Abstract

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) diagnosed by electrocardiography (ECG-LVH) and echocardiography (echo-LVH) are independently associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. However, it is unknown if ECG-LVH retains its predictive properties independent of left ventricular anatomy. We compared the risk of CVD associated with ECG-LVH and echo-LVH in 4,076 participants (41% male, 86% white) from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), who were free of baseline CVD. ECG-LVH was defined with Minnesota ECG Classification criteria from baseline ECG data. Echo-LVH was defined by sex-specific left ventricular mass values normalized to body surface area (male: >102 g/m2; female: >88 g/m2). ECG-LVH was detected in 144 (3.5%) participants and echo-LVH in 430 (11%) participants. Over a median follow-up of 10.6 years, 2,274 CVD events occurred. In a multivariable Cox regression analysis adjusted for common CVD risk factors, ECG-LVH (HR=1.84, 95%CI=1.51, 2.24) and echo-LVH (HR=1.35, 95%CI=1.19, 1.54) were associated with an increased risk for CVD events. The association between ECG-LVH and CVD events was not substantively altered with further adjustment for echo-LVH (HR=1.76, 95%CI=1.45, 2.15). In conclusion, the association of ECG-LVH with CVD events is not dependent on echo-LVH. This finding provides support to the concept that ECG-LVH is an electrophysiologic marker with predictive properties independent of left ventricular anatomy.

Keywords: left ventricular hypertrophy, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, cardiovascular disease

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) diagnosed by electrocardiography (ECG-LVH) and echocardiography (echo-LVH) have both been independently associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events1–6. When combined with imaging modalities, ECG-LVH has variable success in predicting CVD events after controlling for LVH7,8. However, it is uncertain if the CVD risk associated with ECG-LVH is comparable to the risk associated with echo-LVH, and if ECG-LVH retains its predictive properties independent of left ventricle (LV) anatomy. Therefore, we compared the predictive abilities of ECG-LVH and echo-LVH for future CVD events in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), and also determined if the predictive abilities of ECG-LVH were dependent on LV mass (LVM).

METHODS

Details of CHS have been previously described 9. Briefly, CHS is a prospective population-based cohort study of risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke in individuals 65 years and older. A total of 5,888 participants with Medicare eligibility were recruited from 4 field centers located in the following locations in the United States: Forsyth County, NC; Sacramento County, CA; Washington County, MD; and Pittsburgh, PA. Subjects were followed with semi-annual contacts, alternating between telephone calls and surveillance clinic visits. CHS clinic exams ended in June of 1999 and since that time 2 yearly phone calls to participants were used to identify events and collect data. The institutional review board at each site approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from participants at enrollment. Participants were excluded if any of the following criteria were met: baseline CVD was present, baseline covariate data were missing, QRS duration ≥120 ms, or follow-up data were missing. A total of 4,076 participants (41% male; 86% white) with complete baseline data were used in this analysis.

LVH was determined from the baseline ECG or echocardiogram. Identical electrocardiographs (MAC PC, Marquette Electronics Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin) were used at all clinic sites, and resting, 10-second standard simultaneous 12-lead ECGs were recorded in all participants10. All ECGs were processed in a central laboratory (initially at Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada and later at the Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC). ECG-LVH was defined by Minnesota ECG Code 3 11. In a sensitivity analysis, we also used Cornell voltage LVH. A baseline echocardiogram was obtained for each study participant according to previously described techniques12. All measurements were read at a central echocardiography reading center. Measurements were made from digitized images using an off-line image-analysis system equipped with customized computer algorithms. LVM was derived from standard formulas described by Devereux et al13. Echo-LVH was defined by sex-specific LVM normalized to body surface area (male: >102 g/m2; female: >88 g/m2)14.

The ascertainment and adjudication of baseline and incident cases of CVD events in CHS have been previously described15–17. For this analysis, CVD was defined as the development of the composite of the following events: coronary heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure. Adjudicated incident coronary heart disease events were defined as one of the following: fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction, angina pectoris without myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization procedures (angioplasty and coronary artery bypass graft surgery), or other fatal coronary heart disease events. All suspected stroke events and stroke-related deaths were reviewed by the Cerebrovascular Adjudication Committee and included fatal and non-fatal events and subtypes classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic. Heart failure events were determined from both the physician diagnosis and/or treatment defined by a current prescription for typical therapies (e.g., diuretics, digitalis, and vasodilators). Additionally, typical symptoms, signs, and chest X-ray findings of heart failure were reviewed by the CHS Events Committee. Probable and definite heart failure cases were included.

Participant characteristics were collected during the initial CHS interview and questionnaire. Age, sex, race, income, education, and smoking status were self-reported. Annual income was dichotomized at $25,000 and education was dichotomized at “high school or less.” Smoking was defined as current or ever smoker. Participants’ blood samples were obtained after a 12-hour fast at the local field center. Diabetes was defined as self-reported history of a physician diagnosis, a fasting glucose value ≥126 mg/dL, or by the current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications. Blood pressure was measured for each participant in the seated position and systolic measurements were used in this analysis. The use of aspirin and antihypertensive medications were self-reported. Hypertension was defined as a baseline blood pressure ≥140/90 or by the use of antihypertensive medications. Body mass index was computed as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage while continuous variables were recorded as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance for categorical variables was tested using the chi-square method and the student’s t-test for continuous variables. Comparisons were examined between participants with and without ECG-LVH and echo-LVH, separately. We examined the association between ECG-LVH and echo-LVH at baseline with incident CVD events. Follow-up time was defined as the time from the initial study exam until one of the following: CVD development, death, loss to follow-up, or end of follow-up (December 31, 2010). Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to compute cumulative incidence of CVD by ECG-LVH and echo-LVH and the differences in estimates were compared using the log-rank procedure18. Cox regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between ECG-LVH and echo-LVH and incident CVD, separately. Additionally, we examined the association of either ECG-LVH or echo-LVH to define LVH to determine the combined effect of both modalities regarding CVD risk assessment. Multivariate models were constructed as follows: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and income; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus body mass index, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, smoking, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, aspirin, and antihypertensive medications. To determine how much of the observed risk of CVD associated with ECG-LVH was explained by echo-LVH, we used a third model (Model 3) with covariates from Model 2 plus echo-LVH. A sensitivity analysis also was performed using covariates from Model 2 and LVM as a continuous variable. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated in our analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

ECG-LVH was detected in 144 (3.5%) participants and echo-LVH was present in 199 (4.9%) participants. Forty-eight participants had both ECG-LVH and echo-LVH. Baseline characteristics stratified by ECG-LVH and echo-LVH are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (N=4,076)

| Characteristic | ECG-LVH (n=144) | No ECG-LVH (n=3,932) | P-value* | Echo-LVH (n=430) | No Echo-LVH (n=3,646) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 65–70 | 39 (27%) | 1,843 (47%) | 149 (35%) | 1,733 (48%) | ||

| 71–74 | 27 (19%) | 944 (24%) | 98 (23%) | 873 (24%) | ||

| 75–80 | 52 (36%) | 808 (21%) | 120 (28%) | 740 (20%) | ||

| >80 | 26 (18%) | 337 (8.0%) | <0.0001 | 63 (14%) | 300 (8.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 59 (41%) | 1,492 (38%) | 0.46 | 101 (23%) | 1,450 (40%) | <0.0001 |

| White | 100 (69%) | 3,388 (86%) | <0.0001 | 398 (93%) | 3,090 (85%) | <0.0001 |

| High school or less | 82 (57%) | 2,213 (56%) | 0.87 | 272 (63%) | 2,023 (55%) | 0.0021 |

| Income <$25,000 | 102 (71%) | 2,435 (62%) | 0.030 | 298 (69%) | 2,239 (61%) | 0.0014 |

| Ever smoker | 67 (47%) | 2,063 (52%) | 0.16 | 173 (40%) | 1,957 (54%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (15%) | 532 (14%) | 0.54 | 95 (22%) | 459 (13%) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 26 ± 3.7 | 26 ± 4.1 | 0.97 | 28 ± 4.1 | 26 ± 4.0 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mean ± SD, mm Hg | 154 ± 23 | 138 ± 20 | <0.0001 | 146 ± 20 | 138 ± 20 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 209 ± 38 | 213 ± 39 | 0.30 | 215 ± 40 | 212 ± 39 | 0.081 |

| HDL cholesterol (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 56 ± 16 | 56 ± 16 | 0.93 | 54 ± 15 | 56 ± 16 | 0.020 |

| Hypertension | 125 (87%) | 2,435 (62%) | <0.0001 | 344 (80%) | 2,216 (61%) | <0.0001 |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 94 (65%) | 1,486 (38%) | <0.0001 | 235 (55%) | 1,345 (37%) | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin use | 49 (34%) | 1,105 (28%) | 0.12 | 127 (30%) | 1,027 (28%) | 0.55 |

Statistical significance for continuous data was tested using the student’s t-test and categorical data was tested using the chi-square test.

ECG-LVH=electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; echo-LVH=echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; SD=standard deviation.

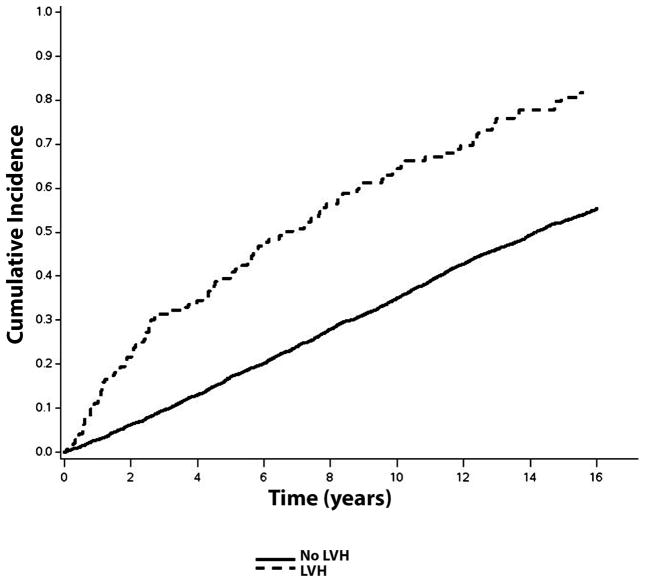

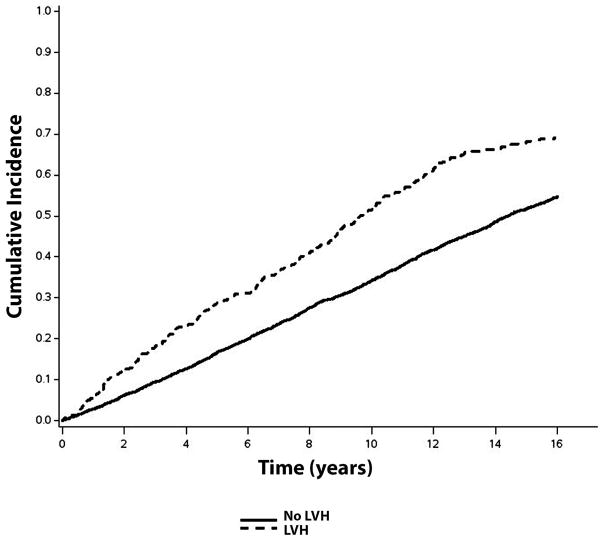

Over a median follow-up of 10.6 years, a total of 2,274 (56%; incidence rate=50.0 per 1000 person-years) CVD events occurred. CVD events occurred. CVD events were more common in individuals with ECG-LVH (incidence rate=108.2 per 1000 person-years) and echo-LVH (incidence rate=75.8 per 1000 person-years) compared with those without LVH. The unadjusted cumulative incidence curves of CVD events by ECG-LVH and echo-LVH are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease by ECG-LVH*

*The cumulative incidence curves are statistically different (log-rank p<0.0001).

ECG-LVH=electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease by echo-LVH*

*The cumulative incidence curves are statistically different (log-rank p=0.0004).

echo-LVH=echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy.

In a multivariable Cox regression analysis, ECG-LVH and echo-LVH were associated with an increased risk for CVD events (Table 2). The association between ECG-LVH and CVD events was not materially altered after inclusion of echo-LVH in the model (Table 2). A similar result was observed with LVM as a continuous variable (HR=1.74, 95%CI=1.42, 2.13).

Table 2.

Risk of Cardiovascular Disease*

| Events/No. at risk | Model 1† HR (95%CI) | P-value | Model 2‡ HR (95%CI) | P-value | Model 3δ HR (95%CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECG | |||||||

| No LVH | 2,161/3,932 | 1.0 | - | 1.0 | - | 1.0 | - |

| LVH | 113/144 | 2.18 (1.80, 2.65) | <0.0001 | 1.84 (1.51, 2.24) | <0.0001 | 1.76 (1.45, 2.15) | <0.0001 |

| Echocardiogram | |||||||

| No LVH | 1,983/3,646 | 1.0 | - | 1.0 | - | - | - |

| LVH | 291/430 | 1.61 (1.42, 1.82) | <0.0001 | 1.35 (1.19, 1.54) | <0.0001 | - | - |

| ECG or Echocardiogram | |||||||

| No LVH | 1,907/3,550 | 1.0 | - | 1.0 | - | - | - |

| LVH | 367/526 | 1.70 (1.52, 1.91) | <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.28, 1.62) | <0.0001 | - | - |

Cardiovascular disease defined as the composite of myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, congestive heart failure, angioplasty, coronary artery bypass surgery, or coronary heart disease death.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and income.

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus body mass index, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, smoking, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, aspirin, and antihypertensive medications.

Adjusted for Model 2 covariates plus echo-LVH.

ECG=electrocardiogram; echo-LVH=echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy.

Similar results were obtained when LVH by Cornell voltage was used instead of LVH by Minnesota code. The multivariable HR for Cornell voltage was 1.46 (95%CI=1.19, 1.78), which remained significant after accounting for echo-LVH (HR=1.25, 95%CI=1.01, 1.56).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis from CHS, both ECG-LVH and echo-LVH were shown to be predictive of future CVD events after accounting for well-known CVD risk factors. The predictive ability of ECG-LVH did not depend on echo-LVH, suggesting that ECG-LVH is an important electrophysiologic marker of cardiac abnormalities independent of LV anatomy.

LVH by imaging is useful in the prediction of CVD events19. However, important prognostic information regarding CVD risk assessment can still be obtained from ECG-LVH. Our study demonstrates that the ability of ECG-LVH to predict future CVD events does not depend on structural abnormalities. This finding suggests that the electrophysiological abnormalities detected with ECG-LVH are important to the prediction of CVD events.

In this analysis, we defined ECG-LVH using Minnesota code criteria. The Minnesota code classification system has been used for ECG classification in studies for the past 3 decades20. Additionally, ECG-LVH detected using these criteria have been shown to predict future CVD events across numerous studies and populations21–23. There are many other validated ECG-LVH criteria. However, the current ECG interpretation guidelines do not favor or recommend one over the other 24, and our results were similar when we used Cornell voltage.

LVH is usually associated with increased voltage. However QRS changes in LVH can also include prolonged QRS, left axis deviation, left anterior fascicular block, and left bundle block-like patterns25. While it had previously been believed that changes in the QRS complex were associated with an increased LVM, studies have shown that the changes are due to a combination of anatomical and electrical remodeling26. In contrast, echo-LVH is a measurement soley of LVM27. While ECG-LVH and echo-LVH do not detect identical pathology, useful information is obtained from both methods. Due to the important prognostic information that is obtained from the ECG, this tool provides clinicians with a valuable tool to assess CVD risk, especially in facilities with limited resources. Additionally, ECG-LVH can reliably be used as a prognostic marker in epidemiologic studies where large-scale echocardiography is not feasible.

Several limitations should be noted. CHS is a predominately white cohort and this limits the generalizability of our findings to other races. Several baseline characteristics were self-reported and possibly subjected our analysis to recall bias. We grouped several CVD outcomes into one category, and it is possible that the results will vary by each outcome. However, our results provide exploratory evidence that ECG-LVH provides prognostic information independent of LVM and provides a framework for further investigation. Lastly, we included several covariates in our multivariable models, but acknowledge that residual confounding remains a possibility.

Acknowledgments

This Manuscript was prepared using CHS Research Materials obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the CHS or the NHLBI.

J. Adam Leigh is supported with NIH Grant T32 HL076132

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bikkina M, Levy D, Evans JC, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, Castelli WP. Left ventricular mass and risk of stroke in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;272:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Left Ventricular Mass and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in an Elderly Cohort The Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:101–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-2-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Salomon M, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Prognostic implications of baseline electrocardiographic features and their serial changes in subjects with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1994;90:1786–1793. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, O’Leary DH, Price TR Group for the CCR. Short-term Predictors of Incident Stroke in Older Adults The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1996;27:1479–1486. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Belanger AJ, Wilson PW, Levy D. Profile for estimating risk of heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1197–1204. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.11.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrispin J, Jain A, Soliman EZ, Guallar E, Alonso A, Heckbert SR, Bluemke DA, Lima JAC, Nazarian S. Association of electrocardiographic and imaging surrogates of left ventricular hypertrophy with incident atrial fibrillation: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2007–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain A, Tandri H, Dalal D, Chahal H, Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR, Lima JAC, Bluemke DA. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of electrocardiography for left ventricular hypertrophy defined by magnetic resonance imaging in relationship to ethnicity: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am Heart J. 2010;159:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furberg CD, Manolio TA, Psaty BM, Bild DE, Borhani NO, Newman A, Tabatznik B, Rautaharju PM. Major electrocardiographic abnormalities in persons aged 65 years and older (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91231-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prineas RJ, Crow RS, Blackburn HW. The Minnesota code manual of electrocardiographic findings : standards and procedures for measurement and classification. 2. London: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, Klopfenstein HS, Smith VE, Tabatznik B, Siscovick D, Lobodzinski S, Anton-Culver H, Manolio TA. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free-living elderly subjects: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt J-U. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–270. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–277. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price TR, Psaty B, O’Leary D, Burke G, Gardin J. Assessment of cerebrovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:504–507. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90105-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray RJ, Tsiatis AA. A linear rank test for use when the main interest is in differences in cure rates. Biometrics. 1989;45:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong AC, Jacobs DR, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Gjesdal O, Lewis CE, Bibbins-Domingo K, Sidney S, Schreiner PJ, Williams OD, Goff DC, Liu K, Lima JAC. Framingham score and LV mass predict events in young adults: CARDIA study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Guercio R, De Buono AF, Leonardo G, Cotticelli G, Niglio A, Gentile S. Evaluation by the Minnesota Code of the electrocardiographic changes in patients over 70. Cardiologia. 1983;28:619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estes EH, Zhang Z-M, Li Y, Tereschenko LG, Soliman EZ. The Romhilt-Estes left ventricular hypertrophy score and its components predict all-cause mortality in the general population. Am Heart J. 2015;170:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jørgensen PG, Jensen JS, Marott JL, Jensen GB, Appleyard M, Mogelvang R. Electrocardiographic changes improve risk prediction in asymptomatic persons age 65 years or above without cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:898–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gencer B, Butler J, Bauer DC, Auer R, Kalogeropoulos A, Marques-Vidal P, Applegate WB, Satterfield S, Harris T, Newman A, Vittinghoff E, Rodondi N Health ABC Study. Association of electrocardiogram abnormalities and incident heart failure events. Am Heart J. 2014;167:869–875.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Kligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Gorgels A, Josephson M, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mason JW, Pahlm O, Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, van Herpen G, Wagner GS, Wellens H American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacharova L, Szathmary V, Potse M, Mateasik A. Computer simulation of ECG manifestations of left ventricular electrical remodeling. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:630–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bacharova L, Szathmary V, Kovalcik M, Mateasik A. Effect of changes in left ventricular anatomy and conduction velocity on the QRS voltage and morphology in left ventricular hypertrophy: a model study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong AC, Gjesdal O, Almeida A, Nacif M, Wu C, Bluemke DA, Brumback L, Lima JAC. Left ventricular mass and hypertrophy by echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Echocardiography. 2014;31:12–20. doi: 10.1111/echo.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]