This study is the first to demonstrate that a maternal high-fat diet further impairs cardiac function in offspring of diabetic pregnancy through metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Findings serve as a critical step in understanding the role of cellular bioenergetics in developmentally programmed cardiac disease.

Keywords: cardiac bioenergetics, developmental programming, diabetic pregnancy, maternal high-fat diet, mitochondrial dysfunction, diabetic cardiomyopathy, proton production rate

Abstract

Offspring of diabetic pregnancies are at risk of cardiovascular disease at birth and throughout life, purportedly through fuel-mediated influences on the developing heart. Preventative measures focus on glycemic control, but the contribution of additional offenders, including lipids, is not understood. Cellular bioenergetics can be influenced by both diabetes and hyperlipidemia and play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of adult cardiovascular disease. This study investigated whether a maternal high-fat diet, independently or additively with diabetes, could impair fuel metabolism, mitochondrial function, and cardiac physiology in the developing offspring's heart. Sprague-Dawley rats fed a control or high-fat diet were administered placebo or streptozotocin to induce diabetes during pregnancy and then delivered offspring from four groups: control, diabetes exposed, diet exposed, and combination exposed. Cardiac function, cellular bioenergetics (mitochondrial stress test, glycolytic stress test, and palmitate oxidation assay), lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial histology, and copy number were determined. Diabetes-exposed offspring had impaired glycolytic and respiratory capacity and a reduced proton leak. High-fat diet-exposed offspring had increased mitochondrial copy number, increased lipid peroxidation, and evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Combination-exposed pups were most severely affected and demonstrated cardiac lipid droplet accumulation and diastolic/systolic cardiac dysfunction that mimics that of adult diabetic cardiomyopathy. This study is the first to demonstrate that a maternal high-fat diet impairs cardiac function in offspring of diabetic pregnancies through metabolic stress and serves as a critical step in understanding the role of cellular bioenergetics in developmentally programmed cardiac disease.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This study is the first to demonstrate that a maternal high-fat diet further impairs cardiac function in offspring of diabetic pregnancy through metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Findings serve as a critical step in understanding the role of cellular bioenergetics in developmentally programmed cardiac disease.

the prevalence of diabetes and obesity during pregnancy is increasing at an astounding rate (15), and the effects extend beyond those of the mother to the developing fetus. In the US, up to 18% of all pregnancies are now affected by diabetes (52), and 35% of women are obese (23), a comorbidity that increases health risks (36). Infants born to obese or diabetic mothers are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease at birth (29, 51, 59) and throughout life (22, 54), purportedly through fuel-mediated influences (5, 10, 24). Current preventative measures focus on glucose control (2). However, women with good glycemic control also have affected infants (1, 34, 51, 64), implicating additional contributing fuels, such as lipids (10, 30). The relative contribution of excess circulating lipids to the pathogenesis of cardiac disease in offspring of diabetic pregnancies is not well understood or studied.

We hypothesized that maternal dyslipidemia during pregnancy, especially in combination with diabetes, contributes to metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the developing fetal heart, thereby increasing the risk of cardiac dysfunction. Pregnancy is associated with a normal physiological hyperlipidemia, which is exaggerated with diabetes (30). This abnormal maternal metabolic milieu exposes the developing fetus to increased circulating glucose and lipids, which stimulate fetal hyperinsulinemia and may have negative consequences on the developing fetal heart. A maternal diet that is high in fat would add to lipotoxic effects. In adults with diabetes and obesity, increased circulating levels of metabolic fuels, including both glucose and lipids, and impaired insulin activity may lead to diabetic cardiomyopathy. Adult diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterized by diastolic and then systolic dysfunction, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure that is relatively independent of other vascular risk factors (9, 25). Lipid droplet accumulation is found on biopsy, which is suggestive of a lipid-mediated etiology (9, 26, 46). It is certainly plausible that excess circulating maternal fuels and fetal hyperinsulinemia trigger a similar process in the developing heart. Indeed, infants born to mothers with diabetes and obesity have similar cardiac findings at birth, even when glycemic control is good (1, 34, 51, 64), also suggesting that lipids play an underrecognized role (9, 30).

The proposed pathogenic mechanism of adult diabetic cardiomyopathy involves abnormal cardiac metabolism followed by oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and mitophagy (9, 16, 21, 25, 26). It is increasingly recognized that cellular bioenergetics play a pivotal role in the maintenance of health and pathophysiology of disease (62), especially in the heart (12). Because of its high energy demands, the heart requires a constant fuel source for continued contractile activity, making it prone to failure from metabolic abnormalities and mitochondrial dysfunction (58). Fatty acids are a major source of energy for the normal, resting adult heart (26, 28, 41, 42). Despite this preference, the heart has a remarkable ability to utilize various substrates depending on supply and demand. This fuel flexibility allows ongoing energy production under various metabolic conditions including ischemia (oxygen supply), starvation (fuel supply), and exercise (demand) and even during developmental maturation (28, 31, 58). Impaired fuel flexibility from excess circulating fuels and insulin resistance makes the heart prone to failure (12, 26). We hypothesized that a similar pathogenesis could affect offspring of diabetic pregnancies.

The objective of this study was to determine whether a maternal high-fat (HF) diet and diabetes, either independently or additively, impair metabolic fuel flexibility, mitochondrial function, and cardiac physiology in the developing offspring's heart. Utilizing a rat model of partially treated diabetes developing during later gestation in combination with control (CD) or HF diet, we simulated the adverse metabolic and cardiac consequences experienced by infants of diabetic mothers. To test our hypothesis, we measured cardiac function, cellular bioenergetics (mitochondrial stress test, glycolytic stress test, and palmitate oxidation assay), lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial histology, and copy number in newborn rat pups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Care

This study followed guidelines set forth by the Animal Welfare Act and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was under approval from the Sanford Research Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled, light-dark cycled facility with free access to water and chow. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) received CD (TD2018 Teklad; Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) or HF (TD95217 custom diet Teklad; Harlan Laboratories) diet for at least 28 days prior to breeding to simulate a dietary “lifestyle.” Diets were selected to equate commonly attainable low-fat (18% of calories as fat) or HF (40% of calories as fat) diet with more saturated and monounsaturated fat content. Dietary differences are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Caloric content of maternal control and high-fat diets

| Diet | kcal/g | %kcal Fat | %kcal Protein | %kcal Carbohydrate | Fat Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 3.1 | 18 | 24 | 58 | Soybean oil |

| HF | 4.3 | 40 | 19 | 41 | Vegetable shortening, milk fat, soybean oil |

Dietary content of maternal control (CD) and high-fat (HF) diets is detailed. Dams are placed on specified diets for 28 days prior to breeding and throughout pregnancy.

Table 2.

Fatty acid composition of maternal diets

| Diet | Lauric 12:0 | Myristic 14:0 | Palmitic 16:0 | Stearic 18:0 | Oleic 18:1 | LA 18:2n6 | ALA 18:3n3 | ARA 20:4n6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 0.32 | 0.07 | 6.8 | 1.6 | 12 | 29 | 3 | 0 |

| HF | 1.24 | 5 | 32 | 18 | 81 | 35 | 4 | 0.04 |

| Difference | 4.7-fold | 11.3-fold | 6.8-fold | ω–3:6 ratio 9.67 vs. 8.73 | ||||

Fatty acid composition (wt:wt, %) of maternal CD and HF diets is detailed. Dams are placed on specified diets for 28 days prior to breeding and throughout pregnancy.

LA, linoleic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; ARA, arachidonic acid.

Females were bred with normal, CD-fed males. Gestational day 0 was designated by a positive swab for spermatozoa. On gestational day 14, dams received either 0.09 M citrate buffer (CB) placebo or 65 mg/kg of intraperitoneal streptozotocin (STZ) (Sigma Life Sciences, St. Louis, MO) in CB to induce diabetes. The timing of diabetes induction was selected to study the effects of developing diabetes during later gestation while avoiding glucose-mediated teratogenic influences on early organogenesis (3). This is because diabetes during early pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of structural heart defects (11, 38) that could confound cardiovascular outcomes in exposed offspring. After STZ injection, twice-daily glucose concentrations were measured by tail nick sampling with a One Touch Ultra meter (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA). Maternal β-hydroxybutyrate levels were measured concurrently each morning with a Precision Xtra Ketone Meter (Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA). Sliding-scale subcutaneous Humulin R (100 U/ml; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) was administered in the morning and Lantus recombinant insulin glargine (100 U/ml; Sanofi Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ) in the evening to keep glucose levels in a target range of 200–400 mg/dl and ketosis to a minimum. Dams that received STZ but did not manifest significant hyperglycemia (nonfasting blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl) were excluded. Dams delivered spontaneously (on gestational day 22) to yield newborn offspring in four distinct groups: CD-CB (control), CD-STZ (diabetes exposed), HF-CB (HF diet exposed), and HF-STZ (combination exposed).

Plasma Analyses

Blood was collected by venipuncture at baseline, postdiet, gestational day 14, and postpartum time points in dams and immediately after humane euthanasia by cervical dislocation in newborn pups. Aliquots of whole blood and plasma fractions were stored at −80°C until analyses. Plasma triglyceride levels were measured with a Triglyceride Colorimetric Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and nonesterified fatty acid levels were measured with a Wako HR Series NEFA-HR (2) Colorimetric Kit (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA). Both were quantitated with a SpectraMax Plus plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Plasma leptin, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations were measured with the Milliplex MAP Rat Metabolic Magnetic Bead Panel and analyzed with the Luminex 200 Milliplex Analyzer according to the manufacturer's directions.

Echocardiography

Structural and functional cardiac physiology was evaluated by echocardiography with the Vevo2100 high-frequency imaging system (VisualSonics, SonoSite, Toronto, ON, Canada) equipped with heated stage. Echocardiography was done under light isoflurane anesthesia with temperature and EKG monitoring to ensure physiological stability. Images were captured in B mode (brightness mode), M mode (motion mode) and pulsed-wave (PW) Doppler mode with parasternal long axis (PLAX), parasternal short axis (PSAX), and the apical four chamber views and analyzed with the Vevo2100 Imaging System Software to assess ventricular size and systolic and diastolic function. Reported ventricular measurements and systolic function are from left ventricular trace in PLAX views. Diastolic function is reported from PSAX analyses.

Cardiac Lipid Droplet Analysis

After harvest, newborn rat hearts were weighed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C prior to batch staining for lipid droplet analyses. Frozen sections (10 μm) were fixed in 40% formaldehyde, stained in Oil Red O for 10 min followed by background staining with hematoxylin containing acetic acid, and blued in ammonia water. Sections were mounted with aqueous mounting medium. With a uniform approach for all samples, four regions of each left ventricle (anterior wall, septum, posterior wall, and outer wall) were imaged systematically at ×60 using a Nikon 90i microscope with a programmable motorized stage (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Images were captured with a 25-μm grid overlay using NIS-Elements software. Lipid droplets were counted with a point counting method. The average number of lipid droplets touching the grid in each of the four ventricular sections was determined for each heart.

Neonatal Cardiomyocyte Isolation

Hearts were harvested and neonatal cardiomyocytes were isolated from three or four littermates as previously described (48, 55). In summary, hearts were digested in a mixture of 0.1% trypsin and 0.02% DNase (in 0.15 M NaCl) and filtered into bovine serum. After pelleting, cells were resuspended in DMEM-1 [supplemented with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin] with 0.0002% DNase and then incubated for 1 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cardiomyocytes were detached, resuspended in DMEM-1, counted, plated at a seeding density of 150,000 cells/well in 0.1% gelatin-coated Seahorse V7-PS microplates, and then incubated overnight at 5% CO2 at 37°C with DMEM-2 (DMEM-1 supplemented with 100 μM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) medium.

Extracellular Flux Analyses

Mitochondrial stress test, glycolytic stress test, and palmitate oxidation assay were completed on primary neonatal cardiomyocytes from each litter by real-time extracellular flux analyses with a Seahorse XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA) as previously described (17, 47, 50, 53a). Specifically, oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured under the following specified conditions.

Mitochondrial stress test.

OCR, an indicator of mitochondrial respiration, was measured on 150,000 plated cells in XF assay medium (Seahorse Bioscience no. 100965-000) supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 1 mM pyruvate. Measurements were taken at baseline and after timed injections of 2 μM oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor), 0.3 μM carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler), and a mixture of 2 μM rotenone (respiratory complex I inhibitor) and 4 μM Antimycin A (respiratory complex III inhibitor). Real-time OCR was averaged and recorded three times during each conditional cycle.

Glycolytic stress test.

ECAR was measured on 150,000 plated cells in XF base medium (Seahorse Bioscience no. 102353-100) at baseline and after timed injections of 10 mM glucose (to test glycolytic response to exogenous glucose), 2 μM oligomycin (to stimulate anaerobic glycolysis), and 100 mM 2-deoxyglucose (glycolysis inhibition). The contribution of both lactate (from anaerobic glycolysis) and CO2 production (from cellular respiration) was determined by calculating the proton production rate (PPR) as outlined by Mookerjee et al. (43).

Palmitate oxidation assay.

BSA-conjugated palmitate was prepared as previously described (50). Palmitate oxidation was interrogated by measuring OCR at baseline and after injection of 0.15 mM palmitate-BSA and 40 μM etomoxir to inhibit carnitine-palmitoyl transport and mitochondrial respiration via fatty acid oxidation. Etomoxir injection was repeated to ensure that maximal inhibition was obtained.

Extracellular flux validation.

Experimental optimization was conducted in compliance with the manufacturer's recommendations for Seahorse XF24 (53a). Experimental replicates were normalized to cell count. This was the most appropriate normalization method for this experiment because primary isolated cardiomyocytes are nondividing and require extracellular matrix protein (gelatin) coating of the XF plates for uniform adhesion, making normalization to protein concentration unpredictable. Seeding density was verified by live-cell images to demonstrate a uniform layer of cardiomyocytes per well. Drug optimization for the selected seeding density was also performed under specified conditions for each assay.

Malondialdehyde Assay

Lipid peroxidation products were quantified calorimetrically with a malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit (Abcam no. ab118970). Primary neonatal cardiomyocytes were suspended in XF assay medium (Seahorse Bioscience no. 100965-000) supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 1 mM pyruvate and incubated at 37°C for 1 h before the assay was run to mimic the time point at which basal OCR was measured as described above.

Mitochondrial Histology

Isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes (150,000 cells) were plated in XF assay medium (Seahorse Bioscience no. 100965-000) supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 1 mM pyruvate on 0.1% gelatin-coated 23-mm glass-bottom FluoroDish wells (World Precision Instruments) and stained with the following: 2 μM Hoechst 33342 (AnaSpec AS-83216) for nuclei, 2 μM MitoTracker Green FM (Invitrogen M7514) for mitochondrial localization, and 20 μM tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE; Thermo Fisher Scientific T669) to assess the mitochondrial membrane potential. Cells were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse Ti system at ×60 magnification and analyzed with NIS-Elements imaging software.

Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number

Total DNA was extracted from newborn rat hearts with a standard phenol-chloroform extraction (60). In summary, isolated cardiomyocytes were resuspended in a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS), homogenized, and incubated for 3 h with 20 mg/ml proteinase K and 100 mg/ml RNase A. DNA integrity and concentration were determined by spectrophotometry using an Epoch plate reader (BioTek) and stored at 4°C. Relative mitochondrial DNA copy number was determined by real-time PCR quantitation of the control region (D-loop) of rat mitochondrial DNA as previously described (27). Additionally, a TaqMan assay for mitochondrion-specific cytochrome-c oxidase I (MT-CO1; Entrez Gene ID 26195, Rn03296721_s1, Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY) was performed (49). All reactions were set up in triplicate in Absolute Blue QPCR Mix (Thermo Fisher) and run on a Stratagene Mx3000P (Agilent) thermal cycler per the manufacturer's instructions. A gene-specific standard curve was established with different quantities of rat mitochondrial DNA (ranging from 3.125 to 50 ng/reaction). Relative copy number for each target gene in individual samples (50 ng/reaction) was calculated from the standard curve with MxPro software (Agilent).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Diet-, diabetes-, and interaction-related effects were interrogated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. When the interaction was significant, differences between controls (CD-CB) and each exposed group (CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ) were interrogated via one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test. Changes in dam weight and triglyceride levels over time were analyzed by linear regression analysis. Group data were averaged (CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ) and descriptively expressed as means ± SE. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant in all cases.

RESULTS

Animal Model Characteristics: Maternal HF Diet with Diabetes Exacerbates Maternal Hyperlipidemia and Offspring Hyperinsulinemia

Dams and offspring from 48 litters (with 486 live-born pups) were used to characterize the features of our animal model. Group comparisons are described for each of the following experimental groups in Table 3: CD-CB (control, 12 litters), CD-STZ (diabetes exposed, 13 litters), HF-CB (diet exposed, 12 litters) and HF-STZ (combination exposed, 11 litters). Dams on a HF diet (n = 23) gained an average of 35.6 g more weight than those fed CD (n = 25), and the trend persisted over time (P = 0.002). Diabetic dams had higher whole blood glucose levels, while dams receiving CB had nonfasting blood glucose levels <200 mg/dl regardless of their diet. Dams fed a HF diet had significantly higher leptin and circulating lipid levels, which rose drastically with diabetes induction. Compared with control dams, postpartum triglyceride levels were 2-fold higher in diabetic dams, 3-fold higher in HF-fed dams, and 15-fold higher in HF-STZ dams. Despite significant maternal dyslipidemia, newborn rat pups had no significant difference in circulating triglyceride levels. Pups exposed to both diabetes and HF diet had increased circulating insulin and C-peptide levels, but leptin levels were not different.

Table 3.

Model characteristics

|

P Value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | CD-CB | CD-STZ | HF-CB | HF-STZ | Diet | Diabetes | Interaction |

| Maternal weight gain, g | 28 ± 3.64 | 27 ± 4.24 | 63 ± 13.89 | 47 ± 8.75 | ≤0.001 | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| Late-gestation blood glucose, mg/dl | 91 ± 1.06 | 322 ± 11.1 | 93 ± 1.28 | 348 ± 12.5 | 0.10 | ≤0.001 | 0.15 |

| Late-gestation blood ketone, mg/dl | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.05* | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.11* | 0.04* | ||

| Maternal postpartum triglyceride, mg/dl | 36 ± 5.51 | 71 ± 12.50 | 115 ± 20.43 | 555 ± 221 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Maternal postpartum NEFA, meq/l | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.66 |

| Maternal postpartum leptin, ng/ml | 1.40 ± 0.21 | 1.06 ± 0.17 | 2.90 ± 0.60 | 1.95 ± 0.27 | ≤0.001 | 0.06 | 0.36 |

| Litter size, n | 10.67 ± 1.12 | 10.85 ± 1.16 | 10.73 ± 1.23 | 11.09 ± 1.60 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.94 |

| Offspring birth weight, g | 6.17 ± 0.07 | 6.01 ± 0.08 | 6.00 ± 0.08 | 5.69 ± 0.10 | ≤0.001 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Offspring insulin, pmol/l | 111 ± 14 | 468 ± 157 | 387 ± 116 | 1,224 ± 367 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.23 |

| Offspring C-peptide, ng/ml | 2.70 ± 0.22 | 3.29 ± 0.68 | 1.97 ± 0.19 | 7.47 ± 1.21* | ≤0.001 | ||

| Offspring triglyceride, mg/dl | 93 ± 4.29 | 102 ± 10.77 | 114 ± 15.49 | 91 ± 10.53 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.12 |

| Offspring NEFA, meq/l | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.02* | 0.02 | ||

| Offspring heart-to-body wt ratio | 0.007 ± 0.0001 | 0.008 ± 0.0002 | 0.009 ± 0.0003 | 0.009 ± 0.0003 | ≤0.001 | 0.05 | 0.87 |

Values are means ± SE.

CD-CB, control; CD-STZ, diabetes induced; HF-CB, high-fat diet fed; HF-STZ, high-fat fed and diabetes induced; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acid. Significant values in boldface.

Remains significant by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnett's posttest when interaction effect is significant by 2-way ANOVA.

Echocardiography: Offspring Exposed to Maternal HF Diet and Diabetes Had Impaired Systolic and Diastolic Cardiac Function

Newborn offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet (P < 0.0001) had a larger mean heart-to-body weight ratio by morphometric measures [CD-CB 0.0071 ± 0.0002, n = 68; CD-STZ 0.0077 ± 0.0002, n = 77; HF-CB 0.0089 ± 0.0003, n = 89; HF-STZ 0.0094 ± 0.0003, n = 66]. However, left ventricular hypertrophy was not confirmed by echocardiography (Table 4). Systolic and diastolic function for each newborn rat is detailed in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Together, combination-exposed offspring had the poorest systolic and diastolic function with a significantly lower mean heart rate, ejection/shortening fraction (a marker of systolic function), and E:A (a measure of ventricular filling/compliance and a marker of diastolic function).

Table 4.

Summarized echocardiographic left ventricular measurements

| Group | n | IVSd, mm | IVSs, mm | LVPWd, mm | LVPWs, mm | LVIDd, mm | LVIDs, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-CB | 108 | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.53 (0.01) | 0.66 (0.06) | 2.26 (0.03) | 1.47 (0.03) |

| CD-STZ | 122 | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.01) | 0.51 (0.01) | 0.60 (0.01) | 2.19 (0.04) | 1.40 (0.04) |

| HF-CB | 98 | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.58 (0.01) | 0.50 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.01) | 2.21 (0.04) | 1.42 (0.04) |

| HF-STZ | 62 | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.59 (0.02) | 0.50 (0.02) | 0.61 (0.01) | 2.18 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.05) |

Values are means (SE).

IVS, intraventricular septum; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall; LVID, left ventricular internal diameter; d, during diastole; s, during systole.

Table 5.

Summarized echocardiographic systolic measurements

| Group | n | HR, beats/min | SV, μl | EF, % | SF, % | CO, ml/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-CB | 108 | 270 (2.98) | 11.34 (0.49) | 61.01 (1.21) | 24.33 (0.98) | 3.11 (0.16) |

| CD-STZ | 122 | 268 (3.27) | 10.79 (0.42) | 63.23 (1.32) | 21.11 (0.97)± | 3.03 (0.15) |

| HF-CB | 98 | 258 (3.59)* | 10.70 (0.40) | 62.95 (1.37) | 24.78 (0.86) | 2.85 (0.14) |

| HF-STZ | 62 | 259 (5.45)* | 10.08 (0.77) | 58.90 (1.95)^ | 23.67 (1.19)± | 2.73 (0.25) |

Values are means (SE).

HR, heart rate; SV, stroke volume; EF, ejection fraction; SF, shortening fraction {calculated as %SF = [(LVDd − LVDs)/LVDd] × 100, where LVD is left ventricular diameter}; CO, cardiac output. Significant differences:

dietary effect (P ≤ 0.05), ±diabetes effect (P ≤ 0.05), înteraction effect (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 6.

Summarized echocardiographic diastolic measurements

| Group | n | E:A, mm/s (ratio) | IVRT, ms | IVCT, ms | MVET, ms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-CB | 108 | 0.75 (0.02) | 30.43 (0.89) | 22.13 (0.96) | 100 (3.01) |

| CD-STZ | 122 | 0.69 (0.01)± | 33.09 (0.87) | 22.00 (0.84) | 99 (2.32) |

| HF-CB | 98 | 0.70 (0.17)* | 33.04 (1.24) | 25.20 (0.98)* | 103 (2.30) |

| HF-STZ | 62 | 0.66 (0.02)*± | 31.77 (1.16) | 23.00 (0.99)* | 100 (2.82) |

Values are means (SE). Significant differences:

dietary effect (P ≤ 0.05),

diabetes effect (P ≤ 0.05).

E, early ventricular filling; A, ventricular filling from atrial contraction; IVRT, isovolumetric relaxation time; IVCT, isovolumetric contraction time; MVET, mitral valve ejection time.

Lipid Droplet Analysis: Lipid Droplets Accumulate in HF Diet-Exposed Newborn Hearts

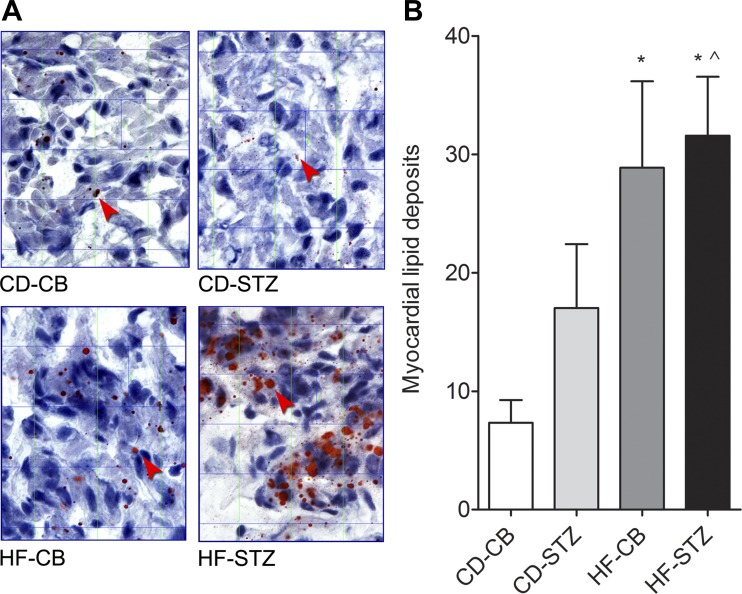

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, newborn pups exposed to a maternal HF diet, especially in combination with diabetes, had an increased number and size of lipid droplets in ventricular sections. Diet accounted for a 173% increase in lipid droplets, while diabetes accounted for a 57% increase. The interaction was significant.

Fig. 1.

Lipid droplet analysis. A: Oil Red O staining of newborn rat hearts from each group (10-μm left ventricular sections at ×60) shows red lipid droplets indicated by arrowheads. CD-CB, control; CD-STZ, diabetes exposed; HF-CB, high-fat (HF) diet exposed; HF-STZ, combination exposed. Note that in HF diet-exposed hearts, especially in combination with diabetes, the lipid droplets increase in both number and size. B: point counting of lipid droplets revealed a significant interaction effect by 2-way ANOVA (^P = 0.01). Offspring from HF-CB and HF-STZ groups had significantly more droplets compared with controls by 1-way ANOVA posttest (*P < 0.05).

Mitochondrial Stress Test: Offspring Exposed to Maternal Diabetes and HF Diet Have Impaired Cardiac Mitochondrial Respiration

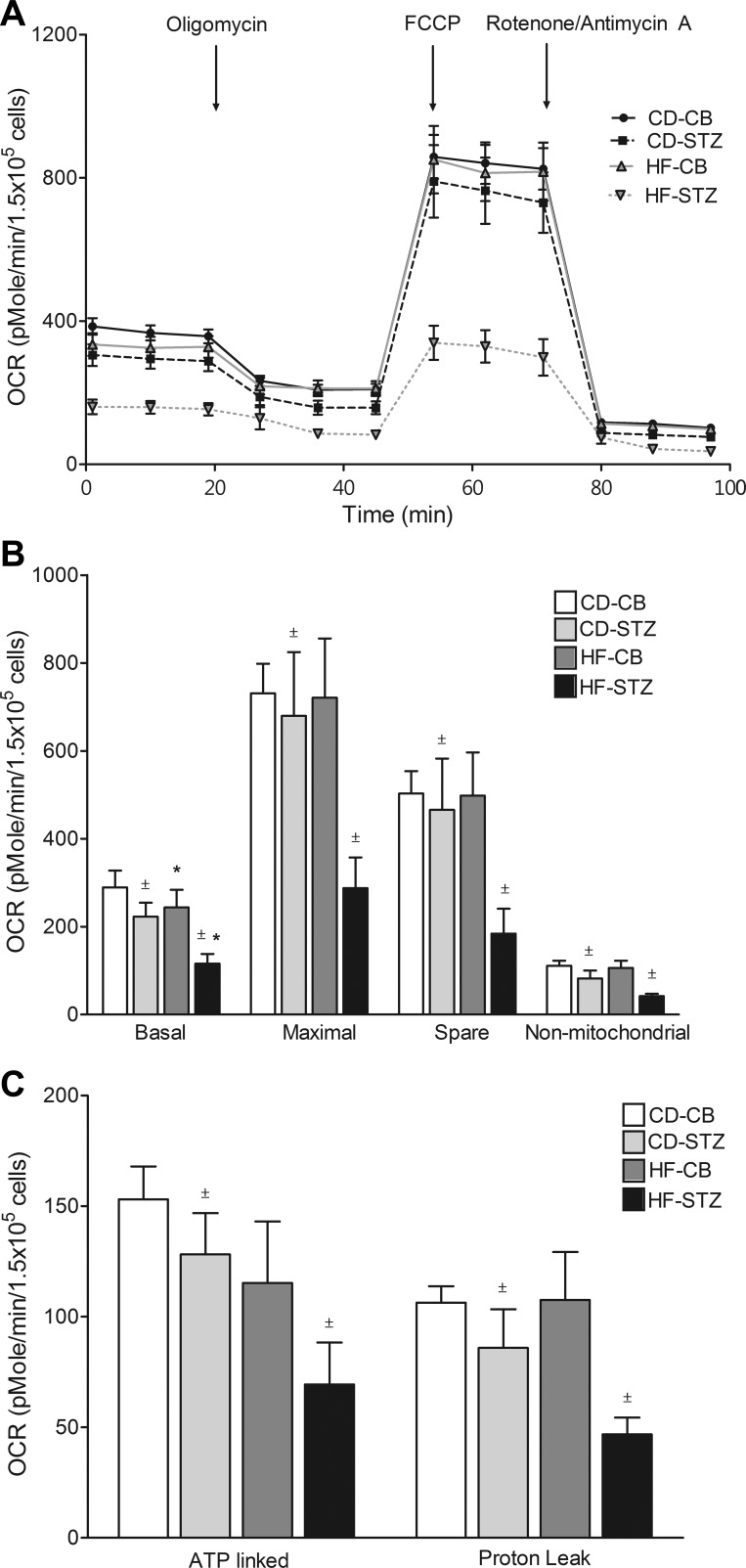

Real-time OCR during mitochondrial stress testing is illustrated for neonatal cardiomyocytes from each group in trace (Fig. 2A) and bar (Fig. 2B) formats in Figure 2. Diabetes-exposed cardiomyocytes had significantly lower basal, maximal, spare, and nonmitochondrial OCR consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction. ATP-linked and proton leak OCR were also lower. Additionally, HF diet-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had lower basal OCR. Combination-exposed (HF-STZ) neonatal cardiomyocytes demonstrated the poorest mitochondrial respiration.

Fig. 2.

Mitochondrial stress test. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) trace (A) and bar graphs (B and C) illustrate mitochondrial respiration under various conditions. Diabetes-exposed cardiomyocytes have lower basal, maximal, spare, nonmitochondrial, ATP-linked, and proton leak OCR. HF diet-exposed cardiomyocytes have significantly lower basal OCR. Combination-exposed cardiomyocytes consistently display the lowest mitochondrial respiration of all groups. Values are means ± SE; n = 5–7 litters/group. Significant differences: *dietary effect, ±diabetes effect (P ≤ 0.05).

Glycolytic Stress Test: Diabetes-Exposed Offspring Have Decreased Cardiac Glycolytic Capacity

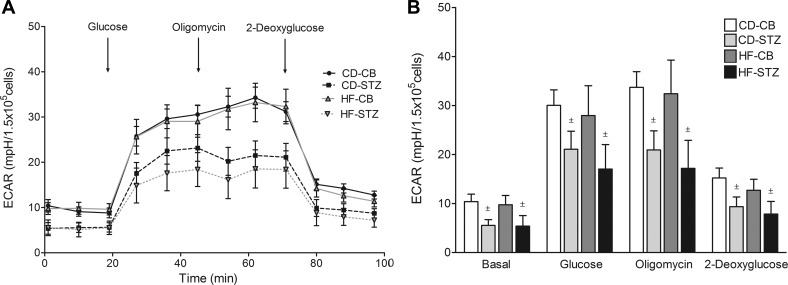

Real-time ECAR, a marker of anaerobic glycolysis, is illustrated for neonatal cardiomyocytes from each group in trace (Fig. 3A) and bar (Fig. 3B) formats in Figure 3. Diabetes-exposed cardiomyocytes had significantly lower basal, glucose-stimulated, and oligomycin-stimulated glycolytic capacity. Although the combination-exposed group had the lowest glycolytic response, no significant interaction effect was found.

Fig. 3.

Glycolytic stress test. Extracellular acidification (ECAR) trace (A) and bar graphs (B) illustrate the glycolytic response of newborn cardiomyocytes to glucose, oligomycin, and 2-deoxyglucose from CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ offspring. Diabetes-exposed offspring had lower basal, glucose-stimulated, and oligomycin-stimulated ECAR regardless of diet exposure. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–7 litters/group. ±P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA.

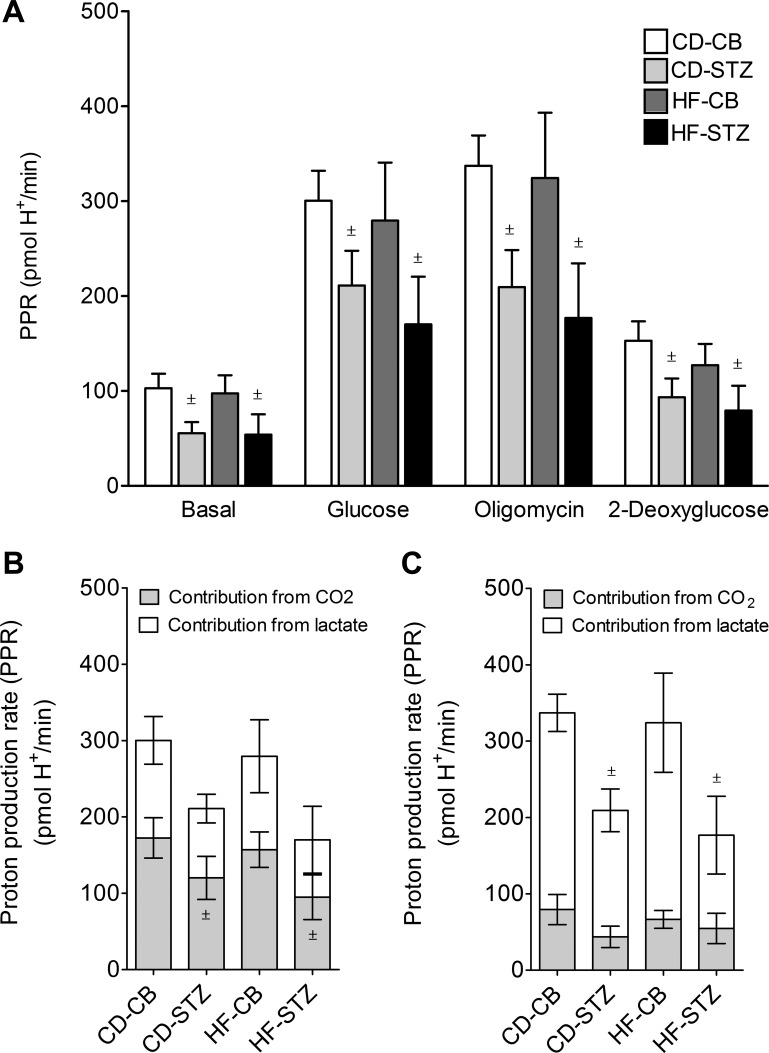

Determining the PPR as described previously (43) allowed us to confirm that differences in ECAR were due to a decreased capability for anaerobic glycolysis (Fig. 4). Indeed, diabetes-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had a lower PPR under basal, glucose-stimulated, and oligomycin-stimulated conditions, suggesting a decreased glycolytic capacity. After glucose stimulation, the contribution of lactate from anaerobic glycolysis was significantly lower in diabetes-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes. There was no difference in the contribution of Krebs cycle CO2 (aerobic respiration) to ECAR with glucose stimulation. It was anticipated that oligomycin, an inhibitor of ATP production through cellular respiration, would stimulate anaerobic glycolysis in all cardiomyocytes. Unexpectedly, ECAR actually decreased in diabetes-exposed cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3). Upon further analyses, we found that this was due to a decreased contribution of CO2 (aerobic respiration) to the total PPR after oligomycin injection (Fig. 4C). This substantiates that cardiac fuel flexibility is impaired in offspring of diabetic mothers because of a decreased ability to utilize glucose for ATP production even when mitochondrial respiration is inhibited.

Fig. 4.

Proton production rate (PPR). A: calculated (43) PPR for neonatal cardiomyocytes under basal, glucose-stimulated, oligomycin-stimulated, and 2-deoxyglucose-inhibited conditions is represented for CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ offspring. B and C: the contributions of both lactate from anaerobic glycolysis and CO2 production from cellular respiration during glucose stimulation (B) and oligomycin stimulation (C) confirm a decreased glycolytic capacity in diabetes-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes. Diabetes exposure was associated with lower lactate production from anaerobic glycolysis under glucose stimulation and with lower CO2 production from aerobic respiration under oligomycin stimulation consistent with impaired cardiac fuel flexibility. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–7 litters/group. ±P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA.

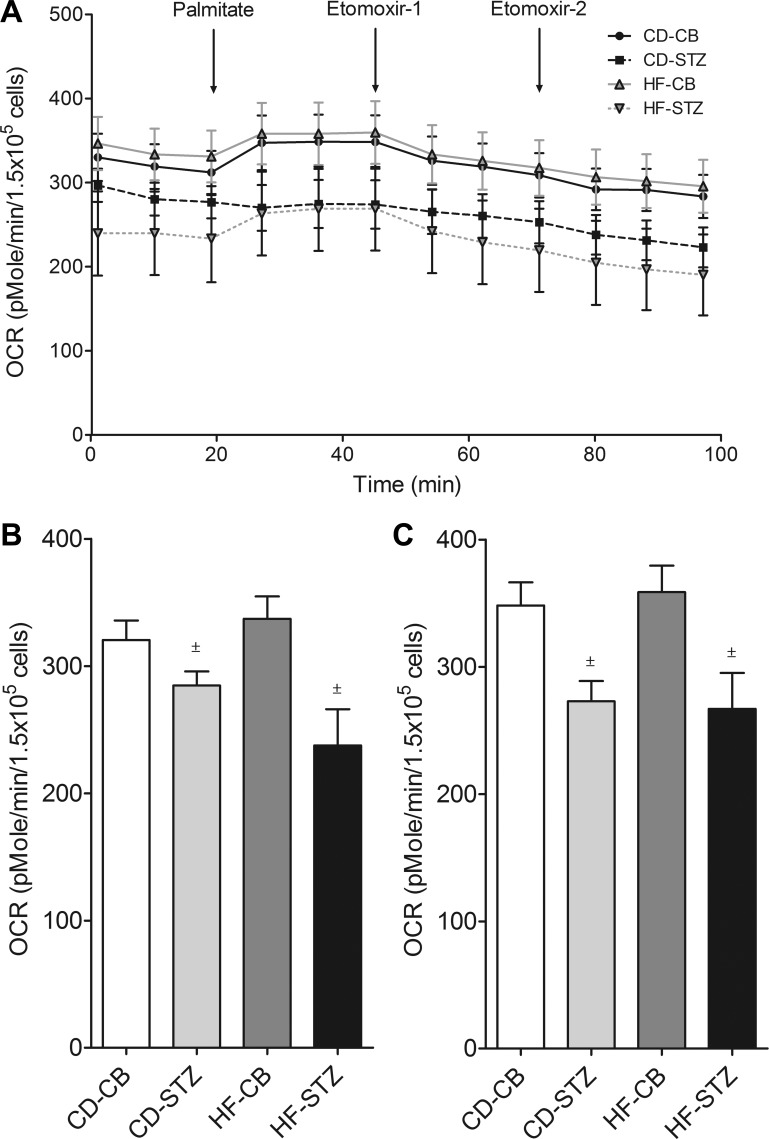

Palmitate Oxidation Assay: Combination-Exposed Offspring Have Lower Basal and Maximal OCR Despite Response to Exogenous Palmitate

Real-time OCR in response to exogenous palmitate serves as a marker of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and is illustrated in trace format (Fig. 5A) and bar format for basal (Fig. 5B) and palmitate response (Fig. 5C) for each group in Figure 5. Neonatal cardiomyocytes from diabetes-exposed offspring had a lower response to exogenous palmitate. Combination-exposed (HF-STZ) neonatal cardiomyocytes had a very low basal OCR, so despite increased respiration to exogenous palmitate maximal OCR never increased to that of the other groups.

Fig. 5.

Palmitate oxidation test. OCR trace (A) and bar graphs depict mitochondrial respiration at basal (B) and palmitate-stimulated (C) rates from CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ offspring. Etomoxir, a carnitine-fatty acid transport inhibitor, was given and repeated to ensure maximal inhibition of exogenous fatty acid oxidation. Diabetes-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had lower basal (B) and palmitate-stimulated (C) OCR. In HF-STZ offspring maximal OCR remains lower than all other groups despite a response to exogenous palmitate (A). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–7 litters/group. ±P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA.

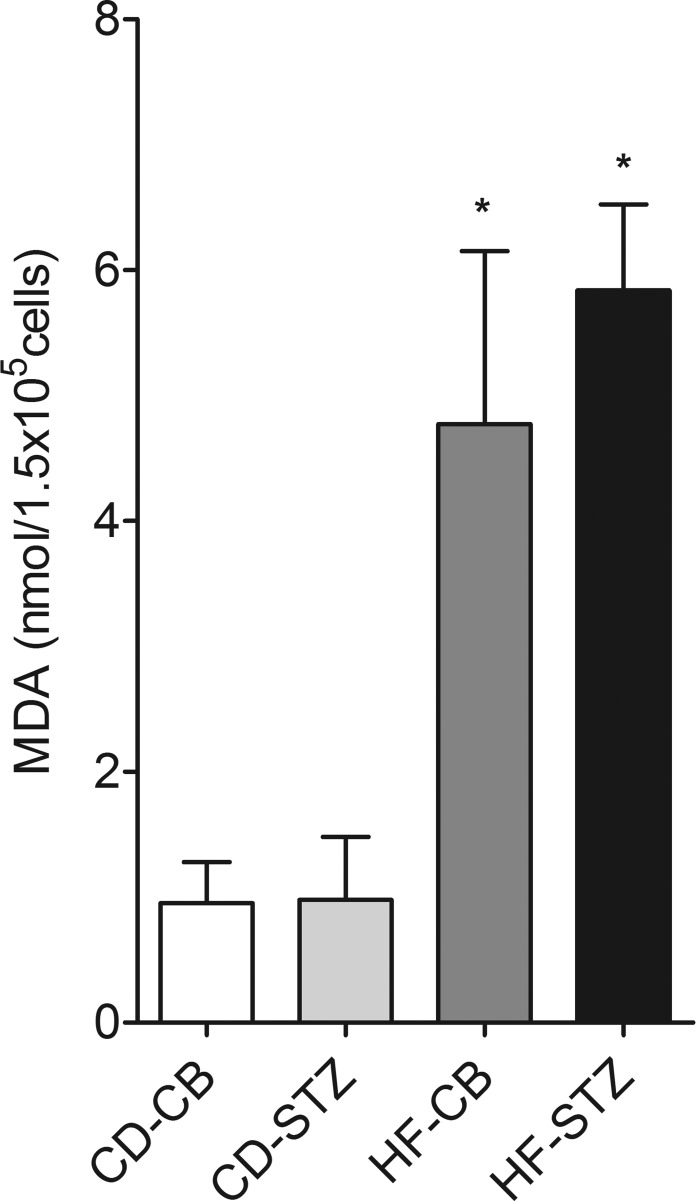

MDA Assay: HF Diet-Exposed Offspring Have Evidence of Cardiac Lipid Peroxidation

Exposure to a maternal HF diet (P ≤ 0.0001), but not diabetes (P = 0.53), was associated with increased MDA levels in isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes, which indicates oxidative stress through lipid peroxidation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Lipid peroxidation in newborn cardiomyocytes. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, as a marker of oxidative stress, were higher in cardiomyocytes from offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet (HF-CB and HF-STZ) but not diabetes alone (CD-STZ). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 4 or 5 litters/group. *P ≤ 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA.

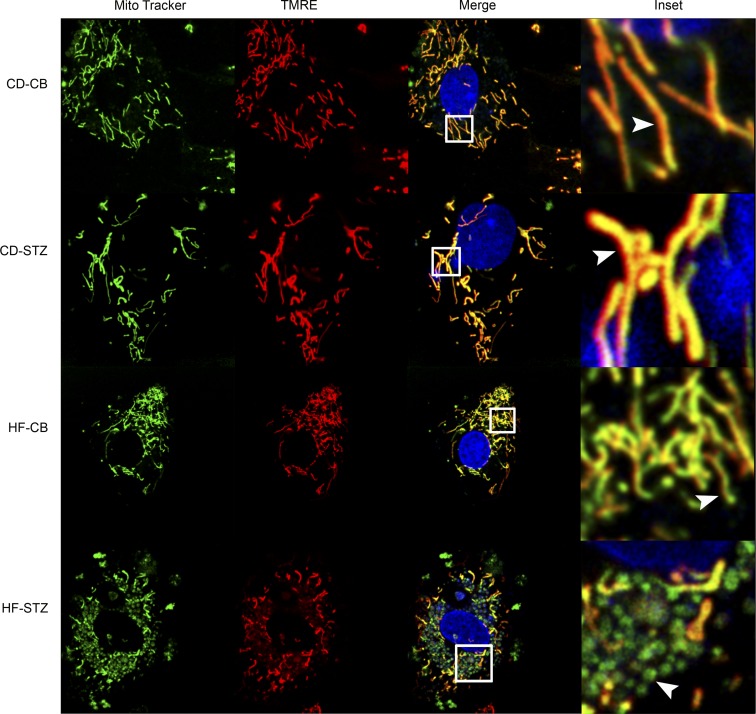

Mitochondrial Histology: Combination-Exposed Offspring Have Abnormal Cardiomyocyte Mitochondrial Structure and Membrane Potential

Isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes stained with MitoTracker Green to identify mitochondria, TMRE to identify a charged mitochondrial membrane potential (necessary for ATP production), and Hoechst to identify DNA (both nuclear and mitochondrial) are depicted in Fig. 7. Normal mitochondria are typically long, thin, and abundant in cardiac tissue (40% of cellular components); they are dynamic and constantly undergo fusion and fission (21). When they become adynamic (57) or depolarized (loss of membrane potential) they undergo fragmentation and become susceptible to mitophagy (18). Using live-cell, confocal video imaging, we found long, thin, well-charged, and active mitochondria undergoing fusion and fission in isolated cardiomyocytes from control (CD-CB) offspring. Diabetes-exposed (CD-STZ) neonatal cardiomyocytes had no visibly discernible differences in fusion and fission by video observation, but they seemed to have fewer mitochondria overall. HF diet-exposed (HF-CB) neonatal cardiomyocytes had an increased number of shorter, more fragmented mitochondria, but they maintained their charge and some ability for fusion and fission by video observation. Combination-exposed (HF-STZ) neonatal cardiomyocytes had fragmented, depolarized mitochondria with very little to no movement on live-cell video imaging (see merged image, Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial histology. Isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes from CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ offspring were stained with MitoTracker (mitochondrial identification), tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE, mitochondrial membrane potential/charged mitochondria), and Hoechst (DNA). When images are merged, healthy mitochondria appear long, thin, and well polarized (yellow). Combination-exposed (HF-STZ) mitochondria are fragmented and depolarized (green). Inset shows a magnified view of individual mitochondria for each group (arrowheads).

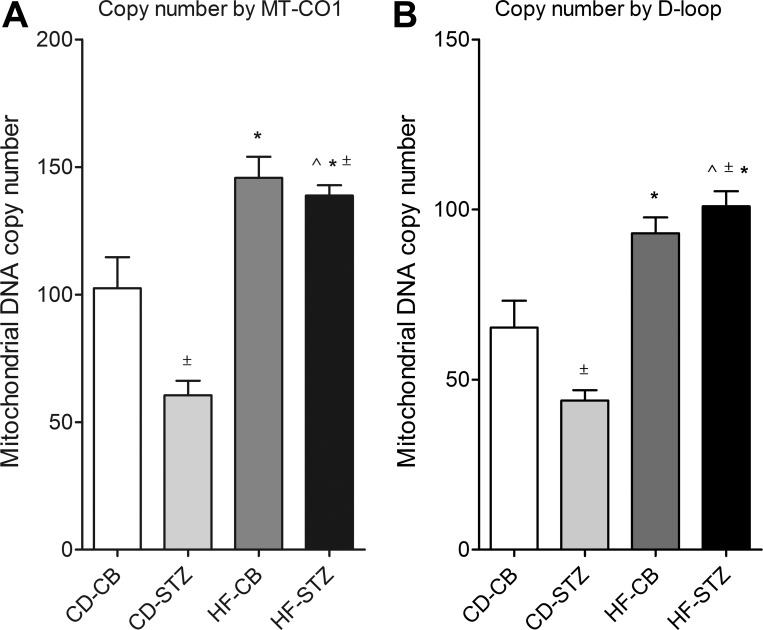

Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number: HF Diet-Exposed Cardiomyocytes Have Higher Mitochondrial Copy Number

To verify observed differences in mitochondrial number seen by histology, mitochondrial DNA copy number was determined by real-time PCR using two distinct primers. Gene expression analyses of the MT-CO1 (Fig. 8A) and D-loop (Fig. 8B) mitochondrial control region demonstrated similar group differences. Diabetes exposure alone (CD-STZ) was associated with a lower mitochondrial copy number than control, but HF diet exposure was associated with a higher copy number. Overall, there was a significant interaction effect.

Fig. 8.

Mitochondrial copy number. Relative mitochondrial DNA copy number was determined by real-time PCR quantitation of mitochondrion-specific cytochrome-c oxidase I (MT-CO1; A) and the control region (D-loop; B) of rat mitochondrial DNA for CD-CB, CD-STZ, HF-CB, and HF-STZ offspring. For both genes, a significant interaction effect was noted by 2-way ANOVA, and all exposed groups had significant differences compared with control by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnett's posttest. Mitochondrial DNA copy number was decreased in diabetes-exposed hearts and increased in HF diet-exposed hearts. Values are means ± SE; n = 16 pups/group. Significant differences: *dietary effect, ±diabetes effect, ^interaction effect (P ≤ 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The contribution of excess circulating fuels, including lipids, to the pathogenesis of developmentally programmed cardiac disease has been proposed (10, 20, 30) but remains poorly understood. It is well known that the triad of insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia in adults causes diabetic cardiomyopathy (9, 25). Infants born to diabetic or obese mothers are at risk of similar heart disease at birth, even if maternal glycemic control is good (1, 34, 49, 61). Epidemiological studies demonstrate that circulating maternal triglyceride levels independently and temporally correlate with both fetal overgrowth and ventricular hypertrophy in offspring of diabetic mothers (1, 19, 33, 53, 56), which suggests a strong lipid-mediated influence. Although previous studies have reported individual effects of maternal diabetes or a HF diet on cardiovascular disease risk (7, 13, 14, 33, 35), our study adds evidence that a maternal HF diet in combination with diabetes is especially detrimental for the developing fetal heart.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that a maternal HF diet further impairs diastolic and systolic function in offspring of diabetic pregnancies through lipid droplet accumulation, metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Using a rat model to identify independent and additive effects, we found that diabetes-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had lower mitochondrial respiratory capacity and glycolytic capacity and a decreased ability to utilize glucose for ATP production even when mitochondrial respiration was inhibited with oligomycin. We suspect that this impairment in cardiac fuel flexibility caused a compensatory decrease in proton leak necessary to maintain an adequate mitochondrial membrane potential, as demonstrated by a lower OCR for proton leak, thereby increasing the risk of damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (8). HF diet-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had lipid droplet accumulation, an increased mitochondrial number, and evidence of increased oxidative stress (lipid peroxidation). Together, combination-exposed neonatal cardiomyocytes had significantly impaired metabolic fuel flexibility, histological evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction, and diastolic and systolic dysfunction on echocardiography.

How does mitochondrial dysfunction impair cardiac function? Mitochondria are the major site for ROS production (9). It is known that electrons can leak from the respiratory chain, leading to production of superoxide, which can be converted to hydrogen peroxide and transformed to very potent hydroxyl radicals that cause damage to macromolecules, including structural lipids (lipid peroxidation) (45). Oxidative stress can lead to further mitochondrial dysfunction, fragmentation, mitophagy, and eventually cell death (18, 56). Mature cardiomyocytes cannot proliferate, and as a result heart failure ensues. This is a proposed primary mechanism contributing to diabetic cardiomyopathy in adults (19, 23). Our findings suggest that a similar pathogenesis contributes to cardiac dysfunction in newborns born to diabetic mothers and that a maternal HF diet increases this risk. In our rat model, cardiomyocytes from combination-exposed (HF-STZ) pregnancies had fragmented and poorly charged mitochondria with little to no fission or fusion seen on live-cell imaging. These characteristics suggest significant injury that may mark cells for apoptosis (18, 57).

If metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction persist beyond the neonatal time point, this could also explain the increased risk of cardiac disease found throughout life in infants born to mothers with diabetes or obesity (22, 44, 54). However, caution should be used in making this inference because significant metabolic differences in cardiac metabolism between fetal and adult time points (39, 42) could exacerbate disease severity, progression, and long-term prognosis. The fetal heart relies predominantly on anaerobic glycolysis to meet ATP demands (40). However, shortly after birth, the placenta is no longer available to provide a continuous supply of nutrients, and the circulating oxygen supply rapidly increases, driving mitochondrial ATP production to sustain cardiac energetic demands with age (58). Indeed, fatty acid oxidation becomes the primary energy source for the normal resting adult heart (41). In the neonatal heart, a rapid increased reliance on aerobic metabolism, alongside a decreased proton leak (or very tightly coupled respiration) and lower spare respiratory capacity (found in HF-STZ neonatal cardiomyocytes), may add to increased oxidative injury. However, with normal metabolic maturation and the heart's robust mitochondrial turnover (61), cardiomyocytes may recover over time. Indeed, this may be why ventricular hypertrophy found in infants of diabetic mothers often regresses in the first months of life. Therefore, future studies are necessary to determine whether there is a lasting consequence that may lead to cardiovascular disease later in life.

Study Limitations

There were several identifiable limitations to our animal model. First, a high perinatal mortality rate in HF diet-exposed offspring (44% in HF-CB and 43% in HF-STZ vs. 9% in CD-CB and 11% in CD-STZ litters) confounded data because only healthy pups could have echocardiography or viable hearts for primary cardiomyocyte isolation and metabolic studies. For this reason, we anticipate that the negative impact of a maternal HF diet is actually greater than reported in our results.

Second, it is well recognized that maternal hyperglycemia, particularly early in the pregnancy (during organogenesis), is associated with structural birth defects including cardiac anomalies (3, 6), which would impact cardiac function in newborn offspring. Gestational diabetes, which typically develops later in pregnancy, is less likely associated with structural heart defects (11). The cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic and systolic dysfunction found in infants of diabetic pregnancies typically develops during this later time frame (51, 63). For these reasons, we induced diabetes on gestational day 14 after organogenesis was complete. Also, both structure and function were assessed on echocardiography. Only one living newborn pup in the HF-CB group had a structural heart defect detected, and functional data for this pup were not included in the final analyses.

Third, diabetes induced by STZ is not a perfect model for either type 1 diabetes (immunologically mediated) or type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance). However, our model allows us to study the effects of maternal hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and fetal hyperinsulinemia on the developing offspring late in gestation (see Table 3). This is important not only because it helps avoid diabetes-related effects on organogenesis but also because the timing coordinates with increased placental lipid transport and fetal pancreatic development/function (insulin secretion) in the latter part of pregnancy. Moreover, women with gestational diabetes are usually not diagnosed or treated until the last trimester, making this a translatable time point for dietary intervention.

Another limitation of our study is that mitochondria were not examined by electron microscopy or other analyses for evidence of mitophagy. Additionally, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was not evaluated. Given our observations on confocal imaging and live-cell video, this is planned in future studies. In addition, it is not yet known whether changes in cardiac metabolism are a cause or compensatory mechanism for heart failure, and while reactive species may be culprits in the decline of myocardial function under conditions of hyperglycemia/hyperlipidemia, the actual cause of dysfunction in myocardial fuel utilization remains unknown. These questions represent areas in desperate need of research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, using a rat model we found that maternal HF diet further impairs cardiac function in offspring of diabetic pregnancy through metabolic abnormalities, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Current measures to prevent the complications of diabetic pregnancy involve vigilant glycemic control (2). However, by itself, better glycemic control does not negate risks to the developing baby (4, 7, 36, 37, 64), including the risk of cardiovascular disease (1, 64). Our study is the first to specifically delineate the role of maternal dietary fat intake in cardiac metabolic health in offspring of diabetic pregnancies. Findings demonstrate a significant detrimental effect from this combination and uncover an underrecognized and targetable risk factor that, when addressed during pregnancy, could improve the lifelong heart health of at-risk infants. Our findings guide further investigation into the role of cellular bioenergetics in developmentally programmed cardiac disease and serve as a crucial step in discovering novel diagnostic, preventative, and therapeutic strategies to improve heart health in infants born after diabetic pregnancy.

GRANTS

The study was financially supported by Sanford Research, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (K08 HD-078504), a Sanford School of Medicine-University of South Dakota Faculty Grant, and a Sanford Health-South Dakota State University Collaborative Research Seed Grant. The project was also supported by two Institutional Development Awards (IDeA) from the NIH, P20 GM-103620-01A1 (Pediatrics) and P20 GM-103548 (Cancer), which support metabolic, molecular genetics, molecular pathology, and imaging core services at Sanford Research. E. J. Larsen was supported under the Sanford Program for Undergraduate Research via National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Experiences for Undergraduates DBI-1262744 and NSF EPSCoR Cooperative Agreement with the State of South Dakota IIA-1355423. A. L. Wachal was supported under the Science Educator Research Fellowship (SERF) via NIH R25 HD-072596.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.S.M. and M.L.B. conception and design of research; K.S.M., T.D.L., A.L.W., M.D.S., L.J.W., S.D.R.D., E.J.L., and M.L.B. performed experiments; K.S.M., A.L.W., M.D.S., and M.L.B. analyzed data; K.S.M. and M.L.B. interpreted results of experiments; K.S.M., T.D.L., M.D.S., and M.L.B. prepared figures; K.S.M. drafted manuscript; K.S.M., T.D.L., A.L.W., M.D.S., S.D.R.D., E.J.L., and M.L.B. edited and revised manuscript; K.S.M., T.D.L., A.L.W., M.D.S., L.J.W., S.D.R.D., E.J.L., and M.L.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Peter Vitiello and Ben Forred for their significant help in XF methods training, Dr. Haotian Zhao for help in mitochondrial quantification, and Dr. Yongxian Zhuang and Dr. Indra Chandrasekar for help in mitochondrial staining and live-cell imaging. We also thank Drs. Jeffrey Segar and Andrew Norris, who serve as mentors for M. L. Baack, for review and suggestions on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aman J, Hansson U, Ostlund I, Wall K, Persson B. Increased fat mass and cardiac septal hypertrophy in newborn infants of mothers with well-controlled diabetes during pregnancy. Neonatology 100: 147–154, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 98: 525–538, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baack ML, Wang C, Hu S, Segar JL, Norris AW. Hyperglycemia induces embryopathy, even in the absence of systemic maternal diabetes: an in vivo test of the fuel mediated teratogenesis hypothesis. Reprod Toxicol 46: 129–136, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsells M, Garcia-Patterson A, Gich I, Corcoy R. Maternal and fetal outcome in women with type 2 versus type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 4284–4291, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker DJ. Rise and fall of Western diseases. Nature 338: 371–372, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becerra JE, Khoury MJ, Cordero JF, Erickson JD. Diabetes mellitus during pregnancy and the risks for specific birth defects: a population-based case-control study. Pediatrics 85: 1–9, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 115: e290–e296, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand MD, Buckingham JA, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, Murphy MP, Pakay JL, Talbot DA, Echtay KS. Mitochondrial superoxide and aging: uncoupling-protein activity and superoxide production. Biochem Soc Symp 2004: 203–213, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia 57: 660–671, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalano PM, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Is it time to revisit the Pedersen hypothesis in the face of the obesity epidemic? Am J Obstet Gynecol 204: 479–487, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correa A, Gilboa SM, Besser LM, Botto LD, Moore CA, Hobbs CA, Cleves MA, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, Waller DK, Reece EA. Diabetes mellitus and birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199: 237.e1–237.e9, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantino S, Paneni F, Cosentino F. Ageing, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol (September 22, 2015). doi: 10.1113/JP270538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabelea D. The predisposition to obesity and diabetes in offspring of diabetic mothers. Diabetes Care 30, Suppl 2: S169–S174, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabelea D, Hanson RL, Lindsay RS, Pettitt DJ, Imperatore G, Gabir MM, Roumain J, Bennett PH, Knowler WC. Intrauterine exposure to diabetes conveys risks for type 2 diabetes and obesity: a study of discordant sibships. Diabetes 49: 2208–2211, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes Care 28: 579–584, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dassanayaka S, Readnower RD, Salabei JK, Long BW, Aird AL, Zheng YT, Muthusamy S, Facundo HT, Hill BG, Jones SP. High glucose induces mitochondrial dysfunction independently of protein O-GlcNAcylation. Biochem J 467: 115–126, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diers AR, Broniowska KA, Darley-Usmar VM, Hogg N. Differential regulation of metabolism by nitric oxide and S-nitrosothiols in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H803–H812, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding WX, Yin XM. Mitophagy: mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biol Chem 393: 547–564, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirix CE, Kester AD, Hornstra G. Associations between neonatal birth dimensions and maternal essential and trans fatty acid contents during pregnancy and at delivery. Br J Nutr 101: 399–407, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong M, Zheng Q, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Ren J. Maternal obesity, lipotoxicity and cardiovascular diseases in offspring. J Mol Cell Cardiol 55: 111–116, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan JG. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 1351–1359, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson JG, Sandboge S, Salonen MK, Kajantie E, Osmond C. Long-term consequences of maternal overweight in pregnancy on offspring later health: findings from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Ann Med 46: 434–438, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 303: 235–241, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freinkel N. Banting Lecture 1980. Of pregnancy and progeny. Diabetes 29: 1023–1035, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuentes-Antras J, Picatoste B, Ramirez E, Egido J, Tunon J, Lorenzo O. Targeting metabolic disturbance in the diabetic heart. Cardiovasc Diabetol 14: 17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg IJ, Trent CM, Schulze PC. Lipid metabolism and toxicity in the heart. Cell Metab 15: 805–812, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grady JP, Murphy JL, Blakely EL, Haller RG, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Tuppen HA. Accurate measurement of mitochondrial DNA deletion level and copy number differences in human skeletal muscle. PloS One 9: e114462, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grynberg A, Demaison L. Fatty acid oxidation in the heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 28, Suppl 1: S11–S17, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatem MA, Zielinsky P, Hatem DM, Nicoloso LH, Manica JL, Piccoli AL, Zanettini J, Oliveira V, Scarpa F, Petracco R. Assessment of diastolic ventricular function in fetuses of diabetic mothers using tissue Doppler. Cardiol Young 18: 297–302, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrera E, Ortega-Senovilla H. Disturbances in lipid metabolism in diabetic pregnancy—are these the cause of the problem? Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 24: 515–525, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E578–E591, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitajima M, Oka S, Yasuhi I, Fukuda M, Rii Y, Ishimaru T. Maternal serum triglyceride at 24–32 weeks' gestation and newborn weight in nondiabetic women with positive diabetic screens. Obstet Gynecol 97: 776–780, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozak-Barany A, Jokinen E, Kero P, Tuominen J, Ronnemaa T, Valimaki I. Impaired left ventricular diastolic function in newborn infants of mothers with pregestational or gestational diabetes with good glycemic control. Early Hum Dev 77: 13–22, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurtz M, Capobianco E, Martinez N, Roberti SL, Arany E, Jawerbaum A. PPAR ligands improve impaired metabolic pathways in fetal hearts of diabetic rats. J Mol Endocrinol 53: 237–246, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer O. Obesity or diabetes: which is more hazardous to the health of the offspring? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 29: 186–190, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leipold H, Worda C, Gruber CJ, Kautzky-Willer A, Husslein PW, Bancher-Todesca D. Large-for-gestational-age newborns in women with insulin-treated gestational diabetes under strict metabolic control. Wien Klin Wochenschr 117: 521–525, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lisowski LA, Verheijen PM, Copel JA, Kleinman CS, Wassink S, Visser GH, Meijboom EJ. Congenital heart disease in pregnancies complicated by maternal diabetes mellitus. An international clinical collaboration, literature review, and meta-analysis. Herz 35: 19–26, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopaschuk GD, Jaswal JS. Energy metabolic phenotype of the cardiomyocyte during development, differentiation, and postnatal maturation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56: 130–140, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopaschuk GD, Spafford MA, Marsh DR. Glycolysis is predominant source of myocardial ATP production immediately after birth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1698–H1705, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev 90: 207–258, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makinde AO, Kantor PF, Lopaschuk GD. Maturation of fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism in the newborn heart. Mol Cell Biochem 188: 49–56, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mookerjee SA, Goncalves RL, Gerencser AA, Nicholls DG, Brand MD. The contributions of respiration and glycolysis to extracellular acid production. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 171–181, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore TR. Fetal exposure to gestational diabetes contributes to subsequent adult metabolic syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202: 643–649, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J 417: 1–13, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakanishi T, Kato S. Impact of diabetes mellitus on myocardial lipid deposition: an autopsy study. Pathol Res Pract 210: 1018–1025, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholls DG, Darley-Usmar VM, Wu M, Jensen PB, Rogers GW, Ferrick DA. Bioenergetic profile experiment using C2C12 myoblast cells. J Vis Exp 2010: 2511, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Connell TD, Simpson RU. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulation of myocardial growth and c-myc levels in the rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 213: 59–65, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Racay P, Tatarkova Z, Drgova A, Kaplan P, Dobrota D. Ischemia-reperfusion induces inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis and cytochrome c oxidase activity in rat hippocampus. Physiol Res 58: 127–138, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Readnower RD, Brainard RE, Hill BG, Jones SP. Standardized bioenergetic profiling of adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Physiol Genomics 44: 1208–1213, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren Y, Zhou Q, Yan Y, Chu C, Gui Y, Li X. Characterization of fetal cardiac structure and function detected by echocardiography in women with normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Prenat Diagn 31: 459–465, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sacks DA, Hadden DR, Maresh M, Deerochanawong C, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Coustan DR, Hod M, Oats JJ, Persson B, Trimble ER, HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group . Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus at collaborating centers based on IADPSG consensus panel-recommended criteria: the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Diabetes Care 35: 526–528, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schaefer-Graf UM, Graf K, Kulbacka I, Kjos SL, Dudenhausen J, Vetter K, Herrera E. Maternal lipids as strong determinants of fetal environment and growth in pregnancies with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 31: 1858–1863, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53a.Seahorse Bioscience. XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit User Manual XF24 Instructions. http://www.seahorsebio.com, 2010.

- 54.Simeoni U, Barker DJ. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: long-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 14: 119–124, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simpson P. Stimulation of hypertrophy of cultured neonatal rat heart cells through an alpha1-adrenergic receptor and induction of beating through an alpha1- and beta1-adrenergic receptor interaction. Evidence for independent regulation of growth and beating. Circ Res 56: 884–894, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Son GH, Kwon JY, Kim YH, Park YW. Maternal serum triglycerides as predictive factors for large-for-gestational age newborns in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89: 700–704, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song M, Mihara K, Chen Y, Scorrano L, Dorn GW 2nd. Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts. Cell Metab 21: 273–285, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev 85: 1093–1129, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ullmo S, Vial Y, Di Bernardo S, Roth-Kleiner M, Mivelaz Y, Sekarski N, Ruiz J, Meijboom EJ. Pathologic ventricular hypertrophy in the offspring of diabetic mothers: a retrospective study. Eur Heart J 28: 1319–1325, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Remmen H, Williams MD, Guo Z, Estlack L, Yang H, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Richardson A. Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1422–H1432, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vega RB, Horton JL, Kelly DP. Maintaining ancient organelles: mitochondrial biogenesis and maturation. Circ Res 116: 1820–1834, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallace DC. Bioenergetic origins of complexity and disease. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 76: 1–16, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber HS, Botti JJ, Baylen BG. Sequential longitudinal evaluation of cardiac growth and ventricular diastolic filling in fetuses of well controlled diabetic mothers. Pediatr Cardiol 15: 184–189, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber HS, Copel JA, Reece EA, Green J, Kleinman CS. Cardiac growth in fetuses of diabetic mothers with good metabolic control. J Pediatr 118: 103–107, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]