Abstract

Herein we aimed to evaluate the utility of N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-2-18F-fluoro-N-(2-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide (18F-PBR06) for detecting alterations in translocator protein (TSPO) (18 kDa), a biomarker of microglial activation, in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

Wild-type (wt) and AD mice (i.e., APPL/S) underwent 18F-PBR06 PET imaging at predetermined time points between the ages of 5–6 and 15–16 mo. MR images were fused with PET/CT data to quantify 18F-PBR06 uptake in the hippocampus and cortex. Ex vivo autoradiography and TSPO/CD68 immunostaining were also performed using brain tissue from these mice.

Results

PET images showed significantly higher accumulation of 18F-PBR06 in the cortex and hippocampus of 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice than age-matched wts (cortex/muscle: 2.43 ± 0.19 vs. 1.55 ± 0.15, P < 0.005; hippocampus/muscle: 2.41 ± 0.13 vs. 1.55 ± 0.12, P < 0.005). And although no significant difference was found between wt and APPL/S mice aged 9–10 mo or less using PET (P = 0.64), we were able to visualize and quantify a significant difference in 18F-PBR06 uptake in these mice using autoradiography (cortex/striatum: 1.13 ± 0.04 vs. 0.96 ± 0.01, P < 0.05; hippocampus/striatum: 1.266 ± 0.003 vs. 1.096 ± 0.017, P < 0.001). PET results for 15- to 16-mo-old mice correlated well with autoradiography and immunostaining (i.e., increased 18F-PBR06 uptake in brain regions containing elevated CD68 and TSPO staining in APPL/S mice, compared with wts).

Conclusion

18F-PBR06 shows great potential as a tool for visualizing TSPO/microglia in the progression and treatment of AD.

Keywords: microglial activation, Alzheimer's disease, translocator protein 18 kDa, PET

The main pathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) include senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, which are composed of toxic β-amyloid peptides and hyperphsophorylated tau aggregates, respectively (1). Another key feature of AD is microglial activation—a complex cellular process responsible for the proinflammatory milieu known to promote neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration (2). Microglial activation is also involved in anti-inflammatory activity and can stimulate tissue repair (3). Much research is being conducted to better understand the role and various dynamic stages of microglial activation; however, many questions remain.

Imaging techniques such as MR imaging and PET provide a means to noninvasively visualize different structural, functional or molecular biomarkers in living intact subjects (4). Such tools could enhance our understanding of the in vivo role of microglial activation in AD and ultimately enable the longitudinal monitoring of disease progression and response to therapies. Structural and functional MR imaging have provided numerous, valuable insights concerning brain atrophy, alterations in perfusion, and various brain networks in AD (5–7). However, because of the limited sensitivity of these techniques for detecting specific molecular alterations in a highly quantitative manner, MR imaging has not historically been the imaging modality of choice for visualizing microglia in AD.

PET imaging, on the other hand, using small-molecule radioligands specific for the translocator protein (TSPO) (18 kDa), has been used extensively to detect microglial activation in both preclinical and clinical studies (8). The TSPO is mainly located on the outer mitochondrial membrane and is involved in steroid biosynthesis under normal physiologic conditions (9). Although there are only moderate levels of TSPO in the healthy brain, these levels are increased under neuroinflammatory/degenerative conditions (10,11). The predominant cell type expressing TSPO at regions of central nervous system pathology are activated microglia, therefore enabling TSPO PET radioligands to serve as a useful index of microglial activation and neuroinflammation (12). PET imaging with the TSPO radioligand N-sec-butyl-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-11C-methyl-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide (11C-PK11195) has been used as a noninvasive sensor of microglial activation in multiple conditions including AD (13). And although 11C-PK11195 has provided useful information, its poor brain permeability and high plasma protein binding have limited its sensitivity and overall usefulness (14). Several improved TSPO tracers have been developed over the past decade (15), including N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-2-18F-fluoro-N-(2-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide (18F-PBR06) (16). 18F-PBR06 has a high affinity and specificity for TSPO across multiple species and has been used in human studies for quantitation of brain TSPO (17). To date, no studies have been published reporting the use of 18F-PBR06 in AD patients or transgenic mouse models of AD.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the sensitivity and accuracy of 18F-PBR06 PET for detecting alterations in TSPO levels in an accelerated mouse model of AD—that is, Thy1-hAPPLond/Swe (APPL/S) (18)—at different stages of disease. We chose the cortex and hippocampus as areas of interest for these studies because they are the key brain structures containing AD pathology in this mouse model (18).

Materials and Methods

General

If not otherwise stated, chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. PET imaging of mice was performed using a micro-PET/CT scanner (Inveon; Siemens). PET images were reconstructed by performing 2 iterations of a 3-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximization algorithm (12 subsets) and then 18 iterations of the accelerated version of 3-dimensional maximum a posteriori, with a matrix size of 128 × 128 × 159. Attenuation correction was applied to a dataset from the CT images. PET images were coregistered with CT and MR images using Inveon Research Workplace image analysis software, version 4.0 (Siemens).

Study Design and Rationale

This study was designed to provide crucial information for planning future therapy-monitoring studies with 18F-PBR06 in APPL/S mice. Long-term, we plan to evaluate numerous TSPO radiotracers side by side in therapy-monitoring studies to determine which tracer can potentially serve as a clinical endpoint for novel AD therapeutics that alter microglial activation.

Toward this goal, we set out to evaluate whether 18F-PBR06 could detect differences between APPL/S and wild-type (wt) mice aged 9–10 and 15–16 mo, which would be the age of mice at the end of our planned therapy-monitoring studies. These studies will involve a 3-to 4-mo-long treatment of wt/APPL/S mice aged 5–6 mo (when mature amyloid plaques have formed in the cortex and are starting to form in the hippocampus (18)) and at 12–13 mo (relatively late stage of disease exhibiting extensive AD pathology). These time points are based on previous published and unpublished work demonstrating the efficacy of LM11A-31 (a novel AD therapeutic that attenuates neuronal degeneration and microglial activation) in APPL/S mice at these ages (19). We designed the current study with 2 separate cohorts to maximize the amount of PET, autoradiography, and histologic data we could acquire for our 2 primary ages of interest. The supplemental materials (available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org) provide details on the APPL/S mouse model of AD we chose for the current studies.

Small-Animal MR Imaging

Brain MR images were acquired to provide an anatomic reference frame for each mouse so that we could draw accurate regions of interest around the cortex and hippocampus during PET image analysis. Supplemental Figure 1 shows how all regions of interest were drawn. Mice were scanned with a dedicated small-animal 7-T Varian Magnex Scientific MR scanner with custom-designed pulse sequences and radiofrequency coils using standard methods. The supplemental materials provide details.

Small-Animal PET/CT

18F-PBR06 was synthesized via nucleophilic aliphatic substitution as previously described (16,20), with a non–decay-corrected radio-chemical yield of 2.17% ± 0.38% and a specific radioactivity of 131.91 ± 16.09 GBq/μmol at the end of bombardment (n = 8).

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane gas (2.0%–3.0% for induction and 1.5%–2.5% for maintenance). Dynamic scans for 15- to 16-mo-old wt and APPL/S mice (n = 4/group) were commenced just before intravenous administration of 18F-PBR06 (5.5–7.5 MBq) and acquired in list-mode format over 60 min. The resulting data were sorted into 0.5-mm sinogram bins and 19 time frames for image reconstruction (4 × 15, 4 × 60, and 11 × 300 s). Blocking studies involved pretreating 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice (n = 3) with PK11195 (1 mg/kg; Sigma Aldrich) 10 min before radioligand administration. Static PET scans (10 min) were acquired 40 min after intravenous administration of 18F-PBR06 (5.5–7.5 MBq). CT images were acquired just before each PET scan to provide an anatomic reference for PET data.

PET images were analyzed by drawing 3-dimensional regions around the whole brain, muscle, cortex, and hippocampus (Supplemental Fig. 1). The latter 2 regions were drawn between the bregma +11.94 and +10.02 and bregma −1.22 and −2.30 to ensure consistency between mice. Percentage of injected dose per gram (%ID/g) was calculated for each region of interest. Signal-to-background ratios were calculated by dividing the uptake in each brain region by uptake in a reference region (i.e., muscle or whole brain). Supplemental Figures 2–6 describe how and why reference regions were selected.

Ex Vivo Autoradiography

After final PET/CT scans, mice were perfused, brain tissue was embedded in optimal-cutting-temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek), and coronal sections (20 μm) were obtained for autoradiography. Autoradiography was conducted using previously described methods (21), and the anatomy of brain sections was confirmed by Nissl staining.

For quantitation of autoradiography, we analyzed 5 sections per mouse in the 9- to 10-mo age group (n = 3/genotype) and 5 sections per mouse in the 15- to 16-mo age group (n = 4/genotype). For each section, 1 region was drawn within the somatosensory cortex, striatum, hippocampus, and choroid plexus (between bregma +1.94 and −2.30, corresponding to brain regions used for PET image analysis), resulting in a mean signal intensity value for each brain region within each section. For each mouse, the mean signal intensities for the cortex, hippocampus, and choroid plexus were normalized to the mean signal intensity for the striatum. The striatum contains low TSPO in this mouse model and can therefore be used as an internal reference region to provide a signal-to-background ratio for each region of interest. Supplemental Figure 7 shows evidence of negligible TSPO staining in the striatum of 15- to 16-mo-old wt and APPL/S mice.

Plasma-Free Fraction (fP)

fP studies for 18F-PBR06 in 15- to 16-mo-old mice (n = 3 APPL/S; n = 4 wt) were performed at room temperature with ultrafiltration units, according to previously described methods (22).

CD68 and TSPO Staining

Frozen 50-μm coronal brain sections were collected using a Microm HM 450 sliding microtome (Thermo Scientific). Free-floating sections were incubated with either rat anti-CD68 (AbD Serotec; 1:1000) or rabbit anti-TSPO (Epitomics; 1:500). For visualization, sections were immersed in an avidin–biotin complex solution (Vector Laboratories), followed by 0.05% diaminobenzidine (Sigma Aldrich) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.03% H2O2. CD68 and TSPO staining quantitation methods are given in the supplemental materials.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses of data were performed using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test within GraphPad Prism (version 6.0 d; GraphPad Software Inc.). Significance was set at a P value less than 0.05.

Results

Small-Animal PET

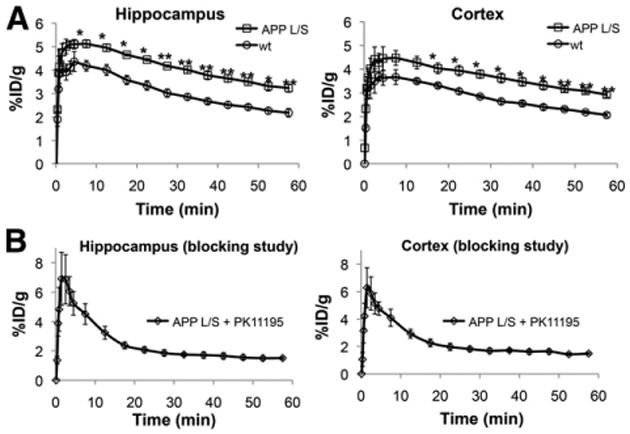

Dynamic 18F-PBR06 imaging studies were performed with 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice, known to exhibit extensive microglial activation. These studies were conducted to gain an understanding of the uptake, kinetics, and suitability of this tracer for detecting neuroinflammation in this mouse model of AD. Time–activity curves generated from these studies (Fig. 1A) showed significantly higher 18F-PBR06 accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus of APPL/S mice than wts (cortex: 3.32 ± 0.16 %ID/g vs. 2.42 ± 0.10 %ID/g, P < 0.005; hippocampus: 3.65 ± 0.17 %ID/g vs. 2.54 ± 0.12 %ID/g, P < 0.005, at 40–50 min after injection, n = 4/group). Pretreating these same APPL/S mice with a known TSPO ligand, PK11195 (1 mg/kg), before tracer administration, dramatically reduced 18F-PBR06 PET signal in the cortex and hippocampus (52% reduction, compared with baseline data summed between 40 and 50 min, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Time–activity curves showing 18F-PBR06 accumulation in 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S and wt mice (A) and APPL/S mice after pretreatment with PK11195 (B). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.005.

The sensitivity of 18F-PBR06 for detecting TSPO in APPL/S mice was investigated by conducting PET studies in mice of different ages, exhibiting varying levels of microglial activation. Quantitation of PET images from these studies showed no significant difference in whole-brain signal between APPL/S and wt mice 5–6 and 9–10 mo old (Supplemental Fig. 2). However, there was a significant difference between APPL/S and wt mice aged 14–15 mo or older (14–15 mo: 1.51 ± 0.08 %ID/g vs. 1.28 ± 0.05 %ID/g, P < 0.05, n = 12/group; 15–16 mo: 1.41 ± 0.06 %ID/g vs. 1.06 ± 0.10 %ID/g, P ± 0.05, n = 8 APPL/S, n = 7 wt).

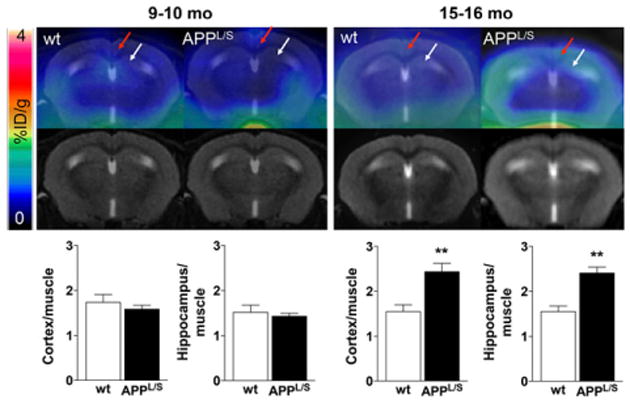

Next we quantified tracer accumulation in our predefined regions of interest (cortex and hippocampus) and found no significant difference in PET signal for 9- to 10-mo-old APPL/S and wt mice (P = 0.64) (Fig. 2). There was however, significantly higher 18F-PBR06 accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus of 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice, demonstrated by %ID/g values (Supplemental Fig. 3) and signal-to-background ratios using either muscle (Fig. 2) or whole brain as a reference region (Supplemental Fig. 3) (cortex/muscle: 2.43 ± 0.19 vs. 1.55 ± 0.15, P < 0.005; hippocampus/muscle: 2.41 ± 0.13 vs.1.55 ± 0.12, P = 0.005, n = 8 APPL/S, n = 7 wt). Table 1 shows there was no significant difference in fP for APPL/S versus wt mice aged 15–16 mo (P = 0.84).

Figure 2.

PET/MR images and graphs depicting 18F-PBR06 accumulation in APPL/S vs. wt mice 9–10 mo (n = 7/group) and 15–16 mo of age (n = 8 APPL/S, n = 7 wt). Red and white arrows point to cortex and hippocampus, respectively. **P < 0.005.

Table 1. fP of 18F-PBR06 in 15- to 16-Month-Old Mice.

| Genotype | fP |

|---|---|

| wt | 18.5 ± 0.5 (n ± 4) |

| APPL/S | 18.7 ± 0.6 (n ± 3) |

Errors are SEM.

Ex Vivo Autoradiography

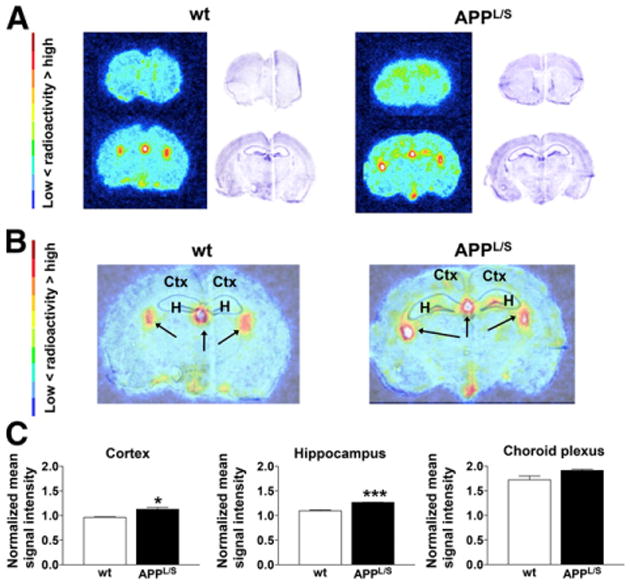

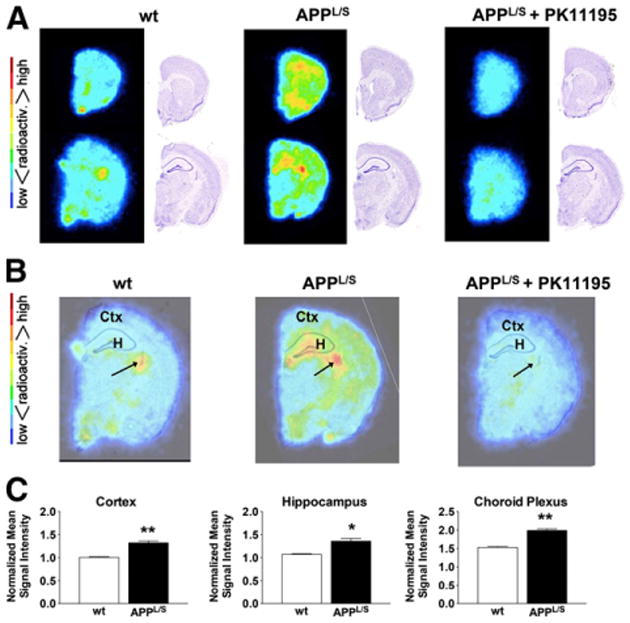

To further investigate the uptake of 18F-PBR06 in specific brain regions at higher resolution, we performed autoradiography immediately after PET imaging. Unlike PET results, quantitation of autoradiography images from 9- to 10-mo-old mice revealed significant elevation in 18F-PBR06 uptake in the cortex and hippocampus of APPL/S mice (Fig. 3) (cortex/striatum: 1.13 ± 0.04 vs. 0.96 ± 0.01, P < 0.05; hippocampus/striatum: 1.266 ± 0.003 vs. 1.096 ± 0.017, P < 0.001, n = 3/group). For 15- to 16-mo-old mice, however, autoradiography results (Fig. 4) were comparable to PET findings (Fig. 2), that is, there was significantly higher 18F-PBR06 accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus of 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S than wts (cortex/striatum: 1.32 ± 0.04 vs. 1.01 ± 0.02, P < 0.005; hippocampus/striatum: 1.36 ± 0.06 vs. 1.07 ± 0.01, P < 0.005, n = 4/group). Apart from the expected uptake in the hippocampus/cortex, we also observed intense focal uptake in 1–3 small regions in almost all autoradiography images. Nissl staining of the same sections revealed that this focal uptake aligned with the choroid plexus. Visually, the uptake in the choroid plexus appeared more intense in APPL/S mice than in wts (from both age groups), and thus we decided to quantify this uptake. We found significantly higher 18F-PBR06 choroid plexus uptake in 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice than wt littermates (Figs. 4B and 4C) (choroid plexus/striatum: 1.99 ± 0.05 vs. 1.53 ± 0.02, P < 0.005, n = 4/group) and a trend toward increased uptake in the choroid plexus of 9- to 10-mo-old mice (Figs. 3B and 3C). Autoradiography results from the PK11195 blocking study (Figs. 4A and 4B) show a marked reduction of 18F-PBR06 uptake in all brain regions of the 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice.

Figure 3.

Ex vivo autoradiography of 9- to 10-mo-old mice. (A) Representative images and Nissl staining of same brain sections. (B) Overlay of autoradiography brain images with Nissl staining. (C) Mean signal intensity for specific brain regions normalized to striatum for wt and APPL/S mice (n = 3/group). Arrows indicate choroid plexus. *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.0005. Ctx = cortex; H = hippocampus.

Figure 4.

Ex vivo autoradiography of 15- to 16-mo-old mice. (A) Representative images and Nissl staining of same brain sections. (B) Overlay of autoradiography brain images with Nissl staining. (C) Mean signal intensity for specific brain regions normalized to striatum for wt and APPL/S mice (n = 4/group). Arrows indicate choroid plexus. *P = 0.05. **P value < 0.005. Ctx = cortex; H = hippocampus.

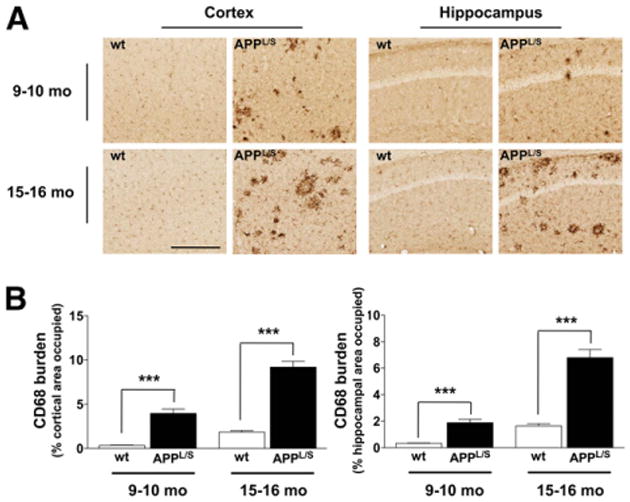

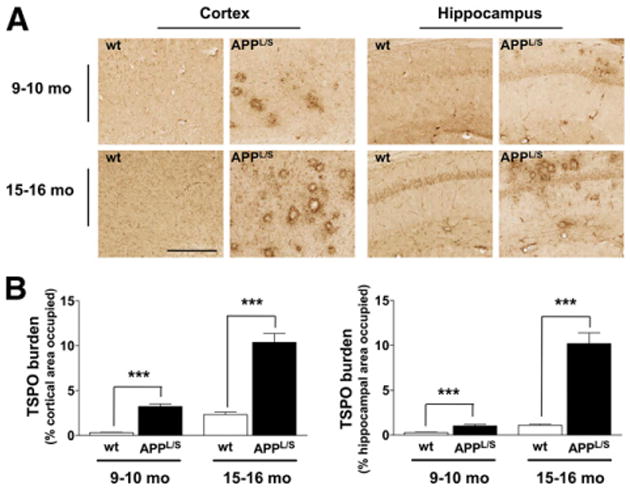

Immunohistochemistry

To assess whether 18F-PBR06 PET signal correlated with levels of activated microglia and TSPO, we harvested brain tissue from 9- to 10-mo and 15- to 16-mo-old mice and performed immunohistochemistry (Figs. 5 and 6). Quantitation of the percentage of cortical to hippocampal area occupied by CD68 staining showed increased levels of activated microglia in APPL/S, compared with wts, for both 9- to 10-mo-old (P < 0.0005, n = 8/group) and 15- to 16-mo-old mice (P < 0.0005, n = 8/group). Likewise, the percentage of cortical to hippocampal area occupied by TSPO staining was found to be significantly greater in APPL/S mice than wts for 9- to 10-mo-old (P < 0.0005, n = 8/group) and 15- to 16-mo-old mice (P < 0.0005, n = 8/group).

Figure 5.

CD68 staining. (A) Representative images from 9- to 10-mo- and 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S and wt mice (n = 8/genotype). Scale bar = 250 μm, magnification, ×20. (B) Quantitation of percentage of cortical to hippocampal area occupied by CD68 staining. ***P < 0.0005.

Figure 6.

TSPO staining. (A) Representative images from 9- to 10-mo- and 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S and wt mice (n = 8/genotype). Scale bar = 250 μm, magnification, ×20. (B) Quantitation of percentage of cortical to hippocampal area occupied by TSPO staining. ***P < 0.0005.

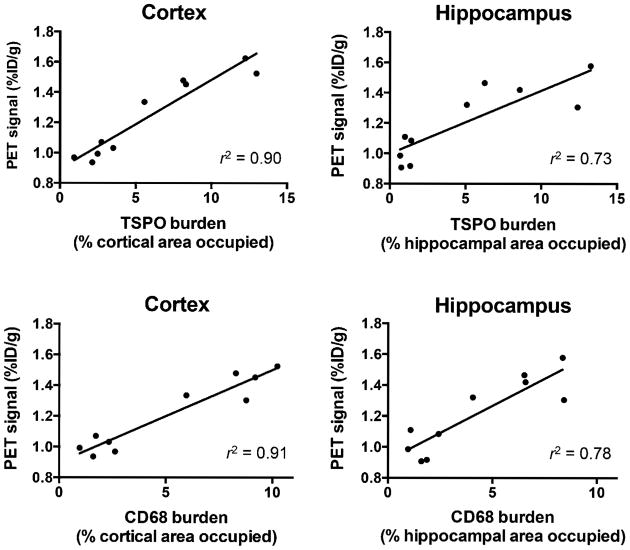

Figure 7 and Supplemental Figure 8 show that autoradiography and PET results, for 15- to 16-mo-old mice, correlated well with each other (r2 = 0.76) and also with immunostaining (i.e., increased 18F-PBR06 uptake in brain regions containing elevated CD68 and TSPO staining in APPL/S, compared with wts). Specifically, we observed a strong/moderate correlation between PET signal and TSPO levels in the cortex (r2 = 0.90) and hippocampus (r2 = 0.73) and also between PET signal and CD68 levels in the cortex (r2 = 0.91) and hippocampus (r2 = 0.78). Additionally, we found a strong correlation between CD68 and TSPO staining in both the cortex (r2 = 0.87) and the hippocampus (r2 = 0.94) (Supplemental Fig. 9).

Figure 7.

Correlation between TSPO/CD68 burden and PET signal for 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S and wt mice (n = 5/group).

Discussion

Herein, we assessed the sensitivity and accuracy of 18F-PBR06 PET for detecting alterations in TSPO levels and microglial activation in a well-characterized, accelerated transgenic mouse model of AD (18). Our ultimate goal was to determine the potential of this tracer as a tool for investigating the in vivo role of microglia in AD and as a surrogate marker for treatment response in future therapy-monitoring studies.

We found that 18F-PBR06 PET could detect elevated TSPO and activated microglia in the cortex and hippocampus of 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice, as verified by ex vivo autoradiography and the strong correlation with TSPO/CD68 immunohistochemistry. The specificity of 18F-PBR06 for TSPO in the APPL/S mouse brain was confirmed by blocking studies with a known TSPO ligand PK11195. Additionally we verified that the increased 18F-PBR06 uptake in 15- to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice was not due to differences in fP of the tracer between wt and diseased mice (Table 1). Although we showed elevated CD68/TSPO staining in 9- to 10-mo-old APPL/S mice compared with wts, we were unable to detect a difference in brain PET signal between APPL/S and wt mice of this age. This inability to detect a difference in 18F-PBR06 brain uptake in these mice may have been due to the limited spatial resolution of small-animal PET and issues associated with the partial-volume effect when quantifying radiotracer uptake in small regions (e.g., mouse brain structures) (23). It was not until we used ex vivo autoradiography, a technique with higher spatial resolution than PET, that we could visualize and quantify a significant difference in 18F-PBR06 cortical/hippocampal uptake in these younger APPL/S mice, compared with age-matched wts. Because of this finding, we plan to perform ex vivo autoradiography for all future mouse studies with 18F-PBR06 to complement our PET data. Mouse PET and autoradiography data will serve as a proof of principle so we can move into human AD patients as a next step (where resolution will be a lesser issue). Imaging rat models of AD could reduce partial-volume–related issues; however, because these models have not been as useful for AD therapeutic development they are not suitable for our future planned therapy-monitoring studies.

An unexpected finding from our autoradiography studies was that we could clearly visualize accumulation of 18F-PBR06 in the choroid plexus and that this uptake was significantly higher in 15-to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice than age-matched littermates. The choroid plexus contains moderate levels of TSPO in healthy human, monkey, and rodent brains (24); however, not much is known about TSPO levels in this structure in disease. Because the choroid plexus is involved in filtering and producing cerebrospinal fluid, and its dysfunction has been linked to amyloid build-up in AD (25), our observation could be an indication of a molecular dysfunction/alteration in the choroid plexus of this mouse model of AD. Although there have been reports detailing the anatomic and functional changes of the choroid plexus in clinical AD cases (26), there have been no such reports detailing TSPO alterations in this structure in AD. Recently however, there was a study showing increased choroid plexus uptake of another TSPO PET radioligand, N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-N-(6-phenoxy-3-pyridinyl)acetamide, in temporal lobe epilepsy patients, compared with healthy controls (27). Changes in TSPO expression in the choroid plexus could therefore play a role in (or serve as a molecular sensor for) different neurologic diseases and thus warrant further investigation.

There have been several PET imaging studies using TSPO radioligands in different mouse models of AD, which have provided useful information about the feasibility of imaging this target in AD mice, and also about which histologic markers correlate with TSPO imaging. For example, Venneti et al. showed that 11C-PK11195 brain uptake increased with age of their AD mice and that the PET signal moderately correlated with levels of microglia as determined by Iba1 staining (r2 = 0.59, P = 0.04) (28). More recently, Maeda demonstrated a strong relationship between N-benzyl-N-ethyl-2-(7-11C-methyl-8-oxo-2-phenyl-7,8-dihydro-9H-purin-9-yl)acetamide autoradiography and tau-induced neurodegeneration in PS19 AD mice (overexpressing mutant human tau) (29). In the latter study, no significant differences were observed between TSPO PET images of 24-mo-old wt and transgenic mice in the cortex or hippocampus until normalized to the striatum, whereas in our current studies with 18F-PBR06 we observed a significant increase in cortical/hippocampal uptake in 15- to 16-mo-old transgenic mice, compared with wts, before normalization. Additionally, our current studies are the first to show a correlation between TSPO staining, activated microglia (via CD68 staining), and TSPO PET signal in AD mice (Fig. 7). This type of information is critical to understanding the in vivo accuracy of a PET tracer for its desired target.

Because the studies reported by Venneti and Maeda were conducted in different AD mouse models, it is difficult to draw conclusions about which TSPO tracer is most suitable for imaging neuroinflammation in AD. To better understand how different TSPO tracers compare with each other, we need to conduct systematic studies to evaluate the sensitivity and accuracy of TSPO tracers in the same AD mouse model.

We are currently planning to compare 18F-PBR06 with newer TSPO radiotracers, such as N,N-diethyl-9-(2-(fluoro-18F)ethyl)-5-methoxy-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1H-carbazole-4-carboxamide (30), and other 18F TSPO tracers in the same APPL/S mice. Subsequent work will involve using the most sensitive TSPO PET tracer for therapy-monitoring studies to evaluate therapeutics that directly or indirectly affect neuroinflammation in both mouse and human.

Conclusion

This study is the first characterization of 18F-PBR06 in a mouse model of AD. Results from this work provide definitive evidence that the observed PET signal in the cortex and hippocampus of 15-to 16-mo-old APPL/S mice correlates, in both a temporal and a spatial manner, with levels of TSPO and activated microglia. Although we could not visualize significant differences in 18F-PBR06 PET signal in younger APPL/S mice (in which levels of microglial activation were less pronounced), we were able to quantify this difference using ex vivo autoradiography. These findings will certainly affect and guide future research involving the use of 18F-PBR06 for imaging mouse models of AD, especially when selecting the age of mice for therapy-monitoring studies and ensuring that high-resolution ex vivo autoradiography is performed to complement small-animal PET imaging data. Overall these results serve as a proof of principle, highlighting the potential of 18F-PBR06 PET for imaging activated microglia/TSPO in the progression and treatment of AD. Studies investigating the use of this tracer in human AD patients and for screening/evaluating novel AD therapies in mice are currently under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Victor W. Pike and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) for generously supplying precursor/standard for radiosynthesis of 18F-PBR06. We also thank Dr. Timothy Doyle, Dr. Laura Pisani, and Dr. Frezghi Habte, from the small-animal imaging facility (SAIF) at Stanford, for their technical support with PET/CT, MR imaging, and image analysis, respectively.

Financial support for the study was provided by Stanford University Department of Radiology internal funds (FTC), National Cancer Institute ICMIC P50 grant CA114747 (SSG), the Koret/Taube Foundations (FML), Jean Perkins Foundation (FML), and the Horngren Family (FML).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron B, Landreth GE. Inflammation, microglia, and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitz TM, Town T. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: it's all about context. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:314185. doi: 10.1155/2012/314185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James ML, Gambhir SS. A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:897–965. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippi M, Agosta F, Frisoni GB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer's disease: from diagnosis to monitoring treatment effect. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:1198–1209. doi: 10.2174/156720512804142949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisoni GB, Fox NC, Jack CR, Scheltens P, Thompson PM. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:67–77. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Song X, Beyea S, D'Arcy R, Zhang Y, Rockwood K. Advances in perfusion magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen MK, Guilarte TR. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO): molecular sensor of brain injury and repair. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarf AM, Kassiou M. The translocator protein. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:677–680. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.086629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benavides J, Fage D, Carter C, Scatton B. Peripheral type benzodiazepine binding sites are a sensitive indirect index of neuronal damage. Brain Res. 1987;421:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilms H, Claasen J, Röhl C, Sievers J, Deuschl G, Lucius R. Involvement of benzodiazepine receptors in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases: evidence from activated microglial cells in vitro. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen DRJ, Matthews PM. Imaging brain microglial activation using positron emission tomography and translocator protein-specific radioligands. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;101:19–39. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387718-5.00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, et al. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet. 2001;358:461–467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauveau F, Boutin H, Van Camp N, Dollé F, Tavitian B. Nuclear imaging of neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review of [11C]PK11195 challengers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2304–2319. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luus C, Hanani R, Reynolds A, Kassiou M. The development of PET radioligands for imaging the translocator protein (18 kDa): what have we learned? J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2010;53:501–510. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briard E, Shah J, Musachio J. Synthesis and evaluation of a new 18F-labeled ligand for PET imaging of brain peripheral benzodiazepine receptors [abstract] J Labeled Compd Radiopharm. 2005;48 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimura Y, Kimura Y, Siméon FG, et al. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry in humans of a new PET ligand, 18F-PBR06, to image translocator protein (18 kDa) J Nucl Med. 2010;51:145–149. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Mante M, Sisk A, Masliaha E. Early formation of mature amyloid-beta protein deposits in a mutant APP transgenic model depends on levels of abeta(1-42) J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:573–582. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TVV, Shen L, Vander Griend L, et al. Small molecule p75NTR ligands reduce pathological phosphorylation and misfolding of tau, inflammatory changes, cholinergic degeneration, and cognitive deficits in ABPPL/S transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:459–483. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lartey FM, Ahn GO, Shen B, et al. PET imaging of stroke-induced neuroinflammation in mice using [18F]PBR06. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James ML, Shen B, Zavaleta CL, et al. New positron emission tomography (PET) radioligand for imaging σ-1 receptors in living subjects. J Med Chem. 2012;55:8272–8282. doi: 10.1021/jm300371c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gandelman MS, Baldwin RM, Zoghbi SS, Zea-Ponce Y, Innis RB. Evaluation of ultrafiltration for the free-fraction determination of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radiotracers: beta-CIT, IBF, and iomazenil. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:1014–1019. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600830718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waerzeggers Y, Monfared P, Viel T, Winkeler A, Jacobs AH. Mouse models in neurological disorders: applications of non-invasive imaging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:819–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cymerman U, Pazos A, Palacios JM. Evidence for species differences in “peripheral” benzodiazepine receptors: an autoradiographic study. Neurosci Lett. 1986;66:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krzyzanowska A, Carro E. Pathological alteration in the choroid plexus of Alzheimer's disease: implication for new therapy approaches. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:75. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serot JM, Béné MC, Foliguet B, Faure GC. Morphological alterations of the cho-roid plexus in late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;99:105–108. doi: 10.1007/pl00007412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirvonen J, Kreisl WC, Fujita M, et al. Increased in vivo expression of an inflammatory marker in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:234–240. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.091694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venneti S, Lopresti BJ, Wang G, et al. PK11195 labels activated microglia in Alzheimer's disease and in vivo in a mouse model using PET. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1217–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda J, Zhang MR, Okauchi T, et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic imaging of glial responses to amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4720–4730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3076-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wadsworth H, Jones PA, Chau WF, et al. [18F]GE-180: a novel fluorine-18 labelled PET tracer for imaging translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1308–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.