Abstract

Background

Widespread restructuring of health delivery systems is underway in the US to reduce costs and improve the quality of healthcare.

Objective

To describe studies evaluating the impact of system-level interventions (incentives and delivery structures) on the value of US healthcare, defined as the balance between quality and cost.

Research Design

We identified articles in PubMed (2003 to July 2014) using keywords identified through an iterative process, with reference and author tracking. We searched tables of contents of relevant journals from August 2014 through 11 August 2015 to update our sample.

Subjects

We included prospective or retrospective studies of system-level changes, with a control, reporting both quality and either cost or utilization of resources.

Measures

Data about study design, study quality, and outcomes was extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Results

Thirty reports of 28 interventions were included. Interventions included patient-centered medical home (PCMH) implementations (n=12), pay-for-performance programs (n=10), and mixed interventions (n=6); no other intervention types were identified. Most reports (n=19) described both cost and utilization outcomes. Quality, cost, and utilization outcomes varied widely; many improvements were small and process outcomes predominated. Improved value (improved quality with stable or lower cost/utilization or stable quality with lower cost/utilization) was seen in 23 reports; 1 showed decreased value, and 6 showed unchanged, unclear or mixed results.

Study limitations included variability among specific endpoints reported, inconsistent methodologies, and lack of full adjustment in some observational trials. Lack of standardized MeSH terms was also a challenge in the search.

Conclusions

On balance the literature suggests that health system reforms can improve value. However, this finding is tempered by the varying outcomes evaluated across studies with little documented improvement in outcome quality measures. Standardized measures of value would facilitate assessment of the impact of interventions across studies and better estimates of the broad impact of system change.

Keywords: Care delivery system, quality of care, cost containment

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, approximately one fifth of spending is dedicated to health care. Recognition of lack of transparency, fragmentation, and the poor return for high spending has led to broad agreement about the need for fundamental change in the US health care system to both lower costs and improve quality. The concept of improving “value” has emerged to frame needed reforms.1,2 Value can be understood as the balance between care quality (in terms of patient satisfaction and health outcomes) and expenditures, though specific definitions vary among stakeholders.2,3

By 2013 several national policy organizations had proposed reforms to promote structural change and improve value in health care delivery.4 While some have questioned the likely impact of these interventions5, medical homes, value based purchasing, and pay-for-performance programs were endorsed consistently across organizations, leading government, insurers, and health plans to incentivize these strategies to improve value. Such efforts have led to demonstration and pilot projects with a rapidly expanding literature describing interventions and their outcomes. Early reports suggest that pilot project interventions have led to improvements in quality while reducing spending.6

To enhance our understanding of the potential impact of structural reforms on the health care system, we performed a systematic review of the effect of system-level interventions on the value of health care in the U.S. and present descriptions of relevant studies.

METHODS

Overview

We performed a systematic review of system-level US interventions which reported the components of value. We used the PRISMA statement on systematic reviews of studies reporting health care interventions7 to guide the methods. We defined system-level interventions as those that broadly altered either payment methods (e.g. pay-for-performance) or health care delivery structure (e.g. the patient-centered medical home model).

Framework for “value”

Definitions of value vary based on stakeholder.2 While different health systems establish variable thresholds for determining the cost-effectiveness of interventions8, all would agree that improved outcomes at fixed or lower cost represent improved value. We included papers assessing both quality of care (including patient satisfaction) and either the cost of care or health services utilization, which is often used as a proxy for cost.9 We conceptualized value as the balance between quality and cost or utilization, defining value improvement as better quality with lower or constant cost/utilization.

Study identification and data extraction

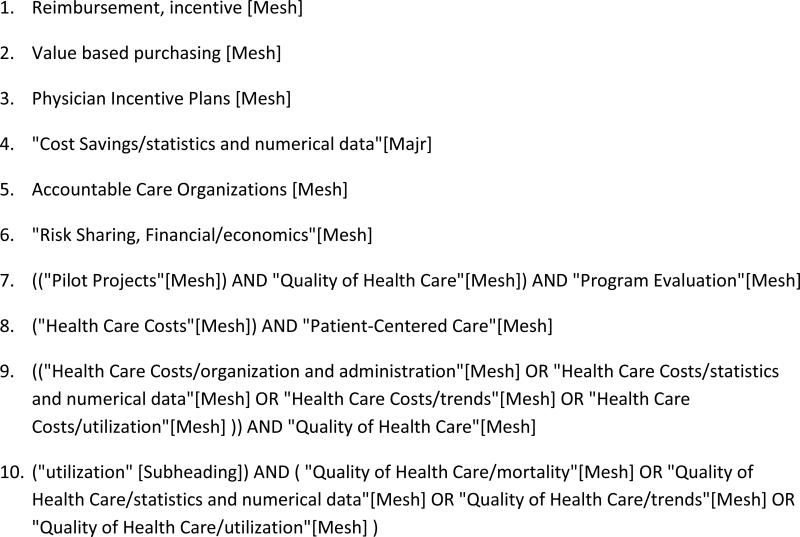

We conducted a MEDLINE search (PubMed interface) for studies published from January 1, 2003 through July 23, 2014, limited to human subjects, English language, and titles with abstracts. We used an iterative process to identify search terms (Figure 1) and identified additional articles through author and reference tracking. To update our results, we searched tables of contents of relevant journals published between August 1, 2014 and August 11, 2015, for articles potentially meeting inclusion criteria. See Supplementary Digital Content for details of study identification and data extraction.

Figure 1.

Terms Used in Search

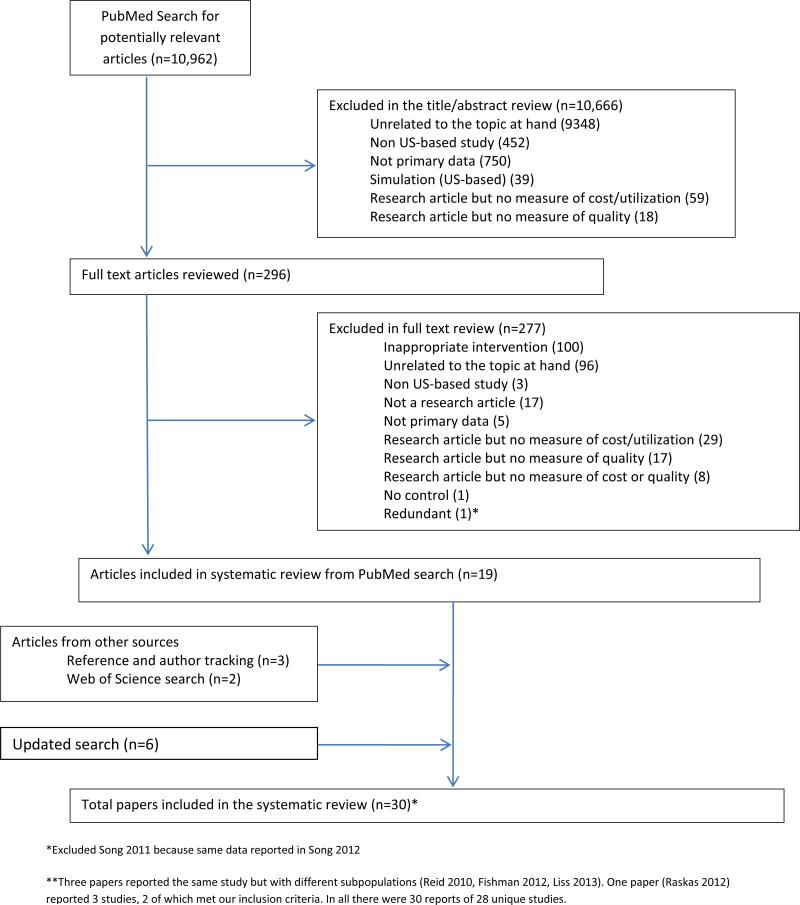

We included controlled studies evaluating the impact of system-level interventions on value in general clinical environments (e.g. physician's offices, hospitals). All papers were reviewed by 1 investigator (MJD, KD, DK, SK). A random sample of 296 full-text articles were reviewed by one of two pairs of investigators for determination of interrater reliability (Cohen ). Figure 2 demonstrates the flow of articles in the review.

Figure 2.

Flow of articles in the review

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (RA, KD, MJD, DK, or SK) and checked by a second reviewer (RA or DK) for accuracy. Differences were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Assessment of Study Quality

We collected information related to study quality using applicable components of the Cochrane risk of bias tools for cohort and randomized studies.10,11 For randomized trials we recorded the completeness of follow-up and whether the randomization method was described10; for observational studies we recorded whether confounders were assessed and whether adjustments were made for confounders.11

Determination of Value

We defined increased value as either 1) increased quality with no change or reduction in cost/utilization or 2) no change in quality with lower cost/utilization. We defined decreased value as 1) reduced quality with no change or increase in cost/utilization or 2) no change in quality with an increase in cost/utilization. Changes were defined as marginal when only one of multiple reported measures was significantly changed. We defined value as unchanged if both quality and cost/utilization were unchanged. We defined value as mixed when reported measures of quality or cost/utilization changed in opposite directions (e.g. two quality measures were reported, with one improving and one worsening) or when both quality and cost/utilization increased or decreased. While we recognize that some definitions of value (e.g. those based on cost-effectiveness) would allow for determinations of value in situations we deemed “mixed” such as when both quality and cost increase, cost-effectiveness and relevant thresholds are rarely reported. We defined value as unclear when the data presented were insufficient to draw conclusions (e.g. statistical significance not reported).

Data Analysis

Interrater reliability for the decision to include the article in the review was moderate to high (Cohen , 0.83 and 0.58 for the two investigator pairs). Given differences in interventions, study populations, study designs, and outcome measures, we did not attempt to pool study results; instead we present descriptive information.

RESULTS

Our initial search yielded 10,960 articles; 10,664 were excluded in title and abstract review. Including the updated search, 29 articles describing 29 studies of 28 interventions were included in the review (Figure 2). One article described 2 interventions and 3 articles described 2 studies of 1 intervention (the 3 articles all presented unique data and are listed separately, resulting in 30 reports described in Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year | Project name (if identified) | Clinical site | Population studied | Study design | Adjustment for confounders | Intervention group sample | Control group sample | Follow up time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Centered Medical Home Interventions (PCMH) | ||||||||

| Kaushal 201522 |

Primary care | Patients under the care of physicians from multiple health plans in NY State |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Full | 92 physicians | 183 physicians |

1 year | |

| Van Hasselt 201523 |

Primary care | All Medicare FFS*patients seen in participating clinics |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Full | 308 practices | 1906 practices |

2 years | |

| Friedberg 201415 |

Southeastern Pennsylvania Chronic Care Initiative (PACCI) |

Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinics |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 64243 patients |

55959 patients |

3 years |

| Christensen 201312 |

Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinic |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 4090 patients† |

4090 patients† |

1.5 years |

|

| Hochman 201316 |

Primary care | All patients seen in resident clinic |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 4679 patients‡ |

8899 patients‡ |

1 year | |

| Liss 201317§ | Group Health | Primary care | Adults with diabetes, CHD, or hypertension |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 1181 patients | 36757 patients |

2 years |

| Rosenthal 20139 |

RI Chronic Care Sustainability Initiative |

Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinics |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 31130 member months |

14779 member months |

2 years |

| Werner 201321 |

Primary care | Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield patients |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 10004 patients |

25055 patients |

1 year | |

| Devries 201213 |

Primary care | Patients under 65 years |

Retrospective concurrent comparator |

Full | 31032 patients |

350015 patients |

1-2 years |

|

| Fishman 201214§ |

Group Health | Primary care | Patients 65 and older | Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Partial | 1415 patients∥ |

1415 patients¶ |

2 years |

| Raskas 201218i**- CO |

CO Multipayer PCMH |

Primary care | Well point-affiliated plan members |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Partial | 6,200 patients |

2 years | |

| Raskas 201218** - NH |

NH Citizens Health Initiative Multi- Stakeholder†† |

Primary care | Wellpoint-affiliated plan members |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Partial | 10,000 patients |

15 months |

|

| Rosenberg 201220 |

Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinics |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 23900 patients |

Not stated | 2 years | |

| Reid 201019 | Group Health | Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinic |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Partial | 7018 patients | 200970 patients |

2 years |

| Pay for Performance Interventions | ||||||||

| Lemak 201532 |

Physician Group Incentive Program |

Primary care, Specialty |

Blue Cross Blue Shield of MI patients |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Full | 7774 practices |

2991 practices |

2-3 years |

| McWilliams 201533 |

Pioneer ACO | Random sample of FFS Medicare patients |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Full | 201,644 (post) - 566,410 (pre) patients |

4.8 million (post) -14.2 million (pre) patients |

1 year | |

| Chien 201426 |

Alternative Quality Contract |

Primary care | Blue Cross Blue Shield of MA HMO pediatric patients |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 126975 patients |

415331 patients |

2 years |

| Esse 201328 | Primary care | Medicare Advantage patients |

Cross-sectional analysis | Full | 1225 patients |

3015 patients |

1 year | |

| Calikoglu 201224 |

Quality-Based Reimbursement Program |

Hospital | Medicare patients | Retrospective concurrent comparator |

Full | ~700,000 discharges annually |

Details not specified |

3 years |

| Colla 201227 | Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration |

Primary care | Medicare patients | Retrospective concurrent comparator |

Full | 990,177 patients |

7514453 patients |

5 years |

| Song 201231 | Alternative Quality Contract |

Primary care | Blue Cross Blue Shield of MA patients |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 428892 patients |

1339798 patients |

2 years |

| Chen 201025 | Primary care | Patients with diabetes | Concurrent comparator | Full | 30617 patients‡‡ |

1748 patients§§ |

3 years | |

| Leitman 201029 |

Hospital | Inpatient admissions to 1 hospital |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

None | 29535 patients |

20360 patients |

3 years | |

| Ryan 200930 | Premier Inc./CMS Hospital Quality Incentive Demo |

Hospital | Medicare patients with AMI, HF, pneumonia, or CABG |

Concurrent comparator | Full | 256 PHQID hospitals |

3077 control hospitals∥∥ |

6 years |

| Mixed interventions | ||||||||

| Friedberg 201539 |

Northeastern Pennsylvania Chronic Care Initiative (PACCI) |

Primary care | All patients seen in participating clinics |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 27 practices | 29 practices |

3 years |

| Fifield 201337 |

Primary care | Patients seen in participating clinics |

RCT | NA | 18 practices | 14 practices |

2 years | |

| Claffey 201236 |

Primary care, specialty |

Medicare Advantage patients |

Concurrent comparator | None | 750 patients | Not stated | 3 years | |

| Salmon 201238 |

Collaborative Accountable Care Initiative |

Primary care, multispecialty |

Cigna Health patients | Concurrent comparator | Partial | 3 practices | 1 year | |

| Fagan 201035 |

Primary and multispecialty |

Elderly patients with diabetes |

Pre-post/concurrent comparator |

Full | 1587 patients |

19356 patients |

1 year | |

| Gilfillan 201034 |

Proven Health Navigator |

Primary care | Medicare Advantage patients |

Pre-post/ concurrent comparator |

Full | 8634 patients |

6676 patients |

Up to 4 years |

FFS=fee for service

Not fully reported; Quality outcomes based on survey of 4090 patients from combined intervention and comparator sites

Numbers differed from pre- to post-; these are the post-intervention numbers

Studies describe different outcomes from the same intervention ∥1415 patients for quality outcomes and 1947 for utilization outcomes

130067 patients for quality outcomes and 39396 for utilization outcomes

Includes three pilots; however two (CO and NH) are reported because the third site (NY) had only baseline data available

Full name is: NH Citizens Health Initiative Multi-Stakeholder Medical Home Pilot

Changed over time; 30617 patients in the final year

Numbers changed over time; 1748 patients in the final year

3077 control hospitals (118 eligible nonparticipating hospitals and 2959 noneligible hospitals)

Table 2.

Results of included studies: quality, utilization, cost and value.

| Author, year | Quality outcomes | Quality results summary | Utilization outcomes | Utilization results summary | Cost outcomes | Cost results summary | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedberg 201539 |

Improved: Breast cancer screening (5.6% difference); Diabetes care: HbA1C testing (8.3% difference), LDL testing (8.5% difference), nephropathy testing (15.5% difference), eye examinations (12.0% difference) Unchanged: Colorectal cancer screening No outcome measures |

5/6 improved 1/6 unchanged |

Decreased (rate per 1000 patients/month): Hospitalizations (difference 1.7), ED visits (difference 4.7), specialty visits (difference 17.3) Increased: primary care visits (77.5) |

4/5 decreased 1/6 increased (desired change) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Increased |

| Kaushal 201522 |

Unchanged: Readmissions Outcome measure included but unchanged |

No Change |

Decreased: specialty visits (difference of 21.4/100 patients) Unchanged: Primary care visits, diagnostic tests, lab tests, admissions |

1/6 decreased 5/6 unchanged | Not Reported | Not Reported | Marginal Increase* |

| Lemak 201532 |

Only early participants vs. nonparticipants reported Improved: Breast cancer screening (1% difference), adolescent well care (18.2% difference) and immunization (23.9% difference), child immunization (2.8% difference), well child visit 3-6 years (11.6% difference), Diabetes care: lipid therapy (1.7% difference), testing for HbA1c (3.2% difference), LDL (2.1% difference), nephropathy (2.2% difference), ACE inhibitors for: nephropathy (4.6% difference), hypertension (1.7% difference) Unchanged: Cervical cancer screening, well child visit 0-15 months, ACE inhibitors in patients with HF No outcome measures |

11/14 increased 3/14 unchanged |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Decreased: Total spending: adult patients (−1.1%), pediatric patients (−4%) | Decreased | Increased |

| McWilliams 201533 |

Improved: Preventive services for patients with diabetes: HbA1c testing (0.5% difference), LDL testing (0.5% difference), retinal examination (0.8% difference ), receipt of all 3 (0.8% difference) Unchanged: 30 day readmissions, mammography in women aged 65-69 Outcome measure included but unchanged |

1/3 increased 2/3 unchanged |

Unchanged: hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions | No Change | Decreased: quarterly per-beneficiary spending (difference $29.20) | Decreased | Increased |

| Van Hasselt 201523 |

Unchanged: 30 day readmissions (overall and amb care sensitive) Outcome measure included but unchanged |

No Change |

Decreased: ED visits: overall (difference 54.8 per 1000 patients), amb care sensitive conditions (difference 13.4 per 1000 patients) Unchanged: hospitalizations, primary care visits, specialist visits |

1/5 decreased 4/5 unchanged |

Decreased: total Total payments (difference $265), hospital payments (difference $165) Unchanged: payments to outpatient department, home health, hospice, physicians |

2/6 decreased 4/6 unchanged |

Increased |

| Chien 201426 |

Improved: Composite of 6 HEDIS metrics: difference in difference 2.4% for special needs children and 1.9% for usual needs children; child/adolescent well visits, chlamydia screening; pharyngitis testing, upper respiratory infection treatment Unchanged: Infant well visits and all measures NOT tied to P4P No outcome measures |

Measures tied to P4P: 6/7 improved 1/7 unchanged |

Unchanged: ED visits for persistent asthma† | No Change | Unchanged: Average per capita annual medical spending | No Change | Increased |

| Friedberg 201415 |

Improved: Nephropathy monitoring (5.6 to 16.3 by year3) Unchanged: Breast cancer screening; diabetic eye exam; HbA1C testing; HbA1C abnormal; LDL testing; LDL abnormal; cervical cancer, chlamydia, and colorectal screen, appropriate asthma appropriate medication Outcome measures included but unchanged |

1/11 improved 10/11 unchanged |

Unchanged: Primary care visits, specialty visits, ED visits, amb care sensitive ED visits, admissions, hospitalizations | No Change | Unchanged: Adjusted dollar per 1000 patients per month unchanged | No Change | marginal Increase |

| Christensen 201312 |

Improved: Patient satisfaction (0.78 to 0.82) Significance not stated for: HbA1C testing, HbA1C>9 LDL screening, LDL <100, Pap smear testing, Asthmatics, Mammography screening, Colorectal cancer screening Outcome measures included; change unclear |

1/9 increased 8/9 significance not stated |

Significance not stated for: Primary care visits, Specialty visits, ED visits, Admi ssions, Length of stay | Unclear | Significance not stated: total costs (9% reduction) and Pharmacy/ancillary costs | Unclear | marginal Increase |

| Esse 201328 |

Improved§: LDL-C screen (OR 1.425), A1C testing (OR 1.468), % measured creatinine (OR 1.891), % measured microalbumin (OR 2.319), Flu vaccination (OR, 1.383) No outcome measures |

Increased | Unchanged: ER visits, acute admits | No Change | Not Reported | Not Reported | Increased |

| Fifield 201337 |

Improved: Breast cancer screening (+3.5% vs −0.4% in control), hypertensive BP Control (+23.2% vs. −1.9%) Unchanged: Lipid screening in CV disease and diabetes, Nephrology screening, Chlamydia screening, Diabetic HbA1C testing, Lipid Control in CV disease and diabetes, diabetic BP Control, HbA1C Control Outcome measures included; ¼ improved |

2/11 increased 9/11 unchanged |

Decreased: ED Visits (ratio −0.7% vs +0.5 in control group) Unchanged: ED Efficiency and Hospital Adm Efficiency Indices, Hospital Admissions |

1/4 decreased 3/4 no change |

Total costs, ED, hospital admin, outpatient costs unchanged | No Change | Increased |

| Hochman 201316 | Patient satisfaction improved (0.64 to 0.8) No outcome measures |

I ncreased | Increased: Admissions (25 to 27) Unchanged: ED visits, total ED or hospital use |

1/3 increased 2/3 no change |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Mixed |

| Liss 201317‡ |

Improved: DM: A1C testing (RR 1.01), A1C <9% (RR 1.03), CHD: LDL<100 mg/dL (RR 1.11), DM: A1C% (RR −0.15), CHD: LDL (RR −2.20) Unchanged: BP<140/90, systolic BP, CHD: LDL screening Outcome measures included; 3/5 improved |

5/8 improved 3/8 unchanged |

Decreased: Ambulatory care sensitive hospitalization (RR 0.59), total inpatient admissions (RR 0.76), Urgent care (RR 0.85), primary care visits (RR 0.93) Unchanged: Specialty care visits |

3/5 decreased 2/5 no change |

Decreased: Total monthly per member cost (RR 0.83) | Decreased | Increased |

| Rosenthal 201334 |

Unchanged: HbA1C testing, Lipid testing, Diabetic eye exam, Colon, breast, and cervical cancer screening No outcome measures |

No Change | Decreased: Amb care sensitive ED visits (RR 0.75) Unchanged: Admissions, Amb care sensitive admissions, primary care and specialty visits, ED visits, # of prescriptions, prescription days |

1/8 decreased 7/8 no change |

Not Reported | Not Reported | marginal Increase |

| Werner 201321 |

Improved: Mammogram screening (difference in differences +0.022)§ Decreased: Nephropathy screen (difference in differences −0.066)§ Unchanged: A1C testing, eye exam, LDL screen, Colon cancer screen, 30 day readmission, pap smear, chlamydia screening, LDL testing in CV disease 1 outcome measure; unchanged |

1/10 increased 1/10 decreased 8/10 unchanged |

Unchanged: ED visits, admissions | No Change | Payment per member quarter unchanged | No Change | Mixed |

| Calikoglu 201224 |

Improved: Risk adjusted complication rates for 13 conditions Hospital acquired conditions reduced by 15.2% over 2 years Outcome measures improved |

Increased | Not Reported | Not reported | Savings from complications (−$110 million) | Decreased | Increased |

| Claffey 201236 |

Significance not stated: 30-day readmission (33% fewer in intervention) Outcome measures; change unclear |

Unclear | Significance not stated: ED visits (11.70% increase), acute admissions (30% reduction), subacute admissions (14% reduction) | Unclear | Significance not stated: Per member per month total (33% decrease) | Unclear | Unclear |

| Colla 201227 |

Improved: 30-day medical readmission rate (−0.67%), for dually eligible (−1.07%) and nondually eligible (−0.58%), 30-day surgical readmission rate for dually eligible (−2.21%) Unchanged: 30-day surgical readmission rate overall and non-dually eligible Outcome measures only |

4/6 improved 2/6 unchanged |

ED visit rate no change overall, for dually eligible or for nondually eligible participants | No Change | Spending annually per beneficiary mean - savings overall ($496), and among dually eligible ($751) and non-dually eligible ($404)∥ | Decreased | Increased |

| Devries 201213 |

Improved: A1C testing in diabetics (0.82 vs. 0.77), LDL screen (0.76 vs. 0.74) and LDL control (0.65 vs. 0.57) in CV disease, imaging for low back pain (0.48 vs. 0.53), appropriate pharyngitis testing (children) (0.97 vs. 0.91), antibiotic use in viral URI (children) (0.27 vs. 0.35), long-term controller medications in asthmatics (0.99 vs. 0.98) Reduced: Nephropathy care (0.78 vs. 0.81) Unchanged: A1C control, LDL screen, LDL control, Eye exams in diabetics, antibiotic use in acute bronchitis (adults) Outcome measures included; 1/3 improved |

7/13 increased 1/13 decreased 5/13 unchanged |

Decreased§: Pediatric hospitalizations (OR 0.77), pediatric ED visits (OR 0.83), adult hospitalization (OR 0.88), adult ED visits (OR 0.88) | Decreased | Total costs per member per month decreased in pediatric (−8.62%) and adult (−14.50%) patients | Decreased | Increased |

| Fishman 201214‡ | Patient satisfaction Improved: ACES - 2/5 measures Unchanged: PACIC - 2/2, composite quality No outcome measures |

1/2 increased¶ | Decreased: Primary care visits (RR 0.93), ED visits (RR 0.79), Amby care sensitive admissions (RR 0.82) Increased: Specialty visits (RR 1.05) Unchanged: Admissions |

1/5 increased 3/5 decreased 1/5 unchanged |

Total cost per patient per month unchanged | No Change | Marginal Increase |

| Raskas 201218 - CO** |

Significance not stated: A1c>9%; BP <130/80, Retinal disease, Nephropathy screening, Flu shot, Aspirin therapy, LDL doc, LDL <100 mg/dl, A1c, Rx statins, Queried about tobacco use, and Depression screening increased Outcome measures included; change unclear |

Unclear | Significance not stated: acute inpatient admissions decreased; Specialty visits decreased; ED visits increased†† | Unclear | Significance not stated: estimated ROI 2.5:1 to 4.5:1) | Unclear | Unclear |

| Raskas 201218 - NH** |

Significance not stated: Quality data unchanged Outcome measures unclear |

Unclear | Significance not stated: ED visits decreased | Unclear | Per patient per month cost decreased‡‡ | Unclear | Unclear |

| Rosenberg 201220§§ |

Improved: Readmissions (18.3% decrease vs. 1.4% decrease) Unchanged: HbA1C testing, diabetic eye exam, LDL screen, nephropathy monitoring, colon and breast cancer screen, depression management No outcome measures |

1/8 increased 7/8 unchanged |

Decreased: Admissions (4.4% difference in difference) and ED visits (3.6% difference in difference) | Decreased | Dollars per member per month decreased∥∥ | Decreased | Increased |

| Salmon 201238 |

Unchanged: HbA1C testing, serum Creat in HTN, LDL testing, mammogram, nephropathy screening in diabetes No outcome measures |

No Change | Not Reported | Not Reported | Total cost in dollars per patient per month in AZ ($27.04 savings)† Total cost in NH and TX u ncha nge d | 1/3 sites decreased 2/3 sites unchanged |

Marginal Increase |

| Song 201231 |

Improved§: Aggregates for chronic care (3.7% difference in differences), preventative care (0.4% difference in difference), pediatric care (1.3% difference in differences) No outcome measures |

Increased | Not Reported | Not Reported | Average total quarterly spending per member decreased ($22.58 savings) | Decreased | Increased |

| Chen 201025 |

Improved: Receipt of quality care (2 A1c and 1 LDL check) (OR 1.2) No outcome measures |

Increased | Hospitalization decreased (RR 0.75) | Decreased | Not Reported | Not Reported | Increased |

| Fagan 201035¶¶ |

P4P incentivized measures: Increased: Influenza vaccination (OR 1.79) Decreased: HbA1C testing (OR 0.44) and LDL screens (OR 0.62) Unchanged: Diabetic eye exam, nephropathy screen, non-incentivized: ACE inhibitor use, short-acting antihypertensives No outcome measures |

1/7 increased 2/7 decreased 4/7 unchanged |

ED visits unchanged | No Change | Total cost to insurer unchanged | No Change | Marginal Decrease |

| Gilfillan 201034 |

Improved: 30 day readmissions (36% reduction) Outcome measure improved |

Increased | Admissions decreased (18% reduction) | Decreased | Plan payment plus member copayment unchanged | No Change | Increased |

| Leitman 201029 | Noted improved compliance with core measures (acute MI, heart failure, pneumonia and surgical care); not reported based on participation No outcome measures |

Unclear | Length of stay unchanged | No Change | Savings compared to baseline ($38000/physician over 3-year period) | Decreased | Increased |

| Reid 201019‡ |

Improved: Quality of care composite (6% to 7.3%), pati ent satisfaction (3/5 ACES and 2/2 PACI C) No outcome measures |

Increased | Decreased: Primary care visits (RD 0.94), ED visits (RD 0.71), Inpatient admissions - ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (RD 0.87), Inpatient admissions - all causes (RD 0.94) I ncreased: Specialty visits (RD 1.03) |

4/5 decreased 1/5 increased |

Total cost per patient per month unchanged | No Change | Increased |

| Ryan 200930 |

Unchanged: 30 day mortality for AMI, HF, pneumonia, and CABG Outcome measures unchanged |

No Change | Not Reported | Not Reported | 60 day cost∥: AMI decreased (27.1 to 25.1) HF increased (13.1 to 13.4) Pneumonia unchanged | 1/3 decreased 1/3 increased 1/3 no change |

No Change |

Changes labeled marginal net change seen in only one of many measures

Measure was not tied to P4P

Multiple reports same intervention using different outcomes

Adjusted

Significant in only one model for non-dually eligible

Within patient satisfaction only 2/7 measures improved

Statistical significance not reported for any outcomes

Acute inpatient admissions decreased (18% decrease in intervention vs. 18% increase in control); specialty visits decreased (0% vs. 10% increase in control); ED visits increased (15% increase vs. 4% decrease in control)

For Wellpoint members, cost increased 5% in intervention compared to 12% in control practices

Years 1 and 2 reported separately; all results are for year 2

Dollars per member per month decreased compared to control sites in year 2 (although higher in year 1)

ORs are for change in intervention compared to change in control

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 describes study characteristics of the 30 separate included reports. 14 interventions were primarily PCMH implementations,9, 12-23 10 were pay-for-performance programs24-33, and 6 were mixed with features of both intervention types.3,34-39

Study quality varied. There was one randomized trial37; the method of randomization, drop-outs, and follow-up were well described. Among the remaining observational studies, 22 adjusted fully for confounding factors, 5 performed partial adjustment, and 2 did not adjust for confounders.

Impact of interventions on quality

Reported quality indicators varied widely (Table 2) and most studies reported multiple quality outcomes (predominantly process measures). The most commonly reported outcome was the rate of hemoglobin A1C testing in diabetic patients (14 studies), followed by lipid testing rates (14 studies), cancer screening rates (11 studies), readmission rates (7 studies), composite quality measures (5 studies), patient satisfaction (5 studies), and diabetes control (5 studies). Measures of overuse were reported in 2 studies; a PCMH intervention reported unnecessary imaging for low back pain13 and a pay-for-performance intervention reported unnecessary pharyngitis testing 26; rates of overuse declined in both. Mortality was reported in one study of a pay-for-performance intervention30 and did not decline significantly in the intervention group.

Overall, 17 studies found net improvement in quality (though often some measures were unchanged or reduced), 5 found marginal improvement, 3 found no change, 1 found marginal decline in quality, 1 found no change, and 3 had unclear results (Table 2).

Impact of interventions on cost and utilization

Most reports (n=19) described both cost and utilization outcomes; 5 reported only cost and 6 reported only utilization (Table 2). Specific cost and utilization outcomes varied widely. Utilization outcomes generally focused on rates of outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalization. Several studies reported total cost per beneficiary over a defined time period.

Impact of interventions on value

There were 30 reports from which we summarized the impact on value (Table 2). Value was improved in 17, marginally improved in 6, marginally lower in 1, unchanged in 1, and unclear or mixed in 5. Given the variability in specific outcome measures, direct comparisons of the impact of different interventions on value cannot be made.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we describe system-level interventions for which value-relevant outcomes have been reported. Interventions included PCMH implementations, pay-for-performance initiatives, and programs with features of both. We found wide variability in study quality and reported outcome measures. The limited available evidence suggests that PCMH and pay-for-performance initiatives improve value, but the magnitude and importance of this improvement is not clear.

We defined value loosely for the purposes of this review, crediting improved value when improvements in quality, cost, or utilization were very small, clinically trivial, or limited to patients with specific diagnoses. This approach likely overestimated value improvements. We opted to loosely define value so our findings will reflect the majority of published studies of system interventions so far. However, given the importance of optimizing value, it will be critical for future studies to measure outcomes that facilitate meaningful value calculations and to include broad patient populations. Further, as experts attempt to estimate the impact of care delivery innovations across the US healthcare system, thresholds for important changes in value will need to be established.

Quality is an important driver of value but some quality outcomes are more meaningful than others. We credited “marginal” quality improvement when at least one of many measures improved, which may have overestimated value improvements. If we applied a more stringent definition of improved value, requiring improvement in at least 2 quality measures, the majority of studies (17/30) still found that value improved. However, most reported quality outcomes involved process measures (e.g. the proportion of diabetic patients in whom HbA1C was checked) and not outcome measures (e.g. improvements in HbA1C values). There were few changes in measures of clinical outcomes; indeed none of the most recent studies (published in 2014 or 2015) found improvements in outcome measures; 3 evaluated no outcome measures and 4 included them but found that they did not improve. This failure to impact outcome measures is important. While process measures can predict meaningful patient outcomes40, 41, their association with clinical improvements may be limited 42 and they may poorly reflect population health43. Further, observed quality improvements were often of small magnitude (Table 2). The clinical importance of these changes is unclear; assessment of true clinical outcomes rather than process measures would facilitate a richer understanding of the impact of system level interventions.

Cost outcomes were similarly heterogeneous. Among the 8 highest quality studies, only 3 found lower cost, each using a different approach to measure costs. And it is notable that these assessments did not include costs associated with practice transformation or incentive payments. Standard cost measures are needed to facilitate direct comparison and estimation of the likely impact of larger-scale interventions. Several studies measured cost as total dollars spent per patient per month; this seems the most appropriate standard for use in future studies.

It is notable that only two evaluations in our review addressed overuse, which contributes to both poor quality and higher costs44. Both studies found a reduction in overuse. However, the exclusion of overuse outcomes from the majority of studies is problematic since it is important that system-level interventions successfully minimize overuse.

Our study has important limitations. Since utilization is a proxy for cost, we included studies which measured utilization and not cost. However, utilization may be a poor measure of cost45. In addition, we did include cost-effectiveness when conceptualizing value; indeed cost-effectiveness was not reported in any identified studies and was beyond the scope of these studies. Limiting our review to studies evaluating cost-effectiveness would have limited its scope. However, attention to cost-effectiveness will be critical to more nuanced future assessments of value. Further, there are no specific MeSH terms for health care value so our search may have failed to identify studies. However, extensive reference and author tracking make it unlikely we missed large important studies. Finally, we focused primarily on value, for which there is no standard calculation method. Our intentionally liberal approach is meant to be descriptive and may have overestimated the impact of interventions.

In conclusion there is a small emerging body of literature on PCMH and pay-for-performance interventions that suggests that these interventions may to some extent improve value. However despite the broad nation-wide movement toward these system-level reforms we found only 30 assessments of their impact on value. Further, studies to date are methodologically limited and the diversity of specific measures precludes direct comparisons among interventions. Standardization of the definition of value and the measures used to assess value and replication of our findings under more standardized conditions are critical for optimizing the evidence base to inform system-wide change.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was not supported by external funding.

References

- 1.Porter M. A Strategy for Health Care Reform — Toward a Value-Based System. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:109–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter M. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanLare JM, Conway P. Value-based purchasing--national programs to move from volume to value. New Engl Jl Med. 2012;367(4):292–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1204939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewin J, Atkins G, McNeely L. The elusive path to health care sustainability. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1669–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmor T, Oberlander J. From HMOs to ACOs: the quest for the Holy Grail in U.S. health policy. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1215–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2024-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Two Blues Plans Find Success With Medical Homes, Look to Expansion. [February 4 2015];Health Business Daily. 2011 http://aishealth.com/archive/nblu1111-03.

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiroiwa T, Sung YK, Fukuda T, et al. International survey on willingness-to-pay (WTP) for one additional QALY gained: what is the threshold of cost-effectiveness? Health Econ. 2010;19(4):422–37. doi: 10.1002/hec.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal MB, Friedberg MW, Singer SJ, et al. Effect of a multipayer patient-centered medical home on health care utilization and quality: the Rhode Island chronic care sustainability initiative pilot program. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1907–13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins J, Altman D, Gotzsche P, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cochrane Collaboration [February 4 2015];Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies. https://bmg.cochrane.org/sites/bmg.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Tool_to_Assess_Risk_of_Bias_in_Cohort_Studies.pdf.

- 12.Christensen EW, Dorrance KA, Ramchandani S, et al. Impact of a patient-centered medical home on access, quality, and cost. Mil Med. 2013;178(2):135–41. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeVries A, Li CH, Sridhar G, et al. Impact of medical homes on quality, healthcare utilization, and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(9):534–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishman PA, Johnson EA, Coleman K, et al. Impact on seniors of the patient-centered medical home: evidence from a pilot study. Gerontologist. 2012;52(5):703–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedberg MW, Schneider EC, Rosenthal MB, et al. Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(8):815–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochman ME, Asch S, Jibilian A, et al. Patient-Centered Medical Home Intervention at an Internal Medicine Resident Safety-Net Clinic. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1694–701. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liss DT, Fishman PA, Rutter CM, et al. Outcomes Among Chronically Ill Adults in a Medical Home Prototype. Am Jl Man Care. 2013;19(10):E348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raskas RS, Latts LM, Hummel JR, et al. Early results show WellPoint's patient-centered medical home pilots have met some goals for costs, utilization, and quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(9):2002–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(5):835–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg CN, Peele P, Keyser D, et al. Results from a patient-centered medical home pilot at UPMC Health Plan hold lessons for broader adoption of the model. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(11):2423–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner RM, Duggan M, Duey K, et al. The patient-centered medical home: an evaluation of a single private payer demonstration in New Jersey. Med Care. 2013;51(6):487–93. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31828d4d29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaushal R, Edwards A, Kern LM. Association between patient-centered medical home and healthcare utilization. Am J Man Care. 2015;21(5):378–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Hasselt, McCall N, Keyes V, et al. Total cost of care lower among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving care from patient-centered medical homes. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):253–72. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calikoglu S, Murray R, Feeney D. Hospital pay-for-performance programs in Maryland produced strong results, including reduced hospital-acquired conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(12):2649–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JY, Tian H, Taira Juarez D, et al. The effect of a PPO pay-for-performance program on patients with diabetes. Am J Man Care. 2010;16(1):e11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien AT, Song Z, Chernew ME, et al. Two-year impact of the alternative quality contract on pediatric health care quality and spending. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):96–104. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colla CH, Wennberg DE, Meara E, et al. Spending differences associated with the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1015–23. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esse T, Serna O, Chitnis A, et al. Quality compensation programs: are they worth all the hype? A comparison of outcomes within a Medicare advantage heart failure population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(4):317–24. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leitman IM, Levin R, Lipp MJ, et al. Quality and financial outcomes from gainsharing for inpatient admissions: a three-year experience. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):501–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan AM. Effects of the Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration on Medicare patient mortality and cost. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):821–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. The ‘Alternative Quality Contract,’ based on a global budget, lowered medical spending and improved quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1885–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemak CH, Nahra TA, Cohen GR, et al. Michigan's fee-for-value physician incentive program reduces spending and improves quality in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(4):645–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE, et al. Performance differences in year 1 of pinoeer accountable organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1927–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilfillan RJ, Tomcavage J, Rosenthal MB, et al. Value and the medical home: effects of transformed primary care. Am J Man Care. 2010;16(8):607–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagan PJ, Schuster AB, Boyd C, et al. Chronic care improvement in primary care: evaluation of an integrated pay-for-performance and practice-based care coordination program among elderly patients with diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1763–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claffey TF, Agostini JV, Collet EN, et al. Payer-provider collaboration in accountable care reduced use and improved quality in Maine Medicare Advantage plan. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(9):2074–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fifield J, Forrest DD, Burleson JA, et al. Quality and efficiency in small practices transitioning to patient centered medical homes: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):778–86. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2386-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmon RB, Sanderson MI, Walters BA, et al. A collaborative accountable care model in three practices showed promising early results on costs and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(11):2379–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedberg MW, Rosenthal MB, Werner RM, et al. Effects of a Medical Home and Shared Savings Intervention on Quality and Utilization of Care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1362–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mant J, Hicks N. Detecting differences in quality of care: the sensitivity of measures of process and outcome in treating acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1995;311(7008):793–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7008.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Roos JM, et al. Alternative pay-for-performance scoring methods: implications for quality improvement and patient outcomes. Med Care. 2009;47(10):1062–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a7e54c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleetcroft R, Steel N, Cookson R, et al. Incentive payments are not related to expected health gain in the pay for performance scheme for UK primary care: cross-sectional analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(94) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.James TI. Is It Time to Change Directions of Quality Measures? Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(6):555–6. doi: 10.1177/1062860613515741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell E, et al. Overuse of Health Care Services in the United StatesAn Understudied Problem. JAMA Intern Med. 2012;172(2):171–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Painter M, Chernew ME. Counting Change. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2012. [26 November, 2014]. http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2012/03/counting-change.html. [Google Scholar]