Abstract

Importance

In the United States, approximately one physician dies by suicide every day. Training physicians are at particularly high risk, with suicidal ideation increasing over four-fold during the first three months of internship year. Despite this dramatic increase, very few efforts have been made to prevent the escalation of suicidal thoughts among training physicians.

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of a Web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (wCBT) program delivered prior to the start of internship year in the prevention of suicidal ideation in medical interns.

Design, Setting and Participants

A randomized controlled trial conducted at two university hospitals with 199 interns from multiple specialties during academic years 2009-10 or 2011-12.

Interventions

Interns were randomly assigned to study groups (wCBT, n=100; attention-control group (ACG), n=99), and completed study activities lasting 30-minutes each week for four weeks prior to starting internship year. Subjects assigned to wCBT completed online-CBT modules and subjects assigned to ACG received emails with general information about depression, suicidal thinking and local mental health providers.

Main Outcome Measure

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was employed to assess suicidal ideation (i.e., “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself in some way”) prior to the start of intern year and at 3-month intervals throughout the year.

Results

62.2% (199/320) of individuals agreed to take part in the study. During at least one time point over the course of internship year 12% (12/100) of interns assigned to wCBT endorsed suicidal ideation, compared to 21%(21/99) of interns assigned to ACG. After adjusting for covariates identified a priori that have previously shown to increase the risk for suicidal ideation, interns assigned to wCBT were 60% less likely to endorse suicidal ideation during internship year (RR: 0.40, 95% CI 0.17-0.91; p=0.03), compared to those assigned to ACG.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a free, easily accessible, brief wCBT program can help reduce the development of suicidal ideation among medical interns. Prevention programs with these characteristics could be easily disseminated to medical training program across the country.

Keywords: Suicide, Medical, Education, Residency, Prevention, Web-Intervention

Introduction

Physicians are at high risk for suicide compared to the general population1. A meta-analysis of physician suicide revealed that male physicians are 1.41 times more likely and female physicians are 2.27 times more likely to die by suicide compared to their counterparts in the general population2. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year equating to approximately one doctor dying by suicide every day3.

Physicians in training are at high risk for suicide and suicidal ideation4. A review of prospective studies conducted during 1982-2002 identified high rates of suicidal ideation among doctors during their first postgraduate year, or internship year 5. These findings are consistent with several studies demonstrating elevated rates of suicidal ideation in medical trainees6-9. In a prospective cohort study of 740 interns from 13 institutions and multiple specialties across the United States, our research group found that suicidal ideation increased 370% over the first three months of internship year10. These findings were replicated in subsequent cohorts of interns11. Suicidal ideation in this study was defined as endorsement of item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire (i.e., ‘Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself in some way” over the past 2 weeks).These findings are concerning given that a positive response to this item increases the cumulative risk of a suicide attempt or completion over the next year by 10 and 100 fold, respectively12.

Despite the dramatic increase in suicidal ideation and other mental health problems among interns9,10-13, very few seek mental health treatment. Lack of time, preference to manage problems on their own, lack of convenient access to care and concerns about confidentiality have been identified as significant barriers to mental health treatment among training physicians5, 14-16. To reduce rates of suicidal ideation among training physicians, interventions that overcome these obstacles are necessary.

One promising approach to surmount these obstacles is the use of web-based tools. Specifically, web-based tools have important benefits over in-person treatment that correspond to the identified barriers to mental health care for physicians including: 1) enhanced confidentiality; 2) low cost; 3) easy accessibility; 4) flexibility in timing of access; and 5) self-management tools5, 14-16. To date, five randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a reduction in suicidal thoughts among adult individuals in the general population and primary care settings using web-based cognitive behavioral therapy programs17. Recent work has also demonstrated the efficacy of web-based preventative interventions for populations at high risk for mental health problems 18,19-20, but this preventative approach has not yet been tested in training physicians.

This study aims to determine the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a Web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (wCBT) program for the reduction of suicidal thoughts among medical interns.

Methods

Participants

352 interns entering traditional and primary care internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, emergency medicine, combined medicine and pediatrics and psychiatry residency programs at two university hospitals in the United States (Yale University and University of Southern California) during the 2009-10 and 2011-12 academic years were sent an email three months prior to commencing internship inviting them to participate in the study. Email invitations were returned as undeliverable for 9% (32/352) of potential subjects and 62.2% (199/320) of the remaining invited subjects agreed to participate in the study.

Participants were eligible for the study if they were beginning internship in July 2009 or July 2011 at one of two participating university hospitals. Data were collected through a secure online website designed to maintain confidentiality, with subjects identified only by a non-decodable identification number. All subjects were given information about symptoms of depression and encouraged to seek treatment locally if necessary. Subjects received $100 ($60 prior to the start of intern year and $40 during intern year) in online gift certificates for study participation. A waiver of written or oral consent and study approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board at both participating universities.

Assessments

Initial Assessment

Subjects completed a secure web-based baseline survey 3 months prior to commencing internship year including: 1) Demographic characteristics (gender, age, race/ethnicity); 2) Medical specialty; 3) Current depressive symptoms measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)21; 4) Neuroticism22; and 5) Early Family Environment 23.

Outcome Assessment

Suicidal ideation was assessed 3 months prior to the start of intern year and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of intern year. Suicidal ideation was measured using item 9 of the PHQ-921. Endorsement of suicidal ideation was positive if participants reported having “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself” for “several days”, “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” over the past two weeks (i.e., a score of 1 or greater on the PHQ-9).

Procedure

Two months prior to starting internship year, 199 eligible participants were randomly assigned to wCBT or the attention-control group (ACG). Participant email addresses were randomly assigned to conditions using complete randomization with equal allocation24 by a person independent of the research. Randomization successfully balanced key variables between conditions (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Randomized to Web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (wCBT) vs. Attention-Control.

| Baseline Characteristics |

wCBT | Attention- Control |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Subject, No. | 100 | 99 | |

| Age, mean (SD),y | 24.9 (8.7) | 25.4 (7.4) | 0.21 |

| Female, No. (%) | 51(51) | 48 (48.4) | 0.18 |

| Marital Status, Single, No (%) |

75 (75.0) | 60 (60.6) | 0.12 |

| White, No. (%) | 48 (48.0) | 50 (50.5) | 0.36 |

| Asian, No. (%) | 28 (28.0) | 30 (30.3) | 0.68 |

| Other Ethnicity, No. (%) |

24 (24.0) | 20 (20) | |

| Specialty No. (%) | |||

| Internal Medicine | 43 (43.0) | 46 (46.5) | 0.47 |

| Surgery | 9 (9.0) | 10 (10.1) | 0.89 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 3 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.27 |

| Pediatrics | 7 (7.0) | 6(6.1) | 0.58 |

| Psychiatry | 10 (10.0) | 6(6.1) | 0.74 |

| Neurology | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.1) | 0.49 |

| Emergency Medicine | 5 (5.0) | 7 (7.1) | 0.77 |

| Combined Medicine and Pediatrics |

4 (4.0) | 4 (4.0) | 0.86 |

| Other | 15 (15.0) | 13 (13.1) | 0.45 |

| Yale University No. (%) | 52 (52.0) | 54 (54.5) | 0.67 |

|

2009 Academic Year, No.(%) |

55 (55) | 52 (52.5) | 0.42 |

|

Pre-Internship Clinical

Characteristics |

|||

| Current Suicidal Ideation, No. (%) |

3 (3.0) | 3 (3.5) | 0.60 |

| Pre-Internship PHQ-9 ≥10, No. (%) |

5 (5) | 3 (3) | 0.54 |

|

Predictors of Suicidal

Ideation |

|||

| Pre-internship PHQ-9 Mean, (SD) |

2.78 (4.05) | 2.68 (2.94) | 0.85 |

| Neuroticism, mean (SD) |

27.82 (10.03) | 27.28 (9.56) | 0.69 |

| Early Family Environment, mean (SD) |

39.29 (10.13) | 38.68 (10.70) | 0.67 |

| History of Depression, No. (%) |

48 (48.0) | 47 (47.5) | 0.70 |

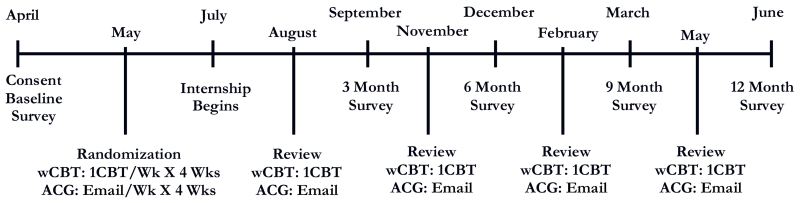

Following randomization, participants assigned to the ACG received an email once a week for 4 weeks containing information about mental illness including symptoms of depression, suicide and where to obtain local mental health treatment. Participants assigned to the intervention were directed via email each week for 4 weeks to the intervention web-site (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au) to complete a wCBT module. Participants gained access to the secure website via a user name provided within the email. Once participants accessed the web-site, they created a unique password known only by them allowing the content provided within the modules (e.g., individualized CBT exercises) to remain anonymous but also allowing web-site developers to track module completion for verification of participation based on assigned user name. At months 2, 5, 8 and 11 of internship year, the wCBT group was asked via e-mail to return to the web-site to review a module of their choice, while the ACG received an email containing information about the symptoms of depression, suicide and where to obtain local mental health treatment. Subsequent quarterly assessments for depression suicidal ideation were completed at least 6 weeks after any wCBT or ACG related activities or email contact (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Timeline.

wCBT: Web Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Group

ACG: Attention-Control Group

wCBT Intervention

The wCBT program, MoodGYM, was developed by staff at the National Institute for Mental Health Research at The Australian National University. The program consisted of 4 weekly web-based sessions lasting approximately 30 minutes each. The interactive program aims to facilitate an understanding of the interplay between thoughts, emotions and behaviors (Module 1) and teaches cognitive restructuring techniques that promote the ability to identify and challenge inaccurate, unrealistic, or overly negative thoughts (Module 2 and 3). The program also includes problem-solving strategies (Module 4).

Attention Control Condition

The control subjects received 4 weekly emails. All emails included information about the prevalence of depression and suicide among physicians, as well as described symptoms of depression and suicide and encouraged participants to seek treatment locally, if necessary. Contact information for local, confidential, and free mental health services was included in each email. Additional information about anxiety, substance abuse and other mood disorders were included in the second, third and fourth email, respectively.

Sample Size Calculations

Power analysis of suicidal ideation was conducted using Power and Precision statistical software. The target sample size (N=200) was designed to have 90% power to detect a difference between groups of a 50% reduction in cases of suicidal ideation, at alpha =0.05.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using intent-to-treat principles including last observation carried forward. Analyses were performed using a Generalized Estimating Equation to account for the correlated repeated measures within subjects. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). We assessed the adequacy of randomization by comparing the wCBT and ACG on demographic and baseline clinical characteristics as well as psychological factors previously shown to predict suicidal ideation in medical interns10,25 using chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests for continuous variables.

The point prevalence of suicidal ideation during internship year was determined through analysis of item 9 of the PHQ-9 at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month assessments. Endorsement of suicidal ideation was positive if participants reported having “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself” for “several days”, “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” over the past two weeks (i.e., a score of 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 during at least one follow-up assessment). Treatment assignment, institution, class year and their interactions as well as variables identified a priori that has shown to increase the risk of suicidal ideation (i.e., gender, history of depression, pre-internship PHQ-9 scores, neuroticism, early family environment)10,25 were entered into a stepwise logistic regression model to identify significant predictors while accounting for collinearity among variables. Intervention assignment was included in the model to determine the impact of the intervention on suicidal ideation during internship year. Covariates included in the final model were identified a priori based on prior work. No post hoc testing of covariates were performed. The dependent variable was not used in the construction of the independent variable.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

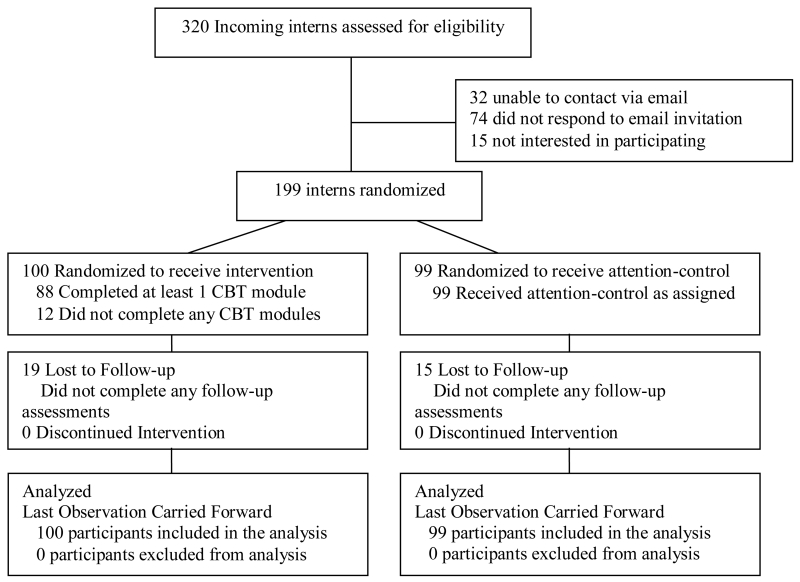

Participants’ mean (SD) age was 25.2 (8.1) years. Overall, 49.3% of participants were female and 43.0% were self-identified members of an ethnic/racial minority group. Participants did not differ significantly by study intervention condition on demographic, clinical characteristics (e.g., suicidal ideation, use of psychotropic medication) or previously identified baseline variables shown to predict suicidal ideation in medical interns10,25 (Table 1). 83% (165/200) of all participants completed at least one within-in internship follow-up assessment. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), specialty, university, clinical characteristics (history of depression, pre-internship current depressive symptoms) or other previously identified variables shown to predict depression or suicidal ideation in medical interns10,25 between retained participants and those who did not complete within internship follow-up assessments. Over the course of internship year, there were no significant differences between participants assigned to wCBT or the ACG in seeking mental health treatment (7% vs. 8%) or starting a psychotropic medication (4% vs. 7%), respectively.

Acceptability

88%(88/100) of participants assigned to the intervention completed at least one web-CBT module. 78%(78/100), 65%(65/100) and 51%(51/100) of participants completed 2, 3 or all 4 CBT modules, respectively. Completers of the 4 CBT modules did not differ from participants who completed less than 4 modules in age, gender, specialty, race/ethnicity, university or previous variables shown to predict depression and suicidal ideation10,25. Over the course of internship year, 82% (82/100) of participants reviewed at least one wCBT module.

Efficacy

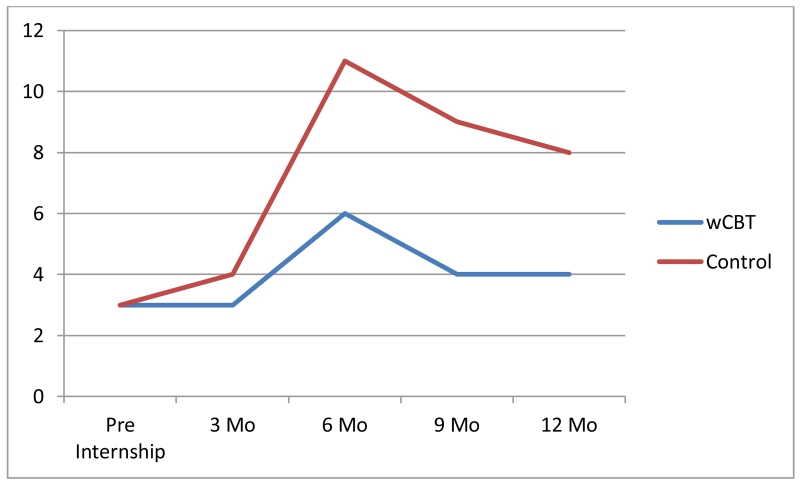

Over the course of internship year, 12% (12/100) of interns in the wCBT group endorsed suicidal ideation during at least one follow-up assessment, compared to 21% (21/99) of interns in the ACG. Treatment assignment, institution, class year and their interactions did not associate with endorsement of suicidal ideation during internship year. After accounting for a priori baseline factors associated with the development of suicidal ideation and depression (gender, pre-internship PHQ-9 scores, history of depression, neuroticism and early family environment), interns assigned to the wCBT group were 60% less likely to endorse suicidal ideation during internship year, compared to those assigned to the ACG (RR: 0.40, 95% CI 0.17-0.91; p= 0.03). The effect size of wCBT was 1.97. The number needed to treat is 11 (Figure 3). Analyses stratified by gender did not reveal significant gender effects.

Figure 3. Number of Interns Endorsing Suicidal Ideation During Internship Year.

Comment

Summary

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of an intervention that targets the alarmingly high rate of suicidal ideation among medical interns. First, this study demonstrates the acceptability of a web-based preventative intervention for medical trainees. While only 10-20% of interns utilize traditional mental health resources 5,14, 62% agreed to participate in the current intervention, with 88% completing at least one wCBT module and 82% returning for at least one wCBT review during internship year. It is possible that prevention programs for healthy interns are less stigmatizing than treatment programs for mental health problems26 and, as a result, achieve higher participation rates. This acceptability should encourage the development and implementation of other preventative interventions for physicians that accommodate the desire for confidentiality, time flexibility and autonomy present in web-based programs.

Further, this two-site randomized prevention trial demonstrates that a web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy program significantly reduces the development of suicidal ideation during internship year. Interns assigned to the wCBT group were 60% less likely to endorse suicidal ideation during internship year, compared to those assigned to the ACG. The suicide risk reduction in our study translates into a number needed to treat of 11; that is, for every 11 interns taking part in the intervention, we would expect to prevent one intern from developing suicidal ideation. Importantly, the effect of the intervention was sustained over an entire year. Equipping medical interns early on in their careers with evidence-based strategies to better manage their mental health can potentially have long lasting effects on their mental health and the health of their patients. Our findings are consistent with previous research examining the effect of web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on the reduction of suicidal ideation17. Studies employing web-based CBT have found statistically significant reductions in suicidal ideation28-32. Our findings differ from prior studies examining the effect of a web-based depression intervention on suicidal ideation in that prior studies include populations with current suicidal ideation. Our findings extend the current literature and demonstrate that web-based CBT appears to prevent the onset of suicidal ideation over the course of an entire year, as opposed to decreasing suicidal ideation after it occurs. These findings are exciting given the high likelihood that interns will experience suicidal ideation and low likelihood that they will seek mental health treatment.

There are a number of aspects of this prevention program that greatly increase the likelihood of successful dissemination and implementation. First, the program is free to the public and available to anyone with access to the internet. Second, all ‘interactions’ with the participants (e.g., invitation to take part in the program, reminders about completing the program) occurred via an automated email system and required very little personnel time and attention. Third, the program allows trainees to complete much of the program before internship year, when their time is more abundant. Lastly, interns are willing to take part in this sort of intervention. Pragmatic programs with successful participant adherence are likely to be disseminated and easily implemented in real-world settings.

Limitations

Interpretation of these data are limited by several considerations. First, we assessed suicidal ideation through a self-report inventory rather than a diagnostic interview. We chose this method, as opposed to an in person assessment, based on previous data demonstrating that anonymity is necessary to accurately ascertain mental health problems among medical students33. Nonetheless, it would be important to validate these finding using structured clinical interviews. Second, this study assessed suicidal ideation and not suicide or suicidal behaviors. Therefore it is unknown if the intervention has any impact on physician suicide. The ability to detect the interventions effect on suicide would require a much larger sample size with a longer follow-up period. Third, the actual numbers of interns endorsing suicidal ideation during at least one follow-up assessment over the course of internship year in the wCBT group and ACG is small, 12% vs. 21%, respectively. Thus, replication of these findings is important. Lastly, this study was conducted at two universities and findings may not generalize to other academic institutions or community hospitals.

Future Directions

Approximately half of interns assigned to wCBT completed all 4 of the assigned CBT modules. Future studies aimed at better understanding which modules are most effective at reducing suicidal ideation would be of great benefit. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanism by which wCBT reduces suicidal ideation among interns and to determine if the positive benefits of wCBT on suicidal ideation are sustained over time.

Conclusions

Taken together, our study supports the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of a web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy program for the prevention of suicidal ideation among medical interns during internship year. With approximately 24,000 medical trainees beginning internship each year34, dissemination of a pragmatic, no cost, feasible and efficacious prevention program could have substantial public health benefits1,27,35. This work further supports web-based interventions as promising tools to enhance physician mental health and decrease their high risk for suicide.

Figure 2. Study Flow of Participants from Recruitment to Data Analysis.

Acknowledgement

Funding/Support:

The project described was supported by Grant Number K12HD055885 from the National Institute of Child Health And Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) as well as Grant Number 1K23DA039318-01 from the National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Federal support was also provided by Grant Number R01 MH101459 from the National Institute of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Foundation funding was provided by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) Grant Number 2YIG-00054-1207.The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NICHD, ORWH, NIDA, NIMH, and AFSP.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The NIH, NICHD, ORWH, NIDA, NIMH and AFSP had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions:

We would like to acknowledge and thank the interns taking part in this study. Without their participation this study would not be possible. We would also like to thank and acknowledge Helen Christensen, PhD., Professor at the Black Dog Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Dr. Christensen generously provided access to MoodGym to allow the conduct of this study. Without her support this study would not have been possible. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Kylie Bennett, e hub manager, and Mr. Anthony Bennett, software engineer, at the Centre for Mental Health Research for creating the software to deploy this version of MoodGYM and tracking user completion. Dr. Christensen, Ms. Bennett and Mr. Bennett provided no financial support and were not involved in the design, analysis or interpretation of the study results.

Constance Guille and Zhuo Zhao had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Trial Registration:

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12610000628044 https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=335769

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors of this paper do not have any commercial or other associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: A consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161–3166. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: A quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2295–2302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Foundation of Suicide Prevention [Accessed February 1, 2015];Facts about physician depression and suicide. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Web site. 2015 http://www.afsp.org/preventing-suicide/our-education-and-prevention-programs/programs-for-professionals/physician-and-medical-student-depression-and-suicide/facts-about-physician-depression-and-suicide. Updated.

- 4.Goldman ML, Shah RN, Bernstein CA. Depression and suicide among physician trainees: Recommendations for a national response. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyssen R, Rovik JO, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O. Help-seeking for mental health problems among young physicians: Is it the most ill that seeks help? - A longitudinal and nationwide study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(12):989–993. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0831-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA. Variation of mood and empathy during internship. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3143–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520–1525. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider SE, Phillips WM. Depression and anxiety in medical, surgical, and pediatric interns. Psychol Rep. 1993;72(3 Pt 2):1145–1146. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):557–565. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried EI, Nesse RM, Zivin K, Guille C, Sen S. Depression is more than the sum score of its parts: Individual DSM symptoms have different risk factors. Psychol Med. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyssen R, Vaglum P. Mental health problems among young doctors: An updated review of prospective studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):154–165. doi: 10.1080/10673220216218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, Epperson CN, Sen S. Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: A prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):210–214. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00086.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givens JL, Tjia J. Depressed medical students’ use of mental health services and barriers to use. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):918–921. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moutier C, Cornette M, Lehrmann J, et al. When residents need health care: Stigma of the patient role. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(6):431–441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.6.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen H, Batterham PJ, O’Dea B. E-health interventions for suicide prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(8):8193–8212. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110808193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beekman AT, Smit F, Stek ML, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Cuijpers PC. Preventing depression in high-risk groups. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(1):8–11. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328333e17f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Evaluating the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of web-based indicated prevention of major depression: Design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:25–244. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz RF, Cuijpers P, Smit F, Barrera AZ, Leykin Y. Prevention of major depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:181–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. primary care evaluation of mental disorders. patient health questionnaire. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: The revised NEO personality inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess. 1997;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor SE, Way BM, Welch WT, Hilmert CJ, Lehman BJ, Eisenberger NI. Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(7):671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalish LA, Begg CB. Treatment allocation methods in clinical trials: A review. Stat Med. 1985;4(2):129–144. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried EI, Nesse RM, Zivin K, Guille C, Sen S. Depression is more than the sum score of its parts: Individual DSM symptoms have different risk factors. Psychol Med. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwenk TL, Davis L, Wimsatt LA. Depression, stigma, and suicidal ideation in medical students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1181–1190. 10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jane-Llopis E, Hosman C, Jenkins R, Anderson P. Predictors of efficacy in depression prevention programmes. meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:384–397. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.5.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moritz S, Schilling L, Hauschildt M, Schroder J, Treszl A. A randomized controlled trial of internet-based therapy in depression. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(7-8):513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Spijker BA, van Straten A, Kerkhof AJ. Effectiveness of online self-help for suicidal thoughts: Results of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e90118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen H, Farrer L, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, Donker T. The effect of a web-based depression intervention on suicide ideation: Secondary outcome from a randomised controlled trial in a helpline. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002886. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts S, Newby JM, Mewton L, Andrews G. A clinical audit of changes in suicide ideas with internet treatment for depression. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001558. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001558. Print 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams AD, Andrews G. The effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for depression in primary care: A quality assurance study. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine RE, Breitkopf CR, Sierles FS, Camp G. Complications associated with surveying medical student depression: The importance of anonymity. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(1):12–18. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Resident Matching Program [Accessed April 9, 2015];Main residency match data. 2015 http://www.nrmp.org/match-data/main-residency-match-data/. Updated 2015.

- 35.Rose G. Preventive strategy and general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43(369):138–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]