Abstract

The heterogeneity of group data can obscure a significant effect of an intervention due to differential baseline scores. Instead of discarding the seemingly heterogeneous response set, an orderly lawful relationship could be present. Rate dependence describes a pattern between a baseline and the change in that baseline following some intervention. To highlight the importance of analyzing data from a rate-dependent perspective, we 1) briefly review research illustrating that rate-dependent effects can be observed in response to both drug and non-drug interventions in varied schedules of reinforcement in clinical and preclinical populations; 2) observe that the process of rate-dependence likely requires multiple parts of a system operating simultaneously to evoke differential responding as a function of baseline; and 3) describe several statistical methods for consideration and posit that Oldham's correlation is the most appropriate for rate-dependent analyses. Finally, we propose future applications for these analyses in which the level of baseline behavior exhibited prior to an intervention may determine the magnitude and direction of behavior change and can lead to the identification of subpopulations that would be benefitted. In sum, rate dependence is an invaluable perspective to examine data following any intervention in order to identify previously overlooked results.

Keywords: Baseline, Data Analysis, Intervention, Oldham, Rate dependence

1. Introduction

“You take the blue pill – the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill – you stay in Wonderland and I'how you how deep the rabbit hole goes”

In the movie the Matrix the hero, Neo, is presented with a choice between a world he has always believed in and a world that is completely different. Often scientists may be seeking a cure for some disorder and may conclude that the intervention has no effect. However, sometimes the absence of an effect may be hiding an alternative explanation. Sidman (1960) observed that two individuals may have opposing responses to the same independent variable and suggested that researchers are dismissing a valuable controlling variable: differential baseline rates of behavior. Moreover, perhaps the heterogeneity of group data obscures a significant effect of an intervention in participants with the lowest or highest initial baseline rates. In this case, an intervention may actually be an efficacious therapy for a specific subset of the tested population and the study a worthwhile endeavor. Thus, in an effort to highlight the importance of analyzing the data from all angles, re-examining data from a rate-dependent perspective should not be overlooked.

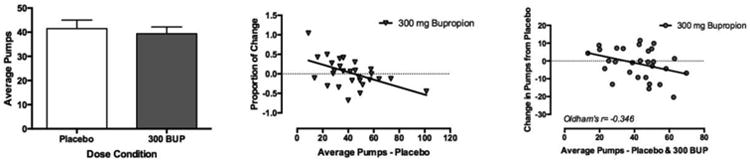

Consider a dataset1 using the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) in which participants were asked to inflate incrementally a computerized balloon image. Each pump would earn the participant a set amount of money provided the balloon did not pop. The participant could choose to stop pumping at any time, bank the earnings, and move to the next trial. If the balloon popped, no money was earned for that trial. The published dataset found no effect of Bupropion (300 mg) on responding during the BART when compared to placebo in a within-subject study (Acheson and de Wit 2008). When the data from this task were re-analyzed as a function of average pumps under placebo conditions, average pumps following 300 mg Bupropion administration changed rate dependently. Figure 1 depicts the same data set in three important iterations. The left-most graph depicts the group average pumps following placebo and 300 mg Bupropion administrations. The middle graph illustrates the traditional representation of the proportion of change in average pumps (i.e., (drug pumps - placebo pumps)/ placebo pumps) as a function of responding under placebo conditions. The right-most graph represents Oldham's correlation (a statistical method to determine rate dependence described in detail below) between the change in responding from placebo to drug and the average of responding under both conditions. Here, while there is clearly no difference between group responding under placebo and drug (see left-most graph), the middle graph illustrates that participants who performed fewer average pumps under placebo performed proportionally more following drug administration; while participants who pumped more under placebo performed proportionally less following Bupropion. This re-analysis explicitly illustrates the idea that drugs can differentially affect individuals based on placebo responses. Oldham's correlation of these data (see right-most graph) determined that this effect is indeed rate dependent and highlights how examining data in a different way may reveal a valuable orderly relationship.

Figure 1.

Example of a concealed rate-dependent effect using clinical data from Acheson and de Wit (2008). The left-most graph illustrates no main effect in average balloon pumps following drug administration (300 mg Bupropion) when investigating group differences from placebo (n=29). The middle graph depicts the traditional method of representing proportion of change as a function of performance under placebo. The right-most graph depicts the re-analysis of raw data contributed by the authors utilizing Oldham's method. A rate-dependent relationship is present wherein the proportion of change in pumps (i.e., (drug pumps – placebo pumps)/placebo pumps) following administration of 300 mg Bupropion (middle; n=29), was dependent on the pumps under placebo conditions. The presence of rate dependence was not determined by the regression line depicted in the middle graph, but instead was determined using Oldham's correlation (r = -0.346 for 300 mg Bupropion; right-most graph).

This orderly relationship is referred to as rate dependence and describes a pattern between a baseline or initial value and the change in that behavior following some intervention (Dews 1977). That is, the level of the behavior exhibited prior to an intervention determines, in part, the magnitude and direction of behavior change. Theoretically, several quantitative relationships qualify as rate dependent (Barrett and Katz 1981a) however, the most frequently observed rate-dependent effect is an inverse relationship between the baseline rate of behavior and rates of responding following an intervention (Dews and Wenger 1977; Perkins 1999; Bickel et al. 2014a). Depending upon the baseline value, increases, decreases, and/or no change in behavior can occur following intervention. The greater literature has since generally accepted the idea that a correlation between baseline (x) and change from baseline (x-y) or the log of the proportion of baseline (x/y) and the log of baseline (x) represents the relationship between baseline value and change (as noted by Benjamin 1967). However, as previously suggested (Jin 1992) and expanded on below, inherent biases in analyzing within-subject change scores exist with this methodology.

Previous research has shown that rate-dependent effects can be observed in response to drug administration and non-drug interventions in varied schedules of reinforcement in both clinical and preclinical populations (Dews 1958b; Dews 1977; Branch 1984; Bickel et al. 1988; Bickel et al. 2014a; Bickel et al. 2015b). While this paper is not intended to be an exhaustive literature review, it will review the relevant history of rate dependence, suggest possible mechanisms, highlight the importance of the analysis methods, and conclude with the assertion that awareness of this phenomenon is crucial amongst scientists performing intervention research. Of note, while this phenomenon has been illustrated in dependent measures beyond response rates, throughout the manuscript we refer to the concept of an inverse relationship between a baseline value and the change in that value following some intervention as rate dependence to maintain consistency with the historical literature.

2. History and Current Status of Rate Dependence

While the idea of rate dependence has been widely acknowledged within the psychological and pharmacological literature, the law of initial value, first defined by Wilder (1967, p. viii), describes a relationship in the data that may have been a relative of the rate dependence phenomenon. The law of initial value theorizes that the magnitude and direction of a response following some intervention can be predicted by an organism's pre-stimulus response. That is, when the initial value is high, responses post-stimulus are smaller, while when initial value is low responses post-stimulus can be larger.

The emergence of behavioral pharmacology ignited the explicit definition and dissemination of the concept of rate dependence to the greater scientific community. Early investigations studying drug effects on schedule-controlled behavior determined that drugs have a unique effect on different rates of responding, which are often dependent upon the reinforcement schedule (Dews 1958a; Dews 1958b; Dews and Wenger 1977), where the interaction between drugs and schedules of control differentially influence the drug effect. For example, Dews found that chlorpromazine and promazine had different effects during portions of the interval in fixed-interval2 schedules based upon the previous component of the schedule. The differences in response rates over the course of the interval have been used as baseline measures in studies investigating the effects of drugs on responding and provide a convenient baseline to observe rate-dependent effects (Branch 1984).

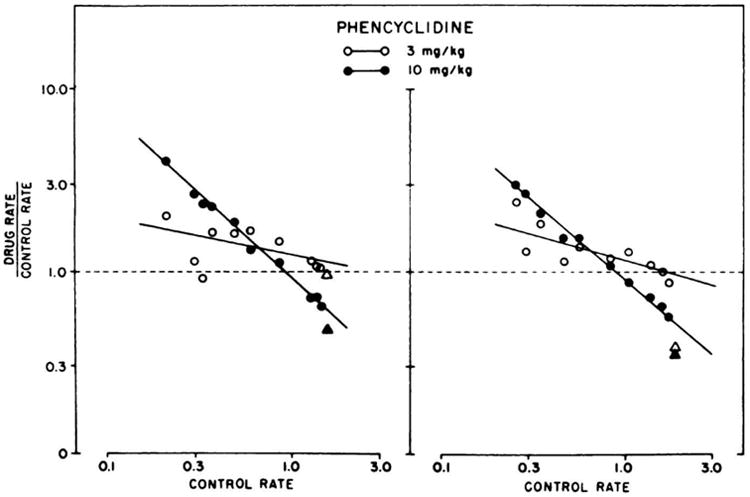

The typical inverse rate-dependent relationship was first illustrated by behavioral pharmacological studies administering amphetamines (Dews 1958b; Barrett and Katz 1981b; Goudie 1985), nicotine (Stitzer et al. 1970), and other stimulant-like compounds (Goudie 1985) using simple schedule-controlled manipulations of baseline performance. Rate dependence can also be observed when behavior is maintained on complex schedules of reinforcement. When using more complex, multiple3 or conjunctive4 schedules with fixed-interval and fixed-ratio components to induce different baseline rates of behavior, the effects of phencyclidine (PCP), ketamine, pentobarbital, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, chlorpromazine, imipramine, and d-amphetamine were also dependent upon response rate in the absence of drug (McMillan 1973; Barrett 1974; Wenger and Dews 1976; Leander 1981; Newland and Marr 1985). For example, PCP (see Figure 2) and ketamine administration increased low baseline rates while high baseline rates either decreased or did not change (Wenger and Dews 1976) during a multiple schedule, illustrating that different compounds differentially changed behavior contingent on nitial rates of responding. Moreover, rate dependence was also demonstrated in healthy adults and children along with hyperactive children following amphetamine administration (Robbins and Sahakian 1979). Again, fortifying the notion that rate dependence is observed following administration of a variety of pharmacological agents in simple and complex reinforcement schedules in the preclinical and clinical literature all dependent on initial response rates.

Figure 2.

Demonstration of rate dependence by Wenger and Dews (1976) following administration of PCP (3 and 10 mg/kg) in mice.

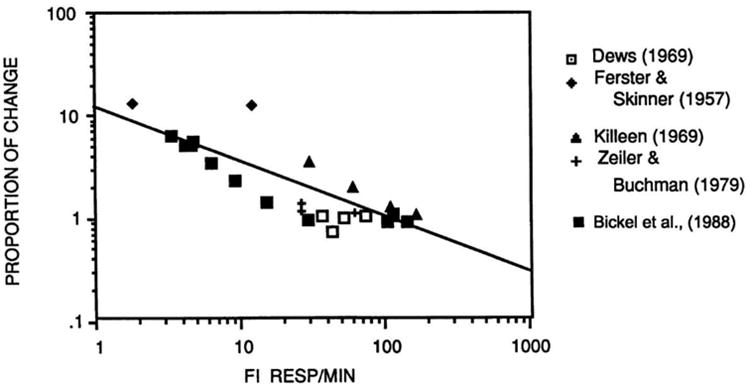

In contrast to drugs acting as the manipulated agent, the interaction of schedule-controlled behavior with other types of interventions can produce rate-dependent relationships. For example, rate-dependent results have been demonstrated among squirrel monkeys using white noise as the intervention (Howell et al. 1986). Additionally, the quantitative signature of rate dependence can be observed when a new schedule of reinforcement is imposed as an intervention. Specifically, introducing a tandem5 fixed-interval fixed-ratio schedule following a history of fixed-ratio (i.e., high response rates) or IRT >t-s schedule (i.e., low response rates), resulted in rate-dependent effects; that is, responding was not altered among those rats with a history of fixed-ratio schedules, while response rates were increased among those rats with a history of IRT >t-s schedules (Bickel et al. 1988) illustrating that non-pharmacological interventions can differentially modify previously established baseline responding. In the same study data from four other preclinical reports were re-analyzed and plotted with the data from the tandem fixed-interval fixed-ratio reinforcement schedule (Bickel et al. 1988). Collectively these data, shown in Figure 3, indicate that baseline performance is inversely related to responding following the same intervention.

Figure 3.

Results from five studies using tandem fixed-interval fixed-ratio reinforcement schedules that were re-analyzed by Bickel et al. (1988) illustrating rate dependence in a majority of the studies.

Rate dependence also occurred following a variety of manipulations including addiction therapies in humans within the decision-making literature. In a study utilizing a delay discounting procedure, which measures preference between immediate and future monetary options, participants with high rates of baseline discounting (i.e., higher valuation of immediate rewards) decreased their rate of discounting following several types of interventions and treatments (Bickel et al. 2014a). The paper investigated a total of 222 participants combined from six different studies with various treatment modalities and found evidence of a rate-dependent change following three of the six manipulations. These three manipulations were described as: (1) working memory training, (2) buprenorphine treatment in addition to counseling as usual, and (3) buprenorphine treatment in addition to a contingency management procedure. When data were analyzed as a function of baseline rate of responding, a rate-dependent effect was observed. That is, those with the highest baseline discounting rates decreased most after active working memory training and the buprenorphine treatment. These results support the idea that investigating the data as a function of baseline performance can reveal lawful orderly relationships that may not be otherwise recognized.

More recently, a review and re-analysis investigating the effects of stimulant compounds on preclinical and clinical impulsivity measures found rate-dependent effects that were not previously reported as such (Bickel et al. 2015b). More specifically, a total of 82 instances from 25 research reports were re-analyzed. Of those instances, 67% demonstrated evidence consistent with rate dependence. Greater evidence of this effect was demonstrated in the preclinical studies, perhaps due to larger sample sizes and greater control over extraneous variables. However, rate dependence was observed in over half of the cases from the clinical studies, consistent with incidence observed by Bickel et al. (2014a).

Other recent studies support the notion that the pattern of rate dependence within the data may be present in arenas other than behavior. For example, an inverse relationship of baseline dopamine D2/3 receptor density in the ventral and dorsal striatum was observed following 28 days of oral methylphenidate administration in rats (Caprioli et al. 2015). Moreover, transcranial magnetic stimulation, a non-invasive neural modulation technique, rate dependently affected anterior cingulate cortex activity in alcohol-dependent individuals (Herremans et al 2016). Overall these recent results suggest that rate dependence is not limited to basic science, preclinical studies, or even response rates.

3. Mechanistic hypotheses

A precise mechanism for the phenomenon of rate dependence is unknown. We briefly present possible explanations and assert that rate dependence may be a process that requires one or more of the following mechanisms. One possible mechanism is, the idea that any novel or extra stimulus could act to change the environment to either increase or decrease a conditioned response without training (Pavlov 1927). Pharmacological agents, especially psychoactive drugs, can act as stimulus conditions including unconditioned and extra stimuli producing both specific drug effects (i.e., acting as an unconditioned stimulus) and non-specific subjective effects (i.e., acting as the extra stimulus; Dews 1962; Schuster and Balster 1977). Another mechanistic explanation includes the inverted-U-shaped dopamine action hypothesis (Levy 2009; Arnsten 2009), which proposes that stimulant administration differentially affects dopamine levels and corresponding behaviors depending on the initial baseline. That is, stimulant administration increases catecholamines (including dopamine) and adrenergic activation to the maximum levels of the inverted-U-shaped function in individuals with low baselines; whereas, no change or decreases in dopamine activity or behavior following stimulant administration can occur in those with high baseline dopamine levels (Cools and D'Esposito 2011). A third interpretation of rate dependence is based on the competing neurobehavioral decision systems (CNDS) theory, which describes opposing executive and impulsive decision systems that ideally function in regulatory balance (Bickel et al. 2007; Bickel et al. 2015c). Regulatory imbalance between the systems is associated with self-control impairments (Bickel et al. 2010) that could be restored following an intervention based on initial baseline behaviors. Specifically, increases in low baseline levels of activation of the executive decision system or decreases in high baseline levels of the impulsive decision system can occur following some intervention producing greater regulatory balance. While these three potential mechanisms may provide some explanation, we suggest that rate dependence is an emergent process caused by a complex interaction of these mechanisms and other unidentified processes. An emergent phenomenon is one that cannot be reduced to the properties of its smallest parts. Instead, the individual components interact in an orderly and lawful way to create a product greater than the sum of its parts (Mitchell 2009). The phenomenon of rate dependence likely requires multiple mechanisms operating simultaneously to evoke orderly responding. Greater sophistication of contemporary research methods may permit an examination of rate dependence as an emergent phenomenon by actively testing the parameters under which we observe it.

4. Analysis of rate dependence

Historically, rate dependence has been evaluated via the relationship between x (i.e., baseline value) and x - y (i.e., change post-intervention) using either graphical representation (Barrett 1974; Wenger and Dews 1976; McKim 1981) or a standard correlation or linear regression (see Tu et al. 2005). Equation 1 represents this relationship,

| (1) |

The correlation of baseline value and change score most often generates a negative relationship, in which low initial values increase, high initial values decrease, and intermediate baseline values remain constant. However, the correlation or linear regression between these two variables in this relationship introduces two specific confounds: mathematical coupling and regression to the mean.

Oldham (1962) described a method to test for a differential effect of initial value post intervention that is most often used in dental (Müller 2007; Blance et al. 2007) and medical (Bland and Altman 1986; Tu et al. 2004; Browne et al. 2010) research, and at least twice in psychological research (Baschnagel and Hawk 2008; Bickel et al. 2015b). His method annuls both confounds inherent in the former equation: mathematical coupling and regression to the mean. Mathematical coupling is when one variable consists of all or part of another variable, which results in artificially inflated associations when determining correlations (Oldham 1962). For example, when x and y are two random numbers with the same standard deviation, the correlation of x and x-y generates a strong relationship of approximately 0.71 (Oldham 1962). Thus, when correlating x and x-y, the null hypothesis that the correlation would be zero is erroneous. The second confound nullified by Oldham's method, regression to the mean, is a change in the variation due to repeated measurements most often seen as a product of measurement error for the baseline value (Tu and Gilthorpe 2007). Instead, to accurately test for rate dependence the most appropriate strategies are to: 1) use Oldham's method or 2) modify the null hypothesis and test using Fisher's z transformation (Tu and Gilthorpe 2007, both methods described in detail below).

Oldham proposed a method in which change from baseline value is measured using variables that are not dependent on each other. An important feature of this method is that it can determine whether there is a rate-dependent treatment effect independent of mathematical coupling and regression to the mean. This is assessed through Equation 2:

| (2) |

where x is the baseline measure, y is the post-treatment measure, s2x is the variance of x, and s2y is the variance of y. The correlation between x and y is rxy (Tu and Gilthorpe 2007). More simply stated, the correlation (rmean(x,y), y-x) between the change score and the average responses of pre- and post-measures of an intervention can be used to determine if a relationship between the variables exists independent of mathematical coupling and regression to the mean. Oldham's correlation protects against those confounds (Blance et al. 2007) by eliminating the correlation between x and y in the numerator of the traditional method. Instead, Equation 2 tests the difference between the variance of the pre- and post-measures and determines the effect of initial value on change by the magnitude of the correlation. If the correlation equals zero, there is no baseline-dependent effect. A guideline for determining a relationship consistent with rate dependence via the magnitude of the correlation has been suggested before (Browne et al. 2010; Bickel et al. 2015b) using a magnitude of r = 0.3 based on a medium effect size derived from Cohen (1992).

More recently, at least four alternative methods to analyze rate dependence and one expansion on the premise of Oldham's method have been proposed (Hayes 1988; Tu et al. 2004; Tu et al. 2005; Tu and Gilthorpe 2007). Our intent is to briefly describe the alternatives and their function. Previous work has mathematically compared the alternatives to each other, therefore we refer the reader to the following for nuanced discussions and detailed analyses (Bland and Altman 1986; Hayes 1988; Tu et al. 2004; Tu et al. 2005; Blance et al. 2005; Tu and Gilthorpe 2007; Browne et al. 2010).

First, the variance-ratio test and structural regression, which account for mathematical coupling and regression to the mean, test the equivalence of the variances between the correlated variables (i.e., baseline value and change score) resulting in a t-statistic. These methods and Oldham's method are both based on the same assumptions (Tu and Gilthorpe 2007) and thus, often produce the same results. Oldham's method, however, provides more information about effect size by producing a correlation coefficient (Tu et al. 2004), thus Oldham's method provides more quantitative information.

Second, Blomqvist's formula has been proposed as similar to Oldham's (Hayes 1988), and the better of the two methods has been debated in the literature. Each method, however, answers a different research question and accounts for different mathematical biases. First, Blomqvist's formula measures the size of a change following an intervention. However, unlike Oldham's methods and contrary to Hayes' (1988) assertions, this equation does not identify differential effects of treatment on heterogeneous baseline values (Tu and Gilthorpe 2007). This point is important for researchers attempting to identify rate dependence. Second, while the equation used to produce Oldham's correlation eliminates the biases caused by regression to the mean and mathematical coupling, Blomqvist's method only accounts for regression to the mean.

Third, Tu et al. (2005) identified that if Equation 1 is the preferred method used to determine rate dependence then testing a new null hypothesis is required. The authors proposed a method in which to alter the null hypothesis, given the data. Then Fisher's z transformation normally distributes the correlation coefficients derived from the new null calculation and Equation 1. These normally distributed correlation coefficients are used to calculate a standard z-score. To determine rate dependence, the z-score significance level is identified using a z-table. This method was compared to Oldham's and the traditional method using re-analyzed data from the literature. Both Oldham's method and testing a new null hypothesis identified the same four datasets as rate dependent. Moreover, they found a false positive significance level in 60% of those datasets using Equation 1 highlighting the importance for awareness of the biases associated with Equation 1.

Fourth, although seldom used in the contemporary literature a simple comparison of the response rates under drug condition plotted as a function of response rates under baseline on log-log axes was first mathematically presented by (Gonzalez and Byrd 1977). In their conceptualization, a slope of -1 indicated a drug effect is independent of baseline rates; whereas a slope approaching 0 indicated a rate-dependent relationship between drug and baseline rates (Gonzalez and Byrd 1977). A similar concept, rate constancy, emerged where a rate-dependent consistent effect is observed when the slope of the linear regression approaches 0 (Howell et al. 1986). These approaches remove mathematical coupling inherent in the traditional rate-dependent analyses by eliminating the presentation of baseline rates in both the ordinate and abscissa. Moreover, they do not involve complicated mathematics and therefore may be a potential avenue for preliminary analyses. Despite these advantages, (Gonzalez and Byrd 1977) specify that comparisons between individuals and/or procedures cannot be conducted without the knowledge of maximum response rates, which is only theoretically calculable. These approaches of simply plotting the data may reveal patterns, however, they do not include a statistical method to determine the presence of rate dependence.

Though these alternative approaches may be useful in some research endeavors, Oldham's method is simple to understand, easy to calculate, and provides more quantitative information about the relationship between initial values and change than the methods described above. Oldham's method, however, is not without weaknesses. That is, Oldham's method cannot be used to analyze three or more repeated measurements or incorporate possible covariates. One recent expansion of this method, multilevel modeling, has been proposed to account for both of these weaknesses, because it allows for multiple repeated measurements and potential covariates when necessary (Blance et al. 2005; Tu and Gilthorpe 2007; Müller 2007; Blance et al. 2007). While multilevel modeling adds value by increasing power and complexity, it also has limitations. The modeling approach, while accounting for mathematical coupling, does not account for regression to the mean (Blance et al. 2007) though this can be overcome if error variance is measured and included in the model (Blance et al. 2005; Blance et al. 2007).

5. Conclusion

Rate dependence describes an orderly relationship that is largely overlooked in the literature resulting in a publication bias and unfortunate dismissal of data that don a genuine lawful intervention effect. Historically, basic preclinical research established a method to manipulate baseline response rates using reinforcement schedules and demonstrated similar differential effects across many manipulations and drug classes. Clinical researchers validated the generalization of rate dependence to human populations and across task modalities. This generalization suggests a mechanism such that any environmental intervention may result in a signature pattern of responding if differential baseline performance is present. Thus, investigating the data in such a way to identify changes in differential responses to a treatment within subjects is important. The mathematical problems and biases inherent in investigating rate-dependent relationships in the traditional way (i.e., change as a function of baseline) have hindered the acceptance of rate dependence as more than just a description of the data. Statistics accounting for those problems, mathematical coupling and regression to the mean, are necessary to determine whether an actual intervention effect exists in the data. Here, we describe several statistical methods for consideration and posit that Oldham's correlation is the most appropriate for rate-dependent analyses.

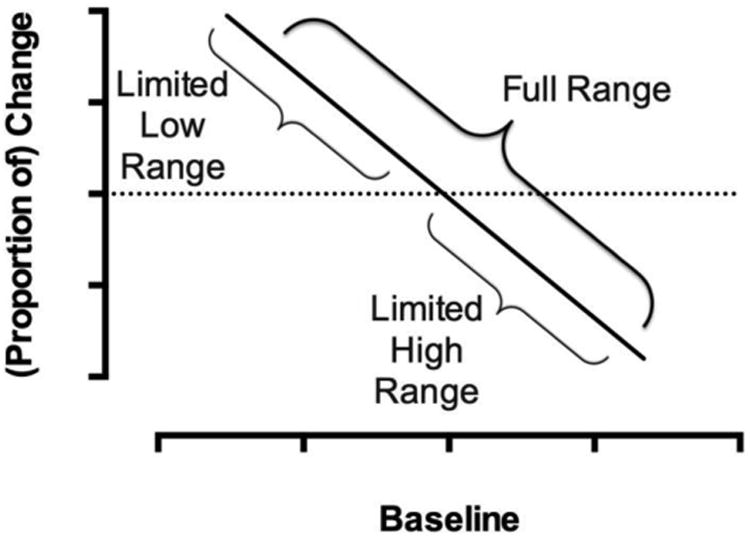

When examining data in this way, three limitations should be acknowledged (Gonzalez and Byrd 1977; McKearney 1981; Branch 1984). First, random sampling could limit the range of baseline values exhibited, thus the sample may not have the full parameter variation in baseline values necessary to observe a complete distribution of the inverse rate-dependent relationship. A full inverse relationship, however, is not required for rate dependence to be operative. Instead, two limited range types (see Figure 4) can also illustrate this quantitative signature (Bickel et al. 2015b). That is, when the high range of baseline values is sampled, a limited high range effect can be revealed where the highest baseline rates are decreased and the lowest baseline rates sampled do not change. The opposite, a limited low range effect, occurs when the lowest baseline rates can be increased while no change occurs at the highest sampled baseline rates. If, however, a very small portion of baseline values is sampled, rate dependence may not be depicted (see Dews (1969) and Zeiler and Buchman (1979) data in Figure 3). Second, limits of change (Dews 1981; Bickel et al. 2015a) exist such that in tasks with response rate or percent correct as the primary dependent variable, the rate cannot be less than zero and the percent correct cannot be greater than 100 (Dews 1981), therefore limiting the range of variability available for change to occur.

Figure 4.

A hypothetical figure illustrating rate dependence and defining the ranges of baseline values as described in Bickel et al. (2015a) and indicating that rate dependence can occur in instances in which a limited range of baseline values are present.

Third, the boundary conditions of rate dependence are unknown. For example, whether all types of dependent variables, independent variables, and populations could operate in a rate-dependent fashion should be investigated and could expand the reach and applicability of this approach. No evidence exists to suggest that the observed effect is fundamentally limited to any behavior or task at this time. Measures in types of impulsivity tasks (e.g., accuracy, prepotent responses, and discounting), have shown this quantitative signature (Bickel et al. 2015b). In fact, a review describing the baseline-dependent effects of nicotine on rate of responding in addition to myriad other variables in both preclinical and clinical data sets highlights the relevance of rate dependence in a variety of indices (Perkins 1999). A body of literature demonstrating nicotine's rate dependent-like effects on alternative measures including cognitive tasks, self-reported arousal, and mood were also reviewed (Perkins 1999). Dews and Wenger (1977) even investigated other operant response measures (e.g., latency) by transforming the variables into response-rate like numbers, and the orderly relationship was observed. Thus, our previous reviews and current paper support the notion that rate dependence is a robust phenomenon describing a quantitative signature in the data within the greater literature spanning many treatment and measurement modalities.

Our review of the literature and report that rate dependence is operative in a variety of instances suggests its value for future use. For example, identifying rate of responding in a short, inexpensive delay discounting procedure could be used to identify those who are more likely to respond with a positive outcome to a specific treatment regime (Bickel et al. 2014b). If we know a rate-dependent relationship exists between delay discounting and some intervention (e.g., working memory training), we could predict direction of change post-intervention. In this case, individuals with low discounting values (i.e., self-controlled individuals) will not change or increase discounting rate (i.e., weaken self-control) after intervention. This intervention, then, should not be used for an individual with initially low discounting values. Instead, this intervention should only be used for individuals with initially high discounting values as rate dependence predicts a decrease in discounting rate (i.e., increased self-control). The level of change in delay discounting may also be a marker of treatment efficacy (Bickel et al. 2014b) as demonstrated by the rate-dependent relationship that was observed in opioid-dependence treatment trials with verified therapeutic efficacy based on biological outcome measures (Bickel et al. 2014a). Therefore, in addition to the identification of subpopulations that would benefit, this method could also be used to identify those who may need adjunctive therapy to improve the outcome of moderately efficacious treatments. In sum, rate dependence is an invaluable perspective in which to examine data from any treatment or intervention. Perhaps, by using this perspective we, like Neo, will be able to see a world that is completely different, but lawful, orderly, and dependent.

Highlights.

Rate dependence can discern intervention effects that might otherwise be concealed

The rate dependence phenomenon exists in preclinical and clinical historical data

The mechanism of rate dependence is unknown however likely an emergent process

Oldham's correlation is most appropriate for basic rate-dependent analyses

Acknowledgments

Funding: R01DA034755, R01AA021529

Footnotes

The authors, Acheson and de Witt (2008), graciously provided the raw data for this task and gave permission for its use in this manuscript.

A schedule of reinforcement that evokes initially low responding, which increases over each interval and is often described as a scallop. Reinforcers are delivered after a specific amount of time has passed.

A multiple schedule is a compound schedule in which two or more components alternate and are each associated with a unique stimulus. Reinforcers are delivered after completion of any one component.

A conjunctive schedule is a compound schedule in which two or more components must be satisfied prior to delivery of a reinforcer.

A tandem schedule is a compound schedule of reinforcement in which two or more successive components in the presence of only one stimulus must be completed prior to delivery of the reinforcer.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acheson A, de Wit H. Bupropion improves attention but does not affect impulsive behavior in healthy young adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:113–23. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT. Toward a new understanding of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pathophysiology: an important role for prefrontal cortex dysfunction. CNS Drugs. 2009;23 Suppl 1:33–41. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J, Katz J. Drug effects on behaviors maintained by different events. Adv Behav …. 1981a;3:119–168. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JE. Conjunctive schedules of reinforcement. I. Rate-dependent effects of pentobarbital and d-amphetamine. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;22:561–73. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JE, Katz JL. Drug Effects on Behaviors Maintained by Different Events. In: Thompson T, Dews PB, McKim WA, editors. Advances in Behavioral Pharmacology. Academic Press; New York: 1981b. pp. 119–163. [Google Scholar]

- Baschnagel JS, Hawk LW. The effects of nicotine on the attentional modification of the acoustic startle response in nonsmokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LS. Facts and artifacts in using analysis of covariance to “undo” the law of initial values. Psychophysiology. 1967;4:187–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1967.tb02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Higgins ST, Kirby K, Johnson LM. An inverse relationship between baseline fixed-interval response rate and the effects of a tandem response requirement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1988;50:211–218. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish aD. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014a. A Quantitative Signature of Self-Control Repair: Rate-Dependent Effects of Successful Addiction Treatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, et al. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90 Suppl 1:S85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Quisenberry AJ, Moody L, Wilson aG. Therapeutic Opportunities for Self-Control Repair in Addiction and Related Disorders: Change and the Limits of Change in Trans-Disease Processes. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014b doi: 10.1177/2167702614541260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Quisenberry AJ, Moody L, Wilson AG. Therapeutic Opportunities for Self-Control Repair in Addiction and Related Disorders: Change and the Limits of Change in Trans-Disease Processes. Clin Psychol Sci a J Assoc Psychol Sci. 2015a;3:140–153. doi: 10.1177/2167702614541260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Quisenberry AJ, Snider SE. Does impulsivity change rate dependently following stimulant administration? A translational selective review and re-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015b doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4148-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Snider SE, Quisenberry AJ, et al. Competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory of cocaine addiction: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Progress in Brain Research. 2015c doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Mueller ET, et al. The behavioral economics of drug dependence: towards the consilience of economics and behavioral neuroscience. Curr Top Behav eurosci. 2010;3:319–41. doi: 10.1007/7854_2009_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blance A, Tu YK, Baelum V, Gilthorpe MS. Statistical issues on the analysis of change in follow-up studies in dental research. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:412–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blance A, Tu YK, Gilthorpe MS. A multilevel modelling solution to mathematical coupling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2005;14:553–565. doi: 10.1191/0962280205sm418oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland MJ, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;327:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch MN. Rate dependency, behavioral mechanisms, and behavioral pharmacology. 1984;3:511–522. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne JP, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey JD, et al. Mathematical coupling may account for the association between baseline severity and minimally important difference values. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:865–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli D, Jupp B, Hong YT, et al. Dissociable rate-dependent effects of oral methylphenidate on impulsivity and D2/3 receptor availability in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2015;35:3747–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3890-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A Power Primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, D'Esposito M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e113–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews P. Rate-dependency hypothesis. Science (80-) 1977;198:1182–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.563103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. Effects of chlorpromazine and promazine on performance on a mixed schedule of reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1958a;1:73–82. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. Psychopharmacology. In: Bachrach AJ, editor. Experimental foundations of clinical psychology. Basic Books; New York: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. Studies on responding under fixed-interval schedules of reinforcement: the effects on the pattern of responding of changes in requirements at reinforcement1. J Exp nal Behav. 1969;12:191–199. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. History and present status of rate-dependency investigations. Adv Behav Pharmacol. 1981;3:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. Studies on behavior. IV. Stimulant actions of methamphetamine. J pharamacology Exp Ther. 1958b;122:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB, Wenger GR. Rate-Dependency of the Behavioral Effects of Amphetamine. In: Thompson T, Dews PB, editors. Advances in behavioral pharmacology. Vol. 1. Academic Press, Inc; New York: 1977. pp. 167–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez FA, Byrd LD. Methematics underlying the rate-dependency hypothesis. Science (80-) 1977;195:546–550. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ. Comparative effects of cathinone and amphetamine on fixed-interval operant responding: a rate-dependency analysis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:355–365. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RJ. Methods for assessing whether change depends on initial value. Stat Med. 1988;7:915–927. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Byrd LD, Marr MJ. Similarities in the rate-altering effects of white noise and cocaine. J Exp Anal Behav. 1986;46:381–394. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.46-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P. Toward a reconceptualization of the law of initial value. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:176–184. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leander J. Drug effects on multiple and alternating mixed-schedule performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;218:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy F. Dopamine vs noradrenaline: inverted-U effects and ADHD theories. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:101–108. doi: 10.1080/00048670802607238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKearney JW. Rate dependency: Scope and Limitations in the Explanation and Analysis of the Behavioral Effects of Drugs. In: Thompson T, Dews PB, McKim WA, editors. Advances in Behavioral Pharmacology. Academic Press; New York: 1981. pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- McKim WA. Rate-dependency: A nonspecific behavioral effect of drugs. Adv Behav Pharmacol. 1981;3:16–71. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DE. Drugs and punished responding. I. Rate-dependent effects under multiple schedules. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973;19:133–45. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.19-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SD. Unsimple Truths: Science, Complexity, and Policy. University of Chicago Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Müller HP. A bivariate multi-level model, which avoids mathematical coupling in the study of change and initial periodontal attachment level after therapy. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11:307–10. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland MC, Marr MJ. The effects of chlorpromazine and imipramine on rate and stimulus control of matching to sample. J Exp Anal Behav. 1985;44:49–68. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.44-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham PD. A note on the analysis of repeated measurements of the same subjects. J Chronic Dis. 1962;15:969–977. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(62)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP. Conditioned reflexes. New York: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Baseline-dependency of nictoine effects: a review. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10:597–615. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199911000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. “Paradoxical” effects of psychomotor stimulant drugs in hyperactive children from the standpoint of behavioural pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 1979;18:931–950. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster CR, Balster RL. The discriminative stimulus properties of drugs. Adv Behav Pharmacol. 1977;1:85–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Tactics of scientific research: Evaluating experimental data in psychology. Basic Books; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer M, Morrison J, Domino EF. Effects of nicotine on fixed-interval behavior and their modification by cholinergic antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;171:166–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YK, Baelum V, Gilthorpe MS. The relationship between baseline value and its change: problems in categorization and the proposal of a new method. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:279–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YK, Maddick IH, Griffiths GS, Gilthorpe MS. Mathematical coupling can undermine the statistical assessment of clinical research: illustration from the treatment of guided tissue regeneration. J Dent. 2004;32:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YK, Gilthorpe MS. Revisiting the relation between change and initial value: A review and evaluation. Stat Med. 2007;26:443–457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger GR, Dews PB. The effects of phencyclidine, ketamine, d-amphetamine and pentobarbital on schedule-controlled behavior in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;196:616–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder J. Stimulus and Response: The Law of Initial Value. John Wright & Sons Limited; Bristol: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler MD, Buchman IB. Response requirements as constraints on output. J Exp Anal Behav. 1979;32:29–49. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1979.32-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]