600701112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petitjean A, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Human mutation. 2007;28:622–629. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. doi:10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross DT, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nature genetics. 2000;24:227–235. doi: 10.1038/73432. doi:10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barretina J, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. doi:10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabel CS, et al. AID/APOBEC deaminases disfavor modified cytosines implicated in DNA demethylation. Nature chemical biology. 2012;8:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1042. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung SJ, Fromme JC, Verdine GL. Structure of human cytidine deaminase bound to a potent inhibitor. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2005;48:658–660. doi: 10.1021/jm0496279. doi:10.1021/jm0496279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boorstein RJ, Chiu LN, Teebor GW. A mammalian cell line deficient in activity of the DNA repair enzyme 5-hydroxymethyluracil-DNA glycosylase is resistant to the toxic effects of the thymidine analog 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine. Molecular and cellular biology. 1992;12:5536–5540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weizman N, et al. Macrophages mediate gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by upregulating cytidine deaminase. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.357. doi:10.1038/onc.2013.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eliopoulos N, Cournoyer D, Momparler RL. Drug resistance to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine, and cytosine arabinoside conferred by retroviral-mediated transfer of human cytidine deaminase cDNA into murine cells. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 1998;42:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s002800050832. doi:10.1007/s002800050832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin T, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to decitabine in the myelodysplastic syndrome. PloS one. 2011;6:e23372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023372. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei H, et al. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer cell. 2009;16:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.016. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin G, et al. GENT: gene expression database of normal and tumor tissues. Cancer informatics. 2011;10:149–157. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S7226. doi:10.4137/CIN.S7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gad H, et al. MTH1 inhibition eradicates cancer by preventing sanitation of the dNTP pool. Nature. 2014;508:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13181. doi:10.1038/nature13181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber KV, et al. Stereospecific targeting of MTH1 by (S)-crizotinib as an anticancer strategy. Nature. 2014;508:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature13194. doi:10.1038/nature13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsahoye BH. Nearest-neighbor analysis. Methods in molecular biology. 2002;200:9–15. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-182-5:009. doi:10.1385/1-59259-182-5:009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Rompay AR, Johansson M, Karlsson A. Phosphorylation of deoxycytidine analog monophosphates by UMP-CMP kinase: molecular characterization of the human enzyme. Molecular pharmacology. 1999;56:562–569. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincenzetti S, Cambi A, Neuhard J, Garattini E, Vita A. Recombinant human cytidine deaminase: expression, purification, and characterization. Protein expression and purification. 1996;8:247–253. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0097. doi:10.1006/prep.1996.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung SJ, Fromme JC, Verdine GL. Structure of human cytidine deaminase bound to a potent inhibitor. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2005;48:658–660. doi: 10.1021/jm0496279. doi:10.1021/jm0496279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. doi:10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W270–277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Planck SR, Mueller GC. DNA chain growth in isolated HeLa nuclei. Biochemistry. 1977;16:2778–2782. doi: 10.1021/bi00631a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershey HV, Stieber JF, Mueller GC. Dna synthesis in isolated HeLa nuclei. A system for continuation of replication in vivo. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1973;34:383–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kemmerich K, Dingler FA, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Germline ablation of SMUG1 DNA glycosylase causes loss of 5-hydroxymethyluracil- and UNG-backup uracil-excision activities and increases cancer predisposition of Ung−/−Msh2−/− mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6016–6025. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks259. doi:10.1093/nar/gks259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. doi:10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dietmair S, Timmins NE, Gray PP, Nielsen LK, Kromer JO. Towards quantitative metabolomics of mammalian cells: development of a metabolite extraction protocol. Anal Biochem. 2010;404:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.04.031. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacKenzie CJ, Shioda T. COS-1 cells as packaging host for production of lentiviruses. Current protocols in cell biology / editorial board, Juan S. Bonifacino … [et al.] 2011 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2607s50. Chapter 26, Unit 26 27, doi:10.1002/0471143030.cb2607s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barretina J, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. doi:10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfister TD, et al. Topoisomerase I levels in the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel determined by validated ELISA and microarray analysis and correlation with indenoisoquinoline sensitivity. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:1878–1884. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0016. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross DT, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nature genetics. 2000;24:227–235. doi: 10.1038/73432. doi:10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]