Abstract

Megakaryopoiesis is the process by which bone marrow progenitor cells develop into mature megakaryocytes (MKs), which in turn produce platelets required for normal hemostasis. Over the past decade, the molecular mechanisms that contribute to MK development and differentiation have begun to be elucidated. In this review, we provide an overview of megakaryopoiesis and summarize the latest developments in this field. Specially, we focus on polyploidization, a unique form of the cell cycle that allows MKs to increase their DNA content, and the genes that regulate this process. In addition, since megakaryocytes play an important role in the pathogenesis of acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMKL) and a subset of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), including essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF), we discuss the biology and genetics of these disorders. We anticipate that an increased understanding of normal megakaryocyte differentiation will provide new insights into novel therapeutic approaches that will directly benefit patients.

Keywords: Megakaryocytes, endomitosis, myeloproliferative neoplasms, myeloid leukemia

Overview of Megakaryopoiesis

Megakaryocytes (MKs), the precursors of platelets, are derived from pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Every day approximately 1×1011 platelets are produced by the cytoplasmic fragmentation of MKs, a level of production that can increase 10- to 20- fold in times of demand and an additional 5- to 10- fold under the stimulation of thrombopoietin-mimetic drugs (1). Megakaryocytes are fairly rare: within the normal human marrow, only 1 in 10,000 nucleated cells is a megakaryocyte. The hallmark of the MK is its large diameter (50–100 μm) and its single, multi-lobulated, polyploid nucleus. The external influences that impact megakaryopoiesis include a supportive bone marrow stroma consisting of endothelial and other cells, matrix glycosaminoglycans, and a number of hormones and cytokines, such as thrombopoietin (TPO), stem cell factor (SCF), and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1).

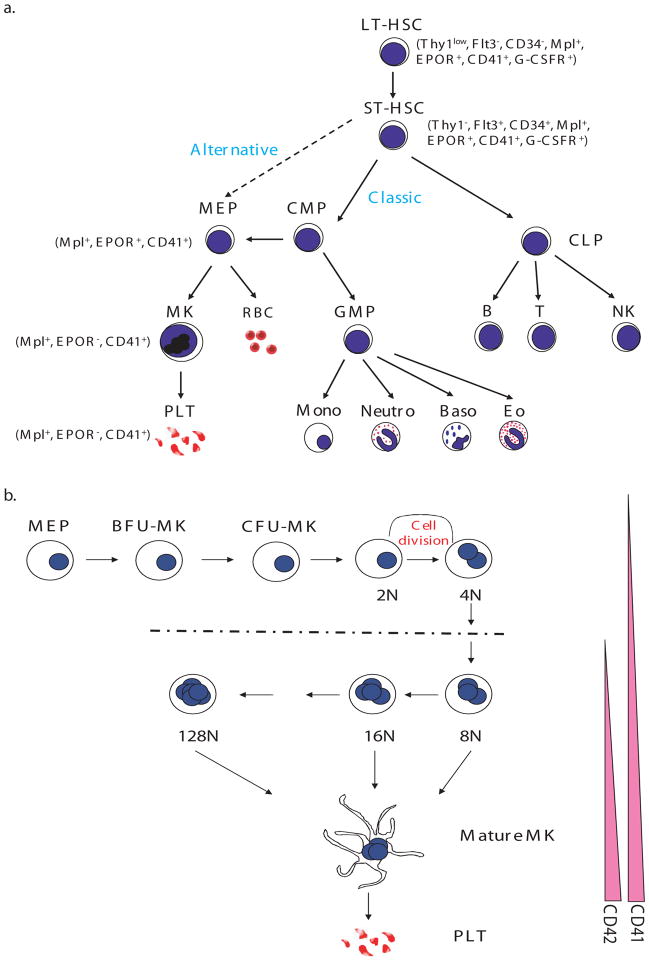

In the canonical pathway of hematopoietic lineage development (2–6), the HSC gives rise to two major lineages, the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) (7) and the common myeloid progenitor (CMP) (4) (Figure 1). The CLP then generates lymphocytes (NK, T and B cells), whereas the CMP produces the granulocyte/macrophage progenitor (GMP) and the megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor (MEP) (8, 9). Other evidence suggests that the MEP can arise directly from the HSC to give rise to the erythroid and megakaryocyte lineages without a CMP intermediate (10, 11). The existence of this alternate pathway is under debate. For example, Forsberg et al. showed that Flt3(+) early progenitors retain megakaryocyte and erythroid potential in vivo both at the population and clonal levels (12). In either case, the first cells fully committed to the megakaryocyte lineage are BFU-MK (burst forming unit-megakaryocyte), which give rise to a more differentiated MK progenitor, termed colony-forming unit-megakaryocyte (CFU-MK). Committed megakaryocyte progenitors can be identified by distinct surface immunophenotype as a population of CD9+CD41+FcγRloc-kit+Sca-1+IL-7Rα–Thy1.1–Lin– cells in murine bone marrow. This population is restricted to producing MKs and platelets both in vitro and in vivo (13).

Figure 1. Pathways to Megakaryocytes.

A) The hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gives rise to all blood cell lineages. In the classical model, the first lineage commitment step of HSCs results in a separation of common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLP). The megakaryocyte erythroid progenitor (MEP), the precursor of megakaryocytes and erythroid cells, is derived from CMP. In the alternative model, the HSC directly gives rise to the MEP before restriction to myeloid or lymphoid lineages. B) Megakaryocyte progenitors, including the MEP, BFU-MK and CFU-MK, proliferate and differentiate into platelet-producing mature MKs. During this process, megakaryocytes undergo endomitosis to increase their size and DNA content. In murine cells, the DNA content can increase up to 128N. Simultaneously, expression of the megakaryocyte specific makers CD41 and CD42 is upregulated. LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC; Thy1, thymus 1 (“low” indicates low surface antigen and “−” indicates none detectable); Flt3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; EPOR, erythropoietin receptor; CD41, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa or αIIbβ3 integrin receptor; G-CSFR, G-CSF receptor; MK, megakaryocyte; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; Mono, monocyte; Neutro, neutrophil; Baso, basophil; Eo, eosinophil; B, B cell; T, T cell; NK, nature killer cell; BFU-MK, burst forming unit-megakaryocyte; CFU-MK, colony forming unit-megakaryocyte.

Megakaryopoiesis is first observed in the embryonic yolk sac where it is closely associated with primitive and definitive erythropoiesis (14–16). Primitive MEPs are seen as early as E7.25, indicating that primitive hematopoiesis is bi-lineage in nature. The first glycoprotein-Ib (GP1b) positive cells, corresponding to megakaryocytes, can be seen in the yolk sac at E9.5, while platelets can be detected in the embryonic bloodstream beginning at E10.5. At this time, the number of megakaryocyte progenitors begins to decline in the yolk sac and expand in the fetal liver. Of note, fetal platelets are extremely large, with a diameter 1.6-fold larger than adult platelets and contain a high amount of RNA, a feature also observed in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura, highlighting the similarity between embryonic megakaryopoiesis and adult stress-megakaryopoiesis.

MKs and the endomitotic process

One of the most characteristic features of megakaryocyte development is endomitosis, a modified form of mitosis in which the DNA is repeatedly replicated in the absence of cytoplasmic division. During the endomitotic phase, each cycle of DNA synthesis produces an exact doubling of all the chromosomes, resulting in cells containing DNA contents ranging from 8N to 128N in a single, highly lobulated nucleus. Endomitosis is not simply the absence of mitosis, but is rather a series of recurrent cycles of aborted mitosis (17). The cell cycle kinetics of endomitotic cells is also unusual, with a shortened G1 phase, a relatively normal S phase of DNA synthesis, a short G2 phase, and a very short modified mitosis phase (18, 19). During the last phase, chromosomes condense, the nuclear membrane breaks down, and mitotic spindles form upon which the replicated chromosomes assemble. However, individual chromosomes fail to complete their normal migration to opposite poles of the cell, the spindle dissociates, the nuclear membrane reforms around the entire chromosomal complement, and the cell again enters G1 phase. Endomitosis departs from a normal mitotic cell cycle at cytokinesis, when furrow invagination aborts short of cell abscission (20, 21)

As endomitosis is a modified form of the cell cycle, one might suspect that genes involved in normal cell cycle regulation would play an important role in endomitosis. Indeed, many of the genes that control the normal cell cycle are also required for the endomitotic cycle. For example, gain-of-function of cyclin D1 (CCND1) and cyclin D3 (CCND3) increases the polyploidy state of MKs in vivo (22–25), while loss of function of cyclin D1 in primary murine megakaryocytes induces low polyploidy (26). Similarly, loss of cyclin E (CCNE) in mice leads to defective endoreplication of megakaryocytes as well as trophoblast giant cells (27), while increased expression of cyclin E enhances ploidy of megakaryocytes in transgenic animals (22). In the same manner, it is likely that genes that normally restrict cell cycle progression also restrain polyploidization of megakaryocytes. Evidence in support of this model include the observations that increased expression of p21, induced by loss of SCL/tal1, blocked endomitosis of murine primary megakaryocytes (28) and knockdown of p19 in human CD34+ cultures resulted in high polyploidy MKs, while its over-expression caused a decrease in polyploidy (29).

Since polyploid cells are genetically unstable and can progress to aneuploidy and promote tumors, organisms have developed ways to minimize this process. The prevailing model has been that cells maintain a checkpoint, which monitors the numbers of chromosomes and results in p53-dependent cell cycle arrest of tetraploid cells. However, a number of studies suggest that normal cells are instead protected from polyploidy by activation of a stress checkpoint, which stabilizes p53 and leads to cell cycle arrest (30). The absence of data to associate polyploidization with cellular stress in megakaryocytes may provide an explanation for why this lineage circumvents the cell cycle arrest that is seen in normal cells.

The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism that ensures that cells with misaligned chromosomes do not exit mitosis. The ability of the checkpoint to monitor the status of chromosome alignment is achieved by assigning checkpoint proteins to the kinetochore, a macromolecular complex that resides at centromeres of chromosomes and establishes connections with spindle microtubules. The SAC prevents cell cycle progression by negatively regulating CDC20 and inhibiting the activation of the polyubiquitylation activities of anaphase promoting complex (APC), which degrades proteins such as securin. Failure in the function of the checkpoint results in polyploidy (31). Genes found to be required for spindle checkpoint control include the kinases BUB1 and BUBR1, the WD40 repeat containing protein BUB3, which directs the localization of the complex to kinetochores, and the APC inhibitors MAD2/CDC20. For example, loss-of-function of BUB1, BUB3 and MAD2 results in increased polyploidy (32, 33). Moreover, although homozygous loss of Bubr1 leads to embryonic lethality, Bubr1 heterozygous mutant mice displayed splenomegaly and extramedullary megakaryopoiesis with a marked increase in polyploidization (34). It is important to note that haplo-insufficiency of BUBR1 selectively induced polyploidy of megakaryocytes, underscoring the unique sensitivity of MKs to this process.

The chromosome passenger complex (CPC) includes Aurora-B (AURKB), inner centromere protein (INCENP), surviving (BIRC5) and borealin (CDCA8). The CPC localizes at centromeres in metaphase and then translocates to the midzone late in mitosis (35). The CPC is important for the recruitment and proper localization of SAC proteins and required for spindle checkpoint function. Based on this important function, one might expect that alterations in the CPC would affect megakaryocyte development. Indeed, changes in survivin expression have been associated with aberrant megakaryocyte polyploidization: overexpression of survivin in normal murine bone marrow progenitors antagonized megakaryocyte polyploidization, growth, and maturation (36), whereas loss of survivin in primary bone marrow progenitors resulted in increased polyploidy of megakaryocytes (37). These findings suggest the tight regulation of survivin expression is important for megakaryocyte development.

The function of Aurora-B in endomitosis has also been under intense study. Geddis and Kaushansky found that Aurora-B was expressed and properly localized during endomitosis of human megakaryocytes derived from CD34+ cells (38), while Zhang and colleagues reported that Aurora B was absent or mislocalized in megakaryocytes derived from mouse bone marrow (39). The discrepancy has been attributed to species-specific differences or to differential antibody sensitivity. Independently, Lordier et al. showed that inhibition of Aurora-B kinase activity induced apoptosis of low polyploid MKs, caused mis-segregation of chromosomes, mitotic failure and an increased proportion of high polyploidy human MKs (21).

Precise activation of Rho-GTPase-ROCK signaling and its downstream targets, such as kinesin, myosin, tubulin and actin, are of critical importance in cytokinesis (40). Unlike diploid MKs, RhoA and F-actin are partially concentrated at the site of furrowing in polyploidy MKs and inhibition of the Rho/Rock pathway caused the loss of F-actin from the midzone and increased the degree of MK polyploidization (20). A direct role for regulating RhoA-ROCK signaling has recently been demonstrated for polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) (41–43). PLK1 is important for precise localization of ECT2 (41, 43), a GTP exchange factor for RhoA, to the central spindle. It has been reported that PLK1 expression is absent in polyploid MKs, although expression of other cell cycle proteins is similar in both populations (44). Forced expression of Plk-1 during MK differentiation from murine bone marrow cells was associated with decreased polyploidization, suggesting that PLK1 is indeed a regulator of this process in differentiating MKs (44).

Transcriptional regulation of megakaryopoiesis

Lineage-specific transcription factors play essential roles in the development of megakaryocytes. Importantly, many human and murine leukemias are associated with mutations, chromosomal translocations or viral insertions in these factors (45). This finding suggests that the maintenance of normal transcriptional program plays a important role in normal hematopoiesis. In this section, we will highlight several key MK transcription factors, such as GATA-1, FLI-1 (and other ETS factors), SCL, RUNX1 and SRF.

GATA-1

GATA-1 is a zinc finger transcription factor, which binds the consensus motif WGATAR motif. GATA-1 is absolutely required for normal development of megakaryocytes and platelets. Mice that lack Gata-1 expression in the megakaryocyte lineage (Gata1low or Gata1 knockdown mice) develop megakaryocytes, but they are abnormal in many respects, such as reduced polyploidization and excessive proliferation (26, 46, 47). Restoration of cyclin D1 expression, which is diminished in Gata-1 deficient cells, resulted in a dramatic increase in megakaryocyte size and DNA content (26). However, terminal differentiation was not rescued, suggesting that cyclin D1 is a mediator of polyploidization, but not of terminal differentiation. The finding also confirms the notion that that polyploidization and terminal maturation can be uncoupled. The GATA-1 protein consists of two zinc finger DNA binding domains, the N- and C-fingers, and an N-terminal activation domain. The N-finger mediates the interaction between GATA-1 and its partner FOG-1, which is also essential for megakaryopoiesis. FOG-1-deficient mice do not generate any cells of the megakaryocyte lineage (48). Mice that express a Gata-1 mutant that fails to interact with Fog-1 show a phenotype that resembles that of Gata-1 knockdown mice, suggesting that FOG-1 has GATA-1-independent functions, likely mediated through GATA-2 (49). Furthermore, mutations in the N-terminal zinc finger that led to the dissociation of the GATA-1/FOG-1 interaction, or to a decreased ability of GATA-1 to bind DNA, are associated with a spectrum of benign hematologic diseases in humans, including dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia (50), gray platelet syndrome (51) and congenital erythropoietic porphyria (52). NuRD interacts with the extreme N-terminus of FOG-1, and this interaction is important for GATA-1/FOG-1 mediated gene activation and repression (53). Moreover, Gregory et al reported that mice in which the Fog-1/Nurd interaction is disrupted produce MK progenitors that give rise to significantly fewer and less mature MK in vitro while retaining multi-lineage capacity, capable of generating mast cells and other myeloid lineage cells (54). Further studies showed that NuRD could bind and repress expression of genes characteristic of mast cell lineage. These findings suggest the interaction between NuRD and GATA-1/FOG-1 is required to maintain lineage fidelity in megakaryocyte development. The mutations in N terminal domain of GATA-1 will be discussed in the AMKL section of this review.

RUNX1/AML1

The complex of RUNX1 and CBFβ participates in programming hematopoietic ontogeny and represents the most common mutational target in human acute leukemia (55). RUNX1 and CBFβ retain high expression during megakaryocytic differentiation of MEP, but are down-regulated during the early phases of erythroid differentiation (56–58). The absence of RUNX1 has profound effects on the polyploidization and terminal maturation of megakaryocytes, leading to a significant reduction in polyploidization and platelet formation in vivo (59–61). Expression of the proper amount of RUNX1 is also essential for normal platelet homeostasis, as Runx1-heterozygous animals display a mild thrombocytopenia and decrease in long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (62). Mutations of RUNX-1 are associated with familial platelet disorder with predisposition to AML and sporadic cases of AML (63–65).

ETS factors

Several ETS factors, including FLI1, GABPα, ETS1, ETS2, ERG and TEL1 directly contribute to murine megakaryocytic development. The importance of TEL1 was highlighted by the finding that deletion of Tel1 within erythroid and megakaryocytic cells in the GATA-1-CRE::Tel1 floxed mouse strain causes a 50% drop in platelet counts with no effect on hemoglobin levels (66). FLI-1 is also necessary for megakaryocyte development. Homozygous loss of Fli1 in mice is embryonic lethal and results in severe dysmegakaryopoiesis (67, 68). Accumulated evidence indicates that FLI-1 is as positive regulator of megakaryopoiesis (67, 68), while being a negative regulator of erythroid differentiation (69, 70). Fli1−/− mice show a marked decrease in the mature:immature MK ratio compared with wild-type (WT) littermates, consistent with a critical role in later stages of MK differentiation. Another Ets factor, GABPα is a regulator of early megakaryocyte-specific genes, including αIIb and c-mpl (71). The ratio of GABPα/FLI1 decreases with megakaryocyte maturation, consistent with a dependence of early genes on GABPα and late megakaryocyte-specific genes on FLI-1 for their expression. ERG is a Ets factor encoded on human chromosome 21 (Hsa21) and expressed within megakaryocytes. Stankiewicz et al reported that ERG facilitated the expansion of megakaryocytes from wild-type, Gata1-knockdown, and Gata1s knockin progenitors, but could not overcome the differentiation block characteristic of the Gata1-knockdown megakaryocytes (72). Overexpression of ERG immortalized Gata1-knockdown and Gata1s-knockin, but not wild-type, fetal liver progenitors. Moreover, high level overexpression of ERG resulted in myeloid leukemia in mice, with infiltration of CD41 positive cells in the spleen (73). These latter findings highlight the important role for ERG in Down syndrome AMKL.

SCL/tal-1

It is well established that SCL is important for the development of HSCs. Mice with a conditional knockout of SCL in hematopoietic cells display perturbed megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis with a loss of early progenitor cells in both lineages (74). These mice consistently show a low platelet count and hematocrit compared with controls. The finding suggests that SCL is indispensable for the development of both megakaryocyte and erythroid lineage. Tripic et al reported that SCL, along LMO2, Ldb1 and E2A, form a complex with GATA-1 at all activating GATA elements in megakaryocytes (75). In striking contrast, at sites where GATA-1 functions as a repressor, the SCL complex is absent. Important MK targets of SCL include p21 (28) and MEF2C (76). Of note, Mef2c deficient mice display similar MK defects as SCL-deficient animals.

SRF

Serum response factor (SRF) is a MADS-box transcription factor that is critical for muscle differentiation. Interest in the function of SRF in megakaryocyte development was kindled when Mkl1, a cofactor of SRF, was discovered as part of the t(1;22) translocation in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (77). The importance of SRF in megakaryocyte maturation and platelet formation were revealed by two groups that used Srf floxed mice and PF4-cre mice or MX-cre mice (78)(79). Srf-deficient mice showed a reduction in platelet count and an increase of megakaryocyte progenitors in the BM by FACS analysis and CFU-Mk. These mice also have defects in platelet function.

Megakaryocytes and the Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)

The MPNs include the ‘classical MPNs’ chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) (80), as well as chronic eosinophilic leukemia/hypereosinophilic syndrome (CEL/HES), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), Ph-negative atypical CML, chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) and systemic mastocytosis. Many studies have demonstrated multi-lineage clonal hematopoiesis in the different MPNs (81–83), consistent with the notion that MPNs originate in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment.

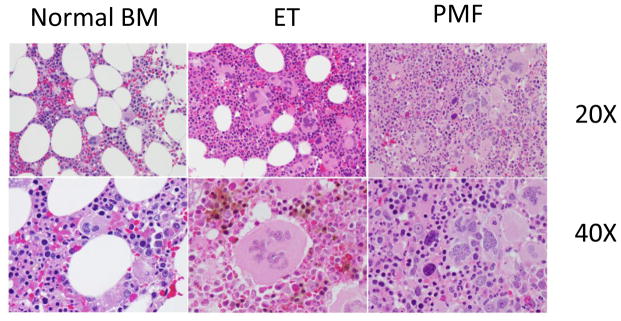

Hyperproliferation of megakaryocytes and alterations in platelet counts are features of ET and PMF. ET is often discovered incidentally on blood counts in asymptomatic patients. The major causes of morbidity and mortality are bleeding or thrombotic complications and rarely evolution to AML. Bone marrow pathology displays increased cellularity with marked megakaryocytic hyperplasia. There are frequently giant megakaryocytes with increased polyploidy, but the overall morphology of megakaryocytes is fairly normal (Figure 2). In contrast, individuals with PMF present with splenomegaly, dysplastic megakaryopoiesis and marked bone marrow fibrosis. The peripheral blood often shows teardrop shaped erythrocytes and large platelets. The bone marrow shows increased deposition of reticulin fibers and numerous morphologically abnormal megakaryocytes with multi-lobed nuclei. PMF may progress rapidly to AML, with nearly 20% patients transforming within 10 years (84).

Figure 2. The megakaryocyte lineage is abnormal in both ET and PMF.

Bone marrow sections from a healthy individual (left), and patients with ET (middle) or PMF (right). Top, 20X, middle 40X original magnification. Note that ET megakaryocytes are typically larger than normal, increased in number, and contain chromatin that resembles leaves. In contrast, PMF megakaryocytes are small, dysplastic, and contain chromatin that resembles clouds. Images courtesy of Dr. Sandeep Gurbuxani (University of Chicago).

Although MPNs were first described in 1951 by William Dameshek (80), the genetic basis for the disease remained elusive until 2005 when a somatic point mutation in JAK2 tyrosine kinase (JAK2V617F) was identified in 50% of ET and PMF and 95% in PV patients (85–88). JAK2 is a member of the Janus family of cytoplasmic non-receptor tyrosine kinases, which also includes JAK1, JAK3 and TYK2. The JAK kinases have seven homologous domains (JH1–7), and a catalytically inactive pseudokinase domain (JH2). The predominant JAK2 mutation is a guanine-to-thymidine substitution, which results in a substitution of valine for phenylalanine at codon 617 (JAK2V617F) within the JH2 domain. The V617F mutation abrogates the auto-inhibitory activity of the JH2 domain (89), and results in constitutive kinase activity (85–88, 90). The mutation is present in myeloid cells, but not germline DNA in patients with MPN (87, 88), demonstrating that JAK2V617F is a somatic mutation that is acquired in the hematopoietic compartment. When expressed in vitro JAK2V617F, but not the wild-type protein, is constitutively phosphorylated (88).

How does a single disease allele contribute to the pathogenesis of PV, ET and PMF, three distinct clinical disorders? Several lines of evidence suggest that high dosage of JAK2V617F, which results in high level of JAK2 signaling, favors an erythroid phenotype and low dosage of JAK2V617F favors a megakaryocyte phenotype. First, homozygosity for JAK2V617F is much more common in PV than in ET (85–88, 91). Second, mutations of JAK2 exon 12, which are associated with stronger downstream JAK2 signaling compared to JAK2V617F, are found in patients with PV, but not in those with ET (92). Third, in vivo studies support the gene dosage hypothesis. For example, transplantation of JAK2V617F transduced mouse bone marrow cells with high level expression resulted in a uniform PV phenotype without thrombocytosis (93), Furthermore, transgenic mice that express a relatively low level of JAK2V617F, below that of wild-type allele, developed ET-like disease while mice that express much higher levels caused a PV-like disease (94). A similar induction of thrombocytosis was also seen in JAK2V617F transplant recipients with the lowest level of JAK2 expression (95).

Research has shown that STAT1 signaling promotes megakaryopoiesis and contributes to polyploidization (96). However, a connection between STAT1 and MPN was only recently discovered. An exciting study by Anthony Green and colleagues revealed that the activation status of STAT1 could predict the phenotype of JAK2V617F disease (97). By comparing clonally-derived mutant and wild-type cells from individual patients, they showed that enhanced activation of STAT1 was associated with an ET phenotype whereas downregulation of STAT1 activity in was associated with a PV-like phenotype. It is still remained to be determined whether the increased activation of STAT1 in ET is a result of change of JAK2V617F protein level.

Beyond its effects on the STAT signaling cascade, JAK2V617F was recently shown to promote changes in chromatin structure, resulting in differential gene expression (98). The authors reported that JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3, leading to reduced binding of HP1α in human hematopoietic cells. Further, Inhibition of JAK2 activity decreased the phosphorylation of H3Y41 at certain promoters, including that of the leukemia oncogene lmo2 (98), More recently, Griffiths et al found that compared to ES cells with wild type JAK2, levels of chromatin-bound HP1α were lower in JAK2V617F mutant cells, but these levels increased following inhibition of JAK2, coincident with a global reduction in histone H3Y41 phosphorylation (99). JAK2 inhibition also reduced levels of the pluripotency regulator Nanog, with a reduction in H3Y41 phosphorylation and concomitant increase in HP1α levels at the Nanog promoter. These findings highlight the nuclear function of JAK2. Further genome wide epigenetic and gene expression studies to probe JAK2 nuclear function will shed light on pathogenesis of JAK2V617F MPNs.

This past year, four groups reported the creation of knock-in mouse models in which the mutant JAK2 V617F encoding allele was inserted into the germline in such a way that expression could be activated in a conditional fashion (100–103). Three of these groups replaced the wild-type allele with the mutant murine JAK2 gene. In all of these cases, animals developed similar phenotypes that mimicked PV (100, 102, 103) In contrast, the one animal strain created with the human JAK2 gene developed an ET-like phenotype (101). In this latter mouse, the human JAK2 cDNA was incorporated into the murine locus, an event that itself may lead to changes in gene expression and phenotype. Thus, any direct comparisons of the four lines should be done with caution.

It is interesting to focus for a moment on one of the JAK2V617F knock-in models that develops a lethal myeloproliferative neoplasm (103). In this model, the mice were engineered so that the wild-type exon 14 is flanked by loxP sites, with a mutated version of the exon positioned downstream in an inverted fashion. Upon exposure to cre recombinase, the wild-type exon was deleted and replaced by inverted copy of the mutated exon, leading to expression of JAK2V617F protein. By breeding floxed heterozygous mice to the E2A-Cre strain, which leads to germline excision in early embryos, they generated JAK2V617F expressing animals. All of these animals developed a lethal MPN characterized by elevated hematocrit, splenomegaly, and a median survival of 146 days. Flow cytometry and histology of the bone marrow and spleen confirmed that the mice developed marked erythroid and mild megakaryocytic hyperplasia. Together, the pathologic findings revealed that the mice develop an MPN that is closely reminiscent of human PV. Given that the MPN in these animals was transplantable to primary recipient mice, Mullally et al were able to identify the nature of the disease-initiating cell. They showed that JAK2 mutant stem cells exhibited a minor competitive advantage in recipients, that the LSK population, and not more differentiated progenitor subsets, contained the repopulating activity, and that the presence of a minority of JAK2 V617F LSK cells is sufficient to cause the PV phenotype. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the study, made possible by the ability of the LSK population to transplant disease, was the discovery that inhibition of JAK2 kinase did not eradicate the MPN-initiating population. Although treatment of primary diseased animals with the JAK inhibitor TG101348 led to significant reductions in spleen size and numbers of erythroid progenitors, the LSK population of TG101348 treated animals retained the ability to induce MPN in recipient mice. These studies demonstrate that JAK inhibition with this agent does not eliminate the MPN-initiating population in vivo and thus has profound implications for human therapy.

The common occurrence of JAK2 mutations in patients with MPNs underscores the importance of JAK2 signaling in the pathogenesis of these diseases. However, nearly half of ET and PMF patients do not harbor a JAK2 mutation. Shortly after discovery of the JAK2 mutations, activating mutations in tryptophan 515 of the thrombopoietin receptor, MPL, were identified in a subset of JAK2 wild-type ET and PMF cases (104–106). These mutations occur in a subset of patients with JAK2V617F-negative ET and PMF, including 8.5% of JAK2V617F-negative ET patients (107), and approximately 10% of JAK2V617F-negative PMF patients (104–106). Four patients have also recently been described with somatic MPLS505N mutations (107), an allele which had previously been associated with inherited thrombocytosis (108). MPLW515-positive ET patients have higher platelet counts and lower hemoglobin levels than JAK2V617Fpositive ET patients (107, 109), and MPLW515-positive PMF patients present with more severe anemia (110). Moreover, endogenous megakaryocyte colonies, but not endogenous erythroid colonies, can be grown from MPLW515-positive patient cells. These findings may be due to the fact that MPL is not expressed during terminal erythroid differentiation.

Since both JAK2V617F and MPLW515 activate JAK/STAT signaling, it is logical to surmise that loss of negative regulators of the pathway may also be associated with MPNs. Indeed mutations in LNK [also known as Src homology 2 B3 (SH2B3)], a protein that downregulates JAK–STAT signaling after erythropoietin receptor (EPO-R) or MPL activation (111–113)., have been identified in both ET and PMF patients with a frequency between 3 and 6% (114–117). LNK possesses a number of protein-protein interaction domains: a proline-rich amino-terminus, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, a Src homology 2 (SH2) domain and many potential tyrosine phosphorylation motifs (118). Human LNK mutations appear to cluster in the pleckstrin homology and SH2 domains, which physically interact with the cell membrane and EPO-R/MPL/JAK2, respectively. Loss-of-function mutations of LNK were also found in JAK2 mutation negative “idiopathic” erythrocytosis or polycythemia vera (114). Of note, mice with complete loss of LNK display a number of features in common with human MPN, including an exaggerated response to cytokines, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis (111, 113, 119). It should be noted that LNK mutations and JAK2V617 are not mutually exclusive and may co-occur in the same patient (116). LNK mutations were recently shown to be acquired either early or late during the course of clonal evolution (117). Other mutations identified in MPNs include TET2 (120), ASXL1 (121), IDH1/IDH2 (122, 123), CBL (124), IKZF1 (125) and EZH2 (126). The functional consequences of these mutations with respect to MPN initiation or progression are largely unknown, but are the subject of intense research.

Novel Therapies for MPNs

The discovery of JAK2V617F and other JAK-STAT activating mutations, including mutations in exon 12 of JAK2, MPL, and LNK, has generated enormous interest in the development and therapeutic use of small molecule JAK2 inhibitor–targeted therapy in these diseases. A handful of compounds are currently in clinical development for MPNs, including INCB018424, TG101348, CEP-701, SB1518 and CYT387 (127). These JAK inhibitors exhibit differential inhibitory activities against the JAK family members, while others are less selective. For example, INCB018424 inhibits predominantly JAK1, whereas CEP-701 and TG101348 inhibit FLT3 in addition to JAK2. Data from ongoing clinical studies show that JAK inhibitors provide symptomatic relief to patients, including spleen size reduction and improvement of constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, and fever (128, 129). The improvement of constitutional symptoms by INCB018424 may be the result of a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by inhibition of JAK1 (128, 129). Whether this is the main mechanism of action of JAK inhibitors in general remains to be determined. Indeed, longer-term studies are required to determine the full potential of JAK2 inhibitors and to show whether they will have an impact on survival in MPNs. Apart from JAK inhibitors, several other therapies are under study for use as single agents or in combination with JAK inhibitors. These include HSP90 inhibitors (e.g. PU-H71 (130), histone deacetylase inhibitors e.g. pabinostat (131), and PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors (e.g. everolimus) (132). Given these new drugs and other lines of clinical investigation, there are many reasons to be optimistic about the prospects for improved therapies for MPNs.

Acute Megakaryocytic Leukemia (AMKL)

Acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMKL) is a rare subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in which the leukemic cells are derived from the megakaryocyte lineage. The three major subgroups of AMKL include infants with Down syndrome (DS-AMKL), children without DS (non-DS pediatric AMKL) and adults (adult AMKL). The incidence in the pediatric population is 1:500 children with DS and between 5–7% of pediatric AML cases overall in children without DS, while the incidence adults is estimated to be approximately 1% of AML cases (133–135).

DS-AMKL, non-DS-AMKL and adult AMKL are distinct from one another in that they have different genetic abnormalities and different outcomes. DS-AMKL often presents by age 2 with a myelodysplastic phase that includes thrombocytopenia. Bone marrow aspiration is often difficult, with fibrosis detected on bone marrow biopsy (136, 137). The prognosis of DS-AMKL is favorable, with an approximately 80% cure rate (138–140). This outcome is based on the enhanced sensitivity of DS-AMKL blasts to chemotherapeutic drugs, especially cytarabine (ARA-C) (141). On the other hand, children with non-DS-AMKL fare worse, with a 5-year EFS of 22–28% (135, 142). The prognosis of adult AMKL is even worse, with a median survival of approximately 10 months (133).

Multiple genes and pathways have been implicated in the etiology of the different forms of AMKL. In DS-AMKL, trisomy 21 and somatic mutations in the hematopoietic transcription factor gene GATA1 are found in nearly every patient (143). GATA1 mutations, which include short deletions, insertions, and point mutations clustered within exon 2, are a key step in the pathogenesis of DS-AMKL (144). In every case, the mutations lead to a block in expression of the full-length protein, but allow for production of a shorter isoform, GATA1s. Expression of GATA1s alone is not sufficient to induce leukemia, as humans with inherited mutant alleles fail to develop leukemia (145). However, in mice, expression of GATA-1s in place of GATA-1 is sufficient to cause hyperproliferation of yolk sac and fetal liver megakaryocyte progenitors (146). Distinct cytogenetic abnormalities, including t(1;22)(p13;q13), which leads to expression of the OTT-MAL fusion protein, t(9;11), t(10;11) and +8 are present in cases of non-DS pediatric AMKL (143). Similar to MPNs, alterations in tyrosine kinase signaling are likely necessary for AMKL. JAK3 mutations were originally identified in the DS-AMKL cell line, CMK, as well as in two DS-AMKL specimens, and were later detected in other DS-AMKL cases (147–152). Apart from other rare mutations in c-MPL, c-KIT, JAK2, and FLT3, no other specific chromosomal rearrangements or genetic mutations have been identified in adult AMKL (143, 147). Of note, recent studies have shown that pediatric AMKL shows many more copy number alterations than other forms of AML (153). However, how these changes influence the disease remain unknown. Rare instances of FLT3 mutations in AMKL do not influence prognosis (154). Recent studies have implicated dysregulation of miR-125b-2, which is overexpressed in AMKL relative to normal megakaryocytes, in DS-AMKL (155).

Two microarray studies comparing primary DS-AMKL versus non-DS AMKL specimens found 76 genes that discriminate between DS and non-DS AMKL. Genes encoding erythroid markers, such as glycophorin A and CD36, appear to be significantly overexpressed in DS-AMKL (156, 157). Further analysis of the gene expression data revealed that there is an overall increase in expression of chromosome 21 genes in DS-AMK, compared to non-DS AMKL (157). Forty-seven chromosome 21 genes were found to contribute to the enrichment by gene set enrichment analysis. However, the distinction between the two types of AMKL was not solely driven by differences in expression of chromosome 21 genes. The second study found that only 7 of 551 differentially expressed genes were on chromosome 21 (156).

Non-DS pediatric AMKL is characterized by an expansion of megakaryoblasts within the bone marrow and is frequently accompanied by hepatosplenomegaly, myelofibrosis and pancytopenia (158–160). The majority of cases are associated with the t(1;22) translocation, which results in fusion of the RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15; aka OTT) and MKL1 (aka MAL) genes (77, 161). The localization and function of MAL, a coactivator of serum response factor (SRF) with strong transcriptional activation properties, is deregulated by fusion with OTT (162, 163). OTT is related to the SHARP transcription factor that acts in transcriptional repression complexes in canonical Notch signaling pathways (164, 165). OTT may also inhibit myeloid differentiation (166). A conditional knockin of the OTT-MAL fusion protein at its endogenous promoter resulted in deregulated transcriptional activity of the canonical Notch signaling pathway and abnormal fetal megakaryopoiesis. Cooperation between OTT-MAL and an activating mutation of MPL, but not the OTT-MAL knockin alone, efficiently induced a short-latency highly penetrant AMKL that recapitulates the human phenotype (167). Other cytogenetic abnormalities have been observed, including t(10;11), which leads to the CALM–AF10 fusion(168), t(9;11), +8 or +21 (135).

Adult AMKL is a rare malignancy that comprises nearly 1% of adult AML cases (133, 134). Similar to the other subtypes of AMKL, adult AMKL is characterized by the excessive production of immature megakaryoblasts within the bone marrow and extensive myelofibrosis. Peripheral blood features frequently include anemia and thrombocytopenia. Adult AMKL frequently arises in individuals with an antecedent blood disorder or myelodysplastic syndrome (169). Although some patients achieve complete remission, the long-term outcome is significantly worse for adult AMKL than other forms of adult AML, with a median survival of 40 weeks or less (133, 134, 169).

To date, no specific chromosomal rearrangements or genetic mutations have been found in adult AMKL. In one study, it was noted that nearly 50% of patients had one or more cytogenetic abnormalities, including −5, −7, +8 or 11q involvement (169). These findings partially explain the poor outcome of this subtype of AMKL, although the poor prognosis is not fully dependent on cytogenetic abnormalities. Multiple studies have now reported that the tyrosine kinases JAK2 or JAK3 are mutated in a subset of AMKL patients, suggesting that perhaps JAK inhibitors should be considered. Given the poor prognosis for all patients with AMKL without DS, new, targeted therapies are desperately needed.

Summary and perspective

Megakaryocytes have been recognized as rare marrow cells for nearly 2 centuries, but it was the elegant studies of Howell in 1890 and his coining of the term “megakaryocyte” that led to their broader appreciation as distinct entities. The field has entered a new age in which modern genetic and molecular biological tools are being applied to these unique cells both in situ and in vitro to tease out novel insights into their growth and differentiation. With this increasing knowledge base, it is likely that we will soon know the complete genetic defects related to abnormal megakaryopoiesis, and will be in a strong position to develop new therapeutics for both excessive and inefficient megakaryopoiesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sandeep Gurbuxani for critical review and for providing the images used in figure 2. We also thank the reviewers for their helpful suggestions. This review was supported in part by grants from the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the National Cancer Institute (CA101774).

References

- 1.Lichtman MA, et al. Williams manual of hematology. 8. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanz L, et al. Identification of human megakaryocytes derived from pure megakaryocytic colonies (CFU-M), megakaryocytic-erythroid colonies (CFU-M/E), and mixed hemopoietic colonies (CFU-GEMM) by antibodies against platelet associated antigens. Blut. 1982;45(4):267–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00320194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakahata T, Gross AJ, Ogawa M. A stochastic model of self-renewal and commitment to differentiation of the primitive hemopoietic stem cells in culture. J Cell Physiol. 1982;113(3):455–458. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akashi K, et al. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404(6774):193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reya T, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa M. Differentiation and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1993;81(11):2844–2853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91(5):661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debili N, et al. Characterization of a bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor in human bone marrow. Blood. 1996;88(4):1284–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papayannopoulou T, et al. Insights into the cellular mechanisms of erythropoietin-thrombopoietin synergy. Exp Hematol. 1996;24(5):660–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adolfsson J, et al. Upregulation of Flt3 expression within the bone marrow Lin(−)Sca1(+)c-kit(+) stem cell compartment is accompanied by loss of self-renewal capacity. Immunity. 2001;15(4):659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adolfsson J, et al. Identification of Flt3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121(2):295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsberg EC, et al. New evidence supporting megakaryocyte-erythrocyte potential of flk2/flt3+ multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 2006;126(2):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakorn TN, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. Characterization of mouse clonogenic megakaryocyte progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):205–210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262655099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tober J, et al. The megakaryocyte lineage originates from hemangioblast precursors and is an integral component both of primitive and of definitive hematopoiesis. Blood. 2007;109(4):1433–1441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tober J, McGrath KE, Palis J. Primitive erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis in the yolk sac are independent of c-myb. Blood. 2008;111(5):2636–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, et al. Thrombopoietin promotes mixed lineage and megakaryocytic colony-forming cell growth but inhibits primitive and definitive erythropoiesis in cells isolated from early murine yolk sacs. Blood. 2003;101(4):1329–1335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitrat N, et al. Endomitosis of human megakaryocytes are due to abortive mitosis. Blood. 1998;91(10):3711–3723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harker LA. Kinetics of thrombopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 1968;47(3):458–465. doi: 10.1172/JCI105742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebbe S, et al. Megakaryocyte maturation rate in thrombocytopenic rats. Blood. 1968;32(5):787–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lordier L, et al. Megakaryocyte endomitosis is a failure of late cytokinesis related to defects in the contractile ring and Rho/Rock signaling. Blood. 2008;112(8):3164–3174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lordier L, et al. Aurora B is dispensable for megakaryocyte polyploidization, but contributes to the endomitotic process. Blood. 2010;116(13):2345–2355. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliades A, Papadantonakis N, Ravid K. New roles for cyclin E in megakaryocytic polyploidization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(24):18909–18917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun S, et al. Overexpression of cyclin D1 moderately increases ploidy in megakaryocytes. Haematologica. 2001;86(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmet JM, et al. A role for cyclin D3 in the endomitotic cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(12):7248–7259. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmet JM, Toselli P, Ravid K. Cyclin D3 and megakaryocyte development: exploration of a transgenic phenotype. Stem Cells. 1998;16(Suppl 2):97–106. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530160713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muntean AG, et al. Cyclin D-Cdk4 is regulated by GATA-1 and required for megakaryocyte growth and polyploidization. Blood. 2007;109(12):5199–5207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-059378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng Y, et al. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114(4):431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chagraoui H, et al. SCL-mediated regulation of the cell-cycle regulator p21 is critical for murine megakaryopoiesis. Blood. 2011;118(3):723–735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilles L, et al. P19INK4D links endomitotic arrest and megakaryocyte maturation and is regulated by AML-1. Blood. 2008;111(8):4081–4091. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganem NJ, Storchova Z, Pellman D. Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito D, Matsumoto T. Molecular mechanisms and function of the spindle checkpoint, a guardian of the chromosome stability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;676:15–26. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6199-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakaya T, et al. Critical role of Pcid2 in B cell survival through the regulation of MAD2 expression. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5180–5187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vernole P, et al. TAp73alpha binds the kinetochore proteins Bub1 and Bub3 resulting in polyploidy. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(3):421–429. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, et al. BUBR1 deficiency results in abnormal megakaryopoiesis. Blood. 2004;103(4):1278–1285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruchaud S, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(10):798–812. doi: 10.1038/nrm2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurbuxani S, et al. Differential requirements for survivin in hematopoietic cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(32):11480–11485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500303102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen Q, et al. Survivin is not required for the endomitotic cell cycle of megakaryocytes. Blood. 2009;114(1):153–156. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geddis AE, Kaushansky K. Megakaryocytes express functional Aurora-B kinase in endomitosis. Blood. 2004;104(4):1017–1024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, et al. Aberrant quantity and localization of Aurora-B/AIM-1 and survivin during megakaryocyte polyploidization and the consequences of Aurora-B/AIM-1-deregulated expression. Blood. 2004;103(10):3717–3726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barr FA, Gruneberg U. Cytokinesis: placing and making the final cut. Cell. 2007;131(5):847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burkard ME, et al. Chemical genetics reveals the requirement for Polo-like kinase 1 activity in positioning RhoA and triggering cytokinesis in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4383–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowery DM, et al. Proteomic screen defines the Polo-box domain interactome and identifies Rock2 as a Plk1 substrate. EMBO J. 2007;26(9):2262–2273. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petronczki M, et al. Polo-like kinase 1 triggers the initiation of cytokinesis in human cells by promoting recruitment of the RhoGEF Ect2 to the central spindle. Dev Cell. 2007;12(5):713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yagi M, Roth GJ. Megakaryocyte polyploidization is associated with decreased expression of polo-like kinase (PLK) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(9):2028–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cantor AB, Orkin SH. Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: an affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene. 2002;21(21):3368–3376. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shivdasani RA, et al. A lineage-selective knockout establishes the critical role of transcription factor GATA-1 in megakaryocyte growth and platelet development. EMBO J. 1997;16(13):3965–3973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vyas P, et al. Different sequence requirements for expression in erythroid and megakaryocytic cells within a regulatory element upstream of the GATA-1 gene. Development. 1999;126(12):2799–2811. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsang AP, et al. Failure of megakaryopoiesis and arrested erythropoiesis in mice lacking the GATA-1 transcriptional cofactor FOG. Genes Dev. 1998;12(8):1176–1188. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang AN, et al. GATA-factor dependence of the multitype zinc-finger protein FOG-1 for its essential role in megakaryopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(14):9237–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142302099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crispino JD. GATA1 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16(1):137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tubman VN, et al. X-linked gray platelet syndrome due to a GATA1 Arg216Gln mutation. Blood. 2007;109(8):3297–3299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips JD, et al. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria due to a mutation in GATA1: the first trans-acting mutation causative for a human porphyria. Blood. 2007;109(6):2618–2621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miccio A, et al. NuRD mediates activating and repressive functions of GATA-1 and FOG-1 during blood development. EMBO J. 2010;29(2):442–456. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregory GD, et al. FOG1 requires NuRD to promote hematopoiesis and maintain lineage fidelity within the megakaryocytic-erythroid compartment. Blood. 2010;115(11):2156–2166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tracey WD, Speck NA. Potential roles for RUNX1 and its orthologs in determining hematopoietic cell fate. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11(5):337–342. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kundu M, et al. Role of Cbfb in hematopoiesis and perturbations resulting from expression of the leukemogenic fusion gene Cbfb-MYH11. Blood. 2002;100(7):2449–2456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elagib KE, et al. RUNX1 and GATA-1 coexpression and cooperation in megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood. 2003;101(11):4333–4341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorsbach RB, et al. Role of RUNX1 in adult hematopoiesis: analysis of RUNX1-IRES-GFP knock-in mice reveals differential lineage expression. Blood. 2004;103(7):2522–2529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ichikawa M, et al. AML-1 is required for megakaryocytic maturation and lymphocytic differentiation, but not for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells in adult hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):299–304. doi: 10.1038/nm997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Growney JD, et al. Loss of Runx1 perturbs adult hematopoiesis and is associated with a myeloproliferative phenotype. Blood. 2005;106(2):494–504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Putz G, et al. AML1 deletion in adult mice causes splenomegaly and lymphomas. Oncogene. 2006;25(6):929–939. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun W, Downing JR. Haploinsufficiency of AML1 results in a decrease in the number of LTR-HSCs while simultaneously inducing an increase in more mature progenitors. Blood. 2004;104(12):3565–3572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nucifora G, Rowley JD. AML1 and the 8;21 and 3;21 translocations in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1995;86(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song WJ, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):166–175. doi: 10.1038/13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peterson LF, Zhang DE. The 8;21 translocation in leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4255–4262. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hock H, et al. Tel/Etv6 is an essential and selective regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cell survival. Genes Dev. 2004;18(19):2336–2341. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hart A, et al. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13(2):167–177. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spyropoulos DD, et al. Hemorrhage, impaired hematopoiesis, and lethality in mouse embryos carrying a targeted disruption of the Fli1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(15):5643–5652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5643-5652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ano S, et al. Erythroblast transformation by FLI-1 depends upon its specific DNA binding and transcriptional activation properties. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(4):2993–3002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Athanasiou M, et al. FLI-1 is a suppressor of erythroid differentiation in human hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2000;14(3):439–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pang L, et al. Maturation stage-specific regulation of megakaryopoiesis by pointed-domain Ets proteins. Blood. 2006;108(7):2198–2206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stankiewicz MJ, Crispino JD. ETS2 and ERG promote megakaryopoiesis and synergize with alterations in GATA-1 to immortalize hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2009;113(14):3337–3347. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salek-Ardakani S, et al. ERG is a megakaryocytic oncogene. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4665–4673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hall MA, et al. The critical regulator of embryonic hematopoiesis, SCL, is vital in the adult for megakaryopoiesis, erythropoiesis, and lineage choice in CFU-S12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(3):992–997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237324100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tripic T, et al. SCL and associated proteins distinguish active from repressive GATA transcription factor complexes. Blood. 2009;113(10):2191–2201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gekas C, et al. Mef2C is a lineage-restricted target of Scl/Tal1 and regulates megakaryopoiesis and B-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2009;113(15):3461–3471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma Z, et al. Fusion of two novel genes, RBM15 and MKL1, in the t(1;22)(p13;q13) of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2001;28(3):220–221. doi: 10.1038/90054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halene S, et al. Serum response factor is an essential transcription factor in megakaryocytic maturation. Blood. 2010;116(11):1942–1950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ragu C, et al. The serum response factor (SRF)/megakaryocytic acute leukemia (MAL) network participates in megakaryocyte development. Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1227–1230. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dameshek W. Some speculations on the myeloproliferative syndromes. Blood. 1951;6(4):372–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fialkow PJ, Gartler SM, Yoshida A. Clonal origin of chronic myelocytic leukemia in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58(4):1468–1471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.4.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gilliland DG, et al. Clonality in myeloproliferative disorders: analysis by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(15):6848–6852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adamson JW, et al. Polycythemia vera: stem-cell and probable clonal origin of the disease. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(17):913–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197610212951702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tefferi A. Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(17):1255–1265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baxter EJ, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.James C, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kralovics R, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Levine RL, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saharinen P, Takaluoma K, Silvennoinen O. Regulation of the Jak2 tyrosine kinase by its pseudokinase domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(10):3387–3395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3387-3395.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ihle JN, Gilliland DG. Jak2: normal function and role in hematopoietic disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scott LM, et al. Progenitors homozygous for the V617F mutation occur in most patients with polycythemia vera, but not essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2006;108(7):2435–2437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scott LM, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wernig G, et al. Expression of Jak2V617F causes a polycythemia vera-like disease with associated myelofibrosis in a murine bone marrow transplant model. Blood. 2006;107(11):4274–4281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tiedt R, et al. Ratio of mutant JAK2-V617F to wild-type Jak2 determines the MPD phenotypes in transgenic mice. Blood. 2008;111(8):3931–3940. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lacout C, et al. JAK2V617F expression in murine hematopoietic cells leads to MPD mimicking human PV with secondary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2006;108(5):1652–1660. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang Z, et al. STAT1 promotes megakaryopoiesis downstream of GATA-1 in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(12):3890–3899. doi: 10.1172/JCI33010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen E, et al. Distinct clinical phenotypes associated with JAK2V617F reflect differential STAT1 signaling. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):524–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dawson MA, et al. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature. 2009;461(7265):819–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Griffiths DS, et al. LIF-independent JAK signalling to chromatin in embryonic stem cells uncovered from an adult stem cell disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(1):13–21. doi: 10.1038/ncb2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akada H, et al. Conditional expression of heterozygous or homozygous Jak2V617F from its endogenous promoter induces a polycythemia vera-like disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3589–3597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li J, et al. JAK2 V617F impairs hematopoietic stem cell function in a conditional knock-in mouse model of JAK2 V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2010;116(9):1528–1538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marty C, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasm induced by constitutive expression of JAK2V617F in knock-in mice. Blood. 2010;116(5):783–787. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mullally A, et al. Physiological Jak2V617F expression causes a lethal myeloproliferative neoplasm with differential effects on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(6):584–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pikman Y, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chaligne R, et al. New mutations of MPL in primitive myelofibrosis: only the MPL W515 mutations promote a G1/S-phase transition. Leukemia. 2008;22(8):1557–1566. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pardanani AD, et al. MPL515 mutations in myeloproliferative and other myeloid disorders: a study of 1182 patients. Blood. 2006;108(10):3472–3476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beer PA, et al. MPL mutations in myeloproliferative disorders: analysis of the PT-1 cohort. Blood. 2008;112(1):141–149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-131664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ding J, et al. Familial essential thrombocythemia associated with a dominant-positive activating mutation of the c-MPL gene, which encodes for the receptor for thrombopoietin. Blood. 2004;103(11):4198–4200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vannucchi AM, et al. Characteristics and clinical correlates of MPL 515W>L/K mutation in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2008;112(3):844–847. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Guglielmelli P, et al. Anaemia characterises patients with myelofibrosis harbouring Mpl mutation. Br J Haematol. 2007;137(3):244–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Takaki S, et al. Enhanced hematopoiesis by hematopoietic progenitor cells lacking intracellular adaptor protein, Lnk. J Exp Med. 2002;195(2):151–160. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tong W, Lodish HF. Lnk inhibits Tpo-mpl signaling and Tpo-mediated megakaryocytopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2004;200(5):569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Velazquez L, et al. Cytokine signaling and hematopoietic homeostasis are disrupted in Lnk-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2002;195(12):1599–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lasho TL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. LNK mutations in JAK2 mutation-negative erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1189–1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1006966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Oh ST, et al. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;116(6):988–992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pardanani A, et al. LNK mutation studies in blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms, and in chronic-phase disease with TET2, IDH, JAK2 or MPL mutations. Leukemia. 2010;24(10):1713–1718. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lasho TL, et al. Clonal hierarchy and allelic mutation segregation in a myelofibrosis patient with two distinct LNK mutations. Leukemia. 2011 doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rudd CE. Lnk adaptor: novel negative regulator of B cell lymphopoiesis. Sci STKE. 2001;2001(85):pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.85.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bersenev A, et al. Lnk constrains myeloproliferative diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):2058–2069. doi: 10.1172/JCI42032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Delhommeau F, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Carbuccia N, et al. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2183–2186. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Green A, Beer P. Somatic mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 in the leukemic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):369–370. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tefferi A, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24(7):1302–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grand FH, et al. Frequent CBL mutations associated with 11q acquired uniparental disomy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113(24):6182–6192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jager R, et al. Deletions of the transcription factor Ikaros in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24(7):1290–1298. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ernst T, et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):722–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tefferi A, Vainchenker W. Myeloproliferative neoplasms: molecular pathophysiology, essential clinical understanding, and treatment strategies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):573–582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Verstovsek S. Therapeutic potential of Janus-activated kinase-2 inhibitors for the management of myelofibrosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):1988–1996. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pardanani A, et al. JAK inhibitor therapy for myelofibrosis: critical assessment of value and limitations. Leukemia. 2011;25(2):218–225. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marubayashi S, et al. HSP90 is a therapeutic target in JAK2-dependent myeloproliferative neoplasms in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3578–3593. doi: 10.1172/JCI42442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang Y, et al. Cotreatment with panobinostat and JAK2 inhibitor TG101209 attenuates JAK2V617F levels and signaling and exerts synergistic cytotoxic effects against human myeloproliferative neoplastic cells. Blood. 2009;114(24):5024–5033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Guglielmelli P, et al. Safety and efficacy of everolimus, a mTOR inhibitor, as single agent in a phase 1/2 study in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2011;118(8):2069–2076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tallman MS, et al. Acute megakaryocytic leukemia: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Blood. 2000;96(7):2405–2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pagano L, et al. Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia: experience of GIMEMA trials. Leukemia. 2002;16(9):1622–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Barnard DR, et al. Comparison of childhood myelodysplastic syndrome, AML FAB M6 or M7, CCG 2891: report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(1):17–22. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hasle H, et al. Myeloid leukemia in children 4 years or older with Down syndrome often lacks GATA1 mutation and cytogenetics and risk of relapse are more akin to sporadic AML. Leukemia. 2008;22(7):1428–1430. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Langebrake C, Creutzig U, Reinhardt D. Immunophenotype of Down syndrome acute myeloid leukemia and transient myeloproliferative disease differs significantly from other diseases with morphologically identical or similar blasts. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217(3):126–134. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-836510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Creutzig U, et al. AML patients with Down syndrome have a high cure rate with AML-BFM therapy with reduced dose intensity. Leukemia. 2005;19(8):1355–1360. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rao A, et al. Treatment for myeloid leukaemia of Down syndrome: population-based experience in the UK and results from the Medical Research Council AML 10 and AML 12 trials. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(5):576–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gamis AS, et al. Increased age at diagnosis has a significantly negative effect on outcome in children with Down syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Cancer Group Study 2891. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(18):3415–3422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zwaan CM, et al. Different drug sensitivity profiles of acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia and normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells in children with and without Down syndrome. Blood. 2002;99(1):245–251. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gamis AS. Acute myeloid leukemia and Down syndrome evolution of modern therapy--state of the art review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wickrema A, Crispino JD. Erythroid and megakaryocytic transformation. Oncogene. 2007;26(47):6803–6815. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Vyas P, Crispino JD. Molecular insights into Down syndrome-associated leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328013e7b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hollanda LM, et al. An inherited mutation leading to production of only the short isoform of GATA-1 is associated with impaired erythropoiesis. Nat Genet. 2006;38(7):807–812. doi: 10.1038/ng1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Li Z, et al. Developmental stage-selective effect of somatically mutated leukemogenic transcription factor GATA1. Nat Genet. 2005;37(6):613–619. doi: 10.1038/ng1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Malinge S, Izraeli S, Crispino JD. Insights into the manifestations, outcomes, and mechanisms of leukemogenesis in Down syndrome. Blood. 2009;113(12):2619–2628. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-163501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Walters DK, et al. Activating alleles of JAK3 in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kiyoi H, et al. JAK3 mutations occur in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia both in Down syndrome children and non-Down syndrome adults. Leukemia. 2007;21(3):574–576. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.De Vita S, et al. Loss-of-function JAK3 mutations in TMD and AMKL of Down syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2007;137(4):337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sato T, et al. Functional analysis of JAK3 mutations in transient myeloproliferative disorder and acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia accompanying Down syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(5):681–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Cornejo MG, Boggon TJ, Mercher T. JAK3: a two-faced player in hematological disorders. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(12):2376–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Radtke I, et al. Genomic analysis reveals few genetic alterations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(31):12944–12949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903142106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Leow S, et al. FLT3 mutation and expression did not adversely affect clinical outcome of childhood acute leukaemia-a study of 531 Southeast Asian children by the Ma-Spore study group. Hematol Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hon.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Klusmann JH, et al. Developmental stage-specific interplay of GATA1 and IGF signaling in fetal megakaryopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2010;24(15):1659–1672. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ge Y, et al. Differential gene expression, GATA1 target genes, and the chemotherapy sensitivity of Down syndrome megakaryocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(4):1570–1581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Bourquin JP, et al. Identification of distinct molecular phenotypes in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(9):3339–3344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511150103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Carroll A, et al. The t(1;22) (p13;q13) is nonrandom and restricted to infants with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Blood. 1991;78(3):748–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bernstein J, et al. Nineteen cases of the t(1;22)(p13;q13) acute megakaryblastic leukaemia of infants/children and a review of 39 cases: report from a t(1;22) study group. Leukemia. 2000;14(1):216–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Rubnitz JE, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of recurrence in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2007;109(1):157–163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Mercher T, et al. Involvement of a human gene related to the Drosophila spen gene in the recurrent t(1;22) translocation of acute megakaryocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(10):5776–5779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101001498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Miralles F, et al. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell. 2003;113(3):329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Descot A, et al. OTT-MAL is a deregulated activator of serum response factor-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(20):6171–6181. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00303-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ariyoshi M, Schwabe JW. A conserved structural motif reveals the essential transcriptional repression function of Spen proteins and their role in developmental signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17(15):1909–1920. doi: 10.1101/gad.266203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]