Abstract

Background and Purpose

Neuropeptide FF (NPFF) behaves as an endogenous opioid‐modulating peptide. In the present study, the opioid and NPFF pharmacophore‐containing chimeric peptide BN‐9 was synthesized and pharmacologically characterized.

Experimental Approach

Agonist activities of BN‐9 at opioid and NPFF receptors were characterized in in vitro cAMP assays. Antinociceptive activities of BN‐9 were evaluated in the mouse tail‐flick and formalin tests. Furthermore, its side effects were investigated in rotarod, antinociceptive tolerance, reward and gastrointestinal transit tests.

Key Results

BN‐9 acted as a novel multifunctional agonist at μ, δ, κ, NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors in cAMP assays. In the tail‐flick test, BN‐9 produced dose‐related antinociception and was approximately equipotent to morphine; this antinociception was blocked by μ and κ receptor antagonists, but not by the δ receptor antagonist. In the formalin test, supraspinal administration of BN‐9 produced significant analgesia. Notably, repeated administration of BN‐9 produced analgesia without loss of potency over 8 days. In contrast, repeated i.c.v. co‐administration of BN‐9 with the NPFF receptor antagonist RF9 produced significant antinociceptive tolerance. Furthermore, i.c.v. BN‐9 induced conditioned place preference. When given by the same routes, BN‐9 had a more than eightfold higher ED50 value for gastrointestinal transit inhibition compared with the ED50 values for antinociception.

Conclusions and Implications

BN‐9 produced a robust, nontolerance‐forming analgesia with limited inhibition of gastrointestinal transit. As BN‐9 is able to activate both opioid and NPFF systems, this provides an interesting approach for the development of novel analgesics with minimal side effects.

Abbreviations

- BN‐9

Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐Gln‐Pro‐Gln‐Arg‐Phe‐NH2

- NPFF

neuropeptide FF

- RF9

1‐adamantanecarbonyl‐RF‐NH2

- SR16435

1‐(1‐bicyclo[3.3.1]nonan‐9‐yl) piperidin‐4‐yl)indolin‐2‐one

- NOP

nociceptin

- ESP7

Tyr‐Pro‐Phe‐Phe‐Gly‐Leu‐Met‐NH2

- TY005

Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐Met‐Pro‐Leu‐Trp‐O‐3,5‐Bn(CF(3))(2)

- TY027

Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐Met‐Pro‐Leu‐Trp‐NH‐[3′,5′‐(CF(3))(2)Bzl]

- NK1 receptor

neurokinin receptor 1

- 1DMe

[D.Tyr1,(N.Me)Phe3]NPFF

- β‐FNA

β‐funaltrexamine

- nor‐BNI

nor‐binaltorphimine

- MPE

maximum possible effect

- CPP

conditioned place preference

Tables of Links

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (Alexander et al., 2015).

Introduction

The clinical treatment of chronic and severe pain relies widely on opioid analgesics, such as morphine and other μ receptor agonists (Zollner and Stein, 2007; Stein, 2013; Portenoy and Ahmed, 2014). However, their therapeutic uses are constrained by the unwanted side effects, including constipation, respiratory depression, the development of tolerance and physical dependence (Inturrisi, 2002; Zollner and Stein, 2007; Stein, 2013). Recently, the development of bi‐ or multifunctional opioid drugs have emerged as an attractive therapeutic strategy for pain management. In fact, a series of bifunctional opioid compounds containing opioid, substance P, cholecystokinin, nociceptin (NOP), neurotensin, cannabinoid, imidazoline, melanocortin, bradykinin or nicotine pharmacophore were characterized, and several bifunctional compounds were reported to produce potent antinociception with reduced side effects (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980; Foran et al., 2000; Hruby et al., 2003; Khroyan et al., 2007; Ballet et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2009; Largent‐Milnes et al., 2010; Schiller, 2010; Fang et al., 2012; Kleczkowska et al., 2013). SR 16435, a bifunctional compound with both NOP and μ receptor agonist properties, produced antinociceptive effects with reduced rewarding properties (Khroyan et al., 2007). ESP7 containing overlapping opioid agonist and substance P agonist pharmacophore sequences could induce analgesia without development of tolerance (Foran et al., 2000). TY005 and TY027, two compounds with both opioid agonist and NK1 antagonist pharmacophores, produced potent antinociceptive effects and had fewer of the unwanted side effects of opioids, including tolerance (Yamamoto et al., 2009; Largent‐Milnes et al., 2010). In addition, bifunctional opioid compounds represent a valuable probe for the interactions between opioid and other systems due to their different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters from drug combinations (Hruby et al., 2003; Schiller, 2010).

Neuropeptide FF (NPFF, Phe‐Leu‐Phe‐Gln‐Pro‐Gln‐Arg‐Phe‐NH2) was isolated from bovine brain in 1985 and is, at present, considered to be an endogenous opioid‐modulating peptide (Yang et al., 1985; Mollereau et al., 2005; Mouledous et al., 2010). Recent reports have shown that NPFF belongs to a neuropeptide family that includes two precursors (pro‐NPFFA and pro‐NPFFB) and two GPCRs (NPFF1 and NPFF2) (Perry et al., 1997; Vilim et al., 1999; Bonini et al., 2000; Elshourbagy et al., 2000; Hinuma et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2001). There is mounting evidence indicating that NPFF has no effects on nociception alone and modulates opioid‐induced antinociception differentially, depending on its site of administration (Roumy and Zajac, 1998; Panula et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2011). NPFF delivered by the i.c.v. route has been shown to block morphine‐induced analgesia (Panula et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2011). In contrast, i.t. administration of NPFF potentiated morphine analgesia (Kontinen and Kalso, 1995). The role of the NPFF system in modulating opioid‐induced tolerance and physical dependence has been examined previously (Liu et al., 2001; Simonin et al., 2006; Mouledous et al., 2010). An increase in NPFF levels in the CNS might contribute to the development of tolerance and dependence for opioids (Yamamoto et al., 2009; Mouledous et al., 2010). In addition, the NPFF receptor antagonist RF9 significantly blocked opioid tolerance and physical dependence (Simonin et al., 2006). It is notable that NPFF was found to inhibit the acquisition and expression of morphine‐induced conditioned place preference (CPP) and the acquisition and the expression of endomorphin‐2‐induced conditioned place aversion (Marchand et al., 2006; Kotlinska et al., 2007; Han et al., 2013). Therefore, it seems that activation of NPFF receptors can reduce opioid‐induced reward.

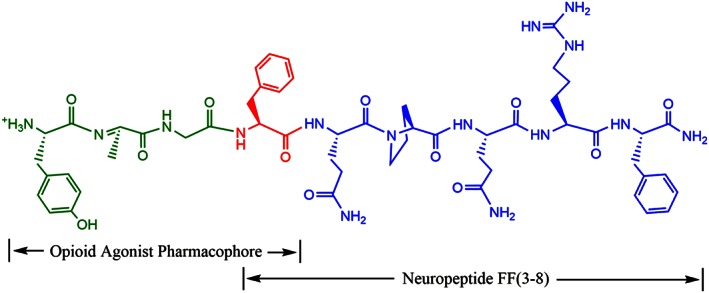

On basis of the opioid‐modulating properties of NPFF, efforts have been made to develop bifunctional peptides containing opioid and NPFF receptor agonists expected to evaluate their interaction. Thus, we have designed a chimeric peptide where both opioid and NPFF pharmacophores are fused. For the opioid agonist pharmacophore, the half‐structure of the opioid agonist biphalin (Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐NH‐) was chosen. Compared to the biphalin and NPFF amino acid sequences, this overlapping phenylalanine residue was used in conjunction with the N‐terminal amino acids unique to biphalin and C‐terminal amino acids unique to NPFF. In the present study, the antinociceptive profiles and related side effects of BN‐9 (Figure 1), a novel peptide with mixed opioid and NPFF receptor agonistic properties, were investigated in mice.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of the novel multi‐targeting peptide BN‐9 (Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐Gln‐Pro‐Gln‐Arg‐Phe‐NH2). The amino acid sequence of BN‐9 contains overlapping opioid and NPFF motieties. The N‐terminus corresponds to that of the halfstructure of biphalin (Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐NH), and the C termini corresponds to NPFF(3–8) (NPFF = Phe‐Leu‐Phe‐Gln‐Pro‐Gln‐Arg‐Phe‐NH2) respectively.

Methods

Group sizes

For in vitro functional assays, data are mean of at least three individual experiments conducted in duplicate. For antinociceptive effects of supraspinal, spinal or systemic BN‐9 in the mouse tail‐flick test, data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. For antagonism of BN‐9‐induced supraspinal or spinal antinociception, data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on eight mice. For effects of the NPFF receptor antagonist RF9 on the BN‐9‐induced supraspinal or spinal antinociceptionin in the mouse tail‐flick test, data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. For antinociceptive effects of i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 in the mouse formalin test, data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. For motor impairment evaluation of BN‐9, data points represent mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least eight mice. For antinociceptive tolerance studies of BN‐9, data points represent mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. For other side‐effect evaluation of BN‐9, results are presented as mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least nine mice. The exact group size for each experimental group is shown on the figures or in the figure legends.

Randomization

Randomization was performed by an individual other than the operator. In in vitro functional assays, cells were randomly added to 24‐well cell culture plates or 96‐well OptiPlates (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). In all the animal experiments, mice were selected randomly from the pool of all cages and randomly divided into the experimental groups.

Blinding

All the data were collected and analysed by two independent observers, who were blinded to the group assignment of samples or animals in in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Normalization

For cAMP assays, the drug concentrations are expressed as log transformation as described previously (Gusovsky, 2001), and EC50 values were calculated by using Graphpad prism (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). For radiant heat tail‐flick test, data are expressed as the percent maximum possible effect (MPE) as described earlier (Fang et al., 2012). For gastrointestinal transit test, the % gastrointestinal transit (GIT) was calculated as the percentage of the small intestine tract that was traversed.

Validity of animal species or model selection

The animal species and model selected for study were as described previously (Han et al., 2014).

Interpretation

This study complied with the replacement, refinement and reduction (the 3Rs).

Animal welfare and ethical statement

The experiments were performed on male Kunming strain mice (18–22 g) from the Experimental Animal Centre of Lanzhou University. The mice were housed in a temperature‐controlled room (22 ± 1°C). The type of facility was specific pathogen free. Standard Makrolon type‐II cages were used, and bedding material was clean sawdust. Food and water were freely available until the onset of the behavioural tests. All animals were cared for, and experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Community guidelines for the use of experimental animals (2010/63/EU). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). All the protocols in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University (permit number: SYXK Gan 2009–0005), China.

Drugs

The chemical structure of this chimeric peptide BN‐9 (Tyr‐D.Ala‐Gly‐Phe‐Gln‐Pro‐Gln‐Arg‐Phe‐NH2) is shown in Figure 1. BN‐9 and RF9 were prepared by manual solid‐phase synthesis using standard N‐fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry as described previously (Han et al., 2014). Fmoc‐protected amino acids (GL Biochem Ltd., Shanghai, China) were coupled to a Rink Amide MBHA resin (Tianjin Nankai Hecheng Science & Technology Co., Ltd., China). Gel filtration (Sephadex G‐25; Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech (China) Ltd., Shanghai, China) was performed to desalt the crude peptide of BN‐9. The desalted peptide was purified by preparative reversed‐phase HPLC using a Waters Delta 600 system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a UV detector. Fractions containing the purified peptides were pooled and lyophilized. The purity of the peptide was established by analytical HPLC. The molecular weight of the peptide was confirmed by an electrospray ionization mass spectrometer (ESI‐Q‐TOF maXis‐4G; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

In addition, the opioid antagonists, including naloxone, β‐FNA, naltrindole and nor‐binaltorphimine (nor‐BNI) were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Morphine hydrochloride was the product of Shenyang First Pharmaceutical Factory, China. All drugs were dissolved in sterilized distilled saline and stored at −20°C.

In vitro functional assays (cAMP assays)

The in vitro functional activities of BN‐9 were assessed in cAMP assays. HEK293 cells, which stably expressing the μ, δ, κ or NPFF1 receptor, were seeded at a concentration of 1.2 × 105 per well in 24‐well cell culture plates and cultured for 24 h. At the beginning of the assay, we removed the culture medium and added 500 μL prewarmed serum‐free medium containing 1 mM IBMX (a cAMP phosphodiesterases inhibitor) to each well. After an incubation of 10 min at 37°C, 10 μL of various concentrations of drugs and 10 μL of 0.5 mM forskolin were added to each well and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After the incubation, the final aqueous solution was tested for cAMP levels by a competition protein binding assay as described previously (Gusovsky, 2001). The concentrations of cAMP in lysates were calculated using the standard curve, which was constructed using cAMP standards.

cAMP Zen® frozen cells expressing the human NPFF2 receptor (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) were used in the cAMP assay for NPFF2 receptor. The cyclase functional assays were performed using the LANCE™ cAMP kit (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the frozen cells were thawed and suspended in the stimulation buffer (HBSS containing 0.1% BSA, 5 mM HEPES and 0.5 mM of IBMX). The cell suspension containing Alexa Fluor® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) 647‐labelled antibodies was added to a 96‐well OptiPlate (10 μL per well), and then 10 μL of drugs and 20 μM forskolin in stimulation buffer were added. After being incubated for 30 min at room temperature, 20 μL of detection mix was added. The LANCE signals were detected using a Flex station‐3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) 1 h later.

Plantation of cannula into ventricle

Surgical implantation of the cannula was conducted in an aseptic environment, as described previously (Fang et al., 2012). Mice were anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (80 mg·kg−1, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The incision area of the scalp was shaved, and a sagittal incision was made in the midline exposing the surface of the skull. A single hole was drilled through the targeted skull. The coordinates for the placement of the cannula were as follows: 3 mm posterior from bregma, 1 mm lateral and 3 mm ventral from the skull surface for the lateral ventricle (i.c.v. injection). To prevent occlusion, a dummy cannula was inserted into the guide cannula. The dummy cannula protruded 0.5 mm from the guide cannula. Dental cement was used to fix the guide cannula to the skull. After surgery, the animals were allowed to recover for at least 4 days, and during this time, mice were gently handled daily to minimize the stress associated with manipulation of the animals throughout the experiments.

At the end of the experiments, mice were injected with methylene blue dye (3 μL), which was allowed to diffuse for 10 min. Then mice were decapitated, and their brains were removed and frozen. Gross dissection of the brains was used to verify the placement of the cannula. Only the data from those animals with dispersion of the dye throughout the ventricles were used in the study.

Drug administration

Drugs were administered into the lateral ventricle at a fixed volume of 4 μL (at a constant rate of 10 μL·min−1), which was followed by 1 μL saline to flush in the drug by using a 25 μL microsyringe. The i.t. injection procedure was adopted as described by Hylden and Wilcox (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980). Briefly, a 28‐gauge needle connected to a 25 μL microsyringe was directly inserted between the L5 and L6 segment in mice. Puncture of the dura was indicated by a reflexive lateral flick of the tail or formation of an ‘S’ shape by the tail (Fairbanks, 2003). Drugs were injected into the subarachnoid space in a volume of 5 μL at a constant rate of 20 μL·min−1. For i.v. administration, mice were placed in restrainers, and injections were made using a disposable 1 mL syringe equipped with a 30‐gauge disposable needle as described previously (Vanderah et al., 2004). The needle was inserted into the tail vein at an angle of approximately 25°. A small amount of blood was drawn back into the syringe before injection of either drugs or vehicle to ensure injection into the vein. Drugs or vehicle was given over a 5 s period at a volume of 100 μL.

The opioid antagonists, including naloxone, β‐FNA, naltrindole and nor‐BNI were injected 10 min, 4 h, 10 min and 30 min, respectively, prior to BN‐9. The NPFF receptor antagonist RF9 was injected 5 min prior to BN‐9.

Radiant heat tail‐flick test

Male Kunming mice were gently restrained by hand, and a light beam was focused onto the tail. At the beginning of the study, the lamp intensity was adjusted to elicit a response in control animals within 3–5 s. A cut‐off time was set at 10 s to minimize tissue damage. Tail‐flick time was determined before injection and then at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 90 min post‐injection. Every male mouse was used only once. Data are expressed as MPE calculated as: MPE (%) = 100 × [(post‐drug response − baseline response)/(cut‐off response − baseline response)]. The raw data from nociceptive tests were converted to AUC. The AUC depicting total % MPE versus time was computed by trapezoidal approximation over the period 0–60 min (i.c.v. injection) or 0–30 min (i.t. and i.v. injection).

Formalin‐induced nociceptive behavioural test

The animals were placed in a transparent acrylic observation chamber (20 × 20 × 30 cm) with a mirror positioned at a 45° angle below the floor allowing an unobstructed view of the animal's hindpaw, the animal was allowed to acclimatize to the test conditions for a period of 15 min. Twenty microlitres of 5% formalin (dissolved in 0.9% saline) solution was injected s.c. under the surface of the right hindpaw. Control mice were observed from 0 to 40 min following formalin injection. The early nociceptive response phase normally peaked 0–5 min and the late phase 15–30 min after formalin injection, demonstrating the direct stimulation of nociceptors and an inflammatory nociceptive response respectively. Mice were i.c.v. administered BN‐9, morphine or saline, then received an intraplantar injection of formalin 5 min later. Following the formalin injection, the animals were immediately put back in the observation chamber, and the time spent licking, shaking and biting the injected paw was measured with a stopwatch. The times observed were converted to % MPE as follows: % MPE = 100 × [(control time − post‐drug time)/control time].

Metabolic stability

Enzymatic degradation studies of BN‐9 were carried out using mouse brain homogenate. The 15% mouse brain homogenate was prepared as described previously (Horan et al., 1993; Wang et al., 2012). The protein content of the suspension was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). A final protein concentration of 2.1 mg·mL−1 in Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) was used for all incubations. A total of 10 μL of peptide stock solution (10−2 M) was added to 190 μL of mouse brain homogenate an the sample was incubated at 37°C. Aliquots of 20 μL were withdrawn from the mixture at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120 and 240 min, and 90 μL of acetonitrile was added immediately for precipitating proteins. The sample was maintained on ice for 5 min, and 90 μL of 0.5% acetic acid was added at the required time to prevent further enzymatic breakdown. The aliquots were centrifuged at 13 000 g for 15 min. The supernatants were collected for HPLC analysis. Linear regression was used to calculate the metabolic half‐life of BN‐9 incubated in brain homogenates.

Rotarod test

Male mice were tested for their ability to balance on the rotarod (3 cm diameter; rate of rotation, 16 revolutions per minute) after i.c.v., i.t. or i.v. administration of BN‐9 or vehicle. Prior to drug administration, animals were trained in three consecutive sessions to stay on the rod and reach the cut‐off time of 300 s. Animals that did not remain on the rod for the 180 s were not used for the experiments. After 2 days of training, three times a day, mice were tested at 10, 20, 30 and 40 min after administration of the vehicle or drug. The latency to fall off the rod was recorded at each time point. Results are expressed as the time that mice stayed on the rotarod for each drug treatment.

Tolerance development to antinociception

Mice received i.c.v. or i.t. injections of saline, morphine and BN‐9 once daily for 8 days. To evaluate the effect of RF9 on the tolerance development of morphine and BN‐9, RF9 was i.c.v. co‐injected with these agonists for 5 days, then no RF9 was given on day 6–8. Animals were tested for tail‐flick latencies before injections using the equipment and methods described earlier and then received an injection of their assigned dose of drug and were tested at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30 min every testing day. The period 0–30 min was chosen because of the maximal effects of i.c.v. or i.t. injection of morphine and BN‐9 were seen at 30, 10, 15 and 10 min after administration respectively. % MPE was calculated as the analgesia assessment described earlier.

Place conditioning experiment

The CPP apparatus was divided into three compartments. Two identical‐sized compartments (20 cm × 20 cm × 20 cm) were connected by a narrower one (5 cm × 20 cm × 20 cm). The large compartments were visually and tactually distinct (black‐and‐white striped walls with rough floor versus black‐dotted white walls with smooth floor). These boxes could be isolated by guillotine doors.

On the pre‐conditioning day (day 1), mice were given free access to the entire apparatus for 15 min, and the time spent in each compartment was measured. Mice that spent more than 60% of the time in the same compartment were excluded from the tests (less than 5% of mice). On the conditioning days, mice were i.c.v. injected with saline and confined to one of the compartments for 15 min. Approximately 6 h later, animals were administered, i.c.v., saline, morphine or BN‐9 and confined to the opposite compartment. This conditioning procedure was carried out for a total of three identical conditioning sessions (days 2–4). On the test day (post‐conditioning day, day 5), mice were also given free access to the entire apparatus for 15 min, and the time spent in each compartment was measured. CPP score was expressed as time spent in the drug‐associated compartment on post‐conditioning day minus time spent in the drug‐associated compartment on pre‐conditioning day.

Gastrointestinal transit test

The mouse gastrointestinal transit test was conducted to evaluate the effects of drugs on the movement of chyme in the mouse small intestine. Mice were fasted for 16 h with water available ad libitum before the experiments. Fifteen minutes after i.c.v. administration of drugs, a charcoal meal (an aqueous suspension of 5% charcoal and 10% gum arable) was administered orally at a volume of 0.1 mL·10 g−1 body weight. Thirty minutes after charcoal meal administration, the animal was killed by cervical dislocation, and the small intestine from the pylorus to the caecum was carefully removed. Both the length from the pylorus to the caecum, and the distance, which the charcoal meal traveled furthest, were measured. For each animal, GIT % was calculated as the percentage of the small intestine tract that was traversed.

Statistical analysis

The EC50 values for the inhibition of forskolin‐induced cAMP accumulation and the corresponding 95% confidence limits were calculated by using Graphpad prism 5. The time‐courses for effects of drugs were analysed using a two‐way ANOVA, and corresponding AUC data were analysed using a one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. The other data obtained from tail‐flick test, formalin test, rotarod test and gastrointestinal transit test were given as means ± SEM and further analysed with one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's or Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data obtained from tolerance development and the CPP test were statistically compared by means of one‐way ANOVA followed by the Tukey HSD (honest significant difference) test. The post hoc tests were only performed when the F‐value was significant and there was no variance in homogeneity. Probabilities of less than 5% (P < 0.05) were considered statistically significant. The ED50 and the corresponding 95% confidence interval were determined using GraphPad prism 5. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015).

Results

In vitro functional assays of BN‐9

Figure 1 depicts the chemical structure of the novel chimera of opioid peptide and NPFF(3–8), designated BN‐9. The pharmacological and biochemical properties of BN‐9 were further evaluated in in vitro and in vivo assays.

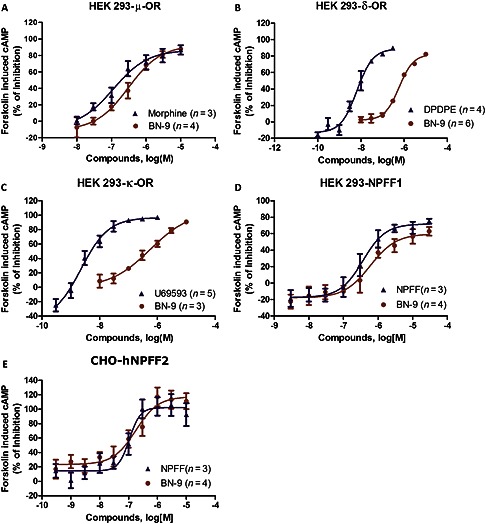

In the cAMP assays to test functional activity, BN‐9 behaves as a full agonist at μ, δ, κ, NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors with maximal effect values comparable with the reference compounds (Figure 2 and Table 1). The novel chimeric peptide BN‐9 was revealed to be a full μ receptor agonist with EC50 values comparable with those of the reference compound morphine. In contrast, the potencies of BN‐9 at the δ and κ receptors were much lower than those of the reference compounds. In addition, the potencies of BN‐9 at the NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors were comparable with the reference agonist NPFF. Taken together, BN‐9 functioned as a mixed agonist towards μ, δ, κ, NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors in vitro.

Figure 2.

In vitro functional activities of BN‐9 and reference compounds in cAMP assays. Representative concentration‐response curves at μ, δ, κ, NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors are presented. Data are mean of at least three individual experiments conducted in duplicate. Similar concentration‐response curves were used to generate pEC50 and Emax (%) values for each test compound, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

In vitro agonist functional activities of BN‐9 in cAMP assays

| Receptors | BN‐9 | Refernce Compounds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEC 50 | E max (%) | pEC 50 | E max (%) | ||

| μ | 6.51 ± 0.15 | 92.4 ± 9.7 | Morphine | 6.94 ± .25 | 86.6 ± 8.4 |

| δ | 6.23 ± 0.06 | 82.2 ± 3.7 | DPDPE | 8.18 ± 0.09 | 88.8 ± 5.5 |

| κ | 6.25 ± 0.25 | 105.6 ± 20.7 | U59693 | 8.65 ± 0.18 | 96.8 5.1 |

| NPFF1 | 6.23 ± 0.18 | 59.9 ± .3 | NPFF | 6.44 ± 0.12 | 71.8 ± .9 |

| NPFF2 | 6.75 ± 0.18 | 117.4 ± 10.0 | NPFF | 6.97 ± 0.11 | 102.3 ± .0 |

Efficacy values expressed the inhibition by the agonists of forskolin‐induced accumulation of cAMP. Data are mean of at least three individual experiments conducted in duplicate. pEC50 is the negative logarithm to base 10 of the agonist molar concentration that produces 50% of the maximal possible effect of that agonist. The Emax (%) is the maximal possible effect of that agonist.

Antinociceptive effects of BN‐9

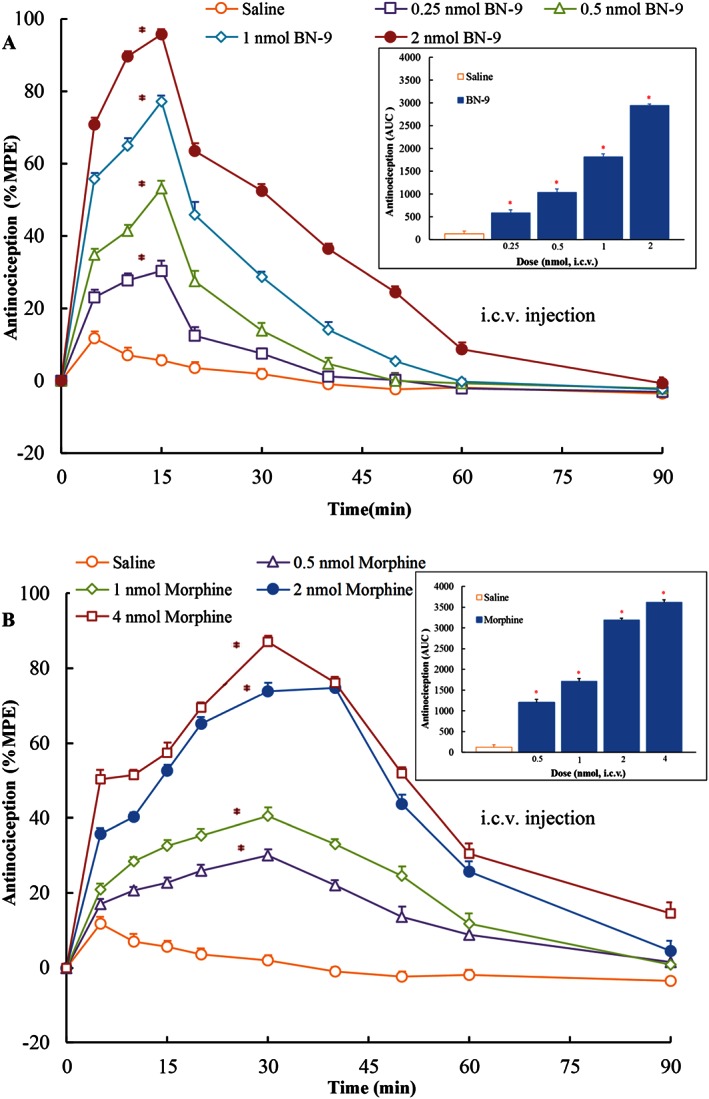

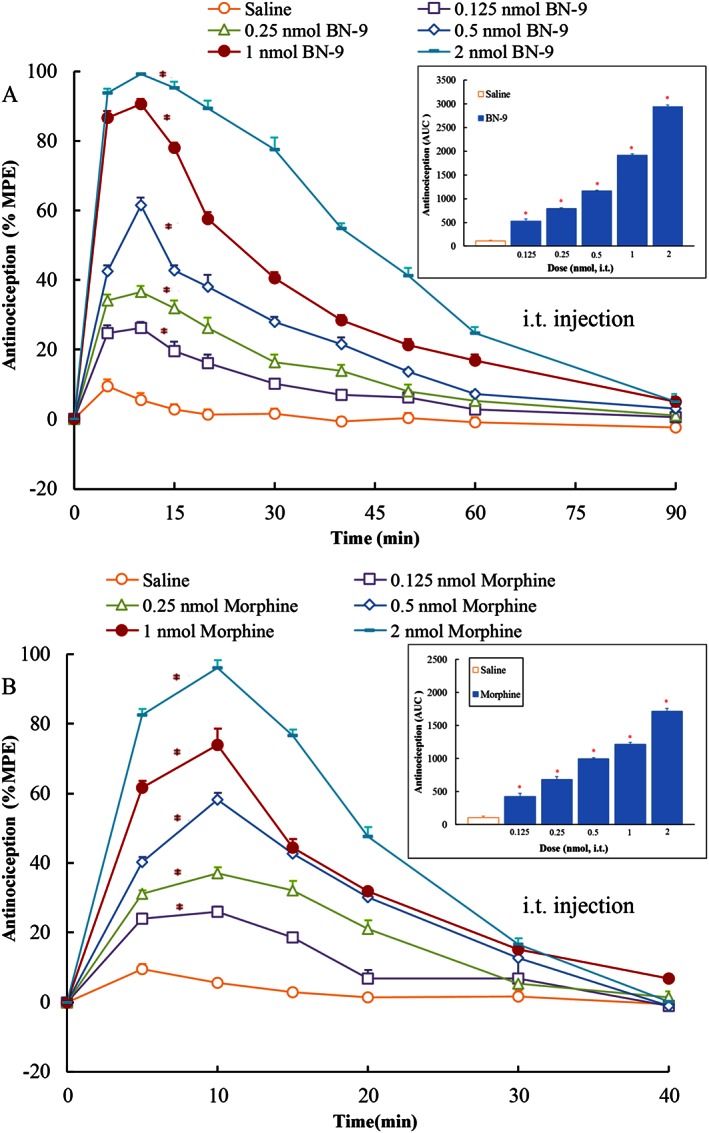

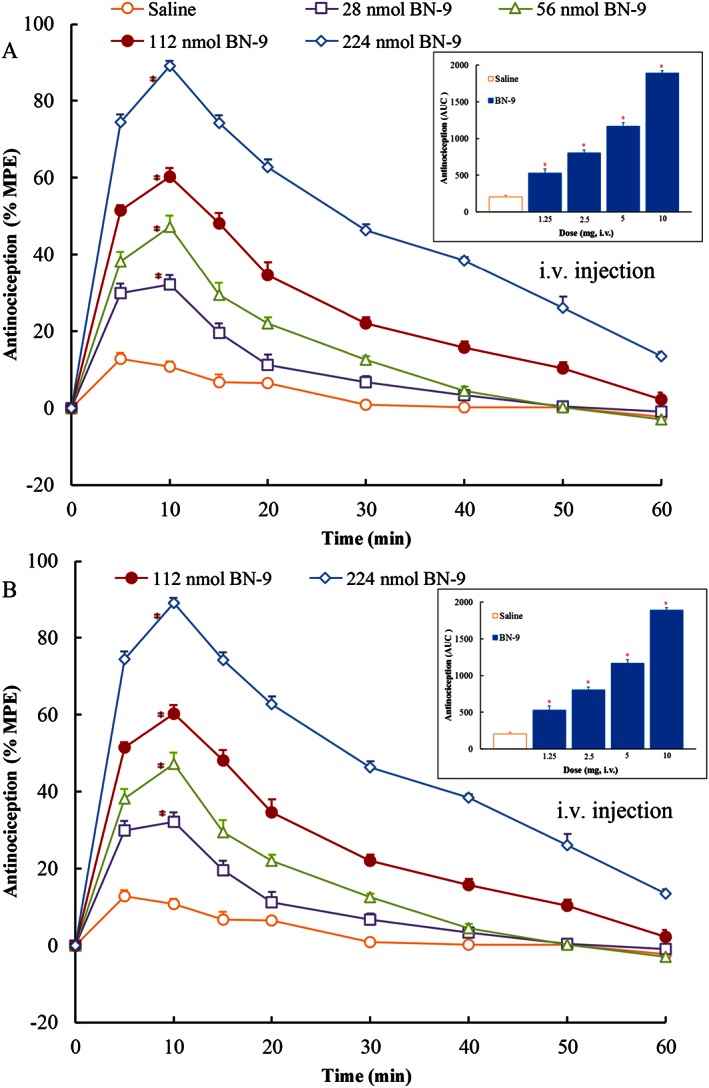

The dose‐ and time‐related antinociceptive effects of BN‐9 and the reference compound morphine injected by the different routes were investigated using the mouse tail‐flick test. In Figure 3, i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 and morphine produced significant antinociception. The two‐way ANOVA of data of BN‐9 revealed significant effects for both dose and time, F 4,350 = 966.1, P < 0.05 and F 9,350 = 740.1, P < 0.05, respectively, as well as, a statistically significant dose × time interaction, F 36,350 = 60.79, P < 0.05. The two‐way ANOVA of data for morphine also revealed significant effects (Dose F 4,350 = 1021, P < 0.05; Time F 9,350 = 349.8, P < 0.05; Dose × Time Interaction, F 36,350 = 36.84, P < 0.05). BN‐9 was approximately 2.6‐fold more potent than morphine with ED50 values of 0.39 nmol for BN‐9 and 1.02 nmol for morphine (Table 2). As shown in Figure 4, when administered i.t., both BN‐9 and morphine were potent at producing significant antinociception (For BN‐9, Dose F 5,370 = 1357, P < 0.05; Time F 9,370 = 713.9, P < 0.05; Dose × Time Interaction, F 45,350 = 64.44, P < 0.05. For morphine, Dose F 5,259 = 461.0, P < 0.05; Time F 6,259 = 349.8, P < 0.05; Dose × Time Interaction, F 30,259 = 51.61, P < 0.05). The ED50 value for BN‐9 was comparable with that obtained with the reference compound morphine (Table 2). BN‐9 gives an above‐baseline antinociceptive effect for 60 min compared with morphine, which was at baseline, by 40 min (Figure 4). In addition, when given i.v., BN‐9 produced a time‐ and dose‐dependent antinociception with an ED50 value of 58.6 nmol, and a time‐to‐peak effect was 10 min (Figure 5A; Dose F 4,270 = 802.3, P < 0.05; Time F 8,270 = 489.4, P < 0.05; Dose × Time Interaction, F 32,270 = 32.28, P < 0.05). Morphine induced a marked antinociception with an ED50 value of 46.2 nmol after i.v. administration (Figure 5B; Dose F 4,270 = 963.1, P < 0.05; Time F 8,270 = 604.7, P < 0.05; Dose × Time Interaction, F 32,270 = 70.65, P < 0.05), which showed a slightly better analgesia relative to BN‐9 (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Antinociceptive dose‐ and time‐response curves for supraspinal (i.c.v.) BN‐9 or morphine in the mouse tail‐flick test. Data points represent ± SEM from experiments conducted on eight mice. AUC calculated during 0–60 min from these data were statistically analysed and are presented in the text. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test performed on AUC data.

Table 2.

Antinociceptive effects or GIT inhibition induced by BN‐9 and morphine when administered by different in mice

| Routes of injection | ED 50 values (nmol) for tail‐flick test | Ratio (Morphine /BN‐9) | ED 50 values (nmol) of BN‐9 for formalin test | ED 50 values (nmol) of BN‐9 for GIT inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN‐9 | Morphine | Phase I | Phase II | |||

| i.c.v. | 0.39 (0.33, 0.46) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) | 2.62 | 0.12 (0.11, 0.13) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.45) | 3.39 (2.73, 4.21) |

| i.t. | 0.29 (0.24, 0.34) | 0.35 (0.30, 0.40) | 1.21 | — | — | 2.70 (1.63, 4.46) |

| i.v. | 58.6 (50.8, 67.4) | 46.2 (38.7, 55.2) | 0.79 | — | — | 490.0 (301.5, 796.3) |

The ED50 (dose of agonists that produced half of the maximal antinociception or GIT inhibition) values with their 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the dose–response curve using nonlinear regression analysis with the GraphPad PRISM version 5.0 programme.

Figure 4.

Antinociceptive dose‐ and time‐response curves for spinal (i.t.) BN‐9 or morphine in the mouse tail‐flick test. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. Final group sizes: (A) saline: n = 7, 0.125 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, 0.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, 0.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, 1 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, 2 nmol BN‐9: n = 8. (B) Saline: n = 7, 0.125 nmol morphine: n = 7, 0.25 nmol morphine: n = , 0.5 nmol morphine: n = 7, 1 nmol morphine: n = 7, 2 nmol morphine: n = 8. AUC calculated during 0–30 min from these data were statistically analysed and are presented in the text. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test performed on AUC data.

Figure 5.

Antinociceptive dose‐ and time‐response curves for systemic (i.v.) BN‐9 or morphine in the mouse tail‐flick test. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on seven mice. AUC calculated during 0–30 min from these data were statistically analysed and are presented in the text. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test performed on AUC data.

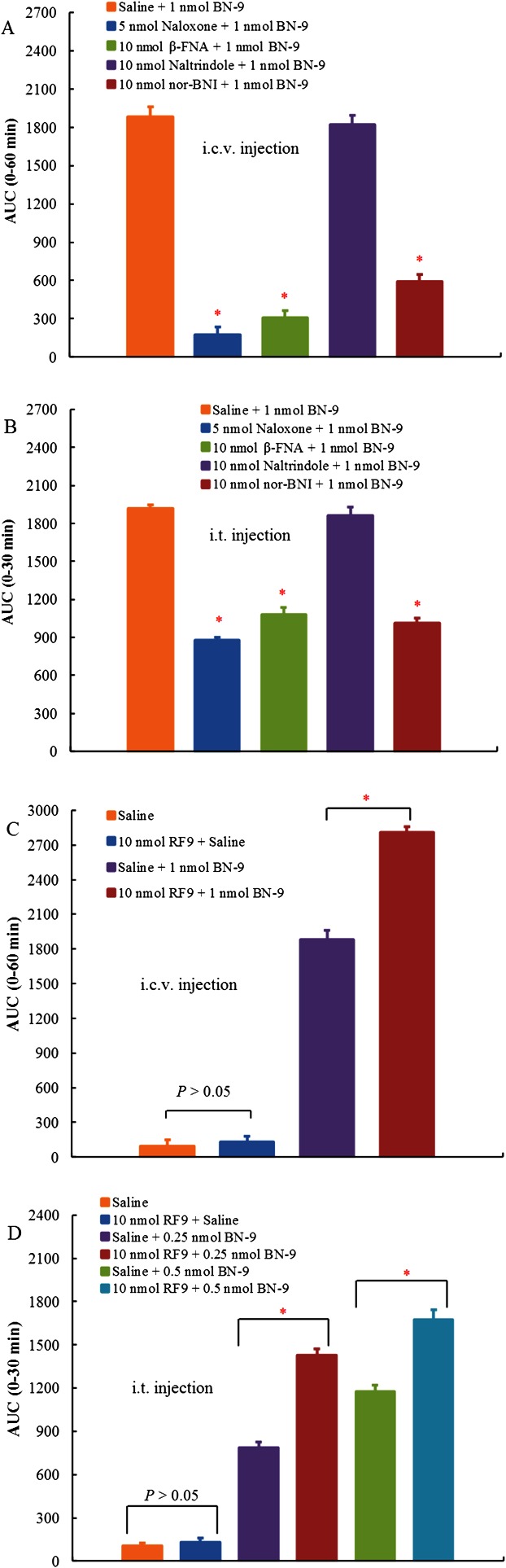

Furthermore, to characterize the central antinociception of BN‐9, antagonists of opioid and NPFF receptors were further used in the present study. As shown in Figure 6A, pretreatment with the classical opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (5 nmol, i.c.v.) completely blocked the supraspinal antinociception induced by BN‐9. In addition, the antinociception of BN‐9 was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with the selective μ receptor antagonist β‐FNA (10 nmol, i.c.v.) or the selective κ receptor antagonist nor‐BNI (10 nmol, i.c.v.) (F 4,39 = 165.6, P < 0.05), but not by the selective δ receptor antagonist naltrindole (10 nmol, i.c.v.) (P > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Antagonism of BN‐9‐induced supraspinal (i.c.v., A) or spinal (i.t., B) antinociception using various opioid antagonists. The effects of naloxone (5 nmol), β‐FNA (10 nmol), naltrindole (10 nmol) and nor‐BNI (10 nmol) on the central antinociception produced by BN‐9 were investigated in the mouse tail‐flick test. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on eight mice. Effects of the NPFF receptor antagonist RF9 on the BN‐9‐induced supraspinal (i.c.v., C) or spinal (i.t., D) antinociceptionin in the mouse tail‐flick test. RF9 enhanced the central antinociception produced by BN‐9 after i.c.v. or i.t. injection. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. Final group sizes: (C) n = 8; (D) saline: n = 7, 10 nmol RF9 + saline: n = 7, saline +0.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, 10 nmol RF9 + 0.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 7, saline +0.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 10 nmol RF9 + 0.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8. AUC calculated during 0–60 or 0–30 min from these data are used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05 versus Saline + BN‐9‐injected group, according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni's post hoc test performed on AUC data.

Similarly, pretreatment with naloxone (5 nmol, i.t.), β‐FNA (10 nmol, i.t.) and nor‐BNI (10 nmol, i.t.) significantly reduced the spinal antinociception of BN‐9 (F 4,39 = 132.9, P < 0.05). However, naltrindole (10 nmol, i.t.) had no significant effect on the BN‐9‐induced antinociception at the spinal cord level. In addition, at the same doses, these antagonists alone did not modify the tail‐flick latency in mice (data not shown). Thus, these data suggested that the antinociceptive activity of BN‐9 was mediated by μ and κ receptors but was independent of δ receptors.

The effect of the selective NPFF receptors antagonist RF9 on the central antinociception induced by BN‐9 is shown in Figure 6. Centrally administrated 10 nmol of RF9 alone did not modify the tail‐flick latency in mice. However, pretreatment with RF9 (10 nmol) significantly potentiated the antinociception of BN‐9 at the supraspinal (F 3,31 = 523.1, P < 0.05) and spinal (F 5,45 = 218.0, P < 0.05) levels. Because of the anti‐opioid action of the NPFF system, this finding further supports an NPFF‐mediated agonism of BN‐9 and its anti‐opioid character.

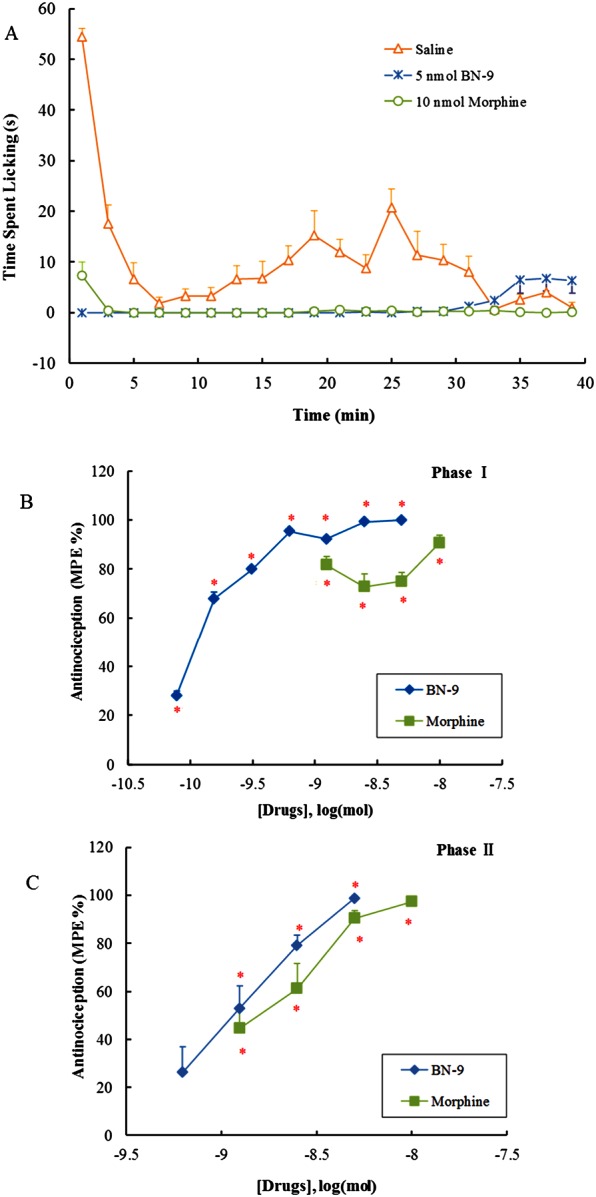

The antinociceptive effect of BN‐9 was further evaluated in an inflammatory pain model. As expected, formalin caused significant flinching behaviours in both phases I and II of the formalin test. In Figure 7A, 5 nmol of BN‐9 (i.c.v.) and 10 nmol of morphine (i.c.v.) produced equivalent antinociception in the formalin test in mice. In the mouse formalin test, the baseline value (time spent on biting injection paw) obtained was 116.6 ± 7.9 s in phase І (0–5 min). Compared with the saline group, i.c.v. administered BN‐9 (0.078, 0.156, 0.313, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5 and 5 nmol) and morphine (1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 nmol) markedly decreased the nociceptive responses (F 7,65 = 115.8, P < 0.05; F 4,40 = 60.4, P < 0.05, respectively). The baseline value obtained from saline + vehicle‐treated mice was 180.3 ± 16.8 s in phase ІІ (15–30 min). As shown in Figure 7C, both BN‐9 (0.625, 1.25, 2.5 and 5 nmol, i.c.v.) and morphine (1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 nmol, i.c.v.) resulted in a dose‐dependent suppression of pain behaviour relative to control mice in the second phase of the behavioural response to formalin (F 4,39 = 25.0, P < 0.05; F 4,40 = 31.4, P < 0.05, respectively). Calculated ED50 values were 1.14 nmol for BN‐9 and 1.57 nmol for morphine in phase ІІ. According to the antinociceptive dose–response curves, BN‐9 was more potent than morphine in the mouse formalin test (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Antinociceptive effects of i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 or morphine in the mouse formalin test. (A) Time‐response cure for the antiniciception induced by 5 nmol BN‐9 and 10 nmol morphine after i.c.v. injection. The total time of licking and flinching /shaking the injected paw was recorded during the first 1 min of each interval after formalin injection. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on eight mice. Antinociceptive dose–response curves for i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 or morphine in phase I (B) and phase II (C). The cumulative response time of licking and flinching/shaking the injected paw was measured during the period of 0–5 min (phase I) and 15–30 min (phase II). Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. Final group sizes: (C) 0.078 nmol BN‐9: n = 9, 0.156 nmol BN‐9: n = 9, 0.313 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 0.625 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 1.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 2.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 1.25 nmol morphine: n = 7, 2.5 nmol morphine: n = 8, 5 nmol morphine: n = 10, 10 nmol morphine: n = 8; (D) 0.625 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 1.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 2.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 5 nmol BN‐9: n = 8, 1.25 nmol morphine: n = 7, 2.5 nmol morphine: n = 8, 5 nmol morphine: n = 10, 10 nmol morphine: n = 8. *P < .05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test.

In addition, the metabolic stability of BN‐9 was examined by incubation of BN‐9 in the mouse brain homogenate in a time course fashion. Our results indicated that BN‐9 disappeared with a half‐life of 42.43 ± 6.03 min in the brain membrane homogenate. The result is representative of four independent experiments.

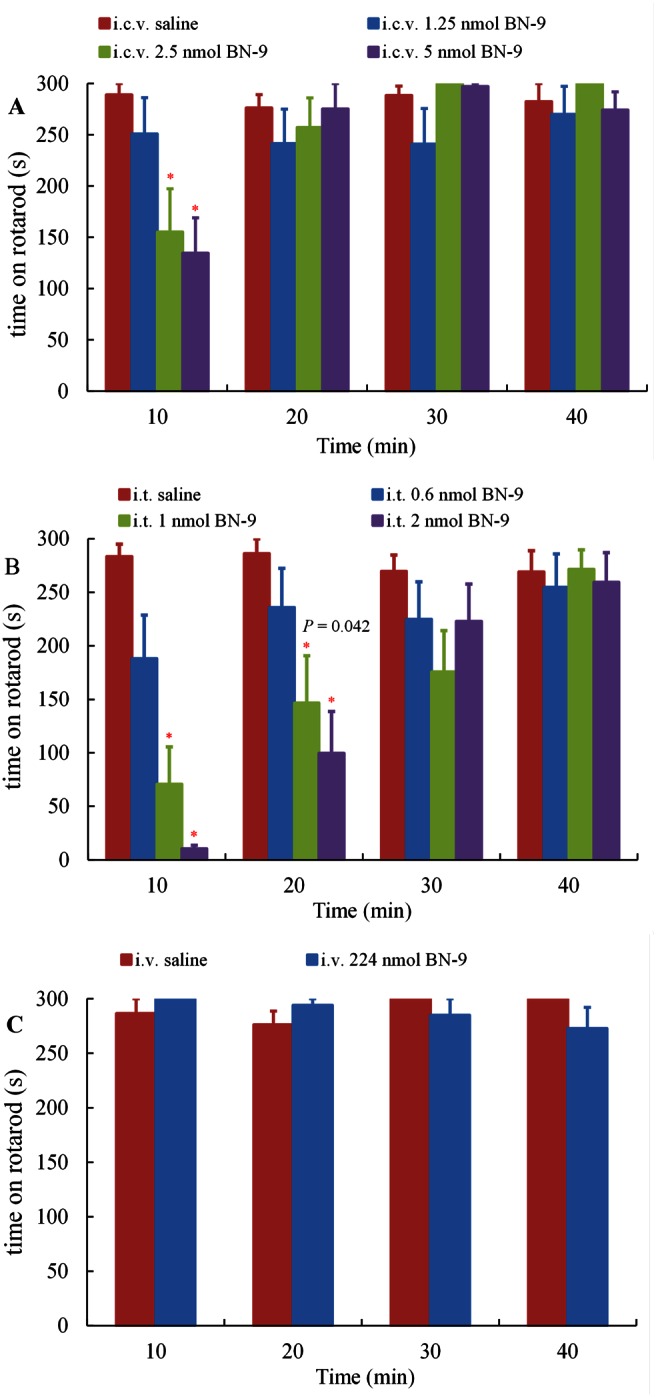

Motor impairment evaluation of BN‐9

We evaluated the motor performance of mice following the administration of BN‐9 in the rotarod test. As shown in Figure 8A, the endurance time on the rotating rod was not significantly affected by i.c.v. administration of 1.25 nmol BN‐9. At the higher doses of 2.5 and 5 nmol, BN‐9 significantly inhibited motor function at 10 min postinjection after i.c.v. administration (F 3,40 = 6.55, P < 0.05). Furthermore, i.t. administration of 0.6 nmol BN‐9 did not significantly affect motor function (Figure 8B). However, at the higher dose of 1 and 2 nmol, spinal administration of BN‐9 significantly decreased the endurance time at 10 and 20 min postinjection (F 3,39 = 17.37, P < 0.05; F 3,39 = 4.77, P < 0.05, respectively). As shown in Figure 8C, at a high dose of 224 nmol, systemic injection of BN‐9 did not decrease the endurance time in mice.

Figure 8.

Effect of supraspinal (A, i.c.v.), spinal (B, i.t.) and systemic (C, i.v.) administrations of BN‐9 on the motor performance of mice in the rotarod test. The mean time (s) mice remained on the rotarod was measured 40 min after the administration of BN‐9 or vehicle. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least eight mice. Final group sizes: (A) saline: n = 10, 1.25 nmol BN‐9: n = 9, 2.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 11, 5 nmol BN‐9: n = 11; (B) saline: n = 8, 0.6 nmol BN‐9: n = 10, 1 nmol BN‐9: n = 11, 2 nmol BN‐9: n = 11; (C) saline: n = 11, 224 nmol BN‐9: n = 11. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test.

Tolerance evaluation of BN‐9

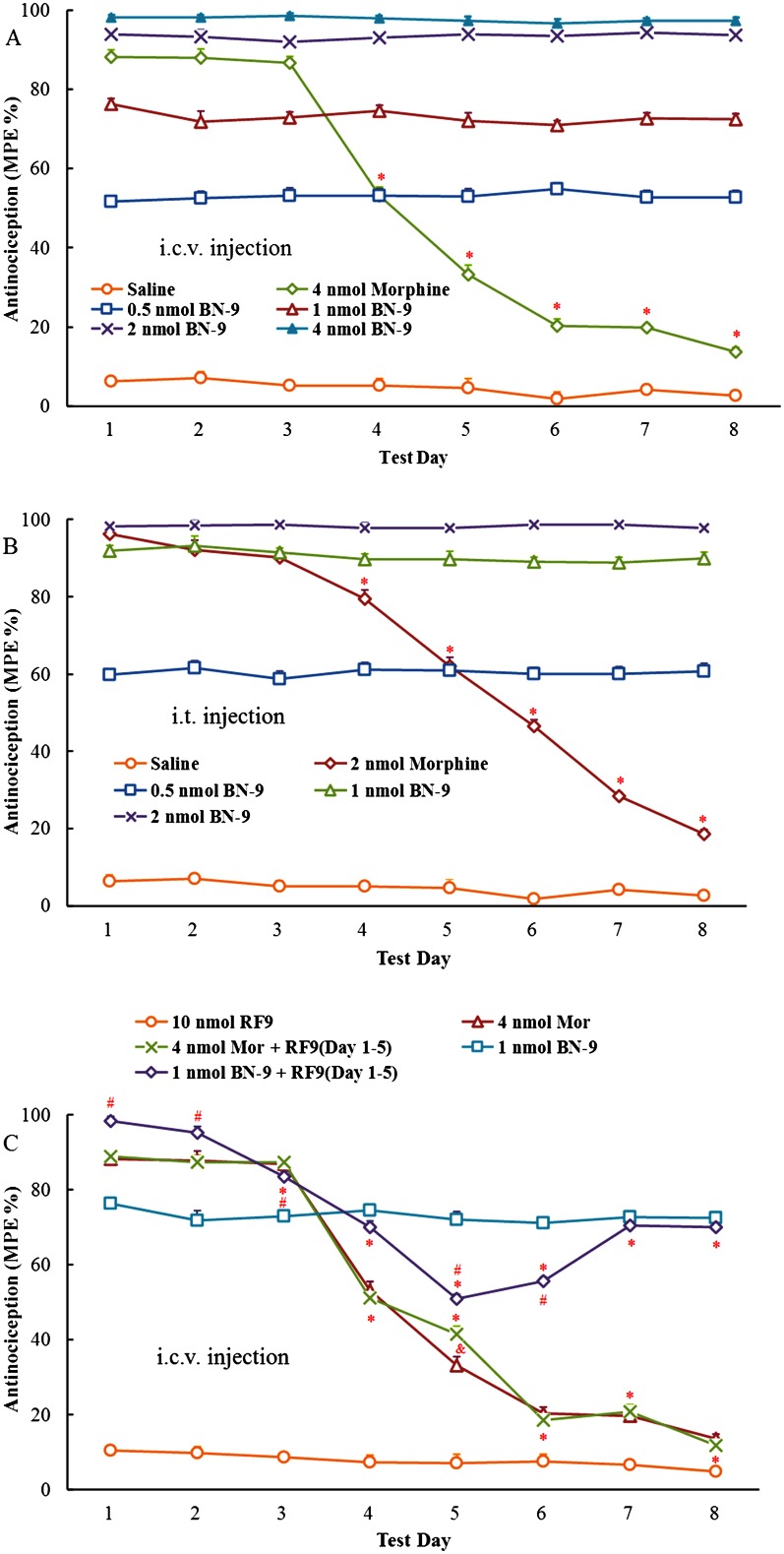

The effects of BN‐9 and the reference compound morphine on central antinociception across repeated test days are shown in Figure 9. Compared with day 1, the % MPE of morphine reduced significantly on the test day 4 and reduced to 13.6 ± 1.3 (i.c.v.) or 18.5 ± 1.3 (i.t.) of % MPE on the test day 8, respectively (F 7, 63 = 595.7, P < 0.05; F 7, 63 = 260.9, P < 0.05, respectively), demonstrating tolerance developed to morphine at the supraspinal and spinal cord levels. In contrast, all doses of BN‐9 produced equivalent antinociceptive effects over 8 days course of i.c.v. or i.t. administration. However, saline alone had no effect on analgesia.

Figure 9.

Antinociceptive tolerance studies of BN‐9. Saline, morphine and BN‐9 were repeatedly administered daily i.c.v. (A) or i.t. (B) for 8 days in mice before the mouse tail‐flick test was performed. Ordinate values represent the daily analgesic response, expressed as MPE % [saline and BN‐9 at 15 min (i.c.v., A) or 10 min (i.t., B); morphine at 30 min (i.c.v., A) or 10 min (i.t., B)], after the injection. Data points represent mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on eight mice. Tolerance began to develop to the analgesic effects of morphine on day 4. *P < 0.05 versus effect of morphine on day 1, according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Tukey's HSD post hoc test. (C) Effects of i.c.v. RF9 on the development of tolerance to antinociception of morphine or BN‐9. RF9 (10 nmol), a selective NPFF receptor antagonist, was i.c.v. co‐injected with morphine (4 nmol) or BN‐9 (1 nmol) for 5 days. On days 6–8, no RF9 was given. Ten nanomole RF9 was i.c.v. administered alone for 8 days as a control. Ordinatevalues represent the daily analgesic response, expressed as MPE % [saline and BN‐9 at 15 min; morphine at 30 min], after the injection. Data points represent mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least seven mice. Final group sizes: 10 nmol RF9: n = 7, 4 nmol morphine: n = 8, 4 nmol morphine + RF9 (Days 1–5): n = 8, 1 nmol BN‐9: n = 11, 1 nmol BN‐9 + RF9(Day 1–5): n = 11. * P < 0.05 versus effect on day 1, according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Tukey HSD's post hoc test. & P < 0.05 versus effect of morphine, according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni's post hoc test. # P < 0.05 versus effect of BN‐9, according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni's post hoc test.

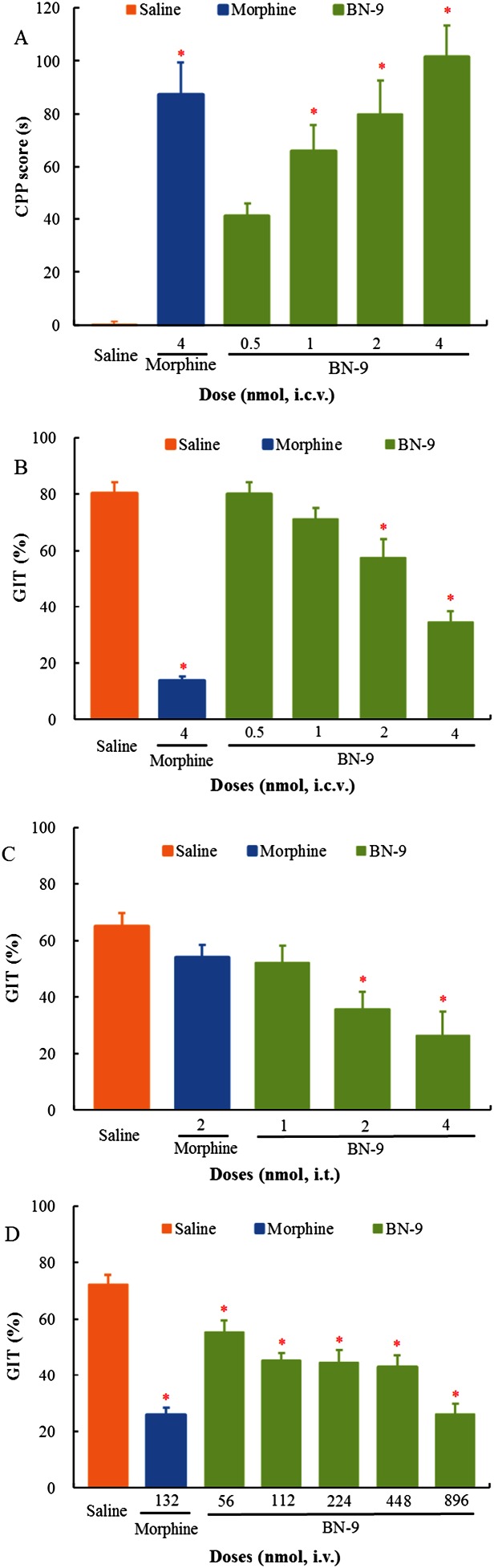

Figure 10.

Evaluation of side effects of BN‐9. (A) The effects of i.c.v. administration of morphine or BN‐9 alone on place conditioning in mice. CPP score is expressed as time spent in the drug‐associated compartment on the post‐conditioning day minus time spent in the drug‐associated compartment during a period of 15 min on the pre‐conditioning day. Data are expressed as CPP score, that is, time spent in drug‐associated chamber on post‐conditioning day minus that on the pre‐conditioning day. Results are presented as mean ± SEM from experiments conducted on at least nine mice. Final group sizes: saline: n = 9, 4 nmol morphine: n = 9, 0.5 nmol BN‐9: n = 10, 1 nmol BN‐9: n = 10, 2 nmol BN‐9: n = 10, 4 nmol BN‐9: n = 0. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Tukey HSD test. The effects of supraspinal (B, i.c.v.), spinal (C, i.t.) and systemic (D, i.v.) administrations of morphine or BN‐9 on gastrointestinal transit in mice. Data points represent means ± SEM from experiments conducted on nine mice. *P < 0.05 versus saline according to one‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test.

Furthermore, the role of NPFF receptors in the nontolerance‐forming antinociception of BN‐9 was investigated at the supraspinal level. As shown in Figure 9C, the selective antagonist of NPFF receptors RF9 alone induced no significant antinociception over the test days. As expected, tolerance developed to 4 nmol morphine on day 4. Compared with morphine alone, morphine administered in the presence of RF9 over the course of 5 days produced a significant increase in % MPE on day 5. On days 6–8, RF9 was not delivered and the morphine group in presence of RF9 pretreatment showed similar effects to that of morphine alone.

In line with the above results, BN‐9 administered in the presence of RF9 induced a significant increase in antinociception compared with BN‐9 alone on day 1. However, compared with day 1 (98.3 ± 1.1% MPE), the % MPE of the co‐administration of BN‐9 and RF9 was reduced significantly on the test day 3 and reduced to 50.9 ± 1.7 of % MPE on the test day 5 (F 7, 63 = 119.3, P < 0.05). On days 6–8, RF9 was not delivered, and analgesia effect of BN‐9 was gradually restored. And the BN‐9 groups in presence and absence of RF9 pretreatment showed similar levels of antinociception on days 7 and 8.

Other side‐effect evaluation of BN‐9

The effects of BN‐9 and the reference compound morphine on place conditioning are shown in Figure 10A. Saline given i.c.v. did not significantly induce the place preference change, indicating that central injections were not rewarding or aversive in an unbiased CPP paradigm. Similar to the morphine group, i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 dose‐dependently exerted CPP in mice (F 5,57 = 13.62, P < 0.05).

The effects of BN‐9 and morphine injected by the different routes on the gastrointestinal transit were also evaluated in mice. In Figure 10B, a supraspinal injection of 4 nmol morphine caused a marked decrease in the gastrointestinal transit motility compared with vehicle‐treated group. Furthermore, BN‐9 exerted a dose‐dependent decrease in gastrointestinal transit in mice (F 5 ,53 = 41.55, P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 10C, at the spinal level, 2 nmol morphine did not caused a significant effect in the gastrointestinal transit motility compared with saline‐treated group. However, BN‐9 exerted a dose‐dependent decrease in gastrointestinal transit in mice (F 4,44 = 6.23, P < 0.05). In addition, in Figure 10D, 132 nmol morphine (i.v.) caused a marked inhibition of GIT and BN‐9 (i.v.) exerted a dose‐dependent inhibitory effect on GIT compared with the saline treated group (F 6,61 = 20.76, P < 0.05). As shown in Table 2, BN‐9 had 8.69‐, 9.31 and 8.36‐fold differences in the ratio comparing the ED50 values for antinociception with the ED50 values for GIT inhibition when administered by the same routes (i.c.v., i.t. or i.v.) respectively.

Discussion and conclusions

In recent years, significant efforts to characterize ligands that have multiple activities to develop the novel opioid analgesics with reduced side effects are ongoing. Compared with drug combinations, bi‐ and multifunctional ligands have several advantages, including the simple and predictable absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion properties; the lower risk of drug–drug interactions; and the potential for a high local concentration of active components (Edwards and Aronson, 2000; Morphy and Rankovic, 2005; Schiller, 2010). There is evidence to indicate that the opioid ligands with mixed agonist/antagonist profiles have therapeutic potential as analgesics with reduced side effects (Bonini et al., 2000; Hinuma et al., 2000; Hruby et al., 2003; Khroyan et al., 2007; Ballet et al., 2008; Schiller, 2010; Kleczkowska et al., 2013). In the present work, we identified a novel multifunctional opioid peptide with mixed μ/δ/κ‐opioid agonist and NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptor agonist properties in the cAMP assays; it also produced potent antinociception with limited side effects.

In the tail‐flick tests, BN‐9 and the reference compound morphine dose‐dependently produced significant increases in tail‐flick latency after various routes of administration. The antinociceptive effects of BN‐9 and morphine are summarized in Table 2. At the supraspinal level, the antinociceptive potency of BN‐9 in the tail‐flick test was 2.61 times greater than that of i.c.v. morphine. Furthermore, our in vitro stability studies indicated that BN‐9 disappeared with a half‐life of 42.43 ± 6.03 min in the brain membrane homogenate, which is consistent with the data that BN‐9‐induced supraspinal antinociception was sustained for approximately 60 min. In addition, BN‐9 was found to elicit marked antinociception after spinal or systemic injection, with an i.t. or i.v. antinociceptive potency similar to that of morphine.

The antinociceptive responses to central administration of BN‐9 were blocked by the co‐administration of the classical opioid antagonist naloxone. Furthermore, the central antinociception of BN‐9 was significantly blocked by pretreatment with μ receptor antagonist β‐FNA and κ receptor antagonist nor‐BNI but not by the δ receptor antagonist naltrindole. These findings indicate that the central antinociception of BN‐9 was mainly mediated by both μ and κ receptors, supporting the μ and κ receptor agonism of BN‐9 in the in vitro functional assays.

Furthermore, the present results indicate that the central antinociceptive effects of BN‐9 were significantly augmented by the selective NPFF receptors antagonist RF9 at the supraspinal and spinal levels. Previously, a number of studies have shown that NPFF itself has no significant effect on nociceptive threshold but attenuates the central antinociception induced by endogenous or exogenous opioids after i.c.v. co‐administration (Roumy and Zajac, 1998; Fang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). In theory, BN‐9 containing both NPFF and opioid agonist activities could partially exert anti‐opioid activities of the NPFF moiety and reduce its antinociception after supraspinal administration. Thus, pretreatment with RF9 prevented the anti‐opioid activities of the NPFF moiety and potentiated the antinociception of i.c.v. BN‐9, implying the NPFF agonism of BN‐9. However, at the spinal level, NPFF and 1DMe were reported to potentiate morphine‐induced antinociception in previous studies (Gouarderes et al., 1993; Courteix et al., 1999; Altier et al., 2000). It is difficult to explain the conflicting findings about a potentiation of BN‐9 in spinal analgesia induced by RF9 at present. However, NPFF agonists have shown to exert different opioid‐modulating effects depending on their receptor selectivity, injection site and opioid activity (Roumy and Zajac, 1998; Mouledous et al., 2010). Thus, further pharmacological studies are required to prove the abovementioned discrepancy in the future.

In the present work, the antinociceptive activities of BN‐9 and morphine were evaluated in the formalin test. In general, hind paw formalin injection could induce two behavioural phases. The initial phase results from an acute nociceptive activity, and the subsequent phase is due to chronic spinal dorsal horn neuron hyperactivation. As expected, supraspinal administration of morphine dose‐dependently depressed both phase I and phase II flinching behaviours induced by formalin administration. Compared with morphine, i.c.v. injection of BN‐9 produced more potent analgesia in phase I and phase II. These results are consist with the data obtained from the tail‐flick test that BN‐9 was 2.62‐fold more potent than morphine after supraspinal injections.

Furthermore, the rotarod test was performed to assess the effect of BN‐9 on motor performance. Because opioid agonists were reported to inhibit motor performance (Sutters et al., 1990; Miaskowski and Levine, 1992; Gallantine and Meert, 2008; Tsubahara‐Ohsumi et al., 2011), in theory, BN‐9 may also affect the motor function. In the present study, at the higher doses (2.5 and 5 nmol), BN‐9 interfered with motor function up to 10 min after i.c.v. administration. In contrast, the analgesic effect of 2 nmol BN‐9 (i.c.v.) in the tail‐flick assays lasted for 60 min. Additionally, supraspinal injection of 2.5 nmol BN‐9 reduced the behavioural response to formalin in phase II. Hence, the high doses of BN‐9 might inhibit motor function for a short period. In addition, BN‐9 displayed no influence on motor function at a dose of 1.25 nmol, the dose at which it produces significant antinociception after supraspinal administration. Therefore, the dose of BN‐9 that causes analgesia is clinically relevant. Similarly, at the spinal level, 1 and 2 nmol BN‐9 also significantly inhibited motor performance at 10 and 20 min postinjection, whereas 0.6 nmol BN‐9 had no influence on motor function. It is notable that systemic administration of BN‐9 did not modify the endurance time at the high dose.

Opioid analgesics have an undesirable propensity to induce antinociceptive tolerance. Clinically, patients often receive escalating doses of opioid drugs to maintain the effective analgesia. The present results demonstrated that repeated administration of BN‐9 produced analgesia without loss of potency over 8 days, suggesting that coincident activation of opioid and NPFF receptors by BN‐9 maintains opioid‐induced antinociception over time. Further investigations indicated that BN‐9 produced a progressive loss of analgesic potency and tolerance development over 5 days, when co‐injected with the NPFF receptor antagonist RF9. Subsequently, a time‐dependent return of BN‐9 antinociception was observed from days 6 to 8 after removal of RF9. These findings imply the important role of the activation of NPFF receptors in delaying opioid tolerance development to BN‐9. Indeed, previous studies have shown that both an antagonist (RF9) and agonist (AC‐263093) of NPFF receptors decrease morphine tolerance to antinociception (Simonin et al., 2006; Elhabazi et al., 2012; Malin et al., 2015). These conflicting results highlight the complicated relationship between NPFF receptor activation and opioid‐mediated tolerance.

In previous studies, NPFF and its stable agonist 1DMe were reported to reduce the acquisition and expression of the CPP of morphine (Marchand et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010). Thus, we had hypothesized that BN‐9, which contains both opioid and NPFF agonist activities, would attenuate the CPP induced by its opioid moiety. However, the present findings indicated that BN‐9 produced potent, dose‐related CPP in a manner similar to morphine. It is notable that 1DMe was i.c.v. injected 10 min before the systemic administration of morphine during conditioning, and inhibited the opioid rewarding effect in the previous studies (Marchand et al., 2006). Compared with the combinations of 1DMe and morphine, BN‐9 had different pharmacokinetic and distribution patterns, which might result in the different activities in rewarding studies.

The constipation associated with μ receptor agonists has complicated the use of opioids for the control of acute and chronic pain. The present GI transit data demonstrated that BN‐9 produced little inhibition of GI transit. At the supraspinal and systemic level, BN‐9 had a more than 8‐fold higher ED50 value for GI inhibition compare with the ED50 values for antinociception. Furthermore, BN‐9 was 9.3‐fold more potent at inducing analgesia compared to GI inhibition when administered by the spinal route. Previous studies have revealed that NPFF could act centrally to inhibit intestinal transit in mice, independently of the opioid system (Gicquel et al., 1993). In addition, the NPFF agonist 1DMe had no effects on morphine‐induced inhibition of intestinal transit, whereas an ineffective dose of morphine attenuated 1DMe‐induced inhibition of intestinal transit (Gicquel et al., 1993). These findings may partially explain why BN‐9 with mixed opioid and NPFF receptors agonistic properties can produce limited inhibition of GI transit.

In summary, the body of data derived from our present studies provides, for the first time, a novel multifunctional agonist at μ, δ, κ, NPFF1 and NPFF2 receptors, designated BN‐9. BN‐9 has potent antinociceptive activities through μ and κ receptor‐mediated mechanisms. Interestingly, repeated administration of BN‐9 produces opioid‐dependent analgesia without loss of potency over 8 days, which results from the coincidental coactivation of opioid and NPFF receptors. Additionally, BN‐9 had a more than 8‐fold difference in the ratio of ED50 values for antinociception compared to the ED50 values for GI inhibition when administered by the same routes. However, BN‐9 induces CPP, suggesting that the NPFF receptor‐mediated component cannot decrease the reward induced by the opioid receptor activity. It is worthy of note that BN‐9 represents a valuable ligand to investigate the interactions between the opioid and NPFF systems because of its coactivation of opioid and NPFF receptors. In theory, a chimeric opioid/NPFF peptide with a different functional balance between opioid and NPFF receptor stimulation will exert different pharmacological profiles. It is possible that a multifunctional ligand, which favours NPFF versus μ receptor‐mediated agonistic activity may produce analgesia with limited side effects. Chimeric peptides with mixed opioid and NPFF agonisms are currently being investigated in ongoing studies in our laboratory. It is expected that the multifunctional peptides developed will become attractive analgesics of the future, especially as new technologies become available for enhancing the penetration of peptides into the CNS.

Author contributions

N.L., Z.H., Z.W., Y.X., Y.S., X.L., T.Z., R.Z., M.Z. and B.X. performed the research. Q.F. and R.W. designed the research study. Y.X., Y.S. and J.S. contributed essential reagents or tools. Q.F., N.L. and Z.H. analysed the data. Q.F. and R.W. wrote the paper. Both N.L. and Z.H. contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81273355, 81473095), the Key National S&T Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology (2012ZX09504001‐003), New Century Excellent Talents (NCET‐13‐0257) in University and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky‐2014‐k02).

Li, N. , Han, Z.‐l. , Wang, Z.‐l. , Xing, Y.‐h. , Sun, Y.‐l. , Li, X.‐h. , Song, J.‐j. , Zhang, T. , Zhang, R. , Zhang, M.‐n. , Xu, B. , Fang, Q. , and Wang, R. (2016) BN‐9, a chimeric peptide with mixed opioid and neuropeptide FF receptor agonistic properties, produces nontolerance‐forming antinociception in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 1864–1880. doi: 10.1111/bph.13489.

References

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015). The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier N, Dray A, Menard D, Henry JL (2000). Neuropeptide FF attenuates allodynia in models of chronic inflammation and neuropathy following intrathecal or intracerebroventricular administration. Eur J Pharmacol 407: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballet S, Pietsch M, Abell AD (2008). Multiple ligands in opioid research. Protein Pept Lett 15: 668–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini JA, Jones KA, Adham N, Forray C, Artymyshyn R, Durkin MM et al. (2000). Identification and characterization of two G protein‐coupled receptors for neuropeptide FF. J Biol Chem 275: 39324–39331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courteix C, Coudore‐Civiale MA, Privat AM, Zajac JM, Eschalier A, Fialip J (1999). Spinal effect of a neuropeptide FF analogue on hyperalgesia and morphine‐induced analgesia in mononeuropathic and diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol 127: 1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards IR, Aronson JK (2000). Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 356: 1255–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhabazi K, Trigo JM, Mollereau C, Mouledous L, Zajac JM, Bihel F et al. (2012). Involvement of neuropeptide FF receptors in neuroadaptive responses to acute and chronic opiate treatments. Br J Pharmacol 165: 424–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshourbagy NA, Ames RS, Fitzgerald LR, Foley JJ, Chambers JK, Szekeres PG et al. (2000). Receptor for the pain modulatory neuropeptides FF and AF is an orphan G protein‐coupled receptor. J Biol Chem 275: 25965–25971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks CA (2003). Spinal delivery of analgesics in experimental models of pain and analgesia. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 55: 1007–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Han ZL, Li N, Wang ZL, He N, Wang R (2012). Effects of neuropeptide FF system on CB1 and CB2 receptors mediated antinociception in mice. Neuropharmacology 62: 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Jiang TN, Li N, Han ZL, Wang R (2011). Central administration of neuropeptide FF and related peptides attenuate systemic morphine analgesia in mice. Protein Pept Lett 18: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran SE, Carr DB, Lipkowski AW, Maszczynska I, Marchand JE, Misicka A et al. (2000). A substance P‐opioid chimeric peptide as a unique nontolerance‐forming analgesic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 7621–7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallantine EL, Meert TF (2008). Antinociceptive and adverse effects of mu‐ and kappa‐opioid receptor agonists: a comparison of morphine and U50488‐H. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 103: 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gicquel S, Fioramonti J, Bueno L, Zajac JM (1993). Effects of F8Famide analogs on intestinal transit in mice. Peptides 14: 749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouarderes C, Sutak M, Zajac JM, Jhamandas K (1993). Antinociceptive effects of intrathecally administered F8Famide and FMRFamide in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 237: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusovsky F (2001). Measurement of second messengers in signal transduction: cAMP and inositol phosphates. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter 7: Unit7 12. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0712s05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZL, Fang Q, Wang ZL, Li XH, Li N, Chang XM et al. (2014). Antinociceptive effects of central administration of the endogenous cannabinoid receptor type 1 agonist VDPVNFKLLSH‐OH [(m)VD‐hemopressin(alpha)], an N‐terminally extended hemopressin peptide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 348: 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZL, Wang ZL, Tang HZ, Li N, Fang Q, Li XH et al. (2013). Neuropeptide FF attenuates the acquisition and the expression of conditioned place aversion to endomorphin‐2 in mice. Behav Brain Res 248: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinuma S, Shintani Y, Fukusumi S, Iijima N, Matsumoto Y, Hosoya M et al. (2000). New neuropeptides containing carboxy‐terminal RFamide and their receptor in mammals. Nat Cell Biol 2: 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan PJ, Mattia A, Bilsky EJ, Weber S, Davis TP, Yamamura HI et al. (1993). Antinociceptive profile of biphalin, a dimeric enkephalin analog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265: 1446–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby VJ, Agnes RS, Davis P, Ma SW, Lee YS, Vanderah TW et al. (2003). Design of novel peptide ligands which have opioid agonist activity and CCK antagonist activity for the treatment of pain. Life Sci 73: 699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden JL, Wilcox GL (1980). Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol 67: 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inturrisi CE (2002). Clinical pharmacology of opioids for pain. Clin J Pain 18: S3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Zaveri NT, Polgar WE, Orduna J, Olsen C, Jiang F et al. (2007). SR 16435 [1‐(1‐(bicyclo[3.3.1]nonan‐9‐yl)piperidin‐4‐yl)indolin‐2‐one], a novel mixed nociceptin/orphanin FQ/mu‐opioid receptor partial agonist: analgesic and rewarding properties in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320: 934–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 1: 94–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleczkowska P, Lipkowski AW, Tourwe D, Ballet S (2013). Hybrid opioid/non‐opioid ligands in pain research. Curr Pharm Des 19: 7435–7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontinen VK, Kalso EA (1995). Differential modulation of alpha 2‐adrenergic and mu‐opioid spinal antinociception by neuropeptide FF. Peptides 16: 973–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlinska J, Pachuta A, Dylag T, Silberring E (2007). Neuropeptide FF (NPFF) reduces the expression of morphine‐ but not of ethanol‐induced conditioned place preference in rats. Peptides 28: 2235–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largent‐Milnes TM, Yamamoto T, Nair P, Moulton JW, Hruby VJ, Lai J et al. (2010). Spinal or systemic TY005, a peptidic opioid agonist/neurokinin 1 antagonist, attenuates pain with reduced tolerance. Br J Pharmacol 161: 986–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Han ZL, Fang Q, Wang ZL, Tang HZ, Ren H et al. (2012). Neuropeptide FF and related peptides attenuates warm‐, but not cold‐water swim stress‐induced analgesia in mice. Behav Brain Res 233: 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Guan XM, Martin WJ, McDonald TP, Clements MK, Jiang Q et al. (2001). Identification and characterization of novel mammalian neuropeptide FF‐like peptides that attenuate morphine‐induced antinociception. J Biol Chem 276: 36961–36969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Henceroth MM, Izygon JJ, Nghiem DM, Moon WD, Anderson AP et al. (2015). Reversal of morphine tolerance by a compound with NPFF receptor subtype‐selective actions. Neurosci Lett 584: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand S, Betourne A, Marty V, Daumas S, Halley H, Lassalle JM et al. (2006). A neuropeptide FF agonist blocks the acquisition of conditioned place preference to morphine in C57Bl/6 J mice. Peptides 27: 964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Levine JD (1992). Antinociception produced by receptor selective opioids: modulation of spinal antinociceptive effects by supraspinal opioids. Brain Res 595: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollereau C, Roumy M, Zajac JM (2005). Opioid‐modulating peptides: Mechanisms of action. Curr Top Med Chem 5: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphy R, Rankovic Z (2005). Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J Med Chem 48: 6523–6543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouledous L, Mollereau C, Zajac JM (2010). Opioid‐modulating properties of the neuropeptide FF system. Biofactors 36: 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panula P, Kalso E, Nieminen M, Kontinen VK, Brandt A, Pertovaara A (1999). Neuropeptide FF and modulation of pain. Brain Res 848: 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SPH, Buneman OP et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D1098–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SJ, Yi‐Kung Huang E, Cronk D, Bagust J, Sharma R, Walker RJ et al. (1997). A human gene encoding morphine modulating peptides related to NPFF and FMRFamide. FEBS Lett 409: 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy RK, Ahmed E (2014). Principles of opioid use in cancer pain. J Clin Oncol 32: 1662–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumy M, Zajac JM (1998). Neuropeptide FF, pain and analgesia. Eur J Pharmacol 345: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller PW (2010). Bi‐ or multifunctional opioid peptide drugs. Life Sci 86: 598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonin F, Schmitt M, Laulin JP, Laboureyras E, Jhamandas JH, MacTavish D et al. (2006). RF9, a potent and selective neuropeptide FF receptor antagonist, prevents opioid‐induced tolerance associated with hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 466–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C (2013). Opioids, sensory systems and chronic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 716: 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutters KA, Miaskowski C, Taiwo YO, Levine JD (1990). Analgesic synergy and improved motor function produced by combinations of mu‐delta‐ and mu‐kappa‐opioids. Brain Res 530: 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubahara‐Ohsumi Y, Tsuji F, Niwa M, Hata T, Narita M, Suzuki T et al. (2011). The kappa opioid receptor agonist SA14867 has antinociceptive and weak sedative effects in models of acute and chronic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 671: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderah TW, Schteingart CD, Trojnar J, Junien JL, Lai J, Riviere PJ (2004). FE200041 (D‐Phe‐D‐Phe‐D‐Nle‐D‐Arg‐NH2): a peripheral efficacious kappa opioid agonist with unprecedented selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilim FS, Aarnisalo AA, Nieminen ML, Lintunen M, Karlstedt K, Kontinen VK et al. (1999). Gene for pain modulatory neuropeptide NPFF: induction in spinal cord by noxious stimuli. Mol Pharmacol 55: 804–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xing Y, Liu X, Ji H, Kai M, Chen Z et al. (2012). A new class of highly potent and selective endomorphin‐1 analogues containing alpha‐methylene‐beta‐aminopropanoic acids (map). J Med Chem 55: 6224–6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZL, Fang Q, Han ZL, Pan JX, Li XH, Li N et al. (2014). Opposite effects of neuropeptide FF on central antinociception induced by endomorphin‐1 and endomorphin‐2 in mice. PLoS One 9 : e103773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Tao PL, Huang EY (2010). Distribution of neuropeptide FF (NPFF) receptors in correlation with morphine‐induced reward in the rat brain. Peptides 31: 1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nair P, Ma SW, Davis P, Yamamura HI, Vanderah TW et al. (2009). The biological activity and metabolic stability of peptidic bifunctional compounds that are opioid receptor agonists and neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists with a cystine moiety. Bioorg Med Chem 17: 7337–7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HY, Fratta W, Majane EA, Costa E (1985). Isolation, sequencing, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of two brain neuropeptides that modulate the action of morphine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82: 7757–7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollner C, Stein C (2007). Opioids. Handb Exp Pharmacol 177: 31–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]