Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Ovarian transposition (OT) is offered to reproductive age women with cervical cancer (CC) to preserve fertility prior to pelvic radiation. The aim of this study was to assess subsequent utilization of fertility treatment in these patients.

STUDY DESIGN

This is a case series of 216 cervical cancer patients seen in a comprehensive cancer center. 16 patients underwent OT for fertility preservation prior to pelvic radiation. Patients were assessed for utilization of fertility treatment, FSH levels as a measure of ovarian reserve, and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-cervix cancer (FACT-CX) to assess quality of life after OT.

RESULTS

94% of patients maintained regular menstrual cycles three years after OT surgery (15/16). When measured (n=5) serum FSH was normal at baseline, and showed a transient elevation at three months following chemoradiation, with a return to normal levels at six months (Means 6.33±2.94, 48.44±18.63, 12.52±8.25, mIU/ML respectively). Only one patient in this series attempted fertility treatment (in vitro fertilization) following OT, and did not become pregnant. FACT-CX indicated that quality of life did not change significantly over the six months’ duration following OT and chemoradiation therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

OT preserves menstrual cycle regularity without negatively impacting patients’ quality of life. The utility of OT as an effective fertility preservation option is hampered by the low utilization rate of in vitro fertilization and lack of ovarian reserve assessment following OT.

Keywords: Fertility preservation, ovarian transposition, ovary, cervical cancer, pelvic radiotherapy

Introduction

The major improvements in fertility preservation strategies in women warrants closer look at fertility outcome in young reproductive age women with newly diagnosed cervical cancer (CC) [1, 2]. CC continues to be a major health problem worldwide despite cervical screening and HPV vaccination [3, 4]. The vast majority of CC patients receive pelvic radiotherapy with concomitant neoadjuvant cisplatin chemosensitization [5]. Extended filed pelvic radiation may lead to reproductive loss by causing near-universal ovarian castration and subsequent ovarian failure [6–14]. The most critical factor for radiotherapy-induced ovarian failure is the location and closeness of the ovary to the radiation field. Ovarian radiotoxicity only occurs if the ovaries lie within the field of radiation and/or are exposed to radiation scatter [15]. Ovarian transposition (OT) removes the ovaries from the field of irradiation, thus reducing the rate of radiation exposure to the ovary by approximately 50–90% and preserving ovarian function in CC patients [16–18]. While many authors have reported good success at preserving ovarian endocrine function and menstrual cycle regularities with OT [10, 19], others have shown conflicting results [18, 20–26]. Fertility treatment and pregnancy outcomes following OT in patients with CC have however not been consistently evaluated [18, 20]. Furthermore, the utility of concomitant fertility preservation options such as embryo, oocyte, or ovarian tissue cryopreservation in patients with CC has not been studied.

While many studies have documented the return of menstrual cyclicity with OT prior to pelvic radiotherapy, reports on successful fertility and pregnancy outcomes are rather sparse [22–24, 26, 27]. Whereas resumption of cycle regularity is reassuring in terms of preservation of endocrine ovarian function, it does not necessarily correlate with successful fertility preservation in cancer patients. Chemoradiation impairs in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates as it decreases ovarian reserve and negatively impacts the oocytes by increasing the rate of errors of meiotic nondisjunction [28–31]. This occurs despite normal menstrual cycles, making menstrual cycle regularity an inaccurate measure of fertility success. To further understand fertility success in CC patients, we report on fertility outcome in women with locally-advanced stages 1B to IIB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix (SSC-CX) who underwent OT over five years period. Outcomes assessed in the transposition group include fertility treatment as indicated by utilization of IVF, pregnancy outcomes, endocrine profile as a surrogate marker of ovarian reserve, and assessment of quality of life (QOL) by utilizing the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-cervix cancer (FACT-CX) score [32]. This study highlights the need for guidelines and national registry to evaluate the impact of OT surgery on ovarian reserve and fertility preservation in CC patients.

Materials and methods

We included a retrospective chart review of all CC patients seen in the gynecology oncology clinic at the University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center from September 2002 to February 2008. A total of 216 charts including 16 patients with OT were reviewed. Ovarian reserve as indicated by endocrine assessment of FSH level, utilization of fertility treatment and pregnancy outcomes, QOL, and ovarian metastasis were assessed in all transposition patients when available. The University of Wisconsin health sciences institutional review board approved this research protocol. Chart review was exempted from informed consent.

This retrospective study included data from four patients who were recruited as part of a prospective cohort study that was conducted in the same period. Patients aged 40 or younger with normal ovarian function and newly diagnosed SCC-CX, stages 1B-IIB, who wished to preserve ovarian function were prospectively recruited. All enrolled study subjects had regular menstrual periods, normal baseline serum FSH, and normal lower uterine segment on MRI/PET scan. These subjects underwent laparoscopic right ovarian transposition/oophoropexy with left salpingoophorectomy and right salpingectomy prior to chemoradiation therapy. The left ovary and both fallopian tubes were examined in the pathology lab to rule out metastatic disease. Following surgery, all the study subjects received pelvis radiotherapy and barchytherapy with concomitant cisplatin chemotherapy. Patients were followed prospectively for six months. Serum FSH, estradiol, and testosterone levels were collected preoperatively and three and six months postoperatively, FACT-CX was obtained at baseline and 6 months later, and metastasis to contralateral ovary and tubes was assessed. All human participants in the study group gave written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Because of the poor accrual rate for the study (n=4), the study was discontinued due to low patients’ accrual, and a retrospective review of this group was included in the current report.

Statistical analysis

We summarized the data by standard descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, and range) for variables on a continuous scale, and frequency tables for variables on a categorical scale. Some components in FACT-CX survey scores were reverse-scored so that higher scores indicate greater well-being. Comparison studies were not performed due to the lack of endocrine test results and QOL assessment in the data that was retrospectively collected and in patients who did not undergo OT.

Results

General demographics of ovarian transposition patients

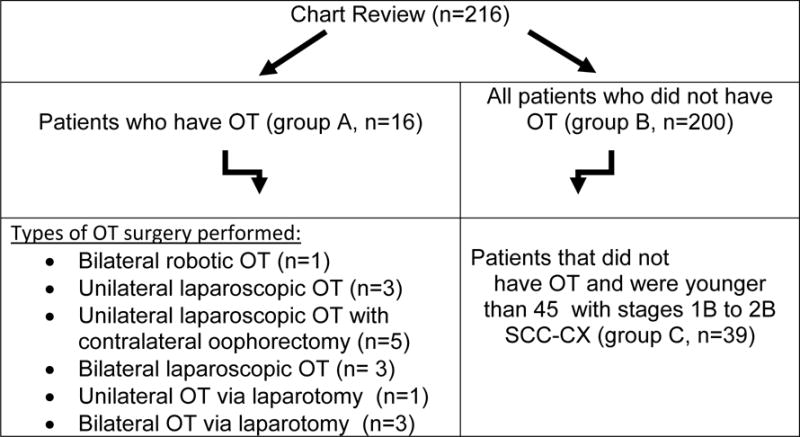

Patients were stratified in three groups according to OT surgery and age (Figure. 1). Group A consisted of 16 patients who underwent OT, group B consisted of 200 patients that did not undergo OT, and group C consisted of a sub-cohort of 39 reproductive age patients did not receive OT surgery (Figure. 1). Table 1 represents the descriptive statistics of patients in the study. Of the 216 charts reviewed, 72% of the patients had stages 1B to IIB SCC-CX. The age of the patients treated with OT ranged between 22 and 51. The interval between CC diagnosis and OT surgery was 19.85±14.7 days, and between CC diagnosis and radiotherapy was 36.4±15.58 days in the transposition patients (Table 1A, group A); while the time lapse was 59.3±83.1 and 51.16± 56.33 respectively in the non-transposition patients (Table 1A, group B). Considering all patients younger than 45 years, who were candidates for fertility preservation, the mean age for patients who underwent OT (groups A, Table 1A) was 32.81±7.45 and for patients that did not undergo OT (group C, Table 1B) was 37.7±5.54 years. The mean parity for the two groups was 2.13±2.31 and 2.14±1.29 respectively (groups A and C, Tables 1A and 1B). As expected, the maximum dose of radiotherapy to the transposed ovary was significantly lower than the non-transposed ovary (3.62± 4.58 vs.47.96±2.18 cGy, Table 1A).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for the subjects included in the study. OT: ovarian transposition, CC: cervical cancer, SSC-CX: squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and type of surgery.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of different groups of patients in the study; Table 1A show the baseline characteristics of all patients included in the study. A total of 216 charts were reviewed. 16 (7%) has ovarian transposition (group A) and 200 (93%) constitue the non-transposition group (group B). Table 1B shows baseline demographics of a sub-group of patients (group C), aged 45 years or younger with stages 1B–2B squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix that did not undergo ovarian transposition. There were 39 patients in this sub-group with an overall utilization rate of 29% for OT. BMI = body mass index.

| A | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Transposition patients (group A) | Non-Transposition group (all patients, group B) | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

| Transposition (yes/no) | 16 | – | – | – | – | – | 200 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age | 16 | 32.81 | 31.5 | 7.45 | 22 | 51 | 199 | 48.17 | 46 | 13.99 | 22 | 80 |

| Calculated_BMI_M/Kg2 | 15 | 26.55 | 24.9 | 6.23 | 19.78 | 40.2 | 174 | 28.26 | 26.91 | 7.75 | 14.5 | 67.1 |

| Gravity | 16 | 2.81 | 2 | 2.79 | 0 | 9 | 187 | 2.77 | 2 | 2.23 | 0 | 13 |

| Parity | 16 | 2.13 | 1.5 | 2.31 | 0 | 7 | 186 | 2.28 | 2 | 1.9 | 0 | 12 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Diag_Surg (days) | 16 | 19.06 | 13.5 | 14.7 | 0 | 54 | 71 | 59.3 | 34 | 83.12 | 4 | 587 |

| Diag_RXT (days) | 15 | 36.4 | 37 | 15.6 | 14 | 67 | 81 | 51.16 | 44 | 56.33 | 2 | 434 |

| Delay_Surg (days) | 13 | 19.85 | 19 | 13.5 | 5 | 49 | 12 | 90.05 | 42 | 183.5 | 12 | 671 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Dose_Brachytherapy | 12 | 25.1 | 26.25 | 4.06 | 15.75 | 30 | 83 | 25.59 | 26.25 | 4.75 | 9.75 | 40 |

| Dose_EXT_BEAM | 14 | 47.19 | 45 | 3.17 | 45 | 54 | 77 | 50.09 | 50.4 | 6.32 | 30 | 67.2 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| RXT_Max_Transposed_Ovary (Group1*) | 14 | 3.62 | 2.11 | 4.58 | 0.5 | 18.4 | N/A | |||||

| RXT_Max_Untransposed_Ovary (Group2*) RXT_Max_Rt. | 9 | 47.96 | 50 | 2.81 | 45 | 50.4 | N/A | |||||

| Untransposed_Ovary (Group3*) RXT_Max_Lt. | N/A | 59 | 48.38 | 50.4 | 6.42 | 25 | 58 | |||||

| Untransposed_Ovary (Group3*) | N/A | 59 | 49.28 | 50.4 | 6.37 | 25 | 58 | |||||

| B | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Non-transposition group (stages 1B-IIB reproductive age patients, group C) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| *Variable | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

| Age | 39 | 37.79 | 39 | 5.54 | 22 | 45 |

| Calculated_BMI_M/Kg2 | 37 | 28.93 | 9.74 | 9.06 | 17.25 | 67.14 |

| Gravity | 35 | 2.8 | 3 | 1.45 | 0 | 5 |

| Parity | 35 | 2.14 | 3 | 1.29 | 0 | 4 |

Underutilization of OT in reproductive age women with cervical cancer

OT is offered to less than one third of qualified patients reviewed. Figure 1 shows the different groups of patients enrolled in the study. Of the total 216 charts reviewed, 16 patients had OT (Figure 1, group A) and 200 did not (Figure 1, group B). Of those patients that did not have OT, thirty-nine patients were younger than 45 years old and had stages 1B to IIB SSC-CX but did not undergo OT (Figure 1, group C). In essence, this group (group C patients) represents a sub-group of young patients with who qualify for LOT to preserve ovarian function but did not had the procedure done (utilization rate of OT of 16/55, 29%). Those patients were used in lieu of a comparison group.

Lack of consistency in the type of ovarian transposition surgery offered to cervical cancer patients

There was a wide variation in the type of OT surgery performed in the study (Figure 1). Variations were encountered in the number of ovaries transposed (unilaterally versus bilateral), and whether laparoscopy, laparotomy or robotic surgery was used. Four patients underwent unilateral OT of only one ovary; five patients underwent unilateral right OT with contralateral left oophorectomy and bilateral salpingectomy to assess for metastasis; and seven patients underwent bilateral ovarian transposition. The surgical context of OT procedure in these patients was as follows: nine patients underwent elective LOT prior to radiotherapy; two patients underwent elective LOT with sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by an interval radical hysterectomy (but did not receive post-operative radiotherapy); four patients underwent OT with aborted radical hysterectomy due to positive lymph nodes; and one patient had robotic OT with trachelectomy. More importantly, elective LOT was successfully completed in all eleven patients consented for the procedure and there was no immediate morbidity from laparoscopic surgery.

Reproductive outcome and quality of life in cervical cancer patients undergoing ovarian transposition

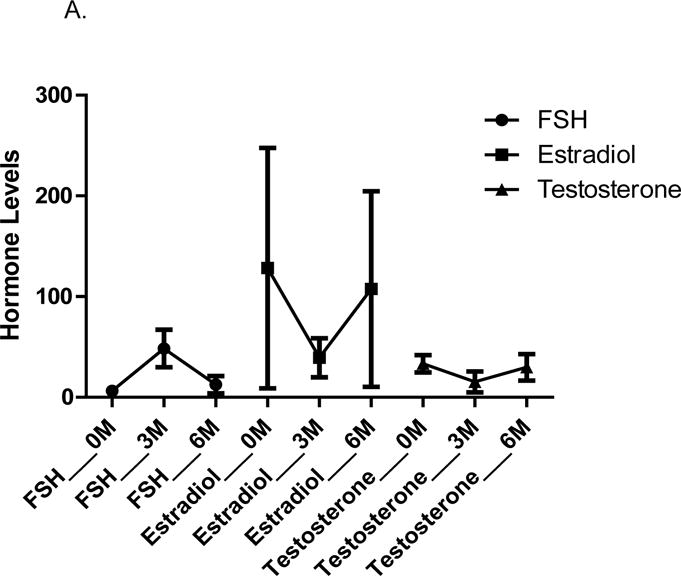

Long term complications of OT in this case series included one case of amenorrhea secondary to premature ovarian failure after drop of the transposed ovary to the pelvis during radiotherapy, one case of ovarian cyst, and one case of ovarian pain at the site of transposition. None of the patients studied in this series (except for one) have attempted and/or achieved fertility following OT. The one patient who attempted fertility via an IVF procedure after unilateral LOT had her IVF cycle canceled due to failure of ovarian stimulation of the transposed ovary secondary to decreased ovarian reserve. Endocrine profile was available in five patients (Figure 2). Day 3 serum FSH was normal at baseline (mean 6.33±2.94 mIU/ML, figure 2A). Following radiotherapy, there was a transient elevation of FSH at three months (mean 48.44±18.63 mIU/ML). This improved over the ensuing period of follow up and normalized (mean of 12.52±8.53 mIU/ML) at six months; three out of the four patients has normal FSH level at 6 months. The 6 months FSH level for the one patient whose transposed ovary dropped in the pelvis during radiotherapy was 18.8mIU compared to a mean of 4.9mIU/ML for the remaining subjects (data not shown). Similarly, serum estrogen and testosterone levels decreased three months after chemoradiation therapy, but normalized six months later. QOL assessment (FACTS-CX score) was only available in four patients that were prospectively followed. Except for sexual arousal, emotional well being, and orgasm, which changed > 5 points, FACT-CX score did not change following treatment and was generally similar to reported historic CC controls (figure 2B) [23, 32].

Fig. 2. Hormone profile and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-cervix cancer (FACT-CX).

Figure 2A is a graph representation of the levels of FSH, testosterone, and estradiol hormone levels (n=5). Hormone levels were measured at zero, three, and six months after LOS. Figure 2B is a graph of the paired FACTS-CX score data of the four study subjects that were enrolled in a concurrent prospective study for six months. FACTS-CX was collected before and six months after LOT. FACT-CX score did not change following treatment except for mild change in sexual arousal, emotional wellbeing, and orgasm. FSH = follicular stimulating hormone.

Ovarian metastasis in cervical cancer patients undergoing ovarian transposition

This study was not powered to assess the risk of ovarian metastasis following LOT. Data on lymph node and ovarian metastasis is summarized in tables 2. Histological lymph node metastasis did not necessarily indicate ovarian metastasis in this limited case series as five patients have evidence of lymph node metastasis and none has ovarian metastasis (Table 2). On the other hand, absence of lymph node metastasis on imaging indicated lack of ovarian metastasis in this series. 100 patients with stages 1B–2B SCC had normal lymph nodes imaging on MRI and/or PET scan. None of those patients who were measureable for histological evaluation had metastasis to the ovary or fallopian tubes (Table 2). In addition, all the prospectively followed four patients who underwent elective LSO to specifically evaluate for metastasis on the contralateral ovary had normal histological examination of the contralateral ovary (data not shown).

Table 2. Lymph node and ovarian metastasis.

Table 2 show the incidence of lymph nodes and ovarian metastasis in stages 1B–2B squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix (no age limit). There were a total of 100 patients with stages 1B–2B squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. 12 (12%) has ovarian transposition and 88 (88%) did not have ovarian transposition. None of 24 patients who have ovarian histology has metastasis. Path = pathology, met = metastasis.

| Transposition | Non–Transposition | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Path_Ovary__Met_ | ||||||

| Negative | 5 | 42 | 19 | 22 | 24 | 24 |

| Not done | 7 | 58 | 69 | 78 | 76 | 76 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

|

| ||||||

| Path_Tubes__Met_ | ||||||

| Negative | 8 | 67 | 19 | 22 | 27 | 27 |

| Not done | 4 | 33 | 69 | 78 | 73 | 73 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

|

| ||||||

| Path__Lymph_node_Met_ | ||||||

| Negative | 1 | 8 | 27 | 31 | 28 | 28 |

| Positive | 5 | 42 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 15 |

| Not done | 6 | 50 | 51 | 58 | 57 | 57 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Discussion

Preservation of ovarian function is a challenge in CC, in particular locally advanced stage 1B to IIB SCC-CX patients treated with pelvic radiotherapy. This is an important group of patients to study since these stages constitute the majority of CC patients (72% in our case series). Here, we present a case series looking at fertility outcome of stages 1B to IIB SCC-CX patients who underwent OT prior to pelvic radiation.

The interval between OT surgery and radiotherapy in our case series was an average of ~3 weeks, eliminating the surgery as a cause of undue delay of CC treatment. The OT procedure complication rates were minimal and comparable to other series [19]. In concordance with other studies, we show underutilization of the procedure as only 28% of eligible reproductive age CC patients underwent OT. To our surprise, we showed a wide variation in the type of OT offered to CC patients, indicating lack of consistent strategy regarding this surgery. While some patients received unilateral OT, others received bilateral OT, and a subgroup underwent contralateral oophorectomy to exclude ovarian metastasis. As expected, the majority of patients were offered laparoscopic procedures (LOT), with less than a third of the patients undergoing laparotomy (4/16). LOT is a safe procedure for patients with locally advanced stages 1B to IIB SCC-CX [25, 33].

Despite preservation of endocrine function and quality of life, fertility preservation and future sucessful pregnancies following OT remains a challenge. Following OT surgery, patients are not candidates for natural conception via whole ovarian re-transplantation to the pelvis as radiation and surgery-induced adhesions in the pelvis typically prohibit ovarian re-transplantation after transposition and also compromise pelvic and uterine blood supply. In addition, fallopian tubes are routinely severed during the transposition procedure [11]. Thus, close follow up and encouragement of these patients to peruse advanced fertility options when desired is recommended. Even, then, these patients face multiple challenges. There are few case reports of sucessful IVF following transabdominal oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer to a gestational carrier resulting in birth in patients who received radiaiton after radical hysterectomy and ovarian transposition [11, 34–36]. Accessibility of the ovary for transabdominal oocyte retrieval must however be assessed prior to IVF as ovarian migration and dislocation can occur following ovarian transposition. The uterine cavity must also be evaluated prior to embryo transfer to exclude uterine synchia and adhesions. Radiotherapy-induced decrease in uterine elasticity and vasculature can lead to implantation failure and pregnancy complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm labor, and growth restriction [6, 34]. The impact of altered ovarian environment and compromised ovarian blood flow on ovarian reserve of the transplanted ovary has not been systematically assessed either and desires future studies, though newer techniques are promising [14].

The role of additional definitive fertility preservation options such as embryo cryopreservation prior to OT in young cancer patients receiving pelvic radiation has not been reported. Oocyte and embryo cryopreservation are clinically approved to preserve fertility in reproductive age women diagnosed with cancer. While this may be an option prior to pelvic radiation in other types of cancers such as hip osteosarcoma, it is not recommended in CC patients due to the increased risk of cancer spread and bleeding from the cervix as a result of transvaginal oocyte retrieval. In our experience, LOT could safely be achieved about three to four weeks following oocyte retrieval for embryo or oocyte cryopreservation for non-cervical cancer patients receiving pelvic radiotherapy. Ultrasound examination to ascertain normal ovarian size prior to proceeding with LOT is a prerequisite for these patients to ensure the return of the ovary to near normal size after ovarian hyperstimulation. With future improvement and optimization of ovarian tissue transplantation and in vitro follicle maturation, it is foreseeable that ovarian tissue cryopreservation could routinely complement OT and be done concomitantly on ovarian tissues removed at the time of OT in young CC patients desiring fertility preservation. Recently, uterine transplantation has been described [37]. This will likely not be an option for CC patients considering the increased risk of radiation-induced vasculopathy in CC patients. Drug-based fertility preservation prior to chemoradiation is being investigated, and could potentially provide a promising option in the future [38, 39].

One main goal of OT is preservation of ovarian endocrine function and quality of life. In CC, the radiation field intensity to the ovaries is high and extends to the pelvic sidewalls. The effect of the concomitant low dose cisplatin chemotherapy used in CC on ovarian function is likely insignificant [36, 40, 41]. To enhance preservation of ovarian endocrine function following OT, the anticipated field of radiation should be evaluated carefully and the ovaries are transposed as far away from the anticipated field of radiation as feasible (adjacent to the liver spleen or kidneys). Utilizing this technique, the median dose of radiation to the transposed ovary in our series was 211 cGy; well below the toxic dose estimated at 300 cGy leading to preservation of endocrine function [19, 26, 42]. OT was associated with regular menstrual cycles in all patients except for one patient, in whom the transposed ovary dropped to the pelvis during radiation therapy. Five patients have hormonal profile assessed. These patients showed transient elevation of FSH at three months and normalization of FSH levels at six months. The transient peak was more pronounced in older patients and pelvic boost radiation was associated with higher FSH.

The impact of LOT on QOL in CC patients was evaluated prior to and six months after surgery. QOL is an assessment of the patients’ self-reported perception of physical, psychosocial, and sexual well-being [43]. QOL is particularly important in CC since patients are frequently young and potentially have an additional life expectancy of 25–30 years after treatment to experience consequences arising from CC and its treatment [34–36, 43]. It is well recognized that QOL is negatively affected by reproductive loss in cancer patients [44]. Using FACT-CX, we showed that our prospectively followed patient cohort with stages IB-IIB cancer of the cervix had minimum change in FACT-CX score six months after LOT and chemoradiation. The outcome in the small number of patients we evaluated was similar to other studies [32].

Stages IB–IIB group represents the majority of CC patients and deserves special consideration. Transposition of the ovary away from the radiation field in this group can only be justified if the risk of microscopic ovarian metastasis is minimum, particularly in the absence of distant disease [45]. The incidence of metastasis ranges from 0.15 – 0.55% for stages A - IIB SSC-CX, and from 1.3 – 3.72% for adenocarcinoma of the cervix [26, 46–52]. This justifies offering OT procedures to carefully selected patients SSC-CX with no evidence of ovarian cancer metastasis. OT should however not be offered to patients with cervical adenocarcinoma due to increased incidence of ovarian metastasis in the later group. The routine use of MRI and/or PET scan has recently added to the radiation oncologist’s armamentarium and ability to anatomically map and target advanced CC. The risk of microscopic ovarian metastasis can be minimized by a multifaceted strategy that includes 1) preoperative MRI and PET scanning to exclude patients with bulky lower uterine segment involvement, 2) limiting the procedure to those patients with squamous cell histology, 3) detailed magnified visualization of the ovaries at the time of surgery to exclude visible disease, 4) transposition of only one ovary, with contralateral oophorectomy and subsequent pathologic evaluation in high risk patients. Continue follow up of OT in Stages IB-IIB CC patients is warranted to further ascertain the risk of OT.

In conclusion, OT in patients with CC undergoing chemoradiation is a feasible procedure that maintains menstrual regularity with no negative impact on quality of life. There is however lack of consistent documentation of ascertainment of ovarian reserve and utilization of IVF following OT surgery. Furthermore, the study highlights major variations in the types of OT surgery performed by various providers. The retrospective nature of this study constitutes a recognizable weakness that could be overcomed by future collaborative national studies. These studies are needed to establish guidelines to standardize the type of OT procedures offered and to set recommendations for long term follow up of ovarian reserve and fertility outcome in these patients. Studies are also needed to evaluate the potential role for additional concomitant fertility preservation options such as ovarian tissue cryopreservation in conjunction with OT in cervical cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin start up funds, Research and Development funds, and Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; and by NIH training grant K12 HD0558941 to SMS.

Abbreviations

- OT

Ovarian transposition

- SCC-CX

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix

- LOT

Laparoscopic ovarian transposition

- FACT-CX

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Cervix Cancer

- QOL

Quality of life

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors have any conflict of interest. All the data used in this manuscript is under our control and we agree to share the data with the Journal to review if requested.

Authors’ contribution

SMS conceived and supervised the project, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. SS performed statistical analysis. SA collected data. KB calculated ovarian radiotherapy doses. DMK and SS provided data for subset of clinical patients.

References

- 1.Varghese AC, et al. Cryopreservation/transplantation of ovarian tissue and in vitro maturation of follicles and oocytes: challenges for fertility preservation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2008;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnez J, et al. Children born after autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. a review of 13 live births. Ann Med. 2011;43(6):437–50. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.546807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeSantis C, Jemal A, Ward E. Disparities in breast cancer prognostic factors by race, insurance status, and education. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1445–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9572-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang G, et al. Definitive extended field intensity-modulated radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin chemosensitization in the treatment of IB2-IIIB cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2014;25(1):14–21. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2014.25.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Critchley HO, Bath LE, W WH. Radiation damage to the uterus Review of the effects of treatment of childhood cancer. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2002;5:61–66. doi: 10.1080/1464727022000198942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen EC, et al. Reduced Ovarian Function in Long-Term Survivors of Radiation- and Chemotherapy-Treated Childhood Cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5307–5314. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace WH, Thomson AB, K TW. The radiosensitivity of the human oocyte. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:117–121. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose PG, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1144–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris M, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1137–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bath LE, et al. Ovarian and uterine characteristics after total body irradiation in childhood and adolescence: response to sex steroid replacement. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:1265–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace WH, et al. Gonadal dysfunction due to cis-platinum. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1989a;17:409–413. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950170510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(18):2917–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eitan R, et al. Laparoscopic adnexal transposition: novel surgical technique. International journal of gynecological cancer: official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2011;21(9):1704–7. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31822fa8a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards BK, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husseinzadeh N, van Aken ML, A B. Ovarian transposition in young patients with invasive cervical cancer receiving radiation therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994 Jan;4(1):61–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1994.04010061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mc CM, Keaty EC, Thompson JD. Conservation of ovarian tissue in the treatment of carcinoma of the cervix with radical surgery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1958;75(3):590–600. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(58)90614-8. discussion 600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney DD, et al. The fate of the ovaries after radical hysterectomy and ovarian transposition. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:3–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers SK, et al. Sequelae of lateral ovarian transposition in irradiated cervical cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991 Jun;20(6):1305–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90242-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson B, et al. Ovarian transposition in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1993 May;49(2):206–14. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.L GS. A laparoscopic technique for lateral oophoropexy to conserve ovarian function prior to abdominopelvic irradiation. Surg Endosc. 1995 Oct;9(10):1144–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00189010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clough KB, et al. Laparoscopic unilateral ovarian transposition prior to irradiation: prospective study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2638–2645. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960615)77:12<2638::AID-CNCR30>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stöckle E, et al. Functional outcome of laparoscopically transposed ovaries in the multidisciplinary treatment of cervical cancers. Analysis of risk factors. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1996;25(3):244–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dursun P, et al. Ovarian transposition for the preservation of ovarian function in young patients with cervical carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(1):13–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahisa J, et al. Laparoscopic ovarian transposition in patients with early cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008 May-Jun;18(3):584–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisharah M, Tulandi T. Laparoscopic preservation of ovarian function: an underused procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:367–370. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prouvost MA, et al. Ovarian transposition with per-celioscopy before curietherapy in stage IA and IB cancer of the uterine cervix. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1991;20(3):361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tease C, Fisher G. Cytogenetic and genetic studies of radiation-induced chromosome damage in mouse oocytes. I. Numerical and structural chromosome anomalies in metaphase II oocytes, pre- and post-implantation embryos. Mutat Res. 1996;349(1):145–53. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Herrera A, Garcia F, Garcia-Caldes M. Radiobiology and reproduction-what can we learn from Mammalian females? Genes (Basel) 2012;3(3):521–44. doi: 10.3390/genes3030521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolmans MM, et al. Efficacy of in vitro fertilization after chemotherapy. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(4):897–901. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das M, et al. Ovarian reserve and response to IVF and in vitro maturation treatment following chemotherapy. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2509–14. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King MT, et al. Meta-analysis provides evidence-based effect sizes for a cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, the FACT-G. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(3):270–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao C, et al. Analysis of the risk factors for the recurrence of cervical cancer following ovarian transposition. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2013;34(2):124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kauppila A, Jouppila P. Effect of high-dose preoperative intracavitary radiotherapy on uterine size and early operability in patients with corpus carcinoma. Strahlentherapie. 1975;149(1):21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giacalone PL, et al. Successful in vitro fertilization-surrogate pregnancy in a patient with ovarian transposition who had undergone chemotherapy and pelvic irradiation. Fertility and sterility. 2001;76(2):388–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01895-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steigrad S, Hacker NF, Kolb B. In vitro fertilization surrogate pregnancy in a patient who underwent radical hysterectomy followed by ovarian transposition, lower abdominal wall radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83(5):1547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brannstrom M, et al. First clinical uterus transplantation trial: a six-month report. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(5):1228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelinski MB, et al. In vivo delivery of FTY720 prevents radiation-induced ovarian failure and infertility in adult female nonhuman primates. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(4):1440–5 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roti Roti EC, Salih SM. Dexrazoxane ameliorates doxorubicin-induced injury in mouse ovarian cells. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(3):96. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.097030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang H, et al. Outcome and reproductive function after cumulative high-dose combination chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) for patients with ovarian endodermal sinus tumor. Gynecologic oncology. 2008;111(1):106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gershenson DM. Menstrual and reproductive function after treatment with combination chemotherapy for malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1988;6(2):270–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terenziani M, et al. Oophoropexy: A relevant role in preservation of ovarian function after pelvic irradiation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):935–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oktay K, Sonmezer M. Ovarian tissue banking for cancer patients: fertility preservation, not just ovarian cryopreservation. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2004;19(3):477–80. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wenzel L, et al. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecologic oncology. 2005;97(2):310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morice P, et al. Ovarian metastasis on transposed ovary in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: report of two cases and surgical implications. Gynecol Oncol. 2001 Dec;83(3):605–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutton GP, et al. Ovarian metastases in stage IB carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(1 Pt 1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toki N, et al. Microscopic ovarian metastasis of the uterine cervical cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 1991;41(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baltzer J, et al. Formation of metastases in the ovaries in operated squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix uteri (author’s transl) Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 1981;41(10):672–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1037313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sonmezer M, Oktay K. Assisted reproduction and fertility preservation techniques in cancer patients. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. 2008;15(6):514–22. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32831a46fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thun MJ, et al. The global burden of cancer: priorities for prevention. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):100–10. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young RH, et al. Ovarian metastases from cervical carcinomas other than pure adenocarcinomas. A report of 12 cases. Cancer. 1993;71(2):407–18. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2<407::aid-cncr2820710223>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang WD, et al. Unilateral ovarian metastasis in a case of squamous cervical carcinoma IA1. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2009;35(4):824–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.