Abstract

The chromosome 5p15.33 TERT-CLPTM1L region has been identified by genome-wide association studies as a susceptibility locus of multiple malignancies. However, the involvement of this locus in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) development is still largely unclear. We fine-mapped the TERT-CLPTM1L region through genotyping 15 haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNPs) using a two stage case-control strategy. After analyzing 2098 ESCC patients and frequency-matched 2150 unaffected controls, we found that rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs451360 genetic polymorphisms are significantly associated with ESCC risk in Chinese (all P<0.05). Reporter gene assays indicated that the ESCC susceptibility SNP rs2736100 locating in a potential TERT intronic promoter has a genotype-specific effect on TERT expression. Similarly, the CLPTM1L rs451360 SNP also showed allelic impacts on gene expression. After measuring TERT and CLPTM1L expression in sixty-six pairs of esophageal cancer and normal tissues, we observed that the rs2736100 G risk allele carriers showed elevated oncogene TERT expression. Also, subjects with the rs451360 protective T allele had much lower oncogene CLPTM1L expression than those with G allele in tissue specimens. Results of these analyses underline the complexity of genetic regulation of telomere biology and further support the important role of telomerase in carcinogenesis. Our data also support the involvement of CLPTM1L in ESCC susceptibility.

Keywords: TERT, CLPTM1L, polymorphism, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, susceptibility

INTRODUCTION

The chromosome 5p15.33 TERT-CLPTM1L region has been repeatedly proved to be a susceptibility locus of multiple malignancies according to genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Independent susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this region were identified in lung cancer [1–5], melanoma [6], nonmelanoma skin cancer [7,8], glioma [9], bladder cancer [10], pancreatic cancer [11], testicular germ cell cancer [12], estrogen-negative breast cancer [13], ovarian cancer [14] and prostate cancer [15], suggesting that the region harbors several essential elements associating etiology of multiple cancers. The chromosome 5p15.33 region harbors two plausible candidate coding genes TERT and CLPTM1L. TERT encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase reverse transcriptase [16]. Activated TERT transcription in many cancers leads to increased telomerase activity to counteract telomere shortening and promotes malignant transformation of normal cells [17]. CLPTM1L encodes the cleft lip and palate-associated transmembrane 1 like protein (also known as cisplatin resistance related protein, CRR9). Accumulated evidences demonstrated that CLPTM1L may act as an oncogene in lung and pancreatic cancers [20–22].

As one of the most common and fatal malignant tumors in the world, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) was diagnosed at a relatively high frequency in China [24]. It has been shown that heavy alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, micronutrient deficiency and dietary carcinogen exposure are risk factors of this lethal disease [25,26]. However, only a portion of exposed individuals develop ESCC, indicating that genetic factors may also impact esophageal malignant transformation. Considering the involvement of the 5p15.33 TERT-CLPTM1L locus in ESCC is still largely unclear, we examined the associations between 15 haplotype-tagging SNPs (htSNP) across the TERT-CLPTM1L locus and ESCC risk in three large independent hospital-based case-control studies. To investigate the biological function of three ESCC susceptibility SNPs, we examined impacts of these genotypes on TERT or CLPTM1L expression using luciferase reporter gene assays and inspected the association between these polymorphisms and gene expression in esophageal tissues.

RESULTS

Associations between the TERT-CLPTM1L htSNPs and ESCC risk in the discovery case-control set

Genotype distributions of fifteen TERT-CLPTM1L genetic variants in the Jiangsu discovery set are showed in Table 1. All observed genotype frequencies in either controls or cases conform to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (all P > 0.05). Distributions of the all genotypes were then compared among patients and controls. Frequencies of rs2853691, rs2736100 or rs45136 genotypes among patients differed significantly from those among controls (all P < 0.05). Logistic regression analyses revealed that rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs451360 SNPs were significantly associated with ESCC risk (rs2853691: allelic OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.25-1.80, P = 7.0 × 10−6; rs2736100: allelic OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.17-1.64, P = 7.8 × 10−5; rs45136: allelic OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.52-0.91, P = 0.007) (Table 1). However, no statistically significant differences of other htSNPs were observed between cases and controls (all P > 0.05) (Table 1). Therefore, no additional genotyping and analyses on these twelve htSNPs were done in the next studies.

Table 1. Associations between candidate SNPs in the TERT-CLPTM1L locus and risk of ESCC in Jiangsu case-control set.

| No. | rs ID | Position | Base change | MAF1 | Genotype (588 cases and 600 controls) | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common2 | Heterozygous2 | Rare2 | OR(95%CI)3 | ||||||

| 1 | rs2853691 | 1305950 | T>C | 0.257 | 44.2/54.6 | 43.5/39.4 | 12.3/6.0 | 1.50 (1.25-1.80) | 7.0 × 10−6 |

| 2 | rs2736122 | 1310621 | G>A | 0.058 | 87.8/89.1 | 12.1/10.3 | 0.1/0.6 | 1.07 (0.75-1.52) | 0.701 |

| 3 | rs2075786 | 1319310 | A>G | 0.128 | 74.5/76.3 | 24.0/21.8 | 1.5/1.9 | 1.06 (0.83-1.36) | 0.621 |

| 4 | rs4246742 | 1320356 | T>A | 0.355 | 43.8/40.9 | 44.6/47.0 | 11.7/12.0 | 0.93 (0.78-1.10) | 0.397 |

| 5 | rs4975605 | 1328528 | C>A | 0.053 | 90.5/89.7 | 9.3/10.1 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.90 (0.61-1.33) | 0.586 |

| 6 | rs2736100 | 1339516 | A>C | 0.405 | 28.1/35.7 | 46.7/47.6 | 25.2/16.7 | 1.39 (1.17-1.64) | 7.8 × 10−5 |

| 7 | rs2853676 | 1341547 | C>T | 0.126 | 75.3/75.9 | 23.0/22.9 | 1.7/1.1 | 1.05 (0.82-1.35) | 0.664 |

| 8 | rs2736098 | 1347086 | C>T | 0.392 | 40.8/41.0 | 39.7/39.6 | 19.5/19.4 | 1.01 (0.85-1.19) | 0.919 |

| 9 | rs2853668 | 1353025 | G>T | 0.293 | 49.5/49.8 | 42.1/42.0 | 8.4/8.3 | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | 0.927 |

| 10 | rs2735845 | 1353584 | C>G | 0.328 | 45.2/45.3 | 44.5/43.7 | 10.3/11.0 | 0.99 (0.83-1.18) | 0.890 |

| 11 | rs6554759 | 1370102 | A>G | 0.045 | 90.3/91.1 | 9.4/8.7 | 0.3/0.2 | 1.12 (0.76-1.66) | 0.554 |

| 12 | rs451360 | 1372680 | C>A | 0.117 | 83.9/78.2 | 15.3/20.2 | 0.8/1.6 | 0.69 (0.52-0.91) | 0.007 |

| 13 | rs380286 | 1373247 | G>A | 0.125 | 77.4/76.5 | 21.5/22.0 | 1.1/1.5 | 0.94 (0.73-1.21) | 0.612 |

| 14 | rs402710 | 1373722 | C>T | 0.325 | 44.5/45.8 | 44.9/43.4 | 10.6/10.8 | 1.03 (0.86-1.22) | 0.764 |

| 15 | rs452932 | 1383253 | T>C | 0.160 | 72.6/70.9 | 25.6/26.1 | 1.8/2.9 | 0.90 (0.71-1.13) | 0.352 |

Note: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; MAF, minor allele frequency; OR, odds ratios; 95%CI, 95% confident intervals.

MAF in healthy controls.

% of case/% of control.

Allelic OR calculated by logistic regression.

TERT-CLPTM1L rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs45136 polymorphisms contribute to ESCC susceptibility

Associations between genotypes of rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs45136 genetic variants and ESCC risk were calculated using unconditional logistic regression analyses in Jiangsu set (Table 2). The rs2853691 G allele was showed to be risk allele; subjects having the AG or GG genotype had an OR of 1.19(95% CI = 0.88-1.60, P = 0.214) or 1.40(95% CI = 1.10-1.77, P = 0.006) for developing ESCC, respectively, compared with subjects having the AA genotype. It was observed that the odds of having the rs2736100 TG or GG genotype in patients was 1.32 (95% CI = 0.98-1.76, P = 0.066) or 1.37 (95% CI = 1.14-1.64, P = 7.3 × 10−4) compared with the TT genotype. Moreover, a significantly decreased OR was associated with the rs451360 GT genotype (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.48-0.93, P = 0.018) but not the TT genotype (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.41-1.29, P = 0.275). All ORs were adjusted for sex, age, smoking and alcohol drinking status.

Table 2. Genotype frequencies of rs2853691 A>G, rs2736100 T>G and rs451360 G>T SNPs in the TERT-CLPTM1L locus among cases and controls and their association with ESCC risk.

| Studies | rs2853691 A>G | rs2736100 T>G | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes | Cases No. (%) | Controls No. (%) | OR1(95% CI) | P1 | Genotypes | Cases No. (%) | Controls No. (%) | OR1(95% CI) | P1 | |

| n = 588 | n = 600 | n = 588 | n = 600 | |||||||

| Jiangsu set | AA | 260(44.2) | 328(54.6) | 1.00 | TT | 165(28.1) | 214(35.7) | 1.00 | ||

| AG | 256(43.5) | 236(39.4) | 1.19(0.88-1.60) | 0.214 | TG | 275(46.7) | 285(47.6) | 1.32(0.98-1.76) | 0.066 | |

| GG | 72(12.3) | 36(6.0) | 1.40(1.10-1.77) | 0.006 | GG | 148(25.2) | 101(16.7) | 1.37(1.14-1.64) | 7.3 × 10−4 | |

| n = 1000 | n = 1000 | n = 1000 | n = 1000 | |||||||

| Shandong set | AA | 503(50.3) | 557(55.7) | 1.00 | TT | 279(27.9) | 363(36.3) | 1.00 | ||

| AG | 418(41.8) | 393(39.3) | 1.17(0.96-1.43) | 0.116 | TG | 472(47.2) | 475(47.5) | 1.24(0.99-1.54) | 0.051 | |

| GG | 79(7.9) | 50(5.0) | 1.30(1.07-1.59) | 0.010 | GG | 249(24.9) | 162(16.2) | 1.48(1.29-1.70) | 2.2 × 10−6 | |

| n = 510 | n = 550 | n = 508 | n = 547 | |||||||

| Hebei set | AA | 270(52.9) | 315(57.3) | 1.00 | TT | 163(32.1) | 222(40.6) | 1.00 | ||

| AG | 194(38.0) | 202(36.7) | 1.08(0.83-1.41) | 0.584 | TG | 244(48.0) | 241(44.0) | 1.45(1.09-1.92) | 0.011 | |

| GG | 46(9.1) | 33(6.0) | 1.29(1.01-1.64) | 0.048 | GG | 101(19.9) | 84(15.4) | 1.32(1.10-1.59) | 3.2 × 10−4 | |

| n = 2098 | n = 2150 | n = 2096 | n = 2147 | |||||||

| Pooled | AA | 1033(49.2) | 1200(55.8) | 1.00 | TT | 607(29.0) | 799(37.2) | 1.00 | ||

| AG | 868(41.4) | 831(38.7) | 1.16(1.01-1.32) | 0.036 | TG | 991(47.2) | 1001(46.6) | 1.32(1.44-1.53) | 2.1 × 10−4 | |

| GG | 197(9.4) | 119(5.5) | 1.32(1.16-1.50) | 2.2 × 10−5 | GG | 498(23.8) | 347(16.2) | 1.41(1.29-1.55) | 4.0 × 10−8 | |

| Studies | rs451360 G>T | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes | Cases No. (%) | Controls No. (%) | OR1(95% CI) | P1 | |

| n = 588 | n = 600 | ||||

| Jiangsu set | GG | 493(83.9) | 469(78.2) | 1.00 | |

| GT | 90(15.3) | 121(20.2) | 0.67(0.48-0.93) | 0.018 | |

| TT | 5(0.8) | 10(1.6) | 0.72(0.41-1.29) | 0.275 | |

| n = 1000 | n = 1000 | ||||

| Shandong set | GG | 819(81.9) | 760(76.0) | 1.00 | |

| GT | 176(17.6) | 222(22.2) | 0.70(0.55-0.89) | 0.003 | |

| TT | 5(0.5) | 18(1.8) | 0.56(0.33-0.95) | 0.033 | |

| n = 510 | n = 550 | ||||

| Hebei set | GG | 416(81.6) | 417(75.8) | 1.00 | |

| GT | 90(17.6) | 124(22.6) | 0.68(0.49-0.93) | 0.017 | |

| TT | 4(0.8) | 9(1.6) | 0.59(032-1.08) | 0.086 | |

| n = 2098 | n = 2150 | ||||

| Pooled | GG | 1728(82.3) | 1646(76.6) | 1.00 | |

| GT | 356(17.0) | 467(21.7) | 0.68(0.58-0.81) | 6.3 × 10−6 | |

| TT | 14(0.7) | 37(1.7) | 0.61(0.44-0.85) | 0.003 | |

Note: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Data were calculated by logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, smoking and drinking status.

In two validation sets (Shandong set and Hebei set), the significant associations between rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs45136 SNPs and ESCC risk were also observed (Table 2). Individuals with rs2853691 GG genotype showed significantly increased ESCC risk compared with those with rs2853691 AA genotype in both validation sets (ORShandong = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.07-1.59, P = 0.010; ORHebei = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.01-1.64, P = 0.048). Carriers of rs2736100 GG genotype showed significantly elevated risks developing ESCC compared with rs2736100 TT carriers (ORBeijing = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.29-1.70, P = 2.2 × 10−6; ORHebei = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.10-1.59, P = 3.2 × 10−4). The odds of having the rs451360 GT or TT genotype in patients was 0.70 (95% CI = 0.55-0.89, P=0.003) or 0.56 (95% CI = 0.33-0.95, P = 0.033) compared with the AA genotype in Shandong set. However, only rs451360 GT genotype was significantly associated with ESCC risk (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.49-0.93, P = 0.017) in Hebei validation set.

In the pooled analyses, we found that the rs2853691 AG or GG genotype carriers had a 1.16-fold or 1.32-fold increased risk to develop ESCC compared to the AA genotype carriers (95% CI = 1.01-1.32, P = 0.036 or 95% CI = 1.16-1.50, P = 2.2 × 10−5) (Table 2). Intriguingly, either rs2736100 TG or GG genotype was significantly associated with ESCC risk (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.44-1.53, P = 2.1 × 10−4; OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.29-1.55, P = 4.0 × 10−8) compared to the TT genotype. Similarly, subjects having the rs451360 GT or TT genotype had an OR of 0.68 (95%CI = 0.58-0.81, P = 6.3 × 10−6) or 0.61 (95%CI = 0.44-0.85, P = 0.003) for developing ESCC compared with individual having the GG genotype.

Stratified analyses of associations between rs2853691, rs2736100 or rs451360 SNP and ESCC risk

The risk of ESCC associated with the rs2853691, rs2736100 or rs451360 SNP was further investigated by stratifying for age, sex, smoking and alcohol drinking status using the combined data of three case-control sets (Table 3). For rs2853691, a significantly increased risk of ESCC associated with the rs2853691 GG genotype compared with the AA genotype was observed for both groups stratified by sex, smoking and drinking status (all P < 0.05) or the group aged 58 years or younger (P = 5.4 × 10−5). Additionally, the rs2853691 AG genotype was only associated with ESCC risk in the male group (P = 0.026), the smoking group (P = 0.008) or the drinking group (P = 0.013). For rs2736100, significant associations between TG or GG genotype and ESCC risk were observed in all stratified groups (all P < 0.05), but not in the drinking group (P = 0.974). There was a significantly multiplicative gene-drinking interaction (Pinteraction = 0.012). For rs451360, the TT genotype was only associated with ESCC risk in the male group (P = 0.006), the group aged 58 years or younger (P = 0.016), the non-smoking group (P = 0.025) or the drinking group (P = 0.005). However, significant associations between the rs451360 GT genotype and ESCC risk were observed in all stratified groups (all P < 0.05), but not in the female group (P = 0.326).

Table 3. Risk of ESCC associated with rs2853691 A>G, rs2736100 T>G and rs451360 G>T genotypes by age, sex, smoking, and drinking status.

| Variable | rs2853691 A>G | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA1 | AG1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | GG1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | Pinteraction3 | |

| Sex | 0.842 | |||||||

| Male | 789/918 | 661/624 | 1.19(1.02-1.38) | 0.026 | 137/93 | 1.27(1.10-1.47) | 0.001 | |

| Female | 244/288 | 207/207 | 0.88(0.62-1.25) | 0.475 | 60/26 | 1.41(1.05-1.91) | 0.025 | |

| Age (year) | 0.363 | |||||||

| ≤58 | 535/606 | 431/418 | 1.08(0.89-1.32) | 0.431 | 109/54 | 1.48(1.22-1.79) | 5.4 × 10−5 | |

| >58 | 498/594 | 437/413 | 1.21(0.99-1.46) | 0.055 | 88/65 | 1.19(0.99-1.43) | 0.055 | |

| Smoking | 0.096 | |||||||

| No | 290/721 | 196/499 | 0.98(0.79-1.22) | 0.863 | 42/68 | 1.27(1.03-1.56) | 0.027 | |

| Yes | 743/479 | 672/332 | 1.27(1.07-1.52) | 0.008 | 155/51 | 1.36(1.14-1.61) | 0.001 | |

| Drinking | 0.980 | |||||||

| No | 465/709 | 373/507 | 1.06(0.87-1.29) | 0.582 | 85/63 | 1.44(1.19-1.74) | 1.6 × 10−4 | |

| Yes | 568/491 | 495/324 | 1.27(1.05-1.54) | 0.013 | 112/56 | 1.24(1.04-1.48) | 0.017 | |

| Variable | rs2736100 T>G | Pinteraction3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT1 | TG1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | GG1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | ||

| Sex | 0.253 | |||||||

| Male | 478/610 | 750/762 | 1.25(1.06-1.47) | 0.008 | 357/262 | 1.92(1.28-2.88) | 0.002 | |

| Female | 129/189 | 241/239 | 1.92(1.28-2.88) | 0.002 | 141/85 | 1.77(1.40-2.24) | 1.9 × 10−6 | |

| Age (year) | 0.606 | |||||||

| ≤58 | 311/411 | 502/497 | 1.27(1.02-1.57) | 0.030 | 262/168 | 1.46(1.28-1.68) | 6.1 × 10−8 | |

| >58 | 296/388 | 489/504 | 1.36(1.10-1.68) | 0.005 | 236/179 | 1.39(1.22-1.59) | 1.2 × 10−6 | |

| Smoking status | 0.065 | |||||||

| No | 138/479 | 244/600 | 1.48(1.15-1.89) | 0.002 | 145/206 | 1.57(1.36-1.82) | 1.4 × 10−9 | |

| Yes | 469/320 | 747/401 | 1.27(1.05-1.54) | 0.015 | 353/141 | 1.28(1.13-1.45) | 8.3 × 10−5 | |

| Drinking status | 0.012 | |||||||

| No | 221/486 | 463/588 | 1.90(1.52-2.37) | 1.9 × 10−6 | 238/203 | 1.62 (1.41-1.85) | 2.6 × 10−8 | |

| Yes | 386/313 | 528/413 | 1.00(0.81-1.22) | 0.974 | 260/144 | 1.22(1.07-1.39) | 0.003 | |

| Variable | rs451360 G>T | Pinteraction3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG1 | GT1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | TT1 | OR2 (95% CI) | P | ||

| Sex | 0.085 | |||||||

| Male | 1305/1230 | 271/375 | 0.65(0.54-0.78) | 3.6 × 10−6 | 11/30 | 0.60(0.42-0.86) | 0.006 | |

| Female | 423/416 | 85/92 | 0.80(0.52-1.24) | 0.326 | 3/7 | 0.63(0.26-1.54) | 0.310 | |

| Age (year) | 0.895 | |||||||

| ≤58 | 881/822 | 187/233 | 0.71(0.56-0.90) | 0.005 | 7/23 | 0.57(0.36-0.90) | 0.016 | |

| >58 | 847/824 | 169/234 | 0.63(0.50-0.80) | 1.3 × 10−4 | 7/14 | 0.66(0.41-1.06) | 0.087 | |

| Smoking | 0.932 | |||||||

| No | 443/1001 | 82/263 | 0.69(0.52-0.90) | 0.007 | 3/24 | 0.50(0.27-0.91) | 0.025 | |

| Yes | 1285/645 | 274/204 | 0.69(0.56-0.85) | 4.4 × 10−4 | 11/13 | 0.67(0.44-1.01) | 0.057 | |

| Drinking | 0.374 | |||||||

| No | 777/1004 | 139/258 | 0.70(0.55-0.90) | 0.006 | 7/17 | 0.74(0.46-1.20) | 0.224 | |

| Yes | 951/642 | 217/209 | 0.69(0.55-0.86) | 0.001 | 7/20 | 0.53(0.34-0.82) | 0.005 | |

Note: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Number of case patients with genotype/number of control subjects with genotype.

Data were calculated by logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age, smoking, and drinking status, where it was appropriate.

P values for gene-environment interaction were calculated using the multiplicative interaction term in SPSS software.

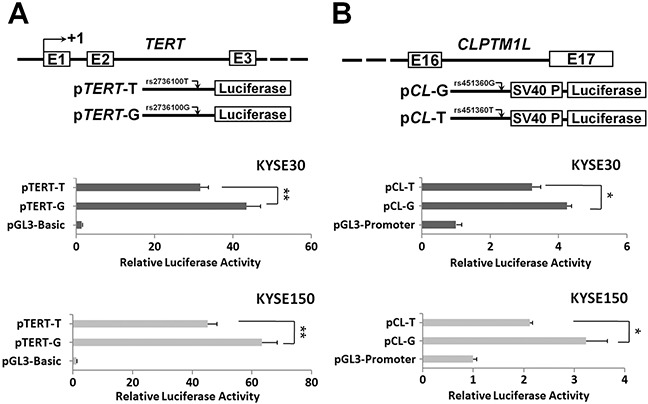

Functional relevance of TERT rs2736100 and CLPTM1L rs451360 genetic variants on gene expression

Considering the chromosome location of the three ESCC susceptibility SNPs, we only investigated the impacts of TERT rs2736100 and CLPTM1L rs451360 SNPs on gene expression. The rs2736100 variant locates in the intron 2 region of TERT. As shown in Figure 1A, reporter gene assays demonstrated that the intron 2 segment containing the rs2736100 flanking sequence showed promoter activities in KYSE30 and KYSE150 ESCC cells. Moreover, the TERT rs2736100G allelic reporter construct (pTERT-G) showed significantly higher luciferase activities compared to the rs920778T allelic reporter construct (pTERT-T) (both P<0.01) (Figure 1A). We next examined whether the ESCC susceptibility SNP rs451360 has an allele-specific effect on the intronic enhancer activity on CLPTM1L expression in ESCC. Either KYSE30 cells or KYSE150 cells transfected with the CLPTM1L pCL-T allelic plasmid showed significantly lower luciferase activities compared to cells expressing pCL-G allelic reporter construct (both P<0.05) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Transient luciferase reporter gene expression assays with constructs containing different rs2736100 allele of the TERT intron 2 region (A) or different rs451360 allele of the CLPTM1L intron 16 region (B) in KYSE30 cells or KYSE150 cells.

pRL-SV40 were cotransfected with these contructs to standardize transfection efficiency. Fold-changes were detected by defining the luciferase activity of cells co-transfected with pGL3-basic as 1. All experiments were performed in triplicates in three independent transfection experiments and each value represents mean ± SD. Compared with pGL3-Basic transfected cells, *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

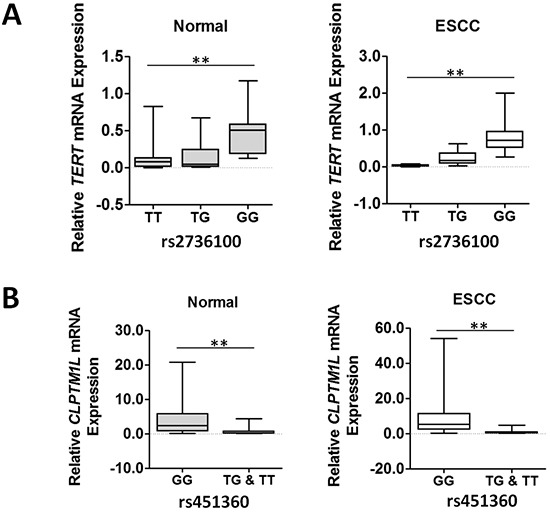

We next examined whether these two ESCC susceptibility SNPs has an allele-specific effect on gene expression in esophagus tissues. As shown in Figure 2A, we found that subjects with the rs920778 TT genotype had significantly lower TERT mRNA levels (mean ± SE) than those with the GG genotypes in normal esophagus tissues (0.128 ± 0.047 [n=18] vs. 0.493 ± 0.078 [n=17], P<0.01) or ESCC tissues (0.030 ± 0.006 [n=18] vs. 0.847 ± 0.120 [n=17], P<0.01). Similar results were observed when the CLPTM1L mRNA levels were compared between rs451360 GT+TT and GG genotypes in both normal tissues (0.713 ± 0.266 [n=17] vs. 4.810 ± 0.810 [n=49], P<0.01) and ESCC specimens (1.059 ± 0.346 [n=17] vs. 10.650 ± 1.922 [n=49], P<0.01).

Figure 2. TERT or CLPTM1L mRNA expression in normal and cancerous esophageal tissues grouped by rs2736100 or rs451360 genotypes.

The expression of individual TERT or CLPTM1L mRNA was calculated relative to expression of β-actin using the 2−dCt method. **P<0.01.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we systematically examined the impacts of SNPs in the TERT-CLPTM1L loci on ESCC susceptibility via a case-control design as well as gene expression of TERT or CLPTM1L in vitro and in vivo. After genotyping 15 htSNPs in the discovery stage, we identified three ESCC susceptibility genetic polymorphisms (rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs451360) which were validated in two validation case-control sets. Reporter gene assays indicated that the ESCC susceptibility SNP rs2736100 locating in a potential TERT intronic promoter has a genotype-specific effect on TERT expression. Similarly, the CLPTM1L rs451360 polymorphism also showed allelic effects on gene expression. Genotype-phenotype correlation data supported the regulatory role of these two genetic variants in TERT or CLPTM1L gene expression in vivo. Our observations support the hypothesis that genetic polymorphisms in oncogene regulatory elements might explain a part of ESCC genetic basis besides those genetic variants identified by GWAS [27–31].

Interestingly, TERT rs2736100 has been found to be associated with risk of lung cancer [1,2,24], glioma[9], testicular cancer [12],colorectal cancer [33], acute myeloid leukemia [34], pancreatic cancer [35] and bladder cancer [36]. However, its involvement in ESCC etiology is still largely unclear. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case-control study to investigate the association between the TERT rs2736100 polymorphism and ESCC risk. We observed a significantly increased ESCC risk among individuals with TERT rs2736100 G allele compared to carriers of rs2736100 T allele. It has been reported that increased TERT expression in ESCC tissues were observed compared to normal tissues [18,19], which indicated the oncogene nature of TERT in ESCC. Since rs2736100 G allele is associated with elevated TERT expression, the associations between the polymorphism and increased cancer risk are biologically plausible.

CLPTM1L appears to act as an oncogene with significantly increased expression in malignant tissues [20–23]. In line with this, CLPTM1L silencing by miR-494 can inhibit cell growth and invasion and induce ESCC cell apoptosis [23]. The CLPTM1L rs451360 polymorphism has been associated with decreased risk of lung cancer among different ethnic populations, with T allele as a protective allele [5,37-41]. Here, we provided first evidences that rs451360 SNP also play a part in ESCC susceptibility, which are unlikely to be attributable to unknown confounding factors due to having relatively large sample sizes, significantly increased odd ratios with small P values. Additionally, our genotype-phenotype correlation data between the rs451360 genetic variant and gene expression supports the case-control study since the protective T allele carriers showing less oncogene CLPTM1L expression. Since the TT genotype of the functional rs451360 SNP is relatively rare (about 1-2% among common populations), the potential clinical translation of this genetic variant might be compromised.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that there are three genetic polymorphisms (rs2853691, rs2736100 and rs451360) in the TERT-CLPTM1L loci are significantly associated with ESCC risk in Chinese populations. Our results underline the complexity of genetic regulation of telomere biology and further support the important role of telomerase in carcinogenesis. Our data also support the involvement of CLPTM1L in ESCC susceptibility. These results may lead to better understanding of ESCC etiology in different populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

This study consisted of three case-control sets: (a) Jiangsu set: 588 ESCC cases from Huaian No. 2 Hospital (Huaian, Jiangsu Province, China) and sex- and age-matched 600 controls. (b) Shandong set: 1000 cases with ESCC from Shandong Cancer Hospital, Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, Shandong Province, China) and sex- and age-matched (± 5 years) 1000 healthy controls. (c) Hebei study: 510 ESCC patients from Bethune International Peace Hospital (Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China) and 550 sex- and age-matched healthy controls. Sixty-six pairs of ESCC specimens and esophagus normal tissues adjacent to the tumors were obtained from surgically removed specimens of patients in Bethune International Peace Hospital and Huaian No. 2 Hospital. All individuals were ethnic Han Chinese. At recruitment, the informed consent was obtained from each subject. The detailed information on subject recruitments can be found in Supplementary Table S1 and our previous studies [42–44]. This study was approved by the institutional Review Boards.

SNP selection and genotyping

The TERT-CLPTM1L gene loci cover a 91716bp region of chromosome 5p15.33 and contain a great number of SNPs. An htSNP approach was utilized to analyze the TERT-CLPTM1L genetic polymorphisms globally [45]. Genotyped HapMap SNPs among Han Chinese and Japanese populations (HapMap Rel 21, NCBI B36) with a minor allele frequency >5% were included in the selection. The htSNPs were chosen in a 95716bp region (91716bp TERT-CLPTM1L loci and 2kb up-stream as well as 2kb down-stream regions of the TERT-CLPTM1L gene loci). Using a method described previously with the sample size inflation factor, Rh2, of ≥ 0.8, fifteen htSNPs were selected with Haploview 4.2 software on a block-by-block basis (Supplementary Table S2).

TERT-CLPTM1L htSNPs were genotyped through the MassArray system (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, California, USA). A 5% blind, random DNA samples was analyzed in duplicates and the reproducibility was 99%. To reduce the costs of the study, we genotyped the TERT-CLPTM1L rs2853691 A>G, rs2736100 T>G and rs451360 G>T SNPs in two validation sets using the PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) as described in Supplementary Table S3. A 5% samples were genotyped by two investigators and the reproducibility was 98.0%.

Luciferase reporter gene constructs

Specific primer pairs (Supplementary Table S4) with the KpnI and XhoI restriction sites were used to amplify the intron 2 segment of TERT (chr.5: 1319429∼1319865 bp [GRCh38.p2] including the rs2736100 flanking region) from human genomic DNA carrying TERT rs2736100 TT genotype or GG genotype. Similarly, the intron 16 segment of CLPTM1L (chr.5: 1285954∼1286844 bp [GRCh38.p2] including the rs451360 flanking region) was amplified with human genomic DNA carrying CLPTM1L rs451360 GG genotype or TT genotype. The PCR products were then digested with KpnI and XhoI (New England Biolabs) and ligated into an appropriately digested pGL3-Basic vector (TERT) or pGL3-Promoter vector (CLPTM1L). The resultant TERT reporter gene plasmids were designated pTERT-T or pTERT-G, which were only different at rs2736100 polymorphic site. The resultant CLPTM1L reporter gene plasmids were named as pCL-T or pCL-G, which were identical except for the different allele at rs451360 polymorphic site. Restriction analysis and complete DNA sequencing confirmed the orientation and integrity of these constructs.

Dual luciferase reporter assays

KYSE30 and KYSE150 ESCC cells were transfected with both reporter constructs (pGL3-Basic, pTERT-T, pTERT-G, pGL3-Promoter, pCL-T or pCL-G) and pRL-SV40 (Luciferase Assay System; Promega). Dual luciferase activities were determined at 48h after transfection as previously described [46,47]. For each plasmid construct, three independent transfection experiments were performed, and each was done in triplicates.

Real-time analysis of TERT and CLPTM1L mRNA

Total cellular RNA was isolated from sixty-six pairs of ESCC specimens and esophagus normal tissues adjacent to the tumors with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and converted to cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TAKARA). TERT and CLPTM1L mRNA expression in cancerous and normal esophagus tissues was examined using the TaqMan real-time quantity PCR method. Relative gene expression quantization for TERT (ABI, Assay ID Hs00972656_m1) and CLPTM1L (ABI, Assay ID Hs00363947_m1) was calculated using β-actin (ABI, Assay ID 4333762T) as an internal reference gene was carried out using the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system in triplicates.

Statistics

Pearson's χ2 test was used to examine the differences in demographic variables, smoking status, drinking status, and genotype distributions of rs2853691, rs2736100 or rs451360 SNP between ESCC cases and healthy controls. The associations between rs2853691, rs2736100 or rs451360 genotypes and ESCC risk were estimated by odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals computed by logistic regression models. All ORs were adjusted for age, sex, smoking or drinking status, where it was appropriate. A P value of less than 0.05 was used as the criterion of statistical significance, and all statistical tests were two-sided. All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc.).

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES

Footnotes

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by the National High-Tech Research and Development Program of China (2015AA020950); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271382, 91229126 and 81201586); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YS1407); the open project of State Key Laboratory of Molecular Oncology (SKL-KF-2015-05); Beijing Higher Education Young Elite Teacher Project (YETP0521); Innovation and Promotion Project of Beijing University of Chemical Technology.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Y, Broderick P, Webb E, Wu X, Vijayakrishnan J, Matakidou A, Qureshi M, Dong Q, Gu X, Chen WV, Spitz MR, Eisen T, Amos CI, et al. Common 5p15.33 and 6p21.33 variants influence lung cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1407–1409. doi: 10.1038/ng.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKay JD, Hung RJ, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Chabrier A, Byrnes G, Zaridze D, Mukeria A, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, Fabianova E, Mates D, et al. Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15. 33. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1404–1406. doi: 10.1038/ng.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broderick P, Wang Y, Vijayakrishnan J, Matakidou A, Spitz MR, Eisen T, Amos CI, Houlston RS. Deciphering the impact of common genetic variation on lung cancer risk: a genome-wide association study. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6633–6641. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landi MT, Chatterjee N, Yu K, Goldin LR, Goldstein AM, Rotunno M, Mirabello L, Jacobs K, Wheeler W, Yeager M, Bergen AW, Li Q, Consonni D, et al. A genome-wide association study of lung cancer identifies a region of chromosome 5p15 associated with risk for adenocarcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Zhu B, Zhang M, Parikh H, Jia J, Chung CC, Sampson JN, Hoskins JW, Hutchinson A, Burdette L, Ibrahim A, Hautman C, Raj PS, et al. Imputation and subset-based association analysis across different cancer types identifies multiple independent risk loci in the TERT-CLPTM1L region on chromosome 5p15. 33. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6616–6633. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafnar T, Sulem P, Stacey SN, Geller F, Gudmundsson J, Sigurdsson A, Jakobsdottir M, Helgadottir H, Thorlacius S, Aben KK, Blöndal T, Thorgeirsson TE, Thorleifsson G, et al. Sequence variants at the TERT-CLPTM1L locus associate with many cancer types. Nat Genet. 2009;41:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ng.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stacey SN, Sulem P, Masson G, Gudjonsson SA, Thorleifsson G, Jakobsdottir M, Sigurdsson A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sigurgeirsson B, Benediktsdottir KR, Thorisdottir K, Ragnarsson R, Scherer D, et al. New common variants affecting susceptibility to basal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:909–914. doi: 10.1038/ng.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Yang B, Li B, Liu Y. Association between TERT-CLPTM1L rs401681[C] allele and NMSC cancer risk: a meta-analysis including 45,184 subjects. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:49–52. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB, Dobbins SE, Sanson M, Malmer B, Simon M, Marie Y, Boisselier B, Delattre JY, Hoang-Xuan K, El Hallani S, Idbaih A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:899–904. doi: 10.1038/ng.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman N, Garcia-Closas M, Chatterjee N, Malats N, Wu X, Figueroa JD, Real FX, Van Den Berg D, Matullo G, Baris D, Thun M, Kiemeney LA, Vineis P, et al. A multi-stage genome-wide association study of bladder cancer identifies multiple susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:978–984. doi: 10.1038/ng.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen GM, Amundadottir L, Fuchs CS, Kraft P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Jacobs KB, Arslan AA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Gallinger S, Gross M, Helzlsouer K, Holly EA, Jacobs EJ, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies pancreatic cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q22.1, 1q32.1 and 5p15.33. Nat Genet. 2010;42:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turnbull C, Rapley EA, Seal S, Pernet D, Renwick A, Hughes D, Ricketts M, Linger R, Nsengimana J, Deloukas P, Huddart RA, Bishop DT, Easton DF, et al. Variants near DMRT1, TERT and ATF7IP are associated with testicular germ cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2010;42:604–607. doi: 10.1038/ng.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haiman CA, Chen GK, Vachon CM, Canzian F, Dunning A, Millikan RC, Wang X, Ademuyiwa F, Ahmed S, Ambrosone CB, Baglietto L, Balleine R, Bandera EV, et al. A common variant at the TERT-CLPTM1L locus is associated with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1210–1214. doi: 10.1038/ng.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beesley J, Pickett HA, Johnatty SE, Dunning AM, Chen X, Li J, Michailidou K, Lu Y, Rider DN, Palmieri RT, Stutz MD, Lambrechts D, Despierre E, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the TERT promoter are associated with risk of serous epithelial ovarian and breast cancers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kote-Jarai Z, Olama AA, Giles GG, Severi G, Schleutker J, Weischer M, Campa D, Riboli E, Key T, Gronberg H, Hunter DJ, Kraft P, Thun MJ, et al. Seven prostate cancer susceptibility loci identified by a multi-stage genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2011;43:785–791. doi: 10.1038/ng.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolquist KA, Ellisen LW, Counter CM, Meyerson M, Tan LK, Weinberg RA, Haber DA, Gerald WL. Expression of TERT in early premalignant lesions and a subset of cells in normal tissues. Nat Genet. 1998;19:182–186. doi: 10.1038/554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuo J, Wang DH, Zhang YJ, Liu L, Liu FL, Liu W. Expression and mechanism of PinX1 and telomerase activity in the carcinogenesis of esophageal epithelial cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:1823–1831. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu HP, Xu SQ, Lu WH, Li YY, Li F, Wang XL, Su YH. Telomerase activity and expression of telomerase genes in squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:99–104. doi: 10.1002/jso.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James MA, Wen W, Wang Y, Byers LA, Heymach JV, Coombes KR, Girard L, Minna J, You M. Functional characterization of CLPTM1L as a lung cancer risk candidate gene in the 5p15. 33 locus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James MA, Vikis HG, Tate E, Rymaszewski AL, You M. CRR9/CLPTM1L regulates cell survival signaling and is required for Ras transformation and lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1116–1127. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia J, Bosley AD, Thompson A, Hoskins JW, Cheuk A, Collins I, Parikh H, Xiao Z, Ylaya K, Dzyadyk M, Cozen W, Hernandez BY, Lynch CF, et al. CLPTM1L promotes growth and enhances aneuploidy in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2785–2795. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang R, Chen X, Zhang S, Zhang X, Li T, Liu Z, Wang J, Zang W, Wang Y, Du Y, Zhao G. Upregulation of miR-494 Inhibits Cell Growth and Invasion and Induces Cell Apoptosis by Targeting Cleft Lip and Palate Transmembrane 1-Like in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1247–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao YT, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Benichou J, Dai Q, Fraumeni JF., Jr Risk factors for esophageal cancer in Shanghai, China. I. Role of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:192–196. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu J, Nyrén O, Wolk A, Bergström R, Yuen J, Adami HO, Guo L, Li H, Huang G, Xu X, et al. Risk factors for oesophageal cancer in northeast China. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:38–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C, Wang Z, Song X, Feng XS, Abnet CC, He J, Hu N, Zuo XB, Tan W, Zhan Q, Hu Z, He Z, Jia W, et al. Joint analysis of three genome-wide association studies of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese populations. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1001–1006. doi: 10.1038/ng.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C, Kraft P, Zhai K, Chang J, Wang Z, Li Y, Hu Z, He Z, Jia W, Abnet CC, Liang L, Hu N, Miao X, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese identify multiple susceptibility loci and gene-environment interactions. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1090–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu C, Hu Z, He Z, Jia W, Wang F, Zhou Y, Liu Z, Zhan Q, Liu Y, Yu D, Zhai K, Chang J, Qiao Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in Chinese populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:679–684. doi: 10.1038/ng.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang LD, Zhou FY, Li XM, Sun LD, Song X, Jin Y, Li JM, Kong GQ, Qi H, Cui J, Zhang LQ, Yang JZ, Li JL, et al. Genome-wide association study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese subjects identifies susceptibility loci at PLCE1 and C20orf54. Nat Genet. 2010;42:759–763. doi: 10.1038/ng.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Hu N, Wang Z, Yu K, Shu XO, Yuan JM, Zheng W, Dawsey SM, Dong LM, Lee MP, Ding T, Qiao YL, et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:764–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machiela MJ, Hsiung CA, Shu XO, Seow WJ, Wang Z, Matsuo K, Hong YC, Seow A, Wu C, Hosgood HD, 3rd, Chen K, Wang JC, Wen W, et al. Genetic variants associated with longer telomere length are associated with increased lung cancer risk among never-smoking women in Asia: a report from the female lung cancer consortium in Asia. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:311–319. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinnersley B, Migliorini G, Broderick P, Whiffin N, Dobbins SE, Casey G, Hopper J, Sieber O, Lipton L, Kerr DJ, Dunlop MG, Tomlinson IP, Houlston RS, et al. The TERT variant rs2736100 is associated with colorectal cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1001–1008. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosrati MA, Willander K, Falk IJ, Hermanson M, Höglund M, Stockelberg D, Wei Y, Lotfi K, Söderkvist P. Association between TERT promoter polymorphisms and acute myeloid leukemia risk and prognosis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25109–25120. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campa D, Rizzato C, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Pacetti P, Vodicka P, Cleary SP, Capurso G, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Werner J, Gazouli M, Butterbach K, Ivanauskas A, Giese N, et al. TERT gene harbors multiple variants associated with pancreatic cancer susceptibility. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gago-Dominguez M, Jiang X, Conti DV, Castelao JE, Stern MC, Cortessis VK, Pike MC, Xiang YB, Gao YT, Yuan JM, Van Den Berg DJ. Genetic variations on chromosomes 5p15 and 15q25 and bladder cancer risk: findings from the Los Angeles-Shanghai bladder case-control study. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:197–202. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pande M, Spitz MR, Wu X, Gorlov IP, Chen WV, Amos CI. Novel genetic variants in the chromosome 5p15. 33 region associate with lung cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1493–1499. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xun X, Wang H, Yang H, Wang H, Wang B, Kang L, Jin T, Chen C. CLPTM1L genetic polymorphisms and interaction with smoking and alcohol drinking in lung cancer risk: a case-control study in the Han population from northwest China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e289. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang Y, Thakur A, Gao L, Wang T, Zhang S, Ren H, Meng J, Geng T, Jin T, Chen M. Correlation of CLPTM1L polymorphisms with lung cancer susceptibility and response to cisplatin-based chemjournalapy in a Chinese Han population. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12075–12082. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong R, Liu L, Zou L, Zhu Y, Chen W, Zhu B, Shen N, Rui R, Long L, Ke J, Lu X, Zhang T, Zhang Y, et al. Genetic variations in TERT-CLPTM1L locus are associated with risk of lung cancer in Chinese population. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52:E118–E126. doi: 10.1002/mc.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu SG, Ma L, Cen QH, Huang JS, Zhang JX, Zhang JJ. Association of genetic polymorphisms in TERT-CLPTM1L with lung cancer in a Chinese population. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:4469–4476. doi: 10.4238/2015.May.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu L, Zhou C, Zhou L, Peng L, Li D, Zhang X, Zhou M, Kuang P, Yuan Q, Song X, Yang M. Functional FEN1 genetic variants contribute to risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer and colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:119–123. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Zhou L, Fu G, Sun F, Shi J, Wei J, Lu C, Zhou C, Yuan Q, Yang M. The identification of an ESCC susceptibility SNP rs920778 that regulates the expression of lncRNA HOTAIR via a novel intronic enhancer. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2062–2067. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Tong L, Wei J, Pan W, Li L, Ge Y, Zhou L, Yuan Q, Zhou C, Yang M. The ALDH7A1 genetic polymorphisms contribute to development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12665–12670. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M, Xie W, Mostaghel E, Nakabayashi M, Werner L, Sun T, Pomerantz M, Freedman M, Ross R, Regan M, Sharifi N, Figg WD, Balk S, et al. SLCO2B1 and SLCO1B3 may determine time to progression for patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2565–2573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan W, Liu L, Wei J, Ge Y, Zhang J, Chen H, Zhou L, Yuan Q, Zhou C, Yang M. A functional lncRNA HOTAIR genetic variant contributes to gastric cancer susceptibility. Mol Carcinog. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mc.22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Wei J, Zhou L, Zhou C, Shi J, Yuan Q, Yang M, Lin D. A functional BRCA1 coding sequence genetic variant contributes to risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2309–2313. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.