SUMMARY

Centrioles are essential for the assembly of both centrosomes and cilia. Centriole biogenesis occurs once and only once per cell cycle and it is temporally coordinated with cell cycle progression, ensuring the formation of the right number of centrioles at the right time. The formation of new daughter centrioles is guided by a pre-existent, mother centriole. The proximity between mother and daughter centrioles was proposed to restrict new centriole formation until they separate beyond a critical distance. Paradoxically, mother and daughter centrioles overcome that distance in early mitosis, at a time where triggers for centriole biogenesis Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), and its substrate STIL, are abundant. Here we show that in mitosis, the mitotic kinase CDK1/CyclinB binds STIL, and prevents formation of the PLK4-STIL complex and STIL phosphorylation by PLK4, thus inhibiting untimely onset of centriole biogenesis. After CDK1/CyclinB inactivation upon mitotic exit, PLK4 can bind and phosphorylate STIL in G1, allowing pro-centriole assembly in the subsequent S phase. Our work shows that complementary mechanisms, such as mother-daughter centriole proximity and CDK1/CyclinB interaction with centriolar components, ensure that centriole biogenesis occurs once and only once per cell cycle, raising parallels with the cell cycle regulation of DNA replication and centromere formation.

Keywords: PLK4, CDK, STIL, Mitosis, Centriole duplication, Licensing, centrosome

INTRODUCTION

Centrosomes are the main microtubule organizing centers (MTOC) of mammalian cells [1], being composed of two centrioles. These are surrounded by the pericentriolar material, which nucleates microtubules and organizes the cytoskeleton. Centrioles can also nucleate the ciliary axoneme. Centriole number is highly controlled in cells; abnormalities can lead to defects in spindle and cilia assembly [1]. A new (daughter) centriole normally forms in physical proximity of a pre-existing (mother) centriole; this occurs once and only once per cell cycle (centriole-guided assembly). When no preexisting centrioles are found in a cell, centrioles can also form “de novo”, and in this case they form in random numbers [1]. Interestingly, the timing of centriole biogenesis is conserved in both; new centrioles only form in S-phase [2].

Both centriole-guided and de novo biogenesis are dependent on and initiated by Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) [3–5]. In the case of centriole-guided biogenesis, PLK4 is recruited to the proximal end of the mother centriole, determining the place of biogenesis [6]. PLK4 binds and phosphorylates STIL (SIL: SCL/TAL1/SAS-5/Ana2), recruiting it to the centriole [7–11]. Phosphorylated STIL in turn brings SAS6 to the centrioles to form the centriole cartwheel [7, 8], the first visible structure in centriole assembly that helps defining the centriolar 9-fold symmetry [12]. Over-expression or stabilization of PLK4, STIL or SAS6 leads to supernumerary centrioles, while their individual depletion blocks centriole duplication [3, 12].

Centriole biogenesis is tightly coupled to cell cycle progression. The formation of the cartwheel is detectable early in S-phase, concomitantly with the start of DNA replication [1, 13]. Paradoxically, PLK4, STIL and SAS6 are present at the centrosome in mid-G1 up until the end of mitosis [9, 14–16]. The physical proximity between mother and daughter centriole is thought to prevent formation of yet another daughter centriole in S, G2 and Mitosis [1, 17]. However, already in a natural or arrested prophase and prometaphase, mother and daughter centriole reach a critical distance from each other shown to be permissive for centriole reduplication, yet they do not reduplicate at that stage [18–20]. Moreover, it has been shown in both Drosophila and Xenopus egg extracts that while PLK4 can induce de novo MTOC formation upon meiosis exit, it cannot do it in meiosis-arrested eggs or extracts [21, 22]. Together, these facts suggest the existence of additional levels of regulation during high CDK1/CyclinB activity phases, such as mitosis and meiosis.

Here, we explored the mechanism that couples cell cycle progression to the first molecular events in centriole biogenesis: PLK4-STIL complex formation and STIL phosphorylation. We show that CDK1/CyclinB prevents precocious PLK4-STIL complex assembly and STIL phosphorylation by PLK4, through direct binding to STIL. Upon mitotic exit and consequent CDK1/CyclinB degradation, PLK4 can bind and phosphorylate STIL, which recruits SAS6.

RESULTS

We first ask when the activity of the trigger of centriole biogenesis, PLK4, is required. We used Xenopus egg extracts which allow tight cell cycle synchrony and are naturally acentriolar, and therefore uniquely suited to investigate the biochemical regulation of de novo centriole biogenesis in the absence of physical constraints imposed by the close proximity of the mother centriole. Endogenous Xenopus PLK4 (PLX4) is not detectable in extracts and not sufficient to generate MTOCs de novo, presumably, due to low expression levels of this kinase [23]. However, overexpression of PLX4 is sufficient to induce de novo assembly of γ-tubulin-containing MTOCs [22], offering an assay to understand the biochemical connection between cell cycle and PLK4’s role in MTOC formation.

PLK4 can only trigger de novo MTOC formation after exit from M-phase

We used the well-characterized CSF-extract, which is prepared from Xenopus eggs arrested at the second meiotic metaphase (MII) by the cytostatic factor (CSF). This extract allows the sequential study of three different biochemical states. First, the CSF-arrested state (from here on referred to as “M-phase”), which has high CDK1/CyclinB activity (Figure 1A). Second, a CSF-exit/M-exit state, which normally onsets following fertilization, but can be artificially induced through the addition of Ca2+ to the M-phase extract [24]. The addition of Ca2+ inactivates the CSF, followed by cyclin degradation by the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C), and dephosphorylation of CDK1/CyclinB substrates, such as Cdc25 (Figure 1A). This biochemical state corresponds to a very low CDK activity state. Finally, we use an interphase (CSF-released) state, a later time point after Ca2+ addition to the CSF extract, which corresponds to S-phase, as embryonic cycles are devoid of defined gap phases, such as G1 [25] (Figure 1A).

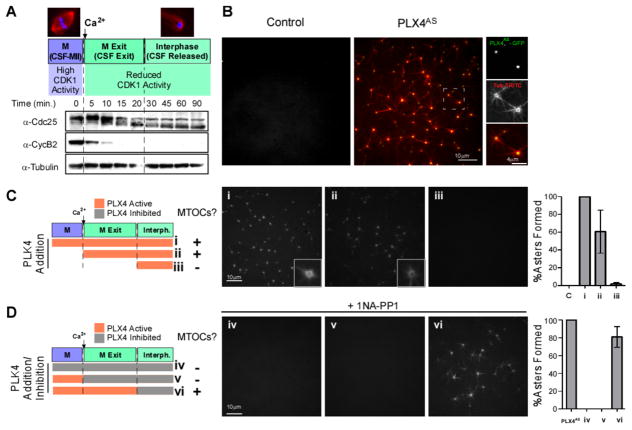

Figure 1. PLX4 induces de novo aster formation early after M-phase (CSF) release in Xenopus egg extracts.

A. Cell cycle profiling of Xenopus M-phase extracts released with Ca2+. Western blots (WB) show the kinetics of Cdc25 downshift and CyclinB2 degradation leading to reduced CDK1 activity. B. GFP-PLX4AS-induces MTOC formation in M-phase released extracts. CSF extract was incubated with 0.65 μM GFP-PLX4AS, (green) and TRITC-tubulin (red). See also Figure S1, S2C for the generation and characterization of Shokat alleles. (See also Movie S1 and S2) C. Cell cycle-dependent effect of PLX4. rPLX4 was added at different time points: (i) 10 mins before release (add Ca2+), (ii) concomitantly with release, and (iii) 20 mins after release, in order to check when PLK4 activity is needed to form MTOCs (TRITC-tubulin). D. Inhibition of PLX4AS using 1 NA-PP1 at different stages. PLX4AS was added 10 mins before Ca2+ and was inhibited by 1NA-PP1 in extracts at different time points: (iv) at time zero (v) with Ca2+, and (vi) 20 mins after Ca2+. Panels of MTOCs formed in the extract under each condition, stained with TRITC-tubulin, are shown. Asters were counted in 10 images for each condition, and normalized to the number of asters observed in control extracts ((i) in C and PLX4AS in D) (n=3, Bars represent average +/−SD).

Addition of recombinant Xenopus PLK4 (rPLX4WT) induces de novo assembly of MTOCs in cycling extracts positive for γ-tubulin ([22], and Figure S1A) and other centriolar markers (Cep135, Centrin-1, Figure S1B). Despite the similarity with centriole biogenesis, we never observed nine-fold symmetrical structures by electron microscopy (not shown), suggesting the lack of a limiting assembly factor.

To specifically inhibit PLK4’s activity along the cell cycle, we generated an ATP-analog-sensitive recombinant PLX4 variant (also called “Shokat kinase” [26]), which can be specifically inhibited by ATP-analogues. Previously, the substitution of a Leucine residue by a Glycine (L89G) in the ATP binding pocket of hsPLK4 was reported to enhance the sensitivity to ATP analogues as desired ([27] and Figure S2A), albeit at the cost of a 10-fold reduction in activity in the absence of the ATP-analogue inhibitor ([27] and Figure S2B). After testing several combinations, we determined that a L89A substitution combined with a compensatory mutation outside of the ATP binding pocket (H188Y) ([28] and Figure S2A and S2B) restored both human and Xenopus PLK4’s activities to wild-type levels (Figure S2B and S2C). Hereafter, these Shokat alleles of PLK4 are referred to as recombinant analogue-sensitive PLX4/PLK4 (rPLX4AS/PLK4AS). rPLX4AS induced de novo formation of MTOCs as efficiently as rPLX4WT (Figure 1B and Movie S1). The ATP analogue 1-Naphthyl-PP1 (1-NA-PP1) [29] was found to be a potent inhibitor of rPLX4AS but not of rPLX4WT (not shown) in vitro (Figure S2D and S2E and MovieS2).

Addition of rPLX4AS to either M-phase (Figure 1C, (i)), or M-exit extracts (Figure 1C, (ii)), allowed MTOCs to form after M-phase exit. Addition of rPLX4AS in interphase itself (when the extract had completely exited M-phase; “CSF-released”) did not trigger MTOC formation (Figure 1C, (iii)). To further investigate the timing we added rPLX4AS in M phase, and inhibited by 1-NA-PP1 in: M-phase (Figure 1D, (iv)), at the exit of M-phase (Figure 1D, (v)) or in interphase (Figure 1D, (vi)). We only observed MTOC formation if rPLX4AS was active at M-exit suggesting that it triggers de novo MTOC formation at a stage in which CDK activity is very low.

Centriole duplication in human cells requires active PLK4 after exit from mitosis

To investigate if a similar temporal requirement for PLK4 activity operates in the presence of centrioles and defined G1 and G2 phases, we generated a HeLa cell line conditionally expressing the human “Shokat” allele PLK4AS (L89A/H188Y) (Figure S2A–B and S2F). Cells were simultaneously depleted of endogenous PLK4, and induced to express RNAi-resistant-PLK4AS, which rescued the reduction in centriole number caused by depletion of endogenous wild-type PLK4 (Figure S2G). Importantly, while 1-NA-PP1 treatment alone had no effect on centriole number or cell cycle progression (not shown), addition of 1-NA-PP1 to the growth media ablated the ability of PLK4AS to rescue centriole duplication, while RNAi-resistant-PLK4WT (expressed from the same tetracycline-inducible promoter) was unaffected (Figure S2G).

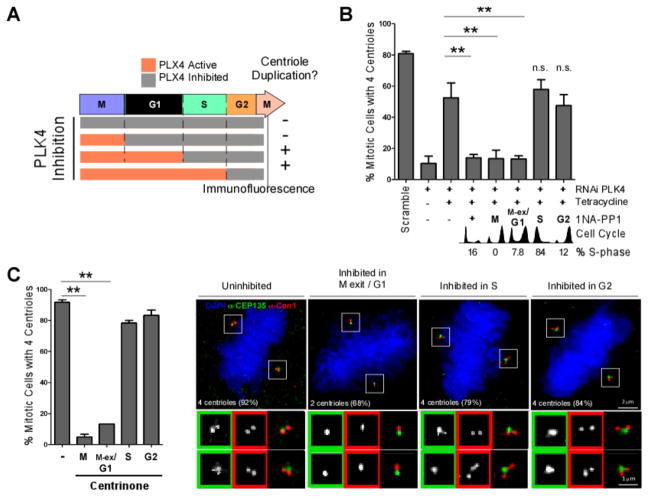

1-NA-PP1 was added to synchronous cells expressing PLK4AS (and depleted of endogenous PLK4) at mitosis, G1, S-phase and G2 (monitored by flow-cytometry and EdU incorporation, Figure 2A and 2B, and enlarged in Figure S2H–I). The percentage of cells with the expected 4 centrioles in the subsequent mitosis was assessed. Similarly to Xenopus extracts, inhibition of PLK4 in a low CDK stage (mitotic exit and G1), reduced the percentage of cells able to duplicate their centrioles by approximately four-fold (Figure 2A and B). Surprisingly, given that centrioles start to be assembled in S phase, PLK4 inhibition during S-phase or G2 had no major effect on the number of centrioles present in mitotic cells in the same cycle (Figure 2A and 2B). We confirmed these findings using the recently-described PLK4-specific inhibitor Centrinone [30]. Only cells inhibited from mitosis onwards, of the previous cycle, or from G1 of the same cycle, showed a significant decrease in centriole duplication efficiency (Figure 2C and Figure S2J) suggesting, again, that PLK4 acts in low CDK activity stages. In human cells, we could not perform controlled experiments of inhibition in mitosis, followed by release of inhibition as PLK4 catalyzes its own degradation [3]. Inhibited PLK4 accumulates, causing centriole over-amplification upon inhibitor wash-off (previously shown in [30]).

Figure 2. PLK4 activity is needed at M-phase exit/G1 for centriole duplication in human cells.

A–C. PLK4 activity was inhibited at different cell cycle times by 1NA-PP1 (PLK4AS) (B) or centrinone (C), and centrioles were counted in the subsequent mitosis. A. Experimental scheme and summary of results from B–C. B. 1NA-PP1 was added to cells expressing PLK4AS and depleted of endogenous PLK4 at 0 hrs (positive control, (+)), 6 (G2), 8 (M), 10 (M-exit/G1) and 20 hrs (S-phase) following S-phase block release. Cells were fixed in the immediate subsequent mitosis, and centrioles counted (n=3, 100 cells/condition, mean +/− SEM. ** = p<0.01). Cell cycle profiles were obtained by flow cytometry. Percentage of S-phase cells at time of inhibition were monitored by EdU staining (See also Figure S2F–I for controls). C. Centrinone was added at the indicated cell cycle stages and centrioles were counted in the subsequent mitosis. (n=3, 100 cells/condition. mean +/− SEM. ** = p<0.01). Representative immunofluorescence images of mitotic cells stained as indicated, following inhibition of PLK4 by centrinone. The number of centrioles found with the highest frequency upon inhibition is shown (average of 3 experiments). See Figure S2J for detailed quantitation.

The PLK4-STIL complex only forms upon M-exit

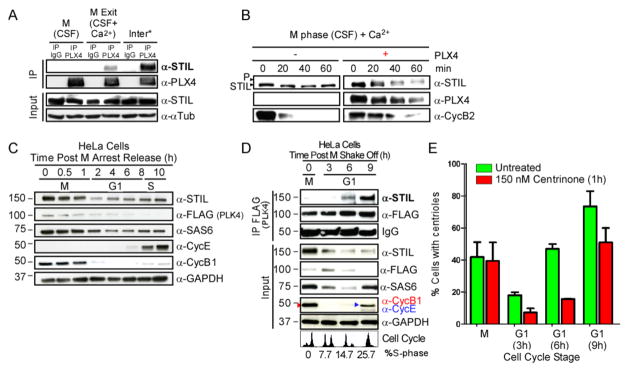

To understand the regulation of PLK4 activity in time, we focused on the first reported event of centriole biogenesis: the formation of the PLK4-STIL complex and asked whether it occurs at M exit/G1. We first confirmed that STIL has a conserved role in MTOC formation in Xenopus extracts (Figure S3A–D). STIL is present and its depletion precluded the formation rPLX4-induced MTOCs (Figure S3A–C). Moreover, rPLX4AS was able to bind and phosphorylate STIL (Figure S3D). Our results suggest a general, conserved mechanism in which STIL is phosphorylated by PLK4 and is required for rPLX4-induced MTOC formation, similarly to what is described for human cells [7–10]. Next, we observed that rPLX4 cannot bind STIL in M-phase, but only after M-exit (Figure 3A), at which time it can also phosphorylate it (see shift of STIL band; Figure 3B).

Figure 3. The PLK4-STIL complex forms only upon M-exit in Xenopus extracts and human cells.

A. PLX4 binds STIL only after mitotic-exit in Xenopus extracts. (See also Figure S3A–D). rPLX4 was supplemented to extracts at the indicated stages, and subsequently immunoprecipitated (PLX4-IP). Samples were analyzed by WB, and probed with the indicated antibodies. (*) refers to an interphase extract (see methods). B. PLX4 is likely to phosphorylate STIL upon M-exit in Xenopus extracts. Released-extracts were supplemented with rPLX4. STIL phosphorylation (note the mobility shift) and levels of CyclinB2 were analyzed by WB. C. STIL peaks in mitosis in human cells. FLAG-PLK4 over-expressing HeLa cells were synchronized in mitosis by monastrol, and released. Samples were collected at the indicated times. D. The PLK4-STIL complex forms in mid-G1. FLAG-PLK4 was immuno-precipitated from cell lysates at the indicated stages. Samples were probed with the indicated antibodies. Cell cycle profiles were obtained by flow cytometry combined with BrdU-FITC labeling of cells in S phase. See Figure S3E for more details. E. STIL recruitment to the centrosome during mid-G1 phase is dependent on PLK4 activity. Presence of STIL at the centrosome was quantified by immunofluorescence using anti-STIL in mitotic or G1 cells obtained after mitotic shake-off. DMSO (control) or centrinone (PLK4 inhibitor) was added 1hr prior to fixation. The absence of S-phase cells in G1 was corroborated by EdU incorporation. (n=3, 100 cells/condition, mean +/− SEM). See also Figure S3F, S3G, S4A and S4B for more details on these experiments.

We then asked how PLK4-STIL complex formation is regulated in the presence of centrioles in human cells. We immunoprecipitated FLAG-PLK4 from HeLa cells synchronized in different cell cycle stages preceding S-phase onset; mitosis (M), early (3hrs post mitosis – “PM”), mid (6hrs PM) and late (9hrs PM), G1 (Figure 3C–E and Figure S3E). Even though both STIL and PLK4 concentrations are highest in mitosis (Figure 3C–E and Figures S3F and S4A and S4B) [15, 16], PLK4-STIL interaction was only observed during mid and late G1 phases, 6 and 9hrs after mitotic exit respectively (Figure 3D and Figure S3E). PLK4 is detectable at the centrosome in those stages (Figure S4A and S4B), and consistently, the percentage of cells with STIL localizing to the centrosome increased significantly starting at mid-G1 (Figure 3E). This was followed by a significant increase of cells with SAS6 localizing to the centrosome in late-G1 (9hrs PM; Figure S3G). Importantly, cells treated with the PLK4 inhibitor “Centrinone” for one hour prior to fixation, showed a marked reduction in STIL and SAS6 presence at the centrosome in G1 but not in mitosis (Figure 3E, S3G). Our observations suggest that either the recruitment or the maintenance of STIL, and consequently of SAS6, at the centrosome in human cells is dependent on PLK4 activity during G1.

Taken together, our results show that despite the fact that both STIL and PLK4 are present in high CDK1/CyclinB activity states in both acentriolar Xenopus egg extracts and in human cells, the two proteins do not form a complex in either of the systems at these stages (Figure 3), suggesting a conserved inhibitory mechanism related to CDK1/CyclinB activity.

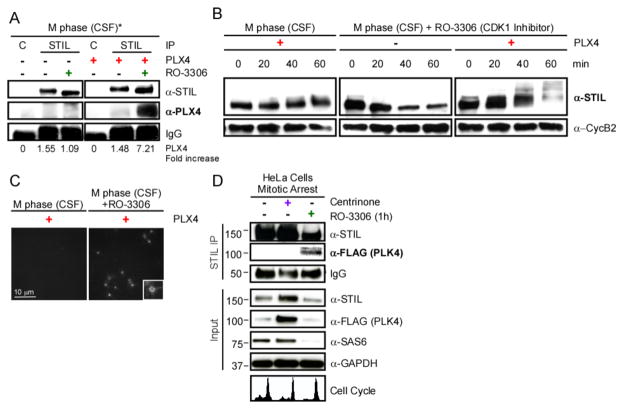

Inhibiting CDK1/CyclinB allows for PLK4-STIL complex assembly

We asked whether direct inhibition of CDK1 by the CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306 [31] would permit unscheduled complex formation. CDK1 inhibition in M-phase released the extracts to interphase, and this was sufficient for rPLX4 to bind -and likely phosphorylate-STIL (see STIL mobility shift upon rPLX4 addition; Figure 4A and 4B), and to induce MTOC formation (Figure 4C). Likewise, acute inhibition of CDK1 activity in human cells blocked in mitosis restored the PLK4-STIL interaction (Figure 4D and Figure S4C). Taken together these results strongly corroborate an inhibitory function of CDK1 in PLK4-STIL complex assembly.

Figure 4. PLK4-STIL complex formation is inhibited by CDK1. A. Inhibiting CDK1 allows PLK4-STIL complex assembly.

STIL was immunoprecipitated from extracts treated as indicated. Samples were analyzed by WB, probed with the indicated antibodies. Fold increase over control in signal intensity was quantified for each condition. Note that endogenous PLX4 is undetectable. *Addition of RO-3306, a CDK1 inhibitor, releases the extract into interphase. B. Phosphorylation of STIL in CSF/M-phase arrested extracts treated with RO-3306. M-phase extracts were treated as indicated. STIL phosphorylation and CyclinB2 were analyzed by WB. C. PLX4 induces asters in M-phase extracts released with RO-3306. Confocal images of M-phase extracts supplemented with rPLX4 and 100 μM RO-3306, in the presence of TRITC-labeled tubulin. D. CDK1/CyclinB activity is inhibitory for the formation of the PLK4-STIL complex. Nocodazole arrested cells in mitosis were treated as indicated. STIL was immunoprecipitated and samples were probed with the indicated antibodies. Note that under centrinone treatment, PLK4 accumulates [30]. Cell cycle profiles were obtained by flow cytometry; see Figure S4C for details.

CDK1/CyclinB phosphorylates and binds to STIL

CDK1/CyclinB prevents the initiation of DNA replication (i.e. licensing) both by phosphorylation of (i.e. Orc2) and binding to (i.e. Orc6) components that are required for that step [32, 33]. We thus asked whether CDK1/CyclinB could regulate PLK4-STIL complex assembly, either by phosphorylating and/or binding to STIL.

Given that STIL is highly phosphorylated in M-phase (Figure S5A) and its localization at the centrosome is dependent on CDK1 activity [34], we tested whether it is a substrate of CDK1/CyclinB. In vitro kinase assays show incorporation of 32P-radiolabeled-ATP into STIL in the presence of either CDK1/CyclinB or PLX4 (positive control) (Figure S5A and S5B).

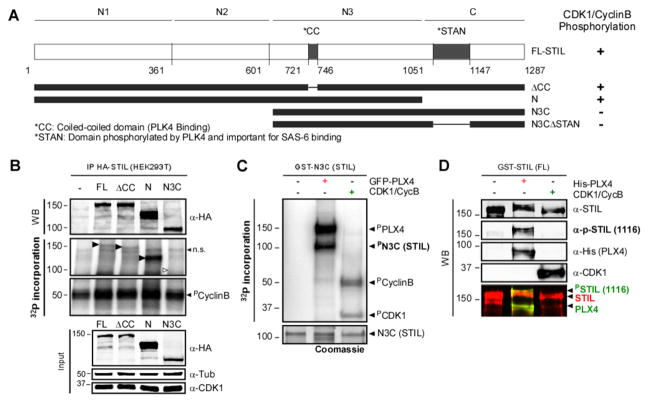

We then ask whether CDK1/CyclinB could phosphorylate and/or bind the domains/residues in STIL that normally bind/are phosphorylated by PLK4, to prevent their interaction. PLK4 binds to STIL in the coiled-coil domain ([7–10] and Figure 5A; “CC”) and phosphorylates STIL on a domain known as STAN motif; leading to SAS6 recruitment and cartwheel assembly [7–10]. We used HA-tagged Full Length STIL (FL) and truncated STIL fragments previously described by Ohta and colleagues [7] (ΔCC, N-terminal domain (N) and N3C, Figure 5A) expressed in HEK293T cells, as substrates in an in vitro kinase assay. Importantly, we show that CDK1/CyclinB phosphorylates the N-terminal domain of STIL, but not the region encompassing the CC or STAN motifs (Figure 5B–C and confirmed with phospho-specific antibodies against a residue phosphorylated by PLK4 S1116 in the STAN domain [8] in Figure 5D). Therefore, CDK1/CyclinB phosphorylates STIL but on a physically distinct site to the one bound and phosphorylated by PLK4.

Figure 5. CDK1/CyclinB phosphorylates STIL outside of the PLK4 interacting domain in human cells.

A. Schematic representation of HA- and GST-tagged STIL constructs. The evolutionary conserved coiled-coil (CC; PLK4-binding) and STAN (PLK4-phosphorylated and SAS6 binding) domains are indicated. Constructs were used for phosphorylation assays. The results are summarized on the right. B. CDK1/ Cyclin B can phosphorylate STIL on its N-terminus. Autoradiography of an In vitro kinase assay using IP control, or HA-STIL (FL, ΔCC, N and N3C), CDK1/Cyclin B and ([γ-32P]-ATP). Black arrows show phosphorylated fragments. White arrow indicates the expected position of the non-phosphorylated N3C fragment (n.s.=non-specific). Note that all fragments, but not the N3C, are phosphorylated by CDK1/CyclinB. C. STIL-N3C, the domain that interacts with PLK4 and SAS6, is not phosphorylated by CDK1/CyclinB. Incorporation of [γ-32P] on STIL-N3C incubated with GFP-PLX4 or CDK1/CyclinB was visualized by autoradiography. D. CDK1/CyclinB does not phosphorylate STIL on the site phosphorylated by PLK4 (S1116). Recombinant GST-STIL (FL) was incubated with rPLX4 or CDK1/CyclinB. Samples were analyzed by WB using anti-pS1116-STIL (which recognizes a PLK4-specific phosphorylation [8]), anti-His and anti-CDK1 to monitor loaded proteins.

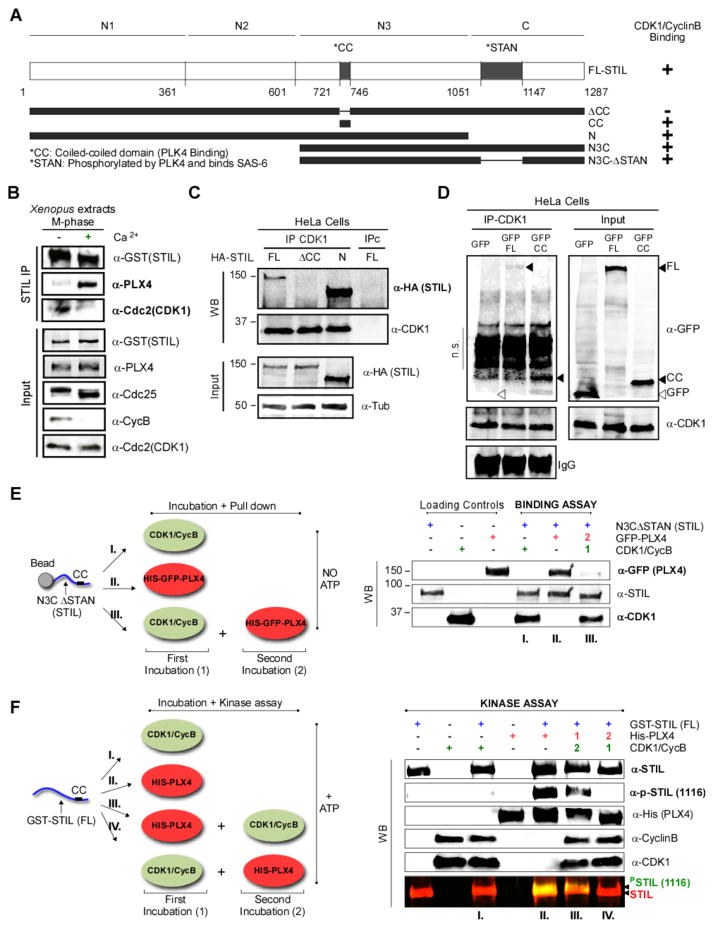

We then tested whether CDK1/CyclinB could bind STIL in vivo. We observed that indeed CDK1/CyclinB co-immunoprecipitates with STIL in Xenopus extracts arrested in M-phase, but not after M-exit when Cyclin B is degraded (Figure 6A and B). Similarly, when treating M-phase extracts with the CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306 in which the CDK1/CyclinB complex is inactive, but CyclinB is not degraded due to the natural absence of Cdh1, inactivated CDK1/CyclinB could not bind STIL (Figure S5C1). Conversely, PLK4 binding to STIL was re-established (Figure S5C2).

Figure 6. CDK1/Cyclin B binds STIL on its CC domain and competes with PLK4 binding.

A. Representation of HA-, GST- and GFP-tagged STIL constructs and summary of results. The evolutionary conserved coiled-coil (CC; PLK4 binding) and STAN (PLK4 phosphorylated and SAS6 binding) domains are indicated. B. CDK1/CyclinB and PLK4 bind STIL at different stages. rGST-STIL and rPLX4 were added to CSF extracts which were kept arrested or released to interphase with Ca2+. GST-STIL was immunoprecipitated and samples were analyzed by WB. See Figure S5D and S5E. C. The STIL-CC motif is necessary for CDK1/CyclinB binding. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and CDK1 was immunoprecipitated. Samples were visualized by WB using the indicated antibodies. D. The STIL-CC motif is sufficient for CDK1/CyclinB binding. CDK1 was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells expressing GFP, GFP-CC or GFP-FL-STIL. Co-immunoprecipitates were probed with the indicated antibodies (n.s.= non-specific; cross reaction of the mouse anti-GFP antibody with rabbit IgGs used to IP CDK1). E. CDK1 binding to STIL prevents subsequent PLX4 binding. GST-N3CΔSTAN was incubated as indicated in the scheme, pulled-down, and its co-precipitated proteins were analyzed by WB. See Figure S6A and S6B for quantification (n=3) and titration experiments. F. CDK1 binding of STIL prevents its phosphorylation by PLX4. GST-STIL (FL) was incubated as shown in the scheme. STIL phosphorylation by PLX4 in the STAN motif was analyzed by WB using the indicated antibodies. See Figure S6C for more details on this experiment.

We then asked whether binding of CDK1/CyclinB to STIL would prevent STIL from interacting with PLK4. We performed CDK1/CyclinB immunoprecipitation from HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged-FL-STIL, or the truncated fragments: ΔCC, which does not bind PLK4 [7–10], and an N-terminal domain (N). We found that while CDK1/CyclinB binds FL-STIL and N-STIL, it does not bind ΔCC-STIL (Figure 6A, C). Despite this, ΔCC-STIL is phosphorylated by CDK1/CyclinB (Figure 5B); suggesting that in vitro phosphorylation and binding are not mutually dependent. More importantly, our results show that binding of CDK1/CyclinB to STIL requires the CC-domain of STIL.

We then asked whether the CC-domain is sufficient for CDK1/CyclinB binding. Immunoprecipitated CDK1 from HEK293T cell expressing GFP-CC [10] or GFP-FL STIL is able to efficiently bind both GFP-CC and GFP-FL (but not GFP alone) (Figure 6D). Our results demonstrate that the CC-domain is both necessary and sufficient for CDK1/CyclinB binding to STIL.

CDK1/CyclinB binds STIL preventing STIL-PLK4 complex formation and STIL phosphorylation by PLK4

Our results raise the intriguing possibility that CDK1/CyclinB and PLK4 may compete for binding to STIL. We tested this hypothesis using a GST-N3C-ΔSTAN-STIL fragment. Remarkably, we observed that although both proteins can interact separately with GST-N3C-ΔSTAN (Figure 6E, I and II, and Figure S6A), initial incubation of this fragment with CDK1/CyclinB, prevents PLX4 from binding to it (Figure 6E, III, and Figure S6A). Moreover, this assay was performed in the absence of ATP, reinforcing that binding and phosphorylation of STIL by CDK1/CyclinB might not be linked. Importantly, we observed that increasing concentrations of CDK1/CyclinB are able to physically displace a constant amount of PLK4 from binding STIL immunoprecipitated from Xenopus interphase extracts (Figure S6B).

Finally, we asked whether CDK1/CyclinB–STIL binding would also preclude STIL phosphorylation by PLK4 in the STAN motif, which is the critical event that recruits SAS6 [7, 8, 11]. We used FL-STIL and incubated it with PLK4 and CDK1/CyclinB individually or sequentially, and asked whether PLK4 can phosphorylate STIL in S1116 (Figure 6F). If PLK4 accesses STIL alone, or first, it is able to phosphorylate S1116 (Figure 6F, III). However, pre-incubation of CDK1/CyclinB precludes PLK4 phosphorylation (Figure 6F, IV). Previous reports indicated that PLK4 interaction with STIL, enhances PLK4’s activity [8]. Consistently, we observed that PLK4 auto-phosphorylation is reduced when its binding to STIL is disrupted by the presence of CDK1/CyclinB (see PPLK4 levels in Figure S6C, III vs. IV). In summary, we showed that CDK1/CyclinB prevents the STIL-PLK4 interaction by binding STIL in a kinase-independent fashion through the same region as PLK4. In turn, this prevents both the phosphorylation of STIL by PLK4, and further activation of PLK4. Given the low concentration of PLK4 in the cell [23], it is likely that CDK1/CyclinB is able to prevent PLK4’s binding to STIL in mitosis.

DISCUSSION

A critical ill-understood question in centriole biogenesis is how the cell division and centriole duplication cycles are coupled, so that centriole assembly occurs once and only once per cell cycle. Here we show how the first known biochemical event in centriole biogenesis, the association between PLK4 and its substrate STIL, is regulated during the cell cycle. We demonstrate that PLK4 activity is needed for centriole biogenesis before pro-centrioles become detectable in S-phase. PLK4 binds and phosphorylates STIL in mid-G1. We show that the major mitotic kinase, CDK1/CyclinB, prevents precocious PLK4-STIL complex assembly and STIL phosphorylation in mitosis, by binding to STIL in the same CC domain. These observations strongly support a model in which (see graphical abstract): i) in S phase and early G2 centriole reduplication is inhibited by centriole physical proximity, ii) in early mitosis centrioles are separated a critical distance for reduplication [18–20], and PLK4 and STIL levels are very high [15, 16]. However, CDK1/CyclinB prevents STIL from interacting with and being phosphorylated by PLK4, releasing it from the centriole [34], iii) after mitotic exit, following inactivation of CDK1, and new synthesis of STIL and PLK4 in mid-G1, PLK4 can bind and phosphorylate STIL [7–10, 35], iv) phosphorylated STIL recruits SAS6 [8, 9, 11] and new cartwheel formation starts at the G1/S boundary [12]. Our work provides a mechanistic link between cell cycle progression and centrosome biogenesis and a rationale for the observation that centriole biogenesis can only start after exit from mitosis.

Our model is supported by previous unexplained findings; inhibition of CDK1/CyclinB in Drosophila wing disc cells, Chinese Hamster Ovary cells (CHO) and chicken DT40 cells leads to unscheduled centriole formation [36, 37]. Moreover, previous work from our laboratory demonstrated that PLK4 overexpression can only drive de novo centriole biogenesis upon exit from meiosis in Drosophila eggs, suggesting that inhibition by CDK1/CyclinB in M phase could limit PLK4 activity in many contexts [21]. We note, however, that our model does not exclude additional roles of CDK1 in centriole biogenesis regulation through the activation or inhibition of additional regulators and/or substrates.

Remarkably, the results we present here can be paralleled with licensing mechanisms shown originally to operate in DNA replication and more recently, for centromere assembly (for a review on this topic, see ref. [38]) in certain aspects. In both cases, critical “licensing” events can only occur in G1. This is the loading of the helicase that unwinds the DNA onto the origins of replication, or the loading of the centromeric histone H3, CENP-A, to centromeres. CDK1 inactivates the licensing factor Cdt1, and binds to Orc6 [32, 33, 39], and also prevents loading of CENP-A in different ways [40]. Therefore, both in the case of DNA replication and centromere assembly, CDK1 prevents untimely interactions, ensuring those events occur only once per cell cycle. Assembly of the PLK4-STIL complex in G1, separated from centriole assembly in S-phase, can be thought as a sort of “licensing” event for centriole duplication, ensuring it occurs “once and only once” per cell cycle. Additional layers of regulation, such as centriole proximity [17, 18], clearly operate in addition to the mechanism we uncovered here to prevent unscheduled licensing in S and G2 phases.

Our results raise several important questions for understanding how centriole numbers are controlled. Whereas binding of CDK1/CyclinB to STIL requires an active CDK1/CyclinB complex, it is not phosphorylation dependent (Figure 6E), giving rise to the intriguing possibility that phosphorylation and binding could regulate independent aspects of STIL’s biology in the cell. Where is CDK1 binding STIL- is it to the cytoplasmic or the centrosome pool? Furthermore, how are degradation of STIL by the APC/C in mitotic exit [15, 34], and translation dynamics of new protein pools in G1 fine-tuned? Understanding those will explain why critical events start in mid-G1 and not immediately after CyclinB degradation. Finally, what role do CDK2/Cyclin complexes [41–45] play in regulating PLK4-STIL complex formation? Quantitative knowledge of the different pools of players, of their affinity to each other and of the regulatory mechanisms, will lead to a more cohesive understanding of the overarching principles governing the cell-cycle coordination of synchronously-occurring cellular processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid, cloning, protein expression and cell culture

The PLX4 and PLX4AS cDNAs were cloned into pFastBac HTb plasmid and expressed in SF21. HeLa cell lines were generated by electroporation of siRNA resistant cDNA of 3xFLAG-SBP-hPLK4AS/WT. HA-tagged FL-hSTIL, ΔCC, N-terminal (N) [7], and GFP-CC [10] were expressed in HEK293T. GST-N3C (ΔSTAN) was generated in a previous study [7]. Protein expression was performed as described previously [7].

Protein Detection

Cell lysis was performed in lysis buffer, 50–75 μg of protein were run on a 4–15% TGX gel (Bio-Rad), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted following standard protocols. Antibodies used for protein detection and immunofluorescence assays are specified in Supplementary Experimental Procedures. Polyclonal anti-PLX4 was generated in this study.

Preparation of Xenopus Egg Extracts and MTOC formation assay

CSF arrested and interphase egg extracts were prepared as previously described [46]. Purified PLX4AS was added to 20 μl of CSF extracts at 0.675 μM and released into interphase by calcium addition (20 mM CaCl2). MTOCs were analyzed by using TRITC-Rhodamine labeled porcine tubulin (Cytoskeleton catalogue #TL590M, lots #017).

Synchronization, Depletion, Induction and Inhibition Experiments in HeLa Cells

Depletion of endogenous PLK4 was performed using siRNA oligos (see table in Supp. Exp. Proc.). Expression of PLK4AS/WT was induced with tetracycline. 1-NA-PP1 was used to inhibit PLK4AS. 2 nM (17 hrs) thymidine (supplemented with 10 μM EdU or BrdU) was used for S-phase block, 100 ng/mL (12 hrs) nocodazole or 2.5 μM monastrol (14 hrs) were used for mitotic block. G1 time-points were obtained by mitotic shake-off.

Immunoprecipitation and Kinase Assays

Immunoprecipitated STIL was washed with RIPA, and co-precipitated proteins were separated on a 4–15% TGX SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad). Kinase reaction was performed in kinase buffer supplemented with ATPγS and myelin basic protein (MBP). Radioactive kinase reactions were performed in the presence of 1 μCi [γ-32P] ATP (replenishing ATP between kinases in the case of sequential incubations). For phosphorylation assays, GST-hSTIL (FL) [8] or immunoprecipitated STIL were incubated in kinase buffer supplemented with 500 ng CDK1/CyclinB and/or 500 ng of PLK4. For sequential incubation; GST-N3C (ΔSTAN) was incubated in binding buffer containing 500 ng of CDK1/Cyclin, washed, subsequently incubated with 500 ng of GFP-PLX4, and eluted in Laemmli buffer. Assays were analyzed by Coomassie staining, autoradiography or western blotting.

For immunoprecipitation from human cells 1–2 mg of total whole-cell lysate was incubated with protein-G coupled to the appropriate antibody, washed, and eluted in Laemmli buffer.

Immunofluorescence assays, Microscopy and Flow cytometry analysis

Staining with 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine was performed using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Propidium iodide, or bromodeoxy-Uridine staining were analyzed on a BD FACScan flow cytometer. Data were plotted and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.). Images were collected on a DeltaVision microscope (Applied Precision) using softWoRx (Applied Precision software) or a Spinning Disk CSU-X1 (Yokogawa) confocal scan head coupled to a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E and controlled using MetaMorph 7.5 (Molecular Devices). GraphPad Prism (version 5.0c, La Jolla, California, USA) was used for statistical analyses and plotting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to L. Jansen and M Godinho, A. Stankovic for discussions and sharing unpublished protocols. We are also grateful to K Crnokic, F Nedelec, D Needleman, I Vernos, C Field, T Mitchison, T Stearns, J Pines, C Waterman, P Marco, S Lens, R Hengeveld, S Werner, K Dores, G Marteil, Z Lygerou, J Loncarek, C Lopes, J Hutchins, K Oegema and T Mayer for sharing reagents and helpful discussions. The EMBO YIP and short-term visit programs supported several visits to EMBL. S.Z is funded by FCT (EXPL/BIM-ONC/0830/2013). M.E.F is funded by EMBO. M.B-D. laboratory is supported by an EMBO installation grant, an ERC grant ERC-2010-StG-261344 and FCT grants: FCT-investigator, EXPL/BIM-ONC/0830/2013 and PTDC/SAU-BD/105616/2008.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.Z. and M.E.F performed most cellular and biochemical assays. S.Z. performed most Xenopus experiments with participation of F.L., S.G. and P.D. C.N., D.B., M.L.F and S.G participated in identifying Shokat mutants and making cell lines. T.M., A.H., S.K.L., M.O., D.K., and T.L. provided reagents. T.L. and E.K. provided expertise on Xenopus work. S.Z., M.E.F. and M.B.-D devised all experiments. S.Z., M.E.F., M.L.F. and M.B.-D. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and discussed the manuscript.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bettencourt-Dias M, Glover DM. Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:451–463. doi: 10.1038/nrm2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khodjakov A, Rieder CL, Sluder G, Cassels G, Sibon O, Wang C-L. De novo formation of centrosomes in vertebrate cells arrested during S phase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1171–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zitouni S, Nabais C, Jana SC, Guerrero A, Bettencourt-Dias M. Polo-like kinases: structural variations lead to multiple functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:433–452. doi: 10.1038/nrm3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bettencourt-Dias M, Rodrigues-Martins A, Carpenter L, Riparbelli M, Lehmann L, Gatt MK, Carmo N, Balloux F, Callaini G, Glover DM. SAK/PLK4 is required for centriole duplication and flagella development. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2199–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habedanck R, Stierhof Y-D, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA. The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1140–1146. doi: 10.1038/ncb1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim T-S, Park J-E, Shukla A, Choi S, Murugan RN, Lee JH, Ahn M, Rhee K, Bang JK, Kim BY, et al. Hierarchical recruitment of Plk4 and regulation of centriole biogenesis by two centrosomal scaffolds, Cep192 and Cep152. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4849–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319656110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohta M, Ashikawa T, Nozaki Y, Kozuka-hata H, Goto H, Inagaki M, Oyama M, Kitagawa D. Direct interaction of Plk4 with STIL ensures formation of a single procentriole per parental centriole. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer T, Clutario KM, Lambrus BG, Daggubati V, Holland AJ. Binding of STIL to Plk4 activates kinase activity to promote centriole assembly. J Cell Biol. 2015 Jun;22:863–78. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kratz AS, Barenz F, Richter KT, Hoffmann I. Plk4-dependent phosphorylation of STIL is required for centriole duplication. Biol Open. 2015 doi: 10.1242/bio.201411023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arquint C, Gabryjonczyk AM, Imseng S, Böhm R, Sauer E, Hiller S, Nigg EA, Maier T. STIL binding to Polo-box 3 of PLK4 regulates centriole duplication. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzhindzhev NS, Tzolovsky G, Lipinszki Z, Schneider S, Lattao R, Fu J, Debski J, Dadlez M, Glover D. Plk4 phosphorylates Ana2 to trigger Sas6 recruitment and procentriole formation. Curr Biol. 2014 Nov 3;24:2526–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonczy P. Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:425–435. doi: 10.1038/nrm3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu J, Hagan IM, Glover DM. The Centrosome and Its Duplication Cycle. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015:1–36. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leidel S, Delattre M, Cerutti L, Baumer K, Gonczy P. SAS-6 defines a protein family required for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and in human cells Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:115–125. doi: 10.1038/ncb1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arquint C, Sonnen KF, Stierhof Y-D, Nigg EA. Cell-cycle-regulated expression of STIL controls centriole number in human cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1342–1352. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sillibourne JE, Tack F, Vloemans N, Boeckx A, Thambirajah S, Bonnet P, Ramaekers FCS, Bornens M, Grand-Perret T. Autophosphorylation of PLK4 and Its Role in Centriole Duplication. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:547–561. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsou MFB, Stearns T. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. 2006;442:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nature04985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shukla Anil, Kong Dong, Sharma Meena, Magidson Valentin, Loncarek Jadranka. Plk1 relieves centriole block to reduplication by promoting daughter centriole maturation. Nat Commun. 2015 Aug 21; doi: 10.1038/ncomms9077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazia D, Harris P, Bibring T. The Multiplicity of the Mitotic Centers and the Time-Course of Their Duplication and Separation. J Physic Biochem Cytol. 1960;7 doi: 10.1083/jcb.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sluder G, Rieder CL. Centriole number and the reproductive capacity of spindle poles. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:887–896. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigues-Martins A, Riparbelli M, Callaini G, Glover DM, Bettencourt-Dias M. Revisiting the role of the mother centriole in centriole biogenesis. Science. 2007;316:1046–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.1142950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckerdt F, Yamamoto TM, Lewellyn AL, Maller JL. Identification of a polo-like kinase 4-dependent pathway for de novo centriole formation. Curr Biol. 2011;21:428–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakobsen L, Vanselow K, Skogs M, Toyoda Y, Lundberg E, Poser I, Falkenby LG, Bennetzen M, Westendorf J, Nigg EA, et al. Novel asymmetrically localizing components of human centrosomes identified by complementary proteomics methods. EMBO J. 2011;30:1520–1535. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai A, Murray A, Mitchison TJ, Walczak C. The use of Xenopus egg extracts to study mitotic spindle assembly and function in vitro. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;61:385–412. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61991-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokmakov AA, Iwasaki T, Sato KI, Fukami Y. Analysis of signal transduction in cell-free extracts and rafts of Xenopus eggs. Methods. 2010;51:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop AC, Ubersax JA, Petsch DT, Matheos DP, Gray NS, Blethrow J, Shimizu E, Tsien JZ, Schultz PG, Rose MD, et al. A chemical switch for inhibitor-sensitive alleles of any protein kinase. Nature. 2000;407:395–401. doi: 10.1038/35030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland AJ, Lan W, Niessen S, Hoover H, Cleveland DW. Polo-like kinase 4 kinase activity limits centrosome overduplication by autoregulating its own stability. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:191–198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hengeveld RCC, Hertz NT, Vromans MJM, Zhang C, Burlingame AL, Shokat KM, Lens SMA. Development of a Chemical Genetic Approach for Human Aurora B Kinase Identifies Novel Substrates of the Chromosomal Passenger Complex. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:47–59. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop aC, Shah K, Liu Y, Witucki L, Kung C, Shokat KM. Design of allele-specific inhibitors to probe protein kinase signaling. Curr Biol. 1998;8:257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong YL, Anzola JV, Davis RL, Yoon M, Motamedi A, Kroll A, Seo CP, Hsia JE, Kim SK, Mitchell JW, Mitchell BJ, Desai A, Gahman TC, Shiau AK, Oegema K. Reversible centriole depletion with an inhibitor of Polo-like kinase 4. Science (80- ) 2015 Jun;5:1155–60. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vassilev LT. Cell cycle synchronization at the G2/M phase border by reversible inhibition of CDK1. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2555–2556. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.22.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen VQ, Co C, Li JJ. Cyclin-dependent kinases prevent DNA re replication through multiple mechanisms. Nature. 2001;411:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/35082600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, Bell SP. CDK prevents Mcm2-7 helicase loading by inhibiting Cdt1 interaction with Orc6. Genes Dev. 2011;25:363–372. doi: 10.1101/gad.2011511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arquint C, Nigg EA. STIL microcephaly mutations interfere with APC/C-mediated degradation and cause centriole amplification. Curr Biol. 2014;24:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dzhindzhev NS, Yu QD, Weiskopf K, Tzolovsky G, Cunha-Ferreira I, Riparbelli M, Rodrigues-Martins A, Bettencourt-Dias M, Callaini G, Glover DM. Asterless is a scaffold for the onset of centriole assembly. Nature. 2010;467:714–718. doi: 10.1038/nature09445. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vidwans SJ, Wong ML, O’Farrell PH. Anomalous centriole configurations are detected in Drosophila wing disc cells upon Cdk1 inactivation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:137–143. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steere N, Wagner M, Beishir S, Smith E, Breslin L, Morrison CG, Hochegger H, Kuriyama R. Centrosome amplification in CHO and DT40 cells by inactivation of cyclin-dependent kinases. Cytoskeleton. 2011;68:446–458. doi: 10.1002/cm.20523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McIntosh D, Blow JJ. Dormant origins, the licensing checkpoint, and the response to replicative stresses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enserink JM, Kolodner RD. An overview of Cdk1-controlled targets and processes. Cell Div. 2010;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva MCC, Bodor DL, Stellfox ME, Martins NMC, Hochegger H, Foltz DR, Jansen LET. Cdk Activity Couples Epigenetic Centromere Inheritance to Cell Cycle Progression. Dev Cell. 2012;22:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kodani A, Yu TW, Johnson JR, Jayaraman D, Johnson TL, Al-Gazali L, Sztriha L, Partlow JN, Kim H, Krup AL, Dammermann A, Krogan N, Walsh CA, Reiter JF. Centriolar satellites assemble centrosomal microcephaly proteins to recruit CDK2 and promote centriole duplication. Elife. 2015;10:7554. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koff A, Giordano A, Desai D, Yamashita K, Harper JW, Elledge S, Nishimoto T, Morgan DO, Franza BR, Roberts JM. Formation and activation of a cyclin E-cdk2 complex during the G1 phase of the human cell cycle. Science. 1992;257:1689–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.1388288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meraldi P, Lukas J, Fry AM, Bartek J, Nigg EA. Centrosome duplication in mammalian somatic cells requires E2F and Cdk2-cyclin A. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:88–93. doi: 10.1038/10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinchcliffe EH, Li C, Thompson EA, Maller JL, Sluder G. Requirement of Cdk2-cyclin E activity for repeated centrosome reproduction in Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 1999;283:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto Y, Hayashi K, Nishida E. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) is required for centrosome duplication in mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 1999;9:429–432. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lorca T, Bernis C, Vigneron S, Burgess A, Brioudes E, Labbe J-C, Castro A. Constant regulation of both the MPF amplification loop and the Greatwall-PP2A pathway is required for metaphase II arrest and correct entry into the first embryonic cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2281–2291. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.