Abstract

PURPOSE

The provision of breastfeeding support in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) may assist a mother to develop a milk supply for the NICU infant. Human milk offers unique benefits and its provision unique challenges in this highly vulnerable population. The provision of breastfeeding support in this setting has not been studied in a large, multihospital study. We describe the frequency of breastfeeding support provided by nurses and examined relationships between NICU nursing characteristics, the availability of a lactation consultant (LC), and breastfeeding support.

SUBJECTS AND DESIGN

This was a secondary analysis of 2008 survey data from 6060 registered nurses in 104 NICUs nationally. Nurse managers provided data on LCs. These NICUs were members of the Vermont Oxford Network, a voluntary quality and safety collaborative.

METHODS

Nurses reported on the infants (n = 15,233) they cared for on their last shift, including whether breastfeeding support was provided to parents. Breastfeeding support was measured as a percentage of infants on the unit. The denominator was all infants assigned to all nurse respondents on that NICU. The numerator was the number of infants that nurses reported providing breastfeeding support. Nurses also completed the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI), a nationally endorsed nursing care performance measure. The NICU nursing characteristics include the percentages of nurses with a BSN or higher degree and with 5 or more years of NICU experience, an acuity-adjusted staffing ratio, and PES-NWI subscale scores. Lactation consultant availability was measured as any/none and in full-time equivalent positions per 10 beds.

RESULTS

The parents of 14% of infants received breastfeeding support from the nurse. Half of the NICUs had an LC. Multiple regression analysis showed a significant relationship between 2 measures of nurse staffing and breastfeeding support. A 1 SD higher acuity-adjusted staffing ratio was associated with a 2% increase in infants provided breastfeeding support. A 1 SD higher score on the Staffing and Resource Adequacy PES-NWI subscale was associated with a 2% increase in infants provided breastfeeding support. There was no association between other NICU nursing characteristics or LCs and nurse-provided breastfeeding support.

CONCLUSIONS

Nurses provide breastfeeding support around the clock. On a typical shift, about 1 in 7 NICU infants receives breastfeeding support from a nurse. Lactation consultants are not routinely available in NICUs, and their presence does not influence whether nurses provide breastfeeding support. Better nurse staffing fosters nurse provision of breastfeeding support.

Keywords: breastfeeding support, NICU, nurse work environment, Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index

National authorities, including the surgeon general, have endorsed human milk as the highest form of nutrition and the standard of care for all newborns in the United States.1–6 Of all hospital-born infants, those admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are the most vulnerable and in need of the superior nutritional and protective properties of human milk.7,8 The clinical uncertainty of vulnerable infants is managed by nurses by providing high-tech and time-urgent care.9 At the same time, nurses provide constant surveillance of infant patients and are ideally positioned to facilitate maternal initiation of a milk supply regardless the infant’s ability to feed orally.10–12 Little is known about how often nurses provide breastfeeding support and related features of the nurse work environment in the US NICUs. Nurses’ qualifications (education and years of experience in the NICU), nurse staffing levels, and professional support may be system-level factors that influence whether nurses help mothers in the NICU establish and maintain a milk supply.

BACKGROUND

Breastfeeding support by healthcare professionals has been described as “counseling or behavioral intentions to improve breastfeeding outcomes.” 13 In 1993, Meier et al identified a 5-category model of interventions as: (1) collection of expressed breast milk, (2) gavage feeding of expressed mothers’ milk, (3) in-hospital breastfeeding sessions, (4) postdis-charge breastfeeding management, and (5) additional hospital consultation, and they found that the model was effective in preventing breastfeeding failure in the NICU.14

Since 2000, 11 studies have explored nurse provision of breastfeeding support in the NICU using various designs and methods, including qualitative description, descriptive analysis of surveys, pre- and postlactation intervention analysis, and educational evaluation of programs for both nurses and mothers.9,15–24 These studies describe or measure technical, informational, or emotional activities associated with breastfeeding support.9,15–22 Notably, a clear definition of “breastfeeding support” has not been established, and the use of the term varies widely in the literature.9,15–22,25 These studies have shown that nurses have positive attitudes about and varied knowledge of breastfeeding. Improving nurses’ knowledge about breastfeeding influences actual supportive behaviors and provides more consistent messages to mothers during infant admission.9 Modern NICUs see the role of parents, especially mothers as partners in the care of their infants.26 The constant presence of the NICU nurse at the bedside ideally positions nurses to guide a mother’s first opportunity to care for her infant through breastfeeding.11,12 Evidence has suggested that breastfeeding mothers require more of a nurse’s time, which may affect the nature and consistency of breastfeeding support.27

The NICU breastfeeding policies, staffing, organization, and timely maternal access to nurses seem to influence the provision breastfeeding support.7,8,11,14,20,28 However, there is limited literature that describes the contextual factors of the NICU work environment. Nurse staffing is the most common nursing characteristic that has been studied related to the safety and quality of patient care, but no evidence exists regarding how nurse staffing relates to breastfeeding support in the NICU.29–32 Higher nurse-to-patient staffing ratios in US NICUs have been associated with reduced mortality rates and fewer infections.33,34 Inadequate staffing and resources contributed to rationing of nursing care by NICU nurses because of lack of time in a study of 9 Quebec NICUs.35 Parental support and teaching were among the most frequently rationed nursing care activities, suggesting that breastfeeding support would be undermined with inadequate staffing.35

Another organizational focus of outcome studies is the nursing practice environment.29,36 Two studies have focused on how the nursing practice environment relates to NICU infant outcomes.35,37 Both used a National Quality Forum measure of nurses’ practice environments, the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI).38 The National Quality Forum is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, public service organization that endorses standardized healthcare performance measures also known as quality measures.39 Higher scores on the PES-NWI were associated with higher nurse-rated quality of care.35 In addition, hospitals, which were recognized for meeting standards of nursing excellence (“Magnet” hospitals), were found to have significantly better very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infant outcomes such as lower–risk-adjusted rates of 7-day mortality, nosocomial infection, and severe intraventricular hemorrhage.40 However, few hospitals with an NICU (20%) have achieved this recognition.40 This study theorized that better NICU nursing characteristics, as measured by nurses’ qualifications (education and years of experience), staffing level, and the nursing practice environment would result in improved breastfeeding support in the NICU, where the likely causal path was through better nursing care.

The potential for a lactation consultant (LC) in the NICU to complement or substitute for a nurse in supporting mothers to establish and maintain a milk supply has not been studied.41 A dedicated LC in the NICU has been demonstrated to increase the proportion of NICU infants ever given their own mother’s milk, from 31% to 47% (P = .02). 21 Breastfeeding initiation rates in the NICU before discharge are 1.3 times higher for mothers in hospitals with LC services. 42 Lactation consultant availability across NICUs is not as well described in the literature; however, LCs dedicated to the NICU have been shown to improve both initiation and duration rates of breastfeeding in infants who have experienced an NICU stay.18

No study has measured how often nurses provide breastfeeding support in a large, multihospital sample or linked contextual factors in the NICU to breastfeeding support. This study addresses the gap in knowledge associated with the nursing practice environment, nurses’ qualifications, and staffing with breastfeeding support in the NICU.

PURPOSE

The purposes of this study were to measure the frequency of the provision of breastfeeding support by nurses in the NICU, the availability of LCs in NICUs, and to examine whether NICU nursing characteristics and LC availability were associated with nurse provision of breastfeeding support. The hypotheses tested that breastfeeding support would be improved with better nurse staffing, higher practice environment scores, better nurse qualifications, and access to lactation resources.

METHODS

We conducted a secondary analysis of nurse survey data, including questions about nurses’ qualifications, practice environments, and details about the last shift worked, including infant assignments and whether breastfeeding support was provided to parents. The survey data originated from the parent study, “Acuity-adjusted staffing, nurse practice environments and NICU outcomes” (Dr Lake, the principal investigator), funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative Program. The nurse survey was conducted in March 2008 in 104 NICUs nationally. All NICUs were members of the Vermont Oxford Network (VON), a voluntary collaborative dedicated to the quality and safety of care for newborns and their families. NICUs were recruited from all US VON NICUs. In 2008, the US VON contained 578 hospitals representing approximately 65% of NICUs and 80% of all VLBW infants born in the United States.40 The institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania.

Selection and Description of Participants

A sample of 104 NICUs nationally participated in the parent study.37 The sample represented 18% of the VON members in 2008. These NICUs were broadly representative of all US VON NICUs. When compared with the VON, the sample had disproportionately more not-for-profit teaching and children’s hospitals. One-third of the study sample had Magnet recognition, compared with about a quarter of the VON. The VON classifies NICUs into the following 3 levels: levels A (restriction to minor ventilation, no surgery), B (major surgery), and C (cardiac surgery and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).43 These correspond to high level II and level III units in the American Academy of Pediatrics classification.44

Data for the parent study were collected by Web survey of all registered nurses who worked at least 16 hours per week and had been employed at least 3 months. The response rate was 77% (n = 6060 nurses reported about the care of 15 233 infants). The majority of nurse survey respondents (69%) worked their last shift on a weekday. In addition, nurse managers provided data on available NICU resources, including the presence of LCs and the number of beds. It is unknown whether LCs in the study were internationally board certified as this was not queried of the nurse manager.

Measures and Instruments

Breastfeeding support was measured by the response “breastfeeding support” to the question “Please indicate which of the following factors or activities required your time in caring for this infant’s family” on the last shift you worked. Nurses could report up to 8 activities, such as “routine bedside teaching and communicating with families,” “parents have special language or cultural needs,” and “breastfeeding support.” The term breastfeeding support was not defined in the survey and was, therefore, left open to the interpretation of the individual nurse respondent. Breastfeeding support was measured as a percentage of infants at the NICU level. All infants were considered eligible for breastfeeding support because the infants’ breastfeeding status was not known. The denominator was all infants who were assigned to all nurse respondents in that NICU. The numerator was the number of infants that nurses reported providing breastfeeding support to the parents.

The acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio was measured as the observed-to-expected ratio on the basis of the acuity mix of the infants. This ratio was determined by the parent study, where researchers in collaboration with the National Association of Neonatal Nurses developed acuity definitions to classify infants into 5 categories from lowest to highest acuity.37 The observed nurse-to-patient ratio for the unit was computed as the mean nurse-to-patient ratio for nurses in the unit. The expected ratio for the unit was computed on the basis of the number of infants in each acuity level. The observed-to-expected staffing ratio for each NICU was computed as the observed ratio divided by the expected ratio for the unit.

The PES-NWI was used to measure the degree to which certain aspects of a professional practice environment, including staffing, were present in the nurse’s current job.38,45 Multiple studies have demonstrated the predictive and discriminant validity of this 31-item, 4-point, Likert-type instrument.29,36,45,46 The survey responses were strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree. The PES-NWI items are categorized into 5 subscales that measure the following practice environment domains: nurse participation in hospital affairs, nursing foundations for quality of care, nurse manager ability, leadership and support of nurses, staffing and resource adequacy, and collegial nurse-physician relations. A score of 2.5 is the midpoint between agree and disagree, and a score of 3 or greater indicates agreement that the element is present in the job.38 The average of the subscale items was computed.

Lactation consultant availability was measured in 2 ways. A binary variable was created to indicate if the unit had an LC available on any shift. Lactation consultant availability in full-time equivalent (FTE) per 10 patient beds was calculated from nurse manager reports, where whole-shift availability was considered 1.0 FTE and part-shift availability was considered 0.5 FTE. Overall FTEs were not used because NICUs vary in the number of beds. Fulltime equivalent per bed is hard to comprehend because the numbers are quite small. An easy metric is “per 10 beds.”

NICU nurse qualifications entailed the percentages of nurses with a BSN or higher degree and with 5 or more years of NICU experience. NICU-level measures were constructed for all variables. Missing data from nurses’ responses to PES-NWI items were less than 1%. Missing data on breastfeeding support were minimal because the survey included a verification series in which respondents verified the data they had entered about their infant assignment and activities with parents.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the hospital sample and the independent and dependent variables. Bivariate relationships were assessed between the independent variables—nurse characteristics, nurse staffing, nurse practice environment subscales, and LC availability—and the dependent variable—breastfeeding support.

Independent variables that correlated with the dependent variable at P < .05 were analyzed in a linear regression model. The dependent variable was the fraction of infants that received breastfeeding support in each NICU. Continuous variables such as the acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio and practice environment measures were standardized for ease of interpretation. Two highly correlated and conceptually similar measures, the PES-NWI staffing and resource adequacy subscale and the acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio (r = 0.54; P < .01), were modeled separately to explore their distinct associations with breastfeeding support. The statistical significance level was P < .05 for a 2-tailed test. Analyses were conducted using Stata Version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).47

RESULTS

More than half (57%) of the sample NICUs provided mid-level care (level B). Compared with all US VON NICUs, the sample had more level C and fewer level A NICUs. The sample contained larger units (mean = 41 vs 22 beds) with an average staff size of 75 full-time registered nurses (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Sample Characteristics (N=104)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| NICU levela | ||

| A | 15 | 14 |

| B | 59 | 57 |

| C | 30 | 29 |

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Number of beds on a unit | 41 (20) | 13–118 |

| Number of nurses on a unit | 75 (42) | 20–204 |

Level refers to level of clinical care: A, minor ventilation only; B, minor surgery; C, cardiac surgery and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

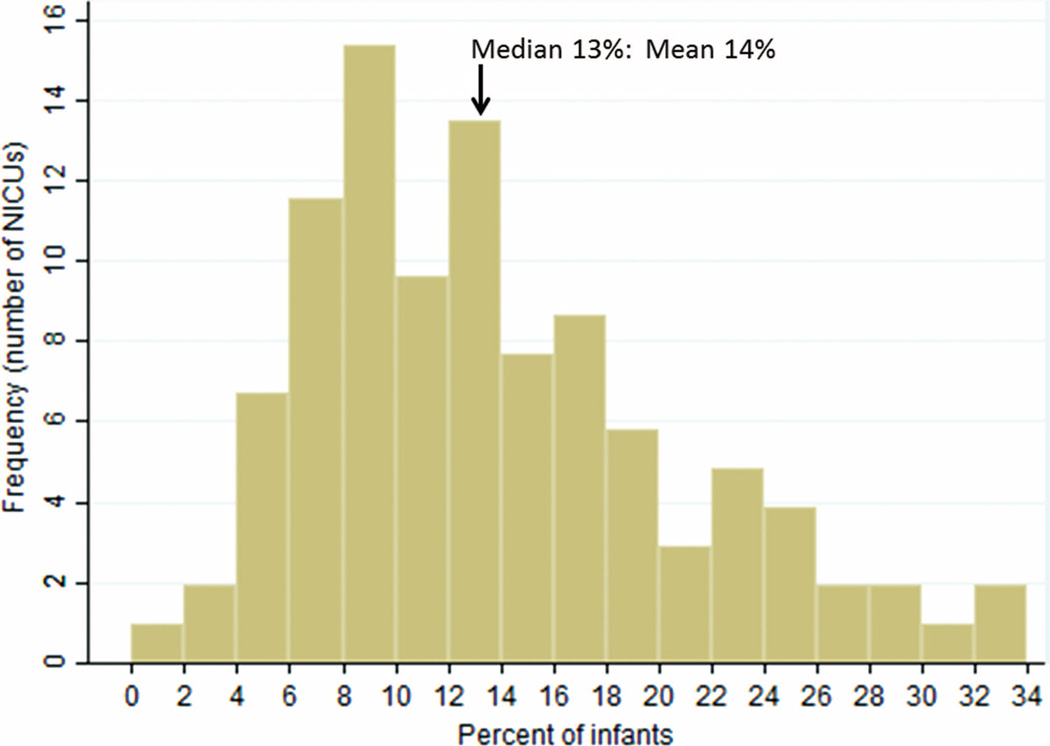

Nurses reported providing breastfeeding support for 14% of the infants they were assigned (n = 2004) (Figure 1). The distribution of breastfeeding support was right skewed. The largest group of NICUs (modal frequency, n = 16) provided breastfeeding support to 8% to 10% of infants. Notably, on 11 units, nurses reported that more than 24% of infants received breastfeeding support. Breastfeeding support was provided on every unit. The percentage of infants who received breastfeeding support was similar across shifts: 14% on weekdays, 13% on weeknights, and 18% on weekends.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of infants with nurse-reported breastfeeding support. Abbreviation: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Approximately half of the nurses on the typical unit (55%) possessed a baccalaureate or higher degree in nursing (Table 2). On a typical unit, 61% of the nurses had worked there for 5 or more years. The average NICU nurse cared for 2 infants (mean nurse-to-patient ratio = 0.46). The overall observed-to-expected staffing ratio was 1.0 by definition. The minimum was 0.64 (or two-thirds) of the expected level of staffing, given the acuity mix of infants. Therefore, on the unit with the minimum staffing level, two-thirds of a nurse cared for 2 infants. Conversely, on the unit with the maximum staffing level, 1.5 nurses cared for 2 infants.

TABLE 2.

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Nurse Qualifications, Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) Subscales, Acuity-Adjusted Nurse Staffing Ratio, Lactation Consultant Availability, and Association With Breastfeeding Support (N = 104)

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | Pearson Correlation, r (P) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse qualifications or characteristics | ||||

| Nurses with BSN or higher degree, % | 55 (15) | 23 | 97 | −0.09 (.39) |

| Nurses with 5 or more y NICU experience, % | 61 (17) | 0 | 94 | 0.13 (.19) |

| PES-NWI subscales | ||||

| Nurse participation in hospital affairs | 2.96 (0.28) | 2.11 | 3.95 | 0.14 (.14) |

| Nursing foundations for quality of care | 3.23 (0.20) | 2.72 | 3.97 | 0.19 (.06) |

| Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support | 2.94 (0.39) | 1.91 | 3.97 | 0.22 (.02) |

| Staffing and resource adequacy | 2.97 (0.38) | 1.82 | 3.96 | 0.30 (<.01) |

| Collegial nurse-physician relations | 3.19 (0.32) | 2.01 | 3.97 | 0.09 (.37) |

| Acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio | 0.99 (0.15) | 0.64 | 1.50 | 0.22 (.03) |

| Lactation consultant availability | ||||

| FTE per 10 beds | 0.21 (53) | 0 | 0.50 | 0.07 (.48) |

| Any, % | 51 (49) | … | … | 0.17 (.08) |

Abbreviations: BSN, bachelor’s of science of nursing; FTE, full-time equivalent.

NICU practice environments were highly rated in the sample, with average PES-NWI composite scores more than 3.0 (mean = 3.06) and a range from 2.42 to 3.97.

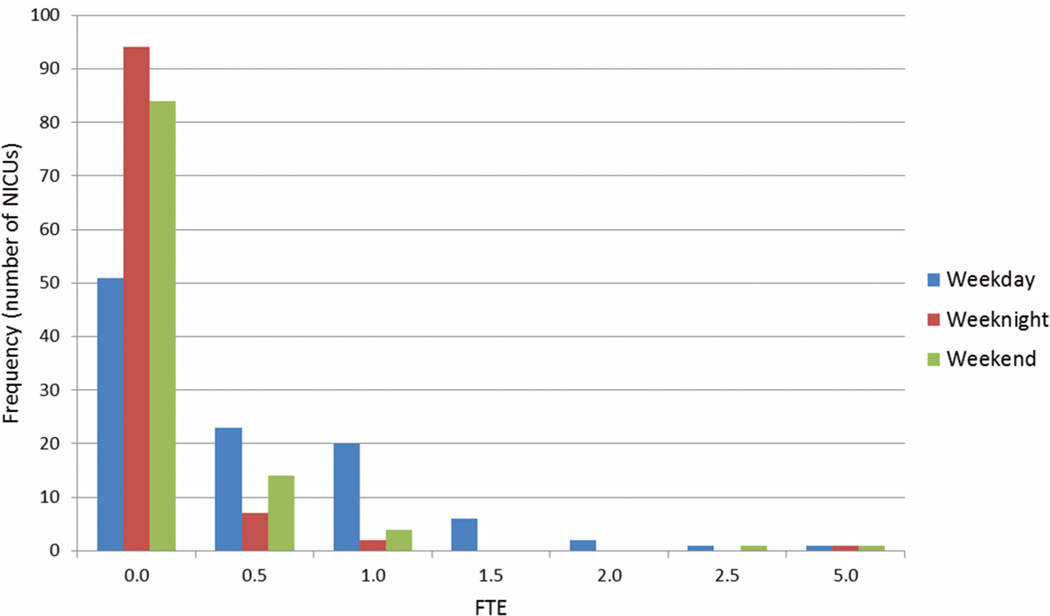

Half of the sample NICUs had no LC available on any shift (Figure 2 and Table 2). Among units that had LCs, all of them had LCs on the weekday shift, 38% had them on weekends, and the fewest (19%) had them on weeknights. Most NICUs with LCs had 0.5 or 1.0 FTE on weekdays. On average, units staffed 0.21 LCs per 10 beds (range, 0-0.50).

FIGURE 2.

Lactation consultant availability in the neonatal intensive care unit. Abbreviations: FTE, full-time equivalent; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

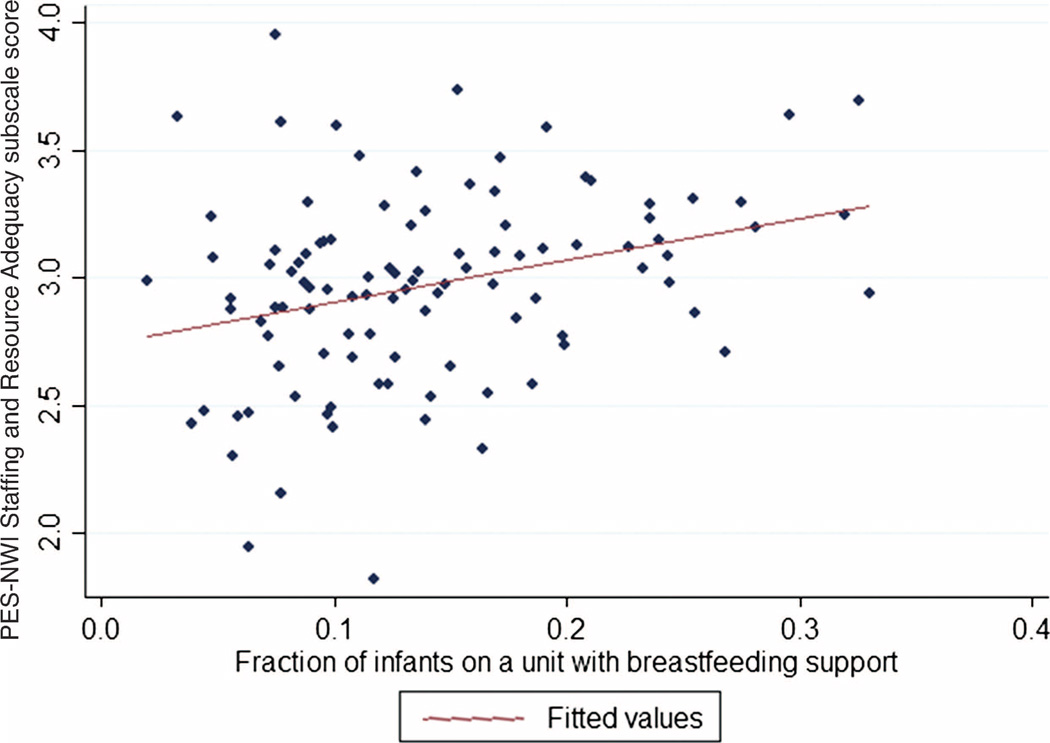

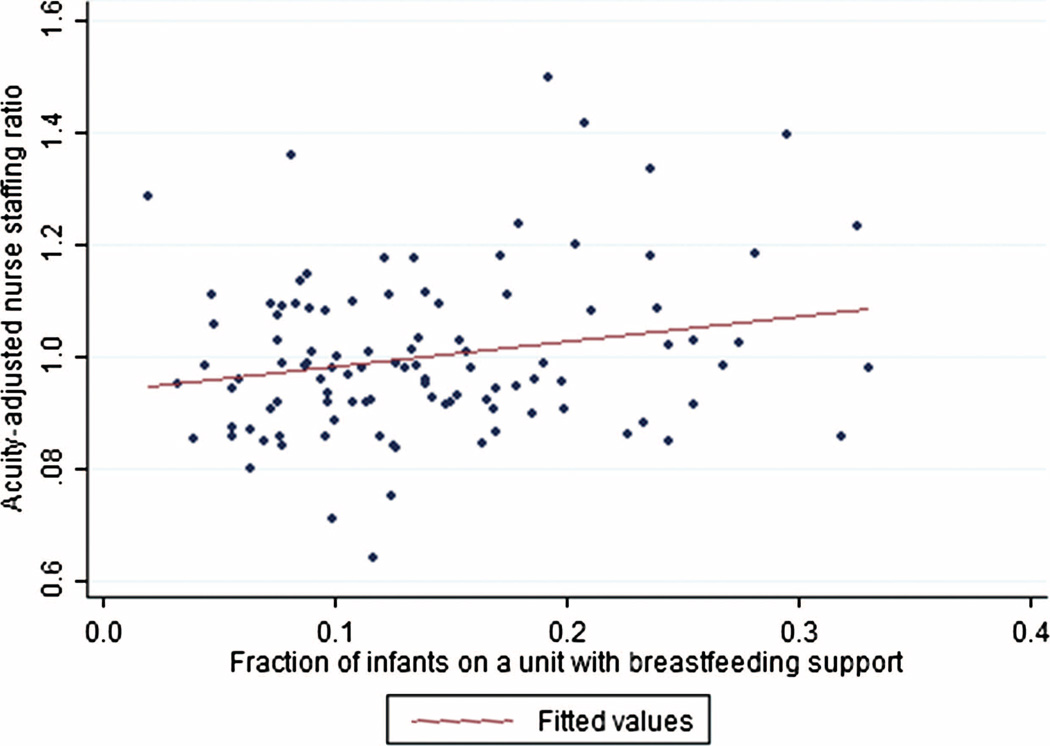

Staffing was highly correlated with breastfeeding support both as an individual subscale of the PES-NWI (r = 0.30; P < .01) and as the acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio (r = 0.22; P < .03) (Table 2). These modest positive correlations are shown by the upward sloping line on each scatterplot (Figures 3 and 4). The PES-NWI subscale “nurse manager ability, leadership, and support” was also significantly correlated with breastfeeding support (r = 0.22; P < .05).

FIGURE 3.

Scatterplot of Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) staffing and resource adequacy subscale score and infants with breastfeeding support.

FIGURE 4.

Scatterplot of acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio and infants with breastfeeding support.

The 2 PES-NWI subscales that demonstrated a significant correlation with breastfeeding support were analyzed in a multiple linear regression model (Table 3). A 1 SD higher PES-NWI staffing and resource adequacy subscale score was associated with 2% higher breastfeeding support (P < .01). As noted earlier, the acuity-adjusted staffing ratio was modeled separately. A 1 SD higher acuity-adjusted staffing ratio was associated with a 2% higher percentage of infants receiving breastfeeding support (P < .01).

TABLE 3.

Associations Between Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Nursing Characteristics and Berastfeeding Suport

|

R2= 0.05 |

R2 = 0.09 |

R2 = 0.10 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P |

| Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support |

0.01 | 0.01 | .41 | ||||||

| Staffing and resource adequacy | 0.02 | 0.01 | <.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .02 | |||

| Acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio | 0.02 | 0.01 | .03 | ||||||

B represents standardized coefficient.

DISCUSSION

The NICU is a unique work environment where nurses provide clinical care that is vital to infant survival. This study provides the first evidence of the frequency of breastfeeding support and the associations between the practice environment, nurses’ qualifications, and staffing with breastfeeding support from a large national sample of NICUs.

Overall, nurses reported that they provided breastfeeding support on the last shift they worked to 14% of the infants they cared for. Nurses reported providing breastfeeding support consistently across shifts, throughout the day, and notably during the nights and weekends. The benefits of human milk have been well described; therefore, strategies to support the use of human milk and breastfeeding should be a priority.1–6 Exploration of the activities associated with breastfeeding support in the NICU as determined by nurses and mothers, such as communicating with mothers to develop an individualized feeding plan, assisting with direct breastfeeding or providing pump supplies, and evidence-based instruction, has been demonstrated to improve care and patient satisfaction (Figure 5).15–19,22

FIGURE 5.

A nurse supporting a mother preparing to breastfeed her infant by providing skin-to-skin care in the neonatal intensive care unit.

We hypothesized that more breastfeeding support would be reported in NICUs with higher staffing ratios, higher practice environment scores, higher nurse qualifications (education and years of experience as a nurse in the NICU), and access to lactation resources. Nurse qualifications were not significantly correlated with breastfeeding support, although nurses’ knowledge about breastfeeding support has been shown to improve breastfeeding initiation in the NICU in other studies.9,15,48 However, the practice environment subscales for managerial leadership and nurse staffing and resources, and the acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio, were significantly correlated and are the focus of the discussion that follows.

Breastfeeding support was significantly associated with nurse staffing. This study used regression models to examine the importance of 2 staffing variables, the PES-NWI subscale measure (staffing and resource adequacy) and the acuity-adjusted nurse-to-patient ratio, and found that both staffing variables were significantly associated with breastfeeding support (P < .01), where better staffing was associated with a higher percentage of infants receiving breastfeeding support in the NICU. National perinatal medical and nursing organizations have promulgated acuity-based staffing guidelines for US NICUs since 1983.49–51 Understaffing relative to national guidelines in NICUs is widespread and associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infection in VLBW infants. 34 Given that understaffing occurs in NICUs, our findings suggest that breastfeeding support in some units is insufficient because of understaffing.

Our findings are consistent with prior research that demonstrates intensive care units, including that the NICU have higher work environment scores than nonintensive care settings.52,53 Within these relatively favorable practice environments, however, inadequate staffing and resources on some units seem to undermine the nurses’ capacity to support breastfeeding.

This was the first study to examine the association between breastfeeding support in the NICU and 2 different measures of nurse staffing—the PES-NWI sub-scale and the acuity-adjusted nurse staffing ratio. The former is the nurses’ perception based on 4 PES-NWI items of whether there are enough staff and support services to provide quality patient care, to spend time with patients, and to discuss care problems with other nurses.38 The latter is how plentiful the staffing is given the infants’ acuity, relative to other sample NICUs. The use of 2 measures of staffing adds to the robustness of our results, showing a significant association between staffing and breastfeeding support.

This study provided the first description of LC availability in the NICU across shifts. Among the half of NICUs that staffed with LCs, LCs were available principally on weekdays. Nurses, however, reported providing breastfeeding support around the clock. In the NICU, LCs are a scare resource; therefore, nurses play a critical role in lactation support. Correlation between LC availability (any vs none) and percentage of infants who received breastfeeding support was modest, positive, and marginally significant (r = 0.17; P = .08). These findings may indicate that in NICUs where the use of human milk is valued, LCs are available and nurses are also encouraged to support breastfeeding.

Limitations and Strengths

There are several limitations to this study. The cross-sectional research design prevents causal inferences. The focus of the parent study was not breastfeeding support; therefore, the capacity to describe this nursing process measure was limited. The term “breastfeeding support” was not defined in the survey. Future research would be strengthened by providing a clear definition of breastfeeding support that encompasses the range of activities that nurses provide to support lactation, milk storage, and infant readiness to receive human milk.

A limitation of the study design was that there were no data on infant and parent needs for breastfeeding support. When nurses reported their last shift worked, the critical lactation initiation period may have already passed, and parents may have independently been putting their infants to breast or pumping without the need for nursing intervention. Our data, however, provide a reasonable measure of the “prevalence” of breastfeeding support in an NICU at any time. An alternate design would be a prospective study of breastfeeding support of infants the first 24 hours postpartum.7,28

The hospital sample does not fully represent the VON or all US hospitals with an NICU. Our sample was disproportionately composed of Magnet hospitals. The study sample had a larger proportion of level C NICUs than the overall number in the VON consortium. This suggests that our findings generalize best to NICUs (levels B and C) that serve a more complex case mix of infants. The extent of breastfeeding support reported by nurses was only 14%. However, what is unknown is how this rate of breastfeeding support compares with NICUs that are not members of the VON. As members of the VON quality consortium, the sample NICUs represent institutions where quality improvement is a priority, these units may have better lactation resources and nurses who in work environments where breastfeeding and human milk provision are valued.

Despite the limitations of secondary analysis, evidence from a large data set of more than 6000 nurses who reported about 15,000 infants they cared for in more than 100 NICUs throughout the country provided an unprecedented glimpse of breastfeeding support in the US NICUs.

Implications for Practice and Policy

On most shifts, few infants in the NICU receive breastfeeding support. The reasons for this are not known. Factors that might influence breastfeeding support by nurses are whether human milk is considered a priority by NICU caregivers and parents, whether infants are in the postpartum period where breastfeeding support is most critical, and whether nurses possess the skills and resources to provide breastfeeding support.9,15,20

The outcomes of this study demonstrate the importance of adequate staffing to the provision of breastfeeding support. Hospital administrators and NICU managers should evaluate their staffing decisions to allocate required nursing resources to provide support to the most vulnerable infants in a hospital. Staff nurses in the NICU should advocate for and take advantage of professional practice models and educational opportunities that allow them to provide breastfeeding support to families to the full extent of their education and training.54

Future Research Directions

This study represents one of few demonstrating that staffing differences are associated with nursing care provision.55–58 Establishing this link is crucial to demonstrating a causal pathway from staffing to outcomes through nursing care quality. Without this link, it could be argued that nursing system features like staffing function as proxies for unmeasured non-nursing features of hospitals that account for outcome differences.

This study was the first attempt to measure the provision of breastfeeding support in a large sample of NICUs and to examine associations between NICU nursing features and breastfeeding support by NICU nurses. An important next step is to determine whether the provision of breastfeeding support influences whether VLBW infants receive human milk.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that more infants receive breastfeeding support from nurses in NICUs with adequate nurse staffing. Nurses report providing breastfeeding support around the clock. Lactation consultants are not routinely available in NICUs, and their presence does not influence whether nurses provide breastfeeding support. NICU administrators and managers must consider how to provide adequate staffing to ensure that needed nursing care is provided to the most vulnerable infants in the hospital.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Office of Nursing Research, 2012 Student Research Pilot Grant, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative grant “Acuity-Adjusted Staffing, Nurse Practice Environments and NICU Outcomes” (Dr Lake).

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32NR007104 “Advanced Training in Nursing Outcomes Research” (Aiken, PI).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Academy of Family Physicians. [Accessed August 15, 2013];Family physicians supporting breastfeeding. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-support.html Published 2007.

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Breastfeeding Handbook for Physicians. 2nd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of Women’s Health Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses. [Accessed August 15, 2013];Breastfeeding and the role of the nurse in the promotion of breastfeeding. https://www.awhonn.org/awhonn/binary.content.do?name=Resources/Documents/pdf/5H2a_PS_Breastfeeding07.pdf Published 2007.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 15, 2013];Breastfeeding report card—United States. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2012BreastfeedingReportCard.pdf. Published 2012.

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier PP, Furman LM, Degenhardt M. Increased lactation risk for late preterm infants and mothers: evidence and management strategies to protect breastfeeding. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(6):579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spatz DL. Ten steps for promoting and protecting breastfeeding for vulnerable infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004;18(4):385–396. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cricco-Lizza R. Everyday nursing practice values in the NICU and their reflection on breastfeeding promotion. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(3):339–409. doi: 10.1177/1049732310379239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boucher CA, Brazal PM, Graham-Certosini C, Carnaghan-Sherrard K. Mothers’ breastfeeding experiences in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2011;30(1):21–28. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.30.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spatz DL. The critical role of nurses in lact ation support. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(1):499–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spatz DL. American Academy of Nursing on Policy—the surgeon general’s call to breastfeeding action-policy and practice implications for nurse. Nurs Outlook. 2011;50:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shealy KR, Li R, Benton-Davis S, Grummer-Strawn LM. The CDC Guide to Breastfeeding Intervention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Mangurten HH, Estrada E, Zimmerman B, Kopparthi R. Breastfeeding support services in the neonatal intensive-care unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1993;22(4):338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1993.tb01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernaix LW. Nurses’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions toward support of breastfeeding mothers. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(3):201–209. doi: 10.1177/089033440001600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callen J, Pinelli J, Atkinson S, Saigal S. Qualitative analysis of barriers to breastfeeding in very-low birthweight infants in the hospital and postdischarge. Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5(2):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colaizy TT, Morriss FH. Positive effect of NICU admission on breastfeeding of preterm US infants in 2000 to 2003. J Perinatol. 2008;28(7):505–510. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez KA, Meinzen-Derr J, Burke BL, et al. Evaluation of a lactation support service in a children’s hospital neonatal intensive care unit. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(3):286–292. doi: 10.1177/0890334403255344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maastrup R, Bojesen SN, Kronborg H, Hallstrom I. Breastfeeding support in neonatal intensive care: a national survey. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(3):370–379. doi: 10.1177/0890334412440846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier PP, Patel AL, Bigger HR, Rossman B, Engstrom JL. Supporting breastfeeding in the neonatal intensive care unit: Rush Mother’s Milk Club as a case study of evidence-based care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinelli J, Atkinson SA, Saigal S. Randomized trial of breastfeeding support in very low-birth-weight infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:548–553. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddell E, Marinelli K, Froman RD, Burke G. Evaluation of an educational intervention on breastfeeding for NICU nurses. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(3):293–303. doi: 10.1177/0890334403255223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernaix LW, Schmidt CA, Arrizola M, Iovinelli D, Medina-Poelinez C. Success of a lactation education program on NICU nurses’ knowledge and attitudes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(4):436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ericson J, Eriksson M, Hellstrom-Westas L, Hagberg L, Hoddinott P, Flacking R. The effectiveness of proactive telephone support provided to breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thulier D. A call for clarity in infant breast and bottle-feeding definitions for research. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(6):627–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas LM. The changing role of parents in neonatal care: a historical review. Neonatal Netw. 2008;27(2):91–100. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.27.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson AM. Maternal-newborn nurses’ experiences of inconsistent professional breastfeeding support. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartick M, Reinhold A. The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: a pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1048–1056. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheny T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Admin. 2008;38(5):223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt T. Nursing Staffing and Quality of Patient Care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shekelle PG. Nurse-patient ratios as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5):404–409. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00007. (pt 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cimiotti JP, Haas J, Saiman L, Larson EL. Impact of staffing on bloodstream infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2006;160(8):832–836. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogowski JA, Staiger D, Patrick T, Horbar J, Kenny M, Lake ET. Nurse staffing and NICU infection rates. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):444–450. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal unit. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2213–2224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kutney-Lee A, Lake ET, Aiken LH. Development of the hospital nurse surveillance capacity profile. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(2):217–228. doi: 10.1002/nur.20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lake ET, Patrick T, Rogowski J, et al. The three Es: how neonatal staff nurses’ education, experience, and environments affect infant outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(suppl):S97–S98. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;64(suppl 2):104S–122S. doi: 10.1002/nur.10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Quality Forum. Who we are: about NQF. [Accessed February 19, 2014]; http://www.qualityforum.org/who_we_are.aspx. Published 2014.

- 40.Lake ET, Staiger D, Horbar J, et al. Association between hospital recognition for nursing excellence and outcomes of very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 2012;307(16):1709–1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wambach K, Campbell SH, Gill SL, Dodgson JE, Abiona TC, Heinig MJ. Clinical lactation practice: 20 years of evidence. J Hum Lact. 2005;21(3):245–258. doi: 10.1177/0890334405279001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castrucci BC, Hoover KL, Lim S, Maus KC. Availability of lactation counseling services influences breastfeeding among infants admitted to neonatal intensive care units. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(5):410–415. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermont Oxford Network. Vermont Oxford Network Database Manual of Operations for Infants Born in 2008. Release 12.1. Burlington, VT: Vermont Oxford Network; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barfield WD, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1341–1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/587.full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friese CR, Lake ET, Aiken LH, Silber JH, Sochalski J. Hospital nurse practice environments and outcomes for surgical oncology patient. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1145–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lake ET, Friese CR. Variations in nursing practice environments: relation to staffing and hospital characteristics. Nurs Res. 2006;55:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Renfrew MJ, Craig D, Dyson L, et al. Breastfeeding promotion for infants in neonatal units: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(2):165–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 1983. Inpatient perinatal care services. [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Inpatient perinatal care services. In: Lemons J, Lockwood CJ, editors. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2007. pp. 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Association of Women’s Health Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses. Guidelines for Professional Registered Nurse Staffing for Perinatal Units. Washington, DC: Association of Women’s Health Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manojlovich M, DeCicco B. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication and patient’s outcome. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16(6):536–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmalenberg C, Kramer M. Clinical units with the healthiest work environments. Crit Care Nurs. 2008;28(3):65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voepel-Lewis T, Pechlavanidis E, Burke C, Talsma AN. Nursing surveillance moderates the relationship between staffing levels and pediatric postoperative serious adverse events: a nested case-control study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(7):905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ball JE, Murrells T, Raffert y AM, Morrow E, Griffiths P. “Care left undone” during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):116–125. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu XW, You LM, Zheng J, et al. Nurse staffing levels make a difference on patient outcomes: a multisite study in Chinese hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(3):266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalisch BJ, Doumit M, Lee KH, Zein JE. Missed nursing care, level of staffing, and job satisfaction: Lebanon versus the United States. J Nurs Admin. 2013;43(5):274–279. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31828eebaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]