Abstract

Bone density loss in astronauts on long-term space missions is a chief medical concern. Microgravity in space is the major cause of bone density loss (osteopenia), and it is believed that high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation in space exacerbates microgravity-induced bone density loss; however, the mechanism remains unclear. It is known that acidic serine- and aspartate-rich motif (ASARM) as a small peptide released by matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) promotes osteopenia. We previously discovered that MEPE interacted with checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) to protect CHK1 from ionizing radiation promoted degradation. In this study, we addressed whether the CHK1-MEPE pathway activated by radiation contributes to the effects of microgravity on bone density loss. We examined the CHK1, MEPE and secreted MEPE/ASARM levels in irradiated (1 Gy of X-ray) and rotated cultured human osteoblast cells. The results showed that radiation activated CHK1, decreased the levels of CHK1 and MEPE in human osteoblast cells and increased the release of MEPE/ASARM. These results suggest that the radiation-activated CHK1/MEPE pathway exacerbates the effects of microgravity on bone density loss, which may provide a novel targeting factor/pathway for a future countermeasure design that could contribute to reducing osteopenia in astronauts.

Keywords: Ionizing radiation, Microgravity, CHK1, MEPE, ASARM secretion, Bone density loss

1. Introduction

Low doses (≤0.5 Gy) of high linear energy transfer (LET) ionizing radiation (IR) in space (Zeitlin et al., 2013) and microgravity are two of the most important issues that affect astronauts’ health. Microgravity-induced bone density loss is one of the major risks to astronauts. The main concerns with high-LET IR are whether IR-induced DNA damage promotes carcinogenesis, tissue degeneration and aging. One additional concern with IR is whether IR and microgravity can synergistically promote bone density loss. There is evidence that IR above 1 Gy could induce osteopenia, which might be due to an increase of osteoclasts and bone resorption, as a consequence of changes in osteoprogenitors (Kondo et al., 2009, 2010; Willey et al., 2010; Yumoto et al., 2010). In mice, even ≤0.5 Gy of heavy ion exposure can induce osteopenia (Bandstra et al., 2009; Yumoto et al., 2010), which indicates that space radiation can stimulate microgravity-induced osteopenia; although, it remains unclear whether space radiation-induced osteopenia has a synergistic or additive effect (Alwood et al., 2010; Lloyd et al., 2012). Therefore, it is important to elucidate the mechanism by which radiation and microgravity promote osteopenia.

The matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) belongs to a family of proteins (small integrinbinding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs)) that also include four other members OPN, BSP, DMP1 and DSPP (Bellahcene et al., 2008). The MEPE gene was originally identified in a hypophosphatemic osteomalacia patient (Rowe et al., 2000). MEPE was found to be one of the key factors affecting bone mineralization via releasing the acidic serine- and aspartate-rich motif (ASARM) (507–525 amino acids (aa) at the C-terminal of MEPE) to serum (outside cells) (Addison et al., 2008; Argiro et al., 2001; Rowe, 2012, 2004; Rowe et al., 2004). The MEPE−/− mice have demonstrated the direct effect of MEPE on bone mineralization: compared with their wild type counterparts, up-regulating MEPE results in osteoporosis and knocking out MEPE results in much denser bone mass (David et al., 2009; Gowen et al., 2003). ASARM is a small 2.2-kDa protease-resistant peptide, it inhibits mineralization and phosphate uptake by binding to hydroxyapatite (Addison and McKee, 2010; Argiro et al., 2001). Therefore, any factors that promote generation/release of the ASARM from MEPE could promote bone density loss.

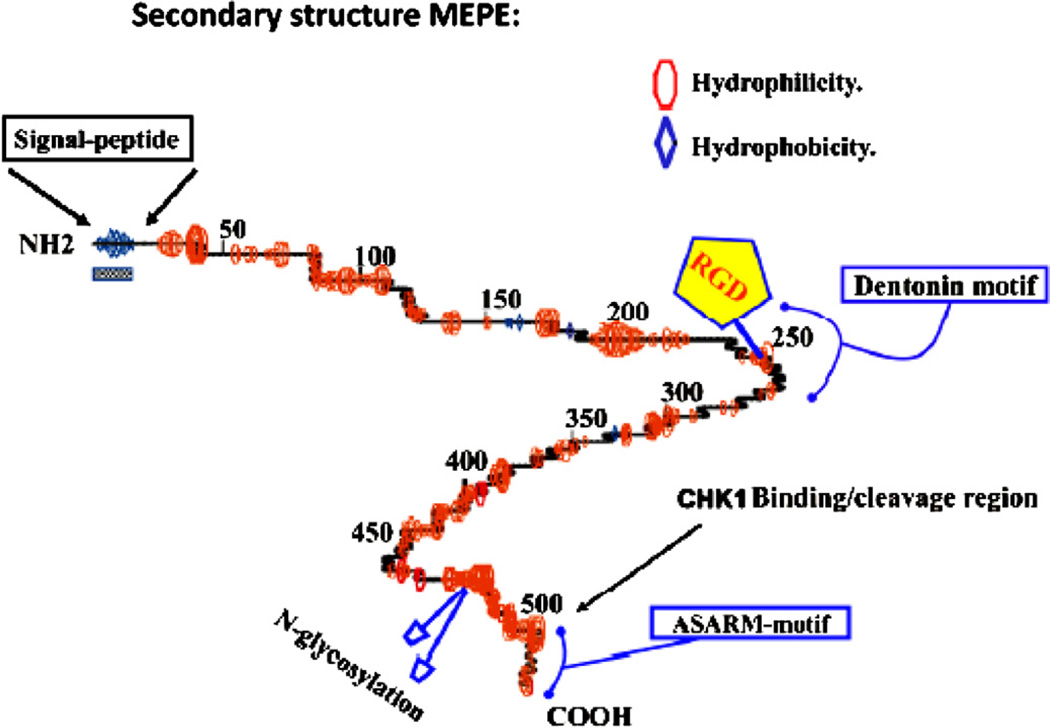

Previously, when we looked for partners for CHK1 in DNA damage response using the PCR-select cDNA subtraction approach in one rat cell line that highly expressed CHK1 (Hu et al., 2001), we unexpectedly identified that rat MEPE interacts with CHK1 to affect CHK1 degradation and cell response to IR-induced DNA damage (Liu et al., 2009). Later we verified it in human cells (Zhang et al., 2010). Interestingly, the key human MEPE domain (aa 488–507) that interacts with CHK1 (Zhang et al., 2010) overlaps with the MEPE sites digested by Cathepsin B (Fig. 1). Such data suggest that CHK1 might prevent osteopenia and osteoporosis via interacting with MEPE to reduce the generation/release of ASARM. The results from this study do support that IR activated CHK1, increased CHK1 degradation and increased the formation and the release of MEPE/ASARM to outside cells. These results will contribute to current knowledge pertaining to the mechanism by which the space environment induces bone density loss and may help to identify countermeasures to reduce this space mission-associated health risk.

Fig. 1.

Modified secondary structure was based on the prediction for MEPE as calculated using GCG peptide structure software 19,194 (Rowe, 2012) with the author’s permission. The primary amino acid backbone is shown as a central line with curves indicating regions of predicted turns. Regions of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity are represented as ellipsoids (red) and diamonds (blue) respectively. The RGD motif is highlighted with a pentagon. The N-glycosylation sites are represented as blue ellipsoids on stalks (C-terminus) and an alpha helix is indicated by undulating regions on the primary backbone. The signal peptide is indicated by a checkered box and coincides with a hydrophobic region at the N-terminus. The COOH-terminal ASARM motif is highlighted and the CHK1 binding region (Zhang et al., 2010) is indicated. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and irradiation

A human osteoblast cell line was purchased from ATCC (CRL-11372™). Irradiation was performed with a X-ray irradiator (X-RAD 320, N. Branford 320 kV, 10 mA, with 1.5 mm aluminum filtration, 0.8 mm tin, 0.25 mm copper for mice and 2 mm aluminum for cells) with a dose rate of 1 Gy/minute.

2.2. Examination of MEPE/ASARM levels in medium from cultured human cells

The levels of human MEPE/ASARM in medium from cultured human osteoblast cells were measured using a human MEPE ELISA kit (MBS703910) purchased from MyBioSource Inc. according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Cell culture using rotating conditions and western blot

Human osteoblast cells were cultured with a rotary culture system that was purchased from Synthecon Inc. The cells were seeded in the vessels with beads (for anchorage-dependent cells) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cell culture vessel rotated at a speed of 10–12 per min according to the instructions as described in a previous publication by Mangala et al. (2011). A standard Western blot assay was used to measure the protein levels of the cells. A specific antibody against auto-phosphorylated CHK1 at S296 (Cat #2349) was purchased from Cell Signaling. Cells treated with 2 mM hydroxyurea (HU) (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) for 2 h were used as a positive control for CHK1 activation. An antibody against total CHK1 (Cat# sc-8408) and an antibody against Actin (Cat# sc-47778) were purchased from Santa Cruz Technology Inc. The antibody against human MEPE (MBS712817) was purchased from MyBioSource Inc.

3. Results

3.1. One Gy of X ray exposure activated CHK1

We reported previously that after cells were exposed to IR (≥5 Gy of X-ray), CHK1 activated (Wang et al., 2003), the CHK1 level increased until 6 h and then gradually decreased, until 24 h after IR, the CHK1 level decreased to ~one fifth of original level (Hu et al., 2001). These results indicate that IR-activated CHK1 promotes CHK1 degradation, which has been confirmed by other groups (Zhang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2005). CHK1 activation promotes CHK1 degradation that is associated with a less protective role in preventing Cathepsin B from digesting the key MEPE sites, which results in an increased release of MEPE/ASARM. To answer the question whether 1 Gy of X-ray could activate CHK1, we measured the CHK1 autophosphorylation levels in human osteoblast cells at 3 h after the cells were exposed to 1 Gy of X-ray. The results showed that 5 Gy of X-ray exposure clearly activated CHK1 when HU-treated cells were used as a positive control (Feijoo et al., 2001; Zhao and Piwnica-Worms, 2001) (Fig. 2). There was no signal detected in the autophosphorylated CHK1 in the non-irradiated cells, and a weak signal was detected for the autophosphorylated CHK1 in 1 Gy of X-ray-irradiated cells (Fig. 2). To verify that the weak signal was the actual phosphorylated CHK1, we used PP2A, a phosphate responsible for dephosphorylating CHK1 (Leung-Pineda et al., 2006), to treat the cell lyses. The results showed that the autophosphorylated CHK1 signal disappeared when the cell lyses was treated with PP2A (Fig. 2). These results confirm that the signal was the phosphorylated CHK1, and demonstrate that 1 Gy of X-ray can activate CHK1. Since activated CHK1 stimulates CHK1 degradation (Zhang et al., 2005), these results suggest that CHK1 activation/degradation is associated with the release of the MEPE/ASARM.

Fig. 2.

IR (1 Gy of X-ray) exposure activated CHK1. Left panel: human osteoblast cells were exposed to X-ray (1 or 5 Gy). At 3 h after IR, the cells were collected for lyses preparation. The cells were treated with the lysis buffer, one set of samples were supplemented with 1 µM PP2A (with PP2A) and the other set of samples without PP2A (no PP2A) for 30 min. Protein levels were then detected in these samples using Western blot. 0, the control cells were not irradiated or not treated with HU; 1, the cells were exposed to 1 Gy of IR; 2, the cells were exposed to 5 Gy of IR; HU, the cells were treated with 2 mM HU for 2 h. p-CHK1, autophosphorylated CHK1 was detected with the specific antibody against S296. Total CHK1 in the cells was detected. Actin was used as an internal loading control. Similar results were obtained from two different experiments. Right panel: quantitative analysis of the phosphorylated CHK1 levels using the ImageQuant software.

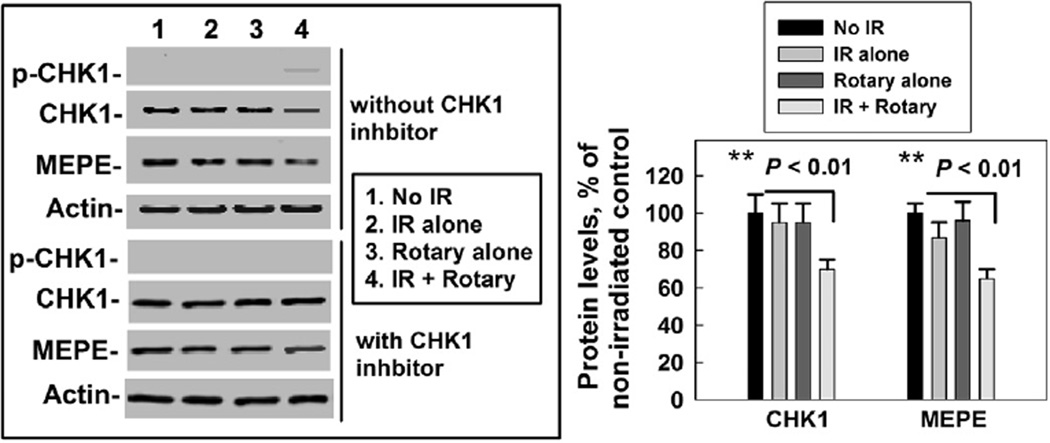

3.2. Rotated culture and 1 Gy of X-ray radiation have additive effects on activation/degradation of CHK1

Next, we wanted to know whether phosphorylated CHK1 is associated with a decreased CHK1 level at a later point after radiation. At the same time, we were interested in knowing whether a cell culture at a rotated (mimic microgravity status) condition could promote CHK1 activation/degradation. For this purpose, at 24 h post cell culture during a rotary or normal culture condition, the cells were collected to examine the protein levels by Western blot. The results showed that there was no phosphorylated CHK1 in non-irradiated cells no matter what condition the cells were cultured in, normal or rotary (Fig. 3), indicating that IR-induced DNA damage is a trigger for CHK1 activation. Interestingly, although no phosphorylated CHK1 was detected at 24 h after 1 Gy of X-ray irradiation in the normal cultured cells, the signal for phosphorylated CHK1 was still observed in rotary cultured cells (Fig. 3), indicating that the rotary culture (microgravity) could maintain the activated CHK1 status. At the same time, the total CHK1 level in the irradiated cells during rotary culture conditions was lower than in the non-irradiated cells cultured in rotary conditions or in irradiated cells cultured in normal culture conditions (Fig. 3), suggesting that the extended-activated CHK1 promoted CHK1 degradation. To verify whether the decreased CHK1 level was due to the extended activation of CHK1, we examined the effects of the CHK1 inhibitor (Exel-9844, obtained from Exelixis Inc.) on the CHK1 level in the cells that were irradiated and then cultured in rotary conditions for 24 h. Blocking CHK1 activation prevented the CHK1 level from decreasing (Fig. 3). These results further support that phosphorylated CHK1 promoted CHK1 degradation. Notably, the MEPE levels in the cells showed a similar change trend to the CHK1 level (Fig. 3), supporting that microgravity and radiation had an additive effect on decreased MEPE levels, suggesting that more digested MEPE in the cells may result in increased levels of MEPE/ASARM released to outside cells.

Fig. 3.

IR (X-ray, 1 Gy) and microgravity had additive effects on decreasing the levels of CHK1 and MEPE in human osteoblast cells. Left panel: Western blot images were obtained from human osteoblast cells collected without IR (No IR), at 24 h after irradiated with 1 Gy of X-ray (IR alone), cultured in rotary conditions for 24 h (Rotary alone) and at 24 h after irradiated with 1 Gy of X-ray and cultured in rotary conditions for 24 h (IR + rotary). Same set of cells was treated with a CHK1 inhibitor, Exel-9844 (3 µM) at 1 h before IR. p-CHK1: phosphorylated CHK1. Actin was used as an internal loading control. Similar results were obtained from three independent experiments. Right panel: we quantified the bane density from three Western blot images using the ImageQuant software. The value presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01.

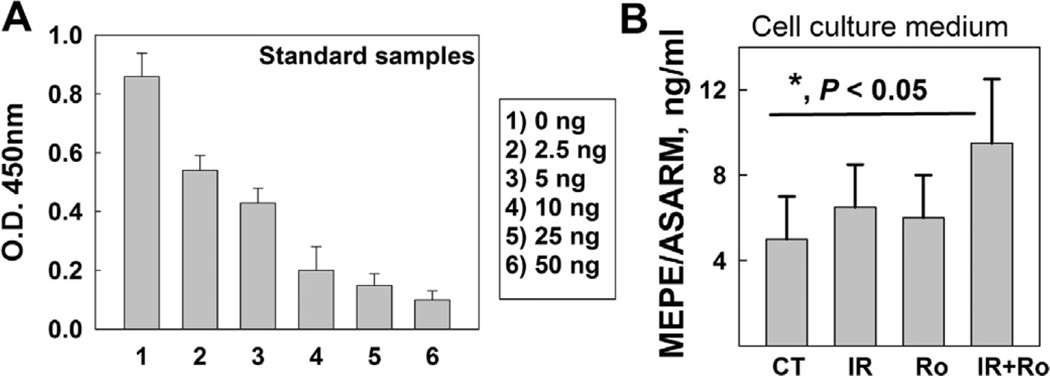

3.3. Radiation exposure and rotated culture resulted in an additive effect on the release of MEPE/ASARM in human osteoblast cells

To investigate whether microgravity can increase the effect of radiation-stimulated CHK1 activation/degradation on the release of MEPE/ASARM to outside cells, we measured the MEPE/ASARM levels in the culture medium using ELISA after the cells were irradiated with 1 Gy of X-ray and cultured in rotary conditions for 24 h. The results showed a correlation between the reduction of the MEPE level in the irradiated human osteoblast cells cultured in a rotary state for 24 h and the increased MEPE/ASARM levels in the cell culture medium (Fig. 4). These results support that more digested MEPE in the cells could result in an increased release of MEPE/ASARM levels to outside cells.

Fig. 4.

IR (X-ray, 1 Gy) and microgravity had an additive effect on releasing the ASARM motif to the outside of the human osteoblast cells. (A) The OD value was measured with different concentrations of MEPE/ASARM (ng/ml) included in the kit, which is used as the standard. (B) The supernatant of the cell culture medium were collected from human osteoblast cells. CT is used to identify the cells without IR cultured for 24 h in normal conditions. IR is used to identify the cells at 24 h after irradiated with 1 Gy of X-ray cultured in normal conditions. Ro means from the cells at 24 h after cultured in rotary conditions. IR + Ro is used to identify the cells at 24 h after irradiated with 1 Gy of X-ray cultured in rotary conditions. The MEPE/ASARM levels in the cultured medium were measured with the human MEPE/ASARM ELISA kit. The real concentrations of MEPE/ASARM (ng/ml) were calculated based on the OD value as described in A. The value presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In this study, we are the first to demonstrate that IR-activated CHK1 was associated with MEPE/ASARM release, and microgravity accelerated the biological event. These results suggest that IR-activated CHK1 may contribute to microgravity-induced bone density loss, which consequently contributes to whole body weight loss.

Although the effects of acute radiation on bone loss are short term, it is reasonable to consider that astronauts in space are continually exposed to low doses of radiation, which may have a long-term effect on promoting bone loss. Bone density changes manifest in multiple ways, including changes in osteoclastic bone resorption or osteoblastic bone formation, or changes in both. Since ASARM is relevant to osteomalacia, it points strongly to an inhibition of mineralization. Therefore, our results suggest that 1 Gy of X-ray exposure could promote MEPE/ASARM release and in turn inhibit mineralization. These results suggest that accumulated space radiation prevents bone mineralization in astronauts, which needs further studies since the Mars mission requires that astronauts travel in space for ~3 years.

Previously, we and other groups demonstrated that CHK1 is one of the key factors in the response to DNA damage (including IR) through activating cell cycle checkpoints (Wang et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002). CHK1 is a protein with a fast turnover and its expression depends on the cell cycle (Kaneko et al., 1999). After DNA damage, CHK1 is phosphorylated at aa 317 and 345 by ATR, its upstream kinase, which not only activates CHK1 that results in CHK1 autophosphorylation (S296) and phosphorylates its downstream targets, but also stimulates CHK1 degradation through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (Zhang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2005). We also discovered that CHK1 interacts directly with MEPE (Liu et al., 2009), and the key domain of human MEPE at the C-terminal region (aa 488–507) interacts with CHK1 and protects CHK1 from ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (Yu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Since the key domain where MEPE interacts with CHK1 overlaps with the digestion sites of MEPE by Cathepsin B (Fig. 1), it is reasonable to think that CHK1 interaction with MEPE prevents ASARM release. Our results shown in this study strongly support that IR activates CHK1 and microgravity helps to maintain CHK1 activation, which promotes CHK1 degradation, reduces the interaction between CHK1 and MEPE, and results in more MEPE digestion by Cathepsin B and ASARM release.

In summary, our results strongly support that space radiation exacerbates microgravity-induced osteopenia through modulating the CHK1-MEPE pathway. We believe that the results from this study will contribute to the identification of new markers to evaluate the risk that space radiation exacerbates the effects of microgravity-induced bone density loss, and provides a new factor/pathway for targeting to reduce the risk.

Acknowledgments

We thank Doreen Theune for editing the manuscript. This work is supported by grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX11AC30G to Y.W. and P30CA138292 to the Institute).

Abbreviations

- LET

Linear energy transfer

- IR

Ionizing radiation

- MEPE

Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein

- ASARM

Acidic serine- and aspartate-rich motif

- aa

Amino acids

- SIBLINGs

Small integrinbinding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Addison WN, McKee MD. ASARM mineralization hypothesis: a bridge to progress. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25:1191–1192. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addison WN, Nakano Y, Loisel T, Crine P, McKee MD. MEPE-ASARM peptides control extracellular matrix mineralization by binding to hydroxyapatite: an inhibition regulated by PHEX cleavage of ASARM. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:1638–1649. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwood JS, Yumoto K, Mojarrab R, Limoli CL, Almeida EA, Searby ND, Globus RK. Heavy ion irradiation and unloading effects on mouse lumbar vertebral microarchitecture, mechanical properties and tissue stresses. Bone. 2010;47:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiro L, Desbarats M, Glorieux FH, Ecarot B. Mepe, the gene encoding a tumor-secreted protein in oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia, is expressed in bone. Genomics. 2001;74:342–351. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandstra ER, Thompson RW, Nelson GA, Willey JS, Judex S, Cairns MA, Benton ER, Vazquez ME, Carson JA, Bateman TA. Musculoskeletal changes in mice from 20–50 cGy of simulated galactic cosmic rays. Radiat. Res. 2009;172:21–29. doi: 10.1667/RR1509.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KUE, Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:212–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David V, Martin A, Hedge AM, Rowe PS. Matrix extracellular phosphogly-coprotein (MEPE) is a new bone renal hormone and vascularization modulator. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4012–4023. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijoo C, Hall-Jackson C, Wu R, Jenkins D, Leitch J, Gilbert DM, Smythe C. Activation of mammalian Chk1 during DNA replication arrest: a role for Chk1 in the intra-S phase checkpoint monitoring replication origin firing. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LC, Petersen DN, Mansolf AL, Qi H, Stock JL, Tkalcevic GT, Simmons HA, Crawford DT, Chidsey-Frink KL, Ke HZ, McNeish JD, Brown TA. Targeted disruption of the osteoblast/osteocyte factor 45 gene (OF45) results in increased bone formation and bone mass. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1998–2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Zhou XY, Wang X, Zeng ZC, Iliakis G, Wang Y. The radioresistance to killing of A1–5 cells derives from activation of the Chk1 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17693–17698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko YS, Watanabe N, Morisaki H, Akita H, Fujimoto A, Tominaga K, Tachibana A, Ikeda K, Nakanishi M. Cell cycle-dependent and ATM-independent expression of human Chk1 kinase. Oncogene. 1999;18:3673–3681. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Searby ND, Mojarrab R, Phillips J, Alwood J, Yumoto K, Almeida EA, Limoli CL, Globus RK. Total-body irradiation of postpubertal mice with (137)Cs acutely compromises the microarchitecture of cancellous bone and increases osteoclasts. Radiat. Res. 2009;171:283–289. doi: 10.1667/RR1463.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Yumoto K, Alwood JS, Mojarrab R, Wang A, Almeida EA, Searby ND, Limoli CL, Globus RK. Oxidative stress and gamma radiation-induced cancellous bone loss with musculoskeletal disuse. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;108:152–161. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00294.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung-Pineda V, Ryan CE, Piwnica-Worms H. Phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR is antagonized by a Chk1-regulated protein phosphatase 2A circuit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:7529–7538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00447-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Wang H, Wang X, Lu L, Gao N, Rowe PS, Hu B, Wang Y. MEPE/OF45 protects cells from DNA damage induced killing via stabilizing CHK1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7447–7454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lloyd SA, Bandstra ER, Willey JS, Riffle SE, Tirado-Lee L, Nelson GA, Pecaut MJ, Bateman TA. Effect of proton irradiation followed by hindlimb unloading on bone in mature mice: a model of long-duration spaceflight. Bone. 2012;51:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangala LS, Zhang Y, He Z, Emami K, Ramesh GT, Story M, Rohde LH, Wu H. Effects of simulated microgravity on expression profile of microRNA in human lymphoblastoid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:32483–32490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe PS. The wrickkened pathways of FGF23, MEPE and PHEX. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004;15:264–281. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe PS. Regulation of bone-renal mineral and energy metabolism: the PHEX, FGF23, DMP1, MEPE ASARM pathway. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2012;22:61–86. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v22.i1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe PS, de Zoysa PA, Dong R, Wang HR, White KE, Econs MJ, Oudet CL. MEPE, a new gene expressed in bone marrow and tumors causing osteomalacia. Genomics. 2000;67:54–68. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe PS, Kumagai Y, Gutierrez G, Garrett IR, Blacher R, Rosen D, Cundy J, Navvab S, Chen D, Drezner MK, Quarles LD, Mundy GR. MEPE has the properties of an osteoblastic phosphatonin and minhibin. Bone. 2004;34:303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Khadpe J, Hu B, Iliakis G, Wang Y. An over-activated ATR/CHK1 pathway is responsible for the prolonged G2 accumulation in irradiated AT cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30869–30874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey JS, Livingston EW, Robbins ME, Bourland JD, Tirado-Lee L, Smith-Sielicki H, Bateman TA. Risedronate prevents early radiation-induced osteoporosis in mice at multiple skeletal locations. Bone. 2010;46:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Wang H, Liu S, Zhang X, Guida P, Hu B, Wang Y. A small peptide mimicking the key domain of MEPE/OF45 interacting with CHK1 protects human cells from radiation-induced killing. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1981–1985. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumoto K, Globus RK, Mojarrab R, Arakaki J, Wang A, Searby ND, Almeida EA, Limoli CL. Short-term effects of whole-body exposure to 56Fe ions in combination with musculoskeletal disuse on bone cells. Radiat. Res. 2010;173:494–504. doi: 10.1667/RR1754.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin C, Hassler DM, Cucinotta FA, Ehresmann B, Wimmer-Schweingruber RF, Brinza DE, Kang S, Weigle G, Böttcher S, Böhm E, Burmeister S, Guo J, Köhler J, Martin C, Posner A, Rafkin S, Reitz G. Measurements of energetic particle radiation in transit to Mars on the Mars science laboratory. Science. 2013;340:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1235989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wang H, Rowe PS, Hu B, Wang Y. MEPE/OF45 as a new target for sensitizing human tumor cells to DNA damage inducers. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;102:862–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y-W, Brognard J, Coughlin C, You Z, Dolled-Filhart M, Aslanian A, Manning G, Abraham RT, Hunter T. The F box protein Fbx6 regulates Chk1 stability and cellular sensitivity to replication stress. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y-W, Otterness DM, Chiang GG, Xie W, Liu Y-C, Mercurio F, Abraham RT. Genotoxic stress targets human Chk1 for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4129–4139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Watkins JL, Piwnica-Worms H. Disruption of the checkpoint kinase 1/cell division cycle 25A pathway abrogates ionizing radiation-induced S and G2 checkpoints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14795–14800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182557299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XY, Wang X, Hu B, Guan J, Iliakis G, Wang Y. An ATM-independent S phase checkpoint response involves CHK1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1598–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]