Abstract

Ras GTPases are activated by RasGEFs and inactivated by RasGAPs, which stimulate the hydrolysis of RasGTP to inactive RasGDP. GTPase-impairing somatic mutations in RAS genes, such as KRASG12D, are among the most common oncogenic events in metastatic cancer. A different type of cancer Ras signal, driven by overexpression of the RasGEF RasGRP1 (Ras guanine nucleotide-releasing protein 1), was recently implicated in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) patients and murine models, in which RasGRP1 T-ALLs expand in response to treatment with interleukins (ILs) 2, 7 and 9. Here, we demonstrate that IL-2/7/9 stimulation activates Erk and Akt pathways downstream of Ras in RasGRP1 T-ALL but not in normal thymocytes. In normal lymphocytes, RasGRP1 is recruited to the membrane by diacylglycerol (DAG) in a phospholipase C-γ (PLCγ)-dependent manner. Surprisingly, we find that leukemic RasGRP1-triggered Ras-Akt signals do not depend on acute activation of PLCγ to generate DAG but rely on baseline DAG levels instead. In agreement, using three distinct assays that measure different aspects of the RasGTP/GDP cycle, we established that overexpression of RasGRP1 in T-ALLs results in a constitutively high GTP-loading rate of Ras, which is constantly counterbalanced by hydrolysis of RasGTP. KRASG12D T-ALLs do not show constitutive GTP loading of Ras. Thus, we reveal an entirely novel type of leukemogenic Ras signals that is based on a RasGRP1-driven increased in flux through the RasGTP/GDP cycle, which is mechanistically very different from KRASG12D signals. Our studies highlight the dynamic balance between RasGEF and RasGAP in these T-ALLs and put forth a new model in which IL-2/7/9 decrease RasGAP activity.

INTRODUCTION

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive cancer associated with poor prognosis, especially after disease relapse (reviewed in Aifantis et al.1). The current line of treatment consists of cytotoxic chemotherapy with many side effects. Potential targeted treatment requires detailed understanding of the leukemogenic signals.

Despite being extremely aggressive in vivo, leukemic blasts grow very poorly in vitro unless supplemented with bone marrow stromal cells or exogenous cytokines. Cytokines such as interleukin-7 (IL-7) or IL-2 produced by bone marrow stromal cells and which signal through the common γ-chain receptor are contributing to the survival and proliferation of leukemic blasts.2–4 We have recently reported that a Ras activator, RasGRP1, cooperates with cytokines to drive leukemogenesis in T-ALL, highlighting RasGRP1 as one critical component.5

RasGRP1 belongs to the RasGRP (Ras guanine nucleotide-releasing protein) family of proteins that act as nucleotide exchange factors for Ras (reviewed in Ksionda et al.6). RasGRP1 expression is best described in immune cells: it is highly abundant in T cells and to lesser extent in B, NK and mast cells. RasGRP1 is critical in the regulation of thymocytes as RasGRP1-deficient mice exhibit a profound T-cell developmental block,7 whereas dysregulation of RasGRP1 expression leads to T-ALL in various mouse models and is frequently observed in pediatric T-ALL patients.5,6,8–10 The molecular connections between cytokine receptors, RasGRP1, and downstream effectors in the Ras pathway have remained undefined.

The canonical RasGRP1-Ras signaling pathway has been best studied in the context of T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. In short, TCR crosslinking results in the activation of a signaling cascade involving several kinases (namely, Lck and Zap70) and assembly of a signaling complex containing the adaptor molecule LAT. LAT has several tyrosine sites, which serve as docking sites for phospholipase C-γ1 (PLCγ1), among other molecules. Upon activation, PLCγ1 converts membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphate to release two secondary messengers: diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-triphosphate. Inositol-triphosphate initiates cytoplasmic calcium flux (reviewed in Feske et al.11), whereas DAG recruits RasGRP1 to the membrane via binding to the C1 domain of RasGRP1 and recruits members of protein kinase C kinase family, notably protein kinase Cθ, which can phosphorylate RasGRP1 to further enhance its function to catalyze GDP to GTP exchange on Ras (reviewed in Ksionda et al.6).

Our recent biophysical and cellular signaling work provided more details into the mechanisms of RasGRP1 regulation and activation.12 RasGRP1’s crystal structure revealed that this RasGEF exists in an autoinhibited, dimeric state. A calcium-induced conformational change releases RasGRP1 from its autoinhibition and allows for binding of the C1 domain to DAG and for binding of Ras to RasGRP1’s catalytic pocket. Our insights from the RasGRP1 structure, RasGRP1’s overexpression in T-ALL and the novel RasGRP1-dependent cytokine-induced Ras activation recently identified in T-ALL5 inspired us to investigate the mechanism of RasGRP1-Ras signals in cytokine-responsive T-ALL.

RESULTS

Cytokine-induced Ras activation is unique to T-ALL

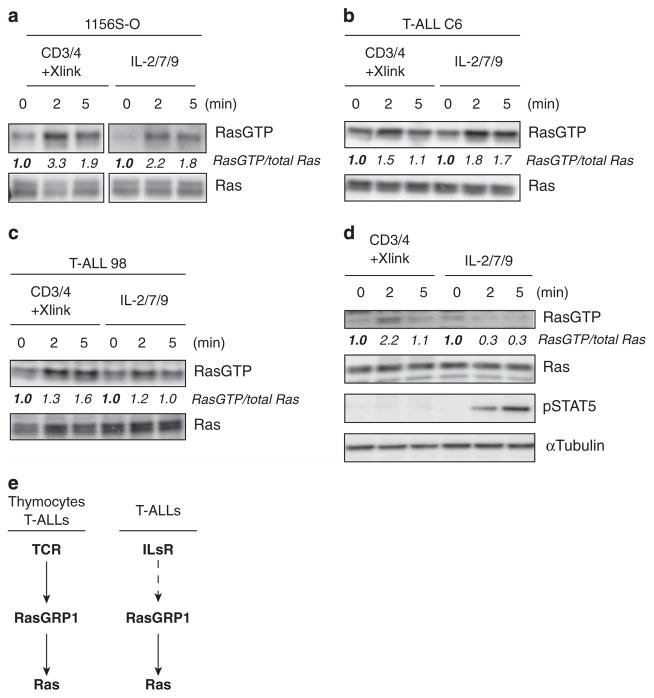

T-ALL cell lines with high RasGRP1 expression robustly activate Ras when stimulated with cytokines in a RasGRP1-dependent manner,5 pointing to a potential cytokine receptor-RasGRP1-Ras pathway. To compare directly the effects of TCR versus cytokine stimulation on Ras activation, we stimulated two T-ALL lines (1156S-O and T-ALL C6 cell lines) that express high levels of RasGRP15 by either crosslinking CD3 and CD4 (TCR stimulation) or by exposure to a cocktail of IL-2, -7 and -9 (cytokine stimulation; ILs) and subjected cells to RasGTP pulldown assays. Both types of stimuli demonstrated roughly similar increases in RasGTP levels when analyzed side by side (Figures 1a and b). As comparison, we subjected a different T-ALL cell line (98) to the same assay. T-ALL line 98 does not overexpress RasGRP1 nor has it any leukemia virus insertions in genes that are known to influence the Ras pathway.5 As shown in Figure 1c, T-ALL 98 cells do accumulate some RasGTP upon IL stimulation, albeit to much lesser extent as lines that overexpress RasGRP1.

Figure 1.

Cytokine-induced Ras activation is unique to T-ALL. (a–d) Western blot analysis of Ras pulldown assays performed either in Rasgrp1 T-ALL cell lines (a and b), non-RasGRP1-overexpressing T-ALL cell line 98 (c) or primary thymocytes (d). Cells were serum starved and treated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 followed by crosslinking antibodies or stimulated with IL-2/7/9 for the indicated amount of time. The abundance of RasGTP was arbitrarily set at 1.0 for 0 min time point by normalizing RasGTP to the abundance of total Ras. Phospho-STAT5 is shown in (d) as a control for cytokine stimulation efficiency. All panels in this figure are representative examples of three independent experiments. (e) Scheme depicting activation of TCR-RasGRP1-Ras pathway in thymocytes and T-ALL cells as well as IL-RasGRP1-Ras, which in contrast to the first pathway seems to be unique to T-ALLs.

Based on cell surface marker expression, T-ALL blasts resemble developing thymocytes.1,5 Therefore, we next investigated if normal thymocytes also use the IL-RasGRP1-Ras pathway. In contrast to our T-ALL cell lines, ex vivo thymocytes activated Ras after TCR stimulation but not following exposure to cytokines (Figure 1d). Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 phosphorylation (pSTAT5), a well-characterized signal induced by cytokine receptors containing the common γ-chain, is shown here as a positive control to demonstrate proper IL-2/7/9 stimulation of thymocytes (Figure 1d). Therefore, T-ALL cells with RasGRP1 overexpression—and cell surface marker combinations reminiscent of developing thymocytes—have the unique ability to activate Ras in response to cytokine receptor stimulation (Figure 1e).

Distinct, RasGRP-1-dependent signals through the Akt pathway in cytokine-stimulated T-ALL

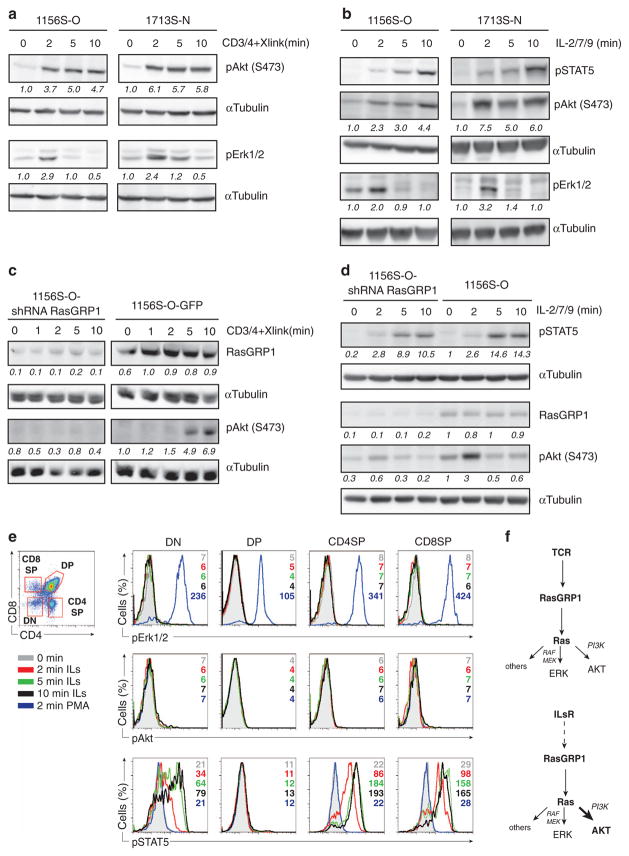

RasGTP signals to various effector kinase pathways to exert its cell biological effect on survival and proliferation.13 To compare effector activation following ILR-RasGRP1 versus ‘canonical’ TCR-RasGRP1 signals, we exposed T-ALLs with high RasGRP1 to each of the stimuli and examined the activation status of two well-characterized Ras effectors, Erk1/2 and PI3K. TCR stimulation resulted in transient Erk1/2 and sustained Akt phosphorylation (phospho-Akt serving as a surrogate for PI3K activation) in T-ALLs (Figure 2a). Cytokines (IL-2, -7 and -9) activated the PI3K/Akt pathway in T-ALL cells to a similar degree as TCR stimulation, whereas activity through the RasGTP-Raf-MEK-Erk pathway was modest (Figure 2b). As before, phosphorylation of STAT5 was measured as a positive control for IL stimulation (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

TCR and cytokines trigger RasGRP1-Ras effector pathways in T-ALL. (a and b) Western blot analysis of phospho-Akt (S473) and phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) in Rasgrp1 T-ALL cell lines stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 antibodies followed by crosslinking (a) or cytokines (b) for indicated amount of time. The abundance of phosphoprotein was arbitrarily set at 1.0 for 0 min time point by normalizing to the abundance of α-tubulin. Phospho-STAT5 (Tyr 694) was used as a control for stimulation efficiency in cytokine-treated samples. (c and d) Western blot analysis of phospho-Akt (S473) and RasGRP1 abundance in 1156S-O-GFP (control) and 1156-S-O cell lines where RasGRP1 knockdown was achieved via stable expression of RasGRP1 shRNA. Cells were either treated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 followed by crosslinking antibodies (c) or stimulated with cytokines (d) for the indicated amount of time. Phospho-STAT5 (Tyr 694) was used as a control for stimulation efficiency in cytokine-treated samples. Quantification was carried out as in (a) normalizing to the amount of α-tubulin. (e). Flow cytometry analysis of phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-Akt (S473) and phospho-STAT5 (Tyr 694) in wild-type thymocytes (from 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J females) stimulated with IL-2/7/9 or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA). Scatter plot on the left shows gating of double-negative (DN; CD4−CD8−), double-positive (DP; CD4+CD8+), CD8 and CD4 single-positive cells. Histograms on the right show levels of phosphoproteins in gated populations. Numbers represent values of geometric mean for the indicated time point. Figure shows one out of two experiments. Each experiment was performed with three mice. All panels in this figure are representative examples of two or three independent experiments. (f) Model of downstream Ras pathway activation through RasGRP1 after either TCR or cytokine stimulation.

Given that cytokines appear to preferentially trigger Ras-PI3K/Akt over Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk pathway in T-ALL, we sought to explore if TCR and IL-induced Akt activation depends on RasGRP1. We took advantage of previously generated cell lines with reduced RasGRP1 levels via stable expression of RasGRP1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA).5 Knockdown of RasGRP1 severely impairs both TCR- and IL-induced Akt phosphorylation without affecting cytokine-depending pSTAT5 levels (Figures 2c and d, respectively), revealing that activation of PI3K/Akt downstream of both receptor systems depends on RasGRP1.

Our RasGTP pulldown assay (Figure 1d) indicated that the IL-RasGRP1-Ras pathway is not functional in normal thymocytes. Thymocytes consist of four major subsets that reflect unique developmental stages and which differ in the expression levels of cytokine receptors (immgen.org). It is possible that only a minor population of cells activates Ras and Ras effector pathways downstream of cytokine receptors and that this signal is missed because of the detection limitations of the experimental method that assays population averages. To overcome these limitations and to confirm that normal thymocytes do not activate Ras and its effectors downstream of cytokine receptors, we took advantage of flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analysis of signaling events induced by TCR stimulation, similar to ERK phosphorylation, has been used by many groups including our own.14 We first separated thymocytes into double-negative CD4−CD8−, double-positive CD4+ CD8+ and single-positive CD4+ or CD8+ cell populations (Figure 2e) where single-positive CD8+s were gated on TCRβhigh to exclude intermediate single-positive cells. Stimulation with IL-2/7/9 resulted in phosphorylation of STAT5 in all thymic subsets except double-positive cells, consistent with reported receptor expression levels (immgen.org) (Figure 2e, bottom panel). We then looked at the activation of pErk1/2 and pAkt as a surrogate measure of Ras activity. We did not observe increases in pErk or pAkt upon cytokine stimulation in any of the subsets, suggesting that Ras is not activated after cytokine receptor activation by IL-2/7/9 in normal thymocytes (Figure 2e, top and middle panel). All thymic populations increased pErk1/2 in response to phorbol myristate acetate stimulation (Figure 2e, top panel, blue histogram), which demonstrated that the lack of pErk induction after cytokine exposure was not due to technical inability to detect pErk.

Thus, both TCR- and ILR-triggered Ras effector pathways are operational in T-ALL cells, but cytokine stimulation triggers Akt activation more robustly than Erk activation and does so in a RasGRP1-dependent manner (Figure 2f). Based on these results, we hypothesized that mechanisms of RasGRP1-driven Ras activation may differ between TCR- and cytokine-stimulated T-ALL cells.

Cytokine receptor-RasGRP1-Ras signaling does not require acute PLCγ1 activation

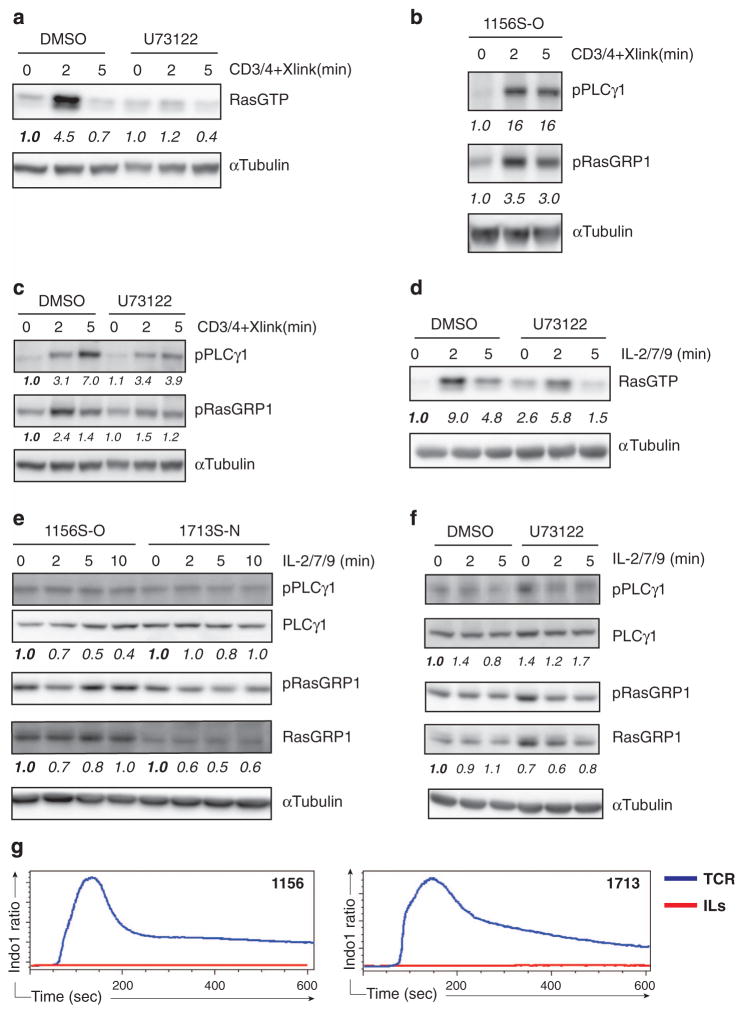

We next sought to explore if RasGRP1 couples to cytokine receptors in leukemic T-ALL via PLCγ1 as it does in canonical RasGRP1-Ras signaling induced by TCR stimulation. Pharmacological inhibition of PLCγ with a small-molecule inhibitor U73122 resulted in a profound decrease in RasGTP, confirming that TCR-induced RasGTP in T-ALL cells indeed depends on PLCγ1 activity (Figure 3a). In agreement with canonical RasGRP1 signaling, TCR stimulation resulted in induction of both PLCγ1 and RasGRP1 phosphorylation in T-ALL cells (Figure 3b) and TCR-induced RasGRP1 phosphorylation was decreased following PLCγ inhibitor treatment (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Cytokine receptor-RasGRP1-Ras signaling does not require acute PLCγ1 activation. (a and d) Western blot analysis of RasGTP pulldown performed in RasGRP1 T-ALL cell line (1156S-O) treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or PLCγ inhibitor (U73122, 20 μM), 30 min before stimulation with CD3/CD4 and crosslinking antibodies (a) or IL-2/7/9 (d). Note that the increase in RasGTP after U73122 treatment in the unstimulated, baseline condition in (d) was not a consistent finding. (b and c) Western blot analysis of phospho-PLCγ1 (Y783) and phospho-RasGRP1 (T184) in 1156S-O cell line. Cells were stimulated with CD3/CD4 and crosslinking antibodies. Samples were untreated (b) or treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or PLCγ inhibitor (U73122, 20 μM) 30 min before stimulation (c). (e and f) Western blot analysis of phospho-PLCγ1 (Y783) and phospho-RAsGRP1 (T184) in 1156S-O or 1713S-N T-ALL cell lines after stimulation with IL-2/7/9 for the indicated times (e). 1156S-O cells were treated with either DMSO (vehicle control) or PLCγ inhibitor (U73122, 20 μM) as described in (b) and (c). Note that the increase in pPLCγ1 after U73122 treatment in the unstimulated, baseline condition in (f) was not a consistent finding. The abundance of RasGTP or phosphoproteins was arbitrarily set at 1.0 for 0 min time point by normalizing to the abundance of α-tubulin, total PLCγ1 or RasGRP1, respectively. (g) Median ratio of Indo-1 violet/blue fluorescence as a measure of intracellular Ca2+ over time in 1156S-O (left panel) and 1713S-N (right panel) that were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD4 and crosslinking antibodies (blue trace) or with IL-2/7/9 (red trace). Cells were stimulated after 20 s baseline was recorded. All panels in this figure are representative examples of three independent experiments.

We next asked if similar second messengers connect RasGRP1 and cytokine receptors. In contrast to TCR stimulation where PLCγ inhibitor treatment almost completely abrogated RasGTP induction, we observed only a modest effect of the PLCγ inhibitor on cytokine-induced RasGTP (Figure 3d and Supplementary Figure 2). Consistent with the reduced requirement for acute PLCγ1 activation, cytokine treatment did not increase PLCγ1 or RasGRP1 phosphorylation above baseline levels in either of two T-ALL cell lines tested (Figure 3e). Also, pharmacological inhibition of PLCγ1 showed no effect on RasGRP1 phosphorylation following cytokine stimulation (Figure 3f). Of note, we avoided further increasing the concentration of the PLCγ inhibitor or extending the incubation time before stimulation, as these induced nonspecific cell toxicity.

The above data suggest that cytokines do not couple to PLCγ1; however, phosphorylation of PLCγ1 is only a surrogate for activation rather than a direct measurement of activity. To test more definitively that cytokine receptors do not induce PLCγ1 enzymatic activity in T-ALL cells, we evaluated rises in intracellular calcium as a direct effect of inositol-triphosphate production, which is a routine assay used by many to determine TCR-triggered calcium fluxes. Consistent with the data in Figures 3d and f, we did not observe any detectable increase in calcium levels upon cytokine stimulation, even within 10 min of recording (Figure 3g, red tracing), whereas TCR stimulation resulted in a rapid rise in intracellular calcium (Figure 3g; blue tracing). Taken together, these data demonstrate that while RasGRP1-overexpressing T-ALL cells maintain the ability to respond to TCR stimulation that requires PLCγ1 activation, the IL-RasGRP1-Ras pathway does not require receptor-induced PLCγ1 activity.

RasGRP1 couples to the cytokine receptor via basal DAG

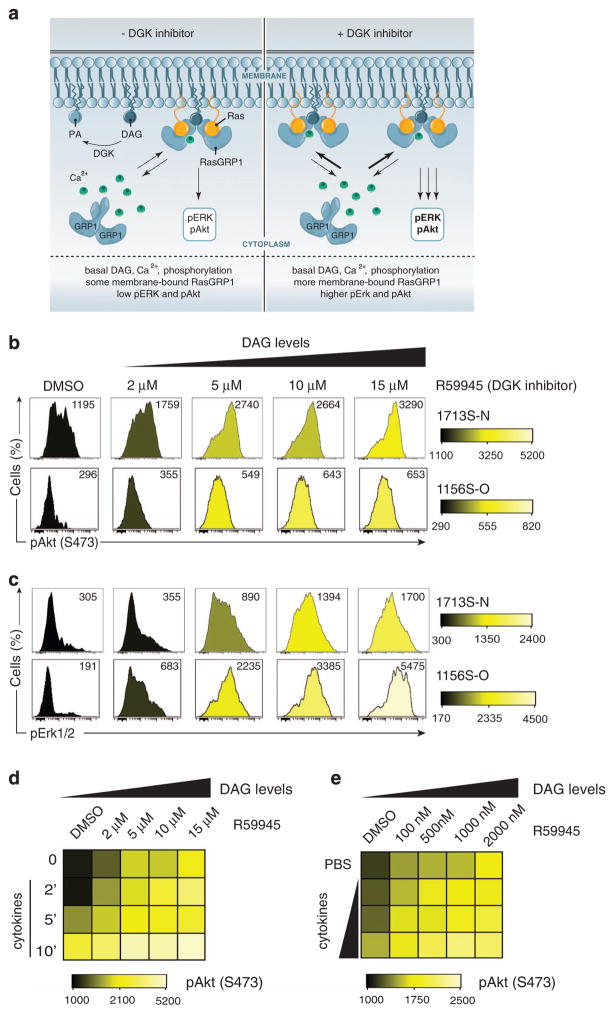

Binding of calcium to the EF hands of the RasGRP1 protein releases autoinhibition through allosteric changes.12 NMR scattering data indicates that autoinhibition of this RasGEF is not absolute and that there is some level of flexibility in the basal state without calcium signals12 (Figure 4a, left panel).

Figure 4.

RasGRP1 couples to the cytokine receptor via basal DAG. (a) Model of RasGRP1 in basal state. (Left) RasGRP1 exists in autoinhibited form but can use basal Ca2+, DAG to shuttle between the cytoplasm and membrane. DGK converts DAG to PA (phosphatidic acid). (Right) In the presence of DGK inhibitor, DAG is no longer converted to PA and accumulates at the membrane. As a consequence, more RasGRP1 is present at the membrane to activate Ras and its downstream effectors (figure by Anna Hupalowska, PhD). (b and c) Histograms showing phospho-Akt (S473) (b) and phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (c) in T-ALL cell lines (1156S-O and 1713S-N) treated with varying concentration of DGK inhibitor (R59945) for 30 min before analysis. DMSO-treated cells served as vehicle controls. Numbers represent median fluorescence intensities. A representative example of three independent experiments is shown. (d) Heatmap depicting phospho-Akt (S473) in 1713S-N T-ALL cell line treated with the DGK inhibitor, R59945, at indicated concentrations for 30 min before stimulation with IL-2/7/9 for the indicated duration in minutes. (e) Heatmap depicting phospho-Akt (S473) in 1713S-N T-ALL cell line treated with DGK inhibitor, R59945, at the indicated concentrations for 30 min before stimulation for 5 min with cytokines. IL-2/7/9 were used at various concentrations (1/10th standard, 1/5th standard, 1 × standard cytokine dilutions compared with concentrations of cytokines used throughout this study). Panels d and e are representative examples of two independent experiments completed in duplicate.

These structural aspects together with our observations that basal, low-level PLCγ1 and RasGRP1 phosphorylation can be detected in T-ALL cells (Figure 3e) prompted us to hypothesize that basal levels of DAG are sufficient for RasGRP1-dependent Ras activation in cytokine-stimulated T-ALL cells. To test this hypothesis, we used the DAG kinase (DGK) inhibitor R59945 to manipulate DAG levels without changing Ca2+ levels (Figure 4a, right panel). DGKs convert DAG to phosphatidic acid and pharmacological inhibition of DGK results in increased DAG levels15 and increased RasGTP in response to TCR stimulation.16

Treatment of T-ALL cells with DGK inhibitor (R59945) resulted in a dose-dependent induction of pAkt and pErk signals, in complete absence of cytokine receptor or other stimulatory input (Figures 4b and c). These findings are consistent with our previous mathematical modeling, which predicted that in the presence of high RasGRP1 concentration increasing DAG levels result in spontaneous Ras pathway activation.5 These results also reveal that overexpressed RasGRP1 couples to Ras in the basal state, without the requirement for receptor signals.

We subsequently asked if increased levels of baseline DAG could enhance cytokine-induced Ras effector activation. Indeed, we observed that cytokine-induced pAkt was increased after augmenting concentrations of DAG by treatment with DGK inhibitor (Figure 4d). Last, we investigated if low levels of cytokine input cooperates with increased baseline DAG levels and determined that R59945 concentrations as low as 100 nM potentiated cytokine-induced pAkt (Figure 4e). Taken together, these results indicate that when expressed at high levels, similar to a subset of T-ALL leukemias,5 RasGRP1 responds to baseline cellular levels of DAG to activate Ras effector pathways, which can be further induced by cytokine stimulation.

Broad coverage of expressed RasGAP molecules in T-ALL

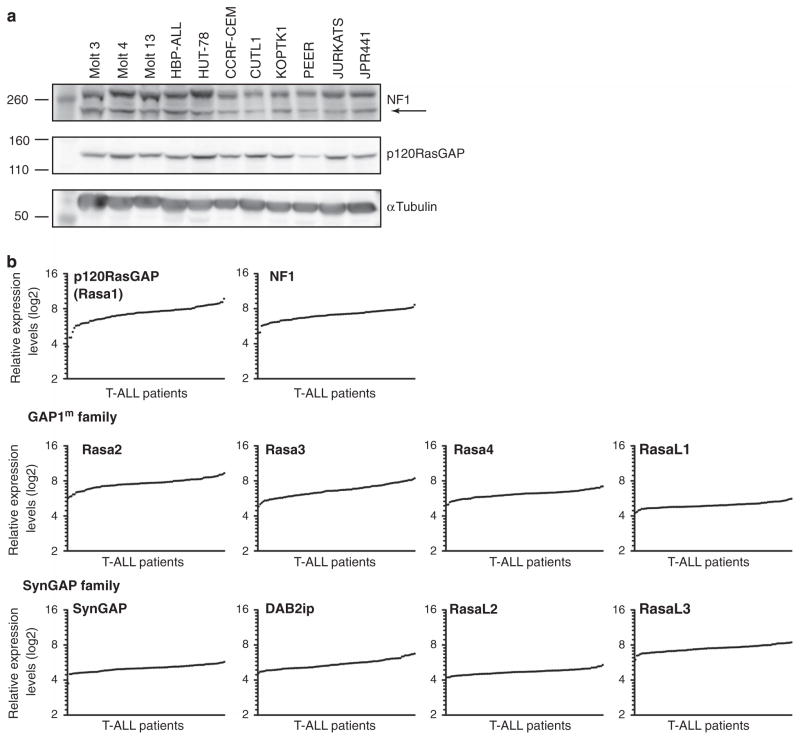

Given that our experiments in Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate that RasGRP1 couples to basal DAG, one would predict that T-ALL cells with RasGRP1 overexpression efficiently accumulate RasGTP in the unstimulated state. However, we previously established that RasGRP1 T-ALLs display only very modest increases in the basal levels of RasGTP. This contrasted the high levels of baseline RasGTP observed in T-ALL with oncogenic Ras mutations (such as KRasG12D) that render Ras protein insensitive to GAP action.5 Net RasGTP levels are the sum of GTP loading and GTP hydrolysis. We postulated that T-ALLs may contain high steady-state RasGAP activity to counteract the increased RasGRP1 activity in resting cells. To gain more insight into this equilibrium, we first looked at the expression of the two best characterized RasGAPs, NF1 and p120RasGAP. In a panel of 11 human T-ALL cell lines, all cell lines expressed both NF1 and p120RasGAP at roughly similar levels as determined by western blot analysis (Figure 5a). The Jurkat T-cell lymphoma and JPRM441 cell line, a Jurkat derivate expressing only 10% of normal RasGRP1 levels,17 revealed similar NF1 and p120RasGAP levels (Figure 5a), indicating that RasGRP1 does not influence expression levels of these RasGAPs.

Figure 5.

T-ALLs express many RasGAPs. (a) Western blot analysis of NF1 and p120RasGAP expression in a panel of human T-ALL cell lines. Arrow indicates NF1 band; the upper band is nonspecific. (b) Standard Affymetrix analysis was used to generate and normalize signal intensities of 10 RasGAP mRNA expression in samples from 100 pediatric T-ALL patients treated on COG studies 9404 and AALL0434. Values were RMA (robust multiarray average) normalized.

We reported that RasGRP1 reveals a large 128-fold range in mRNA expression levels among 107 primary T-ALL samples of pediatric patients.5 Here, we plotted mRNA levels for 10 RasGAP family members reported to be expressed in lymphocytes (King et al.,18 immgen.org) from the same microarray data of 107 T-ALL patients. We were struck to find that the primary samples expressed all RasGAP family members with only relatively small variations in mRNA expression between patients (Figure 5b). Additionally, expression of individual RasGAPs did not correlate with clinical outcome (Supplementary Figure 1). Given the above expression data and the critical biologic importance of tight regulation of RasGTP levels in cells, the regulation of the RasGTP-RasGDP equilibrium is unlikely to be regulated by a single RasGAP family member but more likely by combined RasGAP activity.

Increased RasGRP1 levels lead to high rate of flux through RasGDP/RasGTP cycle

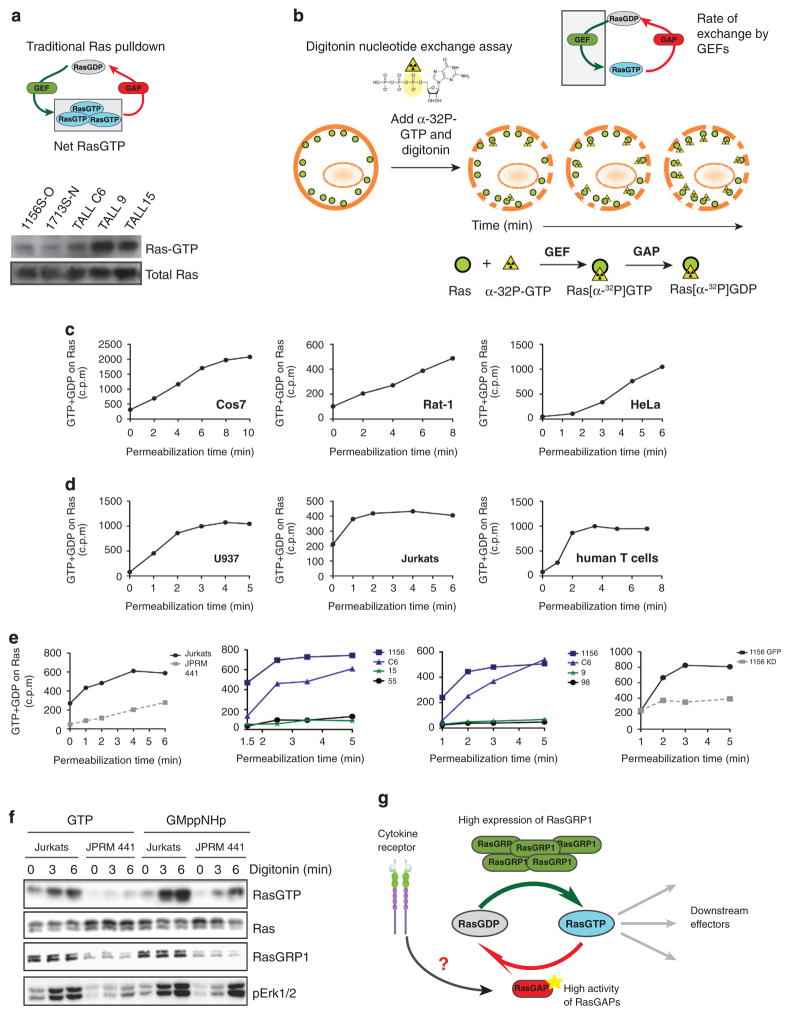

To investigate directly the equilibrium between RasGDP/GTP and the equilibrium between RasGEF and RasGAP activity in the setting of RasGRP1 overexpression, we compared and contrasted three distinct Ras assays.

First, we expanded on our published data with the traditional RasGTP pulldown assay, confirming that increased RasGRP1 expression does not result in high levels of RasGTP in the basal state, especially when compared with T-ALL cell lines that harbor KRasG12D mutation (Figures 6a).5 However, the pulldown assay does not provide any insights regarding the rate of RasGTP/GDP cycling (Figure 6a). To gain insight into the latter, we took advantage of a Ras nucleotide exchange assay19 to evaluate the rate of GTP loading (Figure 6b). Briefly, cells are permeabilized with digitonin to allow entry of radioactive α-phosphate-labeled GTP. This radiolabeled GTP is loaded onto Ras and can be hydrolyzed into RasGDP without loss of the radiolabeled nucleotide. Cells are lysed and Ras-bound radionucleotide is quantified and represents the amount of GTP loaded onto Ras as a function of time (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of RasGRP1 leads to high rate flux through RasGDP/RasGTP cycle. (a) Scheme of traditional Ras pulldown assay that measures net RasGTP levels and western blot analysis of RasGTP after Ras pulldown in RasGRP1 (1156S-O, 1713S-N and T-ALL C6) and KRasG12D (T-ALL 9, TALL15) T-ALL cell lines. (b) Scheme of digitonin exchange assay that measures loading of GTP into Ras. In short, cells are permeabilized with digitonin and loaded with radioactively labeled GTP nucleotide. GTP is labeled at the α position; therefore, after GAP-mediated hydrolysis, the radioactive label is not released and Ras-bound radioactivity accumulates over time. Ras is then immunoprecipitated and GTP loading quantified by scintillation counting. (c and d) Graphs depict rate of accumulation of radiolabeled guanine nucleotide in counts per minute that was loaded onto Ras in the basal state over time as measured with the digitonin exchange assay. Assays were carried out in a panel of cell lines that either do not express RasGRP proteins or have low expression of RasGRP1 and 3 (Cos7, Rat1, HeLa) (c) and compared with cell lines that express high levels of RasGRP1 or 4 (Jurkats, human T cells, myeloid U937) (d). (e) Accumulation of radiolabeled guanine nucleotide in counts per minute in resting cells on Ras as measured with the digitonin exchange assay in a panel of T-ALL cell lines. Left panel compares human T-ALL line, Jurkat and its derivative JPRM441, which express low levels of RasGRP1; two middle panels compare RasGRP1 T-ALL cell lines (1156, C6) with KRasG12D (T-ALL 15 and 9). Two T-ALL cell lines without known mutations in the Ras pathway (T-ALL 55 and 98) are shown as controls. Far right panel compares 1156S-O GFP cell line with 1156S-O cell line with stable shRNA-mediated knockdown of RasGRP1 (1156 KD).5 Panels c–e are representative examples at least two independent experiments. (f) Biochemical RasGTP determination in Jurkat T-ALL cell line and JPRM441 derivative expressing low levels of RasGRP1 treated with digitonin and loaded with either GTP or its non-hydrolyzable GTP analog GMppNHp for the indicated periods of time. (g) A proposed model elucidating a potential tumor suppressor role of RasGAPs in RasGRP1 T-ALL cells. Dysregulated RasGRP1 uses basal DAG to anchor to the membrane to perform exchange of GDP to GTP on Ras. High loading of GTP is counterbalanced by increased activity and/or expression of RasGAPs to hydrolyze GTP back to GDP and maintain low RasGTP levels. Cytokine receptor activation disrupts this cycle by acting on RasGAPs to decrease their activity resulting in the accumulation of RasGTP in the cell.

We first investigated loading of GTP into Ras in three non-immune cell lines (Cos7, Rat1 and HeLa), which lack or express low levels of RasGRP exchange factors.17,20,21 In agreement with previously reported data for Cos7 cells,21 all three cell lines show a slow rate of GTP loading and never reached plateau within the experimental time frame (Figure 6c). In contrast, in immune cells radioactivity levels quickly increased and were saturated at roughly 2 min, indicating that all Ras molecules had experienced one round of nucleotide exchange. This result confirms previous findings for T cells22,23 and suggests that immune cells that express RasGRP family members (RasGRP4 in U937 and RasGRP1 in Jurkat and human primary T cells; Roose et al.17) have exceptionally high basal rates of nucleotide exchange on Ras (some 30-fold higher than the intrinsic exchange rate of Ras24) (Figure 6d).

Focusing selectively on overexpression of RasGRP1 in leukemia, we find the rapid GTP loading in the Jurkat T-cell lymphoma line is dependent on this RasGEF as the rate of radionucleotide loading is significantly decreased in RasGRP1-deficient JPRM441 cells (Figure 6e, left graph). Similar to the results with Jurkat, murine T-ALL cell lines with high RasGRP1 expression (1156 and C6) revealed exceptionally high exchange rates with rapid accumulation of radioactive Ras and saturation of the experimental system within 2 min of incubation (Figure 6e, middle and right graph; blue lines). In contrast, two cell lines with GTPase-crippling KRasG12D mutations (T-ALL 15 and 9) had very slow exchange rates (Figure 6e, middle and right graph; green lines). Furthermore, two additional T-ALL cell lines that do not have any known insertions in genes involved in Ras signaling5 displayed slow rates of GTP loading onto Ras (Figure 6e, middle and right graph; black lines). To further prove the causal link between RasGRP1 and basal nucleotide exchange on Ras, we knocked down RasGRP1 in the high expressor line 1156S-O via shRNA. As shown in the far-right graph in Figure 6e, stable knockdown of RasGRP1 in the 1156S-O T-ALL line caused a marked reduction of nucleotide uptake by Ras that was not seen in the GFP control 1156S-O line, confirming that basal GTP loading of Ras in these T-ALL lines was driven by RasGRP1. Collectively, these data demonstrate that high levels of RasGRP1 expression in T-ALL cells lead to constitutively high nucleotide exchange rates on Ras.

These data again argue for equally high basal RasGAP activity in T-ALLs with RasGRP1 overexpression, given the minimally increased steady-state levels of RasGTP. As a third assay, we combined the permeabilization approach with the RasGTP pulldown assay. We reasoned that loading T cells with the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog GMppNHp should promote Ras activation solely via nucleotide exchange because RasGAP activity is futile against Ras-GMppNHp. As shown in Figure 6f, Jurkat cells permeabilized in the presence of GTP featured higher RasGTP levels compared with the low-RasGRP1 derivative JPRM441, in accordance with the notion that basal nucleotide uptake by Ras, as driven by RasGRP1, is a prerequisite for the accumulation of RasGTP. Importantly, when permeabilized in the presence of the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog, GMppNHp-active Ras accumulation rose markedly in Jurkat and also, albeit to a lesser extent, in JPRM441s. Although GMppNHp is certainly likely to affect the activity of other G proteins in the T cells, the simplest interpretation of these data was that resting T-ALL cells harbor high RasGAP activity, which is needed to balance the equally high basal nucleotide exchange on Ras driven by RasGRP1.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that the cytokine receptor-RasGRP1-Ras pathway is unique to T-ALL that overexpress RasGRP1, a feature observed in approximately half of pediatric T-ALL patients.5 We also provide evidence that dysregulated RasGRP1 uses basal DAG to anchor to the membrane, is already phosphorylated and therefore ‘primed’ to facilitate GDP/GTP exchange on Ras. In agreement, we uncovered constitutively high levels of GTP loading on to Ras that occurs exclusively in the setting of RasGRP1 overexpression.

Analysis of Ras effectors revealed that in cytokine-stimulated T-ALL, PI3K-Akt signals were more robustly induced than MEK/Erk. Interestingly, we observed a strong reduction in pAkt levels in T-ALL cell lines with RasGRP1 knockdown, and this effect was much more pronounced than previously reported in thymocytes (Figures 2c and d).25 The molecular mechanism for this differential sensitivity of pAkt compared with pErk is unknown. PI3K but not MEK is important for viability and cell cycle progression of T-ALL blasts.26 Our observation that RasGRP1 preferentially couples to PI3K-Akt signals combined with the fact that RasGRP1 is not ubiquitously expressed suggest that targeting RasGRP1 may prove to be an effective way to dampen PI3K signals in leukemic cells.

The collective results of our three distinct Ras assays reveal rapid nucleotide loading of GTP into Ras in T-ALL with RasGRP1 overexpression, suggesting that even without receptor input RasGRP1 can exert its function and the protein must ‘breathe’ enough to be released from its autoinhibited state and use cellular DAG and Ca2+ for full activation (Figure 6e). Based on mathematical modeling one consequence of high flux through RasGDP/GTP cycle at basal state would be much faster accumulation of RasGTP after receptor triggering as compared with the settings with low basal flux.24

In light of our experimental observations, we have proposed a model in which high loading of GTP into Ras by RasGRP1 is counterbalanced by RasGAP-mediated hydrolysis to keep RasGTP levels low under resting conditions (Figure 6g). Given that we found no evidence of cytokine-induced RasGRP1 activation (Figure 3e), it is a logical possibility that cytokines decrease RasGAP activity in the leukemic cell, ultimately resulting in RasGTP accumulation (Figures 1a and b and Figure 6g). It is possible that other receptor systems such as granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (reviewed in Ksionda et al.6) cooperate with RasGRP signaling in a similar manner. This mode of GTPase activation, that is, via receptor-induced inactivation of GAP, has been recently shown for Rheb, a Ras-related GTPase, and some evidence points out that it may also be the case for Ras (reviewed in Hennig et al.24 and Laplante and Sabatini27). It has previously been shown that certain growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor or epidermal growth factor induce proteolytic degradation of NF1, one of the RasGAPs.28 However, we did not observe any change in levels of NF1 or P120RasGAP after cytokine stimulation. Given that T-ALL cells express many RasGAPs (Figure 5), dissecting the mechanisms involved in both basal regulation of RasGTP/GDP and cytokine receptor action in transformed lymphocytes will require new genetic tools such as combination T-cell-specific knockout mice for RasGAPs or CRISPR/cas9-mediated cell line models.

Our results strongly point to a role of RasGAPs as crucial safeguards, especially in leukemic cells with dysregulated expression of RasGRP1. The mutational status of all RasGAPs has not been explored in the context of T-ALL, but our results show that at least 10 RasGAP family members are expressed in each of the pediatric T-ALL samples analyzed (Figure 5). It appears that broad coverage with different RasGAP proteins is required to counter-balance Ras nucleotide loading. This idea is supported by studies showing that T-lineage knockouts of NF1 or p120RasGAP had only minor phenotype and did not result in T-ALL,29,30 but that their combined deletion leads to the development of T-ALL.31 The importance of RasGAPs is also highlighted by emerging data showing that NF1 is mutated in both pediatric and adult T-ALL patients.32–34 Interestingly, there seems to be an increased instability of the Ras network evidenced by increased co-occurrence of NF1 mutations with other RasGAPs or RasGEFs in a wide range of human cancers.35 It would be interesting to investigate whether high basal RasGRP1 activity would lead to increased instability of the Ras network in T-ALL.

In summary, our findings document that overexpression of RasGRP1 in a subset of T-ALLs effectively renders Ras and Ras effector pathways in these leukemias responsive to pro-oncogenic cytokines. We propose that overexpression of RasGRP1 and the resulting high nucleotide exchange on Ras essentially create a new signaling avenue for proleukemic cytokines that can provide pro-oncogenic Ras signals in T-ALL. It is intriguing to speculate that similar scenarios may apply to other Ras-dependent tumors. For example, EGFR overexpression, as present in numerous solid cancers, might work in an analogous manner to high RasGRP1 levels in leukemia to drive basal nucleotide exchange on Ras36,37 and to render Ras pathways in those cancers overresponsive to alternate mitogenic factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

Murine T-ALL cell lines (1156S-O, 1156S-O-shRNA RasGRP1, 1156S-O-GFP, 1713S-N, T-ALL C6, T-ALL 9, T-ALL 15, T-ALL 55 and 98) were originally generated and maintained as described in Hartzell et al.5 Human T-ALL cell lines were cultured in RPMI 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin and streptomycin.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: phospho-Akt (S473) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA; No. 4060), phospho-Erk1/2 (T202/Y204) (Cell Signaling; no. 4377), phospho-STAT5 (Y694) (Cell Signaling; no. 9351), phospho-PLCγ1 (Y783) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA; 44-696G), α-tubulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA; T6074), total Ras (clone RAS10) (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; 05-516), neurofibromin (NF1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX, USA; sc-67), p120RasGAP (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA, USA; 610040), anti-CD4 (GK1.5) (Alexa Fluor 488; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), CD8 (53-6.7) PerCP Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences), TCRβ (H57-597) (APC Biolegends, San Diego, CA, USA), and donkey anti-rabbit PE (711-116-152) and donkey anti-rabbit APC (711-136-152) from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Murine RasGRP1 (m199) antibody was a gift from Dr Jim Stone. To detect phospho-RasGRP1 (T184), we generated an antibody against epitope SRKL-pT-QRIKSNTC. This mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 4G7) was generated and purified by AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA).

In vitro stimulations, Ras pulldown and western blotting

Cells were washed and rested in phosphate-buffered saline at 37 °C for 30 min before stimulation. Where indicated, cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or inhibitors (PLCγ inhibitor U73122; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA; 662035; DGK inhibitor; Sigma; D5794) during resting. After resting, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD4 (each 10 μg/ml) followed by goat anti-hamster (10 μg/ml) and goat anti-rat antibodies (1/1000), cytokines: IL-2, IL-7, IL-9 (each at 10 ng/ml, unless otherwise noted; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) or phorbol myristate acetate (25 ng/ml). All other techniques were described previously.5

Flow cytometry and fluorescent barcoding

Stainings were carried out in FACS buffer containing phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium salts (phosphate-buffered saline CMF) supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum, 2mM EDTA and 0.09% NaN3. Where surface staining was combined with intracellular staining, the following protocol was followed: cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were washed three times with FACS buffer and permeabilized with 90% ice-cold methanol for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing, cells were incubated with antibodies specific for phosphoproteins for 1 h at RT followed by washing and incubation for 30 min at RT with secondary antibodies and antibodies against surface markers. If samples were barcoded, fluorescent dyes (Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester; Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA); A-20000; or Pacific Blue succinimidyl ester; Molecular Probes; P-10163) were added to methanol and permeabilization took place at RT as described.38 Samples were acquired on BD LSR II (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and analyzed with FlowJo (Ashland, OR, USA) or Cytobank (Mountain View, CA, USA).

Calcium flux measurements

Cells were washed with IMDM (Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium) without serum and loaded with 2 μg/ml of the Ca2+ indicator Indo-1 (Molecular Probes; I1223) for 40 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were washed and resuspended in IMDM medium. For calcium flux measurements via flow cytometery, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (2C11, 10 μg/ml) and a baseline was registered for 20 s, then a crosslinking antibody (goat anti-hamster immunoglobulin G; final concentration 2 μg/ml) or cytokines were added and calcium levels were measured and analyzed on as LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Gene expression analysis in pediatric T-ALL patients

Patient sample collection and RasGAP expression analysis was performed as described previously.5 In all cases, except RASAL3, multiple probe sets were identified for the gene of interest. Data were normalized using RMA (robust multiarray average).

Digitonin nucleotide exchange assay

Cells were starved in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, then permeabilized with digitonin (10 μg/ml final concentration; Serve Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and loaded with 45 μCi (1.7 Mbq)/ml α-32P-GTP (which equals to 15 nM α-32P-GTP; Hartmann Analytic GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). Cells were lysed at the indicated time points by adding the lysis buffer (50mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (0.1 mg/ml Pefablock, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μM PMSF, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 100 μM sodium vanadate, 4mM β-glycerophosphate, 3.4 nm microcystin), GDP and GTP (both at 100 μM) and Ras antibody Y13-259 (2.5 μg/ml). Lysates were cleared and Ras–antibody complexes were collected on gammaBind-Sepharose. After washing, the beads were drained dry and subjected to Cherenkov counting in a scintillation counter for 1 min.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Roose lab members for helpful comments and Anna Hupalowska for the graphics in Figure 4. Our research was supported by an NIH-NCI Physical Science Oncology Center Grant U54CA143874, an NIH-NIAID Grant (P01 Program Project—AI091580), a Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation Grant and NIH-NCI Grant (R01—CA187318) (all to JPR), as well as by an NIH T32 training grant (5T32CA128583-05) and the KWF (Dutch Cancer Society) (MT and JB). This work was also supported by grants from the NCI to the Children’s Oncology Group including U10 CA98543 and CA180886 (COG Chair’s Grant), U10 CA98413 and CA180899 (COG Statistical Center) and U24 CA114766 (COG Specimen Banking).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- 1.Aifantis I, Raetz E, Buonamici S. Molecular pathogenesis of T-cell leukaemia and lymphoma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:380–390. doi: 10.1038/nri2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barata J, Keenan T, Silva A, Nadler L, Boussiotis V, Cardoso A. Common gamma chain-signaling cytokines promote proliferation of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2004;89:1459–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva A, Laranjeira ABA, Martins LR, Cardoso BA, Demengeot J, Yunes JA, et al. IL-7 contributes to the progression of human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4780–4789. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zenatti PP, Ribeiro D, Li W, Zuurbier L, Silva MC, Paganin M, et al. Oncogenic IL7R gain-of-function mutations in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:932–939. doi: 10.1038/ng.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartzell C, Ksionda O, Lemmens E, Coakley K, Yang M, Dail M, et al. Dysregulated RasGRP1 responds to cytokine receptor input in T cell leukemogenesis. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ksionda O, Limnander A, Roose JP. RasGRP Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factors in cancer. Front Biol (Beijing) 2013;8:508–532. doi: 10.1007/s11515-013-1276-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dower NA, Stang SL, Bottorff DA, Ebinu JO, Dickie P, Ostergaard HL, et al. RasGRP is essential for mouse thymocyte differentiation and TCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:317–321. doi: 10.1038/79766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim R, Trubetskoy A, Suzuki T, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lenz J. Genome-based identification of cancer genes by proviral tagging in mouse retrovirus-induced T-cell lymphomas. J Virol. 2003;77:2056–2062. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.2056-2062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinger MB, Guilbault B, Goulding RE, Kay RJ. Deregulated expression of RasGRP1 initiates thymic lymphomagenesis independently of T-cell receptors. Oncogene. 2004;24:2695–2704. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oki T, Kitaura J, Watanabe-Okochi N, Nishimura K, Maehara A, Uchida T, et al. Aberrant expression of RasGRP1 cooperates with gain-of-function NOTCH1 mutations in T-cell leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2011;26:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feske S, Skolnik EY, Prakriya M. Ion channels and transporters in lymphocyte function and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:532–547. doi: 10.1038/nri3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwig JS, Vercoulen Y, Das R, Barros T, Limnander A, Che Y, et al. Structural analysis of autoinhibition in the Ras-specific exchange factor RasGRP1. Elife. 2013;2:e00813. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitin N, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Signaling interplay in Ras superfamily function. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R563–R574. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daley SR, Coakley KM, Hu DY, Randall KL, Jenne CN, Limnander A, et al. Rasgrp1 mutation increases naive T-cell CD44 expression and drives mTOR-dependent accumulation of Helios(+) T cells and autoantibodies. Elife. 2013;2:e01020. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y, Sakane F, Kanoh H, Walsh JP. Selectivity of the diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor 3-[2-(4-[bis-(4-fluorophenyl)methylene]-1-piperidinyl)ethyl]-2, 3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)quinazolinone (R59949) among diacylglycerol kinase subtypes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:763–772. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio I, Grund S, Song SP, Biskup C, Bandemer S, Fricke M, et al. TCR-induced activation of Ras proceeds at the plasma membrane and requires palmitoylation of N-Ras. J Immunol. 2010;185:3536–3543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roose J, Mollenauer M, Gupta V, Stone J, Weiss A. A diacylglycerol-protein kinase C-RasGRP1 pathway directs Ras activation upon antigen receptor stimulation of T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4426–4441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4426-4441.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King PD, Lubeck BA, Lapinski PE. Nonredundant functions for Ras GTPase-activating proteins in tissue homeostasis. Sci Signal. 2013;6:re1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vries-Smits AM, van der V, Downward J, Bos JL. Measurements of GTP/GDP exchange in permeabilized fibroblasts. Methods Enzymol. 1995;255:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)55019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebinu JO, Bottorff DA, Chan EY, Stang SL, Dunn RJ, Stone JC. RasGRP, a Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein with calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding motifs. Science. 1998;280:1082–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubio I, Rennert K, Wittig U, Beer K, Durst M, Stang SL, et al. Ras activation in response to phorbol ester proceeds independently of the EGFR via an unconventional nucleotide-exchange factor system in COS-7 cells. Biochem J. 2006;398:243–256. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downward J, Graves JD, Warne PH, Rayter S, Cantrell DA. Stimulation of p21ras upon T-cell activation. Nature. 1990;346:719–723. doi: 10.1038/346719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubio I, Wetzker R. A permissive function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in Ras activation mediated by inhibition of GTPase-activating proteins. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennig A, Markwart R, Esparza-Franco MA, Ladds G, Ignacio R. Ras activation revisited: role of GEF and GAPs systems. Biol Chem. 2015;396:831–848. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorentla BK, Wan CK, Zhong XP. Negative regulation of mTOR activation by diacylglycerol kinases. Blood. 2011;117:4022–4031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barata JT, Silva A, Brandao JG, Nadler LM, Cardoso AA, Boussiotis VA. Activation of PI3K is indispensable for interleukin 7-mediated viability, proliferation, glucose use, and growth of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200:659–669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 and its impact on gene expression at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1713–1719. doi: 10.1242/jcs.125773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cichowski K. Dynamic regulation of the Ras pathway via proteolysis of the NF1 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2003;17:449–454. doi: 10.1101/gad.1054703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapinski PE, Qiao Y, Chang C-H, King PD. A role for p120 RasGAP in thymocyte positive selection and survival of naive T cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2011;187:151–163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliver JA, Lapinski PE, Lubeck BA, Turner JS, Parada LF, Zhu Y, et al. The Ras GTPase-activating protein neurofibromin 1 promotes the positive selection of thymocytes. Mol Immunol. 2013;55:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubeck BA, Lapinski PE, Oliver JA, Ksionda O, Parada LF, Zhu Y, et al. Cutting edge: codeletion of the Ras GTPase-activating proteins (RasGAPs) neurofibromin 1 and p120 RasGAP in T cells results in the development of T Cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Immunol. 2015;195:31–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balgobind BV, Van Vlierberghe P, van den Ouweland AMW, Beverloo HB, Terlouw-Kromosoeto JNR, van Wering ER, et al. Leukemia-associated NF1 inactivation in patients with pediatric T-ALL and AML lacking evidence for neurofibromatosis. Blood. 2008;111:4322–4328. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, Wu G, Heatley SL, Payne-Turner D, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann M, Heesch S, Schlee C, Schwartz S, Gokbuget N, Hoelzer D, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in adult ETP-ALL reveals a high rate of DNMT3A mutations. Blood. 2013;121:4749–4752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stites EC, Trampont PC, Haney LB, Walk SF, Ravichandran KS. Cooperation between noncanonical Ras network mutations. Cell Rep. 2015;10:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubio I, Rennert K, Wittig U, Wetzker R. Ras activation in response to lysophosphatidic acid requires a permissive input from the epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochem J. 2003;376:571–576. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Downward J. Role of receptor tyrosine kinases in G-protein-coupled receptor regulation of Ras: transactivation or parallel pathways? Biochem J. 2003;376:e9–e10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Fluorescent cell barcoding in flow cytometry allows high-throughput drug screening and signaling profiling. Nat Methods. 2006;3:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nmeth872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]