Abstract

Background

Human brucellosis cases are still reported each year in Sweden despite eradication of the disease in animals. Epidemiological investigation has never been conducted to trace back the source of human infection in the country. The purpose of the study was to identify the source of infection for 16 human brucellosis cases that occurred in Sweden, during the period 2008–2012.

Results

The isolates were identified as Brucella melitensis and MLVA-16 genotyping revealed 14 different genotypes of East Mediterranean and Africa lineages. We also reported one case of laboratory-acquired brucellosis (LAB) that was shown to be epidemiological linked to one of the cases in the current study.

Conclusions

Brucella melitensis was the only species diagnosed, confirming its highest zoonotic potential in the genus Brucella, and MLVA-16 results demonstrated that the cases of brucellosis in Sweden herein investigated, are imported and linked to travel in the Middle East and Africa. Due to its zoonotic concerns, any acute febrile illness linked to recent travel within those regions should be investigated for brucellosis and samples should be processed according to biosafety level 3 regulations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2074-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Brucellosis, Brucella melitensis, MLVA

Background

Brucellosis is one of the most reported zoonosis worldwide with an emergence of new foci of both human and animal disease related to socio economic changes [1]. Human-human transmission has occasionally been reported [2]. Transmission mainly occurs through the ingestion of contaminated raw milk and dairy products, via professional exposure, or via accidental inhalation of the Brucella culture [3, 4]. In human beings the disease is a septicemic febrile illness frequently associated with localized bone and tissue infections [5]. In animals it causes abortion and fertility problems resulting in considerable financial losses [6]. Brucellosis occurs widely throughout the world, particularly in developing countries where small ruminants are farmed. The diagnosis of Brucella is a challenge, and in low risk countries, the gold standard method used is the microbiological isolation from clinical samples. However, due to its pathogenicity, a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory must be used to handle potentially positive samples. Brucella infection is one of the major common laboratory-acquired infections in the United States [7]. In these cases inhalation of infective aerosol is the most common route of transmission, but direct contact with clinical specimens should not be ignored [8]. Brucellosis is a rare infection in humans in the EU. The highest notification rates and the majority of the autochthonous cases were reported from Mediterranean countries. Brucellosis in livestock has been eradicated in Sweden, but a number of human cases are registered annually from individuals that have travelled in brucellosis risk zones [9]. Commonly in Sweden, the brucellosis cases are found among travellers returning from endemic countries. Nevertheless, the febrile cases are rarely investigated for brucellosis in the absence of suspected anamnesis. This is the first study in Sweden in which brucellosis is studied in relation to the geographic source. We confirmed the diagnosis and we identified the source of infection for 16 cases of brucellosis detected over a four-year period (2008–2012) by means of PCR typing and MLVA genotyping. Here we applied MLVA in order to understand the geographic origin of the cases, and if there were clusters of infection as a result of food poisoning. Our findings revealed that all 16 cases of human brucellosis in Sweden studied were caused by B. melitensis lineages originating from the Middle East and Africa. A paradigmatic case of laboratory-acquired brucellosis (LAB) is also described pointing out the necessity of raising awareness in Sweden for contagious risk in laboratory staff.

Results

All isolates were initially cultured on sheep blood agar and DNA was prepared using the commercially available EZ1 DNA Tissue kit (Qiagen, Stockholm, Sweden). The AbortusMelitensisOvisSuis (AMOS) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used for identifying the Brucella species, prior to multiplex PCR [10, 11]. Then isolates were genotyped using the MLVA-16 panel of Le Flèche et al. [12] with modifications as described by Al Dahouk et al. [13]. We used the MLVA-16 protocol that uses multiplex PCRs and multicolour capillary electrophoresis [14], [15]. The MLVA data of the 16 strains were compared to genotypes from isolates available in the MLVA bank on the website (http://mlva.u-psud.fr/). Phylogenetic and cluster analysis was performed using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) in PAUP* 4.0b [16] using the allele data analyzed as alpha codes, aggregating the MLVA data from this study with MLVA data from the East Mediterranean and Africa lineages.

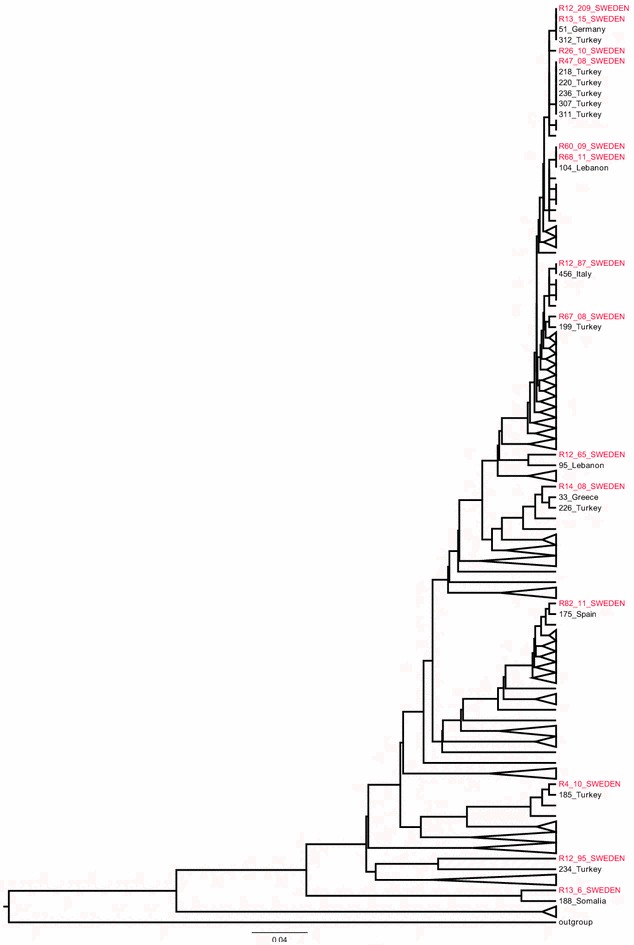

AMOS PCR assigned all the 16 strains to the B. melitensis species, which is highly pathogenic to humans. MLVA genotyping identified 14 different genotypes designated with the letters from A to N (Table 1, Additional file 1) [13, 17, 18]. The B. melitensis R13_15 strain was cultured from a sample provided by a laboratory trainee (a 38-year-old female) after she began experiencing nonspecific symptoms of malaise. Three months previously she had handled a suspicious sample (later identified as strain R12_209) in a BSL-2 laboratory. No evidence of exposure to brucellosis, other than through occupational exposure, was identified. The epidemiological investigation showed that the trainee performed gram staining while other laboratory staff performed phenotypical tests, but at that time all of them were unaware that they were dealing with Brucella. The culture was then sent to the Public Health Agency of Sweden, where Brucella was readily identified by culture, real time PCR, and matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF). The R12_209 strain was isolated from a 65-year-old man with a febrile illness after returning to Sweden from Iraq in October 2012. MLVA linked the strains R13_15 and R12_209 showing a similar genotype (Table 1). Two additional strains R60_09, R68_11 also had similar genotypes and were isolated from patients moved from Kurdistan (Iraq) but in different years without any apparent connection. Interestingly five out of fourteen MLVA-16 genotypes (A, C, J, K, and N) were previously identified from other authors in patients with recent history of travelling from brucellosis high risk areas. Moreover MLVA searching in the cooperative database of the MLVA bank revealed that the B. melitensis R13_6 strain, isolated from a patient moved from Somalia, belonged to the Africa lineage, while the remaining B. melitensis strains showed the East Mediterranean lineage for the patients with nationalities from different Middle East countries. The UPGMA clustering method revealed that all the isolates were diverse and widely distributed throughout the B. melitensis phylogeny (Fig. 1). The findings demonstrated a multi foci of infection with potentially different geographic sources.

Table 1.

Brucella melitensis isolates studied

| Strain id | Year | Patient nationality | Species | Lineage | MLVA8a | MLVA11b | MLVA16 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R12_209 | 2012 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | A | Exact match with human strains from Germany as introduction from Turkey [13], and from Turkey [18] |

| R12_65 | 2012 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | Novel | B | |

| R12_87 | 2012 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | C | Exact match with human strain from Italy as introduction from Syria [14] |

| R12_95 | 2012 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | Novel | Novel | D | |

| R13_15 | 2013 | Swedish | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | A | Exact match with human strains from Germany as introduction from Turkey [13], and from Turkey [18] |

| R13_6 | 2013 | Somali | B. melitensis | Africa | 94 | 178 | E | |

| R14_08 | 2008 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 106 | F | |

| R15_08 | 2008 | Syrian | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | G | |

| R26_10 | 2010 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | H | |

| R4_10 | 2010 | Afghan | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 63 | 111 | I | |

| R47_08 | 2008 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | J | Exact match with human strains from Turkey [18] |

| R60_09 | 2009 | Kurds | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | K | Exact match with human from Lebanon [17] |

| R67_08 | 2008 | Kurds | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | L | |

| R68_11 | 2011 | Kurds | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | K | Exact match with human from Lebanon [17] |

| R82_11 | 2011 | Iraqi | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 42 | 116 | M | |

| R95_11 | 2011 | Kurds | B. melitensis | East Mediterranean | 43 | 125 | N | Exact match with human strains from Turkey [13, 18] |

MLVA profiles are provided as Additional file 1

a, b MLVA8 and MLVA11 genotypes are designed according to the Brucella cooperative database of the MLVA bank, while MLVA16 genotypes are herein assigned with capital letters (A–N)

Fig. 1.

UPGMA assessment of relationships MLVA-16 profiles for 16 B. melitensis isolates from Sweden and 455 B. melitensis of West Mediterranean and Africa lineages available from MLVA bank. Swedish isolates are highlighted in red, other strains are identified by progressive numbers and geographic source. The branches unrelated are collapsed

In this study we confirm that MLVA continues to demonstrate its effectiveness as a molecular epidemiological tool of bacterial pathogens such as Brucella [15]. The specific level of discrimination offered by VNTRs methodology has put them as gold standard markers in the field of molecular epidemiology. MLVA typing is therefore useful to understand the epidemiological context where the cases are occurring. MLVA has been used to confirm the source of a LAB [19] as well as to demonstrate the endemicity or distinct clusters of disease [15]. The genetic fingerprints found demonstrate that the 16 B. melitensis isolates reported in this study are linked to Middle East and African areas, in agreement with a previous publication [20]. Unfortunately, case information is not available for our isolates, but recent immigration or travel from countries with endemic brucellosis might be a common feature for all patients as corroborated by patient nationalities (Table 1). The genetic lineages discovered put the root of the infections in the Middle East and Africa and this reflects the Swedish migration trends of groups from Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia (source: Statistics Sweden).

Our data demonstrates that in Sweden, human brucellosis may be linked to people with a characteristic anamnesis with recent migration from brucellosis endemic areas. The majority of cases in northern Europe are travel associated. In addition, European countries may also experience domestically acquired cases. These can occur in immigrants from endemic areas or be due to private import of unpasteurized dairy products from endemic areas. Food-borne brucellosis would act as a point cluster disease but the high genetic diversity found would exclude the presence of such food poisoning clusters in our cases.

A laboratory-acquired infection was also traced back by MLVA confirming the suspected epidemiological link between the lab trainee and the brucellosis case. BSL-2 laboratory practices can potentially lead to Brucella infections.

It is therefore extremely important to put brucellosis in the differential diagnosis of any acute febrile illness, especially in individuals who have recently moved or travelled from such areas. In those cases, microbiologists working with suspected cases of Brucella must follow BSL-3 standards microbiological safety procedures to minimize the risk of infection.

Authors’ contributions

GG and TW have designed the study and drafted the final manuscript, AF and EDG contributed in planning of the project, IP, LS, TP, TB performed molecular and conventional tests for Brucella, TW and KR performed MALDI-TOF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Romanico Arrighi for critical reading of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The MLVA data are accessible in the Additional file 1 and at MLVA bank on the website (http://mlva.u-psud.fr/).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a retrospective molecular investigation of the Brucella historical collection from the Public Health Agency of Sweden. No human patients data were used therefore informed consent was not required.

Funding

The work was partially supported by the EU Joint Action QUANDHIP, EAHC contract number 2010 21 02/A-100 905 and partially by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, project “mass spectrometry for detection and typing of bio terror agents and zoonosis”. Funding for GG, EDG, TP, LS and IP from Italian Ministry of Health project IZS AM 03/11 RC also supported this work.

Abbreviations

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SPP

species

- VNTR

variable number tandem repeat

- MLVA

multi locus VNTRs analysis

- BSL

biosafety level

- AMOS

Abortus Melitensis Ovis Suis

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight

- UPGMA

unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean

- LAB

laboratory-acquired brucellosis

Additional file

10.1186/s13104-016-2074-7 MLVA profiles for the B. melitensis analyzed in this study.

Contributor Information

Giuliano Garofolo, Phone: +390861332411, Email: g.garofolo@izs.it, Email: garofolo.giuliano@gmail.com.

Antonio Fasanella, Email: a.fasanella@izsfg.it.

Elisabetta Di Giannatale, Email: e.digiannatale@izs.it.

Ilenia Platone, Email: i.platone@izs.it.

Lorena Sacchini, Email: lo.sacchini@izs.it.

Tiziana Persiani, Email: t.persiani@izs.it.

Talar Boskani, Email: talar.boskani@folkhalsomyndigheten.se.

Kristina Rizzardi, Email: Kristina.rizzardi@folkhalsomyndigheten.se.

Tara Wahab, Email: tara.wahab@folkhalsomyndigheten.se.

References

- 1.Pappas G. The changing Brucella ecology: novel reservoirs, new threats. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(Suppl 1):S8–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfroid J, Cloeckaert A, Liautard J-P, Kohler S, Fretin D, Walravens K, et al. From the discovery of the Malta fever’s agent to the discovery of a marine mammal reservoir, brucellosis has continuously been a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Res. 2005;36(3):313–326. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young EJ. Human brucellosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(5):821–842. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali S, Ali Q, Neubauer H, Melzer F, Elschner M, Khan I, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with brucellosis as a professional hazard in Pakistan. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2013;10(6):500–505. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2325–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seleem MN, Boyle SM, Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3–4):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding ALBK. Epidemiology of laboratory-associated infections. In: Fleming DO, Hunt DL, editors. Biological safety: principles and practices. 3. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yagupsky P, Baron EJ. Laboratory exposures to brucellae and implications for bioterrorism (vol 11, pg 1184, 2005) Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(11):1808. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.041197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EFSA. ECDC The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA Journal. 2015;13(1):162. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32(11):2660–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Enhancement of the Brucella AMOS PCR assay for differentiation of Brucella abortus vaccine strains S19 and RB51. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(6):1640–1642. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1640-1642.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Flèche P, Jacques I, Grayon M, Al Dahouk S, Bouchon P, Denoeud F, et al. Evaluation and selection of tandem repeat loci for a Brucella MLVA typing assay. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Dahouk S, Flèche PL, Nöckler K, Jacques I, Grayon M, Scholz HC, et al. Evaluation of Brucella MLVA typing for human brucellosis. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;69(1):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garofolo G, Ancora M, Di Giannatale E. MLVA-16 loci panel on Brucella spp. using multiplex PCR and multicolor capillary electrophoresis. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;92(2):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garofolo G, Di Giannatale E, De Massis F, Zilli K, Ancora M, Camma C, et al. Investigating genetic diversity of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis in Italy with MLVA-16. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;19:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods), version 4.0. 2002.

- 17.Kattar MM, Jaafar RF, Araj GF, Le Flèche P, Matar GM, Abi Rached R, et al. Evaluation of a multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis scheme for typing human Brucella isolates in a region of brucellosis endemicity. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(12):3935–3940. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00464-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiliç S, Ivanov IN, Durmaz R, Bayraktar MR, Ayaslioglu E, Uyanik MH, et al. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis genotyping of human Brucella isolates from Turkey. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9):3276–3283. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02538-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marianelli C, Petrucca A, Pasquali P, Ciuchini F, Papadopoulou S, Cipriani P. Use of MLVA-16 typing to trace the source of a laboratory-acquired Brucella infection. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(3):274–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aftab H, Dargis R, Christensen JJ, Le Flèche P, Kemp M. Imported brucellosis in Denmark: molecular identification and multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) genotyping of the bacteria. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(6–7):536–538. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.562531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The MLVA data are accessible in the Additional file 1 and at MLVA bank on the website (http://mlva.u-psud.fr/).