Abstract

The neonatal, infant, child, and maternal mortality rates in Haiti are the highest in the Western Hemisphere, with rates similar to those found in Afghanistan and several African countries. We identify several factors that have perpetuated this health care crisis and summarize the literature highlighting the most cost-effective, evidence-based interventions proved to decrease these mortality rates in low- and middle-income countries.

To create a major change in Haiti’s health care infrastructure, we are implementing two strategies that are unique for low-income countries: development of a countrywide network of geographic “community care grids” to facilitate implementation of frontline interventions, and the construction of a centrally located referral and teaching hospital to provide specialty care for communities throughout the country. This hospital strategy will leverage the proximity of Haiti to North America by mobilizing large numbers of North American medical volunteers to provide one-on-one mentoring for the Haitian medical staff. The first phase of this strategy will address the child and maternal health crisis.

We have begun implementation of these evidence-based strategies that we believe will fast-track improvement in the child and maternal mortality rates throughout the country. We anticipate that, as we partner with private and public groups already working in Haiti, one day Haiti’s health care system will be among the leaders in that region.

INTRODUCTION: THE HAITI CRISIS

Child and Maternal Mortality Rates

The World Health Organization (WHO), US Agency for International Development, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and other international agencies have published several years of annual child, neonatal, and maternal (CNM) mortality rates for countries around the world. Although the rates and annual trends are important in understanding the extent of a country’s problems, a comparison of the results with regional countries adds valuable information to the understanding of the magnitude of a crisis. This is especially true when one compares Haiti’s mortality rates with those of other countries in the Caribbean.

According to UNICEF, Haiti has the highest mortality rates for infants, children under age 5 years, and pregnant women in the Western Hemisphere.1 (For an explanation of terms, see Sidebar: Definitions.) There were an estimated 265,000 live births in Haiti in 2013,2 underscoring the magnitude of the number of deaths in each CNM category per year.

Definitions.

| Child: Child younger than age five years. |

| Infant: The first year of life. |

| Maternal mortality: Death of women while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.1 |

| Maternal mortality ratio: The ratio of the number of maternal deaths during a specific period per 100,000 live births during the same reference time.2 |

| Neonatal: The first four weeks of life. |

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births) [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/indmaternalmortality/en/.

Millennium development goal indicators: maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births [Internet]. New York, NY: United Nations Development Indicators Unit; updated 2014 Jul [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Metadata.aspx?IndicatorId=0&SeriesId=553.

Neonatal Mortality Rate

In Haiti, of all the deaths of children under 5 years of age, 34% died in the neonatal period, with approximately 90% of these deaths occurring in the first week of life.3 In 2013, there were an estimated 6800 neonatal deaths in Haiti on the basis of a neonatal mortality rate of 25 per 1000 live births, which was unchanged since 2010.1,3 This rate is much higher than the annual mortality rate in other Caribbean countries, including the Dominican Republic’s rate of 16 per 1000.4

Infant Mortality Rate

Haiti’s infant mortality rate was 55 per 1000 live births in 2013,1,4 which means that 75% of childhood deaths occur before a child’s first birthday. This rate was at least twice any other Caribbean country and much higher than the neighboring country, the Dominican Republic (21/1000). Haiti’s infant mortality rate is most certainly the highest in the Western Hemisphere,2 and is more in line with the 2013 reported rates of Liberia (54/1000) and Ghana (53/1000).4

Child Mortality Rate

In 2013 there were more than 20,000 deaths in children under age 5 years.2 The child mortality rate in Haiti in 2013 was 73 per 1000 compared with other Caribbean countries, which had an average rate of 15.2,5 Of the 75% of childhood deaths that occur before the first year of age, 34% occur during the neonatal period; the remaining 25% of childhood deaths occur between the first and fifth birthdays.6

Maternal Mortality Ratio

In 2013, the maternal mortality ratio in Haiti was 380 per 100,000 live births, with more than 1000 maternal deaths; this ratio was, unfortunately, not greatly different from the 2010 mortality ratio of 350.5 The ratio of 380 was much higher than the average of regional Caribbean countries (68) and similar to the rates of Rwanda (320), Sudan (360), and Afghanistan (400).5

Causes of Child, Neonatal, and Maternal Deaths

To determine the most appropriate interventions to confront this crisis, it is important for us to first understand the various contributing factors to these unacceptably high mortality rates in Haiti. A literature review of the various causes of the CNM mortality in low- and middle-income countries suggests that multiple factors usually contribute to the mortality rates. Overall, the diseases listed are almost universally preventable and treatable, and the causative situations are generally correctable.

Poverty

One reason may seem obvious: poverty.6 Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world.5 Although the factors contributing to the high CNM death rates in Haiti are complex, it will become apparent that poverty is a contributing factor for each specific cause as they are assessed. The effect of poverty is best illustrated by contrasting Haiti and the Dominican Republic, two countries sharing the same island with populations of similar sizes. As mentioned earlier, all the CNM mortality rates are much lower in the Dominican Republic than in Haiti. Almost as dramatic is the comparison of the economic measures of both countries, in which the Dominican Republic has one of the most robust economies in the region as opposed to Haiti, which is at the bottom of the scale.5

Neonatal and Infant Causes

According to the WHO, more than 80% of all global neonatal deaths are caused by preterm birth complications, newborn infections, and birth asphyxia.4,7 Complications arising from preterm births are now the leading cause of neonatal mortality worldwide. In 2012, prematurity was a cause in 17% of childhood deaths under 5 years old and in approximately 35% of all neonatal deaths.8 Haiti’s preterm birth rate in 2010 was 14.1%, ranking it 19th among countries with the highest preterm birth rates, similar to Bangladesh and Liberia. During the same period, the Dominican Republic’s preterm birth rate was 10.8%, ranking it much lower (79th) among all countries.9 We are not aware of any Haitian neonatal mortality data based on gestational age.

The WHO has defined low birth weight as the weight at birth of less than 2500 g (5.5 lb).10 Infants weighing less than 2500 g are approximately 20 times more likely to die than heavier babies.9 In Haiti, the average percentage of low-birth-weight infants in 2008 to 2012 was 23%, and during the same period in the Dominican Republic the percentage of low birth weight was 11%. These percentages from both countries were unchanged from 2000 assessments.1

In low- and middle-income countries, the major contributors to the death of infants from 28 days to 1 year are birth asphyxia, injuries, low birth weight, malnutrition, infectious diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and poor home sanitation.11 These occur more often in children born in remote rural areas or in poor households, or to a mother with limited education. These demographic factors result in children who are undernourished, have vitamin and iron deficiencies, and do not receive appropriate immunizations.12

Child Causes

Injuries are by far the most common cause (66%) of death in children aged 1 to 5 years, followed by pneumonia (11%) and diarrheal diseases (8%).4 The lack of availability of pneumonia treatment in Haiti is one explanation for children dying at such an appalling rate compared with other Caribbean countries.1,13 The percentage of children younger than age 5 years with suspected pneumonia taken to appropriate health care practitioners reached 31% in 2006 and 38% in 2012. The same year, only 46% of children younger than age 5 years with suspected pneumonia received antibiotics.

Maternal Causes

Most maternal deaths occur during childbirth and the first week post partum.14,15 Worldwide in low- and middle-income countries, 5 factors contribute to 80% of maternal deaths: heavy bleeding after birth, hypertension, infections, obstructed labor, and unsafe abortions.16

In 2013, the WHO published regional maternal mortality rates for the Caribbean,1 identifying the most common causes of maternal death as hemorrhage (23%) and hypertension (22%). However, the situation is different in Haiti, where the primary cause of maternal death is preeclamsia/eclampsia (37.5%), with hemorrhage the second cause (22%).6 In a WHO analysis, Bilano and associates17 studied 276,388 mothers and their infants in low- and middle-income countries to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia. They identified 3 major risk factors: chronic hypertension, obesity, and severe anemia (hemoglobin level < 7.0 g/dL). Although we are not aware of the overall rates of anemia in Haitian pregnant women, obesity rates are less than regional averages.1 However, Haitian women do have a significantly higher rate of high blood pressure compared with other Caribbean countries (33% vs 26.3% in 2008).1 This observation has obvious ramifications when determining which screening risk factors are used to lower maternal mortality in Haitian women.

Infectious Diseases

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), malaria, and tuberculosis are common infectious causes of child and maternal mortality in Haiti. According to UNICEF, infection with HIV is much more prevalent in Haiti than in other countries in the region.1 It estimates that 5.6% of Haitians aged 15 to 49 years, including about 19,000 children, live with HIV or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and antiretroviral drugs are in short stupply.1 In 2012, there were 78,000 women living in Haiti with HIV compared with 22,000 in the Dominican Republic.1 According to the CDC, 4330 HIV-positive pregnant women were identified in Haiti in 2012, and 83% had antiretroviral therapy initiated.18

Malaria in pregnancy contributes to substantial perinatal morbidity and mortality.19 Chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria is endemic in Haiti, resulting in a high rate of transmission.20,21 In Haiti in 2012, few households had insecticide-treated mosquito nets, with only an estimated 9% of pregnant women sleeping under a protective net.22

The incidence rate of tuberculosis in Haiti from 2010 to 2014 was 206 cases per 100,000, basically unchanged over the past decade. During the same timeframe, the incidence rate in the Dominican Republic was 60 per 100,000.23

Diabetes

The incidence of elevated blood glucose levels in Haitian women is low (9.6% in 2008) and is not statistically different from the regional average. 24

Tobacco

Tobacco use among Haitian women is negligible, 4.4% of adult women were smokers in 2011.25

Contributing Primary Factors

In addition to medical causes of CNM mortality, several other factors contribute to the inadequacies of the Haitian health care infrastructure. The following are six primary factors contributing to the CMN crisis in Haiti:

limited accessibility

inadequate health care facilities

inadequate number of trained health care practitioners

low percentage of skilled attendants at deliveries

low percentage of prenatal and postnatal visits

high-risk deliveries in nonqualified health facilities.

Limited Accessibility

It is important to understand Haiti’s demographics that contribute to the complexities of its child and maternal health care. The Sidebar: Haiti Demographics lists several pertinent Haiti demographics along with Caribbean countries’ comparisons when available. As noted in the Sidebar, the country is subdivided into ten administrative “departments” (provinces), each with its own capital city and health care infrastructure. When we refer to regional facilities in this article, we are generally referring to capabilities in one of these departments.

Haiti Demographics.

| Population: 10,573,000, with 2.3 million people (21%) living in the metropolitan area of the capital, Port-au-Prince.1 Overall, the population living in urban areas is 55% (regional average, 80%).2 |

| Size: Haiti’s 27,560 square km is approximately the size of Vermont, which has a population of 626,000.3 Haiti is the third largest country in the Caribbean; only the Dominican Republic and Cuba are larger. |

| Topography: Haiti is the most mountainous nation in the Caribbean. The main population density, Port-au-Prince, resides centrally in the valley between the north and south mountain ranges. |

| Administrative Division: The country is subdivided into 10 departments (provinces), each having a capital city. |

| Income: Haiti is a poor country, ranking 168 of 187 on the United Nations Human Development Index.4 |

| Transportation: More than half of the highways are unpaved. From Port-au-Prince, it takes approximately 4 hours to drive the 245 km to Cap-Haitian, a city on the northern coast of Haiti, and approximately 3 hours to drive the 200 km from Port-au-Prince to Les Cayes, a city to the south. There are 15 airports throughout the country, 10 of which are paved. The main international airport is located just outside and north of Port-au-Prince. Flying time from Miami is 1.5 hours and from Atlanta is less than 3 hours. |

World Population Data Sheet 2014 [Internet]. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2014 [cited 2015 17 Nov]. Available from: www.prb.org/Publications/Datasheets/2014/2014-world-population-data-sheet/world-map.aspx#map/world/population/2014.

Data: rural population (% of total population) [Internet]. New York, NY: The World Bank; 2015 [cited 17 Nov 2015]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS.

State & county quickfacts [Internet]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; revised 2015 Oct 14 [cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/50000.html.

Human development reports, Haiti [Internet]. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2014 [cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/HTI.

For improvements in child and maternal health to occur, all barriers that interfere with access to care need to be removed, including geographical isolation, financial barriers, and transportation limitations.

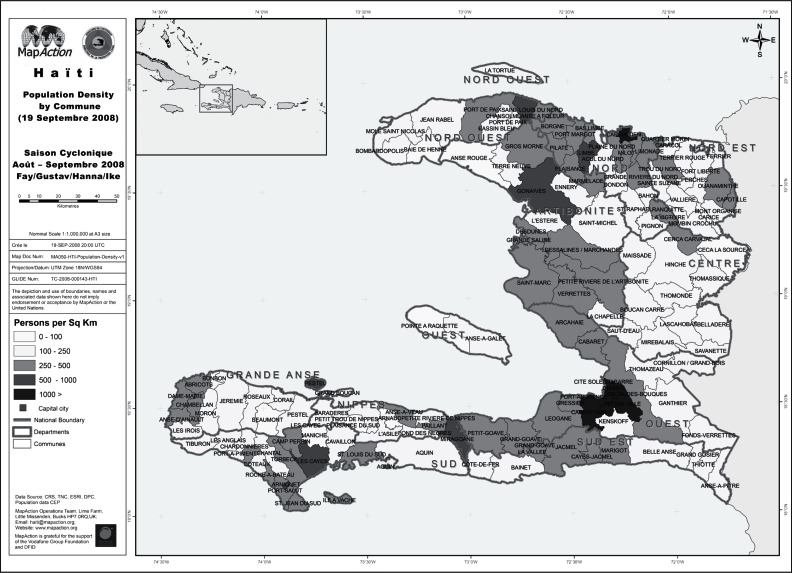

Geographical isolation: As reflected in the Sidebar: Haiti Demographics, a high percentage of the Haitian population lives in rural, mountainous areas accessible only by extremely poor roads. Figure 1 illustrates how widely the population is distributed. Approximately 45% of Haitians live in rural areas,1,25 as opposed to 30% of the Dominican Republic’s population residing in rural areas. Rural residents have limited access to basic health care and to qualified medical facilities.1 In rural areas in Haiti, less than half of the households have access to improved sources of drinking water, contrasted with 88% in urban areas. One-third of the households must travel 30 or more minutes to access drinking water.12 Also in rural areas, 38% of households have no toilet facilities compared with only 7% in urban areas.12 Only 11% of people in the Haitian countryside have access to energy compared with 63% in the country’s cities.26 Not surprisingly, UNICEF reports disparities of urban and rural populations for the prevalence of underweight children and diarrhea treatment.1 Children living in rural Haiti have a 46% greater chance of dying before their fifth birthday than their counterparts in urban areas.6

Figure 1.

Haiti population density map.

Map reprinted with kind permission from MapAction (www.mapaction.org).

Cost barrier: As noted earlier, poverty is a major contributing factor and most certainly adversely affects access. The evidence suggests that the financial barrier to health care is one of the most important obstacles for pregnant women needing access to obstetric care.12,27 In Haiti, 47% of the population lack access to health care primarily because of financial or geographic barriers, and 50% of households say they had not accessed health services when needed because of the high costs associated with services.27 If a pregnant woman cannot pay for a midwife or a physician, she will most likely be delivering the baby at home without any skilled assistance, resulting in the large number of births without a skilled attendant present as noted later in this section.12

Transportation: Motorized transport in rural areas of this mountainous country is almost nonexistent. Most roads are in poor condition, and only 5% of rural Haitians have access to a paved road.6

Inadequate Health Care Facilities

The earthquake of January 12, 2010, had terrible consequences for the Haitian society and for the Haitian health sector. Sixty percent of the Haitian state infrastructure was destroyed, including more than 50 health institutions with losses and damage in the health sector that exceeded 200% of annual expenditure in health from all sources.28

Even before the earthquake, the number and quality of health care facilities were inadequate to care for a population exceeding 10 million. Over the years, we have learned from our visits to hospitals that a major contributing factor for the CNM deaths in Haiti is a major shortage of neonatal, pediatric, and adult intensive care units. Probably no other observation underscores the poor condition of the Haiti health care system than the dire shortage of neonatal intensive care units. Despite the very high rates of prematurity, lifesaving neonatal care is almost completely unavailable to the vast number of babies needing intensive assistance, especially when they are born in rural Haiti.

Health Care Practitioners—Inadequate Numbers and Training

The health workforce has been identified as the key to effective health services because the shortage of health workers in developing countries is the most important constraint to attaining improvement in maternal health to reduce child mortality.29

In Haiti, there is a tremendous undersupply of physicians and other health professionals. The number of physicians, nurses, and midwives is 4 per 10,000 population, which is far below the WHO recommendation of 23 doctors, midwifes, and nurses per 10,000 population.30 When contrasted with the regional average, the numbers are even more striking. Per 10,000 population, Haiti has less than 1 physician (regional, 20.8) and less than 1 nurse and midwife (regional, 45.8).25 There are no data for pediatric and obstetric physician specialists.

In our experience, physicians in Haiti are extremely capable and very interested in learning. However, their training has been very limited, with little outside influence. As we have learned from our onsite assessments, inadequate equipment and insufficient supplies of medication further compromise their practices. To produce the larger numbers of trained medical personnel needed to improve care, Haiti and partner organizations must undertake interventions to support high-quality medical, nursing, and allied health schools and resident programs, as a means to offset the brain drain and support national needs.

The problem of a shortage of trained medical personnel is exacerbated by the large exodus of professionals to Canada and to the US, a fact that has frustrated the health care leaders working in Haiti to improve conditions.6,31 Later in this article, we will address how this Haitian diaspora, estimated to be more than 1.5 million Haitians,32 can be a valuable part of the solution to fast-track improvements in this country’s health care.

Low Percentage of Skilled Attendants at Deliveries

Industrialized countries in the early 20th century halved the maternal mortality rate by providing professional midwifery care at childbirth.29 The importance of births attended by skilled health personnel is considered a key indicator for improvements in maternal health.33–35

As mentioned earlier, in Haiti in 2012, only 37% of deliveries had a skilled attendant present9; this remains basically unchanged in 2016. The average of other Caribbean countries was 94% in 2012.25 If the poorest 20% of pregnant Haitian mothers are considered, only 9.6% will have a skilled attendant at birth compared with 78% of the richest 20%.1 The low rate of attendant-assisted births in Haiti is even more striking when the 2008 to 2012 percentages of skilled attendant rates are subdivided into urban births (59.4%) and the extremely low percentage for rural births (24.6%).1 It is not difficult to understand why the neonatal and maternal death rates in Haiti are so high when one understands that 63% of countrywide deliveries and 75% of deliveries in rural settings were not attended by a provider skilled in obstetrics (physician, nurse, or nurse-midwife).12

Low Percentage of Prenatal and Postnatal Visits

Of pregnant women in Haiti, 40% do not have an antenatal care visit before their fourth month of pregnancy.25 Over all of Haiti in 2012, the percentage of mothers receiving antenatal care (at least 4 visits) was 67%. The regional average was 86% for postnatal care within 2 days of delivery.1 During the 41 days after giving birth, 61% of women did not have a postnatal checkup.12

High-Risk Deliveries in Nonqualified Health Facilities

Only 25% of women deliver in institutions, with 78.2% of women in the richest quintile delivering in health centers vs 5.9% of women in the poorest quintile.1 Most facilities are in urban areas, and even if mothers could make it to a facility, most facilities are generally not staffed or equipped adequately to provide the necessary obstetric care for complicated deliveries.6

STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS THE CRISIS

These statistics make it easy to understand why the CNM mortality rates are so much higher in Haiti than in other countries in the region. Although the situation is complex, it is clear that major changes are needed and must happen soon if the country is to successfully address this crisis and to improve the overall quality of medical care in the country. There are challenges to making these changes happen, yet studies suggest that with coordinated and collaborative efforts addressing each step of care, fewer children and mothers will die.36–38

To address the child and maternal health crisis, for the past 2 years Bethesda Referral & Teaching Hospital, Inc (BRTH), has been implementing 2 primary strategies: 1) construction of a 225-bed central referral and teaching hospital that will provide specialty care for communities throughout the country and 2) development of countrywide community care grids, a network of defined geographic populations, to facilitate the implementation of frontline interventions.

Central Referral Hospital

BRTH, a private, not-for-profit specialty teaching hospital, will be centrally located in the new Port Lafito in close proximity to the international airport and Port-au-Prince to facilitate transfers from across the country. Although there are capable hospitals in Haiti, most focus on primary and emergency care. To address the unacceptably high Haitian CNM mortality rates, BRTH will focus in the initial phase on maternal and child specialty health care, and subsequent phases will include medical and surgical subspecialties.

BRTH will provide access to care for high-risk infant and maternal patients throughout all of Haiti. It will support the implementation of evidence-based community interventions countrywide through innovative community care grids (described in the next section). Additionally, high-risk obstetric and pediatric patients will be triaged and transported from the community network to the hospital as necessary. An extensive communication network, transportation capabilities, and state-of-the-art telemedicine will facilitate the movement and care of patients.

The uniqueness of this model is that the BRTH staff will consist at any one time of more than 100 North American short-term health care volunteers providing one-on-one mentoring for physicians, midwives, and nurses from the Haitian medical community. This type of one-on-one teaching approach is not being used elsewhere in Haiti, to our knowledge.

To provide lodging for the visiting North American medical volunteers, the construction plans will include an adjoining guest hotel. As the need for visiting North American teachers diminishes over the years, the hotel will be converted to hospital beds, providing a cost-effective basis for future hospital expansion.

Improvement of the overall knowledge and procedural skills of the health care practitioners and enhancement of the specialty care referral infrastructure should improve health care in Haiti by any measurement.

The site for the hospital, Port Lafito, is a new, private economic zone covering more than 404 hectares (1000 acres) of oceanfront land developed 19.2 km (12 miles) north of Port-au-Prince.39 This project is a $145 million investment that includes a new port for container ships and a large industrial-free zone and business park, as well as 24-hour security; a residential area and country club will be included in later phases. The developers anticipate that the manufacturing zone will generate up to 20,000 new jobs by 2020. Clearly, this mixed-use development is one of the most exciting things to happen to Haiti in recent memory.40

This new project is owned and developed by the GB Group from Miami, one of the leading private industrial groups in the Caribbean.41 The chairman is Gilbert Bigio, a Haitian from one of the most respected families in Haiti. Mr Bigio, his family, and the GB Group understand the potential impact of BRTH and for that reason have generously donated 8.1 hectares of valuable property in the port area for construction of the hospital. BRTH and the GB Group are forming a strong partnership because both organizations have the same vision of expediting improvements in the quality of life for all Haitians.

Program Guiding Principles

The following principles will provide direction and ensure the successful implementation of the strategies:

Partnerships

A strong partnership with the Haitian community is essential. Since 2013, we have involved the Haitian medical, political, and social leadership in the development of this plan. The response from the Haitian leaders has been overwhelmingly positive. We believe that our partnership with them is essential because Haitians want to be, and should be, involved in resolving this crisis in their country. Also important are effective partnerships between BRTH and North American health care organizations, governmental agencies, and nonprofit organizations—a critical factor for success of the entire BRTH project that will be discussed later.

Inclusion

As are many other hospitals in Haiti, BRTH is a nonprofit Christian organization that highly values volunteers, employees, and patients of all faiths and ethnicities. It will take a large team of compassionate, talented medical volunteers to confront this crisis in Haiti, and so are all needed and all are welcome.Evidence-Based Holistic Care

Evidence-Based Holistic Care

The care processes and policies of BRTH will be in accordance with US standards and to the level required by accreditation agencies such as the Joint Commission International.42 We will strive to provide medical care whose basis is strong clinical evidence while considering the total need of patients including the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual.

Safety and Security

The hospital and guest hotel will be constructed in accordance with earthquake building codes and consider safety and security as prime design criteria. The GB Group has provided us with a tremendously secure site at Port Lafito, away from the population density of Port-au-Prince but centrally located. We plan to have intense security for entrance onto the hospital grounds as well as a high level of security throughout the hospital. We have port security outside and then security to enter the compound. Overall, we will provide employees and patients a secure environment and be able to offer volunteers a safe and meaningful experience.

Countrywide Interventions

These interventions will reflect the primary objective, which is to create partnerships to improve maternal and child health care in all of the departments of Haiti, regardless how distant from Port-au-Prince.

Financial Responsibility

Remuneration for hospital care will be based on a sliding-scale fee schedule, enabling care for referred patients to be provided without charge for those with no or limited income. However, we do not want to undermine the economics of local hospitals and practitioners. We will always support our hospital partners in Haiti by making certain that our financial approaches and general operations do not compromise their revenue or the revenue of individual practitioners in Haiti.

Adaptability

Because our model is unique, ambitious, and complex, the interventions we deploy must be regularly assessed and adjusted accordingly.

Fast-Tracking Improvements in Child, Neonatal, and Maternal Mortality

In this article, we have identified the major underlying factors for the high death rates of children and mothers in Haiti. The literature is clear; if mortality rates for neonates, children, and mothers in low- and middle-income countries are to decrease, it is essential that major improvements be achieved throughout the entire health system.32,35 Interventions must be implemented across the entire sector of care starting in the home, then in the community in each department, and finally extending to a functional referral facility. As stated by Bhutta et al29: “There is not a simple and straight forward intervention, which by itself will bring maternal mortality significantly down; and it is commonly agreed that the high maternal mortality can only be addressed if the health system is effective and strengthened.” We envision that BRTH, along with private- and public-sector partnerships in the community care grid network, will strengthen the health care infrastructure in Haiti by implementing interventions that will address the primary contributing factors identified in this article.

The following are the six major interventions that BRTH is implementing:

implement evidence-based interventions in the community

develop community care grids

increase the number and skills of health care professionals

provide affordable, high-quality health care

leverage communications and technology

transport patients to the hospital.

Implement Evidence-Based Interventions in the Community

Although the literature is not robust in identifying evidence-based interventions,35,36 there are sufficient data from several meta-analyses to understand the complexities of the problem, to identify proven interventions, and to propose strategies for low- and middle-income countries such as Haiti. We are implementing only evidence-based interventions that have been proved to be cost-effective, are culturally relevant, and can be deployed successfully. Frontline community interventions include preconception and prenatal maternal care, delivery care, and postpartum maternal, neonatal, and infant care.

The Sidebar: Evidence-Based Interventions lists evidence-based interventions based on several meta-analyses.35,43 The major improvements in child survival since 1990 are partly attributable to affordable, evidence-based interventions against the leading infectious diseases, use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets, rehydration treatment of diarrhea, nutritional supplements, and therapeutic food.44

Evidence-Based Interventions1.

| For all stages of care, there is “strong evidence” for the capacity to move patients emergently, urgently, and electively to the nearest equipped medical facility. ANTENATAL CARE PACKAGE Screenings:

Nutritional Supplementation

Immunizations

Case Management

|

CHILDBIRTH

Essential Obstetric Care

Case Management

|

POSTDELIVERY (MOTHER)

Case Management

|

POSTDELIVERY (NEWBORN)

Case Management

|

INFANTS AND CHILDREN YOUNGER THAN AGE FIVE YEARS

Nutritional Supplementation

Immunizations

Case Management

|

Essential interventions, commodities and guidelines for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health: a global review of the key interventions related to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health and the Aga Khan University; 2011 [cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/201112_essential_interventions/en/.

Water, sanitation and hygiene: UNCEF WASH strategies [Internet]. New York, NY: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF); Updated 2008 Mar 4 [cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: www.unicef.org/wash/index_43084.html.

Package of Interventions: Although the value of several interventions has been validated over time by several studies, it is important to emphasize that to lower mortality rates in children and mothers, implementation of multiple interventions together (a “package”) make much more of an impact than a single intervention.45 An example of a package of interventions is a World Bank study46 that presented multiple key countrywide factors necessary for reducing mortality rates:

increased availability of a skilled birth attendant

increased availability of health care facilities to provide skilled birthing care

appropriate service costs for the setting

strong policy guidance for delivery of care

a functional referral system, beginning with practitioners at the community level

accountability for practitioners’ performance.

Essential Obstetric Care: Essential (or emergency) obstetric care is another example of a package of interventions that, when implemented with prenatal interventions, has proved to be extremely effective in preventing mother and infant mortality and for that reason must be a component of any strategy to reduce CNM mortality.47 Campbell and Graham48 underscore the importance of this package: “Capacity to provide adequate and timely emergency obstetric care is, however, the minimum standard a health system is ethically obliged to provide to begin to address maternal mortality.” The six components of essential obstetric care37 are listed in the Sidebar: Evidence-Based Interventions (under Childbirth). Most of the capabilities on this list are not available at departmental health care facilities in rural Haiti, making it imperative that, when indicated, children and mothers can be transferred to a fully qualified central facility that can provide essential obstetric care.

Develop Community Care Grids

To assist departments throughout Haiti in implementing necessary interventions and to address the top 3 causative factors—accessibility barriers, the low percentage of skilled attendants, and the low percentage of prenatal visits—we have created a countrywide networking and community training approach that we call community care grids. Beginning with Haiti’s 10 departments, we have divided the country into geographic, population-based “grids.” Departments will be subdivided into additional grids as indicated by population densities or geographic impediments. We anticipate that around 20 grids will eventually be identified. These grids will enable us to collaborate at the local level to implement home-based and community-based interventions, to maximize the outreach strategies, and to facilitate timely referrals to BRTH.

Coordinators: To support this strategy, BRTH will hire, train, and oversee community care grid coordinators for each of the geographic grids. The coordinators’ responsibilities will be as follows:

To identify community leaders, including public health officials, church clergy, medical leaders (physicians, midwives, nurses), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and any government agencies active in the community within their assigned grids. All these individuals and organizations together will form the community care team

To define, in consultation with the local community care team, the geographic border of the grid as well as population estimates

To assess the CNM capabilities of the local health care system, including the capability of the local health facilities, the availability of medical personnel, and the level of financial barriers to service

To facilitate a collaborative process with the community care team to identify and to prioritize the best strategy for comprehensively deploying the frontline CNM package of interventions in their community

To assist the community care team members in identifying high-risk individuals (initially pregnant or new mothers and children) as well as to provide the health care professionals with details about how to refer patients to BRTH for specialty care

To coordinate the appropriate level of care for each patient by facilitating the referral of patients to BRTH or to other locations when the hospital is at capacity or when primary care and medical and surgical specialty services are not available in Phase 1 at BRTH.

We believe that this community grid strategy will provide the foundation for implementing the evidence-based interventions targeted to families, local communities, and departments throughout Haiti. We intend to build on the work already being done by the Minister of Health’s office, by several North American NGOs, and by Haitian medical personnel. To better understand how to best implement this approach, this year we have invested in the development of five pilot grid sites representing large and small communities as well as suburban Port-au-Prince and areas more remote from the city. In addition to defining the borders and population of each grid, these pilots have included CNM-related health surveys and screenings to support the interventions listed in the Sidebar: Evidence-Based Interventions. Such assessments have been done sporadically in Haiti in the past but not with the frequency and with the data elements that we will be compiling over the years in these five pilots. Additionally, we are creating a process with each pilot site’s community care team that would establish more accurate health care data, including such basic information as reliable birth and death documentation. We believe these baseline data will be indispensable in assessing the value of community interventions.

Funding: BRTH is committed to providing the income for the grid coordinators because they will be part of the hospital staff. Additionally, since it is important for the overall mission of the hospital, BRTH will provide the telemedicine capability for each department. All other funding will come from the public- and private-sector organizations and individuals making up each community care team. We believe that individuals and institutions will be more likely to contribute funds to an NGO or church when the organization is able to demonstrate a cohesive plan to implement proven communitywide interventions to save children and mothers. The challenge has not been the lack of funds; these interventions are not expensive when contrasted with the amount of money now being invested by North Americans throughout Haiti.

Collaboration: A critical success factor for this intervention will be the networking and collaboration of NGOs. In a report on low- and middle-income countries that successfully accelerated improvement in CNM care, Presern and associates38 noted that the one approach they all had in common was creating strong partnerships between governmental agencies and NGOs. The only way improvements in Haiti can be fast-tracked throughout the country will be through the networking and collaboration of large international organizations and foundations, as well as the smaller North American churches and other NGOs in the community in which they are working. Most of the North American NGOs work in outlying regions to provide valuable support to communities such as the building and equipping of clinics, schools, and orphanages, while also providing episodic medical and optical clinics. Although the exact number of NGOs and other humanitarian organizations working in Haiti is uncertain, the number ranges from several hundred to more than 1000.49 During the summer months, planes to and from Haiti carry 100s of short-term humanitarian workers from all over North America. In our experience, however, most of these North American churches and other NGOs work almost completely in isolation without coordinated strategies. Although their contributions fill major gaps in rural settings, there is almost no communication or large-scale networking efforts across these various entities, and collaboration and sharing of resources is extremely uncommon.28

Because not all NGOs have a good record of working together, an important question is why would they work together on community care grid teams. Many North Americans who have been involved in ministry in Haiti are probably aware of an infant or a mother who has died of a preventable illness, including birth complications, or children dying of infections. When NGOs realize how the proposed community grid strategies will save the lives of mothers and babies, including the lifesaving care available at BRTH, we believe that for the first time these North American churches and organizations will have a compelling reason to come together and collaborate.

Increase the Number and Skills of Health Care Professionals

The inadequate number and training of health care practitioners must be reversed to accomplish and sustain improvements in mortality rates. No other intervention will succeed until there are adequate numbers of high-quality, accessible Haitian-trained physicians, nurses, midwives, and other health care personnel.29 For this reason, BRTH will focus on training and employment to ensure the sustainability of quality and accessible medical care well into the future.

As a specialty teaching hospital, there will be extensive learning opportunities for Haitian health care personnel, including, but not limited to, physicians, midwives, nurses, nurse practitioners, residents, and students from all disciplines. Also included in training will be x-ray and laboratory technicians, hospital administrators, hospital food preparation, security, and maintenance personnel.

For this training to occur, there must be a strong partnership between BRTH and the Haitian medical community. We have involved leaders from hospitals, medical schools, and the Minister of Health’s office to understand their needs and plan together on how best to partner.

Training Approach: Our objective is to provide direct supervision and teaching of both cognitive and procedure skills for Haitian community physicians, midwives, medical students and residents, nurses, and other hospital personnel. Training at BRTH will be defined as one-on-one instruction and supervision, an approach not generally used in Haiti. The training will be based on established curriculum jointly developed by Haitian and North American educational leaders. Additionally, we intend to partner with present medical, nursing, and pharmacology schools in Haiti to provide educational opportunities.

Bethesda Recertification Program: To maximize educational efforts that will sustain health care improvement throughout Haiti, we plan for the primary teaching target group to be practicing community physicians, midwives, and specialty nurses. They will be invited to participate in BRTH’s medical education recertification program. It has been our experience that the Haitian medical community has always been receptive to outside high-quality teaching and that it values such educational certification opportunities.

Components of the recertification program include the following:

For most physicians, midwives, and nursing specialists the duration of involvement to receive the certification will be two years

There will be a minimum weekly four-hour commitment, for which time the practitioner will be paid

Recertification tests include written and practical examinations after the first year and a final examination after the completion of two years

Updates will be offered to those professionals completing recertification through special educational events offered in the future

The Haitian physicians and nursing specialists on BRTH’s staff will either be enrolled in the certification program or, at a later time, have completed it.

We believe that with intensive training, along with the availability of quality employment opportunities, the number of skilled health care professionals will increase to a level necessary to provide high-quality CNM coverage throughout the country. However, there must be good employment opportunities or these trained practitioners will consider leaving Haiti. It is our experience that Haitians do not want to leave, but with the lack of work they may believe they have no choice. In fact, we have learned from interviews during our needs assessment that many Haitian-American practitioners would like to return to Haiti if conditions improve. We will provide training and job opportunities at BRTH, and only then will the exodus from Haiti to the US and Canada stop being such a drain on the Haitian health care system.

A critical success factor for this intervention will be North American volunteers: This intervention is dependent on the participation of large numbers of North American short-term volunteer physicians, midwives, specialty nurses, and other health care personnel. We have made the assumption that most North American health care individuals would like to use their skills to provide service to those in need, whether in their community or around the world, especially if their skills can be applied with meaningful results. Although primary care physicians and nurses have opportunities through several volunteer organizations to serve overseas, this is not the case for specialists. There are very limited opportunities for physician specialists such as neonatologists, obstetricians, and surgeons to use their skills outside their practices. The same is true for midwives and specialty nurses, such as neonatal nurses and pediatric intensive care unit nurses. BRTH will provide just such a high-quality, safe, and meaningful teaching experience for North Americans to make a difference in Haiti. We believe that North American health care professionals from all disciplines and practices will want to be involved in such an endeavor that will be have a positive and major impact on the health condition of Haitians. Plus, the opportunity is so close to home.

Provide Affordable, High-Quality Health Care

As identified above, the underlying poverty in Haiti is a major barrier for mothers and children in accessing health care. As a short-term solution, the community care team will take steps to make certain that cost will not be a barrier to care and that services will be provided regardless of the ability to pay.

The long-term solution to removing the financial barrier is a robust economy with employment opportunities. Although the employment numbers at BRTH will be well below the large number at the Port Lafito industrial zone, we do anticipate hiring between 900 and 1400 local Haitians, to enhance the community economy while providing occupational training in hospital-related work skills.

As identified, another major causative factor to the CNM mortality rates is a very low percentage of deliveries occurring in qualified health facilities. To increase this percentage, in addition to the community care grid strategy, we will focus on two interventions: 1) leverage communications and technology and 2) transport patients to the hospital.

Leverage Communications and Technology

The Bethesda Communications Center at the hospital will be the central hub for the flow of information from the many community care grids throughout the country. A communication center will be staffed around the clock to receive phone calls for requests for care from community care team members. The staff will identify and triage specialty needs, and if appropriate, patients from these grids will be referred to BRTH for the appropriate care.

We will leverage state-of-the-art telemedicine capabilities from any location in the country to provide an “e-consult” with colleagues at BRTH or with experts across North America. Real-time telemedicine assessments, such as ultrasonography and cardiac assessments, will help determine the most appropriate interventions for mothers and infants.

Transport Patients to the Hospital

As outlined in the Sidebar: Haiti Demographics, the mountainous terrain, poor highway infrastructure, and lack of affordable transportation provide obstacles to children and mothers reaching the best facility for care. Even if there were well-equipped and well-staffed neonatal intensive care units located centrally in the Port-au-Prince area, most neonates born in the rural areas would still not be able to access this care because of transportation challenges.

For this reason, we will have vehicles and contracted air transportation available to transport children, newborns, and pregnant and postpartum mothers to the hospital for lifesaving care. On the basis of information received by the Bethesda Communications Center, supplemented as necessary by telemedicine-generated clinical data, it will be determined whether the patient needs to be transported to the BRTH or to another appropriate hospital. Depending on the urgency of the situation, transportation will be deployed to bring patients to the hospital. We believe that with planning, coordination, and experience, we can achieve a door-to-door time that will meet most of the patients’ needs.

Perceptions of Corruption and the Impact on the Hospital

When we tell our Bethesda story, it does not take long before we are asked about how we deal with corruption in Haiti, a question that is usually followed by comments related to misuse of earthquake relief funds. We must address this question because individuals and organizations considering donating their time and money will want to know how BRTH plans to move forward in a country with these concerns.

Transparency International is a nonpartisan, independent group that each year publishes a “corruption perceptions index” for 175 countries, ranking each on the basis of public perceptions of corruption obtained from survey data and interviews.50 The higher the score, the greater the public perception of corruption. The 2014 index ranking for Haiti was 161 of 175, ranking it among the most corrupted countries in the world.51 In contrast, the Dominican Republic’s corruption perceptions index was 115 and Puerto Rico’s was 31.

So how does BRTH, as a large nonprofit organization dependent on philanthropic donors, thrive in such an environment? First, BRHT’s stateside corporation holds all assets, ensuring that funds go directly to the hospital operations. As part of the organizational structure, there is a Haitian NGO created to provide administrative management of the hospital, but complete governance and control of finances resides in the US. Second, there is a major layer of protection from the influences of corruption by having BRTH located in the privately owned Port Lafito. The importance of our partnership with the GB Group cannot be underestimated when it comes to being sheltered from unnecessary public-sector interference.

Finally, we will always promote and operate with values that are incompatible with corruption. When it comes to our relations with community hospitals, and as we partner with the public sector in the grids, our intolerance for bribery, nepotism, and other forms of corruption will be obvious to all. This was true three years ago when we wrote the first prospectus on BRTH in which we emphasized one of our major values: “we will be ethical and honest in all of our transactions.” We will be clear; we intend to confront corruption at every opportunity.

Status of Plans

After years of planning, and now having several major partners joining this venture, we anticipate that funding will be in place within a year to support construction on the hospital and guest hotel. To make this happen, it will take the philanthropic efforts of individuals, corporations, and organizations who share our vision for saving mothers and children in Haiti—beginning as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, we are moving ahead on several fronts. We are meeting regularly with our architect and interviewing contractors, and we have started the implementation of the community care grids by working in five grid pilots. Additionally, we are participating in conferences and meetings to mobilize North Americans, including physicians, midwives, and nurse specialists, and we are taking steps to involve Haitians in the North American Haiti diaspora.

CONCLUSION

The situation in Haiti is grim. The death rates for newborns, mothers, and children are at crisis proportions with no objective evidence that the mortality rate is improving or any reason to believe that it will.

On the basis of the data presented in this article, we can anticipate that the planned new hospital, along with the many partnerships developed through the countrywide community care grid network, will be a major impetus for fast-tracking the needed improvements in Haiti’s health care system.

As a demonstration project, BRTH will provide valuable information for international organizations such as the WHO, UNICEF, US Agency for International Development, the World Bank, and other organizations as they consider the most cost-effective, countrywide approaches for improving the health care infrastructures of low- and middle-income countries.

The strength of this approach is that it leverages several important realities:

the excitement and support for this project from the Haitian medical and political communities

the opportunity for North American specialty physicians, midwives, and nurses to use their skills in a meaningful way

the proximity of Haiti to the US—for many, just a brief plane flight away

the meaningful and sustainable opportunity to improve the skills of the Haitian workforce.

Most importantly, the lives of babies, children, and mothers will be saved.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Marat Turgunbaev, MD, MPH, MBA, for his research assistance.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to report.

The Children’s Bill of Rights

The proper shelter, nutrition, clothes, education, and health measures be provided each child to assure that each, with maturity, can assume the full responsibilities of adulthood and citizenship.

— The Children’s Bill of Rights; Billy F Andrews, MD

References

- 1.At a glance: Haiti [Internet] New York, NY: UNICEF; updated 2010 Jan 23[cited 2013 Dec 12]. Available from: www.unicef.org/infobycountry/haiti_2014.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fulfilling the health agenda for women and children: the 2014 report [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: Countdown to 2015: Maternal, Newborn & Child Survival, World Health Organization; 2014 Jun 30[cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.countdown2015mnch.org/reports-and-articles/2014-report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haiti: neonatal and child health profile [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization: Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health; 2012 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/profiles/neonatal_child/hti.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1,000 live births) [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.NMRT. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Countries [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.worldbank.org/en/country. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prins A, Kone A, Nolan N, Thatte N. USAID/HAITI maternal and child health and family planning portfolio review and assessment [Internet] Cambridge, MA: Management Sciences for Health; 2008. Aug, [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/citations/3476. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO/UNICEF joint statement Home visits for the newborn child: A strategy to improve survival [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [cited 2015 Dec 10]. Available from: www.unicef.org/health/files/WHO_FCH_CAH_09.02_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Causes of child mortality, 2000–2012[Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/mortality_causes_region_text/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estimated national rates of preterm births in 2010 [Internet] White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 2010 [cited 2015 Dec 10]. Available from: www.marchofdimes.org/mission/global-preterm.aspx#tabs-2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wardlaw T, Blanc A, Zupan J, Åhman E. Low birthweight: country, regional and global estimates [Internet] New York, NY: UNICEF; 2004. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.unicef.org/publications/files/low_birthweight_from_EY.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouillette RT, Andrews K, Brouillette DB. In: Mortality, infant. Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development. Haith MM, Benson JB, editors. Waltham, MA: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 343–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.2012 Haiti mortality, morbidity, and service utilization survey: key findings [Internet] Calverton, MD: Ministry of Public Health and Population, Haitian Childhood Institute, ICF International; 2013. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR199/SR199.eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global Health Observatory data repository: Haiti statistics summary (2002-present) [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-HTI. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibley LM, Sipe TA. Transition to skilled birth attendance: is there a future role for trained traditional birth attendants? J Health Popul Nutr. 2006 Dec;24(4):472–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langlois EV, Miszkurka M, Ziegler D, Karp I, Zunzunegui MV. Protocol for a systematic review on inequalities in postnatal care services utilization in lowand middle-income countries. Syst Rev. 2013 Jul 6;2:55. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-55. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-2-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Approach paper: systematic review of impact evaluations in maternal and child health [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2013. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/Data/reports/mch_approach_paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilano VL, Ota E, Ganchimeg T, Mori R, Souza JP. Risk factors of preeclampsia/eclampsia and its adverse outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a WHO secondary analysis. PloS One. 2014 Mar 21;9(3):e91198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091198. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/0.1371/journal.pone.0091198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC in Haiti: factsheet [Internet] Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Nov, [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/haiti/pdf/haiti.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schantz-Dunn J, Nour NM. Malaria and pregnancy: a global health perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Summer;2(3):186–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Malaria acquired in Haiti— 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Mar 5;59(8):217–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World malaria report 2014: Haiti [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.who.int/malaria/publications/country-profiles/profile_hti_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Insecticide treated net (ITN) use by pregnant women [Internet] New York, NY: UNICEF; updated 2015 Apr[cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://data.unicef.org/ITN_use_pregn_April_2015_update_UNICEF_9590c8.xlsx?file=ITN_use_pregn_April_2015_update_UNICEF_95.xlsx&type=topics. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Incidence of tuberculosis (per 100,000 people) [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD/countries. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haiti: WHO Statistical profile [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.who.int/gho/countries/hti.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobacco control report for the region of the Americas [Internet] Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2011 [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=16836&Itemid= [Google Scholar]

- 26.Living conditions in Haiti’s capital improve, but rural communities remain very poor [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2014. Jul 11, [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/07/11/while-living-conditions-in-port-au-prince-are-improving-haiti-countryside-remains-very-poor. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haiti: PAHO/WHO technical cooperation 2010–2011. Free obstetric care project/free child care project [Internet] Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2011. [cited 2015 Oct 12]. Available from: www.paho.org/hai/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=939&Itemid= [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haiti: PAHO/WHO technical cooperation 2010–2011. Strengthening health systems and services [Internet] Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2011. Available from: www.paho.org/hai/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=940&Itemid=7004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Mansoor N. Systemic review on human resources for health interventions to improve maternal health outcomes: evidence from developing countries [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: HRH for Maternal Health, World Health Organization; 2010. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.who.int/pmnch/activities/human_resources/hrh_maternal_health_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achieving the health-related MDGs It takes a workforce! [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.who.int/hrh/workforce_mdgs/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arthur C. Haiti: a guide to the people, politics and culture. Brooklyn, NY: Interlink Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haiti. Health in the Americas, 2012 edition: country volume [Internet] Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.paho.org/saludenlasamericas/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=134&Itemid= [Google Scholar]

- 33.Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: skilled attendants at birth [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.who.int/gho/maternal_health/skilled_care/skilled_birth_attendance_text/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tita AT, Stringer JS, Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Two decades of the safe motherhood initiative: time for another wooden spoon award? Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Nov;110(5):972–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000281668.71111.ea. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000281668.71111.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005 Feb;115(2 Suppl):519–617. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1441. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reducing maternal mortality in developing countries [Internet] San Francisco, CA: GiveWell; 2009. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.givewell.org/international/technical/programs/maternal-mortality. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodburn E, Campbell O. Reducing maternal mortality in the developing world: sector-wide approaches may be the key. BMJ. 2001 Apr 14;322(7291):917–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7291.917. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7291.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Presern C, Bustreo F, Evans T, Ghaffar A. Accelerating progress on women’s and children’s health. Bull World Health Organ. 2014 Jul 1;92(7):467–467A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.142398. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.142398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafito global [Internet] Port-au-Prince, Haiti: GB Group; 2015. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: http://gbgroup.com/our-businesses/infrastructure/lafito-global/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haiti—economy: Port Lafito, a historic first [Internet] HaitiLibre; 2015 Feb 23 [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.haitilibre.com/en/news-13242-haiti-economy-port-lafito-a-historic-first.html.

- 41.GB Group [Internet] Port-au-Prince, Haiti: GB Group; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: http://gbgroup.com. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joint Commission International [Internet] Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission International; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.jointcommissioninternational.org. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L, Lancet Neonatal Steering Team Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005 Mar 12–18;365(9463):977–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2014 [Internet]. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.unicef.org/media/files/Levels_and_Trends_in_Child_Mortality_2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reducing maternal, newborn and child deaths in the Asia Pacific: strategies that work [Internet] Melbourne, Australia: World Vision, The Nossal Institute for Global Health at The University of Melbourne; World Vision Australia; 2008. Available from: http://my.worldvision.com.au/Libraries/3_3_1_Aid_Trade_and_MDGs_PDF_reports/Reducing_maternal_newborn_and_child_deaths_in_the_Asia_Pacific_Strategies_that_work.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koblinsky MA, editor. Reducing maternal mortality—learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Zimbabwe [Internet] Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2003. Apr 30, [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2003/04/2360798/reducing-maternal-mortality-learning-bolivia-china-egypt-honduras-indonesia-jamaica-zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paxton A, Maine D, Freedman L, Fry D, Lobis S. The evidence for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Feb;88(2):181–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.026. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell OM, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006 Oct 7;368(9543):1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramachandran V. Is Haiti doomed to be the Republic of NGOs? [Internet] Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2012. Jan 9, [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.cgdev.org/blog/haiti-doomed-be-republic-ngos. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Transparency International: the global coalition against corruption [Internet] Berlin, Germany: Transparency International; c2015 [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.transparency.org. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corruption scores by country [Internet] Berlin, Germany: Transparency International; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: www.transparency.org/country. [Google Scholar]