Abstract

Persisters are a small fraction of drug-tolerant bacteria without any genotype variations. Their existence in many life-threatening infectious diseases presents a major challenge to antibiotic therapy. Persistence is highly related to toxin–antitoxin modules. HipA (high persistence A) was the first toxin found to contribute to Escherichia coli persistence. In this study, we used structure-based virtual screening for HipA inhibitors discovery and identified several novel inhibitors of HipA that remarkably reduced E. coli persistence. The most potent one decreased the persister fraction by more than five-fold with an in vitroKD of 270 ± 90 nM and an ex vivo EC50 of 46 ± 2 and 28 ± 1 μM for ampicillin and kanamycin screening, respectively. These findings demonstrated that inhibition of toxin can reduce bacterial persistence independent of the antibiotics used and provided a framework for persistence treatment by interfering with the toxin–antitoxin modules.

Keywords: Persistence, toxin-antitoxin (TA) module, HipA (high persistence A), drug discovery

In the whole world, about 15 million in 57 million annual deaths are caused by infectious diseases.1 Drug tolerance is the major contributor to the therapeutic failure of antibiotics. Bacterial persistence is one of the most important mechanisms of drug tolerance and increases the risk of multidrug resistance and extensive drug resistance. It plays particularly prominent roles in many chronic infectious diseases, such as syphilis (Treponema pallidum), Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi), and tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis).2 Persisters were first described in 1944 by J. W. Bigger, who discovered that a small subpopulation of Staphylococcus aureus (about one in 100,000 cells) survived when exposed to penicillin.3 These surviving bacteria, which are genetically identical to the antibiotic-sensitive population, are highly tolerant to antibiotics, yet their descendants show the same drug sensitivity as the original cultures.4

The multidrug tolerant persisters exhibit heterogeneous growth4 that is highly related to type II toxin–antitoxin (TA) modules.5−7 A typical type II TA module comprises a large toxin protein and a corresponding small antitoxin protein, both of which are encoded on a single operon. Toxins inhibit DNA replication, cleave mRNA, inhibit translation, thereby arresting cell growth and conferring multidrug tolerance.8−10 Antitoxins neutralize the toxicity of toxins by forming a complex with them. Furthermore, both antitoxins and antitoxin–toxin complexes can bind to the regulatory region of the operons, inhibiting their transcriptions.

TA modules are redundant and universal in bacteria with about 88 in M. Tuberculosis and 37 in E. coli. In E. coli, there are three TA module families. Two of them, MazEF and RelBE, have the toxin proteins of RNA endonuclease.11 Single knockout of the RNA endonucleases shows little effect on persister survival. Only when more than five of them are knocked out, the persister survival decreases significantly.12 HipBA is a special TA module with the HipA toxin being a serine kinase.13 It is one of only a few molecules that are validated tolerance-related factors.7,10 HipA was first discovered by Moyed et al., who isolated a high persistence mutant, HipA7, which presented a much higher persister fraction, nearly 10–2.14 Ectopic overexpression of HipA increases the persister fraction by 10,000-fold.8 Excessive existence of HipA toxin were demonstrated to be able to phosphorylate the elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu)13 and/or GltX:tRNAGlu,15 inhibit the translation of proteins, or activate the (p)ppGpp stringent response,16,17 thus making the normal cells jump to persistence state.

The important role that toxins play in persister formation makes the toxins potential targets for the development of drugs for the treatment of multidrug tolerant persisters. To our knowledge, no inhibitors of HipA or other toxins have been reported until now. In this study, we used computational based virtual screening and in vitro/ex vivo experimental tests to discover novel inhibitors of toxin HipA that can reduce E. coli persistence.

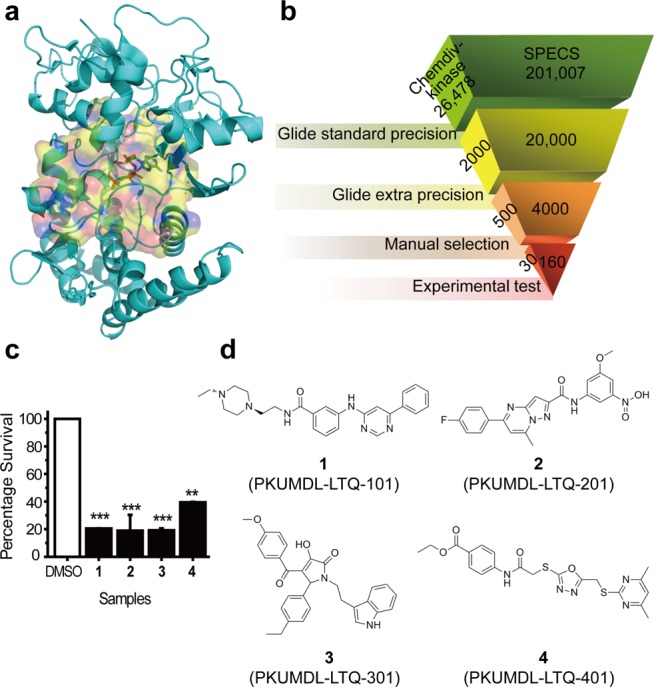

In 2009, Schumacher et al. solved the crystal structure of HipA D309Q mutant with an ATP analogue in the ATP binding pocket and a substrate peptide of EF-Tu (PDB code: 3FBR)13 (Figure 1a). To discover HipA inhibitors, we used this structure with the residue 309 mutated back to Asp to carry out structure-based virtual screening (see details in Supporting Information). The crystal structure of HipA S150A mutant was not used because the residues 133–155 in the hydrophobic core and residues 185–193 in the activation loop are absent.18 Virtual screening was conducted using two compound libraries, the Chemdiv kinase (26,478 kinase inhibitors and analogues) and the SPECS compounds libraries (November 2009 version, 201,007 compounds), using the molecular docking program Glide (Schrödinger LLC, New York, NY). The standard precision mode of Glide was used first, followed by the extra precision mode (see details in Supporting Information). After computational and manual selection, 30 compounds from the Chemdiv kinase library and 160 compounds from the SPECS compound database were purchased for subsequent tests (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) ATP binding pocket (surface representation) of HipA(D309Q) (PDB code: 3FBR) and ATP analogue (stick format) inside it. (b) The virtual screening scheme used to identify candidate E. coli HipA inhibitors. (c) The percentage survivals of the four potent compounds (black bars) compared to the DMSO control (white bar). *P < 0.5, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three replicates. (d) The chemical structures of the four novel HipA inhibitors.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) tests were performed to measure the direct binding strengths of the 190 selected molecules to HipA. As HipA is toxic to E. coli and difficult to express, while the HipA D309Q mutant is not toxic and still binds ATP with an affinity comparable to the wild type,8,13,19 we expressed the D309Q mutant protein (referred to as HipA(D309Q) below) for SPR tests. The purified protein with the purity of >90% was verified to be in a folded state by circular dichroism and bound ATP with a dissociation constant (KD) of 43 ± 2 μM (Supplementary Figure S1), consistent with Schumacher’s result.13 HipA(D309Q) was subsequently used for SPR primary tests, which identified 30 compounds that bound to it (see details in Supporting Information).

The ex vivo antipersistence effects of the 30 compounds, which showed binding abilities to HipA(D309Q) in SPR assay, were further tested by treating E. coli cultures (with DMSO as a control), and then exposed the cultures to ampicillin, quantifying the surviving colonies. Colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) of the cultures without exposing to ampicillin were also quantified for the calculation of persister fraction (see details in Supporting Information). The results showed that the persister fraction of control is about 10–4 (Supplementary Figure S2a), which is consistent with a previous study.7 Twenty compounds showed significant inhibition activities at the concentration of 250 μM (Supplementary Figure S2a), while six of them also showed cell cytotoxicity at this concentration (Supplementary Figure S2b). In all the 14 molecules that significantly reduced E. coli persistence without cytotoxicity, four compounds, 1, 2, 3, and 4 (shortened for PKUMDL-LTQ-101, PKUMDL-LTQ-201, PKUMDL-LTQ-301, and PKUMDL-LTQ-401, respectively) exhibited the most potent antipersistence effects, which were further analyzed.

Compared to the control with the persister fraction setting as 100%, compounds 1, 2, and 3 decreased the persister fraction by about five-fold at the concentration of 250 μM (p < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t test), and compound 4 decreased the fraction by two- to three-fold (p < 0.01) (Figure 1c). Though these four compounds decreased the persister fraction by less than 1 order of magnitude because of the low basic persister fraction of E. coli, the antipersistence activities of these compounds are comparable with five RNA nuclease knockouts.12 The chemical structures of the four compounds are shown in Figure 1d. All the four compounds passed the PAINS-remover, which filters out the compounds with substructural features that are pan-active in many biochemical assays.20

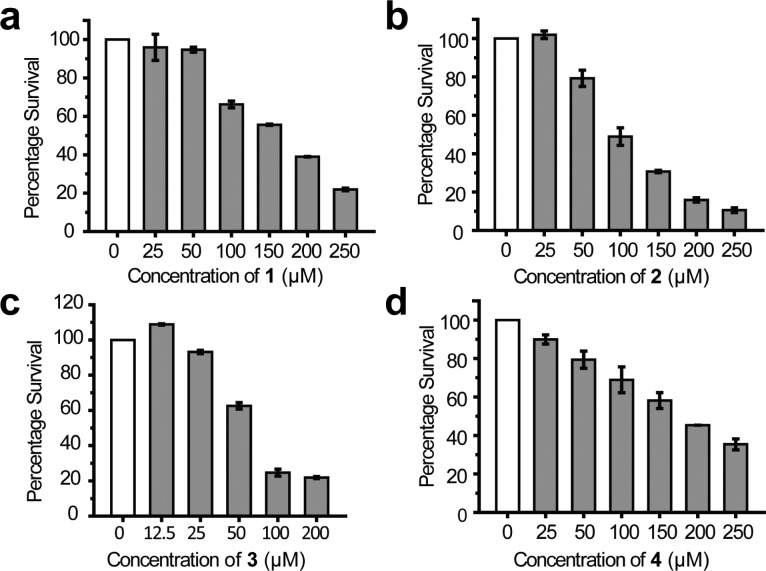

The antipersistence effects of the four compounds were further validated by quantifying their half effective concentrations (EC50). All the four compounds reduced the persister fraction in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2). Compound 3 has the lowest EC50 (46 ± 2 μM; see Figure 2c and Table 1), while the EC50s for the other three compounds ranged from 84 (2) to 126 μM (1) (Figure 2 and Table 1). To confirm that the antipersistence effects of the compounds were caused by inhibiting toxin HipA, we performed the persister assay on hipA knockout strain (ΔhipA, purchased from NBRP-E. coli at NIG). As expected, treating ΔhipA E. coli with ampicillin decreased the persister fraction from 1.35 × 10–4 to 3.61 × 10–5 (Supplementary Figure S3a). Moreover, the most potent inhibitor of HipA, compound 3, no longer decreased the persister fraction of ΔhipA strain even at the concentration of 200 μM (Supplementary Figure S3b).

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent reduction of E. coli persisters by compounds 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent replicates.

Table 1. Novel HipA Inhibitors Discovered with Corresponding KD, EC50s, and Docking Scores.

| compd | database ID | KD (μM) | EC50 (Amp)a (μM) | EC50 (Kan)b (μM) | score (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F725–1337 | 54 ± 2 | 126 ± 9 | 111 ± 1 | –10.17 |

| 2 | AK-968/37053102 | 43 ± 3 | 84 ± 5 | 101 ± 4 | –9.817 |

| 3 | AQ-149/43243674 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | 46 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 | –10.31 |

| 4 | AF-399/41182128 | 35 ± 2 | 116 ± 10 | 43 ± 3 | –9.29 |

EC50(Amp) is the EC50 screened by 100 μg/mL ampicillin.

EC50(Kan) is the EC50 screened by 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three replicates.

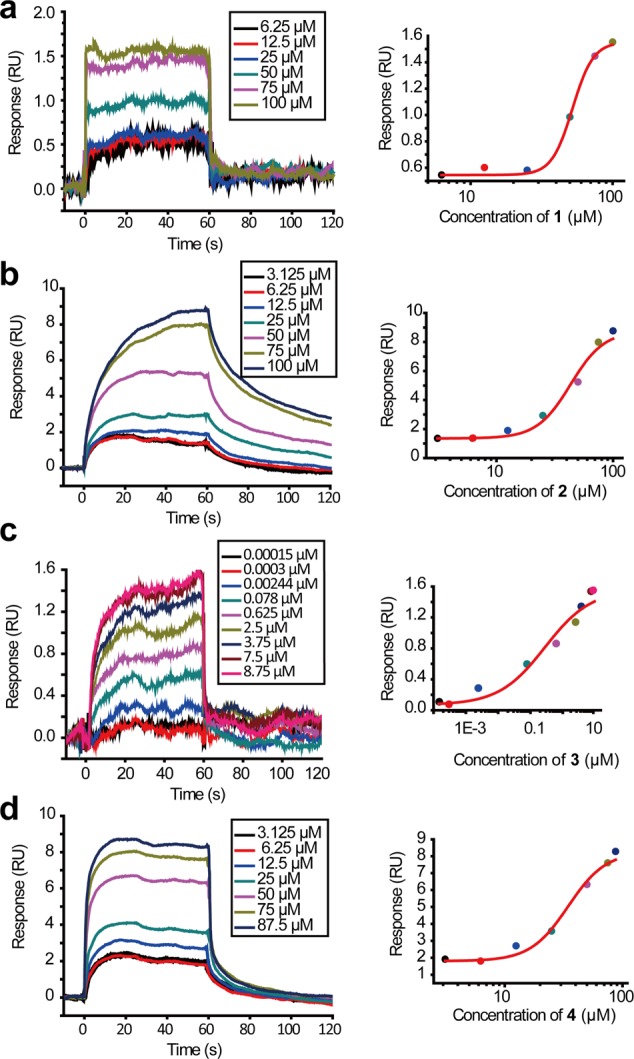

We then used SPR to quantitatively measure the direct binding affinities of the four compounds to HipA. All the four compounds showed dose-dependent binding responses to HipA (Figure 3). The kinetic pattern for HipA binding of compound 1 was typical fast-on and fast-off, while the binding curves of compound 2 showed a slow-on, slow-off pattern. The kinetic pattern for HipA binding by compounds 3 and 4 was slow-on, fast-off. Compound 3 also exhibited the lowest KD (0.27 ± 0.09 μM) (Figure 3c and Table 1), while the KD for the other three compounds was 54 ± 2 μM for 1, 43 ± 3 μM for 2, and 35 ± 2 μM for 4 (Figure 3 and Table 1). The in vitro binding affinities correlated well with the ex vivo antipersistence effects. These results validated that the four compounds reduced the bacterial persisters by binding to HipA.

Figure 3.

Left panel: SPR dose–response curves of compounds 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d). Right panel: data at equilibrium fitted with the Hill model.

We also modeled the binding mode of the four compounds to HipA using the molecular docking program Glide. The docking scores of the compounds are in accordance to their EC50s, especially of compound 3, which has the lowest predicted docking score (−10.31 kcal/mol) and the lowest EC50 and KD, too (Table 1). The complex model shows that compound 3 interacts with HipA by forming: (a) π–π stacking with residues Phe236 and Tyr331; (b) hydrophobic interactions with residues Val98, Ile179, Lys181, Val233, Phe236, Gln252, and Tyr331; (c) hydrogen bonds with Gln257, Lys313, Ser316, Tyr331, and Asp332 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Binding mode of compound 3 (stick) to HipA (cartoon) predicted by molecular docking. The residues that interact with compound 3 are highlighted in line format. The hydrogen bonds are represented in yellow dashes.

Theoretically, inhibition of HipA toxin has no connection with antibiotic types. So, we changed the antibiotic from ampicillin, an antibiotic blocking bacterial cell wall synthesis, to kanamycin, an antibiotic inhibiting bacterial protein translation. Assays with kanamycin showed that compound 3 decreased the persister fraction by more than 1 order of magnitude with an EC50 of 28 ± 1 μM (Figure 5c and Table 1). Compound 4 showed a better EC50 value of 43 ± 3 μM when screened in the presence of kanamycin (Figure 5d and Table 1). Consistent with the former results, compounds 1 and 2 also reduced the persisters by about five-fold, while 4 decreased the persisters by three- to four-fold (Figure 5). These results confirmed that the inhibitors against HipA can dramatically decrease the persisters and that it is independent of the antibiotic stress conditions.

Figure 5.

HipA inhibitors 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d) reduced E. coli persisters in the presence of kanamycin in a dose-dependent manner. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three replicates.

In the present study, we successfully identified several novel inhibitors of HipA toxin by using computational structure-based virtual screening and in vitro and ex vivo experimental tests. The most potent inhibitor, 3, bound to HipA with a dissociation constant of 270 nM and inhibited E. coli persistence with EC50 values of 46 and 28 μM when screened in the presence of ampicillin and kanamycin, respectively. Zhang and colleagues21 used similar strategy and discovered inhibitors of sortase A, which protect mice from S. aureus bacteremia without slowing down the bacterial growth. Until now, no inhibitors of any toxins have been developed. This work for the first time demonstrates that inhibition of toxin in toxin–antitoxin modules can interfere with persister formation and provides a new strategy to treat bacterial persistence.

Neither the four compounds described in this letter nor their structure analogues were reported to inhibit HipA toxin or bacterial persistence before. The structure of compound 3 has been shown to inhibit Trypanosoma brucei leucyl-tRNA synthetase with an IC50 of >50 μM.22 Its analogues have been reported to inhibit GluN2C23 and Pim124 but no bacterial targets. No biological activities of the other three compounds have been reported. Thus, the compounds identified in the present work provide novel scaffolds for further optimization.

Allison and colleagues have proposed a strategy by providing the bacteria with saccharides that change persisters to normal cells by stimulating the metabolism of persisters.25,26 However, their strategy is only effective for aminoglycoside antibiotics, and the sugar concentrations required to evoke a response in persisters are in millimolar range. Our strategy to inhibit HipA toxin is independent of the antibiotic types, which is more generally applicable. Other than sugars, brominated furanones, which were primarily found to inhibit quorum sensing, present the ability to sensitize persister cells to antibiotics27−29 with the effective concentration to dramatically decrease the persister fraction being in the micromolar range. However, the targets of brominated furanones are not clear. The compounds by inhibiting toxin HipA identified in this study can decrease the persister fraction by more than five-fold and showed good antipersistence activities.

In summary, we present a new strategy toward fighting multidrug tolerant persisters by targeting the toxin HipA in toxin–antitoxin system. We also demonstrated that the novel inhibitors of toxin HipA identified in the present work reduced the bacterial persistence independent of the antibiotic types used. Besides HipA, other toxins can also be targeted for antipersistence drug development.

Acknowledgments

We thank NBRP-E. coli at NIG for providing us the hipA knockout strain.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00420.

Materials; methods for molecular cloning, protein purification; persister assays; virtual screening; SPR assays; supplementary results (PDF)

Author Contributions

L.L., J.P., T.L., and N.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. T.L. performed virtual screening and all the experimental studies. H.L. participated in purification of HipA(D309Q). T.L., N.Y., J.P., and L.L. analyzed the data. T.L., J.P., and L.L. wrote the paper.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012AA020308, 2012AA020301, and 2015CB910300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81273436).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Morens D. M.; Folkers G. K.; Fauci A. S. The Challenge of Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases. Nature 2004, 430, 242–249. 10.1038/nature02759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. Persister Cells, Dormancy and Infectious Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 48–56. 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigger J. W. Treatment of Staphylococcal Infections with Penicillin. Lancet 1944, 244, 497–500. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)74210-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban N. Q.; Merrin J.; Chait R.; Kowalik L.; Leibler S. Bacterial Persistence as a Phenotypic Switch. Science 2004, 305, 1622–1625. 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A.; Dewan P. C.; Siddique S. A.; Varadarajan R. Mazf-Induced Growth Inhibition and Persister Generation in Escherichia Coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 4191–4205. 10.1074/jbc.M113.510511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton J. P.; Mulvey M. A. Toxin-Antitoxin Systems Are Important for Niche-Specific Colonization and Stress Resistance of Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002954. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren I.; Shah D.; Spoering A.; Kaldalu N.; Lewis K. Specialized Persister Cells and the Mechanism of Multidrug Tolerance in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 8172–8180. 10.1128/JB.186.24.8172-8180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch S. B.; Hill T. M. Ectopic Overexpression of Wild-Type and Mutant Hipa Genes in Escherichia Coli: Effects on Macromolecular Synthesis and Persister Formation. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 3826–3836. 10.1128/JB.01740-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E.; Gerdes K. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Bacterial Persisters. Cell 2014, 157, 539–548. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M. A.; Balani P.; Min J.; Chinnam N. B.; Hansen S.; Vulic M.; Lewis K.; Brennan R. G. Hipba-Promoter Structures Reveal the Basis of Heritable Multidrug Tolerance. Nature 2015, 524, 59. 10.1038/nature14662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K.; Maisonneuve E. Bacterial Persistence and Toxin-Antitoxin Loci. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 103–123. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E.; Shakespeare L. J.; Jorgensen M. G.; Gerdes K. Bacterial Persistence by Rna Endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 13206–13211. 10.1073/pnas.1100186108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Schumacher M. A.; Piro K. M.; Xu W.; Hansen S.; Lewis K.; Brennan R. G. Molecular Mechanisms of Hipa-Mediated Multidrug Tolerance and Its Neutralization by Hipb. Science 2009, 323, 396–401. 10.1126/science.1163806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyed H. S.; Bertrand K. P. Hipa, a Newly Recognized Gene of Escherichia Coli K-12 That Affects Frequency of Persistence after Inhibition of Murein Synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 155, 768–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E.; Castro-Camargo M.; Gerdes K. (P)Ppgpp Controls Bacterial Persistence by Stochastic Induction of Toxin-Antitoxin Activity. Cell 2013, 154, 1140–1150. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokinsky G.; Baidoo E. E.; Akella S.; Burd H.; Weaver D.; Alonso-Gutierrez J.; Garcia-Martin H.; Lee T. S.; Keasling J. D. Hipa-Triggered Growth Arrest and Beta-Lactam Tolerance in Escherichia Coli Is Mediated by Rela-Dependent Ppgpp Synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 3173. 10.1128/JB.02210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch S. B.; Henderson T. A.; Hill T. M. Characterization of the Hipa7 Allele of Escherichia Coli and Evidence That High Persistence Is Governed by (P)Ppgpp Synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 1199–1213. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M. A.; Min J.; Link T. M.; Guan Z.; Xu W.; Ahn Y. H.; Soderblom E. J.; Kurie J. M.; Evdokimov A.; Moseley M. A.; Lewis K.; Brennan R. G. Role of Unusual P Loop Ejection and Autophosphorylation in Hipa-Mediated Persistence and Multidrug Tolerance. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 518–525. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. G.; Bourbeau M. P.; Wohlhieter G. E.; Bartberger M. D.; Michelsen K.; Hungate R.; Gadwood R. C.; Gaston R. D.; Evans B.; Mann L. W.; Matison M. E.; Schneider S.; Huang X.; Yu D.; Andrews P. S.; Reichelt A.; Long A. M.; Yakowec P.; Yang E. Y.; Lee T. A.; Oliner J. D. Discovery and Optimization of Chromenotriazolopyrimidines as Potent Inhibitors of the Mouse Double Minute 2-Tumor Protein 53 Protein-Protein Interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7044–7053. 10.1021/jm900681h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J. B.; Holloway G. A. New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (Pains) from Screening Libraries and for Their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2719–2740. 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Liu H.; Zhu K.; Gong S.; Dramsi S.; Wang Y. T.; Li J.; Chen F.; Zhang R.; Zhou L.; Lan L.; Jiang H.; Schneewind O.; Luo C.; Yang C. G. Antiinfective Therapy with a Small Molecule Inhibitor of Staphylococcus Aureus Sortase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 13517–13522. 10.1073/pnas.1408601111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Wang Q.; Meng Q.; Ding D.; Yang H.; Gao G.; Li D.; Zhu W.; Zhou H. Identification of Trypanosoma Brucei Leucyl-Trna Synthetase Inhibitors by Pharmacophore- and Docking-Based Virtual Screening and Synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 1240–1250. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S. S.; Khatri A.; Garnier-Amblard E. C.; Mullasseril P.; Kurtkaya N. L.; Gyoneva S.; Hansen K. B.; Traynelis S. F.; Liotta D. C. Design, Synthesis, and Structure-Activity Relationship of a Novel Series of Glun2c-Selective Potentiators. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2334–2356. 10.1021/jm401695d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olla S.; Manetti F.; Crespan E.; Maga G.; Angelucci A.; Schenone S.; Bologna M.; Botta M. Indolyl-Pyrrolone as a New Scaffold for Pim1 Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1512–1516. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison K. R.; Brynildsen M. P.; Collins J. J. Metabolite-Enabled Eradication of Bacterial Persisters by Aminoglycosides. Nature 2011, 473, 216–220. 10.1038/nature10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega N. M.; Allison K. R.; Khalil A. S.; Collins J. J. Signaling-Mediated Bacterial Persister Formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 431–433. 10.1038/nchembio.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.; Bahar A. A.; Syed H.; Ren D. Reverting Antibiotic Tolerance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Pao1 Persister Cells by (Z)-4-Bromo-5-(Bromomethylene)-3-Methylfuran-2(5h)-One. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45778. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.; Song F.; Ren D. Controlling Persister Cells of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Pdo300 by (Z)-4-Bromo-5-(Bromomethylene)-3-Methylfuran-2(5h)-One. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 4648–4651. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.; Ren D. Structural Effects on Persister Control by Brominated Furanones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 6559–6562. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.