Abstract

We report the first case of intraocular gnathostomiasis from Central India. A 29-year-old male from Indore, Madhya Pradesh, presented with pain and redness of the right eye since 1 month. Slit lamp examination revealed anterior uveitis, multiple iris atrophic patches, and a live worm hooked on iris. The worm was removed through a small sclerocorneal tunnel. Microscopy confirmed Gnathostoma spinigerum. The patient was treated with oral albendazole and steroids. The case is reported because of its rarity.

Keywords: Ocular gnathostomiasis, sclerocorneal tunnel, uveitis

Intraocular gnathostomiasis is a rare parasitic infection caused by the third-stage larvae of spiruroid nematode Gnathostoma species seen mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. It is a food-borne zoonosis caused by ingestion of raw or undercooked freshwater fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, all of which are known to harbor advanced third-stage larvae of Gnathostoma species.[1] Gnathostoma spinigerum is the most common Gnathostoma species in Asia associated with a unique unilateral form of ocular larva migrans where an actively motile parasite can be seen more often in the anterior and less frequently in the posterior segment of the eye.[2] In India, most cases have been reported from eastern[3] and northeastern states,[4] 2 cases from southern coastal states,[1,5] and one case from western coastal states.[6] We report the first case of ocular gnathostomiasis in Central India.

Case Report

A 29-year-old male, driver by occupation, came with complaints of redness, pain, and diminution of vision in the right eye from 1 month. The patient had a mixed diet including fish and poultry. On general examination, there was no edema, pallor, organomegaly, or lymphadenopathy. There was no history of migratory skin eruptions.

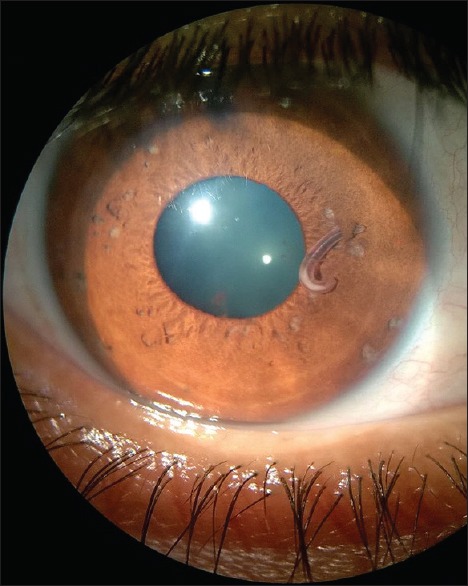

On examination, the visual acuity in the right eye was 6/9, and the visual acuity in the left eye was 6/6. On slit lamp examination, the left eye was normal. The right eye showed mild ciliary congestion and pigments on the endothelium and anterior lens capsule. The anterior chamber had 2+ cells and flare. The iris had multiple atrophic patches, 2 iris holes were present, and the pupil reacted normally. There was a live, motile worm hooked to the midperipheral iris [Fig. 1]. The fundus was normal. All routine investigations including hemogram and chest X-ray were normal. Routine urine and stool examination did not reveal any egg/worm/larva. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbit and ultrasonography B-scan of both eyes were normal.

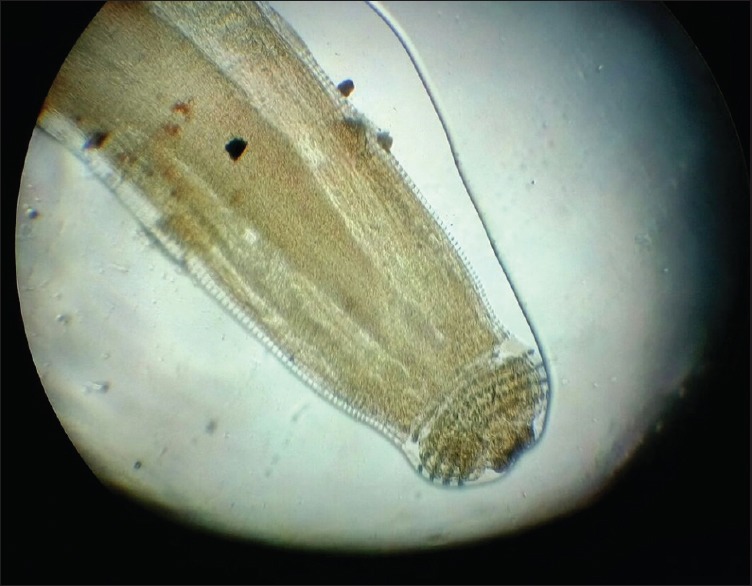

Figure 1.

Depicting live worm hooked to midperipheral iris

Under peribulbar anesthesia, a 3 mm sclerocorneal tunnel was made. The worm was extracted with plain forceps from the anterior chamber and was sent for microscopy to the Department of Microbiology and Parasitology. The worm was a short and stout reddish brown, cylindrical structure measuring approximately 1 cm in length. On the examination of wet mount, it showed bulbous head with four rows of hooklets; the anterior part of the worm is covered with rows of cuticular spines. Diagnosis of G. spinigerum was confirmed by microscopy [Figs. 2–5]. The patient was given oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 21 days and tapering dose of oral prednisolone (50 mg od for a week followed by tapering dose by 10 mg every week, 5 mg od for a week after the 5th week, and then stopped). Patient was followed up every month for 3 months. Patient recovered with no sequelae [Fig. 6].

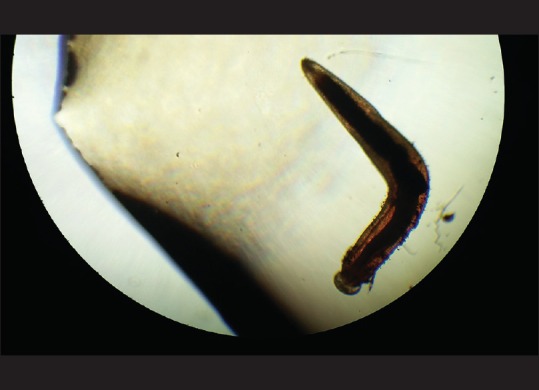

Figure 2.

Third-stage larva of Gnathostoma spinigerum

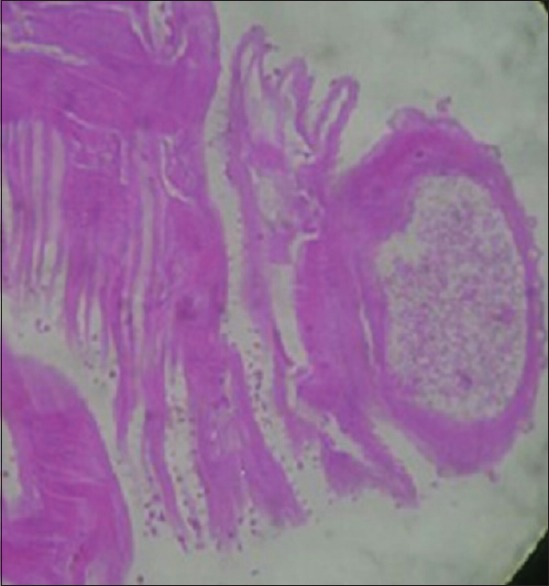

Figure 5.

H and E stained section

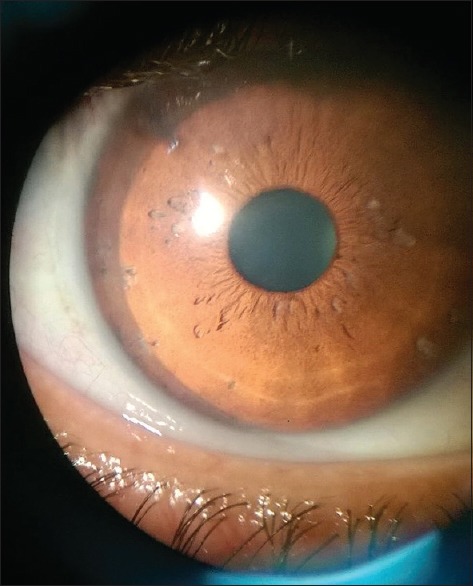

Figure 6.

Eye of the patient after removal of the gnathostostoma larva

Figure 3.

Cephalic bulb of Gnathostoma larva with rows of hooklets

Figure 4.

Body cavity of Gnathostoma spinigerum

Discussion

Of the 12 known species within the genus Gnathostoma, only 4 species have been known to infect humans namely Gnathostoma nipponicum, Gnathostoma hispidum, Gnathostoma doloresi, and G. spinigerum. G. spinigerum is found in wild and domestic cats and dogs in Southeast Asia, China, Japan, and India.[2] Humans become accidental host when they consume raw or undercooked meat of the definitive host or the second intermediate hosts such as brackish water fish, chicken, snails, and frogs or paratenic hosts such as birds.[7] Cutaneous lesions such as migratory panniculitis or serpiginous eruptions caused by the migration of the third-stage larvae are the most common manifestation of this infection, but their onset may be delayed for months and even years.[8] Migration to unexpected sites leads to visceral involvement of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, ear, central nervous system, and eye. Among the various forms of visceral gnathostomiasis, central nervous system infestation causes fatal eosinophilic myeloencephalitis whereas ocular involvement is rare.[9,10] The most common manifestation of intraocular gnathostomiasis is anterior uveitis and intraocular parasite because it mostly localizes itself in the anterior segment of the eye. The other common manifestations are eyelid edema, conjunctival chemosis, hyphema, retinochoroidal, vitreous hemorrhage, and rarely, central retinal artery occlusion leading to blindness. The portal of entry into the eye may be posterior retina because intraocular gnathostomiasis has been associated with macular scarring, rupture of nasal branch of central retinal artery, or retinal tear with choroidal hemorrhage near the optic disc.[1] Iris holes, uveitis, and subretinal hemorrhage with subretinal tract can be characteristic features of intraocular gnathostomiasis.[5]

Clinical symptoms of gnathostomiasis are due to the inflammatory reaction provoked by migrating larvae. Clinically, it may present as painful cutaneous larva migrans, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and central nervous system infections, with or without peripheral blood eosinophilia (eosinophil count >0.4 × 109/L), or undiagnosed eosinophilia with nonspecific symptoms.[11] Because of the avascularity of the anterior chamber of the eye, eosinophilia which is the hallmark of parasitic infections is evidently absent and usually mild if at all present.[8] Once the disease is diagnosed, management of gnathostomiasis is straightforward. Hence, eosinophilia cannot be considered a screening tool. However, Moore et al. have commented that it could be used as a marker of treatment response in those with eosinophilia at baseline.[12] In the present case, there was no cutaneous manifestation and no eosinophilia.

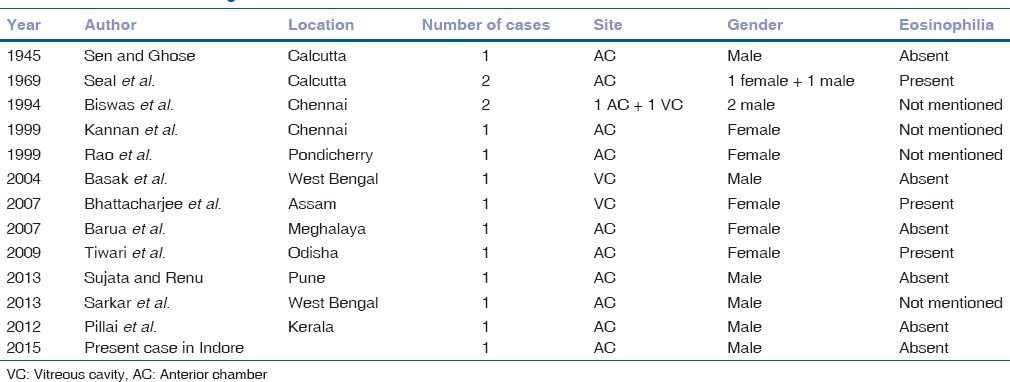

High-dose albendazole, given for 3 weeks, has been used as specific chemotherapy for treatment of patients with gnathostomiasis. Till now, 14[1,6] intraocular gnathostomiasis cases have been documented from India – 3 from Calcutta, 2 from West Bengal, 3 from Chennai, one each from Meghalaya, Assam, Odisha, Kerala, Pondicherry, and Maharashtra [Table 1]. With increasing reports of intraocular gnathostomiasis from India, the clinicians should be familiar with this disease; therefore, diagnosis is not missed or delayed, avoiding potentially serious complications.

Table 1.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to Dr. Sunil Ahirwar, Microbiologist, at Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Medical College, Maharaja Yashwantrao Hospital, Indore, for providing light microscopy and histopathological reports and helping in confirmation of diagnosis.

References

- 1.Pillai GS, Kumar A, Radhakrishnan N, Maniyelil J, Shafi T, Dinesh KR, et al. Intraocular gnathostomiasis: Report of a case and review of literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:620–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484–92. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basak SK, Sinha TK, Bhattacharya D, Hazra TK, Parikh S. Intravitreal live Gnathostoma spinigerum. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:57–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barua P, Hazarika NK, Barua N, Barua CK, Choudhury B. Gnathostomiasis of the anterior chamber. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:276–8. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.34775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas J, Gopal L, Sharma T, Badrinath SS. Intraocular Gnathostoma spinigerum. Clinicopathologic study of two cases with review of literature. Retina. 1994;14:438–44. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199414050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sujata DN, Renu BS. Intraocular gnathostomiasis from coastal part of Maharashtra. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:82–4. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daengsvang S. Gnathostomiasis in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1981;12:319–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: Case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33–50. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Punyagupta S, Bunnag T, Juttijudata P. Eosinophilic meningitis in Thailand. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 162 patients with myeloencephalitis probably caused by Gnathostoma spinigerum. J Neurol Sci. 1990;96:241–56. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90136-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boongird P, Phuapradit P, Siridej N, Chirachariyavej T, Chuahirun S, Vejjajiva A. Neurological manifestations of gnathostomiasis. J Neurol Sci. 1977;31:279–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(77)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, Chaicumpa W, Yentakam S. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore DA, McCroddan J, Dekumyoy P, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis: An emerging imported disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:647–50. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]