Abstract

Nano-bioelectronics represents a rapidly expanding interdisciplinary field that combines nanomaterials with biology and electronics, and in so doing, offers the potentials to overcome existing challenges in bioelectronics. In particular, shrinking electronic transducer dimensions to the nanoscale and making their properties appear more biological can yield significant improvements in the sensitivity and biocompatibility, and thereby open up opportunities in fundamental biology and healthcare. This review emphasizes recent advances in nano-bioelectronics enabled with semiconductor nanostructures, including silicon nanowires (SiNWs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene. First, the synthesis and electrical properties of these nanomaterials are discussed in the context of bioelectronics. Second, affinity-based nano-bioelectronic sensors for highly sensitive analysis of biomolecules are reviewed. In these studies, semiconductor nanostructures as transistor-based biosensors are discussed from fundamental device behavior through sensing applications and future challenges. Third, the complex interface between nanoelectronics and living biological systems, from single cells to live animals are reviewed. This discussion focuses on representative advances in electrophysiology enabled using semiconductor nanostructures and their nanoelectronic devices for cellular measurements through emerging work where arrays of nanoelectronic devices are incorporated within three-dimensional cell networks that define synthetic and natural tissues. Last, some challenges and exciting future opportunities are discussed.

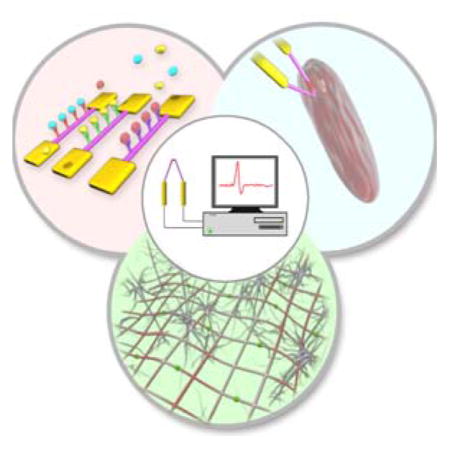

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Bioelectronics can be broadly defined as the merger of electronics with biological systems, where a bioelectronic device transduces signals from the biological system to electrical signals at the bio-electronic interface. The development of bioelectronics has resulted in vital biomedical devices, such as blood glucose sensors,1–3 cardiac pacemakers, and deep-brain stimulators.4–5 Despite the success of these devices, it should be recognized that the electronic transducers have had substantial size mismatch with the biological systems to which the electronics were interfaced. Hence, substantially shrinking the electronic transducer dimensions and making their properties appear more biological could lead to significant improvements in the sensitivity and biocompatibility of next generation bioelectronics, and thereby enhance and/or open up new opportunities in fundamental biology and healthcare areas.6–7

In this regard, a variety of nanomaterials, including zero-dimensional (0D) nanoparticles, one-dimensional (1D) nanotubes and nanowires, and two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets, have emerged over the past several decades, with substantial progress made on their chemical synthesis, processing, and characterization.8–12 One motivation underlying these efforts has been to elucidate how the size, structure and composition, for example, of such nanostructures lead to novel electronic, optical and magnetic properties, including quantum confinement regime in one or more dimensions. The enhanced and even unprecedented physical properties of such nanomaterials offer potentially unique opportunities in biology.

In particular, nano-bioelectronics represents a rapidly expanding interdisciplinary field that combines nanomaterials and nanoscience with biology and electronics, and in so doing, offers the potentials to overcome existing challenges in bioelectronics and open up new frontiers. For example, an affinity-based biosensor, such as a protein or DNA sensor, utilizes a surface-immobilized recognition probe to selectively interact with the biological analyte in solution and yields a electrical signal directly proportional to analyte concentration.13–16 In addition, bioelectronic devices interfaced to electrogenic cells, such as neurons or cardiomyocytes, can record and/or stimulate bioelectrical acitivities in the cells or corresponding tissues (e.g., brain, heart or muscle), by interconverting ionic and electronic currents at the device/cell interface.17–20

The central element in a nano-bioelectronic device is the nanostructure that is used to sensitively record or stimulate a biological event of interest. The potential of nanostructures in biology lies inherently in their small sizes and high surface-to-volume ratios. First, their high surface-to-volume ratio offers high sensitivity to surface processes. Only a small number of analyte molecules are needed to produce a measureable electrical signal, which allows both a reduction of sample volumes and the miniaturization of biosensors. In addition, the size scale of nanostructures can be comparable to biological building blocks, such as proteins and nucleic acids, offering new ways to perturb living systems from subcellular to tissue levels. The similar size scale of nanostructures and biological building blocks can also facilitate seamless integration of nanoelectronics with cells and tissues, and enables unique opportunities in synthetic tissues and biomedical prosthetics.21–24

This review is organized to emphasize recent advances in nano-bioelectronics enabled with semiconductor nanostructructures, including silicon nanowires (SiNWs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene. We will briefly discuss the relevant synthesis and electrical properties of these nanomaterials in the context of bioelectronics in Section 2. Section 3 discusses affinity-based nanobiosensors for highly sensitive analysis of biomolecules. In these studies, semiconductor nanostructures have been utilized as the central element of transistor-based biosensors. Sections 4 and 5 describe the complex interface between nanoelectronics and biological systems, from single cell to in vivo live animal levels. Our discussion will be focused on several representative conceptual advances in electrophysiology enabled by using semiconductor nanostructures and their nanoelectronic devices, rather than trying to comprehensively cover all the work performed in this vibrant field.

2. NANOSTRUCTURE BUILDING BLOCKS AND NANOTRANSISTORS

Nanostructure building blocks can be synthesized via the bottom-up paradigm, in a manner that mimics how complex biological systems are constructed by proteins and other biological building blocks in nature. Central to the bottom-up approach is the synthesis of building blocks with controlled structure, size and morphologies, as these characteristics determine their chemical and physical properties.8–10,12,25 Bioelectronic devices based on these building blocks can be rationally designed to exploit the unique properties of different nanomaterials with the goal of providing unique capabilities of interfacing to and studying different biological systems. Thus, we will provide a brief introduction to the structure, preparation and electrical properties of three representative semiconductor nanomaterials being used in bioelectronic devices: silicon nanowires, carbon nanotubes and graphene. We refer the interested reader to more comprehensive reviews focused on the synthesis and properties of semiconductor nanowires,8–9,26–28 nanotubes25,29–33 and graphene.34–38

2.1. Silicon Nanowires

We will focus on SiNWs as a representative example of semiconducting NWs for bioelectronics since key nanostructure properties, including morphology, size, composition and doping, have been widely explored and can now be precisely controlled during synthesis.26–28 Silicon and other NWs also can be well-aligned into highly ordered arrays,39–44 which are important for the construction of arrays of bioelectronic devices and integrated circuits. Also, the diameter of NWs can be readily reduced to a few nanometers,45 and the crystalline structure and smooth surface of chemically synthesized NWs reduce scattering and result in enhanced electrical properties.46 Thus, semiconductor NWs represent a logical pathway to scaling of semiconductor devices for potentially novel bioelectronic devices.

2.1.1. Basic Structures and Preparation

The basic SiNW has a uniform composition, 1D structure with diameter typically in the range between 3–500 nm, and length ranging from several hundreds of nanometers to millimeters.47 The two paradigms for realizing SiNWs can be categorized as top-down and bottom-up.26,28,48–53 The top down paradigm, often based on lithography, deposition and etching steps, offers convenient processing of a uniform macroscopic section of material, such as a Si wafer, into different pre-defined structures with nanoscale dimensions. The bottom-up paradigm, on the other hand, is based on synthesizing target architectures from individual atoms and molecules, with key nanometer-scale metrics built-in through synthesis and/or subsequent assembly, thus enabling the potential to go beyond the limits of top-down technologies. The bottom-up approach can lead to entirely new device concepts and functional systems,54 and thereby create technologies that people have not yet imagined. The bottom-up synthesis of SiNWs has been primarily achieved by vapor phase growth.51,55–67 Among these, the nanoparticle-catalyzed vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) mechanism8 is the most widely used because of its simplicity and versatility.

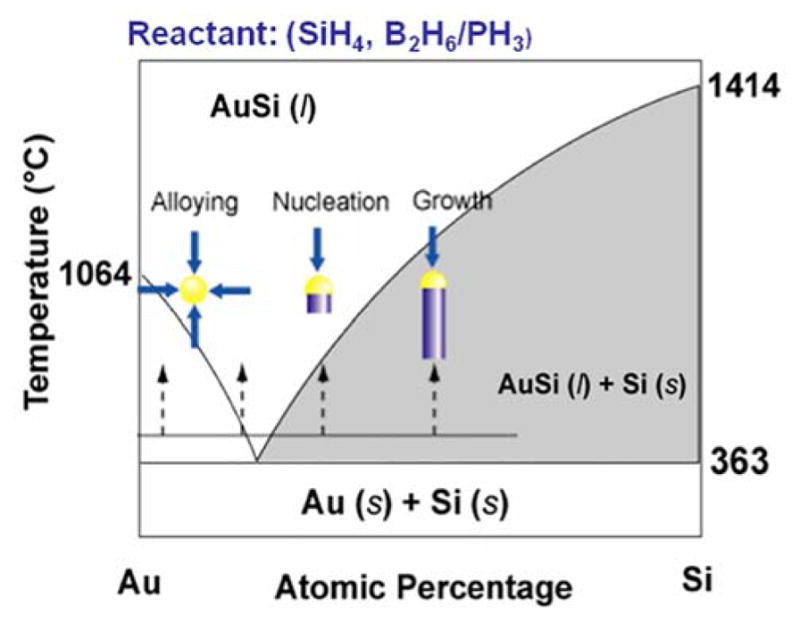

In 1964, Wagner68 introduced the VLS growth of silicon structures, where the VLS mechanism underpins most of the bottom-up synthetic studies of SiNWs. It is important to recognize, however, that this early work yielded only microscopic Si whiskers or wires. Truly nanoscopic SiNWs were not reported until 199769 and 1998,55–56 when research groups at Harvard University55,69 and Hong Kong City University56 reported nanoscale SiNWs. In the former work,55,69 laser ablation was used to generate nanoscale catalysts and simultaneously silicon or germanium reactant and thereby yield high-quality single crystalline silicon and germanium NWs by the now general and widely used nanocluster-catalyzed VLS growth approach. In the latter study,56 a distinct oxide catalyzed NW growth mechanism was proposed. These early demonstrations opened up substantial opportunities in this exciting field, and significant progress since has been achieved on length scales ranging from the atomic and up, in controlling the morphology, size, composition and doping of SiNWs.8–10,26–28

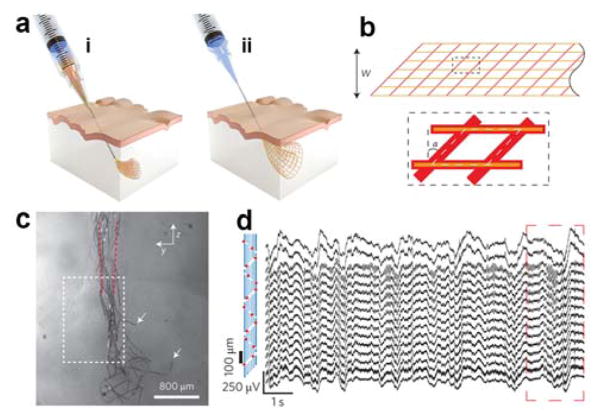

Key points in the VLS mechanism are illustrated in Figure 1, in which a nanometer scale catalyst is used to promote the material growth constrained along only one direction. In this mechanism, a metal catalyst, such as a gold (Au) nanoparticle, forms a liquid metal-semiconductor eutectic alloy at an elevated temperature by adsorbing the vapor reactant, such as silane (SiH4) or silane decomposition products. Continuous incorporation of the semiconductor material in the alloy through the vapor/liquid interface ultimately results in supersaturation of the semiconductor material. It then drives the precipitation of the semiconductor material at the liquid–solid interface to achieve minimum free energy. Accordingly, the 1D crystal growth begins via the transfer of the semiconductor material from the vapor reactant at the vapor/liquid interface into the eutectic, followed by atom (e.g., Si atoms) addition at the liquid/solid interface. In addition, because the gold nanoparticle remains at the tip of the NW during VLS growth, it can define the diameter of the 1D NW as long as all reactant addition is through the liquid/solid interface.

Figure 1.

VLS growth mechanism of SiNWs.

Following the initial laser ablation studies, the nanoparticle-catalyzed VLS process was expanded to exploit more controlled reactant sources such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD).57,70 In this modification, a volatile gaseous precursor, such as SiH4 or SiCl4, was used as the silicon source for the growth of SiNWs. The gaseous precursor is transported by a carrier gas, typically Ar or H2, to the surface of the metal catalyst, where the precursor reacts and is decomposed. Because of the excellent control over many aspects of the synthesis process, CVD-VLS growth has become arguably the most powerful option for NW synthesis.

During VLS growth, SiNWs are formed in near-equilibrium condition, and the growth processes can thus be considered primarily thermodynamically driven. As a result, the preferred growth direction is the one that minimizes the total free energy. Wu et al.45 and Schmidt et al.71 found that the growth directions of intrinsic SiNWs can be influenced by the diameter of the NWs. The larger intrinsic SiNWs with diameters above 20 nm exhibit a dominant <111> growth direction, whereas NWs with smaller diameters (3–10 nm) tend to grow along the <110> direction, and <112> NWs are obtained in the transition region. These results can be understood by the increasing contribution of the silicon/vacuum surface energy to the total free energy in smaller NWs. In addition, system pressure during growth and doping level can play an important role in determining NW growth orientations,27,72–73 and represents an area for further study in the future.

2.1.2. Advanced Morphologies and Structures

An important feature of the bottom-up growth paradigm is the capability for tunable synthesis of new materials and architectures on many length scales. In this regard, 1D semiconductor NWs represent one of the most powerful platforms for rational designed and synthetic realization of complex nanostructure building blocks or systems with predictable physical and chemical properties. In addition, assembly of distinct functional SiNW building blocks can enable exploration and applications of multi-component devices and integrated systems. To date, five general structural classes have been demonstrated: homogeneous NWs, axial modulated structures, radial/coaxial modulated structures, branched/tree-like NWs, and kinked structures (Figure 2).74–120 As discussed below, several of these modulated nanowire structures, which have not been achieved in carbon-based materials, offer unique advantages for creating nano-bioelectronic interfaces.

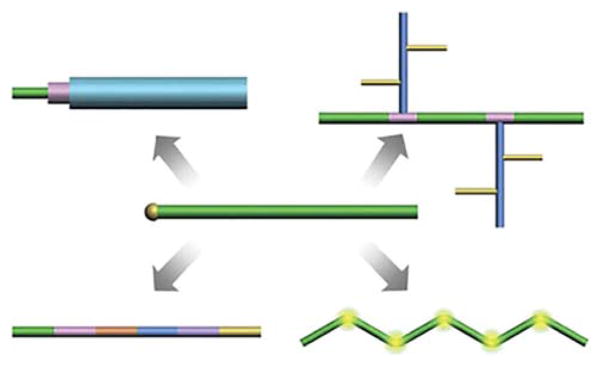

Figure 2.

Five classes of NW structures available today: basic (center), axial, core/shell, branched and kinked structures, clockwise from lower left. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 6. Copyright 2011 Materials Research Society.

Axial NW heterostructures.74–75 The controlled synthesis of axial NW superlattices was reported in 2002 by three research groups, representing a significant step in the controlled synthesis of NW heterostructures.76–79 As an example, Gudiksen et al. successfully synthesized GaAs/GaP, n-Si/p-Si, and n-InP/p-InP axial NW heterostructures.79 The prerequisite for the synthesis of axial NW heterostructures is the continuation of the NW elongation when different vapor phase reactants are introduced, and thus the metal catalyst should be able to promote reactions with all of these reactants under similar growth conditions. This seminal work on axial-modulated NWs was subsequently expanded with the synthesis of metal-semiconductor junctions,80–81 doping-modulated NWs,82–83 as well as NWs with ultra-short morphology features84–85. In a recent work, the Tian group showed that pressure-dependent formation of etchant-resistant patterns within SiNWs by iterated deposition-diffusion-incorporation of gold (originated from the nanoparticle catalyst) to yield mesostructured SiNWs post-etching.86

Radial NW heterostructures. Radial core/shell NW structures can be achieved by the deposition of the shell on the surface of the 1D NW core. One of the first reports of core-shell NW heterostructures by Lauhon et al. used a CVD approach to grow homo- and heterostructures from Si and Ge, with different dopant concentrations, including i-Si/p-Si, Si/Ge and Ge/Si core-shell NWs.87 Later, the Lieber group reported CVD growth of (InGaN/GaN)n quantum wells,88–89 regioselective NW shell synthesis in studies of Ge and Si growth on faceted SiNW surfaces,90 and facet-selective growth of CdS on SiNWs.91 Recently, Plateau–Rayleigh crystal growth of periodic shells on NWs has been demonstrated with tunable morphological features, such as diameter-modulation periodicity and amplitude and cross sectional anisotropy.92

Branched NW heterostructures.93 A third basic motif involves the synthesis of branched or tree-like NWs. The higher degree of complexity in such structures increases the potential for NW applications, by increasing the number of connection points and by providing a means for parallel connectivity and interconnection of functional elements. Several methods have been reported for the synthesis of branched structures, ranging from sequential catalyst-assisted growth,94–102 solution growth on existing NWs,103–106 phase transition induced branching,107–110 one-step self-catalytic growth111–114 and screw dislocation driven growth.115–118 As an example, Jiang et al. reported the synthesis of branched NW structures, including group IV, III–V and II–VI, with metal branches selectively grown on core or core-shell NW backbones.101 As the branched NWs are obtained by dispersion of catalysts on the backbone and reintroduction of the growth precursors for a second growth stage, each generation of NW branches can have a unique diameter and composition.

Kinked NW structures. The VLS growth mechanism can be further extended to the stereo-controlled synthesis of kinked NWs. Tian et al. showed that kinks can be created by introducing a perturbation, such as purging and reintroducing reactants, during the normal NW growth.73 The kinks consist of two straight single-crystalline arms connected by one fixed 120° joint in a SiNW. In addition, nanoscale axial p–n junctions can be synthetically introduced at the joints of kinked SiNWs.119 The stereochemistry of adjacent kinks can be controlled,54,120 which allows the synthesis of increasingly complex 2D and 3D structures with unique capabilities for bioelectronics.

The design and rational synthesis of the complex NWs described above renders them unique building blocks for controlling nano-bio interfaces. For example, kinked NW structures, which will be discussed further below, can improve cell/device junction tightness, and with phospholipid bilayer coatings, these nanoscale transistors can function as point-like, mechanically non-invasive probes capable of entering cells without the need for direct exchange of solution (as occurs with micropipettes).54 In addition, recent studies of mesostructured SiNWs can enhance bio-nano interface,86 and thus could contribute to nano-bioelectronic devices in the future as well.

2.1.3. Large-Scale Assembly of Nanowires

NWs synthesized by bottom-up approaches often have random alignment and orientations, and thus cannot be used ‘as is’ for fabrication of ordered device arrays. To fulfill the potential of NWs as building blocks for such applications requires effective assembly and integration techniques that transfer NWs from growth substrates onto the device substrates with control of alignment and position.39–44 Reported methods include flow-assisted alignment,121–126 Langmuir–Blodgett technique,127–135 blown bubble method,136–137 chemical binding/electrostatic interactions,138–143 interface-induced assembly,144–145 electric/magnetic field-assisted alignment,146–154 PDMS transfer,155–159 contact/roll printing techniques,160–166 nanocombing,167 as well as other assembly methods.168–172

As an early example, Huang et al. designed a flow-assisted technique by combining fluidic alignment with surface-patterning, whereby the separation and spatial location of NW arrays are readily controlled.122 In this method, NWs are aligned by passing a suspension of NWs through microfluidic channel structures formed between a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold and a flat substrate, pre-functionalized to enhance the interaction with NWs (Figure 3a, b). Alternating the flow in orthogonal directions in a two-step assembly process yielded crossbar structures (Figure 3c), while equilateral triangles were assembled in a three-layer deposition sequence using 60° angles between the three flow directions (Figure 3d). In 2007, Javey et al. developed a contact printing method to directly transfer NWs from a growth substrate to a second device substrate.160 As illustrated in Figure 3e, the NW growth substrate is placed upside down on top of a lithographically patterned substrate, and translated horizontally for several millimeters under normal load to transfer the as grown NWs onto the underlying substrate with an orientation parallel to the sliding direction. This NW transfer process can be repeated multiple times, along with the deposition of a thin SiO2 insulating layer between adjacent NW layers to yield 3D stacked arrays (Figure 3f).

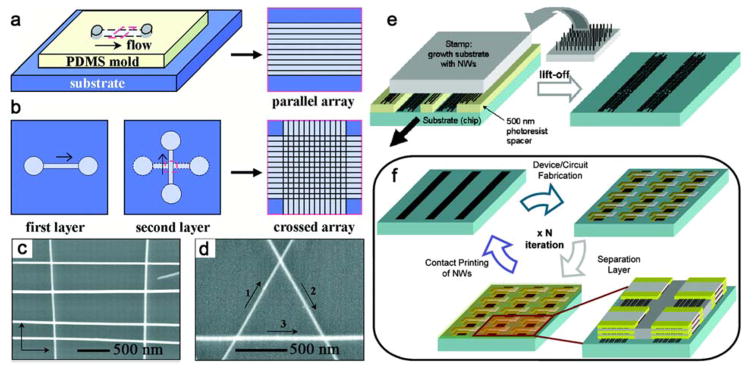

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic for flow-assisted alignment of parallel NW arrays. (b, c) Schematic and SEM images of crossed NW matrix obtained by changing the flow direction sequentially. (d) A triangle of NWs obtained in a three-step assembly process. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 122. Copyright 2001 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (e) Contact printing of NWs. (f) 3D NW circuit fabricated by multiple contact printing steps. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 160. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

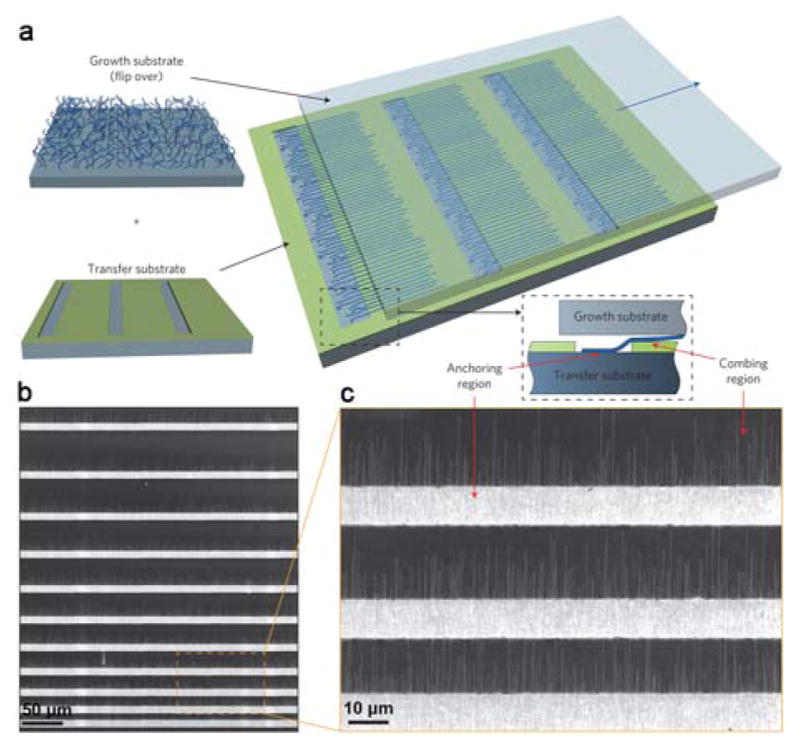

In 2013, a dry-transfer approach based on an innovative nanoscale “combing” technique was developed.167 A small anchoring region is opened in the accepting substrate where the tips of the NWs attach due to strong attractive forces. This anchoring allows subsequent substrate translation to comb the NWs over the polymer-protected region of the device substrates. Significantly, large-area arrays of parallel NWs with <1 degree misalignment and with >98.5% yield are produced. This order of magnitude improvement in alignment has enabled fabrication and demonstration of the largest integrated NW circuit by the bottom-up approach (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Schematics of the nanocombing process. (b, c) SEM images of SiNWs on the combing surface. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 167. Copyright 2013 Nature Publishing Group.

These approaches show clearly the capability of realizing post-growth bottom-up assembly of distinct NW materials into single- and multi-layer arrays of NW-based nanoelectronic devices, which are especially important for enabling multiplexed measurements at cell/tissue levels with subcellular resolution.21–24,173–174 For example and as will be discussed in more detail below, arrays of NW FET devices fabricated on substrates have been used for high-resolution recording from acute brain slices,173 while arrays incorporated into free-standing macroporous mesh-like structures have opened completed new areas of tissue engineering, where the nanoelectronic mesh serves as a scaffold to electronically-innervate synthetic tissue in 3D,21–22 as well as novel injectable nanoelectronics capable of in-vivo brain mapping.23–24,174

2.1.4. Nanowire Field-Effect Transistors

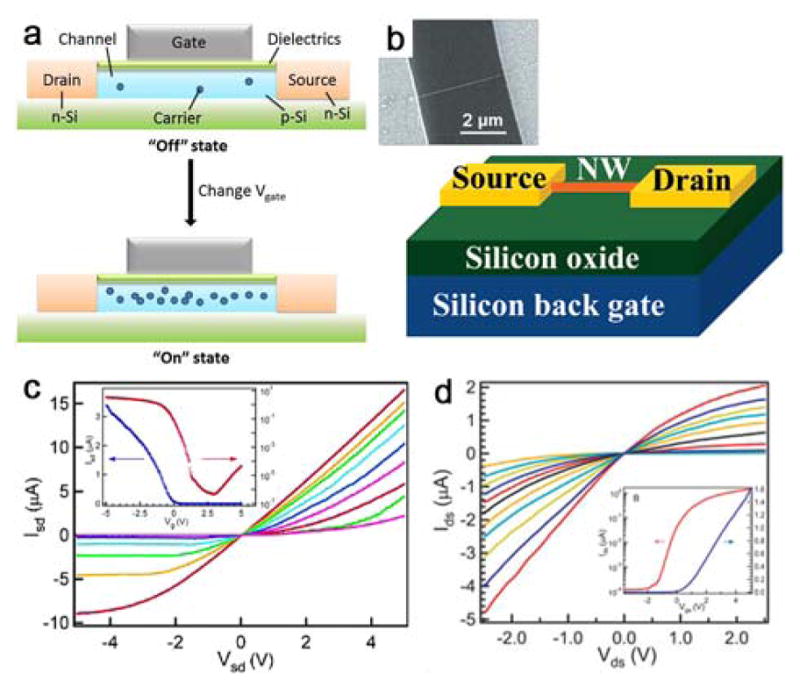

The field-effect transistor (FET) is a fundamental building block of high-density integrated circuits. In a standard planar FET (Figure 5a), the semiconductor substrate (e.g., p-Si) is connected to the gate (G), the source (S) and the drain (D) electrodes. The source and drain regions, through which current is injected and collected, respectively, have an opposite doping (e.g., n-type) to the substrate. The gate electrode is capacitively coupled to the semiconductor channel by an insulating oxide layer. If no gate voltage (Vg) is applied (the “Off” state), the FET is equivalent to two p-n junctions connected back-to-back with almost no current flows. In the “On” state, when Vg exceeds a threshold voltage, charge carriers (e.g., holes for p-Si and electrons for n-Si) are induced at the semiconductor-oxide interface, and the potential barrier of the channel drops, resulting in a significant tunneling current flow. Therefore, the conductance of the semiconductor channel between the source and drain regions can be switched from Off to On and modulated in the On-state by the potential at the gate electrode.

Figure 5.

(a) A typical planar FET. The semiconductor substrate (e.g., p-Si) is connected to gate (G), source (S) and drain (D) electrodes, and can be switches between the “off” and “on” states by applying the Vg. (b) Schematic and SEM image of a NW-FET. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 175. Copyright 2002 American Chemical Society. (c, d) Transistor characteristics of p- and n-type NWs. Insets show transfer characteristics of the back-gated devices. (c) Reprinted with permission from Ref. 135. Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society. (d) Reprinted with permission from Ref. 179. Copyright 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Similar to its planar counterpart, the basic electronic properties of a semiconductor NW can be characterized using electrical transport studies in a FET (NW-FET) configuration (Figure 5b).175 For example, NWs can be deposited on the surface of a silicon wafer covered with an oxidized layer (Si/SiO2), in which the underlying conducting silicon can serve as a global back gate. The naturally grown oxide layer on SiNWs can be used as the gate oxide. Source and drain electrodes are defined by lithography followed by evaporation of metal contacts. The electrostatic potential of the NWs is tuned by Vg, which modulates the carrier concentration and conductance of the NW. Comprehensive reviews focused on NW-FETs can be consulted for further details.46,176

In the case of NWs with homogeneous structure and composition, SiNWs have been extensively studied, due to the dominance of silicon in the semiconductor industry. Nonetheless, the initial transport studies of SiNWs were far from optimal, due to the large sample-to-sample variation and low carrier mobility. Improved control during synthesis, including the NW diameter down to sub-20 nm, fine-tuned doping level and electrical properties, has contributed to important advances and NW devices approaching 1D quantum confinement that are desirable for high-performance FETs55, such as p- and n-channel Si NW-FETs.135,177–179 Still, these NW FETs are Schottky barrier devices and their performances are affected by the metal contact (S and D), unlike conventional metal-oxide-semiconductor FET (MOSFETs) with degenerately doped semiconductor source/drain contacts. Annealing is a general method to effectively form ohmic contacts and increase the on-current.

Parallel integration of p-SiNW devices was subsequently demonstrated by combination of Langmuir-Blodgett (LB) assembly and photolithography techniques.135 From the electrical characterization of randomly chosen NW devices within large arrays (Figure 5c), both linear source-drain current (Isd) versus source-drain voltage (Vsd) curves and saturation at larger negative voltages were obtained, as expected for p-type FETs. Furthermore, Zheng et al. demonstrated the first example of controlled growth of n-type SiNWs with tunable phosphorus doping, and fabrication of high-performance n-type NW-FETs.179 The Ids-Vds curves recorded with gate voltage (Vgs) from −5 to 5 V are linear from small values of Vds and saturated at Vds ~2 V, and show increases (decreases) in conductance as Vgs becomes more positive (negative), as expected for an n-channel FET (Figure 5d). Ohmic-like contacts with lower source contact resistance (Rs) were obtained with heavily-doped NWs, while the nonohmic contacts with higher Rs were observed for lightly-doped NWs, where the dopant concentration dependent Rs limits the measured transconductance.

Koo et al. also reported the fabrication of dual-gated Si NW-FETs, having both a top metal gate and a backside substrate gate.180 A conducting channel of either accumulated holes or inversion electrons is formed by the back gate, which also controls the shape of Schottky barrier between the channel and the source/drain electrodes. The top gate then can control ambipolar conduction (either hole or electron conduction occurs depending on the gate bias) in these SiNW-FETs. Enhanced channel conductance modulation could be achieved with these dual-gated SiNW devices.

In addition to homogeneous NWs, axial heterostructures,80,181 radial heterostructures182–185 and crossed-NW structures157,160,186–188 have also been developed to extend the versatility of NW-FETs. For example, Colinge et al. reported junctionless NW-FETs, in which the current flows through the bulk of the channel, rather than just along its surface.189 Compared to classical transistors, these NW devices exhibit low leakage currents, near-ideal subthreshold slope, and less mobility degradation with gate voltage and temperature.

2.2.Carbon Nanotubes

CNTs have large aspect ratios, high mechanical strength, excellent chemical and thermal stability, and rich electronic and optical properties.29–30,190–192 Applications of CNTs span many fields, including composite materials, nanoelectronics, and energy storage.193–198 In recent years, efforts have also been devoted to exploring the potential biological applications of CNTs.199–202

2.2.1. Structures, Preparation and Assembly

CNTs are rolled up seamless cylinders of graphene sheets. CNTs are classed as single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs) or multiwalled nanotubes (MWNTs), depending on the number of their concentric walls.190,203 The diameters of SWNTs and MWNTs are typically 0.4–2 and 2–100 nm, respectively, and their lengths range from hundreds of nanometers to centimeters. The chirality of SWNTs, which is the angle the graphene sheets roll up with respect to lattice vectors, determines their electronic properties.190 The chiral vector (n, m) is used to quantify this rolling up angle, where n and m are the integer numbers of hexagons traversed in the two unit-vector directions of the graphene lattice. This vector can be directly related to the electronic properties of SWNTs. Specifically, a SWNT will be metallic if (n-m) is a multiple of 3 and a semiconductor otherwise. Statistically, 1/3 are metallic and 2/3 are semiconducting.204 For FETs, semiconducting SWNTs are required.

A number of techniques have been used to produce CNTs,205–208 including high temperature arc-discharge, laser ablation and solar beam-induced vaporization,209–215 and low temperature216–224 methods such as CVD. The first reported SWNTs were prepared using a carbon arc-discharge method with metal catalyst mixed in one of the carbon electrodes.210 Despite its simplicity, this method is capable of producing structurally pristine SWNTs with a relatively high yield. CVD was first used to grow CNTs in 1993 by incorporating nanoparticles on substrates with hydrocarbon gas as the reactant.216 Substantial efforts have been placed on CVD synthesis of CNTs, and it is now undoubtedly the preferred method for synthesizing SWNTs of highest structural quality and has been extensively reviewed.31–33

One big challenge for directly using SWNTs for FET devices is that the as-synthesized SWNTs are always a mixture of semiconducting (s-) and metallic (m-) tubes, while the latter m-SWNTs degrade performance of the devices. Methods to overcome this challenge, including growth control and post-growth separation, have been explored.225–226 In growth-based separation of SWNTs, introducing a weak oxidative gas227–230 or applying an external field231–232 have been reported. For example, Ding et al. demonstrated the growth of SWNT arrays on quartz substrate using ethanol/methanol mixture as the carbon source, and reported > 95% of the nanotubes were semiconducting.227 The authors found that this selective growth is achieved due to the presence of methanol and a strong affinity between nanotubes and the quartz substrate. In addition, a number of post-growth separation methods of s-/m- SWNTs, including electrical breakdown,233–234 gas etching,235–237 electromagnetic radiation,238–240 interaction with other molecules35,241 and centrifugation242 have been studied.

Ultimately, control of diameter and chirality of SWNTs is needed to a piori determine electronic properties as is possible with NWs. Reported strategies to control chirality have included growth rate dependence,243–244 catalyst and gas interactions,245–248 and cap engineering.249–253 Recently, the Li group used tungsten-based bimetallic alloy nanoparticles of non-cubic symmetry as the catalysts for CNT growth with reported control of diameter and chirality.248 The tungsten-based catalysts have high melting points and are able to maintain their crystal structure during the CVD process, and consequently regulate the chirality and diameter of the as grown SWNTs (Figure 6a). Specifically, they found semiconducting (12, 6) SWNTs were synthesized at an abundance of >92% (Figure 6b, c). Experimental evidence and theoretical simulations reveal that the good structural match between the carbon atom arrangement around the nanotube circumference and the arrangement of the atoms in one of the planes of the nanocrystal catalyst facilitates the (n, m) preferential growth of SWNTs. Alternatively, Sanchez-Valencia et al. used surface-catalyzed cyclodehydrogenation to convert a molecular precursor into ultrashort, singly capped (6, 6) ‘armchair’ nanotube seeds on a platinum (111) surface. Single-chirality and essentially defect-free SWNTs were then synthesized by elongation of these seeds, achieving lengths up to a few hundred nanometers (Figure 6d).253 The ability to directly produce large amounts of nearly identical SWNTs opens new opportunities for CNTs in integrated electronics.

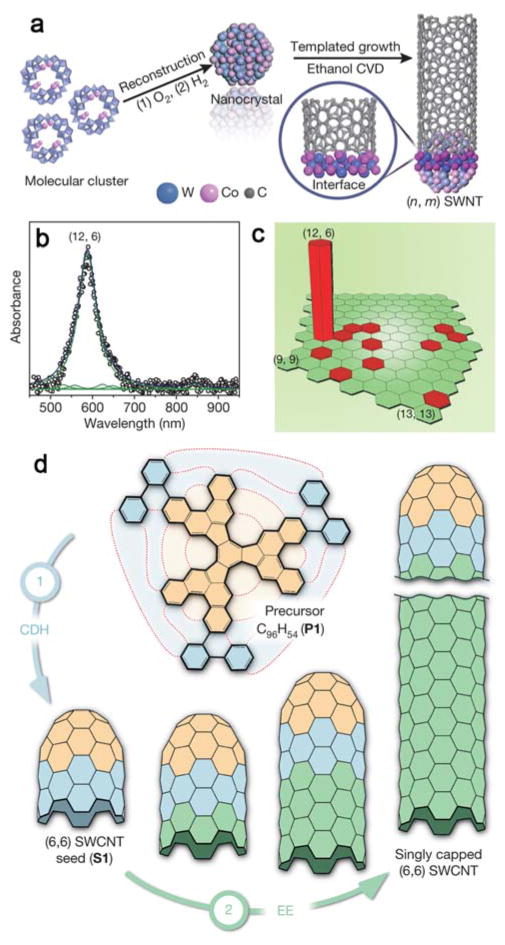

Figure 6.

Schemes for synthesis of SWNTs with single chirality. (a) Preparation of the W–Co catalyst and the growth of a SWNT. (b) UV–Vis–NIR spectrum from 42 samples. (c) Relative abundances of various chiralities from ~3,300 nanotubes. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 248. Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group. (d) Formation of singly capped ultrashort (6,6) seed and subsequent elongation of SWNT. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 253. Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group.

As 1D nanostructures, CNTs, similar to SiNWs, also need to be assembled for many applications. Two major strategies for producing CNT arrays include post-synthesis assembly254–255 and the aligned growth.206,256–258 Post synthesis assembly approaches, which are similar to the assembly methods for SiNWs, include flow directed alignment,259–265 Langmuir–Blodgett assembly,266–267 electric field268–270 and magnetic field271–274 directed alignment, mechanical shearing,275–280 or blown bubble film techniques.136,281 On the other hand, in situ growth approach produces aligned CNTs during growth using controlled CVD processes, including gas flow directed growth,282–290 external field directed growth,232,291–292, and surface-directed growth.25,293–297 These in situ aligned growth methods have the advantage of avoiding defects induced during post-assembly, and can be combined with the standard fabrication of silicon-based devices.

2.2.2. Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistors

Semiconducting SWNTs can be used as the channel material for FETs, as first demonstrated by the Dekker group.298 Many research groups have demonstrated the potential of SWNTs as building blocks in applications such as displays, flexible electronics, and printable electronics.255,257 Due to their 1D transport and long mean free path, SWNTs can enable ballistic transport in short channel devices.299 It has been shown that SWNTs can have high mobility and current carrying capacity.300–301 Due to oxygen doping in air, semiconducting SWNTs show p-type behavior. Several approaches have been reported to convert them to n-type, including chemical doping,302–306 annealing303,307 and metal contact engineering.308–310 It has been found that the performance of a SWNT FET depends dramatically on the work functions of the contact metals,298–299,311–314 and the interface between SWNTs and metal contacts depends sensitively on the fabrication quality during contact evaporation and annealing.

Although individual SWNTs can possess very good electronic properties, it has been difficult to integrate these building blocks into large-scale electronics, due in part to their low current output per nanotube, small active areas, and the aforementioned heterogeneous mixtures of metallic and semiconducting as-synthesized tubes. This heterogeneity in electronic properties is one major difference between SWNTs and SiNWs, where the mixture of s-/m- SWNTs will yield device-to-device performance variations.

2.3.Graphene

Graphene is defined as a single 2D layer of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms joined by covalent bonds to form a flat hexagonal lattice with excellent electrical and mechanical properties. Below we will provide a brief summary of the preparation of graphene and graphene device properties; readers are referred to reviews of graphene synthesis and properties of graphene FETs for more detailed information.34,36–38,315–317

2.3.1. Exfoliation of Graphite

Graphite consists of many sheets of graphene stacked together. In a single graphene sheet, carbon atoms are linked by covalent bonds, while adjacent graphene sheets interact by much weaker van der Waals bonds. Therefore, single graphene sheets can be obtained by exfoliating graphite. Reported exfoliation methods include mechanical, liquid, and oxidation/reduction processes.

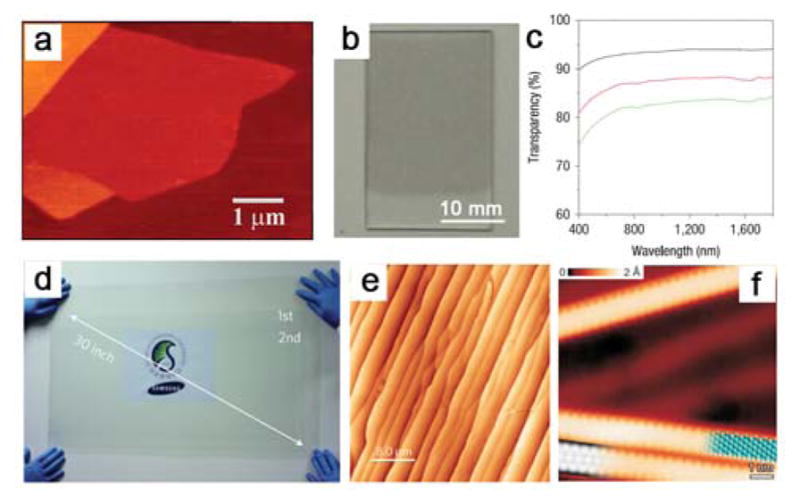

The experimental isolation of single-layer graphene was firstly demonstrated by Geim and coworkers at Manchester University318 (Figure 7a). They used mechanical exfoliation technique (i.e., peeling with adhesive tape) to isolate graphene from graphite, and obtained single- and few-layer flakes pinned to the receiver substrate, by van der Waals forces. Graphene flakes prepared by mechanical exfoliation have high crystal quality and can be more than 100 μm2 in size. The pristine graphene prepared by mechanical exfoliation exhibits remarkably high carrier mobility, room temperature Hall effect, and ambipolar field-effect characteristics.319–321 The high carrier mobility and ambipolar device characteristics are valuable for bioelectronics. However, mechanical exfoliation is of low throughput and not able to produce large graphene sheets. These drawbacks have limited the use of mechanically exfoliated graphene to primarily single device studies.

Figure 7.

(a) Mechanically exfoliated single-layer graphene sheet. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 318. Copyright 2004 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (b) Liquid-phase exfoliated two-layer graphene LB film on quartz. (c) Transparency spectra of one- (black), two- (red) and three-layer (green) LB films. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 333. Copyright 2008 Nature Publishing Group. (d) Large-area graphene grown by CVD on copper substrate spanning 30 inches diagonally. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 365. Copyright 2010 Nature Publishing Group. (e) AFM image of epitaxial graphene grown on SiC. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 370. Copyright 2009 Nature Publishing Group. (f) STM image of synthesized graphene nanoribbons. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 373. Copyright 2010 Nature Publishing Group.

Another exfoliation process is achieved in liquid assisted by ultrasonication,322–323 as the solvent–graphene interaction is balanced by the inter-sheet attractive forces after exfoliation. Solvents with surface tension ~40 mJ m−2 are most suitable for graphene dispersion because they minimize the interfacial tension.324 For example, Hernandez et al. obtained graphene dispersions with concentrations up to ~0.01 mg mL−1 in organic solvents such as N-methyl-pyrrolidone (NMP). In the same year, Blake et al. achieved graphite exfoliation by sonication in dimethylformamide (DMF).325 Bourlinos et al. proposed perfluorinated aromatic solvents and tested their exfoliating performance.326 Qian et al. produced monolayer and bilayer graphene by a solvothermal-assisted exfoliation process in acetonitrile, and the yield reached 10 to 12 wt%.327 Small organic molecules and polymers can further promote the exfoliation of graphite, especially when they have a good adsorption on graphene sheets.328–337 For instance, Dai and coworkers inserted tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBA) into oleum-intercalated graphite and sonicated it in a DMF solution of 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethyleneglycol)-5000] (DSPE-mPEG) to form a homogeneous suspension.333 The resulted graphene sheets are made into conducting films by Langmuir–Blodgett assembly on transparent substrates. The one-, two- and three-layer films on quartz afforded transparencies of ~93, 88 and 83%, respectively (Figure 7b, c). The scalability of liquid-phase exfoliation can be used to deposit graphene on different substrates that are not applicable to mechanical cleavage. Nonetheless, the exfoliated ‘graphene’ obtained from sonication often has a large variety of flakes consisting of different number of layers, and the electronic properties of the graphene can also be affected by the surfactants and/or polymers used in the exfoliation processes.

A third and perhaps the oldest method involves oxidizing graphite to expand its graphitic layers, followed by exfoliation into single layers of graphene oxide (GO), and finally reduction to remove the oxygen groups. Three approaches have been used to oxidize graphite: the Brodie,338 Staudenmeier339 and Hummers340 methods. In 2010, Marcano et al. improved the Hummers method to obtain a larger fraction of hydrophilic oxidized graphene material.341 After oxidation, the van der Waals force between the layers is weakened, and the interlayer spacing increases from 0.34 nm in graphite to above 0.6 nm. As a result, single GO flakes can be isolated by ultrasonication. Many methods have been used to remove oxygen groups from the GO structure and restore the desired sp2 hybridized structure, such as chemical,342–346 thermal347–349 and electrochemical350–351 treatments. Nonetheless, the oxygen functional groups cannot be completely removed by these reduction procedures. Significantly, the residual oxygen functional groups and oxidation-created defects reduce or eliminate most of the unique electronic properties of pristine graphene in reduced GO materials.

2.3.2. Synthesis of Graphene

As an alternative to the top-down exfoliation processes is bottom-up CVD synthesis of graphene.352–354 The CVD method relies on the catalytic and carbon-saturated properties of the specific metals upon exposure to a hydrocarbon gas at high temperatures. At first, graphene grown by CVD was reported using Ni and Cu substrates,355–359 and subsequently this work was extended to other transition metal substrates.360–364 For example, heating a Ni substrate in the presence of hydrocarbon leads to decomposition and dissolution of the carbon in Ni. Because carbon atoms have very different solubility in Ni at high and low temperatures, as the substrate is cooled down, carbon atoms diffuse to the Ni surface and form graphene films. It is important to note that graphene grown on Ni is polycrystalline and usually consists of single- and few-to-multilayer regions. On the other hand, Cu allows higher quality single-layer graphene growth. This phenomenon is due to the fact that carbon has a relatively low solubility in Cu, and only a small percentage of carbon atoms are dissolved in the substrate. Single- or double-layered graphene is realized during the cooling process. Bae et al. demonstrated that the monolayer graphene films grown by CVD on Cu substrates can be as large as 30 inches (Figure 7d).365 For electronic applications of graphene, the catalytic metal substrate needs to be removed and the graphene transferred onto other substrates. One approach involves etching the metal substrate while the graphene is supported by an inert polymer such as poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) or PDMS, followed by transfer of the polymer/graphene onto the desired substrate.358,366 The physical properties of CVD grown graphene deviate to some extent from those of pristine graphene formed by mechanical exfoliation, due to lattice defects and impurities. Furthermore, the necessity of transferring the as-grown graphene film from the metal growth substrate to an insulating substrate for device fabrication further introduces additional defects, impurities, that can degrade the electrical and mechanical performances of the CVD graphene.

Another method to synthesize uniform, wafer-size graphene layers involves epitaxial growth on single-crystalline silicon carbide (SiC) substrates that are heated in vacuum to high temperatures. As Si sublimes faster than carbon from SiC, the excess carbon atoms remaining behind on the surface can rearrange to form graphene layers (Figure 7e).367–371 Nonetheless, the high cost of single crystal SiC wafers precludes large-scale growth of graphene using this approach. Last, coupling of polycyclic aromatic molecules on metal surface represents another route to produce nanoscale graphene (Figure 7f).372–375

2.3.3. Graphene Field-Effect Transistors

Theoretical predictions have long suggested extremely high carrier mobility in graphene due to the high quality of its 2D crystal lattice. In 2008, the Kim group measured a carrier mobility in excess of 200,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 in suspended graphene with minimized substrate-induced scattering.376 This high carrier mobility implies that charge transport is essentially ballistic on the micrometer scale even at room temperature. These results have generated significant interest in graphene as a possible material for the next-generation semiconductor devices.

Graphene FETs can exhibit an ambipolar field effect. Due to its ultrahigh mobility, graphene FETs respond quickly to variations of gate-source voltage. However, the absence of a bandgap yields a small On/Off ratio in graphene FETs, which has hindered applications of this material in semiconducting electronics. Several approaches have been proposed to overcome this limitation by creating a bandgap in graphene through (i) application of uniaxial strain,377–378 (ii) using bilayer graphene under an external field,379–382 and (iii) employing quantum-confined nanoribbons with well-defined edges.383–386

For the application of biosensing, three different structures of graphene FETs have been developed. (1) Back-gated graphene FETs, where the graphene film is transferred or deposited on a dielectric surface (typically a SiO2 layer) and source/drain electrodes are fabricated on the top. (2) Top-gated graphene FETs, where the gate dielectric is prepared on the graphene surface. This configuration has more flexibility in electronic applications but also suffers from lower carrier mobility because the top gate induces scattering. (3) Dual-gated graphene FETs, where a conducting substrate acts as the back gate, a metal as the top gate, and graphene as the conducting channel between source and drain.

3. NANOELECTRONIC BIOSENSORS

Next-generation biomedical diagnostics demand novel biosensors and assays that can fulfill the requirements of ultrasensitivity and high-throughput. Many semiconducting nanomaterials, such as NWs, SWNTs and graphene have been studied for the electronic sensing in an effort to address these needs. Due to their unique structural and chemical characteristics, including diameters similar to biomolecules, high surface-to-volume ratios and tailorable surfaces, these nanomaterials can be fabricated as high-performance FETs suitable for label-free, real-time, sensitive detection of proteins and other biomolecules.387

The electrical detection of biomolecules using a nanomaterial-based FET (nanoFET) can be understood as follows. The surface of a nanoFET is functionalized with biomolecule receptors, such as monoclonal antibodies or single-strand DNA (ssDNA) probes, which can selectively bind to biomolecule targets in solution. The binding of charged biomolecules, (the sign and quantities of the charges depend on the isoelectric point of the biomolecules and the solution pH), leads to a variation of charge or electric potential at the nanoFET surface, in a way similar to applying an external potential to gate electrode in a conventional FET device. The charge carrier densities of the nanoFET is thus tuned and leads to an electrical conductivity change associated with the biomolecular binding events in real time. Due to the similar diameter or thickness to most biomolecules (e.g. proteins and nucleic acids), these binding events can be sensitively detected by the nanoFETs. Furthermore, incorporation of a number of these nanoFETs in a single device array functionalized with different surface receptors can allow for multiplexed electrical detection in the same assay, enabling a unique and powerful platform for chemical/biological recognition.

In this section, we will introduce NW-, SWNT-, and graphene-based FET biosensors, with an emphasis on SiNWs, which represent the first nanoFET biosensors reported.388 Representative examples in which FET sensors are applied to detect chemical and biomolecule targets, including proteins, nucleic acids, and viruses, are summarized. Furthermore, methods for improving the sensitivity of nanoFET sensors are briefly illustrated.

3.1.Nanowire Biosensors

SiNWs have been extensively investigated for nanoelectronic sensing with great success. In 2001, Cui et al. reported the first demonstration of SiNW-based biosensors.388 Since then, SiNW FET biosensors have been explored for detection of a variety of biological species, including disease marker proteins,389–391 DNA mismatch identification,392–394 and single viruses.395 In addition, SiNW FETs have also been used to study small molecule-protein interactions,389,391,396 suggesting exciting potentials of drug screening, determination of reaction kinetics, and the inhibition of enzymatic activity. More importantly, the capability of integrating hundreds of SiNW FETs into a same device array, each electrically addressable, has been robustly demonstrated, as a milestone for the biosensing applications from laboratory to clinics.15,397–398

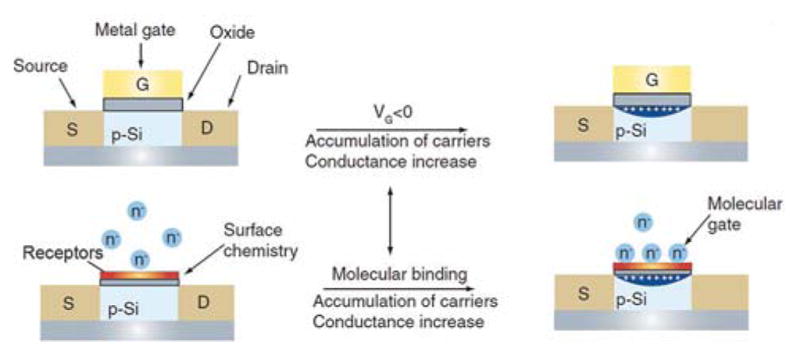

3.1.1. Functional principles of FET sensors

The use of planar FETs for ion–selective sensors was introduced several decades ago,399 while their opportunities as chemical and biological sensors have further been advanced in new and significant ways using nanomaterials. The scheme of planar FET has been discussed in Section 2.1.4. Here, we use NWs as an example to show the sensing mechanism of these nanoFETs. Similar to planar FETs, the conductance of a NW FET can be controlled by variations in the charge density or electric potential at the channel region, making FETs ideal candidates for chemical and biological sensing, as the electric field resulted from the binding of a charged molecule to the NW surface is analogous to applying a voltage via a gate electrode. In a p-type SiNW functionalized with surface receptors that can specifically capture chemical/biomolecule targets, binding of molecules with negative charges (similar to applying a negative gate voltage) leads to accumulation of charge carriers (holes) and a corresponding increase in conductance (Figure 8). However, binding of molecules with positive charges (similar to applying a positive gate voltage) will deplete holes and subsequently reduce the conductance. Hence, NW FETs enable real-time label-free direct electrical readout of biological events, including binding/unbinding, enzymatic reactions and electron transfer, capabilities that are ideal for developing a platform to analyze biological samples.

Figure 8.

Schematic comparison of (top) a standard FET device and (bottom) a SiNW FET sensor. The NW surface is functionalized with a receptor layer to recognize target biomolecules in a solution, which are charged and provide a molecular gating effect on SiNWs. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 397. Copyright 2006 Future Medicine Ltd.

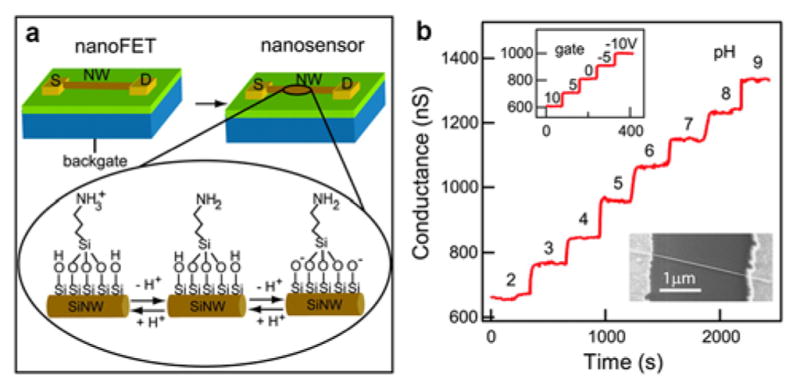

Semiconductor NWs composed of Si or other materials (e.g., ZnO and In2O3) have been used for the development of FET biosensors.388,400–401 Among them, the molecular-size diameter, high electron or hole mobility, and versatile surface functionalization of SiNWs, as well as the potential of interfacing with existing mature silicon industry processing, have endowed these NWs one of the most widely studied for biomolecular sensing.387 SiNW FETs are transformed into nanosensors by surface functionalization with probe molecules that enable the specific recognition of chemical/biological molecule targets. Covalent binding to the native silicon oxide (SiO2) layer that naturally grows on SiNWs represents one of the most robust approaches for probe attachment and takes advantage of the wealth of knowledge available from studies focused on functionalization of glass (SiO2) slides.402 A detailed SiNW surface functionalization protocol has been described elsewhere.403 The simplest and earliest established example of this approach is hydrogen–ion concentration detection or pH sensing.388 In this case, the SiO2 layer at a p–SiNW surface is modified with 3–aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), which yields amino group (–NH2) termination on the NW surface (Figure 9a). The amino groups and silanol groups (Si-OH) on the oxide layer undergo protonation and deprotonation as the hydrogen-ion concentration varies, thereby changing the surface charge and the NW conductance. The NW electrical conductance shows a stepwise, discrete and stable increase, in response to pH from 2 to 9 (Figure 9b). More recently, Noy and coworkers demonstrated SiNW FETs modified with lipid bilayers with and without ligand-gated and voltage-gated ion channels to monitor the solution pH. For lipid bilayer containing ion channels, devices responded to changes in solution pH, and when the channels were blocked the device response was strongly diminished.404 Sensing studies of several distinct classes of biological targets are discussed below.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic of a functionalized NW device and the protonation/deprotonation process that changes the surface charge state. (b) Changes in NW conductance versus pH. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 388. Copyright 2001 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

3.1.2. Protein Detection

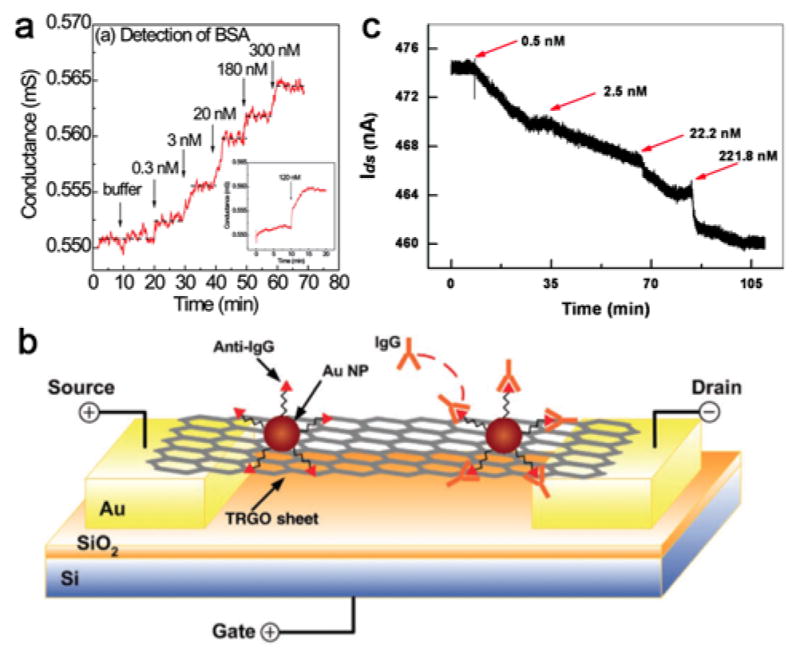

The sensitive detection of proteins, especially those known as disease markers, offers substantial potential to benefit disease diagnosis and treatment. In 2001, pioneering work demonstrated real-time protein sensing with SiNW FET devices.388 Specifically, SiNWs functionalized with biotin receptors were used to selectively detect streptavidin at concentrations down to 10 pM, substantially lower than other methods at the time. However, strong binding affinity between biotin and streptavidin leads to irreversible binding and precluded monitoring unbinding and sequential measurements at different streptavidin concentrations. To overcome this limitation, several reversible surface modifications have been explored, including biotin–monoclonal antibiotin binding and calmodulin (CaM)-Ca2+ interaction, to investigate quantitative concentration-dependent analyses.388 In a more recent study,391 CaM–modified SiNWs were used to detect Ca2+ and CaM–binding proteins through the association/dissociation interaction between glutathione and glutathione S–transferase. In addition, this basic approach has been used to demonstrate successful concentration-dependent detection of cardiac troponin T390 (a biomarker for myocardial infarction), SARS virus nucleocapsid proteins,405 and bovine serum albumin406 in recent literature and thus further validate the efficacy of NW FETs as protein sensors.

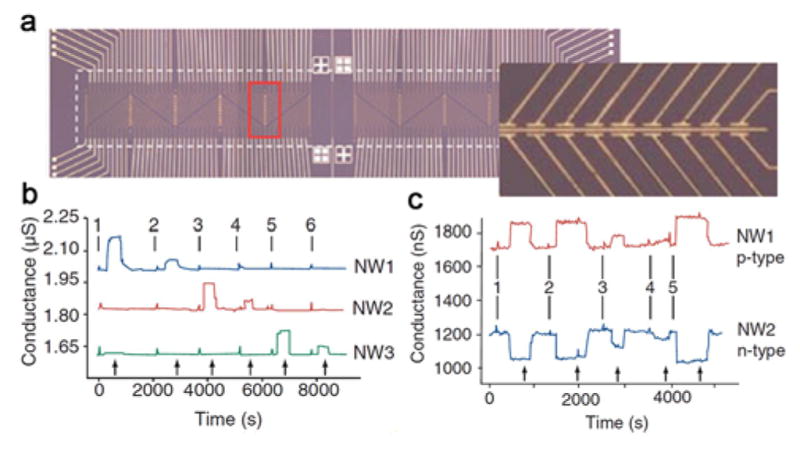

In genomics and proteomics research, simultaneous detection of multiple proteins is believed to be especially important for diagnosing complex diseases such as cancers.407–408 Moreover, the availability of different biomarkers matched with different stages of diseases could allow for early detection and robust diagnosis. The work described above using SiNW FET devices,388 although powerful in detecting binding/unbinding of proteins, lacked the capability of selective multiplexed sensing. To address this key issue, Zheng et al. developed integrated NW sensor arrays, in which ~100 individually addressable NW FETs were functionalized with several different receptors in 2005 (Figure 10a), and demonstrated several new sensing capabilities.389 Specifically, monoclonal antibodies for the cancer marker proteins prostate specific antigen (PSA) carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and mucin-1 were used to functionalize SiNW FETs in the same device array (Figure 10b). Upon addition of buffer solutions containing different concentrations of these cancer biomarkers, changes in electrical conductance of the corresponding NW FETs were recorded with femtomolar sensitivity, which is several orders of magnitude better than possible with the standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).389 This work also introduced the new concept of incorporating both p-type and n-type NWs into the same device array (Figure 10c). In so doing, the binding of a negatively charged biomarker such as PSA on the NW sensor surfaces led to an increase in conductance for p-SiNWs and a decrease for the n-SiNWs in the same sensor chip. These complementary, opposite electric signals can be used to distinguish false positive signals and enable real-time, highly sensitive and selective detection of multiplexed biomolecule targets. Similarly, Zhou and coworkers reported the complementary sensing of PSA using n-type In2O3 NWs and p-type SWNTs.400 The enhanced electrical conductance for the NW sensors and the suppressed electrical signal for the SWNT sensors upon the PSA addition are demonstrated with concentrations down to 5 ng/mL sensitivity at physiological buffer concentrations.

Figure 10.

(a) Optical image of a NW array. (b) Sequential detection of PSA, CEA and mucin–1 solutions using three SiNW FET sensors. (c) Complementary sensing of PSA using p–type (NW1) and n–type (NW2) SiNW FET sensors. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 389. Copyright 2005 Nature Publishing Group.

Later, an anisotropic wet–etch fabrication method was reported as an alternative ‘top-down’ NW device fabrication strategy for NW FET sensors.409 The sensitivity of these top-down fabricated SiNW devices were shown to have sub–100 fM sensitivity for biotin–streptavidin interaction, mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), and mouse immunoglobulin A (IgA) detection.

3.1.3. Nucleic Acid Detection

In addition to sensing protein binding/unbinding, real–time detection of nucleic acids (e.g., DNAs and RNAs) has been successfully carried out by Si and GaN NW FET devices.392–394,410 The surface functionalization methods and detection schemes are similar to those described above for protein sensing, where nucleic acid concentration is transduced following binding to a probe by changes in device conductance. Multisegment CdTe-Au-CdTe NWs in which Au segments are modified with thiol-terminated DNA probes and binding to these probes induces a conductance change in the overall device structure.411

A major difference between nucleic acid and protein detection exists in the fact that the high density of negative charges on the nucleic acid phosphate backbones requires high ionic strength buffers to screen the repulsion and allow for binding when DNA or RNA is used as the probe molecule. However, high ionic strength solutions have short Debye screening lengths (see Section 3.1.5.3), which can make difficult or preclude detection. A solution that overcomes this high ionic strength binding/screening issue involves using neutral charge peptide nucleic acids (PNAs),412–413 which exhibit excellent binding affinity with DNA at lower ionic strengths. Indeed, modification of SiNWs with PNA probe molecules was shown to exhibit time–dependent conductance changes associated with selective binding of complimentary target DNA at concentrations as low as 10 fM. Moreover, this work showed that DNA biosensor could be used to distinguish fully complementary (wild type) versus single–base mismatched (mutant) DNA targets associated with Cystic fibrosis.392 Additional studies using SiNWs functionalized with PNA probes in which the DNA target binding domain distance was changed exhibited a reduction in sensitivity with increasing distance between the hybridization site and the NW surface.414 This observation is consistent with basic sensing mechanism since the ‘field effect’ is reduced for fixed charge as the separation from the SiNW surface increases.

Alternatively, electrostatic adsorption has also been utilized for surface functionalization of SiNW devices used in DNA detection.415 Bunimovich et al. reported electrostatic adsorption of primary DNA probe strands onto an amine-terminated SiNW surfaces, where the ~parallel orientation of the DNA probes along the NW surface reduces Debye screening effects and can thereby yield sensitive DNA detection.415

More recently, detection of other nucleic acid targets using PNA–modified SiNWs has also been demonstrated. For instance, microRNAs (miRNAs), which are a large class of short, noncoding RNA molecules that regulate animal and plant genomes, have been proposed as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis.416 PNA–functionalized SiNW devices have shown the capability to detect miRNAs down to a remarkable sensitivity of 1 fM,417 ca. one order of magnitude better than reported earlier for DNA detection.414 This phenomenon can be attributed to the higher thermal stability and melting temperature of PNA–RNA complex than that of PNA–DNA complex. The technique enabled identification of fully complementary versus one-base mismatched miRNA sequences, as well as detection of miRNA in total RNA extracted from HeLa cells, and thus offers substantial potential as a new diagnostic tool.

3.1.4. Virus Detection

Viruses are the major cause of infectious diseases, which remain as the world’s leading cause of death.418 Successful treatment of viral diseases often depends upon rapid and accurate identification of viruses at ultralow concentrations. The first demonstration of nanoFET based virus sensor involved the detection of influenza A virus using SiNW devices. By recording the corresponding electrical conductance changes upon binding/unbinding of virus particles to monoclonal antibody-modified SiNWs, the selective detection of influenza A at the single particle level was demonstrated.395 The binding kinetics between different virus-receptor interactions were also electrically differentiated by SiNW FETs (Figure 11). In addition, simultaneous detection of influenza A and adenovirus using independent SiNW biosensors functionalized with distinct antibodies for these two types of viruses was demonstrated,395 and more recently, SiNW FET based selective detection of influenza A viruses down to 29 viral particles per micro-liter was achieved for breath condensate samples.419 Both of these achievements represent important proof-of-concept steps towards powerful viral diagnostic devices.

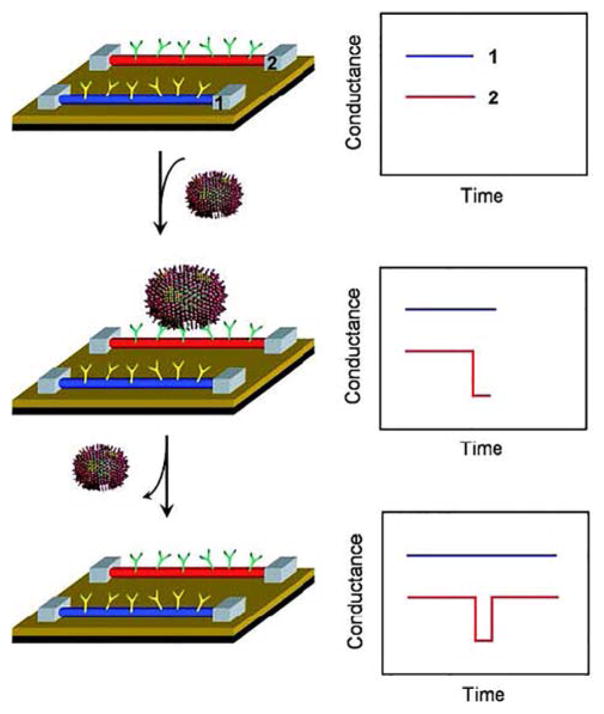

Figure 11.

Schematic of virus binding/unbinding to a SiNW FET and the corresponding time–dependent conductance change. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 395. Copyright 2004 National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Another example of virus detection is the diagnosis of Dengue, a commonly prevalent arthropod–borne viral infection.420 In this latter work, a specific nucleic acid fragment with 69 base pairs derived from Dengus serotype 2 virus genome sequence, was selected as the target DNA and amplified by the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The hybridization of the target DNA and PNA-functionalized SiNW FET sensors increases the device resistance, leading to a sensitivity limit down to 10 fM.

3.1.5. Methods for Enhancing the Sensitivity of Nanowire Sensors

3.1.5.1. 3D branched nanowires for enhanced efficiency in analyte capture

Three dimensional (3D) branched NWs,93–95,101,108,111 where secondary NW branches are grown in a radial direction from a primary NW backbone, provide the capability of achieving 3D connectivity. By functionally encoding at well-defined branch junctions during synthesis, these rationally designed and synthesized branched NWs provide well-controlled variations in the composition of the NW backbone and branches, and allow for complex electronic and photonic nanodevices. For instance, Jiang et al. developed the general synthesis of branched, single-crystalline semiconductor NW heterostructures, including Si backbones with Au branches.101 These Au-branched NW devices were investigated as nanoelectronic sensors for biomolecular detection. The Au branches, which can be modified in a highly-specific manner, act as the receptor-functionalized “antennas” for the biomolecule analyte, and provide the potential to achieve enhanced capturing efficiency and sensitivity through the 3D connectivity and interconnection. A sensitivity of 80 pg/mL for PSA detection was obtained from these mAb-modified p-Si/Au-branch NW FET sensors, with high selectivity.

3.1.5.2. Detection in subthreshold regime

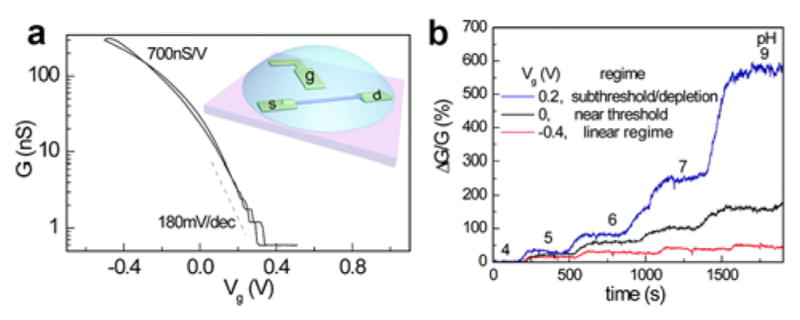

The fundamental characteristics of NW FET devices, such as the transconductance and noise, can have substantial effect on their detection sensitivity. Conventionally, nanoFET-based sensors are operated in the ‘ON’ state (above the threshold voltage), where the transconductance depends linearly on gate-voltage or surface potential. However, in the subthreshold regime it is well-known that the device conductance depends exponentially on gate-voltage,421 which could in principle lead to much higher analyte binding sensitivity. Indeed, Gao et al. have studied and compared carefully the detection sensitivity of SiNW FET sensors in the linear and subthreshold regimes (Figure 12).422 In previous literature using SiNW FET sensors,388 the conductance change (ΔG) or the resistance change (ΔR) of the sensor devices was used to quantify the concentration of the target molecules. However, an absolute signal change, such as ΔG, does not reflect the intrinsic device sensitivity, especially when working in the subthreshold regime where device conductance is very small. To better compare sensing in different device regimes Gao et al. used a dimensionless parameter, ΔG/G, to characterize and compare device sensitivities. This principle is exemplified in both pH and protein sensing experiments, where the electrolyte gating is used to tune the operational mode of NW FETs (Figure 12b), thus suggesting that significant sensitivity enhancement can be achieved by optimization of the FET operating conditions and understanding the fundamental electrical gating property of NW FETs. One caveat to the success of this work is that the device noise should be dominated by carrier-carrier scattering, such that the noise is also exponentially reduced in the subthreshold regime. If the noise is dominated by other scattering mechanisms, such as contact current injection and/or interface trapping/detrapping, then it may not be possible to exploit the exponential dependence of conductance on gate-voltage/surface potential in the subthreshold regime.

Figure 12.

(a) Conductance, G, vs Vg for a p-type SiNW FET. Inset: scheme for electrolyte gating. (b) Real time pH sensing. The device in the subthreshold regime shows much larger ΔG/G change versus pH. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 422. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

3.1.5.3. Reducing the Debye screening effect

Conventional FET sensors detect the concentration of the target species by their intrinsic charge. The charges of solution–based molecules, however, can be screened by dissolved counter ions in the solution. The Debye length, also known as the Debye radius, which is inversely proportional to the square root of the ionic strength of an electrolyte, represents the net or screened electrostatic effect of a charged species in ionic solution. A high ionic strength electrolyte solution leads to a short Debye length, and charges outside of the Debye length are electrically screened. For instance, the Debye length of 1× PBS, ~0.7 nm, can screen most protein antigen charges when they bind to an antibody modified FET surface. In order to reduce the charge screening effect of electrolyte solutions, the Debye length is typically increased by using dilute buffer solutions with low ion concentrations.405,423

Recently, several groups have reported approaches based on smaller receptors, such as aptamers424 and antibody fragments,425 to reduce the distance between the FET surface and biomolecule analyte being detected. These studies are promising, although further studies are needed to determine how general detection is under the limit of physiological conditions (Debye length <1 nm) as the sizes of the aptamer and antibody fragment receptors are similar to or greater than this critical length scale. Zhong and coworkers also reported a direct high-frequency measurement strategy for standard biological receptors, although those measurement requires significantly more complex device geometry, making difficult or precluding application to cellular and in vivo sensing.426

Very recently, Lieber and coworkers developed a new and general strategy to overcome this challenge for NW FET sensors that involves incorporating a biomolecule permeable polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer layer on the FET sensor, where the polymer increases the effective screening length near the NW FET surface to allow for detection in high ionic strength solutions.427 Using PSA as a model system, they showed that PEG-coated SiNW FETs can detect PSA in phosphate buffer concentrations up to 150 mM, with a detection sensitivity of ~10 nM and linear response range up to 1000 nM. In contrast, similar FETs without PEG functionalization can only detect PSA in buffer salt concentrations lower than 10 mM. This work suggests a new and general device design strategy for the FET sensor applications in physiological environments, important for in vitro and in vivo biological sensing.

3.1.5.4. Electrokinetic enhancement

Preconcentration by electrokinetic manipulation of particles offers advantageous alternative approach for high–sensitivity protein detection.428 In a nonuniform alternating current (AC) electric field, the dielectrophoresis (DEP) force can induce polarized particles to move in a directed manner leading to the formation of concentration enhancement and depletion regions in a microfluidic flow channel. Compared to the detection limit without AC excitation, NW sensors modified with monoclonal antibodies for PSA in an appropriate AC field exhibit close to a ~104 fold increase in sensitivity; that is, the protein concentration at the sensor surface is increased by DEP. In addition, NW devices functionalized with other receptors for capturing cholera toxin subunit B were also demonstrated, suggesting the general applicability of this method for enhanced sensitivity detection.

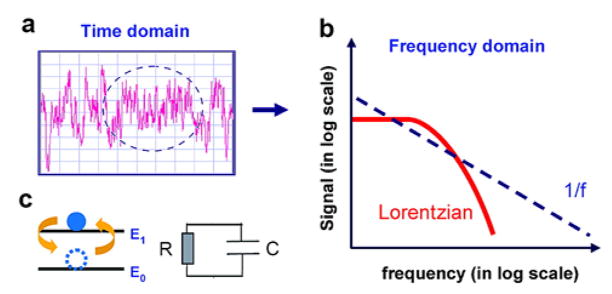

3.1.5.5. Frequency domain measurement

In addition to the conventional electrical measurement in real time, fluctuations in the NW FET electric signal at equilibrium can convey additional information about the dynamics of the biomolecule-NW hybrid system through a coupling to carrier transport in the device. For example, binding and unbinding can affect the intrinsic device noise and characterized through measurements of the device noise spectra (Figure 13a).429 In a recent study, the noise spectra in frequency domain was used to analyze contributions from different noise sources.429 The frequency domain spectrum of a two-level fluctuator system has the form of a Lorentzian function similar to that of a RC circuit (Figure 13b, c). The 1/f noise is well-known in conventional metal–oxide semiconductor FETs (MOSFETs), and arises from electron capture/emission from trap states.430–431 If biomolecule binding/unbinding contributes substantially to the noise, it can leads to a Lorentzian peak in addition to the 1/f spectrum background. Frequency domain noise spectra of SiNW FETs thus represents a means to study molecular binding kinetics and thermal fluctuations of the molecular layer on NW sensor surfaces.

Figure 13.

(a) Electrical noise in a time–domain measurement. (b) Lorentzian and 1/f functions in the frequency domain. (c) Models of a two–level system (left) and RC circuit (right). Reprinted with permission from Ref. 429. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

3.1.5.6. NW-nanopore sensors

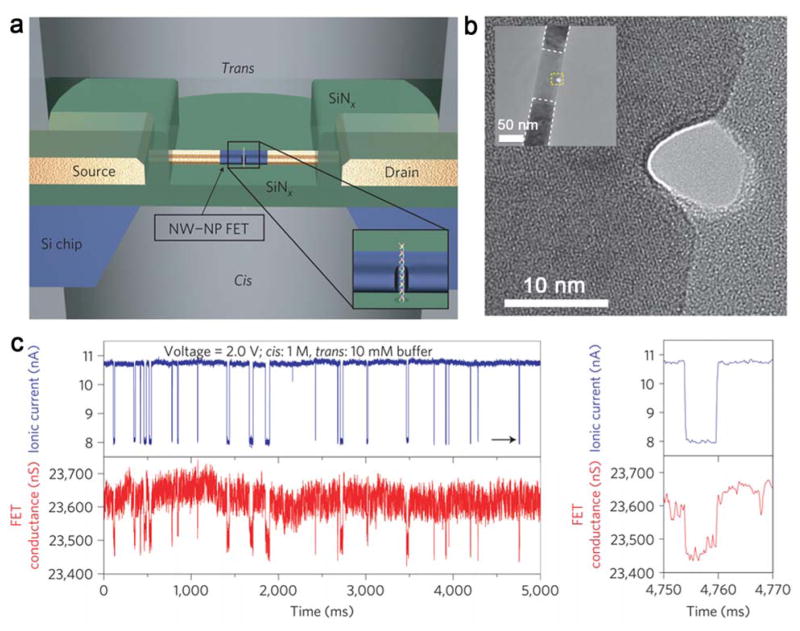

The integrated NW-nanopore FET sensor has the potential for single-molecule DNA sequencing at low cost and with high throughput.432 The conventional nanopore DNA sequencing technique records ionic current from nanopores,433 while the NW–nanopore sensors allow for direct sequencing of DNA molecules with fast translocation rates given the much higher bandwidth of the NW FET.

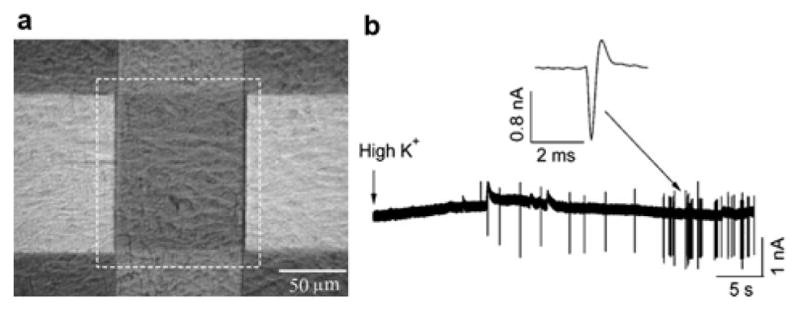

Studies have shown that nanopores can be introduced adjacent to SiNW FETs using the focused electron beam in a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 14a).432. A sensor device can then be configured by attaching PDMS solution reservoir chambers above and below the silicon nitride membrane on which the SiNW FET nanopore devices are fabricated. When the two chambers are filled with solutions of different ionic strength, FET signals corresponding to DNA translocation events can be recorded (Figure 14b, c). A 10–60 time higher signal is observed from the SiNW FET than that of the corresponding ionic current change. This work demonstrates a new nanopore sequencing device concept with fast sequencing and large–scale integration properties.

Figure 14.

(a, b) Schematic and TEM image of a SiNW-nanopore sensor. (c) Recording of SiNW-nanopore FET conductance and ionic current during DNA translocation. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 432. Copyright 2012 Nature Publishing Group.

3.1.5.7. Double-gate NW sensors

In order to achieve high sensitivity of NW FET sensors, extensive efforts have been focused on advanced lithographic tools and size–reduction techniques.434–435 For example, several groups have fabricated and explored double–gate NW FET biosensor, with two separated gates, G1 (primary) and G2 (secondary), straddling both sidewalls of the SiNW, to enhance device sensitivity.434–435 This work has shown that by applying the same voltage to G1 and G2, the threshold voltage (VT) in the double gate mode is very sensitive to a small change of VG2 (the G2 voltage). Therefore, compared to a single-gate FET sensor, the sensing window of the double-gated FET is significantly broadened, especially in the subthreshold regime described earlier.

3.1.5.8. Detection of biomolecules in physiological fluids

Rapid and accurate molecular analysis in physiological fluids (i.e., blood or serum) is essential for disease diagnosis and management. NW FET sensors, although powerful in ultrasensitive, real–time, multiplexed detection of multiple biomolecular species, exhibit fundamental limitations regarding molecular sensing in complex, physiological solutions. As the discussed above in Section 3.1.5.3, the primary limitation to FETs is related to Debye screening effect436 in high ionic strength blood/serum samples.

To overcome the limitation of Debye length, researchers have developed methods to detect blood/serum samples in a controlled manner. One immediate method to reduce the ion concentration is to dilute the blood sample with a buffer solution.437 However, the diluting method has an impact on ligand-protein and protein-protein interactions and also reduces the analyte concentration, which would raise the requirement for the device sensitivity instead. The second approach is to desalt the serum samples before the multiplex detection of biomarkers,389 although this might lead to a loss of target proteins during the desalting step. A third method involves introduction of a microfluidic purification chip (MPC) system to pre–isolate the target molecules and release them into a pure buffer suitable for sensing, followed by the analysis using SiNW FET arrays438 in much the same manner as done with desalting approach.389 The two-stage approach captures the targets from a complex environment such as a whole blood, and reduces sample consumption by effectively pre-concentrating the biomarkers. A fourth method adopts a steady–state measurement instead of a real-time recording.439 Specifically, the resistance of the SiNW is measured in a low ionic strength buffer solution after antibody functionalization. Then, the SiNW sensor is incubated with undiluted serum and subsequently washed to remove unbound proteins, followed by the measurement of the second resistance value in the buffer solution. The concentration of the target molecules can be calculated according to the resistance change before and after antibody-antigen interaction. This method is independent of the ionic strength of the sample solution, thus circumventing the Debye screening in physiological fluids. A final reported method uses small antibody fragments, which have been proposed to allow antigen binding to the NW surface within the Debye length.425 In this approach, the sizes of antibody probes are reduced through common bioengineering methods, and thus both the signal transduction efficiency and the detection capability can be improved.

The long-term stability of the SiNW nanoelectronic devices in physiological studies has also been investigated.440 Coated with a thin layer of Al2O3, SiNW FETs yield long-term stability (>4 months) in physiological model solutions at 37°C. When coated with HfO2 as the surface protection layer, an even much longer of stability of >1 year has been demonstrated by SiNW FETs in physiological model solutions. These latter results suggest the potential of the SiNW FETs for long-term chronic in vivo studies in animals and biomedical implants.

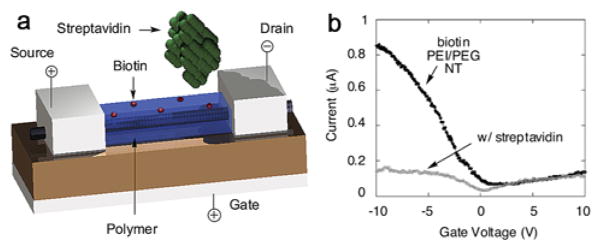

3.2.Carbon Nanotube Biosensors

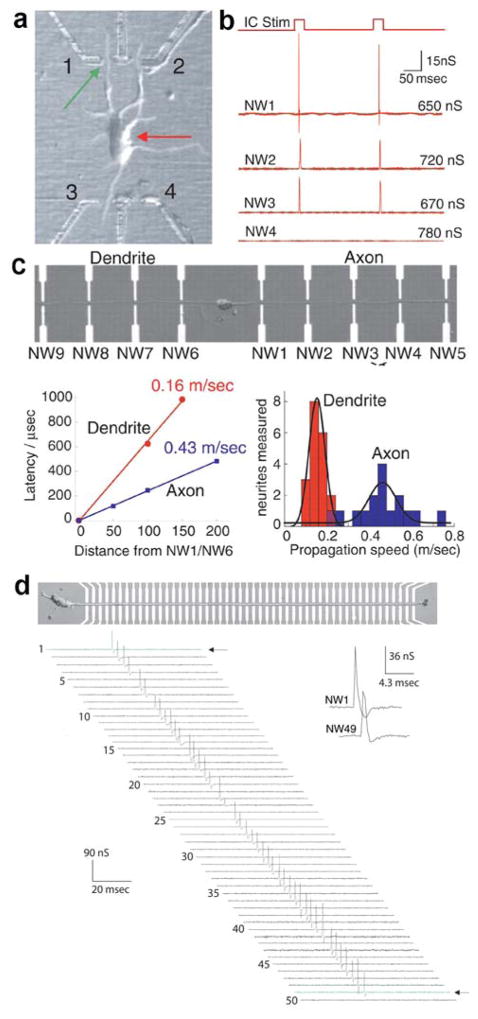

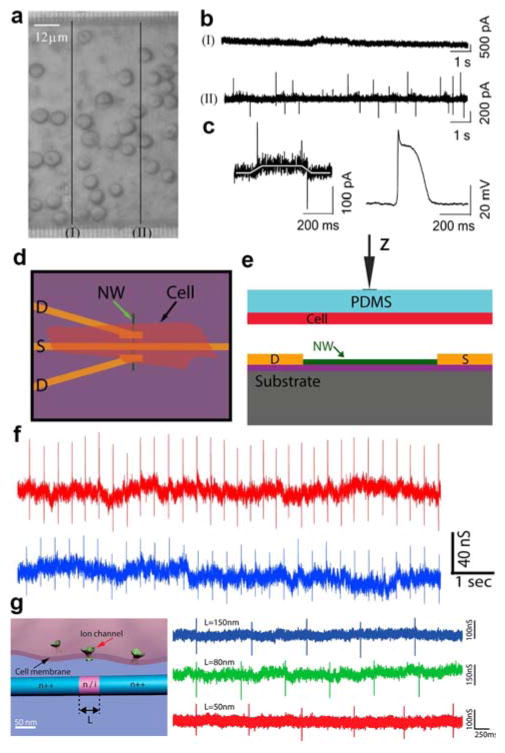

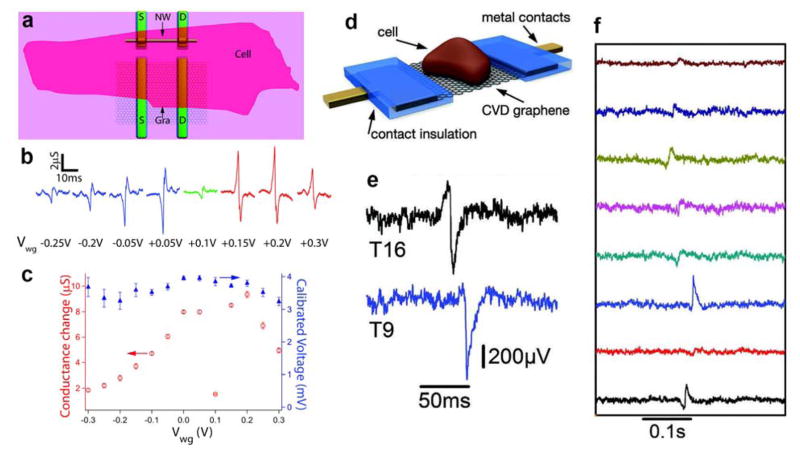

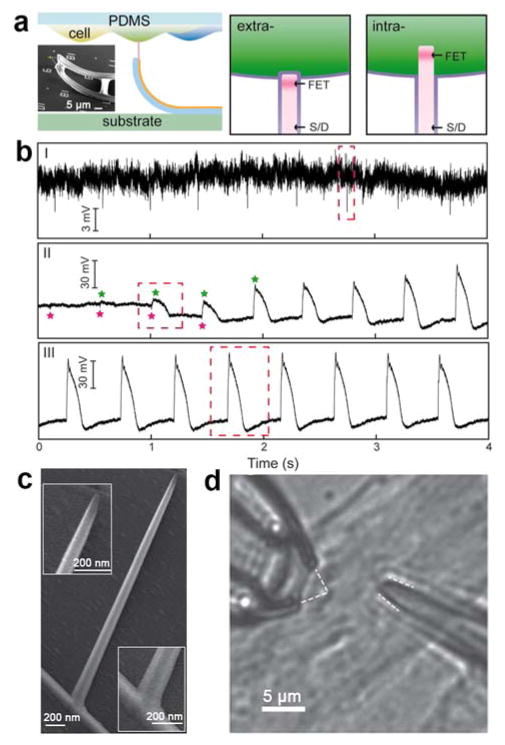

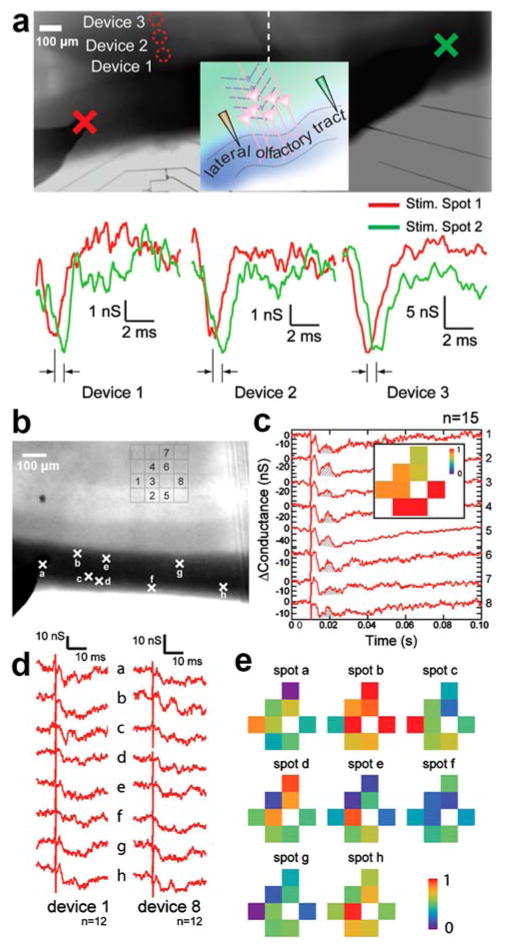

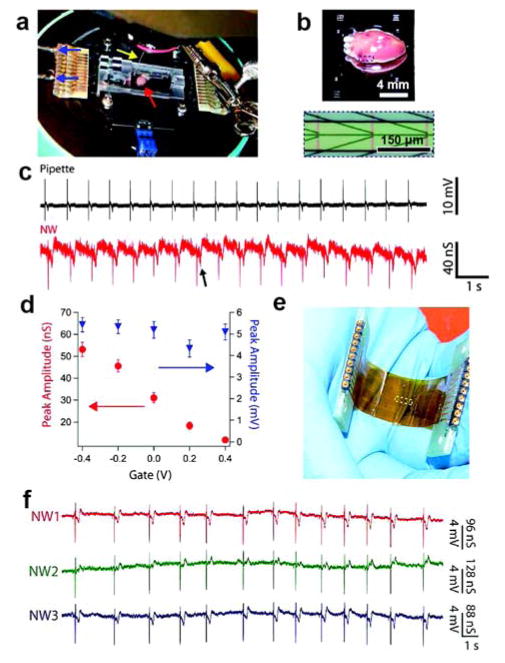

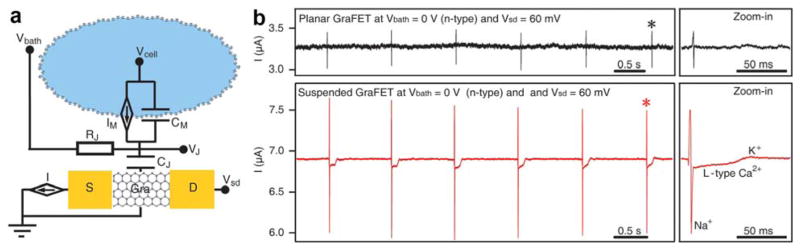

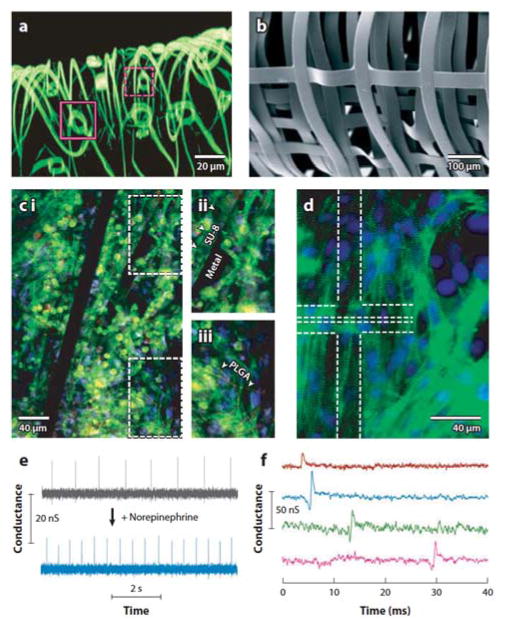

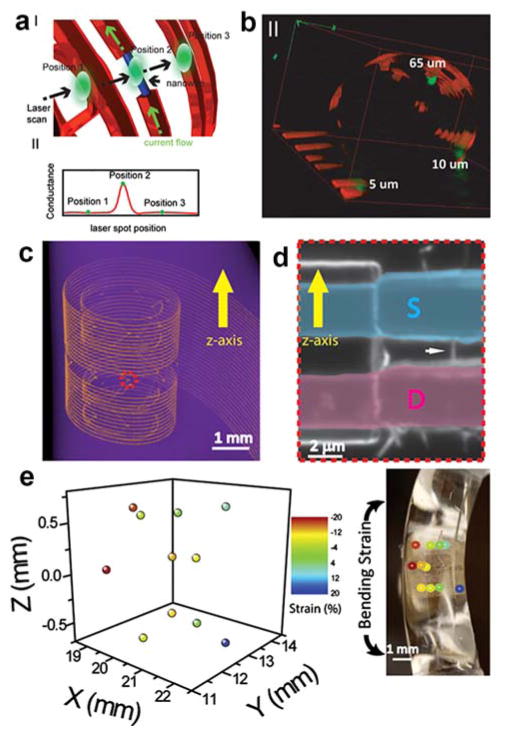

CNTs can be configured as either electrochemical or FET sensors, where the latter are similar to NW-based FET biosensors discussed above. In the former case of electrochemical sensors, the CNTs are used as electrodes where there small diameters can provide advantages versus traditional metal electrodes. For more information on CNT electrochemical sensors we refer readers to other reviews.441–445 Here, we will focus on SWNT-FET biosensors446–450 composed of single SWNTs or SWNT networks on SiO2/Si substrates with S/D electrodes.