Abstract

How contraceptives affect women’s sexual well-being is critically understudied. Fortunately, a growing literature focuses on sexual aspects of contraception, especially hormonal contraception’s associations with libido. However, a more holistic approach to contraceptive sexual acceptability is needed to capture the full range of women’s sexual experiences. We conducted a narrative literature review of this topic, working with an original sample of 3,001 citations published from 2005 to 2015. In Part 1, we draw from a subset of this literature (264 citations) to build a new conceptual model of sexual acceptability. Aspects include macro factors (gender, social inequality, culture, and structure), relationship factors (dyadic influences and partner preferences), and individual factors (sexual functioning, sexual preferences, such as dis/inhibition, spontaneity, pleasure, the sexual aspects of side effects, such as bleeding, mood changes, sexual identity and sexual minority status, and pregnancy intentions). In Part 2, we review the empirical literature on the sexual acceptability of individual methods (103 citations), applying the model as much as possible. Results suggest contraceptives can affect women’s sexuality in a wide variety of positive and negative ways that extend beyond sexual functioning alone. More attention to sexual acceptability could promote both women’s sexual well-being and more widespread, user-friendly contraceptive practices.

Access to safe, effective contraception is both a public health and feminist imperative. Family planning products and services are associated with a range of health benefits, including reduced unintended pregnancies, improved infant health, and lowered pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality (Kavanaugh & Anderson, 2013). Successful fertility control also leads to many social and economic benefits for women, from educational attainment and personal autonomy to relationship stability and satisfaction (Sonfield, Hasstedt, Kavanaugh, & Anderson, 2013). Thus, contraceptive access and acceptability are critical to both sexual and social health.

A severely understudied aspect of contraceptives is their sexual acceptability, or how methods influence the user’s sexual experiences, which can in turn influence family planning preferences and practices. Though contraception is expressly designed for sexual activity, we know little about how contraceptives affect women’s sexual functioning and well-being. This “pleasure deficit” (Higgins & Hirsch, 2007) is even more striking when compared to research on male-based methods (Oudshoorn, 2003) or even newer multiprevention technologies for women, such as microbicides (Jones et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2010; Mathenjwa & Maharaj, 2012; Sobze Sanou et al., 2013; Tanner et al., 2009; Woodsong & Alleman, 2008; Zubowicz et al., 2006). Researchers and policymakers have recognized that limited uptake of these latter methods will result unless they are sexually acceptable (i.e., do not hinder or interfere with sexual pleasure) for both partners. In comparison, portrayals of female-based contraceptives in the scientific, media, and public policy spheres are almost entirely de-eroticized.

Researchers have documented a number of reasons why we consider contraceptives more a medical than a sexual good (Granzow, 2007; Hensel, Newcamp, Miles, & Fortenberry, 2011). For example, advocates from the late 19th through the end of the 20th century sought medical and legal respectability for birth control, thus downplaying its potentially sexually revolutionary aspects—especially for women (Tone, 2006). Even today, while advertisements for male condoms and erectile dysfunction medications highlight sexual pleasure and enjoyment as the products’ main selling points, few erotic scripts of contraceptives used by women exist in mainstream culture, illustrated in both contraceptive advertisements (Medley-Rath & Simonds, 2010) and pornographic films (Shachner, 2014). The state can also devalue women’s sexuality in place of narratives around motherhood—as evidenced, for example, in laws surrounding health care reform and over-the-counter access to emergency contraception (Burkstrand-Reid, 2013). 1 School-based sexuality education similarly focuses on the harms versus the pleasures of sex (Connell, 2009; Goldman, 2008), especially for girls and young women (Fine, 1988). Clinically, care providers may lack both tools and time to discuss sexual issues with patients (Akers, Gold, Borrero, Santucci, & Schwarz, 2010; Bombas et al., 2012), and providers may be especially unlikely to inquire about sexuality in relationship to new contraceptive methods (versus, say, menopause) (Kottmel, Ruether‐Wolf, & Bitzer, 2014). Public health programs and policies can also both reflect and perpetuate dominant gendered assumptions about women’s sexuality—for example, with female condom programs focusing on reproductive health outcomes versus sexual rights (Peters, van Driel, & Jansen, 2013), or with adolescent pregnancy prevention policies that emphasize “sex is not for fun” and that young women should be sexually uninterested (Goicolea, Wulff, Sebastian, & Öhman, 2010). All these phenomena underscore the notion that contraception is a medical versus a sexual good; they also contribute to mixed messages about whether contraceptives should be sexually acceptable at all for women.

Despite these reasons, while contraception certainly helps people maximize their health, women do not have sex in order to use contraception. Rather, women engage in sexual activity for a range of recreational, relational, and personal reasons. Overlooking these reasons will not only fail to recognize women as full sexual agents but also limit people’s willingness to use contraception (Gomez & Clark, 2014; Lessard et al., 2012).

After all, though contraceptives need to be effective to prevent pregnancy, they also need to be acceptable so women will use them. However, despite decades of research, we still face questions about how to make these products as acceptable and appealing as possible, and many women are unsatisfied with their method and/or are using their method inconsistently. For example, in a study of 1,840 new contraceptive users in the United States, after 12 months of use only 41% of pill users were “very satisfied” with their method, and 45% of women using oral contraceptives at baseline discontinued using this method at some point during the year (Peipert et al., 2011). The limited success of contraception is also affected by personal use practices that contribute to a large gap between perfect-use and typical-use failure rates for many methods. 2 For example, the typical-use failure rate of combined oral contraceptives (9%), the most popular method of contraception in the United States (Daniels, Daugherty, & Jones, 2014), is 30 times worse than its perfect-use failure rate of 0.3% (Trussell, 2011). The overwhelming majority of “contraceptive failures” attributed to methods such as oral contraceptive pills (Jones, Darroch, & Henshaw, 2002) and male condoms (Sanders et al., 2012) are due to behavior on the part of the users, not malfunctions of the products themselves (Sanders et al., 2012). Better documenting sexual acceptability could potentially help explain why women dislike, discontinue, and/or use certain methods inconsistently. Ultimately, attending to sexual acceptability could also improve contraceptive practices—and women’s lives—by matching women with contraceptive methods that they will like and use over time.

Encouragingly, in recent years, reproductive health researchers have shown progressive interest in how contraception affects women’s sexual functioning and how sexuality may influence people’s contraceptive choices and practices. Scholars have published several reviews on this topic, particularly in terms of hormonal contraception and sexual functioning (Burrows, Basha, & Goldstein, 2012; Schaffir, 2006; Stuckey, 2008; Welling, 2013). This growing body of research suggests significant associations between contraceptives’ sexual acceptability—particularly with regards to the domain of sexual function—and how consistently and continuously women use these methods. However, given the relatively nascent state of this research, significant knowledge gaps remain.

First, this literature could benefit from a review of the larger method mix. Though there are scant reviews of hormonal contraception (Burrows et al., 2012), intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants (Sanders, Smith, & Higgins, 2014), and oral contraceptives (Davis & Castano, 2004), comparatively few reviews examine a wider range of methods—including male condoms and their influences on women’s sexual experiences (and not men’s alone). Condoms are one of the most commonly used contraceptive methods in the world and are the only currently available method that protects against both pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Although a systematic review of all studies on all methods of contraception is beyond the scope of any one article, we endeavor to capture at least a wider swath of the method mix. Doing so will enable us to compare and contrast the range of methods available to individuals or couples seeking contraception.

A second critical gap is existing studies’ relatively narrow approach to sexual acceptability—sometimes with only a single question (Graesslin et al., 2009; Wiebe, 2010). When researchers have measured contraceptives’ sexual aspects, they most frequently use measures of classic sexual functioning such as arousal, desire (libido), lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. The most common assessment tool is the Female Sexual Functioning Index (FSFI) (Rosen et al., 2000), which is used both in the United States and in studies all over the world. However, researchers use a large variety of scales and measures, many of which appear in Appendix A (online). (Please refer to Appendix A for detailed outlines of studies, methodologies, and measures used in contemporary contraceptive research). Most of these sexuality measures were originally developed to help identify sexual dysfunction, usually in midlife women experiencing sexual or other health problems, and may not serve particularly useful in identifying contraceptive-related sexual outcomes in younger, healthy women. Most scales also fail to measure partner- or relationship-specific aspects of sexuality (Manuel, 2013; Puts & Pope, 2013). For example, though contraceptive acceptability studies tend to document how methods affect bleeding, cramping, mood, or breast tenderness, rarely are such effects considered for their specifically sexual repercussions. Nor do studies tend to assess how individual sexual preferences for dis/inhibition or spontaneity may contribute to contraceptive acceptability. After all, sexuality encompasses myriad factors, from physiological function and sensation to broader psychological well-being (Cobey & Buunk, 2012), and contraception could affect all these experiences. Moreover, the broader sociocultural context conditions virtually all the potential pathways through which contraception can influence women’s sexuality. Needed is a model of contraceptive sexual acceptability that incorporates a wider range of sexual aspects, experiences, and influences.

This narrative review addresses both these gaps. In Part 1, we draw on the literature to define and operationalize a socioecological model for the sexual acceptability of contraception. In Part 2, we apply this model as we review the past 10 years of literature on the sexual acceptability of specific methods.

METHODOLOGY

We employed a narrative review approach, which provides a broad overview of the topic area (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010a, 2010b). This approach is apt for our goal of defining and then applying a novel concept versus methodically investigating a narrow, clearly defined question (per systematic reviews). The narrative approach is particularly well suited for topics in which vast evidence is lacking, as investigators can make recommendations or conjectures based on their work with the broader literature.

Though explicit search protocols are more common in traditional systematic reviews than narrative reviews, we nonetheless used specific search criteria and terms to create boundaries for our endeavor. Our search terms in PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were as follows: (contraception OR contraceptive OR contraceptive device OR contraceptive devices) AND (pleasure OR libido OR “sexual function” OR “sexual functioning” OR sexuality NOT [“sexual behavior” OR “sexual health”]). Since we wanted to conduct a review of all contraceptive methods that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), not merely one type of method (as is more common), we elected to limit our search to a particular time frame. We focused on the past decade (2005–2015) given both the relatively rapid pace at which contraceptive technology evolves and the fact that second-generation IUDs and implants have only made a resurgence in the last five to 10 years. We thus limited the search to English language articles published in the past 10 years (2005–2015). We identified several other sources from earlier years given their particular relevance to the topic. After removal of duplications, the original search located 3,001 references (1,819 in PubMed, 438 in Web of Science, 661 in CINAHL, and 418 in PsycINFO).

We enlisted a third, doctoral-level colleague with expertise in this area to help with the first review of these 3,001 references. Two people initially reviewed each title and abstract (sometimes the entire piece as well) to identify articles, chapters, commentaries, and other works that spoke to or informed some knowledge of the relationship between sexual experience and contraception use. Based on these assessments, each piece was placed into a yes, maybe, or no file. The first author then reviewed all those labeled as maybe; she placed nine of these additional references in the yes category, for a total of N = 485 citations identified for review in the next stage. The second author then categorized each citation based on the contraceptive method(s) covered and/or the section(s) of the review for which it was relevant. During the final review stage, we read each article to identify which best informed our understanding and conceptualization of sexual acceptability. For Part 1, we worked more closely with a subset of 264 citations, including articles, commentaries, book chapters, and dissertations; for Part 2, we identified 226 sources that referenced sexuality in relation to contraception use. Of those, 103 peer-reviewed articles explicitly measured sexual outcomes. We summarize these 103 studies in Table 1. (For a more detailed outline of each of these 103 articles, please see our Supplemental Table online.)

TABLE 1.

SUMMARY OF STUDIES REVIEWED IN PART 2: Positive and negative sexual aspects of contraception documented by peer-reviewed research, 2005-2015

| Methods | Citations | Select Positive Sexual Impacts | Select Negative Sexual Impacts | Comments and Commonalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Male Condom1 (n=54 identified in the review) Reviewed here: Male condom research that addresses women’s experiences (n=21) |

(Bolton et al., 2010) (Braun, 2013) (Crosby et al., 2008) (Crosby et al., 2013) (Crosby et al., 2010) (Deardorff, Tschann, et al., 2013) (Fennell, 2014) (Free et al., 2007) (Garcia et al., 2006) (Gebhardt et al., 2006) (Higgins et al., 2009) (Higgins & Wang, 2015a) (Kaneko, 2007) (Randolph et al., 2007) (Sanders et al., 2010) (Sunmola, 2005) (Træen & Gravningen, 2011) (Tung et al., 2012) (Versteeg & Murray, 2008) (Wang, 2013) (Widdice et al., 2006) |

Among women, condom use was positively associated with feeling comfortable communicating about sex and about sex in general. Young women expressing higher levels of sexual self-acceptance were less likely to report a dislike of condoms as a strategy to avoid using them (Deardorff, Tschann, et al., 2013). Female sex workers described skills in applying condoms in sexually arousing ways in order to increase client acceptance of condom use (Free et al., 2007). Men and women perceived condoms as hygienic and as providing sense of security and protection (Garcia et al., 2006). Among women who always used condoms, 28% agreed that condoms reduce sexual sensation; this figure was significantly larger (53%) among women who did not always use condoms (Kaneko, 2007). In a nationally representative survey of young adults in Norway, of the 20% who used a condom at most recent sex, 15% of men and 9% of women reported they did so to feel more clean; 18% of men and 23% of women reported a condom was used to avoid mess; 2% of both men and women stated they used a condom for fun; 9% of men and 7% of women used a condom to make sex last longer; and 2% of men and 7% of women reported using a condom to facilitate more penetration (Træen & Gravningen, 2011). |

Many participants in a qualitative study invoked a narrative of how “natural” or “proper” heterosex does not involve condoms and use of a common metaphor of “condom-as-killer” highlighted the tension between condoms and sexual pleasure (Braun, 2013). Identifying the most common condom “turn-offs”, Crosby et al. (2008) found:

Almost one-third of both women and men reported problems with condom “feel” during sex (Crosby et al., 2013). For both young women and men, pleasure-related attitudes were more strongly associated with lack of condom use at last PVI than all other socio-demographic or sexual history variables (Higgins & Wang, 2015a). |

Research overwhelmingly associated condoms (versus other methods) with reduced physical pleasure (Fennell, 2014). Though popular discourses about “proper” sex may mean that many young adults find condoms sexually unacceptable, one author argued that common anti-condom sentiments are socially constructed and thus possible to change (Braun, 2013). Pleasure-related reasons and feelings of increased intimacy with skin-to-skin contact influence condom discontinuation and non-use among women (Bolton et al., 2010). Studies including both women and men suggest a number of commonalities by gender. For example, the most common turn-offs relate to loss of pleasure for both men and women (Crosby et al., 2008) . Both women and men report condoms can reduce sexual spontaneity. Associations between women’s and men’s pleasure attitudes and their use/non-use patterns are similar if not identical (Higgins & Wang, 2015a). However, some findings illustrate gender-specific findings. Women were more likely than men to report that their partner experienced sexual discomfort with condom use. Many women also report an inability to negotiate condoms with partners due to reduced pleasure for their male partners, perceived and/or actualized side effects, and trust (Versteeg & Murray, 2008). Findings suggest that more emotional, affective motivations for sex can undermine condom use. More research is needed on how to normalize condom use within sexual contexts of expressing love and pleasing one’s partner (Gebhardt et al., 2006). |

|

Oral Contraception (n=24 here, n=38 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Avellanet et al., 2009) (Battaglia et al., 2012) (Bishop et al., 2009) (Caruso et al., 2011) (Caruso et al., 2013) (Caruso et al., 2009) (Davis et al., 2013) (Di Carlo, Gargano, et al., 2014) (Gardella et al., 2011) (Goldstein et al., 2010) (Goretzlehner et al., 2011) (Guzick et al., 2011) (Kucuk et al., 2012) (Lee et al., 2011) (Machado et al., 2012) (Nappi et al., 2014) (Pastor et al., 2013) (Shahnazi et al., 2015) (Skrzypulec & Drosdzol, 2008b) (Strufaldi et al., 2010) (Wallwiener, Wallwiener, Seeger, Muck, et al., 2010) (Warnock et al., 2006) (Wonglikhitpanya & Taneepanichskul, 2006) (Zimmerman et al., 2015) |

Pooled results from a systematic review show that 85% of women using combined OCs reported an increase or no change in libido (Pastor et al., 2013). In a study of women using Klaira®, a combined multiphasic (4 phases) combined OC pill containing estradiol valerate (E2V)/dienogest (DNG), found significant improvements in Quality of Life (QoL), sexual enjoyment, desire, and pain after 3 and 6 cycles of OC use while adhering to a reduced hormone-free interval (26/2 regimen). This regimen was also associated with improvements in QoL, sexual function, PMS symptoms, and reduced bleeding (Caruso et al., 2011). Another study of Klaira® showed that after 6 months of use, younger women reported significant improvements in sexual pain and older women reported significant improvement in desire and overall sexual function compared to their baseline measures (Di Carlo, Gargano, et al., 2014). A study on continuous cycling regimens (OCs unspecified) reported positive sexual function (mainly improvement in orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) and QoL outcomes related to body pain, general health, and social function after 5 months (2 cycles of 72/4 regimen). Reports of desire, arousal, and lubrication did not change (Caruso et al., 2013). In a study of women diagnosed with PCOS, after 6-9 cycles of Belara® (combined OC containing 30 ug EE/2 mg chlormadinone acetate (CMA) used for 9 cycles), 81% reported significant increases in frequency of partnered sex, orgasm during intercourse, and a significant decrease in masturbation frequency (Caruso et al., 2009). A separate study of Belara® using an extended cycle regimen showed the pill was associated with improvement in: skin problems, symptoms of dysmenorrhea, headache, breast tenderness, withdrawal bleeding, bleeding duration, and libido (Goretzlehner et al., 2011). Results from a randomized, prospective study of women using either a combined OC containing 30 mcg EE/150 mcg LNG or a combined OC containing 20 mcg EE/100 mcg LNG, found significant increases in sexual desire, but this increase was statistically significant only for women using EE20/LNG100 (compared to EE30/LNG150) (Strufaldi et al., 2010). |

Yasmin® use was related to increased pain during sex, decreased libido, issues with spontaneous arousal, and reductions in frequency of weekly sex and orgasm during sex. However, no women in this study met clinical criteria for sexual dysfunction (Battaglia et al., 2012). In a study assessing genetic biomarkers, women with the ll genotype were almost 8 times as likely to be classified as having sexual dysfunction if they used OC (OC type unspecified) (Bishop et al., 2009). Breast tenderness after 1 cycle of combined OC use ranged from 10% (Caruso et al., 2013) to 16% (Wonglikhitpanya & Taneepanichskul, 2006), with a majority reporting that the symptom had resolved by 6 months of use. One study of Italian women found that all 102 women reported a significant reduction in vaginal lubrication after 6 months of using Klaira® (Di Carlo, Gargano, et al., 2014). The use of combined OCs containing ethinylestradiol (EE) may have long-lasting effects on sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) production even after method discontinuation. This may help explain why genital pain disorders do not always resolve with discontinued use of OCs (Goldstein et al., 2010). Pooled results from a systematic review show that 15% of women reported a decrease in sexual desire (libido) after OC use; decreased libido was significantly associated with using pills that containined 15ug ethinylestradiol (EE) (Pastor et al., 2013). Results from a large cross-sectional survey found no significant differences in sexual function based on women using combined OCs containing either androgenic or antiandrogenic progestins, or between different doses of EE. However, women using any type of combined OC reported significantly poorer sexual function scores compared to women not using combined OCs (Wallwiener, Wallwiener, Seeger, Muck, et al., 2010). One randomized, double-blind study provided good evidence that women who suffer from reduced desire and arousal attributed to their birth control pill may find significant improvement in sexual function if they switch to a different pill formulation, particularly those containing E2V/DNG or EE/levonorgestrel (LNG) (Davis et al., 2013). |

Though some women report positive or negative sexual impacts in relation to their use of combined OC, the large majority of women report no impact in sexual function or frequency of sex related to their OC use. Nonetheless, women who do report decreases in sexual function may wish to switch to another OC formulation. Differences in aspects of sexual function such as experiences with sexual pain and levels of sexual desire vary by age and should be contextualized and accounted for in contraceptive research and clinical care. In terms of OCs and sexual pain, combined OCs may be a beneficial treatment for endometriosis-related pelvic pain (Guzick et al., 2011). However, the effects of OCs on experiences with genital pain and interstitial cystitis (Gardella et al., 2011) are not well understood. More research is needed on potential long-term, long-lasting impacts of OC use on women’s sexual pain. The sexual repercussions of seemingly non-sexual side effects of OC use should also be considered; examples include body/facial hair growth changes, and breast tenderness. Aesthetic changes, for example, may be related to improving women’s sexual and social self-esteem as evidenced by increased frequency of partnered sex and reductions in masturbation (Caruso et al., 2009). Genetic differences may influence experiences of depression and sexual function in women taking both SSRIs and OCs. More research is needed to better understand how genetics may play a role in sexual function, particularly in the context of hormonal contraception use (Bishop et al., 2009). Though results remain inconclusive as to the effects of a combined OC pill containing DHEA, the potential for positive sexual function improvements in some women with androgen-sensitivity and/or oral contraceptive-associated sexual dysfunction show promise and requires further investigation (Zimmerman et al., 2015). Women using 3rd generation combined OCs (containing 0.03 mg EE/0.15 mg desogestrel) reported significantly better improvements in sexual function compared to women using 2nd generation combined OCs (low-dose estrogen pills containing 0.03 mg EE/0.15 mg LNG); even though both groups demonstrated higher sexual function after 4 months compared to baseline (Shahnazi et al., 2015). |

|

IUD/IUC/IUS (n=7 here, n=12 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Bastianelli et al., 2011) (Enzlin et al., 2012) (Gomez & Clark, 2014) (Gorgen et al., 2009) (Higgins et al., 2015) (Panchalee et al., 2014) (Skrzypulec & Drosdzol, 2008a) |

In one study of the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS, women reported a significant decrease in sexual pain and a significant increase in sexual desire after one year of use (Bastianelli et al., 2011). A cross-sectional study comparing women who had used either the LNG IUS or copper IUD for at least 6 months found that most women using both IUDs reported changes in menstrual bleeding after IUC placement, though LNG-IUS users were significantly more likely to report shorter menses and less blood flow. Women using either LNG IUS or copper IUD reported similar rates of self-perceived sexual satisfaction (58-60%), sex more than twice per week (48-49%), desire for sex more than twice per week (50-53%), ease in reaching physical arousal (47-54%), and ease in achieving orgasm (76-78%) (Enzlin et al., 2012). A qualitative study described both IUD users’ and non-users’ perceptions of the sexual aspects of IUDs. Sexual benefits included security, or enhanced sexual disinhibition thanks to IUDs’ efficacy, spontaneity, or improved sexual flow, and scarcity of hormones, which meant no/low hormonal influences on libido (Higgins et al. 2015). |

Breast tenderness was reported by 35% of women using the LNG IUS, but resolved by 6 months of use (Bastianelli et al., 2011). Compared to women using copper IUDs, women using the LNG-IUS perceived their method to have a greater negative impact on aspects of their sex life (frequency of sex, arousal and desire); however, orgasm and overall satisfaction with sex did not change with LNG IUS use (Enzlin et al., 2012). One study reported that, after 6 months of use, 12% of women using the LNG IUS reported decreased libido and 35% reported no change in libido. 13% reported experiences with pelvic pain (Gorgen et al., 2009). A qualitative study described both IUD users’ and non-users’ perceptions of the sexual aspects of IUDs. Sexual detractions included string, or negative sexual effects on partner, and sexual aspects of bleeding and cramping, which could affect sexual experiences (Higgins et al., 2015). |

In general, women using copper IUDs reported neither positive nor negative changes in sexual function related to their method. Women who reported existing sexual distress while using either type of IUD were more likely to attribute negative sexual function changes to their IUD usage rather than to other factors in their lives (Enzlin et al., 2012). Most studies show sexual improvements and/or no sexual changes among women using IUC. Studies indicate potential improvements to women’s sexual well-being through IUD/IUS use. For example, decreases in bleeding associated with IUDs for many users are likely to increase sexual acceptability of these methods. Young women also report psycho-sexual benefits of the IUC’s efficacy and no/low hormones (Higgins et al., 2015). Prospective research is needed to better understand the extent to which positive sexual function outcomes in women using a hormonal IUS can be attributed to the method itself versus particular characteristics of the women who choose to use this method (Witting, Santtila, Jern, et al., 2008). |

|

Vaginal Ring (n=4 here n=12 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Caruso et al., 2014) (Merkatz et al., 2014) (Roumen, 2008) (Terrell et al., 2011) |

One study found that women reported an increase in desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and improvement in dyspareunia during 2 extended use cycles (approximately 4.5 months of use). No changes in sexual frequency were observed. FSFI scores increased and sexual distress (FSDS) scores decreased at both follow-up assessments (after 63 days and 126 days of use) (Caruso et al., 2014). In one study, male partners reported never feeling the ring during sex (72%), no change in sexual sensations (92%), and never feeling the ring move during coitus (87%). Though 16% of male partners experienced ring expulsion during sex, only 2 men found this experience disruptive. Most women and their partners found the ring to be highly sexually acceptable and women using the ring expressed fewer issues with vaginal dryness compared to combined OC users. (Roumen, 2008). Adolescent women most willing to try the ring reported more comfort with their genitals and greater knowledge of positive ring attributes (month-long protection, covert use) (Terrell et al., 2011). In one study, over 91% of women using the ring reported a steady increase or no change in sexual desire over 12 cycles (Sabatini & Cagiano, 2006) (see citation in “Multiple Methods” section). |

2% of women using ring reported vaginal discomfort and 4% reported device-related events such as ring slipping out. The most common sexual “problems” with this method pertain to the mechanics of the ring during sexual activity and discomfort with touching their own genitals. Ring-related events (feeling the ring inside vagina, interference with sex, and expulsion) were associated with higher rates of discontinuation (Roumen, 2008). Women less willing to try the ring reported concerns of the ring getting lost inside or falling out of the vagina (Terrell et al., 2011). Mild adverse outcomes included bleeding, nausea, headache, and breast tenderness (Caruso et al., 2014; Roumen, 2008). |

Some women using the ring have reported improvements in sexual function and quality of life and decreases in sexual distress. A small minority of users have reported adverse sexual outcomes such as vaginal discomfort. Higher user satisfaction with the ring is related to ease of removal, not being able to feel the ring during normal use, and either no change or an increase in sexual pleasure and/or sexual frequency. Women who were more satisfied with the method (including positive sexual attributes of the method) were more likely to adhere to correct use and to continue use over time (Merkatz et al., 2014). Among women less comfortable touching own genitals, providing alternative strategies such as wearing gloves or using an applicator to insert/remove the ring may facilitate willingness to try the method (Terrell et al., 2011). The extent to which ring users enjoy and/or find bothersome vaginal wetness associated with use should be explored to better understand sexual acceptability (Battaglia et al., 2014) (see citation in “Multiple Methods” section). |

|

Implant (n=5 here n=7 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Aisien & Enosolease, 2010) (Di Carlo, Sansone, et al., 2014) (Duvan et al., 2010) (Gezginc et al., 2007b) (Visconti et al., 2012) |

Participants in one study exhibited significantly increased FSFI scores at 3 months, showing improvement in domains measuring arousal, orgasm, satisfaction and pain; no changes were observed at 6 months compared to 3 months (Di Carlo, Sansone, et al., 2014). Visconti et al. (2012) found that by 3 months, women reported statistically significant improvements in frequency and intensity of orgasm, better sexual satisfaction, and less sexual anxiety. By 6 months, scores measuring sexual pleasure, personal initiative, orgasm frequency, sexual satisfaction, discomfort and anxiousness had all improved significantly from baseline. Weekly frequency of sex increased significantly by 6 months compared to baseline (Visconti et al., 2012). |

A small minority (2%-9%) of women using the implant reported reduced libido (Aisien & Enosolease, 2010) (Duvan et al., 2010) (Gezginc et al., 2007b). Bleeding profiles associated with implant use after one year of use were variable. The range from several studies is as follows:

Other reported side effects that may have sexual repercussions included the following:

(Aisien & Enosolease, 2010) (Duvan et al., 2010) (Gezginc et al., 2007b) (Visconti et al., 2012) |

Several studies indicate improvements in women’s sexual functioning and satisfaction with implant use. The authors of one study (Visconti et al., 2012) attributed an increased sense of security from pregnancy as leading factor in increased frequency of sex and improvements in sexual function associated with this method. A minority (<10%) of users report libido reductions. A minority of women also report a number of bleeding changes and/or side effects such as breast tenderness, weight gain, or headaches that could decrease women’s sexual well-being. 88% of women in one study reported no negative feelings about the method (Aisien & Enosolease, 2010), though 25% of women in another study discontinued Implanon® within the first year of use; 35% discontinued due to bleeding irregularities and 10% stopped due to interference with sexual function (Gezginc et al., 2007b). Tolerability of irregular bleeding patterns associated with the implant should be further explored in regards to sexual acceptability. |

|

Injectable (n=2 here, n=8 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Gubrium, 2011) (Wanyonyi et al., 2011) |

After 6 months of Depo® use, women reported marginally significant improvements in physical health, which could have sexual repercussions. Women reported no significant changes in either mental health or sexual function after 6 months of use of injectable contraception (Wanyonyi et al., 2011). | Results from a qualitative study illustrate decreased libido (sexual desire) as a key theme associated with Depo® use. Participants linked this libido decrease with emotional and body image changes (Gubrium, 2011). 33% of women reported menstrual irregularities. Main reasons for discontinuation in one study included: menstrual irregularity (27%); reduced libido (13%); and weight gain (20%) (Wanyonyi et al., 2011). |

Few studies report improvements to women’s sexual well-being with use of injectable contraception. Studies suggest that a minority of women experience libido reductions on this method, which may also be related to factors such as weight gain and changes in body image, unpredictable bleeding, and emotionality. Side effects associated with the shot are not experienced singly, but as a constellation of factors (examples: weight gain leads to changes that, taken together, contribute to the sex-acceptability of the method). |

|

Female Condom (n=7 here, n=8 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Latka et al., 2008) (Mack et al., 2010) (Mathenjwa & Maharaj, 2012) (Okunlola et al., 2006) (Sobze Sanou et al., 2013) (Telles Dias et al., 2006) (van Dijk et al., 2013) |

Studies have documented a number of positive sexual aspects of the female condom, including the following: high level of sexual comfort due to sufficient lubricant and better lubrication compared to male condom; low risk of breakage, especially during rough sex; ability to accommodate all penis sizes; reduced interruption of sexual encounter due to ability to insert before intercourse; greater protection of the outer labia; preferred the smell to the male condom; lack of side effects; increased protection from pregnancy & STIs/HIV; female-controlled use; lower likelihood of allergic reaction compared to male condom; increased ability to relax and enjoy sex; increased sensation; clitoral stimulation through external ring; and massage of head of penis with internal ring (Latka et al., 2008) (Mack et al., 2010) (Mathenjwa & Maharaj, 2012) (Telles Dias et al., 2006) (van Dijk et al., 2013). | Initially, women in one study reported that the method’s design, particularly the internal ring, made it difficult (and painful) to insert and remove. However, after several uses, more than half of participants preferred the female to the male condom (Mack et al., 2010). Among female condom users, the most common complaint (30%) was poor sexual satisfaction associated with use. 22% reported difficulties with insertion, and 5% experienced pain during intercourse when using the female condom (Okunlola et al., 2006). Common complaints included noise during intercourse, stiffness of internal ring, resistance of partners to use, and excessive lubrication (Telles Dias et al., 2006). |

The preconceived notion that female condoms decrease sexual pleasure can be a barrier to use among both men and women (Sobze Sanou et al., 2013). Women in a number of studies discussed difficulties with insertion and/or aesthetic detractions such as noise and stiffness of the internal ring. However, women in a variety of studies reported myriad sexual advantages to female condoms, especially compared to male condoms. Pleasure-related aspects experienced by both men and women increased acceptability and long-term use of this method. Though women’s first impressions of the female condom may be negative, particularly regarding insertion and large size, perceptions are likely to improve with time and practice. Women with greater personal autonomy were more likely to report sustained use (Telles Dias et al., 2006). |

|

Female Sterilization (n=3 here, n=7 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Dias et al., 2014) (Schaffir, Fleming, et al., 2010) (Smith et al., 2010) |

92% of women were satisfied with the procedure and would recommend it to friends (Dias et al., 2014). After controlling for age and other socio-demographic characteristics, women with a tubal ligation were significantly less likely than non-sterilized women to experience negative sexual outcomes such as a lack in sexual desire, issues with vaginal lubrication, or taking too long to orgasm. Sterilized women reported significantly higher levels of sexual and relationship satisfaction and sexual pleasure compared to non-sterilized women (Smith et al., 2010). |

After tubal ligation, women reported significantly more bleeding, premenstrual symptoms, dysmenorrhea, and noncyclic pelvic pain; they also reported significantly reduced libido and fewer sex acts per week (Dias et al., 2014). 37% of women undergoing sterilization agreed with a statement that they would have less sexual desire after procedure (Schaffir, Fleming, et al., 2010). |

Studies report both positive and negative impacts of sterilization on aspects of sexual function, yet women report overwhelmingly high rates of satisfaction with the method, highlighting the aspect of safety and freedom from pregnancy as important aspects of method acceptability. Many women report sexual concerns in anticipation of gynecological procedures. We recommend that physicians address sexual concerns with women in more detail before surgery and continue to address concerns as needed post-procedure. |

|

Vasectomy (n=3 here, n=5 in the table, please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Al-Ali et al., 2014) (Bunce et al., 2007) (Shih et al., 2013) |

Female partners in one study reported significantly more positive sexual function after vasectomy. No significant changes were reported in men’s sexual function (Al-Ali et al., 2014). Men often cited seeking vasectomy to allow their female partners to discontinue hormonal methods (Bunce et al., 2007). |

Loss of manhood and misconceptions around negative impacts on men’s sexual function, desire, and performance were cited by men and their partners as reasons for not selecting vasectomy. Both male and female participants cited potential for infidelity as both a positive and negative aspect of vasectomy (Shih et al., 2013). Partner influence, including partner’s approval, was an important factor in men seeking vasectomy (or not) (Bunce et al., 2007). |

Though vasectomies are performed on male bodies, women may experience positive sexual effects from this method, potentially related to security against unwanted pregnancy and/or no longer having to take contraceptive responsibility. Cultural constructions of gender relating to infidelity and manhood and sexuality may deter some men and their partners from vasectomy. Highlighting the rapid return to prior sexual function is an important component in vasectomy counseling and could increase knowledge and acceptability of the procedure (Shih et al., 2013). |

|

Withdrawal (n=4 here, n=5 in the table, please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Higgins & Wang, 2015b) (Ortayli et al., 2005) (Rahnama et al., 2010) (Sirkeci & Cindoglu, 2012) |

For both women and men, those who felt condoms could diminish sexual pleasure were significantly more likely to have used any/only withdrawal at last sexual intercourse (Higgins & Wang, 2015b). Iranian women who use withdrawal cited dissatisfaction with sexual sensation associated with condom use and partners’ unwillingness as reasons for not using modern (more highly effective) methods of contraception (Rahnama et al., 2010) |

Turkish men who did not use withdrawal reported anxiety, decreased sexual pleasure, and dislike of coital-dependent methods as reasons for non-use. Almost all current withdrawal users cited reductions in sexual pleasure with the method, but less so than with male condom use (Ortayli et al., 2005). 34% of women reported decreased sexual enjoyment when using withdrawal; 42% perceived their partner to experience decreased enjoyment as well (Rahnama et al., 2010). Participants acknowledged female sexual pleasure as a consideration for using withdrawal as well as difficulties with climax control for some men (Ortayli et al., 2005). |

Findings suggest that sexual acceptability issues may play a larger role in shaping withdrawal and other contraceptive practices than acknowledged by prior research. Withdrawal reduced both women’s and men’s sexual well-being in a number of studies; other studies suggested that couples were more likely to use withdrawal when they experienced pleasure-reductions with other methods (e.g., male condoms). Authors acknowledge the need for climax awareness and control for male partners in order for withdrawal to work successfully (Freundl et al., 2010). |

|

Diaphragm (n=2) |

(Sahin-Hodoglugil et al., 2011) (Thorburn et al., 2006) |

Current users described the diaphragm as valuable to women’s autonomy with a female-initiated method and the ability to use covertly. Women and men enjoyed the increased sexual pleasure when using the diaphragm with a gel (Sahin-Hodoglugil et al., 2011). 66% of women who had never used a diaphragm perceived that it “does not decrease sexual pleasure” (Thorburn et al., 2006). |

Less than 25% of women in one study felt confident in using the method correctly when sexually excited or in the heat of the moment. 17% of women preferred methods that require no genital touching (Thorburn et al., 2006). Current diaphragm users reported the need for partner negotiation as an attribute that contributed to overall acceptability (Sahin-Hodoglugil et al., 2011). |

Few study participants reported negative sexual attributes of diaphragms, though (like condoms and other coitus-dependent methods) this method may hinder sexual flow and spontaneity. Women acknowledge the difficulty of stopping to insert one’s diaphragm in the heat of the sexual moment. The ability to insert the diaphragm before sexual activity increased its acceptability. Along these lines, comfort with genital touching will impact acceptability. |

|

Natural Family Planning (NFP) (n=1 here, n=3 in the table; please see “multiple methods” section below for more information) |

(Freundl et al., 2010) | Results from a systematic literature review highlighted sexual self-control and increased body awareness as positive attributes of NFP reported by users (Freundl et al., 2010). | Natural family planning methods may disallow spontaneity as most methods require abstaining from PVI during peak periods of fertility (Freundl et al., 2010). | Couple-focused research may enlighten effective sexual communication strategies of couples who successfully use NFP or other methods negotiated by both partners. Highlighting and promoting strategies for intimacy and other sexual activities that don’t involve PVI may increase the sexual acceptability of NFP methods; more research is needed. |

|

EC Pills (n=1) |

(Escajadillo-Vargas et al., 2011) | N/A | Regression analyses from a nested case-control study indicate that women using oral EC in the past 3 months had significantly greater odds for increased risk of sexual dysfunction (Escajadillo-Vargas et al., 2011). | More research is needed to better understand the characteristics of women who use EC and how oral EC use might be related to sexual function. |

|

Multiple Methods Measured in the Same Study (n=19) |

(Battaglia et al., 2014) (Davison et al., 2008) (Elaut et al., 2012) (Fataneh et al., 2013) (Gabalci & Terzioglu, 2010) (Guida et al., 2014) (Halmesmaki et al., 2007) (Higgins, Hoffman, et al., 2008) (Mohamed et al., 2011) (Nishtar et al., 2013) (Ott et al., 2008) (Roumen, 2007) (Sabatini & Cagiano, 2006) (Sanders, Smith, et al., 2014) (Schaffir, Isley, et al., 2010) (Smith et al., 2014) (Stewart et al., 2007) (Tabari et al., 2012) (Witting, Santtila, Jern, et al., 2008) |

In a genetic study using a within-subject, crossover study design with random-order use of 3 contraceptive methods (combined OCs, progestin-only pills, and the ring), both partners’ level of sexual desire was statistically significantly higher among women using the vaginal ring (Elaut et al., 2012). Compared to women using the ring, pill, or no method (control group), after 6 months, implant users reported the most significant improvements in sexual discomfort, anxiousness, personal initiative, and fantasy. All method users reported significantly more sexual pleasure, satisfaction and higher orgasm frequency at 6 months compared to controls (Guida et al., 2014) Women reported that the ring was more likely to interfere with sex compared to the pill and significantly more women reported that their sex partners preferred the pill (Stewart et al., 2007). A systematic review found either improvement or no change in sexual function and sexual experience in women using both implants and IUD/IUS (Sanders, Smith, et al., 2014). |

Results from a prospective study found that women using drospirenone-containing OC (Yasmin®) reported significant reductions in sexual frequency and orgasm during sex, and reported more pain during sex after 6 months of use compared to baseline measures. After 6 months of use, women using Yasmin® and vaginal ring demonstrated significant decreases in sexual function scores compared to baseline assessment (Battaglia et al., 2014). Results from a case-controlled study found that, compared to controls, women using any contraceptive method reported significantly poorer scores in the domains measuring desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain, and satisfaction (Fataneh et al., 2013). Controlling for a number of socio-demographic and relationship characteristics, results of one cross-sectional study demonstrated that male condoms, either used alone or in conjunction with hormonal methods (dual use), were most strongly associated with decreased sexual pleasure (Higgins, Hoffman, et al., 2008). In a randomized, prospective trial conducted from method initiation to 12 months or method discontinuation, findings show that, compared to pill users, ring users reported significantly more experiences with vaginitis, decreased libido, and ring-related problems. Conversely, compared to ring users, women using combined OCs reported significantly more experiences with increased weight, acne, and emotional lability (Mohamed et al., 2011). Results from a large cross-sectional study show that a regression controlling for a number of socio-demographic and relationship characteristics indicated that women using hormonal contraception experienced significantly less frequent sex, and significantly more problems with arousal, pleasure, orgasm, and vaginal lubrication compared to women using non-hormonal methods (Smith et al., 2014). |

Studies comparing sexual outcomes for multiple methods show mixed findings. However, studies of multiple methods do highlight that contraceptives can affect a wide range of sexual domains for women, from inference with sexual flow to partner preference to sexual functioning and pleasure to more general sexual satisfaction. Most studies of multiple methods compare and contrast various formulations of hormonal methods. Studies with sufficient sample sizes to compare a wider range of methods are warranted. Researchers have paid especially little attention to women’s sexual experiences with long-acting reversible contraception, or LARC (implants and IUDs) in the past 10 years. With the recent public health focus on LARC, more research is needed, especially in the US context (Sanders, Smith, et al., 2014). In one study, the authors note that dual users are likely “erotizing safety” associated with doubling up on pregnancy and STI prevention methods. (This group reported higher sexual satisfaction levels than pill-only or condom-only users (Higgins, Hoffman, et al, 2008).) Adolescents and young women often report frequent method switching, starting, and stopping, all of which reflect their dynamic lives and intimate experiences. More research is needed on how mood influences interest in sex and reasons for method switching or discontinuation among young women (Ott, Shew et al, 2008). |

Methods are presented in descending order per number of citations, with those methods most commonly cited appearing first and articles assessing multiple methods (n=19) located at the end of the table.

For the purpose of this review, our focus pertains to currently available contraceptive methods that people use primarily for pregnancy prevention. We acknowledge that many women use hormonal methods in particular for a variety of noncontraceptive benefits, from relieving severe menstrual pain to reducing acne or excess hair growth. One nationally representative survey found that upward of 14% of oral contraceptive users in the United States reported using the pill for noncontraceptive purposes only (Jones, 2011). However, given that the overwhelming majority of contraceptive methods are used at least in part to prevent pregnancy, we have focused our attention here on healthy populations of reproductive age and—to the best of our knowledge, based on the source—of reproductive capacity. Examples of articles we thus reviewed but ultimately excluded comprised studies of oral contraceptive use among postmenopausal women, acceptability of rectal microbicides among gay men, and contraceptive practices among women with special health issues (e.g., epilepsy, cancer, or endometriosis), though certainly these populations require tailored, patient-centered contraceptive care. However, we acknowledge that relatively healthy, reproductive-age people often use contraception for a wide variety of purposes, not only to prevent pregnancy, and that these purposes may well affect sexual acceptability.

Although we highlight men’s roles when appropriate, we focus primarily on women’s sexual experiences of contraceptive methods given the dearth of women’s perspectives in the existing literature. Moreover, though condoms (and some of the other multipurpose technologies) can prevent transmittal of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and STIs for a variety of sexual acts, and can affect both partners involved, we focus here on penile–vaginal intercourse—and primarily on women’s experiences. That said, we make no assumptions about the sexual identities of women who have penile-vaginal intercourse and/or who use contraception. A growing body of research suggests that a large proportion of unintended pregnancies occur among sexual minority women (Charlton et al., 2013; Rosario et al., 2014), and many sexual minority women thus face situations in which they wish to prevent pregnancy in a sexually acceptable way.

Finally, this review does not rigorously evaluate the methodological quality of all available studies; interested readers should refer to such critiques elsewhere (Bancroft, Hammond, & Graham, 2006; Graham & Bancroft, 2013a, 2013b; Hong, Wu, & Fan, 2008). Rather, our purposes here are, first, to enlighten and broaden the concept of how contraceptives can influence sexuality and, second, to use the wider literature to overview method-by-method sexual acceptability when considered in a context more comprehensive than sexual physiology alone.

PART 1: BUILDING A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF SEXUAL ACCEPTABILITY OF CONTRACEPTION

In their 2005 piece, “Critical Issues in Contraceptive and STI Research,” Severy and Newcomer defined acceptability as “the voluntary sustained use of a method in the context of alternatives” (p. 47). They argued that especially since most women and men would rather not have to use a contraceptive method during sex, contraception decisions really involve finding “the least bad alternative.” Contraceptive methods are only effective if used, and thus they must be designed to fit people’s needs rather than vice versa. A variety of factors will shape acceptability for both partners, including effectiveness, aesthetics (viscosity, taste, smell), how one obtains and applies/uses the method, its presence or “absence” during sex (including ability to be used covertly), and its actual or perceived effect on sexual intimacy. “Sexual pleasure,” they wrote, “plays a central role in determining user perspectives regarding new methods” (p. 45).

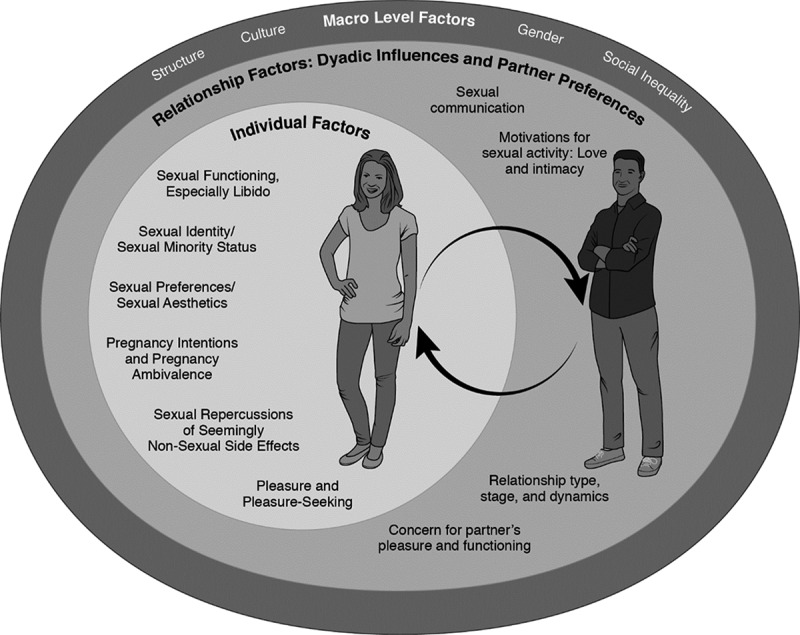

Severy and Newcomer’s eroticized, user-first version of acceptability serves as a cornerstone of our own model (Severy & Newcomer, 2005). We are similarly guided by other scholars who have described various pathways through which contraceptives may affect sexuality and sexual well-being (Bitzer, 2010; Higgins & Hirsch, 2008), including hormonal pathways (Bancroft et al., 2006; Graham & Bancroft, 2013a, 2013b). Here, we attempt to build an even broader, more ecological approach to the sexual acceptability of contraception, exploring three major levels of influence/pathways: macro (gender, cultural, race/ethnicity, place, inequality, and structure), social (relationship and partner factors), and individual. We argue that the best research on this topic will contextualize contraceptives within the sexual, social, and cultural settings in which they are selected and used (Woodsong & Alleman, 2008). Please refer to Figure 1 for a visual rendering of the model, particularly how the various layers interact and/or embed within one another.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the sexual acceptability of contraception.

Macro-Level Factors: Gender, Social Inequality, Location, Culture, and Structure

The outermost layer of the model, macro-level factors, serves as the context in which individuals and couples experience contraceptives in their lives.

Gender

All women’s experiences of sexuality and contraception will be filtered through gender. Here, we briefly highlight three relevant aspects: sexual and reproductive autonomy, sexual scripts, and sexual empowerment.

Sexual and Reproductive Autonomy

Though a key objective of this review is to address “the pleasure deficit” in family planning research, we of course acknowledge that many women face challenges to sexual autonomy, let alone pleasure. At a basic level of sexual rights, gendered power imbalances may undermine sexual autonomy and contraceptive use. Women may not be able to have only consensual, desired sexual experiences (Billy, Grady, & Sill, 2009; Vannier & O’Sullivan, 2010) and/or be able to regulate their fertility as they wish (Chacham, Maia, Greco, Silva, & Greco, 2007; East, Jackson, O’Brien, & Peters, 2011). As a result of these gendered power imbalances, one group of scholars has advocated for the replacement of the concept of safe sex (i.e., sexual activity that’s protected from unintended pregnancy and/or STIs) with woman-controlled safe sex (Alexander, Coleman, Deatrick, & Jemmott, 2012). Along those lines, the call for women-controlled dual-prevention technologies, such as female condoms and microbicides, consistently highlights the notion that women need access to methods that they can use covertly, regardless of their male partners’ knowledge or participation (Mathenjwa & Maharaj, 2012). Though woman-controlled safe sex is a powerful and necessary feminist concept, it may be less relevant to those situations in which women’s heterosexual activity is consensual and, ideally, mutually pleasurable. However, for at least some women, gender-based power differences may mean that using contraceptives to enhance well-being is of less immediate salience than, say, maintaining sexual safety or minimizing sexual harm.

Gender inequality may affect sex and contraception in more subtle ways, too. For example, women are more likely to be depressed than men (Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000); they may also face more stress and fatigue, particularly with young children in the household (Bird, 1997). Depression, stress, and use of psychotropic drugs can undermine both sexual functioning (Echeverry, Arango, Castro, & Raigosa, 2010; Garbers, Correa, Tobier, Blust, & Chiasson, 2010) and effective contraceptive use (Stidham Hall, Moreau, Trussell, & Barber, 2013).

Sexual Scripts

Gendered sexual scripts serve as another strong influence on women’s sexual and contraceptive experiences (Levin, 2010). Strongly rooted cultural norms contrast gender expectations in sexual desire and pleasure, the degree to which one’s sexuality and sex “drive” are controllable, and who bears primary responsibility for sexual protection and pregnancy prevention (Borges & Nakamura, 2009; Brown, 2015; Campo-Engelstein, 2013; Gubrium & Torres, 2013; Hust, Brown, & L’Engle, 2008). The stage is set for women to enact a gendered responsibility for contraception that is often disconnected from pleasure seeking—traditionally viewed as men’s domain. For example, in an analysis of direct-to-consumer contraceptive advertising, investigators concluded that “[t]he viewer of these websites comes away with the impression that for men sex is supposed to be fun and feel good and for women sex is risky and not to be done without taking precautions” (Medley-Rath & Simonds, 2010). Others have documented the tension women may feel between, on the one hand, assuming bodily control and independently making contraceptive decisions and, on the other hand, wanting to share responsibility as a couple (Lowe, 2005). Women may feel greater social pressure to maximize their independence through contraception than to achieve sexual empowerment (Lowe, 2005). One scholar analyzed young women’s struggle for/with the needs of two different bodies: the “sexy body” versus the “fertile body” (Keogh, 2006). Most cultural scripts of masculinity and sexuality do not involve these latter tensions. While both women and men may describe how condoms, withdrawal, and/or vasectomy can decrease men’s pleasure (Marchi, De Alvarenga, Osis, & Bahamondes, 2008), fewer scripts exist on how contraceptive methods may potentially diminish or improve women’s pleasure and sexual well-being.

Sexual Empowerment

Scholarship also draws ties between sexual empowerment and contraceptive practices, with women who are more socially and sexually empowered more likely to use the contraceptives they wish (Crissman, Adanu, & Harlow, 2012; Do & Kurimoto, 2012; Gipson & Hindin, 2007). 3 Hensel et al. (2011) argued that even though women may not think of contraception as a “sexy” part of their lives, various studies link more successful contraceptive use with women’s ability to express sexual desire and to advocate on their own behalf for pleasure. Having an enriched view of one’s sexuality and sexual health have also been associated with oral contraceptive use (versus nonuse) in Spain (Carrasco‐Garrido et al., 2011) and contraceptive use more generally among young women in the United Kingdom (Free, Ogden, & Lee, 2005). In sum, endeavoring to improve women’s sexual perceptions of themselves is not only an important goal in its own right; it is also good for increasing (consensual, acceptable) contraceptive use.

Social Location: Race/Ethnicity, Social Class, and Other Axes of Inequality

Although gender is surely an influential shaper of contraceptive and sexual experiences, so too are other axes of inequality, including but not limited to race/ethnicity, social class, sexual identity, dis/ability, and nation. Furthermore, as feminist scholars of intersectionality have argued, gender varies according to one’s social location (Andersen & Hill Collins, 2013). For example, constructions of inner-city, low-income, Black women’s sexuality may differ considerably from suburban, middle-class, White women’s sexuality. Along these lines, gender is not the only or even the primary framework through which women experience their sexuality or use contraception. For example, in one qualitative study of contraceptives’ sexual acceptability, poor women described trying to minimize painful side effects in light of other chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, arthritis, and depression; in comparison, socially advantaged respondents reported fewer chronic health conditions and could focus more on maximizing sexual pleasure through contraceptive use (Higgins & Hirsch, 2008). Though all women have a right to safe and pleasurable sexual experiences, sexual enjoyment may be less of an immediate goal for women in resource-deprived and/or conflict-torn settings.

Unfortunately, histories of racism, classism, and “stratified reproduction” (Ginsburg & Rapp, 1995) mean that contraception is not always a tool of individual feminist empowerment; it can also be used as a means of social control and disempowerment. A disturbing number of both prior and current reproductive injustices have used contraceptives to limit the fertility of socially disadvantaged women, especially poor women of color (Roberts, 1997). In the 1990s, U.S. policymakers supported numerous programs to encourage or coerce socially disadvantaged women to use Norplant, an implantable, five-year contraceptive method associated with a number of serious side effects. Proposed legislation and judicial decisions included cash incentives for Norplant insertion, welfare benefits contingent upon insertion, and even Norplant insertion to avoid jail time (Gold, 2014). In the contemporary United States, African American women are still significantly more likely than White women to have been sterilized, even after accounting for age, insurance status, number of children, and education (Borrero et al., 2007). Women with public or no insurance are also significantly more likely to have been sterilized compared to women with private insurance (Borrero et al., 2007). Another recent study documented that providers were more likely to recommend long-acting methods such as IUDs to women of color and poor women than to White women and middle-class women (Dehlendorf et al., 2010). In sum, socially disadvantaged women have been and currently are discouraged and/or prevented from having (more) children. Acknowledging these injustices does not mean we have to dispense with contraceptive promotion and/or a focus on sexual acceptability. On the contrary, recognizing these histories can help us understand the potential for such abuses, and develop counseling methods and policies that are more client centered.

One framework we can use to consider and address the unique needs of socially disadvantaged women is reproductive justice, a term dating back to 1994, when African American women activists combined the terms reproductive rights and social justice (Luna & Luker, 2013). According to one reproductive justice organization, “[R]eproductive justice exists when women and girls and all people have the social, political, and economic power and resources to make health decisions about our gender, bodies, and sexuality for ourselves, our families, and our communities” (Reproductive Justice Collective, 2015). At a fundamental level, a reproductive justice approach means giving all women knowledge and access to all contraceptive methods but also valuing women’s own needs over the desire to decrease certain groups’ birthrates and/or the need to meet certain institutional thresholds or metrics, such as local strategies to reduce teen pregnancies. Moreover, contraceptive services should be only one small part of a larger host of efforts to improve the lives of socially disadvantaged women—from reducing institutionalized racism and sexism to improving educational opportunities, community safety, and employment possibilities.

Culture

While gender and other social inequalities exist in every country in the world, widespread and meaningful cultural differences influence the sexual acceptability of contraception. For example, compelling comparative analyses of the United States and the Netherlands document how differences in sexual cultures may help explain large disparities in adolescent contraceptive use and teen pregnancy in these countries (Brugman, Caron, & Rademakers, 2010; Schalet, 2011). Sexual norms taken for granted by most North Americans—for example, the idea of adolescents’ “raging hormones”—may not exist within the Dutch setting (Brugman et al., 2010; Schalet, 2011). In one study, U.S. girls mentioned themes of driven by hormones and peers, unprepared, satisfying him, and uncomfortable and silent parents; in contrast, prominent themes among Dutch girls were motivated by love, control of my own body, and parents as supporters and educators (Brugman et al., 2010). Such research helps illustrate how sex is “not a natural act” (Tiefer, 2004) but a series of socially constructed scripts—scripts into which contraceptives may or may not fit. A number of researchers have also documented the multitude of sexual and contraceptive scripts within countries, with variation by race/ethnicity, social class, and age cohort (Chen, 2008; Gillmore, Chen, Haas, Kopak, & Robillard, 2011; Sandberg, 2011). For example, cultural differences exist in the degree to which people uphold the virgin/whore dichotomy for women (Gubrium & Torres, 2013) or the degree to which women are sexually stigmatized for using contraception or carrying condoms (Oyedeji & Cassimjee, 2006). Taken cumulatively, these studies remind us that various layers of the sexual acceptability model will take on different profiles for people in different circumstances, either within or across cultures. We thus must endeavor for synthesis with local ideologies when promoting sexually acceptable contraception (Gilley, 2006).

Structure

In our review process, we located few articles documenting how structural factors may shape contraception’s sexual acceptability. However, levels of global and local social advantage are likely to affect both sexual well-being and contraceptive practices. For example, poverty and structural disadvantage may mean that women have more pressing concerns (e.g., finding stable housing and employment, establishing safety—either sexual or otherwise) than having contraceptives that optimize their sex lives (Higgins & Hirsch, 2008). In many settings, young women may be motivated to sexually engage with older men in exchange for goods, income, and/or school fees, and these motivations could undermine contraceptive use in general, let alone pleasurable contraceptive use (Cockcroft et al., 2010). Two studies of withdrawal use in Turkey suggest that education, employment, and social class—that is, one’s place in the social milieu—will affect not only sexuality but also preferred contraceptive methods. More educated, liberal Turkish women tend to use withdrawal less frequently than women from lower socioeconomic strata (Cindoglu, Sirkeci, & Sirkeci, 2008), a finding that led authors of a similar study to conclude that “women with better social and physical resources prefer withdrawal less” (Sirkeci & Cindoglu, 2012, p. 614). In sum, women’s contraceptive choices and practices are not haphazard, nor do they reflect the users’ contraceptive knowledge and access alone. Rather, they are shaped by a variety of structural, cultural, and gendered variables and processes, many of which affect sexual experiences and practices.

Relationship Factors: Dyadic Influences and Partner Preferences

Even though contraceptives are used within sexual and relational interactions, contraceptive acceptability research largely has been remiss in assessing partnership factors. In some ways, this omission has been purposeful: Research on women-controlled technologies has deliberately tried to provide women with contraceptives they could use independently of their partners’ knowledge or participation (Mathenjwa & Maharaj, 2012; Naidu, 2013). In other ways, this omission has come with a cost, particularly in terms of fully understanding the sexual aspects of contraceptives. One scholar argued that inattention to partner influences, particularly gendered power dynamics, could help explain why the theory of planned behavior has been good at predicting intentions to use contraceptives but less adequate in predicting their actual use (McCave, 2010). And many women want to choose and use contraceptive methods in consultation and/or collaboration with their partners. As Woodsong and Alleman (2008) have argued, “Although woman-initiated use is an important goal, […] the need for men’s cooperation or agreement must be addressed” (p. 171). Unfortunately, we do not have adequate space to wholly review the literature on associations between intimate relationships, partner factors, and contraceptive use. However, we wish to highlight at least a few relationship-level factors that connect directly to contraceptive practices and contraception’s sexual acceptability. In the conceptual figure (Figure 1), these relationship-level factors are nested within the larger macro-level factors and work interactively with women’s individual sexual experiences and preferences.

Motivations for Sexual Activity: Love and Intimacy

One’s motivations for engaging in sexual activity, particularly those related to love and intimacy, can strongly affect contraceptive behaviors, especially nonuse (Bjelica, 2008). In a qualitative study with African American women, participants listed a variety of reasons people might engage in sex (e.g., love/feelings, for fun, curiosity, pressured, for money, for material things), and they linked lack of condom use most strongly with love and intimacy motivations (Deardorff, Suleiman, et al., 2013). In a U.S. focus group study with adult women, participants gave 146 reasons for having unprotected sex (Nettleman, Brewer, & Ayoola, 2007). In a follow-up survey study, the investigators found that 56% of family planning client respondents were having unprotected intercourse, and “being in a long term or strong relationship” was the second most common reason for nonuse of contraception (the first was “lack of thought/preparation”) (Nettleman, Brewer, & Ayoola, 2009). In a study of Norwegian young adults, “being in love” helped explain reasons for engaging in unprotected intercourse (Træen & Gravningen, 2011). A U.S. daily diary study of young adult women showed that feelings of love and sexual interest can work interchangeably to lower odds of any contraceptive use on any given day (Tanner, Hensel, & Fortenberry, 2010). Taken cumulatively, these studies suggest a common phenomenon in which contraceptive use can be undermined by sexual motivations of expressing and experiencing love and intimacy with a partner. For these reasons, methods that can be used outside of the sexual moment may be a more sexually acceptable choice to some women.

Sexual Communication

It’s easier for most people to actually engage in sexual activity than to talk about it (Norman, 2013). However, a couple’s (in)ability to communicate, sexually and otherwise, can affect contraceptive behaviors. For example, a U.S. study of African American adults found that many couples lacked communication skills and were thus more likely to nonverbally communicate about methods such as condoms (Bowleg, Valera, Teti, & Tschann, 2010). Young adult Latinos in one U.S. study reported communicating about pleasure and satisfaction (often nonverbally) before talking about contraception (including condoms)—and that all these conversations could be difficult (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013). Not surprisingly, couples with stronger verbal sexual communication skills have been found to use condoms more often (Norman, 2013). In sum, contraceptive researchers and practitioners should stay mindful of the actual contexts in which couples use and communicate about pregnancy prevention, remembering that many people may need to build sexual communication skills (DiClemente, Wingood, Rose, Sales, & Crosby, 2010).

Relationship Type, Stage, and Dynamics

In their analysis of the 2006 National Couples Survey, Grady, Klepinger, Billy, and Cubbins (2010) found that men’s and women’s contraceptive method preferences are both significantly related to the couples’ method choice. They found no gender difference in the magnitude of these relationships, although women in married and cohabiting relationships appeared to have greater power over method choice than women in dating relationships. In other words, relationship type may moderate the ways in which relationship influences and gendered power dynamics affect contraceptive use—a finding upheld in a study of adolescent Finnish women who were more likely to be active agents in both sexual activity and their own contraceptive use in the context of longer-term rather than more casual relationships (Kuortti & Lindfors, 2014). Relationship length is also closely related to sexuality and contraception, with studies across the world documenting more common condom use at the beginning of a partnership, then waning as trust grows and the desire for more intimate sex waxes (Braun, 2013; Osei, Harding Mayhew, Biekro, & Collumbien, 2014; Tsuyuki, 2014). Regardless of relationship type or stage, relationship dynamics can play a role in contraceptive practices, with both individual and couple preferences sustaining an important influence. A U.S. longitudinal study of young adult couples showed that less “dominant” individuals were more likely to cater to their partners’ preferences, and the intentions of those with more relationship power (often, but not always, men) were more likely to exert a direct influence on condom (non)use (VanderDrift, Agnew, Harvey, & Warren, 2013).

Concern for Partners’ Pleasure and Functioning

Closely related to the latter theme, many women may make contraceptive decisions to try to maximize their partners’ pleasure, if not their own (Higgins & Hirsch, 2008). While both women and men have reported how condoms, withdrawal, and/or vasectomy can decrease men’s pleasure (Bunce et al., 2007; Marchi et al., 2008; Rahnama et al., 2010), few studies document men’s reports of how contraceptive methods may potentially diminish or improve women’s pleasure. Moreover, to help protect men’s sexual self-esteem, women may not suggest condoms if they worry their partner will not be able to sustain an erection (Ekstrand, Tydén, & Larsson, 2011). In a U.S. qualitative study of the sexual acceptability of IUDs, when asked how they thought IUDs might affect sexuality, young women overwhelmingly first mentioned the potential for the string to poke the penis; that is, of all the possible sexual aspects of IUDs, the one that was most top-of-mind was the one that could affect their partners, not themselves (Higgins, Ryder, Skarda, Koepsel, & Bennett, 2015). This theme is in keeping with feminist sexuality research, which has described how women are socialized to be more partner oriented in sex, as well as how women are less culturally encouraged to develop their own sexual subjectivity or perceived right to sexual pleasure. Thus, although researchers could do far more to document and address contraceptives’ sexual acceptability, larger cultural shifts are also needed to increase women’s sexual selfhood and empowerment.

Individual Factors

Women have individual sexual experiences, profiles, and preferences that will directly affect their experiences with contraceptives. In Figure 1, these factors work interactively with partner and relationship factors, all of which are nested within the broader cultural and structural context.