Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to create symptom indices – that is, scores derived from questionnaires – to accurately and efficiently measure symptoms of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, collectively referred to as urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS). We created these indices empirically, by investigating the structure of symptoms using exploratory factor analysis.

Materials and Methods

As part of the Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network, participants (N = 424) completed questionnaires including the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI), the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI), and the Interstitial Cystitis Problem Index (ICPI). Individual items from questionnaires about bladder and pain symptoms were evaluated by principal components and exploratory factor analysis to identify indices with fewer questions to comprehensively quantify symptom severity. Additional analyses included correlating symptom indices with symptoms of depression, a known comorbidity of patients with pelvic pain.

Results and Conclusions

Exploratory factor analyses suggested that two factors, pain severity and urinary severity, provided the best psychometric description of items contained in the GUPI, the ICSI, and the ICPI. These factors were used to create two symptom indices for pain and urinary symptoms. Pain, but not urinary symptoms, was associated with symptoms of depression in a multiple regression analysis, suggesting that these symptoms may impact patients with UCCPS differently; for pain severity, B (SE) = 0.24 (0.04), 95% CI of B = 0.16–0.32, β = 0.32, p < .001. Our results suggest that pain and urinary symptoms should be assessed separately, rather than combined into one total score. Total scores that combine the separate factors of pain and urinary symptoms into one score may be limited for clinical and research purposes.

Keywords: Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS), depression, factor analysis

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) are collectively referred to as urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS).1 Despite past efforts, UCPPS has an unknown etiology, is difficult to effectively treat, and negatively affects quality of life (QOL), work productivity, and healthcare use.2–7 In response, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases established the Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network, which employs a highly collaborative approach to better understand these syndromes including study of natural history, underlying pathophysiology, biomarkers, possible infectious etiology, and patient subgroups that are potentially relevant to treatment.8, 9 Because characterization and subtyping relies on precise symptom measurement, the purpose of this study was to identify the most effective symptom indices for characterizing UCPPS.

A number of symptom questionnaires have been developed to assess UCPPS.10–12 Among them, the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI) and the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom and Problem Indices (ICSI/ICPI) are used most frequently to assess the impact of UCPPS as well as the outcomes of clinical trials. These questionnaires differ in their assumptions about how symptoms cluster together, so it is necessary to look across symptom indices in a comprehensive, empirical way to identify key factors to characterize UCPPS. For example, the GUPI10 yields four scores: pain, urinary symptoms, QOL impact, and a total score. In contrast, the ICSI/ICPI11 are organized into two subscales for symptom frequency versus bother and problems. In total, the GUPI and the ICSI/ICPI yield six possible scores: “total symptoms”, pain, urinary symptoms, QOL impact, IC/BPS symptom score, and IC/BPS problem score. The goal of this paper was to simplify this list to a smaller number of indices, and to reduce the number of questions needed to assess UCPPS. In doing so, we sought to identify indices that could be efficiently and effectively used in clinical and research settings.

Pursuant to our goal, we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine questionnaire items that had been administered to participants with UCPPS as part of an observational study.8, 9 EFA can empirically resolve differences among questionnaire structures, and can also help to identify factors that can be used to create symptom indices. We also examined relationships with symptoms of depression, a known comorbidity of UCPPS.13–17 We had two hypotheses: 1) symptoms of UCPPS could be reduced to a small number of indices, and 2) these indices would show differential relationships with symptoms of depression.

Materials and Methods

Participants with UCPPS (N = 424; 55% female; 45% male) were recruited by seven sites: Washington University-St. Louis (n = 75, 18%), University of Washington (n = 71, 17%), University of Michigan (n = 70, 17%), University of California-Los Angeles (n = 66, 16%), University of Iowa (n = 61, 14%), Northwestern University (n = 58, 14%), and Stanford University (n = 23, 5%). Inclusion criteria included 1) a diagnosis of IC/BPS or CP/CPPS, with symptoms present during any 3 of the past 6 months (CP/CPPS) or the most recent 3 months (IC/BPS), 2) at least 18 years old, and 3) a non-zero score for bladder/prostate and/or pelvic region pain, pressure or discomfort during the past 2 weeks. Exclusion criteria included presence of a urethral stricture, neurological conditions affecting the bladder or bowel, autoimmune or infectious disorders, history of cystitis caused by tuberculosis or radiation or chemotherapies, history of non-dermatologic cancer, major psychiatric disorders, or severe cardiac, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease.8

The GUPI, ICPI/ICSI, and other questionnaires18,19 were completed at the baseline assessment of the Trans-MAPP Epidemiology/Phenotyping Study.8 Other urologic questionnaires (e.g., American Urological Association Symptom Index)18 were administered in this study, but these were not analyzed because they were considered redundant with the GUPI and ICSI/ICPI.

Measures

Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI)

The GUPI includes questions about urinary symptoms, QOL, and location and intensity of pain. Total scores range from 0–45; individual scores for the domains of pain, urinary symptoms, and QOL impact can also be derived.10 Certain items have sub-questions that can be analyzed individually. Item 1 asks men and women where they feel pain (e.g., testicles, entrance to the vagina); this was analyzed as a 0–4 indicator of the number of areas that were checked. Item 2 has four sub-questions about the presence of symptoms (e.g., pain or burning during urination). Items 3–9 are single questions that quantify the frequency and intensity of symptoms and QOL issues. In our analyses, 12 indicators were examined (Items 1, 2a-2d, 3–9), which includes all items of the GUPI.

Interstitial Cystitis Symptom and Problem Indices (ICSI/ICPI)

The ICSI and ICPI have four items each, which are summed.11 The range for the ICSI score is 0–20 whereas the range for the ICPI is 0–16. The ICSI includes three questions about urinary symptoms and one question about bladder pain or burning. The ICPI asks about these same concepts, but focuses on how much of a problem they have been.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20

The HADS is used to measure symptoms of anxiety and depression in medical patients. Both scales range from 0–21. A review of over 700 studies supported the ability of the HADS to discriminate anxiety from depression, and to measure symptom severity in various populations.21 We examined only the depression subscale.

Symptom and Health Care Utilization Questionnaire (SYMQ)

These scales were specifically designed for MAPP. Items 1–3 and 5 measure pain, pressure, and discomfort in the pelvic region, and urinary urgency and frequency on an 11-point scale. Item 4 is a 4-point ordinal scale of the frequency of voiding in a recent 24-hour period. Because the SYMQ has not been previously validated, it was included only in an initial, discovery-based principal components analysis (see Appendix), but not in the EFA (see below). We also examined how well the SYMQ correlated with other study measures.

Statistical analyses

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

We used EFA to examine the structure of twenty questionnaire items (4 from the ICSI, 4 from the ICPI, and 12 from the GUPI). EFA allows factors to be correlated,22 which is clinically more realistic because in practice some symptoms may be statistically grouped together, as well as be present together in individual patients. In brief, EFA seeks to find a small number of factors that can explain a correlation matrix among a set of questionnaire items. We planned to use the factors, derived from our EFA, to create simple, empirically-based indices.

We used Mplus 7.3 using a robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) to obtain factor loadings, and the GEOMIN oblique factor rotation, which allows factors to intercorrelate.23 To guide the number of factors to extract, we examined a scree plot (not shown) as well as a parallel analysis that compared observed eigenvalues to the 95th percentile of a distribution of eigenvalues generated from simulations of correlation matrices derived from 20 random, Gaussian numbers.24, 25 Based on findings from EFA, we arranged items into simple indices for subsequent analyses.

Associations of pelvic pain and urinary symptoms with symptoms of depression

Multiple regression was used to examine the relationships among UCPPS symptoms and depressive symptoms. Based on the EFA, the HADS was regressed on UCPPS symptom scales and indices. Standardized regression coefficients were examined as a measure of effect size.26

Results

Age ranged from 19 to 82 years (M = 43.4, SD = 15.1). The racial distribution was: Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 8, 2%), Black/African American (n = 16, 4%), Caucasian (n = 369, 87%), and Other/More than one (n = 28, 7%). The sample was 7% Hispanic ethnicity (n = 28). Education was distributed as follows: 31 (7%) completed high school/GED equivalent, 163 (38%) had a bachelor-level university degree, 118 (28%) had completed some college, and 112 (26%) had a professional or graduate degree. Table 1 presents additional descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Baseline values for symptom indices overall and by sex.

| Total Sample | Females | Males | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Observed range |

Mean | SD | N | Observed range |

Mean | SD | N | Observed range |

Mean | SD | |

| GUPI Pain | 422 | 0–23 | 12.57 | 4.46 | 232 | 0–21 | 12.86 | 4.60 | 190 | 2–23 | 12.21 | 4.27 |

| GUPI Urinary | 424 | 0–10 | 5.29 | 2.96 | 233 | 0–10 | 5.74 | 2.97 | 191 | 0–10 | 4.73 | 2.86 |

| GUPI QOL | 424 | 0–12 | 7.71 | 2.87 | 233 | 0–12 | 7.82 | 2.94 | 191 | 0–12 | 7.58 | 2.78 |

| GUPI Total | 422 | 0–44 | 25.60 | 8.61 | 232 | 0–43 | 26.45 | 8.92 | 190 | 6–44 | 24.57 | 8.13 |

| ICSI | 421 | 0–20 | 9.73 | 4.72 | 231 | 0–20 | 10.76 | 4.50 | 190 | 0–20 | 8.48 | 4.70 |

| ICPI | 419 | 0–16 | 8.51 | 4.38 | 230 | 0–16 | 9.50 | 4.02 | 189 | 0–16 | 7.31 | 4.52 |

| HADS Depression | 422 | 0–20 | 5.40 | 4.20 | 232 | 0–20 | 5.32 | 4.30 | 190 | 0–20 | 5.49 | 4.09 |

| SYMQ1: Pain | 424 | 1–10 | 5.07 | 2.20 | 233 | 1–10 | 5.24 | 2.14 | 191 | 1–10 | 4.85 | 2.25 |

| SYMQ2: Urgency | 424 | 0–10 | 5.06 | 2.56 | 233 | 0–10 | 5.36 | 2.51 | 191 | 0–10 | 4.69 | 2.58 |

| SYMQ3: Frequency | 424 | 0–10 | 4.90 | 2.56 | 233 | 0–10 | 5.12 | 2.57 | 191 | 0–10 | 4.64 | 2.61 |

| SYMQ4: Void | 421 | 1–4 | 2.47 | 0.95 | 231 | 1–4 | 2.60 | 0.94 | 190 | 1–4 | 2.31 | 0.93 |

| SYMQ5: Pelvic Pain Symptoms | 423 | 0–10 | 5.19 | 2.34 | 232 | 0–10 | 5.37 | 2.32 | 191 | 0–10 | 4.97 | 2.34 |

| Pain Severity Index (GUPI Pain + ICSI Item4) | 422 | 1–28 | 14.99 | 5.58 | 232 | 1–26 | 15.78 | 5.65 | 190 | 2–28 | 14.03 | 5.36 |

| Urinary Severity Index (GUPI Urinary+ ICSI Items 1–3) | 421 | 0–25 | 12.59 | 6.23 | 231 | 1–25 | 13.57 | 6.07 | 190 | 0–25 | 11.39 | 6.22 |

Note. GUPI = Genitourinary Pain Index, ICSI = Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index, ICPI = Interstitial Cystitis Problem Index. Pain and Urinary indices were created on the basis of exploratory factor analysis (see Results and Table 3).

Exploratory Factor analysis

Parallel analysis suggested that a maximum of three factors would best describe the questionnaire items, so using EFA, we visually compared solutions with one, two, and three factors (Table 2). We rejected the three-factor solution because the eigenvalues from the real data and the simulated data were close for the third factor (1.57 vs. 1.33), which suggests that amount of variance accounted for by a third factor was not much greater that what would be expected by chance. In addition and importantly, the third factor was not meaningfully interpreted (Table 2). The two-factor solution, however, had a clear interpretation; the first factor had large loadings (> 0.4) for items about pelvic pain as well as QOL; the second factor had large loadings for items about urinary symptoms. The correlation between these two factors was .49 (95% CI, .41–.57), supporting the use of an oblique rather than an orthogonal rotation. Because the two-factor solution had a simple yet clinically meaningful interpretation, it was accepted as the most appropriate solution.

Table 2.

Factor loadings for one-, two-, and three-factor solutions (N = 424)

| Factor Loadings One-factor model |

Two-factor model | Three-factor model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Item description | Factor 1 | Factor 1: “Pelvic Pain” |

Factor 2: “Urinary Symptoms” |

Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

| GUPI 1 | Number of pelvic areas checked (0–4) | 0.39 | 0.63 | −0.12 | 0.78 | −0.33 | 0.01 |

| GUPI 2a | Pain or burning during urination (Yes/No) | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.45 | −0.01 | 0.18 |

| GUPI 2b | Pain or discomfort during or after sexual climax (Yes/No) | 0.31 | 0.54 | −0.12 | 0.68 | −0.35 | 0.09 |

| GUPI 2c | Pain or discomfort during bladder filling (Yes/No) | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.22 |

| GUPI 2d | Pain or discomfort relieved by voiding (Yes/No) | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.24 |

| GUPI 3 | How often have you had pain or discomfort…? (0–5) | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.83 | −0.06 | −0.27 |

| GUPI 4 | Which number best described your AVERAGE pain or discomfort…? (0–10) | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.12 | −0.18 |

| GUPI 5 | How often have you had a sensation of not emptying your bladder…? (0–5) | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.02 |

| GUPI 6 | How often have you had to urinate again less than two hours after you finished urinating…? (0–5) | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 1.01 | −0.28 |

| GUPI 7 | How much have your symptoms kept you from doing the kinds of things you would usually do…? (0–3) | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.27 |

| GUPI 8 | How much do you think about your symptoms…? (0–3) | 0.68 | 0.83 | −0.01 | 0.94 | 0.01 | −0.51 |

| GUPI 9 | If you were to spend the rest of life with your symptoms…? (0–6) | 0.63 | 0.79 | −0.02 | 0.89 | −0.02 | −0.43 |

| ICPI 1 | Frequent urination during the day (0–4) | 0.82 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.83 | −0.01 |

| ICPI 2 | Getting up at night to urinate (0–4) | 0.77 | −0.17 | 0.91 | −0.29 | 1.03 | 0.02 |

| ICPI 3 | Need to urinate with little warning (0–4) | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.53 |

| ICPI 4 | Bladder pain, discomfort, pressure, burning (0–4) | 0.82 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

| ICSI 1 | Strong need to urinate (0–5) | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.47 |

| ICSI 2 | Frequent urination during the day (0–5) | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.95 | −0.01 | 1.02 | −0.25 |

| ICSI 3 | Getting up at night to urinate (0–5) | 0.63 | −0.23 | 0.82 | −0.35 | 0.95 | 0.00 |

| ICSI 4 | Bladder pain or burning (0–5) | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

Note. GUPI = Genitourinary Pain Index, ICSI = Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index, ICPI = Interstitial Cystitis Problem Index. Higher factor loadings indicate stronger relationships between items and factors; Factor loadings ≥ .4 are in bold. Principal components analysis as well as parallel analysis suggested a two-factor solution, so we named those two factors. The one- and three-factor solutions are presented for reference and comparison.

Formation of symptom indices

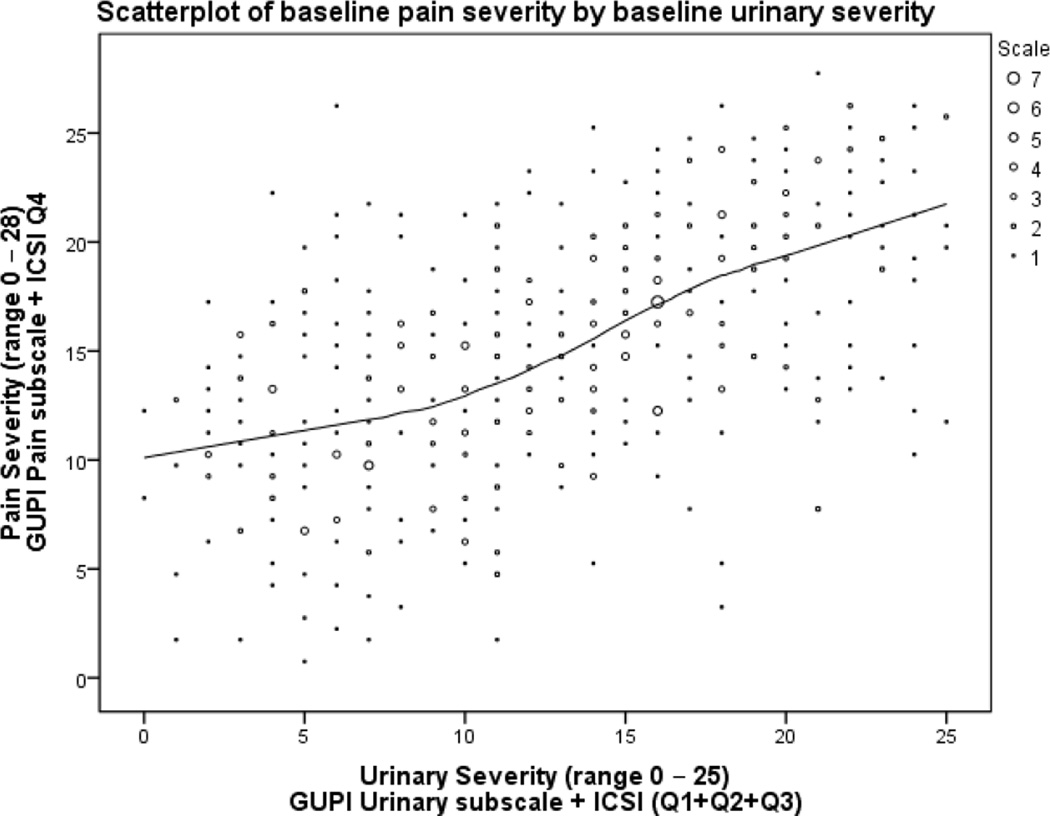

Based on the EFA, we created a “pain severity” index by summing item 4 from the ICSI with the GUPI pain subscale. Although QOL items loaded onto the same factor, we did not include them in the pain severity index because QOL is conceptually different from pain. Indeed, decreases in QOL may be the result of pain, as opposed to being the same as pain. We also created a “urinary severity” index by summing items 1, 2 and 3 of the ICSI with the items from the GUPI urinary subscale. The new pain and urinary were strongly correlated with factor scores calculated by the maximum a posteriori method,27 r = .92 (95% CI .91–.94) for pain severity, r = .95 (95% CI .94–.96) for urinary severity, suggesting that even with fewer items and a simple scoring algorithm, most of the information from the factors was captured. The correlation between the two indices was .56 (95% CI .49–.63, see Table 3). Figure 1 shows that there was substantial heterogeneity in symptoms, with some patients having high pain and low urinary symptoms and vice-versa. The indices are presented in the appendix.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of study measures

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pain severity index | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. Urinary severity index | 0.56 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. GUPI Pain | 0.97 | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. GUPI Urinary | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.48 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. ICSI | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. ICPI | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. SYMQ1: Pain | 0.72 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. SYMQ2: Urgency | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||

| 9. SYMQ3: Frequency | 0.52 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||

| 10. SYMQ4: Void | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |

| 11. SYMQ5: Pelvic Pain Symptoms | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| 12. HADS Depression | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.35 |

Note. N ≥ 416 for correlations. P values are not shown because all elements of this matrix were highly significant (p < .001) due to the large sample size

Figure 1.

Visual depiction of the association between the pain and urinary severity scales. A Loess smoother is shown to illustrate that the relationship is mostly linear.

Associations with symptoms of depression

To examine the association of symptoms of depression with UCPPS, we regressed the score from HADS depression scale on the pain and urinary indices (see Appendix). Depression was predicted by pain, B (SE) = 0.24 (0.04), 95% CI for B = 0.16–0.32, p < .001, with a medium effect size, β = 0.32. In contrast depression was not significantly related to urinary symptoms, B (SE) = 0.06 (0.04), 95% CI for B = −0.02–0.13, p = .127; the effect size was trivially small, β = 0.08. The regression of HADS depression on the GUPI pain and urinary subscales yielded almost identical results, with only pain as a significant predictor, B (SE) = 0.32 (0.05), 95% CI for B = 0.22–0.41, β = 0.33, p < .001.

Correlational analyses

There are several important observations to note from correlations among study measures (Table 3). First, the GUPI Pain and Urinary subscales correlate very highly with the symptom indices, suggesting that these two scales could also be used to effectively measure pain and urinary symptoms. Second, the ICSI and ICPI had a correlation of .89 with each other (95% CI, .87–.91), suggesting that they overlap highly, which justifies excluding the ICPI from index scores.

Discussion

We adopted an empirical approach to describing UCPPS by analyzing many symptoms in a large sample. These data support that in UCPPS, it is important to assess pain and urinary symptoms separately rather than combined together such as in the GUPI total score as well as in other IC/BPS questionnaires.12 Because our results indicate that UCPPS outcomes should be organized into pain and urinary symptoms, we have adopted these dual outcomes for future MAPP studies (see Appendix). In the clinic, these outcomes could be measured even more simply by just using the original GUPI Pain and Urinary subscales. In contrast, a composite measure that includes both pain and urinary symptoms in a single score (e.g., GUPI total score) may not provide adequate sensitivity to detect differential change in these two symptom domains. We therefore recommend that pain and urinary symptoms be assessed separately as this permits analyzing examining them individually. Consistent with the idea that pain and urinary symptoms are distinct, we showed that symptoms of depression were related to pain but not to urinary symptoms in a multiple regression analysis. This is not to say that urinary symptoms are unimportant to depression given the literature linking them,28, 29 although many past studies of depression and urinary symptoms have not statistically controlled for pain. Our data suggest, however, that pain and depression are closely linked in patients with UCPPS. It should also be noted that although one dimension of urinary severity was sufficient in our sample, there are questionnaires, such as the LUTS Tool,30 that assess a large number of symptoms individually that could be used to study individual symptoms from specific pathophysiologies (e.g., strictures causing split urine steam).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that pain and urinary symptoms should be assessed separately. Furthermore, total scores that combine pain and urinary symptoms into one score may be limited for clinical and research purposes. Pain and urinary symptoms can be measured separately using the GUPI or index scores (see Appendix). Future MAPP studies will investigate how pain and urinary symptoms are related to other important factors (e.g., urinary microbiota and protein biomarkers, neuroimaging), and whether these indices can be used to predict disease outcomes. Ultimately, patients need therapies that target one or both of these dimensions.

Supplementary Material

LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS

- MAPP

Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain

- UCPPS

urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes

- IC/BPS

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes

- CP/CPPS

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- GUPI

quality of life QOL Genitourinary Pain Index

- ICSI, ICPI

Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index and Problem Index

- PCA

Principal Components Analysis

- EFA

Exploratory Factor Analysis

- WLSMV

robust weighted least squares estimator

- SYMQ

Symptom and Health Care Utilization Questionnaire

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- SE

Standard Error

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Rackley RR, et al. Clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:177. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF, et al. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1996;87:321. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner JA, Hauge S, Von Korff M, et al. Primary Care And Urology Patients With The Male Pelvic Pain Syndrome: Symptoms And Quality Of Life. The Journal of Urology. 2002;167:1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ku JH, Kim SW, Paick J-S. Quality of life and psychological factors in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2005;66:693. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanno P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome/bladder pain syndrome: Taking stock, looking ahead: ICI-RS 2011. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2012;31:375. doi: 10.1002/nau.22202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontari M, Giusto L. New developments in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Current Opinion in Urology. 2013;23:565. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283656a55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheong Ying C, Smotra G, Williams Amanda CdC. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landis JR, Williams DA, Lucia MS, et al. The MAPP research network: design, patient characterization and operations. BMC Urol. 2014;14:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Kusek JW, et al. The MAPP research network: a novel study of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. BMC Urol. 2014;14:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009;74:983. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49:58. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey L, Arbuckle R, Moldwin R, et al. The bladder pain/interstitial cystitis symptom score: development, validation, and identification of a cut score. Eur Urol. 2012;61:271. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabin C, O'Leary A, Neighbors C, et al. Pain and depression experienced by women with interstitial cystitis. Women Health. 2000;31:67. doi: 10.1300/j013v31n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothrock N, Lutgendorf SK, Kreder KJ. Coping strategies in patients with interstitial cystitis: relationships with quality of life and depression. J Urol. 2003;169:233. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein HB, Safaeian P, Garrod K, et al. Depression, abuse and its relationship to interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1683. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clemens JQ, Brown SO, Calhoun EA. Mental Health Diagnoses in Patients With Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome and Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Case/Control Study. The Journal of Urology. 180:1378. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riegel B, Bruenahl CA, Ahyai S, et al. Assessing psychological factors, social aspects and psychiatric co-morbidity associated with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS) in men -- a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:333. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA, et al. The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology male study. J Urol. 2013;189:141. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52:69. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1983. p. xvii.p. 425. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User's Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horn JL. A Rationale and Test for the Number of Factors in Factor-Analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer's MAP test. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers. 2000;32:396. doi: 10.3758/bf03200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, et al. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, New Jersey, USA: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thissen D, Wainer H. Test scoring. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2001. p. xii.p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vrijens D, Drossaerts J, van Koeveringe G, et al. Affective symptoms and the overactive bladder - a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, et al. Comorbidities and personal burden of urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:1015. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coyne KS, Barsdorf AI, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:448. doi: 10.1002/nau.21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.