Abstract

First-generation college students (students for whom neither parent has a 4-year college degree) earn lower grades and worry more about whether they belong in college, compared to continuing-generation students (who have at least one parent with a 4-year college degree). We conducted a longitudinal follow-up of participants from a study in which a values-affirmation intervention improved performance in a biology course for first-generation college students, and found that the treatment effect on grades persisted three years later. First-generation students in the treatment condition obtained a GPA that was, on average, .18 points higher than first-generation students in the control condition, three years after values affirmation was implemented (Study 1A). We explored mechanisms by testing if the values-affirmation effects were predicated on first-generation students reflecting on interdependent values (thus affirming their values that are consistent with working-class culture) or independent values (thus affirming their values that are consistent with the culture of higher education). We found that when first-generation students wrote about their independence, they obtained higher grades (both in the semester in which values affirmation was implemented and in subsequent semesters) and felt less concerned about their background. In a separate laboratory experiment (Study 2) we manipulated the extent to which participants wrote about independence and found that encouraging first-generation students to write more about their independence improved their performance on a math test. These studies highlight the potential of having FG students focus on their own independence.

Keywords: social class, achievement gap, first-generation students, values affirmation

First-generation (FG) college students – for whom neither parent has a four-year degree – comprise over 20% of enrolled college students (Chen, 2005), but they face a number of economic and social barriers and tend to struggle in their college courses. Compared to continuing-generation (CG) students – for whom at least one parent has a four-year degree – FG students perform more poorly in college, have higher drop-out rates, and report more difficulty adapting to college (Sirin, 2005; Terenzini, Springer, Yaeger, Pascarella, & Nora, 1996). The higher dropout rate carries unfortunate economic consequences, as college graduates earn over 95% more in their weekly salaries than individuals with only a high school diploma (Autor, 2014). Researchers consider parental education to be a proxy for social class, and thus the performance gap between FG and CG students has been referred to as the social-class achievement gap (Jackman & Jackman, 1983; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Snibbe & Markus, 2005; Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson, & Covarrubias, 2012). This social-class achievement gap is due, in part, to the lack of resources available to FG students. In addition to having less parental guidance for navigating higher education, FG students are more likely to come from working class backgrounds or poverty (Reardon, 2011; Saenz, Hurtado, Barrera, Wolf, & Yeung, 2007), and attend lower quality high schools that may lack the academic rigor required for students to excel in college (Terenzini et al., 1996; Warburton, Bugarin, & Nunez, 2001).

The social-class achievement gap may also reflect psychological factors related to how FG students experience the college environment. Previous research indicates that FG students sometimes feel stereotyped and worry about “fitting in” at college, which carries detrimental consequences for their academic performance (Croizet & Claire, 1998; Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Johnson, Richeson, & Finkel, 2011; Ostrove & Long, 2007; Smeding, Darnon, Souchal, Toczek-Capelle, & Butera, 2013; Stephens, Fryberg, et al., 2012). In fact, one study demonstrated that the social class achievement gap in college GPAs was mediated by the lack of academic fit perceived by students from lower social class backgrounds (Ostrove & Long, 2007). That is, students from lower social class backgrounds reported feeling less like they belonged in college, and this difference accounted for their lower overall GPAs (Ostrove & Long, 2007). Many researchers have documented that FG students have concerns about academic fit (e.g., Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2011; Ostrove & Long, 2007) and a recent theory suggests that this could be due to FG students’ perceptions of university norms as being discrepant from their own motives for attending college (Stephens, Fryberg, et al., 2012). The research reported here addresses these social-class gaps in an introductory university biology course and has two components. The first is a longitudinal follow-up of students who participated in a values-affirmation intervention (or control), to determine whether the positive effects persisted 3 years later, and whether the effects involved reflection on interdependent or independent values. The second component is a laboratory experiment in which writing about independent values was experimentally manipulated.

Cultural Mismatch Theory

Stephens, Fryberg, et al. (2012) posited that FG students contend with identity threat due to a mismatch between their personal values and the institutional values implicit in university settings. In particular, they argued that FG students face an unseen disadvantage due to a cultural mismatch between the middle-class norms of independence reflected in the American university system and their own interdependent motives for attending college. Whereas a culture of independence may be familiar and comfortable to middle-class students, it can be experienced as threatening by many FG students who may have been socialized with more interdependent norms (i.e., being part of a community, and connecting with others). Indeed, research has demonstrated that FG students are more likely than CG students to report that interdependent motives, such as giving back to the community or helping their family after they finish college, are important reasons for completing their college degree (Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Stephens, Fryberg, et al., 2012). Thus, the independent focus of American universities (i.e., emphasis on personal development and achievement) may inadvertently function as a social identity threat to FG students, who tend to be more interdependent in motivational orientation (Stephens, Townsend, Markus, & Phillips, 2012).

Stephens, Fryberg, et al. (2012) found that university administrators were more likely to emphasize the importance of independent skills (e.g., working independently) than interdependent skills (e.g., working collaboratively in groups) and similarly, that CG freshmen endorsed more independent motives for attending college than interdependent motives. In contrast, FG students entered college with more interdependent and fewer independent motives for attending college than their CG peers. Furthermore, a match between motives for attending college and university norms (as was the case for CG students) versus a mismatch (as was the case for FG students) carried critical consequences for academic performance: independent motives for attending college were positively correlated with course grades over a two-year period, whereas interdependent motives for attending college were negatively related to grades. In fact, they found that the degree to which students endorsed independent and interdependent motives mediated the relationship between socio-economic status and academic performance during the first two years of college. Relatedly, Stephens, Townsend et al. (2012) have also demonstrated that FG students experience the independent culture of higher education as a more stressful and difficult environment than CG students.

One way to alleviate this cultural mismatch is to change students’ perceptions of the environment to be more consistent with their values (i.e., create a cultural match). In an experimental study, Stephens, Fryberg et al. (2012) varied the depiction of university norms in a welcome letter ostensibly written by the university president. They found that when the university culture was depicted as more interdependent (with an emphasis on working together, participating in collaborative research, and learning from others), FG students performed as well as CG students on subsequent achievement tasks. Conversely, when the culture was described as more independent (with an emphasis on creating your own intellectual journey and participating in independent research), FG students perceived the subsequent task as more difficult and performed more poorly than CG students.

These results suggest that changing the environment to create a cultural match between students’ motives for attending college and the academic environment can improve academic success. However, a different way to address the mismatch may be to help students focus on personal values that are consistent with the environment. In other words, when students’ values are experienced as inconsistent with the university context, there are two ways to address the mismatch – either by changing the perception of the context, or by helping students focus on their own values that are consistent with the educational context. Indeed, all college students, both CG and FG, typically endorse a combination of values, some independent, some interdependent, and the extent to which specific personal values become salient can be influenced by situational cues. We hypothesized that this mismatch could be alleviated when FG students reflect on their own independent values.

Values Affirmation

One intervention that has proven effective at leveraging students’ self-perceptions and values to improve academic performance is values affirmation. Values affirmation (VA) is predicated on affirming core personal values to establish a perception of self-integrity and self-worth that, in turn, alleviates stress and helps students address challenges (see McQueen & Klein, 2006; Cohen & Sherman, 2014, for reviews). When students are confronted with social identity threats, they experience anxiety that can impair performance on challenging academic tasks (Steele, 1997). By reflecting on their core values in a brief writing assignment, however, students can bolster their self-integrity, making identity threats less salient and enabling students to dedicate more cognitive resources to the relevant academic task (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). The VA technique has proven effective in promoting the academic performance of underrepresented groups who experience identity threat in evaluative settings. For example, VA interventions have successfully reduced racial achievement gaps in middle school (Cohen, Garcia, Apfel, & Master, 2006; Hanselman, Bruch, Gamoran, & Borman, 2014; Sherman et al., 2013), a gender gap in a college physics class (Miyake et al., 2010), and the social-class achievement gap in a college biology class (Harackiewicz, Canning et al. 2014).

Recent research suggests that VA effects may be driven by students’ tendencies to write about why their important values make them feel connected to other people (Shnabel, Purdie-Vaughns, Cook, Garcia, & Cohen, 2013). By writing about interpersonal connections and making students’ interdependence more salient, students are reminded of the social support available to them, and this may enable them to perform up to their full potential, even when contending with social identity threats. Shnabel et al. examined the content of essays from the original Cohen et al. (2006) study in which a VA intervention reduced the racial-achievement gap in middle school. Specifically, they coded the VA essays for themes of interdependence and found that Black seventh graders wrote significantly more about their social bonds and interpersonal connections in the affirmation condition (compared to the control condition). Mediation analyses revealed that writing about interpersonal connections with others mediated the positive effect of VA for Black students. Although Shnabel et al. referred to writing about interpersonal connections as affirming “social belonging,” we believe this is comparable to affirming interdependence and will use the term “interdependence” for consistency with the current analysis.

Shnabel et al. (2013) also manipulated the extent to which students wrote about interdependence in a laboratory study with White undergraduates. Some participants were encouraged to write about how their chosen values made them feel closer and more connected with others (i.e., affirm their interdependence) and some completed a standard VA exercise. They found that women performed better on a math test when they were encouraged to write about interpersonal connections in their VA essays. Considered together, these studies suggest that writing about interdependence in VA essays can be an effective way to promote academic performance for students facing identity threat. Shnabel et al. posited that writing about valued social bonds reminds threatened individuals of their meaningful connections with significant others which then bolsters their self-integrity and effectively buffers students from the negative consequences of identity threat. This could apply to FG students as well.

On the one hand, reflecting on interpersonal connections and interdependent values may provide emotional resources for FG students that help them cope with academic challenges. Conversely, focusing on interdependent values might exacerbate feelings of cultural mismatch, and could conceivably impair performance. Thus, writing about interdependence may or may not be a plausible mediator of VA effects for FG students. It also seems possible that reflecting on personal independence may help FG students feel more aligned with the independent culture of higher education, thereby fostering an increased sense of academic fit and better performance. It is important to note that reflecting on independence in VA essays need not come at the expense of affirming interdependence. For example, Shnabel et al. (2013) noted that many VA essays contained both themes, as students often wrote about both interpersonal connections and their independence in a single essay. Reflecting on their independence may in fact be beneficial for their academic performance and success in college.

Affirming independent values that are consistent with the college context and learning environment may benefit FG students by helping them feel more like they belong in college. Given that FG students’ predominant motivation for attending college is “mismatched” with university contexts that encourage independence and individuality, we hypothesize that it will be adaptive for FG students to reflect on the kinds of values promoted in higher education and write about why these values are personally important. In this way, affirming independence could foster a cultural match for FG students without compromising their interdependent motives.

Another line of support for this hypothesis comes from research on identity-based motivation, which has shown that when an activity or situation feels congruent with one’s identity, college students are more motivated, academically engaged, and perform better (Oyserman & Destin, 2010). A fundamental tenet of identity-based motivation is that identities are multi-faceted and context dependent. People interpret situations and difficulties differently depending on which identity or self-concept becomes activated, and they tend to prefer identity-congruent actions (Oyserman & Destin, 2010). If an activity is perceived as identity congruent, difficulties are interpreted as important and meaningful challenges, leading to more engagement. Conversely, if an activity is perceived as incongruent with one’s identity, the task loses meaning and may be construed as “not for people like me.” By reflecting on the personal importance of independence, FG students may counteract the effects of cultural mismatch by activating an identity that is more congruent with the university culture, resulting in increased motivation, stronger perceptions of academic fit, and ultimately, better academic performance.

Overview of Studies

In their original study, Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) found that, relative to FG students in the control condition, FG students who were asked to affirm their most important values obtained better grades in their introductory biology course, as well as in other courses taken that semester, and were significantly less concerned about their academic background at the end of the semester. The goals of the present research were (a) to examine whether these performance effects observed in an introductory biology course persisted over subsequent semesters (Study 1A), (b) to examine whether either independence or interdependence, measured with multiple methods, accounted for the effect of the intervention on performance and on students’ concern about their background (Study 1B and 1C), and (c) to test our hypotheses experimentally by manipulating the extent to which students wrote about independence and interdependence in VA essays and testing the effects on performance on a math test (Study 2). We hypothesized that the VA effects first observed by Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) would be long-lasting, and that these effects would be mediated by writing about independence. Furthermore, we hypothesized that writing about independence would have a causal effect on performance in the laboratory study.

Study 1A: Testing Long-Term Effects of the Values-Affirmation Intervention

Researchers posit that VA interventions have long-lasting effects on academic performance because VA has the potential to trigger positive and reciprocally reinforcing outcomes (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). That is, VA can lead to better performance, and this improved performance may further affirm the self, leading to still better performance, thus building on itself and creating a recursive process. Previous research has shown that underrepresented minority middle school students who received a VA intervention continued to earn higher grades than their peers in the control group two or three years after the initial intervention (Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, & Brzustoski, 2009; Sherman et al., 2013) but such long-term VA effects have never been demonstrated in college. We predicted that the VA effects first observed by Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) would persist such that FG students in the VA condition would obtain higher subsequent grades than FG students in the control condition. We examined students’ academic performance after the semester in which VA was implemented in two separate analyses. We first conducted a sequential time-course analysis examining grades in each of the three semesters following the intervention (a time period in which the majority of the original Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) sample was still enrolled in college).

We then conducted longer-term follow-up analyses, three years after the intervention, and examined students’ final or current post-intervention GPA. For most students, this was their post-intervention GPA at graduation, for others, it was their final post-intervention GPA prior to dropping out or transferring from the university, and for the remaining students, it was their current post-intervention GPA, because they were still enrolled in college, three years after the intervention. These follow-up analyses allowed us to examine academic performance for students in the three semesters immediately after the intervention and over a three-year period.

Method

In the original Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) study, 798 students were blocked on generational status (644 CG students, 154 FG students), underrepresented minority status (737 Majority students, 61 underrepresented minority students), gender (478 women, 320 men), and lecture section and then randomly assigned to complete either a VA writing exercise or a control writing exercise as part of an undergraduate biology course. The writing assignments were integrated into the laboratory curriculum as practice writing exercises and administered twice, during the 2nd and 8th weeks of the 15-week semester. Students in the VA condition were instructed to circle their two or three most important values and then write about why those values were important to them. Students in the control condition were instructed to circle the two or three values that were least important to them and to write about why other people might hold those values. The values were: athletic ability; being good at art; belonging to a social group (such as your community, racial group, or school club); career; creativity; government or politics; independence; learning and gaining knowledge; music; relationships with family and friends; sense of humor; and spiritual or religious values. These materials were based on those used in previous studies (e.g., Miyake et al., 2010); full methodological details are reported in Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014). Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) found that FG students in the VA condition obtained higher grades in the biology course, as well as higher grades in their other courses that semester.

In the present study, we collected follow-up data to examine whether the intervention implemented in fall 2011, had long-term effects. In fall 2014, we conducted follow-up analyses in which we examined both semester grades over time and overall post-intervention GPAs. In the time-course analysis of non-cumulative semester grades, we computed students’ average grades for each of the 3 semesters following the one in which the VA intervention was implemented: spring 2012 (s1), fall 2012 (s2), and spring 2013 (s3). These were the semesters in which the vast majority of our original sample was still enrolled in classes. The number of students still enrolled in college diminished each semester after the intervention semester, due to graduation and dropping out. Thus it was not possible to extend time-course analyses further without compromising the sample. By focusing our time-course analyses on the three semesters following the one in which VA was administered, we were able to retain 94% of our original sample.1

For our analyses of post-intervention GPA, however, we were able to retain 99% of the original sample. Only ten students from the original sample did not take any more courses at this university after the intervention, meaning that we could compute a post-intervention GPA for 788 out of the 798 students in the original Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) sample. For students who had graduated (64%), we used their post-intervention GPA at graduation; for students currently enrolled (30%), we used their current post-intervention GPA, and for students who had dropped or transferred (6%), we used their most recent post-intervention GPA. Thus we examined the most current or final post-intervention GPA for all students over a three-year time period.

Measures

Grades at this university are on a 4.0 scale (A = 4.0, AB = 3.5, B = 3.0, BC = 2.5, C = 2.0, D = 1.0, F = 0). GPAs were calculated by dividing the total number of grade points awarded to students by the total number of credits taken (including F credits) for all courses taken after the intervention semester. Concern about background was measured at the beginning and end of the intervention semester with a single item (“I am not sure I have the right background for this course”) on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all true to very true.

Samples

To examine semester grades in the three semesters following the one in which VA was implemented (fall 2011), we used grades for all students who took classes for at least two of those three semesters. This sample includes 749 of the 798 students in the original study. The 49 students not included in these analyses either graduated by June 2012 (4 students), took 2 or more semesters off during the 3 semesters following fall 2011 (11 students), or had dropped out or transferred by spring of 2013 (34 students).2 In addition to the 49 students not included in this analysis, there were also 17 students who enrolled in only two of the three semesters (i.e., they took a single semester off); for these students, we used multiple imputation to estimate their GPAs for the semester in which they were not enrolled.3 Thus, our sample for semester grade analyses consisted of 608 CG students (304 in the control condition and 304 in the VA condition) and 141 FG students (69 in the control condition and 72 in the VA condition).

For the three-year follow-up analyses, our sample consisted of 788 of the original 798 students in the Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) study. Ten students did not take any courses after the fall 2011 semester and were therefore not included in any follow-up analyses. We computed a post-intervention GPA for these 788 students: a post-intervention final GPA for students who had graduated since fall 2011 (n = 505), a post-intervention final GPA for students who dropped out or transferred (n = 48) and a current post-intervention GPA for students still enrolled at the university (n = 235).4 The final sample for post-intervention GPA analyses consisted of 638 CG students (315 in the control condition and 323 in the VA condition) and 150 FG students (74 in the control condition and 76 in the VA condition).

Semester Grades Over Time

To explore how VA effects unfolded over time, we conducted a time course analysis examining students’ semester grades in the three semesters immediately following the intervention. We conducted a 2 (condition: control vs. VA) × 2 (generational status: CG students vs. FG students) × 3 (Time: spring 2012 semester [s1] vs. fall 2012 semester [s2] vs. spring 2013 semester [s3]) mixed-model ANCOVA with repeated measures on Time and gender as a covariate. Because students took the introductory biology course at different points in their academic careers, and had different numbers of academic credits left to take before graduation, we also controlled for their year in school when the course was taken (e.g., freshman, sophomore, junior or senior) in any analyses with post-intervention academic performance as a dependent variable.5 All possible interactions between condition, generational status, and gender were also tested; none of the gender interaction terms were significant and therefore all were subsequently trimmed from the model.

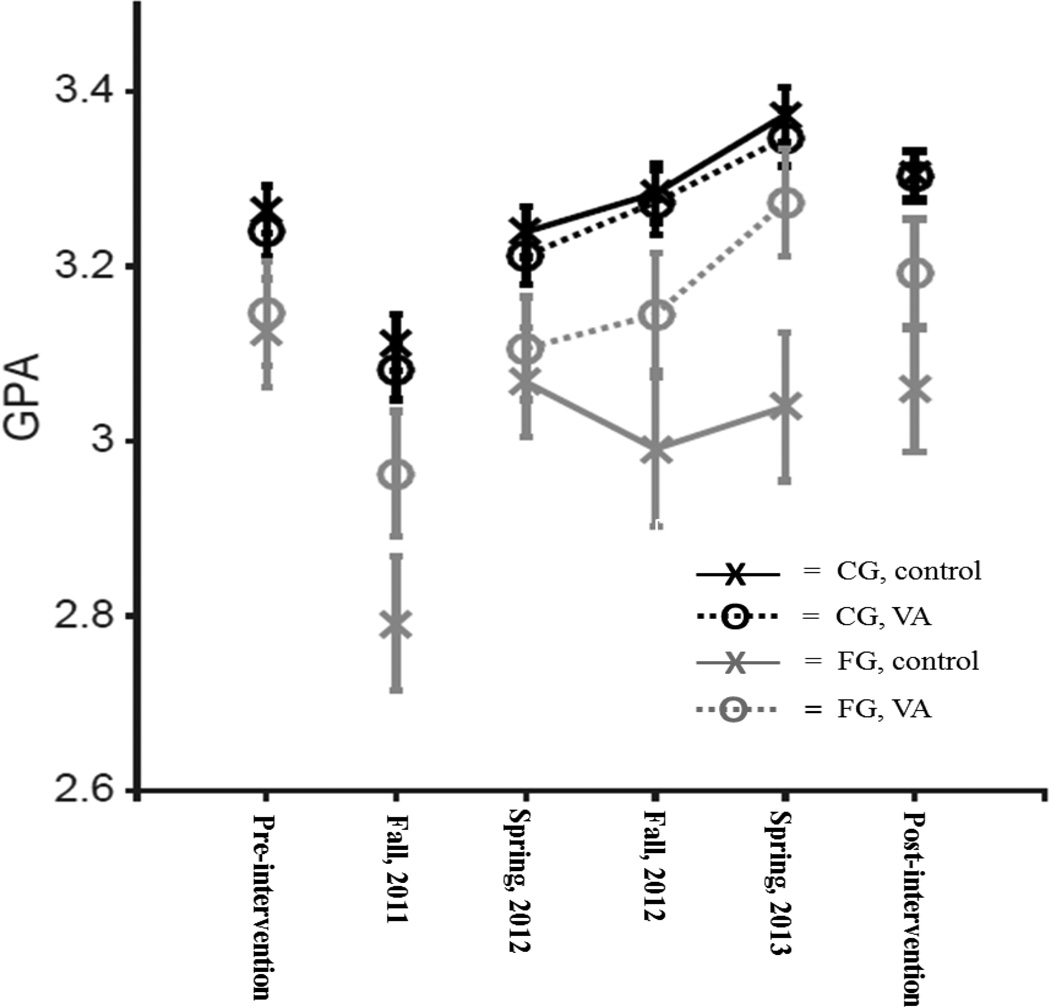

The analysis yielded a significant main effect of generational status, F(1, 745) = 4.29, p = .04, which indicated that, on average, FG students’ semester grades (M = 3.11, SD = 0.60) were lower than the GPAs of CG students (M = 3.29, SD = 0.57). A main effect of gender indicated that females had higher semester grades (M = 3.30, SD = 0.51) than males (M = 3.17, SD = 0.68), F(1, 745) = 11.97, p < .001, and a main effect of time indicated that, on average, students’ grades improved over the course of the three semesters (Ms = 3.20S1, 3.24S2, 3.32S3; SDs = 0.54S1, 0.63S2, 0.58S3). A two-way interaction between time and condition emerged, F(1, 745) = 4.82, p = .03; however this interaction was qualified by a significant three-way interaction (Time × Condition × Generational Status), F(1, 745) = 4.75, p = .03. In order to decompose the three-way interaction, simple effects tests compared the effect of condition over time first for FG students and then for CG students. These analyses revealed that over time, FG students’ semester grades were significantly higher in the VA condition (Ms = 3.11S1, 3.15S2, 3.27S3; SDs = 0.50S1, 0.60S2, 0.53S3) than in the control condition (Ms = 3.07S1, 2.99S2, 3.04S3; SDs = 0.52S1, 0.74S2, 0.70S3), F(1, 745) = 5.89, p = .02. Conversely, CG students’ grades did not vary over time as a function of VA condition, F(1, 745) = 0.00, p = .99 (within VA: Ms = 3.21S1, 3.27S2, 3.35S3; SDs = 0.58S1, 0.64S2, 0.56S3; within control: Ms = 3.24S1, 3.28S2, 3.37S3; SDs = 0.50S1, 0.59S2, 0.56S3). Figure 1 shows the effects of VA on semester grades over time reported here, in the context of the original VA effect. Specifically, it shows that students’ academic performance did not differ by condition on pre-intervention GPA, but did differ in the semester in which VA was implemented (fall 2011) and in the three subsequent semesters as documented above; FG students in the VA condition earned higher grades than FG students in the control condition.

Figure 1.

GPAs with +/−1 standard error for performance among continuing-generation (CG) and first-generation (FG) students as a function of values affirmation (VA) condition; N = 749. Fall 2011 is the semester in which VA was implemented. Pre-intervention and post-intervention grade point averages (GPAs) are cumulative. Fall 2011, Spring 2012, Fall 2012, and Spring 2013 are semester GPAs.

Post-Intervention GPA

Our basic regression model tested the effects of condition (control = −1, VA intervention = 1), generational status (CG students = −1, FG students = 1), the condition by generational status interaction, gender (females = −1, males = 1), and year in school when the biology course was taken. All possible interactions between condition, generational status, and gender were tested; none of the gender interaction terms were significant and therefore all were subsequently trimmed from the model.

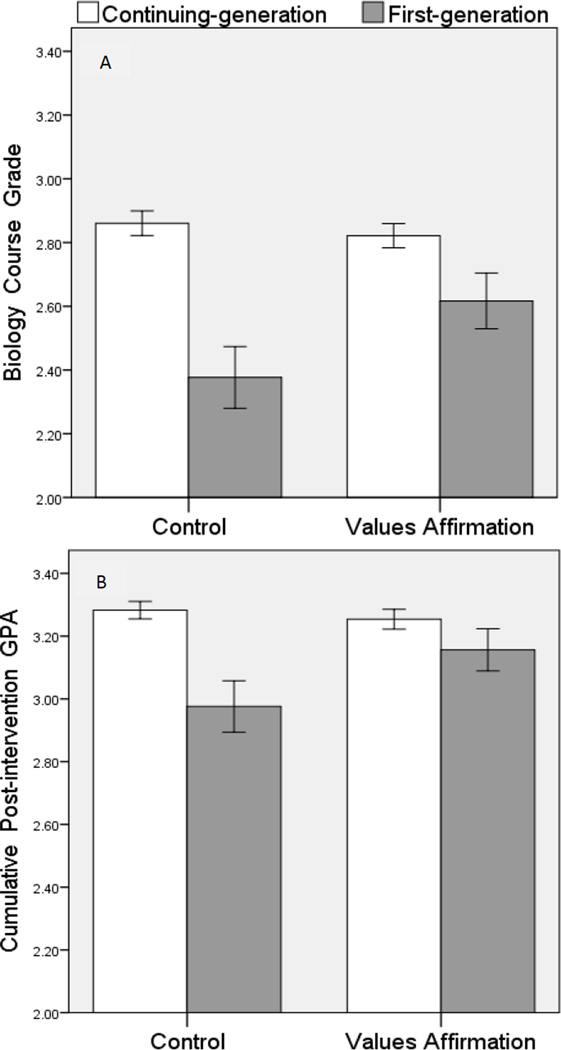

Regression analyses indicated that there was a main effect of generational status such that CG students obtained higher cumulative post-intervention GPAs (M = 3.27, SD = 0.54) than FG students (M = 3.07, SD = 0.65); t(782) = 4.31, p < .001, β = −0.15, revealing a social class achievement gap in post-intervention GPA. However, this main effect was qualified by the predicted interaction with VA condition, t(782) = 2.22, p = .03, β = 0.10, indicating that FG students in the VA condition (M = 3.16, SD = 0.58) obtained higher post-intervention GPAs than FG students in the control condition (M = 2.98 SD = 0.70). CG students performed similarly in the VA condition (M = 3.25 SD = 0.57) and the control condition (M = 3.28 SD = 0.49). Whereas the achievement gap was moderate in the control condition (0.31 GPA points), Cohen’s d = .33, t(782) = 4.59, p < .001, it was substantially smaller (and non-significant) in the VA condition (.10 GPA points), Cohen’s d = .11, t(782) = 1.50, p = .14, reflecting a treatment effect of .18 grade points, resulting in a 59% reduction of the social class achievement gap in post-intervention cumulative GPA. Finally, a main effect of gender indicated that females had significantly higher post-intervention cumulative GPAs (M = 3.30, SD = 0.49) than males (M = 3.13, SD = 0.65), t(782) = 4.58, p < .001, β = −0.16. Figure 2 shows the original VA effect on course grade as well as the effect on post-intervention cumulative GPA documented here; Table 1 shows the full regression model for this analysis.

Figure 2.

Mean biology course grade (Panel A) and post-intervention GPA (Panel B) with +/−1 standard error for performance among continuing-generation and first-generation students as a function of values affirmation condition; N = 798 in Panel A; N = 788 in Panel B.

Table 1.

Study 1A: Regression Analysis of Cumulative Post-intervention GPA

| Regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

| B | β | t (df) | p | B | β | t (df) | p | |

| Post-Intervention GPA | ||||||||

| Condition | .04 | 0.07 | 1.57 (1, 782) | .118 | .04 | 0.08 | 2.12 (1, 781) | .034 |

| Generational Status | .11 | −0.15 | 4.31 (1, 782) | .000 | .07 | −0.09 | 3.10 (1, 781) | .002 |

| Condition × Generational Status | .06 | 0.10 | 2.22 (1, 782) | .027 | .05 | 0.09 | 0.23 (1, 781) | .013 |

| Gender | .09 | −0.16 | 4.58 (1, 782) | .000 | .07 | −0.19 | 4.42 (1, 781) | .000 |

| Year In School | .01 | −0.13 | 0.38 (1, 782) | .704 | .01 | 0.01 | 0.25 (1, 781) | .800 |

| Performance Covariate | -- | -- | -- | -- | .30 | 0.55 | 18.65 (1, 781) | .000 |

Note. Two sets of regressions examining effects on post-intervention GPA are presented here. Model 1 displays the in-text reported effects on post-intervention GPA. Model 2 shows these same effects but also includes a baseline covariate (a standardized composite measure of students’ prior semester GPA, ACT, and SAT) that was used in the Harackiewicz, Canning et al. (2014) original study.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 indicate that the VA intervention had long-lasting effects on academic performance for FG students. This finding is consistent with long-term effects documented by Cohen et al. (2009) and Sherman et al. (2013) in middle-school populations, but it is the first demonstration of a long-term VA effect with FG college students. Indeed, the brief VA intervention, implemented twice in an early foundational course, had far-reaching effects that may have changed students’ academic trajectories. Three years after the intervention, FG students in the VA condition, on average, had maintained a GPA .18 grade points higher than FG students in the control condition. This moderate boost in GPA might increase the options for graduate education or career training, especially considering that average performance for FG students rose from the B range in the control condition (M = 2.98) to the B+ range in the VA condition (M = 3.16). FG students who may otherwise have fallen just below an important performance cutoff (i.e., 3.0 GPA) may have been able to cross that academic barrier and fulfill their potential because of the VA intervention.

The analyses on semester grades provide insight regarding how the social-class achievement gap may unfold over time. For most students in the current sample (i.e., CG students and FG students in the VA condition) and consistent with patterns of college performance rates (Betts & Morell, 1999; Geiser & Santelices, 2007; Grove & Wasserman, 2004; UW-Registrar, 2015), semester grades improved over time. As students become acclimated to college they may gain a better understanding of the skills and study habits necessary for successful degree completion. However, this pattern of improving performance is not seen in the GPA trajectories of FG students in the control condition. These FG students did not improve at the same rate as CG students, and in some cases, their semester grades even worsened relative to previous semesters. It may be that values affirmation helps students adjust to the ongoing challenges of college coursework, and our results suggests that intervention early in the course of students’ academic careers may yield long-term benefits. Given the power of the VA intervention to influence performance in the short and long term, it is important to examine the mechanisms through which it works.

Study 1B: Exploring Mediation Through Content Analyses

Study 1B involved new analyses and coding of the essays written by students in the Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) study. Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) noted that FG and CG students did not select different values to write about in the VA condition, indicating that the positive VA effects were not driven by differential selection of values. Thus, in the present study, we examined the content of students’ essays in order to identify if VA effects were driven by differences in how students wrote about their selected values. Specifically, VA essays were coded for themes of independence and interdependence so that these two constructs could be tested as mediators of the positive effects of VA for FG students. We also examined the interrelationship of independent and interdependent themes in VA essays to examine the extent to which students wrote about independence, interdependence, or a combination of both in their essays. All essays (both control and VA) were first coded by the research team (Study 1B). We then conducted a linguistic text analysis of the VA essays (Study 1C) to further explore causal mechanisms.

Holistic Coding of Interdependent and Independent Writing

All essays were coded using a binary coding scheme for the presence or absence of interdependent and independent themes. The criteria for coding interdependent themes were identical to those employed by Shnabel et al. (2013) for social belonging,6 defined as: an explicit mention of (1) valuing an activity because it is done with others, (2) feeling part of a group of people because of a certain value or while engaging in a certain activity, or (3) any related thoughts on the subject of one’s interdependence, such as being affiliated with or liked by others.

We developed a new coding system for independent themes using similar guidelines. Specifically, independent themes were defined as (1) valuing an activity because it is done alone, (2) explicitly expressing the value of independence for the self, or (3) any related thoughts showing that the participant values his or her own autonomy (i.e., the ability to make her or his own decisions and have his or her own ideas and opinions).

Each essay was coded for independent and interdependent themes by at least two trained coders, and we maintained high inter-rater reliability for both independence (Cohen’s kappa = .96) and interdependence (Cohen’s kappa = .89) coding (Landis & Koch, 1977). Initial agreement among coders was over 90%, and for the few instances in which coders did not agree, a third coder was consulted to resolve any ambiguity. Because participants wrote two essays over the course of the semester, they received two scores for independence and two scores for interdependence. Each pair of scores was summed to create a single score that reflected the extent to which students wrote about independent and interdependent themes across the two essays (i.e., scores could be 0, 1, or 2 for each measure).

Although students were not asked to reflect on personal values in the control condition (rather, they were prompted to write about why their least important values might be valued by others), there were instances (10% of control essays) in which students wrote about their own independence, interdependence, or both in the control condition. This usually occurred when participants commented on their least important values by contrasting them with what they actually valued. For example, one control participant discussed their own independence by stating “Belonging to a social group may be important to someone else. I personally like to be more independent.” Similarly, several control essays included themes of interdependence, for example “There are people who live for art and their ability to be creative, I am just not one of them. Being with friends and family and religion are my top priorities.” Given the presence of self-relevant independent and interdependent themes in the control condition, we coded for both themes in both conditions.

Results

Table 2 provides sample quotes from essays that were coded as independent, interdependent, or both interdependent and independent. Across conditions, 10% of participants wrote about independence once (19% in VA conditions), 8% wrote about independence twice (17% in VA), and 82% of participants never wrote about independence (64% in VA). For interdependence, 11% wrote about interdependence once (14% in VA), 40% wrote about interdependence twice (78% in VA), and 49% never wrote about interdependence (8% in VA).

Table 2.

Study 1B: Sample Quotes from Values Affirmation Essays

| Independence | Interdependence | Both |

|---|---|---|

| Independence and learning and gaining knowledge are very important values to me. These are a few of the many reasons why I chose to go to college and further my education. The first full day at college after moving in was a dream come true. For once I finally felt independent and I had full control over my life and my future. Gaining knowledge and learning new things are very important. It means that I will be able to support myself in the future by having a successful career and being able to do the thing I want to in life. It makes me feel more important and that I am accomplishing something that means a lot. After graduating college, it will feel great to be on my own truly for once. By having a good job that pays well is important to me. It will allow me to pursue my hobbies and interests. Independence is a big one, especially in college, because it can be the difference between sinking and swimming. Being independent means being able to work or study without instruction, and being able to meet goals with very little external motivation. Without independence, college is basically meaningless. Being independent is an aspect of my life is of upmost importance to me. Choosing to attend college away from home was a large step in autonomy; living on my own, and making my own choices were large but necessary changes in my life in order for me to become independent and grow up into an adult. Also, the ability to study whatever I choose gave me great autonomy to explore my interests and learn about a wide variety of studies. Thus I have acquired more independence and knowledge with my transition into college. Acquiring these skills has made me feel successful as a young adult and student, I believe I gained a lot from this large transition from high school to college. Belonging to a social group may be important to someone else. I personally like to be more independent but there is nothing wrong with belonging to a social group and I’m sure it is a lot of fun for others. (control condition) |

Friends and family are extremely important to me. Having good relationships with them is essential to living a happy life. They’re the people who can provide me with help, empathy and condolence in times of sadness and need. They also are the people who make life fun because they’re the people I love. Belonging to a social group is important because you’re surrounding yourself by people who you have something in common with. I think it’s always beneficial to have people like this when friends and family can’t necessarily help you out. Talking or going to these people is a nice alternative support/ help group to have. My relationships with friends and family is definitely very important to me. These are the people who I go to for support and guidance. Knowing that I can count on them and they can count on me makes my life happier and more relaxed. Also, along with this having a social group to belong to is important. Being part of a team or club makes me feel like I am a part of something and that people count on me to do my best. These teams and clubs help me become a better person and allow me to be with people who are passionate about the same things as I am. I believe in being with my family and friends. I am happiest when I’m with them so it is very important to me. I love my friends and family and I don’t want to be in a world without them. I love hanging out with my friends and my family because it creates togetherness and stronger relationships. There are people who live for art and their ability to be creative, I am just not one of them. Being with family and friends and religion are my top priorities.” (control condition) |

I chose independence because I have learned in my previous year here at UW that independence is very important. I lived in Witte Hall last year so I was in the center of the social community of college students. There were always groups of people at the dorms who would get together for playing games, hanging out, or studying. I enjoyed participating in all of these activities but I realized that I need to dedicate more time to studying by myself and getting some alone time. After dedicating more of my schedule to independent time, I began to understand material better and got to know myself and my goals better. I have been working in a neuroscience research lab for the last two years. At first, I felt pretty overwhelmed by all of the knowledge and information I’d need to learn about the lab, but as time went on my curiosity drove me to learn and gain this knowledge. I was no longer dependent on my lab manager for every little piece of information. This independence in lab has really made me feel successful and self-sufficient in lab. I now run my own experiments and train new students who were in the exact same shoes as I was two years ago. I also have a friend who really cares about belonging to a social clique in her school. Honestly, I don’t care much for it because I have taught myself to be more independent and not rely on others to help me go far in life. I do value friendships, however, I just don’t stress about belonging to a specific group. (control condition) |

Notably, participants in the VA condition often wrote about both their independence and interdependence in their essays (see Table 3 for percentages of students who wrote about independence and interdependence in VA conditions). Furthermore, very few students wrote exclusively about independence; rather, the majority of students wrote about interdependence, and when students wrote about independence, it was generally in addition to writing about interdependence. In fact, of the participants who wrote about independence, 84% also wrote about interdependence, suggesting that writing about independence does not necessarily come at the expense of writing about interdependence. Importantly, this pattern of results did not differ as a function of generational status, p = .16.

Table 3.

Study 1B: Percentage of Students in the Values-Affirmation Condition Who Wrote About Independence and Interdependence

| Generational Status |

No Independence or Interdependence |

Only Independence |

Only Interdependence |

Both Interdependence and Independence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG Students | 4% | 6% | 62% | 28% |

| FG Students | 0% | 2% | 56% | 42% |

| All Students | 3% | 5% | 61% | 31% |

Note. CG = continuing-generation; FG = first-generation.

Regression Model

For models examining dependent variables that were measured in the semester in which VA was implemented (i.e., independent and interdependent themes, course grade, concern about background) we tested the basic model described earlier but included the same factors and interaction terms that were tested by Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014). Thus, unless otherwise specified, any analysis of dependent variables measured within the semester in which VA was implemented tested for the effects of condition (control = −1, VA = 1), generational status (CG students = −1, FG students = 1), the condition by generational status interaction, and gender (females = −1, males = 1), and also controlled for lecture section (two orthogonal codes to control for differences between the three sections of the class) and two interactions between generational status and lecture section.7 Gender interactions were initially tested in each analysis but then trimmed from all models as none were significant, p > .18.

Effect of VA Condition on Interdependent and Independent Themes

In order to test interdependent and independent writing as potential mediators of the positive VA effect for FG students, we first tested whether students in the VA condition wrote more about independence and/or interdependence in their essays than students in the control condition. We found a significant main effect for treatment condition on both independent and interdependent themes, t(789) = 11.08, p < .001; β = 0.45, and t(789) = 37.78, p < .001, β = 0.81, respectively, indicating that students wrote about both independence and interdependence significantly more often in the VA condition compared to the control condition, as expected. We also found a main effect of generational status indicating that FG students (M = 0.98, SD = 0.93) wrote more often about interdependence than CG students (M = 0.88, SD = 0.94), t(789) = 2.01, p = .04, β = 0.04. The frequency of writing about independent themes did not vary by generational status (p = .28) and there were no significant interactions between treatment condition and generational status on either independence (p = .23) or interdependence (p = .32). A significant main effect of gender also emerged indicating that females (M = 0.98, SD = 0.95) wrote more often about interdependence that males (M = 0.77, SD = 0.91), t(789) = 5.19, p < .001, β = −0.09.

Moderated Mediation Model

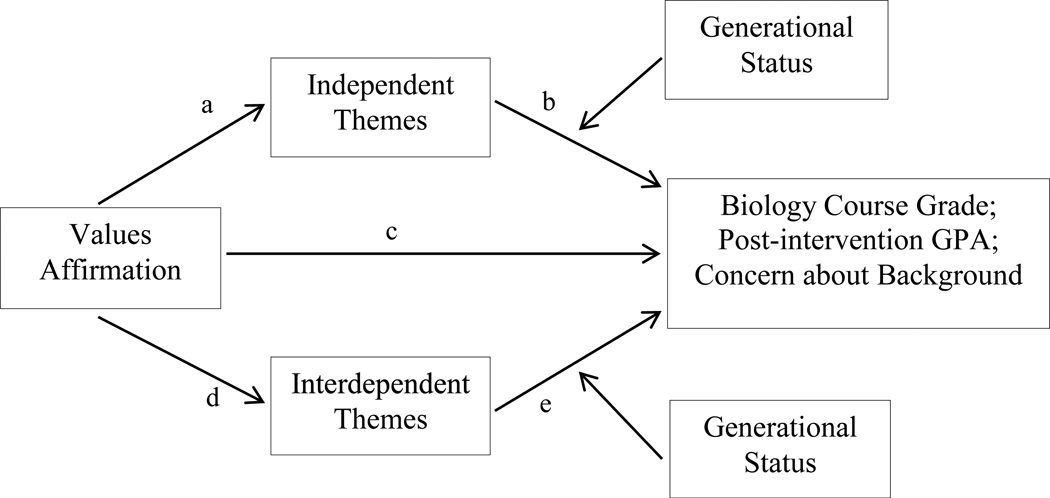

Figure 3 illustrates the mediation model tested. We used Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS software, which allowed us to test the indirect effects of VA on performance and concern about background through independent and interdependent themes as a function of generational status (i.e., a × b; and d × e; see Figure 3). In other words, these analyses allow us to examine if writing about independence or interdependence mediated VA effects on outcome variables (course grade, post-intervention GPA, and concern about background) and test if mediation effects were moderated by generational status. We predicted that any mediation effects would be moderated by generational status such that the mediator (writing about independence or writing about interdependence) would be a particularly strong predictor of intervention effects for FG students.

Figure 3.

Moderated Mediation Model.

Course grades

Table 4 summarizes the effects of VA condition on independent and interdependent themes, as well as the effects of VA, generational status, and the hypothesized mediators on final course grade. The “Conditional Indirect Effects” section of Table 4 shows the significance tests for the indirect effects of independent themes and interdependent themes as a function of generational status on course grade. The “Index of Moderated Mediation” tests if the indirect effect through each of the proposed mediators varied as a function of generational status. Given that the confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation for independent themes did not include zero (95% CI: = [0.028, 0.168]), we can conclude that the indirect effect of independence on course grade varied significantly as a function of generational status. Specifically, independent writing was a significant mediator for FG students (95% CI = [0.035, 0.167]) but was not a significant mediator for CG students (95% CI = [−0.031, 0.033]). Thus, students assigned to the VA condition wrote more often about independence than students in the control condition, and for FG students, writing about independence was associated with higher grades in the class.8 There were no significant indirect effects for interdependent themes, indicating that it was not a mediator for either CG or FG students.

Table 4.

Study 1B: Moderated Mediation of Effects of the Intervention on Course Grade

| Predictor | B | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Biology 151 Course Grade | |||||

| VA Intervention | −.001 | .074 | −.001 | .994 | |

| Generational status | −.260 | .045 | −5.719 | .000 | |

| Independent Themes | .117 | .049 | 2.402 | .017 | |

| Interdependent Themes | .002 | .078 | .026 | .979 | |

| Independence × Generational status | .114 | .047 | 2.430 | .015 | |

| Interdep × Generational status | .025 | .048 | .519 | .604 | |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | |||||

| Mediator | Index | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| Independent Themes | .095 | .037 | .028 | .168 | |

| Interdependent Themes | .042 | .094 | −.142 | .227 | |

| Conditional Indirect Effects | |||||

| Mediator | Generational status |

Boot indirect effect |

Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Independence | CG Students | .002 | .016 | −.031 | .033 |

| Independence | FG Students | .097 | .033 | .035 | .167 |

| Interdependence | CG Students | −.020 | .061 | −.141 | .099 |

| Interdependence | FG Students | .023 | .103 | −.182 | .223 |

Note. N = 798 (644 CG students, 154 FG students). Confidence intervals are reported with a bootstrap sample size = 5000. LLCI = lower level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval; ULCI = upper level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval. Condition and generational status were coded such that Control = −1 and VA = 1; similarly, CG students = −1 and FG students = 1. Testing each mediator separately revealed conceptually analogous results.

Post-intervention GPA

In the model testing for moderated mediation of post-intervention GPA, the confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation for independent themes did not include zero (95% CI = [0.041, 0.190]), indicating that the indirect effect of independent writing on post-intervention GPA varied as a function of generational status. Specifically, independent writing was a significant mediator for FG students (95% CI = [0.024, 0.155]) but was not a significant mediator for CG students (95% CI = [−0.069, 0.011]); see on-line supplemental materials for full moderated-mediation table. Thus, students assigned to the VA condition wrote more often about independence than students in the control condition, and for FG students, writing about independence was associated with better academic performance (i.e., higher GPAs) three years later. There were no significant indirect effects for interdependent themes, indicating that it was not a mediator for either CG or FG students.

Concern about background

Table 5 shows the effects of VA condition on independent and interdependent themes, as well as the effects of VA, generational status, and the hypothesized mediators on students’ concern about their background at the end of the semester. Because the effect on student’s concerns emerged over time in the Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) study, we controlled for baseline levels of concern in these models, for consistency with the original analyses. Given that the confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation for independent themes did not include zero (95% CI = [−0.149, −0.013]), we can conclude that the indirect effect of independent writing on students’ concern varied as a function of generational status. Specifically, independent writing was a significant mediator for FG students (95% CI = [−0.132, −0.009]), but was not a significant mediator for CG students (95% CI = [−0.026, 0.046]). Thus, FG students assigned to the VA condition wrote more often about independence than FG students in the control condition, and writing about independence was associated with less concern about their academic background over time (indirect effect b = −.07 for FG students, compared to b = .01 for CG students). There were no significant indirect effects for interdependent themes, indicating that it was not a mediator for either CG or FG students.

Table 5.

Study 1B: Moderated Mediation of the Effects of the Intervention on Concern About Background

| Predictor | B | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Concern about Background | |||||

| VA Intervention | −.053 | .067 | −.785 | .433 | |

| Generational status | .085 | .041 | 2.042 | .042 | |

| Independent Themes | −.070 | .045 | −1.558 | .120 | |

| Interdependent Themes | .055 | .071 | .771 | .441 | |

| Independence × Generational status | −.094 | .043 | −2.198 | .028 | |

| Interdepend. × Generational status | −.046 | .043 | −1.052 | .293 | |

| Baseline Concern about Background | .430 | .032 | 13.369 | .000 | |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | |||||

| Mediator | Index | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| Independent Themes | −.078 | .035 | −.149 | −.013 | |

| Interdependent Themes | −.079 | .085 | −.244 | .089 | |

| Conditional Indirect Effects | |||||

| Mediator | Generational status |

Boot indirect effect |

Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Independence | CG Students | .010 | .018 | −.026 | .046 |

| Independence | FG Students | −.068 | .031 | −.132 | −.009 |

| Interdependence | CG Students | .086 | .054 | −.019 | .195 |

| Interdependence | FG Students | .007 | .093 | −.173 | .191 |

Note. N = 796 (642 CG students, 154 FG students). Confidence intervals are reported with a bootstrap sample size = 5000. LLCI = lower level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval; ULCI = upper level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval. Condition and generational status were coded such that Control = −1 and VA = 1; similarly, CG students = −1 and FG students = 1. Testing each mediator separately revealed conceptually analogous results.

Decomposition of moderated mediation effects

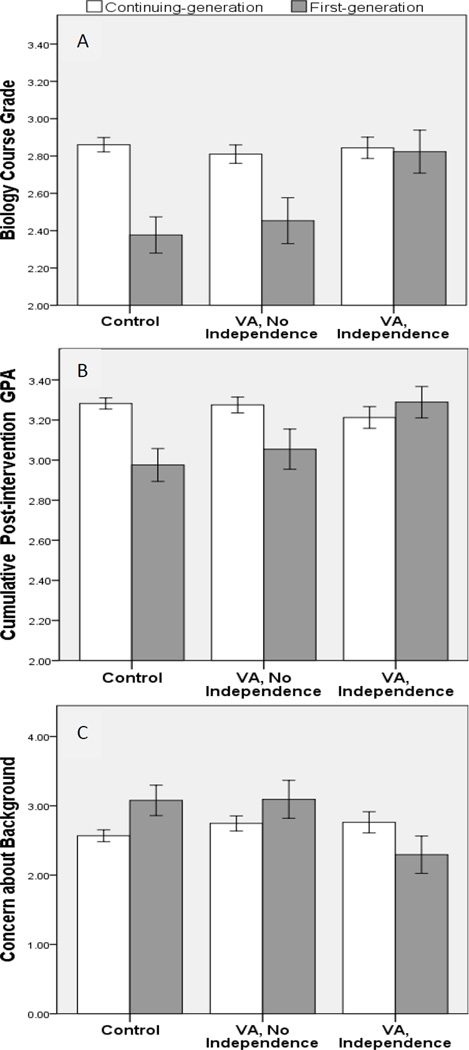

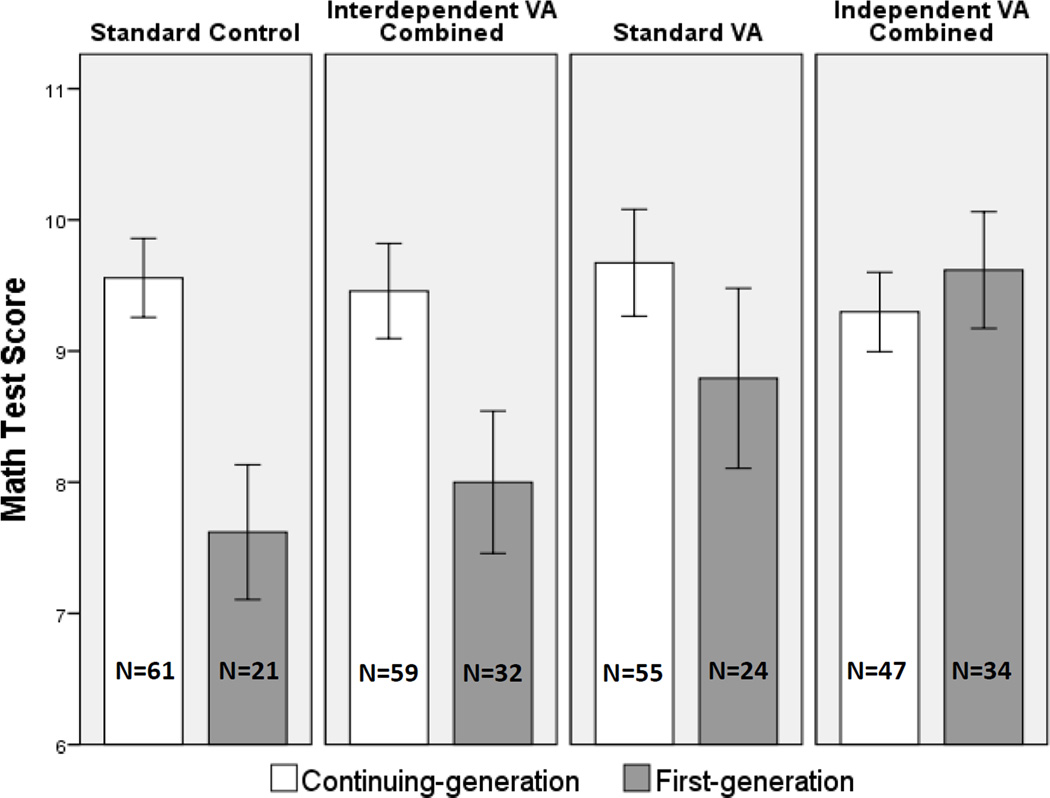

Our models tested mediating variables measured on a continuous scale (independent and interdependent writing were each coded on a 0–2 scale), as recommended by Hayes (2013). To depict the effect graphically, however, we recoded the three-level independent themes measure as a dichotomous measure in the VA condition and categorized students as never having written about independence versus those who did write about independence, either once or twice. Figure 4 shows this decomposition of the treatment effects on course grade, post-intervention GPA, and concern about background. The first panel shows results in the control group. The second and third panels in each graph represent two groups of students in the VA condition, those who never wrote about independence and those who did. We tested regression models with dummy codes using the control group for comparison, to examine performance and concern for students who did and did not write about independence in their VA essays. A significant interaction between generational status and the dummy code comparing students who affirmed their independence in VA to the control condition indicated that FG students performed significantly better in the class, t(787) = 2.78, p <. 01, β = 0.13, attained higher post-intervention GPAs, t(780) = 3.11, p < .01, β = 0.15, and were less concerned about their background t(784) = 2.49, p = .01, β = −0.11, when they affirmed their independence in the VA condition. Conversely, there were no significant differences between FG students who did not affirm their independence in VA and FG students in the control condition, p > .35.

Figure 4.

Study 1B: Decomposition of moderated mediation effects comparing students in the values affirmation (VA) condition at different levels of the mediator - those who wrote about independence (VA, Independence) and those who did not write about independence (VA, No Independence) - to students in the control condition on mean biology course grade (Panel A), post-intervention GPA (Panel B), and concern about background (Panel C). Error bars represent +/−1 standard error.

These results are consistent with the moderated mediation analyses reported earlier. We found consistent results indicating that the positive effect of VA for FG students was mediated through writing about independence and moderated by generational status: FG students (but not CG students) benefited from writing about their personal independence across three measures (course grade, post-intervention GPA, and concern about background). In other words, the intervention promoted writing about independence for all students (i.e., all students wrote more about independence in the VA condition), on average, but this writing was particularly powerful for FG students.

Although these results are consistent with our hypotheses, for a more complete understanding of this moderated mediation, it is important to consider whether other factors were associated with writing about independence for FG students. For example, a previously unexplored third variable might predict both writing about independence and academic performance for FG students (Imai & Yamamoto, 2013)9. It is therefore important to examine whether there were differences on baseline variables for FG students who chose to write about independence compared to those who did not, and then test whether any such differences might account for the moderated mediation effects documented here.

Exploring possible confounding variables

We examined several baseline measures for differences between FG students who wrote about independence (and benefited most from the intervention) and those who did not write about independence. An effect of independent writing on a baseline variable could indicate that it was a pre-existing individual difference and not the effects of the intervention that caused some FG students to write more about independence, perform better, and feel less concern about background.

We tested a regression model that included the main effects of condition (Control vs. VA), generational status (FG students vs. CG students), and independence code (wrote about independence vs. never wrote about independence) as well as all two-way interactions on the following baseline measures: percentage of students who receive free or reduced lunch at each student’s high school (a proxy for poverty at both the school and neighborhood level), a measure of pre-intervention performance (prior GPA), a standardized test score (ACT), number of total credits taken in the previous semester, confidence about performance, baseline concern about background, and age. Missing data was addressed using multiple imputation. Due to the low level of independence affirmed in the control condition, the 3-way interaction between condition, generational status, and independence was not included, given collinearity with the generational status × independence interaction term. For these analyses, it is critical to identify any effects that include independence as a significant predictor as this could indicate baseline differences between students who did and did not write about independence and introduce a potential confound for the moderated mediation findings.

The results of the baseline analyses are displayed in Table 6. The results show that there were no failures of randomization on baseline measures (i.e. no condition main effects or interactions with condition on any baseline measures). They also indicate that FG students differed from CG students on a number of variables at baseline. Specifically, FG students attended high schools with a higher percentage of students receiving financial assistance for school meals (FG students: M = 31%, SD = 16%; CG students: M = 22% SD = 15%), obtained, on average, lower ACT scores (FG students: M = 27.58, SD = 3.31; CG students: M = 28.60, SD = 2.61), had lower prior GPAs (FG students: M = 3.10, SD = 0.53; CG students: M = 3.23, SD = 0.50), and were older (FG students: M = 19.70 years old, SD = 2.08; CG students: M = 19.16 years old, SD = 0.82) than their CG peers.

Table 6.

Study 1B: Analysis of Baseline Variables

| Regression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||

| β | t (df) | p | β | t (df) | p | |

| % Free/Reduced Lunch | ||||||

| Generational Status | 0.22 | 6.41 (794) | .000 | 0.20 | 4.39 (791) | .000 |

| Condition | 0.01 | 0.24 (794) | .811 | 0.12 | 0.13 (791) | .898 |

| Gen Status × Condition | −0.03 | 0.66 (794) | .509 | −0.03 | 0.62 (791) | .951 |

| Independence | −0.40 | 0.42 (791) | .676 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | −0.05 | 0.89 (791) | .376 | |||

| Condition × Independence | −0.28 | −0.26 (791) | .793 | |||

| ACT | ||||||

| Generational Status | −0.15 | 4.12 (794) | .000 | −0.05 | 1.09 (791) | .275 |

| Condition | 0.00 | 0.03 (794) | .976 | −0.13 | 1.05 (791) | .295 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.00 | 0.08 (794) | .939 | 0.10 | 1.87 (791) | .062 |

| Independence | 0.22 | 2.23 (791) | .026 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | 0.20 | 3.47 (791) | .001 | |||

| Condition × Independence | −0.01 | −0.10 (791) | .918 | |||

| Prior GPA | ||||||

| Generational Status | −0.11 | 3.01 (794) | .003 | −0.06 | 1.35 (791) | .178 |

| Condition | −0.01 | 0.18 (794) | .855 | −0.09 | 0.72 (791) | .472 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.01 | 0.30 (794) | .767 | −0.03 | 0.57 (791) | .568 |

| Independence | 0.10 | 1.02 (791) | .307 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | 0.09 | 1.52 (791) | .129 | |||

| Condition × Independence | −0.04 | 0.36 (791) | .716 | |||

| Prior Credits Taken | ||||||

| Generational Status | −0.04 | 1.09 (794) | .275 | −0.06 | 1.35 (791) | .176 |

| Condition | 0.02 | 0.39 (794) | .700 | 0.12 | 0.97 (791) | .333 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.01 | 0.21 (794) | .834 | 0.03 | 0.52 (791) | .600 |

| Independence | −0.07 | 0.72 (791) | .472 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | −0.04 | 0.71 (791) | .477 | |||

| Condition × Independence | 0.10 | 0.93 (791) | .353 | |||

| Confidence about Performance | ||||||

| Generational Status | −0.01 | 0.21 (794) | .833 | 0.02 | 0.36 (791) | .720 |

| Condition | −0.02 | 0.50 (794) | .619 | 0.06 | 0.45 (791) | .650 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.02 | 0.50 (794) | .619 | 0.00 | 0.01 (791) | .993 |

| Independence | −0.43 | 0.43 (791) | .665 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | 0.05 | 0.88 (791) | .381 | |||

| Condition × Independence | 0.09 | 0.89 (791) | .386 | |||

| Concern about Background | ||||||

| Generational Status | −0.01 | 0.37 (794) | .384 | −0.04 | 0.97 (791) | .333 |

| Condition | 0.03 | 0.72 (794) | .325 | −0.01 | 0.05 (791) | .959 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.00 | 0.03 (794) | .315 | 0.03 | 0.67 (791) | .500 |

| Independence | −0.02 | 0.17 (791) | .866 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | −0.07 | 1.18 (791) | .237 | |||

| Condition × Independence | −0.08 | 0.73 (791) | .466 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Generational Status | 0.18 | 5.16 (794) | .000 | 0.19 | 4.17 (791) | .000 |

| Condition | 0.00 | 0.06 (794) | .952 | 0.06 | 0.51 (791) | .611 |

| Gen Status × Condition | 0.00 | 0.06 (794) | .952 | −0.01 | 0.17 (791) | .865 |

| Independence | −0.06 | 0.58 (791) | .560 | |||

| Gen Status × Independence | 0.02 | 0.34 (791) | .738 | |||

| Condition × Independence | 0.05 | 0.48 (791) | .633 | |||

Note. Step 1 tests the effects of generational status, condition, and the Generational Status × Condition effect. Step 2 adds Independence, and two 2-way interactions (Generational Status × Independence and Condition × Independence).

When we tested for differences as a function of Independence code, however, we found effects only for ACT scores. Specifically, there was a significant main effect of independence code such that students who wrote about their independence had higher ACT scores (M = 28.85, SD = 2.49) than students who did not write about their independence (M = 28.30, SD = 2.85), t(791) = 2.23, p = .03, β = 0.22. Furthermore, this main effect was qualified by a generational status×independence code interaction revealing that FG students who wrote about independence (M = 29.10, SD = 2.70) had higher ACT scores than FG students who did not write about independence (M = 27.15, SD = 3.35), t(791) = 3.47, p = .001, β = 0.20, whereas the difference was much smaller for CG students: M = 28.77, SD = 2.43, for those who wrote about independence, and M = 28.57, SD = 2.65 for those who did not. These effects, observed across condition, were also significant when analyzed within the VA condition (see on-line supplemental materials for these analyses).

These effects suggest that FG students who wrote about independence in VA conditions also had stronger academic preparation in high school (as evidenced by higher ACT scores). It is possible that this stronger academic background might account both for FG students’ more independent writing and their improved performance and/or decreased concern about background. It is therefore important to test whether the effects remain significant when ACT is included in the model. We therefore tested whether differences in ACT accounted for the moderated mediation reported earlier by including ACT in our models. Specifically, we included the main effect of ACT, and three two-way interactions (ACT × Generational Status, ACT × Condition, and ACT × Independence Code). Controlling for these variables did not change the pattern of results or significance of the conditional indirect effects of independence on outcome variables for FG students (95% CI: = [0.008, 0.137] for course grade; 95% CI: = [0.003, 0.129] for post-intervention GPA; 95% CI: = [−0.200, −0.007] for concern about background); moreover, the indices of moderated mediation remained significant (95% CI: = [0.005, 0.146] for course grade; 95% CI: = [0.022, 0.171] for post-intervention GPA; 95% CI: = [−0.238, −0.013] for concern about background). In other words, even with ACT controlled, the positive effect of independent writing for FG students remained significant.10 The fact that the indicators of moderated mediation remained significant after controlling for ACT suggests that the mediating effect of writing about independence was not an artifact of higher ACT scores. In other words, although FG students with higher ACT scores were more likely to write about independence, our results indicate that this ACT difference does not account for the beneficial effect of affirming independence for FG students. These analyses bolster our conclusion that writing about independence was a critical mediator of intervention effects for FG students.

Discussion

The results of Study 1B support our hypothesis that writing about independence would mediate the positive effects of VA on course grade, post-intervention GPA, and concern about background for FG students. We found that students assigned to the VA condition wrote more about both independence and interdependence in their essays than students assigned to the control condition, with many students affirming both their independence and interdependence in the same essay (indicating that these two types of values are not mutually exclusive). However, only independent writing was associated with improved academic performance for FG students, in both the short and the long term, as well as less concern about their background.

Although we have tested independent writing as a mediator of treatment effects for FG students, it is important to consider whether independence could be a moderator rather than a mediator. For example, we conceptualized independent writing as a mediator, and demonstrated that the VA manipulation induced students to write more about their independent values, which in turn benefited FG students. Alternatively, one could argue that independent writing is a moderator such that the VA intervention induced all students to write about their values, and the FG students who chose to write about independence (perhaps based on some unobserved individual difference) benefited the most. Although this logic is plausible, we considered writing about independence to be a mediator rather than a moderator for several reasons.

Our analyses indicate that VA increased both independent and interdependent writing but that only independent writing accounted for the positive effect of VA for FG students. This way of thinking about the content of VA writing as a mechanistic outcome of VA rather than a moderator is consistent with prior research that documented how writing about social belonging mediated VA effects for African American middle-schoolers (Shnabel et al., 2013). However, we recognize that this argument is not as clear-cut as in other research where mediators are measured later in time (Smith, 2012). Ultimately, the distinction between independent writing as a mediator or moderator may rest on whether writing independently is considered to be the intervention itself or an outcome of the intervention (which instructs student to first think about important values and then write about them), and this may simply be a question of semantics. We view the content of VA essays as evidence of the psychological processes occurring as the immediate result of the intervention, and therefore consider independent writing to be an outcome and mediator of the intervention.

To strengthen this interpretation, we conducted a number of analyses to rule out potential confounds (e.g., exploration of possible confounding variables at baseline) that might have significantly predicted both the mediator (writing about independence) and outcome variables (grades, concern about background), but stronger evidence for mediation would come from a study in which the mediator was directly manipulated (Bullock, Green, & Ha, 2010; Smith, 2012). Thus, we sought to test the effects of inducing independent writing in an experimental study in Study 2. Although one can never fully rule out that an unmeasured variable accounts for the observed results (or signals that independent writing moderated our effects), we believe that our analyses support the conceptualization of independent writing as a mediator. Furthermore, we conducted linguistic analyses (Study 1C) and a controlled laboratory study (Study 2) in order to better understand the role of independent writing in VA essays.

Study 1C: Linguistic Analysis of VA Essays

A principal finding of Study 1B was that independent writing accounted for the beneficial effects of the VA intervention for FG students. However, the measures of independent and interdependent writing were three-level measures based on holistic coding. In order to examine the content of students’ writing in greater detail, as well as how they were expressing themselves when they reflected on important personal values, we conducted a text analysis exclusively within the VA condition. We used Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker, Francis, & Booth, 2001) to examine if the positive effect of writing about independence for FG students observed across conditions in Study 1B could be replicated utilizing a more detailed content analysis that examined the independent and interdependent linguistic content of VA essays.

LIWC coding

Given that previous analyses revealed that FG and CG students did not select different values in the VA condition (Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al., 2014), we used a text analysis program to focus on the content of students’ essay in greater detail and examined if FG and CG students wrote about their values differently or if certain kinds of writing were particularly beneficial for FG students. Thus, we conducted a content analysis that enabled us to examine, with greater nuance, the extent to which students wrote about independence and interdependence. We developed text analytic dictionaries starting with Madera, Hebl, & Martin’s (2009) Agentic and Communal dictionaries and then added more terms, based on existing literature on independent and interdependent individual orientations and writing styles (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Stephens, Fryberg et al., 2012) to further guide the dictionary construction process. Words included in the independent dictionary included themes of individual interest and achievement, self-discovery, uniqueness, and leadership. Words in the interdependent dictionary reflected interpersonal themes of belonging, family, support, and empathy (see on-line supplemental materials for full independent and interdependent dictionaries).

Results

We analyzed all of the VA essays from the Harackiewicz, Cannning, et al. (2014) study with LIWC, which yielded scores for the percentage of independent and interdependent words used in each essay. Because students wrote two VA essays over the course of the semester, we averaged the independent scores to create a single independent words score and averaged the interdependent scores to create an interdependent words score. On average, students wrote 135.39 words in their essays with 4% (SD = 2%) independent words and 7% (SD = 3%) interdependent words. There was a small negative correlation between independent and interdependent words, r(402) = 2212;.19, p < .01, but the magnitude of the correlation indicates little relationship between the use of independent and interdependent words. The use of independent and interdependent words did not vary by generational status (p > .89). Table 7 shows the correlations of interdependent and independent words with the holistic coding measures of interdependent and independent themes used in Study 1B. We also examined the correlations of the interdependent and independent linguistic word scores with the values that students selected in the VA condition and found that students used the greatest proportion of independent words in their VA essays when they selected the values: independence, learning and gaining knowledge and curiosity. Students used the greatest proportion of interdependent words in their essays when they selected the values: relationships with friends and family, belonging to a social group, and spiritual and religious values.

Table 7.

Study 1C: Percent of Students Who Selected Each Value and Correlations with LIWC Word Counts Within the Values Affirmation Condition

| Selected Value | % Who Selected Value Once or Twice |

Independent Words |

Interdependent Words |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independence | 32% | .369** | −.200** |

| Learning and Gaining Knowledge | 65% | .301** | −.120* |

| Curiosity | 10% | .151** | −.213** |

| Relationships with Friends and Family | 89% | −.252** | .531** |

| Belonging to a Social Group | 9% | −.124* | .132** |

| Spiritual and Religious Values | 21% | −.223** | .119* |

| Being Good at Art | 1% | −.037 | .064 |

| Government and Politics | 1% | −.053 | .014 |

| Athletic Ability | 9% | .078 | −.142** |

| Career | 37% | −.047 | .043 |

| Creativity | 16% | .040 | −.220** |

| Music | 10% | −.018 | −.121* |

| Nature and the Environment | 8% | −.084 | .020 |

| School Spirit | 0% | .061 | .012 |

| Sense of Humor | 37% | −.168** | −.133** |

| Social Networking and/or Gaming | 1% | −.051 | −.013 |

| Holistic Coding and Word Usage | % Who Wrote about Themes Once or Twice |

||

| Independent Themes | 36% | .458** | −.180** |

| Interdependent Themes | 92% | −.268** | .636** |

| Independent Words | -- | 1 | −.193** |

| Interdependent Words | -- | −.193** | 1 |

Note. The first 8 values listed were used in our directed conditions in Study 2.

p <.05,

p < .01.

LIWC variables as predictors of course performance