Abstract

Background

Minimal Change Disease (MCD) in relapse is associated with increased podocyte CD80 expression and elevated urinary CD80 excretion, whereas focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) has mild or absent CD80 podocyte expression and normal urinary CD80 excretion.

Methods

One patient with MCD, one patient with primary FSGS and three patients with recurrent FSGS after transplantation received CD80 blocking antibodies (abatacept or belatacept). Urinary CD80 and CTLA-4 were measured by ELISA. Glomeruli were stained for CD80.

Results

After abatacept, urinary CD80 became undetectable with concomitant transient resolution of proteinuria in the MCD patient. In contrast, proteinuria remained unchanged after abatacept or belatacept therapy in one patient with primary FSGS and in two recurrent FSGS subjects despite the presence of mild CD80 glomerular expression but normal urinary CD80 excretion. One patient with recurrent FSGS after transplantation had elevated urinary CD80 excretion immediately after surgery which fell spontaneously before abatacept. After Abatacept, his proteinuria remained unchanged for 5 days despite normal urinary CD80 excretion.

Conclusion

These observations are consistent with a role of podocyte CD80 in the development of proteinuria in MCD. In contrast, CD80 may not play a role in recurrent FSGS since urinary CD80 is only increased transiently after surgery and normalization of urinary CD80 did not result in resolution of proteinuria.

Keywords: CD80, CTLA-4, Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis, Minimal Change Disease

Introduction

Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome (INS) includes three histological variants: Minimal Change Disease (MCD), Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and Mesangial Proliferative Glomerulonephritis [1]. In contrast to patients with idiopathic FSGS, patients with MCD present with nephrotic syndrome at an earlier age, usually respond to corticosteroids and have an excellent long-term prognosis [2]. Despite these clinical differences, it is still a matter of debate whether MCD and FSGS are two different entities or represent a continuum of the same disease at different stages. Indeed, histopathologic diagnosis is not always definitive since podocyte foot process effacement may be the only histological finding in the early stage of FSGS [3].

Both MCD and FSGS are considered podocytopathies [4]. Our group reported the expression of de novo CD80 in podocytes of MCD patients during relapse, and this was associated with increase shedding of intact CD80 molecules into the urine [5,6]. The potential causal role for CD80 in the proteinuria is suggested by the fact that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced proteinuria is also associated with podocyte CD80 expression and that proteinuria in this model is prevented in mice lacking full length CD80 [7].

Patients with primary FSGS have urinary CD80 levels no different from those observed in control subjects despite the presence of massive proteinuria, suggesting that the presumed mechanism of proteinuria in primary FSGS is not CD80-driven [6] and rather mediated by a circulating factor [8]. While preliminary studies suggest a role of cardiotrophin-like cytokine-1 [9], the most intensely studied candidate for FSGS is circulating suPAR (soluble urokinase type plasminogen activator receptor) that triggers podocyte integrin activation and proteinuria [10-12].

CTLA-4, a CD80 inhibitor, is known to be expressed in cultured human podocytes exposed to Poly:IC (a toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand) [13]. Nevertheless, we found no significant differences in urinary excretion of CTLA-4 in MCD patients during relapse compared to that observed during remission [5]. We have therefore hypothesized that if CTLA-4 is involved in MCD, regulation may be at the local level, with inadequate censoring of podocyte CD80 expression due to an impaired production of CTLA-4 by podocytes [14]. Thus, if MCD represents a defect in the autoregulatory CD80/CTLA-4 axis in the podocyte, one might predict that the administration of CTLA-4 (CTLA4-IgG1) to a subject with MCD would result in an inhibition of podocyte and urinary CD80 with resolution of proteinuria, whereas administration of CTLA-4–IgG1 infusion to FSGS patients would not be beneficial as in this condition CD80 is likely not involved in the pathogenesis of the proteinuria.

Here we present our experience with the CD80 blocking antibodies (abatacept or belatacept) in one patient with relapsing MCD, one patient with primary FSGS and three patients with recurrence of FSGS after kidney transplantation.

Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Declaration of Istanbul. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida and The Johns Hopkins University, and written informed consent was obtained before participation. The Institutional Review Board provided approval for this study before abatacept and belatacept were infused.

Patient selection

Minimal Change disease and FSGS were defined by renal biopsy according to established criteria by the International Study for Kidney Diseases in Children [15]. One MCD and 4 patients with primary FSGS were included in this study. Three of the patients with primary FSGS were studied after recurrence of the nephrotic syndrome in the transplanted kidney. Recurrence after transplantation was defined based on the presence of nephrotic syndrome and podocyte foot process effacement in the kidney biopsy.

Urinary CD80 and CTLA-4 measurements

Urinary CD80 was measured by Elisa using a commercially available kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). We measured urinary CTLA-4 according to Oaks and Hallet with minor modifications [16]. CD80 and CTLA-4 results were adjusted for urinary creatinine excretion.

Urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio

Urine protein was calculated using the BioRad Protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and urine creatinine with the Creatinine Companion (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA).

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen biopsy slides were equilibrated to room temperature and water precipitation was absorbed carefully. Slides were fixed in 95% ethanol for 10 minutes. Sections were washed with PBS. Unspecific sites were blocked for 30 minutes with normal goat and donkey 5% serum/PBS. Sections were incubated with monoclonal synaptopodin antibody (1:1) for 1 hour at room temperature to reveal podocytes. After washing with PBS × 3 times (3 minutes), slides were incubated with anti-B7-1 antibody (1:100) (goat, R&D) for 1 hour at room temperature, then washed with PBS ×3 times (3 minutes), followed by incubation with chicken anti-goat 488 and chicken anti-mouse 594 Alexa Fluor antibodies (1:1500, Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature. Following PBS wash × 3 times (3 minutes), sections were incubated with DAPI/PBS solution for 5 minutes, and then washed with PBS and water.

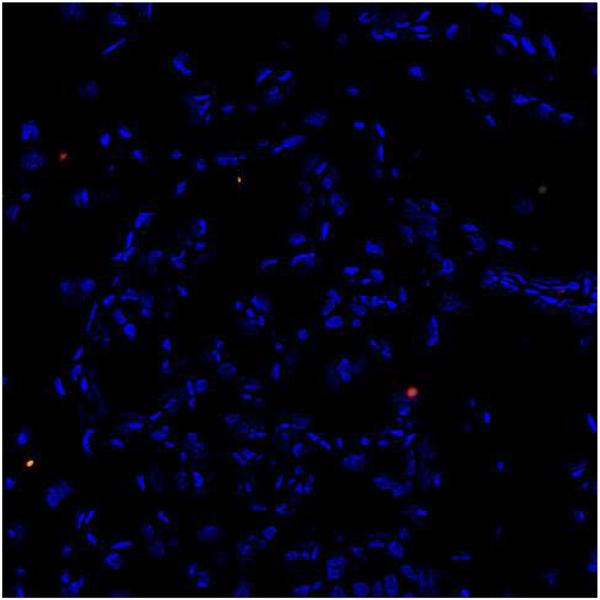

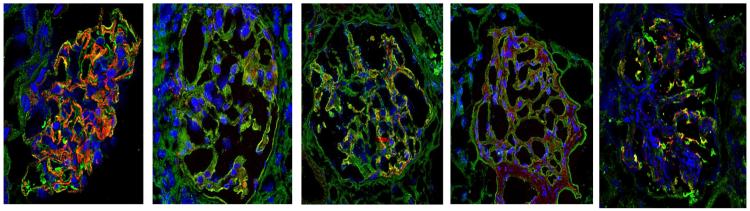

A negative control is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Glomerular CD80 staining (200×): Negative control (Patient 1). Tissue was treated as described in “Methods” except for the omission of the primary antibody. No CD80 staining was observed in the glomeruli or interstitium.

Results

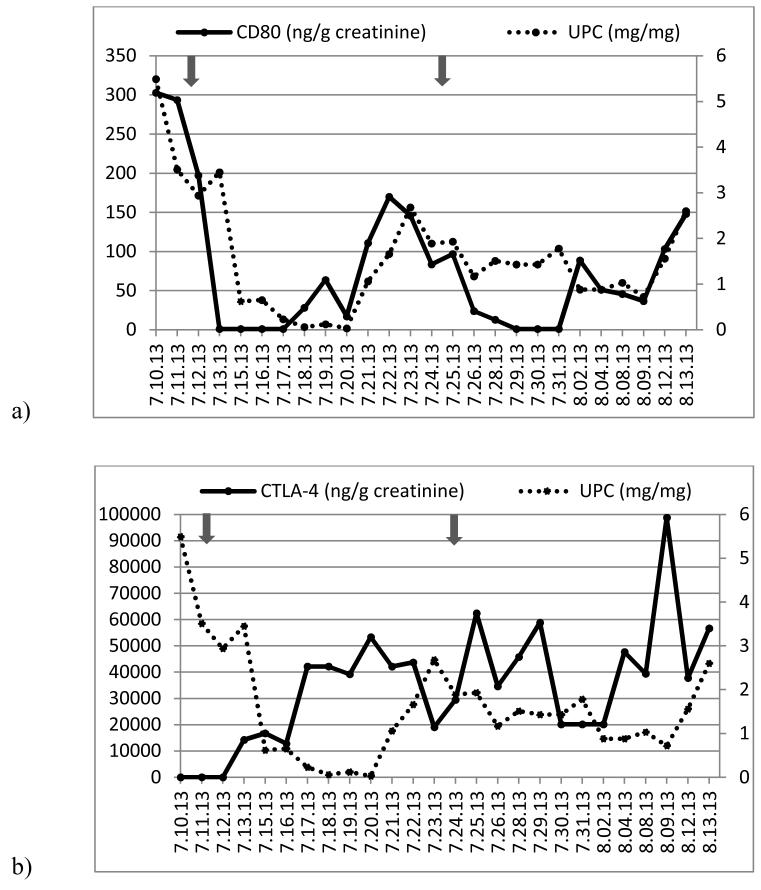

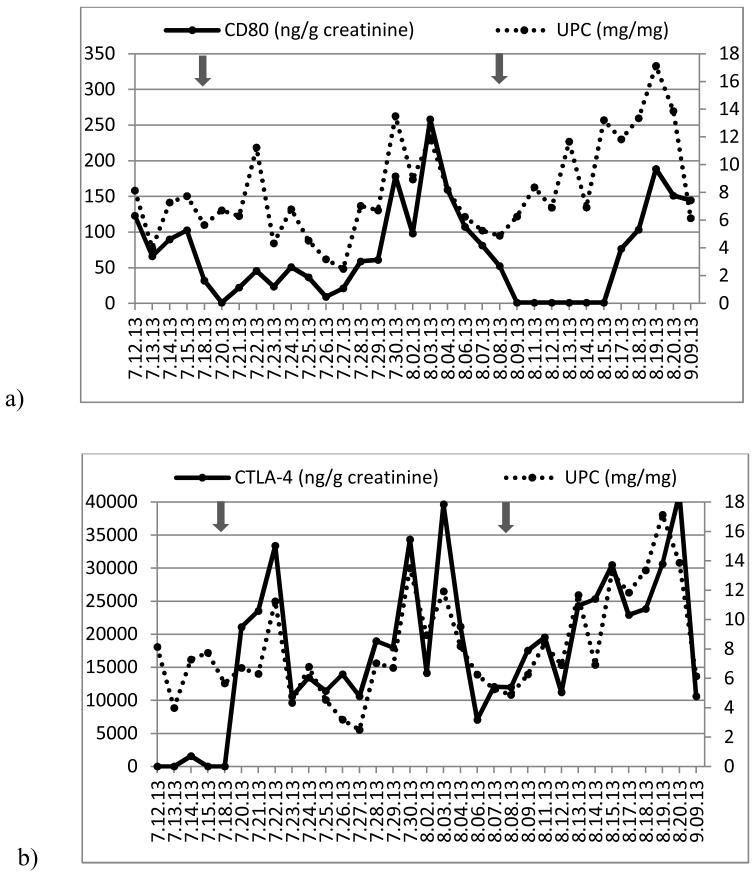

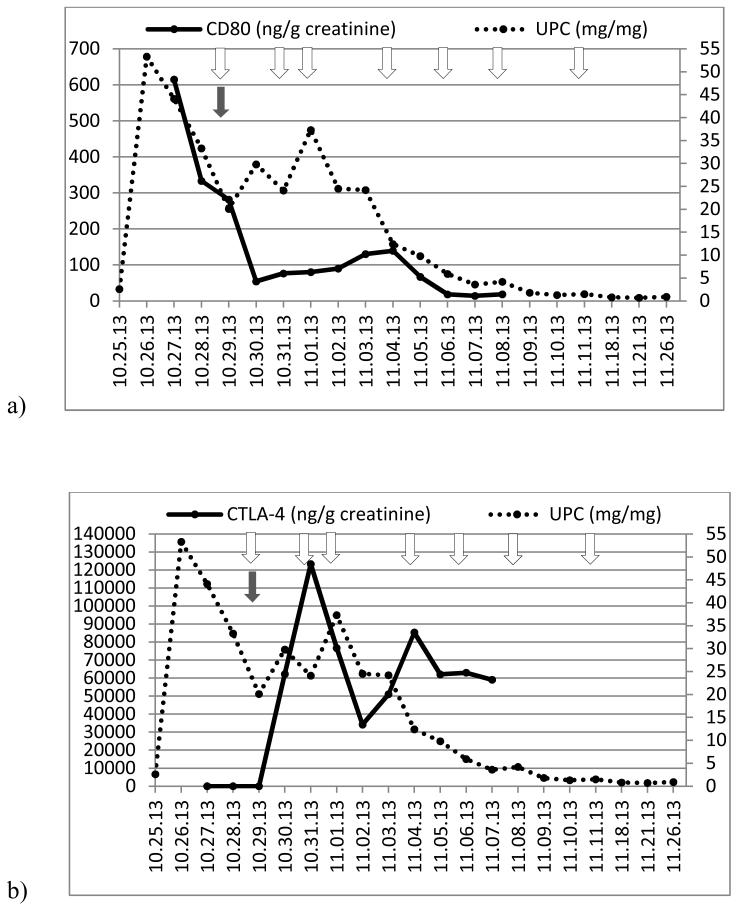

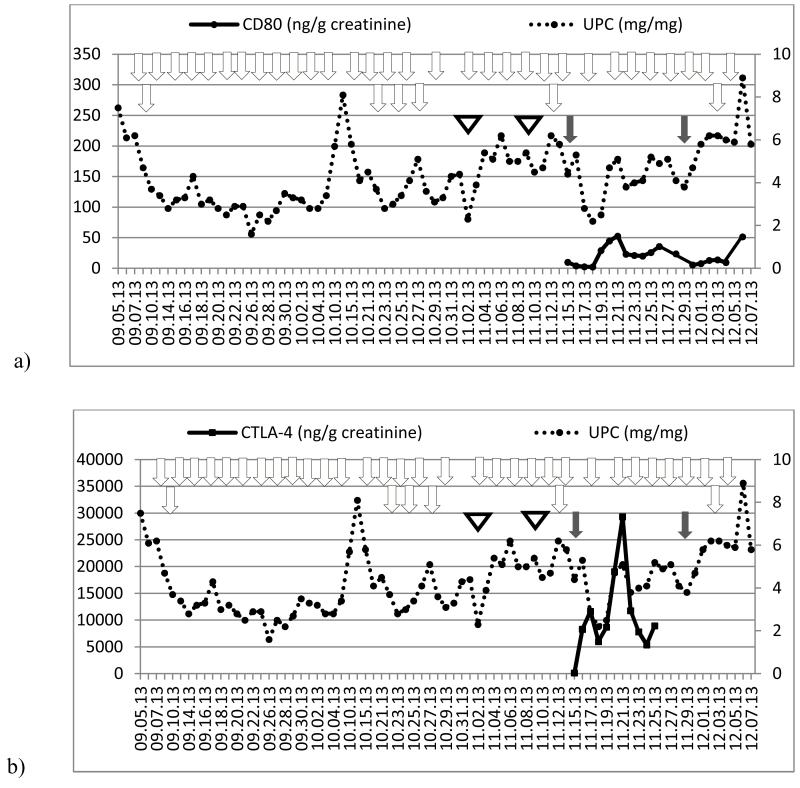

Demographics, immunosuppressive therapy, renal histology and laboratory tests are shown in Table 1. Serial measurements of urine protein to creatinine ratio, urinary CD80 and urinary CTLA-4 excretion of patients 1 to 5 are represented in Figures 2 to 6, respectively.

Table 1. Demographics, immunosuppressive therapy, renal histology and laboratory tests.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender/Race | 2 y/Male/White | 13y/Female/White | 8 y/Male/White | 21 y/Male/white | 46 y/Female/Black |

| Native kidney disease |

MCD | Primary FSGS | Primary FSGS | Primary FSGS | Primary FSGS |

| Age at time of transplant |

8 y | 21 y | 44 y | ||

| Type of graft | Living-related-donor | Deceased-donor | Deceased-donor | ||

| Induction therapy | Thymoglobulin | Thymoglobulin | Thymoglobulin | ||

| IS at the time of anti-CD80 therapy |

FK 0.1 mg/kg/day; prednisone 0.9 mg/kg/day |

FK 0.03 mg/kg/day; MMF 1300 mg/m2/day; prednisone 0.04 mg/kg/day |

FK 0.07 mg/kg/day; Cyclophosphamide 2 mg/kg/day; prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day |

FK 0.1 mg/kg/day; MMF 436 mg/m2; prednisone 0.07 mg/kg/day |

FK 5 mg/4 mg; Myfortic 360 mg 4 times/day; prednisone 10 mg/day |

| Time to recurrence after transplant |

2 days | 1 day | 9 days | ||

| Index biopsy | Minimal mesangial expansion. Extensive PE. |

FSGS on light microscopy, mild IFTA. PE. |

Tubules show minimal atrophy and flattened epithelium. PE. |

Mild peritubular capillary staining for C4d. Prominent PE. |

Diffuse PE. |

| CD80 expression in kidney biopsy (CD80: green; Synaptopodin: red; DAPI: blue)∫ |

|

||||

| UPC and serum creatinine (mg/dl) at the time of anti- CD80 therapy |

2.9 / 0.18 | 5.6 / 0.26 | 33.3 / 0.51 | 4.4 / 2.5 | 4.9/4.1 |

| Number of PP after FSGS recurrence and before anti-CD80 therapy |

1 | 28 | 16 | ||

| Rituximab* | No | No | No | 2 doses prior to Abatacept |

4 doses prior to Belatacept |

| Anti- CD80therapy∫∫ |

Abatacept, 2 doses | Abatacept, 2 doses | Abatacept, 1 dose | Abatacept, 2 doses | Belatacept, 16 doses |

Y year-old; MCD Minimal change disease; FSGS focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; IS Immunosuppression; FK Tacrolimus; MMF mycophenolate mofetil; PE podocyte effacement; IFTA Interstitial fibrosis tubular atrophy; UPC urine protein-to-creatinine ratio; PP plasmapheresis;

Note the strong synaptopodin staining (red) which is in line with an otherwise healthy glomerulus in minimal change disease (patient 1). In all FSGS patients there was a weak staining for synaptopodin.

375 mg/m2/dose;

Abatacept: 10 mg/kg/dose, Belatacept: 5 mg/kg/dose.

Figure 2.

(a) Time course of urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPC, right axis) and urinary CD80 concentration (left axis) and (b) UPC (right axis) and urinary CTLA-4 concentration (left axis) in a child with relapsing minimal change disease (Patient 1). Arrows show when abatacept was administered.

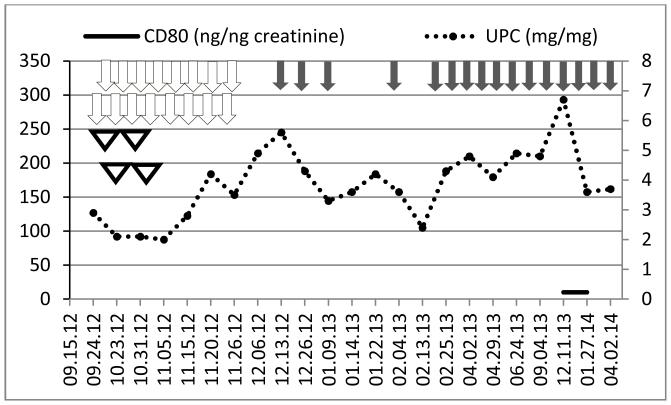

Figure 6.

Time course of urine protein/creatinine ratio (UPC, right axis) and urinary CD80 concentration (left axis) in a patient with recurrent FSGS after transplantation (patient 5). Grey arrows show when belatacept was administered. White arrows represent when plasmapheresis were performed. White triangles represent rituximab infusion.

Patient 1 (Minimal Change Disease)

He presented with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome at the age of 2 years. Subsequently, he suffered two relapses within five months. The first relapse occurred within 2 weeks after completion of prednisone tapering and the second one during prednisone tapering, a pattern consistent with steroid dependence. A kidney biopsy confirmed MCD as the underlying pathology. At this time tacrolimus was added to his therapy. However, he experienced repeat relapses triggered by upper respiratory infections. After discussion with his family, the decision to give abatacept was made. Prednisone was tapered from 30 to 15 mg/day three days prior to abatacept and then from 15 to 6 mg/day three days after. The administration of abatacept was associated with a dramatic fall in urinary CD80 excretion to an undetectable range within 24 hours. This finding was followed by a drop in the urinary protein/creatinine ratio within 72 hours after abatacept, reaching a nadir of 0.03 eight days later (Figure 2). Unfortunately, the remission was short and eleven days after abatacept administration, the urinary protein/creatinine ratio had risen to 2.68 and the urinary CD80 excretion to 146 (ng/g creatinine). Two days later (day 13), prednisone was tapered to 3 mg/day, tacrolimus discontinued, and a second dose of abatacept was given. Urinary CD80 excretion normalized within 24 hours and the urinary protein/creatinine ratio decreased to 0.72 fifteen days after abatacept infusion, but, once again, proteinuria and urinary CD80 excretion increased two days later, although at a lower level than observed previous to the second abatacept infusion.

Patient 2 (Primary FSGS)

Patient 2 received abatacept during relapse at a time when urinary CD80 excretion was within the normal range despite the presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria and mild anasarca. Abatacept was not associated with any improvement in proteinuria (Figure 3). Urinary CD80 excretion rose to 258 ng/g creatinine 16 days after abatacept therapy but normalized 4 days later with no changes in immunosuppression. Since the patient remained in relapse, a second dose of abatacept was given. At that time, urinary CD80 was again within normal range and became undetectable within 24 hours after abatacept. However, the urinary protein/creatinine ratio remained unchanged in the nephrotic range.

Figure 3.

(a) Time course of urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPC, right axis) and urinary CD80 concentration (left axis) and (b) UPC (right axis) and urinary CTLA-4 concentration (left axis) in a child with primary FSGS (Patient 2). Arrows show when abatacept was administered.

Patient 3 (Recurrent FSGS)

Patient 3 received abatacept because of recurrence of FSGS after kidney transplantation. Urinary CD80 excretion was elevated (614 ng/g creatinine) immediately after surgery and subsequently decreased to 281 ng/g creatinine prior to the abatacept infusion and plasmapheresis on day 6 post-surgery (Figure 4). The urine protein/creatinine ratio remained elevated during the next six days after abatacept, despite a marked fall in urinary CD80 excretion to the normal range (54 ng/g creatinine). The patient achieved partial remission eleven days after initiating plasmapheresis, abatacept and cyclophosphamide therapy.

Figure 4.

(a) Time course of urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPC, right axis) and urinary CD80 concentration (left axis) and (b) UPC (right axis) and urinary CTLA-4 concentration (left axis) in a child with recurrent FSGS after transplantation (Patient 3). Grey arrows show when abatacept was administered and white arrows represent when plasmapheresis were performed.

Patient 4 (Recurrent FSGS)

Patient 4 experienced FSGS recurrence immediately after kidney transplantation. Nephrotic syndrome did not respond to plasmapheresis and rituximab. Given the persistence of proteinuria, abatacept was administered despite urinary CD80 excretion being within normal range (9.8 g/ng creatinine) at the time of abatacept administration and for the following 3 weeks (Figure 5). During the same period of time, proteinuria remained within the nephrotic range. A second dose of abatacept was given without any improvement in proteinuria.

Figure 5.

(a) Time course of urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPC, right axis) and urinary CD80 concentration (left axis) and (b) UPC (right axis) and urinary CTLA-4 concentration (left axis) in a patient with recurrent FSGS after transplantation (Patient 4). Grey arrows show when abatacept was administered. White arrows represent when plasmapheresis were performed. White triangles represent rituximab infusion.

Patient 5 (Recurrent FSGS)

Patient 5 experienced FSGS recurrence 9 days post deceased-donor kidney transplantation. She had nephrotic range proteinuria and her index biopsy showed diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and marked staining of CD80. After 16 plasmapheresis sessions and 4 doses of rituximab she continued to have proteinuria within the nephrotic range. She was initiated on repeat belatacept infusion (16 doses). This therapy however, did not result in any improvement in the proteinuria despite of the presence of normal urinary CD80 levels (Figure 6).

Discussion

The present study suggests that the underlying mechanism leading to proteinuria may differ in MCD and FSGS. Thus, the relationship of CD80/CTLA-4 seems to be crucial in the development of proteinuria in MCD, whereas it does not appear to play a role in FSGS.

Consistent with our previous studies [5,6], the MCD patient (Patient 1) showed high urinary CD80 excretion along with low urinary CTLA-4 excretion at the time of relapse. We hypothesized that MCD might be responsive to CTLA-4 therapy, based on the hypothesis that CTLA-4 could inhibit the increased CD80 podocyte expression seen in these patients. Indeed, in vitro, CTLA4-Ig binds to CD80 on podocytes leading to internalization of the CD80-CTLA4 complex [17]. We therefore administered abatacept (CTLA-4-IgG1), which is a fusion protein that comprises the extracellular domain of human CTLA-4 and an Fc fragment of human IgG1 [18]. The administration of abatacept resulted in a marked rise in urinary CTLA-4 with a dramatic plummeting of urinary CD80 excretion at 24 hours followed by resolution of proteinuria within 7 days. Nevertheless, increasing proteinuria was observed beginning on day 9, associated with increased urinary CD80 urinary levels. A second dose of abatacept resulted in the same findings, with a marked initial reduction in urinary CD80 within 24 hours associated with a progressive fall in urinary protein excretion, again followed by increasing urinary protein excretion a few days later, yet at a lower level than that seen prior to abatacept therapy.

The acute reduction of proteinuria is likely due to the abatacept since: a) proteinuria persisted while the patient was on higher doses of prednisone and tacrolimus, but remitted within hours after abatacept was administered, b) we observed the same pattern of changes in CTLA-4, CD80 and urinary protein excretion after the second abatacept administration, despite the fact that the patient was only receiving 0.2 mg/kg/day prednisone, and c) the reduction in proteinuria was preceded by a marked reduction in urinary CD80 excretion. Our studies do not rule out, however, the possibility that the prednisone with or without tacrolimus may have had a contributory role in the response, especially after the first abatacept infusion.

These observations provide clinical evidence that there is a dysregulation of the CD80-CTLA-4 axis in MCD, as suggested in a recent publication [19]. Indeed, many single nucleotide polymorphisms have been identified for the CTLA-4 gene [20,21]. The +49GG genotype has been associated with decreased expression of CTLA-4 and the frequency of this genotype has been found significantly increased in MCD patients compared to normal controls [20].

The remarkable and dramatic fall in urinary CD80 after abatacept followed by resolution of proteinuria provides evidence that abnormalities in podocyte CD80 may likely play a role in the pathogenesis of MCD. CTLA4-IgG1 may be of clinical significance in those patients with severe steroid dependency and steroid resistance with elevated urinary CD80 excretion. However, this approach must be tempered by the fact that the CTLA4-IgG1 effect lasted only a few days.

In contrast to MCD, the mechanism of proteinuria in FSGS seems unlikely to be CD80-driven. Supporting this statement, we previously reported that urinary CD80 excretion in patients with FSGS was similar to that observed in healthy controls and lower than that seen in MCD patients in relapse [5,6]. This finding has been confirmed by others (Segarra et al, personal communication). In this case series, Patient 3 with recurrent FSGS had elevated levels of urinary CD80 immediately after transplantation in contrast to what has been observed in primary FSGS. However, urinary CD80 excretion fell spontaneously before the administration of abatacept. Urinary CD80 reached a nadir of 54 ng/g creatinine (within the normal range) within 24 hours after abatacept. Despite the presence of normal urinary CD80 excretion, proteinuria remained unchanged for 5 days.

Recently, Chang et al found that cultured podocytes exposed to hypoxia showed increased expression of CD80 and the hypoxia-inducible-factor (HIF), resulting in changes in cytoskeletal rearrangement [22]. In this study, CD80 glomerular expression was up-regulated to a similar magnitude as observed in the LPS model of proteinuria. Thus, one could hypothesize that the increased urinary CD80 observed in Patient 3 may have been the consequence of a non-specific response of the podocyte to ischemia occurring during the transplantation procedure, as opposed to being in response to a circulating factor in FSGS. In agreement, Patients 4 and 5 showed normal excretion of urinary CD80 despite recurrence of FSGS with persistent nephrotic syndrome. Patients 4 and 5 underwent kidney transplantation 10 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, prior to monitoring of urinary CD80 and administration of CTLA4-IgG1. In addition, administration of CTLA4-IgG1 did not result in any change in proteinuria.

Yu et al have recently reported partial or complete remission using abatacept in 4 patients with recurrent FSGS after transplantation and in one patient with primary FSGS [23]. The authors considered this therapy after they found positive CD80 staining in the biopsies of these patients. However, there are some concerns with the interpretation of this study. First, the authors suggest that achievement of the clinical response was due to abatacept. However, previous publications have shown a similar rate and timing of remission in patients with FSGS recurrence who did not receive abatacept, especially when plasmapheresis was part of the therapy (Table 2) [24-26]. Second, the absence of urinary CD80 measurements prior to and after kidney transplantation makes the significance of the CD80 immunostaining immediately after transplantation uncertain. Indeed, we have previously found minimal CD80 segmental glomerular staining in one primary FSGS patient, but her urinary CD80 level (75 ng/g creatinine) was similar to that seen in controls [6]. Furthermore, in the study by Yu et al, the two transplanted patients who had positive CD80 staining underwent biopsy within 2 hours post-reperfusion. It remains possible that the increased CD80 expression observed in the glomeruli might have been the result of hypoxia-induced injury to the podocyte. Finally, the authors included a patient with native FSGS who also had positive CD80 staining in the kidney biopsy. The fact that this patient had a normal GFR after 20 years of the FSGS diagnosis highly suggests MCD as the underlying disease rather than FSGS. In response to the Yu et al paper [23], Alachkar et al [27] presented data of five patients with biopsy-proven FSGS after transplantation who did not have a response to plasmapheresis and rituximab and who subsequently received CD80 blockers, ie abatacept, or the even stronger CD80 blocking agent belatacept. The patients did not show any therapeutic responses, despite positive podocyte CD80 expression in their respective kidney biopsy specimens. In another response to the Yu et al paper [23], Benigni et al [28] found cross-reactivity of goat-derived anti-CD80 with immune complexes and possibly with proteins in the GBM in the nephrotic state, further enhancing the need for measuring CD80 derived in urine by ELISA.

Table 2.

Complete remission in FSGS recurrence after transplantation according to therapy

| Author | Age (years) |

IS during recurrence* |

Total sessions of Plasmapheresis (PP) |

Maximum proteinuria during recurrence |

Time to complete remission‡ (CR) expressed in days: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu [23] | 28 y.o. F | FK, MMF, STD - Abatacept × 1 time RTX perioperative |

PP × 5 times | UPC 4.5 | No CR after 13 days of receiving Abatacept and PP |

| 19 y.o. F | FK, MMF, STD - Abatacept × 1 time RTX perioperative |

PP × 9 times | UPC 20-25 (over 10 at recurrence) |

~21-35 days after PP and ~13-27 days after Abatacept |

|

| 14 y.o. M | FK, MMF, STD - Abatacept × 2 times RTX perioperative |

PP × 7 times | UPC 79 | No CR after ~47 days of PP and ~42 days of 1st dose of Abatacept |

|

| 7 y.o. M | FK, MMF, STD - Abatacept × 2 times RTX perioperative |

PP × 3 times | UPC 40 | ~34 days after PP and ~31 days after 1st dose batacept |

|

| 6.5 y.o. F | 350 mg/kg/day | 16 | |||

| Cochat [24] |

13.3 y.o.F | CsA+CP+STD | PP × 17 times (10 within 2 weeks, then 1 PP/week for 2 months) |

1112 mg/kg/day | 12 |

| 15.8 y.o.F | 119 mg/kg/day | 24 | |||

| 17.5 y.o.F | FK, MMF, STD | PP × 5 times | UPC 3 | 8 | |

| 16.6y.o.M | FK, MMF, STD | PP × 13 times | UPC 300 (30 at recurrence) |

27 | |

| Pradhan [25] |

20.8 y.o.F | FK, MMF, STD | PP × 9 times | UPC 7-8 (4.4 at recurrence) |

17 |

| 8.6 y.o. M | FK, MMF, STD | PP × 5 times | UPC 1.9 at recurrence |

5 | |

| At recurrence: | |||||

| 4 g/day | 18 | ||||

| PP × 25 times in 9 patients |

5.4 g/day | 24 | |||

| 7.1 g/day | 28 | ||||

| Canaud [26] |

N=10 adults (8 M,2 F) |

CsA+STD | 7.9 g/day | 29 | |

| PP × 39 times in one patient |

5.6 g/day | 18 | |||

| 7.7 g/day | 20 | ||||

| 22 g/day | 10 | ||||

| 8.7 g/day | 23 | ||||

| 40 g/day | 33 | ||||

| 12 g/day | 26 | ||||

| Mean±SD 1 |

20.4±8.5 | 19.8±7.6 | |||

| Median/ Range1 |

25/5-39 | 20/5-33 |

IS immunosuppression; F female; M male; CsA cyclosporine A; CP cyclophosphamide; STD steroids; MMF mofetil mycophenolate; RTX rituximab; UPC urinary protein to creatinine ratio.

Recurrence: Cochat: proteinuria>50mg/kg/day associated to hypoproteinaemia (<50 g/L) and edema; Pradhan: UPC >1 following transplantation; Canaud: proteinuria >3 g/day without evidence of acute rejection, glomerulitis or allograft glomerulopathy on the biopsy.

Complete remission: Pradhan: UPC<0.5; Canaud: proteinuria < 0.3 g/day. Yu: Normal UPC < 0.15.

In summary, this small case series suggests differences in clinical responses to CTLA4-IgG1 in subjects with MCD and recurrent FSGS. The rapid though transient resolution of proteinuria with urinary CD80 excretion in the subject with MCD is consistent with the mechanism of proteinuria being mediated by a dysregulation of the CD80-CTLA-4 axis. The transient nature of the defect makes the administration of CTLA4-IgG1 impractical to treat these patients. Other modalities controlling CD80 excess production need to be considered. In contrast, our studies and previous studies [27] suggest that the response of recurrent FSGS to CTLA4-IgG1 is poor, and suggests that this disease is not mediated by dysregulated expression of CD80. Although CD80 glomerular expression in post-transplant FSGS may be increased immediately after surgery, this may be due to hypoxia, and the increased urinary CD80 excretion is transitory and does not appear to be modulated by CTLA-4 Ig therapy.

Our results and those of a previous study [27] show no benefit in using CD80-blockade in 9 patients with FSGS, and thus stand in sharp contrast to those results observed by Yu et al, who analyzed 5 patients [23]. Before the use of anti-CD80 therapy becomes a popular consideration in patients with primary FSGS, we recommend well designed control studies to resolve this issue of target engagement, effectiveness and safety of CD80 blockade using abatacept or belatacept.

Acknowledgments

Support:

This study was supported by NIH R01DK080764 to E.H.G. and R.J.J. and in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health DK073495 and DK089394 to R.J.J. J.R. is supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (DK073495, DK089394 and DK101350).

Financial Disclosures:

Jochen Reiser has pending or issued patents in the area of novel therapeutics for renal diseases. He stands to gain royalties from their future commercialization.

References

- 1.Habib R, Kleinknecht C. The primary nephrotic syndrome in childhood: Classification and clinicopathologic study of 406 cases. Pathol Annu. 1971;6:417–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The primary nephrotic syndrome in children Identification of patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome from initial response to prednisone. J Pediatr. 1981;98:561–564. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80760-3. A report of the International Study of kidney Disease in Children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison AM, Cameron SJ, Grünfeld JP. Textbook of Clinical Nephrology. 3rd edn. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 439–469. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. A proposed taxonomy for the podocytopathies: a reassessment of the primary nephrotic diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:529–542. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04121206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garin EH, Diaz LN, Mu W, Wasserfall C, Araya C, Segal M, Johnson RJ. Urinary CD80 excretion increases in idiopathic minimal-change disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:260–266. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garin EH, Mu W, Arthur JM, Rivard CJ, Araya CE, Shimada M, Johnson RJ. Urinary CD80 is elevated in minimal change disease but not in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2010;78:296–302. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiser J, von Gersdorff G, Loos M, Oh J, Asanuma K, Giardino L, Rastaldi MP, Calvaresi N, Watanabe H, Schwarz K, Faul C, Kretzler M, Davidson A, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, Sharpe AH, Kreidberg JA, Mundel P. Induction of B7-1 in podocytes is associated with nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1390–1397. doi: 10.1172/JCI20402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savin VJ, Sharma R, Sharma M, McCarthy ET, Swan SK, Ellis E, Lovell H, Warady B, Gunwar S, Chonko AM, Artero M, Vincenti F. Circulating factor associated with increased glomerular permeability to albumin in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:878–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savin VJ, McCarthy ET, Sharma R, Reddy S, Dong J, Hess S, Kopp J. Cardiotrophin-like cytokine-1: Candidate for the focal glomerulosclerosis permeability factor [abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:59A. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei C, Möller CC, Altintas MM, Li J, Schwarz K, Zacchigna S, Xie L, Henger A, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Cowan P, Kretzler M, Parrilla R, Bendayan M, Gupta V, Nikolic B, Kalluri R, Carmeliet P, Mundel P, Reiser J. Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med. 2008;14:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, Fornoni A, Goes N, Sageshima J, Maiguel D, Karumanchi SA, Yap HK, Saleem M, Zhang Q, Nikolic B, Chaudhuri A, Daftarian P, Salido E, Torres A, Salifu M, Sarwal MM, Schaefer F, Morath C, Schwenger V, Zeier M, Gupta V, Roth D, Rastaldi MP, Burke G, Ruiz P, Reiser J. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:952–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei C, Trachtman H, Li J, Dong C, Friedman AL, Gassman JJ, McMahan JL, Radeva M, Heil KM, Trautmann A, Anarat A, Emre S, Ghiggeri GM, Ozaltin F, Haffner D, Gipson DS, Kaskel F, Fischer DC, Schaefer F, Reiser J, PodoNet and FSGS CT Study Consortia Circulating suPAR in two cohorts of primary FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:2051–2059. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishimoto T, Shimada M, Gabriela G, Kosugi T, Sato W, Lee PY, Lanaspa MA, Rivard C, Maruyama S, Garin EH, Johnson RJ. Toll-like receptor 3 ligand, polyIC, induces proteinuria and glomerular CD80, and increases urinary CD80 in mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1439–1446. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimada M, Araya C, Rivard C, Ishimoto T, Johnson RJ, Garin EH. Minimal Change Disease: A “Two hit” podocyte immune disorder? Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:645–649. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primary nephrotic syndrome in children: clinical significance of histopathologic variants of minimal change and of diffuse mesangial hypercellularity. Kidney Int. 1981;20:765–771. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.209. A Report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oaks MK, Hallet KM. Cutting edge: A soluble form of CTLA-4 in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. J Immunol. 2000;164:5015–5018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiorina P, Vergani A, Bassi R, Niewczas MA, Altintas MM, Pezzolesi MG, D’Addio F, Chin M, Tezza S, Ben Nasr M, Mattinzoli D, Ikehata M, Corradi D, Schumacher V, Buvall L, Yu CC, Chang JM, La Rosa S, Finzi G, Solini A, Vincenti F, Rastaldi MP, Reiser J, Krolewski AS, Mundel PH, Sayegh MH. Role of podocyte B7-1 in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1415–1429. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cara-Fuentes G, Wasserfall CH, Wang H, Johnson RJ, Garin EH. Minimal change disease: a dysregulation of the podocyte CD80-CTLA-4 axis? Pediatr Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2874-8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2874-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spink C, Stege G, Tenbrock K, Harendza S. The CTLA-4 +49GG genotype is associated with susceptibility for nephrotic kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2800–2805. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohl K, Spink C, Wagner N, Zahn K, Wagner N, Eggermann T, Kemper MJ, Querfeld U, Hoppe B, Harendza S, Tenbrock K. CTLA4 polymorphism in Minimal Change Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A case-control study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:1074–1075. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang JM, Hwang DY, Chen SC, Kuo MC, Hung CC, Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC. B7-1 expression regulates the hypoxia-driven cytoskeleton rearrangement in glomerular podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F127–136. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00108.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu CC, Fornoni A, Weins A, Hakroush S, Maiguel D, Sageshima J, Chen L, Ciancio G, Faridi MH, Behr D, Campbell KN, Chang JM, Chen HC, Oh J, Faul C, Arnaout MA, Fiorina P, Gupta V, Greka A, Burke GW, 3rd, Mundel P. Abatacept in B7-1-positive proteinuric kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2416–2423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cochat P, Kassir A, Colon S, Glastre C, Tourniaire B, Parchoux B, Martin X, David L. Recurrent nephrotic syndrome after transplantation: early treatment with plasmapheresis and cyclophosphamide. Pediatr Nephrol. 1993;7:50–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00861567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradhan M, Petro J, Palmer J, Meyers K, Baluarte HJ. Early use of plasmapheresis for recurrent post-transplant FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:934–938. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canaud G, Zuber J, Sberro R, Royale V, Anglicheau D, Snanoudj R, Gaha K, Thervet E, Lefrère F, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Noël LH, Méjean A, Legendre Ch, Martinez F. Intensive and prolonged treatment of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis recurrence in adult kidney transplant recipients: a pilot study. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1081–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alachkar N, Carter-Monroe N, Reiser J. Abatacept in B7-1-positive proteinuric kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1263–1264. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benigni A, Gagliardini E, Remuzzi G. Abatacept in B7-1-positive proteinuric kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1261–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]