Abstract

The first enzyme in the oxalocrotonate branch of the naphthalene-degradation lower pathway in Pseudomonas putida G7 is NahI, a 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase required for conversion of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde to 2-hydroxymuconate in the presence of NAD+. NahI is in one family of the NAD(P)+-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily (ALDH8). In this work, we report the cloning, expression, purification and preliminary structural and kinetic characterization of the recombinant NahI. The nahI gene was subcloned into a T7 expression vector and the enzyme was overexpressed in Escherichia coli ArcticExpress at 12 ºC as an N-terminal hexa-histidine-tagged fusion protein (6xHis-NahI). After the soluble protein was purified by affinity and size-exclusion chromatography, dynamic light scattering and small-angle X-ray scattering experiments were conducted to analyze the oligomeric state and the overall shape of the enzyme in solution. The protein is a tetramer in solution and has nearly perfect 222 point group symmetry. Protein stability and secondary structure content were also evaluated by a circular dichroism spectroscopy assay under different thermal conditions. Furthermore, kinetic assays were conducted for the recombinant enzyme and, for the first time, KM (1.3 ± 0.3 μM) and kcat (0.9 s−1) values were determined for this enzyme (at presumed NAD+ saturation). NahI is highly specific for its biological substrate (2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde) and has no activity with salicylaldehyde, another intermediate in the naphthalene-degradation pathway.

Keywords: Pseudomonas putida G7, naphthalene degradation, 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, structure, kinetics

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of hydrophobic organic compounds consisting of two or more fused aromatic rings in linear or angular arrangements. They are widely distributed in the environment due to natural as well as anthropogenic sources [1]. Members of this group include naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene, and benzo[a]pyrene, among others.

Naphthalene is the simplest and most abundant PAH, and serves as a model compound for PAH studies. The toxicity of naphthalene has been well documented. It has been suggested that naphthalene undergoes metabolic activation to 1,2-naphthoquinone, which reacts with DNA and leads to the formation of depurinating adducts. The abasic sites in DNA formed by loss of the depurinating adducts can generate mutations that might initiate cancer [2].

Due to their ubiquitous occurrence, potential to bio-accumulate and carcinogenic activity, PAHs are significant environmental concerns [3]. The US Environmental Protection Agency has listed 16 PAHs as priority pollutants for remediation [4] highlighting the importance of their removal from the environment.

Owing to the relatively high cost and the non-specificity of conventional physical and chemical environmental decontamination methods, bioremediation is a promising strategy for environmental cleanup [5]. It is a safe, less disruptive and cost-effective treatment to remove toxic compounds from the environment [6]. In the past few years, enzymatic bioremediation has resurfaced as an attractive alternative to augment currently available bio-treatment techniques. The process starts with a search for microorganisms capable of feeding on a particular pollutant, and then focuses on the identification of the enzymes responsible for degradation [7].

A wide phylogenetic diversity of bacteria such as species of the genus Alcaligenes, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, and Nocardia is capable of aerobic degradation of aromatic compounds into less toxic or non-toxic products [8]. Pseudomonas species and closely related organisms have been the most extensively studied due to their superior performance in degrading PAHs as sole carbon and energy sources [8, 9].

The gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas putida strain G7 harbors an 83 kilobase plasmid associated with naphthalene metabolism, NAH7 [10]. The naphthalene catabolic genes (nah) of NAH7 are organized into two operons. The nah operon (nahAaAbAcAdBFCED) encodes the upper pathway enzymes involved in the conversion of naphthalene to salicylate. The latter results from the oxidation of salicylaldehyde by the action of salicylaldehyde dehydrogenase (NahF), the last enzyme of the upper pathway [11]. On the other hand, the sal operon (nahGTHINLOMKJ) codes for the lower pathway enzymes involved in the conversion of salicylate to pyruvate and acetaldehyde [10, 12]. The lower pathway starts with the oxidation of salicylate to catechol by salicylate hydroxylase (NahG), which is extradiol-cleaved by catechol-2,3-dioxygenase (NahH) and further transformed to pyruvate and acetyl-CoA by the remaining meta-cleavage pathway gene products (NahI, NahJ, NahK, NahN, NahL, NahM, and NahO) [13] (Figure 1).

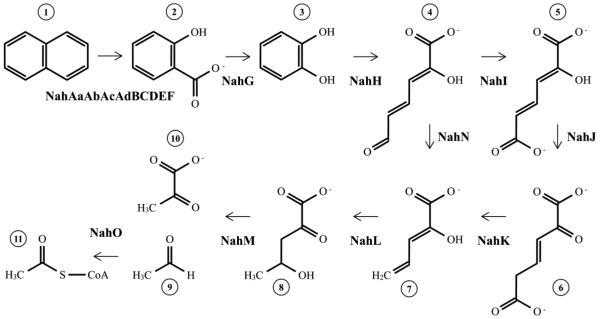

Figure 1.

Naphthalene-degradation lower pathway (from salicylate to pyruvate and acetyl-CoA). This pathway is composed of the enzymes salicylate hydroxylase (NahG), catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (NahH), 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NahI), 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase (NahJ), 4-oxalocrotonate decarboxylase (NahK), 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde hydrolase (NahN), 2-oxopent-4-enoate hydratase (NahL), 4-hydroxy-2-oxopentanoate aldolase (NahM), and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (NahO). The main substrates and products for these enzymes are also depicted. The metabolites are: naphthalene (1), salicylate (2), catechol (3), 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde (4), 2-hydroxymuconate (5), 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate (6), 2-hydroxy-2,4-pentadienoate (7), 4-hydroxy-2-oxopentanoate (8), acetaldehyde (9), pyruvate (10), and acetyl-CoA (11).

NahI from P. putida G7 (2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase – NCBI entry YP_534834.1; 486 amino acid residues and 51,517 Da), the first enzyme in the oxalocrotonate branch of the naphthalene-degradation lower pathway, belongs to the NAD(P)+-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily, according to the Conserved Domain Database classification (CDD; [14]). The members of this superfamily (SF) catalyze the oxidation of a wide variety of endogenous and exogenous aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids using NAD+ or NADP+ as a cofactor. They share the same scaffold and many conserved residues with important catalytic roles despite their overall low sequence identity (below 15%), modes of oligomerization and substrate specificity.

Within the ALDH-SF, NahI is further classified into the ALDH8 family together with different 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenases (2-HMSDs; e.g., XylG from P. putida mt-2 – NCBI entry P23105.1, AphC from Comamonas testosteroni TA441 – NCBI entry BAA88501.1, TomC from Burkholderia cepacia G4 – NCBI entry AAP32788.1) and other enzymes (e.g., human aldehyde dehydrogenase family 8 member A1 protein or ALDH8A1 – NCBI entry Q9H2A2.1, 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli C – NCBI entry CAA86041.1). ALDH8 members share an overall sequence identity above 30% and, as reported in the literature, they catalyze reactions with different substrates. While NahI is thought to participate only in the conversion of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde to 2-hydroxymuconate using NAD+ as a cofactor (EC 1.2.1.85; [15, 16], XylG, another 2-HMSD involved in toluene and xylene degradation, oxidizes not only 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde, but also aromatic substrates such as benzaldehyde and its analogs [17]. Furthermore, human ALDH8A1, another ALDH8 member, converts 9-cis-retinal to 9-cis-retinoic acid [18]. Therefore, it is likely that subtle differences in the substrate pocket of these enzymes are responsible for their diverse kinetic properties using a variety of aldehyde substrates [19].

In this work, we report the cloning and expression of recombinant NahI from P. putida G7 (hexa histidine-tag NahI; 6xHis-NahI). In order to characterize the secondary and quaternary structures of this enzyme in solution, we purified the recombinant protein and analyzed it by circular dichroism (CD), size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), dynamic light scattering (DLS) and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Furthermore, as a preliminary step to better understand the specificity of this enzyme, we performed kinetic assays with its biological substrate (2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde) and salicylaldehyde, another intermediate in the pathway. Taken together, these findings validate the NahI biological unit and substrate specificity, reinforcing its precise role in the naphthalene-degradation pathway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning

The coding region for 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NahI, NCBI Gene ID: 3974218) was amplified from the NAH7 plasmid by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using sense 5’-CATATGAAAGAGATCAAGCATTTC-3’ and antisense 5’-AAGCTTCAGGGATGCAGTCATG-3’ primers. The NdeI and HindIII restriction enzyme cloning sites are shown in bold, respectively. The PCR was carried out in a final volume of 60 µL containing 225 ng of template plasmid, 0.20 mM dNTPs, 1x Platinum Taq buffer, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 Unit Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and 0.6 µM of the forward and reverse primers. DNA was amplified using a thermal cycler with the following protocol: 95 ºC for 120 s in the first cycle; 95 ºC for 60 s, 47 ºC for 60 s and 68 ºC for 90 s; for 25 cycles. A final extension step was carried out at 68 ºC for 300 s.

The amplified product was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega Corporation) and the recombinant plasmid (pGEM-nahI) was inserted into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells, which were screened for positive clones by colony PCR using the sense and antisense primers for nahI amplification. DNA fragments obtained from the digestion of pGEM-nahI with NdeI and HindIII were ligated into pET28a(TEV) vector [20], previously digested with the same restriction enzymes, resulting in the recombinant expression vector pET28a(TEV)-nahI. pET28a(TEV) is a modified pET28a vector (Novagen) that adds a 6xHis-tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-cleavage site at the N-terminus of the target protein (MGHHHHHHENLYFQGH–target protein).

Eletrocompetent E. coli DH5α cells were transformed with pET28a(TEV)-nahI for storage while E. coli BL21 (DE3) and E. coli BL21 ArcticExpress (DE3) (Agilent Technologies) cells transformed with the same vector were used for protein expression. Plasmid DNA was extracted from cells using the AxyPrep Plasmid Miniprep kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Axygen Biosciences). Purification of PCR products or DNA fragments from agarose gel slices was carried out by using Ilustra GFX PCR DNA and the Gel Band Purification kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Gene insertion was verified by colony PCR and the fidelity of the nahI nucleotide sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing using T7 primers in a MegaBACE Sequencing System instrument (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

2.2. Protein Expression

Recombinant NahI was first overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells harboring the pET28a(TEV)-nahI plasmid. A single colony from an agar plate was used to inoculate 20 mL of 2xYT medium (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 50 µg/mL kanamycin. After overnight growth at 37 ºC with agitation at 200 rpm, this primary culture was used to inoculate 1 L 2xYT medium supplemented with the same antibiotic and allowed to grow at 37 ºC until the OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) reached 0.5 – 0.7. Protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. The cell culture was allowed to grow at 37 ºC for 3 h at 220 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 ºC.

In a second attempt to overexpress recombinant NahI, transformed E. coli BL21 ArcticExpress (DE3) cells were inoculated into a 20 mL 2xYT medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 20 µg/mL gentamicin and grown overnight (200 rpm at 37 ºC). This culture was then transferred to a 1 L 2xYT medium without antibiotics and grown at 30 ºC for 3 h. Subsequently, the temperature was reduced to 12 ºC and heterologous protein expression (6xHis tagged protein; 6xHis-NahI) was induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. Incubation proceeded for 24 h at 12 ºC before harvesting the cells by centrifugation (10,000 g for 10 min at 4 ºC).

The protein expression level was checked by Coomassie blue stained 12% or 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE).

2.3. Protein purification

Harvested cells were resuspended in 20 mL of buffer A (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl and 30 mM imidazole) and disrupted using an EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4 ºC. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm pore-size membrane filter and loaded onto a 5-mL Ni2+ affinity column HisTrap HP (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) connected to an ÄKTAprime chromatography system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Both the column and system were previously equilibrated with buffer A. In order to remove nonspecific binding proteins, the column was washed with five column volumes of buffer A. Subsequently, the recombinant protein (6xHis-NahI) was eluted with a linear imidazole gradient using a combination of buffers A and B (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole). Fractions containing 6xHis-NahI were pooled and buffer-exchanged into buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 and 50 mM NaCl) using the same ÄKTAprime system and a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

The 6xHis-NahI imidazole-free sample was then loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) size-exclusion chromatography column equilibrated with buffer D (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 50 mM NaCl) for a final purification step. Alternatively, samples were incubated with recombinant histidine-tagged TEV protease (5% w/w) at 4 ºC for 16h for 6xHis-tag removal. A second Ni2+ affinity chromatography step was then used to further separate untagged NahI (GH-NahI) from contaminants – including histidine-tagged TEV protease – prior to a final purification step.

Whenever required, tagged and untagged NahI samples obtained from SEC were concentrated by ultrafiltration using a Vivaspin sample concentrator (10 kDa MWC, GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Protein purity was checked by Coomassie blue stained 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE at all steps. The protein concentration at each purification step was determined from its absorbance at 280 nm using the appropriate extinction coefficient. The 6xHis-NahI and GH-NahI molar extinction coefficients (57,410 and 55,920 M−1.cm−1, respectively) were estimated from their amino acid composition by ProtParam tool [21] using the ExPASy Server [22].

2.4. Circular dichroism spectroscopy

The secondary structure content of GH-NahI in the presence or absence of NAD+ was assessed by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy using a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Corporation). Far UV CD spectra (190 – 260 nm) were recorded at a protein concentration of 0.3 mg/mL in the temperature range of 20-95 ºC, with a scan rate of 100 nm/min, a step size of 1.0 nm and 5 accumulations per scan. The same 0.5 mm path length quartz cuvette was used throughout the experiments. Spectra were baseline-corrected by subtracting the spectra of buffer solution (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 50 mM NaCl) from all measurements. Samples were clarified by centrifugation (13,000 g for 10 min at 4 ºC) before assays. The content of GH-NahI secondary structure elements was calculated with the program CDNN v.2.1 [23]. Assignments of the secondary structure elements from 3D structures of a few proteins deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [24] were obtained using the “STRIDE: Protein secondary structure assignment from atomic coordinates” server [25].

2.5. Enzymatic assays and kinetics

2-Hydroxymuconate semialdehyde was generated enzymatically using partially purified catechol-2,3-dioxigenase (C23O) [26, 27], as follows. Catechol (200 mg, 1.8 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (30 mL, pH 7.5). To this mixture was added a 100-μL aliquot of C23O (11.5 mg/mL). Pure oxygen gas was bubbled directly into the reaction as it stirred in order to enhance activity. Subsequently, aliquots (50 μL) of C23O were added every 15 min (4×) and the pH adjusted to 7.3-7.6 with aliquots of 1 M NaOH. The reaction was complete when the pH no longer required adjustment, indicating that the acid was no longer being generated. As the reaction progressed, a yellow color appeared, which turned to deep red, indicative of the formation of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde. The solution was acidified to pH ~2 with 8.5% phosphoric acid and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL). The organic layers were pooled, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness at room temperature. The resulting solid was dissolved in ethyl acetate and recrystallized. The compound is stable at room temperature as a solid. A 1H NMR spectrum in deuterated methanol indicates that the cyclic acetal of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde is isolated. However, in aqueous buffer at pH 8.0, only the ring-opened form of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde is present. The yield of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde was 48 mg (0.3 mmol, 17%). Cyclic Acetal: 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 5.61 (1H, d, H6, J = 3.9 Hz), 5.82 (1H, ddd, H5, J = 1.1, 3.9, 9.5 Hz), 6.35 (1H, dd, H4, J = 6.1, 9.5 Hz), 6.54 (1H, dd, H3, J = 1.1, 6.1 Hz) ppm; 13C NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 96.76 (C6), 109.16 (C3), 120.15, 123.39 (C4, C5), 141.66 (C2), 164.54 (C1) ppm. Ring-opened compound 4 (in Figure 1): δ 5.65 (2H, m, H3 and H5), 7.52 (1H, t, H4, J = 13.37 Hz), 8.65 (1H, d, H6, J = 8.8 Hz) ppm.

2-Hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NahI) activity was monitored by following the rate of disappearance of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde at 375 nm (λmax = 22,966 M−1 cm−1). The production of NADH at 340 nm could not be observed due to substrate absorbance. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8.5, 50 mM NaCl, containing several concentrations of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde, 200 μM NAD+, and 0.003 mg/mL of enzyme. Both substrate and cofactor were dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8.5 before adding to the reaction mixture. The assay was initiated by addition of 2 to 40 μL of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde to a final reaction volume of 1.0 mL. All the spectrophotometric assays were performed in quartz cuvettes of 10 mm path length at 25 ºC, and data were obtained using an Agilent 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer. The Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters were fitted by non-linear regression of the initial velocities (vo) versus concentrations of the substrate 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde using GraFit program (Erathicus Software Ltd., Staines, U.K.).

The kinetic activity of NahI with salicylaldehyde, another intermediate in the naphthalene-degradation pathway, was also evaluated under similar conditions. However, activity was monitored by following the rate of formation of NADH at 340 nm.

2.6. Size-exclusion chromatography and dynamic light scattering analysis

A single 9 mL pool of GH-NahI (at 2.3 mg/mL), obtained after SEC, was used to prepare diluted and concentrated protein aliquots (0.5, 1.5 and 6 mg/mL). Each aliquot was separated into two fractions and NAD+ was added to one of them to a final molar concentration 10 times greater than that of protein, and incubated for an hour. Each fraction was then used in dynamic light scattering (DLS) and SEC experiments.

The DLS assays were performed at 25 ºC on a Zetasizer Nano ZS-90 (Malvern) instrument. Each sample was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4 ºC before the assay, in order to remove impurities or insoluble particles. Each sample was measured from 10 to 100 times (depending on the protein concentration) for 10 s in a 10 mm path length quartz cuvette. Data were collected and analyzed using Malvern Zetasizer software v. 6.01, where the “Protein Utility” routine was used to estimate particle mass based on hydrodynamic radius (Rh).

The same samples used in the DLS assays were evaluated by SEC. The samples were individually loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column equilibrated with buffer D using a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The chromatography profiles of GH-NahI in the presence or absence of NAD+ were compared with those of the following standards: cytochrome C (12.4 kDa), albumin (66 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa) and β-amylase (200 kDa).

2.7. Small-angle X-ray scattering

2.7.1. Data reduction and overall parameters

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) curves for GH-NahI samples in buffer D were recorded at the Laboratório Nacional de Luz Síncrotron (Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory, LNLS) at the SAXS-1 beam line, equipped with a Dectris Pilatus 300K detector (84 mm × 107 mm). Samples were centrifuged (13,000 g for 10 min at 4 ºC) prior to data collection. The sample-to-detector distance was set to 1617.34 mm and the radiation wavelength used was 1.55 Å, with q ranging from 0.0069 to 0.2692 Å−1 (q=4πsinθ/λ, where 2θ is the scattering angle). Potential radiation damage was monitored by collecting, for each sample, a series of consecutive curves with increasing exposure times (from 5-60 s). Data integration, normalization to the intensity of the transmitted beam and sample attenuation, and buffer scattering subtraction were carried out with Fit2D [28]. Absolute calibration of scattering data was performed using water as a secondary standard [29, 30]. Data analysis and plotting were performed with ATSAS 2.5.1.1 [31] and GNUPLOT (http://www.gnuplot.info) under Slackware Linux (http://www.slackware.com). Values for the radius of gyration (Rg) and the zero-angle scattering intensity (I(0)) were obtained both from the Guinier approximation [32] I(q) = I(0)exp(−q2Rg2/3), valid for qRg ≲ 1.3, and by the indirect Fourier transform method as implemented in the program GNOM [33]. The latter was used to calculate the pairdistance distribution function, P(r), from the scattering curve. The conformational state of the protein in solution was evaluated by a Kratky plot (q2I(q) × q) obtained directly from the scattering curve [34-36]. Estimates for the molecular mass of the scattering particles in solution were obtained by a method which is independent of protein concentration measurements, based on the Porod invariant, ∫0∞ q2I(q)dq (integration area under the Kratky plot) [37].

2.7.2. Protein structure prediction

CRYSOL [38] was used to fit the theoretical scattering curves computed for structures available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [24] to the experimental data measured for GH-NahI. In each case, the maximum distance observed in each structure was calculated with the program NCONT [39]. Once the most probable tetrameric arrangement of GH-NahI was determined (as being analogous to the PDB entry 4I1W), a three-dimensional model for GH-NahI monomer was predicted by threading using its amino acid sequence, as implemented in the I-TASSER platform [40]. The resulting monomer structure was then individually superposed onto each one of the four chains composing the biological unit, resulting in the final GH-NahI putative tetramer. The FoXS program [REF1 - doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.020 , REF2 - doi:10.1093/nar/gkq461] was used to calculate the theoretical scattering curves from dimer and tetramer models of NahI and its Minimal Ensemble calculation was used to estimate the percentage of each protomer in solution.

2.7.3. Ab initio shape recovery from SAXS curves

Forty dummy atom models for the GH-NahI tetramer were generated with DAMMIF [41] in mode slow, enforcing particle symmetry 222 (“P222” option in DAMMIF). Post-processing within the entire set of models was carried out both with DAMAVER [42] and DAMCLUST [31] for evaluation of model similarity and clustering of models, respectively. Superposition of models was done with SUPCOMB [43]. Visualization and graphical analysis of three-dimensional models were performed with RASMOL [44] and PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.1.1, Schrödinger, LCC). Computational jobs were automated with C shell scripts.

3. Results and discussion

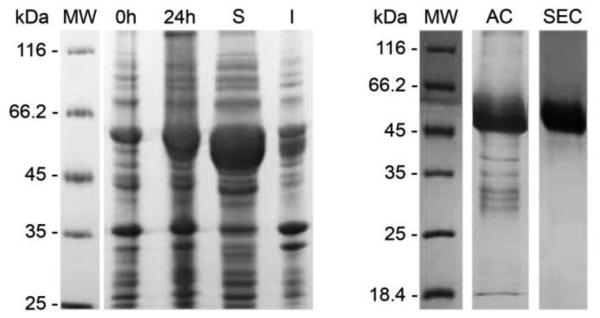

3.1. Expression and purification

The recombinant form of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase from P. putida G7 (6xHis-NahI) was first expressed at 37 ºC for 3h in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. This first protein expression attempt resulted in an insoluble 6xHis-NahI (data not shown). To overcome this, E. coli BL21 ArcticExpress (DE3) was chosen as an alternative bacterial strain for 6xHis-NahI expression at 12 ºC for 24h after induction with IPTG. These cells co-express the cold-adapted chaperonins Cpn10 and Cpn60 from Oleispira antarctica, which share 74% and 54% amino acid sequence identity to the E. coli GroEL and GroES chaperonins, respectively. They confer improved protein processing at lower temperatures (from 12 to 4 ºC), potentially increasing the yield of active and soluble recombinant protein [45]. As observed in SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 2), this expression protocol resulted in a pronounced fraction of soluble 6xHis-NahI, as shown by the large expression band around 55 kDa corresponding to the molecular mass of the 6xHis-NahI monomer (53,518 Da). Only a small portion of the recombinant enzyme was found in the insoluble fraction (Figure 2). Metal affinity chromatography (MAC; Ni2+-affinity) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) were used for protein purification which allowed the recovery of approximately 30 mg of pure 6xHis-NahI per liter of cell culture. After His-tag removal with TEV protease, the cleaved NahI enzyme (GH-NahI; 51,712 Da) contained two extra amino acid residues (glycine and histidine) at its N-terminus compared to the native NahI. GH-NahI remained soluble with no signs of protein aggregation or precipitation.

Figure 2.

Coomassie blue-stained 15% SDS–PAGE analysis of 6xHis-NahI expression in E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) and purification. Lane MW: Protein molecular weight marker; Lane 0h: crude bacterial extract before IPTG induction; Lane 24h: crude bacterial extract after 24h of induction with 1.0 mM IPTG; Lanes S and I: soluble and insoluble fractions, respectively, after cell lysis. Lanes AC and SEC: purified fractions of 6xHis-NahI after Ni2+-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

3.2. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

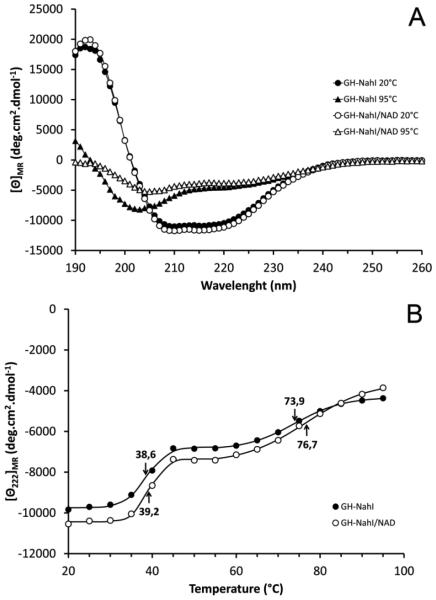

Circular dichroism spectroscopy was used to evaluate the proper folding of recombinant GH-NahI and the structural effects of temperature and NAD+ binding. For this purpose, GH-NahI obtained after SEC purification, in the presence or absence of NAD+, was independently evaluated at different temperatures (from 20-95 °C, in 5 °C increments) in a spectropolarimeter. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A. CD spectra of GH-NahI at 20 ºC and 95 ºC, in the absence and presence of NAD+, in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 50 mM NaCl. The protein concentration in both solutions is 0.3 mg/mL and the cell path lengths are 0.5 mm. B. CD melting curves recorded at 222 nm for GH-NahI and GH-NahI/NAD+ between 20 ºC and 95 ºC.

The CD spectra of GH-NahI at 20 °C, in the presence and absence of NAD+, are very similar to each other over the entire measured wavelength range (Figure 3A), with only a slight difference below 195 nm. This difference could be explained either by the higher level of noise in both sample and buffer spectra at this region or by a very small difference in the beta-sheet content between samples. The deconvolution of any of these two spectra using CDNN 2.0 software is insensitive to this small difference and both suggest GH-NahI is composed of 35% α-helices, 17% β-sheets and 46% other secondary structure elements (17% β-turns and 29% random coils). These results suggest that NAD+ binding to GH-NahI does not promote any significant conformational changes in the secondary structure of the enzyme. Moreover, they are in good agreement with the secondary structure content of 2-aminomuconate 6-semialdehyde (2-AMS) dehydrogenase from P. fluorescens (PDB ID 4I1W) which shares 61% sequence identity to GH-NahI and shows 43% α-helices and 22% β-sheets, as assigned by the STRIDE server [25]. Interestingly, NahI shows a similar fold to that of NahF (PDB ID 4JZ6) [46], a salicylaldehyde dehydrogenase from P. putida G7 belonging to the same naphthalene-degradation pathway. They share only 33% sequence identity, but NahF is composed of 43% α-helices and 20% β-sheets.

As the temperature is increased up to 95 °C, CD spectra are modified towards a partially unfolded protein profile resulting in the loss of GH-NahI α-helices content. Interestingly, the apo and holo (NAD+ bound) forms of the enzyme behave differently under thermal denaturation. This difference is more evident from 40 °C in the 195-210 nm range, with the greatest dissimilarities at 95 °C, as shown in Figure 3A. This difference suggests that NAD+ binding to NahI increases the stability of the complex due to the maintenance of a few β-strands in the NAD+ binding domain (most probable a Rossmann fold domain) during thermal denaturation. As β-strands have a positive contribution over the mean residue ellipticity ([θ]MR) in the 195-210 nm range, the GH-NahI/NAD+ CD curve is less negative than the curve observed when monitoring the enzyme alone.

In addition, when monitoring the mean residue ellipticity at a fixed 222 nm wavelength ([θ222]MR) as a function of temperature (Figure 3B) it can be seen that GH-NahI follows a two-step denaturation process with the first transition temperature at 38.6 °C and a second transition temperature at 73.9 °C. The GH-NahI/NAD+ complex also shows a two-step denaturation process but the binding of NAD+ to NahI has a greater impact only over the second transition temperature (76.7 °C). This behavior supports the idea that, in these both situations, the co-factor binding domain is the less susceptible to thermal denaturation.

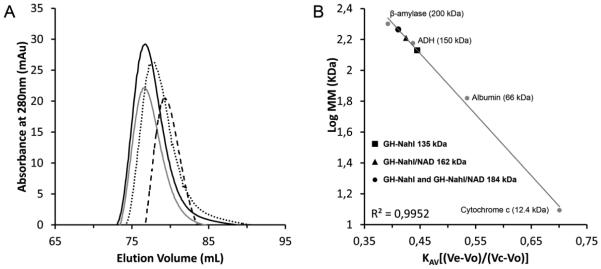

3.3. Size-exclusion chromatography and dynamic light scattering analysis

Size-exclusion chromatography and dynamic light scattering assays were conducted to indirectly evaluate the oligomeric state of GH-NahI in solution. SEC profiles obtained throughout this work using protein sample with and without NAD+ showed a single well-resolved peak corresponding to the enzyme elution volume (Ve). More than three chromatographic runs were conducted per sample (with and without NAD+). The elution volume in each run did not remain the same, even when using the same sample. GH-NahI and GH-NahI/NAD+ samples eluted between 76.7 and 79.3 mL, consistent with an apparent molecular mass of 184.3 to 135 kDa (Figure 4). These results suggest that NAD+ binding does not interfere with the biological assembly of NahI, which might be formed by three or four NahI monomers.

Figure 4.

A. Size-exclusion chromatography curves for GH-NahI in the absence (dashed line, Ve = 79.3 mL / grey solid line, Ve = 76.7 mL) and presence of NAD+ (dotted line, Ve = 77.8 mL, black solid line / Ve = 76.7 mL). B. Calibration curve generated using molecular weight standards.

The results obtained using dynamic light scattering also suggest that GH-NahI, either in the presence or absence of NAD+, might assemble as a trimer. GH-NahI and GH-NahI/ NAD+ behave as a particle with a hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) of 9.8 and 9.9 nm in solution, which for globular proteins might correspond to molecular masses of 139 and 142 kDa, respectively.

Even though these results suggest that GH-NahI might assemble as a trimer in solution, there is little evidence in the literature that ALDHs monomers associate like this. The known ALDHs assemble as dimers with interlaced domains, tetramers with two copies of dimers, or as a trimer-of-dimers hexamers [47, 48]. The theoretical molecular mass of GH-NahI monomer is 51.7 kDa, while the expected molecular masses for the dimer and the tetramer are 103.4 and 206.8 kDa, respectively. A similar situation was reported by He and co-workers [49], where gel filtration results suggested that 2-AMS dehydrogenase from P. pseudoalcaligenes might assemble as a trimer. However, the authors concluded that “because a homotrimeric structure is uncommon, more research is required to rigorously determine the native structure of the 2-AMS dehydrogenase” [49].

Therefore, as a final attempt to correctly identify the oligomeric state of GH-NahI and its overall shape in solution,+ a small-angle X-ray scattering experiment was conducted.

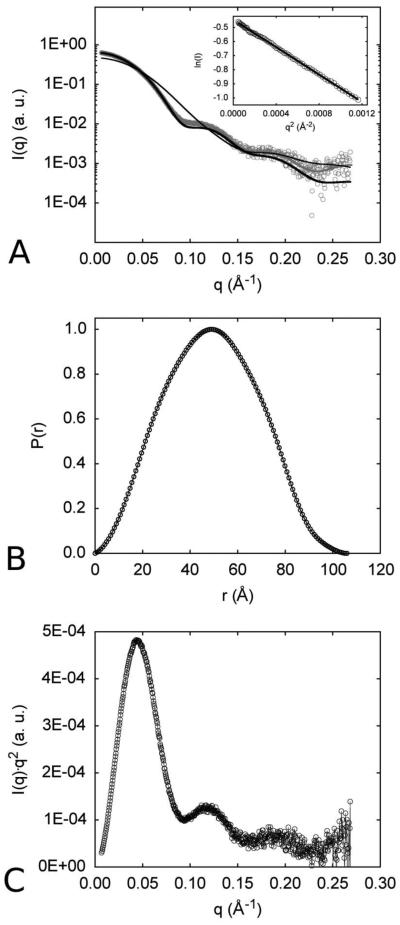

3.4. Small-angle X-ray scattering

3.4.1. Recombinant NahI is a tetramer in solution

To check for a possible dependence of the oligomeric state on protein concentration, three samples of GH-NahI were made up at different protein concentrations (1.5, 5.8 and 11.3 mg/mL) and analyzed. The results showed mass estimates equal to 185, 190, and 177 kDa, respectively. No evidence for higher order oligomers at increasing protein concentration was found. Within the inherent error of the technique [37], these results unequivocally indicate that GH-NahI is a tetramer in solution (predicted molecular weight equal to 206.8 kDa). This result agrees with the size-exclusion chromatography data (184 kDa) reported in section 3.3.

In all cases, radiation damage was only visible for longer (and cumulative) exposure times. Therefore, the first scattering curve collected with 20 s exposure time, from the sample at 5.8 mg/mL, shown in Figure 5A, was kept for further analysis due to its higher signal-to-noise ratio and reliability observed for mass determination procedure. The clear linear behavior of the Guinier plot (inset of Figure 5A) strongly suggests a monodisperse protein sample, allowing a reliable estimate of the radius of gyration as Rg = 38.2 Å. This value is in excellent agreement with that obtained with GNOM [33], Rg = 37.4 Å, during the calculation of the distance distribution 500 function, P(r), shown in Figure 5B. This P(r) function suggests a globular assembly in solution, with a maximum dimension equal to 106 Å. To complete this preliminary analysis, the Kratky plot presented in Figure 5C, with a clearly defined maximum and decay at higher angles, typical for well-folded domains, indicates that the protein has a compact structure in solution.

Figure 5.

SAXS data and overall parameters. A. Experimental Small-Angle X-ray Scattering curve (open circles) of GH-NahI in solution, with the GNOM [33] fitting (thicker line in grey) obtained during the computation of the pair-distance distribution function, P(r). The Guinier region and the corresponding linear fitting are shown in the inset. Theoretical SAXS curves for modeled NahI dimer (thin line in black) and tetramer (thicker line in black) were calculated with FoXS program (REF1 - doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.020 , REF2 - doi:10.1093/nar/gkq461) and fitted to SAXS experimental data. B. Pair-distance distribution function derived from the experimental curve. The bell-shaped profile, with a centered maximum, is typical of a globular scattering particle in solution. C. Kratky plot calculated from the experimental data; typical of compact proteins, with well-folded domains. A few negative intensity points resulting from buffer subtraction in the noisy region, at higher scattering angles, were deleted previously to FoXS calculations and for figures composition. Plots were done with GNUPLOT (http://www.gnuplot.info) and edited with GIMP (http://www.gimp.org) under Slackware Linux (http://www.slackware.com).

3.4.2. The most probable oligomeric assembly

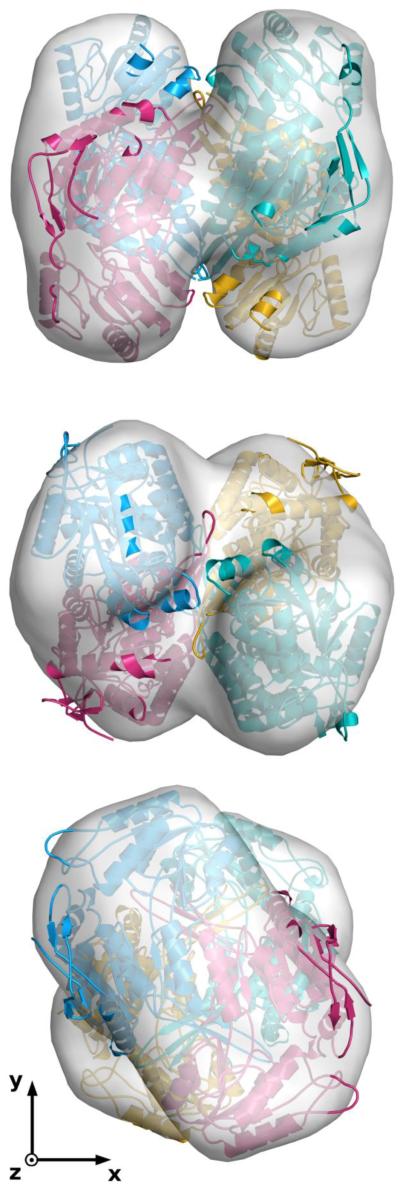

To restore the molecular envelope of GH-NahI from the scattering curve, it is important to know whether or not symmetry is present in its oligomeric assembly in solution. Thus, possible tetrameric arrangements were first investigated by using CRYSOL [38]. Theoretical scattering curves for the 12 closest homologues, whose structures were available in the PDB, were fitted to the experimental SAXS data measured for GH-NahI. Although these structures were determined by X-ray crystallography, it is worth noting that the content of the asymmetric unit (ASU) of the crystal does not necessarily correspond to the oligomeric state of the protein in solution. In the case of GH-NahI, however, it was not necessary to generate crystallographic symmetry mates to take into account other possible tetrameric arrangements because the tetramer contained in the ASU of the closest homologues already exhibited a good fit to the experimental data. In addition, the Rg calculated by CRYSOL and the maximum dimension obtained with NCONT [39] for the closest homologue structures were in excellent agreement with the corresponding experimental values for GH-NahI (data not shown). Further confirmation of the oligomeric state and monodispersity of the sample was obtained from a calculation of the minimal ensemble of molecular models required to best fit the experimental data (Figure 5A). A minimal ensemble search was performed using FoXS software (REF1 - doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.020 , REF2 - doi:10.1093/nar/gkq461) supposing the existence of a combination of dimer s and tetramer of NahI in solution. The percentage of tetramers in solution was estimated to be 99%. Altogether, this analysis indicated that GH-NahI is present as a tetramer in solution, assuming an arrangement compatible with the tetramer corresponding to the ASU content of the PDB entry 4I1W (2-AMS dehydrogenase from P. fluorescens, with an amino acid sequence identity of 61%).

The 3D model of the PDB entry 4I1W possesses a nearly perfect 222 symmetry, with three mutually almost-perpendicular, nearly 2-fold, rotation axes. It is known that the solution resulting from the shape determination of the SAXS curves is not unique, and, in some cases, the reliability of this procedure may be increased by the addition of information which includes particle symmetry and/or anisometry. Reconstruction of the NahI tetramer using DAMMIF [41] was done without restricting the particle symmetry ( “P1” option), by imposing a two-fold (“P2” option) axis or three perpendicular 2-fold rotation axes (“P222” option). The latter option significantly improved the stability and reproducibility of the solution.

The similarity among the reconstructed models was initially assessed by calculating the normalized spatial discrepancy (NSD) parameter as performed by the program suite DAMAVER [42] (once more, enforcing 222 symmetry). For an ideal superposition, a NSD value of 0 implies very similar objects while values greater than 1 indicate that systematic differences occur [43]. In the present case, a NSD = 0.92 ± 0.07 indicated that the ensemble exhibits acceptable internal agreement, but with a visible variability emerging from different portions of the dummy atom (reconstructed) models. This characteristic is a consequence of the expected diversity resulting from the enforced particle symmetry. Therefore, to evaluate more efficiently the variability and uniqueness of the solutions, all models were clustered into groups by using the NSD criteria within the program DAMCLUST [31]. The total set of 40 dummy atom models could be optimally grouped into 9 clusters. For the 7 non-isolated clusters obtained, the average NSD value calculated for each member cluster against the respective representative model was 0.55 ± 0.09, thus indicating the procedure resulted in clusters containing highly similar models.

To interpret the resulting experimental low resolution models derived from the SAXS curve and to gain further insight into the biological problem under investigation, the 3D model in PDB entry 4I1W was used as a template to assemble a putative NahI tetramer based on monomer chains predicted by the I-TASSER server [40], which was subsequently used as a guide to visually scrutinize the dummy atom clusters. Even though virtually all clusters individually resembled in some degree the expected NahI tetramer, a striking result was obtained for a single cluster, easily recognizable by its well-marked 222 symmetry, which was exceptionally similar to that exhibited by the putative NahI model, as can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Superposition of the experimental envelope (shown as a surface) onto the predicted NahI tetramer, represented as a cartoon with monomer chains shown in different colors. The middle and bottom views are rotated clockwise by 90° around the x- and y-axes, respectively. The axes of the coordinate system of the page were chosen to make evident the striking coincidence of the envelope symmetry, with the nearly perfect 222 point-group symmetry of the tetramer. Drawings were prepared with PyMOL and edited using GIMP (http://www.gimp.org) under Slackware Linux (http://www.slackware.com).

3.5. Enzymatic assays and kinetics

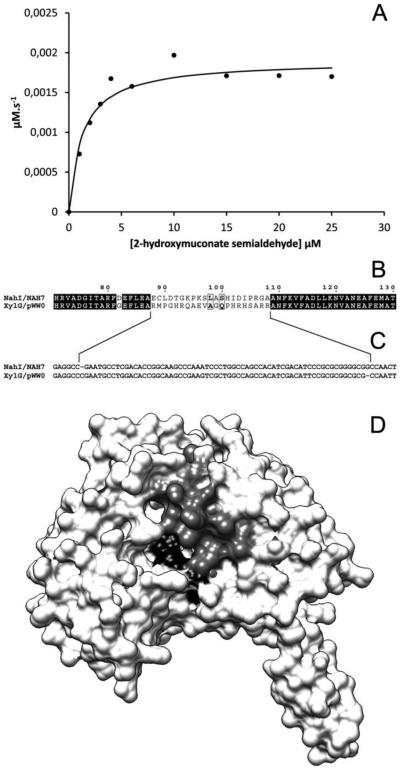

The kinetic constants for the recombinant GH-NahI were estimated using 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde as the variable substrate and NAD+ fixed at a presumed saturating concentration of 0.2 mM. The 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase activity was measured at 25 °C by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 375 nm corresponding to the decrease in the concentration of substrate. A plot of the initial velocities [vo] of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction versus the substrate concentrations [2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde] (Figure 7A) shows that the enzyme follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Analysis of the experimental data gave Km and kcat values of 1.3 ± 0.3 µM and 0.9 s−1, respectively. The resulting kcat/Km value of 0.66 × 106 M−1s−1 is marginally lower than that observed for XylG from P. putida mt-2 (kcat/Km = 1.6 × 106 M−1s−1) [17].

Figure 7.

A: Kinetic activity of the recombinant GH-NahI/NAD+ complex with 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde. A plot of the initial velocities [vo] of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction versus the concentration of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde shows that the enzyme follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics. B and C: Partial amino acid and nucleotide sequence alignment between NahI and XylG. A notable difference extending over 21 consecutive amino acid residues (Ala-87 to Ala-109) may be responsible for the different kinetic behavior observed for XylG (B). An insertion and a deletion mutation flanking this different fragment might have produced a reading frameshift (C). Predicted NahI monomer showing that the fragment (Ala-87 to Ala-109 colored in grey) stands in the vicinity of the predicted catalytic site (black).

Surprisingly, GH-NahI does not show any activity (under the experimental conditions) with salicylaldehyde whereas the corresponding enzyme in P. putida mt-2 is able to oxidize aromatic aldehydes, although with lower specificity (0.8 – 30 × 104 M−1s−1) [17].

A comparison between NahI (P. putida G7) and XylG (P. putida mt-2) amino acid sequences and the use of the predicted NahI monomer structure obtained in this work provide one possible explanation for this different type of behavior. These enzymes exhibit primary structure identity of 87.6% over the entire polypeptide chain. They show a remarkable difference extending over 21 consecutive amino acid residues (between Ala-87 and Ala-109; NahI numbering). NahI (P. putida G7) shows the following amino acid sequence 87-AECLDTGKPKSLASHIDIPRGAA-109 and XylG (P. putida mt-2) contains 87-ARMPGHRQAEVAGQPHRHSARRA-109, without any similarities (Figure 7 B). This region (Ala-87 to Ala-109) in the modeled structure is located around the predicted catalytic site (Figure 7 D), suggesting a possible role in substrate specificities. To date, there are no three-dimensional structures for NahI or XylG available in the PDB.

Harayama and Rekik [50] proposed that the meta-cleavage pathway of the TOL plasmid pWW0 from P. putida mt-2 is composed of hybrid genes evolved from a recombination product of the ancestral homologues nah (NAH7 from P. putida G7) and dmp (pVI150 from P. putida CF600) sequences. Since naturally occurring TOL and NAH plasmids often contain multiple meta-cleavage pathway operons whose nucleotide sequences are similar but not identical, in organisms containing these TOL and NAH plasmids, the chance of recombination between non-identical meta-cleavage pathway genes may be significant [50]. Thus, it is tempting to suggest that this fragment might have been incorporated into the xylG gene leading to a dramatic change in the specificity of this enzyme. However, a comparison of nahI and xylG nucleotide sequences revealed that an insertion and a deletion mutation flanking this 63 bp fragment might have produced a reading frameshift (Figure 7 C). Therefore, it is possible that the xylG sequence has been positively selected, since its product possesses some advantageous catalytic properties.

Conclusions

In this work, we report the successful cloning, expression, purification of 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NahI) from P. putida G7. The enzyme was overexpressed in E. coli Arctic Express (DE3) at 12 ºC as an N-terminal hexa-histidine-tagged fusion protein, which was purified by affinity and gel filtration chromatography. His-tag removal with recombinant TEV protease was successfully employed and an almost native enzyme (GH-NahI) was obtained. The recombinant enzyme was structurally and kinetically characterized, and displays results consistent with the native enzyme.

The GH-NahI secondary structure content, as assessed by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, was similar to 2-AMS dehydrogenase from P. fluorescens (PDB ID 4I1W), another ALDH which shares 61% sequence identity to the recombinant enzyme. Despite the fact that NAD+ binding to GH-NahI did not cause significant conformational changes in the secondary structure of the enzyme, it seems to increase the stability of the complex probably by maintaining a few β-strands in the NAD+ binding domain during thermal denaturation. In addition, GH-NahI followed a two-step denaturation process. The GH-NahI/NAD+ complex had a higher second transition temperature, which reinforces the idea that the co-factor binding domain is less susceptible to thermal denaturation.

Even though SEC and DLS results suggest that GH-NahI might assemble as a trimer, the low-resolution NahI structure in solution confirms that this enzyme has a tetrameric arrangement similar to the 4I1W tetramer (i.e., 2-AMS dehydrogenase). The putative NahI tetramer is formed by two dimers of dimers that are oriented anti-parallel to each other to form a compact structure. The two dimers are easily identified and have the same structure topology as the ALDHs members that have been previously characterized experimentally.

The kinetic assay confirmed the preference of NahI for 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde, with a kcat/Km value similar to that of another dehydrogenase (XylG) from the same subfamily. Surprisingly, NahI showed no activity with salicylaldehyde, in contrast to XylG, which has activity with different aromatic substrates. The reason for this difference might be associated with a specific 21-amino acid fragment, which is remarkably different for the two enzymes and located near the predicted catalytic site. Comparison of nahI and xylG nucleotide sequences revealed that an insertion and a deletion mutation might have produced a reading frameshift, leading to a dramatic change in the catalytic properties of a 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase.

Highlights.

Active NahI was produced and purified in large quantities

The enzyme is a tetramer is solution, as observed by SAXS data

NAD+ binds to the enzyme and stabilizes its quaternary structure

NahI has no activity with salicylaldehyde, the substrate for NahF, an earlier enzyme

A specific 21-amino acid fragment around the catalytic site entrance might discriminate against salicylaldehyde

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Dr Masataka Tsuda and Dr Masahiro Sota for kindly providing us with the P. putida G7 strain and the Laboratório Nacional de Luz Síncrotron (CNPEM, Campinas, Brazil) for provision of synchrotron-radiation facilities (SAXS-1 beam line). This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; Project 482173/2010-6), Fundação de Desenvolvimento à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG; Projects EDT-0185-0.00-07, Rede-170/08 and RDP-00174-10), VALE S.A. (RDP-00174-10), the National Institutes of Health Grant GM-41239 (CPW), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1334, CPW). SSA, CMLN and RA are recipients of scholarships and research fellowship from CNPq.

References

- 1.Peng RH, et al. Microbial biodegradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32(6):927–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeed M, et al. Depurinating naphthalene-DNA adducts in mouse skin related to cancer initiation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(7):1075–81. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haritash AK, Kaushik CP. Biodegradation aspects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): a review. J Hazard Mater. 2009;169(1-3):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EPA Toxicological review of naphthalene. 2004.

- 5.Singh S, et al. Bioremediation: environmental clean-up through pathway engineering. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2008;19:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland TD, et al. Enzymatic bioremediation: from enzyme discovery to applications. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31(11):817–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alcalde M, et al. Environmental biocatalysis: from remediation with enzymes to novel green processes. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24(6):281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao B, Nagarajan K, Loh KC. Biodegradation of aromatic compounds: current status and opportunities for biomolecular approaches. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;85(2):207–28. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossello-Mora RA, Lalucat J, Garcia-Valdes E. Comparative biochemical and genetic analysis of naphthalene degradation among Pseudomonas stutzeri strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60(3):966–72. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.966-972.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen KM, Gunsalus IC. Plasmid gene organization: naphthalene/salicylate oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(3):874–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies JI, Evans WC. Oxidative metabolism of naphthalene by soil pseudomonads. The ring-fission mechanism. Biochem J. 1964;91(2):251–61. doi: 10.1042/bj0910251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen KM, Gunsalus IC. Regulation of naphthalene catabolic genes of plasmid NAH7. J Bacteriol. 1985;162(3):1008–13. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1008-1013.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch R, Garcia-Valdes E, Moore ER. Complete nucleotide sequence and evolutionary significance of a chromosomally encoded naphthalene-degradation lower pathway from Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. Gene. 2000;245(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D348–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sala-Trepat JM, Evans WC. The meta cleavage of catechol by Azotobacter species. 4-Oxalocrotonate pathway. Eur J Biochem. 1971;20(3):400–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala-Trepat JM, Murray K, Williams PA. The Metabolic Divergence in the meta Cleavage of Catechols by Pseudomonas putida NCIB 10015 - Physiological Significance and Evolutionary Implications. Eur J Biochem. 1972;28:347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue J, et al. Overlapping substrate specificities of benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (the xylC gene product) and 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (the xylG gene product) encoded by TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(5):1196–201. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1196-1201.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin M, Napoli JL. cDNA cloning and expression of a human aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) active with 9-cis-retinal and identification of a rat ortholog, ALDH12. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(51):40106–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang MF, Han CL, Yin SJ. Substrate specificity of human and yeast aldehyde dehydrogenases. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;178(1-3):36–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carneiro FR, et al. Spectroscopic characterization of the tumor antigen NY-REN-21 and identification of heterodimer formation with SCAND1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343(1):260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasteiger E, et al. In: Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server, in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Walker JM, editor. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasteiger E, et al. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3784–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohm G, Muhr R, Jaenicke R. Quantitative analysis of protein far UV circular dichroism spectra by neural networks. Protein Eng. 1992;5(3):191–5. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frishman D, Argos P. Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins. 1995;23(4):566–79. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerdan P, et al. Substrate specificity of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase encoded by TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida and its relationship to cell growth. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(19):6074–81. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6074-6081.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi T, et al. Overexpression of Pseudomonas putida catechol 2,3-dioxygenase with high specific activity by genetically engineered Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 1995;117(3):614–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammersley AP, et al. Two-dimensional detector software: From real detector to idealised image or two-theta scan. High Pressure Research. 1996;14(4-6):235–248. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mylonas E, Svergun DI. Accuracy of molecular mass determination of proteins in solution by small-angle X-ray scattering. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:S245–S249. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orthaber D, Bergmann A, Glatter O. SAXS experiments on absolute scale with Kratky systems using water as a secondary standard. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2000;33:218–225. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petoukhov MV, et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2012;45:342–350. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porod G. General theory. In: Glatter O, Kratky O, editors. Small angle X-ray scattering. Academic Press; London: 1982. pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svergun DI. Determination of the Regularization Parameter in Indirect-Transform Methods Using Perceptual Criteria. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1992;25:495–503. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doniach S. Changes in biomolecular conformation seen by small angle X-ray scattering. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101(6):1763–1778. doi: 10.1021/cr990071k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Characterizing Flexible and Intrinsically Unstructured Biological Macromolecules by SAS Using the Porod-Debye Law. Biopolymers. 2011;95(8):559–571. doi: 10.1002/bip.21638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semisotnov GV, et al. Protein globularization during folding. A study by synchrotron small-angle X-ray scattering. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;262(4):559–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer H, et al. Determination of the molecular weight of proteins in solution from a single small-angle X-ray scattering measurement on a relative scale. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2010;43:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL - A program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. Pt 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nature Protocols. 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franke D, Svergun DI. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2009;42:342–346. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volkov VV, Svergun DI. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2003;36:860–864. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozin MB, Svergun DI. Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2001;34:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayle RA, Milnerwhite EJ. Rasmol - Biomolecular Graphics for All. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1995;20(9):374–376. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agilent Technologies, I. ArcticExpress Competent Cells and ArcticExpress (DE3) Competent Cells - Instruction Manual. 230191-12, Editor 2010.

- 46.Coitinho JB, et al. Expression, purification and preliminary crystallographic studies of NahF, a salicylaldehyde dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida G7 involved in naphthalene degradation. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2012;68:93–7. doi: 10.1107/S174430911105038X. Pt 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo M, Singh RK, Tanner JJ. Structural Determinants of Oligomerization of Delta(1)-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylate Dehydrogenase: Identification of a Hexamerization Hot Spot. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2013;425(17):3106–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pemberton TA, et al. Structural Studies of Yeast Delta(1)-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate Dehydrogenase (ALDH4A1): Active Site Flexibility and Oligomeric State. Biochemistry. 2014;53(8):1350–1359. doi: 10.1021/bi500048b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He Z, Davis JK, Spain JC. Purification, characterization, and sequence analysis of 2-aminomuconic 6-semialdehyde dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes JS45. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(17):4591–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4591-4595.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harayama S, Rekik M. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the meta-cleavage pathway genes of TOL plasmid pWWO from Pseudomonas putida with other meta-cleavage genes suggests that both single and multiple nucleotide substitutions contribute to enzyme evolution. Molecular and General Genetics. 1993;239:81–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00281605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]