Introduction

Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL), also known as Haberland syndrome, is a rare neurocutaneous condition first described by Haberland and Perou in 1970.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Most ECCL patients present with characteristic lipomatous hamartomas with overlying alopecia in a unilateral distribution on the scalp and ipsilateral scleral lipoepidermoid cysts, excrescences of the eyelid, and notching of the eyelid.1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 The subcutaneous fatty mass with nonscarring alopecia seen in patients with ECCL is better known as a nevus psiloliparus and is the dermatologic hallmark of the condition.1, 4, 5, 6 Because of the nonprogressing nature of the lesions involved, most patients with ECCL live nearly normal lives with the exception of an increased chance of epileptic seizures, mild-to-moderate mental retardation, and motor impairment that all correlate with the presence of cerebral malformations or growths, such as intracranial lipomas, spinal lipomas, arachnoid cysts, atrophy of a hemisphere, porencephalic cysts, dilated ventricles, hydrocephalus, and calcifications.1, 2, 6, 7, 8

We report the case of a 13-month-old white boy that presented to our clinic with a 4- × 6-cm nevus psiloliparus extending bilaterally on his vertex scalp, bilateral dermoid tumors in his eyes, macrocephaly, and a possible arachnoid cyst. This case is unusual in the bilateral distribution of the nevus psiloliparus and the overall lack of corresponding anomalies that are commonly seen in ECCL.

Case report

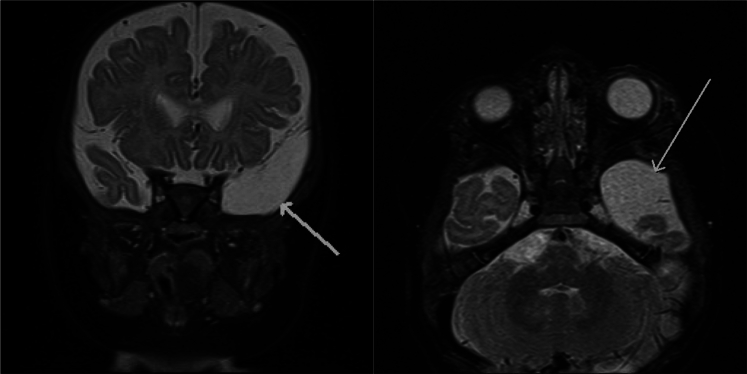

A 13-month-old white boy was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a patch of alopecia on his vertex scalp that had been present since birth. Before presenting to our clinic, an evaluation by the ophthalmology department found that the patient also had a lipodermoid of the left eye and limbal dermoid of the right eye. A biopsy of the left eye lesion confirmed the diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cranium and spine found a prominence of the extra-axial space anterior to the left temporal lobe consistent with possible arachnoid cyst formation (Fig 1). At the time of this writing, the patient is 25 months old, has never experienced any seizures, and is meeting all developmental milestones for his age.

Fig 1.

MRI with arrows pointing to arachnoid cyst.

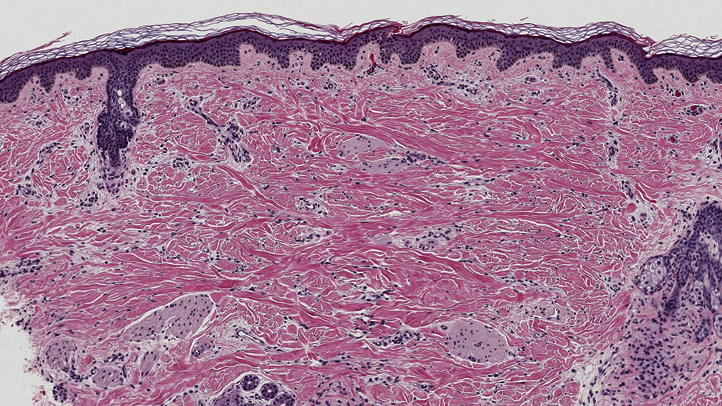

Physical examination found a 4- × 6-cm alopecic patch with fine vellus hairs on the vertex of the scalp that was associated with slight elevation and induration by palpation (Fig 2). This lesion was present since birth and was initially thought to be the result of vacuum extraction during vaginal delivery. A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen showed a paucity of hair follicles, isolated arrector pili muscles predominantly arranged in a parallel pattern to the skin surface, and increased lipomatous or fibrolipomatous tissue that extended into the reticular dermis (Fig 3). These findings were consistent with nevus psiloliparus. Combined with the patient's bilateral ocular dermoid tumors and macrocephaly, the diagnosis of ECCL was made. Electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and renal ultrasound scan were obtained and showed no abnormalities common to the condition, such as aortic coarctation and pelvic kidney. Given the potential for segmental aneuploidy, karyotype and single nucleotide polymorphism DNA microarray were tested and were normal.

Fig 2.

Nevus psiloliparus.

Fig 3.

Histopathologic picture shows an increase in lipomatous or fibrolipomatous tissue extending into the reticular dermis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×4.)

Discussion

ECCL or Haberland syndrome was first described as an example of ectomesodermal dysgenesis.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 The condition does not have a gender, race, or geographic predisposition and is usually diagnosed at birth with nonprogressive cutaneous abnormalities of the face and scalp, along with benign ocular tumors.2, 3

Clinically, the hallmark cutaneous finding in a patient with ECCL is a fatty tissue nevus called a nevus psiloliparus that presents in a unilateral, or more rarely bilateral, distribution on the scalp.1, 4, 5, 6 Nevus psiloliparus can present in various sizes with overlying patches of alopecia, in association with aplasia cutis congenita (didymosis aplasticopsilolipara), or in patchy or linear patterns that follow the lines of Blaschko.1 Histopathologically, nevus psiloliparus shows absence of mature hair follicles, arrested development of pilosebaceous units, focal areas of dermal fibrosis, increased subcutaneous fat extending into the upper reticular dermis, and orphaned arrector pili muscles within the dermis.1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10

The most common ophthalmologic manifestations of ECCL are benign ocular tumors called choristomas. These ocular growths include epibulbar or limbal dermoids and lipodermoids. Other less common ocular findings of ECCL include iris dysplasia, coloboma, optic nerve pallor, myopia, and microphthalmia.1, 5, 6, 9

Neurologic symptoms of ECCL are varied and do not automatically correlate with the extent of anatomic involvement. Mental retardation, seizures, and motor impairment may develop over several years with variations in the severity of symptoms.1, 3, 5, 6, 8

Central nervous system manifestations of ECCL include intracranial lipomas commonly found in the cerebellopontine angle, spinal lipomas, arachnoid cysts, asymmetric changes in the cerebrum to include complete or partial atrophy of a hemisphere, porencephalic cysts, calcifications, dilated ventricles, and hydrocephalus.1 These malformations are commonly diagnosed through MRI and can present clinically as macrocephaly in cases involving hydrocephalus.

In a review of 54 cases, Moog1 found that eye anomalies (primarily choristomas) and skin lesions (nevus psiloliparus, nonscarring alopecia, subcutaneous fatty masses, nodular skin tags, and aplastic scalp defects) could present in either a bilateral or unilateral distribution and occur in a consistent pattern among patients. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of ECCL patients have normal development or mild retardation only, and up to one-half experience seizures. However, the extent of central nervous system anomalies seen with neuroimaging cannot serve as an accurate predictor of future neurologic manifestations. Aortic coarctation, progressive bone cysts, jaw tumors, and pelvic kidney formation may also be associated, thus, requiring further testing and imaging for accurate diagnosis.1

A small number of other neurocutaneous conditions should be considered when evaluating a patient with possible ECCL. Proteus syndrome (mosaic AKT1-activating mutation) can present similarly to ECCL but has a progressive course with asymmetric overgrowth of bones, soft tissue, adipose tissue, connective tissue nevi, epidermal nevi, and vascular malformations. Congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi, and spinal/skeletal anomalies (CLOVES syndrome) is a similar condition caused by a mosaic PIK3CA-activating gene defect. Although lipomatous overgrowth can be seen in both syndromes, the other hallmark signs of CLOVES are not present in ECCL. Another entity in the differential diagnosis is oculoectodermal syndrome, which has overlapping ocular and skin features with ECCL, including epibulbar dermoids and aplasia cutis congenita, and may represent a different variant in the spectrum of a single syndrome with ECCL.11 Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome is also comparable to ECCL clinically. However, unlike ECCL, in which a nevus psiloliparus is the most common cutaneous finding, oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome has postauricular almond-shaped hypoplastic skin defects as the major cutaneous hallmark.1 Finally, epidermal nevus syndrome (NRAS, HRAS, KRAS activating mutations) shares many of the same eye abnormalities of ECCL but differs in that the cutaneous findings are more complex and include evolving epidermal nevi that commonly follow the lines of Blaschko.1

ECCL (Haberland syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous condition that commonly presents with unilateral or bilateral skin and eye anomalies soon after birth in addition to various central nervous system abnormalities.1 Although the genetic mutation for ECCL is still undetermined, it is most likely the result of mosaicism for a mutated autosomal gene with or without a second hit event.1, 5, 6

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

The opinions offered are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the US Army, US Air Force, or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Moog U. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. J Med Genet. 2009;46(11):721–729. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahariev Z.I., Peycheva M.V., Dobrev H.P. A case of encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis syndrome with epilepsy (Haberland syndrome) Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2009;51(4):46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubegni P., Risulo M., Sbano P., Buonocore G., Perrone S., Fimiani M. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (Haberland syndrome) with bilateral cutaneous and visceral involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(4):387–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stieler K.M., Astner S., Bohner G. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis with didymosis aplasticopsilolipara. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(2):266–268. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardo I.A., Nicolas M.E. A Filipino male with encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (Haberland's syndrome) J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7(2):46–48. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2013.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romiti R., Rengifo J.A., Arnone M., Sotto M.N., Valente N.Y., Jansen T. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis: a new case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 1999;26(12):808–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowaczyk M.J., Mernagh J.R., Bourgeois J.M., Thompson P.J., Jurriaans E. Antenatal and postnatal findings in encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91(4):261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torrelo A., Boente Mdel C., Nieto O. Nevus psiloliparus and aplasia cutis: a further possible example of didymosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(3):206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekin B., Yücelten A.D., Akpınar I.N., Ekinci G. Coexistence of aplasia cutis and nevus psiloliparus–report of a novel case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(6):746–748. doi: 10.1111/pde.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Happle R., Horster S. Nevus psiloliparus: report of two nonsyndromic cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14(5):314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habib F., Elsaid M.F., Salem K.Y., Ibrahim K.O., Mohamen K. “Oculo-ectodermal syndrome: A case report and further delineation of the syndrome”. Qatar Med J. 2014;2014(2):114–122. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]