Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the outcome of the second Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV) surgery in eyes with failed previous AGV surgery.

Design:

Retrospective case series.

Patients and Methods:

Following chart review, 36 eyes of 34 patients with second AGV implantation were enrolled in this study. The primary outcome measure was surgical success defined in terms of intraocular pressure (IOP) control using two criteria: Success was defined as IOP ≤21 mmHg (criterion 1) and IOP ≤16 mmHg (criterion 2), with at least 20% reduction in IOP, either with no medication (complete success) or with no more than two medications (qualified success). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to determine the probability of surgical success.

Results:

The average age of the patients was 32.7 years (range 4–65), and the mean duration of follow-up was 21.4 months (range 6–96). Preoperatively, the mean IOP was 26.94 mmHg (standard deviation [SD] 7.03), and the patients were using 2.8 glaucoma medications on average (SD 0.9). The mean IOP decreased significantly to 13.28 mmHg (SD 3.59) at the last postoperative visit (P = 0.00) while the patients needed even fewer glaucoma medications on average (1.4 ± 1.1, P = 0.00). Surgical success of second glaucoma drainage devices (Kaplan–Meier analysis), according to criterion 1, at 6, 12, 18, and 42 months was 94%, 85%, 80%, and 53% respectively, and according to criterion 2, was 94%, 85%, 75%, and 45%, respectively.

Conclusion:

Repeated AGV implantation seems to be a safe modality of treatment with acceptable success rate in cases with failed previous AGV surgery.

Keywords: Ahmed glaucoma valve, glaucoma, intraocular pressure

Glaucoma is a major cause of blindness worldwide.[1] Although in most patients with diagnosis of glaucoma medications are the mainstay of treatment, but in special circumstances such as congenital glaucoma, poor compliance to medication, and progressive disease surgical interventions (e.g., Trabeculectomy, glaucoma drainage devices [GDDs], and cyclodestructive procedures) become the treatment of choice. Surgical treatment trends in glaucoma have changed dramatically during the past decade. A web-based survey sent to members of the American Glaucoma Society revealed that the use of GDD has progressively increased and the popularity of trabeculectomy has decreased.[2] This is especially true in cases of neovascular glaucoma, previous failed trabeculectomy, previous penetrating keratoplasty, previous scleral buckling surgery, and uveitic glaucoma.[3] However, in long-term follow-up of patients with history of previous GDD implantation, we probably face an increasing number of patients with uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP), who need an additional surgical intervention.

After a failed shunt surgery, limited options to control the IOP such as cyclodestructive procedures, shunt revision, or implantation of the second valve to control IOP are conceivable. In general, cyclodestruction is deemed to be a treatment of the last resort owing to unpredictable success rates and severe complications such as vision loss and phthisis.[4] Revision of a tube shunt for bleb encapsulation has been shown to yield low success rates of 25% to 42%.[5,6] Shah et al. reported that after failed tube shunt surgery, an additional shunt implantation led to better IOP control than revision of encapsulated bleb.[7] In view of inadequate evidence in the literature, the present study was carried out to evaluate subsequent Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV) placement for glaucoma refractory to primary AGV placement.

Patients and Methods

By retrospective chart review, all patients who underwent secondary AGV insertion in a university hospital between December 2006 and March 2014 were identified. The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Patients with >6 months of follow-up after the second AGV surgery were enrolled. Those who had undergone a cyclodestructive procedure previously were excluded from the study. Demographic data as well as best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), IOP (measured by calibrated Goldmann applanation tonometry), slit lamp biomicroscopy, funduscopic findings (using 78 diopter lens), and number of glaucoma medications (including topical and oral agents preoperatively) and complications (if any) at the preoperative and every postoperative follow-up visits were recorded. The primary outcome measure was surgical success defined in terms of IOP control using two criteria: (1) 5 ≤IOP ≤21 mmHg with at least ≥20% reduction in IOP without glaucoma medication (complete success) or with no more than 2 medications (qualified success) and (2) similar to previous criterion with the exception of 16 mmHg being the IOP cut-off point. According to criterion 1, the surgery was classified as failure when IOP was <5 mmHg or more than 21 mmHg and according to criterion 2, when IOP was <5 mmHg or more than 16 mmHg in at least two consecutive visits 3 months after the surgery. Incidence of hypertensive phase (HP), BCVA, number of medications, and postoperative complications were analyzed as secondary outcome measures. In this study, HP was defined as IOP measurement >21 mmHg during the first 3 months after surgery not as a result of tube obstruction, retraction, or valve malfunction.

Surgical technique

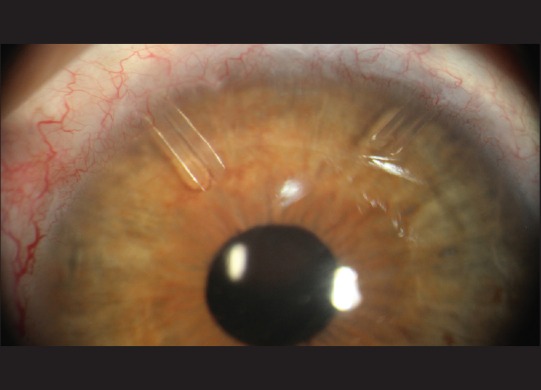

In all cases, the first AGV had been implanted in superotemporal quadrant. A single surgeon (Naveed Nilforushan) performed all second operations with a standard technique. A fornix-based conjunctival flap was fashioned in superonasal or inferotemporal quadrant, based on the availability of healthy conjunctiva and preference of the surgeon. Mitomycin C (0.2 mg/ml) was then applied by Weck-Cel sponges under the conjunctiva for 2 min. The AGV (model FP7, New World Medical, Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA) was primed, and its plate was secured to the sclera with 8-0 nylon suture, 10-11 mm behind the limbus. The tube was trimmed beveled up and then inserted into the anterior chamber. The anterior part of the tube was secured to the sclera using 10.0 nylon suture and was subsequently covered with donor scleral patch graft. Overlying conjunctiva was stitched with 10–0 polyglactin suture material in running fashion. Postoperatively, all patients were prescribed ciprofloxacin eye drops 4 times a day for approximately 2 weeks and betamethasone eye drops every 2 h for 2 weeks which was then tapered over the next 6–8 weeks. Patients were examined on the postoperative day 1, then at least weekly for 4 weeks, and then every 1–3 months, based on the clinical judgment. IOP lowering medications were initiated on discretion of the surgeon when the preset target pressure was not reached.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to determine the probability of surgical success based on two criteria. Snellen BCVA was converted to logarithm of minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 20 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). For analysis, data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Paired t-test and Wilcoxon test were used to compare baseline and outcome variables. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed t-test (P ≤ 0.05).

Results

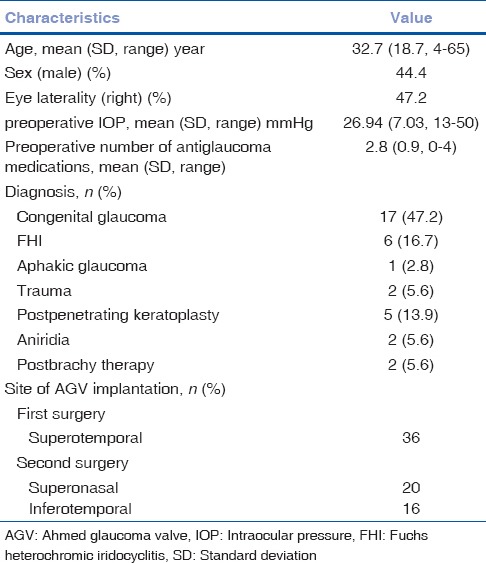

Thirty-six eyes of 34 patients (15 men) who had undergone the second AGV implantation in the same eye with follow-up of at least 6 months were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the patients was 32.7 years (SD 18.7, range 4–65), and the mean duration of follow-up was 21.4 months (SD 21.7, median 12, range 6–96). The time interval between the first and second AGV implantation was on average 4.05 years (range 1–10). Patient characteristics at the time of second valve surgery are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the time of second Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation

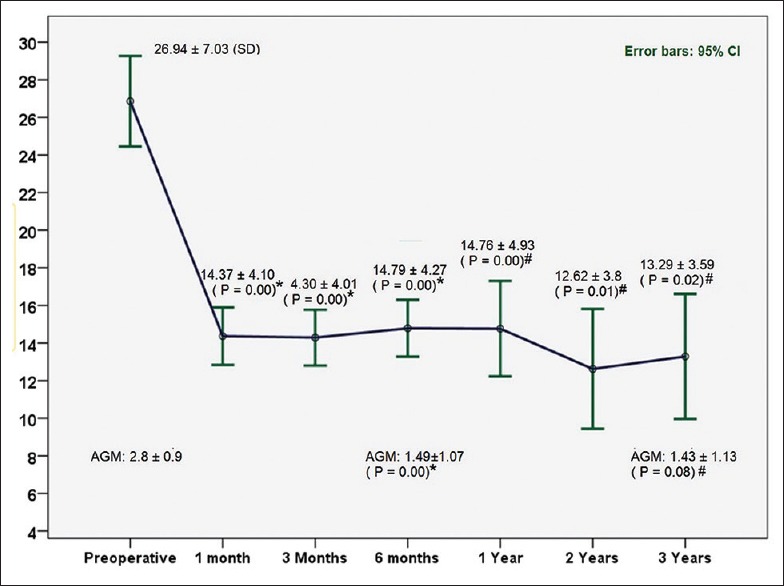

Preoperatively, the mean IOP was 26.94 mmHg (SD 7.03), and the patients were using 2.8 glaucoma medications on average (SD 0.9). The mean IOP and number of medications decreased significantly to 13.28 mmHg (SD 3.59) and 1.4 (SD 1.1) at the last postoperative visit, respectively (P = 0.00 in both).

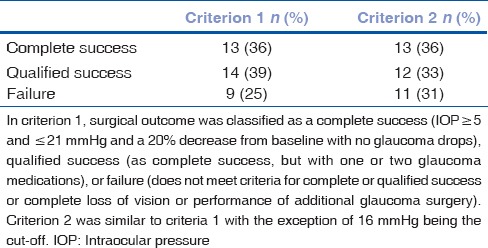

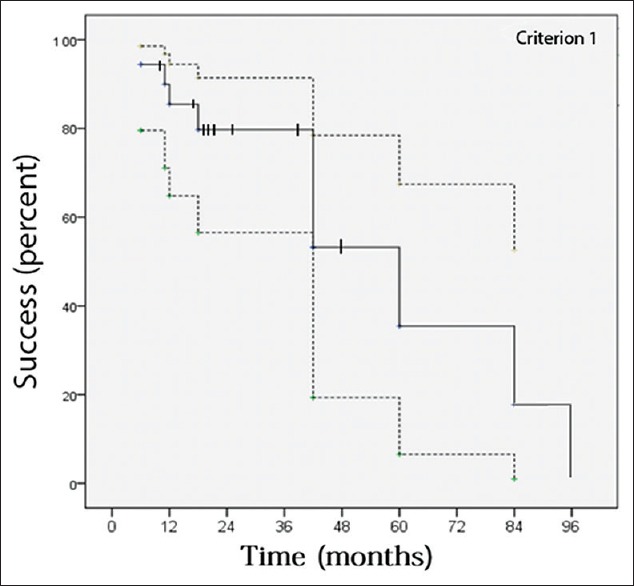

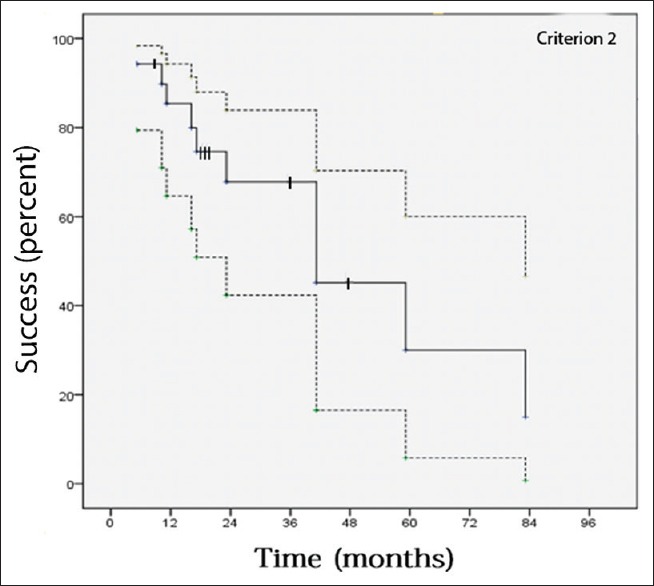

Fig. 1 illustrates IOP changes during the 3-year postoperative period. Tonometric failure detected at last follow-up was occurred in 9 (25%) and 11 (30%) eyes according to criteria 1 and 2, respectively [Table 2]. However, with regard to incomplete follow-up for many of the individuals in this study, Kaplan–Meier approach was utilized to estimate the cumulative incidence of surgical failure [Figs. 2 and 3]. According to criterion 1, 6, 12, 18, and 42 months success rate (95% confidence intervals) was 94% (87, 100), 85% (72, 99), 80% (63, 96), and 53% (21, 85), respectively. Median time to failure was 60 (26, 94) months. According to criterion 2, 6, 12, 18, and 42 months success (95% confidence intervals) was 94% (87, 100), 85% (72, 99), 75% (57, 93), and 45% (16, 75), respectively. Median time to failure was 42 (14, 70) months. Fig. 4 shows a case with the second AGV implantation 12 months after surgery.

Figure 1.

Intraocular pressure changes during the postoperative 3-year period. +P values on the basis of comparison with preoperative values using paired t-test, #P values on the basis of comparison with preoperative values using Wilcoxon test. AGM: The number of antiglaucoma medication; IOP: Intraocular pressure

Table 2.

Success at last follow-up based on criterion 1 and 2 (n=36)

Figure 2.

Success of the second Ahmad glaucoma valve in refractory glaucoma based on criterion 1. Success was calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, where the dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals and the hatch marks indicate censored subjects (eyes). The 6, 12, 18, and 42 months success (95% confidence intervals) was 94% (87, 100), 85% (72, 99), 80% (63, 96), and 53% (21, 85), respectively. Median time to failure was 60 (26, 94) months

Figure 3.

Success of second Ahmad glaucoma valve in refractory glaucoma based on criterion 2. Success was calculated using Kaplan–Meier life table analysis, where the dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals and the hatch marks indicate censored subjects (eyes). The 6, 12, 18, and 42 months success (95% confidence intervals) was 94% (87, 100), 85% (72, 99), 75% (57, 93), and 45% (16, 75), respectively. Median time to failure was 42 (14, 70) months

Figure 4.

The right eye of a patient with the second Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation in superonasal quadrant of the conjunctiva. The first Ahmed glaucoma valve was implanted in superotemporal quadrant

No significant intraoperative complication was determined and also, there was no case of endophthalmitis, or retinal detachment postoperatively. Further, one case of postoperative hyphema was managed medically. Conjunctival retraction led to surgical repair in another patient. In addition, three patients underwent needling of the encapsulated bleb around the plate (one with adjunctive mitomycin C) 3–10 weeks after surgery.

Preoperatively, BCVA (LogMAR) on average was 0.91. It did not change significantly 6 months postoperatively (0.94, P = 0.19) and at the last visit (0.93, P = 0.18).

HP was detected in 22 patients (61.11%) during the first 3 months of surgery for whom IOP-lowering medication was started. In 13 cases (59.09%), HP occurred within 1 month after surgery (4 of them in the first 2 weeks). Nine (24.99%) other patients needed medications for IOP control in weeks 4–10.

We also divided the patients to those with preoperative IOP ≤21 mmHg and preoperative IOP >21 mmHg for comparison. This showed that out of 30 eyes with preoperative IOP >21 mmHg, according to criteria 1 and 2, 7 (23%) and 9 (30%) eyes were failed, respectively. Moreover, out of 6 eyes with preoperative IOP ≤21, 2 (33%) eyes were failed according to both criteria. No significant difference was found between subgroups with preoperative IOP ≤21 and preoperative IOP >21 mmHg (P > 0.99, Fisher exact test).

Of 11 cases with failure according to criterion 2, in three cases, medical treatment was continued; in two cases, cyclophotocoagulation was performed; and in the rest, we did not have further follow-up records to report herein.

Discussion

Second Ahmed valve surgery was shown to be safe and effective in this study. Mean IOP at final exam was 13.28 mmHg, a reduction of 13.66 mm Hg or 50% from preoperative values even though patients were on fewer glaucoma medications. No major complication occurred and the mean best corrected visual acuity did not show a statistically significant reduction.

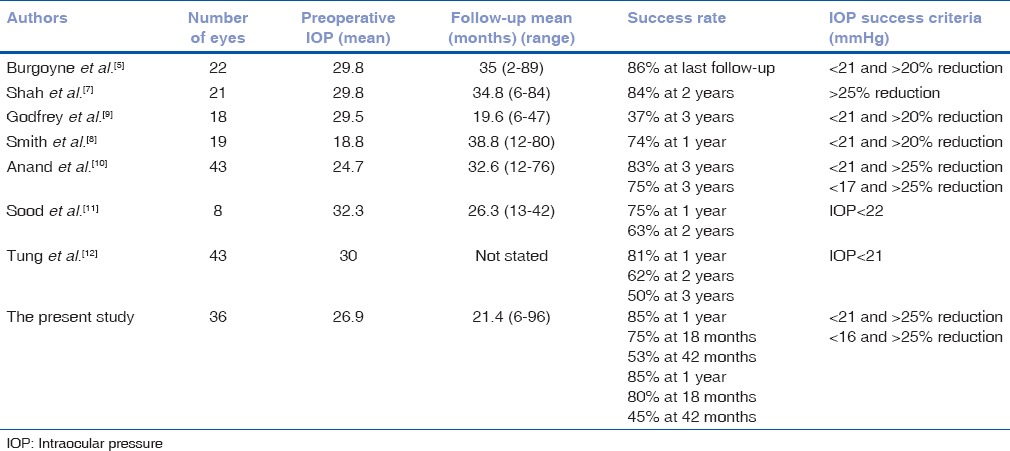

During the last decade, several studies have addressed the success rate of various secondary shunt implantation such as AGV, Molteno, Baerveldt, Krupin and schocket in adults,[5,8,9] and children[10,11] [Table 3] with reported success rates of 50-93%. But a comparison of the overall success rate in these case series is not literally feasible not only because of different mix of glaucoma types studied, various lengths of follow-up and different definitions of surgical success; but even more notably because these studies are all relatively small in sample size and consequently a relatively wide confidence interval straddles their point estimates of surgical success. Smith et al.[12] evaluated patients who had undergone 2 glaucoma drainage device surgeries (exclusively AGV) in a retrospective case series and found 84.2% overall success (comparable with success definition of our study according to criterion 1) in a follow-up of at least 1 year. The reported success rate was apparently more than that of the present study (75%). This difference may be accounted for by longer follow up in the present study (up to 96 months) in comparison with Smith's study (up to 80 months).

Table 3.

Surgical results of secondary shunt implantation in eyes with failed prior shunts

In our study age, gender, laterality of studied eyes, preoperative IOPs, preoperative number of medications and glaucoma type of individual patients did not differ significantly between success and failure groups of patients (results of t-test and Fisher's exact test not shown here). Smith et al.[12] in a retrospective study with 21 participants showed that patients with preoperative IOP ≥21 mm Hg benefited more from second AGV implantation than those with lower IOPs but in our study we did not found a significant difference in this regard.

HP in this study occurred in relatively similar rates as reported in the literature (59.4 % at first 3 month after surgery) that is close to the findings of Smith et al.[12] with the rate of 61%. Wu SC et al.[13] reported occurrence of HP in 63.2% of their patients, 49.3% of them experienced HP at 1 month and the rest at 2 months after the operation. Nouri-Mahdavi and Caprioli,[14] observed HP in 56% of their studied eyes. It occurred after a mean of 5.0 weeks (median, 4 weeks; range, 1-13 weeks).

Besides the retrospective and noncomparative design of this study and including nonuniform types of glaucoma, the other limitation of the present study is a relatively small sample of patients for analyzing the success rate after 3 years post-AGV re-implantation. Although the wide confidence interval for measured success rate after 3 years of the surgery makes it difficult to predict the long-term prognosis, a practical conclusion can be extracted from the present body of evidence, i.e., until a better option emerges, glaucoma specialists can offer secondary shunt implantation instead of cyclodestructive procedures to patients with failed primary shunts with a considerable hope of tonometric success with or without medications.

Conclusion

Repeated AGV implantation seems to be a safe modality of treatment with acceptable success rate in cases of failed previous AGV surgery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Rasool-e-Akram Clinical Research Development Center for English edition.

References

- 1.Stevens GA, White RA, Flaxman SR, Price H, Jonas JB, Keeffe J, et al. Global prevalence of vision impairment and blindness: Magnitude and temporal trends, 1990-2010. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai MA, Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, Shi W, Chen PP, Parrish RK., 2nd Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: A survey of the American Glaucoma Society in 2008. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42:202–8. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110224-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi AB, Parrish RK, 2nd, Feuer WF. 2002 survey of the American Glaucoma Society: Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery and antifibrotic use. J Glaucoma. 2005;14:172–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000151684.12033.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirwan JF, Shah P, Khaw PT. Diode laser cyclophotocoagulation: Role in the management of refractory pediatric glaucomas. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:316–23. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00898-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgoyne JK, WuDunn D, Lakhani V, Cantor LB. Outcomes of sequential tube shunts in complicated glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:309–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai JC, Grajewski AL, Parrish RK., 2nd Surgical revision of glaucoma shunt implants. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999;30:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah AA, WuDunn D, Cantor LB. Shunt revision versus additional tube shunt implantation after failed tube shunt surgery in refractory glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:455–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith M, Buys YM, Trope GE. Second Ahmed valve insertion in the same eye. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:336–40. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318182edfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godfrey DG, Krishna R, Greenfield DS, Budenz DL, Gedde SJ, Scott IU. Implantation of second glaucoma drainage devices after failure of primary devices. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002;33:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand A, Tello C, Sidoti PA, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Sequential glaucoma implants in refractory glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sood S, Beck AD. Cyclophotocoagulation versus sequential tube shunt as a secondary intervention following primary tube shunt failure in pediatric glaucoma. J AAPOS. 2009;13:379–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tung I, Marcus I, Thiamthat W, Freedman SF. Second glaucoma drainage devices in refractory pediatric glaucoma: Failure by fibrovascular ingrowth. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:113–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu SC, Huang SC, Lin KK. Clinical experience with the Ahmed glaucoma valve implant in complicated glaucoma. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26:904–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Caprioli J. Evaluation of the hypertensive phase after insertion of the Ahmed glaucoma valve. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:1001–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]