The recent publication by Van Lunzen et al (HARNESS) evaluated the efficacy and safety of switching HIV infected adults from a stable regimen of 2 NRTIs with a third antiretroviral (ART) agent to either ritonavir boosted atazanavir (ATV/r) 300/100 mg plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine 300/200 mg once daily (ATV/r+TDF/FTC) or ATV/r plus raltegravir 400 mg twice daily (ATV/r+RAL)1. Interestingly a lower proportion of participants in the ATV/r+RAL arm maintained viral suppression at weeks 24 and 48. There was no immunologic benefit or reduction in adverse events with switching. In fact, tolerability of the ATV/r+RAL arm was lower due to dyslipidemia and pill burden. We also performed a study evaluating an NRTI sparing regimen in treatment naïve HIV infected persons using a similar approach.

From October 2008 to November 2009, the California Collaborative Treatment Group (CCTG) performed a randomized, open-label 48 week, multicenter study comparing the efficacy, safety and tolerability of RAL + ritonavir boosted lopinavir (LPV/r) 400/100 mg twice daily to a fixed dose combination of efavirenz 600 mg (EFV)+ TDF/FTC daily (EFV/TDF/FTC) in HIV-infected, treatment naïve subjects (N=51). The study was approved by local institutional review boards and all participants underwent informed consent prior to enrollment. Fifty-one subjects were randomized (25 in EFV/TDF/FTC and 26 in RAL+LPV/r) and included in the analyses with documentation of baseline characteristics, HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell counts and resistance testing. The primary efficacy analysis used a linear mixed effects model to assess the difference in the HIV RNA decay rates in the first 2 weeks between the treatment groups. Repeated HIV RNA Measured at baseline, day 2, 7, 10 and 14 were treated as the outcome. The fixed effects included time, treatment group, and treatment group-by-time interaction. The random effects included both intercept and slope. Secondary analysis also compared the proportion of subjects with undetectable RNA (HIV viral load < 50 copies/mL) at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36 and 48 between the two groups using Fisher's exact test.

The majority (96%) of participants were men; with a median age of 43 years (IQR: 31, 48). Eighty-four percent were White and 9.8% Black with 51% Hispanic. The median baseline viral load was 4.7 log10 copies/mL (IQR: 4.1,4.9), the median CD4 count was 358 cells/mm3 (IQR: 176, 459). There were no statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics between treatment arms.

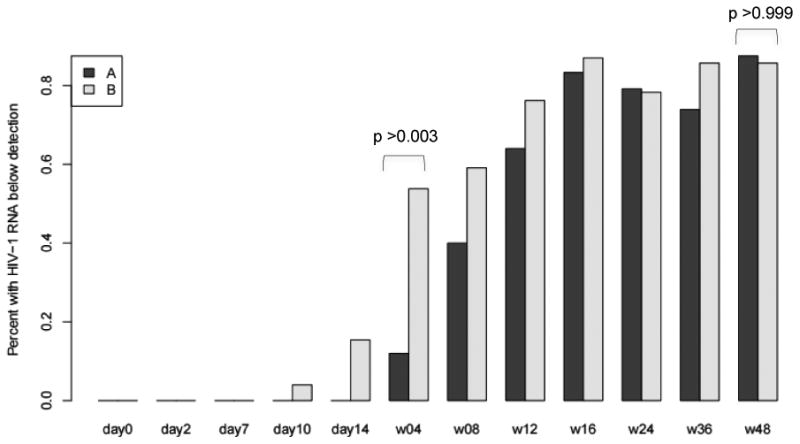

Compared with those in the EFV/TDF/FTC arm, participants in the RAL+LPV/r group demonstrated significantly more rapid viral decay in the first two weeks (-0.16 vs -0.13 log10/day, p=0.0007) and a higher proportion demonstrated an undetectable HIV RNA at week 4 (54% vs 12% p = 0.003). However, no differences in viral suppression between the two groups were observed and at week 8 and week 48 (86% vs 87.5%, p>0.99, figure 1). No differences were observed in the CD4 T cell dynamics between the arms over the 48 weeks. Unlike HARNESS we did not observe the presence of integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) resistance in person failing RAL + LPV/r.

Figure 1.

Proportion of study participants (A-dark gray EFV/FTC/TDF and B-light gray RAL+LPV/r) with an undetectable HIV viral load over time ignoring the missing RNA measurements due to early study discontinuation between week 4 and week 48. Significant difference are noted between arms at week 4 (with a higher proportion of persons in the RAL+LPV/r arm achieving an undetectable HIV viral load) but no difference is observed at week 48.

We also evaluated self-reported adherence (ACTG recall questionnaire) as the RAL+LPV/r arm necessitated a higher pill count and more frequent dosing than EFV/TDF/FTC. Overall assuming missing equals not adherent, the proportion of subjects with perfecta dherence was low (25%) in this study with the EFV/TDF/FTC arm demonstrating a slightly higher but not significantly different proportion with adherence than the RAL+LPV/r arm (36% vs 15%, respectively, p=0.12). Frequency of all reported adverse events also showed no significant difference between the two arms (60% in the EFV/TDF/FTC arm vs. 50% in the RAL+LPV/r arm, p=0.58).

In CCTG 589 initiation of RAL+LPV/r did result in a higher proportion of participants achieving an undetectable HIV VL at week 4, as would be expected with an INSTI based regimen. However the difference in virologic suppression between arms was not sustained over time and did not result in immunologic benefit. There were no differences noted in terms of side effects, but persons on RAL+LPV/r did report lower rates of adherence.

The use of an INSTI combined with a protease inhibitor (PI) offers possible therapeutic advantages over nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors combined with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase in relation to: (1) antiviral potency given the combination of both late (PI) and mid-cycle (INSTI) viral target inhibitors allowing for more efficient termination of viral replication from cellular reservoirs and more rapid early plasma viral decay2,3, and (2) immune recovery4-7. Studies of combination therapy with INSTI+PI in HIV infected persons who are naive to therapy have demonstrated rapid early plasma viral decay, which may be beneficial in that it minimizes onward HIV transmissions8. This may have benefit in select patients where the goal is rapid virologic suppression such as in pregnant women with a detectable HIV viral load. Additionally, studies evaluating INSTI + PI therapy do not document long term virologic or immunologic benefit8-10, but some studies (a switch study and an NRTI and ritonavir sparing study) did demonstrate a higher risk for development of INSTI resistance mutations1,9 and in at least one study in ART-naïve showed a higher failure rate in subjects with low CD4 and HIV viral loads > 100,000 copies/mL8. These observations have led to the recommendations from multiple guideline panels that inclusion of NRTIs in patients who are ART naïve or switching ART is the preferred treatment approach11. The interpretation of the results of CCTG 589 and HARNESS was limited by small sample sizes and adherence issues. Yet our experiences highlight that the use of a twice daily INSTI (RAL is the only INSTI evaluated in all the studies to date) combined with a PI is not an ideal regimen for routine care. It remains unknown if combinations of a PI with a daily INSTI confers additional virologic or immunologic benefits to people living with HIV and would benefit from further evaluation. However this question may be less relevant with the recent approval of the novel NRTI, tenofovir alafenamide which exhibits potent viral suppression and reduced toxicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors specifically want to provide heartfelt thanks to Stefan Schneider from Living Hope Clinical Foundation, CA, USA and Ashwaq Hermes from Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA. We thank all of the patients for their participation in the study.

Financial Support: This publication was supported by the California HIV Research Program grant MC08-SD-700. Support also came in part by the National Institutes of Health, Grant R01 HD083042, R21 MH100974, R24 AI106039 to MYK, Additionally this publication was supported by the University of California, San Diego Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI036214), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, and NIDDK. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Clinical trials registry: NCT00752856 (http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov)

California Collaborative Treatment Group (CCTG) 589 Protocol Team Members: In addition to the authors, other members of the CCTG 589 protocol team included the following: M. Witt (HUCLA), J. Tilles (UCI), R. Larsen (USC); R. Thomas, F. Wang, and E. Seefried (University of California, San Diego).

Potential conflicts of interest: Drs. Karris, Bowman, Goicoechea, Rieg, Kerkar, Jain, Kemper and Ms. Sun have no conflicts of interest to report. MPD receives grant support from BMS, Merck, Gilead, Serono, and ViiV and has served as a consultant to Serono. Dr. Haubrich is an employee of Gilead Sciences.

References

- 1.van Lunzen J, Pozniak A, Gatell JM, et al. Switch to ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus raltegravir in virologically suppressed patients with HIV-1 infection: a randomized pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podsadecki T TM, Fredrick L, Lawal A, Berstein B. Lopinavir/Ritonavir (LPV/r) Combined with Raltegravir (RAL) Provides More Rapid Viral Decline Than LPV/r Combined with Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) in Treatment-naive HIV-1 Infected Subjects. 15th Annual Conference of the British HIV Association (BHIVA); 1-3 April 2009; Liverpool, UK. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray JM, Emery S, Kelleher AD, et al. Antiretroviral therapy with the integrase inhibitor raltegravir alters decay kinetics of HIV, significantly reducing the second phase. AIDS. 2007;21(17):2315–2321. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steigbigel RT, Cooper DA, Kumar PN, et al. Raltegravir with optimized background therapy for resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):339–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartlett JA, Fath MJ, Demasi R, et al. An updated systematic overview of triple combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2051–2064. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247578.08449.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlahakis SR, Bren GD, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Trushin SA, Schnepple DJ, Badley AD. Flying in the face of resistance: antiviral-independent benefit of HIV protease inhibitors on T-cell survival. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(3):294–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitrak DL ER, Novak RM, Linnares-Diaz M, Tschampa JM. Beneficial Effects of a Switch to a Lopinavir/ritonavir-Containing Regimen for Patients with Partial or No Immune Reconstitution with Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) Despite Complete Viral Suppression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raffi F, Babiker AG, Richert L, et al. Ritonavir-boosted darunavir combined with raltegravir or tenofovir-emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults infected with HIV-1: 96 week results from the NEAT001/ANRS143 randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1942–1951. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozal MJ, Lupo S, DeJesus E, et al. A nucleoside- and ritonavir-sparing regimen containing atazanavir plus raltegravir in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV-infected patients: SPARTAN study results. HIV Clin Trials. 2012;13(3):119–130. doi: 10.1310/hct1303-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ofotokun I, Sheth AN, Sanford SE, et al. A switch in therapy to a reverse transcriptase inhibitor sparing combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and raltegravir in virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients: a pilot randomized trial to assess efficacy and safety profile: the KITE study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28(10):1196–1206. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battegay M, Elzi L. Does HIV antiretroviral therapy still need its backbone? Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1908–1910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]