Abstract

Despite an obnoxious smell and toxicity at a high dose, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is emerging as a cardioprotective gasotransmitter. H2S mitigates pathological cardiac remodeling by regulating several cellular processes including fibrosis, hypertrophy, apoptosis, and inflammation. These encouraging findings in rodents led to initiation of a clinical trial using a H2S donor in heart failure patients. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms by which H2S mitigates cardiac remodeling are not completely understood. Empirical evidence suggest that H2S may regulate signaling pathways either by directly influencing a gene in the cascade or interacting with nitric oxide (another cardioprotective gasotransmitter) or both. Recent studies revealed that H2S may ameliorate cardiac dysfunction by up- or downregulating specific microRNAs. MicroRNAs are noncoding, conserved, regulatory RNAs that modulate gene expression mostly by translational inhibition and are emerging as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Few microRNAs also regulate H2S biosynthesis. The inter-regulation of microRNAs and H2S opens a new avenue for exploring the H2S-microRNA crosstalk in CVD. This review embodies regulatory mechanisms that maintain the physiological level of H2S, exogenous H2S donors used for increasing the tissue levels of H2S, H2S-mediated regulation of CVD, H2S-microRNAs crosstalk in relation to the pathophysiology of heart disease, clinical trials on H2S, and future perspectives for H2S as a therapeutic agent for heart failure.

Keywords: heart failure, inflammation, apoptosis, fibrosis, clinical trial, microRNAs

hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was first discovered in 1777 as a colorless gas with a strong “rotten egg” odor. It was thought to be a toxic substance found in sewer gas, swamp gas, and volcanic discharge. Since the discovery that H2S reacts to oxyhemoglobin similar to nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (17), a number of studies have been carried out to understand the biological functions of H2S. The obnoxious odor and toxicity discouraged the attention of researchers until it was revealed that H2S may have a possible role as an endogenous neuromodulator (1). Subsequently, a plethora of investigations were performed on potential roles of H2S in cardiovascular disease (CVD), which revealed that physiological levels of H2S have a pivotal role in maintaining cardiac function, and an exogenous supply of H2S has the potential to ameliorate heart failure in rodents. Empirical studies elucidated several potential mechanisms of H2S-mediated cardioprotection in different models of heart failure (21, 117, 123, 128, 150). However, regulation of H2S functions during heart failure is not completely understood. Recently, it was demonstrated that miRNA regulates endogenous H2S production (129, 148). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding, regulatory RNAs that modulate gene expression mostly by translational repression (10). Interestingly, H2S also regulates miRNA transcription. However, the crosstalk between H2S and miRNAs, and its impact on CVD, is poorly understood. Considering differential expression of miRNAs in CVD (27, 133), H2S-miRNAs crosstalk may have a crucial role in pathophysiology of heart failure. Therefore, H2S-miRNA crosstalk is important for understanding H2S-mediated cardioprotection. The goal of this review is to summarize the advancements made in H2S-mediated cardioprotection, highlight the inter-regulation of miRNAs and H2S, and emphasize potential future avenues of H2S-miRNA crosstalk in CVD, which will provide an impetus for developing H2S-based therapeutics for heart disease.

Regulation of H2S in vivo.

H2S is toxic at high levels; therefore, the production and degradation of H2S must be tightly regulated in our body to maintain its physiological level. Multiple synthesis and degradation pathways provide a complex interdependence, which could be crucial for restoring the physiological H2S level (Figs. 1 and 2). Understanding these pathways is indispensable for developing H2S-based therapeutics.

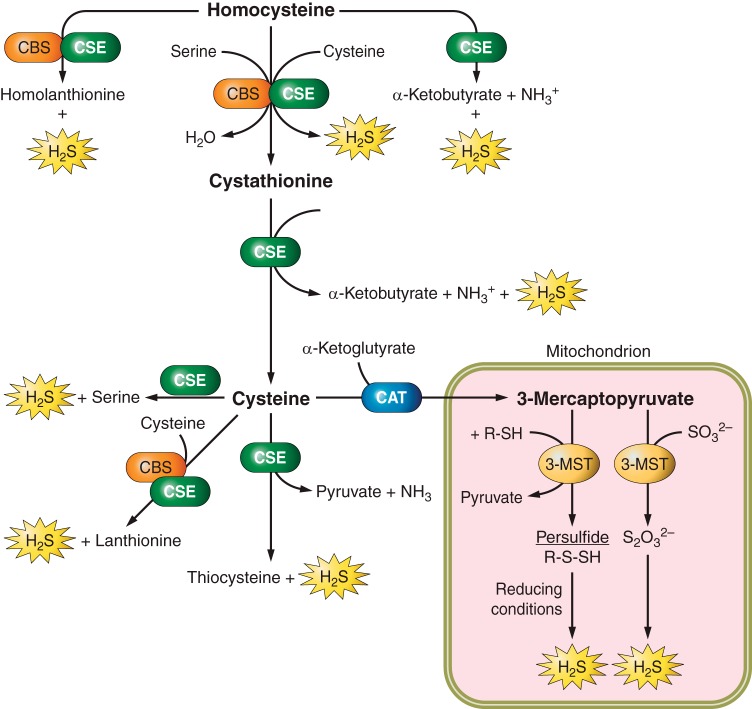

Fig. 1.

Biosynthesis of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). H2S production is catalyzed by cystathionine β synthase (CBS), cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE), and the coupling of cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (3-MST). CBS and CSE are involved in transsulfuration of homocysteine, which ultimately generates H2S. Both enzymes can also convert homocysteine into homolanthionine and H2S, and cysteine into lanthionine and H2S. CSE converts homocysteine, cystathionine, and cysteine into H2S and different by-products. 3-MST and CAT are mostly involved in converting 3-mercaptopyruvate into H2S in mitochondria. The main pathway of H2S generation is denoted by large print, whereas additional substrates and products by small print.

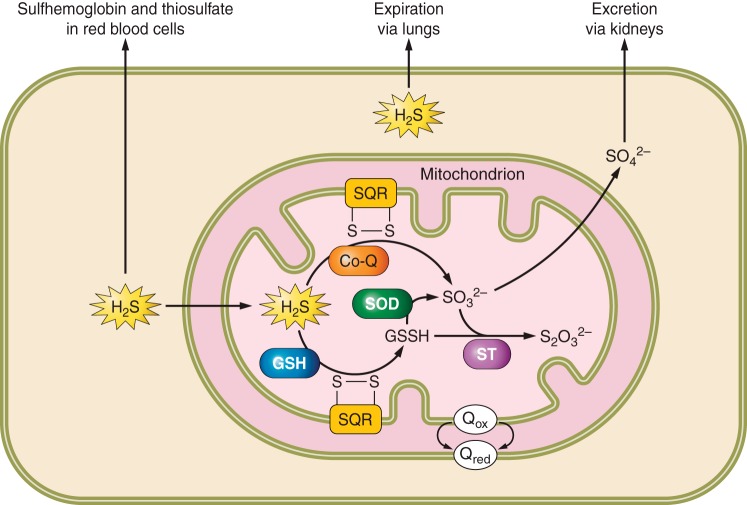

Fig. 2.

Cellular catabolism of H2S. In mitochondria, sulfide quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) oxidizes H2S to glutathione persulfide (GSSH) with GSH as the electron acceptor or directly to thiosulfate (SO32−) using co-enzyme Q (Co-Q) as the electron acceptor. The enzymes SOD, sulfur transferase (ST), and sulfite oxidase (SO) further oxidize GSSH to thiosulfate or sulfate, which is excreted via the kidneys. Expiration of H2S through exhaled air and scavenging by methemoglobin to sulfhemoglobin are alternative methods of H2S catabolism.

H2S biosynthesis.

H2S is predominately and primarily produced by three enzymatic pathways, which include cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and the coupling of cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (3-MST). CBS, CSE, and CAT are pyridoxal 5-phosphate-dependent enzymes. CBS catalyzes the β-replacement of thiosulfides such as homocysteine to cysteine, whereas CSE catalyzes the α- and γ-replacement of cysteine to H2S. CAT deaminates cysteine to mercaptopyruvate, which is followed by transulfuration catalyzed by the zinc-dependent enzyme 3-MST that results in biosynthesis of H2S. These pathways are elaborated in several excellent review articles (4, 8, 12, 20, 69, 75, 111, 113, 150) and summarized in Fig. 1. Although CBS and CSE are localized in the cytoplasm, 3-MST is localized mainly in mitochondria but has also been reported in the cytoplasm of vascular endothelial cells (106, 131). The expression levels of H2S generating enzymes are tissue specific (113). CSE is the most abundant H2S-generating enzyme in the cardiovascular system (83). Secondary sources of H2S include the air we breathe and generation of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract by bacterial flora (44, 52, 91, 92). The multiple pathways for H2S synthesis (Fig. 1) suggest an important role of H2S in cell signaling (53, 87, 99, 104).

Catabolism of H2S.

High levels of H2S are toxic. H2S levels are decreased in our body by several catabolic pathways. H2S is oxidized to thiosulfate and sulfate in the mitochondria of most mammalian tissues; however, the underlying molecular mechanisms and pathways are poorly understood (11, 69). Sulfide quinone oxidoreductase, which is located on the inner mitochondrial membrane, oxidizes H2S to glutathione persulfide using GSH as the sulfide acceptor (55, 90). Persulfide dioxygenase or rhodanese catalyze the oxidation of glutathione persulfide to thiosulfate and/or sulfide, which is further oxidized to sulfate by sulfite oxidase (90). Conversely, Jackson et al. (63) have shown sulfide quinone oxidoreductase catalyzes the oxidation of H2S directly to thiosulfate using co-enzyme Q as the electron acceptor and sulfite as the acceptor of sulfane sulfur. Although the intermediate pathways involved in the oxidation of H2S are not completely understood, sulfate is the primary by-product of sulfide catabolism, which may be excreted in the urine and feces (63, 69, 90). An additional pathway for excretion of H2S may include expiration by the lungs (61, 142). H2S may be scavenged by disulfide-containing molecules and red blood cells, where H2S binds to methemoglobin forming sulfhemoglobin, which is oxidized to thiosulfate (147). The multiple pathways for reducing H2S levels are presented in Fig. 2.

Physiological level of H2S.

Physiological levels of H2S range between 15 nM to 300 μM in vivo (62, 84, 85, 96, 110, 140, 153, 154). The wide range of H2S levels results from variable detection methods and the tissues analyzed [see review by Liu et al.(96)]. In in vivo conditions (37°C, pH ∼7.4), H2S is predicted to exist as 14% free H2S gas, 86% HS−, and trace levels of S2− (96, 153). Limitations to measuring H2S include 1) free H2S has a short half-life, ranging from 12 to 300 s in various species, and 2) detection methods may release bound sulfur from proteins, resulting in increased H2S concentrations (61, 96, 142, 153).

Exogenous sulfur donors.

Sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS) and sodium sulfide (Na2S) are the two most commonly used sources of H2S. They are water soluble and cost efficient. However, a limitation of NaHS and Na2S is that H2S is a volatile substance resulting in evaporation from drinking water. Furthermore, they give more of a bolus effect of H2S instead of a slow, steady release (19). Diallyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide (DATS) are organic sulfur compounds found in members of the Allium species (garlic, onions, chives, etc.) that act as H2S donors and have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and vasorelaxant properties (14, 94, 116, 132). Slow release sulfide donors such as GYY4137 (88), SG1002 (9, 78, 118), AP39 (138), and S-propargyl-cysteine (58, 149) are potential options for future H2S supplementation. In fact, SG1002 successfully completed Phase I clinical trial and is beginning Phase II clinical trial for increasing plasma H2S levels and mitigating heart failure (clinicaltrials.gov; No. NCT01989208 and No. NCT02278276) (118). Because of the volatile nature and short half-life of H2S, a continuous, low-level H2S release may provide an extended therapeutic potential than a single bolus using high levels as used in many NaHS and Na2S studies (19).

CVD and H2S.

CVD refers to any disease that leads to dysfunction in the heart and vasculature. Although many therapeutic options are available to treat CVD, the World Health Organization reports CVD remains the leading cause of death globally for both men and women, resulting in 17.5 million deaths in 2012 (155). Further research and better treatment options are necessary to reduce the incidence and burden of CVD. Evidence is mounting that H2S is important in reducing the symptoms associated with CVD. H2S reduces hypertension (2, 3), improves glucose uptake and metabolism (9, 89), protects against ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (70, 81, 141, 161), and decreases cardiac hypertrophy (9, 73, 93, 97). Further evidence shows that free H2S levels are reduced in patients with CVD (64, 79, 118), suggesting H2S supplementation may be a potential therapy for mitigating CVD. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms for H2S-mediated improvement in cardiac function, or amelioration of cardiac dysfunction in CVD, are not completely understood.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is mitigated by H2S.

Diabetes is among the top 10 causes of death in the United States (25a). One of the many complications of this debilitating disease is myocardial dysfunction (95, 152). Diabetes increases the risk of heart failure two- to fourfold as compared with age- and sex-matched nondiabetics (25, 100). Diabetes may effect both the heart and the vasculature or it may lead to left ventricular heart failure independent of coronary artery disease, a condition known as diabetic cardiomyopathy (26, 95). Diabetic cardiomyopathy is the end result of chronic exposure to a hyperglycemic environment. The pathophysiology includes cardiac dysfunction due to increased fibrosis and left ventricular hypertrophy (48). High glucose induces cardiovascular dysfunction by activating the PKC/diacylglycerol pathway, calcium dysregulation, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, and deregulating autophagy and apoptosis, which have been shown to be mitigated by H2S supplementation (9, 80, 89, 156, 164). Furthermore, plasma H2S levels are decreased in type 2 diabetic patients, high-fat diet–treated mice (type 2 diabetic patients), and streptozotocin-treated rats (9, 64, 66). The decrease in H2S levels in diabetics and the ability of exogenous H2S treatment to ameliorate pathological conditions induced by type 1 and type 2 diabetes suggest that H2S may be a potential novel treatment option for mitigating cardiomyopathy in diabetics.

H2S mitigates I/R injury.

Ischemia is the restriction of blood to tissues leading to a decrease in oxygen and glucose. Reperfusion injury occurs when blood flow returns to an area following ischemia and can further exacerbate cell damage (23, 146). I/R injury leads to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis (81). H2S reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) associated with I/R injury as well as decreases in cardiomyocyte apoptosis during ischemia (36, 56, 70, 81, 135, 141, 161) (Table 1). A major complication following I/R injury is the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias (37). H2S released by α-lipoic acid treatment activates the potassium ATP-sensitive channels (KATP channels) (37, 67) and decreases post I/R arrhythmias (37). It was further demonstrated that lower plasma H2S levels are associated with greater arrhythmia scores following I/R injury in Wistar rats (137). NaHS treatment inhibited the L-type Ca2+ channels, activated the KATP channels, and increased the action potential duration in these rats, all of which may result in decreased arrhythmias (137). During myocardial I/R injury, delivery of H2S at the time of reperfusion reduces infarct size and preserves left ventricular function. Moreover, overexpression of cardiac CSE mitigates myocardial I/R injury (39). H2S may protect the heart from I/R injury by increasing NO bioavailability and signaling (76). These findings suggest that H2S treatment may provide protective benefits following I/R injury by decreasing ROS and by mitigating cardiac arrhythmia.

Table 1.

Disease models and signaling mechanisms showing the cardiioprotective role of H2S in cardiovascular diseases

| Disease and Role of H2S | Pathways Regulated by H2S | Reference (No.) |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemia-reperfusion | ||

| Anti-apoptosis | ↓miR-1, ↑Bcl-2 | Kang et al. (70) |

| Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis | ↓CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells, ↑Bcl-2 | Zhang et al. (161) |

| Anti-inflammatory | ↑miR-21, ↓Inflammasome induction | Toldo et al. (141) |

| Anti-apoptosis | ↑Erk1/2 signaling BCl-xL, ↓Bad, GSK3β | Lambert et al. (81) |

| Anti-apoptosis | ↓Na+/H+ exchanger-1, pHi | Hu et al. (56) |

| Smoke-induced cardiomyopathy | ||

| Anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptosis | ↓p38, JNK, caspase 3, ↑Bcl-2 | Zhou et al. (163) |

| Antioxidant | ↑PI3K/AKT, Nrf2 | Zhou et al. (165) |

| Hyperglycemia | ||

| Glucose utilization | ↑GLUT1, GLUT4 | Liang et al. (89) |

| Antioxidant | ↓p38-MAPK, ERK1/2 | Xu et al. (156) |

| Anti-apoptosis | ↑p-AMPK, ↓p-Mammalian target of rapamycin | Wei et al. (151) |

| Anti-apoptosis Antioxidant | ↓p-JNK, p-cJun, NF-κB, ROS | Kuo et al. (80) |

| Antioxidant, anti-apoptosis, antifibrosis | ↓Estrogen receptor ROS, caspase-12, p-JNK, ↓Picrosirius red, ↑GLUT4 | Barr et al. (9) |

| Antioxidant, anti-apoptosis | ↓ROS, caspase-3, ↑PI3K/Akt, Nrf2 | Tsai et al. (143) |

| Hypertension | ||

| Vasorelaxation | ↑KATP channels, ↓Endothelin-1 | Sun et al. (136) Zhao et al. (162) |

| Vasodilation | ↑Nitric oxide | Eberhardt et al. (38) |

GLUT, glucose transporter; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

H2S is hypotensive.

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is defined as having a systolic blood pressure >140 mm mercury (mmHg) or a diastolic pressure >90 mmHg (107a, 109). Hypertension is a major medical concern affecting ∼30% of the United States population (109). Chronic high blood pressure creates excessive stress on the vasculature, leading to cardiac hypertrophy over time. An initial response to elevated blood pressure is activation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) (124, 167). However, chronic activation of the RAAS leads to heart failure (98, 167). H2S inhibits activation of the RAAS in Dahl rats fed with a high-salt diet, mitigating hypertension (59). Furthermore, abrogation of CSE (involved in H2S biosynthesis) decreases the level of H2S and induces hypertension in mice (158). H2S may decrease hypertension by opening voltage-dependent potassium channels, resulting in vasorelaxation and increasing vascular tone through multiple mechanisms (77, 125). H2S also induces vasorelaxation by opening KATP channels (136, 162) and increasing NO production (38). Contrary to vasorelaxation, Na2S and NaHS increased intracavernosal pressure by opening potassium channels in penile tissue (68), suggesting that H2S may cause vasoconstriction in other tissues. Therefore, the role of H2S for vasorelaxation or vasoconstriction depends on different conditions and tissues. Nevertheless, H2S has multiple mechanisms for reducing hypertension, suggesting a possible therapeutic role for H2S supplementation in treating hypertension.

Molecular mechanisms of H2S-mediated cardioprotection.

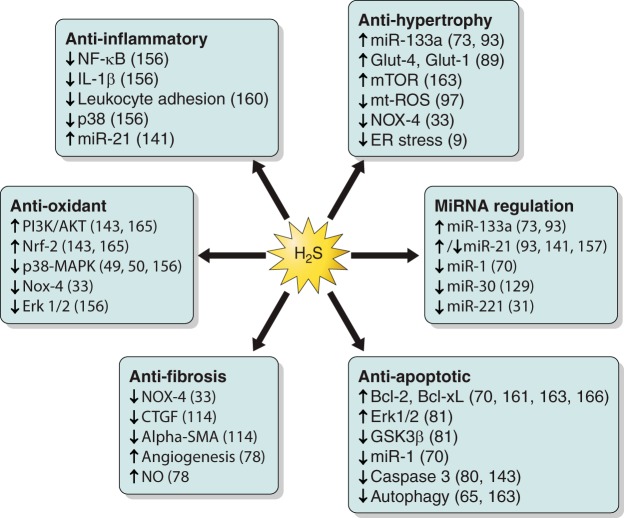

The cardioprotective effects of H2S are related to several important signaling and regulatory pathways including antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, antifibrotic, and anti-inflammatory regulation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cardioprotective effects of H2S. The pathways involved in H2S cardioprotection and the signaling mechanisms that have been shown to be induced (↑) or downregulated/blocked (↓) by H2S are indicated. The signaling molecules involved in each pathway and their references are included. CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; NOX, NADPH oxidase; SMA, smooth muscle actin; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

Antioxidant effects of H2S.

ROS refer to small reactive molecules such as superoxide (O2.−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl (OH.−), and hypochlorite (OCl.−), which react readily with other cellular molecules (29, 51). ROS are primarily generated as by-products of oxidative phosphorylation within the mitochondrial electron transport chain (29). Healthy mitochondria are vital for the overall health of the heart, because mitochondrial ATP generation via oxidative phosphorylation is essential for energy supply and for survival of cardiomyocytes. The generation and removal of ROS are tightly controlled during normal homeostasis but ROS generation increases during pathological conditions (18, 46). Superoxide radicals activate JNK, which is a stress-activated protein kinase. Induction of JNK leads to the activation of NF-κB, an important transcription factor of many cytokines, resulting in cardiac cell death (80). High glucose (33 mM) treatment increases expression of JNK, NF-κB, and the pro-apoptotic marker caspase-3, which resulted in increased apoptosis in cardiomyocytes (80).

In humans, red blood cells convert organic polysulfide (derived from garlic) into H2S, and it is facilitated by allyl substituents (14). DATS inhibits apoptosis by preventing caspase-3 activation, blunting phosphorylation of JNK and c-JUN, and inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB (80). H2S mitigates upregulation of ROS and prevents cell death associated with several disease states including hyperglycemia, hyper-homocysteinemia, smoke exposure, and I/R injury (49, 54, 144, 145, 156, 165).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor (Nrf2) is a primary regulator for the transcription of antioxidant response elements (72). NaHS (8 μMol·kg−1·day−1) increases Nrf2 levels in cardiomyocytes, resulting in decreased ROS levels in smoke-exposed rats (165). Furthermore, Nrf2 activation by DATS (10 μM) reduces ROS in high glucose–treated cardiomyocytes (143). In both cases, Nrf2 activation is the result of increased PI3K/Akt signaling induced by H2S supplementation (143, 165). H2S administration before myocardial ischemia increases the nuclear localization of Nrf2 and protects the ischemic heart from injury (21). These studies suggest that H2S regulates several signaling molecules to suppress oxidants in the heart (Fig. 3).

H2S promotes cell survival.

Apoptosis or “programmed cell death” can be a protective mechanism at physiological levels for removing damaged cells. However, in pathological conditions, apoptosis is deregulated, which causes increased cell death and tissue damage. As previously mentioned, ROS induces apoptosis and ROS can be mitigated by the antioxidant properties of H2S (see H2S mitigates I/R injury). In addition, H2S inhibits apoptosis by suppressing autophagy (65, 163). Autophagy is lysosome-mediated degradation and recycling of damaged and/or unnecessary cellular components (84). NaHS treatment suppresses cigarette smoke-induced upregulation of the autophagy inducers: Beclin-1, LC3II, and AMPK (163). H2S not only downregulates autophagy but it also induces PI3K and GSK3β. PI3K and GSK3β upregulate Nrf2 for cardioprotection (65, 143, 165). In an in vivo I/R model, NaHS (100 μM) increased phosphorylated mTOR complex 2, resulting in inactivation of cell death initiator Bim (Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death) for cell survival (166). Conversely, GYY4137 (100 μM) increases phosphorylated AMPK and decreases mTOR, which prevented high glucose-induced cardiac hypertrophy (151).

Members of the MAPK family, p38-MAPK and ERK1/2, are upregulated in response to cellular stress, leading to cardiomyocyte apoptosis (50, 156). p38-MAPK is induced in several disease conditions including hyperglycemia, I/R injury, and hypoxia (16, 49, 50, 134, 156). NaHS (400 μM) inhibits the activation of p38-MAPK in response to the antitumor drug doxorubicin, resulting in decreased apoptosis (50). Furthermore, pretreatment of H9c2 cardiomyocytes with NaHS (400 μM) reduces the cytotoxicity associated with hyperglycemia by inhibiting p38-MAPK and ERK1/2 (156).

These findings demonstrate that H2S provides cardioprotection by promoting cell survival via suppressing autophagy and inhibiting multiple proteins involved in apoptosis signaling (Fig. 3).

H2S mitigates pathological cardiac remodeling by inhibiting fibrosis and hypertrophy.

Cardiac fibrosis results from the proliferation of myofibroblasts, leading to increased extracellular matrix deposition in the muscle (34, 47). Excessive fibrosis decreases contractility and cardiac output and is often associated with cardiomyopathy. NaHS (100 μM) reduces fibroblast proliferation in human atrial fibroblast cells (130). Furthermore, it decreases NADPH oxidase 4, a stimulator of cardiac fibrosis (33), resulting in decreased levels of the profibrotic markers α-smooth muscle actin and connective tissue growth factor (114). Oral supplementation of SG1002 (20 mg·kg−1·day−1) reduces fibrosis in a transverse aortic constriction model as assessed by Masson Trichrome and Picrosirius Red staining (78). These findings suggest that H2S inhibits fibrosis (Fig. 3), and H2S supplementation has a therapeutic potential for decreasing cardiac fibrosis.

Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy occurs in response to chronic increases in pressure or stress. NaHS (100 μM) prevents phenylephrine- and isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy in cultured cardiomyocytes and in rat hearts. Furthermore, it downregulates mitochondrial ROS production, apoptosis, and improves glucose uptake through upregulation of the glucose transporters Glut-4 and Glut-1 (89, 97). The H2S donor SG1002 prevents cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction by reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress in high-fat diet–fed mice (9). Our laboratory has demonstrated that H2S treatment mitigates cardiac hypertrophy by upregulating miR-133a (73), an antihypertrophy (24, 41) and antifibrosis (28, 101) microRNA. To increase the levels of miR-133a, H2S activates myosin enhancer factor-2c (MEF2C), a transcription factor of miR-133a, by releasing MEF2C from MEF2C-HDAC1 complex (inactivated state) (73). These studies suggest that H2S plays a crucial role in inhibiting cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 3).

Anti-inflammatory role of H2S.

H2S treatments reduce inflammation by multiple mechanisms. NaHS and Na2S (100 μM/Kg body wt) suppress leukocyte adhesion by activating KATP channels in rats injected with aspirin, an inducer of leukocyte adhesion (160). Furthermore, inhibition of CSE reduces H2S biosynthesis and promotes leukocyte adhesion (160). H2S also regulates NF-κB, a transcription factor that is induced in stress, apoptosis, and inflammation signaling. NaHS (400 μM) suppresses high glucose-induced increases in NF-κB and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β in H9c2 cells (156). These studies along with the previously mentioned decrease in inflammation in response to I/R injury (subheading 4.2), suggest that H2S plays a pivotal role in mitigating inflammation (Fig. 3).

H2S regulates microRNAs to ameliorate heart failure.

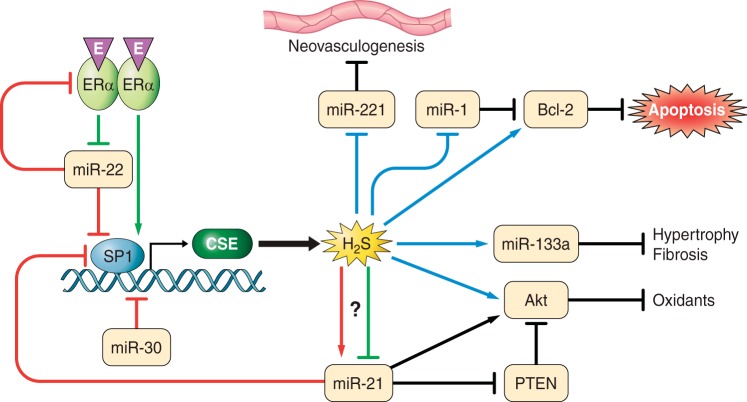

MicroRNAs are small (∼22 nt), noncoding RNAs that regulate mRNA and protein expression through mRNA degradation or translational inhibition (10). MiRNAs are rapidly emerging as therapeutic targets for CVD (22, 103, 108, 122, 126). H2S regulates miRNA expression (70, 73, 93); however, the interaction between H2S and miRNAs in CVD is poorly understood. Only a few publications document that miRNAs may regulate enzymes that control H2S biosynthesis and that H2S regulates miRNAs. H2S and miRNA inter-regulations are summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Interactions between H2S and microRNAs (miRNAs). MiR-21 and miR-22 inhibit specificity protein 1 [SP1, a transcription factor for cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE)], whereas miR-30 directly inhibits CSE, an enzyme responsible for H2S production, resulting in decreased H2S levels. Estrogen (E) activates estrogen receptor α (ERα), which binds to SP1 increasing CSE production and H2S. ERα also inhibits miR-22, which is an inhibitor of SP1. MiR-22 may also inhibit ERα, providing a secondary pathway for reducing CSE expression. H2S inhibits miRNAs including miR-221 (anti-neovasculogenic miRNA) and induces miR-133a (antihypertrophy and antifibrotic miRNA). H2S may inhibit and/or induce miR-21, which is a prohypertrophic miRNA but protects the heart during ischemia-reperfusion injury. H2S and miR-21 have crosstalk as miR-21 regulates H2S biosynthesis by inhibiting SP1 and CSE. H2S regulates Bcl-2 (anti-apoptosis) and Akt (anti-oxidant) either directly or via regulating miR-1 and miR-21, respectively. H2S may have synergistic effect on these pathways by direct regulation and indirect via miRNA regulation. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

MiRNAs regulate H2S biosynthesis.

Three miRNAs, miR-21, miR-22, and miR-30, have been shown to control H2S biosynthesis by regulating CSE gene expression. MiR-30 family members are upregulated concomitant with downregulation of CSE in the infarct and border zones following myocardial infarction (MI) in rat hearts (129). Luciferase reporter assay and in vivo silencing of miR-30 have confirmed that miR-30 targets CSE and inhibition of miR-30 can protect the MI heart by upregulating CSE (129). Estrogen (E2) also induces CSE expression through estrogen receptor α, which upregulates transcription of specificity protein-1 (SP1). SP1 directly binds to the promoter region of CSE to upregulate CSE transcription and H2S biosynthesis (148). Ovariectomized rats have increased levels of myocardial miR-22, which are normalized by E2 therapy. Furthermore, addition of miR-22 mimic inhibits estrogen receptor α and SP1 and downregulated CSE transcription (148). This suggests that miR-22 modulates H2S production in females. Therefore, E2 status and its regulation by miR-22 could be crucial in females with CVD. However, the role of anti-miR-22 treatment on cardiac function in males is unclear. It would be an interesting avenue to assess impact of anti-miR-22 treatment on cardiac CSE and H2S levels in males. These studies demonstrate that miRNAs play a crucial role in regulating H2S biosynthesis (Fig. 4).

H2S regulates miRNAs.

Not only do miRNAs regulate the biosynthesis of H2S, but H2S has also been demonstrated to regulate miRNAs. NaHS (100 μM) treatment upregulates cardioprotective miR-133a in primary cultures of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes to inhibit phenylepinephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (93). Furthermore, Na2S (30 μM) treatment increased miR-133a level to suppress hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in HL1 cardiomyocytes (73). These studies suggest that H2S may have an important role in miR-133a-mediated alleviation of cardiac dysfunction. Because diabetic human heart failure patients have reduced levels of miR-133a (107), the role of H2S in these hearts will be an interesting area for investigation. Measuring the cardiac levels of H2S and designing experiments with late-stage heart failure with H2S supplementation will provide insight on H2S-mediated cardioprotection in the failing heart.

MiR-1 is a bicistronic transcript with miR-133a and is upregulated in response to I/R stress (70). I/R-induced apoptosis is mediated through upregulation of miR-1 (70). MiR-1 is pro-apoptotic and directly suppresses anti-apoptotic proteins including Bcl-2 (70, 139), heat shock protein 60 (127), and heat shock protein 70 (159). The preconditioning of myocardial I/R with H2S decreases miR-1-mediated apoptosis (70). Dietary garlic has a cardioprotective effect, which is mediated through generation of H2S in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells (45, 74). DATS releases H2S (120) and downregulates anti-neovasculogenic miR-221 in a dose-dependent manner (31). Because miR-221 is upregulated in patients with coronary artery disease, garlic or H2S supplementation could be a potential therapeutic strategy for reducing the levels of miR-221 to mitigate the effects of coronary artery disease. The above studies show that H2S is involved in regulating miRNAs (Fig. 4).

H2S-miRNA crosstalk.

The interaction of H2S with miRNA is recently uncovered and is an emerging area of investigation. An example of H2S-miRNA crosstalk is that H2S downregulates miR-21 to mitigate phenylephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (93), and miR-21 targets SP1 to decrease CSE transcription and H2S production (157). Furthermore, increased miR-21 levels and decreased CSE levels are found in placental tissue from high risk pregnancy as compared with normal pregnancy, suggesting that low H2S level may induce miR-21 and contribute to increased pregnancy complications (32). Perfusion of placental extracts with NaHS improves vasodilation; however, it is unclear whether NaHS perfusion alters miR-21 levels. Although these studies demonstrate that miR-21 may have a negative impact as it reduces H2S levels, several studies show the beneficial effects of miR-21 in cardiac cells, including inhibiting apoptosis (30, 121), protecting cardiomyocytes from H2O2 (30) and I/R damage by suppressing phosphatase and tensin homolog (158). Na2S (10 μM) induces miR-21 in primary cardiomyocytes and heart tissue. However, it had no effect on miR-21 knockout mice even though it reduces infarct size and attenuates inflammation in response to I/R injury (141). These findings suggest that H2S-miRNA crosstalk may vary in a context-dependent manner and may have different roles in different disease conditions (Fig. 4). Therefore, more research using different models of heart failure is required to elucidate H2S-miRNA crosstalk in CVD.

Potential new areas for investigation on H2S-miRNA crosstalk.

H2S and miRNA are relatively new research areas in CVD, and there is a lot of potential inter-regulation between H2S and miRNAs. Although miR-21, miR-22, and miR-30 are demonstrated to modulate CSE gene expression (Fig. 4), no miRNAs are reported that control CBS or 3-MST expression, suggesting a gap in knowledge. There are ample opportunities for investigations on potential miRNAs regulating genes involved in H2S biosynthesis. Furthermore, many miRNAs have been shown to regulate CVD, yet the effect of H2S on only a few miRNAs is reported. This provides an avenue to explore the effect of H2S on crucial miRNAs involved in the regulation of heart failure. For example, miR-24 is upregulated following MI, and it directly inhibits endothelial NO synthase (102). H2S provides cardioprotective effects through upregulating endothelial NO synthase (76, 78), yet it is unclear whether H2S suppresses miR-24. Interestingly, H2S may regulate anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 by either directly upregulating it or by suppressing miR-1, an inhibitor of Bcl-2. Similarly, H2S may regulate Akt directly or by regulating miR-21 (Fig. 4). Future studies in these areas will elucidate the complex regulatory network of H2S-miRNA crosstalk in CVD.

H2S involved in clinical trials.

Clinical trials with SG1002 will be exciting to follow and to see if the increase in H2S levels translate into significant benefits in treating or preventing heart failure. Results from the initial clinical trial with SG1002 have recently been reported, demonstrating that SG1002 increases H2S and nitrite levels with few, mild adverse events (118). Furthermore, sulfur donors are being attached to current drug treatments, such as naproxen, improving their anti-inflammatory effectiveness and decreasing gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects (13, 19, 35, 42, 105). H2S has beneficial effects in other organs including neurons, kidney, pancreas, and gastrointestinal and in arthritis (15, 43). This suggests organ-specific delivery systems for H2S may need to be developed to localize therapeutic effects. As H2S levels are decreased in diabetics and MI patients, H2S may be a useful biomarker for CVD. A clinical trial has been recently completed where H2S was measured as a biomarker for peripheral artery disease (clinicaltrials.gov; No. NCT01407172). Another clinical trial is recruiting to measure H2S levels in women with CVD (clinicaltrials.gov; No. NCT02180074).

Future directions.

Many mechanisms of H2S signaling have been elucidated; however, there are still a lot of unknowns on how H2S levels influence cardiovascular health. As detection methods improve for more accurate measurements of H2S and for measuring real-time H2S generation, we will get a better understanding of how cells maintain H2S balance. H2S mitigates many pathologies associated with CVD, and the therapeutic benefits of H2S are currently being explored in other organ systems. For example, H2S levels are decreased in the neurodegenerative disorders Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases (40, 57), and H2S treatments have mitigated renal dysfunction by many of the same pathways as involved in cardiomyopathy (115).

The inter-regulation of H2S and miRNAs suggests H2S may have a greater role in maintaining cellular homeostasis than previously thought. For example, H2S may directly regulate Bcl-2 and Akt, or it may control these genes by regulating miR-1 and miR-21, respectively. Besides, H2S may have a synergistic effect using direct regulation and indirect regulation via miRNAs (Fig. 4). More mechanistic studies are required to elucidate the growing role of H2S on miRNA regulation and its potential to regulate epigenetic modifications. MiRNAs regulate pathological remodeling in the heart and may be important treatment options for mitigating CVD (103). Two miRNAs or anti-miRNA therapies are undergoing clinical trial for non-CVD including anti-miR-122 (Miravirsen) for treatment of Hepatitis C (clinicaltrials.gov; No. NCT01200420) (112) and a miR-34 mimic for the treatment of primary liver cancer and other solid tumors (clinicaltrials.gov; No. NCT01829971). The role of these miRNAs on H2S or role of H2S in the regulation of miRNAs is awaiting.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), RNAs with >200 nucleotides, are emerging as regulators of genes, miRNAs, and proteins involved in CVD (5, 60, 71, 119). Transcriptome analyses show distinct patterns of lncRNA profiles in heart failure conditions (82, 86), yet lncRNA-mediated regulation of H2S or any effect of H2S on lncRNAs is an open area for investigation. Future studies exploring the crosstalk among lncRNAs, miRNAs, and H2S may elucidate novel regulatory mechanisms for CVD and provide new strategies for treatment of heart failure.

GRANTS

Financial support is from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-113281 and HL-116205 (to P. K. Mishra).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: P.K.M. conception and design of review; B.T.H. prepared figures; B.T.H. and P.K.M. drafted manuscript; B.T.H. and P.K.M. edited and revised manuscript; B.T.H. and P.K.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci 16: 1066–1071, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad A, Sattar MA, Rathore HA, Khan SA, Lazhari MI, Afzal S, Hashmi F, Abdullah NA, Johns EJ. A critical review of pharmacological significance of hydrogen sulfide in hypertension. Indian J Pharmacol 47: 243–247, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad FU, Sattar MA, Rathore HA, Abdullah MH, Tan S, Abdullah NA, Johns EJ. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) reduces blood pressure and prevents the progression of diabetic nephropathy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Ren Fail 34: 203–210, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitken SM, Lodha PH, Morneau DJ. The enzymes of the transsulfuration pathways: active-site characterizations. Biochim Biophys Acta 1814: 1511–1517, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archer K, Broskova Z, Bayoumi AS, Teoh JP, Davila A, Tang Y, Su H, Kim IM. Long non-coding RNAs as master regulators in cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci 16: 23651–23667, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee R, Chiku T, Kabil O, Libiad M, Motl N, Yadav PK. Assay methods for H2S biogenesis and catabolism enzymes. Methods Enzymol 554: 189–200, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr LA, Shimizu Y, Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates high fat diet-induced cardiac dysfunction via the suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nitric Oxide 46: 145–156, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartholomew TC, Powell GM, Dodgson KS, Curtis CG. Oxidation of sodium sulphide by rat liver, lungs and kidney. Biochem Pharmacol 29: 2431–2437, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beard RS Jr, Bearden SE. Vascular complications of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: future directions for homocysteine-to-hydrogen sulfide research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H13–H26, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltowski J. Hydrogen sulfide in pharmacology and medicine—An update. Pharmacol Rep 67: 647–658, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM, Doeller JE, Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17977–17982, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia M. H2S and inflammation: an overview. Handb Exp Pharmacol 230: 165–180, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogoyevitch MA, Gillespie-Brown J, Ketterman AJ, Fuller SJ, Ben-Levy R, Ashworth A, Marshall CJ, Sugden PH. Stimulation of the stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase subfamilies in perfused heart. p38/RK mitogen-activated protein kinases and c-Jun N-terminal kinases are activated by ischemia/reperfusion. Circ Res 79: 162–173, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruere MA. Direct action of hydrogen sulphide, hydrogen selenide, and hydrogen telluride on haemoglobin. J Anat Physiol 26: 62–75, 1891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgoyne JR, Mongue-Din H, Eaton P, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ Res 111: 1091–1106, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caliendo G, Cirino G, Santagada V, Wallace JL. Synthesis and biological effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S): development of H2S-releasing drugs as pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem 53: 6275–6286, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvert JW, Coetzee WA, Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide—mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1203–1217, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res 105: 365–374, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calway T, Kim GH. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of MicroRNAs for cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 20: 131–143, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J Pathol 190: 255–266, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 13: 613–618, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes Report Card 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK. Predictors and prevention of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 6: 151–160, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK. Differential expression of dicer, miRNAs, and inflammatory markers in diabetic Ins2+/− Akita hearts. Cell Biochem Biophys 68: 25–35, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S, Puthanveetil P, Feng B, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW, Chakrabarti S. Cardiac miR-133a overexpression prevents early cardiac fibrosis in diabetes. J Cell Mol Med 18: 415–421, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YR, Zweier JL. Cardiac mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res 114: 524–537, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, Zhu P, Yang J, Liu X, Dong S, Wang X, Chun B, Zhuang J, Zhang C. Ischaemic preconditioning-regulated miR-21 protects heart against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via anti-apoptosis through its target PDCD4. Cardiovasc Res 87: 431–439, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiang EP, Chiu SC, Pai MH, Wang YC, Wang FY, Kuo YH, Tang FY. Organosulfur garlic compounds induce neovasculogenesis in human endothelial progenitor cells through a modulation of MicroRNA 221 and the PI3-K/Akt signaling pathways. J Agric Food Chem 61: 4839–4849, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cindrova-Davies T, Herrera EA, Niu Y, Kingdom J, Giussani DA, Burton GJ. Reduced cystathionine gamma-lyase and increased miR-21 expression are associated with increased vascular resistance in growth-restricted pregnancies: hydrogen sulfide as a placental vasodilator. Am J Pathol 182: 1448–1458, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cucoranu I, Clempus R, Dikalova A, Phelan PJ, Ariyan S, Dikalov S, Sorescu D. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res 97: 900–907, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis J, Molkentin JD. Myofibroblasts: trust your heart and let fate decide. J Mol Cell Cardiol 70: 9–18, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dief AE, Mostafa DK, Sharara GM, Zeitoun TH. Hydrogen sulfide releasing naproxen offers better anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effect relative to naproxen in a rat model of zymosan induced arthritis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 19: 1537–1546, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dongo E, Hornyak I, Benko Z, Kiss L. The cardioprotective potential of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (review). Acta Physiol Hung 98: 369–381, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dudek M, Knutelska J, Bednarski M, Nowinski L, Zygmunt M, Bilska-Wilkosz A, Iciek M, Otto M, Zytka I, Sapa J, Wlodek L, Filipek B. Alpha lipoic acid protects the heart against myocardial post ischemia-reperfusion arrhythmias via KATP channel activation in isolated rat hearts. Pharmacol Rep 66: 499–504, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberhardt M, Dux M, Namer B, Miljkovic J, Cordasic N, Will C, Kichko TI, de la Roche J, Fischer M, Suarez SA, Bikiel D, Dorsch K, Leffler A, Babes A, Lampert A, Lennerz JK, Jacobi J, Marti MA, Doctorovich F, Hogestatt ED, Zygmunt PM, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I, Messlinger K, Reeh P, Filipovic MR. H2S and NO cooperatively regulate vascular tone by activating a neuroendocrine HNO-TRPA1-CGRP signaling pathway. Nat Commun 5: 4381, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, Szabo C, Kimura H, Chow CW, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15560–15565, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eto K, Asada T, Arima K, Makifuchi T, Kimura H. Brain hydrogen sulfide is severely decreased in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293: 1485–1488, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng B, Chen S, George B, Feng Q, Chakrabarti S. miR133a regulates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 26: 40–49, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiorucci S, Santucci L. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapies: focus on H2S releasing NSAIDs. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 10: 133–140, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gemici B, Elsheikh W, Feitosa KB, Costa SK, Muscara MN, Wallace JL. H2S-releasing drugs: anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective and chemopreventative potential. Nitric Oxide 46: 25–31, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geng Y, Li E, Mu Q, Zhang Y, Wei X, Li H, Cheng L, Zhang B. Hydrogen sulfide inhalation decreases early blood-brain barrier permeability and brain edema induced by cardiac arrest and resuscitation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 494–500, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ginter E, Simko V. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) and cardiovascular diseases. Bratisl Lek Listy 111: 452–456, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giordano FJ. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest 115: 500–508, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldsmith EC, Bradshaw AD, Zile MR, Spinale FG. Myocardial fibroblast-matrix interactions and potential therapeutic targets. J Mol Cell Cardiol 70: 92–99, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gray S, Kim JK. New insights into insulin resistance in the diabetic heart. Trends Endocrinol Metab 22: 394–403, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo R, Lin J, Xu W, Shen N, Mo L, Zhang C, Feng J. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibition of the p38 MAPK pathway in H9c2 cells. Int J Mol Med 31: 644–650, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo R, Wu K, Chen J, Mo L, Hua X, Zheng D, Chen P, Chen G, Xu W, Feng J. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects against doxorubicin-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity by inhibiting p38MAPK/NFkappaB pathway in H9c2 cardiac cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 32: 1668–1680, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hafstad AD, Nabeebaccus AA, Shah AM. Novel aspects of ROS signalling in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 108: 359, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han ZH, Jiang YI, Duan YY, Wang XY, Huang Y, Fang TZ. Protective effects of hydrogen sulfide inhalation on oxidative stress in rats with cotton smoke inhalation-induced lung injury. Exp Ther Med 10: 164–168, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hancock JT, Whiteman M. Hydrogen sulfide and cell signaling: team player or referee? Plant Physiol Biochem 78: 37–42, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He X, Kan H, Cai L, Ma Q. Nrf2 is critical in defense against high glucose-induced oxidative damage in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 47–58, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hildebrandt TM, Grieshaber MK. Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. FEBS J 275: 3352–3361, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu LF, Li Y, Neo KL, Yong QC, Lee SW, Tan BK, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide regulates Na+/H+ exchanger activity via stimulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and protein kinase G pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339: 726–735, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu LF, Lu M, Tiong CX, Dawe GS, Hu G, Bian JS. Neuroprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide on Parkinson's disease rat models. Aging Cell 9: 135–146, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang C, Kan J, Liu X, Ma F, Tran BH, Zou Y, Wang S, Zhu YZ. Cardioprotective effects of a novel hydrogen sulfide agent-controlled release formulation of S-propargyl-cysteine on heart failure rats and molecular mechanisms. PLoS One 8: e69205, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang P, Chen S, Wang Y, Liu J, Yao Q, Huang Y, Li H, Zhu M, Wang S, Li L, Tang C, Tao Y, Yang G, Du J, Jin H. Down-regulated CBS/H2S pathway is involved in high-salt-induced hypertension in Dahl rats. Nitric Oxide 46: 192–203, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iaconetti C, Gareri C, Polimeni A, Indolfi C. Non-coding RNAs: the “dark matter” of cardiovascular pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci 14: 19987–20018, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Insko MA, Deckwerth TL, Hill P, Toombs CF, Szabo C. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in rats exposed to intravenous sodium sulphide. Br J Pharmacol 157: 944–951, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishigami M, Hiraki K, Umemura K, Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Kimura H. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 205–214, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson MR, Melideo SL, Jorns MS. Human sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase catalyzes the first step in hydrogen sulfide metabolism and produces a sulfane sulfur metabolite. Biochemistry 51: 6804–6815, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jain SK, Bull R, Rains JL, Bass PF, Levine SN, Reddy S, McVie R, Bocchini JA. Low levels of hydrogen sulfide in the blood of diabetes patients and streptozotocin-treated rats causes vascular inflammation? Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1333–1337, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang H, Xiao J, Kang B, Zhu X, Xin N, Wang Z. PI3K/SGK1/GSK3beta signaling pathway is involved in inhibition of autophagy in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation by hydrogen sulfide. Exp Cell Res S0014-4827(15)30035-5, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin S, Pu SX, Hou CL, Ma FF, Li N, Li XH, Tan B, Tao BB, Wang MJ, Zhu YC. Cardiac H2S generation is reduced in ageing diabetic mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015: 758358, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johansen D, Ytrehus K, Baxter GF. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) protects against regional myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury—evidence for a role of K ATP channels. Basic Res Cardiol 101: 53–60, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jupiter RC, Yoo D, Pankey EA, Reddy VV, Edward JA, Polhemus DJ, Peak TC, Katakam P, Kadowitz PJ. Analysis of erectile responses to H2S donors in the anesthetized rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H835–H843, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kabil O, Banerjee R. Enzymology of H2S biogenesis, decay and signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 770–782, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang B, Hong J, Xiao J, Zhu X, Ni X, Zhang Y, He B, Wang Z. Involvement of miR-1 in the protective effect of hydrogen sulfide against cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Mol Biol Rep 41: 6845–6853, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT, Stadler PF, Hertel J, Hackermuller J, Hofacker IL, Bell I, Cheung E, Drenkow J, Dumais E, Patel S, Helt G, Ganesh M, Ghosh S, Piccolboni A, Sementchenko V, Tammana H, Gingeras TR. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 316: 1484–1488, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47: 89–116, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kesherwani V, Nandi SS, Sharawat SK, Shahshahan HR, Mishra PK. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates homocysteine-mediated pathological remodeling by inducing miR-133a in cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biochem 404: 241–250, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khatua TN, Adela R, Banerjee SK. Garlic and cardioprotection: insights into the molecular mechanisms. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 91: 448–458, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kimura H. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides. Handb Exp Pharmacol 230: 61–81, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Kondo K, Nicholson CK, Bradley JM, Islam KN, Calvert JW, Tao YX, Dugas TR, Kelley EE, Elrod JW, Huang PL, Wang R, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 3182–3187, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kohn C, Dubrovska G, Huang Y, Gollasch M. Hydrogen sulfide: potent regulator of vascular tone and stimulator of angiogenesis. Int J Biomed Sci 8: 81–86, 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kondo K, Bhushan S, King AL, Prabhu SD, Hamid T, Koenig S, Murohara T, Predmore BL, Gojon G Sr, Gojon G Jr, Wang R, Karusula N, Nicholson CK, Calvert JW, Lefer DJ. H2S protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 127: 1116–1127, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kovacic D, Glavnik N, Marinsek M, Zagozen P, Rovan K, Goslar T, Mars T, Podbregar M. Total plasma sulfide in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail 18: 541–548, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuo WW, Wang WJ, Tsai CY, Way CL, Hsu HH, Chen LM. Diallyl trisufide (DATS) suppresses high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by inhibiting JNK/NFkappaB signaling via attenuating ROS generation. Int J Cardiol 168: 270–280, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, Amin H, Amin S, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide provides cardioprotection against myocardial/ischemia reperfusion injury in the diabetic state through the activation of the RISK pathway. Med Gas Res 4: 20, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee JH, Gao C, Peng G, Greer C, Ren S, Wang Y, Xiao X. Analysis of transcriptome complexity through RNA sequencing in normal and failing murine hearts. Circ Res 109: 1332–1341, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH, Wang R. Carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide: gaseous messengers in cerebrovascular circulation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100: 1065–1076, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132: 27–42, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levitt MD, Abdel-Rehim MS, Furne J. Free and acid-labile hydrogen sulfide concentrations in mouse tissues: anomalously high free hydrogen sulfide in aortic tissue. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 373–378, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li D, Chen G, Yang J, Fan X, Gong Y, Xu G, Cui Q, Geng B. Transcriptome analysis reveals distinct patterns of long noncoding RNAs in heart and plasma of mice with heart failure. PLoS One 8: e77938, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li L, Rose P, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide and cell signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 51: 169–187, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee SW, Zhao Y, Baskar R, Tan CH, Moore PK. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation 117: 2351–2360, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang M, Jin S, Wu D, Wang M, Zhu Y. Hydrogen sulfide improves glucose metabolism and prevents hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Nitric Oxide 46: 114–122, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Libiad M, Yadav PK, Vitvitsky V, Martinov M, Banerjee R. Organization of the human mitochondrial hydrogen sulfide oxidation pathway. J Biol Chem 289: 30901–30910, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Linden DR. Hydrogen sulfide signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 818–830, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Linden DR, Levitt MD, Farrugia G, Szurszewski JH. Endogenous production of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract: still in search of a physiologic function. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1135–1146, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu J, Hao DD, Zhang JS, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulphide inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by up-regulating miR-133a. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 413: 342–347, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu LL, Yan L, Chen YH, Zeng GH, Zhou Y, Chen HP, Peng WJ, He M, Huang QR. A role for diallyl trisulfide in mitochondrial antioxidative stress contributes to its protective effects against vascular endothelial impairment. Eur J Pharmacol 725: 23–31, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu Q, Wang S, Cai L. Diabetic cardiomyopathy and its mechanisms: role of oxidative stress and damage. J Diabetes Investig 5: 623–634, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu YH, Lu M, Hu LF, Wong PT, Webb GD, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide in the mammalian cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 141–185, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu F, Xing J, Zhang X, Dong S, Zhao Y, Wang L, Li H, Yang F, Xu C, Zhang W. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis from cardiac hypertrophy induced by isoproterenol. Mol Cell Biochem 381: 41–50, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lymperopoulos A. Physiology and pharmacology of the cardiovascular adrenergic system. Front Physiol 4: 240, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 99.Mancardi D, Penna C, Merlino A, Del SP, Wink DA, Pagliaro P. Physiological and pharmacological features of the novel gasotransmitter: hydrogen sulfide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 864–872, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mathew V, Gersh BJ, Williams BA, Laskey WK, Willerson JT, Tilbury RT, Davis BR, Holmes DR Jr. Outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the current era: a report from the Prevention of REStenosis with Tranilast and its Outcomes (PRESTO) trial. Circulation 109: 476–480, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matkovich SJ, Wang W, Tu Y, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn LE, Condorelli G, Diwan A, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW. MicroRNA-133a protects against myocardial fibrosis and modulates electrical repolarization without affecting hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded adult hearts. Circ Res 106: 166–175, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meloni M, Marchetti M, Garner K, Littlejohns B, Sala-Newby G, Xenophontos N, Floris I, Suleiman MS, Madeddu P, Caporali A, Emanueli C. Local inhibition of microRNA-24 improves reparative angiogenesis and left ventricle remodeling and function in mice with myocardial infarction. Mol Ther 21: 1390–1402, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Tyagi SC. MicroRNAs as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Mol Med 13: 778–789, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Modis K, Wolanska K, Vozdek R. Hydrogen sulfide in cell signaling, signal transduction, cellular bioenergetics and physiology in C. elegans. Gen Physiol Biophys 32: 1–22, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Motta JP, Flannigan KL, Agbor TA, Beatty JK, Blackler RW, Workentine ML, Da Silva GJ, Wang R, Buret AG, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide protects from colitis and restores intestinal microbiota biofilm and mucus production. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21: 1006–1017, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nagahara N, Ito T, Kitamura H, Nishino T. Tissue and subcellular distribution of mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the rat: confocal laser fluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic studies combined with biochemical analysis. Histochem Cell Biol 110: 243–250, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nandi SS, Duryee MJ, Shahshahan HR, Thiele GM, Anderson DR, Mishra PK. Induction of autophagy markers is associated with attenuation of miR-133a in diabetic heart failure patients undergoing mechanical unloading. Am J Transl Res 7: 683–696, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107a.National High Blood Pressure Education Program. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nouraee N, Mowla SJ. miRNA therapeutics in cardiovascular diseases: promises and problems. Front Genet 6: 232, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 1–8, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Togawa T, Tanabe S. Determination of bound sulfur in serum by gas dialysis/high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 215: 73–81, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Olas B. Hydrogen sulfide in signaling pathways. Clin Chim Acta 439: 212–218, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ottosen S, Parsley TB, Yang L, Zeh K, van Doorn LJ, van d V, Raney AK, Hodges MR, Patick AK. In vitro antiviral activity and preclinical and clinical resistance profile of miravirsen, a novel anti-hepatitis C virus therapeutic targeting the human factor miR-122. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59: 599–608, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pan LL, Liu XH, Gong QH, Yang HB, Zhu YZ. Role of cystathionine gamma-lyase/hydrogen sulfide pathway in cardiovascular disease: a novel therapeutic strategy? Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 106–118, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pan LL, Liu XH, Shen YQ, Wang NZ, Xu J, Wu D, Xiong QH, Deng HY, Huang GY, Zhu YZ. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase 4-related signaling by sodium hydrosulfide attenuates myocardial fibrotic response. Int J Cardiol 168: 3770–3778, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pan WJ, Fan WJ, Zhang C, Han D, Qu SL, Jiang ZS. H2S, a novel therapeutic target in renal-associated diseases? Clin Chim Acta 438: 112–118, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Polhemus DJ, Kondo K, Bhushan S, Bir SC, Kevil CG, Murohara T, Lefer DJ, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cardiac dysfunction after heart failure via induction of angiogenesis. Circ Heart Fail 6: 1077–1086, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Polhemus DJ, Lefer DJ. Emergence of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous gaseous signaling molecule in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 114: 730–737, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Polhemus DJ, Li Z, Pattillo CB, Gojon G Sr, Gojon G Jr, Giordano T, Krum H. A novel hydrogen sulfide prodrug, SG1002, promotes hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide bioavailability in heart failure patients. Cardiovasc Ther 33: 216–226, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 136: 629–641, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Predmore BL, Kondo K, Bhushan S, Zlatopolsky MA, King AL, Aragon JP, Grinsfelder DB, Condit ME, Lefer DJ. The polysulfide diallyl trisulfide protects the ischemic myocardium by preservation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and increasing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2410–H2418, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Qin Y, Yu Y, Dong H, Bian X, Guo X, Dong S. MicroRNA 21 inhibits left ventricular remodeling in the early phase of rat model with ischemia-reperfusion injury by suppressing cell apoptosis. Int J Med Sci 9: 413–423, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Romaine SP, Tomaszewski M, Condorelli G, Samani NJ. MicroRNAs in cardiovascular disease: an introduction for clinicians. Heart 101: 921–928, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Salloum FN. Hydrogen sulfide and cardioprotection—mechanistic insights and clinical translatability. Pharmacol Ther 152: 11–17, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sayer G, Bhat G. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and heart failure. Cardiol Clin 32: 21–32, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schleifenbaum J, Kohn C, Voblova N, Dubrovska G, Zavarirskaya O, Gloe T, Crean CS, Luft FC, Huang Y, Schubert R, Gollasch M. Systemic peripheral artery relaxation by KCNQ channel openers and hydrogen sulfide. J Hypertens 28: 1875–1882, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schulte C, Zeller T. microRNA-based diagnostics and therapy in cardiovascular disease—summing up the facts. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 5: 17–36, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shan ZX, Lin QX, Deng CY, Zhu JN, Mai LP, Liu JL, Fu YH, Liu XY, Li YX, Zhang YY, Lin SG, Yu XY. miR-1/miR-206 regulate Hsp60 expression contributing to glucose-mediated apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett 584: 3592–3600, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shen Y, Shen Z, Luo S, Guo W, Zhu YZ. The cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide in heart diseases: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015: 925167, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Shen Y, Shen Z, Miao L, Xin X, Lin S, Zhu Y, Guo W, Zhu YZ. miRNA-30 family inhibition protects against cardiac ischemic injury by regulating cystathionine-gamma-lyase expression. Antioxid Redox Signal 22: 224–240, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sheng J, Shim W, Wei H, Lim SY, Liew R, Lim TS, Ong BH, Chua YL, Wong P. Hydrogen sulphide suppresses human atrial fibroblast proliferation and transformation to myofibroblasts. J Cell Mol Med 17: 1345–1354, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem 146: 623–626, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Shin IS, Hong J, Jeon CM, Shin NR, Kwon OK, Kim HS, Kim JC, Oh SR, Ahn KS. Diallyl-disulfide, an organosulfur compound of garlic, attenuates airway inflammation via activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway and NF-kappaB suppression. Food Chem Toxicol 62: 506–513, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Song MA, Paradis AN, Gay MS, Shin J, Zhang L. Differential expression of microRNAs in ischemic heart disease. Drug Discov Today 20: 223–235, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sugden PH, Clerk A. “Stress-responsive” mitogen-activated protein kinases (c-Jun N-terminal kinases and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in the myocardium. Circ Res 83: 345–352, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sun WH, Liu F, Chen Y, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulfide decreases the levels of ROS by inhibiting mitochondrial complex IV and increasing SOD activities in cardiomyocytes under ischemia/reperfusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 421: 164–169, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sun Y, Huang Y, Zhang R, Chen Q, Chen J, Zong Y, Liu J, Feng S, Liu AD, Holmberg L, Liu D, Tang C, Du J, Jin H. Hydrogen sulfide upregulates KATP channel expression in vascular smooth muscle cells of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Mol Med (Berl) 93: 439–455, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sun YG, Wang XY, Chen X, Shen CX, Li YG. Hydrogen sulfide improves cardiomyocytes electrical remodeling post ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8: 474–481, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Szczesny B, Modis K, Yanagi K, Coletta C, Le TS, Perry A, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Szabo C. AP39, a novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, stimulates cellular bioenergetics, exerts cytoprotective effects and protects against the loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells in vitro. Nitric Oxide 41: 120–130, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tang Y, Zheng J, Sun Y, Wu Z, Liu Z, Huang G. MicroRNA-1 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting Bcl-2. Int Heart J 50: 377–387, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Togawa T, Ogawa M, Nawata M, Ogasawara Y, Kawanabe K, Tanabe S. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of bound sulfide and sulfite and thiosulfate at their low levels in human serum by pre-column fluorescence derivatization with monobromobimane. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 40: 3000–3004, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Toldo S, Das A, Mezzaroma E, Chau VQ, Marchetti C, Durrant D, Samidurai A, Van Tassell BW, Yin C, Ockaili RA, Vigneshwar N, Mukhopadhyay ND, Kukreja RC, Abbate A, Salloum FN. Induction of microRNA-21 with exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemic and inflammatory injury in mice. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7: 311–320, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Toombs CF, Insko MA, Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Usansky H, Jamil K, Goldstein B, Cooreman M, Szabo C. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in healthy human volunteers during intravenous administration of sodium sulphide. Br J Clin Pharmacol 69: 626–636, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Tsai CY, Wang CC, Lai TY, Tsu HN, Wang CH, Liang HY, Kuo WW. Antioxidant effects of diallyl trisulfide on high glucose-induced apoptosis are mediated by the PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of Nrf2 in cardiomyocytes. Int J Cardiol 168: 1286–1297, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tsai KH, Wang WJ, Lin CW, Pai P, Lai TY, Tsai CY, Kuo WW. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion-induced apoptosis is mediated via the JNK-dependent activation of NF-kappaB in cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose. J Cell Physiol 227: 1347–1357, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Venditti P, Masullo P, Di MS. Effects of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion on mitochondrial function and susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1528–1537, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Verma S, Fedak PW, Weisel RD, Butany J, Rao V, Maitland A, Li RK, Dhillon B, Yau TM. Fundamentals of reperfusion injury for the clinical cardiologist. Circulation 105: 2332–2336, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Vitvitsky V, Yadav PK, Kurthen A, Banerjee R. Sulfide oxidation by a noncanonical pathway in red blood cells generates thiosulfate and polysulfides. J Biol Chem 290: 8310–8320, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wang L, Tang ZP, Zhao W, Cong BH, Lu JQ, Tang XL, Li XH, Zhu XY, Ni X. MiR-22/Sp-1 links estrogens with the up-regulation of cystathionine gamma-lyase in myocardium, which contributes to estrogenic cardioprotection against oxidative stress. Endocrinology 156: 2124–2137, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wang Q, Liu HR, Mu Q, Rose P, Zhu YZ. S-propargyl-cysteine protects both adult rat hearts and neonatal cardiomyocytes from ischemia/hypoxia injury: the contribution of the hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 54: 139–146, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev 92: 791–896, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wei WB, Hu X, Zhuang XD, Liao LZ, Li WD. GYY4137, a novel hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule, likely protects against high glucose-induced cytotoxicity by activation of the AMPK/mTOR signal pathway in H9c2 cells. Mol Cell Biochem 389: 249–256, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Westermeier F, Navarro-Marquez M, Lopez-Crisosto C, Bravo-Sagua R, Quiroga C, Bustamante M, Verdejo HE, Zalaquett R, Ibacache M, Parra V, Castro PF, Rothermel BA, Hill JA, Lavandero S. Defective insulin signaling and mitochondrial dynamics in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853: 1113–1118, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1930–R1937, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, Bengtsson A, Leviten D, Hill P, Insko MA, Dumpit R, VandenEkart E, Toombs CF, Szabo C. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol 160: 941–957, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Xu W, Wu W, Chen J, Guo R, Lin J, Liao X, Feng J. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects H9c2 cardiac cells against high glucose-induced injury by inhibiting the activities of the p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 pathways. Int J Mol Med 32: 917–925, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Yang G, Pei Y, Cao Q, Wang R. MicroRNA-21 represses human cystathionine gamma-lyase expression by targeting at specificity protein-1 in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 227: 3192–3200, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science 322: 587–590, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Yin C, Salloum FN, Kukreja RC. A novel role of microRNA in late preconditioning: upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and heat shock protein 70. Circ Res 104: 572–575, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Zanardo RC, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J 20: 2118–2120, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Zhang Y, Li H, Zhao G, Sun A, Zong NC, Li Z, Zhu H, Zou Y, Yang X, Ge J. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates the recruitment of CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells and regulates Bax/Bcl-2 signaling in myocardial ischemia injury. Sci Rep 4: 4774, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener. EMBO J 20: 6008–6016, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Zhou X, An G, Chen J. Hydrogen sulfide improves left ventricular function in smoking rats via regulation of apoptosis and autophagy. Apoptosis 19: 998–1005, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zhou X, Lu X. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits high-glucose-induced apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 238: 370–374, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Zhou X, Zhao L, Mao J, Huang J, Chen J. Antioxidant effects of hydrogen sulfide on left ventricular remodeling in smoking rats are mediated via PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of Nrf2. Toxicol Sci 144: 197–203, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Zhou Y, Wang D, Gao X, Lew K, Richards AM, Wang P. mTORC2 phosphorylation of Akt1: a possible mechanism for hydrogen sulfide-induced cardioprotection. PLoS One 9: e99665, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Zucker IH, Xiao L, Haack KK. The central renin-angiotensin system and sympathetic nerve activity in chronic heart failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 126: 695–706, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]