Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking generates reactive oxidant species and contributes to systemic oxidative stress, which plays a role in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Nutrients with antioxidant properties, including vitamin E and selenium, are proposed to reduce systemic oxidative burden and thus to mitigate the negative health effects of reactive oxidant species.

Objective

Our objective was to determine whether long-term supplementation with vitamin E and/or selenium reduces oxidative stress in smokers, as measured by urine 8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha (8-iso-PGF2α).

Design

We measured urine 8-iso-PGF2α with competitive enzyme linked immunoassay (ELISA) in 312 male current smokers after 36 months of intervention in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of vitamin E (400 IU/d all rac-α-tocopheryl acetate) and/or selenium (200 μg/d L-selenomethionine). We used linear regression to estimate the effect of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α, with adjustments for age and race.

Results

Compared to placebo, vitamin E alone lowered urine 8-iso-PGF2α by 21% (p=0.02); there was no effect of combined vitamin E and selenium (intervention arm lower by 9%; p=0.37) or selenium alone (intervention arm higher by 8%; p=0.52).

Conclusions

Long-term vitamin E supplementation decreases urine 8-iso-PGF2α among male cigarette smokers, but we observed little to no evidence for an effect of selenium supplementation, alone or combined with vitamin E.

Keywords: Isoprostanes, Antioxidant nutrients, Alpha-tocopherol, Vitamin E, Selenium, Cigarette smoking, Lung function, Oxidative stress, Lipid peroxidation, Randomized controlled trial, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

1. Introduction

Observational studies report that diets high in fruits and vegetables are associated with lower risk of chronic disease [1] and lower plasma isoprostanes [2], a class of compounds which are biomarkers of systemic oxidative stress. Given oxidative stress is widely believed to play a role in the pathophysiology of multiple chronic diseases, the identification of interventions to reduce oxidative stress remains of interest as a preventive approach [3]. The effect of long-term antioxidant intervention on F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs), the gold standard biomarker of in vivo lipid peroxidation [4], has not been adequately assessed.

8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha (8-iso-PGF2α, also referred to as 15-F2t-isoprostane), a chemically stable isomer in the isoprostane class of compounds, is generated in vivo by the non-enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid. Urine and plasma F2-IsoPs are a reliable biomarker of oxidative stress [3]. Elevations in F2-IsoPs are associated with smoking [2,5–7] and a wide range of diseases [3,8] including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [6,9–12]. It is estimated that the heritability of F2-IsoPs is 10% [13], thus inter-individual variability in F2-IsoPs is primarily due to environmental determinants.

Vitamin E and selenium, nutrients consumed in foods and/or as supplements, have antioxidant properties and are hypothesized to play a role in reducing oxidative stress. Ten of 18 past vitamin E intervention trials reported a decrease in plasma or urine F2-IsoPs with intervention [14]. Interpretation of past studies is hampered by short duration of intervention, heterogeneity in the intervention formulation and dose, and the type of participant studied; further study is needed. Definitive information on the effect of selenium supplementation on F2-IsoPs is also lacking. A prior observational study reported that higher selenium status at baseline was associated with lower F2-IsoPs about 25 years later [5], but selenium intervention studies report mixed findings [15,16].

Within a subset of the Respiratory Ancillary Study (RAS) [17], an ancillary study to a large randomized placebo-controlled trial of vitamin E and/or selenium supplementation (the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial, SELECT [18]), we tested the hypothesis that supplementation with these nutrients over 36 months lowers oxidative stress as measured by urine 8-iso-PGF2α. In the RAS, selenium and/or vitamin E supplementation had no effect on rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1); however, selenium supplementation in current smokers attenuated the rate of decline in forced expiratory flow (FEF25–75), a marker of airflow [17].

Our primary objective in this paper was to investigate the effects of supplementation on urine 8-iso-PGF2α among current smokers; main trial results on pulmonary endpoints are reported elsewhere [17]. Our secondary objectives were: (1) to determine the effect of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α in the subset of men with prevalent COPD; (2) to describe differences in urine 8-iso-PGF2α by smoking and COPD status in the placebo group; and (3) to investigate whether intervention effects on rate of decline in lung function, the main endpoint in the RAS, were mediated by lowering of urine 8-iso-PGF2α.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

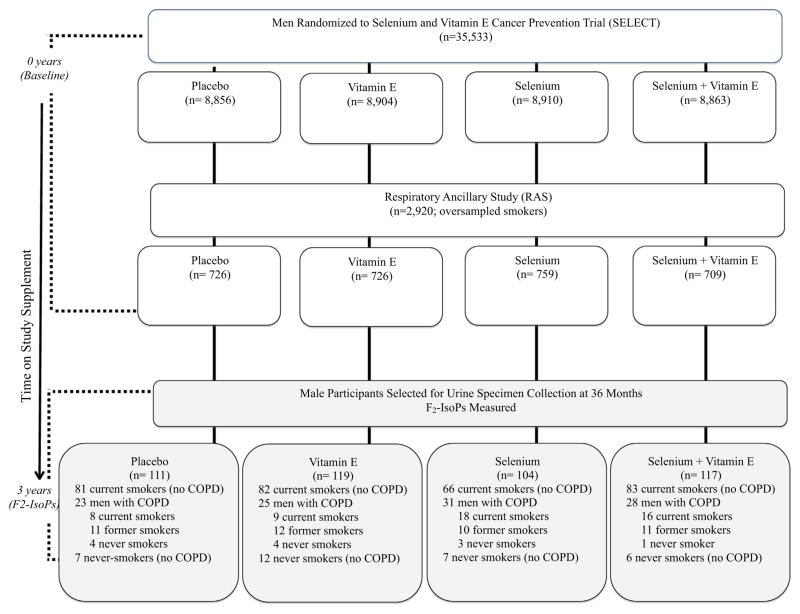

Details regarding the study design are shown in Fig. 1. Participants were men enrolled in the RAS [17] (ancillary to SELECT [18]; NCT00063453 and NCT00006392, respectively, on clinicaltrials.gov). RAS studied 2920 SELECT participants for effects of vitamin E and/or selenium intervention on rate of change in lung function. Participants were eligible for SELECT if they were males aged ≥55 years (≥50 in African Americans) with no prior prostate cancer diagnosis, serum prostate specific antigen ≤4 ng/mL, a non-suspicious digital rectal examination, no current use of anticoagulant therapy, no history of hemorrhagic stroke, and normal blood pressure. RAS registered SELECT participants at 16 study sites across North America. Since the objectives of RAS focused on lung outcomes and cigarette smokers are at greater risk of adverse lung outcomes, there was preferential recruitment of current smokers to RAS. Further details are published elsewhere [17,18]. Institutional Review Boards for Human Participants at Cornell University and at the 16 study sites approved RAS, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Sample selection by study intervention arm. F2-IsoPs (8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha) were measured in urine specimens collected from a subset of participants in the Respiratory Ancillary Study (RAS) to the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). RAS participants who, at year three on study, were currently smoking or had self-reported a physician’s diagnosis of COPD were invited to submit a urine specimen at the year three study visit; a small random sample of participants with a lifetime history of never smoking also submitted specimens. Shaded boxes indicate participants who were included in F2-IsoP analyses.

2.2. Intervention: vitamin E and/or selenium supplements

RAS retained the blinded randomization assignment from SELECT. Participants were randomized to one of four arms: oral 400 IU/day α-tocopherol (all rac-α-tocopheryl acetate, hereafter referred to as vitamin E) plus matched selenium placebo; 200 μg/day selenomethionine (L-selenomethionine, hereafter referred to as selenium) and matched vitamin E placebo; vitamin E+selenium; or, placebo+placebo [18]. Supplement doses and formulations were chosen to maximize the intervention effect on prostate cancer endpoints and to allow for comparisons to past trials. Adherence to study supplements was assessed by pill count at each study visit, and adherence was defined as taking at least 80% of study supplements.

2.3. Outcome: urine F2-isoprostanes

By protocol, urine was collected at 36 months on study; actual timing of urine collection ranged from 24 to 76 months on study during the calendar period 9/2004–10/2008. F2-IsoP, more specifically 8-iso-PGF2α, was assayed in urine specimens using a competitive enzyme linked immunoassay (ELISA) kit from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). The between-run precision for a set of control samples assayed over six months was estimated by the coefficient of variation, which was 18.7%. 8-iso-PGF2α values were adjusted for creatinine (expressed as 8-iso-PGF2α pg/mg creatinine); creatinine was measured using an ATAC 8000 (Vital Diagnostics, Lincoln, RI) and, later, a Siemens (Deerfield, IL) Dimension Xpand Plus, and creatinine values from both devices were in excellent agreement (average difference of 2.3% in paired samples). The published coefficients of variation for the Xpand are 2.5% and 4.2% for within- and between-run precision, respectively. Additional assay details are provided in the online supplement.

2.4. Covariates

Age at urine collection was calculated based on the participant’s self-reported date of birth and the date of urine collection. Data collected at study baseline included race, weight, height, and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Smoking status (current, former, never) and smoking dose (number of cigarettes per day) were obtained from data self-reported at baseline and at follow-up study visits up to the date of urine collection. The number of men providing urine specimens was approximately equal across the four arms of the trial; thus, in the full subset of men providing urine specimens we expect that known and unknown confounders are balanced across the four arms.

2.5. Statistical methods

Natural log (ln) transformation was used to normalize the distribution of 8-iso-PGF2α. In the primary analysis to estimate the effect of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α, we used generalized linear regression models. The dependent variable in the model was the year three urine 8-iso-PGF2α; treatment arm (vitamin E, selenium, or vitamin E+selenium; placebo as reference group) was the main predictor, with adjustments for age (continuous) and race (African American, Caucasian/other). Robust regression models were used to explore the influence of extreme, but valid, 8-iso-PGF2α values. To preserve the benefits of randomization and to reduce confounding bias, we primarily focused on intent-to-treat analyses; however, since the intent-to-treat approach leads to conservative estimates of the effects of intervention [19], we also conducted a sensitivity analysis limited to adherent participants; adherence was determined using pill-count data from the visit closest to the urine collection date. In all models, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were completed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

2.6. Objectives

Our primary objective was to test the effect of 36 months of supplementation with vitamin E and/or selenium on oxidative stress, as measured by urine 8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha (8-iso-PGF2α) in current smokers without COPD (N=312 participants with data).

We conducted three additional analyses to address our secondary objectives, as follows: (1) to investigate the effects of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α in RAS participants with a self-reported physician diagnosis of COPD (“emphysema, chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”), including COPD cases prevalent at study baseline as well as those reported for the first time on a follow-up questionnaire before the date of urine collection (total N=107 RAS participants); (2) to compare urine 8-iso-PGF2α levels by disease and smoking status in participants in the placebo arm (N=81 Current smokers without COPD, N=8 current smokers with COPD, N=7 never smokers without COPD); (3) to investigate whether 8-iso-PGF2α was a mediator of the effect of supplements on lung function (N=312 current smokers without COPD).

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics: current smokers without COPD

At study baseline all current smokers without COPD were similar on measured characteristics across intervention groups (Table 1), as expected given the randomized study design. About 50% of current smokers were African American; and, the proportion of African American men was slightly higher in the selenium arm (64%). Among all current smokers, the mean age at urine collection was 63 years and the majority (79%) smoked ≥5 cigarettes/day.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and effects of intervention urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) by treatment arm for male current cigarette smokers without COPD (n=312).a

| Placebo | Vitamin E | Selenium | Vitamin E+selenium | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. participants | 81 | 82 | 66 | 83 | 312 |

| African American, n (%) | 43 (53) | 38 (46) | 42 (64) | 40 (48) | 163 (52) |

| Age at urine collection (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 62.9 (5.8) | 62.9 (6.3) | 63.6 (7.0) | 63.0 (5.7) | 63.1 (6.1) |

| 50–59 | 29 (36) | 30 (37) | 22 (33) | 30 (36) | 111 (36) |

| 60–69 | 43 (53) | 41 (50) | 36 (55) | 44 (53) | 164 (52) |

| ≥70 | 9 (11) | 11 (13) | 8 (12) | 9 (11) | 37 (12) |

| Time on supplement (months), mean (SD)b | 38.1 (6.7) | 37.9 (5.4) | 37.4 (5.1) | 38.8 (7.6) | 38.1 (6.3) |

| Smoking dose ≥5 cigarettes per day, n (%) | 66 (81) | 64 (78) | 51 (77) | 64 (77) | 245 (79) |

| Pack-years of cigarette smokingc | 31 (21) | 31 (21) | 32 (23) | 36 (31) | 33 (24) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)d | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.8 (4.4) | 27.5 (4.6) | 27.2 (3.7) | 27.2 (4.4) | 27.2 (4.3) |

| Normal weight | 34 (42) | 21 (26) | 19 (29) | 23 (28) | 97 (31) |

| Overweight | 30 (37) | 41 (50) | 31 (47) | 44 (53) | 146 (47) |

| Obese | 17 (21) | 20 (24) | 16 (24) | 16 (19) | 69 (22) |

| Effects of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) at 36 months | |||||

| Median (interquartile range)e | 347 (82–1768) | 281 (55–1366) | 400 (27–1723) | 343 (58–2218) | 338 (82–2218) |

| Geometric meanf | 367 | 291 | 393 | 335 | – |

| % Difference from placebof | Ref. | −21% | 8% | −9% | – |

| p-Value for difference from placebof | Ref. | 0.0231 | 0.5217 | 0.3738 | – |

Unless noted otherwise, values in table are mean (standard deviation) or number (%). Smoking dose and pack-years of cigarette smoking were based on data collected through date of urine specimen collection, and age was calculated based on date of urine collection; data on other variables were derived from baseline information. COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Time on study at urine collection ranged from 24 to 76 months. By protocol, urine collected at 36 months on study; calendar dates of urine collection ranged from 9/2004 to 10/2008.

3 participants missing data on pack-years (1 participant each from the placebo, vitamin E, and selenium arms).

BMI categories: normal weight <25, overweight 25–30, obese >30.

Median (range) is based on raw (unadjusted) data, not on model results.

Least squares regression models were adjusted for age (continuous) and race (African American, Caucasian/other); Urine 8-iso-PGF-2α values were ln-transformed; model results were used to compute the geometric mean in each group, predicted %difference in concentration at 36 months for each treatment arm (versus placebo/placebo), and yielded p-value for Wald’s test of regression coefficient for treatment effect.

3.2. Primary objective

In cigarette smokers without COPD, supplementation with vitamin E alone decreased urine 8-iso-PGF2α by 21% (p=0.02; Table 1). There was no evidence for an effect of selenium alone (p=0.52) or for an effect of the combination of vitamin E+selenium (p=0.37). The magnitude of the vitamin E effect was greater in models limited to adherent participants: vitamin E supplementation produced a 27% reduction in F2-IsoPs (p =0.01). The effects of selenium and vitamin E+selenium, however, were unchanged in the sensitivity analysis (data not shown).

Smoking dose (usual number of cigarettes smoked per day) was a significant independent predictor of urine 8-iso-PGF2α (p=0.04; data not shown). In models estimating the effect of supplement group on 8-iso-PGF2α, further adjustment for smoking dose had little or no effect on the effect of supplement, and there was no evidence of a smoking dose × supplement group interaction effect on urine 8-iso-PGF2α (data not shown).

3.3. Secondary objectives

First, we investigated the effect of supplements on urine 8-iso-PGF2α in participants with COPD (n=107); this group of participants was considered separately due to possible effects of the disease process and/or disease treatment on the 8-iso-PGF2α. About half of the participants with COPD were non-smokers at the time of urine collection, but nearly all men with COPD (89%) reported a history of smoking (Table 2). Compared to men in the placebo arm, men randomized to vitamin E alone or in combination with selenium had lower mean 8-iso-PGF2α at year three [lower by 14% (p=0.43) and 20% (p=0.24), respectively; Table 2]. There was no effect of selenium alone (compared to placebo, 8-iso-PGF2α lower by 6%, p=0.74). Among men with COPD there was no association between urine 8-iso-PGF2α and medication use including inhaled corticosteroids, ACE inhibitors, and statins (data not shown).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics and effects of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) by treatment arm in men with COPD (n=107).a

| Men with COPD

|

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Vitamin E | Selenium | Vitamin E+selenium | ||

| No. participants | 23 | 25 | 31 | 28 | 107 |

| African American, n (%) | 9 (39) | 9 (36) | 18 (58) | 12 (43) | 48 (45) |

| Age at urine collection (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 68.9 (7.7) | 66.0 (7.8) | 64.6 (8.0) | 66.4 (7.4) | 66.3 (7.8) |

| 50–59 | 2 (9) | 9 (36) | 13 (42) | 6 (21) | 30 (28) |

| 60–69 | 10 (11) | 7 (28) | 10 (32) | 11 (39) | 38 (36) |

| ≥70 | 11 (48) | 9 (36) | 8 (26) | 11 (39) | 39 (37) |

| Time on supplement (months), mean (SD)b | 39.7 (7.7) | 37.2 (2.8) | 38.1 (7.7) | 36.5 (0.5) | 37.8 (5.7) |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||||

| Never | 4 (17) | 4 (16) | 3 (10) | 1 (4) | 12 (11) |

| Former | 11 (48) | 12 (48) | 10 (32) | 11 (40) | 44 (41) |

| Current | 8 (35) | 9 (36) | 18 (58) | 16 (57) | 51 (48) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day, n (%) | |||||

| <5 Cigarettes/day | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) |

| ≥5 Cigarettes per day | 7 (30) | 8 (32) | 16 (51) | 16 (57) | 47 (44) |

| Pack-years of cigarette smokingc | 10 (18) | 16 (26) | 20 (27) | 19 (22) | 16.6 (24) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)d | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.4 (4.8) | 28.9 (6.5) | 26.4 (4.7) | 27.6 (5.2) | 27.3 (5.3) |

| Normal weight | 12 (52) | 8 (32) | 15 (48) | 8 (4) | 43 (40) |

| Overweight | 5 (22) | 8 (32) | 7 (23) | 14 (50) | 34 (32) |

| Obese | 6 (26) | 9 (36) | 9 (29) | 6 (21) | 30 (28) |

| Effects of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) at 36 months | |||||

| Median (range)e | 330 (82–1678) | 247 (103–1875) | 358 (108–1237) | 294 (52–1434) | 295 (52–1875) |

| Geometric meanf | 302 | 258 | 283 | 240 | |

| % Difference from placebof | Ref. | −14% | −6% | −20% | |

| p-Value for difference vs placebof | Ref. | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.24 | |

Urine 8-iso-PGF-2α values were ln-transformed; model results were used to compute the geometric mean in each group, predicted %difference in concentration at 36 months for each treatment arm (versus placebo/placebo), and yielded p-value for Wald’s test of regression coefficient for treatment effect

Unless noted otherwise, values in table are mean (standard deviation) or number (%). Smoking dose and pack-years of cigarette smoking were based on data collected through date of urine specimen collection, and age was calculated based on date of urine collection; data on other variables were derived from baseline information. COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Time on study at urine collection ranged from 35 to 79 months. By protocol, urine collected at 36 months on study; calendar dates of urine collection ranged from 9/2004 to 10/2008.

1 participant missing pack-years (selenium arm); pack-years ranged from 0 (never smokers) to 119.

BMI categories: normal weight <25, overweight 25–30, obese >30.

Median (range) is based on raw (unadjusted) data, not on model results.

Least squares regression models were adjusted for age (continuous), race (African American, Caucasian/other), and smoking status (current, former, never).

Second, we compared the crude unadjusted mean concentrations of urine 8-iso-PGF2α among men in the placebo arm in the following groups: asymptomatic (no reported COPD) current smokers (N=81), men with COPD (N=8), and healthy (no reported COPD) never smokers (N=7) (Table 3). Among men in the placebo group, current smokers without COPD had a geometric mean 8-iso-PGF2α of 367 pg/mg creatinine, which was approximately double the value in never smokers (N=7; geometric mean 8-iso-PGF2α 194 pg/mg creatinine, p=0.0159 for test of difference in means). The mean in current smokers with COPD on placebo (N=8) was 653 pg/mg creatinine, which was almost double the concentration in current smokers without COPD on placebo (N=81; 367 pg/mg creatinine, p=0.0230 for test of difference in means).

Table 3.

Participant characteristics and urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) at 36 months on study among men in the placebo arm.a

| Participant characteristic | Men in the placebo/placebo intervention group

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current smokers without COPD | Current smokers with COPD | Never smokers without COPD | |

| No. participants | 81 | 8 | 7 |

| African American, n (%) | 43 (53) | 4 (50) | 3 (43) |

| Age at urine collection (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 63 (6) | 65 (7) | 66 (9) |

| 50–59 | 29 (36) | 1 (13) | 2 (29) |

| 60–69 | 43 (53) | 4 (50) | 3 (43) |

| ≥70 | 9 (11) | 3 (38) | 3 (29) |

| Time on supplement (months) b, mean (SD) | 38 (7) | 37 (3) | 35 (5) |

| Smoking dose ≥5 cigarettes per day, n (%) | 66 (81) | 7 (88) | 0 (0) |

| Pack-years of cigarette smoking, mean (SD)c | 31 (21) | 28 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)d | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27 (4) | 25 (5) | 32 (2) |

| Normal weight | 34 (42) | 5 (63) | 0 (0) |

| Overweight | 30 (37) | 2 (25) | 2 (29) |

| Obese | 17 (21) | 1 (13) | 5 (71) |

| Urine 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mg creatinine) at 36 monthse | |||

| Median (range) | 347 (82–1768) | 672 (160–1678) | 181 (104–469) |

| Geometric mean | 367 | 653 | 194 |

Unless noted otherwise, values in table are mean (standard deviation) or number (%). Smoking dose and pack-years of cigarette smoking were based on data collected through date of urine specimen collection, and age was calculated based on date of urine collection; data on other variables were derived from baseline questionnaires and study visit. COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Time on study at urine collection. By protocol, urine collected at 36 months on study; dates of urine collection ranged from 2004 to 2007; in the placebo arm, months on study at urine collection ranged from 32 to 73 for current smokers without COPD, 36–43 for current smokers with COPD, and 24–38 for never smokers without COPD. By protocol, urine collected at 36 months on study; dates of urine collection for the RAS ranged from 9/2004 to 10/2008.

1 current smoker without COPD was missing data on pack-years.

BMI categories: normal weight <25, overweight 25–30, obese >30.

Median based on original scale data; geometric mean is back-transformed mean of ln-transformed data.

Third, we explored the mediating effect of urine 8-iso-PGF2α on lung function in current smokers without COPD. In the full RAS, selenium supplements attenuated rate of decline in an indicator of airways flow (FEF25–75) in current smokers only [17]. However, we found no evidence for an effect of selenium on urine 8-iso-PGF2α in the 312 current smokers studied herein (see above), and thus the proposed question of mediation of effects on lung function was moot. Indeed, among the 312 current smokers without COPD who submitted urine specimens, we found no evidence that the effect of selenium on rate of decline in FEF25–75 was mediated by urine 8-iso-PGF2α (data not shown). Urine 8-iso-PGF2α was inversely associated with cross-sectional FEV1 (β = −95 mL lower FEV1 per unit increase in ln 8-iso-PGF2α; p=0.07), but there was no evidence of an association with rate of decline in FEV1 (p =0.79). Associations between 8-iso-PGF2α and lung function were similar in sensitivity analyses limited to adherent men (data not shown). Finally, in analyses limited to men with COPD, there was no evidence for effects of supplements on lung function endpoints, whether models assessed absolute or relative change [20] in pulmonary function parameters of volume and flow (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, 36 months of intervention with vitamin E (400 IU/day all rac-α-tocopheryl acetate) lowered systemic oxidative stress, measured by urine 8-iso-PGF2α, by 21% in male smokers without COPD. The effect of vitamin E+selenium (200 μg/day selenomethionine) was lower in magnitude and not statistically significant (intervention arm lower by 9%; P=0.37), and there was no effect of selenium alone on urine 8-iso-PGF2α (intervention arm higher by 8%, p=0.52). Effects of vitamin E on urine 8-iso-PGF2α in men with COPD (including current, former, and never smokers) were similar in magnitude and direction to effects in current smokers without COPD, although the sample size was small and findings did not reach statistical significance thresholds.

Results of past vitamin E interventions on F2-IsoPs are mixed, and comparisons are hindered by differences in study design, including the type of intervention. For example, some studies combine vitamin E with other supplements including vitamin C [21], and past vitamin E dosages varied widely with reported interventions ranging from 100 [21] to 3200 IU/d [22]. Furthermore, although differences in supplement formulation may lead to unequal bioavailability (the natural form of vitamin E has twice the bioavailability of synthetic vitamin E [23]), not all studies specify the type of vitamin E administered. Lastly, previous intervention studies were small, including between 12 [21] and 80 [22] participants, and short in duration (typically less than one month [21,23–25]). The magnitude of the effect of long-term vitamin E intervention to lower urine 8-iso-PGF2α reported here is consistent with results from shorter studies in smokers, which used similar doses and formulations of vitamin E.

In the vitamin E+selenium arm, there was less of an effect on urine 8-iso-PGF2α, in contrast to the vitamin E alone arm, and there are several possible explanations for this finding. First, this group had a higher mean smoking dose compared to the other treatment arms, and a higher oxidative stress burden might drive this finding. However, given no change in the finding when models were additionally adjusted for smoking, this explanation is not complete. Second, chance may play a role in these findings. Finally, it is possible that selenium acted as a pro-oxidant, particularly in this selenium-replete population [26].

There are few past studies of selenium intervention and no studies that are comparable to the randomized trial reported herein. The few published studies that investigated selenium intervention in relation to F2-IsoPs were short-term (3 days [15]–24 weeks [16]), small (n=40 [15]–81 [16]), and/or selectively studied special subgroups (intensive care patients [15] Australian men with low baseline selenium [16]). Selenium dose and formulation varied between studies; for example, one study compared 3 doses (474, 316, or 158 μg/day) of intravenous selenium selenite [15] while another fed participants selenium-fortified wheat biscuits [16]. We found no effect of selenium on urine F2-IsoPs after 36 months of supplementation. Unlike vitamin E, which is directly involved in terminating lipid oxidation, selenium is used by glutathione reductase and thioredoxin to reduce protein thiol pools, thus selenium effects may not be reflected in the lipid oxidation biomarker. Another possible explanation for the null finding is that the beneficial effects of supplementation may be limited to participants low in selenium, and the participants in the randomized trial were likely to be selenium-replete [26]. The mean baseline plasma selenium in the full RAS sample was 170.7 ng/mL (SD 27.7), which is well above the average level in US males (137 ng/mL) [27]. Finally, we cannot discount the possibility that selenium may act as a pro-oxidant at higher doses, although selenomethionine, which was the selenium form used in RAS, is unlikely to have pro-oxidant activity [28,29].

Furthermore, the finding of no effect of selenium on urine 8-iso-PGF2α may be explained, in part, by the higher proportion of African Americans in the selenium arm. Previous studies document a higher level of oxidative stress in African Americans [2,30], and we found higher average urine 8-iso-PGF2α in African Americans compared to other men (Caucasian/other) and the difference in 8-iso-PGF2α was not explained by differences in smoking dose (usual number of cigarettes smoked per day).

Consistent with past studies [2,5–7,9–12,31,32], 8-iso-PGF2α was higher in current smokers (compared to never smokers) and in men with COPD (compared to non-diseased men), in support of the oxidative stress hypothesis. The average 8-iso-PGF2α in men with COPD was similar to that in healthy smokers, in agreement with one previous study [7]. Several factors limit the ability to make meaningful comparisons between the absolute values of urine 8-iso-PGF2α reported in our study and the values reported in other studies. These factors include the use of different biospecimen types (plasma versus urine), the reporting of urine 8-iso-PGF2α without adjusting for creatinine (a marker of kidney function and thus urine production), differences in sample handling and preparation, and differences in participant characteristics that contribute to F2-IsoPs. Keaney et al. reported creatinine-adjusted urine 8-iso-PGF2 in smokers were about 65% higher compared to nonsmokers using data from the Framingham Heart Study [33]. Our findings were comparable in that smokers were about 53% higher on urine 8-iso-PGF2 compared to nonsmokers. While the means of 8-iso-PGF2 were higher in the Framingham Study, other uncontrolled factors including differences in participant characteristics and sample handling and preparation are likely to contribute to differences in absolute values.

Although many prior studies have noted greater risk of disease with higher 8-iso-PGF2α levels, recent studies have demonstrated that 8-iso-PGF2α can be formed by two distinct biosynthesis pathways—enzymatic and chemical lipid peroxidation [34]. Our study aimed to measure the latter, which is mediated by free radicals. While a recent study demonstrated that the 8-iso-PGF2α/PGF2α ratio is enzyme-independent, and thus potentially a better marker of chemical lipid peroxidation, our measurements are limited to 8-iso-PGF2α and we are unable to explore the effect of supplements on the ratio outcome.

In a secondary objective, we investigated the effects of intervention on urine 8-iso-PGF2α concentrations in men with COPD, and in all supplement arms urine 8-iso-PGF2α concentrations were lowered compared to the placebo group. Several prior vitamin E intervention studies in COPD patients with small sample sizes reported lowering of oxidative stress biomarkers other than urine F2-IsoPs [35,36]. Identification of biomarkers for studying effects of treatment on COPD progression is needed [37], and F2-IsoPs deserve further study especially given the elevation of urine 8-iso-PGF2α in this subgroup.

In a secondary objective, we investigated the chain of causation by studying whether the effects of supplement on lung function were mediated by changes in urine 8-iso-PGF2α. Consistent with a previous study that used induced sputum [38], we found a cross-sectional association between 8-iso-PGF2α and FEV1, such that individuals with higher oxidative stress had lower lung function. However, in the current smokers we studied there was no evidence that the previously observed effect of selenium on lung function in the full RAS study [17] was mediated by 8-iso-PGF2α, and, although vitamin E decreased 8-iso-PGF2α in current smokers, there was no effect of vitamin E on lung function endpoints in the full RAS study. The lack of evidence for a mediating effect suggests that effects are mediated through pathways other than oxidative stress, and/or that urine 8-iso-PGF2α is not a sensitive marker of tissue-specific oxidative stress in the lung. In addition, without biochemical data, we are limited in our ability to fully consider potential mediation of the observed effect of vitamin E and selenium on lung function by F2-IsoPs.

The randomized controlled trial design is the major strength of this study, and minimizes the chance that our results are due to confounding bias. The proportion of current smokers without COPD who submitted a urine specimen was high and was similar across arms (75–87%) indicating minimal loss of participants, which argues against selection bias affecting our conclusions. Urine 8-iso-PGF2α is both a valid and reliable marker of free-radical lipid peroxidation, thus measurement error is not expected to bias the study findings [3]. Also, F2-IsoPs measure both chronic and acute oxidative stress, as confirmed in studies of smokers comparing F2-IsoPs after an overnight abstinence from smoking and immediately after smoking a cigarette [39]. Minimal diurnal variation in F2-IsoP levels [40] supports the use of a spot urine collection to sufficiently capture a representative value. The use of a urine specimen, rather than plasma, is an added strength of our study; urine F2-IsoPs, compared to plasma values, are proposed to more accurately reflect in vivo lipid peroxidation and to provide a more time-integrated marker [41]. The use of ELISA for F2-IsoP measurement, although less accurate than gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) [42], is expected to correctly rank order participants leading to unbiased estimates of the association of treatment with F2-IsoPs.

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of the study design. Pre-intervention urine specimens were not collected and therefore the change in 8-iso-PGF2α over the intervention period could not be calculated. However, the randomized design leads to the reasonable assumption that baseline 8-iso-PGF2α values were similar across study arms, thus inferences about the effect of intervention can be made in the absence of baseline data. Although F2-IsoPs are widely accepted as the gold-standard biomarker of systemic oxidative stress, other biomarkers, including a metabolite of F2-IsoPs, 15-F2t-IsoP-M, may be more sensitive indicators of endogenous oxidative stress [43]. Our sample was limited to males, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, but since female current smokers have higher F2-IsoPs [7,44], the beneficial effect of vitamin E to lower oxidative stress may be higher in women. We could not reliably estimate intervention effects stratified by smoking intensity, but adding smoking dose to statistical models did not appreciably change the findings. Finally, because both vitamin E and selenium may act as anti- or pro-oxidants, differences in baseline nutriture by study arm could affect the conclusions. However, we found no evidence for differences in average baseline plasma levels of vitamin E (α-tocopherol) or selenium by arm (data not shown). In the full RAS study, the mean (SD) plasma vitamin E was 22.1 μmol/L (9.8) and the mean selenium was 170.7 ng/mL (27.7); it is possible that study populations with lower baseline nutriture may observe different or stronger effects of vitamin E or selenium interventions.

Recent conservative estimates suggest that, in total, US adults suffered from 14 million smoking-attributable major medical conditions in 2009 [45]. Many of these diseases, including COPD, are likely due to the increased oxidative burden conferred by smoking. While smoking cessation and prevention of smoking initiation are the most effective means to reduce this public health burden, over 42 million individuals in the US are smokers [46]. Any effect of nutrients with antioxidant properties to lower systemic oxidative stress and ultimately reduce the smoking-associated burden of disease could have a considerable public health impact. Further study of the potential effect of antioxidants, including overall antioxidant dietary patterns [2] and consumption of individual nutrient supplements as investigated herein, is necessary.

5. Conclusions

Vitamin E lowered a urine biomarker of systemic oxidative stress, 8-iso-PGF2α, in male cigarette smokers. Given reports of potentially harmful health effects of vitamin E supplementation [47,48], the possible benefits of supplementation must be carefully considered in the context of balancing risks and benefits. The consistency of the direction of effects on 8-iso-PGF2α in both vitamin E arms (E alone and E plus selenium), in addition to the increased effect magnitude in sensitivity analyses limited to adherent participants, supports a true effect of long-term vitamin E supplements to lower systemic oxidative stress in cigarette smokers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by the NHLBI (R01HL071022), and SELECT was funded by Public Health Service Grants CA37429 and 5UM1CA182883 from the National Cancer Institute.

We acknowledge the SELECT principal investigators and clinical research associates at each site, whose efforts were critical to the successful completion of RAS. Finally, the authors wish to thank the men who participated in the Respiratory Ancillary Study for their generous contributions of time, which made this research possible. We also acknowledge Ms. Joanna Bailey, Cornell University, for assistance with programming, Drs. Monica L. Bertoia, Kathryn A Ritchie and Paul Nielsen for preparatory work on urine specimen handling and storage, and Ms. Victoria Simon, Human Metabolic Research Unit, Cornell University, for her assistance in receiving, processing and storing the urine specimens, and conducting the assays for this study.

Abbreviations

- F2-IsoP

8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- RAS

The Respiratory Ancillary Study to SELECT

- SELECT

The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunoassay

- BMI

body mass index

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in the first second

- FEF25–75

forced expiratory flow between 25 and 75 percent of the forced vital capacity

- GC/MS

gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose and no conflicts of interest to report.

Clinical trial registry

clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT0063453

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—PAC designed RAS; SML, EK and PJG designed SELECT; PAC, KAG, RKG, JAH collected data; KAG, PAC, RKG, and LB analyzed and interpreted data; KAG, PAC drafted manuscript; PAC has primary responsibility for final content. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

None of the authors had a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mayne ST. Antioxidant nutrients and chronic disease: use of biomarkers of exposure and oxidative stress status in epidemiologic research. J Nutr. 2003;133(3):933S–940SS. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.933S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer KA, Sijtsma FPC, Nettleton JA, Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Shikany JM, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with plasma F2-isoprostanes in an observational cohort study of adults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milne GL, Dai Q, Roberts LJ., II The isoprostanes—25 years later. Biochim, Biophys, Acta (BBA) – Mol Cell Biol Lipids. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrow JD, Hill KE, Burk RF, Nammour TM, Badr KF, Roberts LJ. A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87(23):9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helmersson J, Arnlov J, Vessby B, Larsson A, Alfthan G, Basu S. Serum selenium predicts levels of F2-isoprostanes and prostaglandin F2alpha in a 27 year follow-up study of Swedish men. Free Radic Res. 2005;39(7):763–770. doi: 10.1080/10715760500108513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinnula VL, Ilumets H, Myllärniemi M, Sovijärvi A, Rytilä P. 8-Isoprostane as a marker of oxidative stress in nonsymptomatic cigarette smokers and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(1):51–55. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00023606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross M, Steffes M, Jacobs DR, Jr, Yu X, Lewis L, Lewis CE, et al. Plasma F2-isoprostanes and coronary artery calcification: the CARDIA Study. Clin Chem. 2005;51(1):125–131. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basu S. F2-isoprostanes in human health and diseases: from molecular mechanisms to clinical implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(8):1405–1434. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratico D, Basili S, Vieri M, Cordova C, Violi F, Fitzgerald GA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with an increase in urinary levels of isoprostane F2alpha—III, an Index of Oxidant Stress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(6):1709–1714. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9709066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montuschi P, Collins JV, Ciabattoni G, Lazzeri N, Corradi M, Kharitonov SA, et al. Exhaled 8-isoprostane as an in vivo biomarker of lung oxidative stress in patients with COPD and healthy smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;162(3):1175–1177. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.2001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basu S, Helmersson J, Jarosinska D, Sällsten G, Mazzolai B, Barregård L. Regulatory factors of basal F2-isoprostane formation: Population, age, gender and smoking habits in humans. Free Radic Res. 2009;43(1):85–91. doi: 10.1080/10715760802610851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biernacki WA, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Increased leukotriene B4 and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of patients with exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2003;58(4):294–298. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnabel RB, Lunetta KL, Larson MG, Je Dupuis, Lipinska I, Rong J, et al. The relation of genetic and environmental factors to systemic inflammatory biomarker concentrations. Circ: Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2(3):229–237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.804245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrosino T, Serafini M. Antioxidant modulation of F2-isoprostanes in humans: a systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(9):1202–1221. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.630153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra V, Baines M, Perry SE, McLaughlin PJ, Carson J, Wenstone R, et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on biochemical markers and outcome in critically ill patients. Clin Nutr. 2007;26(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Salisbury C, Graham R, Lyons G, Fenech M. Increased consumption of wheat biofortified with selenium does not modify biomarkers of cancer risk, oxidative stress, or immune function in healthy Australian males. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50(6):489–501. doi: 10.1002/em.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassano PA, Guertin KA, Kristal AR, Ritchie KE, Bertoia ML, Arnold KB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin E and selenium on rate of decline in lung function. Respir Res. 2015;16:35. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0195-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippman SM, Goodman PJ, Klein EA, Parnes HL, Thompson IM, Jr, Kristal AR, et al. Designing the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(2):94–102. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109–112. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.83221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomsen LH, Dirksen A, Shaker SB, Skovgaard LT, Dahlback M, Pedersen JH. Analysis of FEV1 decline in relatively healthy heavy smokers: implications of expressing changes in FEV1 in relative terms. COPD. 2014;11(1):96–104. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.830096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reilly M, Delanty N, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Modulation of oxidant stress in vivo in chronic cigarette smokers. Circulation. 1996;94(1):19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton GW, Traber MG, Acuff RV, Walters DN, Kayden H, Hughes L, et al. Human plasma and tissue alpha-tocopherol concentrations in response to supplementation with deuterated natural and synthetic vitamin E. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67(4):669–684. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Block G, Dietrich M, Norkus EP, Morrow JD, Hudes M, Caan B, et al. Factors associated with oxidative stress in human populations. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):274–285. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrignani P, Panara MR, Tacconelli S, Seta F, Bucciarelli T, Ciabattoni G, et al. Effects of vitamin E supplementation on F(2)-isoprostane and thromboxane biosynthesis in healthy cigarette smokers. Circulation. 2000;102(5):539–545. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Block G, Jensen CD, Morrow JD, Holland N, Norkus EP, Milne GL, et al. The effect of vitamins C and E on biomarkers of oxidative stress depends on baseline level. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(4):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lippman SM, Klein EA, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(1):39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laclaustra M, Stranges S, Navas-Acien A, Ordovas JM, Guallar E. Serum selenium and serum lipids in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Atherosclerosis. 2003–2004;210(2):643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spallholz JE. On the nature of selenium toxicity and carcinostatic activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17(1):45–64. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart MS, Spallholz JE, Neldner KH, Pence BC. Selenium compounds have disparate abilities to impose oxidative stress and induce apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(1–2):42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakkur S, Bostick RM, Roblin D, Ndirangu M, Okosun I, Annor F, et al. Oxidative balance score and oxidative stress biomarkers in a study of Whites, African Americans, and African immigrants. Biomarkers. 2014;19(6):471–480. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.937361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frost-Pineda K, Liang Q, Liu J, Rimmer L, Jin Y, Feng S, et al. Biomarkers of potential harm among adult smokers and nonsmokers in the total exposure study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(3):182–193. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Wilson PW, Lipinska I, Corey D, et al. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(3):434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Wilson PWF, Lipinska I, Corey D, et al. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(3):434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van ’t Erve TJ, Lih FB, Kadiiska MB, Deterding LJ, Eling TE, Mason RP. Reinterpreting the best biomarker of oxidative stress: the 8-iso-PGF(2alpha)/PGF(2alpha) ratio distinguishes chemical from enzymatic lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;83:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agacdiken A, Basyigit I, Özden M, Yildiz F, Ural D, Maral H, et al. The effects of antioxidants on exercise-induced lipid peroxidation in patients with COPD. Respirology. 2004:38–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2003.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daga MK, Chhabra R, Sharma B, Mishra TK. Effects of exogenous vitamin E supplementation on the levels of oxidants and antioxidants in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Biosci. 2003;28(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02970125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cazzola M, Novelli G. Biomarkers in COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Therapeuctics. 2010;23(6):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood LG, Garg ML, Simpson JL, Mori TA, Croft KD, Wark PAB, et al. Induced sputum 8-isoprostane concentrations in inflammatory airway diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(5):426–430. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1010OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seet RCS, Lee CYJ, Loke WM, Huang SH, Huang H, Looi WF, et al. Biomarkers of oxidative damage in cigarette smokers: Which biomarkers might reflect acute versus chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(12):1787–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helmersson H, Basu S. F2-Isoprostane excretion rate and diurnal variation in human urine, Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids. 1999;61(3):203–205. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nourooz-Zadeh J. Key issues in F2-isoprostane analysis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(5):1060–1065. doi: 10.1042/BST0361060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Il’yasova D, Morrow JD, Ivanova A, Wagenknecht LE. Epidemiological marker for oxidant status: comparison of the ELISA and the gas chromatography/mass spectrometry assay for urine 2,3-dinor-5,6-dihydro-15-F2t-isoprostane. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(10):793–797. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorjgochoo T, Gao Y-T, Chow W-H, Shu X-o, Yang G, Cai Q, et al. Major metabolite of F2-isoprostane in urine may be a more sensitive biomarker of oxidative stress than isoprostane itself. Am J Clin Nutr. :405–414. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hakim IA, Harris R, Garland L, Cordova CA, Mikhael DM, Sherry Chow HH. Gender difference in systemic oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity in current and former heavy smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 21(12):2193–2200. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostron BL, Chang CM, Pechacek TF. Estimation of cigarette smoking—attributable morbidity in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klein EA, Thompson IM, Tangen CM, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(14):1549–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(15):1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.