Abstract

Here we describe the successful synthesis of cyclic ADP-4-thioribose (cADPtR, 3), designed as a stable mimic of cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR, 1), a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger, in which the key N1-β-thioribosyladenosine structure was stereoselectively constructed by condensation between the imidazole nucleoside derivative 8 and the 4-thioribosylamine 7 via equilibrium in 7 between the α-anomer (7α) and the β-anomer (7β) during the reaction course. cADPtR is, unlike cADPR, chemically and biologically stable, while it effectively mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ like cADPR in various biological systems, such as sea urchin homogenate, NG108-15 neuronal cells, and Jurkat T-lymphocytes. Thus, cADPtR is a stable equivalent of cADPR, which can be useful as a biological tool for investigating cADPR-mediated Ca2+-mobilizing pathways.

Introduction

Cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR, 1, Figure 1), a metabolite of NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), was originally isolated from sea urchin by Lee and co-workers.1 cADPR mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in various mammalian cells, such as, pancreatic β-cells, smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, T-lymphocytes, and cerebellar neurons, and therefore, cADPR is now recognized as a general mediator of intracellular Ca2+ signaling.2

Figure 1.

cADPR (1), cADPcR (2), cADPtR (3) and cIDPR (4).

Analogs of cADPR have been extensively designed and synthesized, since they are potentially useful for investigating the mechanism of cADPR-mediated Ca2+release.3–6 cADPR analogs are also expected to be lead structures for the development of potential drug candidates, due to the important physiological roles of cADPR.2 cADPR analogs have been synthesized predominantly by enzymatic and chemo-enzymatic methods using ADP-ribosyl cyclase-catalyzed cyclization under mild conditions.3 The analogs obtained by these methods, however, are limited due to the substrate-specificity of the ADP-ribosyl cyclase.6

In recent years, methods for the chemical synthesis of cADPR analogs have been studied to develop useful cADPR analogs.4–6 Construction of the characteristic pyrophosphate-containing 18-membered ring structure is the key to the synthesis of cADPR and its analogs, and we have developed an efficient method for forming the ring using S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrates, which can be effectively activated by Ag+ or I2.5b,c

cADPR is readily hydrolyzed at the unstable N1-ribosyl linkage to produce ADP-ribose (ADPR), even in neutral aqueous solution.7 This is due to the fact that cADPR is in a zwitterionic form positively charged around the N1-C6-N6 moiety (pKa = 8.3), making the molecule unstable, where the charged adenine moiety attached to the anomeric carbon of the N1-linked ribose is able to be an efficient leaving group. Under physiological conditions, cADPR is also hydrolyzed at the same N1-ribosyl linkage by cADPR hydrolase to give the inactive ADPR.7

We previously designed and synthesized cyclic ADP-carbocyclic-ribose (cADPcR, 2) as a stable mimic of cADPR, in which the oxygen atom in the N1-ribose ring of cADPR is replaced by a methylene group. cADPcR is both chemically and biologically stable, and effectively mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in sea urchin eggs.5c Although cADPcR is more potent than cADPR in neuronal cells,5g it is almost inactive in T cells, whereas natural cADPR effectively mobilizes Ca2 in both neuronal cells and T cells.5d.f

Although intensive studies of the signaling pathway that uses cADPR are still needed because of its biological importance, the biological as well as chemical instability of cADPR limits further studies of its physiological role. Therefore, stable analogs of cADPR exhibiting Ca2+-mobilizing activity in various cells including T cells are required. Thus, we newly designed and synthesized a 4-thioribose-containing analog of cADPR, i.e., cyclic ADP-4-thioribose (cADPtR, 3), in which the N1-ribose of cADPR is replaced by a 4-thioribose. Evaluations in several biological systems revealed that cADPtR is a stable equivalent of cADPR, which mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ not only in sea urchin eggs and neuronal cells, but also in T cells. Here we report the detailed results of these studies on cADPtR.

Results and Discussion

Design of cADPtR

cADPR is in an equilibrium between the N6-protonated amino-form and the N6-deprotonated imino-form, as shown in Figure 2.8 One difference between cADPR and cADPcR is their pKa values for protonation at the N6-position. The pKa of cADPcR (8.9)5d is somewhat higher than that of cADPR (8.3),8b which might affect its interaction with target proteins. Under physiological conditions, cADPR is in a mixture of the protonated amino form and the deprotonated imino form, where most of cADPcR should be present in the amino-form due to its relatively higher pKa. If cADPR binds to the target protein in T cells in the imino-form, activity of cADPcR would be decreased. In recent years, cADPR analogs with a hypoxanthine base instead of an adenine base, such as cyclic IDP-ribose (cIDPR, 4, Figure 1), were synthesized, and these hypoxanthine-type analogs also mobilized Ca2+ in T cells, while they were almost inactive in other biological sytems.3g,4b–d These findings support the idea of an active imino-form of cADPR in T cells, because the C6=O6 moiety might work as a bioisostere of the plane C6=N6 moiety of the imino-form of cADPR, due to their analogous unsaturated π-electronic structural features.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium between the N6-protonated amino-form and the N6-deprotonated imino-form in cADPR and cADPcR.

Another difference between cADPR and cADPcR might be their three-dimensional structures. In nucleosides, conformation around the glycoside linkage is one of the determinants of their biological activities, and they generally prefer a conformation that avoids steric repulsion between the nucleobase and sugar moieties.9 Therefore, in cADPR and its analogs, the most stable conformation can be the one with minimal steric repulsion between the adenine moiety and both of the N1- and N9-ribose moieties. It should be noted that, in cADPcR, the hydrogens on the tetrahedral sp3-C6”, particularly the H6”β, which is absent in cADPR, are rather sterically repulsive to the adenine H2 (Figure 3). Accordingly, the stable conformation of cADPcR would differ from that of cADPR due to the steric effects.5h

Figure 3.

Possible steric repulsion between the H2 and the H6”β.

Taking these considerations into account, we newly designed cADPtR, a 4-thioribose analog of cADPR. 4’-Thionucleosides are recognized as useful bioisosteres of the natural nucleosides, which are extensively used in studies of medicinal chemistry and chemicalbiology.10 The 4-thioribose in 4’-thionucleosides does not only effectively mimics the ribose of nucleosides, but also the N-4-thioriobyl linkage is more stable than the corresponding N-ribosyl linkage against both chemical and enzymatic hydrolysis.11 In addition, the pKa value of cADPtR is expected to be similar to that of cADPR due to the electron-withdrawing property of sulfur atom. This type of pKa adjustment of biologically active compounds by replacing a methylene with a sulfur has been reported previously.12 Furthermore, the conformation of cADPtR, particularly spatial positioning of the N1-thioribose and adenine moieties, would be similar to that of cADPR, because both sulfur and oxygen have a similar sp3 configuration bearing two non-bonding electron pairs. Thus, we expected that cADPtR might be a stable cADPR equivalent that is active in various cells including T cells.

Synthetic Plan

The retrosynthetic scheme for the target cADPtR (3) is shown in Figure 4. For the synthesis of cADPtR, construction of the 18-membered pyrophosphate structure is an important step. The structure was likely to be constructed using the intramolecular condensation reaction with an S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrate that we developed5b,c, which has been effectively used in the synthesis of a variety of cADPR analogs.4 Thus, treatment of the S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrates 5 having the N1-4-thioribosyladenosine structure with AgNO3/MS3A as a promoter5b,c would form the desired cyclization product, and subsequent deprotection would furnish the target cADPtR. The S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrates 5 would be obtained from the N1-β-thioribosyl adenosine derivative 6β, which we planned to construct by condensation between the 4-thioribosylamine 7 and a known imidazole nucleoside derivative 813 readily prepared from inosine. The 4-thioribosylamine 7 was expected to be prepared from the 1-deoxy-4-thioribose derivative 9, obtained by a known method.14

Figure 4.

Retrosynthetic analysis of the target cADPtR (3).

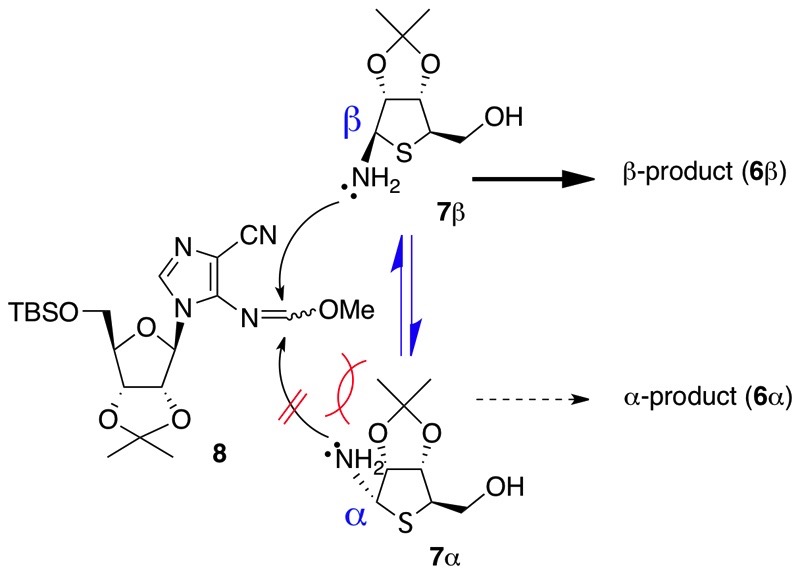

In this synthetic plan, we first had to achieve stereoselective construction of the N1-β-thioribosyladenosine structure. Although no 4-thioribse derivatives having an anomeric amino function such as 7 have been reported to date, 4-thioribosylamine 7 is likely to be present as an anomeric mixture, due to the electron-donating property of the hemiaminal ether nitrogen attaching at the anomeric position. We speculated that if the 4-thioribosylamine derivative 7 is indeed in equilibrium between the α-anomer (7α) and the β-anomer (7β), stereoselective construction of the N1-β-thioribosyladenosine structure might be achieved. In the 4-thioribosylamine 7, the α-face would be rather sterically more hindered than the β-face due to its rigid 5,5-cis ring system. Thus, as shown in Figure 5, in the condensation reaction, the β-anomer 7β might preferentially react with the imidazole nucleoside 8, while the α-anomer 7α might not react due to the steric hindrance by the adjacent isopropylidene moiety. Thus, we expected that, in the reaction course, the relatively less reactive α-anomer would not undergo the condensation, but rather would be effectively converted into the more reactive β-anomer via the equilibrium to result in accumulation of the desired β-condensation product 6β.

Figure 5.

Hypothesis for the stereoselective formation of the desired β-product 7β via the α/β equilibrium.

Synthesis

The 4-thioribosylamine 7 was prepared from the known 1-deoxy-4-thioribose derivative 9,14 as shown in Scheme 1. While several procedures for synthesizing 4-thioribose derivatives have been reported,10 we selected the procedure recently developed by Jeong and co-workers,14 which is effective for large scale preparation of the 4-thio-1-deoxyribose derivative 9 having the desired 2,3-O-isopropylidene protecting group. Oxidation of 9 with m-CPBA and subsequent heating of the resulting sulfoxide product in Ac2O to initiate the Pummerer rearrangement afforded the 1-acetoxy product 11 as an anomeric mixture (α/β = 1:5). When the anomeric mixture 11 was treated with TMSN3 and SnCl4 in CH2Cl2, the β-azide 12 was obtained stereoselectively in high yield, probably due to the steric demand of the reaction intermediate. Reduction of the azido group of 12 by catalytic hydrogenation, followed by removal of the O-acetyl group by heating it in MeOH gave the 4-thioribosylamine 7, which appeared to be an anomeric mixture (α/β = 1:2) as we expected.

Scheme 1.

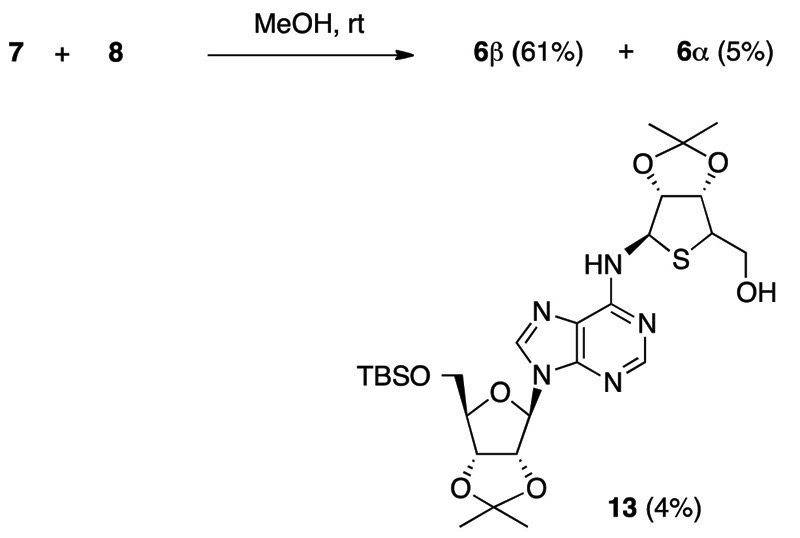

We next investigated the key condensation between the 4-thioribosylanine 7 (α/β = 1:2) and the imidazole nucleoside 8 under various conditions. Under basic reaction conditions, i.e., K2CO3/MeOH which was previously used to construct the N1-carbocyclic-ribosyladenine structures,5c the desired β-condensation product 6b was actually obtained stereoselectively in 50% yield. Under the conditions, however, the N6-(4-thioribosy) product 13 via a Dimroth rearrangement was also obtained in 28% yield. As a result, we found that when 7 was treated with 8 (2.1 eq) in MeOH at room temperature without any bases, the β-product 6b was obtained in 61% yield concomitant with 5% of the α-product 6a, where the 4-thioribosylamine 7 was recovered in 17% yield. Thus, the desired β-product 6b was successfully obtained in 73% conversion yield from the 4-thioribosylamine (α/β = 1:2) via the α/β-equilibrium, as we hypothesized. In the reaction conditions, the N6-thioribosyl product 13 (4%) was also obtained.

The N1-substituted structures of 6a and 6b was confirmed based on their HMBC spectra, in which correlation between the H2 of the adenine and the C1” of the 4-thioribose moiety was observed. The α- and β-stereochemistries of 6a and 6b were confirmed by NOE data (Figure S1).

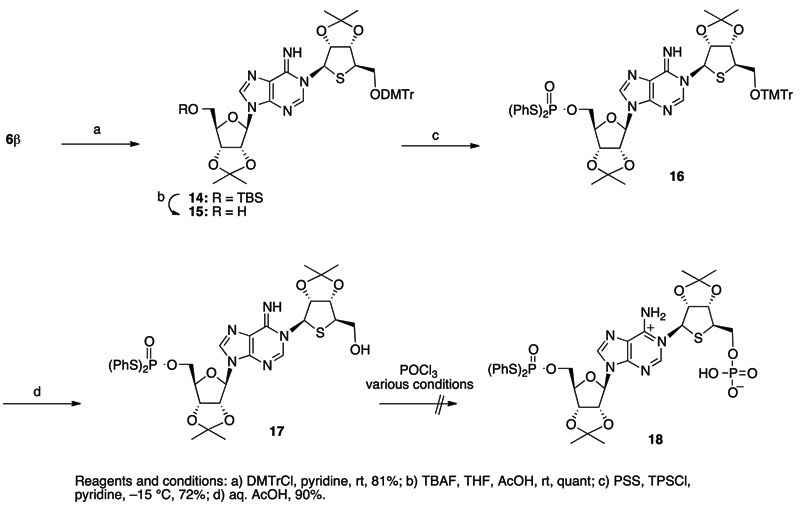

Conversion of the N1-β-thioribosyl product 6b into the S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrate 5 was next investigated (Scheme 3). The 5”-hydroxy group of 6b was protected with a dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) group, and then the 5’-O-TBS group of the product 14 was removed with TBAF to give 15. Treatment of 15 with an S,S’-diphenylphosphorodithioate (PSS)/2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (TPSCl)/pyridine system,15 followed by removal of the 5”-O-DMTr group of the product 16 with aqueous AcOH gave the 5’-bis-S-(phenyl)phosphorothioate 17.

Scheme 3.

We next examined phosphorylation of the 5”-hydroxyl of 17. However, treatment of 17 under the usual conditions of Yoshikawa’s phosphorylation procedure with POCl3/(EtO)3PO,16 which was effective in the previous synthesis of cADPcR and its analogs, gave none of the desired phosphorylation product 18.

Difficulties in the phosphorylation of the 4-thioribose moiety could be assumed to occur, at least partially, because phosphorylation of the 5’-primary hydroxyl of 4’-thioribnucleoside derivatives is rather difficult compared to the cases with usual ribonucleosides.17 Walker and co-workers reported that phosphorylation of 4’-thiothymidine by Yoshikawa’s procedure did not give the desired corresponding 5’-O-phosphate product. They suggested that elimination of the dichlorophosphate moiety would occur in an intermediate A due to effective neighboring group participation by the nucleophilic ring sulfur to result in reproducing the starting material 4’-thiothymidine, via a thionium intermediate B and its subsequent hydrolysis, as shown in Scheme 4-a.17a

Scheme 4.

We thought that a zwitterionic phosphorylating reagent 19 (Scheme 4-b), reported by Asseline and Thuong,18 might be effective for the phosphorylation of 17, because in the phosphorylation intermediate C, the leaving ability of the phosphate moiety would be decreased due to the negatively charged oxygen. Thus, when 17 was treated with 19 in pyridine at -30 °C and then the reaction was quenched with triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) buffer, a compound likely to be the desired phosphorylated 18 was detected as a main peak by HPLC analysis. The product, without purification, was further treated with H3PO2 and Et3N in pyridine to remove the phenylthio group19 affording the phosphorylation product 5 after purification by ion-exchange chromatography (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

With the S-phenyl phosphorothioate 5 in hand, we next investigated the intramolecular cyclization reaction. When a solution of 5 in pyridine was slowly added to a mixture of a large excess of AgNO3 and Et3N in the presence of MS3A in pyridine at room temperature,5b,c the desired cyclization product 19 was obtained in 76% yield. Finally, removal of the isopropylidene groups of 19 with aqueous HCO2H produced the target cADPtR (3) in 49% yield (Scheme 5).

Stability of cADPtR

cADPtR (3) appeared to be rather chemically stable, since the final acidic removal of the isopropylidene groups of 20 was successful to produce cADPtR, as described above (Scheme 5).

The biological stability of cADPtR was investigated with a rat brain microsomal extract that contains cADPR degradation enzymes.7 We first treated cADPR with the extract at 37 °C to result in its rapid degradation. As expected, under the same conditions, cADPtR was almost completely resistant to degradation in the extract. After 120 min treatment, approximately 90% of cADPR disappeared, whereas most of cADPtR remained intact (Figure S2), indicating that cADPtR is stable under physiological conditions.

pKa value of cADPtR

The pKa value of cADPtR (3) was determined using a previously reported method.8b This method is based on the pH-dependent UV spectral change between 285 nm and 300 nm area of cADPR or its analogs, due to the protonation and proton-dissociation at the N6 position of the adenine ring. As a result, the pKa of cADPtR was determined to be 8.0, which was similar to that of cADPR (pKa = 8.3)8b and about 1 unit lower than that of cADPcR (pKa = 8.9).5d

Ca2+-mobilizing Activity in Sea Urchin Egg Homogenate

We tested the Ca2+-mobilizing ability of cADPtR (3) as well as cADPR (1) and cADPcR (2) by fluorometrically monitoring Ca2+ with H. pulcherrimus sea urchin egg homogenate (Figure 6).20 cADPR released Ca2+ from the homogenate in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 value of 214 nM, and cADPcR showed more potent activity (EC50 = 54 nM) than cADPR, where the maximal Ca2+-mobilizing activity of cADPcR was almost equal to that of cADPR. These results are consistent with previous reports that cADPcR potently activates Ca2+ release in sea urchin eggs of A. crassispina or L. pictus.5c,h As shown in Figure 6, cADPtR exhibited highly potent Ca2+-mobilizing ability (EC50 = 36 nM), which was about 7-fold more potent than the natural second messenger cADPR and even more potent than cADPcR.

Figure 6.

Concentration-dependent Ca2+-mobilizing activity of cADPR, cADPcR, and cADPtR in sea urchin egg homogenate. The Ca2+-mobilizing activity of each compound is expressed as the percent change in ratio of fura-2 fluorescence (F340/F380) relative to that of 10 µM cADPR. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 to 6 experiments.

Ca2+-mobilizing Activity in Neuronal Cells

The effect of cADPtR (3) on cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization in NG108-15 neuronal cells was studied in permeabilized conditions using digitonin as the detergent.21 We first verified that extracellular application of digitonin itself did not cause an increase in [Ca2+]i in the conditions in which the plasma membrane was permeabilized with 250 nM of digitonin for nearly 5 min (Figure 7-b and -c). We also confirmed that application of 100 mM cADPR (1), used as a positive control, caused a gradual and sustained Ca2+ release in the digitonin-permeabilized conditions, which allowed nucleotides to enter into the cytoplasm (Figure 8-c). When cADPR was applied extracellularly to intact NG108-15 cells, no increase in [Ca2+]i was detected (data not shown). Figure 7-a shows a representative field of cells with [Ca2+]i changes induced by the application of cADPtR with the plasma cell membrane was permeabilized with 250 nM digitonin for 5 min. Figure 8-c shows the mean time-course of [Ca2+]i changes induced by cADPtR. Application of 100 μM cADPtR induced persistent increases in [Ca2+]i: the mean [Ca2+]i level measured 4 min after application of cADPtR was 116 ± 2.3% of the resting (pre-permeabilization) level (mean ± SEM; n=6). The amplitude evoked by cADPtR was equivalent to or significantly greater than that induced by cADPR: the mean [Ca2+]i level measured 4 min after application of cADPR was 107 ± 2.8% of the resting level (n=10). A similar Ca2+-mobilizing pattern was observed in cADPcR-applied cells: the mean [Ca2+]i level measured 4 min after application of cADPcR was 115 ± 3.1% of the resting level (n=10).

Figure 7.

Effects of cADPtR on [Ca2+]i increases in permeabilized NG108-15 cells. a), b) Cells were permeabilized by the addition of 250 nM digitonin to the bath solution. cADPtR (final concentration, 100 μM) (a) or an equal amount of buffer (b) was added together with digitonin as indicated by the arrows. Representative fields are displayed for each condition. Changes in [Ca2+]i are shown as pseudocolor images, and colors reflecting fluorescence intensities are indicated to the right together with arbitrary units. c) Time-course of [Ca2+]i changes in Oregon Green-loaded NG 108-15 cells. At about 25 s after the beginning of each trace, cell membranes were permeabilized with buffers containing 250 nM digitonin with 100 μM cADPtR (magenta), cADPcR (blue), cADPR (green), or without nucleotide as control (black). Symbols indicate changes of [Ca2+]i levels for 5 min, represented by the fluorescence intensity at each time (x) divided by resting intensity at time 0 (i.e. Fx/F0). For calculations, cells with mean fluorescence intensity of 90 to 130 at time 0 were selected. *, Values in cells treated with cADPtR or cADPcR were significantly higher than those in control cells at p <0.05. ♦, Values in cells treated with cADPtR were significantly higher than those in cells treated with cADPR at p <0.05. d) The graph shows concentration-dependent activity of cADPtR (magenta), cADPcR (blue) and cADPR (green) in NG108-15 cells. Symbols indicate changes of [Ca2+]i levels at 280 s after membrane permeabilization, represented by fluorescence intensity at each time divided by the resting state at time 0 (i.e. Fx/F0). Each symbol is mean ± SEM of 5 to 10 experiments. *, values significantly different from a drug-free control value (a gray circle) (P < 0.05). ♦, Values in cells treated with cADPtR were significantly higher than those in cells with cADPR at p <0.05.

Figure 8.

Effect of of cADPR (1) and cADPtR (3) on Ca2+ signaling in permeabilized Jurkat T cells. After addition of fura-2/free acid (1.5 mM) and charging of the intracellular Ca2+-pools by the addition of ATP (1 mM) and an ATP-regenerating system consisting of creatine phosphate (10 mM) and creatine kinase (20 units/ml), the indicated concentrations of cADPR or cADP-4”-thio-ribose were added as indicated. a) Representative tracings. b) Data presented as mean±SEM (n = 2 to 8).

These results in NG108-15 neuronal cells indicate that cADPtR has potent Ca2+-mobilizing activity, similar to cADPcR. Both cADPtR and cADPcR have increased efficacy as compared with cADPR, which may be due to their increased metabolic stability.

Ca2+-mobilizing Activity in T cells

The Ca2+-mobilizing effect of cADPtR (3) was evaluated using saponin-permeabilized Jurkat T cells as reported previously.22 Both cADPtR and cADPR (1) evoked rapid Ca2+ release upon addition to the permeabilized cell suspension indicating similar mechanisms of Ca2+ release (Figure 8-a). Though cADPR was somewhat more potent at 100 mM, cADPR and cADPtR had very similar concentration-response curves (Figure 8-b) indicating that cADPtR binds to the cADPR receptor protein with similar affinity. Our previous work revealed that replacing the northern ribose of cADPR with the carbocyclic moiety (cADPcR) shifted its Ca2+ mobilizing activity to much higher concentrations.5d In contrast, the new analog cADPtR was almost as active as cADPR. A difference of cADPcR and analog cADPtR are their pKa values, amounting to 8.9 and 8.0, respectively. Taking the pKa value of cADPR and the indistinguishable biological activity between cIDPR (4) and cADPR3g,4b–d in T cells into account, the relatively high biological activity of cADPtR might be in favour of the imino form of cADPR being the active form of the natural second messenger in T cells.

Conformational Analysis

The three-dimensional structures of biologically active compounds in aqueous solution is very important from the viewpoint of the bioactive conformation. Our study shows that cADPR (1), cADPcR (2), and cADPtR (3) have different activities in sea urchin eggs, neuronal cells and T cells, respectively. To investigate the biological difference based on their conformations, structures of them were constructed by molecular dynamics calculations with a simulated annealing method based on the NOE constraints of the intramolecular proton pairs measured in D2O (for details, see Fig 13 ). The structures obtained by the calculations based on their observed NOE in the NOESY spectra are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 13.

Important correlations in NOESY spectra of a) cADPR (1), b) cADPcR (2), c) cADPtR (3), used for the calculations.

Figure 9.

Structures of cADPR (a), cADPcR (b), cADPtR (c) by molecular dynamics calculations with simulated annealing method using the NOE data in D2O. Adenine H2 (white), O4” in cADPR (red), C6” in cADPcR (green) and S4” in cADPtR (yellow) are shown in sphere.

To analyze the structural differences in more detail, these structures were superimposed as shown in Figure 10-a, which shows that the cADPtR structure (red) resembles that of natural cADPR (blue). The cADPcR structure (green), however, is not similar to those of the other two compounds, in which the relative special arrangement of the N1-thioribose ring and the adenine ring is clearly different from those of the other two compounds, as we expected. Thus, the distances between the 4”S between the adenine H2 of cADPtR (3.6 Å) is significantly longer than the corresponding distances of cADPR (2.3 Å) and cADPtR (2.5 Å), probably due to the steric repulsion between the H6”β with the adenine H2 in cADPcR.

Figure 10.

Superimposed displays of the structures of cADPR and its analogs. Only heavy atoms are shown. a) Three caluculated structures are superimposed: cADPR(blue), cADPcR(green), and cADPtR(red). b) Four structures were superimposed: The crystal structure of cADPR (white), the calculated structures of cADPR(blue), cADPcR(green), and cADPtR(red).

To confirm the validity of the obtained structures, we used the cADPR structure solved by X-ray crystallographic analysis.2j,8c Thus, the X-ray structure of cADPR (white) is superimposed into the three structures as shown in Figure 10-b. This crystal structure resembles the calculated cADPR and cADPtR structures, which suggests our structure determination by the molecular dynamics calculations was done relevantly.

Discussion

cAPDtR (3), which was designed as a stable mimic of cADPR (1), was successfully synthesized. In its synthesis, the key N1-β-thioribosyladenosine structure was effectively constructed by stereoselective condensation between the imidazole nucleoside derivative 8 and the 4-thioribosylamine 7 via equilibrium between the α-anomer (7α) and the β-anomer (7β). Also, the strategy using a S-phenyl phosphorothioate-type substrate in the intramolecular condensation reaction forming the 18-membered pyrophosphate linkage of cADPR-related compounds is demonstrated to be useful in the present case.

Although cADPR is rapidly hydrolyzed by cADPR hydrolase to give ADP-ribose under physiological conditions, cADPtR was shown to be biologically stable. Based on the X-ray crystallographic analysis of the complex of CD38 having cADPR hydrolase activity with nicotinamide guanine dinucleotide (GDP+), Lee and Hao presented the reaction mechanism of enzymatic cADPR hydrolysis via an oxocarbenium intermediate, which is stabilized by the hydroxy group of Ser196 of the enzyme catalytic site.23 When an oxocarbenium ion, which is often an intermediate in glycosidic bond cleavage, interacts with an electronically negative nucleophilic atom such as oxygen (the hydroxyl oxygen of Ser196 in the case of CD38), it can be effectively stabilized by the adjacent ring oxygen of the sugars due to n–p* hyperconjugation between the nonbonding orbital on the ring oxygen and the vacant p-orbital of anomeric carbon, that is known as the anomeric effect.24 This stereoelectronic effect would promote enzymatic and also chemical hydrolysis of cADPR at the N1-linkage. On the other hand, the sulfur of thio-sugars, including thioribose, would not so effectively stabilize the corresponding thio-carbenium intermediates, because the hyperconjugation ability of sulfur is remarkably weaker than that of oxygen,25 which can be reason why cADPtR is more stable than cADPR

On the other hand, the electron-withdrawing effect of sulfur due to its electronically negative property effectively lowered the pKa of cADPtR, and accordingly, its pKa is similar to that of cADPR. Under physiological pH, the population of the deprotonated imino form and the protonated amino form in cADPtR would be analogous that in cADPR. Therefore, the pKa value of cADPtR may be favorable to exhibit its biological effects, similarly to natural messenger cADPR.

A difference of cADPcR and analog cADPtR are their pKa values, amounting to 8.9 and 8.0, respectively. Taking the pKa value of cADPR and the indistinguishable biological activity between cIDPR (4) and cADPR3g,4b–d in T cells into account, the relatively high biological activity of cADPtR might be in favour of the imino form of cADPR being the active form of the natural second messenger in T cells.

Our conformational analysis revealed that cADPtR has its three-dimensional structure analogous to cADPR due the similar sp3 configuration of oxygen and sulfur bearing two non-bonding electron pairs in the N1-ribose or -thioribose ring, in which steric repulsion between the three rings (adenine, N9-ribose, and N1-ribose) seems to be minimal. Therefore, the structural and electrostatic features of cADPtR analogous to cADPR make it as biologically active as cADPR in various systems including T-cells, although the target proteins of cADPR in these systems is considered to be different.5f.

Conclusion

We have successfully synthesized cADPtR (3) and demonstrated that it is stable and functions as cADPR (1) in various biological systems, i.e., sea urchin egg homogenate, neuronal cells and T cells. Because of the characteristic stability and high potency of cADPtR, it, as a stable equivalent of cADPR, can be useful as an effective tool for identifying target proteins and for investigating cADPR-mediated signaling pathways.26

Experimental

Chemical shifts are reported in ppm downfield from Me4Si (1H), MeCN (13C) or H3PO4 (31P). All of the 1H NMR assignments described were in agreement with COSY spectra. Thin-layer chromatography was done on Merck coated plate 60F254. Silica gel chromatography was done on Merck silica gel 5715. Reactions were carried out under an argon atmosphere.

1,4-Dideoxy-1,4-episulfinyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-d-ribitol (10)

To a solution of 22 (1.90 g, 10.0 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL) was added slowly a solution of mCPBA (3.18g, 12.0 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (60 mL) at -78 °C, and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 20 min. To the mixture was added aqueous Na2S2O3, and the resulting mixture was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O, and the organic layer was washed with aqueous saturated NaHCO3 and brine, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/AcOEt = 3/1 then 1/1) to give 10 (1.88 g, 91%, white amorphous solid): 1H-NMR of one isomer (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.33 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.47 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.29 (1H, dd, J = 14.3, 6.3 Hz, H-1), 3.42 (1H, ddd, J = 5.7, 5.7, 2.9 Hz, H-4), 3.45 (1H, dd, J = 14.3, 5.7 Hz, H-1) 4.10 (1H, dd, J = 12.6, 5.7 Hz, H-5), 4.34 (1H, dd, J = 12.6, 2.9 Hz, H-5), 4.80 (1H, br, OH), 5.10 (1H, dd, J = 5.7, 3.4 Hz, H-3), 5.20 (1H, ddd, J = 6.3, 5.7, 3.4 Hz, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.61, 27.12, 57.06, 57.06, 58.11, 65.63, 79.76, 82.22, 112.11; HR-MS (EI) calcd for C8H14O4S2 206. 06128 (M+), found 206. 06169

1,5-O-Diacetyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-4-thio-d-ribose (11)

A solution of 10 (135 mg, 0.44 mmol) in Ac2O (3 mL) was heated at 100 °C for 28 h, and then evaporated. The residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O, and the organic layer was washed with aqueous saturated NaHCO3 and brine. The aqueous layers were combined and extracted with CHCl3. The organic layers were combined, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/AcOEt = 6/1, 3/1 then 1/1) to give 11 (93 mg, 64%, J = 11.5, 5.7 Hz, H-5), 4.89-4.91 (2H, m, H-2, H-3), 6.04 (1H, s, H-1), for α-anomer, δ 1.36 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.54 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 2.10 (3H, s, Ac), 2.15 (3H, s, Ac), 3.90 (1H, m, H-4), 4.19 (1H, dd, J = 11.5, 6.3 Hz, H-5), 4.35 ( J = 11.5, 5.7 Hz, H-5), 4.89-4.91 (2H, m, H-2, H-3), 6.04 (1H, s, H-1), for α-anomer, δ 1.36 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.54 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 2.10 (3H, s, Ac), 2.15 (3H, s, Ac), 3.90 (1H, m, H-4), 4.19 (1H, dd, J = 11.5, 6.3 Hz, H-5), 4.35 (1H, dd, J = 11.5, 6.3 Hz, H-5), 4.67 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 4.0 Hz, H-3), 4.88 (1H, m, H-2), 6.09 (1H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, H-1) 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 20.85, 21.21, 24.61, 26.38, 53.85, 65.71, 85.13, 87.17, 88.54, 111.29, 169.16, 170.49; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C12H18NaO6S 313.0722 [(M+Na)+], found 313.0717.

5-O-Acetyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-4-thio-β-d-ribofuranosylazide (12)

To a solution of 11 (2.26 g, 7.78 mmol) and TMSN3 (3.09 mL, 23.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added a solution of SnCl4 (223 mL, 1.91 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) at 0 °C, and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 5 min. To the mixture was added aqueous saturated NaHCO3, and the resulting white precipitate was filtered off with Celite. The filtrate was washed with aqueous saturated NaHCO3 and brine, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/AcOEt = 20/1) to give 12 (1.84g, 86%, yellow oil): 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.31 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.50 (3H, s, isopropylidene- CH3), 2.11 (3H, s, Ac), 3.63 (1H, dd, J = 10.0, 5.4 Hz, H-4), 4.12 (1H, dd, J = 11.3, 10.0 Hz, H-5), 4.27 (1H, dd, J = 11.3, 5.4 Hz, H-5), 4.64 (1H, d, J = 5.4 Hz, H-3), 4.86 (1H, d, J = 5.4 Hz, H-2), 5.18 (1H, s, H-1); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 20.73, 24.51, 26.26, 54.29, 65.21, 76.13, 85.59 89.06, 111.23, 170.40; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C10H15N3NaO4S 296.0681 [(M+H)+], found 296.0695.

2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-d-ribofuranosylamine (7)

A mixture of 12 (1.25 g, 4.57 mmol) and Pd/C (10%, 630 mg) in MeOH (45 mL) was stirred under atmospheric pressure of H2 at room temperature for 1 h, and then the catalysts were filtered off with Celite. The filtrate was evaporated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (NH-silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 6/1, 2/1 then 1/3) to give 7 (1.09 g, quant., α/β = 1/2, brown oil): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.30 (2H, s), 1.36 (1H, s), 1.52, (2H, s), 1.57 (1H, s), 1.83 (2H, brs), 3.58 (2/3H, dd, J = 7.7, 5.4 Hz), 3.73 (1/3H, ddd, J = 6.3, 5.9 Hz), 4.32 (2/3H, dd, J = 11.7, 7.7 Hz), 4.43 (2/31H, dd, J = 11.7, 5.4 Hz), 4.49 (1/3H, dd, J = 11.3, 5.9 Hz), 4.60-4.66 (2/3H, m), 4.71-4.74 (1H, m), 4.79 (2/3H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, b-H-1), 4.92 (1/3H, dd, J = 4.5 Hz), 5.04 (2/3H, d, J = 4.5 Hz); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ -5.64, -5.51, 18.23, 24.36, 25.27, 25.80, 26.50, 27.22, 57.20, 63.68, 64.31, 64.63, 81.06, 85.99, 86.45, 87.57, 91.20, 91.65, 95.13, 110.33, 113.74, 117.26, 132.20, 148.52, 151.04; HR-MS (EI) calcd for C8H15NO3S 205.0773 (M+), found 205.0773.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-5’-O-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (6β)

A solution of 7 (381 mg, 1.87 mmol) and 8 (1.79g, 4.00 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 10 h, and then evaporated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 1/2, AcOEt , then AcOEt/MeOH = 9/1) to give 6β (700 mg, 61%, white amorphous solid), 6α (59 mg, 5%, white amorphous solid), 14 (30 mg, 4%, yellow amorphous solid). 6β: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl) δ 0.04 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.05 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.86 (9H, s, tert-butyl), 1.35 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.39 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.61 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.63 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.77 (1H, dd, J = 11.4, 4.0, 4.0 Hz, H-5’), 3.83-3.88 (2H, m, H-5’, H-5”), 3.90 (1H, m, H-4”), 4.01 (1H,dd, J = 11.4, 3.7 Hz, H-5”), 4.39 (1H, m, H-4’), 4.88 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 3.4 Hz, H-3’), 4.99 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 1.7 Hz, H-3”), 5.06 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.3 Hz, H-2’), 5.51 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 3.4 Hz, H-2”), 6.00 (1H, d, J = 3.4 Hz, H-1”), 6.02 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1’), 7.85 (1H, s, H-8), 7.88 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ -5.58, -5.47, 18.25 25.25, 25.80, 27.13, 27.92, 55.53, 63.37, 64.75, 74.54, 81.19, 85.23, 85.75, 86.22, 86.95, 91.15, 111.66, 114.09, 123.75, 137.20, 140.30, 146.81, 153.31; UV (MeOH) λmax = 260 nm; LR-MS (FAB, positive) m/z 610 [(M+H)+]; Anal. Calcd for C27H43N5O7SSi: C, 53.18; H, 7.11, N, 11.48. Found C, 52.88; H, 6.95; N, 11.35; NOE irradiated H-2/ observed H-2” (3.8%), irradiated H-1”/ observed H-4” (2.3%), irradiated H-2”/ observed H-2 (4.7%), irradiated H-4”/ observed H-1” (3.2%). 6α: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl) δ 0.05 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.05 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.87 (9H, s, tert-butyl), 1.35 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.39 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.61 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.63 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.56 (1H, d, J = 4.1, .4.1 Hz, H-4”), 3.76 (1H, dd, J = 11.3, 3.6 Hz, H-5’), 3.84-3.88 (2H, m, H-5’, H-5”), 3.93 (1H, dd, J = 10.9, 4.1 Hz, H-5”), 4.39 (1H, ddd, J = 6.3, 3.6, 3.6 Hz, H-4’), 4.90 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.7 Hz, H-3’), 4.95 (1H, d, J = 5.9 Hz, H-3”), 5.01 (1H, dd, J = 5.9, 4.5 Hz, H-2”), 5.09 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.7 Hz, H-2’), 6.05 (1H, d, J = 2.7 Hz, H-1’), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 4.5 Hz, H-1”), 7.83 (1H, s, H-8), 8.42 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ -5.54, -5.44, 18.29, 24.22, 25.33, 25.83, 25.97, 27.16, 54.36, 61.15, 63.34, 65.17, 80.59, 81.19, 85.30, 85.87, 86.99, 91.16, 111.38, 114.09, 122.77, 136.83, 140.88, 147.76, 155.00; UV (MeOH) λmax = 259 nm; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C28H43N5O7SSi 610.2731 (MH+), found 610.2727. NOE irradiated H-2/ observed H-4” (1.0%), irradiated H-1”/ observed H-2” (10.7%), irradiated H-2”/ observed H-1” (8.4%), irradiated H-4”/ observed H-2 (1.7%). 13: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.00 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.01 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.83 (9H, s, tert-butyl), 1.32 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.40 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.59 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.62 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.69 (1H, m, H-4”), 3.73 (1H, dd, J = 11.3, 4.5 Hz, H-5’), 3.83-3.87 (2H, m, H-5’, H-5”), 3.90 (1H, br, OH), 4.07 (1H, dd, J = 10.4, 2.7 Hz, H-5”), 4.39 (1H, m, H-4’), 4.87 (1H, d, J = 5.0 Hz, H-2’), 4.94-4.96 (2H, m, H-3’, H-3”), 5.28 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.3 Hz, H-2’), 6.13 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1’), 6.16 (1H, br, H-1”), 7.49 (1H, d, J = 9.1 Hz, NH), 7.97 (1H, s, H-2), 8.45 (1H, s, H-8); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ -5.64, -5.51, 18.23, 24.36, 25.27, 25.80, 26.50, 27.22, 57.20, 63.68, 64.31, 64.63, 81.06, 85.99, 86.45, 87.57, 91.20, 91.65, 95.13, 110.33, 113.74, 117.26, 132.20, 148.52, 151.04; UV (MeOH) λmax = 273 nm; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C27H44N5O7SSi 610.2731 (MH+), found 610.2741.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-5-O-dimethoxytrityl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-5’-O-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (14)

A solution of 6β (889 mg, 1.46 mmol) and DMTrCl (989 mg, 2.92mmol) in pyridine (5 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After addition of MeOH, the resulting mixture was partitioned between EtOAc and 1 M aqueous HCl, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 6/1, 3/1, 3/2, and 2/3) to give 14 (1.08 g, 81%, white amorphous solid): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.05 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.06 (3H, s, Si-CH3), 0.88 (9H, s, tert-butyl), 1.30 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.38 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.59 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.62 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.40-3.46 (2H, m, H-5”×2), 3.77 (1H, m, H-5’), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.80-3.85 (2H, m, H-4”, H-5’), 4.38 (1H, ddd, J = 5.7, 4.0, 4.0 Hz, H-4’), 4.72 (1H, dd, J = 5.7, 4.0 Hz, H-3”), 4.86 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 5.7 Hz, H-3’), 4.89 (1H, dd, J = 5.7, 2.3 Hz, H-2”), 4.97 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.9 Hz, H-2’) 6.02 (1H, d, J = 2.9 Hz, H-1’), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1”), 6.81-7.47 (13H, m, Ar), 7.82 (1H, s, H-8), 8.12 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ -5.58, -5.47, 18.22, 25.21, 25.28, 25.79, 27.13, 27.35, 54.95, 55.05, 63.30, 64.85, 66.78, 81.06, 84.82, 85.25, 86.53, 86.79, 89.22, 90.86, 112.38, 113.03, 113.05, 114.01, 123.23, 126.66, 127.73, 127.95, 129.92, 129.96, 135.46, 135.60, 136.51, 140.35, 144.47, 145.55, 153.98, 158. 37; LR-MS (FAB, positive) m/z 882 [(M+H)+]; UV (MeOH) λmax = 259 nm; Anal. Calcd for C48H61N5O9SSi: C, 63.20; H, 6.74, N, 7.68. Found C, 63.19; H, 6.91; N, 7.39.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-5-O-dimethoxytrityl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (15)

A solution of 14 (94 mg, 103 mmol), TBAF (1.0 M in THF, 200 mL, 0.20 mmol) and AcOH (6 μL, 1 μmol) in THF (800 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 9 h, and then evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 2/1, /1, 3/2, and 1/3) to give 15 (83 mg, quant., colorless amorphous solid): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.29 (3H, s, isopropylidene), 1.37 (3H, s, isopropylidene), 1.58 (3H, s, isopropylidene), 1.63 (3H, s, isopropylidene), 3.40 (1H, dd, J = 9.7, 6.9 Hz, H-5”), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 9.7, 6.9 Hz, H-5”), 3.72 (1H, dd, J = 12.6, 10.9 Hz, H-5”), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (1H, m, H-4”), 3.86 (1H, d, J = 12.6 Hz, H-5’), 4.47 (1H, m, H-4’), 4.67 (1H, dd, J = 5.7 4.0 Hz, H-3”), 4.84 (1H, dd, J = 5.7, 2.3 Hz, H-2”), 4.99-5.03 (2H, m, H-2’, H-3’), 5.31 (1H, d, J = 10.9 Hz, OH), 5.75 (1H, d, J = 4.6 Hz, H-1’), 6.44 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1”), 6.80-7.42 (13H, m, Ar), 7.57 (1H, br s, NH), 7.63 (1H, s, H-8), 8.14 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.42, 25.48, 27.60, 27.76, 54.98, 55.39, 63.28, 65.05, 67.35, 81.62, 83.90, 84.89, 86.03, 86.90, 89.28, 93.95, 112.90, 113.35, 114.39, 125.04, 127.03, 128.07, 128.26, 130.18, 130.23, 135.74, 135.92, 138.32, 139.63, 144.66, 146.01, 153.86, 158.70; UV (MeOH) λmax = 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C42H48N5O9S 798.3173 [(M+H)+], found 798.3193.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-5-O-dimethoxytrityl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-5’-O-[bis(phenylthio)phosphoryl]-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (16)

To a solution of 15 (845 mg, 1.06 mmol) in pyridine (5 mL) was added a solution of PSS (809 mg, 2.12 mmol) and TPSCl (693 mg, 1.91 mmol) in pyridine (5 mL) at -15 °C, and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 2.5 h. After addition of H2O, the resulting mixture was partitioned between EtOAc and 1 M aqueous HCl, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 3/1, 1/1, 1/2, and 1/3) to give 16 (812 mg, 72%, white amorphous solid): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.25 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.36 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.57 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.61 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.40 (1H, m, H-5’), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 5.7 Hz, H-5’), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (1H, m , H-4”), 4.37-4.39 (2H, m, H-5”×2), 4.44 (1H, m, H-4’), 4.64 (1H, m, H-3”), 4.83 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.3 Hz, H-2”), 4.89 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 3.4 Hz, H-3’), 5.06 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.3 Hz, H-2’), 5.97 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1’), 6.55 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1”), 6.80-7.48 (23H, m, Ar), 7.82 (1H, s, H-8), 8.09 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.32, 27.14, 27.48, 55.09, 55.19, 64.99, 66.14, 66.33, 66.39, 80.89, 84.44, 84.70, 84.79, 86.58, 89.09, 90.62, 112.59, 113.12, 113.15, 123.71, 125.67, 125.71, 125.73, 125.76, 126.79, 127.85, 128.10, 129.42, 129.44, 129.63, 129.66, 129.68, 129.70, 130.03, 130.08, 135.11, 135.16, 135.27, 135.31, 135.58, 135.71, 137.27, 140.28, 144.55, 145.85, 153.96, 158.47; 31P-NMR (202 MHz, CDCl3) d 50.79 (s); UV (MeOH) λmax = 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C54H57N5O10PS3 1062.3005 [(M+H)+], found 1062.2999.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-5’-O-[bis(phenylthio)phosphoryl]-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (17)

A solution of 16 (23 mg, 22 mmol) in aqueous 60% AcOH (2 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, and then evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/AcOEt = 1/1, 1/3, then AcOEt) to give 17 (15 mg, colorless amorphous solid): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.34 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.38 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.60 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.62 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.76-3.83 (3H, m, H-4”, H-5”×2), 4.30 (1H, ddd, J = 11.4, 9.7, 5.2 Hz, H-5’), 4.43 (1H, ddd, J = 6.3, 5.2, 2.9 Hz, H-4’), 4.47 (ddd, 1H, J = 12.6, 9.7, 6.3 Hz, H-5’) , 4.83 (1H, d, J =5.2 Hz, H-3”), 5.04 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.9 Hz, H-3’), 5.09 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 1 .1 Hz, H-2”) 5.28 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 1.7 Hz, H-2’), 5.98 (1H, d, J = 1.7 Hz, H-1’), 6.07 (1H, d, J = 1.1 Hz , H-1”), 7.27-7.54 (10H, m, Ar), 7.63 (1H, s, H-8), 8.55 (1H, s, H-2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) d 24.88, 25.08, 26.87, 27.28, 57.09, 64.26, 66.26, 66.32, 73.96, 81.93, 84.52, 85.65, 85.73, 85.93, 89.68, 91.39, 110.99, 114.10, 123.84, 125.28, 125.34, 125.46, 125.52, 129.27, 129.29, 129.38, 129.40, 129.58, 129.60, 129.73, 129.75, 135.04, 135.09, 135.37, 135.40, 138.01, 140.22, 147.09, 154.09; 31P-NMR (202 MHz, CDCl3) d 52.23 (s); UV (MeOH) λmax = 251, 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, positive) calcd for C33H39N5O8PS3 760.1698 [(M+H)+], found 760.1710.

N1-(2,3-O-Isopropylidene-4-thio-5-O-phospholyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-5’-O-(phenylthiophosphoryl)-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine (5)

A solution of MeOPOCl2 (30 mL, 0.30 mmol) in pyridine (1 mL) was stirred at -15 °C for 15 min. To the solution was added a solution of 17 (75 mg, 0.10 mol) in pyridine (1 mL) , and the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 2h. To the resulting solution was added triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) buffer (0.5 M, pH7.0, 3 mL) then H3PO2 (101 μL, 2.0 mmol) and Et3N (140 μL, 1.0 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 13 h, and then evaporated. The residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O, and the aqueous layer was evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (ODS, 1.2 × 16 cm, 0-37% CH3CN /0.1M TEAA buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0, 400 mL), linear gradient). The excess TEAA included in the residue was removed by column chromatography (ODS, 1.2 × 16 cm, CH3CN/H2O = 1/1). The product was lyophilized to give 5 (37 mg, 512 OD260 unit, 46%) as a triethylammonium salt: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 1.26 (9H, t, J = 7.4 Hz (CH3CH2)3N), 1.40 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.43 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.63 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.69 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.18 (6H, q, J = 7.4 Hz, (CH3CH2)3N), 4.10-4.13 (4H, m, H-4”, H-5’×2, H-5”), 4.70 (1H, m, H-4”), 4.20 (1H, m, H-5’), 4.22 (1H, m, H-5”), 4.32 (1H, m, H-5”), 4.71 (1H, m, H-4’), 4.94 (1H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, H-3’) 5.12-5.15 (2H, m, H-2”, H-3”), 5.42 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.9 Hz, H-3’), 5.39 (1H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, H-2’), 5.95 (1H, s, H-1”), 6.37 (1H, s, H-1’), 7.19-7.33 (5H, m, Ar), 8.41 (1H, s, 8-H), 9.24 (1H, s, 2-H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 8.30, 24.32, 24.35, 25.95, 26.41, 46.71, 54.48, 54.55, 65.90, 65.95, 66.59, 66.62, 75.84, 81.39, 84.11, 86.19, 86.27, 86.52, 89.30, 90.88, 113.51, 114.72, 119.08, 127.91, 129.08, 129.47, 129.51, 132.75, 132.79, 143.02, 145.48, 146.84, 150.53; 31P-NMR (202 MHz, D2O) d 17.54 (s), 0.80 (s); UV (D2O) λmax = 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, negative) calcd for C27H34N5O12P2S2 746.1126 [(M-H)-], found 746.1106.

Cyclic ADP-4-thio-ribose 2’,3’-, 2”,3”-bisacetonide (19)

To a mixture of AgNO3 (36 mg, 0.21 mmol), Et3N (29 ml, 0.21 mmol), and MS 3A (powder, 1.0 g) in pyridine (8 mL), a solution of 5 (9mg, 50 OD260 unit, 4 mmol) in pyridine (8 mL) was added slowly over 15 h, using a syringe-pump, at room temperature under shading. To the mixture was added TEAA buffer (2.0 M, pH 7.0, 2 mL), and the resulting mixture was filtered with Celite and evaporated. The residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O, and the aqueous layer was evaporated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (ODS, 1.2 × 16 cm, 0-35% CH3CN /0.1M TEAA buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0, 400 mL), linear gradient). The excess TEAA included in the residue was removed by column chromatography (ODS, 1.2 × 16 cm, CH3CN/H2O = 1/1). The product was lyophilized to give 19 (6 mg, 36 OD260 unit, 72%) as a triethylammonium salt: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 1.24 (9H, t, J = 7.4 Hz (CH3CH2)3N), 1.41 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.43 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.61 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 1.65 (3H, s, isopropylidene-CH3), 3.17 (6H, q, J = 7.4 Hz, (CH3CH2)3N), 3.91 (1H, m, H-5’), 4.13 (1H, m, H-4”), 4.20 (1H, m, H-5’), 4.22 (1H, m, H-5”), 4.32 (1H, m, H-5”), 4.58 (1H, m, H-4’), 5.07 (1H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, H-3”) 5.13 (1H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, H-2”), 5.42 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 2.9 Hz, H-3’), 5.89 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 1.7 Hz, H-2’), 5.99 (1H, s, H-1”), 6.38 (1H, d, J = 1.7 Hz, H-1’), 8.38 (1H, s, 8-H), 9.59 (1H, s, 2-H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 8.29, 24.39, 24.42, 26.07, 26.26, 46.73, 55.40, 55.49, 64.80, 68.03, 64.83, 68.00, 77.65, 81.36, 83.25, 86.65, 86.73, 87.34, 90.82, 91.45, 113.11, 114.59, 119.58, 144.91, 145.55, 147.20, 150.67; 31P-NMR (202 MHz, D2O) d -10.62 (d, J = 15.5 Hz), d -11.29 (d, J = 15.5 Hz); UV (D2O) λmax = 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, negative) calcd for C21H28N5O12P2S 636.0936 [(M-H)¯], found 636.0947.

Cyclic ADP-4-thio-ribose (3)

A solution of 19 (280 OD260 unit, 25 mmol) in aqueous 60% HCO2H (1 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 40 h and then evaporated. After co-evaporation with H2O, the residue was purified by column chromatography (ODS, 1.2 × 16 cm, TEAA buffer (5 mM, pH 7.0)). The excess TEAA included in the residue was removed by column chromatography (Sephadex LH 20, 2.5 × 20 cm, H2O) to give 3 as a triethylammonium salt, which was converted into a free acid form by passing through columns of Daiaion PK212L (H+ form, 0.7 cm × 5 cm, H2O). The free acid was passed throuh Chelex 100 column (K+ form, 0.7 cm × 6 cm, H2O). The eluent was evapolated and lyophilized to give 3 (138 OD260 unit, 49%) as a potassium salt. 3 (potassium salt): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 3.59 (1H, dd, J = 8.2, 3.2 Hz), 4.08 (1H, m), 4.19 (1H, m), 4.24-4.36 (4H, m), 4.52 (1H, ddd J = 10.4, 8.2, 2.7 Hz), 4.60 (1H, dd, J = 5.4, 2.3 Hz), 5.18 (1H, dd, J = 5.9, 5.4 Hz), 5.87 (2H, m), 7.97 (1H, s), 9.25 (1H, s); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 50.8, 50.9, 63.1, 65.0, 65.0, 70.1, 70.6, 72.6, 73.0, 78.3, 84.7, 84.8, 90.5, 120.0, 145.3, 145.9, 146.9, 150.8; 31P-NMR (162 MHz, D2O) δ -9.15 (d, J = 12.2 Hz), δ -10.20 (d, J = 12.2 Hz); UV (D2O) λmax = 258 nm; HR-MS (FAB, negative) calcd for C15H20N5O12P2S 556.0304 [(M-H)-], found 556.2994. 3 (free acid): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 3.72 (1H, ddd, J = 5.2, 3.4, 1.7 Hz), 4.09 (1H, ddd, J = 10.9, 6.9, 2.9 Hz), 4.25 (1H, ddd, J = 11.5, 5.2, 2.3 Hz), 4.35-4.39 (3H, m), 4.51 (1H, ddd, J = 10.9, 7.4, 4.0 Hz), 4.53 (1H, dd, J = 5.9, 2.9 Hz), 4.71 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 2.3 Hz), 5.22 (1H, dd, J = 6.3, 5.2 Hz), 5.97 (1H, d, J = 2.9 Hz), 6.04 (1H, d, J = 6.3 Hz), 8.38 (1H, s), 9.90 (1H, s).

Stability in Rat Brain Microsomes

Rat brain microsomes were prepared by a procedure according to the previous method (Murayama T.; Ogawa Y.; J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 5079-5084.). cADPR or cADPtR (1.6 OD260unit) was preincubated in 20 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7.1, 160 μL) at 37 °C for 5 min. This was added to the solution of the microsome fraction of rat brain extract (14.9 mg/ mL, 140 μL), and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C. The reaction mixture was sampled (25 μL) at every 30 min afterwards and diluted with water (175 μL), which was frozen in liquid nitrogen to stop the reaction. After the samples were a centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, the supernatants were filtered using centrifugal filter at 12000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, and the resulting filtrates (70 μL) were analyzed by ion exchange HPLC (TSK-GEL DEAE-2SW, 4.6 × 250 mm; 5-35% 1M HCO2NH4/20% MeCN, 20 min; 260 nm). The results are shown in Figure 2.

Biological Evaluations with Sea Urchin Egg Homogenate or T-cells

These bioassays were carried out as reported previously.5f

Biological Evaluations with Neuronal Cultured Cells

NG108-15 neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid cells were cultured as reported previously.21a Oregon Geen-loaded NG108-15 cells were incubated for 2 min in the following calcium-free medium (140 mM K-glutamate, 20 mM PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM Mg-ATP, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 0.01% bovine serum albumin, pH 6.8) at 37°C, and subsequently permeabilized with 250 nM digitonin in the calcium-free medium. cADPR (1-100 µM), cADPcR (1-100 µM), or cADPcR (1-100 µM) were applied together with the digitonin-containing permeabilization buffer to be allowed free passage of these nucleotides into the cytoplasm. Concentrations of [Ca2+]i were determined microspectrofluorometrically using fura-2 in differentiated NG108-15 cells cultured on polylysine-coated glass coverslips. The cells were loaded with fura-2 using 5 μM Oregon Green 488 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N,N-tetraacetate acetoxymethylester (BAPTA-1 AM). Fluorescence was measured at 37°C with excitation wavelengths of 485 nm and emission wavelengths of 538 nm using an Argus 50 Ca2+ microspectrofluorometric system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) and images were collected every 10 s for up to 5 min. The changes in fluorescence intensity of each cell were expanded into an X-t plane, and data were performed in fluorescence intensity at each time (x) divided by resting intensity at time 0, i.e., Fx/F0.21b Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s t test. The criterion for significance in all cases was p<0.05.

Computational Calculations

For structure determination, molecular calculations were carried out by AMBER11 (Case, D. A.; Darden, T.A.; Cheatham, T. E. III; Simmerling, C. L.; Wang, J.; Duke, R. E.; Luo, R.: Walker, R. C. ; Zhang, W. ; Merz, K. M.; Roberts, B. ; Wang, B. ; Hayik, S. ; Roitberg, A. ; Seabra, G.; Kolossvary, I.; Wong, K.F.; Paesani, F.; Vanicek, J.; Wu, X.; Brozell, S. R.; Steinbrecher, T.; Gohlke, H.; Cai, Q.; Ye, X.; Wang, J.; Hsieh, M.-J.; Cui, G.; Roe, D. R.; Mathews, D. H.; Seetin, M. G.; Sagui, C.; Babin, V.; Luchko, T.; Gusarov, S.; Kovalenko, A.; Kollman, P.A. AMBER 11, University of California, San Francisco, 2010).27 cADPR (1), cADPcR (2) and cADPtR (3) were modeled by the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF: Wang, J.; Wolf, R. M.; Caldwell, J. W.; Kollman, P. A.; Case, D. A. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157-1174).28 AM1-BCC charge (Jakalian, A.; Jack, D. B.; Bayly, C. I. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 1623-1641) was used for cADPR and its analogs assigned by Antechamber module29 (Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Kollman, P. A.; Case, D. A. J Mol Graph Model 2006, 25, 247-260) of AMBER11. In the calculations, interatomic distances restricts were determined by the integrated volumes of the NOESY cross-peaks. As cross peaks of cADPR and cADPcR, previously published data (Kudoh, T.; Fukuoka, M.; Ichikawa, S.; Murayama, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Hashii, M.; Higashida, H.; Kunerth, S.; Weber, K.; Guse, A. H.; Potter, B. V.; Matsuda, A.; Shuto, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8846-8855) were used.5f. For generating conformations, we carried out 400 ps simulated annealing molecular dynamics simulations: temperature was decreased from 1000 to 300 K. These simulations were repeated 100 times with different initial velocity for each compound. In calculated conformations, we chose and analyzed the lowest energy conformation.

Scheme 2.

Figure 11.

NOE and HMBC data of 6b and 6a.

Figure 12.

Stability of cADPtR and cADPR in rat brain microsome extract.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (2365904901, S.S) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and by Project Grant 084068 from the Welcome Trust (to B.V.L.P. and A.G.). B.V.L.P is a Welcome Trust Senior Investigator (grant 101010).

References and Notes

- 1.Clapper DL, Walseth TF, Dargie PJ, Lee HC. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9561–9568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Galione A. Science. 1993;259:325–326. doi: 10.1126/science.8380506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee HC. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:1133–1164. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Galione A, Cui Y, Empson R, Iino S, Wilson H, Terrar D. Cell Biochem Biophys. 1998;28:19–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02738307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guse AH. Cell Signal. 1999;11:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Higashida H, Hashii M, Yokoyama S, Hoshi N, Chen XL, Egorova A, Noda M, Zhang JS. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90:283–296. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee HC, editor. Cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP: Structures, Metabolism and Functions. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 2002. [Google Scholar]; (f) Guse AH. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:239–248. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Zhang AY, Li PL. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:407–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Jin D, Liu H-X, Hirai H, Torashima T, Nagao T, Lopatina O, Shnayder NA, Yamada K, Noda M, Seika T, Fujita K, et al. Nature. 2007;446:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature05526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Venturi E, Pitt S, Galfré E, Sitsapesan R. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;3:199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Lee HC. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31633–31640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.349464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For examples: Walseth TF, Lee HC. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1993;1178:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90199-y. Lee HC, Aarhus R, Walseth TF. Science. 1993;261:352–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8392749. Zhang F-J, Sih CJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;5:1701–1706. Ashamu GA, Galione A, Potter BVL. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1995:1359–1360. Wagner GK, Black S, Guse AH, Potter BVL. Chem Commun. 2003:1944–1945. doi: 10.1039/b305660k. Wagner GK, Guse AH, Potter BVL. J Org Chem. 2005;70:4810–4819. doi: 10.1021/jo050085s. Moreau C, Wagner GK, Weber K, Guse AH, Potter BVL. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5162–5176. doi: 10.1021/jm060275a. Moreau C, Kirchberger T, Zhang B, Thomas MP, Weber K, Guse AH, Potter BVL. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1478–1489. doi: 10.1021/jm201127y.

- 4.For examples: Galeone A, Mayol L, Oliviero G, Piccialli G, Varra M. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:363–368. Huang L-J, Zhao Y-Y, Yuan L, Min J-M, Zhang L-H. J Med Chem. 2002;45:5340–52. doi: 10.1021/jm010530l. Gu X, Yang Z, Zhang L, Kunerth S, Fliegert R, Weber K, Guse AH, Zhang L. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5674–5682. doi: 10.1021/jm040092t. Xu J, Yang Z, Dammermann W, Zhang L, Guse AH, Zhang L-H. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5501–5512. doi: 10.1021/jm060320e. Swarbrick JM, Potter BVL. J Org Chem. 2012;77:4191–4197. doi: 10.1021/jo202319f. Yu PL, Zhang ZH, Hao BX, Zhao YJ, Zhang LH, Lee HC, Zhang L, Yue J. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24774–24783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329854.

- 5.(a) Shuto S, Shirato M, Sumita Y, Ueno Y, Matsuda A. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1986–1994. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuoka M, Shuto S, Minakawa N, Ueno Y, Matsuda A. J Org Chem. 2000;65:5238–5248. doi: 10.1021/jo0000877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shuto S, Fukuoka M, Manikowsky M, Ueno T, Nakano T, Kuroda R, Kuroda H, Matsuda A. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8750–8759. doi: 10.1021/ja010756d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Guse AH, Cakir-Kiefer C, Fukuoka M, Shuto S, Weber K, Matsuda A, Mayer GW, Oppenheimer N, Schuber F, Potter BVL. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6744–6751. doi: 10.1021/bi020171b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shuto S, Fukuoka M, Kudoh T, Garnham C, Galione A, Potter BVL, Matsuda A. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4741–4749. doi: 10.1021/jm030227f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kudoh T, Fukuoka M, Ichikawa S, Murayama T, Ogawa Y, Hashii M, Higashida H, Kunerth S, Weber K, Guse AH, Potter BVL, Matsuda A, Shuto S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8846–8855. doi: 10.1021/ja050732x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hashii M, Shuto S, Fukuoka M, Kudoh T, Matsuda A, Higashida H. J Neurochem. 2005;94:316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kudoh T, Murayama T, Hashii M, Higashida H, Sakurai T, Maechling C, Spiess B, Weber K, Guse AH, Potter BVL, Arisawa M, Masuda A, Shuto S. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:9754–9765. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zhang F-J, Gu Q-M, Sih CJ. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:653–664. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shuto S, Matsuda A. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:827–845. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guse AH. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:847–855. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Potter BVL, Walseth TF. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:303–311. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HC, Aarhus R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1164:68–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Lee HC, Walseth TF, Bratt GT, Hayes RN, Clapper DL. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1608–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim H, Jacobson EL, Jacobson MK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:1143–1147. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee HC, Aarhus R, Levitt D. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:143–144. doi: 10.1038/nsb0394-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gu Q-M, Sih CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7481–7486. [Google Scholar]; (e) Wada T, Inageda K, Aritomo K, Tokita K, Nishina H, Takahashi K, Katada T, Sekine M. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1995;14:1301–1341. [Google Scholar]; (f) Graham SM, Pope SC. Nucleosides, Nucleotides, Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:169–183. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Graham SM, Macaya DJ, Sengupta RN, Turner KB. Org Lett. 2004;6:232–236. doi: 10.1021/ol036152r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saenger W. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. Springer; New York, NY: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Reist EJ, Gueffroy DE, Goodman L. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:1964, 5658–5663. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bobek M, Whistler RL. J Med Chem. 1970;13:411–413. doi: 10.1021/jm00297a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dyson MR, Coe PL, Walker RT. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2782–2786. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bellon L, Barascut JL, Maury G, Divira G, Goody R, Imbach JL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1587–1593. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yoshimura Y, Watanabe M, Satoh H, Ashida N, Ijichi K, Sakata S, Machida H, Matsuda A. J Med Chem. 1997;40:2177–2183. doi: 10.1021/jm9701536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Naka T, Minakawa N, Abe H, Kaga D, Matsuda A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7233–7243. [Google Scholar]; (g) Takahashi M, Minakawa N, Matsuda A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1353–1362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Elzagheid MI, Oivanen M, Walker RT, Secrist JA., III Nucleosides, Nucleotides, Nucleic Acids. 1999;18:181–186. [Google Scholar]; (b) Toyohara J, Gogami A, Hayashi A, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1671–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganellin CR, Owen DAA. Agents Actions. 1977;7:93–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01964887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson EJ, Taylor BF, Blackburn GM. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1997:1859–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong LS, Lee HW, Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Shin DH, Lee JA, Gao Z-G, Lu C, Duong HT, Gunaga P, Lee SK, Jin DZ, Chun MW, Moon HW. J Med Chem. 2006;49:273–281. doi: 10.1021/jm050595e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sekine M, Nishiyama S, Kamimura T, Osaki Y, Hata T. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1985;58:850–860. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sekine M, Hata T. Cur Org Chem. 1993;3:25–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshikawa M, Kato T, Takenishi T. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1969;42:3505–3508. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Hancox EL, Walker RT. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1996;15:135–148. [Google Scholar]; (b) Alexandova LA, Semizarov DG, Krayevsky AA, Walker RT. Antivir Chem Chemther. 1996;7:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asseline U, Thuong NT. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1988;7:431–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hata T, Kamimura T, Urakami K, Kohno K, Sekine M, Kumagai I, Shinozaki K, Miura K. Chem Lett. 1987:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiwa M, Murayama T, Ogawa Y. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R727–737. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00519.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Higashida H, Hashii M, Fukuda K, Caulfield MP, Numa S, Brown DA. Proc Biol Sci. 1990;242:68–74. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Amina S, Hashii M, Ma WJ, Yokoyama S, Lopatina O, Liu HX, Islam MS, Higashida H. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Guse AH, Roth E, Emmrich F. Biochem J. 1993;291:447–451. doi: 10.1042/bj2910447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guse AH, Berg I, da Silva CP, Potter BVL, Mayr GW. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8546–8550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schwarzmann N, Kunerth S, Weber K, Mayr GW, Guse AH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50636–50642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Kriksunov IA, Graeff R, Munshi C, Lee HC, Hao Q. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32861–32869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Juaristi E, Cuevas G. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:5019–5087. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thatcher GRJ. The Anomeric Effect and Associated Stereoelectronic Effects. Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 1993. ACS Symposium Series 539. [Google Scholar]; (c) Juaristi E, Cuevas G. The Anomiric Effect. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1995. [Google Scholar]; (d) Thibaudeau C, Chattopadhyaya J. Stereoelectronic Effects in Nucreosides and Nucreotides and their Structural Implications. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salzner U, Schleyer PVR. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10231–10236. [Google Scholar]

- 26.A preliminary accout of this study has been published: Tsuzuki T, Sakaguchi N, Kudoh T, Takano S, Uehara M, Murayama T, Sakurai T, Hashii M, Higashida H, Weber K, Guse AH, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:6633–6637. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302098.

- 27.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, et al. AMBER 11. University of California; San Francisco: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Wang W, Kollman PA, Case DA. J Mol Graph Model. 2006;25:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]