Abstract

The trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27Me3) contributes to gene repression, notably through recruitment of Polycomb complexes, and has long been considered essential to maintain cell identity. Whereas H3K27Me3 was thought to be stable and not catalytically reversible, the discovery of the Utx and Jmjd3 demethylases changed this notion, raising new questions on the role of these enzymes in gene expression and cell differentiation. Recent studies have demonstrated critical roles for Utx and Jmjd3 in the development and function of immune cells, and revealed both demethylase and demethylase-independent activities of these enzymes. I review these finding here, and discuss the current understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the broad, yet highly cell- and gene-specific, impact of these enzymes in vivo.

Introduction

Both sequence-specific transcription factors and chromatin organization, notably post-translational histone modifications, contribute to control gene expression [1]. The tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) has attracted much interest because it contributes to maintain multipotency in stem cells, and lineage identity in more differentiated cells, by repressing inappropriate gene expression. The demonstration, in 2007, that Utx and Jmjd3 molecules (Fig. 1) have catalytic demethylase activity on tri-methylated H3K27 (H3K27Me3)[2–7] has both challenged the view that H3K27 trimethylation is highly stable and not catalytically reversible [8], and raised the question of the function of these enzymes in vivo. Studies over the past few years, notably in immune cells in which H3K27Me3 is broadly distributed and has been associated with gene repression, have now shown that Jmjd3 and Utx are essential for cell differentiation and function. The picture that emerges from these analyses is that, despite the broad distribution of H3K27Me3 over the genome, the functions of Jmjd3 and Utx are highly gene- and cell type-specific. Furthermore, and quite unexpectedly, these studies have also highlighted that critical functions of Jmjd3 and Utx do not depend on their demethylase activities.

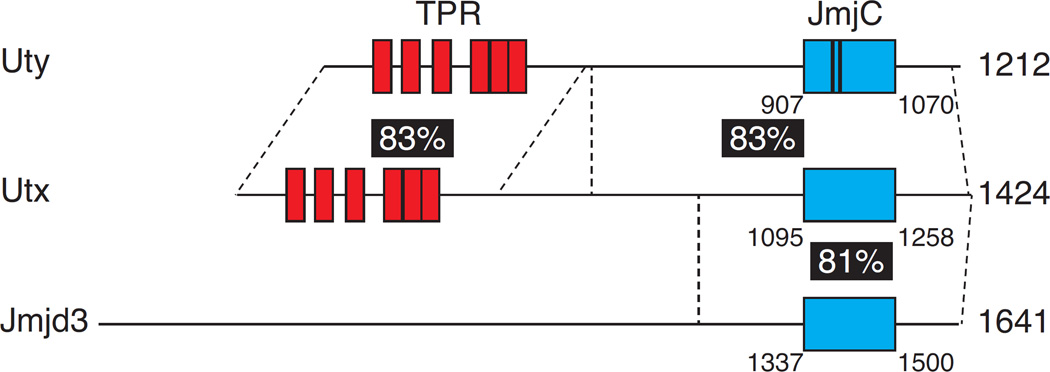

Figure 1. Schematic structure of Kdm6 family proteins.

Uty, Utx and Jmjd3 are schematically depicted with their JmjC domain shown as a blue box and Utx and Uty tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR) shown as red boxes. Amino-acid residue numbers are shown in black, whereas numbers in white over black background indicate percent aminoacid identity between the regions of the molecules delineated by dashed lines. Black bars in Uty JmjC domain indicate mutations at positions 947 and 955 responsible for the lack of catalytic activity [33].

H3 K27 methylation and demethylation

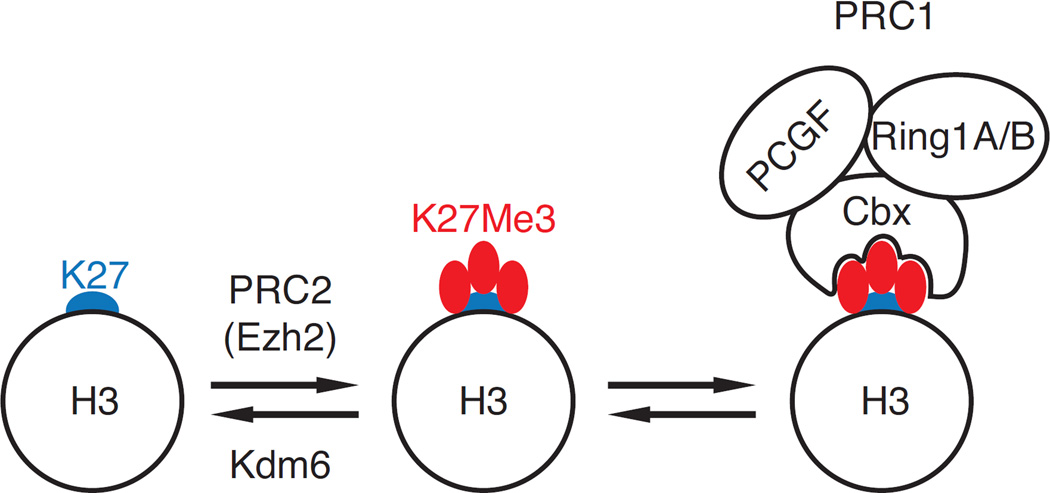

H3K27Me3 is widely distributed on the genome, and particularly abundant at and near promoters of silent genes [9–12]. The trimethylation of H3K27 is thought to promote gene repression through several mechanisms. The most intensively studied is the recruitment of a multiprotein assembly called Polycomb-repressive complex 1 (PRC1), of which specific components have gene silencing functions [13]. These include ubiquitination of histone H2A lysine 119 (H2AK119), chromatin compaction and direct interactions with the transcription initiation machinery. PRC1 complexes are recruited to H3K27Me3 through specific binding subunits, called Cbx proteins in mammals (Fig. 2, right). Despite its importance as a H3K27Me3 ligand, the relationships between PRC1 and H3K27Me3 is not univocal: subsets of PRC1 lacking Cbx subunits can be recruited to their target sites in an H3K27Me3-independent manner, notably through direct interactions with sequence-specific transcription factors [13–15]. Conversely, PRC1-independent functions have been proposed for H3K27Me3, including preventing K27 acetylation, a modification associated with active gene transcription, and inhibiting transcription elongation [16–18]. Furthermore, the relationships between the composition of PRC1 complexes, notably their inclusion of a H3K27Me3-binding Cbx subunit, and their function remain to be fully understood [13]. The methylation of H3 K27 is catalyzed by Polycomb-repressive complexes 2 (PRC2), which includes either of two catalytic methyl transferase subunits, Ezh1 or Ezh2 (Fig. 2, left) [12, 19]. Both Ezh2 and components of PRC1 have been shown to be critical at multiple stages of immune cell development and responses, highlighting the importance of H3K27 methylation for cell homeostasis and differentiation [20–27].

Figure 2. H3K27Me3 homeostasis.

H3 K27 (blue) is methylated by PRC2-associated methyl transferases (Ezh2, as shown, or Ezh1), resulting in mono-, di-, or trimethylation (H3K27Me3, shown, middle). Kdm6 family enzymes Jmjd3 and Utx can demethylate H3K27Me3 into its di- or monomethyl forms (not shown for simplicity). H3K27Me3 recruits PRC1 complexes through their Cbx subunits (Cbx4–8). Additional subunits common to most PRC1 complexes are depicted, including ubiquitin ligases Ring1A or 1B, and a member of the Polycomb group RING fingers (PCGF) family of proteins (e.g. Bmi1) [13, 15].

Jmjd3 and Utx demethylases, which we will refer collectively to as Kdm6 molecules, are part of a large family of enzymes defined by the presence of a JmjC catalytic domain [28–31] (Fig. 1). Catalytic lysine demethylation mediated by JmjC domains requires iron as a catalytic co-factor, as well as two additional substrates, oxygen and α-ketoglutarate. Both Jmjd3 and Utx catalyze the removal of one methyl group from tri- or di-methyl H3K27, leaving as an end product the mono-methyl form. Of note, the gene encoding Utx, Kdm6a, is located on chromosome X and, unlike most of the X chromosome, is expressed bi-allelically in female cells [32]. While male cells express a Y-chromosome encoded homolog of Utx, Uty, this protein has little if any H3K27Me3 demethylase activity in vitro, owing to a catalytic site mutation within its JmjC domain [2, 3, 33]. While Jmjd3 and Utx are very large molecules, they share little if any homology outside of their catalytic JmjC domain (Fig. 1). Such unique regions of the proteins may be involved in the recruitment to target sites or in demethylase-independent activities that have been assigned to each molecules (as discussed below).

Among potential histone substrates, Jmjd3 and Utx are highly specific for H3K27Me3, showing little if any demethylase activities on other methylated lysines in vitro [2–6, 34]. Structural studies on Utx have shown that substrate specificity is mediated both by the JmjC domain, recognizing methylated K27 and neighboring residues, and by a novel zinc-binding motif located downstream of the JmjC domain and recognizing residues 17–21 of H3 [35]. Several subclasses of JmjC demethylases have been defined based on sequence homology [28–31]. In contrast with the strict specificity of Jmjd3 and Utx, some members of other JmjC sub-families have a broader substrate range. However, they have little if any demethylase activity on H3K27Me3, with the possible exception of Kdm4 family members [36]. While the JmjC protein Jhdm1d (encoded by Kdm7) also demethylates H3K27Me2, and has been reported to associate with Jmjd3 [18], it has not been shown to act on its own on H3K27Me3.

In vivo analyses of Kdm6 functions

Pioneering analyses in immune cells, notably in T cells and macrophages, have been at the forefront of our understanding of the genome-wide dynamics of histone modifications, including H3K27Me3, during cell differentiation [9, 11, 37]. These studies, using deep sequencing of chromatin immunoprecipitates (ChIPseq), established the genome-wide association between H3K27Me3 accumulation and promoter activity and documented that cell differentiation is associated with removal of the mark from key lineage-genes. Such H3K27Me3 removal was observed in differentiating effector T cells [11], which are actively proliferating, but also in macrophages, after short term signaling by Toll-like receptors (TLR) [37–39]. Thus, it could have been predicted that removing Jmjd3 or Utx or both would have broad and drastic effects on cell differentiation and homeostasis. As we discuss below, the impact of these enzymes in a wide variety of experimental systems has proven much more specific.

Jmjd3 functions in macrophages

The spotlight initially focused on Jmjd3, notably because it is the only member of the JmjC family to be induced in response to TLR signaling in macrophages [4]. In line with the functions of PRC1 in gene silencing, this observation predicted that Jmjd3 disruption would strongly affect H3K27Me3 homeostasis and gene expression in TLR-activated macrophages. Strikingly, in vitro and in vivo experimental assessments [37, 40] found little support for this possibility. While chromatin immunoprecipitation found Jmjd3 bound to genes induced by LPS, these were decorated with H3K4Me3, an activation mark, rather than with H3K27Me3 [37]. In fact, Jmjd3 disruption only had modest effects on LPS-induced gene expression [37, 40], and, at the gene level, there was no correlation between this effect and the impact on gene expression and H3K27Me3 removal.

Accordingly, analyses in vivo found little if any effect of Jmjd3 disruption on the functions of classical (type 1, M1) macrophages, which are involved in responses to microbial infections [39, 40]. However, it affected the differentiation of type2 (M2) macrophages, notably involved in tissue remodeling. In addition, reconstitution studies of Jmjd3-deficient cells with retrovirus-encoded Jmjd3 variants showed that the effect of Jmjd3 on M2 macrophage differentiation required its catalytic activity, and that it involved Jmjd3-mediated removal of H3K27Me3 at the gene encoding IRF4, a transcription factor important for M2 macrophage differentiation [40]. Altogether, these studies suggested that Jmjd3 was important for gene expression, although its impact was more specific than suggested by its wide distribution on the genome. Consistent with this general perspective, germline disruption of Jmjd3 respected embryonic development until mid-gestation, and allowed the differentiation of most tissues and organs to proceed without major defect. However, the enzyme is necessary for the proper development of the brain ‘pacemaker’ controlling respiratory activity, so that Jmjd3-deficient mice die shortly after birth [40, 41].

Utx is needed for early embryonic development

It was possible that Utx, rather than Jmjd3, was the key functional H3K27Me3 demethylase that removed the mark prior to gene expression, or that there was a broad overlap between the set of genes at which Utx and Jmjd3 controlled H3K27Me3, so that the inactivation of both enzymes was necessary to reveal the footprint of H3K27Me3 demethylation on gene expression. Although the involvement of Utx in macrophage differentiation or signaling has not been reported, several groups found that Utx is needed for early embryonic development [33, 42–44]. Utx-deficient female embryos exhibit major defects in the formation of mesoderm-derived tissues at mid-gestation, and die at day 10–11, notably from impaired heart development. Furthermore, ChIPseq analyses in Utx-deficient ES cells found increased H3K27Me3 promoter decoration, including at the gene encoding Brachyury, a transcription factor critical for mesoderm formation [45].

There was, however, a catch: namely, these functions of Utx did not require its demethylase activity. A demethylase-dead version of Utx rescued the early development of Utx-deficient embryos [42], and the same was true of Uty in male Utx-deficient embryos [33, 42–44] (although these animals had reduced survival). While this could have been caused by functional overlap with Jmjd3, further studies showed that this was not the case: the development of male embryos deficient for Utx and Jmjd3, and therefore lacking all known H3K27Me3 demethylases, proceeded through late gestation, as that of embryos lacking Jmjd3 only [46]. Thus, the demethylase activity of Jmjd3 and Utx is dispensable for early embryonic development. Parallel experiments reached the conclusion that Jmjd3 and Utx are largely dispensable for retinoic acid-induced H3K27Me3 removal in ES cells (an in vitro model of neurectoderm differentiation) [46].

Two striking notions emerged from these studies, challenging the importance of the demethylase activity of Jmjd3 and Utx. First, both enzymes do more than H3K27Me3 demethylation, and such demethylase-independent activities are important for their functions. Second, in vivo H3K27Me3 removal, including at differentiation-induced genes [46], proceeds largely independently from Jmjd3 and Utx, suggesting that alternative mechanisms contribute to H3K27Me3 homeostasis. However, early embryonic development is characterized by intense cell proliferation, in which ‘dilution’ of the H3K27Me3 mark during cell division could mask the functions of Kdm6 molecules. On the other hand, it had been noted that, because of the slow kinetic properties of Kdm6 catalysis, the impact of their activity may be blunted in experiments assessing short term TLR signaling in macrophages [37].

Jmjd3 and Utx functions in T cell development

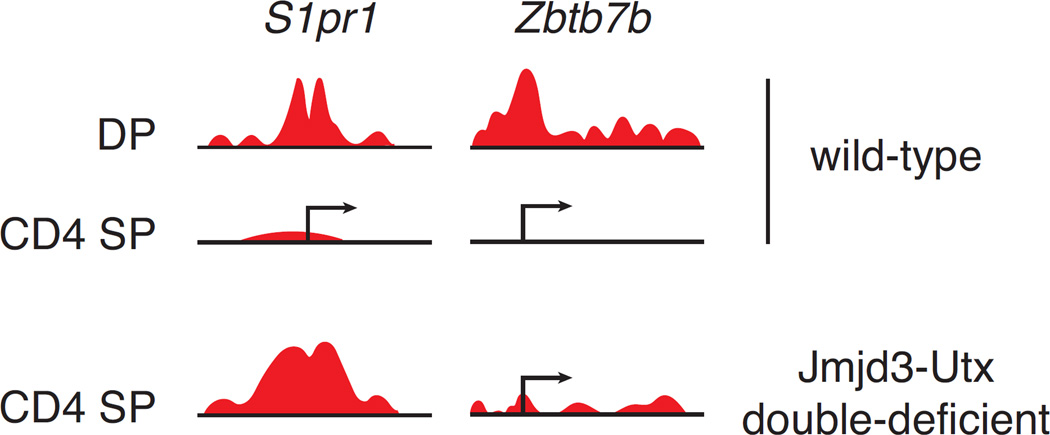

Assessing the function of Jmjd3 and Utx during T cell development offered an opportunity to overcome both limitations. Indeed, the development of CD4+CD8+ (double-positive, DP) into CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+ single positive (SP) thymocytes, is not associated with cell proliferation and spreads over several days in vivo [47–49]. Furthermore, ChIPseq experiments showed that this process is characterized by broad changes in H3K27Me3 decoration at genes crucial for the differentiation of CD4 SP thymocytes: out of approximately 8000 H3K27Me3-decorated promoters identified in DP thymocytes, a few hundred undergo removal of the mark during the development of DP into CD4 SP thymocytes [50]. These include (Fig. 3) (i) Zbtb7b, the gene encoding the transcription factor Thpok needed for CD4+ T cell differentiation [51], (ii) S1pr1, a sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor required for thymic egress [52], and (iii) Klf2, encoding a transcription factor needed for terminal thymocyte maturation, including S1pr1 expression [53]. Of note, H3K27Me3 removal at Zbtb7b and S1pr1 is associated with increased H3K4Me3 decoration [54, 55], suggesting that it was not simply caused by nucleosome repositioning outside of the promoter area.

Figure 3. Promoter-specific impact of Jmjd3 and Utx on H3K27Me3 demethylation in developing thymocytes.

H3K27Me3 decoration at the promoter regions of S1pr1 and Zbtb7b (encoding the transcription factor Thpok) are schematically depicted in wild-type CD4+CD8+ (DP) and CD4+CD8− (CD4 SP) thymocytes, and in CD4 SP thymocytes with disrupted Jmjd3 and Utx (original data from Ref. [50]). Normally, both promoters undergo almost complete H3K27Me3 removal as non-dividing DP thymocytes differentiate into CD4 SP cells, and are active in CD4 SP but not DP thymocytes. The overlapping activities of Jmjd3 and Utx are required for H3K27Me3 removal at and expression of S1pr1 in CD4 SP thymocytes. In contrast, Jmjd3 and Utx have little impact on H3K27Me3 removal at and expression of Zbtb7b.

Analyses of the differentiation of DP thymocytes lacking both Jmjd3 and Utx, obtained by Cd4-Cre mediated deletion of conditional alleles, showed increased numbers of mature CD4 and CD8 SP thymocytes, contrasting with reduced numbers of peripheral T cells. This effect was cell intrinsic, as shown by bone-marrow chimera experiments. The block, at the late CD4 SP stage, was complete in mice carrying a monoclonal TCR specificity, and gene expression analyses and reconstitution experiments assigned it to a complete failure to express S1pr1, the sphingosine receptor required for thymic egress [50]. Disruption of either Jmjd3 or Utx caused a less pronounced phenotype, suggesting substantial overlap between the activities of both enzymes in differentiating CD4+ T cells.

Even in such non-dividing cells, the impact of the double disruption on H3K27Me3 decoration was limited to a small fraction (less than 1%) of promoters [50], and there was no detectable genome-wide increase in H3K27Me3 deposition at promoters not normally harboring this mark. Rather, the double disruption preferentially targeted promoters that normally erase the mark during the DP to the CD4 SP transition, including S1pr1 (Fig. 3). This indicated a role of Jmjd3 and Utx in the dynamics of differentiation-induced H3K27Me3 removal, rather than in its steady-state homeostasis. Significant expression changes were detected at fewer than 1% of protein-coding genes [50]. At most of these, gene expression was reduced in Kdm6-deficient cells, and this was associated with increased H3K27Me3 promoter decoration, supporting the idea that the demethylase activity of these enzymes is directly involved in their promoting gene expression. Further supporting this notion, Uty, which lacks demethylase activity, failed to rescue expression of S1pr1 in male thymocytes lacking Jmjd3 and Utx.

In summary, these studies in non-dividing thymocytes demonstrated that Kdm6 molecules are essential for proper T cell development, shifting the pendulum back towards the idea that catalytic removal of H3K27Me3 is important for proper gene expression and cell differentiation, although probably not for steady state chromatin homeostasis. Of note, there is evidence that Jmjd3 and Utx have other functions in T cell development, although not at the DP to SP transition, as PRC2 activity has been shown to inhibit expression of Zbtb16, encoding PLZF, a transcription factor needed for the differentiation of iNK T cells [27]. Indeed, Kdm6 molecules are needed for proper iNK T cell differentiation [27, 56].

Opposing activities of Jmjd3 and Utx and cancer

While studies of late thymocyte development suggest a substantial functional overlap between the two enzymes, despite their lack of homology outside of the JmjC domain, analyses of their involvement in tumorogenesis, especially leukemogenesis, indicate that they may also have antagonistic functions. Early analyses found loss of function mutations of the gene encoding Utx (Kdm6a) in a variety of solid tumors and leukemias, highlighting its potential as a tumor suppressor gene [57]. That is indeed the case in acute T cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) [58, 59], in which Utx mutations are found in a subset of human cases. In contrast, Jmjd3 promotes leukemogenesis and is necessary for the development of T-ALL induced by an active version of the Notch1 receptor, a key signaling molecule in T cell development which is constitutively activated in a large fraction of human T-ALL cases [58, 60–62]. Upon activation, the intra-cellular form of Notch1 translocates to the nucleus where it serves as an activator of gene expression. Remarkably, mechanistic studies found that Jmjd3 associates with Notch1 [58]. Of note, the oncogenic role of Jmjd3 as an effector of Notch1-induced gene expression mirrors the effects of PRC2 components Ezh2 and Suz12, which repress expression of Notch1 targets and serve as tumor suppressor in T-ALL [24, 63].

Mechanistic insights

Impact on H3K27Me3 removal

The last few years have substantially changed our views of H3K27Me3 dynamics in cell differentiation, going from the original perspective that H3K27 methylation was not catalytically reversible, through the opposite possibility that Kdm6 demethylases were essential to its removal, and now to a better definition of their functions.

One key emerging notion is that Jmjd3 and Utx are important for H3K27Me3 dynamics, but not for its steady-state homeostasis. Even though transient overexpression of Jmjd3 reduces total intra-cellular H3K27Me3 levels [3, 33], in vivo studies of Utx-deficient cells did not report elevated H3K27Me3 cell contents [42, 43]. If confirmed in cells lacking both enzymes, such limited impact of Jmjd3 and Utx on genome-wide H3K27Me3 homeostasis would suggest that H3K27 methylation is the key rate-limiting step in the propagation of the mark, presumably by being tightly controlled by restricting access of PRC2 to specific genome areas. Consistent with this possibility, shRNA ‘knock-down’ of Suz12, a non-redundant component of PRC2 complexes [12], reduces the total amount of H3K27Me3 in CD4+ T cells [25].

Such locus-specific effects of Jmjd3 and Utx contrast with the broad distribution of H3K27Me3, suggesting that other mechanisms contribute to demethylate, or eliminate, H3K27Me3. Consistent with this idea, even in non-dividing thymocytes, a subset of developmentally induced promoters required neither Jmjd3 nor Utx to clear H3K27Me3 during cell differentiation. The most obvious such example is Zbtb7b [50, 55] (Fig. 3), encoding the transcription factor Thpok required for CD4+ T cell differentiation [51], thereby explaining that Kdm6 molecules are dispensable for Thpok expression and CD4+ T lineage differentiation [50].

Which additional mechanisms contribute to H3K27Me3 removal remains unclear. It was recently reported that additional JmjC-family demethylases, including members of the Kdm4 family, exhibit H3K27Me3 demethylase activity [36], and future studies will examine their impact of H3K27Me3 in vivo. Of note, such functional redundancy would be gene specific, as H3K27Me3 removal at specific promoters (e.g. S1pr1) is highly dependent on Jmjd3 and Utx in thymocytes [50]. Although possible, the involvement of non-JmjC enzyme is currently speculative. The only known such molecules, Kdm1-family demethylases, remove methyl residues from mono- and di-methyl lysines (although not H3 K27), but they have no activity on trimethylated residues [30].

Alternative mechanisms could involve nucleosome removal or replacement. One interesting possibility involves variant H3.3 molecules, which are deposited at genes and promoters through transcription-associated histone replacement [64–66]. By replacing K27-methylated histone H3 by un-methylated variant molecules, such mechanisms could erase the H3K27Me3 mark independently of any demethylase activity. Future studies will shed light on the mechanism of this histone replacement and the intra-cellular signals that trigger it.

H3K27Me3 demethylation and gene expression

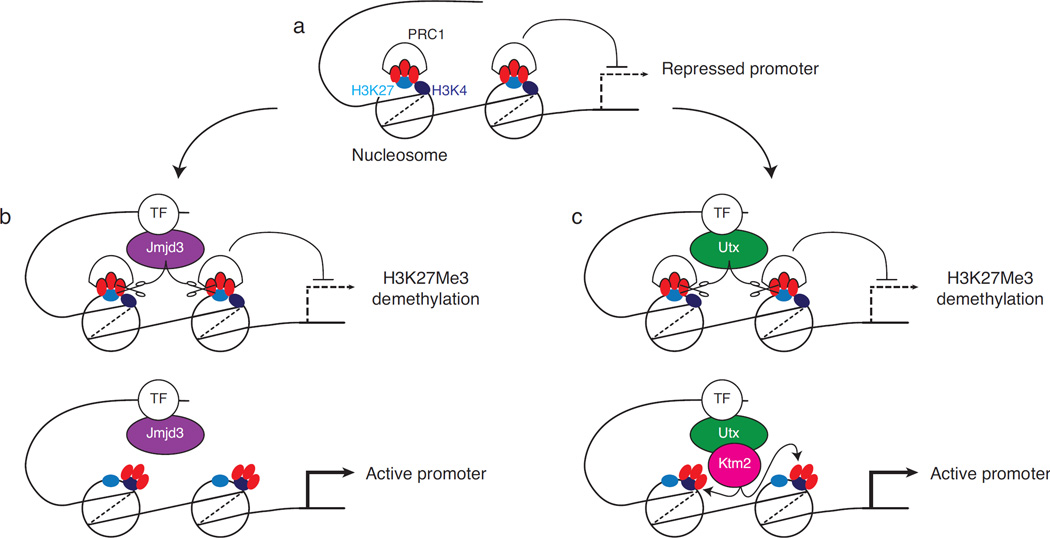

Recent studies have firmly established that catalytic demethylation mediates in part the activity of Jmjd3 and Utx on gene expression, including for Jmjd3 in late embryonic and M2 macrophage differentiation [40, 41], for Utx in somatic cell reprogramming [67], and our own observations in thymocytes [50]. This idea is in line with mounting evidence, from studies in Drosophila [68, 69] and in human tumors [66], that H3K27Me3 methylation has a causative effect on transcriptional repression (rather than simply being a marker). Indeed, directed or tumor-associated replacement of H3K27 by another residue (Arginine or Methionine) phenocopies the anti-silencing effects of PRC2 mutations, with the methionine substitution exerting a dominant effect by inhibiting PRC2 activity [70]. Thus, the past few years have established H3K27Me3 as a causative mechanism of gene repression, and the demethylase activity of Kdm6 proteins as essential for the induction of specific genes during cell differentiation (illustrated in Fig. 4a, b).

Figure 4. Demethylase-dependent and –independent effects of Jmjd3 and Utx on transcription.

The figure illustrates two potential mechanistic contributions of Jmjd3 or Utx to transcriptional activation. (a) schematic depiction of a gene promoter region, represented in an inactive state with extensive H3K27 (light blue ovals) trimethylation (red symbols) on nucleosomes. H3K4 (dark blue ovals) is not methylated. H3K27Me3-recruited PRC1 inhibits transcription. (b) Transcription factor (TF) mediated recruitment of Jmjd3 causes catalytic H3K27Me3 demethylation and relieves PRC1-mediated transcriptional repression (top). Jmjd3-independent mechanisms (not shown, e.g. transcription factor recruitment) result in transcription activation, associated with H3K4 trimethylation (bottom). In (c), a transcription factor recruits Utx, which promotes catalytic H3K27Me3 demethylation, thereby relieving PRC1-mediated repression (top), and associates with a Ktm2-family H3K4 methyl-transferase, resulting in H3K4 trimethylation (bottom). Note that (i) both Jmjd3 and Utx have been shown to associate with Ktm2 complexes, (ii) whether Jmjd3 or Utx molecules associated with MLL complexes exert demethylase activity (as depicted in [c]) remains to be determined, and (iii) the existence of promoters enriched in both H3K4Me3 and H3K27Me3 suggests that H3K4 trimethylation can take place before H3K27Me3 demethylation.

H3K27Me3-independent effects on gene expression

However, the evidence for demethylase-independent activities of Kdm6 molecules, notably in early embryonic differentiation, is equally solid. Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for such functions. The first relies on their association with KTM2 complexes (for histone lysine methyltransferase, also called MLL, for Mixed Lineage Leukemia), large multiprotein assemblies recruited at the promoter of active genes [71]. The defining component of these complexes are histone H3 Lysine 4 (H3K4) methyl transferases, that generate H3K4Me1, which identifies enhancers, and H3K4Me3, a hallmark of active promoters. Utx associates with Ktm2c and Ktm2d (also called Mll3 and Mll4 in mice) [72, 73], whereas Jmjd3 has been reported to interact with Ktm2b (also called Mll2 in mice and MLL4 in humans) and possibly other members of the family [4, 58, 74]. The actual functions of Utx or Jmjd3 in KTM2 complexes remains to be determined: they could serve as scaffold proteins, allowing assembly of the complex, allow recruitment of other transcriptional activators or of course endow the complex with H3K27Me3 demethylase functions in addition to its H3K4 methyl-transferase activity (illustrated in Fig. 4a, c).

In addition, there is evidence that both Jmjd3 and Utx interact with chromatin remodeling complexes [75], which move, in an energy-dependent manner, nucleosomes along the DNA double helix (Fig. 5) [76, 77]. In mammalian cells, a fraction of chromatin-remodeling complexes is centered over Brg1, a large protein with ATPase and DNA helicase activity. Both Jmjd3 and Utx have been shown to interact with Brg1 and other members of chromatin remodeling complexes [75]. This association involves a 213-residue long region of Jmjd3, which includes its JmjC domain, but it does not require intact Jmjd3 demethylase activity [75]. Brg1-containing chromatin remodeling complexes can have opposite impacts on transcription, and their effect is gene-specific [78]. The association of Jmjd3 with Brg1 has been reported to be important for the function of T-bet, a transcription factor essential for the differentiation of Th1 effector CD4+ T cells [79], and for their expression of the prototypical Th1 cytokine IFNγ [75]; similar Jmjd3-Brg1 interactions contribute to the function of Eomesodermin, a T-bet homolog expressed in CD8+ T cells [75, 80]. Accordingly, Jmjd3 disruption was recently found to impair Th1, but not Th2 or Th17, differentiation [81], partially mirroring the opposite effects of PRC2 inactivation [22]. Future studies, including in vivo mutagenesis, will be needed to identify the amino-acid residues involved in Jmjd3-Brg1 interactions and help delineate the contribution of such interactions to gene expression in vivo.

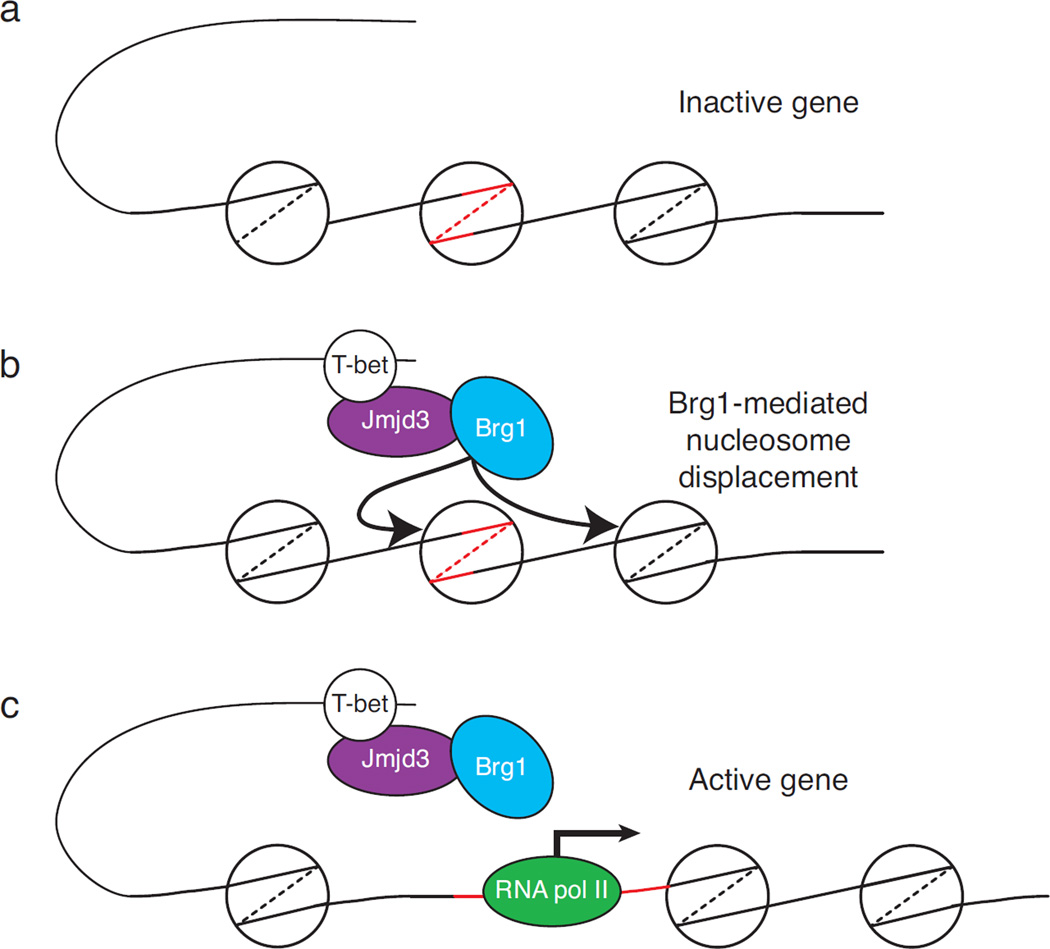

Figure 5. Potential impact of Jmjd3 and Utx on Brg1-mediated chromatin remodeling.

(a) Schematic depiction of a transcriptionally inactive gene promoter, in which DNA sequences around the transcription start site (red lines) are wrapped around a nucleosome, preventing RNA the recruitment of a transcription initiation complex. (b) DNA-bound T bet recruits a Jmjd3-Brg1 complex. The chromatin remodeling activity associated with Brg1 mobilizes nucleosomes away from the transcription start site (b), allowing RNA polymerase II recruitment and transcription initiation (c).

Whether demethylase-dependent and independent activities, and which among the latter, combine at a single gene promoter and are exerted by the same multi-molecular complexes, are still unanswered questions. Studies of S1pr1 gene expression support the possibility that these activities can be synergistic at a given promoter. Indeed, S1pr1 expression in mature thymocytes depends both on Utx demethylase activity [50] and on the adaptor Ptip1 [54], which is part with Utx of Ktm2c and Ktm2d complexes [72]. Such combinatorial impacts on H3K27Me3 removal and gene expression are likely to account for the pleiotropic effects of Jmjd3 disruption in Th1 effector T cell differentiation [81], or of Utx during follicular helper T cell differentiation [82] and hematopoiesis [83]. Delineating the respective impact of these multiple activities will be an important challenge for the field.

Of note, non histone substrates have been reported for Ezh2 [21] and may account in part for the pleiotropic effects of Ezh2 disruption in T cells [20–27]. It is therefore tempting to speculate that Jmjd3 and Utx have demethylase activity on the methylated version of these proteins.

DNA target recruitment

Current ChIPseq data suggests that Jmjd3 and Utx are bound to thousand of sites in the genome [18, 37, 58]. How they are recruited to such target sites, and which additional factors promote their activity once recruited are currently unsolved questions. One recruitment mechanism involves Jmjd3 or Utx association with sequence-specific transcription factors. Studies in early blastocyst cells have shown that Jmjd3 binds the transcription factor Smad3, a key intermediate in signaling by TGFβ-family molecules [84]. In effector T cells, both enzymes associate with the transcription factor T-bet [75]. T-bet binds the complex formed by Jmjd3 and Brg1, suggesting that T bet-mediated recruitment would promote chromatin remodeling; of note, T-bet is not needed for Jmjd3-Brg1 complex formation, raising the possibility that this complex can be recruited to promoters by unrelated transcription factors.

These findings do not exclude alternative recruitment mechanisms, notably through Utx or Jmjd3 association with Ktm2 complexes, which comprise subunits able to interact with sequence-specific transcription factors and therefore to target them to specific genomic sites [71]. Because Ktm2 complexes have H3K4 methyl-transferase activity, the preferential association of Jmjd3 with H3K4Me3-rich promoters in macrophages [37] highlights the potential importance of Ktm2 binding for Kdm6 promoter recruitment. In addition, long non-coding RNAs have been shown to recruit polycomb complexes to DNA, and to be involved in gene silencing (notably in Chromosome X inactivation) [85]. Whether similar mechanisms would recruit Jmjd3 or Utx to DNA remains to be determined.

Concluding remarks

While we are only at the dawn of our studies of H3K27Me3 homeostasis, much progress has been made in our understanding of Jmjd3 and Utx functions since these enzymes were identified, in 2007, as H3K27Me3 demethylases. Studies over the past few years have led to the emergence of three key concepts. First, the functions of Jmjd3 and Utx are highly gene-specific, suggesting that other mechanisms contribute to H3K27Me3 homeostasis. Second, the demethylase activity of these enzymes, which counteracts Polycomb-mediated gene repression, underpins some of their key functions. Third, and by contrast, demethylase-independent activities of Jmjd3 and Utx, that remain to be fully investigated but include association with other chromatin-modifying complexes, are also critical to their functions in vivo.

Challenges for future years abound. From the immunologist’s perspective, one key question is whether these enzymes contribute to establish or perpetuate epigenetic changes involved in immunological memory, whether in T cells or innate immune cells. However, deciphering their function in immunological memory is likely to require a better understanding of their diverse biochemical activities. Together with analyses of protein-protein interactions, this will involve in vivo mutagenesis studies, notably using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Defining the degree of functional overlap or antagonism will similarly be a critical task, especially in the light of data suggesting opposite impacts of Jmjd3 and Utx on tumor development, and suggesting an anti-tumor potential for inhibitors of Jmjd3 demethylase activity.

Another important objective will be to better understand the impact on Kdm6-catalytic activity of the two additional reactions substrates, oxygen and a-ketoglutarate, the latter a compound at the cross-roads of glucose and glutamine metabolism. This is of particular relevance to immune cells and cancer, as it is possible that oxygen and nutrient levels typically found at sites of tissue immune responses (or in the thymus) and in the cancer microenvironment are limiting for the catalytic reaction. Metabolic control of Jmjd3 and Utx activity, which presumably would affect their demethylase-dependent but not -independent activities, could be a critical, although not yet fully appreciated, control of the function of these proteins.

Trends box.

H3K27Me3 demethylases Jmjd3 and Utx are essential for a variety of cell differentiation processes, notably during hematopoietic cell development and during intra-thymic T cell development.

Jmjd3 and Utx are important for the dynamic removal of H3K27Me3 associated with cell differentiation, rather than for its steady-state homeostasis.

Jmjd3 and Utx-independent mechanisms, possibly demethylase-independent, contribute to H3K27Me3 homeostasis.

In addition to their H3K27Me3 demethylase activities, Jmjd3 and Utx display demethylase-independent activities, which are also essential to their functions, including in early embryonic development and effector T cell differentiation.

Outstanding questions.

How can the functions of demethylase-dead Jmjd3 and Utx in immune cells be assessed? This is essential to understand the impact of demethylase inhibitors.

What domains in Jmjd3 and Utx are necessary for interaction with Ktm2 complexes? Determining these domains through biochemical analyses will be important prior to studying the role of such interactions in vivo.

What are the functions of Jmjd3 and Utx in immunological memory? How does demethylation of specific loci contribute to differentiation into the memory compartment?

Determining the impact of histone replacement on Jmjd3- and Utx- independent H3K27Me3 removal, notably in non-dividing thymocytes.

Acknowledgments

I thank C. Bauge, J. Kim, S. Manna and P. Love for discussions, and T. Ciucci and M. Vacchio for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the author’s laboratory is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lan F, et al. A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature. 2007;449:689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature06192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong S, et al. Identification of JmjC domain-containing UTX and JMJD3 as histone H3 lysine 27 demethylases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18439–18444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Santa F, et al. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130:1083–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agger K, et al. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MG, et al. Demethylation of H3K27 regulates polycomb recruitment and H2A ubiquitination. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2007;318:447–450. doi: 10.1126/science.1149042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y. Histone lysine demethylases: emerging roles in development, physiology and disease. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2007;8:829–833. doi: 10.1038/nrg2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trojer P, Reinberg D. Histone lysine demethylases and their impact on epigenetics. Cell. 2006;125:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon JA, Kingston RE. Occupying chromatin: Polycomb mechanisms for getting to genomic targets, stopping transcriptional traffic, and staying put. Molecular cell. 2013;49:808–824. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu M, et al. Direct recruitment of polycomb repressive complex 1 to chromatin by core binding transcription factors. Molecular cell. 2012;45:330–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Z, et al. PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes. Molecular cell. 2012;45:344–356. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stock JK, et al. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nature cell biology. 2007;9:1428–1435. doi: 10.1038/ncb1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanhere A, et al. Short RNAs are transcribed from repressed polycomb target genes and interact with polycomb repressive complex-2. Molecular cell. 2010;38:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S, et al. The histone H3 Lys 27 demethylase JMJD3 regulates gene expression by impacting transcriptional elongation. Genes & development. 2012;26:1364–1375. doi: 10.1101/gad.186056.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margueron R, et al. Ezh1 and Ezh2 maintain repressive chromatin through different mechanisms. Molecular cell. 2008;32:503–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su IH, et al. Ezh2 controls B cell development through histone H3 methylation and Igh rearrangement. Nature immunology. 2003;4:124–131. doi: 10.1038/ni876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su IH, et al. Polycomb group protein ezh2 controls actin polymerization and cell signaling. Cell. 2005;121:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tumes DJ, et al. The polycomb protein Ezh2 regulates differentiation and plasticity of CD4(+) T helper type 1 and type 2 cells. Immunity. 2013;39:819–832. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyazaki M, et al. Thymocyte proliferation induced by pre-T cell receptor signaling is maintained through polycomb gene product Bmi-1-mediated Cdkn2a repression. Immunity. 2008;28:231–245. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hock H. A complex Polycomb issue: the two faces of EZH2 in cancer. Genes & development. 2012;26:751–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.191163.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. The polycomb repressive complex 2 governs life and death of peripheral T cells. Blood. 2014;124:737–749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang XP, et al. EZH2 is crucial for both differentiation of regulatory T cells and T effector cell expansion. Scientific reports. 2015;5:10643. doi: 10.1038/srep10643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobenecker MW, et al. Coupling of T cell receptor specificity to natural killer T cell development by bivalent histone H3 methylation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2015;212:297–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosammaparast N, Shi Y. Reversal of histone methylation: biochemical and molecular mechanisms of histone demethylases. Annual review of biochemistry. 2010;79:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kooistra SM, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:297–311. doi: 10.1038/nrm3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen MT, Helin K. Histone demethylases in development and disease. Trends in cell biology. 2010;20:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Rizzo PA, Trievel RC. Molecular basis for substrate recognition by lysine methyltransferases and demethylases. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1839:1404–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenfield A, et al. The UTX gene escapes X inactivation in mice and humans. Human molecular genetics. 1998;7:737–742. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shpargel KB, et al. UTX and UTY demonstrate histone demethylase-independent function in mouse embryonic development. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith ER, et al. Drosophila UTX is a histone H3 Lys27 demethylase that colocalizes with the elongating form of RNA polymerase II. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:1041–1046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01504-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sengoku T, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for histone H3 Lys 27 demethylation by UTX/KDM6A. Genes & development. 2011;25:2266–2277. doi: 10.1101/gad.172296.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams ST, et al. Studies on the catalytic domains of multiple JmjC oxygenases using peptide substrates. Epigenetics. 2014;9:1596–1603. doi: 10.4161/15592294.2014.983381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Santa F, et al. Jmjd3 contributes to the control of gene expression in LPS-activated macrophages. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:3341–3352. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2009;9:692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wynn TA, et al. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satoh T, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nature immunology. 2010;11:936–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgold T, et al. The H3K27 demethylase JMJD3 is required for maintenance of the embryonic respiratory neuronal network, neonatal breathing, and survival. Cell reports. 2012;2:1244–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C, et al. UTX regulates mesoderm differentiation of embryonic stem cells independent of H3K27 demethylase activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204166109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welstead GG, et al. X-linked H3K27me3 demethylase Utx is required for embryonic development in a sex-specific manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:13004–13009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210787109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morales Torres C, et al. Utx is required for proper induction of ectoderm and mesoderm during differentiation of embryonic stem cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e60020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wardle FC, Papaioannou VE. Teasing out T-box targets in early mesoderm. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2008;18:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shpargel KB, et al. KDM6 demethylase independent loss of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation during early embryonic development. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huesmann M, et al. Kinetics and efficacy of positive selection in the thymus of normal and T cell receptor transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;66:533–540. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCaughtry TM, et al. Thymic emigration revisited. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:2513–2520. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carpenter AC, Bosselut R. Decision checkpoints in the thymus. Nature immunology. 2010;11:666–673. doi: 10.1038/ni.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manna S, et al. Histone H3 Lysine 27 demethylases Jmjd3 and Utx are required for T-cell differentiation. Nature communications. 2015;6:8152. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Bosselut R. CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation: Thpok-ing into the nucleus. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2009;183:2903–2910. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annual review of immunology. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Callen E, et al. The DNA damage- and transcription-associated protein paxip1 controls thymocyte development and emigration. Immunity. 2012;37:971–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka H, et al. Epigenetic Thpok silencing limits the time window to choose CD4(+) helper-lineage fate in the thymus. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:1183–1194. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bendelac A, et al. The biology of NKT cells. Annual review of immunology. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van der Meulen J, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX in normal development and disease. Epigenetics. 2014;9:658–668. doi: 10.4161/epi.28298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ntziachristos P, et al. Contrasting roles of histone 3 lysine 27 demethylases in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2014;514:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van der Meulen J, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX is a gender-specific tumor suppressor in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:13–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu H, et al. Critical roles of NOTCH1 in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. International journal of hematology. 2011;94:118–125. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0899-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pajcini KV, et al. Notch signaling in mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2011;25:1525–1532. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ntziachristos P, et al. From fly wings to targeted cancer therapies: a centennial for notch signaling. Cancer cell. 2014;25:318–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ntziachristos P, et al. Genetic inactivation of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature medicine. 2012;18:298–301. doi: 10.1038/nm.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamura T, et al. Inducible deposition of the histone variant H3.3 in interferon-stimulated genes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:12217–12225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805651200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elsaesser SJ, et al. New functions for an old variant: no substitute for histone H3.3. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2010;20:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maze I, et al. Every amino acid matters: essential contributions of histone variants to mammalian development and disease. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2014;15:259–271. doi: 10.1038/nrg3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mansour AA, et al. The H3K27 demethylase Utx regulates somatic and germ cell epigenetic reprogramming. Nature. 2012;488:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pengelly AR, et al. A histone mutant reproduces the phenotype caused by loss of histone-modifying factor Polycomb. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;339:698–699. doi: 10.1126/science.1231382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herz HM, et al. Histone H3 lysine-to-methionine mutants as a paradigm to study chromatin signaling. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2014;345:1065–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1255104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewis PW, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;340:857–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1232245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rao RC, Dou Y. Hijacked in cancer: the KMT2 (MLL) family of methyltransferases. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2015;15:334–346. doi: 10.1038/nrc3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cho YW, et al. PTIP associates with MLL3- and MLL4-containing histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:20395–20406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701574200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Issaeva I, et al. Knockdown of ALR (MLL2) reveals ALR target genes and leads to alterations in cell adhesion and growth. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:1889–1903. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi X, et al. An epigenetic switch induced by Shh signalling regulates gene activation during development and medulloblastoma growth. Nature communications. 2014;5:5425. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miller SA, et al. Jmjd3 and UTX play a demethylase-independent role in chromatin remodeling to regulate T-box family member-dependent gene expression. Molecular cell. 2010;40:594–605. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Euskirchen G, et al. SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling factors: multiscale analyses and diverse functions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:30897–30905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.309302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masliah-Planchon J, et al. SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling and human malignancies. Annual review of pathology. 2015;10:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chi TH, et al. Reciprocal regulation of CD4/CD8 expression by SWI/SNF-like BAF complexes. Nature. 2002;418:195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lazarevic V, et al. T-bet: a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:777–789. doi: 10.1038/nri3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pearce EL, et al. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2003;302:1041–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li Q, et al. Critical role of histone demethylase Jmjd3 in the regulation of CD4+ T-cell differentiation. Nature communications. 2014;5:5780. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cook KD, et al. T Follicular Helper Cell-Dependent Clearance of a Persistent Virus Infection Requires T Cell Expression of the Histone Demethylase UTX. Immunity. 2015;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thieme S, et al. The histone demethylase UTX regulates stem cell migration and hematopoiesis. Blood. 2013;121:2462–2473. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dahle O, et al. Nodal signaling recruits the histone demethylase Jmjd3 to counteract polycomb-mediated repression at target genes. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra48. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annual review of biochemistry. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]