Abstract

Background

Considerable research has documented that exposure to traumatic events has negative effects on physical and mental health. Much less research has examined the predictors of traumatic event exposure. Increased understanding of risk factors for exposure to traumatic events could be of considerable value in targeting preventive interventions and anticipating service needs.

Method

General population surveys in 24 countries with a combined sample of 68 894 adult respondents across six continents assessed exposure to 29 traumatic event types. Differences in prevalence were examined with cross-tabulations. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine whether traumatic event types clustered into interpretable factors. Survival analysis was carried out to examine associations of sociodemographic characteristics and prior traumatic events with subsequent exposure.

Results

Over 70% of respondents reported a traumatic event; 30.5% were exposed to four or more. Five types – witnessing death or serious injury, the unexpected death of a loved one, being mugged, being in a life-threatening automobile accident, and experiencing a life-threatening illness or injury – accounted for over half of all exposures. Exposure varied by country, sociodemographics and history of prior traumatic events. Being married was the most consistent protective factor. Exposure to interpersonal violence had the strongest associations with subsequent traumatic events.

Conclusions

Given the near ubiquity of exposure, limited resources may best be dedicated to those that are more likely to be further exposed such as victims of interpersonal violence. Identifying mechanisms that account for the associations of prior interpersonal violence with subsequent trauma is critical to develop interventions to prevent revictimization.

Keywords: Disasters, epidemiology, injury, revictimization, trauma, violence

Introduction

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines a traumatic event (TE) as exposure to threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence. Such exposure may occur directly or indirectly by witnessing the event, learning of the event occurring to a loved one, or repeated confrontation with aversive details of such event (e.g. emergency responders) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Exposure to TEs is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and is also associated with a wide range of other adverse mental and physical health outcomes (e.g. Turner & Lloyd, 1995; Norman et al. 2006; Galea et al. 2007; Spitzer et al. 2009; Keyes et al. 2013; Scott et al. 2013). Understanding who is at risk for exposure to TEs is consequently of considerable interest. However, trauma research has focused mainly on consequences of exposure. Much less is known about the distribution or predictors of TEs. Such information could be valuable in targeting preventive interventions and anticipating service needs.

General population studies have shown that a large proportion of people in developed countries have been exposed to at least one TE in their lifetime (estimates from 28 to 90%), with the most common events being the unexpected death of a loved one, motor vehicle accidents and being mugged (e.g. Norris, 1992; Breslau et al. 1998; Hepp et al. 2006; Storr et al. 2009; Roberts et al. 2011; Ogle et al. 2014). Much more limited evidence for less developed countries suggests that fatalities due to injuries and accidents are more common in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries (Herbert et al. 2011); for example, road injuries are the 10th leading cause of lost years of life in developed countries and the 8th leading cause in developing countries (GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators, 2014). However, the cross-national prevalence of exposure to TEs is unknown as no study of which we are aware has examined the full range of TEs in population-based samples using the same methods across a wide range of countries that differ in level of economic development.

We are aware of only one review of the determinants of TE exposure (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). That paper considered basic sociodemographic predictors (gender, socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, age) and focused entirely on developed countries (primarily the USA). The authors found, not surprisingly, that men and women differ in the types of events they experience, with men reporting more injuries, accidents and physical assault and women reporting more sexual assault. They also found that low socio-economic status, racial/ethnic minority status and being a young adult were associated with increased TE exposure. There is good reason to think, though, that socio-demographic predictors will vary in magnitude and by type of TE, as some TEs, like natural disasters, are more randomly distributed in the population than others. We would also expect to find significant associations of geographic location and cohort with exposure to some types of TEs due to time–space variation in the occurrence of historical events (e.g. wars, and natural and man-made disasters).

Another important issue is that many people with a history of TE exposure have been exposed to multiple TEs. Sledjeski et al. (2008), for example, reported that the people reporting lifetime exposure to TEs in an epidemiological survey of the US household population experienced an average 3.3 TEs. It is unclear, though, whether lifetime TEs are related to each other and, if so, if there are any causal associations between exposure to initial TEs and risk of subsequent exposure. The literature suggests that such associations exist, most notably in the discussion of the possible existence of an ‘accident-prone’ personality (Visser et al. 2007). Another example is revictimization, whereby childhood abuse is associated with subsequent exposure to interpersonal partner violence and sexual assault, with the suggestion that the psychological consequences of victimization increase vulnerability for further victimization (Coid et al. 2001; Testa et al. 2007; Daigneault et al. 2009). However, the time-lagged associations among the full range of TEs have not been examined. Critical questions remain as to whether all types of TE exposure are associated with increased risk of subsequent exposure, whether there is specificity within types, or whether specific types of TE exposure are particularly important predictors of subsequent exposure.

The current report attempts to address the limitation in previous studies of TE exposure by estimating the prevalence and examining sociodemographic correlates of a wide range of TEs in 26 surveys from 24 countries that participated in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh). We first conducted a factor analysis to examine whether TEs cluster into interpretable factors. Second, we calculated the lifetime prevalence of each TE and the proportions of all TEs due to each type both within and across countries. We also report the frequency of TE exposure per 100 respondents across countries. Third, we examined sociodemographic characteristics and prior TEs as predictors of subsequent TEs. Thus we provide a panorama of TE exposure across different countries that might help shape public policies.

Method

Sample

The WMH Surveys are a series of general population studies carried out throughout the world from 2001 to 2012 (Kessler & Ustun, 2008; Von Korff et al. 2009; Nock et al. 2012; Alonso et al. 2013). Respondents in the current report came from 26 WMH Surveys conducted in 24 countries, including 14 surveys from high-income countries, seven from upper-middle-income countries, and six from low-/lower-middle-income countries (Table 1). Most surveys included nationally representative household samples, although a few focused on specific urban areas or states. A total of 125 718 adults participated in the surveys. The average weighted response rate was 70.4% (range 45.9–97.2%). More details about WMH samples are reported elsewhere (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Table 1.

WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categoriesa

| Survey | Sample characteristicsb | Field dates | Age range, yearsc | Sample size

|

Response rated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | Part 2 | ||||||

| I. Low-/lower-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Colombia | NSMH | All urban areas (73% of the total national population) | 2003 | 18–65 | 4426 | 2381 | 87.7 |

| Nigeria | NSMHW | 21 of 36 states (57% of the national population) | 2002–3 | 18–100 | 6752 | 2143 | 79.3 |

| People’s Republic of China – Beijing/Shanghai | B-WMH/S-WMH | Beijing and Shanghai metropolitan areas | 2002–3 | 18–70 | 5201 | 1628 | 74.7 |

| Peru | EMSMP | Nationally representative | 2004–5 | 18–65 | 3930 | 1801 | 90.2 |

| Ukraine | CMDPSD | Nationally representative | 2002 | 18–91 | 4724 | 1719 | 78.3 |

| II. Upper-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Brazil – São Paulo | São Paulo | São Paulo metropolitan area | 2005–7 | 18–93 | 5037 | 2942 | 81.3 |

| Bulgaria | NSHS | Nationally representative | 2003–7 | 18–98 | 5318 | 2233 | 72 |

| Lebanon | L.E.B.A.N.O.N. | Nationally representative | 2002–3 | 18–94 | 2857 | 1031 | 70 |

| Colombia – Medellin | MMHHS | Medellin metropolitan area | 2011–12 | 19–65 | 3261 | 1673 | 97.2 |

| Mexico | M-NCS | All urban areas (75% of the total national population) | 2001–2 | 18–65 | 5782 | 2362 | 76.6 |

| Romania | RMHS | Nationally representative | 2005–6 | 18–96 | 2357 | 2357 | 70.9 |

| South Africa | SASH | Nationally representative | 2003–4 | 18–92 | 4315 | 4315 | 87.1 |

| III. High-income countries | |||||||

| Australia | NSMHWB | Nationally representative | 2007 | 18–85 | 8463 | 8463 | 60 |

| Belgium | ESEMeD | Nationally representative (national register of Belgium residents) | 2001–2 | 18–95 | 2419 | 1043 | 50.6 |

| France | ESEMeD | Nationally representative (of households with listed telephone numbers) | 2001–2 | 18–97 | 2894 | 1436 | 45.9 |

| Germany | ESEMeD | Nationally representative | 2002–3 | 18–95 | 3555 | 1323 | 57.8 |

| Israel | NHS | Nationally representative | 2002–4 | 21–98 | 4859 | 4859 | 72.6 |

| Italy | ESEMeD | Nationally representative (municipality resident registries) | 2001–2 | 18–100 | 4712 | 1779 | 71.3 |

| Japan | WMHJ 2002–2006 | 11 metropolitan areas | 2002–6 | 20–98 | 4129 | 1682 | 55.1 |

| Spain – Murcia | PEGASUS-Murcia | Murcia region | 2010–12 | 18–64 | 2621 | 1459 | 67.4 |

| Netherlands | ESEMeD | Nationally representative (municipal postal registries) | 2002–3 | 18–95 | 2372 | 1094 | 56.4 |

| New Zealand | NZMHS | Nationally representative | 2003–4 | 18–98 | 12 790 | 7312 | 73.3 |

| Northern Ireland | NISHS | Nationally representative | 2004–7 | 18–97 | 4340 | 1986 | 68.4 |

| Portugal | NMHS | Nationally representative | 2008–9 | 18–81 | 3849 | 2060 | 57.3 |

| Spain | ESEMeD | Nationally representative | 2001–2 | 18–98 | 5473 | 2121 | 78.6 |

| USA | NCS-R | Nationally representative | 2002–3 | 18–99 | 9282 | 5692 | 70.9 |

| IV. Total | 125 718 | 68 894 | 70.4 | ||||

WMH, World Mental Health; NSMH, Colombian National Study of Mental Health; NSMHW, Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; B-WMH, Beijing World Mental Health Survey; S-WMH, Shanghai World Mental Health Survey; EMSMP, La Encuesta Mundial de Salud Mental en el Peru; CMDPSD, Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption; NSHS, Bulgaria National Survey of Health and Stress; L.E.B.A.N.O.N., Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation; MMHHS, Medellín Mental Health Household Study; M-NCS, Mexico National Comorbidity Survey; RMHS, Romania Mental Health Survey; SASH, South Africa Health Survey; NSMHWB, National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders; NHS, Israel National Health Survey; WMHJ 2002–2006, World Mental Health Japan Survey; PEGASUS-Murcia, Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain-Murcia; NZMHS, New Zealand Mental Health Survey; NISHS, Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress; NMHS, Portugal National Mental Health Survey; NCS-R, US National Comorbidity Survey Replication.

World Bank data from May 2012. Some of the WMH countries have moved into new income categories since the surveys were conducted. The income groupings above reflect the status of each country at the time of data collection. For the current income category of each country, see The World Bank (2015).

Most WMH Surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the USA were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g. towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and the Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH surveys (Belgium, Germany, Italy) used municipal resident registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally unclustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the 11 metropolitan areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. Of the 26 surveys, 18 are based on nationally representative household samples.

For the purposes of cross-national comparisons we limit the sample to those aged 18+ years.

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. The weighted average response rate is 70.4%.

All respondents completed part I of the interview, which included an evaluation of core psychiatric disorders, while part II was administered to a subsample of 68 894 respondents consisting of all those with any part I lifetime mental disorder and a probability subsample of other part I respondents. Part II focused on services, risk factors and other psychiatric disorders, including TEs and PTSD. Part II respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection into part II, thus making the weighted part II sample representative of the part I sample. Additional weights adjusted for differential probabilities of selection within households and non-response, and matched the sample sociodemographic and geographic distributions to population distributions (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Field procedure

Interviews were conducted face to face in the homes of respondents. Informed consent was obtained based on procedures approved by each institutional review board of the organizations responsible for the survey in each country. The interview schedule was translated, back-translated and harmonized using standardized WHO procedures (Harkness et al. 2008). Bilingual supervisors from each country were trained and supervised by the WMH Data Collection Coordination Center to guarantee cross-national consistency in field procedures (Pennell et al. 2008).

Measures

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 assessed psychiatric disorders (Kessler & Ustun, 2004). The CIDI included a module on DSM-IV PTSD that inquired about lifetime exposure to each of 27 different TEs (criterion A1). Respondents who reported ever experiencing any of the TEs were then asked about the number of exposures (NOE) and age at first exposure (AOE) for each.

Respondents were also asked if they ever experienced any other extremely traumatic or life-threatening event not already captured in the TE checklist and, if so, about the respective NOE and AOE. Finally, respondents were asked about any TE that was not endorsed due to its private nature. The question posed was as follows: ‘Sometimes people have experiences they don’t want to talk about in interviews. I won’t ask you to describe anything like this, but, without telling me what it was, did you ever have a traumatic event that you didn’t tell me about because you didn’t want to talk about it?’ Respondents who reported a private TE were asked about NOE and AOE.

Sociodemographic variables considered here were age, gender, marital status (never married; previously married, including those divorced, separated, and widowed; and currently married), and education (low, low-average, high-average, and high based on country-specific distributions).

Statistical analyses

Lifetime prevalence of each TE and the proportions of all TEs due to each type were calculated both within and across countries. A matrix of tetrachoric correlations among TE types was created and exploratory factor analysis carried out with promax rotation to determine if bivariate associations among TEs clustered into interpretable factors. Time-lagged associations of temporally primary TEs predicting the subsequent first onset of each other TE type were then examined using discrete-time survival analysis with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function (Willett & Singer, 1993). Sociodemographic predictors were also included in those models. Models were pooled across countries.

The survival models were initially estimated separately for each TE type (the 27 listed TEs, other TEs and private TEs) across all countries combined, with dummy variables to control for between-country differences in prevalence. The implicit assumption was that the associations (odds ratios; ORs) of predictors with outcomes were constant across countries. Given the large number of TE types considered, the person-year data files for the 29 TE types were then pooled into more highly aggregated data files, one for the set of TEs in each factor uncovered in the exploratory factor analysis. Inspection of coefficients in the 29 trauma-specific models was used to confirm the validity of this pooling. Interaction tests subsequently were used to evaluate the assumptions of constant ORs across countries and TE types within each factor. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated to create ORs and 95% confidence intervals.

The Taylor series linearization method (Wolter, 1985) was implemented in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., 2011) to adjust for the weighting, including non-response and post-stratification weighting, and geographic clustering of the WMH sample. Multivariate significance was evaluated using design-based Wald χ2 tests. Statistical significance was evaluated with 0.05-level two-sided tests.

Results

Tetrachoric factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis extracted five meaningful factors from the promax rotated matrix of tetrachoric correlations among the TE types (Table 2). The first factor represents TEs associated with exposure to collective violence (e.g. being a civilian in a war zone, a relief worker in a war zone, a refugee). The second factor encompasses TEs associated with causing or witnessing serious bodily harm to others (e.g. purposely injuring, torturing or killing someone; combat experience). The third factor represents TEs associated with exposure to interpersonal violence (e.g. beaten up by a caregiver as a child, witnessed physical fights at home as a child, beaten up by someone other than a romantic partner). The fourth factor represents TEs associated with exposure to intimate partner or sexual violence (e.g. physically assaulted by a romantic partner, raped, sexually assaulted). Interestingly, other TEs and private TEs both had their highest standardized partial regression coefficients (the equivalents of factor loadings) on this factor, suggesting that these highly personal events were more similar to intimate partner or sexual violence than to other types of TEs. The fifth factor encompassed TEs associated with accidents and injuries (e.g. natural disasters, automobile accidents). Three types – unexpected death of a loved one, mugged or threatened with a weapon, and man-made disaster – cross-loaded on more than one factor, capturing the mixture of contexts in which these events occurred. Consequently, these three TEs were examined individually in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Factor analysisa of person-year level exposure across countries (n = 68 894)

| I. Collective violence | II. Caused/witnessed bodily harm | III. Interpersonal violence | IV. Intimate partner/sexual violence | V. Accident/injuries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Collective violence | |||||

| Civilian in war zone | 0.88 | −0.17 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Refugee | 0.80 | 0.05 | −0.29 | 0.10 | −0.10 |

| Civilian in region of terror | 0.78 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Kidnapped | 0.61 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.23 | −0.20 |

| Relief worker in war zone | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.16 | −0.33 | 0.28 |

| II. Caused/witnessed bodily harm | |||||

| Purposely injured, tortured or killed someone | −0.21 | 0.97 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.04 |

| Combat experience | 0.13 | 0.82 | −0.10 | −0.20 | 0.03 |

| Accidentally caused serious injury or death | −0.14 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.07 |

| Saw atrocities | 0.36 | 0.58 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Witnessed death/dead body/someone seriously hurt | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| III. Interpersonal violence | |||||

| Beaten up by caregiver | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Witnessed physical fights at home | −0.14 | −0.01 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| Beaten up by someone else | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| IV. Intimate partner/sexual violence | |||||

| Raped | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.29 | 0.74 | −0.05 |

| Sexually assaulted | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.02 |

| Beaten up by spouse or romantic partner | 0.04 | −0.25 | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0.17 |

| Stalked | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.02 |

| Traumatic event to loved one | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.52 | −0.01 |

| Private event | −0.03 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.47 | 0.05 |

| Other event | 0.09 | 0.31 | −0.18 | 0.43 | 0.09 |

| V. Accident/injuries | |||||

| Child with serious illness | −0.02 | −0.17 | −0.18 | 0.31 | 0.65 |

| Natural disaster | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.61 |

| Life-threatening illness | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.20 | 0.24 | 0.58 |

| Toxic chemical exposure | −0.04 | 0.26 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.57 |

| Other life-threatening accident | −0.04 | 0.18 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.57 |

| Automobile accident | −0.12 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.49 |

| VI. Other traumas | |||||

| Unexpected death of loved one | −0.01 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Mugged or threatened with a weapon | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| Man-made disaster | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.36 |

Factor loadings based on a tetrachoric factor analysis with promax rotation.

The most common TE types across countries

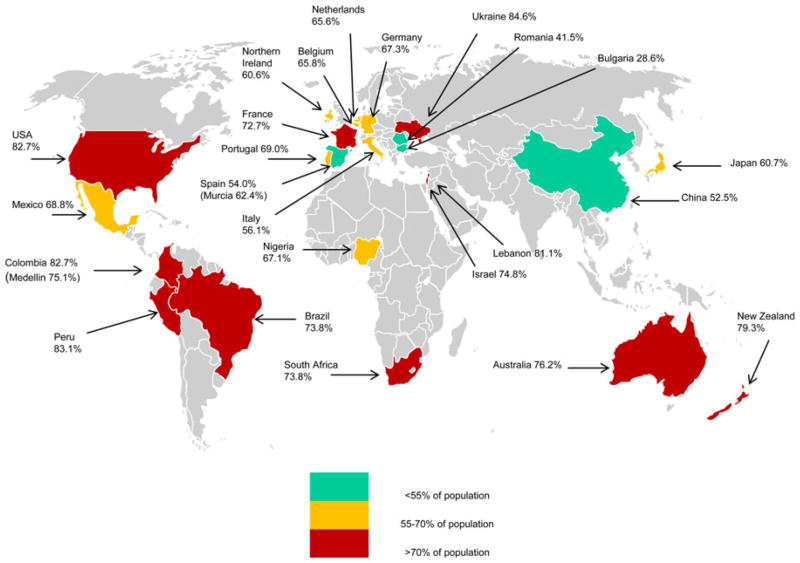

Pooled across all countries, 70.4% of respondents experienced at least one lifetime TE (Fig. 1). The range was quite wide across countries, from a low of 28.6% in Bulgaria to a high of 84.6% in Ukraine, although the interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentiles) of 60.7–76.2% was relatively narrow across countries (Table 3 and online Supplementary Table S1). Of the respondents, 18.2 (S.E. = 0.2) % had been exposed to exactly one TE, 12.7 (S.E. = 0.2) % to two TEs, 9.1 (S.E. = 0.2) % to three TEs and 30.5 (S.E. = 0.3) % to four or more different TEs. Because many people experienced more than one TE, the rate of exposure to any TE was 321.5 per 100 respondents (mean rates for each TE factor by country are described in online Supplementary Table S2 and text). Overall, the most common TE factor was accidents/injuries (36.3%) and least common collective violence (9.4%). The most commonly reported individual TE type was unexpected death of a loved one, which was experienced by 31.4% of all respondents (IQR = 23.3–36.9% across countries) and represented nearly one-sixth (16.5%) of all instances of TE exposure reported in the total sample.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of exposure to any traumatic event in each survey of the 24 countries.

Table 3.

Prevalence of traumatic events and each event as a proportion of all traumas

| Traumatic event | n | Prevalence

|

% of all traumasa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (S.E.) | IQR of countries

|

% (S.E.) | IQR of countries

|

||||

| 25th percentile | 75th percentile | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | ||||

| I. Collective violence | |||||||

| Civilian in war zoneb | 3201 | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.4 | 6.8 | 1.4 (0.0) | 0.9 | 3.2 |

| Refugeec | 1656 | 2.3 (0.1) | 0.6 | 2.6 | 0.7 (0.0) | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Civilian in region of terrorb | 2501 | 3.9 (0.1) | 1.3 | 5.6 | 1.1 (0.0) | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Kidnapped | 886 | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Relief worker in war zoneb | 635 | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Any collective violence | 6868 | 9.4 (0.2) | 6.1 | 13.9 | 3.8 (0.1) | 2.5 | 5.7 |

| II. Caused/witnessed bodily harm | |||||||

| Purposely injured/tortured/killedd | 670 | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 (0.0) | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Combat experiencec | 2038 | 3.2 (0.1) | 1.2 | 4.5 | 1.0 (0.0) | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Accidentally caused injury/death | 1060 | 1.4 (0.1) | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.7 (0.0) | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| Saw atrocities | 2634 | 3.7 (0.1) | 1.2 | 3.9 | 2.4 (0.1) | 0.5 | 2.5 |

| Witnessed death/dead body/someone hurt | 17 161 | 23.7 (0.3) | 18.0 | 27.3 | 16.8 (0.2) | 14.0 | 19.1 |

| Any caused/witnessed bodily harm | 18 965 | 26.3 (0.3) | 20.4 | 31.4 | 21.4 (0.2) | 17.6 | 23.3 |

| III. Interpersonal violence | |||||||

| Beaten up by caregiver | 7019 | 7.9 (0.1) | 3.1 | 10.2 | 2.5 (0.0) | 1.2 | 3.8 |

| Witnessed physical fights at homee | 6808 | 12.9 (0.2) | 10.4 | 18.2 | 2.5 (0.0) | 2.8 | 5.0 |

| Beaten up by someone else | 4558 | 5.9 (0.1) | 3.5 | 7.3 | 3.6 (0.1) | 2.2 | 3.9 |

| Any interpersonal violence | 13 882 | 17.0 (0.2) | 6.3 | 21.0 | 8.5 (0.1) | 4.3 | 11.3 |

| IV. Intimate partner/sexual violence | |||||||

| Raped | 3342 | 3.2 (0.1) | 0.6 | 3.4 | 1.8 (0.1) | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| Sexually assaulted | 5261 | 5.8 (0.1) | 1.7 | 6.2 | 3.6 (0.1) | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| Beaten up by spouse/partner | 4602 | 4.5 (0.1) | 2.4 | 6.0 | 1.4 (0.0) | 1.0 | 1.9 |

| Stalked | 4646 | 5.4 (0.1) | 2.8 | 6.0 | 3.0 (0.1) | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| Traumatic event to loved one | 4527 | 5.6 (0.1) | 1.7 | 6.2 | 2.7 (0.1) | 1.3 | 2.8 |

| Private event | 4171 | 4.9 (0.1) | 3.5 | 5.8 | 1.5 (0.0) | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| Other event | 3297 | 4.2 (0.1) | 2.0 | 5.1 | 1.3 (0.0) | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| Any intimate partner/sexual violence | 19 058 | 22.8 (0.3) | 15.7 | 25.1 | 15.3 (0.2) | 11.3 | 15.4 |

| V. Accidents/injuries | |||||||

| Child with serious illness | 6370 | 7.9 (0.1) | 5.2 | 9.2 | 3.1 (0.1) | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| Natural disasterc | 5603 | 7.7 (0.2) | 3.9 | 9.6 | 4.1 (0.1) | 1.9 | 6.2 |

| Life-threatening illness | 9377 | 11.8 (0.2) | 8.0 | 13.2 | 5.1 (0.1) | 4.4 | 6.8 |

| Toxic chemical exposure | 3005 | 4.2 (0.1) | 1.9 | 4.1 | 3.6 (0.1) | 2.2 | 3.9 |

| Other life-threatening accident | 4537 | 6.2 (0.1) | 4.1 | 7.3 | 2.9 (0.1) | 2.3 | 3.4 |

| Automobile accident | 10 131 | 14.0 (0.2) | 9.3 | 16.3 | 6.1 (0.1) | 4.8 | 7.3 |

| Any accidents/injuries | 26 972 | 36.3 (0.3) | 28.5 | 39.4 | 24.9 (0.2) | 21.7 | 28.9 |

| VI. Other traumas | |||||||

| Unexpected death of loved one | 23 792 | 31.4 (0.3) | 23.3 | 36.9 | 16.5 (0.2) | 14.2 | 18.3 |

| Mugged/threatened with weapon | 10 562 | 14.5 (0.2) | 6.5 | 18.3 | 7.4 (0.1) | 3.6 | 9.8 |

| Man-made disaster | 3001 | 4.0 (0.1) | 2.4 | 5.3 | 2.1 (0.1) | 1.3 | 3.8 |

| Any others | 30 218 | 40.8 (0.3) | 33.5 | 48.7 | 26.1 (0.2) | 23.1 | 29.2 |

| Any event | 50 855 | 70.4 (0.3) | 60.7 | 76.2 | 100.0 (0.0) | 1.4 | 4.4 |

IQR, Interquartile range; s.e., standard error.

Includes information on repeat exposures.

Brazil and Israel did not ask about this trauma.

Brazil did not ask about this trauma.

Murcia (Spain) and New Zealand did not ask about this trauma.

Belgium, Bulgaria, China, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Lebanon, the Netherlands, Nigeria, South Africa, Spain and Ukraine did not ask about this trauma.

The second most commonly reported TE was witnessing death, a dead body or someone seriously injured (23.7%; IQR = 18.0–27.3%) and represented 16.8% of all instances of TE exposure. It should be noted that the calculation of the proportion of all TE exposures considers not only the proportion of respondents ever experiencing each TE type but also how many times each type occurred. This explains why witnessing death, which occurred to fewer people than unexpected death of a loved one (23.7% v. 31.4%), nonetheless accounted for a similar proportion of all instances of TE exposures (16.8% v. 16.5%).

The next most common TE types were being mugged (14.5%, IQR = 6.5–18.3%) and life-threatening automobile accidents (14.0%, IQR = 9.3–16.3%), which accounted for 7.4 and 6.1%, respectively, of all instances of TE exposure. Only one other TE, life-threatening illness or injury, accounted for as much as 5% of all instances of TE exposure. These five most common TEs accounted for 51.9% of all instances of TE exposure across countries.

Predictors of TE exposure

Sociodemographic predictors

We examined predictors of TE exposure for each of the 29 TEs both separately and pooled across the five factors. Only the pooled models plus models for the three individual cross-loading TEs are shown in Table 4, although we comment briefly on TE-specific deviations from these aggregate results. Females were more likely than males to be exposed to intimate partner/sexual violence (OR = 2.3) and to the unexpected death of a loved one (OR = 1.1), with the latter a small but statistically reliable effect. On the other hand, females were less likely than males to be exposed to TEs from the other four factors (ORs = 0.4–0.8). Two specific events deviated from these aggregate results: females had greater odds of being a refugee and of having a child with a serious illness. Being a civilian in a war zone, having a life-threatening illness and experiencing a self-nominated other TE had no association with gender.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of sociodemographic variables and prior traumatic events predicting event categories in 26 WMH surveys from 24 countriesa

| Predictor | Collective violence |

Cause/witness bodily harm |

Interpersonal violence |

Intimate partner/ sexual violence |

Accidents or injuries |

Death of loved one |

Mugged with weapon |

Man-made disaster |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 0.8 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.4 (0.4–0.4)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.8)* | 2.3 (2.2–2.4)* | 0.7 (0.7–0.7)* | 1.1 (1.1–1.2)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.5)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.7)* |

| Age at interview | 18–34 years old | 0.3 (0.3–0.3)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.8 (1.6–1.9)* | 3.3 (3.0–3.5)* | 1.8 (1.7–1.9)* | 3.8 (3.5–4.1)* | 5.2 (4.6–6.0)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

| 35–49 years old | 0.4 (0.3–0.4)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.8 (1.6–2.0)* | 2.3 (2.1–2.5)* | 1.3 (1.3–1.4)* | 2.1 (2.0–2.3)* | 2.8 (2.5–3.2)* | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | |

| 50–64 years old | 0.4 (0.4–0.5)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7)* | 1.8 (1.6–1.9)* | 1.2 (1.2–1.3)* | 1.6 (1.5–1.7)* | 1.9 (1.7–2.2)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | |

| 65+ years old (ref) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | |

| Student | Student (v. not) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)* | 1.2 (1.2–1.3)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.7 (1.6–1.9)* | 1.6 (1.4–1.8)* | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Time-varying education | Low education | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)* | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)* | 0.8 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

| Low-average | 0.6 (0.6–0.7)* | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.6)* | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)* | 1.3 (1.3–1.4)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | |

| High-average | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.2)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | |

| High (ref) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | |

| Time-varying marital status | Never married (ref) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

| Previously | 0.8 (0.7–1.0)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.8)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) | |

| Currently married | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.9 (0.8–0.9)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.6 (0.6–0.7)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | |

| Prior trauma type count | Collective violence | 1.8 (1.6–2.1)* | 1.6 (1.5–1.8)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.3)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)* | 2.1 (1.8–2.5)* |

| Cause/witness harm | 1.7 (1.6–1.9)* | 1.7 (1.6–1.8)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)* | 1.5 (1.4–1.6)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)* | 1.3 (1.3–1.4)* | 1.8 (1.7–1.9)* | 1.9 (1.6–2.2)* | |

| Interpersonal violence | 1.5 (1.4–1.7)* | 1.6 (1.6–1.7)* | 2.6 (2.4–2.8)* | 2.2 (2.1–2.3)* | 1.4 (1.4–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.4–1.5)* | 1.6 (1.5–1.7)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.5)* | |

| Sexual violence | 1.3 (1.2–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)* | 1.5 (1.4–1.7)* | 1.7 (1.6–1.8)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.4)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.5 (1.4–1.6)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.7)* | |

| Accident/injuries | 1.4 (1.2–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.4–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.4–1.5)* | 1.5 (1.4–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)* | 1.5 (1.4–1.6)* | 1.9 (1.6–2.2)* | |

| Death of loved one | 1.1 (1.0–1.3)* | 1.3 (1.3–1.4)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.2 (1.2–1.3)* | 1.3 (1.3–1.5)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)* | ||

| Mugged | 1.7 (1.5–2.0)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)* | 1.5 (1.2–1.8)* | ||

| Man-made disaster | 1.4 (1.2–1.8)* | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.2 (1.2–1.3)* | 1.2 (1.1–1.4)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)* | ||

| Country | USA (ref) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

| Mexico | 0.6 (0.5–0.9)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 1.7 (1.5–1.9)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 1.7 (1.5–2.0)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.7)* | |

| Colombia | 2.3 (1.8–2.9)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.7 (1.5–1.9)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 2.4 (2.1–2.8)* | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| Nigeria | 3.8 (3.0–4.9)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.4 (0.4–0.5)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.2 (0.1–0.4)* | |

| China | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.2 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |

| Japan | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.4 (0.4–0.5)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.1 (0.1–0.2)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.5)* | |

| Israel | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.7)* | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | |

| Lebanon | 20.6 (16.6–25.5)* | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.2 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| Ukraine | 2.6 (2.0–3.2)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 1.6 (1.1–2.2)* | |

| New Zealand | 1.6 (1.3–2.0)* | 0.9 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)* | 0.7 (0.5–0.8)* | |

| South Africa | 2.9 (2.2–3.7)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.6 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.8)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8)* | |

| Romania | 0.6 (0.4–0.8)* | 0.4 (0.4–0.5)* | 0.4 (0.3–0.5)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.6 (0.6–0.7)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.4 (0.2–0.6)* | |

| Bulgaria | 0.1 (0.0–0.1)* | 0.2 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.1 (0.0–0.1)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.3 (0.3–0.4)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.1 (0.1–0.2)* | 0.2 (0.2–0.4)* | |

| Brazil | 0.3 (0.2–0.5)* | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)* | 1.4 (1.2–1.5)* | 0.4 (0.4–0.4)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 2.7 (2.4–3.1)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | |

| Belgium | 3.1 (2.2–4.2)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 0.7 (0.5–1.0)* | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | |

| France | 2.0 (1.5–2.6)* | 1.2 (1.0–1.4)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | |

| Spain | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.2 (0.1–0.2)* | 0.2 (0.2–0.3)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)* | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Germany | 2.7 (2.1–3.5)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 0.4 (0.3–0.5)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | |

| Netherlands | 2.6 (1.9–3.5)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | |

| Italy | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2)* | 0.3 (0.3–0.4)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)* | 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* | 0.5 (0.3–0.7)* | |

| Northern Ireland | 4.0 (3.3–4.9)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.4 (0.3–0.4)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |

| Portugal | 1.4 (1.1–1.9)* | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)* | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | |

| Peru | 1.5 (1.2–1.9)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 2.2 (2.0–2.5)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)* | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)* | 1.5 (1.3–1.7)* | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | |

| Medellin, Colombia | 2.3 (1.7–3.1)* | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.8 (0.6–0.9)* | 2.3 (2.0–2.7)* | 0.4 (0.3–0.7)* | |

| Murcia, Spain | 0.5 (0.3–1.0)* | 0.2 (0.1–0.2)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.8)* | 0.4 (0.3–0.5)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.9)* | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | |

| Australia | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.9 (0.8–1.0)* | 0.9 (0.8–0.9)* | 0.7 (0.6–0.7)* | 0.8 (0.7–0.9)* | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)* | 0.8 (0.6–1.0)* |

Data are given as odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

WMH, World Mental Health; ref, reference.

Model includes country, person-year, gender, age at interview, time-varying education, time-varying marital status, and counts of prior event types.

p < 0.05.

Married respondents had reduced odds, compared with the never married, of all TE factors (ORs = 0.5–0.9) except accidents/injuries (OR = 1.0). Two specific TEs deviated from these aggregate results: married respondents had greater odds of being beaten up by a spouse or romantic partner (OR = 1.7) and of having a child with a serious illness (OR = 2.4). Previously married respondents, in comparison with those never married, had lower odds of exposure to collective violence and causing/witnessing bodily harm (OR = 0.8–0.9), but elevated odds of unexpected death of a loved one (OR = 1.2), interpersonal violence (OR = 1.4) and sexual violence (OR = 1.3). Importantly, these associations are based on models that adjust for age of occurrence, such that the high odds of exposure among the never married are not due to age effects.

Regarding cohort effects, compared with respondents aged 65 years or older, all three of the younger cohorts had lower odds of exposure to collective violence but higher odds of interpersonal violence, sexual violence, accidents/injuries, unexpected death of a loved one and being mugged. Only the youngest cohort had increased odds of causing/witnessing bodily harm. These ORs ranged from 1.3 to 5.2 and generally decreased with increasing age. The odds for each individual TE were very consistent with the aggregate results. Only natural disasters, being beaten up by a caregiver, and having purposefully injured or killed were unrelated to cohort.

Being a student was associated with reduced odds of exposure to collective violence (OR = 0.8), but elevated odds of exposure to TEs in each of the other factors (ORs = 1.2–1.7). Two specific TEs deviated from these aggregate results: students had reduced odds of a life-threatening illness (OR = 0.9) and a child with a serious illness (OR = 0.3). Student status was not associated with 15 of the 29 TEs.

In general, education was inversely associated with causing/witnessing bodily harm, experiencing interpersonal violence, having accidents/injuries and the unexpected death of a loved one, but positively associated with exposure to collective violence and being mugged. Automobile accidents deviated from the aggregate results for injuries/accidents, in that education was positively associated with automobile accidents (OR = 1.1). Sexual violence was not associated with education in the aggregate, as the individual events within this factor had opposing odds, i.e. education was inversely associated with being raped, beaten up by a spouse or romantic partner, or stalked (ORs = 0.4–0.8), but positively associated with sexual assault, a private or other TE, or a TE to a loved one (ORs = 1.2–1.7).

Prior trauma exposure

The mean number of lifetime TE exposures was 3.2 in the total sample (IQR = 2.2–3.7) and 4.6 among those with any TE exposure (IQR = 3.5–4.7). At the aggregate level, temporally primary TEs in all five factors as well as the three separate TEs were positively associated with subsequent exposure to TEs in all five factors and the other three separate TEs, the only exception being no association between being mugged and subsequent interpersonal violence. The strength of these associations varied across events. The strongest associations in the aggregate were temporally primary exposure to TEs related to collective violence with subsequent man-made disaster (OR = 2.1), and temporally primary TEs related to interpersonal violence with subsequent exposure to other traumas in the same group (OR = 2.6) as well as with traumas in the sexual violence group (OR = 2.2). For individual TEs, there were significant associations for traumas within the same factor as well as across factors, though the associations across factors were smaller in magnitude.

Discussion

Study limitations

These results must be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, since retrospective reports may underestimate reports of TEs, especially those encountered early in life (Fergusson et al. 2000; Hardt & Rutter, 2004) and emotionally charged (Depue et al. 2007), some recall bias is inevitable. A review of the literature on the validity of retrospective reports of childhood abuse indicates that false negatives are common and false positives are rare (Hardt & Rutter, 2004), suggesting that our estimates are likely to be conservative. One would expect this to be true for other stigmatizing events as well.

Second, response rates varied across surveys, and while weights were utilized to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and to match samples with population sociodemographic distributions in all countries, the effect of non-response on rates of TE exposure is unknown. Furthermore, there may be cultural differences in willingness to disclose sensitive information. We attempted to minimize under-reporting of sensitive information by including an option to report an unspecified private event. The private event accounted for 1.2–2.1% of all TEs worldwide, with an IQR between countries of 3.5–5.8%. The narrowness of this range provides indirect evidence that cultural differences in disclosing stigmatizing TEs were not substantial. However, the possibility of cross-cultural differences in the willingness even to acknowledge a private event cannot be excluded. Bulgaria, in particular, had low rates of all TEs, and yet the private event in Bulgaria accounted for a greater proportion of all events (3.3%) than any other country (except Japan), suggesting that under-reporting of stigmatizing TEs may account for low rates in this country.

The observational nature of the study precludes conclusions regarding causality. Support for directionality was bolstered by the use of discrete-time survival models based on self-reported ages of onset to determine temporally prior TE exposure and other time-varying characteristics, such as marital status. Nevertheless, associations may have been due to some third, unmeasured, common cause. Furthermore, due to the number of multiple comparisons we focus on overall patterns and suggest caution when interpreting individual associations.

Finally, because these surveys were conducted prior to the publication of DSM-5, the TEs included correspond to the DSM-IV definition which is somewhat broader than DSM-5; DSM-5 excludes non-violent indirect exposure such as the non-violent unexpected death of a loved one. Thus, the overall prevalence of TEs may be higher than if we had used the DSM-5 definition. Our measurement of a greater number of different TEs than most prior studies should accordingly lead to higher estimates.

Study strengths and noteworthy findings

Notwithstanding these limitations, the WMH Surveys have significant strengths. We evaluated a wide array of TEs in a large general population sample from 24 countries across six continents, making the results widely representative. Additionally, we evaluated the NOE to each TE in order to estimate each TE type as a proportion of all TE exposures. We found four noteworthy results. First, exposure to TEs is a common experience worldwide, with over two-thirds of individuals reporting a lifetime TE. Second, a small number of TEs account for a large proportion of all TE exposure. Five TEs – witnessing death or serious injury, experiencing the unexpected death of loved one, being mugged, being in a life-threatening automobile accident, and experiencing a life-threatening illness or injury – accounted for over half of all instances of trauma exposure, a pattern that is consistent across countries. Third, TE exposure does not occur randomly in the population. The rate and type of TEs to which individuals are exposed varies according to country of residence, sociodemographic characteristics and history of prior TE exposure. However, rather than identifying a particular group of vulnerable individuals, the findings paint a more nuanced picture wherein most people experience TEs whose form is influenced by individual life circumstances. Fourth, TE exposure increases risk of subsequent exposure, although the strength of association differs by type of TE.

Our finding that TE exposure is common is consistent with previous reports from developed countries (Breslau et al. 1998; Ogle et al. 2014). However, we address one of the more serious gaps in the literature to date, the lack of even basic descriptive data on a wide range of TE exposure in developing countries.

Our findings are strengthened by the uniform measurement across countries. This is particularly relevant for sexual violence as question wording and operationalization is known to make an impact on estimates of sexual violence (Fisher, 2009). Varying prevalence rates across countries are probably due to a combination of true differences, cultural willingness to disclose, and cultural differences in labeling an experience as ‘rape’ or ‘unwanted/inappropriate sexual contact’ due to differences in perceptions of autonomy over one’s body or right to deny sexual advances. Our finding that sexual violence is reported most often in Australia, New Zealand and the USA, which is consistent with two recent publications (Stoltenborgh et al. 2011; Abrahams et al. 2014), may very well be due to this latter explanation.

We found that identification of vulnerable groups is more complex than previously reported in the literature. In contrast to Hatch & Dohrenwend (2007), who reported greater TE exposure for disadvantaged groups in general and for the less educated in particular in the USA, we found that the relationship between education and exposure varies by TE type. Those with less education had increased risk compared with others in the same country of causing/witnessing bodily harm (perhaps because they are more likely to enlist in military service), experiencing interpersonal violence, and having accidents and injuries, but less exposure than others in the same country to collective violence. Those with more education had more automobile accidents, greater odds of being sexually assaulted, but fewer cases of being raped. The reason for this latter finding is unclear.

The most consistent, less nuanced finding is that being married is protective against most TE exposure. Given that our classification of being married did not include cohabitating couples in a marriage-like relationship, our estimates are likely to be conservative. Married people may spend less time outside the home, at later hours, unaccompanied, and in potentially vulnerable situations (such as parties or bars) than those never married. Consistent with this explanation, a survey conducted in 17 industrialized countries found that single individuals had double the risk of contact crime, and those who went out more frequently were 20% more vulnerable to crime (Van Kesteren et al. 2000). Additionally, married individuals may have more resources and consequently face fewer stressors such as living in unsafe communities than unmarried individuals. In our study, being married carried greater odds for being beaten up by a spouse/romantic partner and having a child with a serious illness, presumably because married people are more likely to have a spouse/partner or child in the first place.

Given the nearly omnipresent nature of TE exposure, no obvious single vulnerable group emerges for interventions. Rather, limited resources may need to be dedicated to those segments of the population that are more likely to be exposed to multiple TEs. While most TE types were associated with subsequent TE exposure, the magnitude of those associations varied; the strongest associations were for interpersonal violence predicting subsequent interpersonal and sexual violence, confirming and expanding upon previous studies of revictimization (Rich et al. 2005; Testa et al. 2007). There are different plausible explanations for these associations. On the one hand, psychological consequences of being victimized may increase vulnerability to future TEs via a selection bias for victimization. For example, it has been suggested that perpetrators prey on those who are psychologically vulnerable, i.e. have low self-esteem, are socially isolated or feel powerless (Grauerholz, 2000). There is also evidence that psychological numbing and risky behaviors resulting from childhood sexual abuse may contribute to the risk for revictimization due to decreased ability to respond assertively to unwanted sexual advances (Ullman et al. 2009). On the other hand, prior TEs may be associated with subsequent TEs due to some characteristic of the person or environment. Individual traits such as impulsivity or risk taking, or individual behaviors such as alcohol use, are likely to increase the risk for multiple TEs such as accidents/injuries and relationship violence (Vingilis & Wilk, 2007; Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Bogstrand et al. 2012). Living in a high-crime neighborhood is likely to increase the risk of being mugged or sexually assaulted, whereas living in a conflict zone may increase the likelihood of seeing a dead body, witnessing atrocities and experiencing the unexpected death of a loved one.

Implications for research and practice

That TE exposure is very common provides further evidence that experiencing a TE is not outside the normal range of human experience. This leads to several important questions for further research such as which TEs or combination of TEs are most likely to have deleterious consequences on mental and physical health. Most importantly, further research is needed to understand the mechanisms that account for the associations of prior TEs with subsequent TEs in order to determine what, if any, interventions might help prevent revictimization. In terms of preventing exposure, our findings show that five events account for the largest burden of TE exposure and thus targeting these may contribute to greater reduction in overall exposure. Given that there are differing strengths in association between types of TE and risk for subsequent exposure, targeting TE types which have greater risk for contributing to re-exposure may also be beneficial to reduce burden. Early family-based interventions may be the most helpful given that interpersonal violence, comprised mostly of childhood events, had the strongest risk for experiencing subsequent TEs.

Acknowledgments

The WHO WMH Survey Initiative is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884 and R01 MH093612-01), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. A complete list of all within-country and cross-national WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/

We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centers for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis and Dr Mark Van Ommeren for his thoughtful comments on the draft.

Funding and other sources of support for the individual country surveys

Australia

Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

Brazil

São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey: State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3.

Bulgaria

Bulgarian Epidemiological Study of Common Mental Disorders (EPIBUL): Ministry of Health and the National Center for Public Health Protection.

Colombia

Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH): Ministry of Social Protection.

Medellin, Colombia

Mental Health Study Medellín: Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health (CES University) and the Secretary of Health of Medellín.

European countries

European Study of the Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders (ESEMED): European Commission (contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123 and EAHC 20081308), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), other local agencies, and an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Israel

Israel National Health Survey: Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel.

Japan

WMH Japan Survey: grants H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026 and H16-KOKORO-013 from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Lebanon

Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (L.E.B.A.N. O.N.): Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), National Institute of Health/Fogarty International Center (R03 TW006481-01), Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Award for Medical Sciences, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, and unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Glaxo-SmithKline, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Novartis and Servier.

Mexico

Mexico National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS): National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544-H), with supplemental support from the PAHO.

New Zealand

Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS): New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council and the Health Research Council.

Nigeria

Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW): WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria) and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health: Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency.

People’s Republic of China

Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative: Pfizer Foundation.

Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China

Shenzhen Mental Health Survey: Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information.

Peru

Peruvian World Mental Health Study: National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru.

Poland

Polish project Epidemiology of Mental Health and Access to Care – EZOP Poland: Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in Warsaw, Department of Psychiatry – Medical University in Wroclaw, National Institute of Public Health-National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw, Psykiatrist Institut Vinderen –Universitet, Oslo, Norwegian Financial Mechanism, European Economic Area Mechanism, and Polish Ministry of Health.

Portugal

Portuguese Mental Health Study: Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, NOVA University of Lisbon, Portuguese Catholic University, Champalimaud Foundation, Gulbenkian Foundation, Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and Ministry of Health.

Romania

Romania WMH Study: National School of Public Health & Health Services Management; technical support from Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics – National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC. Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands; funded by the Ministry of Public Health with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL.

South Africa

South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH): US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan; D.J.S. is supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) of South Africa.

Murcia, Spain

Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain – Murcia (PEGASUS-Murcia) Project: Regional Health Authorities of Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud and Consejería de Sanidad y Política Social) and Fundación para la Formación e Investigación Sanitarias (FFIS) of Murcia.

Ukraine

National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905).

USA

US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): NIMH (U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the NIDA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. K.A.M. also received funding from the NIMH (K01-MH092526).

Footnotes

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981

Declaration of Interest

In the past 3 years, R.C.K. has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention and Sonofi-Aventis Groupe. R.C.K. has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute and US Preventive Medicine. R.C.K. owns a 25% share in DataStat, Inc. In the past 3 years, D.J.S. has received research grants and/or consultancy honoraria from AMBRF, Biocodex, Cipla, Lundbeck, National Responsible Gambling Foundation, Novartis, Servier and Sun. D.J.S. is supported by the MRC of South Africa. None of the other authors has any conflicts to declare.

References

- Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, Pallitto C, Petzold M, Shamu S, García Moreno C. Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic review. Lancet. 2014;383:1648–1654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J, Chatterji S, He Y. The Burdens of Mental Disorders: Global Perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bogstrand ST, Gjerde H, Normann PT, Rossow I, Ekeber O. Alcohol, psychoactive substances and non-fatal road traffic accidents – a case–control study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:734. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung WS, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358:450–454. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault I, Herbert M, McDuff P. Men’s and women’s childhood sexual abuse and victimization in adult partner relationships: a study of risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue BE, Curran T, Banich MT. Prefrontal regions orchestrate suppression of emotional memories via a two-phase process. Science. 2007;317:215–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1139560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Woodward LJ. The stability of child abuse reports: a longitudinal study of young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:529–544. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS. The effects of survey question wording on rape estimates: evidence from a quasi-experimental design. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:133–147. doi: 10.1177/1077801208329391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, McNally RJ, Ursano RJ, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauerholz L. An ecological approach to understanding sexual revictimization: linking personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors and processes. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:5–17. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;24:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness J, Pennell BE, Villar A, Gebler N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bilgen I. Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. In: Kessler RC, Ustun B, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: a review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40:313–332. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wells JE, Hubbard F, Mneimneh ZN, Chiu WT, Sampson NA, Berglund PA. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler RC, Ustun B, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp U, Gamma A, Milos G, Eich D, Ajdacic Gross V, Rossler W, Angst J, Schnyder U. Prevalence of exposure to potentially traumatic events and PTSD: the Zurich Cohort Study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256:151–158. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert HK, Hyder AA, Butchart A, Norton R. Global health: injuries and violence. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2011;25:653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun B. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Demmer RT, Cerdá M, Koenen KC, Uddin M, Galea S. Potentially traumatic events and the risk of six physical health conditions in a population-based sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:451–460. doi: 10.1002/da.22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Ono Y. Suicide: Global Perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Means-Christensen AJ, Craske MG, Sherbourne CD, Roy-Byrne PP, Stein MB. Associations between psychological trauma and physical illness in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:461–470. doi: 10.1002/jts.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Special populations: trauma epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. Cumulative exposure to traumatic events in older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2014;18:316–325. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.832730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell BE, Mneimneh ZN, Bowers A, Chardoul S, Welles JE, Viana MC, Dinkelmann K, Gebler N, Florescu S, He Y, Huang Y, Tomov T, Vilagut G. Implementation of the World Mental Health Surveys Initiative. In: Kessler RC, Ustun B, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Loh C, Weiland P. Child and adolescent abuse and subsequent victimization: a prospective study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:1373–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.3. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Koenen KC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Iwata N, Levinson D, Lim CC, Murphy S, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Kessler RC. Associations between lifetime traumatic events and subsequent chronic physical conditions: a cross-national, cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer C, Barnow S, Volzke H, John U, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and physical illness: findings from the general population. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:1012–1017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc76b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo NS, Breslau N. Early childhood behavior trajectories and the likelihood of experiencing a traumatic event and PTSD by young adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0446-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston J. Prospective prediction of women’s sexual victimization by intimate and nonintimate male perpetrators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:52–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. [Accessed September 2015];Countries and Economies. 2015 ( http://data.worldbank.org/country)

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime traumas and mental health: the significance of cumulative adversity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ, Filipas HH. Child sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use: predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2009;18:367–385. doi: 10.1080/10538710903035263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kesteren JN, Mayhew P, Nieuwbeerta P. Criminal Victimisation in Seventeen Industrialised Countries: Key Findings from the 2000 International Crime Victims Survey. The Hague Ministry of Justice WODC; The Hague: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis E, Wilk P. Predictors of motor vehicle collision injuries among a nationally representative sample of Canadians. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2007;8:411–418. doi: 10.1080/15389580701626202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser E, Pijl YJ, Stolk RP, Neeleman J, Rosmalen JGM. Accident proneness, does it exist? A review and meta-analysis. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff MR, Scott KM, Gureje O. Global Perspectives on Mental–Physical Comorbidity in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]