Abstract

Purpose

Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (BPM) is effective in reducing the risk of breast cancer in women with a well-defined family history of breast cancer or in women with BRCA 1 or 2 mutations. Evaluating patient-reported outcomes following BPM are thus essential for evaluating success of BPM from patient’s perspective. Our systematic review aimed to: (1) identify studies describing health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients following BPM with or without reconstruction; (2) assess the effect of BPM with or without reconstruction on HRQOL; and, (3) identify predictors of HRQOL post BPM.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of literature using the PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane databases were searched.

Results

The initial search resulted in 1082 studies; 22 of these studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Post BPM, patients are satisfied with the outcomes and report high psychosocial well-being and positive body image. Sexual well-being and somatosensory function are most negatively affected. Vulnerability, psychological distress and preoperative cancer distress are significant negative predictors of quality of life and body image post BPM.

Conclusion

There is a paucity of high quality data on outcomes of different HRQOL domains post BPM. Future studies should strive to use validated and breast-specific PRO instruments for measuring HRQOL. This will facilitate shared decision-making by enabling surgeons to provide evidence-based answers to women contemplating BPM.

Keywords: Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, Risk reducing mastectomy, Quality of life, Patient reported outcomes, Systematic Review

Introduction

Prophylactic mastectomy involves removal of healthy breasts for prevention of breast carcinoma. Indications for bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (BPM) may include: 1) BRCA 1 or 2 mutations or other genetic susceptibility; 2) strong family history with no demonstrable mutation; 3) histological risk factors; and/or, 4) difficult surveillance [1]. Two independent studies have shown that the risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 years is 57% to 65% in women with a BRCA 1 mutation and 45% to 47% in women with a BRCA 2 mutation [2,3]. Importantly, BPM has been shown, to reduce the risk of breast cancer by up to 95% in women with BRCA 1 or 2 gene mutations and up to 90% in women with strong family history of breast cancer [4-7].

That said, BPM is a major elective and irreversible surgery that may result in complications from the surgical removal of both breasts and/or any subsequent reconstructive surgeries, a permanent change in a woman’s outward appearance, and potential changes in her health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Thus, while bilateral prophylactic mastectomy may be an attractive option in terms of reducing the risk of breast cancer, the decision to proceed surgically can have significant consequences and requires careful deliberation. Alternative options for high-risk individuals may instead include regular breast screening and/or chemoprevention.

In order to facilitate decision-making for women at high risk of breast carcinoma, the benefits and drawbacks of each approach should be well elucidated. This goes without saying for any surgical intervention but is especially important when considering preference-sensitive care and where there is more than one clinically appropriate treatment option for the condition. Thus, when considering BPM, patients should be informed not only of the impact that prophylactic surgery has on cancer incidence and survival, but also on expected HRQOL outcomes. This includes information about potential changes in body image, psychosocial, sexual and physical well-being after mastectomy with or without reconstruction. With this knowledge, patients and providers alike will be better equipped to make the best individualized decision for high risk women.

The overriding goal of this systematic review was to thus summarize the existing body of literature that serves to evaluate patient reported outcomes in women post BPM. More specifically, the purpose of this study was threefold: 1) to identify studies that describe health related quality of life in women after BPM with or without reconstruction; 2) to assess the effect of BPM on HRQOL; and, 3) to identify predictors of HRQOL post BPM.

Methods

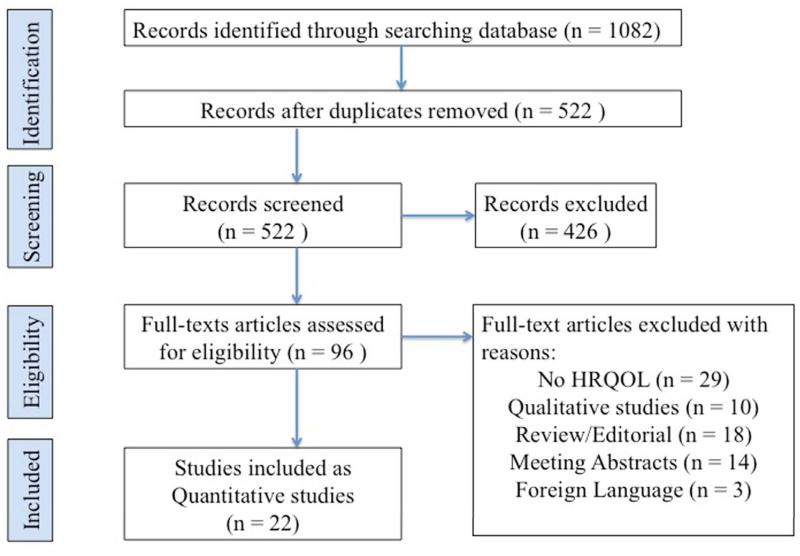

This systematic review was designed and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1) [8], and is registered with PROSPERO (CRD 42014012882) [9].

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for systematic review methodology as per PRISMA guidelines

Search Strategy

We performed a systematic search of articles published in peer-reviewed journals in December 2014 using PubMed (1945-2014), Embase (from 1966-2014), Cochrane (1898-2014), Scopus (1960-2014), Web of Science (1945-2014), and PsycInfo (1860-2014). We searched for articles in all available languages. Two categories of terms were searched: (1) prophylactic mastectomy and (2) quality of life. In PubMed and Cochrane, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used (mastectomy, quality of life, sexuality, patient satisfaction, and body image) as well as keywords. In Embase, Emtree terms were exploded (quality of life, sexuality, satisfaction, expectation, body image, and distress) in addition to keywords. In Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycInfo, only keywords were used.

Data analysis

Potentially relevant papers were examined by two reviewers (SR and VP) who worked independently, with discrepancies of opinion resolved by a third (CM). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies that evaluated health related quality of life after BPM using one or more patient reported outcomes (PRO) instruments; (2) studies published in a peer reviewed journal; and, (3) studies published in the English language. Citations for relevant articles were examined to identify additional articles. We did not evaluate the quality of the instruments used as this has been done elsewhere previously [10]. The MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies) criteria was then used to assess the quality of individual studies [11].

Results

An initial search identified a total of 1082 studies (PubMed: 242, Scopus: 232, Embase: 263, Web of Science: 309, PsycInfo: 30 and Cochrane: 6). After removing the duplicates, the total numbers of studies left were 522 and all of these were screened. On screening, 426 studies failed to meet our inclusion criteria and were removed from analysis. Full text was obtained for 96 studies. Out of these 96 studies, an additional 74 were excluded and 22 met our inclusion criteria as defined above [12-33]. The reasons for exclusion were: 29/74 studies did not evaluate HRQOL, 18/74 were reviews or discussion or editorials, 14/74 were meeting abstracts, 3/74 were published in a foreign language and 10/74 were qualitative studies (Fig. 1). Four studies were designed as prospective cohort studies [15,23,28,31], and rest were case series [12-14,16-22,24-27,29,30,32,33]. Three studies by Metcalfe et al. [16,17,19], two studies by Brandberg et al. [23,28], two studies by Gahm et al. [21,25] and another three studies by Gahm et al. [26,27,32] were each based on same patient populations. Eight studies were from Sweden [21,23-28,32], 5 from the US [12-14,20,22], 3 each from Canada [16,17,19] and the Netherlands [18,30,31], and 1 each from UK [15], Turkey [29] and Norway [33]. Four studies compared HRQOL in patients with and without breast reconstruction following BPM [12,14,16,30]. MINORS score for the 22 studies ranged from 5 to 12 (Range 0–16 for non-comparative studies and 0–24 for comparative studies; Ideal score being 16 and 24 respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

| Author, Year |

Country | Sample size (n) |

Typea | Postoperative timing of assessmentb |

PRO | Instrumentc | MINORS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stefanek, 1995 |

USA | 14 | CS | 6 – 30 months | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Patient satisfaction with decision to have BPM -Psychosocial well-being |

Ad hoc CES-D |

12 |

| Borgen, 1998 | USA | 370 | CS | 0.2 – 51.5 years | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Patient regret |

Ad hoc | 5 |

| Frost, 2000 | USA | 572 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc | 7 |

| Hatcher, 2001 | UK | 79 | PC | Preoperative, 6 and 18 months |

-Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

BIS GHQ-30 SAQ SSTAI |

7 |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

Canada | 60 | CS | 6 – 117 months | -Patient satisfaction with decision to have BPM -Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc BIBC BSI SAQ |

5 |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

Canada | 37 | CS | Mean 53.8 months | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc BSI |

5 |

| Contant, 2004 |

Netherlands | 61 | CS | 1 year | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc | 5 |

| Metcalfe, 2005 |

Canada | 60 | CS | Mean 52.2 months |

-Psychosocial well-being | QOLI | 5 |

| Geiger, 2007 | USA | 106 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Patient satisfaction with decision to have BPM -Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc CES-D |

6 |

| Gahm, 2007 | Sweden | 24 | CS | Mean 5 years | -Sexual well-being -Somatosensory function. |

Ad hoc | 5 |

| Spear, 2008 | USA | 27 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes | Ad hoc | 7 |

| Brandberg, 2008 |

Sweden | 90 | PC | Preoperatively, 6 and 12 months |

-Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc BIS HADS SAQ SF-36 |

7 |

| Isern, 2008 | Sweden | 30 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Patient regret |

Ad hoc | 6 |

| Gahm, 2010 | Sweden | 24 | CS | Median 29 months | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes | Ad hoc | 11 |

| Gahm, 2010 | Sweden | 36 | CS | Mean 5.4 years | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes | Ad hoc | 6 |

| Gahm, 2010 | Sweden | 59 | CS | Mean 29 months | -Psychosocial well-being -Sexual well-being -Patient regret -Somatosensory function |

Ad hoc DRS SF-36 |

6 |

| Brandberg, 2012 |

Sweden | 91 | PC | Preoperatively, 6 and 12 months |

-Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Somatosensory function |

Ad hoc | 7 |

| Sahin, 2013 | Turkey | 21 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes | MBROS-S | 6 |

| Eltahir, 2013 | Netherlands | 28 | CS | NA | -Psychosocial well-being | HADS | 9 |

| Gopie, 2013 | Netherlands | 48 | PC | Preoperatively, 6 months |

-Psychosocial well-being -Body image -Sexual well-being |

Ad hoc DRQ IES SF-36 |

7 |

| Gahm, 2013 | Sweden | 46 | CS | Median 29 months |

-Sexual well-being -Somatosensory function |

Ad hoc | 6 |

| Hagen, 2014 | Norway | 163 | CS | NA | -Patient satisfaction with outcomes -Patient satisfaction with decision to have BPM |

Ad hoc | 6 |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort.

NA: Not Available

BIBC: Body Image after Breast Cancer, BIS: Body Image Scale, BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory, CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale, DRQ: Dutch Relationship Questionnaire, DRS: Decision Regret Scale, GHQ: General Health Questionnaire, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, IES: Impact of Events Scale, MBROS-S: Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study – Satisfaction, QOLI: Quality of life index, SAQ: Sexual Activity Questionnaire, SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, SSTAI: Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Of the 22 studies, 12 used ad hoc questionnaires alone; 10 used 14 HRQOL instruments either alone or in combination with an ad hoc questionnaire. The HRQOL instruments used were: Body Image after Breast Cancer (BIBC), Body Image Scale (BIS), Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale (CES-D), Dutch Relationship Questionnaire (DRQ), Decision Regret Scale (DRS), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Impact of Events Scale (IES), Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study – Satisfaction (MBROS-S), Quality of life index (QOLI), Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ), 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI). Breast specific PRO instruments i.e. BIS and BIBC were used in three studies [15,16,23]. In only 1 study was a breast reconstruction specific instrument i.e. MBROS-S used [29] (Table 1).

Health related quality of life assessment

Patient Satisfaction with Outcome following BPM (Table 2, Fig. 2)

Table 2.

Patient Satisfaction with outcomes following BPM.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stefanek, 1995 |

14 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 78% and 93% of patients were satisfied with time to recover physically and emotionally respectively. |

| Borgen, 1998 |

370 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 84% of patients reported their cosmetic results as either excellent or acceptable. |

| Frost, 2000 | 572 | Ad hoc | CS | N | Y | + | Overall, 70% of patients were satisfied with their BPM. 69% in the reconstruction group and 100% in the non-reconstruction group were satisfied with their BPM. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

37 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 70% of patients were satisfied with cosmetic results of reconstruction. |

| Contant, 2004 |

61 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 87% of patients were satisfied with reconstruction. 77% patients were satisfied that breast reconstruction met expectations. |

| Geiger, 2007 |

106 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 61% of patients were satisfied with their quality of life. |

| Spear, 2008 |

27 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 100% of patients were satisfied with their reconstruction. |

| Isern, 2008 | 30 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 69% of patients were satisfied with their reconstruction. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

24 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 83% of patients reported that aesthetic results exceeded expectations. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

36 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | Median scores revealed that aesthetic satisfaction was high in patients who had round as well as anatomically shaped implants. |

| Brandberg, 2012 |

91 | Ad hoc | PC | Y | N | + | More than 80% of the patients were satisfied with the size of their breasts. |

| Sahin, 2013 |

21 | MBROS-S | CS | Y | N | + | 100% of patients were satisfied with their reconstruction. 90% patients were satisfied with size and shape of their breasts. |

| Hagen, 2014 |

163 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | More than 50% of the patients were satisfied with size, shape, symmetry and consistency of breasts. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

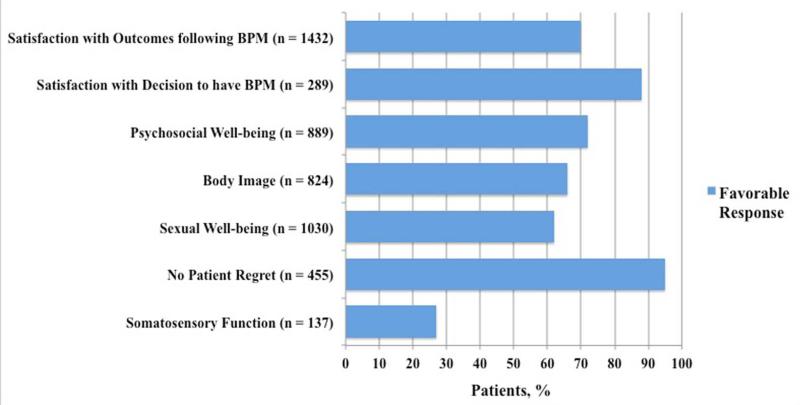

Fig. 2.

Summary results of proportion of patients reporting favorable results for each quality of life domain

Thirteen studies evaluated patient satisfaction after BPM with or without reconstruction. Twelve studies used ad hoc instruments based on likert scales. In all of the 13 studies evaluated, it was observed that the majority of the women (61–100%) were satisfied with BPM. Brandberg et al. reported that for majority of women (>70%), their perception of outcomes following BPM at 6 months and 1 year following surgery corresponded highly with their preoperative expectations [28]. Overall, 70% of the patients were satisfied with their outcomes following BPM.

Reconstruction vs. No reconstruction

Frost et al. reported that 69% of the patients who had BPM and postmastectomy reconstruction (n=534) were satisfied whereas 100% of patients who had BPM alone (n=19) were satisfied [14]. Only one study used a breast reconstruction specific instrument, MBROS-S, and reported that 100% (n=21) of the patients were satisfied with their reconstruction [29].

Patient Satisfaction with Decision-making (Table 3, Fig. 2)

Table 3.

Patient Satisfaction with decision to have BPM.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stefanek, 1995 |

14 | Ad hoc | CS | N | Y | + | 100% satisfied with decision to have PM. 64% were satisfied with their decision to have reconstruction. 100% were satisfied with their decision not to have reconstruction. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

60 | Ad hoc | CS | N | Y | + | 97% of patients were satisfied with decision to have PM. Mean satisfaction scores in reconstruction and no reconstruction groups indicated high satisfaction in both groups and no significant difference between the groups. |

| Geiger, 2007 | 106 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 84% of patients were satisfied with decision to have PM. |

| Hagen, 2014 | 163 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 88% of patients were satisfied with choosing PM. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Four studies specifically evaluated patient satisfaction with the decision to have BPM using ad hoc instruments and reported that 84–100% women were satisfied with their decision to undergo BPM [12,16,20,33].

Reconstruction vs. No reconstruction

Stefanek et al. noted that 64% of patients who had BPM and reconstruction (n=11) were satisfied compared with 100% of patients who did not have reconstruction (n=3) [12]. Metcalfe et al. reported similar mean likert scores of 4.8 and 4.7 in women who had reconstruction (n=38) and those who did not (n=22) respectively [17].

Psychosocial Well-being (Table 4, Fig. 2)

Table 4.

Psychosocial Well-being.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stefanek, 1995 |

14 | Ad hoc CES-D |

CS | N | N | + | 86% patients reported worry related to breast cancer to be a ‘moderate’ problem. Mean CES-D scores indicated no depression. |

| Frost, 2000 |

572 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | More than 80% patients reported no change or favorable effects on emotional stability, levels of stress and self esteem. 74% of patients reported diminished emotional concern about developing breast cancer. |

| Hatcher, 2001 |

79 | GHQ 30 SSTAI |

PC | N | N | + | Significant decrease in psychological morbidity and anxiety at 6 and 18 months compared with baseline. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

60 | BSI | CS | N | N | + | 32% patients had levels of psychological distress that required counseling. |

| Metcalfe, 2005 |

60 | QOLI | CS | N | N | + | More than 50% patients reported higher social and psychological well being than general population. |

| Geiger, 2007 |

106 | Ad hoc CES-D |

CS | N | Y | + | 43% patients reported that they were not concerned about breast cancer anymore. 65% had CES-D scores indicating no depression. |

| Brandberg, 2008 |

90 | HADS SF-36 |

PC | Y | N | + | Anxiety mean scores decreased significantly at 6 months and 1 year compared with baseline. No significant change in quality of life and depression over time. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

59 | SF-36 | CS | Y | N | + | No significant difference in social functioning and emotional role as compared to reference sample. |

| Gopie, 2013 |

48 | SF-36 IES |

PC | Y | N | + | General mental health significantly improved at 6 months compared with baseline. Cancer distress significantly decreased at 6 and 21 months compared with baseline. |

| Eltahir, 2013 |

28 | HADS | CS | N | Y | + | 11.5% and 3.8% patients reported anxiety and depression respectively after reconstruction. No anxiety and depression in women without reconstruction. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Ten studies evaluated psychosocial well-being after BPM and 72% of the patients reported favorable results. Three studies used ad hoc instruments alone or in combination with other instruments. Eight studies described a positive effect and two studies reported mixed results of BPM on a woman’s psychosocial well-being. Hatcher et al. found that psychological morbidity and anxiety decreased significantly at 6 and 18 months after BPM compared with baseline (p<0.05) [15]. Brandberg et al. observed that anxiety decreased significantly at 6 months and 1 year as compared with baseline (p<0.05) [23]. Gopie et al. reported a significant decline in cancer distress at 6 and 21 months post BPM (p<0.05) [31]. Stefanek et al. reported that 86% of the patients (n=12) who underwent BPM responded that worry related to breast cancer to be at least a moderate problem to them. At the same time, none of the patients had clinically significant levels of depression as measured by the CES-D [12]. Geiger et al. reported that 56% (n=59) of the patients who had BPM responded to be concerned about breast cancer and at the same time, 65% (n=69) patients had scores implying no depression on the CES-D [20].

Reconstruction vs. No reconstruction

Eltahir et al. found that in women (n=26) who had BPM and reconstruction, 11.5% and 3.8% had symptoms suggestive of anxiety and depression respectively on HADS. None of the women who had BPM alone (n=2) reported anxiety or depression on HADS [30].

Body Image (Table 5, Fig. 2)

Table 5.

Body Image.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frost, 2000 |

572 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 64% of patients reported either favorable or no change in body appearance. |

| Hatcher, 2001 |

79 | BIS | PC | N | N | + | No significant change in body image at 6 and 18 months post operatively. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

60 | Ad hoc BIBC |

CS | N | Y | + | Positive body image in both reconstruction and non-reconstruction groups. No significant difference in vulnerability, body stigma and transparency between the two groups. Patients who had reconstruction reported significantly more body concerns than the one who did not. 77% of patients reported either an improved or no change in self image |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

37 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 79% of patients reported either an improved or no change in body image. |

| Geiger, 2007 |

106 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 21% of patients were self-conscious about appearance. 58% of patients were satisfied with appearance when dressed. |

| Brandberg, 2008 |

90 | BIS | PC | Y | N | + | At 1 year: 52% self conscious, 60% felt less physically attractive, 83% dissatisfied with appearance, 76% difficult to see self naked, 74% dissatisfied with body. |

| Gopie, 2013 |

48 | Ad hoc | PC | Y | N | - | Body image decreased significantly at 6 months compared with baseline and was lower at 21 months. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Seven studies evaluated body image and five of these used an ad hoc instrument either alone or in combination with other instruments. Five studies described a positive body image following BPM, one study reported a negative body image and one study reported mixed results. On combining results from all the studies, 66% of the patients reported favorable effects on their body image following BPM. Three studies compared body image after BPM over time. Hatcher et al. reported no significant change in BIS median score of 4, indicating positive body image at 6 and 18 months [15]. Brandberg et al. observed no significant change between mean BIS scores at 6 and 12 months following BPM. However, they reported that at 1 year following BPM, more than 50% women felt self-conscious, less physically attractive and were dissatisfied with appearance and body [23]. Gopie et al. using an ad hoc instrument noted that body image declined significantly at 6 months following BPM [31].

Reconstruction vs. No reconstruction

Metcalfe et al. reported similar BIBC scores in patients who had BPM and reconstruction (n=38) and those who had BPM alone (n=22) [17].

Sexual Well-being (Table 6, Fig. 2)

Table 6.

Sexual Well-being.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frost, 2000 |

572 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | More than 75% patients reported either a favorable or no change in sexual relationships and feelings of femininity. |

| Hatcher, 2001 |

79 | SAQ | PC | N | N | + | Mean sexual discomfort and sexual pleasure scores implied higher level of sexual functioning at baseline and no significant change at 6 and 18 months. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

60 | Ad hoc SAQ |

CS | N | Y | + | Higher levels of sexual well being in both reconstruction and no reconstruction group and no significant difference in the mean scores between the two groups. 68% of patients reported either an improved or no change in sexual life. |

| Metcalfe, 2004 |

37 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 40% of patients reported change in their sexual lives following BPM. |

| Contant, 2004 |

61 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | 69% of patients agreed that they remained sexually attractive and 61% agreed that no major changes took place in their sexual lives. |

| Geiger, 2007 |

106 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | - | 43% of patients were satisfied with sex life. |

| Gahm, 2007 |

24 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | - | 22% of patients reported sexual feelings present in reconstructed breasts. |

| Brandberg, 2008 |

90 | Ad hoc SAQ |

PC | Y | N | ± | 31% and 27% of women reported positive reaction to femininity at 6 months and 12 months respectively.15% and 16% of women reported positive reaction to intimate situation at 6 months and 12 months respectively. Sexual pleasure decreased significantly from baseline to 1 year after BPM assessment. No significant change in sexual habit, discomfort and frequency. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

59 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | - | 85% of women reported loss or impaired sexual sensation. 75% reported negative effect on sexual enjoyment. |

| Gahm, 2013 |

46 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | - | 72% patients reported lost or decreased ability to experience sexual feelings in reconstructed breasts. |

| Gopie, 2013 |

48 | Ad hoc DRQ |

PC | Y | N | + | High satisfaction with sexual relationship at baseline and did not change significantly at 6 and 21 months. 18% of patients disagreed with being sexually attractive at baseline and no significant change in this proportion at 6 and 21 months. No significant change in relationship with partner over time. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Eleven studies evaluated sexual well-being after BPM and overall 62% of the patients reported favorable results. Ten studies used an ad hoc instrument alone or in combination with other instruments. Six studies described favorable effects on sexual well-being following BPM, four studies reported negative effects and one study reported mixed results. Hatcher et al. used the SAQ and reported no sexual discomfort and high sexual pleasure at 6 and 18 months following BPM with no significant change over time [15]. Gopie et al. used the DRQ and reported high sexual and partner relationship satisfaction at baseline that did not change significantly at 6 and12 months following BPM [31]. Brandberg et al. used the SAQ and stated that pleasure decreased significantly at 1 year post BPM compared with baseline. No significant differences in sexual habit or discomfort were noted. Less than 50% of women (15–31%), had a positive reaction to femininity or intimate situation at 6 and 12 months after BPM [23].

Reconstruction vs. No reconstruction

Metcalfe et al. noted similar mean SAQ scores in patients who had BPM and reconstruction (n=38) and those who had BPM alone (n=22) [17].

Patient Regret (Table 7, Fig. 2)

Table 7.

Patient Regret.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borgen, 1998 |

370 | Ad hoc | CS | N | N | + | 5% reported regret with decision to have BPM. |

| Isern, 2008 | 30 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | None reported regret. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

59 | DRS | CS | Y | N | + | None reported regret with decision to have PM. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Three studies evaluated patient regret and two of these used ad hoc instruments. Two studies reported none of the patients having any regret with their decision to have BPM. In summary, 95% of the patients did not report any regret following BPM.

Somatosensory Function (Table 8, Fig. 2)

Table 8.

Somatosensory Function.

| Author, Year |

Sample Size (n) |

Instrument | Type of Study |

Recon. (All) |

Compared Reconstruction vs. No Reconstruction |

Overall Finding |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gahm, 2007 |

24 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | ± | 80% and 69% had sensitivity present to touch and temperature respectively. 66% had spontaneous/stimulus evoked discomfort. |

| Gahm, 2010 |

59 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | - | 87% of patients experienced pain or discomfort in breasts. |

| Brandberg, 2012 |

91 | Ad hoc | PC | Y | N | - | 73% of patients reported negative sensibility of breasts at 6 months and 1 year post reconstruction. |

| Gahm, 2013 |

46 | Ad hoc | CS | Y | N | + | Approximately 6%, 27%, 27% and 11% of breasts did not have any sensation at all to touch, cold, heat and pain respectively. |

CS: Case Series. PC: Prospective Cohort. Recon.: Reconstruction. Y: Yes. N: No

+ More than 50% positive results or no significant negative changes over time.

− Less than 50% positive results or no significant positive changes over time.

± Mixed results.

Four studies evaluated somatosensory outcomes in women after BPM and all used ad hoc instruments. All of the patients in these studies had post mastectomy breast reconstruction. Gahm et al. reported that more than 69% (69–94%) patients had sensitivity present to touch and temperature after BPM with reconstruction [21, 32]. Brandberg et al. observed that 73% of the patients had negative sensibility in breasts at 6 months and 1 year following BPM [28].

Predictors of HRQOL

Metcalfe et al. determined that vulnerability (Body Image Scale) and psychological distress (Global Severity Index of BSI) were significant negative predictors of quality of life post BPM [19]. Gopie et al. reported that high preoperative cancer distress (IES) and low BMI predicted a negative body image post BPM and reconstruction whereas a higher preoperative general physical health (SF-36) predicted a better body image [31].

Willingness to repeat and recommend BPM

Stefanek et al. reported that 86% of women (n=12) were willing to recommend BPM to other women at high risk [12]. Frost et al. reported that 67% (n=381) of the women, who had BPM, would definitely or probably choose to have BPM again [14]. Spear et al. described that 100% of women (n=11) in their study were willing to undergo reconstruction again [22]. Gahm et al. noted that 92% of patients (n=22) would recommend BPM to another woman at high risk for developing breast cancer [25].

Initiation of discussion

Borgen et al. reported that the discussion of BPM was initiated by the physician in 70% of women and 30% of women initiated it themselves. 7.5% of women (n=19) in whom discussion about BPM initiated by physician reported regret. Two percent of women (n=2) who initiated the decision about BPM themselves, reported regret (p<0.05) [13]. Frost et al. evaluated the variables associated with patient satisfaction after BPM. Physician’s advice as the main reason to opt for BPM was associated with dissatisfaction [14].

Discussion

In recent years, a new breast cancer treatment paradox has emerged. The current approach toward treating breast cancer is to take out as minimal breast tissue as possible and avoid breast reconstruction surgery [34]. However, for a woman who has a future risk of breast cancer and has healthy breasts at present, the approach to reduce the risk of cancer is to remove both healthy breasts in their entirety and consider postmastectomy reconstructive surgery. Information regarding expected HRQOL will thus play an important role in the decision-making process of women considering BPM. To our knowledge, this is the first ever systematic review which evaluates patient reported outcomes after BPM with or without reconstruction.

Overall, our results suggest that women are highly satisfied with both their outcomes following BPM as well as their decision to have BPM. Ten of the 22 studies evaluated psychosocial well-being and reported that BPM does not cause significant negative effects on psychosocial well being. Importantly, however, two independent studies suggested that a high proportion of women expressed persistent cancer worry following BPM [12,20]. Seven studies evaluated body image after BPM, five of which reported that women maintained a positive body image after surgery. Three prospective studies reported body image at two time points after BPM, and two of those reported positive results. Using the BIS, Hatcher et al. and Brandberg et al. reported no significant change in body image over time after BPM [15,23]. By contrast, using an ad hoc instrument, Gopie et al. reported a significant negative change in body image after BPM at 6 and 1 year [31]. Examination of women’s sexual well-being after BPM reveals mixed results. Six of the eleven studies reported no negative effects on sexual well-being in women post BPM whereas four studies reported significant negative effects on sexual well-being. Gahm et al. reported that a significant proportion of patients had decreased or loss of sexual feelings in their reconstructed breasts [21,27,32]. Additional evidence suggests that patients have persistent discomfort in their reconstructed breasts after BPM [21,27]. Thus, following breast reconstruction, majority of women experience some degree of loss of sensation and discomfort in the reconstructed breasts, which may impact upon their sexual well-being.

Interestingly, the studies that compared quality of life in those who underwent BPM with reconstruction versus BPM alone generally reported higher or similar satisfaction in the non-reconstruction cohorts [12,14,16,30]. Importantly, it is noted that the sample size of women who had BPM alone in these studies was very generally very small, ranging from 11 to 38 patients, making it difficult to draw any valid conclusions. Interestingly, it has also been hypothesized that women who chose BPM and postmastectomy reconstruction may have had different expectations regarding their outcomes than those who elected BPM alone - expectations that are perhaps more difficult to meet. Future investigations of the impact of patient expectations in this setting are thus warranted.

Another potential area for further investigations provided by this systematic review is about the role of physician in patient satisfaction after BPM. The results of two studies from the current review suggest that dissatisfaction or regret following BPM is associated with physicians initiating the topic of BPM [13,14].

One of the significant limitations of this review includes the fact that data presented has, in the majority of cases, been derived from using ad hoc instruments. These instruments have undergone neither a formal development nor validation process. In general, if an instrument cannot be relied upon to measure what it intends to measure, then the conclusions made from its data should be relied upon with caution. Additionally, many studies used generic instrument such as the SF-36 for measuring HRQOL in these patients. Generic instruments are not sensitive enough to measure physical and mental changes related specifically to BPM surgery with or without reconstruction. The BIS and BIBC were the only breast cancer specific questionnaires used but do not include questions pertaining to breast reconstruction. The MBROS-S was the only breast reconstruction specific instrument used in one study [29].

Furthermore, many studies in this systematic review had a very small sample size that makes their results less reliable. Most of the studies sent out self-reported surveys to measure patient satisfaction with BPM and many of them did not report the response rate. This may have caused volunteer bias as only women with positive outcomes may have decided to participate in these surveys. And finally, most of these studies measured HRQOL at one point of time and do not provide data about changes in different HRQOL domains after BPM over time.

Future studies should use validated and breast-surgery specific instruments such as the BREAST-Q for measuring patient satisfaction after BPM [35]. This will provide standardized results that can be compared with other similar studies. More longitudinal studies are required to observe changes in HRQOL after BPM over time. Further identification of potential risk factors for dissatisfaction after BPM with or without reconstruction is also warranted.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review show that overall patient reported quality of life is high after BPM. Most patients are satisfied with outcomes, and report a high psychosocial well-being and body image after BPM that does not change significantly over time. Sexual well-being and somatosensory function are the HRQOL domains most negatively affected after BPM. Patients who did not have reconstruction after BPM reported higher or similar HRQOL as those who did. These results should be seen, however in the light of less than ideal methodological qualities of the studies evaluated. Future studies must strive to use reliable, well-validated patient reported outcome instruments to measure quality of life after BPM. This will aid in arming the clinicians and patients alike with high quality data to facilitate their clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Shantanu N. Razdan declares that he has no conflict of interest. Vishal Patel declares that he has no conflict of interest. Sarah Jewell declares that she has no conflict of interest. Colleen M. McCarthy declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Giuliano AE, Boolbol S, Degnim A, Kuerer H, Leitch AM, Morrow M. Society of Surgical Oncology: position statement on prophylactic mastectomy. Annals Of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14(9):2425–2427. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(11):1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(5):1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, Crotty TP, Myers JL, Arnold PG, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(2):77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(9):967–975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, van 't Veer L, Garber JE, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: The PROSE Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(6):1055–1062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WL, Henzen-Logmans SC, Seynaeve C, Menke-Pluymers MB, et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(3):159–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1:2. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CM, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, King T, McCarthy C, Cordeiro PG, et al. Measuring quality of life in oncologic breast surgery: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures. Breast Journal. 2010;16(6):587–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2003;73(9):712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefanek ME, Helzlsouer KJ, Wilcox PM, Houn F. Predictors of and satisfaction with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24(4):412–419. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borgen PI, Hill AD, Tran KN, Van Zee KJ, Massie MJ, Payne D, et al. Patient regrets after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1998;5(7):603–606. doi: 10.1007/BF02303829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost MH, Schaid DJ, Sellers TA, Slezak JM, Arnold PG, Woods JE, et al. Long-term satisfaction and psychological and social function following bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(3):319–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatcher MB, Fallowfield L, A'Hern R. The psychosocial impact of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: prospective study using questionnaires and semistructured interviews. British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7278):76. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metcalfe KA, Esplen MJ, Goel V, Narod SA. Psychosocial functioning in women who have undergone bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Psychooncology. 2004;13(1):14–25. doi: 10.1002/pon.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metcalfe KA, Semple JL, Narod SA. Satisfaction with breast reconstruction in women with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: a descriptive study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114(2):360–366. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000131877.52740.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contant CME, van Wersch AME, Menke-Pluymers MBE, Tjong Joe Wai R, Eggermont AMM, Van Geel AN. Satisfaction and prosthesis related complaints in women with immediate breast reconstruction following prophylactic and oncological mastectomy. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2004;9(1):71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metcalfe KA, Esplen MJ, Goel V, Narod SA. Predictors of quality of life in women with a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Breast Journal. 2005;11(1):65–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geiger AM, Nekhlyudov L, Herrinton LJ, Rolnick SJ, Greene SM, West CN, et al. Quality of life after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14(2):686–694. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gahm J, Jurell G, Wickman M, Hansson P. Sensitivity after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery. 2007;41(4):178–183. doi: 10.1080/02844310701383977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spear SL, Schwarz KA, Venturi ML, Barbosa T, Al-Attar A. Prophylactic mastectomy and reconstruction: clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;122(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318177415e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandberg Y, Sandelin K, Erikson S, Jurell G, Liljegren A, Lindblom A, et al. Psychological reactions, quality of life, and body image after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women at high risk for breast cancer: a prospective 1-year follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(24):3943–3949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isern AE, Tengrup I, Loman N, Olsson H, Ringberg A. Aesthetic outcome, patient satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in women at high risk undergoing prophylactic mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Aesthetic Surgery. 2008;61(10):1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gahm J, Jurell G, Edsander-Nord A, Wickman M. Patient satisfaction with aesthetic outcome after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants. Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Aesthetic Surgery. 2010;63(2):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gahm J, Edsander-Nord A, Jurell G, Wickman M. No differences in aesthetic outcome or patient satisfaction between anatomically shaped and round expandable implants in bilateral breast reconstructions: a randomized study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;126(5):1419–1427. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8b01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gahm J, Wickman M, Brandberg Y. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with inherited risk of breast cancer--prevalence of pain and discomfort, impact on sexuality, quality of life and feelings of regret two years after surgery. Breast. 2010;19(6):462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandberg Y, Arver B, Johansson H, Wickman M, Sandelin K, Liljegren A. Less correspondence between expectations before and cosmetic results after risk-reducing mastectomy in women who are mutation carriers: a prospective study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012;38(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahin I, Isik S, Alhan D, Yildiz R, Aykan A, Ozturk E. One-staged silicone implant breast reconstruction following bilateral nipple-sparing prophylactic mastectomy in patients at high-risk for breast cancer. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2013;37(2):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eltahir Y, Werners LL, Dreise MM, van Emmichoven IA, Jansen L, Werker PM, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes between mastectomy alone and breast reconstruction: comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2013;132(2):201e–209e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829586a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopie JP, Mureau MA, Seynaeve C, Ter Kuile MM, Menke-Pluymers MB, Timman R, et al. Body image issues after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy with breast reconstruction in healthy women at risk for hereditary breast cancer. Familial Cancer. 2013;12(3):479–487. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gahm J, Hansson P, Brandberg Y, Wickman M. Breast sensibility after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Aesthetic Surgery. 2013;66(11):1521–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagen AI, Maehle L, Veda N, Vetti HH, Stormorken A, Ludvigsen T, et al. Risk reducing mastectomy, breast reconstruction and patient satisfaction in Norwegian BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Breast. 2014;23(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, Kokeny K, Agarwal J. Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surgery. 2014;149(3):267–274. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124(2):345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]