SUMMARY

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as crucial mediators of intercellular communication, being involved in a wide array of key biological processes. Eukaryotic cells, and also bacteria, actively release heterogeneous subtypes of EVs into the extracellular space, where their contents reflect their (sub)cellular origin and the physiologic state of the parent cell. Within the past 20 years, presumed subtypes of EVs have been given a rather confusing diversity of names, including exosomes, microvesicles, ectosomes, microparticles, virosomes, virus-like particles, and oncosomes, and these names are variously defined by biogenesis, physical characteristics, or function. The latter category, functions, in particular the transmission of biological signals between cells in vivo and how EVs control biological processes, has garnered much interest. EVs have pathophysiological properties in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, infectious disease, and cardiovascular disease, highlighting possibilities not only for minimally invasive diagnostic applications but also for therapeutic interventions, like macromolecular drug delivery. Yet, in order to pursue therapies involving EVs and delivering their cargo, a better grasp of EV targeting is needed. Here, we review recent progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms underpinning EV uptake by receptor-ligand interactions with recipient cells, highlighting once again the overlap of EVs and viruses. Despite their highly heterogeneous nature, EVs require common viral entry pathways, and an unanticipated specificity for cargo delivery is being revealed. We discuss the challenges ahead in delineating specific roles for EV-associated ligands and cellular receptors.

INTRODUCTION

Viruses and extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous, mostly submicron-sized biological particles produced by living, metazoan cells; they are capable of intercellular transfer of biological materials and genetic information. While the machineries that produce viruses and EVs in mammalian cells have many commonalities (1), viruses have been presumed to be unique in their ability to replicate a genome in host cells. Enveloped viruses cover their capsid structure in a surrounding, host-derived membrane, while envelope proteins on the surface coordinate cellular tropism (2). Nonenveloped viruses have an outer protein coat that is resistant to harsh conditions, such as dryness and extreme pH or temperature. These viruses are often virulent, causing host cell lysis upon virion release.

Recent observations have challenged the traditional classification of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses. It appears that both enveloped and nonenveloped viruses have evolved with ingenious cell entry mechanisms, hijacking host cellular membranes for genome delivery into selected permissive cells. Thus, the distinctions between viruses and certain types of EVs are blurring. These recent insights fit with the increasing realization that viruses exploit EVs for several purposes: (i) to enter host cells, (ii) to promote viral spread, and (iii) to avoid immune responses. The contribution of EVs to viral infections may have broad implications for future vaccine development (3, 4). A compelling argument for EVs having a role in viral infections is that EVs produced by virus-infected cells have altered physiological properties (5), for example, interfering with, rather than triggering, immunological responses (6). Apart from incorporating viral proteins, recent studies have indicated that EVs can contain virus-derived nucleic acids, including functional, noncoding microRNAs (miRNAs) (7, 8).

Despite major advances in EV research concerning molecular characterization, EV cell entry mechanisms have received less attention, and it has remained unclear if selective cell targeting is achieved and how, for example, EV RNA content is delivered. Recent in vivo studies have begun to address a portion of these questions by looking at biodistribution upon intravenous administration of “purified” EV populations, but these studies have so far not revealed highly specific targeting mechanisms (9). One explanation could be that such studies have typically relied on administering nonphysiological amounts of purified EV preparations. Despite limitations, selectivity in EV targeting in vivo has been revealed between astrocytes and microglia (10) in mice, in experiments with purified astrocyte-derived EVs, although appropriate control EVs from a different cell type, such as neurons or completely unrelated immune cell exosomes, were not used. In a more recent study, it was shown that specific integrin expression patterns on EVs may cause specific target cell selection (11). EV targeting in vivo was also demonstrated with genetic mouse models that made use of the Cre-lox system with defined donor and recipient cells (12–14). This innovative strategy, successfully employed by independent groups in different mouse models, has demonstrated that functional cell-cell RNA transfer in vivo can occur via EVs, providing new opportunities to study EV targeting and entry mechanisms in a physiological context. Nevertheless, many molecular details await elucidation.

In contrast, viral entry mechanisms that are mediated by specific receptors have been broadly studied both in vitro and in vivo, and research in this area has culminated in successful clinical applications (2). Increased knowledge of the molecular mechanisms by which EVs deliver their cargo into target cells may ultimately improve virus-based vaccination, drug delivery, and gene therapy strategies and expand basic understanding of oncogenesis (15). Relative to their size, viruses display a complex “life” cycle, coevolving with their hosts presumably over long periods of time. EVs, however, are far from uniform and exist in many shapes, sizes, and forms, all presumably with multiple physiological functions and properties, although assigning specific tasks to EV subtypes has proven challenging. The same holds true for (sub)viral particles that share similarities with EVs or perhaps are better classified as virus-modified EVs. Arguably, exosomes are the most recognized EV subtype that is exploited by viruses (1). Exosomes are commonly defined as budding into multivesicular bodies (MVBs), a specialized type of late endosomes, as intraluminal vesicles, and they are secreted when the delimiting MVB membrane fuses with the plasma membrane (PM) (16). Direct mechanistic evidence for the phenomenon of MVB-PM fusion remains underwhelming, and it is currently unknown if MVB-PM fusion and exosome exocytosis are a regulated or constitutive process (or both) (17). Exosomes probably also come in subtypes that carry distinct cargo molecules, depending on the subcellular location and membrane domain from which they were formed (18). We have referred above to several excellent reviews that have documented our recent understanding in exosome biogenesis.

Exosomes have been shown to serve two prominent biological purposes during viral infections: one is the ability to transport complete viral genomes into target cells, and the second is to facilitate infection by changing the physiology of target cells. Exosomes that promote viral infection, for example, have been shown to blunt immune responses (19). There also two main mechanisms by which exosomes may exert specific physiological functions on target cells, apart from a purely cellular waste disposal function, as indicated by early evidence (20, 21). First, binding of exosomes to the target cell surface may be mediated by specific ligand-receptor recognition, triggering downstream signaling events. Second, exosomes could deliver cargo either by rapid fusion with the target cell, leading to “direct” delivery of exosomal content into the cytoplasm, or upon an entry process generally referred to as receptor-mediated endocytosis. Internalized exosomes may subsequently fuse with the limiting membrane of the endosome, leading to the release of exosomal contents into the cytoplasm. It must be noted, however, that these processes are highly interrelated (22). In recent years, ample evidence has been provided that exosomes carry and deliver viral genomes into recipient cells in vitro, as shown for hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) (3, 23, 24). Encapsulation of viral (RNA) genomes in host membranes may be a conserved strategy to protect from antibody-mediated neutralization. There is some evidence that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can utilize dendritic cell-to-T cell vesicle transfer as an alternative route for productive infection, a mechanism called trans-infection (25), which may also be utilized by certain types of EVs (26). Combined, these studies seem to confirm the premise of the Trojan exosome hypothesis that was proposed over a decade ago by Gould et al. (27) and was recently adapted (28). Apart from EVs packaging viral genomes, EVs can also incorporate selective sets of virus-encoded proteins and/or nucleic acids that could trigger immune responses. Several published reviews have dealt with the immunological properties of such EVs during viral infection and have categorized their composition and molecular contents to a large extent (5, 6, 19, 29). Unfortunately, the exact mechanisms and specific molecules that are required for EV-mediated cargo delivery are poorly understood. To effectively combat pathogenic viruses that exploit EVs for their transmission, a detailed understanding of their entry mechanisms is required.

In this communication, we review the current understanding of mechanisms of EV entry and propose how infection strategies of viruses may provide clues into the mechanisms involved. We further address how EVs convey physiologic effects, how they are transmitted between cells, and how specificity of cellular targeting might be achieved. For example, it is difficult to imagine that all EVs mediate functional transfer of nucleic acids. In circulation, it has been estimated that 1 ml of plasma contains 1 to 10 billion EVs (30). As may be expected, the copy number of any given nucleic acid, for example, miRNAs, in this EV fraction is much smaller (31). Due to the vast heterogeneity of EVs and our lack in understanding their specific production and release pathways, it remains difficult to study, or even predict, what the physiological effects of EVs are in vivo and how to discern the role of viruses in EV biology and vice versa. It seems reasonable to conjecture that, considering the large overlap in molecular compositions and physical properties of EVs and viruses, EVs probably “choose” their target cell and deliver their cargo in a similar fashion as described for viruses. Because EVs are complex—highly diverse in size, molecular composition, and presumably function—the study of the underpinnings of their cell entry mechanism is difficult. Indeed, results from in vitro uptake studies using purified EV populations need to be interpreted with caution and may be inapplicable to the in vivo situation, for which new tools must be developed.

Clarification of terminology and abbreviations.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs): a heterogeneous group of generally submicron-sized particles, including exosomes. Exosomes: EVs of 50 to 100 nm in diameter, secreted by many cell types; they are produced within a multivesicular body as intraluminal vesicles and secreted when the membrane of the multivesicular body fuses with the plasma membrane. Multivesicular body (MVB): a specialized type of late endosome, presumably the origin of exosomes. When it was clear in a reviewed paper that the described vesicles were derived from MVBs, they are referred to here as exosomes. In all other instances when the origin was not defined, the term extracellular vesicles, the official nomenclature used by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), has been used. We would also like to clarify upfront that in our reviewed papers, the distinction between binding and fusion, as a molecular event, was challenging.

VIRUS AND VIRAL GENOME DELIVERY VIA EVs

Because of the difficulties that arise from studying the heterogeneous population of EVs, it is reasonable to study overlap between targeting pathways of EVs and viruses. Just as viruses might use EVs to deliver their genomes, EVs might use entry receptors and fusion machinery similar to those used by viruses.

Common Transport Mechanisms of EVs and Viruses

It has been argued provocatively that viruses may have adopted existing EV-mediated communication pathways for their infection strategies (32). A notable example is the recent realization that many enveloped viruses utilize phosphatidylserine receptors as part of their targeting and entry strategies (2, 33). The exposure of phosphatidylserine groups on the surfaces of exosomes has been observed in many studies (10, 34, 35) and may thus be one of the shared targeting mechanisms of exosomes and viruses. Since EVs participate in viral pathogenesis, an understanding of the mechanisms behind EV targeting and transmission may have important implications for the design of next-generation antiviral vaccines and therapeutics. To provide a perspective on these mechanisms, we first examined the evidence for virus or viral genome delivery by EVs (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

List of exosome-utilizing viruses

| Viruses that may utilize exosomes | Reference(s) |

|---|---|

| Enveloped DNA viruses | |

| EBV | Pegtel et al. (7), Vallhov et al. (98), Ruiss et al. (100) |

| HHV-6 | Mori et al. (55), Ota et al. (24) |

| Nonenveloped DNA viruses | |

| Adenoviruses 2 and 5 | Gastaldelli et al. (120) |

| Reovirus | Stewart et al. (125) |

| KSHV | Veettil et al. (126) |

| Enveloped RNA viruses | |

| Dengue virus | Chahar et al. (167), Van Der Schaar et al. (122), Meertens et al. (170) |

| HCV | Masciopinto et al. (37), Ramakrishnaiah et al. (36), Longatti et al. (42), Bukong et al. (43) |

| Influenza A virus | Rust et al. (123) |

| HIV | Puryear et al. (145), Akiyama et al. (146), Cladera et al. (154) |

| GBV-C | Maidana Giret and Kallas (44) |

| SFV | Taylor et al. (121), Gastaldelli et al. (120) |

| Nonenveloped RNA viruses | |

| Picornavirus | Feng et al. (23, 59) |

| Coxsackievirus | Robinson et al. (51), Klionsky et al. (53), Paloheimo et al. (52) |

HCV, molecular hitchhiker.

In 2013, Ramakrishnaiah and colleagues reported that productive hepatitis C virus infection of cultured human hepatoma cells could be established by virion-free exosomes (36) purified from infected cells. To be sure, it had been known for some time that HCV protein can be incorporated into nonvirion EVs (37). Also, electron micrographs of HCV preparations from cell cultures showed the presence of exosome-like particles that were larger than canonical HCV virions (38), although these particles were eliminated by affinity purification (39). Finally, a provocative article in 2012 showed that HCV RNA could be transferred to nonpermissive plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), triggering innate immune responses (40). However, the elaboration that replication-competent RNA could be transmitted by EVs blurred the distinction between host and viral vesicles, attracting broad attention to the topic (3, 41). Full-length RNA was transmitted by exosomes not only from cells infected with HCV clone Jc1 but also from cells containing a subgenomic replicon that did not encode viral structural proteins E1, E2, and core (36). This suggested that at least some viral proteins were dispensable for the “quasi-infectivity” of genome-containing EVs. Further evidence for virion-independent genome shuttling was provided recently in a study that employed a set of cells with resistance to different antibiotics to distinguish between true EV-mediated RNA transfer and cell-cell fusion (42). Szabo's group, meanwhile, provided an important step toward understanding the in vivo relevance of the phenomenon, finding infectious exosomes in blood of HCV patients (43). Those authors also reported that viral RNA in exosomes was complexed with Argonaute 2 (Ago2) and the replication-enhancing host miR-122 (43).

Do other enveloped viruses shuttle genomes in EVs?

We continue to await evidence that the EV-based alternative infection strategy of HCV is in general use by enveloped viruses. The genome of GB virus C (GBV-C, also known as human pegivirus, or hepatitis G virus), a virus associated in some studies with reduced mortality and morbidity of HIV-1-coinfected individuals (44), appears to be infectious when incorporated into serum EVs (45). To date, though, there is no convincing indication that retroviruses use this method. Various HIV-1 RNAs and proteins have been detected in EVs, and effects have been imputed to some of these (8, 46–49). In one report, several unspliced HIV RNA sequences were found in association with exosomes, consistent with full-length genome incorporation (46). Spliced RNAs were not detected. In another study, short HIV-1 transactivation response (TAR) element transcripts were found in exosomes released from infected cells, along with smaller RNAs processed from the TAR element (8). However, retroviral RNA conveyed in exosomes has not been found to be infectious (8, 46). Similarly, exosomes from human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-infected cells have not been found to be infectious (50). Even if full-length retroviral RNA could enter cells via exosomal delivery, in contrast with, e.g., HCV, it would be unlikely to replicate without a functional viral reverse transcriptase. However, it remains formally possible, if somewhat implausible, that different EVs could deliver required components to a recipient cell in trans.

No envelope? No problem.

Several nonenveloped viruses are now known to have alternative infection capabilities via EV pathways (Table 1). Coxsackievirus B3 is one nonenveloped virus that subverts host EVs. Spreading between cells via shed microvesicles, the virus avoids neutralizing antibodies that are already present (51, 52). Coxsackievirus-bearing microvesicles display not only autophagosomal marker LC3 II (53) but also flotillin-1, which is thought to be a general exosome marker (54). Ota et al. showed that T cells infected by HHV-6 evaded the host immune response by shedding major histocompatibility complex class I molecules via viral particles and exosomes (24). Another study reported that HHV-6-infected cells even increase MVB and exosome formation to enhance viral glycoprotein release through the exosomal release pathway (55). Another example of a virus that uses the EV machinery of the host cell is the nonenveloped picornavirus hepatitis A virus. It appears that there are two distinct virion fractions of HAV (23): the classical nonenveloped form and a second form, in which virus-like particles are encapsulated in host-derived membrane structures that closely resemble exosomes (eHAV). When circulating in patient blood, these eHAVs are fully infectious and fully mimic enveloped viruses (23).

eHAV, HIV, and exosome biogenesis.

Mechanistically, many viruses and virus-like EVs rely on the same biogenetic pathways. For example, eHAVs involve the ESCRT pathway, the same system that supports exosome biogenesis into MVBs (23). However, ESCRT components may also be involved in domain budding from the plasma membrane through ARRDC1 molecules (56) and are recruited to PM sites of HIV budding by HIV Gag (57). In fact, the mechanisms of budding at PM and MVB have many similarities, as recently highlighted (58). In the case of HAV envelope acquisition, knockdown of VPS4B and ALIX, two ESCRT-associated proteins, reduced release of eHAV significantly (23).

EVs: vehicle or trap?

By borrowing a host envelope, presumably with no or fewer exposed viral proteins, viruses or viral genomes are less likely to be susceptible to neutralizing antibodies in circulation. Indeed, eHAV is less detectable by the adaptive immune system, consistent with the observation that detection is delayed in HAV infection by 3 to 4 weeks before specific antibodies are formed (23). Similarly, HCV RNA-containing EVs were recognized, albeit significantly less readily, by neutralizing antibodies (36). Interestingly, however, the enveloped form of HAV is more prone to capture by pDCs (59). Thus, while eluding neutralizing antibodies, eHAV may be more prone to recognition by innate immune sensors (59). This finding supports the notion that human pDCs have adapted to detect potentially pathogenic virus infections by internalizing exosome-like vesicles carrying infectious HCV genomes (36, 40, 43). Apart from HCV and HAV, we have evidence that latent herpesvirus-infected cells are also recognized in this manner (60), suggesting a general role for exosomes in pDC-mediated sensing of RNA and DNA viruses. Questions remain about how EVs incorporate, transport, target, and deliver viral genomes into permissive and/or sensory target cells and whether dedicated receptors are involved.

Target Cell Selectivity of EVs

Most published studies of the physiological properties of EVs have been performed in vitro and were pioneered by Morelli and colleagues (61). We were among the first to show that viral miRNAs could be transferred from B cells via exosomes. In our model, we exploited latently Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected cells to prevent viral DNA transmission from obscuring transfer experiments (7). While these studies unequivocally showed that EV populations in coculture carry and deliver virus-derived nucleic acids, i.e., noncoding miRNAs into target cells, we did not study the mechanisms by which delivery was mediated. Upon release by producing cells, viruses must find their target cells via cell surface receptors. Receptor usage is a key factor in defining the tropism of many viruses (2).

Challenges in EV targeting experiments.

In our laboratory, we regularly stain purified EVs from latently EBV-infected cells with a lipid dye and incubate these with various recipient cells in culture. Most cell types, sooner or later, internalize at least a proportion of stained exosomes, seemingly regardless of the cells of origin (Fig. 1). This also reflects the heterogeneous nature of most EV populations (18). Because the EVs from EBV-infected cells carry viral RNA and viral proteins, including on their surface, it is possible these types of vesicles are prone for attachment and internalization. On the other hand, infectious virions are relatively uniform in size and composition; therefore, they may be much more selective in targeting experiments. Again, this is almost certainly not true for EVs, making it difficult to predict how and which EVs or subpopulations thereof target what cells, since there are as yet no established methods to separate EVs into biologically meaningful subpopulations, or to study them individually. While advances are being made to achieve this goal, for example, via powerful flow cytometry approaches (62), one can be sure that all EVs must attach to the surface of target cells in order to have any physiological function.

FIG 1.

Exosomes enter internal compartments of dendritic cells. Green fluorescent exosomes from EBV-infected B cells internalized by primary, activated monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) are shown. The actin cytoskeleton is shown in red (phalloidin staining) and this highlights protrusions of the activated MoDCs.

Virus Attachment Molecules Are Exposed on the EV Surface

Adhesion molecules on EV surfaces.

A scan of the EV proteomic databases (ExoCarta and EVPedia) (63–65) reveals the presence of many adhesion molecules. These include integrins and cell adhesion molecules, both members of the immunoglobulin-like superfamily. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 from the immunoglobulin G superfamily are enriched in many EVs, a feature that seems independent of the producing cell type. The immunoglobulin superfamily of proteins is characterized as having domains of between 7 and 9 β-strands arranged in two antiparallel sheets that form a sandwich structure, stabilized by a conserved disulfide bridge. While VLA-4 seems enriched on the surface of reticulocytes and B cell exosomes (66, 67), αM integrin (ITG) and ITGβ2 are present on dendritic cell exosomes (68, 69). Attachment of EVs onto the target cell can be facilitated by ITGβ1, ITGα1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1, which are expressed on the target cells, although EVs may also bind to the extracellular matrix (ECM) in an ITGβ1 (ITGα4) cation-dependent matter (70, 71). Uptake of DC-derived exosomes has been defined more clearly. DC-derived, ICAM-1-bearing exosomes bind to activated T cells via lymphocyte-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) and to DCs via LFA-1, ITGαv, and ITGβ3 (61, 72, 73). Intriguingly, recent data suggested that integrins have a role in cell-specific targeting of breast cancer exosomes. Hoshino and colleagues recently defined specific repertoires of integrins expressed on tumor-derived exosomes that seemed distinct from the tumor cells (11). They revealed that integrins might dictate exosome adhesion to specific cell types and ECM molecules in particular organs. Notably, exosomes expressing ITGαvβ5 seem to bind specifically to Kupffer cells, mediating liver tropism, whereas exosomal ITGα6β4 and ITGα6β1 bind lung-resident fibroblasts and epithelial cells, governing lung tropism. Finally, exosomes that seem to lack a specific integrin repertoire home to bone tissue. It will be interesting to learn more about the extent to which integrins are indeed dominant exosomal targeting factors in additional contexts. For example, would the same integrin repertoire on exosomes from a lymphoma have a similar organ tropism to that described? Quantitative data on lymphoblastoid cell line exosomes compared to primary B cell exosomes suggest major differences in ITG composition between the exosome populations (60).

In comparison to EVs, viruses also use various receptors for their multistep attachment and cellular entry process and often induce changes on the target plasma membrane, activating signaling pathways (74). Selectivity of EV binding may also be reliant on exogenous cues. Under inflammatory conditions, surface adhesion molecules are activated in fibroblasts that could then tether EVs more firmly (71). This happens, e.g., in an ITGβ2- and ITGβ1-dependent manner. ITGβ2 couples with ICAM-1, and ITGβ1 still binds to ECM, with possible additional binding to VCAM-1. Moreover, ITGαvβ6 is actively packaged into exosomes isolated from prostate cancer cell lines. Apart from having a potential adhesion function, αvβ6 is also efficiently transferred via exosomes from a donor cell to an αvβ6-negative recipient cell and localizes to the cell surface (75). Many adhesion molecules, such as ICAMs and integrins, are also inserted into so-called tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) (76, 77).

Tetraspanins: a role in EV target cell selection?

Tetraspanins (TSPANs) have been proposed to have a role not only in EV formation but also in exosomal fusion with the target cell. TSPANs consist of four transmembrane regions, with intracellular amino- and carboxy-terminal tails. According to several studies, tetraspanins CD9, CD63, CD81, CD82, CD151, Tspan8 (D6.1A), CD37, and CD53 are enriched in exosomes (78–82). The exact composition of the tetraspanin web on exosomes may have implications for target cell selection (83). Most TSPANs execute their function in cooperation with integrins. For example, Tspan8 is known to form complexes with integrins. Tspan8-CD49 complexes on exosomes seemed to induce uptake of exosomes by endothelial cells (84). However, a tidy separation of EV subsets by assessing tetraspanin incorporation is complicated by heterogeneity at the biological and technical levels (85). Although substantial work has been done in this area (82), many questions remain. Which tetraspanins are enriched in exosomes versus other vesicles? Is there indeed a “tetraspanin code” to separate subclasses of EVs? To what extent is tetraspanin enrichment dependent on cell type, cell activation states, and experimental treatments? If certain tetraspanins clearly define EV subsets, perhaps only these EVs can introduce proteins on the plasma membrane and deliver genetic material into the cytosol of target cells. Apart from such lingering questions, it is difficult to distinguish between a function mediated by attachment alone or through the actual fusion process. Nevertheless, it is clear that tetraspanins are involved in membrane fusion (86) and participate in viral entry. Indeed, as we now review, both HIV and HCV exploit tetraspanins in their life cycles.

MECHANISM OF VIRAL FUSION WITH THE PLASMA MEMBRANE

Direct Fusion of Viruses: a Model for EV Uptake?

Common mechanism of fusion.

Enveloped virus particles can fuse directly with the plasma membrane of target cells at neutral pH and after interaction with cell surface receptors. Endocytosis and subsequent endosomal fusion will be discussed later. HIV and EBV are examples of viruses that are capable of direct fusion at the cell surface to deliver their RNA genomes. The envelopes of these viruses consist of host membrane lipids, sterols, and proteins. Fusion with the plasma membrane is mediated by virus-encoded glycoproteins (74, 87) and fusogenic host factors that include tetraspanins. The first step to membrane fusion is tethering or attachment, as described above. This sets up the initial contact between virus and target cell or between other fusing entities. Docking follows, as the fusion machinery activates and connects the two membranes. To bring the membranes close together, the tertiary structure of the viral glycoproteins changes, culminating in fusion pore formation and dilatation (Fig. 2) (88). Direct evidence for direct fusion of EVs with the PM is limited, and the molecules involved await discovery. Nevertheless, EV fusion with the PM has been suggested by live fluorescence microscopy using a general lipophilic dye (R18), which increases in intensity in recipient cells (89). Viruses might provide clues as to how EVs recognize and attach to the PM and undergo fusion.

FIG 2.

Common mechanism of fusion. Here, fusion of a virus with the plasma membrane is shown, giving an example of the common (not virus-specific) mechanism of fusion. Initial contact is made through tethering. Involved molecules can contribute to target specificity and are regularly linked to fusion machinery. Tethering is followed by docking, as the fusion machinery connects the two membranes. Changes in tertiary structure of this machinery, noted as protein folding, culminate in fusion pore formation and subsequent dilatation. Insertion of fusion loops into the host cell membrane is necessary for entry.

Human immunodeficiency virus.

The HIV-1 envelope (Env) gene encodes a protein of approximately 160 kDa that becomes decorated with sugar residues and is hence referred to as glycoprotein 160 (gp160). This protein is cleaved by host proteases into gp120 and gp41 subunits. Heterodimers of these subunits cluster in threes on the surface of the virion, resulting in EM-visible “spikes” that are essential for HIV cell entry. The glycoproteins function together with several host cofactors (i.e., CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5) that act as the main determinants of viral tropism. Buried within the gp41 subunit of HIV Env, itself embedded in the viral membrane, is a hydrophobic fusion peptide. When exposed to fusion-activating conditions, the fusion peptide is exposed, undergoing a conformational change and insertion into the target membrane. Fusion activation starts when gp120 stabilizes the virus to cell attachment by binding to the primary receptor CD4, initiating conformational changes that facilitate interactions of gp120 with CXCR4 or CCR5 (Fig. 3). In turn, this event triggers conformational changes in gp41. Two well-separated α-helices fold to form a hairpin-like α-helical bundle. These bundles bring the viral and cell membrane close together, causing actual fusion of the virus and target cell membranes (90, 91). While most EVs will lack such glycoproteins, other molecules, such as tetraspanins, may have fusogenic properties (79). In agreement with the involvement of CD9 and CD81 in the membrane fusion processes (92), it has been suggested that expression of tetraspanins can alter HIV-1 progression. Tetraspanins incorporated into the membranes of virus particles may collaborate in fusion (93). In addition to its presence in transmission electron micrographs at the plasma membrane, CD63 also plays an early postentry role prior to or at the reverse transcription step of HIV (94). HIV fusion can also occur after endocytosis, as we describe below (2).

FIG 3.

HIV cell entry. HIV enters target cells via fusion with the concerted action of viral glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 and host cofactors such as CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5. The glycoproteins are visible as spikes on electron microscopy images.

Epstein-Barr virus.

In addition to HIV, human herpesviruses show plasticity in their mechanism of entry. The enveloped human large DNA herpesvirus EBV exploits CD21 (complement receptor 2) to target resting naive B cells via EBV gp350/220 glycoproteins present on its envelope. It does so in combination with other receptor-ligand reactions, including those with HLA-DR1. CD35, another complement receptor, also participates in the target specificity of EBV (95), whereas the virus can enter nasopharyngeal epithelial cells through neuropilin 1 (NRP1)-facilitated internalization and fusion (96).

A Molecular Viral Toolbox for EV Fusion

For many animal viruses, including the examples we have just visited, target cell range is limited and defined by the interaction of viral proteins with a small number of host factors; the target range of EVs remains substantially less clear. How could the above information be relevant for EV uptake by direct fusion? Although canonical host exosomal proteins, including CD81, appear to be involved in some instances of viral fusion, it is not yet established that they can achieve fusion alone. At the same time, mammals have a deep and diverse relationship with viruses, endogenous and exogenous. Is it possible that viral factors incorporated into EVs could support fusion?

Fusion is utilized as an entry mechanism for subtypes of EVs.

We found that inhibition of exosomal uptake using dynasore, a potent endocytosis inhibitor, cannot completely block the uptake of exosomes produced by EBV-infected cells (7). As proposed previously (97), then, it appears that exosomes have multiple entry options, including through the PM. EVs, in particular those released by virus-infected cells, share molecular characteristics with fusogenic viruses (i.e., incorporation of viral glycoproteins) that suggest fusion is utilized as an entry mechanism for at least some subtypes of EVs produced by virus-infected cells (Fig. 4). For example, exosomes from EBV-infected cells have a plethora of the TSPANs CD9 and CD81, but they also seem to incorporate certain amounts of viral gp350. Thus, viral envelope factors that are sorted into EVs support EV attachment and possibly fusion with target cells (98). This process was found to be so efficient that EVs outcompeted actual viral particles for entry (98). Furthermore, HCV-infected cell-derived exosomes seem to harbor CD81 and E2 glycoproteins, possibly exploiting these molecules' fusogenic capabilities (37). However, other studies claim that it is unknown whether HCV entry receptors are involved in exosome uptake (36, 43). Finally, a glycoprotein of herpes simplex virus (HSV) is also incorporated into exosomes of HSV-infected cells. Although this may serve more as an immune escape function, the fate of these virus-modified exosomes has not been studied (99).

FIG 4.

Extracellular vesicle entry via fusion. Different viral and nonviral molecules can facilitate fusion of vesicles with the target cell. HCV-infected cell-derived exosomes are enriched in CD81 and HCV glycoproteins and could possibly be taken up via fusion (37). EBV-infected cell-derived exosomes are enriched for LMP1 and gp350, possibly facilitating fusion (98, 101). Furthermore, HSV gB, CD9, and other tetraspanins could have a role in EV entry via fusion (84, 93, 99).

The propensity of EBV gp350 to mediate targeting of exosomes has recently been applied in clinical settings (100). The concept could certainly be expanded to other virus-derived molecules (29). Nor are we limited to glycoproteins. The EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) is also selectively incorporated into CD63-enriched exosomes and may have several purposes (101). Besides signaling domains, LMP1 contains a hydrophobic peptide motif that resembles that of fusogenic retrovirus proteins (Fig. 4) (102).

Endogenous retroviruses.

Interestingly, human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), partial sequences at least of which are abundant but usually inactive in mammalian genomes, can become activated in tumor cells and under certain physiologic conditions. Products of these ancient viruses have been detected in EVs (103). Is it possible that these endogenous viral products endow EVs with the ability to choose and enter target cells? If so, tumor cells may exploit the viral machinery not only to produce vesicles but also to direct their ability to transmit signals via ancient viral fusion factors. Standard proteomic analyses may miss such molecules, matching acquired data with characterized, commonly expressed human or mouse peptides.

Provocatively, a physiological role for “virus-driven” modification of exosomes has been described. In recent years, several reports have demonstrated that endogenous retrovirus group W, member 1, commonly known as syncytin-1, and endogenous retrovirus group FRD, member 1, referred to as syncytin-2, are encoded by HERV genes and are important players in syncytiotrophoblast formation (16–19). Both syncytin-1 and syncytin-2 are presumably former retroviral envelope (Env) genes that have retained a fusogenic ability. The fusion events facilitated by syncytin are crucial for maintenance and formation of the syncytiotrophoblast. Crucially, use of a human/hamster radiation hybrid panel identified as major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2 (MFSD2) as the gene coding for a receptor that contains multiple membrane-spanning domains and mediates cell-cell fusion and infection by retroviral pseudotypes bearing syncytin-2. Remarkably, screening human tissues by reverse transcription-PCR demonstrated that MFSD2 expression is placenta-specific and, more precisely, localized in the syncytiotrophoblast as revealed by in situ hybridization (104). Interestingly, villous trophoblasts in the placenta produce exosomes that seem to specifically incorporate both syncytin 1 and 2, which enter their target cells not through direct fusion with the PM but first through endocytosis followed by fusion with the endosomal membrane (Fig. 5). This suggests that an internal receptor may mediate fusion. Moreover, circulating syncytin 2 is reduced in circulating exosomes isolated from women with preeclampsia, a placental pathology specific to the human species and that can culminate in maternal and perinatal morbidity (105). Finally, both syncytin 1 and 2 are downregulated in placentas from pregnant women, suggesting placental exosomes may have a physiological role in human placental morphogenesis (78). Thus, apart from direct fusion of exosomes with the PM, endocytosis is a second internalization pathway used by EVs and many viruses.

FIG 5.

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis used by EVs. EPS15, one of the two main integral components of a clathrin-coated pit, has a partial role in uptake of possible subtypes of EVs via CME. Blocking endocytic pathways partially inhibits EV uptake (34, 127). Villous trophoblast-derived exosomes seem to incorporate syncytins 1 and 2, which could facilitate endocytosis of these EVs (78, 103, 105).

THE ENDOCYTIC PATHWAY AS ENTRY MECHANISM

Many viruses exploit endocytic pathways to enter host cells, as described and compared in excellent reviews elsewhere (2, 106). The entry pathways of EVs have many similarities, but because of the lack of a common method to isolate and purify EV (subtypes) (107), it is difficult to find a common pathway or strategy of EV uptake and function (97). Endosomal trafficking is thought to offer several advantages for viruses which, upon cell entry, sidestep degradation in the unfriendly environment of the endolysosomal pathway. For example, viruses entering the endosomal pathway can escape immune surveillance and bypass restriction factors or physical obstacles, such as the actin cortex. This route also provides viral particles with rapid transport to the cell nucleus. As we have seen, HIV enters endosomal compartments of DCs and, upon cellular entry into lymphoid tissue, releases this “stored” and protected HIV to infect T cells. Intriguingly, an analogue of this “trans-infection” has also been described for exosomes (26), endowing the rereleased vesicles with an intercellular Wnt signaling capacity.

The internalization of viruses into the cytosol by endocytosis has been divided into several mechanistic categories: (i) clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME), (ii) macropinocytosis, (iii) caveolar/lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and, albeit less characterized, (iv) clathrin- and caveolin-independent mechanisms. Generally, after internalization within the primary endocytic vesicles, the engulfed material, including viruses, ligands, hormones, growth factors, lipids, etc., follows the same intracellular pathways, and the complex endosomal trafficking system will determine the final destination and function of the internalized molecule (108). The fate of internalized material could be subject to sorting, processing, recycling, or degradation in lysosomes that frequently reveal a laminar ultrastructure. The realization that endosomal membranes also act as platforms for signaling complexes and possibly have a direct role in gene regulation (109, 110) suggests a division of tasks that could have important implications for EV and virus-mediated delivery of functional biomolecules.

The endosomal system is classically categorized into compartments known as early endosomes (EEs), late endosomes (LEs), recycling endosomes (REs), and lysosomes (Lys), each with distinct membrane domains and internal structures. Due to diverse domains, association with distinct Rab GTPases traditionally defines the endosomal compartments. Rabs are the main regulatory proteins in membrane trafficking, vesicle formation, vesicle movement along actin and tubulin networks, and membrane fusion (111, 112). EEs are generally defined as RAB5-containing compartments, and they are the first to receive endocytosed material from the PM. EEs reveal a complex tubular-like ultrastructure and are responsible for sorting and trafficking of internalized molecules to different intracellular targets. Some endosomes undergo maturation and are RAB5 and RAB7 positive. These belong to a class of intermediate organelles, serve as precursors for LEs, and are suspected to play a key role in entry of many viruses (113, 114). A specialized form of maturing LEs are the so-called multivesicular bodies, which are highly dynamic sorting platforms that support the budding process of viruses and exosomes (115).

Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis

A common infection pathway exploited by many animal viruses is CME, which involves the internalization of molecules through clathrin-coated vesicles (116). Clathrin is a molecular scaffold protein that forms transport vesicles of material at the plasma membrane. These vesicles are eventually pinched off by a mechanism called membrane scission and undergo clathrin uncoating through GTP hydrolysis-mediated changes of dynamin 2. The uncoated vesicles become fusogenic, allowing release of their content within EEs (117).

CME of viruses.

In CME, viruses and their transmembrane receptors are packaged into clathrin-coated vesicles. CME as a mechanism for viral entry was first observed in Semliki forest virus (SFV) infection (118–121). Investigating entry led to the discovery that CME is used as the entry mechanism by many, mainly single-stranded RNA enveloped animal viruses, including dengue, hepatitis C, and influenza A viruses (122, 123). However, double-stranded DNA viruses, including adenovirus 2 and 5 and the dsRNA reovirus (120, 124, 125), exploit this pathway, albeit using different receptors. Importantly, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) enters human fibroblast cells by dynamin-dependent CME, but in dermal endothelial cells, entry is oddly dynamin independent (126). Thus, CME-exploiting viruses sometimes have alternative entry routes, depending on the target cell.

CME of EVs.

For EVs, type-specific dissimilar entry routes have not yet been described, partially because it remains challenging to isolate a pure single EV type. The main integral component of a clathrin-coated pit is a complex of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate clone 15 (EPS15) and adaptor protein 2 (AP2). CME inhibition by a dominant-negative EPS15 results in a significant reduction of EV uptake (34), but not complete inhibition. Those authors explained this result as an indication that EPS15 has a partial role in uptake of EVs through CME. An alternative explanation may simply be that not all EVs require EPS15 for uptake into their target cell, stressing the need for better characterization and identification of EV subtypes. Indeed, recent studies showed that not all EV uptake can be inhibited by targeting multiple endocytic pathways. Besides CME, uptake by macropinocytosis and caveolin-mediated endocytosis are main routes for cellular internalization of viruses (2). For EVs, this seems to be similar. Tian and colleagues showed that PC12 cell-derived exosomes enter target cells through CME and macropinocytosis (127). They identified CME to be involved in the internalization by using different methods, such as pretreatment with K+ depletion buffer, which blocks the clathrin-coated pits, knocking down the clathrin heavy chain, the basic subunit of clathrin, and μ2, the subunit of clathrin adaptor complex AP2, all resulting in significant decrease in exosome uptake by PC12 cells (127). Moreover, another study indicated that exosomes can be taken up via lipid raft-mediated endocytosis (128). Disrupting lipid rafts and inhibiting tyrosine protein kinase are two of the most widely used techniques for blocking this endocytic pathway. Even so, in PC12 tumor cells, disruption of this pathway through general means did not affect PC12 exosome uptake.

As previously mentioned, studying EV uptake is challenging, because of the heterogeneity in size, shape, and composition of EVs. However, one of the most reliable methods of studying EV entry is fluorescent labeling. In a study by Nanbo et al., this method was used to clarify the exact mechanism of EV release from EBV-positive cells and their function in recipient cells. Those authors analyzed the internalization of fluorescently labeled exosomes derived from EBV-uninfected and type I and type III latency EBV-infected cells into EBV-negative epithelial cells. CME and caveolin-mediated endocytosis were identified as possible EV entry pathways, targeting dynamin 2, which plays a crucial role in both pathways. Treating cells with dynasore (dynamin-specific inhibitor) resulted in a decrease but not total blockage of EV uptake (129), supporting the outcome of other studies that these endocytic pathways are partially involved in EV entry in specific cell types (Fig. 5).

Dynamin 2 also has a crucial role in membrane curving during CME, especially in uptake into specialized professional phagocytic cells, such as macrophages, microglia, neutrophils, and monocytes. The studies by Feng et al. suggested that exosomes are, perhaps not surprisingly, internalized more efficiently by phagocytic cells (34). Labeled exosomes moved to phagosomes together with phagocytic polystyrene carboxylate-modified latex beads and appeared to be sorted into lysosomes. In these studies, exosome internalization was dependent on actin remodelling and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Pi3K), and the entry process was sensitive to both knockdown of dynamin 2 and overexpression of a dominant-negative form of dynamin 2. However, in other studies, short hairpin RNA against dynamin 2 also reduced to 50% the uptake efficiency of tumor EVs, indicating that dynamin-dependent endocytosis was involved. Control experiments with latex beads excluded phagocytosis as the main mechanism for tumor exosome uptake by PC12 cells (127). Despite these observations that suggest some selectivity for EV cell entry, strong evidence for selective CME-dependent EV transfer is still lacking. Because many viruses use CME as the main entry pathway upon surface receptor attachment, largely explaining cellular tropism (2), it seems logical to focus mechanistic EV entry studies in this direction. Notably, for RNA-carrying EVs, the CME pathway may be essential for function as the host intercellular messenger or as an alternative stealth transmission mode for viral genomes, as shown for HCV (3).

HCV Cell Entry as a Model To Study EV Uptake Mechanisms

Hepatitis C virus.

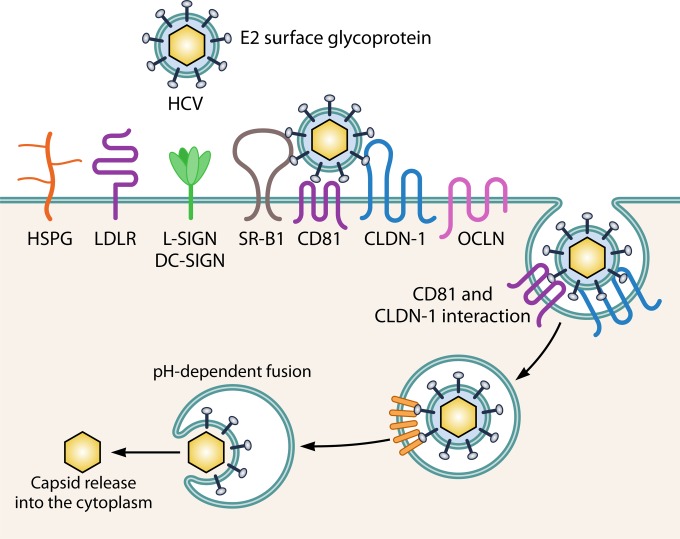

Like the heterogeneous population of EVs, the 40- to 80-nm pleomorphic HCV particles are difficult to characterize (38, 39). As we expect for EVs, HCV is known for its variety of uptake-associated molecules. HCV cell entry (Fig. 6) is a complex multistep process involving the presence of many entry factors, which are tightly coordinated in time and space (2, 130); therefore, this process provides a possible model to study EV uptake.

FIG 6.

HCV cell entry. HCV has a plethora of molecules involved in entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Initial attachment to the target cell is facilitated by HSPG, LDLR, or L-SIGN/DC-SIGN. Followed by interaction with the main receptors SR-B1 and CD81, TfR1 (not shown) could have a post-CD81 role in HCV entry, and SRFBP1 (not shown) is possibly recruited to CD81 during HCV uptake, coordinating host cell penetration. Late actors in the entry process are CLDN-1 and OCLN. NPC1L1 (not shown) might act in the entry process concerning cholesterol transport.

The complex process of HCV cell entry.

HCV is believed to initially infect the liver through the basolateral side of hepatocytes, where it engages its main attachment factors, heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG), low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) (131). Subsequently, HCV interacts with coreceptor CD81, which is composed of four transmembrane passages, a small extracellular loop (SEL) and a large extracellular loop (LEL), and the tight junction protein claudin-1 (CLDN-1) (132). Many have studied the mechanisms of HCV cell entrance in detail, all pointing to receptor-mediated endocytosis of HCV by CME (133). CD81, reported as a binding receptor for HCV in 1998 (134), has proven to be a central player in HCV entry in part by binding directly to the HCV E2 surface glycoprotein that mediates endosomal fusion (134–136). Despite numerous studies of the CD81-HCV E2 (envelope) interaction, it was argued initially that the role of CD81 as a putative virus receptor was doubtful, because of its ubiquitous expression in vivo. Indeed, CD81 is far from the only determinant of HCV tropism, as recently illustrated by the discovery of six CD81 binding partners that promote HCV infection, including serum response factor binding protein 1 (SRFBP1) (137). With a comprehensive quantitative proteomics protocol, those authors identified 26 dynamic binding partners of HCV-triggered interactions with CD81. As many as six of these proteins promoted HCV infection, as indicated by RNA interference (RNAi) studies (137). SRFBP1 is recruited to CD81 during HCV uptake, supporting HCV infection of hepatoma cells and primary human hepatocytes. While all viruses have evolved elaborate entry strategies, HCV is the current champion in complexity, requiring a plethora of molecules, including HSPG, liver/lymph node-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing integrin (L-SIGN), dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), LDL-R, transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1), SR-B1, CD81, CLDN-1. and occludin (OCLN), highlighting the difficulties in understanding possible entry mechanisms of EVs (130). Resembling HCV, EV target selectivity is unlikely to be determined by a single target cell factor. Interestingly, however, it has been very recently demonstrated that exosomes enriched in CD81 from HCV-infected cells are capable of transmitting infection to naive human hepatoma cells even in the presence of neutralizing antibodies (36, 43), while anti-CD81 antibodies seem to prevent infection in vivo (138, 139).

Because both HCV virions and host exosomes have a role in HCV infection, it may be highly informative to investigate whether exosomes produced by HCV-infected cells have a similarly complex receptor usage. To date, most studies have used lipid dyes to study EV uptake by target cells; since this tracing method will not discriminate between EV subtypes, it will probably be essential to develop better purification and reporter methods to identify any EV-specific entry receptors.

MACROPINOCYTOSIS

Macropinocytosis mediates nonselective uptake of small soluble molecules such as nutrients, antigens, and other components of the extracellular medium, leading to macropinosome formation. Macropinosomes are relatively large and therefore provide an efficient route for nonselective endocytosis (140). Macropinocytosis is accompanied by actin reorganization, ruffling of the plasma membrane, and engulfment of relatively large volumes of extracellular fluid. Like CME, macropinocytosis facilitates cell entry for viruses, bacteria, and some protozoa (141). In particular, viruses belonging to the vaccinia virus, adenovirus, picornavirus, and other families have been reported to take advantage of macropinocytosis, either as a direct endocytic route for productive infection or indirectly, in order to assist in penetration of particles that have already entered by other endocytic mechanisms. Viruses that benefit from this route are mainly adenoviruses 2 and 5 and rubella virus (142, 143). Dendritic cells have been shown to use macropinocytosis in antigen presentation, since this mechanism is useful in uptake of large fluid volumes and opsonized particles, more so than can be accommodated within clathrin-coated pits. This realization may explain the usefulness of this entry route for microorganisms and EVs. Exosomes, as defined by immunodetection of marker proteins, have been shown to be specifically and efficiently taken up and transported from oligodendrocytes to microglias by macropinocytosis (10). In addition, it was recently demonstrated that the active induction of macropinocytosis upon stimulation by surface epidermal growth factor receptor significantly enhances the cellular uptake of exosomes into target cells (144).

While it is thus clear that exosomes and other EVs exploit the same endocytic entry routes as animal viruses, it could be conjectured that EVs produced by particular cell types may select their target cells by specific receptors. Despite the added complexity that EVs are innately heterogeneous, viruses and EVs appear to share receptors for cell entry.

SHARED RECEPTORS FOR VIRUS AND EV ENTRY

Lectins

Accumulating evidence suggests that HIV and EVs both rely on lectins as target cell receptors (Fig. 7). Apart from T cells and macrophages, HIV can target myeloid dendritic cells via the receptor CD169/Siglec-1 (a lectin), which binds to the ganglioside 3 (GM3) present on the surface of virus particles (145). HIV capture by CD169 is enhanced upon DC maturation with lipopolysaccharide, and viral particles, rather than inserting their capsids into the cytoplasm, are protected from degradation in CD169+ virus-containing compartments. From there, they may later be released and disseminated to CD4+ T cells, a mechanism of DC-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection (146). Sialic acid binding immunoglobulin lectins are sialic acid binding molecules expressed on a variety of leukocytes and stromal cells, in particular by subcapsular sinus and medullary macrophages in lymph nodes and on marginal macrophages in the marginal zone of the spleen. In an elegant in vivo study using CD169 knockout mice as controls, CD169 was identified as a key mediator of B cell-secreted exosome capture by these macrophages (147). Although a possible role for GM3 was not studied, early proteomic studies identified GM3 on the surface of B cell exosomes (67). The intracellular fate of these exosomes and whether they follow a similar route as proposed for engulfed HIV particles (28) remain to be investigated. Apart from proteomic studies, classical biochemical techniques also revealed the presence of several glycan binding proteins. Apart from CD169, CD62, a C-type P-selectin, is present on the surface of platelet-derived EVs that bind to target cells via classical P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) (148). Of note, the latter study was actually one of the first to clearly describe the existence of different pathways for vesicle release.

FIG 7.

Apoptotic mimicry and receptor-mediated EV entry. (A) Tetraspanins and integrins. The Tspan8-CD49d (ITGα4β1) complex on exosomes possibly binds to VCAM-1 on target cells (84). In general, EVs could attach to the target cell via ITGα1β1, ICAM-1, or VCAM-1 (71). ICAM-1 on DC-derived exosomes could bind to LFA-1 (ITGαLβ2) on T cells/DCs and ITGαvβ3 on DCs (61, 72, 73). (B) Lectins. GM3 on B-cell-derived exosomes may bind to Siglec-1 for uptake by macrophages (67, 147). (C) Phosphatidylserine receptors. PtdSer is exposed on the outer leaflet of the exosomal membrane, and the Tam family of PtdSer receptors, which include but are not restricted to KIM-1, TIM-1, and TIM-4, mediates EV uptake. MFG-E8, enriched on exosomes, might mediate EV uptake by acting as a bridge between PtdSer and integrins or via Gas6 interactions (10, 176). (D) HSPG. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans act as internalizing receptors of cancer cell-derived EVs (152).

To escape the mucosal clearance system and reach its target cells, HIV-1 has evolved strategies to circumvent deleterious host factors. Galectin-1, a soluble lectin found in the underlayers of the epithelium, increases HIV-1 infectivity by accelerating its binding to susceptible cells. In its normal function, galectin-1 binds to glycans on the CD4 coreceptor of T cells to prevent autorecognition. However, when HIV is present, the galectin bridges the CD4 coreceptor and gp120 ligands, thus facilitating HIV infection of the T cell (149). There might also be a link between galectins and EV attachment. In a proteomic analysis, galectin-3 was associated with DC-derived exosomes (69); galectin-3 may also have adhesion properties (150). However, in a recent study, it was observed that galectin-5 functionality involved in the exosomal sorting pathway during rat reticulocyte maturation actually delayed uptake by macrophages (151).

Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a linear polysaccharide that occurs as a proteoglycan (HSPG) when HS chains are attached in close proximity to cell surface or extracellular matrix proteins. HSPGs were recently discovered as internalizing receptors of cancer cell-derived EVs with exosome-like characteristics (Fig. 7) (152). Prior to these studies, it was known that many enveloped viruses, notably herpesviruses, can enter cells by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and a cell membrane (153). Studies of the interaction of the fusion peptide domain of HIV gp41 with the surface of T lymphocytes showed that heparinase could block these interactions and cell entry (154). Likewise, if heparan sulfate is present on proteoglycans exposed at the cell surface, these molecules capture herpesviruses, facilitating interactions with coreceptors. For these viruses, it was observed that, depending on the nature of the interaction and the size of the heparan sulfate chain, a single chain might bind multiple viral ligands on a virion. For example, the mass of heparin sulfate chains on human HEp-2 cells averaged 105 kDa (155). This molecular mass corresponds roughly to 420 sugar residues per chain, or a length of almost 200 nm, which is larger than the diameter of many virions (like HIV) and EV subtypes. By using several cell mutants and enzymatic depletion, Christianson and colleagues provided the first genetic and biochemical evidence of a receptor function for HSPG in exosome uptake, which was dependent on intact HS (152). This was highly specific for the 2-O and N-sulfation groups. Enzymatic depletion of HS at the cell surface or pharmacological inhibition of endogenous proteoglycan biosynthesis significantly attenuated exosome uptake. Not yet defined are the structures on the surface of EVs that could bind to HSPGs, but speculations can be made. Due to their high negative charge, HS chains can bind to a great amount of proteins (156). For example, HSPGs at the cell membrane can activate adhesion mechanisms, via receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) or via presentation of chemokines, which can activate ITG complexes present on EVs. There is evidence that EVs incorporate RTKs, suggesting that EV adhesion and possibly uptake can be facilitated by interactions between RTKs and HSPG (157). Finally, while the specificity for particular subtypes of EVs was not studied, it is known that some viruses lack binding affinity for HSPG altogether. For example, EBV does not require HSPG for cell entry (158). Thus, the role of HS in EV targeting may depend highly on the EV (sub)type. Are there any common uptake pathways and molecules identified that mediate EV uptake and biology?

Apoptotic Mimicry by EVs

While EVs have the same membrane topology as the plasma membrane, many studies have revealed that cell-secreted exosomes contain phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) facing the extracellular environment (10, 35, 61, 159, 160). PtdSer is a ubiquitous membrane phospholipid that has a key role in initiating the removal of apoptotic bodies by phagocytosis (161) and participates in the clearance of viruses by macropinocytosis (162). In healthy cells, PtdSer is actively kept within the inner membrane leaflet such that its charged head faces the cytosol. Due to membrane dynamics, PtdSer may become exposed on the outer leaflet, but in healthy cells special enzymes maintain lipid asymmetry. In diseased cells, however, membrane integrity is compromised. In early apoptotic animal cells, PtdSer becomes exposed to the extracellular environment, serving as an “eat me” signal for professional phagocytic cells. Fitzner and colleagues tested the involvement of PtdSer in exosome internalization. Using liposomes that contained a mixture of phosphatidylcholine and PtdSer, those authors showed that uptake of exosomes by microglia was significantly reduced in the presence of PtdSer-containing liposomes (10). Importantly, in 2008 Zhang and colleagues showed that T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain proteins 1 and 4 (TIM-1 and TIM-4) can capture exosomes, though internalization and delivery of cargo were not studied (35). B-cell-derived exosomes express PtdSer and are taken up by TIM receptor-expressing monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) and pDCs (60). The observation that TIM receptors bind exosomes sparked interest in these molecules as entry receptors for enveloped viruses (Fig. 7).

Enveloped viruses cover their capsids in a lipid bilayer that is obtained during virus budding from either plasma or organelle membranes. Although enveloped viruses are more sensitive to harsh environmental conditions, acquisition of an envelope can be an advantageous strategy to (i) protect viral structural proteins from immune recognition and neutralizing antibodies, (ii) increase surface area, allowing optimal display of viral proteins for early steps of infection, and (iii) provide a mechanism for virus egress that does not lyse and kill infected cells. In addition, a more recently appreciated benefit is the incorporation of phospholipids into viral envelopes. Presentation of PtdSer on the outer leaflet of these membranes disguises viruses as apoptotic bodies, thereby confusing cells into engulfing virions through cell clearance mechanisms. This mechanism of enhanced virus entry is sometimes termed apoptotic mimicry (163). The first viral receptor identified that turned out to be a PtdSer receptor was hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 (HAVCR1), also known as kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and later as TIM-1, used by HAV for cellular entry (164). The cellular function of KIM-1 was believed to be as an epithelial cell adhesion molecule specifically upregulated in proximal renal tubular cells after injury (165). It was later discovered that KIM-1 serves as a specific PtdSer receptor, conferring a phagocytic phenotype to epithelial cells (166). Using a library of monoclonal antibodies against mouse peritoneal macrophages, it was observed that an antibody against TIM-4 strongly inhibited the PtdSer-dependent engulfment of apoptotic cells.

Since the discovery of TIM-1 and TIM-4 as PtdSer receptors, additional family members, such as TAM, were identified that support cell entry of many enveloped viruses (33, 167–171). For dengue virus (DV) infection, TAM-mediated infection relies on indirect DV recognition, in which growth arrest-specific 6 (Gas6), a known TAM ligand, acts as a bridging molecule. This dual mode of virus recognition by TIM and TAM receptors reveals a clear example of how viruses usurp the apoptotic cell clearance pathway for infectious entry. Again, a similarity between viruses, EVs, and cellular fragments becomes apparent. The interaction between phosphatidylserine, Gas6, and Axl was originally shown to be a molecular mechanism through which phagocytes recognize phosphatidylserine exposed on dead cells (172). However, it is now known that Axl/Gas6, as well as other phosphatidylserine receptors, facilitates entry of dengue, West Nile, and Ebola viruses (173). Viral envelope PtdSer exposure is a viral entry mechanism generalized to many families of viruses, and apart from Axl/Gas6, various other molecules are known to recognize PtdSer. The effects of Axl/GAS6 on virus binding and entry have not been comprehensively evaluated and compared (174), including the PtdSer-bridging molecule milk fat globule EGF factor 8 protein (MFG-E8), also known as lactadherin. MFG-E8 was discovered to act as a bridge by binding to PtdSer on apoptotic cells and to the integrins αVβ3 and αVβ5 on phagocytes (175). While the evidence for the GAS6 interaction with exosomes and EVs is not overwhelming, in most, if not all proteomic studies MFG-E8 is identified (ExoCarta), suggesting that this molecule is an attractive candidate for mediating EV uptake (176). However, in recent studies of viral infection efficiency, it was found that MFG-E8 can increase the infectivity of PtdSer-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors by 5- to 10-fold, much less than mediation by Gas6 (200-fold), although this may depend on the specific setting (174). In sum, recent advances in the molecular mechanisms of viral entry yield another physiological link between viruses and EVs (Fig. 7).

PERSPECTIVES

While it is clear that designated pathways exist for EV entry into target cells, we are only at the beginning of understanding the complexities involved. Major questions remain, including how many entry-capable EV subtypes there are and the extent to which they use common or diverse, EV-specific entry routes, as seen with viruses. Are all cells “partially” susceptible to EV-mediated communication? Is signaling mainly local, or could EVs function systemically, as suggested by studies of tumor-bearing mice (14, 177, 178)? Research into the biodistribution of EVs has revealed that some selectivity may exist (10, 147), but many details remain unknown. There are reasons to be optimistic that specific pathways will be discovered. In recent years, accumulating evidence suggests that the biogenesis and release of exosomes and other EVs is tightly regulated, although the molecular details need further clarification. Moreover, as many reports describe, EV composition is not uniform, in particular that of EVs found in biological fluids such as plasma, as recently described after high-resolution electron microscopy (179). New high-throughput techniques, currently under development, will provide more insight into their heterogeneity and details on their molecular composition, which will be important to discern the physiological role of EVs in vivo.

We have not discussed in detail the fate of EVs once internalized by recipient cells. More precisely, the intercellular destination of EV cargo upon cell entry is heavily understudied. Presumably, EVs that fuse with the PM deliver their content directly into the cytosol. While EVs carry diverse cargo, RNA molecules have been among the most studied. In terms of functional RNA delivery, one might wonder how efficient such a mechanism could be. Would these RNAs not be attacked by nucleases, or are they protected, e.g., by surrounding proteins, in the EV and upon delivery? And could these RNAs and their associated proteins easily incorporate into recipient cell machinery for translation (mRNA) or inhibition (miRNA)? Similar questions could be asked of other cargoes.

While there is some evidence that EVs and exosomes are endocytosed and end up in internal compartments, whether these can escape endosomes by fusion with the delimiting membrane, as is required for viruses, is unknown. For certain viruses, the pH environment provides a cue for conformational changes in glycoproteins initiating fusion. The low pH of endosomes triggers conformational changes in the envelope proteins of HCV, which causes the HCV viral genome to get released into the cytosol. That the acidic environment of the endosome is required for these conformational changes was confirmed by studies using endosome acidification inhibitors. It may be interesting to know whether such inhibitors would also affect EV-mediated functional RNA transfer.

Perhaps the most important message to emphasize is the synergism of virus and EV research. The hard-won details of viral fusogenic processes will be an important Rosetta stone to help us decipher mechanisms of EV docking and fusion. Similarly, EV-related discoveries may give fresh insights into virus-host interactions. Witness, for example, the case of the TIM receptors, which were first identified as putative exosome receptors but have now been shown to act as key viral receptors. As new results come in, we may very well find that viruses and EVs share more compelling similarities than we are now able to comprehend.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Association (13-02-401) and the Dutch Cancer Society KWF (VU2012-5510) awarded to D.M.P.

Biographies

Helena M. van Dongen is a medical student at the VU Medical Center (VUmc) Amsterdam and a research intern at Exosomes Research Group at the Pathology Department of VUmc and Cancer Center Amsterdam, under the supervision of D. M. Pegtel. Her research focuses on extracellular vesicles and on biomarker discovery concerning Epstein-Barr virus antibody profiling in systemic lupus erythematosus. She is interested in oncogenesis and autoimmunity related to viruses and virus-infected cell-derived exosomes.

Niala Masoumi is a Ph.D. candidate at the VU Medical Center Amsterdam, Exosomes Research Group, in the Pathology Department. The focus of her Ph.D. project is the role of EBV-modified exosomes and their content, especially small RNAs, in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. She obtained her M.Sc. and Ing. titles at Utrecht University, The Netherlands, on the subjects of cancer genomics and developmental biology and on molecular biology, respectively. She has worked on multiple molecular research projects, as an intern and research technician, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, RIVM, The Netherlands, University Medical Center Utrecht, and Hubrecht Research Institute.

Kenneth W. Witwer is an Assistant Professor of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology and Neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. His research focuses on extracellular vesicles and RNA, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic modulation of innate and intrinsic defenses. Dr. Witwer trained at Penn State University and at Johns Hopkins University. He is an active member of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and is pursuing several funded research projects related to exosomes and HIV infection.

Dirk M. Pegtel is a P.I. at the Department of Pathology at the VU University Medical Center (VUmc) in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He obtained his Ph.D. degree from Tufts University (Boston, MA, USA), studying Epstein-Barr virus infection, and performed postdoctoral training in cell biology at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. For his original work on viral microRNA transport via exosomes, he was awarded the Bijerinck Premium from the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences. His research includes basic principles on cell-cell communication via extracellular vesicles and exosomes and the development of liquid biopsy approaches for cancer diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wurdinger T, Gatson NN, Balaj L, Kaur B, Breakefield XO, Pegtel DM. 2012. Extracellular vesicles and their convergence with viral pathways. Adv Virol 2012:767694. doi: 10.1155/2012/767694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grove J, Marsh M. 2011. The cell biology of receptor-mediated virus entry. J Cell Biol 195:1071–1082. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhill C. 2013. Hepatitis: new route of HCV transmission. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10:504. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofer U. 2013. Viral pathogenesis: cloak and dagger. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:360. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meckes DG. 2015. Exosomal communication goes viral. J Virol 89:5200–5203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02470-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. 2014. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol 14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MAJ, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, de Gruijl TD, Würdinger T, Middeldorp JM. 2010. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:6328–6333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narayanan A, Iordanskiy S, Das R, Van Duyne R, Santos S, Jaworski E, Guendel I, Sampey G, Dalby E, Iglesias-Ussel M, Popratiloff A, Hakami R, Kehn-Hall K, Young M, Subra C, Gilbert C, Bailey C, Romerio F, Kashanchi F. 2013. Exosomes derived from HIV-1-infected cells contain trans-activation response element RNA. J Biol Chem 288:20014–20033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.438895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai CP, Kim EY, Badr CE, Weissleder R, Mempel TR, Tannous BA, Breakefield XO. 2015. Visualization and tracking of tumour extracellular vesicle delivery and RNA translation using multiplexed reporters. Nat Commun 6:7029. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzner D, Schnaars M, van Rossum D, Krishnamoorthy G, Dibaj P, Bakhti M, Regen T, Hanisch U-K, Simons M. 2011. Selective transfer of exosomes from oligodendrocytes to microglia by macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci 124:447–458. doi: 10.1242/jcs.074088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen T-L, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Jørgen Labori K, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. 2015. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 527:329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frühbeis C, Fröhlich D, Kuo WP, Amphornrat J, Thilemann S, Saab AS, Kirchhoff F, Möbius W, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Schneider A, Simons M, Klugmann M, Trotter J, Krämer-Albers EM. 2013. Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS Biol 11:e1001604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridder K, Sevko A, Heide J, Dams M, Rupp A-K, Macas J, Starmann J, Tjwa M, Plate KH, Sültmann H, Altevogt P, Umansky V, Momma S. 2015. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of functional RNA in the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology 4:e1008371. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1008371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zomer A, Maynard C, Verweij FJ, Kamermans A, Schäfer R, Beerling E, Schiffelers RM, de Wit E, Berenguer J, Ellenbroek SIJ, Wurdinger T, Pegtel DM, van Rheenen J. 2015. In vivo imaging reveals extracellular vesicle-mediated phenocopying of metastatic behavior. Cell 161:1046–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Andaloussi S, Mäger I, Breakefield XO, Wood MJA. 2013. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:347–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. 2013. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. 2011. Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic 12:1659–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simons M, Raposo G. 2009. Exosomes: vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. 2009. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]