Abstract

Background

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality following percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and is a patient safety objective of the National Quality Forum. However, no formal quality improvement program to prevent CI-AKI has been conducted. Therefore, we sought to determine if a six-year regional multi-center quality improvement intervention could reduce CI-AKI following PCI.

Methods and Results

We conducted a prospective multi-center quality improvement study to prevent CI-AKI (serum creatinine increase ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or ≥50% during hospitalization) among 21,067 non-emergent patients undergoing PCI at ten hospitals between 2007 and 2012. Six ‘intervention’ hospitals participated in the quality improvement intervention. Two hospitals with significantly lower baseline rates of CI-AKI, which served as “benchmark” sites and were used to develop the intervention and two hospitals not receiving the intervention were used as controls. Using time series analysis and multilevel poisson regression clustering to the hospital-level we calculated adjusted risk ratios (RR) for CI-AKI comparing the intervention period to baseline. Adjusted rates of CI-AKI were significantly reduced in hospitals receiving the intervention by 21% (RR 0.79; 95%CI: 0.67 to 0.93; p=0.005) for all patients and by 28% in patients with baseline eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (RR 0.72; 95%CI: 0.56 to 0.91; p=0.007). Benchmark hospitals had no significant changes in CI-AKI. Key qualitative system factors associated with improvement included: multidisciplinary teams, limiting contrast volume, standardized fluid orders, intravenous fluid bolus, and patient education about oral hydration.

Conclusions

Simple cost-effective quality improvement interventions can prevent up to one in five CI-AKI events in patients with undergoing non-emergent PCI.

Keywords: quality improvement, contrast-induced nephropathy, contrast media, PCI

Introduction

More than two million cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) procedures are performed in the United States each year.1 Depending on patient and procedural characteristics, contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) will occur in 3–14% of patients.2 When CI-AKI occurs, patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular events, prolonged hospitalization, end-stage renal disease, all-cause mortality, and increased acute care costs of over $7,500 per case.3–5

In response to the adverse effects of contrast exposure, the National Quality Forum established the patient safety objective to reduce the prevalence of CI-AKI6 and the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) published guidelines for CI-AKI prevention.7 However, preventive measures to reduce CI-AKI have been applied inconsistently in US hospitals8 with more than five-fold variability in adjusted rates of CI-AKI.2 Over a decade has passed with no reports of continuous quality improvement targeted at CI-AKI since the Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium reported on contrast nephropathy and multiple quality indicators from an 1998 to 2002 intervention.9 In an effort to reduce variation in practice patterns across hospitals and improve patient safety, we hypothesized that a high-intensity continuous quality improvement intervention could reduce the incidence of CI-AKI. We designed and implemented a multi-center continuous quality improvement intervention to reduce the incidence of CI-AKI across eight hospitals in the United States.2

Methods

Study Cohort

Hospitals: The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group (NNECDSG) is a voluntary regional consortium of clinicians, hospital administrators, and health care research personnel who seek to continually improve the quality, safety, effectiveness, and cost of coronary revascularization. Of ten member hospitals, eight agreed to participate in the study and two who did not were used as controls. Patients: Data were prospectively collected on consecutive patients undergoing PCI between January 1, 2007 and June 30, 2012 (n=21,067). Patients were excluded if they were emergent or had a history of renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy. Information was collected on patient characteristics, past medical, past cardiac history, cardiac anatomy and function, procedural priority, indication, process and outcomes using standard data collection instruments (available online at www.nnecdsg.org).

Identification of Benchmark and Intervention Hospitals

Using data from January 1, 2007 to October 30, 2008, two hospitals were identified as having significantly lower rates of CI-AKI (2.3% v. 6.6%, p<0.001) than the other hospitals. These two hospitals were identified as “benchmark” sites. Their experience was used to inform the intervention but these sites did not take part in the active intervention. Six hospitals agreed to participate in the intervention. Two hospitals did not participate in the study and were used as controls.

Quality Improvement Intervention Phase

The intervention phase began on November 1, 2008 and continued through June 30, 2012 directly following a two-day regional meeting focused on CI-AKI as an improvement target for NNECDSG hospitals. Participating hospitals agreed to: 1) form multidisciplinary teams including interventional cardiologists, cardiac catheterization lab managers and technicians, nursing representation from the intensive care unit and/or holding areas, cardiology administration, and nephrologists; 2) participate in monthly conference calls facilitated by a microsystems quality improvement coach; 3) participate in a process of identifying best practices through a formal review of the literature and structured interviews with benchmark sites; 4) participate in annual structured focus groups to capture qualitative data on barriers and successes to improvement; 5) have adjusted CI-AKI rates by hospital added to the NNECDSG bi-annual reports provided to all hospitals, administrators, and health professionals. In addition, hospitals were encouraged to have one member from each team undergo six months of quality improvement training in microsystems coaching. During the first year of the intervention, teams identified best practices by formal review of the literature as summarized by the primary investigator and a series of structured interviews with benchmark sites. Sites were encouraged but not required to implement identified best practices. In addition to monthly conference calls and annual focus groups, representatives from each hospital attended three regional NNECDSG meetings each year where reporting on trends of CI-AKI and discussions about implementing best practices, and novel approaches to minimize contrast were presented and discussed.

Determination of CI-AKI

The last pre-procedure serum creatinine and highest post-procedure serum creatinine obtained prior to discharge were used to determine the incidence of CI-AKI. As data was collected in the routine process of care there was no protocol-mandated collection of post-procedure serum creatinine at a given time period. CI-AKI was defined using the KDIGO Guidelines definition: ≥0.3 (mg/dL) within 48 hours of the procedure or ≥50% increase in serum creatinine from baseline at any time during the hospitalization.7 Patients were hospitalized on average for 2.5 days (median 3.0) during the baseline period and 2.7 days (median 3.2) during the follow-up period.

Quantitative analysis

Patient, disease, and procedural characteristics were compared between baseline and intervention time periods, overall and stratified by exposure: intervention, benchmark, control (Supplement Table S1). We calculated the contrast volume exceeding a predicted threshold using the maximum acceptable contrast dose (MACD, 5ml × body weight divided by baseline serum creatinine) and >3 times creatinine clearance.3,10 We used Chi-square tests for categorical data and Students t-tests for continuous data. To show temporal trends in the rates of CI-AKI we first performed interrupted time series analyses and plotted monthly adjusted rates of CI-AKI adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, urgent priority, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), number of diseased vessels > 70% stenosis, radial access, and baseline eGFR based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.11–13 Interrupted time series analysis compares the linear trend in values before and after the intervention. We used multilevel Poisson regression with a random intercept for each hospital. Poisson regession was employed for the binary outcome in to yield risk ratios (RR) between the intervention and baseline periods adjusting for the same covariates listed above. The standard error of multilevel regression allowed us to adjust for patient-level covariates while accounting for interdependence of patients within hospitals. In addition we conducted a nearest-neighbor propensity matched analysis to compare e baseline and intervention phases, for the intervention, benchmark and control hospitals separately, as well as combined. Since most CI-AKI improvement efforts and protocols were targeted towards high-risk patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, a priori analyses were repeated for patients with baseline eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2. All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA (Stata 11.2, College Station, TX, USA).

Evaluation of Quality Improvement Interventions

Annual structured focus groups of the multidisciplinary clinical teams were conducted at all intervention hospitals. Teams were asked guided open-ended questions about improvement efforts, barriers, successes, and quality improvement training. A research coordinator facilitated and taped all meetings. Field notes were recorded. All notes and meeting transcriptions were systematically evaluated using the grounded theory approach.14 We used open coding to develop initial themes, followed by axial and selective coding and aggregated across hospitals to find unifying themes. We aggregated key themes into domains. We then expanded our statistical methods to utilize the multilevel modeling methods reported by Bradley and colleagues15 to report on the magnitude of the success of each quality improvement strategy identified using the grounded theory approach in our qualitative analyses. We estimated risk ratios for each quality improvement strategy using univariable and multivariable multilevel Poisson regression clustering to hospital level to calculate adjusted RR with 95%CI of CI-AKI between the intervention and baseline periods adjusting for the covariates listed above.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all hospitals. Participants provided written informed consent to participate in focus groups.

Results

All six intervention hospitals formed multidisciplinary teams. The teams met independently every month separately or as part of monthly catheterization laboratory staff meetings with CI-AKI as a major focus. Each team included cardiologists, cardiac administrator(s), catheterization laboratory staff and manager(s), nursing managers, and a nephrologist. Each site participated in structured monthly multi-site conference calls for quality improvement training, provided status updates, and shared successes and barriers to improvement. All teams participated in annual structured focus groups. Three of the six hospitals elected to undergo additional microsystems quality improvement training.

Between January 1, 2007 and June 30, 2012, 21,067 consecutive patients underwent a non-emergent PCI at the eight participating hospitals and two control hospitals. Compared to the baseline phase (n = 6,983), patients in the intervention phase (n = 14,084) were older, more likely to have major co-morbidities including diabetes, hypertension, prior myocardial infarction, history of previous PCI and congestive heart failure, and had more multivessel coronary artery disease (Table 1). Radial access was more common during the intervention period. Total contrast volumes decreased from 290.8 ml/case in the baseline period to 237.5 ml/case during the intervention (p<0.001). Overall, fewer patients exceed MACD (28.5% and 19.7%, p <0.001) or 3 times the creatinine clearance (50.5% and 41.0%, p <0.001). There were small differences in patient and procedural characteristics between intervention, benchmark, and control hospitals (Supplement Table S1).

Table 1.

Patient and Procedural Characteristics

| Variable | Baseline | Intervention | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 6,983 | 14,084 | |

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Age | 64.4 ± 12.0 | 64.8 ± 11.7 | 0.024 |

| Female | 30.6 | 30.1 | 0.445 |

| Body mass index | 30.4 ± 6.4 | 30.5 ± 6.3 | 0.161 |

| Current smoker | 21.1 | 23.0 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.0 | 34.3 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13.0 | 14.4 | 0.006 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 19.5 | 20.1 | 0.259 |

| Cardiac Disease | |||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 27.6 | 29.7 | 0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 36.8 | 38.7 | 0.010 |

| Prior CABG | 18.4 | 19.5 | 0.054 |

| Hypertension | 74.8 | 78.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 84.0 | 85.6 | 0.003 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10.1 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction < 40% | 5.0 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Number of diseased vessels >70% stenosis | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Renal Function | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 78.2 ± 23.4 | 80.0 ± 25.2 | <0.001 |

| Pre-Procedural Characteristics | |||

| Urgent priority | 63.5 | 62.1 | 0.045 |

| Pre-procedural IABP | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.445 |

| Procedural Characteristics | |||

| Radial access | 0.5 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Sheath size 6 | 80.2 | 52.2 | <0.001 |

| Number of stents | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Contrast volume | 290.7 ± 2739.9 |

222.6 ± 99.1 | 0.005 |

| MACD Limit | 463.0 ± 152.6 |

476.3 ± 161.6 |

<0.001 |

| CCCx3 Limit | 234.7 ± 70.1 | 240.1 ± 75.6 | <0.001 |

| Exceeding MACD | 28.5 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Exceeding CCCx3 | 50.5 | 41.0 | <0.001 |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Length of hospitalization | 2.5 ± 3.0 | 2.7 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump.

Change in CI-AKI

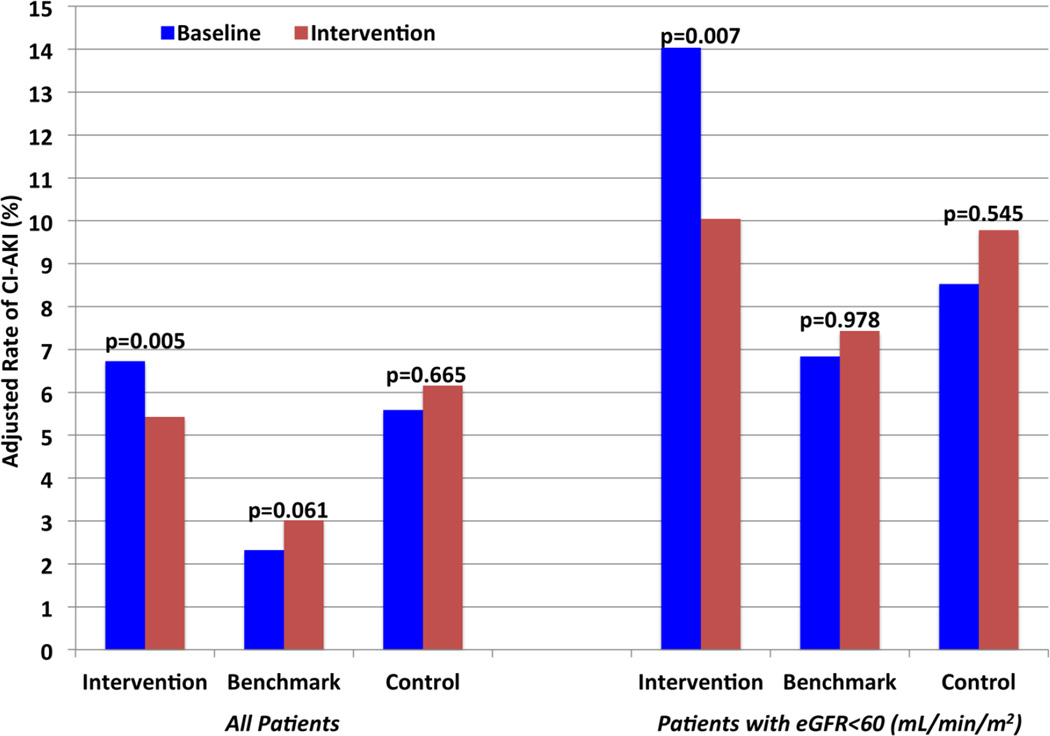

Using a prospective quality improvement intervention, the rate of CI-AKI, adjusted for case-mix, was significantly reduced in the six intervention hospitals from 6.7% during the baseline period to 5.4% (p=0.005, Figure 1, left) during the intervention period (crude rates 6.6% and 5.5%). CI-AKI in benchmark hospitals changed from 2.3% in the baseline period to 3.0 (crude rates 2.3% and 3.1%) during the intervention period (p=0.061). Control hospitals had no significant difference in CI-AKI with 5.0% at baseline and 6.1% (crude rates 5.0% and 6.2%) during the intervention period (p=0.665).

Figure 1. Adjusted Rates of CI-AKI.

Adjusted rates of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) are plotted for baseline (blue) and the intervention (red) phases for intervention and benchmark hospitals. The graph is divided by all patients (left) and high-risk patients with eGFR<60 (mL/min/m2 to the right).

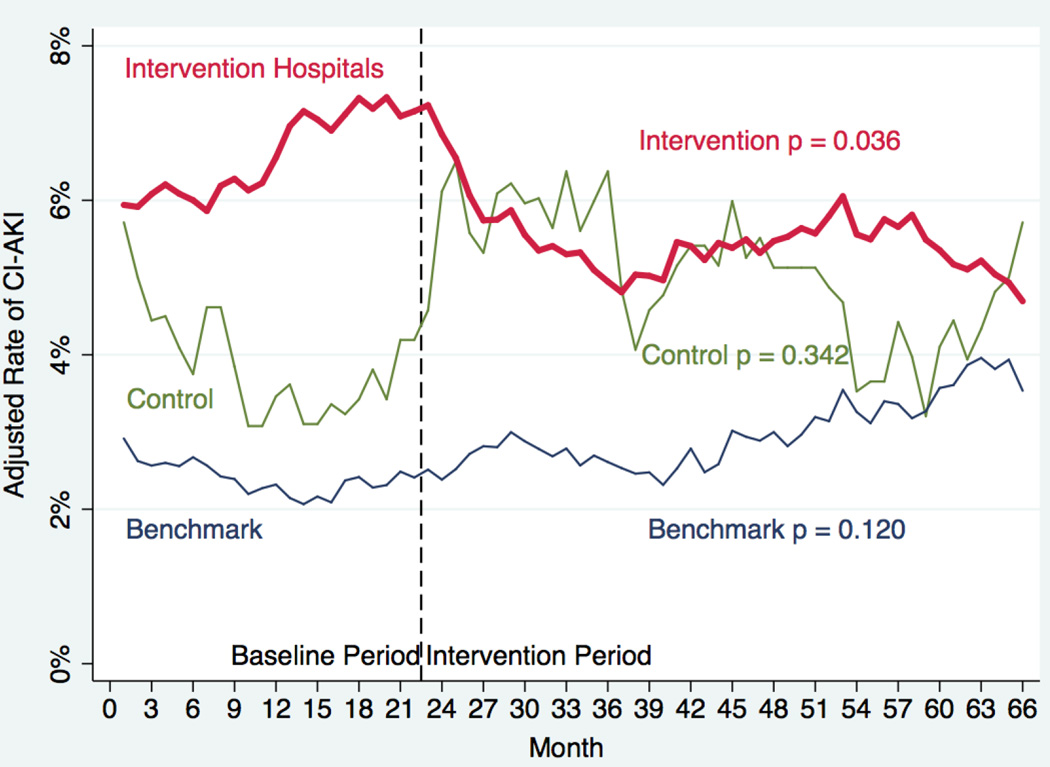

We plotted adjusted rates of CI-AKI by month over time (Figure 2). Using interrupted time series analyses we confirmed a statistically significant reduction in adjusted rates of CI-AKI from baseline to follow-up in the intervention group (coefficient −0.011; p = 0.036). There were no significant change in adjusted rates of CI-AKI in the benchmark hospitals (coefficient 0.008; p = 0.120) or control hospitals (coefficient 0.014; p=0.342).

Figure 2. Adjusted Rates of CI-AKI Over Time.

Adjusted rates of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is plotted by month stratified by intervention hospitals (red), benchmark hospitals (blue), and control hospitals (green) using interrupted time series analysis. The vertical dashed line represents the start of the quality improvement intervention.

After hierarchical adjustment for known confounders (Table 2), intervention hospitals significantly reduced CI-AKI by 21% for all patients with RR 0.79 (95%CI: 0.67 to 0.93; p = 0.005). Benchmark and control hospitals had no significant change in CI-AKI during the intervention period: benchmark hospitals (RR 1.32; 95%CI: 0.99 to 1.78, p=0.061); control hospitals (RR 1.15; 95%CI: 0.61 to 2.15, p=0.665).

Table 2.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury before and after intervention

| All Patients | Patients with eGFR<60 (mL/min/m2) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Exposure |

RR | 95%CI | P-value | RR | 95%CI | P-value |

| Intervention hospitals |

0.79 | (0.67, 0.93) | 0.005 | 0.72 | (0.56, 0.91) | 0.007 |

| Benchmark hospitals |

1.32 | (0.99, 1.78) | 0.061 | 1.01 | (0.65, 1.55) | 0.978 |

| Control hospitals | 1.15 | (0.61, 2.15) | 0.665 | 1.42 | (0.45, 4.46) | 0.545 |

Abbreviations: Risk Ratio and 95% confidence intervals estimated from poisson regression clustering to hospital and adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, urgent priority, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), number of diseased vessels > 70% stenosis, radial access, and baseline eGFR.

We then identified nearest neighbor matches for the baseline (n=6,980) and intervention phases (n=6,979). Using propensity-matched patients in the intervention hospitals (n=8,015) CI-AKI was reduced from 6.6% to 4.5% with a RR of 0.68 (95%CI: 0.56 to 0.82; p <0.001). There was no change in the benchmark hospitals (2.3% to 2.3%, RR 1.02; 95%CI: 0.71 to 1.45, p=0.919) or control hospitals (5.0% to 5.9%; RR 1.17; 95%CI: 0.60 to 2.30, p=0.647).

Sub-group Analyses

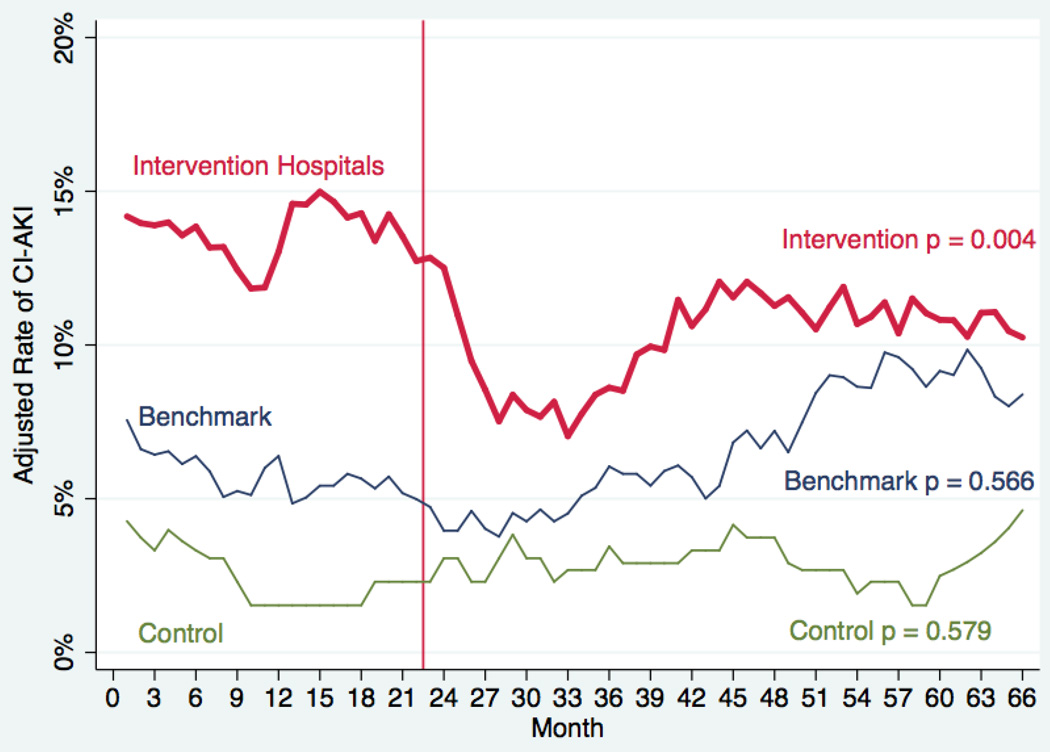

There were 4,131 patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 considered at high-risk of CI-AKI at baseline. Among these patients, CI-AKI was reduced in the intervention hospitals from 14.0% to 10.0% (p=0.007) with crude CI-AKI rates 13.9% and 10.1%, (Figure 1, right). High-risk patients in the benchmark (6.8% to 7.4%; crude rates 5.8% and 8.1%) and control hospitals (10.8% and 9.9%; crude rates 8.6% and 9.9%) had no significant changes in CI-AKI. Interrupted time series analysis demonstrated intervention hospitals significantly reduced the rate of CI-AKI (Figure 3, p = 0.004), however no significant decreases in the rate of CI-AKI in the benchmark (p = 0.566) or control (p = 0.579) hospitals. After hierarchical adjustment for known confounders (Table 2), intervention hospitals significantly reduced CI-AKI by 28% in high-risk patients with baseline eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (RR 0.72; 95%CI: 0.57 to 0.91; p = 0.007). Benchmark and control hospitals had no significant change in CI-AKI during the intervention period among patients with baseline eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2: benchmark (RR 1.01; 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.55, p = 0.978); control (RR 0.98; 95%CI: 0.64 to 1.52, p = 0.9).

Figure 3. Adjusted Rates of CI-AKI Over Time for patients with eGFR<60 (ml/min/m2).

Adjusted rates of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is plotted by month stratified by intervention hospitals (red), benchmark hospitals (blue), and control hospitals (green) using interrupted time series analysis. The vertical dashed line represents the start of the quality improvement intervention.

Among the patients with eGFR≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2, CI-AKI was reduced from 4.5% to 4.2% in the intervention hospitals (RR 0.92; 95%CI: 0.73 to 1.14, p=0.430). CI-AKI increased among the benchmark hospitals from 1.4% to 1.9% (RR 1.52; 95%CI: 1.01 to 2.29, p=0.046) and among the control hospitals from 3.8% to 5.1% (RR 1.21; 95%CI: 0.54 to 2.74, p=0.642).

We then determined if individual hospitals in the intervention group all succeeded in reducing CI-AKI. We found that four of the six hospitals reduced their rate of CI-AKI for all patients and among the high-risk patients with eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Three of these hospitals reducing the rate of CI-AKI had a team member undergo additional microsystems quality improvement coaching training. The two hospitals that did not reduce the rate of CI-AKI demonstrated no significant temporal trends.

Benchmark hospitals were selected for best practices in preventing CI-AKI.2 As such, during the baseline period intervention hospitals had 3-fold the rate of CI-AKI for all patients (RR 2.94; 95%CI: 2.23–3.88, p<0.001) and a 2-fold higher rate of CI-AKI among high-risk patients with eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (RR 2.19; 95%CI: 1.47–3.26, p<0.001) compared to benchmark hospitals. During the intervention, intervention hospitals reduced the difference in CI-AKI from 2.94 to 1.82 (RR 1.82; 95%CI: 1.23–2.67, p=0.002) with no significant difference among the high-risk patients with eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (RR 1.25; 95%CI: 0.96–1.64, p=0.1).

Other Clinical Endpoints

Among the six intervention hospitals there were significant reductions observed in other clinical endpoints including in-hospital mortality (0.6% to 0.2%; RR 0.44; 95%CI: 0.24–0.82, p = 0.009), and bleeding complications (1.7% to 1.0%; RR 0.59; 95%CI: 0.43 to 0.83, p=0.002); however there was no change in emergent CABG (0.2% to 0.1%; RR 0.76; 95%CI: 0.30–1.97, p = 0.578). Benchmark clinical endpoints improved for bleeding (1.4% to 0.8%; RR 0.55; 95%CI: 0.36 to 0.85, p=0.006) and no difference for in-hospital mortality (0.2% to 0.4%; RR 1.98; 95%CI: 0.80 to 4.86, p=0.137) or emergent CABG (0.17% to 0.04%; RR 0.21; 95%CI: 0.04 to 1.06, p=0.059). Control hospitals had no significant changes in in-hospital mortality (0.4% to 0.5%; RR 1.31; 95%CI: 0.14 to 12.55, p=0.817), bleeding (0.72% to 0.62%, p=0.872; RR 0.87; 95%CI: 0.16 to 4.75, p=0.873), or emergent CABG (0.00% and 0.47%, p=0.252).

Characteristics of Improvement Intervention

Using qualitative analysis we identified themes associated with the success of the quality improvement effort, organizing them by domain (Table 3). High functioning teams had multidisciplinary members with clinical champions and multiple team leaders for core improvement targets. Key barriers for teams conducting improvement efforts included variation in physician ordering, changing NPO orders, and the need to unlearn old protocols. Key improvement successes included change in behavior with an increased awareness towards CI-AKI prevention, standardized order sets, minimizing contrast volume by reducing test injections and eliminating ventriculography, mandating procedure delays to allow for IV fluid bolus, staging procedures, and patient self-hydration.

Table 3.

Domains and Key Themes in Hospital CI-AKI Quality Improvement

| Domain | Key Themes in CI-AKI Performance |

|---|---|

| Teams | High performance teams had multidisciplinary team members, clinical champions, empowered nurses, multiple team champions, protected time for team meetings and improvement work, regular scheduled meetings, and quality improvement training (LEAN, six-sigma, microsystems) |

| Intervention Barriers | Challenges included variation in physician ordering, variation in protocols, unlearning old protocols, NPO status of the patient, education, documentation, data collection, working with transferring facilities, physician and patient non-compliance to orders, staffing, resources, time, staff buy-in, trade- offs with other quality targets |

| Patient and Process Interventions |

Hospitals adopted benchmark hospital protocols, standardized intravenous order sets, reduced NPO status to 2–4 hours prior to procedure, stop nephrotoxic drugs prior to procedure. Hospitals also developed readiness checklists including volume status of the patient and fluid bolus, delayed procedures to allow for fluid bolus, limited contrast volume and exposure, eliminating left ventriculography, and conducted patient education about self-hydration using oral fluids (8× 8oz glasses of water 12 hours pre and 12 hours post procedure) |

| Factors supporting success | Hospital changes in behavior during the intervention included increased awareness, standardized intravenous fluid order sets, reduced NPO status to 2–4 hours prior to procedure, staff and institutional buy-in, hydrating patients before and after the procedure, staff and patient education, limiting contrast volume, pre-calculated safe contrast dose per patient using the maximum acceptable contrast dose equation (5mL × body weight in Kg / baseline serum creatinine), staging procedures, delaying procedures to allow for fluid bolus, and quality improvement training |

We then conducted univariable and multivariable hierarchical Poisson regression to evaluate the magnitude of the effect for each identified quality improvement strategy reported by intervention hospitals. We show the number of centers reporting the use of the strategy along with crude and adjusted relative risk reductions for each strategy in Table 4. Based on our quantitative and qualitative data, we identified and statistically modeled a number quality improvement strategies used by centers to prevent CI-AKI using statistical methods reported by Bradley and colleagues.15 Among the 6 intervention hospitals, only 4 hospitals were identified as having a change in culture in how CI-AKI prevention strategies were incorporated in staff knowledge, attitudes, and practice included statements by teams stating “people care about this now”. Among these 4 hospitals, there was consistency in having clinical champions, reducing NPO time, educating patients to self-hydrate, and teams had undergone quality improvement training. The effect of other strategies in reducing CI-AKI varied across hospitals (Table 4).

Table 4.

Strategies to Prevent CI-AKI

| QI Strategy | Number of Centers (out of 6) |

Crude RR (95%CI) | Adj RR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Champions | 5 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.82 (0.70, 0.97) |

| Adopting benchmark protocols | 3 | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.88) |

| Change in culture | 4 | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88) |

| Standardizing fluid orders | 3 | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.88) |

| Requiring fluid bolus prior to procedure | 3 | 0.85 (0.72, 0.99) | 0.77 (0.63, 0.93) |

| Reducing NPO status | 4 | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88) |

| Using checklists | 2 | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) | 1.17 (0.90, 1.53) |

| Procedure delay for fluids | 3 | 1.05 (0.88, 1.25) | 0.98 (0.77, 1.24) |

| Patient education | 4 | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88) |

| QI training | 4 | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88) |

| QI microsystems coach-the-coach training | 3 | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.88) |

| New electronic medical record | 1 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.80) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.74) |

| Automate flagging of high risk patients | 2 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.77) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.72) |

| Flag high risk patients | 2 | 0.74 (0.55, 0.98) | 0.75 (0.53, 1.05) |

| Reduced patients exceeding safe dose of contrast | 1 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.80) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.74) |

Abbreviations: Risk Ratio and 95% confidence intervals estimated from (crude, left column) univariable poisson regression and (adjusted, right column) poisson regression clustering to hospital and adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, urgent priority, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), number of diseased vessels > 70% stenosis, radial access, and baseline eGFR.

Discussion

Our quality improvement efforts significantly reduced adjusted rates of CI-AKI across six intervention hospitals by 21% with no change observed in the benchmark or control hospitals. In a propensity matched analysis, CI-AKI was reduced by 32% across the six intervention hospitals with no chance in the benchmark or control hospitals. Among high risk patients with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2, adjusted rates of CI-AKI were reduced by 28% in the intervention hospitals. The intervention to reduce CI-AKI included the formation of multidisciplinary teams, adoption of standardized order sets for IV volume expansion, reducing NPO status to 2–4 hours prior to the procedure, patient education about self-hydration with oral fluids before and after the procedure and efforts to decrease contrast volume. In this six-year study, we demonstrate simple cost-effective hospital quality improvement interventions can prevent CI-AKI in one out of five patients undergoing non-emergent PCI and in one out of four patients with baseline chronic kidney disease (eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2).

There have been several studies of interventions to reduce the risk of CI-AKI. Randomized trials have evaluated volume expansion protocols, the use of normal saline, sodium bicarbonate, n-acetylcysteine, or other reagents thought to mitigate the risk of CI-AKI.16,17 Other studies have examined the type and/or volume of contrast.18 In general, study results have supported volume expansion and minimizing contrast exposure.2,3,19 However, there have been no investigations of an interdisciplinary quality improvement effort to prevent CI-AKI in over a decade since the Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium reported on contrast nephropathy and multiple quality indicators from a 1998 to 2002 intervention.9 Moscucci and the Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium leveraged similar techniques to our early work in the NNECDSG and demonstrated significant improvement across multiple quality indicators including contrast nephropathy.9 Using a high-intensity quality improvement design and leveraging quality improvement coaching, in this investigation we promoted change from within organizations to apply the best evidence based medicine to prevent CI-AKI. We did this by forming multidisciplinary teams, provided a structure for protocol transparency and sharing, data feedback mechanisms, and quality improvement training.

Key attributes associated with improvement efforts reported by hospital teams included the development of multidisciplinary teams with clinical champions, standardization of fluid protocols including mandating an IV fluid bolus prior to the procedure based on benchmark hospital successes, decreasing NPO length from 12 hours to 2–4 hours, patient education to self-hydrate before and after the procedure with 8, 8oz. glasses of water, and minimizing contrast volume during the procedure by eliminating left ventriculography, limiting contrast, and calculating safe contrast volume thresholds prior to PCI (using the maximum acceptable contrast dose).3

Qualitative findings identified key challenges to implementing clinical workflow improvements during our intervention period. Teams had difficulties in implementing new fluid order sets when migrating from physician write-in orders to a standardized fluid protocol across all providers using either a normal saline17 or sodium bicarbonate approach.16 Cultural changes in NPO status of the patient commonly had to be changed from 12 hours (or before midnight) to 2–4 hours prior to the procedure. High functioning teams adapted novel approaches to patient volume expansion and prevention against dehydration by developing patient educational materials to encourage self-hydration. Recent evidence supports the use of oral hydration as an effective alternative to IV fluids and was incorporated into patient educational.20,21 The greater use of both oral and IV fluids likely worked to reduce the proportion of subjects who were volume depleted going into the procedure and decreased the risk of CI-AKI.

During our study cardiologists adopted new techniques and technologies to minimize the use of contrast. These included routinely calculating a pre-specified safe contrast-limit for the procedure and the use of contrast sparing devices. In some hospitals, when the contrast limits where met during a procedure, new approaches evolved to stage procedures to avoid exceeding the maximum acceptable contrast dose.3 Overall, hospitals reduced the volume of contrast during the intervention period from 231 mL to 219 mL per case (p = 0.038, Table 1). It is likely that engineering stops in the clinical work-flow to allow for a procedure to be delayed if the prescribed volume expansion has not been completed and to stage a PCI if the contrast volume exceeds a predicted threshold (5ml × body weight divided by baseline serum creatinine, or >3 times creatinine clearance)3,10 contributed significantly to the decrease in CI-AKI. Indeed, fewer patients exceed a safe dose of contrast during the intervention period using either the MACD3 (28.5% at baseline and 19.7% during the intervention, p <0.001) or 3 times the creatinine clearance (50.5% and 41.0%, p <0.001).3,10 Intervention hospitals had a much larger reduction in patients exceeding the MACD with 24.6% compared to baseline at 41.9% (p <0.001), while benchmark hospitals showed a small reduction of 13.0% during the intervention compared to 17.0% at baseline (p <0.001). Regarding changes in contrast type, benchmark hospitals used Isovue (iopamidol, Bracco, Monroe, NJ, USA) in 95.4% of cases at baseline and 97.1% during the intervention. Intervention hospitals from baseline to post-intervention increased their use of Isovue from 2.4% to 5.1%, Omnipaque (iohexol, General Electric Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) by 8.9% to 10.5%, Ultravist (iopromide, Bayer, Whippany, NJ, USA) by 4.6% to 11.9%, and reduced Visipaque (iodixanol, General Electric Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) from 30.9% to 26.4%.

During our improvement intervention we documented a small increased use of a radial artery access. Radial access avoids cannulation of the descending aorta and may reduce the risk of atheroembolic renal disease. Radial artery access also decreases the risk of bleeding that can be associated with renal damage. Our analysis cannot exclude the possibility that factors other than the intervention might have affected the outcomes, therefore we controlled for radial access in our models.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not conduct a randomized controlled trial, which raises the question of whether our results could be secondary to unmeasured confounding. We did control for differences in patient characteristics between the baseline and intervention periods with special attention to those known to be associated with CI-AKI. In the event our study is limited by unmeasured confounding, we demonstrate that patients presenting for PCI in our intervention period had more complex disease and comorbidities than thos patients during our baseline phase; therefore, not adjusting for these factors likely biases our effects towards the null and underestimates the true effect of the intervention. Second, hospitalization time for our PCI patients was short, averaging 48 hours, and did not allow for the serial measurement of serum creatinine for the five days commonly used in randomized trials to document the trend in renal function given that the peak incidence of CI-AKI is thought to occur at 3–5 days.22 We were limited to our registry data collection which included a baseline pre-procedure creatinine and the highest post-procedure serum creatinine prior to discharge. As such, we likely underestimated the true incidence of CI-AKI and may have underestimated the true benefit of the intervention. However, the average length of stay was 2.7 days (median 2 days) for the baseline period and 2.6 days (median 2 days) for the follow-up period; therefore most patients at least had 48 hours of follow-up prior to discharge. Third, starting in 2010 our quality improvement effort competed in some centers with efforts to introduce radial access as a key quality driver to reduce length of stay and bleeding complications. Qualitative data captured from teams confirmed radial access was a competing quality target with CI-AKI and may have diverted AKI improvement team efforts from mitigating AKI towards focusing on radial access adoption, leading to an underestimate of the true potential effect of our intervention. Fourth, responses to the baseline and intervention phase focus groups may be subject to recall bias. Teams not meeting their goals or who felt they were under performing due to barriers or attitudes towards improvement could be more likely to recall adverse aspects of their performance or institutional buy-in. Teams that performed well may more easily recall successes or fail to recall failures or barriers to improvement. Fifth, we acknowledge the implementation of EMRs were occurring during our study period. Our qualitative analyses from structured annual focus groups and monthly conference calls demonstrated that EMR installation (such as Epic) was a priority barrier against CI-AKI improvement efforts and teams. Only one hospital underwent an Epic or other EMR transitions during the study; however the teams was also then able to develop the standardized order sets to be incorporated with the initialization of the new EMR. When we model the impact of the site implementing a new EMR the adjusted RR of CI-AKI is 0.58 (0.46, 0.74, Table 4). Sixth, while intervention hospitals significantly reduced their rate of CI-AKI, they did not achieve similar performance to the CI-AKI rate of the benchmark hospitals. The benchmark hospitals began with a consistent significantly superior low rate of CI-AKI. Even by adopting bench the intervention hospitals were able to significantly improve their rate of CI-AKI, but were not able to reach the baseline rate of the benchmark hospitals for all patients, however intervention hospitals were not significantly different from benchmark hospitals among high risk patients with eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2. This may suggest that the mere adoption of a formula may not be sufficient to maximize prevention of CI-AKI. Despite efforts to standardize order sets, educate staff, and change culture teams from benchmark sites very well may still differ in their detailed approaches not captured by a CI-AKI protocol. Lastly, there is a concern about generalizability of the results. However, we know the NNECDSG risk models have been well generalized to other cardiac surgery populations in the United States and believe the lessons learned in our study will be generalizable to other patient populations and hospitals across the United States. From our experience, the formation of multidisciplinary teams to evaluate the system of care for patients undergoing non-emergent PCI can identify cost-effective solutions to prevent CI-AKI from standardizing fluid orders, learning how to minimize contrast use, and educating patients to self-hydrate. We found this approach to be effective in multiple centers in our region.

There are likely to be additional randomized trials of specific interventions to decrease the risk of CI-AKI. Currently, the PRESERVE trial will aid in our understanding of whether sodium bicarbonate, normal saline, n-acetylcysteine, or combinations of these agents reduce the risk of CI-AKI.23 While trials may identify additional tools to help avoid the development of CI-AKI, our experience provides a simple path towards CI-AKI prevention using simple team-based quality improvement implementation techniques that are immediately available to anybody caring for an at risk population.

In summary, to our knowledge, this research is the first multi-centered approach to preventing CI-AKI using simple quality improvement implementation techniques. By developing multidisciplinary teams, routine meetings, incorporating standardized fluid protocols, mandating IV fluid boluses prior to the procedure, limiting dehydration of the patient prior to the procedure, and limiting contrast dye volume, CI-AKI was prevented in one out of every five patients undergoing non-emergent PCI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NNECDSG hospitals, and quality improvement teams participating in the CI-AKI quality improvement initiative.

Dr. Brown received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01 HS018443). Additional funding was provided for Dr. Sarnak by from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK078204), and the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

All other authors have no conflicts of interest or financial information to disclose in relation to this research.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JR, McCullough PA, Splaine ME, Davies L, Ross CS, Dauerman HL, Robb JF, Boss R, Goldberg DJ, Fedele FA, Kellett MA, Phillips WJ, Ver Lee PN, Nelson EC, Mackenzie TA, O'Connor GT, Sarnak MJ, Malenka DJ. How do centres begin the process to prevent contrast-induced acute kidney injury: a report from a new regional collaborative. BMJ quality & safety. 2012;21:54–62. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JR, Robb JF, Block CA, Schoolwerth AC, Kaplan AV, O'Connor GT, Solomon RJ, Malenka DJ. Does safe dosing of iodinated contrast prevent contrast-induced acute kidney injury? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:346–350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.910638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James MT, Samuel SM, Manning MA, Tonelli M, Ghali WA, Faris P, Knudtson ML, Pannu N, Hemmelgarn BR. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and risk of adverse clinical outcomes after coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:37–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.974493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Quality Forum. Safe practices for better healthcare 2006 Update : a consensus report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lameire N, Kellum JA. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and renal support for acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 2) Crit Care. 2013;17:205. doi: 10.1186/cc11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elicker BM, Cypel YS, Weinreb JC. IV contrast administration for CT: a survey of practices for the screening and prevention of contrast nephropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1651–1658. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moscucci M, Rogers EK, Montoye C, Smith DE, Share D, O'Donnell M, Maxwell-Eward A, Meengs WL, De Franco AC, Patel K, McNamara R, McGinnity JG, Jani SM, Khanal S, Eagle KA. Association of a continuous quality improvement initiative with practice and outcome variations of contemporary percutaneous coronary interventions. Circulation. 2006;113:814–822. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurm HS, Dixon SR, Smith DE, Share D, Lalonde T, Greenbaum A, Moscucci M, Registry BMC. Renal function-based contrast dosing to define safe limits of radiographic contrast media in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anonymous. Executive summary-K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S17–S31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best PJ, Reddan DN, Berger PB, Szczech LA, McCullough PA, Califf RM. Cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease: insights and an update. Am Heart J. 2004;148:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy EM, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. The effect of acute renal failure on mortality. A cohort analysis. Jama. 1996;275:1489–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research : techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage Publications Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, Barton BA, Webster TR, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Curtis JP, Nallamothu BK, Magid DJ, McNamara RL, Parkosewich J, Loeb JM, Krumholz HM. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2308–2320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merten GJ, Burgess WP, Gray LV, Holleman JH, Roush TS, Kowalchuk GJ, Bersin RM, Van Moore A, Simonton CA, 3rd, Rittase RA, Norton HJ, Kennedy TP. Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy with sodium bicarbonate: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291:2328–2334. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomon R, Werner C, Mann D, D'Elia J, Silva P. Effects of saline, mannitol, and furosemide to prevent acute decreases in renal function induced by radiocontrast agents. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1416–1420. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R. Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1527–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JR, Block CA, Malenka DJ, O'Connor GT, Schoolwerth AC, Thompson CA. Sodium bicarbonate plus N-acetylcysteine prophylaxis: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1116–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho R, Javed N, Traub D, Kodali S, Atem F, Srinivasan V. Oral hydration and alkalinization is noninferior to intravenous therapy for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Journal of interventional cardiology. 2010;23:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiremath S, Akbari A, Shabana W, Fergusson DA, Knoll GA. Prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: is simple oral hydration similar to intravenous? A systematic review of the evidence. PloS one. 2013;8:e60009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maioli M, Toso A, Leoncini M, Micheletti C, Bellandi F. Effects of hydration in contrast-induced acute kidney injury after primary angioplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;4:456–462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.961391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisbord SD, Gallagher M, Kaufman J, Cass A, Parikh CR, Chertow GM, Shunk KA, McCullough PA, Fine MJ, Mor MK, Lew RA, Huang GD, Conner TA, Brophy MT, Lee J, Soliva S, Palevsky PM. Prevention of Contrast-Induced AKI: A Review of Published Trials and the Design of the Prevention of Serious Adverse Events following Angiography (PRESERVE) Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 doi: 10.2215/CJN.11161012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.