Abstract

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is a cytoprotective enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of heme to biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and iron. The beneficial effects of HO-1 expression are not merely due to degradation of the pro-oxidant heme but are also credited to the by-products that have potent, protective effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prosurvival properties. This is well reflected in the preclinical animal models of injury in both renal and nonrenal settings. However, excessive accumulation of the by-products can be deleterious and lead to mitochondrial toxicity and oxidative stress. Therefore, use of the HO system in alleviating injury merits a targeted approach. Based on the higher susceptibility of the proximal tubule segment of the nephron to injury, we generated transgenic mice using cre-lox technology to enable manipulation of HO-1 (deletion or overexpression) in a cell-specific manner. We demonstrate the validity and feasibility of these mice by breeding them with proximal tubule-specific Cre transgenic mice. Similar to previous reports using chemical modulators and global transgenic mice, we demonstrate that whereas deletion of HO-1, specifically in the proximal tubules, aggravates structural and functional damage during cisplatin nephrotoxicity, selective overexpression of HO-1 in proximal tubules is protective. At the cellular level, cleaved caspase-3 expression, a marker of apoptosis, and p38 signaling were modulated by HO-1. Use of these transgenic mice will aid in the evaluation of the effects of cell-specific HO-1 expression in response to injury and assist in the generation of targeted approaches that will enhance recovery with reduced, unwarranted adverse effects.

Keywords: cisplatin, acute kidney injury, heme oxygenase-1, p38

a microsomal enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), catalyzes the breakdown of heme, releasing iron, carbon monoxide (CO), and biliverdin; then, biliverdin is converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase. HO primarily exists as two isoforms. HO-1, the inducible isoform, is encoded on chromosome 22 in the human genome (chromosome 8 in the mouse) and translates to a 32-kDa protein. HO-2 is the constitutive isoform encoded on chromosome 16 in both mouse and human genomes and translates to a 36-kDa protein. Since the first description of HO as a heme-degrading enzyme by Schmid and colleagues in 1968 (58), interest in this enzymatic system has led to the identification of multiple cytoprotective processes that are regulated by HO activity or the resultant by-products of the reaction (CO, iron-induced ferritin, biliverdin, and bilirubin) (15, 16, 26).

Genetic and pharmacological manipulation of HO-1 in animal models of acute kidney injury (AKI) and disease alters the extent of injury. Whereas global deficiency or inhibition worsens renal structure and function, increased expression is protective. For instance, nephroprotection by global HO-1 induction using chemical inducers and transgenic mice that overexpress HO-1 has been demonstrated in ischemia-reperfusion injury, nephrotoxin-induced renal injury, acute glomerulonephritis, obstructive nephropathy, and rhabdomyolysis (3, 7, 24, 25, 36, 37, 51, 53, 59, 62). However, it should be noted that in vitro and ex vivo studies have demonstrated deleterious effects of generalized HO-1 overexpression, which may be attributed to an increase in iron release (9, 56, 67). Furthermore, there have been several inconsistent reports on the cytoprotective role of HO-1 following AKI. Prior upregulation of HO-1 or inhibition of HO activity has resulted in contrasting outcomes, with worse, no apparent effect, or a reduction in severity of AKI (2, 19, 22, 35, 66). However, these studies used chemical modulators that have potential nonspecific effects, including immunostimulatory effects, altering the activity of nitric oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase and altering the expression of adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1 (18, 29, 30, 40, 64). Therefore, the use of such modulators has confounded the evaluation of the role of HO-1 in injury. Recent studies, using genetically deficient HO-1 (HO-1−/−) mice, demonstrated a protective role of HO-1 in several models of AKI, including glycerol-induced rhabdomyolysis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and cisplatin nephrotoxicity (38, 45, 53). The use of global HO-1−/− mice is associated with several limitations. For instance, with increasing age, these mice exhibit microcytic hypochromic anemia, hematuria, proteinuria, and kidney and liver iron accumulation, along with a chronic inflammatory phenotype consisting of hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hepatic periportal inflammation, leukocytosis, and glomerulonephritis (46). In addition, the HO-1−/− mice display increased levels of lipid peroxidation, oxidized proteins, and iron deposition in the kidneys. Furthermore, cultured fibroblasts from the HO-1−/− mice are highly susceptible to heme- or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-mediated oxidative insults (47).

It is interesting to note that induction of HO-1 occurs in specific segments of the nephron in different models of AKI, presumably in the proximity of the insult. Whereas cisplatin maximally accumulates and injures the S3 segment of the proximal tubule, rhabdomyolysis mainly affects the S2 segment (8, 10, 50, 65). Intriguingly, HO-1 is predominantly induced in these segments following injury (3, 38). In complex injury settings, such as ischemia reperfusion, HO-1 is induced in both the renal (e.g., tubular epithelium) and nonrenal (inflammatory cells) compartments (3, 12, 13, 61). This site-specific localization of HO-1 expression is corroborated further in humans, validating the findings in the animal models (32, 39, 52). In such conditions, it would be interesting to determine the role of HO-1 in each cell type during injury and the consequential effects of such expression in the fate of tissue/organ recovery. Therefore, it is essential to target HO-1 upregulation to the injured tissue to minimize potential unwarranted, off-target effects. The purpose of this work was to generate and characterize unique transgenic mice that would enable manipulation of HO-1 expression (overexpression or deletion) in a cell-specific manner and investigate the effects of such targeted expression during injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Approval

All procedures involving mice were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines regarding the care and use of live animals and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UAB.

Animals

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) Cre transgenic mice that express cre recombinase, primarily in the proximal tubules of the kidney, were provided by Dr. Volker Haase (49). HO-1-floxed mice, used to generate proximal tubule-specific HO-1 deletion (HO-1PT−/−) mice, were obtained from the Alexander Fleming Biomedical Sciences Research Center (Athens, Greece) and have been described previously (60).

ROSA-HO-1 mice were generated using the ROSA26 targeting vector and gateway cloning, as described previously (41). To generate the ROSA-HO-1 targeting construct, a cassette containing a stop codon, followed by human HO-1 cDNA that was flanked by attB sites, was cloned into the ROSA26 targeting vector (pRosa26DEST; #21189; Addgene, Cambridge, MA) using Gateway cloning technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). This construct was electroporated into Primogenix B6 (C57BL/6 N-tac; Primogenix, Laurie, MO) embryonic stem (ES) cells, screened by PCR, and correctly targeted ES cells were injected into blastocysts to generate male chimeras, as described previously (41). Germline passage was obtained by crossing chimeric males to albino C57BL/6 females. Primers used to genotype the wild-type (WT) and floxed allele include the following: ROSA forward (fwd): 5′-ctcgtgatctgcaactccag-3′; ROSA WT reverse (rev): 5′-gaaatctccgaggcggataca-3′; ROSA flox rev: 5′-agaccgcgaagagtttgtcc-3′. The ROSA-floxed mice (referred to as HO-1+/+) were bred with PEPCK Cre transgenic mice to generate proximal tubule-specific, HO-1-overexpressing mice (ROSA-HO-1).

The ROSA-flox mice used to generate the HO-1-overexpressing mice were on a pure C57BL/6 background. The PEPCK Cre mice were on a mixed background (ES cells from 129/Ola mice were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts) and bred back on a C57BL/6 background for >10 generations. The conditional HO-1−/− flox mice were on a mixed background (ES cells from 129/3 mice were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts) and bred back on a C57BL/6 background for >10 generations. Therefore, all of the transgenic mice used in this study were predominantly on a C57BL/6 background. Adult male mice (8 wk of age) were provided acidified water (0.3 M ammonium chloride) for 1 wk to enhance PEPCK promoter activity in the kidney, as described previously (68).

Quantification of mRNA Expression

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and SYBR Green-based real-time PCR was performed on the cDNA product generated from total RNA (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Relative mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative threshold cycle method and normalized to GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. Primers used to detect the specific genes included the following: human HO-1 fwd: 5′-catgacaccaaggaccagag-3′, human HO-1 rev: 5′-agtgtaaggacccatcggag-3′, mouse HO-1 fwd: 5′-ggtgatggcttccttgtacc-3′, mouse HO-1 rev: 5′-agtgaggcccataccagaag, GAPDH fwd: 5′-atcatccctgcatccact-3′, GAPDH rev: 5′-atccacgacggacacatt-3′. All of the reactions were performed in triplicate, and specificity was monitored using melting curve analysis.

Animal Models of AKI

Cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

Cisplatin injury was induced in age-matched mice (10–14 wk of age), as described previously (68). Briefly, mice were administered 20 mg/kg body wt cisplatin (1.0 mg/ml solution in sterile normal saline) or vehicle (normal saline) by a single intraperitoneal injection. All animals were euthanized at day 3 or 5 following cisplatin administration, and kidneys were harvested for staining or protein analysis. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture, and serum creatinine levels were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham–University of California, San Diego (UAB-UCSD), O'Brien Center for Acute Kidney Injury Research bioanalytical core facility (57).

Ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury was performed as described previously (20). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and following incision, both renal pedicles were cross clamped for 25 min using an atraumatic vascular clamp (catalog #18055-05; Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA). Immediate blanching of the kidney confirmed ischemic induction. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C during surgery and ischemia time. Kidneys were inspected for color change within 1 min of clamp removal to ensure uniform reperfusion. Kidneys were harvested after 24 h for immunohistochemical staining.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with periodic acid-Schiff reagent. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (68). Briefly, paraffin-embedded, 5 μm kidney sections were deparaffinized in xylenes and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed in Trilogy (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) at 95°C for 30 min, followed by peroxidase block in 3% H2O2. Sections were blocked in blocking buffer containing 1% BSA, 0.2% nonfat dry milk (NFDM), and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 1 h and incubated overnight in HO-1 antibody (1:200; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). Sections were washed with PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were washed with PBST and developed using chromogen substrate, per the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were washed in distilled water, dehydrated, and mounted using xylene mounting media (Protocol, Kalamazoo, MI).

To identify proximal tubules, lotus lectin staining was performed as described previously (68). Briefly, avidin/biotin blocking was performed using the avidin/biotin blocking kit, per the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories). Biotinylated lotus lectin was diluted in PBS (1:400) and added for 1 h. Sections were washed three times in PBS and then incubated in avidin/biotin complex (ABC) Reagent, Ready-to-Use (R.T.U.; Vector Laboratories), for 30 min and washed again. Chromagen substrate was diluted, per the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories), and sections were washed, dehydrated, and mounted as above. Images were captured using a Leica DM I600B microscope and Leica Application Suite V4.2 (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Western Blot Analysis

Tissues were homogenized and lysed for proteins, as described previously (5). Briefly, harvested tissues were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mmol/l Tris/HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l EGTA, 1 mmol/l sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mmol/l sodium fluoride) with protease (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and phosphatase (Biotool.com, Houston, TX) inhibitors and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total protein (75 μg) was resolved on a 12% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% NFDM in PBST for 1 h and then incubated with a rabbit anti-HO-1 antibody (1:5,000; Enzo Life Sciences), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-HO-2 antibody (1:2,000; Enzo Life Sciences), rabbit anti-organic cation transporter 1 (anti-OCT1; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), goat anti-OCT2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse phospho-p38 (1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology), followed by a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat or goat anti-rabbit (or mouse) IgG antibody (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). For total p38 detection, the membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in PBST for 1 h and then incubated with total p38 antibody (1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology), followed by a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Horseradish peroxidase activity was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare, Atlanta, GA). The membrane was stripped and probed with anti-GAPDH antibody (1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich) to confirm loading and transfer. Densitometry analysis was performed, and results were normalized to GAPDH (or total p38) expression.

HO Enzyme Activity Measurement

HO activity was measured by bilirubin generation, as described previously (2). Briefly, tissues were homogenized in buffer (200 mM KH2PO4, 135 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and centrifuged (10,000 g, 4°C, 20 min). The microsomal fraction from the supernatant was achieved by ultracentrifugation (100,000 g, 4°C, 60 min; Beckman L7-35 ultracentrifuge, 70 Ti rotor; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The microsomal pellet was then incubated with rat liver cytosol (3 mg; source of biliverdin reductase), hemin (20 μM), glucose-6-phosphate (2 mM), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (0.2 μ), and NADPH (0.8 mM) for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. The bilirubin formed was extracted with chloroform, difference in optical density 464–530 nm measured, and enzyme activity calculated as picomoles bilirubin formed per 60 min/mg protein.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SE. The unpaired Student's t-test was used for comparisons between two groups. For comparisons that involved more than two groups, ANOVA and the Student-Newman-Keuls test were used for analysis. All results were considered significant at P < 0.05. All of the experiments were performed at least three times.

RESULTS

Generation and Characterization of Targeted HO-1-Overexpressing Mice

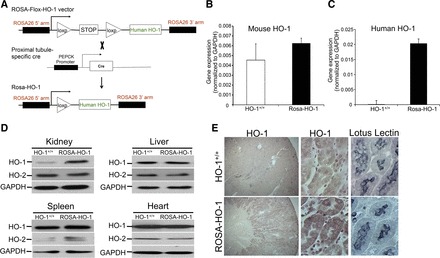

To achieve targeted HO-1 overexpression, we first generated a ROSA-HO-1 targeting construct, as described in materials and methods. Briefly, human HO-1 cDNA, downstream of a floxed stop codon, was cloned into the ROSA26 targeting vector (Fig. 1A). Homologous recombination of this vector with the endogenous ROSA26 locus in ES cells resulted in the generation of ROSA-flox-HO-1 mice (referred to as WT mice; HO-1+/+). These mice were bred with proximal tubule-specific Cre recombinase mice (PEPCK Cre) to delete the floxed stop codon and thereby overexpress HO-1. The resultant double-transgenic mice with targeted HO-1 overexpression are referred to as ROSA-HO-1 mice (Fig. 1A). No differences in terms of growth, development, and survival were noted between the ROSA-HO-1 and HO-1+/+ mice (data not shown). As the cloned HO-1 was of human origin, we next evaluated the renal expression of mouse and human HO-1 mRNA. Whereas there was no significant difference in the levels of endogenous mouse HO-1 expression (Fig. 1B), human HO-1 was only expressed in the ROSA-HO-1 kidneys (Fig. 1C). We further verified this increase in HO-1 mRNA expression at the protein level of ROSA-HO-1 kidneys compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 1D). In addition, there was no difference in HO-1 protein expression in the heart, liver, and spleen of ROSA-HO-1 mice compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 1D). HO-2 levels in the ROSA-HO-1 mice were similar to HO-1+/+ mice. Furthermore, we found that the ROSA-HO-1 kidneys had increased HO enzyme activity compared with HO-1+/+ kidneys (126.5 ± 24 vs. 70.7 ± 12.3 pmol bilirubin formed·mg protein−1·h−1), confirming that the cloned human HO-1 was functionally active. Immunohistochemistry revealed that HO-1 was overexpressed specifically in the renal proximal tubules, which was confirmed by colocalization with lotus lectin (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of proximal tubule-specific heme oxygenase-1-overexpressing mice (ROSA-HO-1). A: schematic of the floxed and ROSA-HO-1 alleles. Before cre-mediated deletion (ROSA-Flox-HO-1; HO-1+/+), the expression of the human HO-1 gene is prevented by the stop codon cassette flanked by LoxP sites (triangles). After cre-mediated recombination (ROSA-HO-1) at the LoxP sites, the stop codon is deleted, allowing the expression of HO-1. Total RNA was isolated from the kidneys of HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice and analyzed for the expression of mouse (B) and human (C) HO-1. Data are expressed following normalization with GAPDH. D: HO-1 and HO-2 expression in the indicated tissues was determined by Western analysis. Anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. E: localization of HO-1 protein was determined by staining with lotus lectin (proximal tubule marker) and HO-1 on serial sections of kidneys from HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice under basal conditions. PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

Overexpression of HO-1 in the Proximal Tubules of the Kidney Protects against Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity

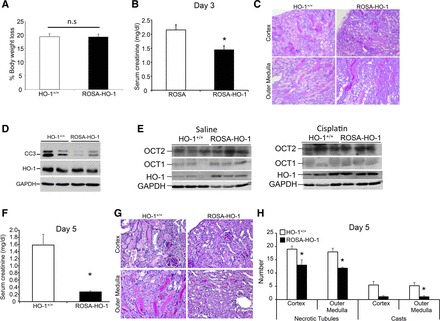

It has been demonstrated previously that HO-1 is induced in the proximal tubules of the kidney during cisplatin nephrotoxicity and is protective (2, 53). Furthermore, global overexpression of HO-1 was protective in rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI (24). However, the exact location where HO-1 must be expressed to mediate maximal beneficial effects during AKI is unknown. Therefore, we chose to evaluate whether proximal tubule-specific HO-1 overexpression will protect against cisplatin-induced AKI. Whereas loss of body weight following cisplatin administration was not different between the two transgenic mice groups (Fig. 2A), ROSA-HO-1 mice had significantly preserved kidney function, as measured by serum creatinine (Fig. 2B). Concurrently, ROSA-HO-1 mice had better preserved kidney architecture with fewer casts, but there was no difference in the number of necrotic tubules compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 2C). We demonstrate that at the cellular level, ROSA-HO-1 kidneys expressed lower levels of cleaved caspase-3 compared with cisplatin-treated HO-1+/+ kidneys, indicating a lower degree of apoptosis in the presence of increased proximal tubule-specific HO-1 expression (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, whereas the expression of OCT1 was not different, OCT2 expression was significantly higher in the ROSA-HO-1 mice in the basal state (Fig. 2E). However, following cisplatin administration, there was no difference in the expression of these transporters between the two groups (Fig. 2E). Analysis of kidney function and architecture at 5 days following cisplatin administration also revealed significant protection in the ROSA-HO-1 mice compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 2, F–H).

Fig. 2.

Proximal tubule-specific HO-1 overexpression protects against cisplatin nephrotoxicity. A: body weight loss following cisplatin administration (20 mg/kg body wt; intraperitoneal single dose) is expressed as a percentage of the original weight. Data are expressed as means ± SE. B: serum creatinine levels were measured and expressed as milligrams/deciliter day 3 after cisplatin administration. Data are expressed as means ± SE; *P < 0.05. C: representative periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of kidney sections from HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice at day 3 following cisplatin administration. D: whole-kidney protein lysates from HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice were analyzed for the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) and HO-1. Anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. E: whole-kidney protein lysates from saline- and cisplatin-administered HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice were analyzed for the expression of organic cation transporters 1 and 2 (OCT1 and -2) and HO-1. Anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. F: serum creatinine levels were measured and expressed as milligrams/deciliter at day 5 after cisplatin administration. Data are expressed as means ± SE; *P < 0.05. G: representative PAS of kidney sections from HO-1+/+ and ROSA-HO-1 mice at day 3 following cisplatin administration. H: scoring of structural damage was performed by counting the number of casts and necrotic tubules in the cortex and outer medulla. Data are represented as means ± SE; *P < 0.05.

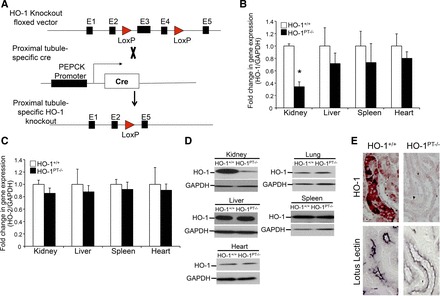

Generation and Characterization of HO-1PT−/− Mice

The floxed HO-1 (referred to as HO-1+/+) mice were generated by flanking exons 3 and 4 with LoxP sites, as described previously (60). The breeding of these floxed HO-1 mice with PEPCK Cre mice led to the generation of HO-1PT−/− mice, which do not express HO-1 only in the proximal tubules of the kidney (Fig. 3A). HO-1 expression was significantly lower only in the kidneys of HO-1PT−/− mice compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 3B). It should be noted that the PEPCK promoter is also active in ∼20% of hepatocytes. However, we did not see a significant difference in HO-1 expression in the livers of HO-1PT−/− mice compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 3B). No change in HO-2 expression was observed in the kidney, liver, heart, and spleen between HO-1PT−/− and HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 3C). In addition, deletion of HO-1 only in the kidneys of HO-1PT−/− mice was confirmed further at the protein level (Fig. 3D). Immunohistochemical staining revealed lack of HO-1 expression in the renal proximal tubules of HO-1PT−/− mice, as verified by HO-1 and lotus lectin staining (Fig. 3E). Since HO-1 expression in the uninjured kidney is barely detectable, we induced HO-1 by renal ischemia reperfusion to demonstrate the absence of HO-1 in the proximal tubules of HO-1PT−/− mice.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of proximal tubule-specific HO-1 deletion mice (HO-1PT−/−). A: schematic of the floxed vector, PEPCK Cre, and HO-1PT−/− alleles. Following PEPCK Cre-mediated recombination, exons 3 and 4 (E3 and E4) are deleted, leading to loss of HO-1 expression in the proximal tubules. Total RNA was isolated from the indicated organs of HO-1+/+ and HO-1PT−/− mice and analyzed for the expression of HO-1 (B) and HO-2 (C). Data are normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change compared with HO-1+/+ mice; *P < 0.05. D: protein lysates from the indicated organs were analyzed for HO-1 expression by Western analysis. Anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. E: deletion of HO-1 specifically in the proximal tubules of HO-1PT−/− mice was confirmed by staining with lotus lectin (proximal tubule marker) and HO-1 on serial sections of kidneys from HO-1+/+ and HO-1PT−/− mice following 24 h of renal ischemia reperfusion.

HO-1PT−/− Exacerbates Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity

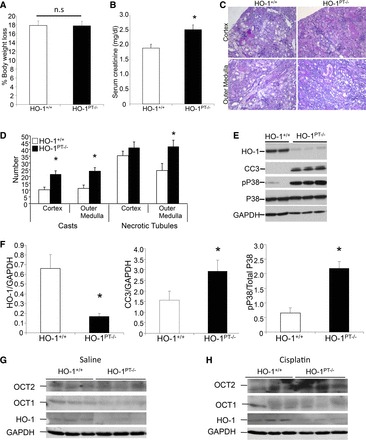

We have demonstrated previously that global HO-1−/− leads to heightened renal injury and apoptosis following cisplatin administration (5, 53). We have also demonstrated that global overexpression of HO-1 protects against injury (24). We next sought to determine the effects of targeted HO-1 deletion on the progression of injury. At 3 days after cisplatin administration, whereas there was no difference in percent loss of body weight (Fig. 4A), HO-1PT−/− mice had significantly higher serum creatinine levels compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 4B). Additionally, HO-1PT−/− mice exhibited worse structural architecture, with a substantial number of casts and necrotic tubules compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 4, C and D). Western blot analysis revealed higher cleaved caspase-3 expression in HO-1PT−/− kidneys compared with cisplatin-treated HO-1+/+ mice (Fig. 4, E and F). Interestingly, we also found enhanced expression of phospho-p38 in the cisplatin-treated HO-1PT−/− kidneys compared with HO-1+/+ kidneys (Fig. 4, E and F). Furthermore, expression of OCT1 and OCT2 was not different between the groups in the basal state and following cisplatin administration (Fig. 4, G and H).

Fig. 4.

HO-1PT−/− exacerbates cisplatin nephrotoxicity. A: loss of body weight following cisplatin administration was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the original weight. Data are expressed as means ± SE. B: serum creatinine levels were measured and expressed as milligrams/deciliter at day 3 after cisplatin administration. Data are expressed as means ± SE; *P < 0.05. C: representative PAS-stained sections of the cortex and outer medulla from HO-1+/+ and HO-1PT−/− mice at day 3 following cisplatin administration. D: scoring of structural damage was performed by counting the number of casts and necrotic tubules in the cortex and outer medulla. Data are represented as means ± SE; *P < 0.05. E: whole-kidney lysates of cisplatin-administered HO-1+/+ and HO-1PT−/− mice were analyzed for the expression of HO-1, phospho-p38 (pP38), p38, and CC3 by Western analysis. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for GAPDH to demonstrate equal loading. F: densitometric analysis of HO-1 and CC3 was performed and normalized to GAPDH expression. Phospho-p38 expression was normalized to total p38 expression. Data are represented as means ± SE; *P < 0.05. G and H: whole-kidney protein lysates from saline- and cisplatin-administered HO-1+/+ and HO-1PT−/− mice were analyzed for the expression of OCT1 and -2 and HO-1. Anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In the past few decades, research has identified a protective role for HO-1 in several pathophysiological conditions, including AKI (2, 3, 24, 25, 36, 37, 51, 53, 59). There is also compelling evidence to suggest that the by-products of the HO-1-catalyzed reaction provide additional protective effects and facilitate recovery (15, 26, 33, 35). These advantageous functions of HO-1 have sparked great interest among researchers to identify techniques to augment HO-1 expression to minimize injury and accelerate repair and recovery. In fact, heme derivatives or products of the HO-1 enzymatic reaction (e.g., CO) have been the subject of several clinical trials (NCT01430156, NCT00483587, NCT00531856, NCT00122694, and NCT00094406; ClinicalTrials.gov). However, the excessive use of each of these intermediates can lead to deleterious effects. For instance, whereas low levels of CO are protective in preclinical animal models of injury, the toxic effect of this gas on mitochondria and competition with oxygen for hemoglobin are major limitations (33). In addition, adenoviral-mediated overexpression of HO-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells led to apoptosis (27). These limitations underscore the need for the development of targeted approaches that would upregulate HO-1 in a cell-specific manner. Toward this effort, we generated two transgenic lines that enable manipulation of HO-1 expression (overexpression or deletion) in an important and accordingly vulnerable portion of the nephron, namely the proximal tubule.

With the use of cisplatin nephrotoxicity as a model of AKI, we determined the functional validity and feasibility of these transgenic mice. Cisplatin is a commonly used chemotherapeutic agent that is effective against a wide variety of solid tumors. However, nearly 30% of patients that receive cisplatin are prone to developing AKI (11, 23). Several studies have proposed oxidative stress as a major determinant of the pathophysiology during cisplatin injury, and in corroboration, induction of antioxidants, such as HO-1, or supplementation with N-acetyl cysteine before cisplatin administration has led to a favorable response (1, 2, 4, 11, 23). We chose to address the effects of HO-1 expression in cisplatin nephrotoxicity for two reasons. First, we (5, 24, 53) and others (4, 21, 43) have demonstrated previously that whereas global HO-1−/− (or inhibition of HO activity) leads to worse renal injury, HO-1 upregulation significantly mitigates cisplatin-induced injury. Second, OCTs that mediate cisplatin uptake are preferentially expressed in proximal tubules (31, 44), allowing us to determine the effects of targeted HO-1 expression. In this connection, we chose to breed the floxed transgenic mice with proximal tubule-specific Cre recombinase mice (PEPCK Cre). The resultant double-transgenic mice overexpressed (or lacked expression of) HO-1, specifically in proximal tubules. Of note, PEPCK Cre mice express the cre gene under the regulation of a mutated PEPCK promoter (P3 region) and therefore, express cre recombinase only in the proximal tubules (all S3 and most S1 and S2 segments) and ∼20% of hepatocytes (49). In addition, differences exist between males and females as to the penetrance of the expression of the PEPCK Cre transgene by virtue of its expression on the X chromosome (49). Thus males exhibit greater penetrance than females as a result of the random generation of the Barr body. This caveat restricted our studies to be performed only in male animals.

Previous studies have generated transgenic mice that overexpress HO-1 in certain organs using specific promoters to drive the expression of HO-1 cDNA. These promoters include keratin (skin), alpha-myosin heavy chain (heart), glial fibrillary acidic protein (astrocyte), and uromodulin (thick ascending limb) (6, 17, 55, 63). However, we chose to generate a floxed mouse that would permit inducibility of HO-1 overexpression in any cell type desired. Therefore, we generated floxed mice that harbor the human HO-1 cDNA under the regulation of the ROSA26 locus. These mice do not express the human HO-1 gene, due to the presence of the stop codon preceding it. However, cre recombinase deletes the stop codon and enables overexpression of HO-1 cDNA. This allows manipulation of HO-1 gene expression using site-specific Cre recombinase transgenic mice. With the use of PEPCK Cre mice, we demonstrated the integrity and feasibility of this construct. ROSA-HO-1 mice expressed the human HO-1 gene only in the kidney, and this overexpression was verified at the gene and protein levels. In addition, there was no difference in HO-1 expression in any of the other organs tested (lung, heart, liver, spleen) between the WT and ROSA-HO-1 mice. HO-1 overexpression in the ROSA-HO-1 was also confined to renal proximal tubules. Furthermore, although not statistically significant, HO activity was higher in the kidneys of ROSA-HO-1 mice compared with WT mice. It should be noted here that whole-kidney microsomes were used to determine HO enzyme activity, which likely resulted in the dilution of the effect of proximal tubule HO-1 overexpression.

Having characterized the ROSA-HO-1 mice, we validate previous findings and demonstrate that proximal tubule-specific overexpression of HO-1 is protective against cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Interestingly, whereas kidney function was preserved in the ROSA-HO-1 mice, there was no significant difference in the structural damage at 3 days following cisplatin administration, as evidenced by the presence of necrotic tubules. This may be due to several reasons. First, the level of HO-1 overexpression in the ROSA-HO-1 mice was perhaps insufficient to provide maximal beneficial effects. Second, this study was terminated at day 3 following cisplatin administration. At such an early phase, it is possible that the accumulated cisplatin leads to increased necrosis in the proximal and distal tubules. However, it should be noted that cleaved caspase-3 expression was lower in the ROSA-HO-1 mice, suggesting reduced apoptosis. Third, whereas our focus was mainly on the proximal, tubule-specific HO-1 expression, it is plausible that other cells are also involved in mediating injury. For instance, recent studies demonstrate increased inflammatory influx, specifically macrophages, following cisplatin administration (28). In this context, we recently demonstrated that myeloid-specific HO-1 expression is imperative for recovery from ischemia-reperfusion-mediated AKI (20). Despite this structural damage, we found that ROSA-HO-1 mice had decreased apoptosis and preserved renal function. To delineate these effects further, we analyzed kidney function and structure at 5 days postcisplatin administration. Interestingly, we found that ROSA-HO-1 mice had significantly preserved kidney function and architecture at this later time point. These results suggest that whereas the initial insult to the kidney structure is similar between the groups, HO-1-overexpressing mice demonstrate accelerated recovery. Future studies will need to extend the time frame of these experiments to determine recovery from injury and evaluate the beneficial role of HO-1 expression in other cells (such as inflammatory cells) during cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

Our data also demonstrate that there was a significant increase in the expression of OCT2 in the kidneys of HO-1-overexpressing mice compared with the WT control mice in the basal state. This would suggest that potentially, there might be an increase in the uptake of cisplatin in the HO-1-overexpressing mice. Despite this increase in OCT2 expression, we found that the HO-1-overexpressing mice had significant protection against cisplatin injury. Whereas further studies are required to determine the contributory role for HO-1 in modulating the expression of OCT2, we found that there was no difference in OCT2 expression following cisplatin administration in these mice. In addition, there was no difference in the expression of this transporter in the conditional HO-1−/− mice following saline or cisplatin administration. These results suggest that modulation of injury by HO-1 expression is independent of OCT1 and OCT2 transporter expression.

Our findings also highlight increased p38 signaling following cisplatin administration in the HO-1PT−/− mice. Whereas our studies did not delineate whether p38 activation acts as a compensatory defense mechanism against cisplatin injury in the absence of HO-1, p38 inhibition has been reported to mitigate cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice (14, 48). In addition, previous studies have shown that p38 signaling regulates HO-1 gene expression (34, 42, 54). Given these findings, it would be interesting to determine if HO-1 regulates p38 signaling during injury. Future studies that aim at delineating the complex signaling pathways modulated during cisplatin injury and the role of HO-1 in these processes are warranted.

In summary, we have generated and characterized transgenic mice that enable overexpression (or deletion) of HO-1 in any cell type using cell-specific Cre recombinase transgenic mice. Whereas we targeted the renal proximal tubule in this work, these mice could be a valuable tool for the generation of cell/time-specific HO-1 expression in other organ systems as well. These transgenic mice will therefore assist in the determination of cells/tissue that are most susceptible to a pathophysiologic insult and also aid in the identification of effector cells that ultimately mediate repair and recovery from injury. These transgenic mice will also be valuable in the development of targeted HO-1-based therapeutic approaches that enhance tissue repair while limiting unwarranted effects to bystander cells.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01 DK59600 (to A. Agarwal), P30 DK079337 (core resource of the UAB-UCSD O'Brien Center; to A. Agarwal), and K01 DK103931 (to S. Bolisetty) and Department of Veterans Affairs Grant IP1-BX001595 (to A. Agarwal).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.B. and A.A. conception and design of research; S.B., A.T., R.J., and A.Z. performed experiments; S.B., A.T., R.J., and A.Z. analyzed data; S.B., A.Z., and A.A. interpreted results of experiments; S.B. and A.T. prepared figures; S.B. drafted manuscript; S.B., A.T., A.Z, and A.A. edited and revised manuscript; S.B. and A.A. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Volker Haase and George Kollias for the PEPCK Cre mice and conditional floxed HO-1 deletion mice, respectively, and Carnellia Lee and Daniel McFalls for their technical assistance. The authors also acknowledge the UAB Transgenic Animal/Embryonic Stem Cell Facility and Drs. Peter Hohenstein and Bradley Yoder for assistance with generating the ROSA-HO-1 mouse.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelrahman AM, Al Salam S, AlMahruqi AS, Al husseni IS, Mansour MA, Ali BH. N-Acetylcysteine improves renal hemodynamics in rats with cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. J Appl Toxicol 30: 15–21, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal A, Balla J, Alam J, Croatt AJ, Nath KA. Induction of heme oxygenase in toxic renal injury: a protective role in cisplatin nephrotoxicity in the rat. Kidney Int 48: 1298–1307, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal A, Nick HS. Renal response to tissue injury: lessons from heme oxygenase-1 GeneAblation and expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 965–973, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Kahtani MA, Abdel-Moneim AM, Elmenshawy OM, El-Kersh MA. Hemin attenuates cisplatin-induced acute renal injury in male rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014: 476430, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolisetty S, Traylor AM, Kim J, Joseph R, Ricart K, Landar A, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits renal tubular macroautophagy in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1702–1712, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen-Roetling J, Song W, Schipper HM, Regan CS, Regan RF. Astrocyte overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 improves outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 46: 1093–1098, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correa-Costa M, Amano MT, Camara NO. Cytoprotection behind heme oxygenase-1 in renal diseases. World J Nephrol 1: 4–11, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cristofori P, Zanetti E, Fregona D, Piaia A, Trevisan A. Renal proximal tubule segment-specific nephrotoxicity: an overview on biomarkers and histopathology. Toxicol Pathol 35: 270–275, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennery PA, Sridhar KJ, Lee CS, Wong HE, Shokoohi V, Rodgers PA, Spitz DR. Heme oxygenase-mediated resistance to oxygen toxicity in hamster fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 272: 14937–14942, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobyan DC, Levi J, Jacobs C, Kosek J, Weiner MW. Mechanism of cis-platinum nephrotoxicity: II. Morphologic observations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 213: 551–556, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dos Santos NA, Carvalho Rodrigues MA, Martins NM, dos Santos AC. Cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and targets of nephroprotection: an update. Arch Toxicol 86: 1233–1250, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferenbach DA, Nkejabega NC, McKay J, Choudhary AK, Vernon MA, Beesley MF, Clay S, Conway BC, Marson LP, Kluth DC, Hughes J. The induction of macrophage hemeoxygenase-1 is protective during acute kidney injury in aging mice. Kidney Int 79: 966–976, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferenbach DA, Ramdas V, Spencer N, Marson L, Anegon I, Hughes J, Kluth DC. Macrophages expressing heme oxygenase-1 improve renal function in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Mol Ther 18: 1706–1713, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francescato HD, Costa RS, da Silva CG, Coimbra TM. Treatment with a p38 MAPK inhibitor attenuates cisplatin nephrotoxicity starting after the beginning of renal damage. Life Sci 84: 590–597, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Soares MP. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50: 323–354, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grochot-Przeczek A, Dulak J, Jozkowicz A. Haem oxygenase-1: non-canonical roles in physiology and pathology. Clin Sci (Lond) 122: 93–103, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grochot-Przeczek A, Lach R, Mis J, Skrzypek K, Gozdecka M, Sroczynska P, Dubiel M, Rutkowski A, Kozakowska M, Zagorska A, Walczynski J, Was H, Kotlinowski J, Drukala J, Kurowski K, Kieda C, Herault Y, Dulak J, Jozkowicz A. Heme oxygenase-1 accelerates cutaneous wound healing in mice. PLoS One 4: e5803, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundemar L, Ny L. Pitfalls using metalloporphyrins in carbon monoxide research. Trends Pharmacol Sci 18: 193–195, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill-Kapturczak N, Agarwal A. Haem oxygenase-1—a culprit in vascular and renal damage? Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1495–1499, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hull TD, Kamal AI, Boddu R, Bolisetty S, Guo L, Tisher CC, Rangarajan S, Chen B, Curtis LM, George JF, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates myeloid cell trafficking in AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2139–2151, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung SH, Kim HJ, Oh GS, Shen A, Lee S, Choe SK, Park R, So HS. Capsaicin ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal injury through induction of heme oxygenase-1. Mol Cells 37: 234–240, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaizu T, Tamaki T, Tanaka M, Uchida Y, Tsuchihashi S, Kawamura A, Kakita A. Preconditioning with tin-protoporphyrin IX attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat kidney. Kidney Int 63: 1393–1403, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasawa T, Steyger PS. An integrated view of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Toxicol Lett 237: 219–227, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Zarjou A, Traylor AM, Bolisetty S, Jaimes EA, Hull TD, George JF, Mikhail FM, Agarwal A. In vivo regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in humanized transgenic mice. Kidney Int 82: 278–291, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Yang JI, Jung MH, Hwa JS, Kang KR, Park DJ, Roh GS, Cho GJ, Choi WS, Chang SH. Heme oxygenase-1 protects rat kidney from ureteral obstruction via an antiapoptotic pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1373–1381, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkby KA, Adin CA. Products of heme oxygenase and their potential therapeutic applications. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F563–F571, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XM, Chapman GB, Wang H, Durante W. Adenovirus-mediated heme oxygenase-1 gene expression stimulates apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation 105: 79–84, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu LH, Oh DJ, Dursun B, He Z, Hoke TS, Faubel S, Edelstein CL. Increased macrophage infiltration and fractalkine expression in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324: 111–117, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo D, Vincent SR. Metalloporphyrins inhibit nitric oxide-dependent cGMP formation in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 267: 263–267, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meffert MK, Haley JE, Schuman EM, Schulman H, Madison DV. Inhibition of hippocampal heme oxygenase, nitric oxide synthase, and long-term potentiation by metalloporphyrins. Neuron 13: 1225–1233, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2: 2490–2518, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morimoto K, Ohta K, Yachie A, Yang Y, Shimizu M, Goto C, Toma T, Kasahara Y, Yokoyama H, Miyata T, Seki H, Koizumi S. Cytoprotective role of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 in human kidney with various renal diseases. Kidney Int 60: 1858–1866, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motterlini R, Otterbein LE. The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9: 728–743, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naidu S, Vijayan V, Santoso S, Kietzmann T, Immenschuh S. Inhibition and genetic deficiency of p38 MAPK up-regulates heme oxygenase-1 gene expression via Nrf2. J Immunol 182: 7048–7057, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nath KA. Heme oxygenase-1: a provenance for cytoprotective pathways in the kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int 70: 432–443, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nath KA. Heme oxygenase-1 and acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 23: 17–24, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GM, Balla J, Jacob HS, Levitt MD, Rosenberg ME. Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest 90: 267–270, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nath KA, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Grande JP, Poss KD, Alam J. The indispensability of heme oxygenase-1 in protecting against acute heme protein-induced toxicity in vivo. Am J Pathol 156: 1527–1535, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nath KA, Vercellotti GM, Grande JP, Miyoshi H, Paya CV, Manivel JC, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Payne WD, Alam J. Heme protein-induced chronic renal inflammation: suppressive effect of induced heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int 59: 106–117, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Novogrodsky A, Suthanthiran M, Stenzel KH. Immune stimulatory properties of metalloporphyrins. J Immunol 143: 3981–3987, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor AK, Malarkey EB, Berbari NF, Croyle MJ, Haycraft CJ, Bell PD, Hohenstein P, Kesterson RA, Yoder BK. An inducible CiliaGFP mouse model for in vivo visualization and analysis of cilia in live tissue. Cilia 2: 8, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paine A, Eiz-Vesper B, Blasczyk R, Immenschuh S. Signaling to heme oxygenase-1 and its anti-inflammatory therapeutic potential. Biochem Pharmacol 80: 1895–1903, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan H, Shen K, Wang X, Meng H, Wang C, Jin B. Protective effect of metalloporphyrins against cisplatin-induced kidney injury in mice. PLoS One 9: e86057, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peres LA, da Cunha AD Jr. Acute nephrotoxicity of cisplatin: molecular mechanisms. J Bras Nefrol 35: 332–340, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pittock ST, Norby SM, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Bren GD, Badley AD, Caplice NM, Griffin MD, Nath KA. MCP-1 is up-regulated in unstressed and stressed HO-1 knockout mice: pathophysiologic correlates. Kidney Int 68: 611–622, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Heme oxygenase 1 is required for mammalian iron reutilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10919–10924, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Reduced stress defense in heme oxygenase 1-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10925–10930, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramesh G, Reeves WB. p38 MAP kinase inhibition ameliorates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F166–F174, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rankin EB, Tomaszewski JE, Haase VH. Renal cyst development in mice with conditional inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Cancer Res 66: 2576–2583, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberger C, Goldfarb M, Shina A, Bachmann S, Frei U, Eckardt KU, Schrader T, Rosen S, Heyman SN. Evidence for sustained renal hypoxia and transient hypoxia adaptation in experimental rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1135–1143, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimizu H, Takahashi T, Suzuki T, Yamasaki A, Fujiwara T, Odaka Y, Hirakawa M, Fujita H, Akagi R. Protective effect of heme oxygenase induction in ischemic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med 28: 809–817, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimizu M, Ohta K, Yang Y, Nakai A, Toma T, Saikawa Y, Kasahara Y, Yachie A, Yokoyama H, Seki H, Koizumi S. Glomerular proteinuria induces heme oxygenase-1 gene expression within renal epithelial cells. Pediatr Res 58: 666–671, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shiraishi F, Curtis LM, Truong L, Poss K, Visner GA, Madsen K, Nick HS, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 gene ablation or expression modulates cisplatin-induced renal tubular apoptosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F726–F736, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva G, Cunha A, Gregoire IP, Seldon MP, Soares MP. The antiapoptotic effect of heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial cells involves the degradation of p38 alpha MAPK isoform. J Immunol 177: 1894–1903, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stec DE, Drummond HA, Gousette MU, Storm MV, Abraham NG, Csongradi E. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in thick ascending loop of Henle attenuates angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 834–841, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suttner DM, Dennery PA. Reversal of HO-1 related cytoprotection with increased expression is due to reactive iron. FASEB J 13: 1800–1809, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takahashi N, Boysen G, Li F, Li Y, Swenberg JA. Tandem mass spectrometry measurements of creatinine in mouse plasma and urine for determining glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 71: 266–271, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 61: 748–755, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tracz MJ, Juncos JP, Croatt AJ, Ackerman AW, Grande JP, Knutson KL, Kane GC, Terzic A, Griffin MD, Nath KA. Deficiency of heme oxygenase-1 impairs renal hemodynamics and exaggerates systemic inflammatory responses to renal ischemia. Kidney Int 72: 1073–1080, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tzima S, Victoratos P, Kranidioti K, Alexiou M, Kollias G. Myeloid heme oxygenase-1 regulates innate immunity and autoimmunity by modulating IFN-beta production. J Exp Med 206: 1167–1179, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villanueva S, Cespedes C, Gonzalez AA, Vio CP, Velarde V. Effect of ischemic acute renal damage on the expression of COX-2 and oxidative stress-related elements in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1364–F1371, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vogt BA, Shanley TP, Croatt A, Alam J, Johnson KJ, Nath KA. Glomerular inflammation induces resistance to tubular injury in the rat. A novel form of acquired, heme oxygenase-dependent resistance to renal injury. J Clin Invest 98: 2139–2145, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vulapalli SR, Chen Z, Chua BH, Wang T, Liang CS. Cardioselective overexpression of HO-1 prevents I/R-induced cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H688–H694, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wagener FA, Feldman E, de Witte T, Abraham NG. Heme induces the expression of adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E selectin in vascular endothelial cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 216: 456–463, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao X, Panichpisal K, Kurtzman N, Nugent K. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: a review. Am J Med Sci 334: 115–124, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zager RA. Marked protection against acute renal and hepatic injury after nitrited myoglobin + tin protoporphyrin administration. Transl Res 166: 485–501, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zager RA, Burkhart KM, Conrad DS, Gmur DJ. Iron, heme oxygenase, and glutathione: effects on myohemoglobinuric proximal tubular injury. Kidney Int 48: 1624–1634, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarjou A, Bolisetty S, Joseph R, Traylor A, Apostolov EO, Arosio P, Balla J, Verlander J, Darshan D, Kuhn LC, Agarwal A. Proximal tubule H-ferritin mediates iron trafficking in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 123: 4423–4434, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]