Abstract

Purpose

The present study offers novel insights into the molecular circuitry of accelerated in vivo tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells. Therapeutic vulnerability of Notch2-altered growth to a small molecule (withaferin A; WA) is also demonstrated.

Methods

MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells were used for the xenograft studies. A variety of technologies were deployed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying tumor growth augmentation by Notch2 knockdown and its reversal by WA, including Fluorescence Molecular Tomography for measurement of tumor angiogenesis in live mice, Seahorse Flux analyzer for ex vivo measurement of tumor metabolism, proteomics, and Luminex-based cytokine profiling.

Results

Stable knockdown of Notch2 resulted in accelerated in vivo tumor growth in both cells reflected by tumor volume and/or latency. For example, the wet tumor weight from mice bearing Notch2 knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells was about 7.1-fold higher compared with control (P < 0.0001). Accelerated tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown was highly sensitive to inhibition by a promising steroidal lactone (WA) derived from a medicinal plant. Molecular underpinnings for tumor growth intensification by Notch2 knockdown included compensatory increase in Notch1 activation, increased cellular proliferation and/or angiogenesis, and increased plasma or tumor levels of growth stimulatory cytokines. WA administration reversed many of these effects providing explanation for its remarkable anti-cancer efficacy.

Conclusions

Notch2 functions as a tumor growth suppressor in TNBC and WA offers a novel therapeutic strategy for restoring this function.

Keywords: Notch2, breast cancer, cytokines, withaferin A, chemoprevention

Introduction

Signaling coordinated by the Notch family receptors and their ligands is known to influence key developmental processes including differentiation and cell-fate decisions [1]. The Notch signaling in humans comprises of four receptors (Notch1-Notch4) and five ligands [Delta-like (DLL)1, DLL3, DLL4, Jagged1, and Jagged2] [1, 2]. Despite an overall structural similarity, the Notch family receptors are distinguished by the number of epidermal growth factor repeats in the ectodomain (e.g., 36 in Notch1 and Notch2 versus 29 in Notch4) as well as structure of the cytoplasmic transactivation domain [2, 3]. Cellular signal from Notch is transmitted after interaction of the receptor with ligand from an adjoining cell leading to two sequential proteolytic cleavages culminating with nuclear translocation of the cleaved protein for regulation of gene expression [2, 3]. Transcriptional targets of Notch include basic-helix-loop-helix transcriptional repressor HES (hairy enhancer of split), cyclin D1, and Myc to name a few [4, 5].

A causative role for Notch1 in cancer was initially suggested in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [6]. However, a review of the existing literature suggests that individual Notch receptors may either promote tumorigenesis or function as a tumor suppressor [7]. For example, Notch1 ablation in Pdx1-Cre mice with conditional oncogenic KrasG12D resulted in formation of skin papilloma with propensity for progression to squamous cell carcinoma [8]. At the same time, Notch1 seems to be oncogenic in leukemia as well as solid tumors, including breast cancer [7].

Study of the role of individual Notch receptors in breast cancer, which is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women globally [9], continues to be a topic of intense research. Studies have consistently indicated an oncogenic role for Notch1, Notch3, and Notch4 in breast cancer [7, 10–12]. For example, overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 resulted in blockade of normal mammary gland development but induction of breast cancer in transgenic mice [10]. However, the role of Notch2 in breast cancer is poorly understood. In cultured breast cancer cells, stable or transient knockdown of Notch2 resulted in inhibition of cell migration and cancer stem cell population suggesting an oncogenic role for this protein [13–16]. To the contrary, stable overexpression of intracellular domain of Notch2 (active form) in MDA-MB-231 cells caused inhibition of tumor xenograft growth in vivo [17]. Another study suggested higher chance of survival in breast cancer patients with overexpression of Notch2 [18].

The present study was undertaken to probe into the role of Notch2 in breast cancer growth using in vivo xenograft models of MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells. An additional objective was to determine in vivo sensitivity of Notch2-altered tumor growth to a highly promising cancer chemopreventative small molecule (withaferin A; WA) derived from a medicinal plant (Withania somnifera) [19]. We have shown previously that WA administration prevents breast cancer development in a transgenic mouse model [20].

Materials and methods

Reagents

WA (purity 95.6%) was purchased from ChromaDex (Irvine, CA). Female athymic mice (5–6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Female SCID mice (6-week old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Antibodies against Ki-67, CD31, and Notch1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); antibodies against cleaved Notch1, Notch2, protein disulfide-isomerase (PDI) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); an antibody specific for cleaved Notch2 was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA); and an antibody against inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 (IMPDH2) was from GeneTex (Irvine, CA). ApopTag® Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis kit for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was purchased from EMD Millipore.

Xenograft study

Use and care of mice was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Animal Care and Use Committee. The MDA-MB-231 cell line (mutant p53 but wild-type PI3K) was purchased from the American Type Culture collection (Manassas, VA) and authenticated by us in February 2012. The authenticated SUM159 (mutant p53 and H1047L mutation in PI3K) cell line was purchased from Asterand Bioscience (Detroit, MI). Based on our past experience with MDA-MB-231 xenografts [21], it was estimated that a sample size of n = 6 (with tumor cells injected on both flanks of each mouse) can provide a power of 80% to detect a 17% difference in growth rate. Mice were acclimated for 1 week prior to being placed on irradiated AIN-76A diet. Exponentially growing MDA-MB-231 cells stably transfected with control shRNA or Notch2-targeted shRNA (1×106 cells in 0.1 mL media) were subcutaneously injected on both flanks of each mouse when they were 9–10 weeks old. On the day of tumor cell implantation, mice were randomized into 4 groups (n = 6) and treatment was started with intraperitoneal injection of either 100 µg WA/mouse in 100 µL vehicle [10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 40% Cremophor EL: Ethanol (3:1), and 50% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] or vehicle alone. Treatment was given on Monday through Friday of each week for a total of 7.5 weeks. Because tumors did not grow in some mice, the number of evaluable tumors at the study conclusion was n = 8 for Control sh-Veh, n = 6 for Control sh-WA, n = 9 for Notch2-Veh, and n = 12 for the Notch2 sh-WA. Because of tumor burden and morbidity, three mice of Notch2 sh-Veh group were sacrificed on day 47. For the SUM159 xenograft study, female SCID mice were acclimated for 1 week and then placed on irradiated AIN-76A diet. Exponentially growing (3×106 cells per 0.1 mL suspension in 50% PBS and 50% Matrigel) SUM159 cells stably transfected with Notch2-targeted shRNA or control shRNA were subcutaneously injected on both flanks of mice. At sacrifice (on day 45 after cell injection), all mice had tumors on both sides except that one mouse from the Control sh group had tumor only on one side.

Immunohistochemistry and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

Details of TUNEL assay can be found in our prior publications [20, 22, 23]. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described by us previously [20]. Briefly, sections were quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocked with normal goat serum in tris-buffered saline. Sections were incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with the desired primary antibodies and washed with tris-buffered saline at room temperature. The sections were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody. A characteristic brown color was developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine. Stained sections were examined under a Leica DC300F microscope at ×100 or ×200 magnifications. Non-overlapping regions from each section were analyzed by Aperio ImageScope software 10.1.3.2028 (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) using nuclear algorithm for quantitation of Ki-67 expression and TUNEL-positive cells, and membrane algorithm for quantitation of CD31 positive blood vessels. The results are presented as H-score for Ki-67 expression. The H-score is based on intensity (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) and % positivity (0–100%) and calculated using the formula: H score = (% of negative cells × 0) + (% 1+ cells × 1) + (% 2+ cells × 2) + (% 3+ cells × 3).

Measurement of tumor angiogenesis in live mice by fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT)

AngioSense 680-EX (Perkin-Elmer) was intravenously administered via the tail vein 24 hours prior to imaging. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane. Once the animal was fully sedated, a single mouse was placed in a plastic cassette and the anesthetic gas was administered to an inlet on the cassette. The cassette was placed into the heated imaging chamber of the VISEN FMT 2500 (Perkin-Elmer). Imaging times were approximately 3~5 minutes per mouse. Data analysis was done using TrueQuant software (Perkin-Elmer).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described by us previously [23].

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET/CT)

PET/CT was performed on day 52 for measurement of tumor glucose uptake. Fasted mice were imaged on an Inveon Small Animal Multimodal PET/CT scanner 1 hour following intravenous (lateral tail vein) administration of 7.4 ± 0.74 MBq (200 ± 20 µCi; 100 µL) [18F]-2-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG; IBA Pharmaceuticals, Dulles, VA) and analyzed as described previously [24].

Determination of lactate levels

A Sigma-Aldrich kit (St. Louis, MO; cat. #MAK064) was used to measure tumor and plasma lactate levels from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study according to the supplier’s instructions.

Determination of ex vivo tumor oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR)

Tumor tissues from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study were minced and mixed with collagenase-hyaluronidase (STEMCELL Technologies) in RPMI 1640 media, digested with collagenase (200–250 U/mL) at 37°C for 10~15 minutes, and then passed through a 40 µm nylon mesh cell strainer. After centrifugation, the cell pellets were washed with Hank’s balanced salt solution supplemented with 5% FBS and used for the determination of real-time oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and glycolysis rates by measuring OCR and ECAR, respectively, using a Seahorse XF24 Extracellular Flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) as described [25].

Proteomics

Tumor tissues from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study (n = 3/group) were used for proteomics by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by MALDI-TOF/TOF as detailed in our prior publications [20, 22].

Cytokine profiling

Millipore Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel (HCYTMAG-60K-PX38 for plasma) and Human Cytokine/Chemokine (MPXHCYTO60KPMX39 for tumor lysates) were used for cytokine profiling utilizing Luminex xMAP® Technology.

Statistical analyses

Tumor growth characteristics and biomarkers for multiple comparisons were examined using nonparametric test, ANOVA, repeated ANOVA or generalized linear mixed models. The generalized linear mixed models were performed to evaluate treatment effects, with a random-subject effect, a random coefficient or a repeated effect to account for within-subject correlation and between-subject variation. The 4-pair comparisons were conducted among least squares means. The corresponding 95% confidence limits were adjusted using Sidak method and the P values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak methods. Statistical significance of difference in plasma and tumor cytokine levels from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests. Where necessary, the P values were then adjusted using step-down Bonferroni method of Holm to control familywise error rate. The log-transformation was used for normalization where needed. Student t test was used for binary comparisons. A significance level was set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) or GraphPad Prism 6.05 (La Jolla, CA).

Results

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA treatment on in vivo growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts

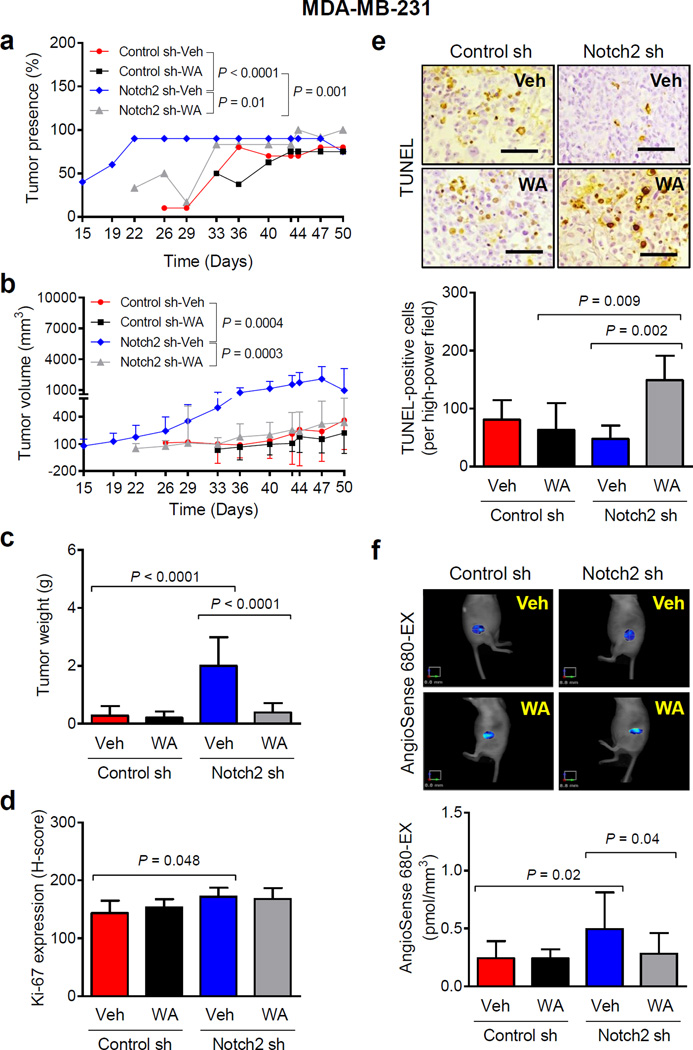

Tumor latency defined by the presence of measurable tumor (% tumor presence) was significantly different between Control sh-Veh and Notch2 sh-Veh groups (Fig. 1a). The percentage of tumor presence in Notch2 sh group was decreased significantly after WA treatment (Fig. 1a). Growth kinetics of the Control sh-Veh group was comparable to that of the Control sh-WA group. Tumor volume (Fig. 1b) and tumor weight (Fig. 1c) measurements also indicated that Notch2 knockdown accelerated MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth in vivo and these tumors were highly sensitive to inhibition by WA. The average body weights of the mice were similar for each group (results not shown).

Fig. 1.

Knockdown of Notch2 accelerates in vivo growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts. a Percentage of tumor presence over time in mice xenografted with MDA-MB-231 cells stably transfected with control shRNA (Control sh) or Notch2 shRNA (Notch2 sh) and treated with vehicle (Control sh-Veh or Notch2 sh-Veh) or 100 µg of withaferin A (WA)/mouse (Control sh-WA or Notch2 sh-WA) by intraperitoneal route. Results shown are percentage of tumor presence (n = 10 for Control sh-Veh; n = 8 for Control sh-WA; n = 10 for Notch2 sh-Veh except on day 50 where n = 4; n = 12 for Notch2 sh-WA). b Tumor volume over time for mice of different groups. Results shown are mean tumor volume with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars). c Wet tumor weight of MDA-MB-231 xenografts from different groups. Results shown are mean wet tumor weight with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 8 for Control sh-Veh; n = 6 for Control sh-WA; n = 9 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 12 for Notch2 sh-WA). d Immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 expression in MDA-MB-231 xenografts from different groups. Results shown are mean H-score with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 7 for Control sh-Veh; n = 6 for Control sh-WA; n = 6 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 9 for Notch2 sh-WA). e Representative images depicting TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells (×200 magnification, scale bar = 100 µm) and their quantitation in MDA-MB-231 xenografts of different groups. Results shown are mean TUNEL-positive cells with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 7 for Control sh-Veh; n = 6 for Control sh-WA; n = 6 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 9 for Notch2 sh-WA). f Representative images and quantitation of AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence in MDA-MB-231 xenograft bearing mice of different groups. Results shown are mean AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 6 for Control sh-Veh; n = 5 for Control sh-WA; n = 3 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 5 for Notch2 sh-WA). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by generalized linear mixed model and the least square means were used for comparison. The P values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak methods. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05.

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA treatment on proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in MDA-MB-231 xenografts

Ki-67 expression was modestly but significantly higher in the Notch2 sh-Veh xenograft sections compared with Control sh-Veh group (Fig. 1d). These results indicated that while accelerated in vivo tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown was accompanied by increased cellular proliferation, WA administration was unable to inhibit Ki-67 expression.

Figure 1e shows TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells in a representative MDA-MB-231 xenograft section of each group. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly higher in tumor sections of the Notch2 sh-WA group in comparison with Control sh-WA group and Notch2 sh-Veh group. These results indicated a slight decrease in apoptotic cell death by knockdown of Notch2 but restoration of apoptosis upon WA administration in tumors from this group of mice.

Average AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence was about 2-fold higher in the Notch2 sh-Veh xenografts compared with Control sh-Veh group (Fig. 1f). Consistent with reported anti-angiogenic activity of WA [26], mean AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence was significantly lower in the tumors of Notch2 sh-WA group compared with Notch2 sh-Veh xenografts. These results indicated that amplification of in vivo tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown and its reversal by WA administration was accompanied by altered tumor angiogenesis.

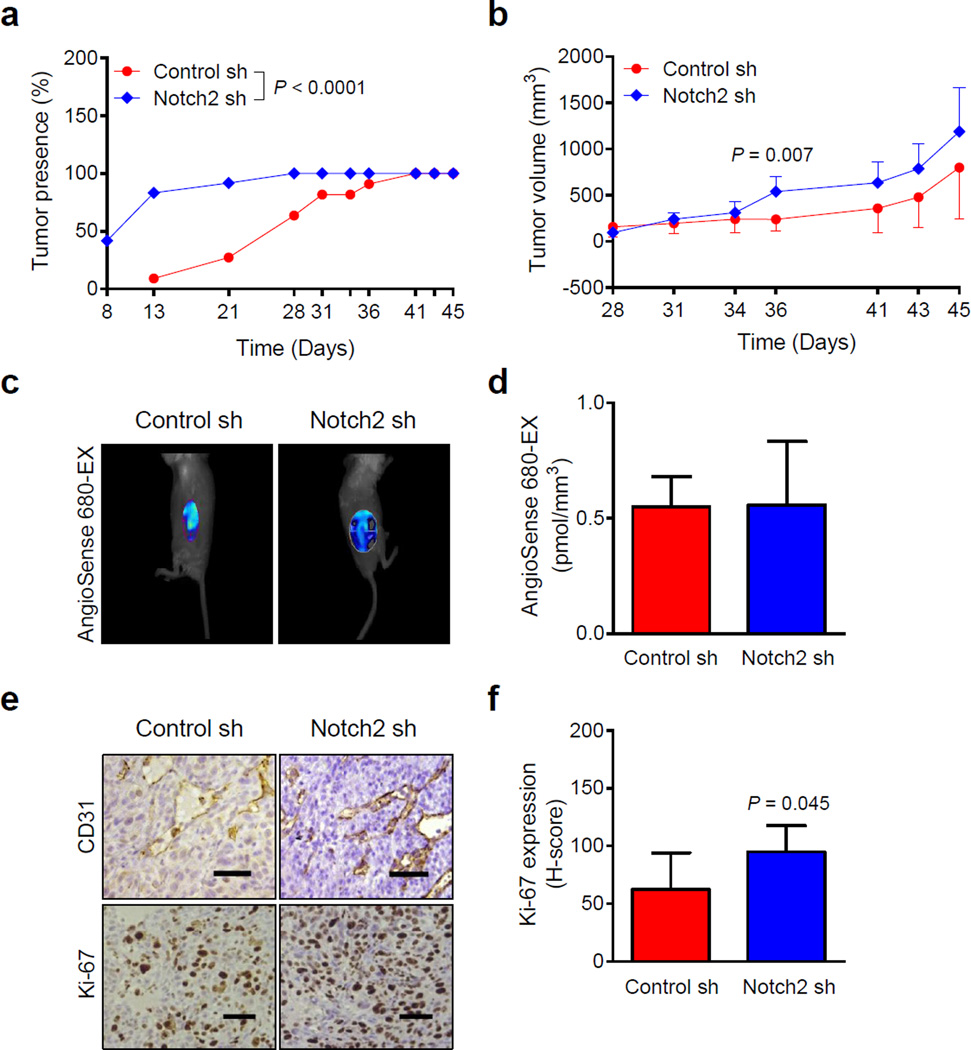

Effect of stable knockdown of Notch2 on in vivo growth of SUM159 xenografts

Tumor latency (% tumor presence over time) of SUM159 xenografts was significantly different between Notch2 sh and Control sh groups (Fig. 2a). The average tumor volume in Notch2 sh group was also higher compared with Control sh group but the difference was not significant except on day 36 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Notch2 knockdown augments in vivo growth of SUM159 xenografts in SCID mice. a Percentage of tumor presence as a function of time in mice bearing Control sh or Notch2 sh SUM159 cells. Results shown are percentage of tumor presence over time (n = 11 from 6 mice in Control sh group; n = 12 from 6 mice in Notch2 sh group). b Tumor volume over time for Control sh and Notch2 sh SUM159 xenografts. Results shown are mean tumor volume with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars). Representative images (c) and quantitation (d) of AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence for detection of angiogenesis in SUM159 xenografts. Results shown are mean AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 6 for Control sh; n = 4 for Notch2 sh). e Representative images for CD31-positive blood vessels and immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 expression (×200 magnification, scale bar = 100 µm) in tumor sections of SUM159 Control sh and Notch2 sh groups. f Quantitation of Ki-67 expression in SUM159 xenograft sections. Results shown are mean H-score with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 5 for Control sh; n = 6 for Notch2 sh). Statistical significance of difference, except for data in panels b, d, and f in which unpaired Student t test was used, was analyzed by generalized linear mixed model and the least square means were used for comparison. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05.

AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence, exemplified in Figure 2c, was not different between Notch2 sh-Veh and Control sh-Veh groups (Fig. 2d). Because the AngioSense 680-EX fluorescence data was inconsistent between MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1f) and SUM159 cells (Fig. 2d), we assessed tumor angiogenesis by immunohistochemistry for CD31 (Fig. 2e). Consistent with FMT data (Fig. 2d), the number of CD31-positive blood vessels was comparable in tumor sections from Control sh and Notch2 sh xenografts (data not shown). However, Ki-67 expression was higher in the Notch2 sh xenografts compared with Control sh xenografts (Fig. 2f).

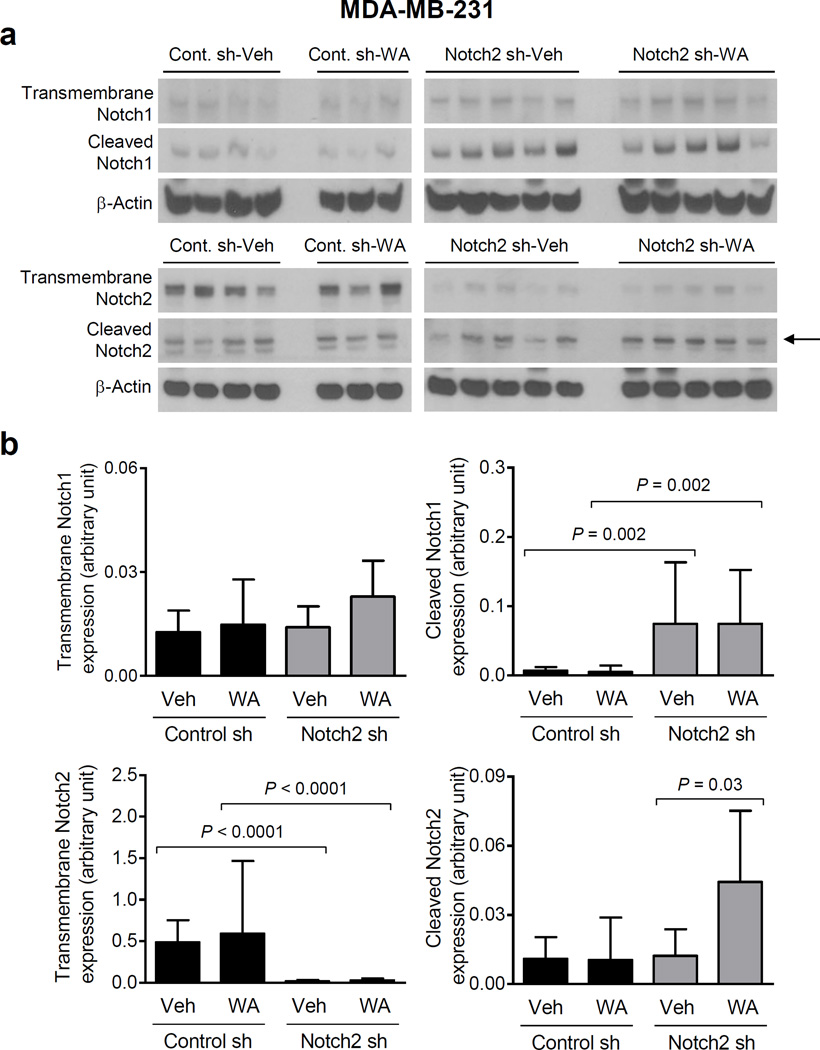

Notch1 and Notch2 levels in MDA-MB-231 tumors

Western blotting for transmembrane and cleaved (active form) Notch1 and Notch2 in representative tumors of each group (Fig. 3a) indicated that knockdown of full-length (transmembrane) Notch2 was maintained in vivo (Fig. 3b). Moreover, there was a compensatory increase in levels of cleaved Notch1 in the Notch2 sh-Veh xenografts compared with Control sh-Veh group (Fig. 3b). Consistent with in vitro cellular data [15], WA administration resulted in an increase in levels of cleaved Notch2 at least in in the Notch2 sh xenografts (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of Notch2 increases Notch1 activation in MDA-MB-231 xenografts. a Immunoblotting for transmembrane Notch1 and Notch2 and cleaved Notch1 and Notch2, and β-Actin proteins using tumor lysates from MDA-MB-231 xenografts of different groups. Arrow points to cleaved Notch2 band. b Quantitation of proteins shown in panel a Results shown are mean expression of proteins (arbitrary unit) with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 4 for Control sh-Veh; n = 3 for Control sh-WA; n = 5 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 5 for Notch2 sh-WA). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by generalized linear mixed model and the least square means were used for comparison. The P values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak methods. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05.

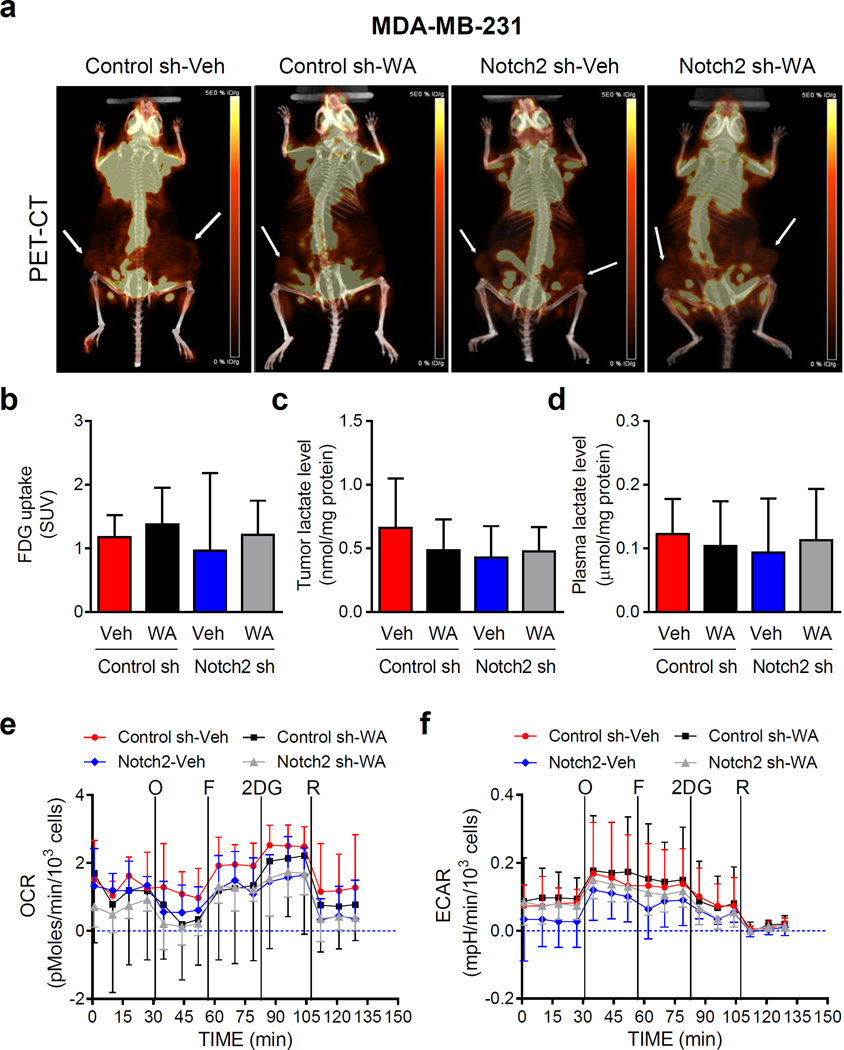

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA administration on in vivo glucose uptake and ex vivo MDA-MB-231 tumor metabolism

We determined glucose uptake in representative live mice of each group by measuring uptake of [18F]-2-fluorodeoxyglucose by PET-CT (Fig. 4a; tumor sites are identified by arrows). FDG uptake was not altered by Notch2 knockdown or WA treatment (Fig. 4b). Notch2 knockdown or WA treatment did not have a meaningful impact on overall glycolysis as reflected by tumor (Fig. 4c) or plasma (Fig. 4d) levels of lactate. Moreover, neither OCR (Fig. 4e) nor ECAR (Fig. 4f) was affected by Notch2 knockdown or WA treatment. These results indicated that altered metabolism was not responsible for augmented tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of Notch2 has no appreciable effect on in vivo glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 xenografts. a Representative images for positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts of different groups. Location of the tumor is indicated by an arrow. Quantitation of 18F-FDG uptake (b) and tumor lactate level (c) or plasma lactate level (d) from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study. Results for PET/CT are shown as mean 18F-FDG uptake levels (SUV) with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 6 for Control sh-Veh; n = 5 for Control sh-WA; n = 2 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 6 for Notch2 sh-WA). Results for tumor or plasma lactate level are shown as mean lactate levels with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 3 for all four groups). Real-time measurement of ex vivo oxygen consumption rate (OCR) (e) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (f) in MDA-MB-231 xenografts of different groups. O: 1 µM of oligomycin; F: 300 nM of FCCP; 2DG: 100 mM of 2-deoxyglucose; R: 1 µM of rotenone. Results shown are mean OCR and mean ECAR with their 95% confidence intervals (error bars, n = 4 for Control sh-Veh; n = 3 for Control sh-WA; n = 3 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 6 for Notch2 sh-WA). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by generalized linear mixed model and the least square means were used for comparison. The P values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak methods. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05.

Proteomic analysis

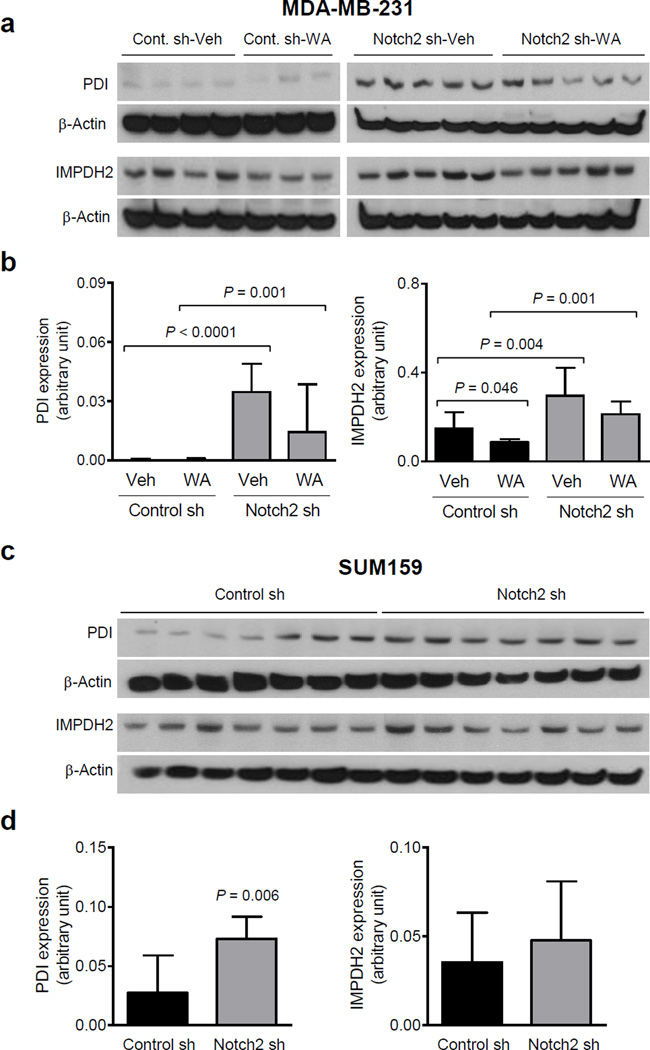

Even though tumors from all four groups were included in proteomics interrogation, we focused on proteins that were increased or decreased by Notch2 knockdown (Notch2 sh-Veh vs Control sh-Veh group) with a cut-off of at least 1.2-fold difference in level and P = 0.1 or less, and these changes were reversible by WA treatment. Proteins meeting these criteria are listed in Table 1. We selected IMPDH2 and PDI for confirmation of the proteomics data. The western blot results for PDI and IMPDH2 protein levels were generally consistent with proteomics data for both MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 5a, b) and SUM159 xenografts (Fig. 5c, d). For example, level of PDI protein was significantly higher in the MDA-MB-231 tumors of Notch2 sh-Veh group compared with Control sh-Veh group (Fig. 5a, b). Likewise, WA administration resulted in a decrease in protein level of IMPDH2 in Control sh group and Notch2 sh group (Fig. 5b). Thus, it is possible that overexpression of PDI and/or IMPDH2 may contribute to augmented tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown.

Table 1.

Identification of proteins altered by Notch2 knockdown and WA treatment in the MDA-MB-231 tumors.

| Protein | Master No. |

Notch2 sh-Veh vs. Control sh-Veh |

Notch2 sh-WA vs. Notch2 sh-Veh |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average ratio | P* | Average ratio | P* | ||

| Alcohol dehydrogenase [NADP(+)] | 1114 | −1.3 | 0.02 | 1.3 | 0.09 |

| Coactosin-like protein | 2282 | −1.4 | 0.03 | 1.4 | 0.07 |

| Cytoplasmic dynein 1 intermediate chain 2 | 443 | 1.6 | 0.04 | −1.3 | 0.09 |

| Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | 719 | 1.4 | 0.007 | −1.2 | 0.01 |

| Probable histidine--tRNA ligase, mitochondrial | 398 | 1.7 | 0.002 | −1.2 | 0.08 |

| Procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3 | 387 | −1.4 | 0.02 | 1.3 | 0.09 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase | 649 | 1.4 | 0.02 | −1.2 | 0.08 |

Statistical significance was determined by two-sided Student t test.

Fig. 5.

Notch2 knockdown increases protein levels of PDI and/or IMPDH2 in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 xenografts. a Immunoblotting for PDI, IMPDH2, and β-Actin proteins using lysates from MDA-MB-231 tumors of different groups. b Quantitation of proteins shown in panel a. Results shown are mean expression (arbitrary unit) with their 95% confidential intervals (error bars, n = 4 for Control sh-Veh; n = 3 for Control sh-WA; n = 5 for Notch2 sh-Veh; n = 5 for Notch2 sh-WA). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by generalized linear mixed model, and the least square means were used for comparison. The P values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak methods. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05. c Immunoblotting for PDI, IMPDH2, and β-Actin proteins using lysates from Control sh and Notch2 sh SUM159 tumors. d Quantitation of proteins shown in panel c. Results shown are mean expression (arbitrary unit) with their 95% confidential intervals (error bars, n = 7 for both Control sh and Notch2 sh tumors). Statistical significance of differences was analyzed by unpaired Student t test. All P values were two-sided and a significance level was set at 0.05.

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA treatment on plasma and tumor cytokines

Because Notch2 knockdown promoted in vivo tumor cell proliferation and/or angiogenesis, cytokine profiling was performed using plasma (Table 2) and tumor lysates (Table 3) from each group of the MDA-MB-231 xenograft. The primary analysis was restricted to changes in cytokine levels upon Notch2 knockdown (Notch2 sh-Veh vs Control sh-Veh) and their reversal by WA treatment (Notch2 sh-Veh vs Notch2 sh-WA). Because human-specific kits were used for cytokine profiling, plasma levels are indicative of cytokine secretion. Levels of several prosurvival/proangiogenic/proinflammatory cytokines were markedly elevated in the plasma from Notch2 sh-Veh group compared with Control sh-Veh group [G-CSF, GM-CSF, CXCL1 (GRO), IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15 (Table 2)]. Levels of these cytokines, except for IL-15, were significantly lower in the plasma of Notch2 sh-WA group compared with Notch2 sh-Veh group (Table 2). A similar trend for many of the plasma altered cytokines was also discernible in the tumor (e.g., G-CSF, CXCL1, IL-6, IL-8) (Table 3). These results indicated that tumor growth augmentation by Notch2 knockdown and its reversal by WA was accompanied by increased levels/secretion of different prosurvival/proangiogenic cytokines.

Table 2.

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA treatment on plasma cytokine levels from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study.

| Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Control sh-Veh (n = 5) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

Notch2 sh-Veh (n = 5) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

Notch2 sh-WA (n = 6) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

P |

| FGF-2 | 52.34 (−10.94 to 115.60) | 116.40 (28.97 to 203.90) | 174.30 (−6.56 to 355.20) | |

| G-CSF | 2.63 (−4.67 to 9.92) | 100.70 (22.14 to 179.30) | 15.88 (−10.22 to 41.97) | 0.004 (†), 0.009 (‡) |

| GM-CSF | 78.24 (−27.50 to 184.00) | 441.10 (46.83 to 835.40) | 102.40 (32.14 to 172.70) | 0.03 (†), 0.03 (‡) |

| GRO | 200.70 (−140.40 to 541.90) | 899.40 (208.40 to 1590.00) | 259.40 (−29.35 to 548.10) | 0.04 (†), 0.0495 (‡) |

| IFN-γ | 14.75 (3.27 to 26.23) | 17.03 (3.80 to 30.27) | 21.71 (12.07 to 31.34) | |

| IL-6 | 16.67 (−12.41 to 45.75) | 134.80 (17.83 to 251.80) | 24.90 (2.16 to 47.64) | 0.02 (†), 0.02 (‡) |

| IL-8 | 207.20 (−41.72 to 456.10) | 1465.00 (190.80 to 2740.00) | 328.00 (20.36 to 635.60) | 0.02 (†), 0.03 (‡) |

| IL-15 | 2.88 (−5.11 to 10.87) | 36.37 (−1.90 to 74.64) | 6.16 (−5.40 to 17.72) | 0.04 (†) |

| IL-17 | 29.25 (21.67 to 36.83) | 39.29 (15.73 to 62.84) | 47.50 (40.32 to 54.68) | |

| IP-10 | 7.85 (−3.36 to 19.05) | 21.53 (−0.01 to 43.08) | 1.92 (−1.36 to 5.19) | 0.03 (‡) |

| MDC (CCL22) | 53.76 (38.37 to 69.15) | 78.26 (43.43 to 113.10) | 61.07 (34.63 to 87.51) | |

| sCD40L | 5.71 (−10.15 to 21.57) | 16.71 (−11.61 to 45.03) | 38.60 (−60.63 to 137.80) | |

| TNF-α | 0.58 (−.68 to 1.84) | 1.00 (−0.48 to 2.48) | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) | |

| VEGF | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 11.36 (−15.97 to 38.68) | 6.57 (−10.32 to 23.47) | |

Statistically significant between Control sh-Veh and Notch2 sh-Veh.

Statistically significant between Notch2 sh-Veh and Notch2 sh-WA.

Table 3.

Effect of Notch2 knockdown and/or WA treatment on tumor cytokine levels from the MDA-MB-231 xenograft study.

| Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Control sh-Veh (n = 4) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

Notch2 sh-Veh (n = 7) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

Notch2 sh-WA (n = 6) Mean (95% CI), pg/mL |

P |

| EGF | 2.82 (−3.54 to 9.18) | 2.82 (−0.23 to 5.87) | 1.58 (0.15 to 3.02) | |

| FGF-2 | 1180.00 (739.80 to 1620.00) | 458.90 (330.10 to 587.80) | 812.70 (480.50 to 1145.00) | 0.001 (†) |

| Flt-3 ligand | 11.59 (6.37 to 16.80) | 9.88 (5.48 to 14.28) | 5.30 (1.96 to 8.63) | |

| Fractalkine | 51.82 (11.27 to 92.37) | 77.06 (7.39 to 146.70) | 51.14 (24.50 to 77.78) | |

| G-CSF | 10.88 (4.77 to 17.00) | 27.81 (12.34 to 43.28) | 14.38 (1.16 to 27.61) | |

| GM-CSF | 334.00 (215.10 to 453.00) | 282.90 (139.60 to 426.20) | 202.90 (102.4 to 303.5) | |

| GRO | 569.00 (147.80 to 990.3) | 795.10 (435.70 to 1155.00) | 490.00 (89.93 to 890.00) | |

| IFN-γ | 0.86 (0.03 to 1.69) | 1.32 (−0.54 to 3.18) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.86) | |

| IL-1α | 34.92 (21.57 to 48.27) | 49.48 (16.94 to 82.03) | 35.17 (19.85 to 50.49) | |

| IL-1β | 2.29 (.91 to 3.66) | 3.81 (.58 to 7.04) | 1.43 (1.07 to 1.78) | |

| IL-1ra | 4.93 (−4.52 to 14.38) | 15.28 (−10.77 to 41.33) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | |

| IL-3 | 0.42 (−0.23 to 1.06) | 0.86 (−0.02 to 1.74) | 0.53 (0.31 to 0.74) | |

| IL-6 | 169.10 (−5.32 to 343.50) | 344.40 (147.80 to 540.90) | 132.30 (−30.24 to 294.80) | |

| IL-7 | 4.91 (1.96 to 7.87) | 5.52 (2.81 to 8.23) | 4.11 (3.16 to 5.06) | |

| IL-8 | 1697.00 (480.10 to 2913.00) | 2843.00 (911.20 to 4775.00) | 1536.00 (529.90 to 2542.00) | |

| IL-13 | 1.55 (−0.27 to 3.37) | 2.40 (−0.24 to 5.03) | 1.77 (−0.33 to 3.86) | |

| IL-15 | 14.36 (13.57 to 15.15) | 20.40 (14.57 to 26.22) | 12.39 (9.16 to 15.62) | 0.02 (‡) |

| IL-17 | 0.14 (−0.03 to 0.32) | 0.48 (−0.38 to 1.34) | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) | |

| IP-10 | 74.09 (33.72 to 114.40) | 46.78 (28.84 to 64.73) | 24.99 (11.62 to 38.37) | |

| MCP-1 | 3.40 (1.86 to 4.95) | 3.22 (−0.08 to 6.52) | 1.68 (.86 to 2.50) | |

| MDC (CCL22) | 2.27 (−4.96 to 9.51) | 10.27 (−6.46 to 27.00) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | |

| TGFα | 26.54 (18.72 to 34.37) | 29.75 (17.82 to 41.68) | 24.51 (13.72 to 35.29) | |

| TNF-α | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.28) | 0.68 (0.34 to 1.01) | 0.52 (0.17 to 0.87) | |

| VEGF | 2554.00 (1622.00 to 3486.00) | 3906.00 (2523.00 to 5290.00) | 4876.00 (2110.00 to 7641.00) | |

Statistically significant between Control sh-Veh and Notch2 sh-Veh.

Statistically significant between Notch2 sh-Veh and Notch2 sh-WA.

Discussion

The present study reveals that the in vivo growth of MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 xenografts is markedly augmented by stable knockdown of Notch2 supporting a tumor growth suppressor role for this protein. Accelerated tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown is associated with a compensatory increase in activation of Notch1 and increased cellular proliferation and/or angiogenesis. It is reasonable to postulate that increased in vivo tumor cell proliferation by Notch2 knockdown is partly related to Notch1 activation because: (a) RNA interference of Notch1 decreases breast cancer cell growth in vitro [27]; (b) Notch1 inhibition causes regression of mammary tumors in vivo [28]; and (c) Notch1 overexpression is associated with transition from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive cancer [29]. The mechanism by which Notch2 knockdown causes compensatory activation of Notch1 in vivo requires further investigation.

Breast cancer is an intrinsically heterogeneous and complex disease broadly classified into five subgroups (luminal A, luminal B, Her-2/neu overexpressing, basal-like, and normal-like breast cancer) based on gene expression profiling [30, 31]. The triple-negative basal-like breast cancer subtype, which accounts for approximately 15–20% of all breast cancers is highly aggressive with a high incidence of visceral and central nervous system metastasis [30, 31]. Triple-negative subtype is further classified into different subgroups according to the gene expression pattern [31]. Cytotoxic chemotherapy (e.g., cisplatin) is still the only treatment option for triple-negative breast cancer. Both the cell lines used in the present study are basal B type but have some genetic differences. For example, PI3K is mutated in the SUM159 cell line (H1047L mutation) but not in the MDA-MB-231 cells [32]. The SUM159 cells also express mutant Hras [33]. Interestingly, tumor growth acceleration by Notch2 knockdown is relatively more pronounced in the MDA-MB-231 cells compared with SUM159. On the other hand, increased tumor angiogenesis by Notch2 knockdown is restricted to the MDA-MB-231 xenografts. Altered angiogenesis and PI3K mutational status may partly explain the cell line difference in growth characteristics.

The present study offers a novel option for therapeutic exploitation of Notch2-altered breast tumor growth. Increased tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown is highly sensitive to inhibition by WA. This steroidal lactone is a highly promising small molecule with demonstrated in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer efficacy against a variety of solid tumors including breast cancer in pre-clinical rodent models [reviewed in 34]. We found an increase in the levels of cleaved Notch2 after treatment with WA in MDA-MB-231 cells with Notch2 knockdown (present study). We have shown previously that WA treatment increases levels of γ-secretase components Presenilin 1 and/or Nicastrin in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells [15]. It is possible that these proteins are altered in the Notch2 sh tumor xenografts after WA treatment.

The proteomics analysis shows up- or down-regulation of several proteins by Notch2 knockdown and their reversal by WA treatment. While the role of most of these proteins in breast cancer is either unknown or poorly defined, two proteins (IMPDH2 and PDI) seem intriguing based on published literature [35–37]. Both these proteins are up-regulated in Notch2 sh group and their levels are decreased by WA treatment. Increased expression of IMPDH2 is associated with progression of kidney and bladder cancer [35]. Promotion of metastasis and advanced tumor progression in patients with prostate cancer is also associated with increased IMPDH2 expression [36]. Likewise, gene expression of PDI (PDIA3 and PDIA6) was shown to be a marker for aggressiveness in primary ductal breast cancer [37]. Thus the role of these proteins in breast cancer development and anti-cancer mechanisms of WA merits further investigation.

Augmented in vivo tumor growth by Notch2 knockdown is accompanied by an increase in secretion and/or upregulation of several cytokines (e.g., CXCL1, IL-6, and IL-8) that are implicated in breast cancer [38–43]. IL-6 expression is associated with poor prognosis for breast cancer [41]. Studies have also suggested that growth of TNBC critically depends upon coordinate autocrine expression of IL-6 and IL-8 [42]. It is highly likely that the observed proliferative/angiogenic effects of Notch2 knockdown are at least in part mediated by altered cytokine level/secretion.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that knockdown of Notch2 promotes in vivo growth of TNBC in association with a compensatory increase in Notch1 activation. Furthermore, therapeutic vulnerability of Notch2-altered tumor growth to WA is also demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health grant award RO1 CA142604-06 (to SVS). This research project used Animal Facility, In Vivo Imaging Facility, Tissue and Research Pathology Facility, and Proteomics Facility supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA047904).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethical standards: Use of mice and their care was in accordance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

References

- 1.Andersson ER, Sandberg R, Lendahl U. Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function. Development. 2011;138(17):3593–3612. doi: 10.1242/dev.063610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137(2):216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnett KL, Hass M, McArthur DG, Ilagan MX, Aster JC, Kopan R, Blacklow SC. Structural and mechanistic insights into cooperative assembly of dimeric Notch transcription complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(11):1312–1317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of Notch in tumorigenesis: Oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):756–767. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, Smith SD, Sklar J. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila Notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66(4):649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Previs RA, Coleman RL, Harris AL, Sood AK. Molecular pathways: Translational and therapeutic implications of the Notch signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(5):955–961. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazur PK, Grüner BM, Nakhai H, Sipos B, Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl LJ, Radtke F, Schmid RM, Siveke JT. Identification of epidermal Pdx1 expression discloses different roles of Notch1 and Notch2 in murine KrasG12D-induced skin carcinogenesis in vivo . PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu C, Diévart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P. Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(3):973–990. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison H, Farnie G, Howell SJ, Rock RE, Stylianou S, Brennan KR, Bundred NJ, Clarke RB. Regulation of breast cancer stem cell activity by signaling through the Notch4 receptor. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):709–718. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reedijk M, Odorcic S, Chang L, Zhang H, Miller N, McCready DR, Lockwood G, Egan SE. High-level coexpression of JAG1 and NOTCH1 is observed in human breast cancer and is associated with poor overall survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8530–8537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SH, Sehrawat A, Singh SV. Notch2 activation by benzyl isothiocyanate impedes its inhibitory effect on breast cancer cell migration. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(3):1067–1079. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sehrawat A, Sakao K, Singh SV. Notch2 activation is protective against anticancer effects of zerumbone in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146(3):543–555. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3059-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J, Sehrawat A, Singh SV. Withaferin A causes activation of Notch2 and Notch4 in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(1):45–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2239-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao CH, Chang CC, Wu MJ, Ko HW, Wang D, Hung MC, Yang JY, Chang CJ. MicroRNA-205 signaling regulates mammary stem cell fate and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):3093–3106. doi: 10.1172/JCI73351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neill CF, Urs S, Cinelli C, Lincoln A, Nadeau RJ, León R, Toher J, Mouta-Bellum C, Friesel RE, Liaw L. Notch2 signaling induces apoptosis and inhibits human MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(3):1023–1036. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parr C, Watkins G, Jiang WG. The possible correlation of Notch-1 and Notch-2 with clinical outcome and tumour clinicopathological parameters in human breast cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2004;14(5):779–786. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.14.5.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra LC, Singh BB, Dagenais S. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha): A review. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(4):334–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahm ER, Lee J, Kim SH, Sehrawat A, Arlotti JA, Shiva SS, Bhargava R, Singh SV. Metabolic alterations in mammary cancer prevention by withaferin A in a clinically relevant mouse model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1111–1122. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stan SD, Hahm ER, Warin R, Singh SV. Withaferin A causes FOXO3a- and Bim-dependent apoptosis and inhibits growth of human breast cancer cells in vivo . Cancer Res. 2008;68(18):7661–7669. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh SV, Kim SH, Sehrawat A, Arlotti JA, Hahm ER, Sakao K, Beumer JH, Jankowitz RC, Chandra-Kuntal K, Lee J, Powolny AA, Dhir R. Biomarkers of phenethyl isothiocyanate-mediated mammary cancer chemoprevention in a clinically relevant mouse model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(16):1228–1239. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powolny AA, Bommareddy A, Hahm ER, Normolle DP, Beumer JH, Nelson JB, Singh SV. Chemopreventative potential of the cruciferous vegetable constituent phenethyl isothiocyanate in a mouse model of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(7):571–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaino W, Anderson CJ. PET imaging of very late antigen-4 in melanoma: Comparison of 68Ga- and 64Cu-labeled NODAGA and CB-TE1A1P–LLP2A conjugates. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(11):1856–1863. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.144881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moura MB, Hahm ER, Van Houten B, Singh SV. The Use of Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer in Mechanistic Studies of Naturally Occurring Cancer Chemopreventive Agents. In: Bode Ann M, Dong Zigang, editors. Cancer Prevention: Dietary Factors and Pharmacology, Methods in Pharmacology and Toxicology. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014. pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahat G, Zhu QS, Huang KL, Wang S, Bolshakov S, Liu J, Torres K, Langley RR, Lazar AJ, Hung MC, Lev D. Vimentin is a novel anti-cancer therapeutic target; Insights from in vitro and in vivo mice xenograft studies. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Zang S, Chen F, Dai J, Guo D, Tse W, Qu X, Ma D, Ji C. RNAi-mediated knockdown of Notch-1 leads to cell growth inhibition and enhanced chemosensitivity in human breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(4):893–899. doi: 10.3892/or_00000712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons MJ, Serra R, Hermance N, Kelliher MA. NOTCH1 inhibition in vivo results in mammary tumor regression and reduced mammary tumorsphere-forming activity in vitro . Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(5):R126. doi: 10.1186/bcr3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan X, Zhang M, Wu H, Xu H, Han N, Chu Q, Yu S, Chen Y, Wu K. Expression of Notch1 correlates with breast cancer progression and prognosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurvitz S, Mead M. Triple-negative breast cancer: advancements in characterization and treatment approach. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28(1):59–69. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadav BS, Chanana P, Jhamb S. Biomarkers in triple negative breast cancer: A review. World J Clin Oncol. 2015;6(6):252–263. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i6.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavez KJ, Garimella SV, Lipkowitz S. Triple negative breast cancer cell lines: one tool in the search for better treatment of triple negative breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2010;32(1–2):35–48. doi: 10.3233/BD-2010-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnabas N, Cohen D. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of MCF10DCIS and SUM breast cancer cell lines. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:872743. doi: 10.1155/2013/872743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vyas AR, Singh SV. Molecular targets and mechanisms of cancer prevention and treatment by withaferin A, a naturally occurring steroidal lactone. AAPS J. 2014;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9531-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou J, Han Z, Zhou L, Cai C, Luo H, Huang Y, Liang Y, He H, Jiang F, Wang C, Zhong W. Elevated expression of IMPDH2 is associated with progression of kidney and bladder cancer. Med Oncol. 2015;32(1):373. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou L, Xia D, Zhu J, Chen Y, Chen G, Mo R, Zeng Y, Dai Q, He H, Liang Y, Jiang F, Zhong W. Enhanced expression of IMPDH2 promotes metastasis and advanced tumor progression in patients with prostate cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(10):906–913. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramos FS, Serino LT, Carvalho CM, Lima RS, Urban CA, Cavalli IJ, Ribeiro EM. PDIA3 and PDIA6 gene expression as an aggressiveness marker in primary ductal breast cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(2):6960–6967. doi: 10.4238/2015.June.26.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dethlefsen C, Højfeldt G, Hojman P. The role of intratumoral and systemic IL-6 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):657–664. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todorović-Raković N, Milovanović J. Interleukin-8 in breast cancer progression. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013;33(10):563–570. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Divella R, Daniele A, Savino E, Palma F, Bellizzi A, Giotta F, Simone G, Lioce M, Quaranta M, Paradiso A, Mazzocca A. Circulating levels of transforming growth factor-βeta (TGF-β) and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-1 (CXCL1) as predictors of distant seeding of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(4):1491–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin S, Gan Z, Han K, Yao Y, Min D. Interleukin-6 as a prognostic marker for breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Tumori. 2015;101(5):535–541. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartman ZC, Poage GM, den Hollander P, Tsimelzon A, Hill J, Panupinthu N, Zhang Y, Mazumdar A, Hilsenbeck SG, Mills GB, Brown PH. Growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells relies upon coordinate autocrine expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8. Cancer Res. 2013;73(11):3470–3480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4524-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freund A, Chauveau C, Brouillet JP, Lucas A, Lacroix M, Licznar A, Vignon F, Lazennec G. IL-8 expression and its possible relationship with estrogen-receptor-negative status of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(2):256–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]