Abstract

PURPOSE

Women family physicians experience challenges in maintaining work-life balance while practicing in rural communities. We sought to better understand the personal and professional strategies that enable women in rural family medicine to balance work and personal demands and achieve long-term career satisfaction.

METHODS

Women family physicians practicing in rural communities in the United States were interviewed using a semistructured format. Interviews were recorded, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using an immersion and crystallization approach, followed by detailed coding of emergent themes.

RESULTS

The 25 participants described a set of strategies that facilitated successful work-life balance. First, they used reduced or flexible work hours to help achieve balance with personal roles. Second, many had supportive relationships with spouses and partners, parents, or other members of the community, which facilitated their ability to be readily available to their patients. Third, participants maintained clear boundaries around their work lives, which helped them to have adequate time for parenting, recreation, and rest.

CONCLUSIONS

Women family physicians can build successful careers in rural communities, but supportive employers, relationships, and patient approaches provide a foundation for this success. Educators, employers, communities, and policymakers can adapt their practices to help women family physicians thrive in rural communities.

Keywords: family life, primary care access, physician workforce, rural, women in medicine, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

The United States faces a chronic, severe shortage of rural physicians, which has a negative impact on population health.1–4 Rural America is economically, socially, and environmentally diverse, yet residents of rural communities share common difficulties accessing health care, including longer distances to care, and a disproportionate shortage of women and minority physicians.5–8 A lack of women rural physicians especially limits access to care for women patients, who often prefer women clinicians and appear to complete more screening tests when seen by women.9 Rural female physicians are also more likely to attend births than male peers,10,11 an important practice characteristic as many rural areas have a shortage of obstetrics professionals.12,13 Promoting the success of women family physicians in rural communities is therefore important for community health.

Acknowledging that women are an essential component of the rural physician workforce,6 several studies have explored what factors attract women to rural practice and enable their success. Many rural physicians have had rural life experience.14,15 Previous studies have described common joys associated with rural practice, including multidimensional patient relationships,16–18 the variety and professional challenges associated with a broad scope of practice,10,18 the opportunity to serve one’s community,17–20 clinical autonomy,17 and the attractions of small town life.17,18,20 Rural women physicians who are most professionally satisfied report feeling connected with their communities18,19 and having control over their work environment.21 Interestingly, rural female physicians are more likely than their male counterparts to anticipate long-term rural careers.19

Women physicians also report noteworthy challenges, however. Compared with their urban peers, these physicians have fewer community resources, work more hours, and care for more patients.10,20,22 They tend to be dissatisfied with the amount of time spent away from their practices17 and are more likely to be balancing professional and personal obligations, including childcare, than their male counterparts.18,23,24 Compared with male peers, women rural physicians are also more likely to report professional isolation and lack of privacy.19,25

Interestingly, in survey studies such as these, the challenges and joys of rural practice are acknowledged by the same physicians. Women who are successfully practicing rural medicine have found a balance whereby the value outweighs the challenge of a profession that is both demanding and fulfilling. Understanding the personal and professional strategies that have enabled some female physicians to build successful, durable, and satisfying rural careers may inform women contemplating careers in rural medicine, as well as rural communities hoping to recruit and retain female physicians.

To that end, using a phenomenologic research design,26 we interviewed women family physicians actively engaged in rural practice, exploring the question, how do these physicians balance their professional and personal lives?

METHODS

We recruited women family physicians from across the United States, using the e-mail contact lists of rural health care organizations, listservs of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine and the American Academy of Family Physicians, newsletters, and snowball sampling. We enrolled 25 respondents who self-identified as women family physicians, active in a rural medical practice. Rural practice locations were confirmed, with rural defined as having a practice zip code corresponding to a Rural-Urban Commuting Area level of 7 or higher.27 Gift cards incentivized participation.

Interviews were completed in 2012. The interviewers included 2 medical students, a public health student, 2 family physicians, and a medical educator; all described themselves to participants as researchers. We pilot tested the script with physician colleagues to refine questions and allow interviewers to practice. Interviewers used a semistructured format, first asking scripted questions, using verbatim phrasing to ensure consistency, and then asking follow-up questions to clarify responses and explore topics in greater depth. Questions pertinent to this manuscript are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Interview Questions

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Work hours and patterns | Do you work full time or part time? About how many hours a week do you work? Does this include time on inpatient floors/ED coverage? Do you take call? Do you practice OB? Would you like your schedule to be different? What motivates you to work as hard as you do? |

| Career planning and development | Did you grow up in a rural setting? Did your medical school/residency have a rural focus? Did you do a fellowship? When you met your partner, did you know you were interested in rural practice? Did your career plans affect the spouse that you chose? What advice would you give a female resident or student considering rural practice? |

| Spouse relationships and roles | Are you married or do you have a partner? Do you have any children? How many? How old are they? Does your partner work? What kind of work does he/she do? [If partner/spouse works part time or doesn’t work outside the home]: • How did you come to that decision? • What has that meant to you as a couple? • Have you made financial sacrifices to make this work? |

| Work-life balance | What do you see as the challenges for women in rural practice? How are you managing with your work-life balance? How do you bring your work life and personal life work in balance? How do you prioritize your responsibilities? What aspect of your work is most challenging? How has your career affected your family? What part does your partner play in your work-life balance? What solutions have you found? |

ED = emergency department; OB = obstetrics.

Interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. After several interviews, additional questions were developed to explore some topics in greater depth. Transcripts were analyzed using an immersion and crystallization approach, and a list of emergent themes was developed.28 Themes were expanded and explored in detail by searching transcripts for commonalities and differences in patterning of statements. Interviews were listened to, read, and re-read iteratively by multiple team members, and through group discussion, we developed a detailed coding manual. Each interview was coded by at least 2 researchers, with the assistance of NVivo software (QSR International), creating an audit trail. We looked for heterogeneity within themes, searching for disconfirming evidence and including minority perspectives.29 Codes were cross-checked, and disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached (code-recode strategy).30 The emergent themes were critically examined to identify new discourse. Researchers engaged in a continuous process of reflexivity.31

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Michigan State University, Columbia University, and the University of Kentucky.

RESULTS

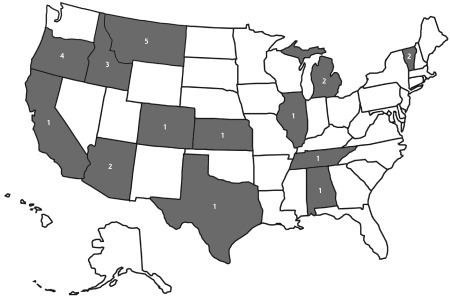

We completed and analyzed 25 interviews. Participant demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. The interviewed physicians represented geographically diverse states (Figure 1). Participants also varied considerably with respect to ages and life stages, but not race and ethnicity, and none described having female partners.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Participants, Their Practices, and Their Partners’ Work (N = 25)

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| ≤34 | 4 (16) |

| 35–44 | 12 (48) |

| 45–54 | 7 (28) |

| ≥55 | 2 (8) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian (white) | 24 (96) |

| Non-white | 1 (4) |

| Rural origina | |

| Yes | 15 (60) |

| No | 10 (40) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 19 (76) |

| Partnered but not married | 3 (12) |

| Single | 3 (12) |

| Children | |

| Yes, adult children only | 4 (16) |

| Yes, minor children living in household | 16 (64) |

| No | 5 (20) |

| Self-reported average weekly practice hours | |

| Part time, <40 hours | 4 (16) |

| Part time, ≥40 hours | 2 (8) |

| Full time, 40–60 hours | 14 (56) |

| Full time, >60 hours | 5 (20) |

| Practice scope | |

| Outpatient only | 1 (4) |

| Practice includes inpatient or after-hours care | 21 (84) |

| Practice includes obstetrics | 14 (56) |

| Partner workb | |

| Full time | 9 (41) |

| Part time | 7 (32) |

| Telecommutes/works from home | 6 (27) |

| Not employed | 4 (18) |

| Student | 2 (9) |

| Professionalc | 13 (59) |

| First-/mid-level officer and managerc | 3 (14) |

| Craft workerc | 1 (5) |

| Sales workerc | 1 (5) |

| Practice type | |

| Hospital-owned group practice | 8 (32) |

| Group private practice | 5 (20) |

| Solo private practice | 5 (20) |

| Federally qualified health center/rural health clinic | 6 (24) |

| Indian Health Service | 1 (4) |

Lived in rural community before age 18.

Data for only the 22 respondents who were married or partnered.

Job classifications based on US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2010 Job Classification Guide.32 Some partners had multiple job classifications.

Figure 1.

Participants’ practice locations.

Note: Numbers shown are numbers of practices.

Participants described many inherent rewards of rural practice, but also detailed conflicts between their professional demands and family lives. Some were usually able to maintain balance, but experienced intermittent periods of considerable stress. Women with young children and those new to rural practice described this stress most acutely. Although we will focus on successful women’s strategies as themes, the experiences of women with precarious work-life balance are also illustrative. Participants described several strategies that facilitated successful work-life balance, and many combined different approaches, shown in Table 3 and discussed below.

Table 3.

Key Strategies Supporting Rural Practice and Representative Quotes

| Strategy | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Variations in work hours and flexibility | “Being part time and resisting the temptation to go more full time just because you’d like more money has absolutely been key for me… If I didn’t have those days in between to recharge… or do the laundry, for heaven’s sake, I don’t know how I would have raised kids…” (Physician 16) “I have a lot of control over my schedule, and so even if I need to be at something for the kids, I can say, ‘Okay, I’m not going to be here Friday, and instead I can work Tuesday…’ The flexibility is a big deal.” (Physician 4) “When you’re not totally stressed the house is clean and dinner is made and your charts are done and maybe you exercise. And when that kind of shifts as the pendulum swings… we need cereal and the house is dirty and my charts pile up, and then I just get through it and then it swings back and I have a little space… People say you have to have separation or you have to keep a bright line, but actually I find that having a flexible line between work and home seems to help with balance.” (Physician 1) |

| Supportive relationships | “He stayed home with the kids until about 3 or 4 years ago, and so he was what I always called the responsible parent. He could be depended on to get them where they needed to get to, and then I would get there when I could.” (Physician 17) “He definitely accommodated my training and where we needed to be. The moves were all dependent on where I was going to go.” (Physician 13) “My husband and I met in medical school, and we knew that we both wanted to be rural family docs; when we met, that’s what we met saying.” (Physician 4) “He’s doing the same job I am, so we pretty much share things at home. I mean, we both cut the grass and we both clean, cook, and we took care of the kids… It’s really worked out well for us.” (Physician 2) “If I needed [my mother] to come over at 2 in the morning because I had a patient in labor, she came over… So she knows my call schedule and knows what’s going on.” (Physician 25) “My babysitter is very understanding, and what she’s told me is, ‘You know, if you have an emergency, just call me and let me know.’” (Physician 21) |

| Clear boundaries around work | “The doctor that founded our practice missed all of his kids’ stuff growing up because he was always on call, and people would always drop by, and he would drop everything. And so there was a lot of reeducating my patients… there was a little bit of resistance maybe from some people, but the vast majority of people were very understanding.” (Physician 17) |

Variations in Work Hours and Flexibility

Most participants worked full time, and the large majority of this group were satisfied putting in this number of hours. Full-time work was financially advantageous and facilitated a broad scope of practice. One-third of the study participants, however, worked a reduced schedule, and they identified doing so as a strategy to improve work-life balance and wellness. These “part-time” physicians often had very full schedules, however, despite working less than their colleagues. Some physicians had worked fewer hours at demanding times in their personal lives, for example, while they had young children.

A number of participants worked more than desired in response to community needs. For example, 1 physician’s group provided inpatient care, even though this wasn’t the group’s wish, because no other physicians were available to manage hospitalized patients. Another had increased her office schedule to accommodate the loss of a physician from the practice: “I’ve picked up an extra half day to help out.” (Physician 6)

These practices were often working to recruit staff or partners. One physician said, “I definitely need a nurse practitioner… I’ve taken 1 vacation since I opened my private practice [2 years ago]…. I need to have a day off during the week… having a half-day to do administrative work would be really nice, too.” (Physician 15) Another said, “Having just 1 more person to share the c-section call with would be key. It is hard… for people to take sustained time off. You go away for 2 or 3 weeks, that’s really hard on the others.” (Physician 16)

Others worked in settings in which part-time arrangements were not possible; this situation undermined satisfaction. One said, “My friends… [are] working 4-day weeks, outpatient-only practice, and sometimes just I feel so jealous… What I would give for just 1 day less of work a week… I don’t have that option.” (Physician 23)

Both part-time and full-time physicians emphasized that work flexibility was very important. For some, a reduced schedule allowed more control over their time: “The fact that I work part time makes it easier for me to be flexible because I can flex into those days that I don’t work, usually.” (Physician 4) Another interviewee, with more rigid scheduling, stated, “That’s probably the biggest thing that I wonder about staying here for. It’s not the call, it’s not being in a rural area, it’s just that my current work situation feels very inflexible.” (Physician 23)

Most participants had chosen to practice in a rural community, in part, because they could maintain a broad scope of practice. Many practiced obstetrics, cared for inpatients, made home visits, and delivered urgent and emergency care, in addition to their outpatient office practice. With this broad scope of practice comes unpredictability. We asked interviewees to estimate how many hours they worked each week. Many could not provide a clear number because their work was so variable. One answered, “Between 40 and 80.” (Physician 13)

Participants described an acceptance of this unpredictability, however, and a willingness to adapt to their changing circumstances. They varied the time they gave to family and recreation based on professional demands. Supportive partners with flexible schedules often facilitated this acceptance.

Supportive Relationships

Many participants described the support of their life partners as essential for career success. When asked “What advice would you give a female resident or student considering rural practice?” participants often recommended finding a supportive spouse. One said, “If I have to stop twice a month and drop what I’m doing to [deliver] a baby, I have to have somebody who is willing to watch the rest of the family and make sure that the stove gets turned off… without that you can’t have that job.” (Physician 9)

Respondents often acknowledged that their partners had made sacrifices in order to live in rural areas: “I think he’s happy now that we’re [in this community], but he has had to give up a fair amount for this. This was all really for me.” (Physician 10) They emphasized that without those sacrifices, their chosen professions would not be possible. Some spouses had left more desirable employment to allow their partners to pursue rural practice. Respondents often described an understanding that their own careers took priority over those of their male partners. Many partners were self-employed or worked part-time (Table 2). Some had professional careers but worked remotely with urban colleagues. Other partners came from rural communities, had rural occupations (such as farming), and strongly desired rural life.

The few participants whose partners would not, or could not, support the demands of their work planned to leave their positions in the near future. For example, 1 physician whose husband occasionally traveled for work felt that her current practice was not sustainable because she did not have a dependable caregiver for her child, should she be called for a delivery while her spouse was gone. She anticipated leaving her practice within the next year.

Often, male partners maintained primary responsibility for managing the household and caring for children. By taking this caregiver role, they allowed their physician partners to be more available to patients. One physician described her husband as “the glue” that holds the household together. (Physician 19)

Several other study participants were married to physicians in the same practice. In all of these 2-physician partnerships, 1 or both partners worked part time. These women described fairly egalitarian relationships, in which household work was distributed based on availability. One explained, “Every day, there’s someone who’s home in the afternoon… [who] meets the bus… that person does homework and music practice and dinner while the other person is finishing work… Whoever is working hits home at dinnertime, and so dinner’s ready, and then we have dinner together and then hang with the kids and hang together until everybody gets in bed. And then if we have charts left over, we do them after…” (Physician 4) Having a spouse with the same occupation helped facilitate understanding and support for the demands of rural practice: “I have a built-in someone to talk to about a bad day… we can spend a lot of time trying to work through difficult things.” (Physician 2)

Many participants had developed an interest in rural medicine before or during medical school, and sought out life partners who were willing to live in a rural community. For some, practicing in a rural community was a way to return home or to return to a community like their home community; 60% of our study sample was of rural origin (Table 2). Others had chosen rural practice because their partner had rural ties, made a mutual decision to move to a rural community with their partner, or chosen their partner after their rural career developed.

Finally, some families relied heavily on grandparents for assistance with child care. Often, physicians or their partners returned to their parents’ communities, in part, because this support would be available. Others were able to identify flexible caregivers outside the family.

Participants had the most difficulty finding child care for emergencies and call nights. One explained, “I’ve had a lot of people who… say, ‘Hey, if you’re on call, we can help with [your child],’ but I don’t think they understand…I have to literally be able to run out the door and be at the hospital in minutes, and it’s not practical for me to pack up my daughter and take her to somebody’s house… it’s difficult because I don’t think everybody necessarily understands the challenges of what this job means.” (Physician 22) Although finding child care was frequently identified as a challenge, most study participants were able to arrange satisfying child care.

Clear Boundaries Around Work

Participants often stated that limiting their work and protecting personal time was essential for their well-being. Although they defined boundaries differently, nearly all described limiting patient care to allow adequate time for vacation, recreation, and parenting. Most were part of group practices, allowing others to “cover” their patients. Even those in solo practice, however, described the need to maintain personal time, for example: “Once a year I take a… vacation out of the country, [and] I don’t work Sundays.” (Physician 3)

Some physicians reframed patient expectations in order to maintain their wellness. For example, 1 described being approached in public places, or called at home by patients when not working. She responded by “keep[ing]… a bit distant so that they realize that’s not okay.” She also redirected them: “I’ll give them a bit of advice but then say, ‘Call Tuesday morning and bring them in.’” (Physician 10) Another reminded patients, “I’m a mom, too… when I’m not [on call] my partner is going to be covering because I need to be with my kids.” (Physician 17) Participants reported that most patients supported their desire to maintain these boundaries.

When conflicts arose between patient care and family needs, however, participants experienced distress. Although they acknowledged the importance of caring for themselves and their families, they felt guilty when they were not available for patients. One said, “I wish, I wish, I wish that I could figure out a way to do less in my work life and more in my family life without making my patients feel like they’re not important to me, because that’s what winds up happening when I say I’m going to take time with my family.” (Physician 19) Another interviewee was contemplating leaving her practice, because “I just am not sure I can continue to deal with… situations where it’s on me to either make a decision about my child or my childcare or shutting down a clinic for a whole day and having patients be out of luck.” (Physician 22)

DISCUSSION

Women in rural family medicine continue to experience challenges in balancing the demands of work with the needs of family life. This study adds unique information to current literature by exploring ways these physicians are meeting these challenges. The opportunity for variable and flexible work scheduling, as well as the support of spouses, life partners, or other family members, were cited as key facilitating factors. Although physicians in our study reported a high sense of personal responsibility for patients, they also protected time with their families and their own need for rest and recovery. Remaining open to the unpredictable nature of rural practice helped them adapt to patients’ changing needs.

The results suggest that women physicians considering rural practice may be more satisfied and successful if they seek flexible employers and choose communities where support is available, or if they look for ways to build support networks as they are choosing practice settings. They may also benefit from developing strategies to negotiate boundaries with patients and developing skills to maintain their wellness.

Educators can help students and residents develop these skills by providing opportunities to practice self-care, set boundaries, and reflect on these issues. Educators might also consider talking explicitly with learners about seeking life partners who are willing and able to support rural practice careers, if relevant.33

Our findings have important implications for future research. It would be useful to discover whether contemporary men in rural practice face similar challenges and have undertaken similar coping strategies. Greater gender equality within physician partnerships34 appears to facilitate contemporary women physicians’ ability to build and sustain careers in rural medicine, but this same movement toward equality may make rural practice more challenging for men, who are also more likely to have long-term 2-career relationships. It would also be useful to quantitatively explore the prevalence of these coping strategies, and how they vary with age, racial and ethnic background, region, parenting styles and beliefs, and family structure. Finally, the hidden cost of rural practice for supporting partners and spouses of both genders should be explored further.

Although many women in our study had built successful careers, the obstacles to rural practice should not be minimized. Women with young children, and those new to rural practice, found this work particularly challenging. Meeting patients’ needs often required tremendous support from their families and communities. Simply creating this support took major effort. Rural practices should consider the needs of families when recruiting and retaining physicians, and should explore ways to support flexible scheduling and adequate family and personal time. Communities could also provide readily available child care, even in the middle of the night. By intentionally assessing and responding to individual physician and family needs, practices and communities may be able to create solutions that better support women physicians’ long-term satisfaction and success. Although our study was specific to rural physicians, its results also demonstrate the importance of creating national policies that support all working women and their families.

This study had some limitations. Our sample lacked diversity in the race, ethnicity, marital status, and sexual orientation of participants. Although the single women we interviewed had unique challenges, we did not have a sufficient sample size of single women to reach saturation in describing their experiences. Thus, this article focuses primarily on the experiences of physicians in long-term heterosexual relationships who have children in the home or have raised children in the past.

Approximately 84% of rural primary care physicians in the United States are non-Hispanic white.35 We could not find demographic descriptions of rural women family physicians in the literature, but it is possible that our methodology resulted in a sample that does not reflect this population. In particular, underrepresented minority women practicing in rural communities may have different experiences. This limitation is important because although many rural counties are predominantly non-Hispanic white, high numbers of African American, Hispanic, and Native American populations are geographically concentrated in several rural regions, often where health care disparities are the most acute.36–38 Finally, the study results may be influenced by our interpretation as researchers; we sought to minimize this bias by engaging in a continuous process of reflexivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the American Medical Association’s Joan F. Giambalvo Fund for the Advancement of Women for their financial support; Diane Doberneck, PhD; and the physicians who graciously participated.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This study was supported by a scholarship from the American Medical Association’s Joan F. Giambalvo Fund for the Advancement of Women.

Disclaimer: This work represents the views of the authors and does not represent the opinions of the Joan F. Giambalvo Fund or the American Medical Association.

Previous presentations: This work was previously presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference; May 1–5, 2013; Baltimore, Maryland; the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Medical Student Education; January 24–27, 2013; San Antonio, Texas; the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting; December 1–5, 2012; New Orleans, Louisiana; and the American Medical Association, Annual Meeting, June 14–16, 2012; Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Rosenblatt RA, Chen FM, Lishner DM, Doescher MP. The future of family medicine and implications for rural primary care physician supply. WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/RHRC_FR125_Rosenblatt.pdf. Published Aug 2010 Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on the Future of Rural Health Care, Board on Health Care Services. Quality through collaboration: the future of rural health care. Institute of Medicine; http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2004/Quality-Through-Collaboration-The-Future-of-Rural-Health.aspx. Published Nov 1, 2004 Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendling AL. Dedicated issue on rural health: inspiration, celebration, and a challenge for the future. Fam Med. 2010; 42(10): 690–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu JJ, Bellamy G, Barnet B, Weng S. Bypass of local primary care in rural counties: effect of patient and community characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2008; 6(2): 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doescher MP, Ellsbury KE, Hart LG. The distribution of rural female generalist physicians in the United States. J Rural Health. 2000; 16(2): 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Fordyce M, Andes S, Hart LG. Which medical schools produce rural physicians? A 15-year update. Acad Med. 2010; 85(4): 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SG, Nsiah-Kumi PA, Jones PR, Pamies RJ. Pipeline programs in the health professions, part 1: preserving diversity and reducing health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009; 101(9): 836–840, 845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson EH, Johnson KE, Norris TE, Lishner DM, Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG. State of the health workforce in rural America: profiles and comparisons. WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; http://depts.washington.edu/wwamiric/pdfs/monograph/RuralCh0.TOC.pdf. Published Aug 2003 Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lurie N, Margolis K, McGovern PG, Mink P. Physician self-report of comfort and skill in providing preventive care to patients of the opposite sex. Arch Fam Med. 1998; 7(2): 134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Incitti F, Rourke J, Rourke LL, Kennard M. Rural women family physicians. Are they unique? Can Fam Physician. 2003; 49: 320–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dresden GM, Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Skillman SM, Benedetti TJ. Influence of obstetric practice on workload and practice patterns of family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Ann Fam Med. 2008; 6(Suppl 1): S5–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, Nielsen K, Hunsaker M. A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2010; 10(3): 1531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayburn WF, Klagholz JC, Murray-Krezan C, Dowell LE, Strunk AL. Distribution of American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists fellows and junior fellows in practice in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 119(5): 1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks RG, Walsh M, Mardon RE, Lewis M, Clawson A. The roles of nature and nurture in the recruitment and retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002; 77(8): 790–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock C, Steinbach A, Nesbitt TS, Adler SR, Auerswald CL. Why doctors choose small towns: a developmental model of rural physician recruitment and retention. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 69(9): 1368–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blankfield RP, Goodwin M, Jaén CR, Stange KC. Addressing the unique challenges of inner-city practice: a direct observation study of inner-city, rural, and suburban family practices. J Urban Health. 2002; 79(2): 173–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pathman DE, Williams ES, Konrad TR. Rural physician satisfaction: its sources and relationship to retention. J Rural Health. 1996; 12(5): 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rourke LL, Rourke J, Brown JB. Women family physicians and rural medicine: can the grass be greener in the country. Can Fam Physician. 1996; 42: 1063–1067, 1077–1082. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenger J, Cashman SB, Savageau JA. The primary care physician workforce in Massachusetts: implications for the workforce in rural, small town America. J Rural Health. 2008; 24(4): 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimball EB, Crouse BJ. Perspectives of female physicians practicing in rural Wisconsin. WMJ. 2007; 106(5): 256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank E, McMurray JE, Linzer M, Elon L; Society of General Internal Medicine Career Satisfaction Study Group. Career satisfaction of US women physicians: results from the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159(13): 1417–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haggerty TS, Fields SA, Selby-Nelson EM, Foley KP, Shrader CD. Physician wellness in rural America: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013; 46(3): 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellsbury KE, Baldwin LM, Johnson KE, Runyan SJ, Hart LG. Gender-related factors in the recruitment of physicians to the rural Northwest. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002; 15(5): 391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wainer J. Cooperative knowledge-making with female and male rural doctors. Rural Remote Health. 2004; 4(2): 267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spenny ML, Ellsbury KE. Perceptions of practice among rural family physicians—is there a gender difference? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000; 13(3): 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCAs). WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999: 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2010 Job Classification Guide. http://www1.eeoc.gov//employers/eeo1survey/jobclassguide.cfm?renderforprint=1 Accessed Mar 10, 2016.

- 33.Roseamelia C, Greenwald JL, Bush T, Pratte M, Wilcox J, Morley CP. A qualitative study of medical students in a rural track: views on eventual rural practice. Fam Med. 2014; 46(4): 259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobecks NW, Justice AC, Hinze S, et al. When doctors marry doctors: a survey exploring the professional and family lives of young physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999; 130(4 Pt 1): 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. Rural and Urban Primary Care Physician Findings: AAMC 2009 Physician Survey of Primary Care Chartbook. https://ruralhealth.und.edu/pdf/2009-physician-survey-primary-care-chartbook.pdf. Published Feb 2015 Accessed Nov 9, 2015.

- 36.Johnson KM. Rural Demographic Change in the New Century: Slower Growth, Increased Diversity. University of New Hampshire Carsey Institute; https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/rural-demographic-change-new-century-slower-growth-increased-diversity. Published Feb 21, 2012 Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Probst JC, Samuels ME, Jespersen KP, Willert K, Swann RS, McDuffie JA. Minorities in Rural America: An Overview of Population Characteristics. South Carolina Rural Health Research Center, University of South Carolina; http://rhr.sph.sc.edu/report/MinoritiesInRuralAmerica.pdf. Published 2002 Accessed Nov 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Probst JC, Moore CG, Glover SH, Samuels ME. Person and place: the compounding effects of race/ethnicity and rurality on health. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(10): 1695–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]