Abstract

Primary care physicians must understand and effectively communicate to their patients with depression the importance and process of managing the illness because these clinicians are usually the first to diagnose and treat patients with depression, especially depression with physical symptoms. Diagnosing and treating depression presents physicians and patients with a number of challenges, many of which arise because doctors and patients do not share enough information with one another. To improve the management of depression, physicians should explain how depression is diagnosed, how the individual's depression will be treated, how treatment success is defined, what treatment side effects might occur and how they will be addressed, and why adhering to the treatment regimen is important. Unfortunately, patients might not remember everything their physicians say during office visits, and physicians might forget to mention some instructions. To make sure that patients understand as much about depression and its treatment as possible, physicians should provide patients with resources such as pamphlets, videotapes, names of books, and Web site addresses and, if possible, enlist a mental health professional to educate the patient and provide psychotherapy. Physicians should encourage patients to become actively involved in their treatment by recording their symptoms, goals of therapy, side effects, and changes in their condition and by voicing their concerns. If primary care physicians and patients with depression improve their communication, they will ultimately strengthen the doctor-patient relationship and improve the patients' depressive symptoms and quality of life.

Because the first line of identification and management of depression, particularly depression with prominent somatic symptoms, is often primary care physicians, how well these doctors understand the disorder and communicate with their patients with depression will greatly impact the success of treatment. Unfortunately, patients and primary care physicians often do not communicate well with one another; therefore, many patients with depressive disorders including major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder with depressed or mixed mood, and dysthymia—which may be about 22% of primary care patients1—never receive the correct diagnosis and optimal treatment. For example, most patients with depression will not realize that the psychiatric disorder is the cause of their physical symptoms unless their doctors explain the nature of the illness to them. Once depression has been identified, if primary care physicians do not encourage patients to openly relay what symptoms and side effects they have during treatment and how well they are adhering to therapy, patients might experience little improvement in their depression. To give patients with depression the best quality of life possible, primary care physicians should understand the challenges that the disorder presents in the primary care setting and effectively communicate the importance and process of managing depression to their patients.

CHALLENGES IN DIAGNOSING AND TREATING DEPRESSION

Depression presents primary care physicians with myriad challenges related to the nature of the disorder and to physicians' and patients' preconceptions about depression and its treatment. For the physician, successful treatment of this disorder requires more proactive and systematic approaches to detection and management than does treatment of some chronic physical conditions such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Because depression is a psychiatric disorder, patients may also be less understanding of and more resistant to diagnosis and treatment than they would be if they had a physical illness.

Depression is less easily diagnosed than some physical conditions, and there is no objective test, such as a blood test, to confirm the presence of the disorder. Symptoms can vary greatly (e.g., from mood disturbance to physical complaints), can be contradictory (e.g., from hypersomnia to insomnia), and can present as or worsen other medical conditions (e.g., headaches, back pain from arthritis). The symptoms can be more disabling than those of many other medical conditions such as arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension.2

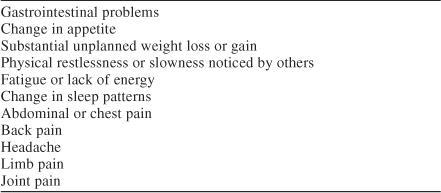

Somatic symptoms, which are frequently attributed to other conditions, are often the main reason that depressed patients seek treatment from their primary care physician. The World Health Organization conducted a study3 on somatic symptoms of depression at 16 primary care centers in 14 countries. Physical symptoms such as headache, back pain, weakness, fatigue, and constipation were the only reason that 69% of the 1146 patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder stated for coming to the center. The somatic symptoms listed in Table 1 might indicate depression if they occur almost every day and are not caused by another condition.

Table 1.

Somatic Symptoms That Might Indicate the Presence of Depression

Once the diagnosis is made, the treatment of depression requires monitoring the patient for clinical response, side effects, and compliance with the treatment regimen over at least 6 months. The need for long-term treatment for all depressed patients is often at odds with the fast pace and focus on acute care in most primary care practices and with patients' expectations for an immediate cure. For example, depression cannot be treated like an infection, with an antibiotic that is effective in about 7 days, but instead requires months and in many cases years of treatment.

Patients' ideas about depression often hinder their diagnosis and treatment. Depressed patients are often neither assertive nor informed and, therefore, may not clearly communicate symptoms. Patients who do express their complaints may be unaware of or unwilling to accept the true cause and may agree to diagnostic tests and treatment for only specific medical conditions. Ignoring the underlying psychiatric illness only compounds the problem and delays the initiation of effective treatment. Seeking and following through with care may be difficult for patients because of the social stigma attached to mental illnesses.

The success of therapy depends on patients' adherence to their treatment regimen. Poor adherence might be caused by a patient's refusal to accept the diagnosis and/or treatment plan, the medication's side effects, or the cost of treatment. When physicians clearly communicate to patients and their families the nature of depression as well as information about the treatment plan (including the duration and potential for side effects), the chances for recovery are substantially increased.

Communication Gap

Open and effective communication lies at the heart of the doctor-patient interaction and is the most important tool doctors have to diagnose depression, monitor the patient's progress during treatment, and predict patients' adherence to therapy and, ultimately, their response to treatment. Yet, studies have shown a significant communication gap between primary care physicians and patients that leads to suboptimal treatment and, therefore, suboptimal outcomes.

Poor communication might be the reason that many patients discontinue antidepressant treatment before they have experienced symptom improvement and reduced the likelihood of relapse. For patients who are experiencing their first episode of depression, antidepressant treatment should be continued for at least 4 to 5 months after depressive symptoms resolve to prevent relapse, according to guidelines by the American Psychiatric Association.4 However, many patients stop taking antidepressants long before the guidelines recommend. In a study by Lin and coworkers,5 44% of the 155 patients, who had been prescribed antidepressant therapy for depression by a primary care physician, discontinued treatment within 3 months after its start. Factors that cause patients to prematurely discontinue treatment include poor patient-physician communication, lack of family support, clinical response to therapy, and adverse effects. Research5–7 has shown that a strong treatment alliance between physicians, patients, and their families that includes discussions about the duration of treatment, expected improvement, and adverse effects can reduce patients' worry and the resulting premature discontinuation of medication treatment for chronic illnesses.

Effective communication can help patients continue antidepressant therapy, although studies7,8 have shown that discrepancies often exist in what physicians and patients remember about their interaction. In a recent study conducted in a managed care setting, Bull et al.7 found differences in what the 401 depressed patients remember being told and what their 137 physicians say that they routinely tell patients. When asked how long patients were advised to take antidepressants when therapy was introduced, 72% of the physicians but only 34% of the patients responded that the recommended length of treatment was 6 months or longer. Although the study did not determine whether the physicians had forgotten to specify the duration of treatment or patients had inaccurately recalled what they were told, the findings clearly showed that better communication between patients and physicians is needed.

Similarly, in the results of a landmark survey, the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association,8 now known as the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, found that primary care physicians and patients with depression had difficulty communicating about adverse effects and participation in treatment decisions. The percentage of physicians who said they address side effects with patients was substantially larger than the percentage of patients who said they were told about side effects. Some of the largest discrepancies were seen in the rates of reported discussion about sexual dysfunction (69% of the 881 physicians versus 16% of the 1001 patients) and weight gain (47% of the physicians versus 16% of the patients). Another problem was the lack of communication about whether side effects must be tolerated. Although 40% of the patients thought they must endure side effects, only 9% of the physicians agreed. Physicians and patients also disagreed about whether they collaborated on treatment decisions: 71% of physicians compared with 54% of patients felt that patients were involved.

Physicians might reduce the disparity between what they recall telling patients and what patients remember being told by developing a thorough plan for communicating with patients, as described below. If physicians bridge the communication gap, the outcomes of their depressed patients should improve.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Effective communication between physicians and patients is key to the successful treatment of patients with depression in the primary care setting. To improve adherence and outcomes, physicians should incorporate several important steps into their treatment of and communication with patients who are diagnosed with depression.

Explain the Diagnosis

When patients are diagnosed with depression, physicians should help patients to understand and accept the diagnosis. There are 3 main points the physician should convey to the patient. First, depression is a disorder with a physical basis that impacts one's emotional and physical condition. Second, depression is a medical condition and should not be viewed as shameful. Third, when the chemical imbalance and situational and life stresses that cause depression are reduced or eliminated, the patient's depressive mood and/or physical symptoms will get better.

Explain the Treatment Plan

Patients who know what to expect during treatment will be more likely to comply with their therapy and will be better able to take an active part in their care. Management of patients should include informing them, and ideally their close family or friends, about the following topics.

Treatment options.

Patients should know that finding the right medication and optimum dose for them might take months because each patient responds differently. When evaluating options, physicians should tell patients the indications, mechanisms of action, benefits, costs, and potential side effects of all therapies being considered.

Length of treatment.

Some patients want medication to be a quick fix or are uncomfortable with the idea of taking antidepressants for months or years. Therefore, physicians must give patients realistic expectations of how long medication treatment will last. Patients should know that depression is often a recurrent illness and that medication treatment should last for months, if not years. Acute treatment may take weeks to months to resolve both the physical symptoms and the depressed mood. Continued therapy for at least 4 or 5 months is required to prevent relapse, even for those patients who have had a single uncomplicated episode of depression. For patients who have had 3 or more episodes of major depression, maintenance therapy for at least 3 years and possibly a lifetime will decrease the incidence and severity of relapse.

Frequency of visits and follow-up contact.

When treatment first begins, physicians should meet with or telephone patients once every week or 2 weeks to address symptoms, side effects, and treatment compliance. During this time, the physician, the patient, and the family should watch for any suicidal ideation, and if it is present, explore whether it is active or passive in nature and whether the patient intends to act, has the means to act (e.g., weapons or medications), and has a plan or deadline for action. Patients should be reminded that if they do not take their medication as prescribed, their symptoms will not improve. If intolerable side effects occur or symptoms do not improve after 4 to 6 weeks, the medication might need to be switched. Once the patient is showing signs of a response to medication therapy, as determined by his or her unique symptoms and treatment goals, the treatment can be continued and the patient's progress checked again at 6 and 12 weeks.

Referral to a mental health professional.

If patients have experienced very little or no improvement after 12 weeks of medication treatment, referral to a psychiatrist should be considered. If referral to a psychiatrist is necessary, the patient, his or her family members, the primary care physician, and the psychiatrist should communicate with each other clearly and openly.

Discuss Side Effects

Patients need to understand that the medications used to treat depression, like medications used to treat many other medical conditions, have side effects. However, side effects can vary among patients or not occur at all. Before treatment is started, physicians should tell patients what specific side effects may occur and emphasize the importance of continuing the medication at the suggested dose until they can talk to the physician. The physician and the patient should identify which adverse effects might be most upsetting to the patient. Some side effects such as sexual dysfunction and weight gain may not seem crucial to the physician but may be extremely distressing to the patient.

At each encounter, physicians should ask patients whether they have experienced any side effects. If side effects have occurred, physicians should explain to patients how these side effects will be managed and, when possible, give patients concrete suggestions for dealing with them. For example, a common early side effect of antidepressants is nausea, but patients might manage this symptom by taking their medicine with food. If adverse effects are intolerable, changing the dose or switching to another medication may be necessary.

Explain Treatment Success and Failure

Patients (and their close family or friends, if possible) should understand how treatment success is defined and when it might be accomplished. Successful medication treatment of depression is defined as the complete or near-complete relief of mental and physical symptoms and the freedom from persistent or problematic medication side effects. Achieving the goals of therapy may take months and require changes to the medication dose. A medication trial of 4 to 6 weeks generally results in substantial symptom relief, and by 12 weeks, many—but not all—patients should have a full response to treatment. If after 4 to 6 weeks the patient shows little or no improvement, either a switch of medication or a change of dose and continued close follow-up are needed.

Treatment success is not accomplished until patients have maintained improvement on medication therapy for at least 4 to 5 months after symptoms have resolved. However, many patients decide to forego therapy and not return for follow-up visits once they begin to feel better. To prevent premature discontinuation, physicians must communicate to patients and their families the importance of continuing therapy, stressing the point when therapy begins as well as when symptoms have improved. During continuation therapy, physicians should work with patients to actively monitor treatment adherence and watch for signs of relapse. The best predictors of relapse are persistence of subthreshold symptoms and a history of recurrent, or chronic, depression. Patients should know that if they have residual symptoms, especially physical symptoms, they have a higher chance of future relapse. If symptoms persist, patients might need to increase their medication dose. Adjusting treatment for the patient's unique needs and maintaining full and open communication among the physician, patient, and family at all times are necessary for therapy to succeed.

Explain the Importance of Treatment Adherence

Patients should know that the risk of relapse substantially increases when they do not take their medication as prescribed during acute therapy and for at least 4 to 5 months after their symptoms are well controlled. Melfi and colleagues9 examined the influence of early medication discontinuation on the risk of relapse in 4052 depressed patients in a state Medicaid database. The patients who were poorly compliant, that is, filled fewer than 4 prescriptions for the same antidepressant during the first 6 months of treatment, had a 77% greater risk for relapse or recurrence than did the patients who adhered to the treatment regimen.

Physicians must address treatment adherence with patients throughout the course of therapy. When beginning a medication trial, the physician and patient should first identify the patient's potential difficulties in complying with treatment and then design strategies to handle these obstacles. For example, patients who know they have difficulty remembering to take medication might use a pillbox with a separate compartment for each dose that is labeled with the day of the week and the time of day. If patients no longer want to take medication when they feel better, physicians might highlight the connection between symptom improvement and medication by asking patients to chart how their mood has changed since they have been taking the antidepressant.

Use Multidisciplinary Treatment Approaches

Because many primary care practices are not well equipped to provide the long-term follow-up visits, education, and support that chronic illnesses such as depression require, the aid of mental health professionals might increase the quality of care for depressed patients. However, interventions that do not involve patients directly but are limited to primary care physicians' consulting psychiatrists about patients' symptoms and treatment may do little to improve patient outcomes.10 Disease management programs or systems interventions that actively include patients, like those that have been used successfully for chronic conditions such as diabetes and arthritis, may be useful in the treatment of depression. Studies11–13 have shown that programs that integrate a psychologist, psychiatrist, or other mental health practitioner into the primary care setting to provide education, symptom monitoring, short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy, and medication recommendations have led to improved adherence, outcome, and satisfaction, at least for the short term. The improved patient outcomes that result from intensive follow-up and frequent ongoing communication between the patient and physician can outweigh the cost of implementing multidisciplinary programs.

Get Patients Involved in Their Health Care

To be satisfied with their treatment and have the best possible health outcome, patients must actively collaborate with their doctor to manage their depression. Physicians should explain to patients how they can become informed about and involved in their health care.

Learn everything possible about depression, at an individualized pace.

Physicians can suggest key points for patients to research, which include the natural history of depression, the role of medication treatment, the importance of treatment adherence, anticipated therapy outcomes, the length of time medication will take to become effective, the risk of relapse and recurrence, potential medication side effects, and strategies for ameliorating side effects. To avoid feeling overwhelmed, patients should gradually gain this knowledge as their symptoms improve and they become better able to process information and make decisions. Because primary care physicians are often under great time constraints, patients might be referred to printed educational materials, a reliable Web site on depression, or a nurse practitioner or other health professional.

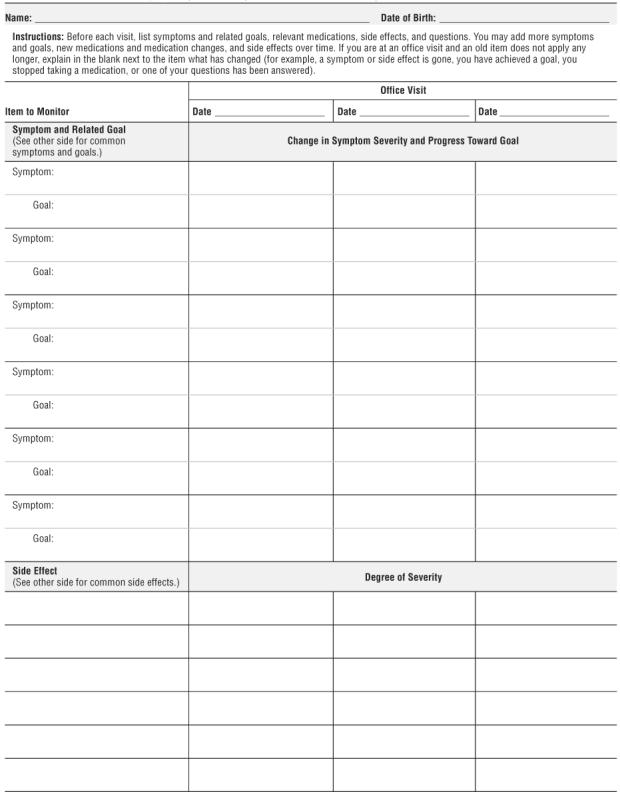

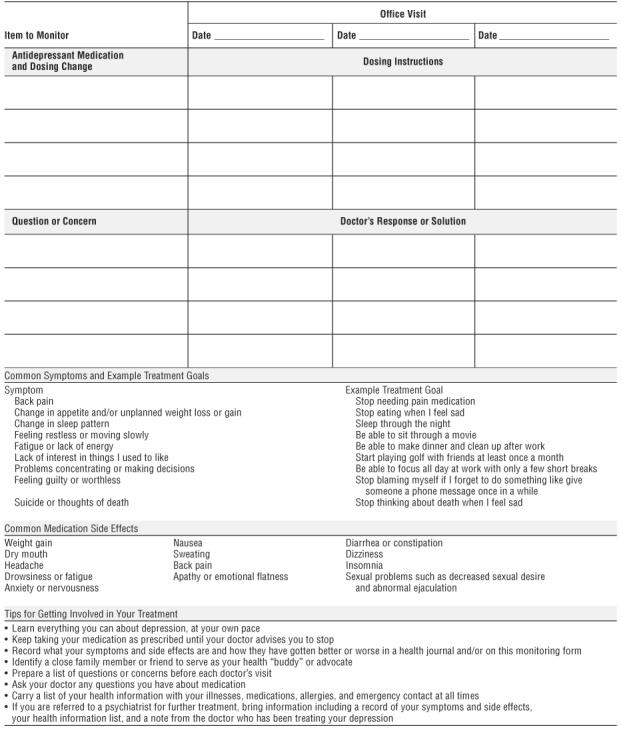

Record symptoms, side effects, and progress toward recovery.

Patients should keep track of their initial and current physical and emotional symptoms, vague complaints, side effects, functional status, quality of life measures, and any changes in their condition during therapy. Useful tools for recording this information are a personal health journal and a disease-monitoring form such as the Savard Form for Symptom, Side Effect, and Medication Monitoring (Appendix 1). For patients who are severely depressed, close family members or friends may need to keep the journal or complete the monitoring form until patients are ready to maintain the tools themselves. The benefits of using a monitoring tool are that depressed patients, who often forget how sick they were once they feel better and may therefore minimize their response to treatment, can easily see changes in their condition with medication and quickly relay this information to their physicians during office visits. Tracking symptoms, side effects, and progress can also help patients feel more in control and like a vital participant in their recovery.

Identify a close family member or friend to serve as a health “buddy” or advocate.

Patients, as well as physicians, will benefit from depressed patients teaming up with a close family member or friend who will help them comply with their medication regimen, monitor their symptom improvement and side effects, and prepare for doctor's visits. During office visits, the personal advocate can record answers to questions, any change in therapy, and the physician's explanations of symptoms. To prepare for the role of health advocate, the individual should receive the same detailed education about depression as the patient.

Prepare a list of questions or concerns before each office visit.

A major reason for patients' dissatisfaction with physicians' office visits occurs when patients forget to ask their important questions, and many depressed patients fail to remember every detail of their symptoms and concerns by the time they reach the doctor's office. Having patients prepare a written list of questions and concerns related to symptoms, treatment, and side effects before the visit (often with their health “buddy”) will prevent this problem. Instead of simply encouraging patients to write down their questions on their own, physicians should give patients a form to record their concerns because those who use a form may be more likely to ask questions, express fears and misunderstandings, and take initiative during their visits.14 At the beginning of the visit, the physician should ask to see the patient's list so that they are sure to cover what is most important to the patient. Patients can also use their list to write down physicians' treatment advice and record any treatment changes such as adjusted medication dose.

Ask about medication concerns.

Patients often wonder how to take their medication, e.g., how much to take, what time of day to take it, and what to do if they forget a dose. They might also worry about what adverse effects might occur and what they can do if they have any troublesome side effects, including what changes in diet, physical activity, or sleep patterns might help reduce side effects, as well as how they can reach their physician in an emergency. Another common question is how will they know when they should switch or stop medication. (The physician should remind the patient never to stop taking medicine without consulting the doctor, to prevent withdrawal symptoms.) Because depressed patients' concerns about medication, especially side effects, and bleak outlook can affect their compliance, they must be encouraged to ask for answers to their specific medication questions.

Carry a personal health information list at all times.

A patient's medical history and list of current medications is critical to making an accurate diagnosis and providing safe and effective treatment. Physicians should suggest that each patient create and frequently update a personal health information list that includes the patient's medical conditions, allergies or medication reactions, a complete list of current medications (both prescription and over-the-counter drugs as well as vitamins and herbal supplements) with the dosing directions, and an emergency contact. Patients should carry this list at all times, perhaps in their wallet next to their insurance card, and show the list to all health care practitioners they visit, especially before accepting a new prescription medication.

If referred to a psychiatrist for further treatment, come prepared with information.

The more prepared a patient is for a referral to a psychiatrist, the more useful the visit will be for the patient, the primary care physician, and the psychiatrist. Patients should bring their up-to-date personal health information list, health journal or monitoring form, and a list of important questions and concerns. The primary care physician should also give the patient a note or some other written form of communication for the psychiatrist that details the patient's condition and the reasons for referral. Having access to this information will help the specialist prepare to treat the patient with depression, who will often have multiple physical symptoms and a complex medical history.

CONCLUSION

Depression, especially depression manifested primarily by physical symptoms, is a common disorder that frequently presents in the primary care setting. The condition is associated with substantial suffering, functional impairment, diminished quality of life, frequent use of general medical services, and poor adherence to medical treatment. However, many patients are unaware that depression is the cause of their somatic symptoms. Physician-patient communication affects important health outcomes including information exchange and recall, reduction of distress, and improved satisfaction and treatment adherence. Substantial evidence demonstrates that effective communication with patients and others involved in their care such as a close family member or friend—along with appropriate medication and ongoing monitoring and support—is key to the successful treatment of depression. Therefore, primary care physicians should make sure their patients understand the disorder and its treatment and provide patients with opportunities to actively participate in their care.

Appendix 1.

Savard Form for Symptom, Side Effect, and Medication Monitoring

Footnotes

This article is derived from the teleconference “New Treatments for Depression Characterized by Physical Symptoms,” which was held May 15, 2003, and supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure of off-label usage: The author has determined that, to the best of her knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents has been presented in this article that is outside U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved labeling.

REFERENCES

- Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL. Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Stewart A, and Hays RD. et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989 262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, and Piccinelli M. et al. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999 341:658–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Von Korff M, and Lin E. et al. The role of the primary care physician in patient's adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995 33:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NH. Compliance with treatment regimens in chronic asymptomatic diseases. Am J Med. 1997 1022A. 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Hu XH, and Hunkeler EM. et al. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants. JAMA. 2002 288:1403–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association. Beyond Diagnosis: Depression and Treatment. A Call to Action to the Primary Care Community and People With Depression. Chicago, Ill: National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association. 2000 Available at: http://www.dbsalliance.org/pdf/beyonddiagnosis.pdf. Accessed Sept 26, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, and Croghan TW. et al. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 55:1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceroni GB, Rucci P, and Berardi D. et al. Case review vs. usual care in primary care patients with depression: a pilot study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002 24:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Robinson P, and Von Korff M. et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 53:924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman E, Von Korff M, and Katon W. et al. The design, implementation, and acceptance of a primary care-based intervention to prevent depression relapse. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2000 30:229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Rutter C, and Ludman EJ. et al. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 58:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Newton R. A question sheet to encourage written consultation questions. Qual Health Care. 2000;9:42–46. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]