Abstract

Objective

We examine associations between the perception of ongoing psychological demands by ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and 6-year changes in carotid artery atherosclerosis by ultrasonography.

Methods

270 initially healthy participants collected ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) and recorded their daily experiences, using electronic diaries, over two 3-day periods. Mean intima-medial thickness (IMT) and plaque were assessed in the carotid arteries using B-mode ultrasound at baseline and again during a 6-year follow-up (average follow-up duration 73 months).

Results

Among those who had no exposure to antihypertensive medications over the course of follow-up (n = 192), daily psychological demands were associated with greater progression of IMT as well as plaque, after adjustment for demographic and risk factor covariates. Associations between demands and plaque change were partially accounted for by ABP differences among those reporting high demands. Among those who were employed at baseline (n=117), six-year IMT changes were more strongly associated with ratings of daily demands than with traditional measures of occupational stress.

Conclusion

These data support the role of psychological demands as a correlate of subclinical atherosclerotic progression, they point to ABP as a potential mechanism facilitating these effects, and they highlight the utility of EMA measures for capturing daily psychological demands with potential effects on health.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, intima medial thickness, ambulatory blood pressure, ecological momentary assessment, job stress, psychological stress

Numerous studies have shown that the social environment may be a marker of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. In human samples, the largest and most consistent literature in this area is the research on occupational stress, with the “job strain” model as the dominant paradigm (1, 2). According to this model, a workplace characterized by high psychological demands (paced performance, high output, and multiple responsibilities) and low decision latitude or control (task variety, and control over how the work is done) may enhance one's risk for CVD (3). Many studies report main effects of demands or control rather than the predicted demand-by-control interaction. Nevertheless, most of the evidence, including at least 11 independent prospective or cohort reports, has partially or fully confirmed an association between job strain variables and CVD risk (2, 4).

Recent reports suggest that occupational stress may exacerbate risk for subclinical atherosclerosis as well as for clinical CVD. For example, ultrasound measures of carotid artery intima medial thickness (IMT) are considered to be markers of atherosclerosis, and are associated with relevant pathological and histologic indicators of vascular disease (5, 6) as well as with risk for future heart attack and stroke (7). Measures of occupational stress (including measures of job strain) have been shown to be associated with carotid IMT among working men and or women in 4 cross-sectional studies (8-11) as well as in a four-year prospective follow-up (12) (see also (13)).

Although the job strain model emphasizes the importance of the workplace as a source of psychological demands and decision latitude, an alternative perspective suggests that demand and control may represent general characteristics of the social environment or daily experience, not restricted to work, that may be related to disease risk. We have used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) (14) to assess behavioral and biological characteristics of daily life that are relevant to job strain. EMA measures may capture participants' momentary experiences of strain in real world settings more accurately than traditional global retrospective reports (15), and they allow us to examine such experiences both on the job and off, in a manner that should assist us in understanding how psychosocial risk factors may be translated into alterations in risk.

The Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project (PHHP) is a prospective epidemiological study designed to examine the role of psychosocial characteristics in the development of subclinical CVD in an initially healthy sample (age 50-70). One of the unique features of this study involves its use of EMA assessments across six days to characterize the daily experiences of study participants at baseline. We have shown that higher average momentary ratings of activity demand and lower mean ratings of decision latitude or control were associated concurrently with carotid artery IMT in this sample (16). These effects were shown among working as well as nonworking individuals, consistent with our view that these characteristics may be important dimensions of daily experience not limited to the workplace, Unlike the EMA ratings, traditional questionnaire measures of job strain were not associated with IMT in this sample. Some of our cross-sectional data were also consistent with the possibility that effects of daily demands and control on ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) may partially account for these effects (16).

In a follow-up report, we showed that averaged EMA measures of daily demands were associated with three-year progression of IMT as well (17). These prospective results help to reduce the possibility that observed associations between daily experience and subclinical disease may be entirely accounted for by the effects of subclinical disease on behavior. At the three year follow-up, the association between daily demands and carotid IMT were moderated by gender; with associations observed in men but not in women. We have since collected an additional carotid ultrasound assessment at the six-year follow-up, which should provide us with valuable information about the implications of daily experiences of demand and control for longer term health.

Although carotid IMT measures have been shown to be valid markers of CVD, much of the variance in vascular thickening in these regions involves vascular remodeling in response to long term blood pressure (BP) load rather than atherosclerosis per se (18, 19). Carotid ultrasonography permits us not only to measure IMT but also to obtain direct images of arterial plaque, which appear as irregular protrubances into the vessel lumen. Assessing associations with the development of new plaques as well as progression of IMT should serve to cross- validate our carotid ultrasound outcomes as markers of atherosclerosis as well as CVD risk.

In an effort to better understanding the specific role of the workplace in the link between chronic stress and cardiovascular risk, we examined whether employment status at baseline might moderate any influence of activity demands on disease progression. Given the potential role played by ABP in the association between occupational stress and cardiovascular disease, we also examined whether antihypertensive drug use might moderate any influence of daily activity demands on disease progression. The sample was initially medication free (16), but a substantial portion of the sample had been prescribed antihypertensive medications over the course of the 6-year follow-up, providing us with the opportunity to test these effects. As a follow-up to our earlier cross-sectional results, we examined the role of ABP as a mediator of any 6-year disease progression effects observed here.

This report, then, is designed to examine the association between individual differences in experiences of Demand and Control during daily life and six-year progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, as assessed by IMT and plaque in the carotid arteries. The stability of previous results reported in this sample (sex differences in the magnitude of these effects; the effects of ambulatory blood pressure; and the relative prognostic value of occupational stress measures and daily experience reports) will be examined at this six-year follow-up interval as well. These data have bearing on our understanding of the long term role of occupational stress in cardiovascular risk and the potential merits of EMA methods for helping us to characterize some of the potential pathways by which psychosocial factors may alter cardiovascular health.

Method

Participants

270 subjects from the Pittsburgh healthy Heart Project (PHHP) were included in this report. The PHHP is a prospective epidemiological study examining biobehavioral predictors of subclinical CVD progression in an asymptomatic, adult (ages 50-70 at baseline), community-dwelling sample. Participants were initially excluded if they reported a history of chronic medical disorders (including symptomatic CVD), pharmacological treatment for hypertension or hypercholesterolemia in the past year, or clinic BP greater than 180 mmHg systolic blood pressure (SBP) or 110 mmHg diastolic blood pressure (DBP). 340 subjects had complete data at baseline (16, 17). For more information about sampling criteria and recruitment procedures, see (16)..

Participants were re-consented for the six-year follow-up, and were paid $350 for completing 6 additional visits, including one visit for medical history evaluation, one visit for repeat carotid ultrasound assessment, 3 visits related to repeat ambulatory monitoring assessments (see below), and one visit for other procedures not relevant to the current report. 270 subjects had complete carotid scan data at the 6-year follow-up. This study was conducted in compliance with the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Measures and Procedures

Baseline demographic information

A demographic questionnaire was completed at baseline. Race was coded as a binary variable (White, non-White), and educational attainment was scored as a continuous variable with four levels (16). Occupational status was assessed at the initial visit and again, 1 month later. When comparing results for employed and nonemployed individuals, we used only those who were consistently employed or unemployed across these two occasions, and we excluded those who failed to endorse spending any time at “work” during the EMA monitoring period (16).

Baseline cardiovascular risk factors

An initial medical screening visit included a medical history interview, BP screening, and blood draw for risk factor assessment. American Heart Association guidelines (20) were followed for clinic BP assessment. A standard lipid panel (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)) was assessed. Fasting serum glucose was assayed via standard colorimetry, and insulin concentration was measured by radioimmunoassay. Current (baseline) smoking status was determined by interview report. Body mass index and waist circumference (in cms) were also assessed.

Job strain at baseline and follow-up

The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ; (21)) was administered at baseline and at six-year follow-up to those who indicated that they were currently employed (16). Psychological Job Demands is a five-item scale that measures workload and intensity (e.g. “My job requires working very fast”), and Decision Latitude is a weighted sum of two subscales, Skill Discretion (six items; e.g., “My job requires a high level of skill”) and Decision Authority (three items; e.g., “My job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own”).

Ambulatory assessments: Baseline and follow-up

Approximately 1 month following the initial baseline visit, participants were trained to use an automated ABP monitor (Accutracker DX, SunTech Medical, Raleigh, NC) and a self-report electronic diary (Palm Pilot Professional, Palm, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Assessments were collected every 45 minutes during the waking hours for 3 days; approximately 4 months later, participants were retrained and sent out for an additional three days of monitoring using similar procedures (16, 17). Those with fewer than 30 ABP readings on one or both of the monitoring intervals were excluded. Individuals who were retained in the sample yielded an average of 106 (range= 66-148) observations apiece with paired electronic diary and ABP data over the course of the two baseline monitoring periods. Software used for the electronic diary (invivodata, inc., Scotts Valley, CA) created a time and date stamp for each record, providing a check on compliance (22).

Following each ABP assessment, the electronic diary administered a 45-item self-report questionnaire adapted from the Diary of Ambulatory Behavioral States (23) from which the measures of momentary Demand and Control were extracted. The three-item Task Demand scale (i.e., “Required working hard?” “required working fast?” and “Juggling several tasks at once?”) and the two-item Decisional Control scale (i.e., “Could change activity if you chose to?” and “Choice in scheduling this activity?”) were based upon comparable scales from the JCQ (21), but were revised to reflect activities “during the past 10 minutes” both in and out of the workplace. Participants responded to each of these items using a visual analogue scale with a bipolar response anchor (NO, YES). Scores ranging from 0 to 10 were derived for each item and were averaged across items for each scale. When averaged over a three-day period, scores on each of these EMA scales have been shown to be moderately stable (four month test-retest correlations of .73 and .72 for Demand and Control, respectively; (16). When ratings of the workplace were extracted, aggregated scores on these momentary measures are significantly correlated with the Psychological Demands and Decisional Control subscales from the JCQ, as expected (16).

At the six-year follow-up, participants underwent an additional three days of ambulatory monitoring, using the same ambulatory blood pressure unit (Accutracker DX) and a similar self-report electronic diary (Palm Z22). Once again, assessments on both devices occurred every 45 minutes during the waking day, and a 45-item self-report questionnaire was completed on the electronic diary at each assessment. Momentary Demand and Decisional Control were among the scales assessed, using items identical to those employed at baseline. ABP was collected overnight on two of the three monitoring days (data not reported here). Some participants opted out of the ambulatory monitoring portion of the study, and there was missing data on others. Ambulatory self-report data were available for 241 of the original sample, and daytime ambulatory blood pressure data were available on a subsample of 235.

Carotid ultrasound assessments: Baseline and follow-up

Approximately 2 months after the initial medical screening visit, participants attended an appointment with the ultrasound research laboratory affiliated with the project. Using a B-mode ultrasound scanner (Toshiba SSA-270A and SSA-140A, Toshiba American Medical systems, Tustin, CA), we identified the borders of the intima and medial layers of the left and right carotid arteries, using the intima-lumen interface and the media-adventitial interface as markers. Distances between these interfaces were measured on digitized images across the distal 1 cm (far wall) of the right and left common carotid artery, carotid bulb, and proximal 1 cm of the internal carotid. Studies were read using the Automated Measurement System (Goreborg University, Gothenburg, Sweden) using an automated edge detection algorithm (24). Plaque was defined as a focal projection within the intima-media layer that was at least 50 % greater than the adjacent IMT. Number of plaques were counted across each of the six arterial segments (three segments from both the right and left side). IMT measures at each of six locations were averaged to create a mean IMT score (see (25, 26). Identical procedures were used at the six-year follow-up.

Six-year changes in IMT and plaque were measured using difference scores (6-year value minus baseline value). Two extreme outliers (+/- > 4 standard deviations from the mean) were eliminated for IMT change (valid data for n=268), and the score for the remaining subjects was further subject to a logarithmic transformation to reduce skewness. The plaque change measure was missing for 2 subjects (data present for n=268). (One missing value for clinic SBP resulted in a sample size of 267 for the analyses that included covariates).

Average follow-up duration between the baseline and 6-year carotid scan was 73 months (range=53-91 months). Both measures were adjusted for the duration between readings (IMT change/(follow-up duration to the nearest month/12; for plaque change, we used log of follow-up duration as an offset variable).

Medical diagnoses and medication use: Baseline and follow-up

A medical history interview at baseline assessed current medical diagnoses and medication use. These were assessed again by telephone at 6, 18, and 30 months after study intake, and at in-person interviews (with pill bottles in hand) at the 3-year and 6-year follow-up appointments. A cumulative measure was derived documenting exposure (yes/no) to antihypertensive medication (diurteics, beta blockers, ace inhibitors, angiotension antagonists, calcium channel blockers, and alpha blockers) over the course of the 6 year follow-up period.

Data Analysis

We used general linear models (GLM, SAS) for assessing correlates of IMT change, and negative binomial regression (GENMOD, SAS) for assessing changes in plaque count. Use of the latter procedure was necessitated by the skewness of the plaque count score (almost 40 % of the sample showed no change in number of observable plaques, although the distribution was not determined to be zero-inflated). Plaque change scores were missing for two subjects (data present for n=268).

As model covariates, we included the demographic and biologic variables available in this data set that have been shown in the previous literature to be associated with carotid atherosclerotic progression, including baseline disease (IMT or plaque count), age, sex, clinic systolic blood pressure (SBP), fasting glucose, insulin, current smoking status, HDL, LDL, and waist circumference (27-30). For analyses testing mediation, we used the longitudinal methods for the two-wave design described by Cole and Maxwell (31); path “a” is estimated by regressing M2 (6-year ABP) onto X1 (e.g., baseline Demand) adjusting for M1 (baseline ABP), and Path “b” is estimated by regressing Y2 (e.g., 6-year plaque) onto M1 adjusting for X1 and Y1 (e.g., baseline plaque). Baseline M1 and Y1 were adjusted to reduce the bias from auto-regressive effects (32). The cross-product of these two coefficients was tested to estimate the indirect effect of X on Y through M using MacKinnon's Assymetrical Confidence Interval method (PRODCLIN (33, 34)).

Results

Sample Characteristics

270 study enrollees had carotid scan data available for baseline as well as the 6-year follow-up period. When compared to baseline (N= 340), this represents a 79 % retention rate. 54 % (145/270) of the sample was female and 14 % (37/270) was nonwhite. When compared with those who re-enrolled at 6 years, study dropouts were significantly more likely to be male (60 % vs. 47 %, t (338) = 2.05, p = .04). There were no significant differences between dropouts and those continuing in the study with respect to age, race, education, baseline disease, or employment status.

At follow-up, 6 % of the sample (17/270) reported having experienced a cardiac event at some point during the follow-up period, and 29 % of the sample (78/270) reported current or past use of antihypertensive medication during follow-up. As expected, baseline BP was significantly higher among those who subsequently reported antihypertensive use (after adjustment for age, race, sex, and education, for clinic SBP, b = 15.53, F (1, 263) = 71.64, p < .0001; for ambulatory SBP, b = 10.67, F (1, 264) = 52.9, p < .0001), and there was also a larger blood pressure range between persons among the medicated group (e.g. s.d. of 14.3 for ambulatory SBP) than among those who were not referred for medication (s.d.= 9.5).

Stability of Employment Status and Ambulatory Assessments

Of the 264 subjects on whom employment data was available at follow-up, only 36 % (n = 96) reported working full or part time at the 6-year follow-up. The rest of the sample was retired (n = 142, 54 %), unemployed (n = 5, 1.9 %), disabled (n = 2, .8 %), homemaking (n = 16, 6.1 %) or other (n = 3, 1.1 %). Approximately one-third (34 % or 39/114) of the follow-up group who had been employed at baseline were no longer working at the six year follow-up point; in contrast, only a small proportion (3.6 % or 8/108) of those who were unemployed at baseline described themselves as employed 6 years later.

Changes in daily experiences of Task Demand and Control were shown across the 6-year period in this aging sample, with significant decreases in mean momentary Demand (t (1, 240) = -15.26, p < .0001, - 1.1 points on a 10-point scale) and increases in mean momentary Control (t (1, 240) = 3.47, p .0006, + .3 points on 10-point scale). When we examined only individuals at 6 years who were initially employed at baseline (n = 99), the effect of time on Control was significantly moderated by employment status at the 6-year point (F (1, 97) = 10.36, p = .002), with significant increases in Control shown only among those who had stopped work during the follow-up (t (1, 34) = 4.28, p = .0001, + 1.1 points) and no changes among the continuing workers (t (1, 63) = 1.41, n.s., + .2 points).

Significant increases in ambulatory systolic blood pressure were shown over 6 years, but only among those with no exposure to antihypertensive drugs during the follow-up period (Time × Drug F (1, 233) = 22.31, p < .0001; + 11 mm Hg for those with no drug exposure (t (1, 160) = 11.52, p < .0001), + 2.3 mmHg for medicated group (n = 74; t (1, 73) = 1.35, p = .18). In contrast, for ambulatory diastolic pressure, significant decreases were shown over the 6-year period, but only among those with antihypertensive drug exposure (Time × Drug F (1, 233) = 30.64, p < .0001; + .14 mmHg (t (1, 160) = .33, p = .75 for unmedicated group, -4.6 mmHg, t (1, 73) = -5.7, p < .0001 for medicated group). Six-year retest stability of ABP measures was comparable for the medicated and unmedicated groups (r = .50, r = .66, for SBP and DBP, respectively for unmedicated sample, n = 161, p 's < .0001; r = .56, r = .60 for medicated sample, n = 74, p < .0001). Among those with data available from both sources (n = 225), the stability of mean momentary Demand and Control across the 6-year period (r = .56, p < .0001, n = 225, r = .49, p < .0001, n = 225, respectively) was comparable to that for ABP; r = .55, p < .0001 for SBP, r = .61, p < .0001 for DBP.

IMT and Plaque Change

Median annualized change in IMT was .017 (n=268, at follow-up, median IMT was .84 mm, mean= .89, sd= .22). Median change in number of observable plaque lesions was 1.0 (at follow-up, median number of lesions was 2.0, mean= 2.46, sd =2.74). 59 % of the sample showed new observable plaques over the follow-up period. There were significant main effects of age (b = .02, χ2 (1, N=268) = 15.29, p < .0001) and sex (after age adjustment) ( b = -.1051, χ2 (1, N=268) = 4.17, p =.04) on plaque progression, with older individuals and men showing greater progression over time. For IMT, there were no main effects of age or sex, but there was a significant age-by-sex interaction (F (1, 264) = 5.20, p = .02), with men showing greater rate of progression with age (b = .0001, F (1, 264) = 5.96, p = .02 by analysis of simple slope), and no such effects for women (b = -.00003, n.s.). There were no significant age-adjusted effects of race or education on plaque or IMT progression.

We examined the effects of traditional risk factors on IMT and plaque progression, after controlling for age. There was a significant effect of waist circumference on annualized IMT progression (b =00003, F (1, 265) = 8.45, p = .004) and plaque change (b = .006, χ2 (N = 268) = 7.26, p = .007). Baseline LDL, baseline disease, and use of antihypertensive medications during the follow-up period were related to progression of plaque, but not IMT (b = .002, χ2 (N = 268) = 4.25, p = .04 for LDL; b = .09, χ2 (N = 268)= 4.92, p = .03 for baseline plaque; b = .15, χ2 (N = 268) = 7.21, p = .007 for antihypertensive use). Mean ambulatory systolic blood pressure was significantly associated with plaque progression (b =.007, χ2= 10.99, p =.0009). Clinic blood pressure, current smoking status, glucose and insulin, and HDL cholesterol were unrelated to the progression of disease in this sample.

Demand and Control as Predictors of Atherosclerotic Progression

We tested our main hypotheses using models with pre-designated covariates, as outlined in the Data Analysis section described above. For plaque progression (after covariate adjustment), there was no significant main effect of Task Demand, but there was a significant drug-by-Demand interaction (χ2 (N = 267) = 4.04, p = .045): Task Demand was significantly associated with plaque progression among those with no exposure to antihypertensive drugs over the course of follow-up (b = .048, χ2 (N = 267) = 4.91, p = .03 (n = 189), r2 =.026, but not among those with current or past treatment involving hypertensive drugs (n = 78, p = .45). For IMT progression, Task Demand was marginally associated with IMT (b = .0002, F (1, 255) = 3.09, p = .08). As in the case of plaque, Task Demand was a significant predictor of IMT progression among those with no exposure to antihypertensive drugs (b = .00002, F (1, 178) = 4.81, p = .03), r2 =.025 but not among those with antihypertensive drug exposure (p = .65; Drug-by-Demand interaction not significant, p = .18).

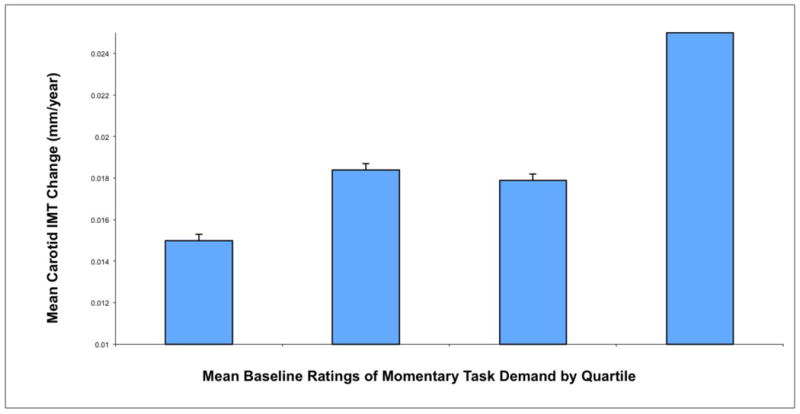

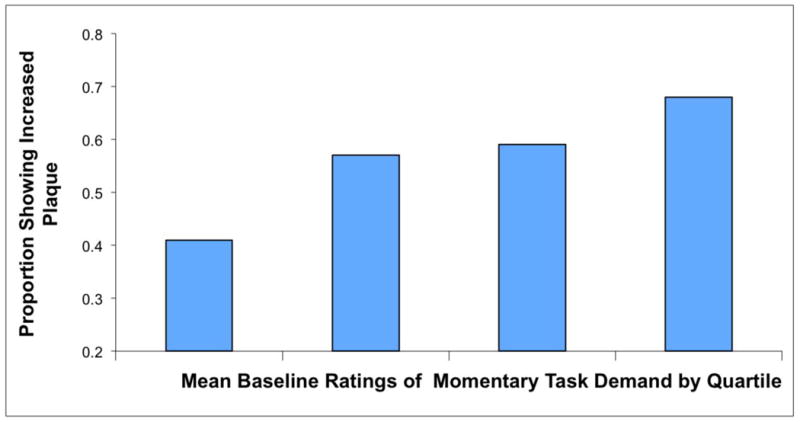

Task Control was associated neither with IMT nor with plaque progression in the sample as a whole (p = .64 for IMT; p = .43 for plaque), and this did not vary as a function of medication history. There were no significant interactions between Task Demand and Task Control with respect to their associations with IMT or plaque progression. The effects of Demand and Control on disease progression did not vary as a function of age, sex, race, or education (none of these interactions was significant). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the association between mean baseline ratings of momentary Demand and IMT and plaque progression, in the antihypertensive-free subsamples, using models with covariate controls.

Figure 1.

Associations between mean momentary ratings of Task Demand during daily life at baseline and annualized 6-year changes in mean IMT. Subsample involves those free from antihypertensive medications only (n = 191). Covariates include baseline IMT, age, sex, current smoking status, clinic systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, LDL and HDL cholesterol, gasting insulin, and waist circumference. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Figure 2.

Associations between mean momentary ratings of Task Demand during daily life at baseline and proportion of the sample showing increases in the number of observable carotid artery plaques. Subsample involves those free from antihypertensive medications only (n= 190). Covariates include baseline IMT, age, sex, current smoking status, clinic systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, LDL and HDL cholesterol, gasting insulin, and waist circumference.

Mediation Analyses

In the sample as a whole, results were consistent with the possibility that effects of Task Demand on plaque change may be partially mediated by ambulatory SBP. Adjusting for baseline ambulatory SBP along with the other baseline covariates, baseline Task Demand was associated with 6-year mean ambulatory SBP (b = 1.37, F (1, 220) = 4.14, p < .05), and adjusting for baseline plaque along with baseline Demand scores, baseline ambulatory SBP was associated with 6-year plaque (b = .02, χ2 (N = 233)= 11.86, p = .0006. Confidence intervals for the indirect effects of Task Demand through ambulatory SBP (cross product of these two longitudinal coefficients) were consistent with significant mediation (.0016-.0646). In the non-medicated subgroup, in contrast, there were no significant mediation findings. In this subgroup, baseline ambulatory SBP was associated with 6-year plaque after covariate adjustment (b = .02, χ2 (N = 158)= 4.17, p = .04) but baseline Task Demand was not associated with 6-year ABP. Mediation effects were not significant for IMT.

Effects for Employed Individuals

We examined whether the relationship between Task Demand and disease progression varied as a function of initial employment status. The sample size for these comparisons was somewhat smaller (n = 225) because employment status at baseline was coded inconsistently (a number of individuals who indicated that they were employed did not ever endorse being at “work” on the electronic diary (16); because these individuals were excluded from the analyses in our initial paper, we also chose to exclude them here). After covariate adjustment, there was a significant interaction between Task Demand and initial employment status on IMT progression (F (1, 225) =3.96, p = .048), with significant effects shown only for those who were employed at baseline (n= 117, b = .00002, F (1, 105)= 6.2, p = .01, r2 = .05) and not among those who were unemployed at the beginning of the study (n = 108), p = .92. There was no relationship between employment status at baseline and antihypertensive medication use over the course of the study (r = -.02, p = .77).

Mean Demand ratings were significantly associated with IMT progression both for periods of the day when participants identified their location as being “at work” (b =.0002, F (1, 105) = 5.23, p = .02) as well as for nonwork observations (b = .0003, F (1, 105) =4.26, p=.04). Associations between baseline Demand and plaque progression were marginally significant (b = .05, χ2 (N = 117) = 3.43, p = .06) as were those involving Demand for work and nonwork observations (both p = .06). There were no significant Demand-by-drug effects, there were no significant gender interactions, and there were no significant effects of Task Control or Demand-by-Control interactions among individuals who were employed at baseline.

We compared our EMA measures to traditional measures of occupational stress derived from the JCQ. In contrast with our diary measure of Task Demand, scores on the Psychological Demands subscale of the JCQ were associated neither with IMT nor with plaque progression in this employed subsample (p = .43, p = .14). The magnitude of the relationship between mean Task Demand and IMT progression (partial r of .24) was significantly larger than the magnitude of the effect linking IMT progression with JCQ Psychological Demands (partial r of .08) (t (1, 116) = 2.03, p < .05; Williams-Hotelling t test (35).

The Decision Latitude subscale from the JCQ was associated neither with IMT nor with plaque progression. There was, however, a significant interaction between JCQ Psychological Demands and Decision Latitude with respect to their association with plaque progression χ2 (N = 117) = 5.37, p = .02. Follow-up analyses of simple effects (36) suggested that Psychological Demands were associated with increases in plaque progression among those rating their jobs as low on Decision Latitude (b = .0293, χ2 = 8.25. p = .0041) but not among those for whom Decision Latitude was rated high (p = .63). When mean Task Demand was substituted for the JCQ Psychological Demands scale in this model, the interaction effect (with JCQ Decision Latitude) was slightly larger χ2 (N = 117) = 6.97, p = .008, and the simple effect involving Task Demand among those with high Decision Latitude was at least equivalent (b = .1316, χ2 = 10.88. p = .001) with that involving the JCQ Psychological Demands scale.

Discussion

We examined the relationship between perceptions of daily activity demands and six-year progression of atherosclerosis by carotid artery ultrasonography in a group of initially healthy adults. Among those who remained free of antihypertensive medication, daily activity demands were associated with enhanced atherosclerotic progression. These effects were observed across two different indices of atherosclerosis, plaque and IMT, and could not be accounted for by either demographic variables or by standard risk factors. The effects of daily activity demands on IMT progression were also moderated by baseline employment status: Those who were employed at baseline showed significant associations between daily activity demands and progression of IMT, but those who were unemployed did not.

These findings are an extension of our previously reported results, in the same sample, showing cross-sectional associations between daily Task Demand ratings and carotid artery measures of atherosclerosis at baseline (16), as well as those from a subsequent report showing associations between Task Demand and 3-year disease progression among the men in this sample (17). Unlike the previous results, the current 6-year findings did not differ as a function of gender. Because the findings reported here are prospective, they cannot be accounted for by reverse causality, i.e., effects of atherosclerosis that might reduce physical capacity and, thereby, enhance perceptions of effort or burden associated with activities of daily living. The effect sizes observed here in the unmedicated group (accounting for 2.5% of the variance) are roughly equivalent to those observed in the sample at baseline (none of whom were on antihypertensive medication) at which point mean Task Demand score was associated with 2 % of the variance in IMT (16). Because the findings extend over a six-year period of time, they suggest that whatever mechanisms might be responsible for the association are relatively stable and appear to exert a long-term influence on disease progression.

Ratings of daily life demands were associated not only with carotid artery atherosclerosis progression, but also with measures of ABP at baseline. Two results reported here are consistent with the possibility that elevations in ABP may play a role in the link between Task Demands and disease progression: First, as noted above, exposure to antihypertensive drugs over the course of the follow-up appeared to moderate these effects. That is, the effects were only evident among those whose BP was untreated, suggesting that treatment of BP may reduce the effects of daily demands on BP during daily life. This moderation effect was statistically significant in the case of plaque progression, but was also evident in the pattern of findings on IMT progression. Second, baseline ambulatory SBP was a significant mediator of the association between baseline Task Demand and 6-year plaque progression. A number of studies link job strain variables with ABP (1); it is possible that a demanding psychosocial environment elicits recurrent activation of sympathoadrenal pathways during daily life in a manner that may contribute both to elevated ABP, as well as to some of the pathophysiological changes that contribute to early signs of atherosclerosis (37, 38). It is notable that there were significant 6-year prospective effects on plaque involving baseline ABP, whereas clinic BP measures taken at baseline were not associated with disease progression. Such findings are consistent with previous literature (39) and with the effects we observed at baseline in this sample (40), and they suggest that ambulatory measures, collected during daily life, may be more sensitive than those obtained in the clinic.

Although some of the data reported here were consistent with a mediation effect involving ABP, the results did not entirely follow the pattern that might be expected for mediation. First of all, there were no significant mediation effects among the subgroup of participants who showed the most consistent findings, i.e., those who were unexposed to antihypertensive medications. Second, there were no significant mediation effects involving ABP for IMT progression. As might be expected, ABP was significantly higher and more variable across people at baseline among those who were subsequently prescribed antihypertensive medication, so it is possible that range restriction reduced the power to detect a mediation effect in the unmedicated group. Sample size is also a limitation in a number of these analyses, particularly those involving moderation, mediation, and subgroup effects, potentially contributing to the inconsistent effects across different methods and outcome measures.

Perceptions of daily life demands were measured in this study using EMA methods aggregated over a 6-day period. Some of our data (comparing effects associated with Task Demand at work vs. Psychological Demands from the JCQ) are consistent with the possibility that findings involving aggregated EMA methods may be more robust than results obtained using conventional self-report, in a matter analogous to the ambulatory vs. clinic BP findings described above. It should be noted, however, that our EMA methods “outperformed” traditional assessments at the 6-year point only for IMT measures, and not for plaque. Indeed, some evidence from this sample suggested that our EMA measures of Task Control may be somewhat less sensitive than those derived from the JCQ (a Demand-by-Control interaction on IMT progression was detected by JCQ and not by EMA). The differential effectiveness of EMA may be construct dependent, with some psychosocial measures (e.g., Decision Latitude) being more difficult to capture than others (Demand) by momentary report (41).

Some of the findings in this study are consistent with the notion that the workplace is a particularly important source of daily stress with implications for health. For example, we found that the association between perceptions of daily demands and accelerated IMT progression were stronger among those who were employed at baseline than among those who were not. On the other hand, in the sample as a whole, the effects of demanding life conditions outside of the workplace appeared to be equivalent to those associated with the workplace as predictors of disease progression. These findings are consistent with our previous results in this sample and they suggest that health effects of demand and control are not restricted to the workplace. Moreover, we found no moderating effects of employment status on the relationship between daily demands and six-year plaque progression in this study, and we were unable to detect a moderating impact of changes in work status (retirement) on the trajectory of these effects, both of which would have been predicted by a model that emphasized workplace-specific influences of daily demand and control on health outcomes.

Future research is needed to test assumptions of the job strain model with respect to its impact on cardiovascular risk. For example, in samples of employed adults, we need to clarify the sources of social environmental influence on perceptions of demand and control during daily life, and the extent to which temperamental factors may also contribute to these effects. The mechanisms by which daily chronic stressors may exacerbate cardiovascular disease risk, and the interventions that may be most effective in forestalling such effects are also important topics for further investigation. Finally, more research is needed to help us understand whether and when the evaluation of daily experience may provide a more sensitive window into the effects of psychosocial stress when compared with traditional measures, in terms of its association with proximal biological mediators of health status (such as ABP and carotid atherosclerosis) as well as clinical events (41).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL56346).

We acknowledge the assistance of Jee Won Cheong and Atika Khurana who assisted with conceptualizing some of the data analyses. Saul Shiffman is co-founder and Chief Science Officer of invivodata, inc., which provides electronic diary methods like those reported here for use in clinical trials.

Glossary

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- IMT

intima medial thickness

- ABP

ambulatory blood pressure

- EMA

ecological momentary assessment

- BP

blood pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- JCQ

Job Content Questionnaire

- PHHP

Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project

Footnotes

Author Note: Some of these data were presented at the American Psychosomatic Society, March, 2011, San Antonio, TX.

References

- 1.Belkic K, Landsbergis P, Schnall P, Baker D, Theorell T, Siegrist J, Peter R, Karasek R. Psychosocial factors: Review of the empirical data among men. In: Schnall PL, Belkic K, Landsbergis P, Baker D, editors. Occupational Medicine: The workplace and Cardiovascular Disease State of the Art Reviews. Vol. 15. 2000. pp. 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kivimaki M, Viortanen M, Elovainio M, Louvonen A, Vaananen A, Vahtera J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health. 2006;32:431–42. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karasek RA, Theorell T. Healthy work: stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkic KL, Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Baker D. Is job strain a major source of cardiovascular disease risk? Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health. 2004;30:85–128. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste P, Raoletti R. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: A direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation. 1986;74:1399–406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.6.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong M, Edelstein J, Wollman J, Bond MG. Ultrasonic pathological comparison of the human arterial wall. Arteriosclerosis and thrombosis. 1993;13(4):482–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Leary DH, Polak JF. Intima-medial thickness: A tool for atherosclerosis imaging and event prediction. American Journal of Cardioology. 2002;90:18L–21L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muntaner C, Nieto FJ, Cooper L, Meyer J, Szklo M, Tyroler HA. Work organization and atherosclerosis: Findings from the ARIC study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 1998;14:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordstrom CK, Dwyer KM, Bairey Merz N, Shircore A, Dwyer JH. Work-Related Stress and Early Atherosclerosis. Epidemiology. 2001;12:180–5. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosvall M, Ostergren P-O, Hedblad B, Isacsson S-O, Janzon L, Berglund G. Work-related psychosocial factors and carotid atherosclerosis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:1169–78. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hintsanen M, Kivimaki M, Eloainio M, Pulkki-Raback L, Keskivaara P, Juonala M, Raitakari O, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Job strain and early atherosclerosis: The cardiovasculr risk in Young Finns study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:740–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000181271.04169.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch J, Krause N, Kaplan GA, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Workplace demands, economic reward, and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1997;96:302–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstrom T, Hintsanen M, Jokela M, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Kivimaki M, Juonala M, Raitakari OT, Viikari JS. Change in job strain and progression of athersclerosis: The CAriovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2011;16:139–50. doi: 10.1037/a0021752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone A, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza A, Nebeling L, editors. The Science of Real-Time Data Capture: Self-Reports in Health Research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamarck TW, Muldoon M, Shiffman S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Gwaltney CJ. Experiences of demand and control in daily life as correlates of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in a healthy older sample: the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project. Health Psychology. 2004;23:24–32. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamarck TW, Muldoon M, Shiffman S, K S-T. Experiences of demand and control during daily life are predictors of carotid artery atherosclerotic progression among healthy men. Health Psychology. 2007;26:324–32. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bots ML, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Increased common carotid intima-media thickness: Adaptive response or a reflection of athersclerosis? Findings from the Rotterdam study Stroke. 1997;28:2442–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka H, Dinenno FA, Monahan KD, DeSouza CA, Seals DR. Carotid artery wall hypertrophy with age is related to local systolic blood pressure in healthy men. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Bioloogy. 2001;21:82–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M. Human blood pressure determination by shygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88:2460–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karasek RA, Pieper C, Schwartz J, Fry L, D S. Job content instrument questionnaire and user's guide. New York: Columbia Job/Heart Project; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamarck TW, Shiffman S, Muldoon MF, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Gwaltney CJ, Janicki DL, Schwartz J. Ecological momentary assessment as a resource for social epidemiology. In: Stone A, Shiffman S, Atienza A, Nebeling R, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 268–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamarck TW, Shiffman SM, Smithline L, Goodie JL, Thompson HS, Ituarte PHG, Jong JY, Pro V, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Gnys M, et al. The Diary of Ambulatory Behavioral States: a new approach to the assessment of psychosocial influences on ambulatory cardiovascular activity. In: Krantz DS, Baum A, editors. Perspectives in behavioral medicine: technology and methods in behavioral medicine. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 163–94. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wendelhag I, Liang Q, Gustavsson T, Wikstrand J. new automated computerized analyzing system simplified readings and reduced the variability in ultrasound measurement of intima-media thickness. Stroke. 1997;28:2195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman R. Continuous quality assessment programs can improve carotid duplex scan quality. Journal of Vascular Technology. 2001;25:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman RP, Kao A, Fitzgerald SG, Shook B, Tracy RP, Kuller LH, Broackwell S, Manzi S. Progression of carotid intima-media thickness and plaque in women with sytemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58:835–42. doi: 10.1002/art.23196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson HM, Douglas PS, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Li S, Chen W, Berenson GS, Stein JH. Predictors of carotid intima-media thickness progression in young adults: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Stroke. 2007;38:900–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258003.31194.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koskinen J, Kahonen M, Viikari J, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Ronnemaa T, Lehtimaki T, Hutri-Kahonen N, Pietikainen M, Jokinen E, Helenius H, Mattisson N, Raitakari OT, MJuonala M. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in predicting carotid intima-media thickness progression in young adults: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2009;120:229–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.845065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackinnon AD, Jerrard-Dunne P, Sitzer M, Buehler A, von Kegler S, Markus HS. Rates and determinants of site-specific progression of carotid artery intima-media thickness: The Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study. Stroke. 2004;35:2150–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136720.21095.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Chambless L, Jacobs DR, Nieto J, Szklo M. Socioeconomic differences in progression of carotid intima-media thickness in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vascular Biology. 2006;26:411–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000198245.16342.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–77. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichardt CS, Gollob HF. Satisfying the constraints of causal modeling. In: Trochim WMK, editor. Advances in quasi-experimental design and analysis. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–9. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: LEA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steiger JH. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–51. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan JR, Chen H, Manuck SB. The relationship between social status and atherosclerosis in male and female monkeys as revealed by meta-analysis. American Journal of Primatology. 2009;71:732–41. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Trevano FQ, Dell'Oro R, Bolla G, Cuspidi C, Arenare F, Mancia G. Neurogenic abnormalities in masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:537–42. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conen D, Bamberg K. Noninvasive 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hypertension. 2008;26:1290–9. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f97854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamarck TW, Polk DE, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Muldoon MF. The incremental value of ambulatory BP persists after controlling for methodological confounds: Associations with carotid atherosclerosis in a healthy sample. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamarck TW, Shiffman S, Wethington E. Measuring psychosocial stress using ecological momentary assessment methods. In: Contrada RJ, Baum A, editors. The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and heatlh. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 597–617. [Google Scholar]