Abstract

Because the benefits of immune checkpoint blockade may be restricted to tumors with pre-existing immune recognition, novel therapies that facilitate de novo immune activation are needed. DRibbles is a novel multi-valent vaccine that is created by disrupting degradation of intracellular proteins by the ubiquitin proteasome system. The DRibbles vaccine is comprised of autophagosome vesicles that are enriched with defective ribosomal products and short-lived proteins, known tumor-associated antigens, mediators of innate immunity, and surface markers that encourage phagocytosis and cross-presentation by antigen presenting cells. Here we summarize the rationale and preclinical development of DRibbles, translational evidence in support of DRibbles as a therapeutic strategy in humans, as well as recent developments and expected future directions of the DRibbles vaccine in the clinic.

Keywords: DRibbles, DPV-001, Autophagy, Immunotherapy, Vaccine, Autophagosome, Cross-presentation, Bortezomib

Background: cross-priming and the DRibbles vaccine

A successful anti-tumor immune response by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells requires recognition of tumor antigen in the context of MHCI molecules. One potential explanation for how naïve T-cells become activated against tumor antigens is a process called cross-presentation. During cross-presentation, professional antigen presenting cells (pAPCs) phagocytose tumor proteins, digest them with proteasomes, and present them via MHCI to T cells for activation. Two hypothesized classes of tumor-associated proteins—called defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) and short-lived proteins (SLiPs)— are produced in abundance within tumor cells, however are inherently unstable and only expressed transiently under physiologic conditions before being poly-ubiquitinated and degraded by tumor cell proteosomes [1]. These tumor-associated DRiPs/SLiPs, while expressed frequently on tumor MHCI, would be inefficiently cross-presented by pAPCs, possibly because they are degraded before they reach the APCs. It has been hypothesized that these DRiPs/SLiPs antigens, if delivered to pAPCs for cross-presentation, could potentially facilitate anti-tumor immune responses and could form the basis of a novel anti-tumor vaccine.

Here, we introduce the DRibbles vaccine product, which is produced by simultaneously blocking proteosomal degradation and manipulating the cellular autophagy pathway, leading to stabilization of DRiPs/SLiPs proteins and formation of autophagosome microvesicles that contain not only DRiPs/SLiPs, but also other protein products that have been shown to facilitate cross-presentation. These autophagosomes are then harvested by membrane disruption and fractionation to create the vaccine called DRibbles. Here, we summarize the preclinical data supporting the DRibbles vaccine, translational evidence in support of its efficacy in humans, and completed and ongoing clinical trials of DRibbles across a variety of malignancies.

In the lab: preclinical development of the DRibbles vaccine

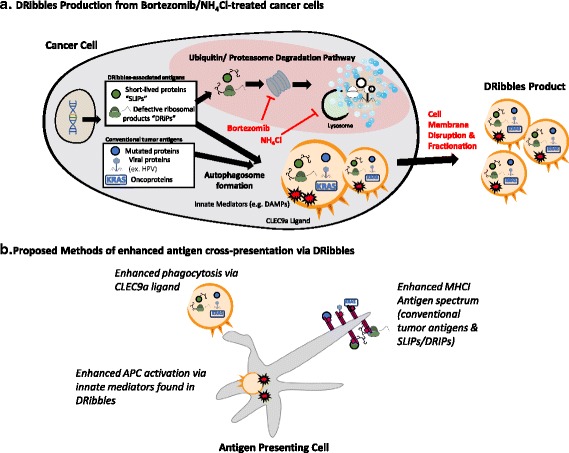

Evidence supporting the utility of the DRibbles concept for priming T cell responses was first demonstrated in a series of in vitro experiments using a modified OVA-expressing HEK 293 T tumor cell model [2]. The OVA gene was engineered to produce “short-lived” OVA proteins that would become poly-ubiquinated and degraded by proteasomes under physiologic conditions [2, 3]. Whole cells were treated with bortezomib (Velcade®, Takeda, Osaka, Japan) and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), which block proteasome activity and lysosomal digestion of autophagosomes, respectively. Then, the treated cells were mechanically disrupted and fractionated by centrifugation to harvest an autophagosome-enriched product (Fig. 1a). This product was termed “DRibbles,” an acronym for “DRiPs and SLiPs-containing blebs.” The short-lived OVA proteins were found to be enriched in this DRibbles autophagosome product, compared to non-treated cells or non-disrupted bortezomib/NH4Cl-treated cells. Furthermore, DRibbles vaccine was superior in priming OVA-specific T cells compared to non-treated or non-disrupted cells. These data suggested that DRibbles could be an effective vaccine against endogenous tumor-associated short-lived proteins.

Fig. 1.

The DRibbles vaccine product is generated by manipulating the endogenous autophagy pathway, and is comprised of autophagosomes that contain antigens was well as mediators of innate immunity and phagocytosis

Next, the DRibbles vaccine was evaluated for in vivo efficacy. DRibbles can either be produced based on an autologous concept (i.e. making the vaccine from a patient’s own tumor) or an allogeneic concept (i.e. making an “off-the-shelf” vaccine from one or more tumors to be administered to many patients). To model the autologous concept, DRibbles vaccine was generated from a 3LL Lewis lung cancer cell line and was shown to delay tumor growth and improve survival in that cancer model [4]. Next, to model the allogeneic concept, DRibbles vaccine was generated from multiple implantable methylcholantherene (MCA)-induced sarcoma cell lines. The long-standing paradigm was that whole-cell MCA vaccine would be effective only against homologous tumors [5]. However, vaccination with DRibbles derived from unrelated MCA-induced sarcomas was also effective in slowing tumor growth of other, independently-derived MCA sarcomas [3]. T cells isolated from these mice released interferon gamma against both homologous and independently-derived tumors, suggesting they had been cross-primed to a broader array of antigens present across a variety of sarcomas. This phenomenon was called ‘cross-protection,’ and provided evidence that an allogeneic DRibbles vaccine might serve as an “off-the shelf” vaccine in the clinic.

Further work was conducted to characterize components of the DRibbles vaccine. It was confirmed in various cell lines that DRibbles contain long-lived proteins (i.e. proteins not destined for rapid poly-ubiquitination and degradation), and are enriched for short-lived proteins, short-protein fragments, and poly-ubiquitinated proteins [4]. In addition to these potential antigens, the murine DRibbles product contained various damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signals including heat shock proteins, high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) and calreticulin, suggesting that DRibbles could potentially mediate both adaptive and innate immunity. Finally, the DRibbles autophagosome surfaces were found to contain CLEC9A ligands, which have been shown to bind CLEC9A receptor [6] and facilitate antigen uptake by a subset of dendritic cells that play an important role in cross-presentation [7] (Fig. 1b). In summary, DRibbles was found to be composed of microvesicles that efficiently deliver a variety of antigens to pAPCs in ways that traditional liposomal and cellular vaccines do not.

Bench to bedside: translational data regarding the DRibbles vaccine

The results of this characterization, combined with the promise of ‘cross-protection’, led to the development of various human DRibbles autophagosome vaccine formulations for the treatment of human subjects. The first allogeneic human DRibbles vaccine, named DPV-001, was derived from autophagosome products of two human cancer cell lines: UbiLT3 and UbiLT6. UbiLT3 was derived from a non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) of mixed histology, whereas UBiLT6 was derived from an NSCLC adenocarcinoma. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and western blotting techniques have been used to quantitatively catalogue over 2400 of the most common protein constituents in DPV-001. Of these most common proteins, there are over 25 published cancer-associated antigens, including at least 12 proteins that are among the NCI’s list of prioritized cancer antigens [8] such as TP53, survivin, EphA2, cyclin B1, XAGE1, Her2/neu, RhoC, Mesothelin, Legumain, PDGFRb, FOSL1 and KRAS [9].

Whole exome sequencing was used to show that many of the UBiLT3/6 genes are mutated or polymorphic versus the reference human genome (hg19). Thus, the DPV-001 DRibbles vaccine likely contains protein variants that are foreign to vaccinated patients. The UbiLT3/6 sequences were compared to 520 unique lung adenocarcinoma sequences from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [10]. In addition to containing commonly observed oncogene mutations (for example KRAS G12C, found in 6.8 % of adenocarcinomas in TCGA, http://www.cbioportal.org/index.do, accessed February 6, 2016), the UbiLT3/6 cell lines also shared polymorphisms with the identified non-synonymous mutations from each lung adenocarcinoma in the TCGA. This suggests that DRibbles may serve as an off-the-shelf vaccine against “private antigens” found in individual patients. Furthermore, non-exact foreign protein variants (for example other KRAS G12 codon point mutations) may function as altered-peptide ligands which stimulate immune responses that spread to a patient’s own tumor-specific neo-epitopes [11, 12].

In the clinic: development of human DRibbles vaccines

In humans, the DRibbles vaccine was first evaluated as an autologous vaccine manufactured with tumor cells isolated from pleural effusions of patients with NSCLC. In this phase I clinical trial, autologous DRibbles vaccine was found to be safe when combined with docetaxel plus GM-CSF [13]. Autologous DRibbles vaccines, while providing a potential opportunity to vaccinate against patient-specific neo-epitopes, have proven difficult to manufacture consistently. Furthermore, a recent study suggested that in melanoma patients, CD8+ T cells may more frequently recognize non-mutated antigens such as NY-ESO-1 and GP100, rather than neoepitopes [14]. Subsequent trials have focused on allogeneic DRibbles products, which contain numerous non-mutated self-antigens. Studies are underway to evaluate the role of allogeneic DRibbles in malignancies such as prostate adenocarcinoma and NSCLC (Table 1). These studies are also assessing the DRibbles vaccine in conjunction with low-dose cyclophosphamide and various adjuvants such as topical imiquimod or GM-CSF.

Table 1.

Summary of preclinical, translational, and clinical evidence of the DRibbles vaccine

| In the Lab | Bench to Bedside | In the Clinic |

|---|---|---|

| • DRibbles vaccine comprises autophagosome-packaged cellular proteins, short-lived proteins and ribosomal proteins that may be missed by endogenous immunity | • The DPV-001 DRibbles contains over 2,000 proteins, of which 25 are known tumor-associated antigens | • Dribbles vaccine + docetaxel was well tolerated in a phase I NSCLC trial |

| • DRibbles delays growth in both “autologous” and “allogeneic” pre-preclinical models | • The DPV-001 cell lines contain thousands of mutations and polymorphisms that could function as altered-peptide ligands | • A Phase II trial comparing DRibbles + either GM-CSF or Imiquimod in stage IIIA/B NSCLC is ongoing |

| • DRibbles contains innate immunity mediators (DAMPs) and surface ligands for CLEC9a, which facilitate uptake by APCs for cross-presentation | • Each lung adenocarcinoma sequence from the TCGA database shares at least one mutation with the polymorphisms found in DPV-001 | • A Phase I trial of DRibbles + imiquimod + low-dose cyclophosphamide is ongoing |

| • DPV-001 contains common oncogene mutants such as KRAS G12C | • DRibbles induced increased antibody reactivity in the first 2 patients treated on a phase II trial |

In addition to DRibbles, a multitude of clinical trials are underway evaluating safety and anti-tumor efficacy of other modulators of autophagy such as hydroxychloroquine and alpha-tocopheryloxyacetic acid (alpha-TEA) [15–17]. Besides DRibbles, there are reports of alternative potentially effective cell-derived vesicle vaccines. For example, melanoma patients have been treated with an autologous product of dendritic cell-derived exosomes pulsed with tumor antigen peptides [18]. More recently, another group has shown that tumor-derived exosomes could be a more effective method for priming anti-tumor immune responses compared to tumor lysate alone [19].

One major barrier for all cancer vaccine clinical trials is the difficulty in demonstrating efficacy in early stage disease, especially in tumor types with low recurrence rates or prolonged latency periods. Therefore, scientifically grounded immune monitoring strategies must be used to inform early development of vaccines, allowing for smaller trials designed to facilitate optimization of the vaccine and perhaps identify indirect evidence of efficacy. Because DRibbles vaccines are multi-valent, and because relevant antigenic targets may vary across patients, next-generation high-throughput technologies such as seromic protein arrays are being used to evaluate patient-specific immune responses and discover relevant antigens. The phase II non-small cell lung cancer DRibbles adjuvant trial serves as an example of how a seromics-based approach might be used to monitor immune response. This trial was designed to detect enhancement in antigen-specific adaptive immunity using serum protein arrays that measure antibody reactivity against a panel of over 8,000 normal human protein isoforms. The rationale is that the most robust immune responses might be integrated with concomitant CD4 T-helper, CD8 cytotoxic, and humoral immune responses [20], and therefore antibody reactivity may serve to identify antigen-specific immune responses associated with therapy. Using the protein array, several of the 9 treated DRibbles patients were found to exhibit robust (i.e. >10-fold increase from baseline) antibody responses to multiple antigens following vaccination [10].

Conclusion

The DRibbles vaccine serves as an excellent example of how basic immunology research can be translated into a promising approach in the clinic. Because the DRibbles platform can be used to generate either autologous or allogeneic vaccines derived from any tumor cell line, it may have clinical applications across a broad range of malignancy types. Relative to peptide and DNA vaccines, the DRibbles autophagosome-enriched vaccine platform may serve to vaccinate broadly against a spectrum of antigen types including potential neo-epitopes and a short-lived/defective cellular proteins that may not be present in other complex cell-derived cancer vaccines. Additionally, molecules such as CLEC9a ligand encourage uptake of DRibbles by cross-presenting pAPCs—a property not present in traditional liposome or microvesicle vaccine formulations. Because of these unique features, the DRibbles construct may in the future be investigated as a delivery mechanism for other vaccines, such as personalized patient-specific cancer neo-epitope peptides.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Alpha-TEA

Alpha-tocopheryloxyacetic acid

- DAMP

Damage-associated molecular pattern

- DRiPs

Defective ribosomal products

- HMGB1

High-mobility group box 1

- MCA

Methylcholantherene

- NH4Cl

Ammonium chloride

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung carcinoma

- pAPC

Professional antigen presenting cell

- SLiPs

Short-lived proteins

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Footnotes

Competing interests

H-MH and BAF are cofounders of UbiVac, which has licensed the autophagosome intellectual property. TLH is an employee of UbiVac. No non-financial competing interests exist for any of the authors.

Authors’ contributions

DBP and TWH conducted the literature review, wrote the manuscript, and designed the figures. TLH, HMH, WJU, and BAF edited the review and made critical revisions. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

David B. Page, Phone: 503-215-7807, Email: david.page2@providence.org

Tyler W. Hulett, Email: tyler.hulett@providence.org

Traci L. Hilton, Email: traci.hilton@ubivac.com

Hong-Ming Hu, Email: hong-ming.hu@providence.org.

Walter J. Urba, Email: walter.urba@providence.org

Bernard A. Fox, Email: bernard.fox@providence.org

References

- 1.Yewdell JW, Reits E, Neefjes J. Making sense of mass destruction: quantitating MHC class I antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nri1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Wang LX, Yang G, Hao F, Urba WJ, Hu HM. Efficient cross-presentation depends on autophagy in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6889–6895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twitty CG, Jensen SM, Hu HM, Fox BA. Tumor-derived autophagosome vaccine: induction of cross-protective immune responses against short-lived proteins through a p62-dependent mechanism. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6467–6481. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Wang LX, Pang P, Cui Z, Aung S, Haley D, Fox BA, Urba WJ, Hu HM. Tumor-derived autophagosome vaccine: mechanism of cross-presentation and therapeutic efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7047–7057. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prehn RT, Main JM. Immunity to methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1957;18:769–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sancho D, Joffre OP, Keller AM, Rogers NC, Martinez D, Hernanz-Falcon P, Rosewell I, Reis e Sousa C. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature. 2009;458:899–903. doi: 10.1038/nature07750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi Y, Zhou Z, Shu S, Fang Y, Twitty C, Hilton TL, Aung S, Urba WJ, Fox BA, Hu HM, Li Y. Autophagy-assisted antigen cross-presentation: Autophagosome as the argo of shared tumor-specific antigens and DAMPs. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:976–978. doi: 10.4161/onci.20059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, Finn OJ, Hastings BM, Hecht TT, Mellman I, Prindiville SA, Viner JL, Weiner LM, Matrisian LM. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton TL, Hulett TW, Dubay C, van de Ven R, Aung S, Urba W, Hu HM, Fox BA. SITC 28th Annual Meeting; November 8–10, 2013; National Harbor, MD. 2013. DPV-001 an autophagosome-enriched cancer vaccine in phase II clinical trials contains 25 putative cancer antigens, DAMPS, HSPS and agonists for TLR 2, 3, 4, 7 and 9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilton TL, Sanborn R, Boulmay B, Li R, Spieler B, Happel K, Paustian C, Moudgil T, Dubay C, Fisher B, et al. SITC 29th Annual Meeting; November 6–9, 2014; National Harbor, MD. 2014. Preliminary analysis of immune responses in patients enrolled in a Phase II trial of Cyclophosphamide with Allogenic DRibble Vaccine Alone (DPV-001) or with GM-CSF or Imiquimod for adjuvant treatment of Stage IIIA or IIIB NSCLC. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijer SL, Dols A, Jensen SM, Hu HM, Miller W, Walker E, Romero P, Fox BA, Urba WJ. Induction of circulating tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells after vaccination of melanoma patients with the gp100 209-2M peptide. J Immunother. 2007;30:533–543. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3180335b5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker EB, Haley D, Miller W, Floyd K, Wisner KP, Sanjuan N, Maecker H, Romero P, Hu HM, Alvord WG, et al. gp100(209-2M) peptide immunization of human lymphocyte antigen-A2+ stage I-III melanoma patients induces significant increase in antigen-specific effector and long-term memory CD8+ T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:668–680. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0095-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanborn RE. 15th World Conference on Lung Cancer; 10/30/2013; Sydney, Australia. 2013. A pilot single institution study of autologous tumor autophagosome (DRibble) vaccination with docetaxel in patients (pts) with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Ilyas S, Prickett TD, Gartner JJ, Crystal JS, Roberts IM, et al. Prospective identification of neoantigen-specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Takahashi A, Isaka Y. Chloroquine in cancer therapy: a double-edged sword of autophagy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebovitz CB, DeVorkin L, Bosc D, Rothe K, Singh J, Bally M, Jiang X, Young RN, Lum JJ, Gorski SM. Precision autophagy: Will the next wave of selective autophagy markers and specific autophagy inhibitors feed clinical pipelines? Autophagy. 2015;11:1949–1952. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1078962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Hahn T, Garrison K, Cui ZH, Thorburn A, Thorburn J, Hu HM, Akporiaye ET. The vitamin E analogue alpha-TEA stimulates tumor autophagy and enhances antigen cross-presentation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3535–3545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escudier B, Dorval T, Chaput N, Andre F, Caby MP, Novault S, Flament C, Leboulaire C, Borg C, Amigorena S, et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: results of thefirst phase I clinical trial. J Transl Med. 2005;3:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gu X, Erb U, Buchler MW, Zoller M. Improved vaccine efficacy of tumor exosome compared to tumor lysate loaded dendritic cells in mice. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E74–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan J, Adamow M, Ginsberg BA, Rasalan TS, Ritter E, Gallardo HF, Xu Y, Pogoriler E, Terzulli SL, Kuk D, et al. Integrated NY-ESO-1 antibody and CD8+ T-cell responses correlate with clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16723–16728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]