Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a potent growth-signaling lipid that has been implicated in cancer progression, inflammation, sickle cell disease, and fibrosis. Two sphingosine kinases (SphK1 and 2) are the source of S1P; thus, inhibitors of the SphKs have potential as targeted cancer therapies and will help to clarify the roles of S1P and the SphKs in other hyperproliferative diseases. Recently, we reported a series of amidine-based inhibitors with high selectivity for SphK1 and potency in the nanomolar range. However, these inhibitors display a short half-life. With the goal of increasing metabolic stability and maintaining efficacy, we designed an analogous series of molecules containing oxadiazole moieties. Generation of a library of molecules resulted in the identification of the most selective inhibitor of SphK1 reported to date (705-fold selectivity over SphK2), and we found that potency and selectivity vary significantly depending on the particular oxadiazole isomer employed. The best inhibitors were subjected to in silico molecular dynamics docking analysis, which revealed key insights into the binding of amidine-based inhibitors by SphK1. Herein, the design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and docking analysis of these molecules are described.

Keywords: Sphingosine 1-phosphate, sphingosine kinase, cancer, inhibitor, oxadiazoles

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a potent signaling lipid that acts on five membrane-bound receptors (S1P1–5)1 and various intracellular targets.2 S1P has been shown to regulate a host of processes that affect the growth and fate of cells,3 and aberrant S1P signaling has been linked to numerous diseases including cancer,2,4 asthma,5 fibrosis,6 and sickle cell disease.7 Cellular synthesis of S1P is exclusively dependent on the action of two sphingosine kinases (SphK1 and 2) that directly phosphorylate sphingosine (Sph).3 As the sole sources of cellular S1P, the SphKs influence cell survival8,9 and have been identified as targets of interest in pharmacology and the pharmaceutical industry.4,10 Therefore, SphK inhibitors, by affecting S1P levels, have therapeutic potential and are necessary to clarify the many roles of S1P and each SphK in physiology and disease.10−12

S1P signaling is complex, and the roles of SphK1 and 2 in various pathways differ significantly. These differences are due, in large part, to subcellular compartmentalization; SphK2 possesses an N-terminal nuclear localization sequence not present in SphK1.13 Indeed, SphK2 is located primarily in the nucleus and other organelles and may influence gene expression through S1P-dependent inhibition of histone deacetylase 1 and 2 (HDAC1 and 2).14 Additionally, S1P produced by SphK2 in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria has the effect of stimulating apoptosis.15 In contrast, SphK1 is located primarily in the cytosol, and SphK1-derived S1P generally elicits prosurvival and proliferative effects through interactions with S1P1–5. Upon phosphorylation by the extracellular-regulated kinases, SphK1 is activated and translocated to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane.16 Then, in an inside-out signaling mechanism, S1P is shuttled outside the cell by the membrane-spanning spinster 2 protein (or by members of the ABC transport family), where it may bind with any of the G protein-coupled S1P1–5. Agonism at these receptors initiates a cascade of signaling events affecting growth, motility, immune cell trafficking, metastasis, and angiogenesis.12

Because of the complexity of S1P signaling, a large and diverse set of pharmacological tools is necessary to probe the underlying physiological pathways and conclusively validate both SphK1 and 2 in different disease models. Small-molecule SphK inhibitors are an important example of such a tool, and ideally should have the following characteristics: single-digit nanomolar potency, at least 100-fold selectivity for either of the SphK isoforms, and high metabolic stability.10 Currently, no single molecule fulfills each criterion simultaneously, but a new generation of inhibitors is nearing this mark. In particular, recent efforts to improve our highly potent (but unstable) amidine-based inhibitors have yielded a class of very effective guanidine-based, oxadiazole-containing molecules.17−19 These compounds are the most potent and selective inhibitors that elicit prolonged shifts in blood S1P concentrations; the ability to lower or raise blood S1P levels is an important biomarker for inhibition of SphK1 or 2, respectively.20

To further improve SphK inhibitors, particularly regarding potency, it is necessary to continue to probe the Sph-binding pockets of SphK1 and 2 with structurally diverse sets of molecules. To this end, we have developed and characterized a small library of molecules combining an amidine headgroup with various oxadiazole linkers, elaborating on our earlier studies.21,22 Herein, we report an inhibitor with double-digit nanomolar potency and 705-fold selectivity for SphK1 over SphK2. Additionally, we reveal two key insights into the structure–activity relationships governing SphK1 inhibition, namely, that potency and selectivity are greatly affected by oxadiazole subtypes and alkyl tail positioning.

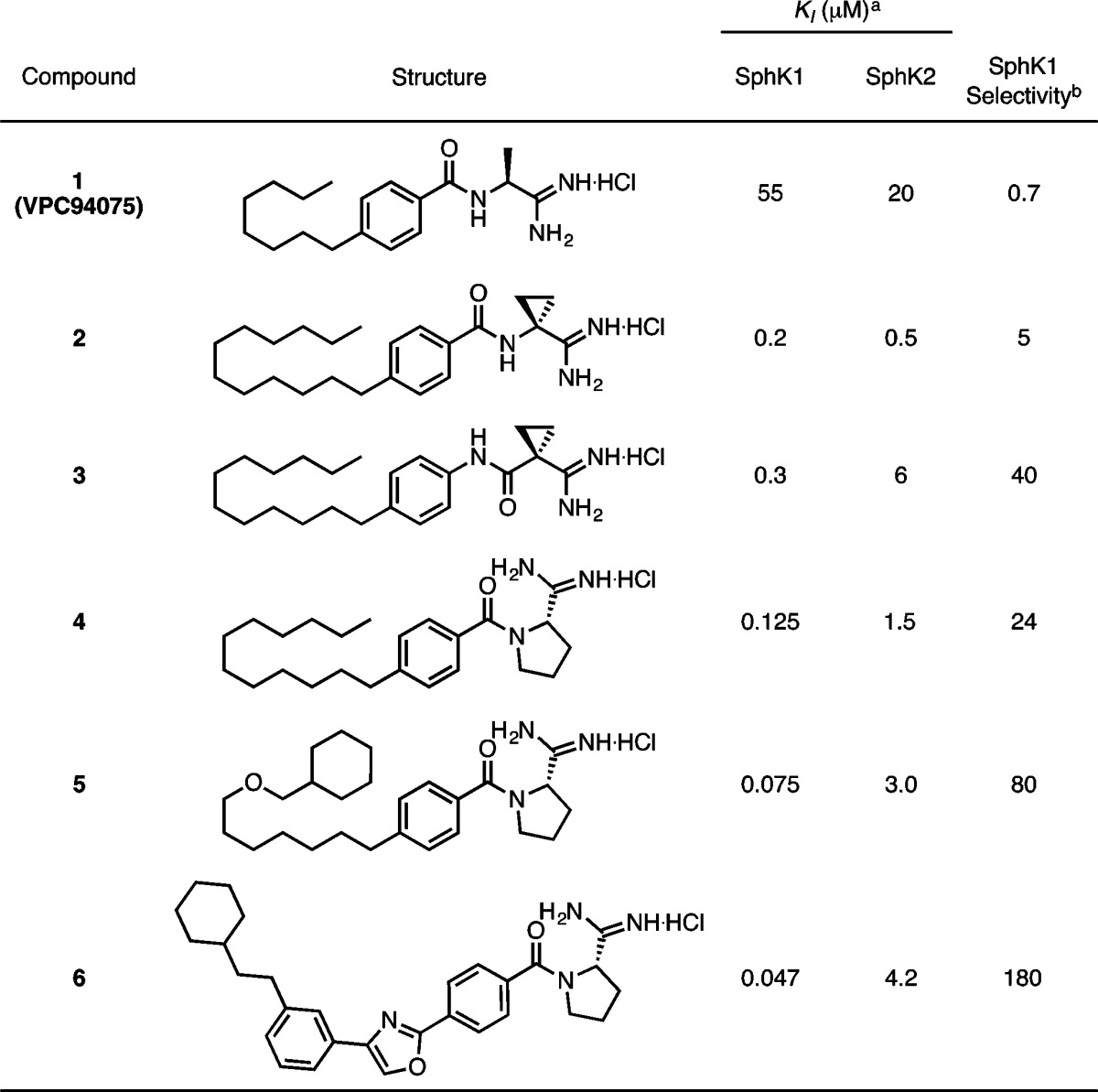

Our previous work yielded a series of amidine-based molecules displaying high potency and selectivity for SphK1. The lead molecule, 1, was modified to optimize tail length, amide orientation, and headgroup identity (2–4, Table 1).21 Further improvements were the result of in silico screening of a library of molecules with varied, rigidified tails. This analysis was carried out with a SphK1 homology model based on diacylglycerol kinase beta, and yielded 6, a SphK1 inhibitor with a KI of 47 nM and 180-fold selectivity over SphK2 (Table 1).22

Table 1. Previously Described Amidine-Based SphK Inhibitors20,21.

KI = [I]/(KM/KM – 1); KM of sphingosine at SphK1 = 10 μM; KM of sphingosine at SphK2 = 5 μM.

Selectivity = (KI/KM)SphK2/(KI/KM)SphK1.

In the work described presently, we followed a similar approach by optimizing a lead molecule with a library of synthetic variants and then following with in silico modeling. In this new series, the amide moiety was replaced with three distinct oxadiazoles; the reasoning for this is 3-fold: (1) our previous inhibitors have displayed poor half-lives in vivo and oxadiazoles are well-documented amide surrogates,23−27 (2) oxadiazoles have been effective structural subunits in our previous work with SphK2 substrates,28 and (3) oxadiazole linkers improved the efficacy of guanidine-based SphK1 inhibitors.17

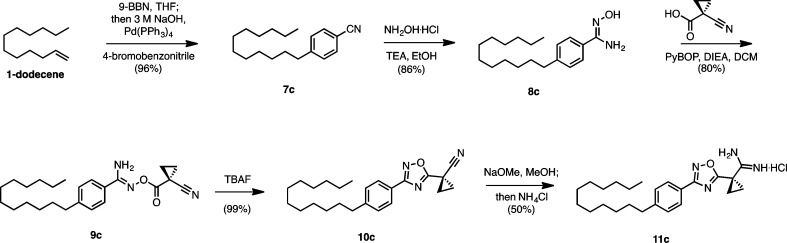

As a starting point, 11c, an analogue of 2 and 3, was synthesized as follows (Scheme 1). First, 1-dodecene was reduced to the alkyl borane with 9-BBN and coupled to 4-bromobenzonitrile using Suzuki conditions to p-alkylbenzonitrile 7c. Next, conversion to aryl amidoxime 8c was achieved using hydroxylamine hydrochloride and triethylamine in ethanol. PyBop-mediated coupling of the amidoxime to 1-cyano-1-cyclopropanecarboxylic acid yielded 9c. Cyclization of the coupled amidoxime with TBAF29 gave oxadiazole 10c and was subjected to base-catalyzed Pinner conditions30 to yield amidine 11c.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Oxadiazole Amidine 11c.

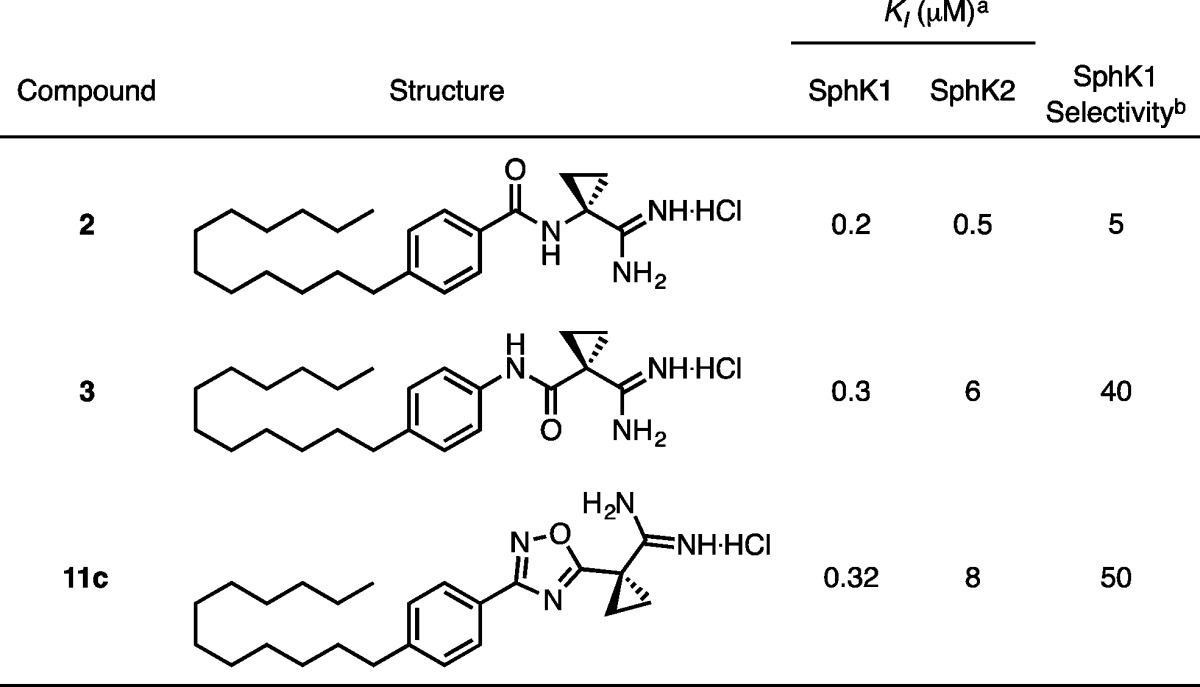

KI values were determined by a [γ-32P]ATP in vitro assay of SphK enzymatic activity (Table 2).31 Compound 11c maintains potency and SphK1 selectivity, validating the oxadiazole as a suitable replacement for the amide group.

Table 2. KI Values of Oxadiazole 11c Compared to Amides 2 and 3.

KI = [I]/(KM/KM – 1); KM of sphingosine at SphK1 = 10 μM; KM of sphingosine at SphK2 = 5 μM.

Selectivity = (KI/KM)SphK2/(KI/KM)SphK1.

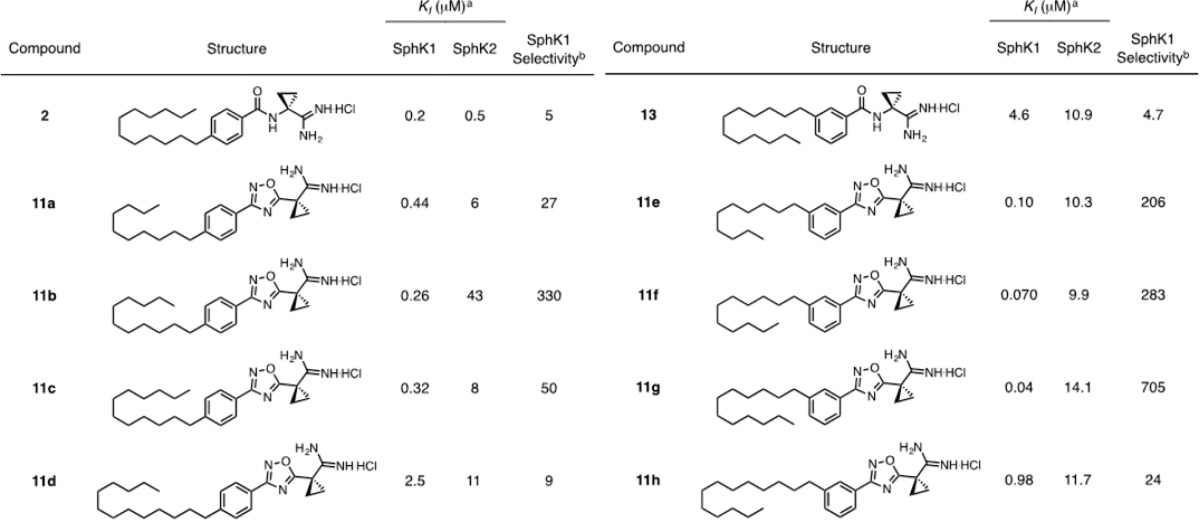

The incorporation of an oxadiazole into the molecular scaffold significantly alters the angle between the tail and head groups. With this in mind, a variant of 11c was synthesized with meta-substitution about the phenyl ring. Interestingly, upon attaching the tail at the meta position, potency and selectivity increased dramatically, with 11g displaying a KI of 40 nm and 705-fold selectivity for SphK1 over SphK2. As a control, a meta-substituted analogue of our amide compounds, 13, was synthesized (Scheme SI-1). This compound lost potency proportionately at both kinases (Table 3). meta-Substituted analogues present the amidine to the γ-phosphate of ATP such that the amidine is no longer antiperiplanar with the aromatic ring. Deletion of the cyclopropane ring alpha to the amidine resulted in a loss of activity in oxadiazole 15 (Scheme SI-2, Table SI-1). The unique torsional angle of the cyclopropane ring provides improved presentation of the amidine in the active site.

Table 3. KI Values of para- and meta-Substituted Oxadiazoles 11a–h Compared to Amide Analogues 2 and 13.

KI = [I]/(KM/KM – 1); KM of sphingosine at SphK1 = 10 μM; KM of sphingosine at SphK2 = 5 μM.

Selectivity = (KI/KM)SphK2/(KI/KM)SphK1.

Because the incorporation of oxadiazoles increases the overall molecular length, we altered the length of the alkyl tail to accommodate this change. Compounds with tails ranging from 10 to 13 carbons in length, both para- and meta-substituted, were synthesized through the same methods illustrated in Scheme 1 (KI values summarized in Table 3). The tail derivatives follow the same trend as our previous amidine-based inhibitors.21,22 Potency increases with tail length before dropping off at a length of 13 carbons. Tail substitution at the para position reaches a maximum potency and selectivity for SphK1 at a length of 11 carbons, with a KI of 0.26 μM (11b). Because an oxadiazole is one atom longer than an amide, it is expected that the 11-carbon tail fills out the sphingosine-binding pocket similarly to a 12-carbon tail on an amide analogue.

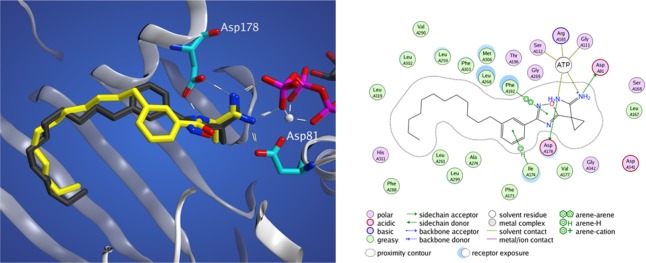

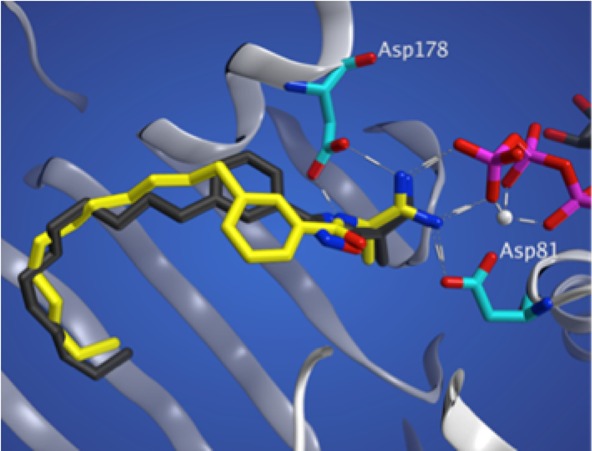

By integrating our previous work in the development of a SphK1 homology model22 with the recently determined SphK1 crystal structure,32 we have identified several key binding interactions between 11g and SphK1. On docking compounds 11g and 13 into a SphK1 model (generated with the crystal structure, PDB 4L02), one can see that meta amide (13) and meta oxadiazole (11g) adopt very different configurations (Figure 1). The oxadizaole inhibitor fills out the tail-binding region of the pocket to a greater extent than the amide. Further analysis reveals three cationic attractions of the amidine headgroup: to the γ-phosphate of ATP (as previously reported), and to Asp 81 and Asp178. Additionally, π-stacking between the oxadiazole and Phe192, which forms the roof of the pocket above the linker region, contributes to binding, as well as a favorable arene–H interaction between the phenyl ring and Ile-174.

Figure 1.

Docking studies with SphK1. (left) meta-Substituted oxadiazole (11g, black) and amide (13, yellow) derivatives docked into the crystal structure of SphK1. (right) Two-dimensional representation of 11g and its side chain interactions.

Following the evaluation of 11c and 11g, four additional compounds were synthesized to determine the relative efficacy of the three oxadiazole subtypes, as it has been reported in the literature that each individual regioisomer exhibits unique physical and pharmacological properties.33 For each oxadiazole subtype, both meta- and para-substituted variants were synthesized (Schemes SI-3 and SI-4).

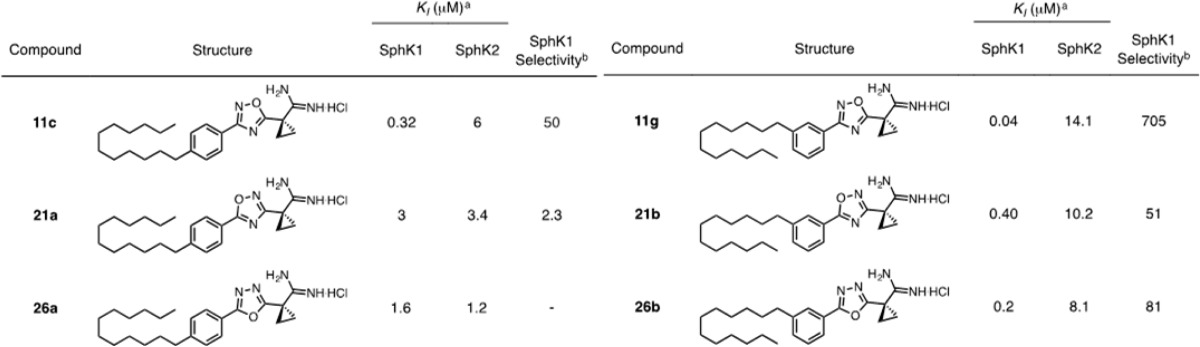

Biological evaluation revealed substantial differences in the inhibitory qualities of molecules containing isomeric oxadiazoles (Table 4). Surprisingly, the largest distinction occurred between compounds containing the 3-aryl (11c and 11g) and 5-aryl (21a and 21b) 1,2,4-oxadiazole isomers. Inhibitors 11c and 11g display significantly higher potency and selectivity for SphK1 than do 21a and 21b. Compounds containing 1,3,4-oxadiazoles (26a and 26b) display intermediate potency. Substitution about the phenyl ring again proved to be a very important factor, and all compounds with meta-substituted alkyl tails are much more potent and selective than para-substituted analogues.

Table 4. KI Values of Heterocyclic Isomers with meta- and para-Substitution about the Phenyl Ring.

KI = [I]/(KM/KM – 1); KM of sphingosine at SphK1 = 10 μM; KM of sphingosine at SphK2 = 5 μM.

Selectivity = (KI/KM)SphK2/(KI/KM)SphK1.

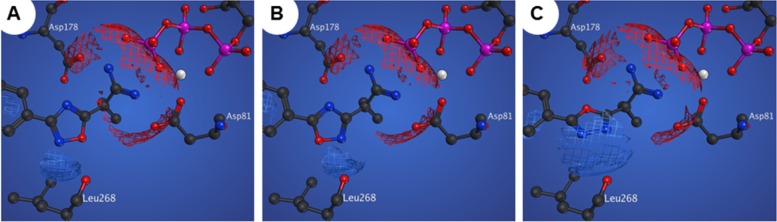

These marked differences in in vitro activity between oxadiazole subtypes can be rationalized, in part, with additional in silico analyses. Compounds 11g, 21b, and 26b were docked into the substrate-binding domain of SphK1, where the respective heterocycles appear to adopt different binding orientations (Figure 2). Most notably, electrostatic repulsion between the nonbonding electrons of the oxadiazole isomers and the backbone carbonyl of Leu268 destabilizes binding of compounds 21b and 26b. This interaction alters the positioning of the amidine headgroup, limiting binding interactions with the γ-phosphate of kinase-bound ATP. Furthermore, nitrogen atoms on the oxadiazoles of 21b and 26b likely undergo a repulsive interaction with the Asp81 residue.

Figure 2.

In silico docking of 11g (A), 21b (B), and 26b (C). White sphere = Mg2+.

These simulations suggest that, relative to isoforms present in other compounds, the particular 1,2,4-oxadiazole of 11g is subjected to minimal repulsive interactions in the SphK1 active site. This favorable binding orientation, coupled with meta-substitution about the phenyl ring, results in a significantly enhanced inhibitory profile. Compound 11g is not only highly potent but, with 705-fold selectivity for SphK1, is the most selective SphK1 inhibitor reported to date.

In summary, we have generated a library of amidine-based SphK1 inhibitors with in vitro potencies in the nanomolar range. Surprisingly, different oxadiazole subtypes elicited dramatically different effects regarding potency and selectivity; also, meta-substitution about the phenyl ring increased efficacy for all isomers. Docking analysis revealed important interactions between 11g and specific amino acid residues in the SphK1 active site, and provided justification for the favorable binding of this compound. This study contributes to the growing understanding of the structural requirements for SphK1 inhibition, and compounds such as 11g provide the ideal scaffold for future inhibitors. Simultaneous optimization of potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties will be necessary to further interrogate both SphKs in pathophysiology and to identify suitable therapeutic candidates in the fight against cancer and hyperproliferative diseases.

Acknowledgments

Support for Thomas Dawson was provided by the ARCS Foundation MWC and Mr. Gary Hoffman.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HDAC

histone deacetylace

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

- Sph

sphingosine

- SphK1

sphingosine kinase 1

- SphK2

sphingosine kinase 2

- SphKs

sphingosine kinases

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00002.

Experimental details for the synthesis of all compounds, compound characterization, and description of the SphK assay (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Maryland, 0107 Chemistry Building, College Park, Maryland 20742, United States.

Author Present Address

∥ University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1825 University Boulevard, Shelby Building, Birmingham, Alabama 35294, United States.

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM067958 to K.R.L. and T.L.M.; R01 GM104366 to K.R.L.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Blaho V. a; Hla T. An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 1596. 10.1194/jlr.R046300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne N. J.; Pyne S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 489–503. 10.1038/nrc2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun Y. A.; Obeid L. M. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 139–150. 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman M. R.; Pitson S. M. Inhibitors of the sphingosine kinase pathway as potential therapeutics. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2010, 10, 354–367. 10.2174/156800910791208599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W.-Q.; Wong W. S. F.; Leung B. P. Sphingosine kinase and sphingosine 1-phosphate in asthma. Biosci. Rep. 2011, 31, 145–150. 10.1042/BSR20100087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D. A.; Price K. L. Sphingosine kinase-1: a potential mediator of renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 815–817. 10.1038/ki.2009.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Berka V.; Song A.; Sun K.; Wang W.; Zhang W.; Ning C.; Li C.; Zhang Q.; Bogdanov M.; Alexander D. C.; Milburn M. V.; Ahmed M. H.; Lin H.; Idowu M.; Zhang J.; Kato G. J.; Abdulmalik O. Y.; Zhang W.; Dowhan W.; Kellems R. E.; Zhang P.; Jin J.; Safo M.; Tsai A. L.; Juneja H. S.; Xia Y. J. Elevated sphingosine-1-phosphate promotes sickling and sickle cell disease progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 2750–2761. 10.1172/JCI74604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S.; Cuvillier O.; Edsall L. C.; Kohama T.; Menzeleev R.; Olah Z.; Olivera A.; Pirianov G.; Thomas D. M.; Tu Z.; Van Brocklyn J. R.; Wang F. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in cell growth and cell death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 845, 11–18. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitson S. M. Regulation of sphingosine kinase and sphingolipid signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 97–107. 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos W. L.; Lynch K. R. Drugging sphingosine kinases. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 225–233. 10.1021/cb5008426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano D.; Amin S.; Sharma A. K. Importance of sphingosine kinase (SphK) as a target in developing cancer therapeutics and recent developments in the synthesis of novel SphK inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5509–5524. 10.1021/jm4011687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandy K. A. O.; Obeid L. M. Targeting the sphingosine kinase/sphingosine 1-phosphate pathway in disease: review of sphingosine kinase inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2013, 1831, 157–166. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi N.; Okada T.; Hayashi S.; Fujita T.; Jahangeer S.; Nakamura S. Sphingosine kinase 2 is a nuclear protein and inhibits DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46832–46839. 10.1074/jbc.M306577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait N. C.; Allegood J.; Maceyka M.; Strub G. M.; Harikumar K. B.; Singh S. K.; Luo C.; Marmorstein R.; Kordula T.; Milstien S.; Spiegel S. Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science 2009, 325, 1254–1257. 10.1126/science.1176709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer H. a; Pitson S. M. Roles, regulation and inhibitors of sphingosine kinase 2. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 5317–36. 10.1111/febs.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitson S. M.; Moretti P. A. B.; Zebol J. R.; Lynn H. E.; Xia P.; Vadas M. A.; Wattenberg B. W. Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5491–5500. 10.1093/emboj/cdg540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan N. N.; Morris E. A.; Kharel Y.; Raje M. R.; Gao M.; Tomsig J. L.; Lynch K. R.; Santos W. L. Structure–activity relationship studies and in vivo activity of guanidine-based sphingosine kinase inhibitors: discovery of sphK1- and sphK2-selective inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 1879–1899. 10.1021/jm501760d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott K.; Kharel Y.; Raje M. R.; Lynch K. R.; Santos W. L. Effect of alkyl chain length on sphingosine kinase 2 selectivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6817–20. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharel Y.; Morris E. A.; Thorpe S. B.; Tomsig J. L.; Santos W. L.; Lynch K. R. Sphingosine kinase type 2 and blood sphingosine 1-phosphate. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2015, 355, 23–31. 10.1124/jpet.115.225862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharel Y.; Raje M.; Gao M.; Gellett A. M.; Tomsig J. L.; Lynch K. R.; Santos W. L. Sphingosine kinase type 2 inhibition elevates circulating sphingosine 1-phosphate. Biochem. J. 2012, 447, 149–157. 10.1042/BJ20120609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews T. P.; Kennedy A. J.; Kharel Y.; Kennedy P. C.; Nicoara O.; Sunkara M.; Morris A. J.; Wamhoff B. R.; Lynch K. R.; Macdonald T. L. Discovery, biological evaluation, and structure-activity relationship of amidine based sphingosine kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2766–2778. 10.1021/jm901860h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A. J.; Mathews T. P.; Kharel Y.; Field S. D.; Moyer M. L.; East J. E.; Houck J. D.; Lynch K. R.; Macdonald T. L. Development of amidine-based sphingosine kinase 1 nanomolar inhibitors and reduction of sphingosine 1-phosphate in human leukemia cells. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3524–3548. 10.1021/jm2001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmus J. S.; Flamme C.; Zhang L. Y.; Barrett S.; Bridges A.; Chen H.; Gowan R.; Kaufman M.; Sebolt-Leopold J.; Leopold W.; Merriman R.; Ohren J.; Pavlovsky A.; Przybranowski S.; Tecle H.; Valik H.; Whitehead C.; Zhang E. 2-Alkylamino- and alkoxy-substituted 2-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazoles-O-alkyl benzohydroxamate esters replacements retain the desired inhibition and selectivity against MEK (MAP ERK Kinase). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 6171–6174. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBriar M. D.; Clader J. W.; Chu I.; Del Vecchio R. A.; Favreau L.; Greenlee W. J.; Hyde L. A.; Nomeir A. A.; Parker E. M.; Pissarnitski D. A.; Song L.; Zhang L.; Zhao Z. Discovery of amide and heteroaryl isosteres as carbamate replacements in a series of orally active gamma-secretase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 215–219. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boström J.; Hogner A.; Llinàs A.; Wellner E.; Plowright A. T. Oxadiazoles in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1817–1830. 10.1021/jm2013248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg S.; Estenne-Bouhtou G.; Luthman K.; Csoeregh I.; Hesselink W.; Hacksell U. Synthesis of 1,2,4-oxadiazole-, 1,3,4-oxadiazole-, and 1,2,4-triazole-derived dipeptidomimetics. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 3112–3120. 10.1021/jo00115a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garfunkle J.; Ezzili C.; Rayl T. J.; Hochstatter D. G.; Hwang I.; Boger D. L. Optimization of the central heterocycle of alpha-ketoheterocycle inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4392–4403. 10.1021/jm800136b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss F.; Mathews T.; Kharel Y.; Kennedy P.; Snyder A.; Davis M.; Lynch K.; Macdonald T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of sphingosine kinase substrates as sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor prodrugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6123–6136. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff A. R.; Litvak J.; Shelton E. J.; Sperandio D.; Wang V. R.; Rice K. D. Synthesis of 3,5-disubstituted-1,2,4-oxadiazoles using tetrabutylammonium fluoride as a mild and efficient catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 1441–1443. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)02288-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer F. C.; Peters G. A. Base-catalyzed reaction of nitriles with alcohols: A convenient route to imidates and amidine salts. J. Org. Chem. 1961, 26, 412–418. 10.1021/jo01061a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharel Y.; Mathews T. P.; Kennedy A. J.; Houck J. D.; Macdonald T. L.; Lynch K. R. A rapid assay for assessment of sphingosine kinase inhibitors and substrates. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 411, 230–235. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Min X.; Xiao S.-H.; Johnstone S.; Romanow W.; Meininger D.; Xu H.; Liu J.; Dai J.; An S.; Thibault S.; Walker N. Molecular basis of sphingosine kinase 1 substrate recognition and catalysis. Structure 2013, 21, 798–809. 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg K.; Groombridge S.; Hudson J.; Leach A. G.; MacFaul P. A.; Pickup A.; Poultney R.; Scott J. S.; Svensson P. H.; Sweeney J. Oxadiazole isomers: All bioisosteres are not created equal. MedChemComm 2012, 3, 600–604. 10.1039/c2md20054f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.