Abstract

Background

Generalized triphasic waves (TPWs) occur in both metabolic encephalopathies and non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). Empiric trials of benzodiazepines (BZDs) or non-sedating AED (NSAEDs) are commonly used to differentiate the two, but the utility of such trials is debated. The goal of this study was to assess response rates of such trials and investigate whether metabolic profile differences affect the likelihood of a response.

Methods

Three institutions within the Critical Care EEG Monitoring Research Consortium retrospectively identified patients with unexplained encephalopathy and TPWs who had undergone a trial of BZD and/or NSAEDs to differentiate between ictal and non-ictal patterns. We assessed responder rates and compared metabolic profiles of responders and non-responders. Response was defined as resolution of the EEG pattern and either unequivocal improvement in encephalopathy or appearance of previously absent normal EEG patterns, and further categorized as immediate (within <2 h of trial initiation) or delayed (>2 h from trial initiation).

Results

We identified 64 patients with TPWs who had an empiric trial of BZD and/or NSAED. Most patients (71.9 %) were admitted with metabolic derangements and/or infection. Positive clinical responses occurred in 10/53 (18.9 %) treated with BZDs. Responses to NSAEDs occurred in 19/45 (42.2 %), being immediate in 6.7 %, delayed but definite in 20.0 %, and delayed but equivocal in 15.6 %. Overall, 22/64 (34.4 %) showed a definite response to either BZDs or NSAEDs, and 7/64 (10.9 %) showed a possible response. Metabolic differences of responders versus non-responders were statistically insignificant, except that the 48-h low value of albumin in the BZD responder group was lower than in the non-responder group.

Conclusions

Similar metabolic profiles in patients with encephalopathy and TPWs between responders and non-responders to anticonvulsants suggest that predicting responders a priori is difficult. The high responder rate suggests that empiric trials of anticonvulsants indeed provide useful clinical information. The more than twofold higher response rate to NSAEDs suggests that this strategy may be preferable to BZDs. Further prospective investigation is warranted.

Keywords: Triphasic waves, Non-convulsive status epilepticus, Encephalopathy, Generalized periodic discharges

Introduction

Background

A common finding in hospitalized patients undergoing continuous electroencephalography (cEEG) monitoring is the presence of generalized periodic discharges with triphasic morphology, traditionally referred to as ‘triphasic waves’ (TPWs) [1–3]. TPWs are bilaterally synchronous, repetitive discharges with typically described features including a negative–positive–negative phase polarity, with the positive phase being the most prominent, frontal-predominance, and frequency of 1.5–2.5 Hz. TPWs were initially described in hepatic coma [4], and in the past, were not thought to be associated with seizures, but rather indicative of toxic/metabolic encephalopathy (TME). While TME is still generally held to be the primary condition in which they occur, they have also been observed in other settings including post-ictally in epilepsy patients [5], in Alzheimer’s disease [6], in cases of encephalopathy caused by metrizamide [7], cefepime [8], lithium [9], baclofen [10], autoimmune thyroiditis, Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease [11], and cerebral tumors involving diencephalic midline structures [12].

With more widespread utilization of continuous EEG (cEEG) monitoring to evaluate for epileptiform patterns in patients with unexplained encephalopathy, TPW patterns have been reported in association with non-convulsive seizures and non-convulsive status epilepticus [8]. Consequently, a persistent diagnostic challenge in continuous EEG monitoring is differentiating between generalized periodic patterns that represent seizures (“ictal”) versus those that likely do not (“non-ictal”). This difficulty is reflected in the new American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) nomenclature which designates TPWs as “Generalized Periodic Discharges (GPDs) with triphasic morphology” [13], in an attempt to avoid the implied “non-ictal” connotation conventionally associated with the term TPWs. Strategies to differentiate these patterns have included identification of morphological differences and response to stimulation [14, 15] but these have not been sufficiently robust. A trial of benzodiazepines may be recommended to differentiate between “ictal” versus “non-ictal” cEEG patterns. However, benzodiazepines often suppress the TPW patterns without any obvious clinical change [16], and therefore a benzodiazepine (BZD) trial is only considered diagnostic if there is a clinical improvement or emergence of normal background EEG patterns. As an alternative, a brief trial of a non-sedating antiepileptic drug (NSAED) may be similarly used [17]. However, though such trials are commonly used in practice, information about their diagnostic yield is lacking.

We set out to clarify the diagnostic utility of empiric trials to discriminate between patients with TPWs that might benefit in terms of clinical outcome from administration of anticonvulsants versus those that might not. To this end, we performed a retrospective review of patients with unexplained encephalopathy and TPWs who had received a trial of BZD ± NSAED and assessed responder rates and compared metabolic profiles of responders and non-responders.

Methods

This study utilized retrospective chart review to identify patients with unexplained encephalopathy who received continuous EEG (cEEG) monitoring, while hospitalized at one of three institutions (Massachusetts General Hospital, Yale, and Columbia), all members of the Critical Care EEG Monitoring Research Consortium (CCEMRC).

Patients were included if they had TPWs on cEEG, and an unexplained encephalopathy at the time that the treating team performed a trial of benzodiazepine and/or NSAED to clarify the ictal versus non-ictal nature of the EEG pattern. Patients were excluded if they had GPDs in the setting of post-anoxic coma, or if they had definite status epilepticus based on clinical seizures or EEG criteria (i.e., repetitive 3 Hz generalized discharges or unequivocal evolution in frequency or morphology) [18].

A positive response to trial of benzodiazepine was defined as (1) resolution of the EEG pattern and (2) either unequivocal improvement in encephalopathy OR appearance of previously absent normal EEG patterns (e.g., posterior dominant rhythm) [17]. The result was deemed inconclusive if the EEG pattern improved but did not normalize, and the patient’s encephalopathy did not improve as determined by the clinical team treating the patient. To investigate whether there was a dose–response relationship for benzodiazepines, we converted all midazolam doses to lorazepam equivalents, using 1 mg midazolam = 0.5 mg lorazepam and performed a two-sided t test allowing for unequal variances to compare the mean lorazepam dose equivalent in the responder versus non-responder groups.

Clinical practice at all contributing institutions was that, if a BZD trial was performed, it was performed before trying an NSAED. In some cases, an NSAED trial was performed after a BZD trial. In other cases, an NSAED trial was performed directly, in which case no BZD trial was attempted. For our study, if a patient had a documented positive response to a BZD trial and then proceeded to anticonvulsant therapy, they were considered to be responders on the basis of their BZD response and they were not included among the antiepileptic drug (AED) responder group. In patients who did not receive a trial of benzodiazepine or the result was inconclusive and they then received a trial of an anticonvulsant medication, these trials were scored in an identical manner to the BZD trials in terms of resolution of the EEG pattern and improvement in encephalopathy. The clinical response was determined by the primary clinical team.

Furthermore, we categorized responses into one of four categories

immediate response (which we considered to be a response in less than 2 h after the trial),

delayed (>2 h after trial initiation) but unequivocal response,

delayed, (>2 h after trial initiation) “equivocal” response, in which where improvement could be potentially attributed to some cause other than the NSAED trial, or

no response.

As this was a retrospective study, clinical assessments were performed by the primary clinical neurology team and documented in daily clinical notes, per routine care. In most cases, it was straightforward to extract via chart review whether or not the neurology team considered a BZD or NSAED trial to have a positive outcome, and to broadly categorize the degree of certainty over time according to the scheme above. In cases where there was no documented medical opinion that a BZD or NSAED trial had provided a benefit, we categorized the case as (4), “no response.”

Laboratory test values including white blood cell count, sodium, potassium, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, albumin, alanine aminotransferase (SGPT), aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT), alkaline phosphatase, ammonia, calcium, glucose, osmolalities, and carbon dioxide were captured for all of the patients, in order to assess possible metabolic derangements. The lab values collected were the highest and lowest values recorded within 48 h of the detection of triphasic waves. The means of the high and low lab values were compared across the different responder groups using a Student’s t test.

Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were 64 patients total in the study group. The average age was 65.8, and the age range was from 16 to 94 years. 60 % of the patients were female. The majority of admission diagnoses were categorized as metabolic derangements (51.6 %) and non-CNS infections (37.5 %). Diagnoses associated with structural brain pathology (e.g. ischemic stroke, brain tumors, etc.) made up a significant minority of cases.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Total number of patients in cohort | 64 |

| Age: average (range) | 65.8 (16–94) |

| % females, % males | 60, 40 |

| Primary admission problem(s) (%) | |

| Metabolic derangement | 51.6 |

| Infection (non-CNS) | 37.5 |

| Ischemic stroke | 10.9 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 6.3 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4.7 |

| Neurosurgery | 3.1 |

| Other | 3.1 |

| Brain tumor | 1.6 |

| Subdural hematoma | 1.6 |

| Metabolic derangement & infection | 17.2 |

| Stroke & infection | 6.3 |

Patient characteristics (age, sex, pathology, lab values - median (std), %)

Summary statistics regarding trials of BZDs are given in Table 2. 83 % of patients (53/64) received a trial of a BZD. Of these patients, 83 % (44/53) received Lorazepam, and 17 % (9/53) received Midazolam. The average dose of Lorazepam was 2.5 mg and the range was 0.5–6 mg. The average dose of Midazolam was 4.1 mg, and the range was 0.5–10 mg. Of all patients who received a BZD trial, 18.9 % (10/53) showed immediate improvement. Nine of these patients were treated with Lorazepam, while only one was treated with Midazolam. The mean difference between the doses of BZDs in the group of responders versus non-responders was small (2.17 vs. 2.7 lorazepam equivalents, respectively), and did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.30).

Table 2.

Benzodiazepine trials

| Patients with benzodiazepine trial | 82.8 % (53/64) |

| Benzodiazepines used in trials | % (N) |

| Lorazepam | 83.0 (44) |

| Midazolam | 17.0 (9) |

| Benzodiazepines doses | Mean ± std (range) |

| Lorazepam average dose (mg) | 2.5 ± 1.9 (0.5–6) |

| Midazolam average dose (mg) | 4.1 ± 2.6 (0.5–10) |

| Benzodiazepine responses | % (N) |

| Positive responses (overall): immediate clinical improvement | 18.9 (10) |

| Lorazepam | 17.0 (9) |

| Midazolam responders | 1.9 (1) |

Summary statistics regarding trials of NSAEDs are given in Table 3. 70 % (45/64) of patients received a trial of an NSAED. Of these, 69 % (31/45) received levetiracetam, 44 % (20/45) received phenytoin, 4 % (2/45) received valproic acid, and 7 % (3/45) patients received lacosamide. Within the group of patients who received an NSAED trial, 7 % (3/45) were immediate responders and 20.0 % (9/45) showed delayed improvement. A further 15.6 % (7/45) were possible responders who exhibited a delayed positive response that could have been due to the AED trial, but was considered to have a possible alternative cause. 44 % (20/45) showed no response, and 13 % (6/45) were in the BZD responder group and to avoid duplication were not included in the NSAED responder group. Therefore, of the total cohort, 34.4 % (22/64) showed a definite improvement in response to BZD or NSAED trial, with a further 10.9 % (7/64) showing a possible response, although an alternative explanation such as correction of metabolic derangement was also possible.

Table 3.

Antiepileptic drug trials

| Patients with AED trial | 70.3 % (45/64) |

| AEDs used | % (N) |

| LEV | 68.9 (31) |

| PHT | 44.4 (20) |

| VPA | 4.4 (2) |

| LCM | 6.7 (3) |

| Duration of AED trial (days) (%) | |

| 0 | 11.1 (5) |

| 1 | 31.1 (14) |

| 2 | 8.9 (4) |

| 3 | 13.3 (6) |

| >3 | 35.6 (16) |

| Total | 100 (45) |

| Response to AED trial (%) | |

| Immediate (<2 h) | 6.7 (3) |

| Delayed improvement (>2 h) clearly attributable to AED | 20.0 (9) |

| Delayed improvement (>2 h), possibly attributable to AED | 15.6 (7) |

| Inconclusive (no definite clinical improvement) | 57.8 (26) |

| Total responders | 42.2 (19) |

We further tabulated the length of NSAED trials as <1 day (5 patients), 1 day (14 patients), 2 days (4 patients), 3 days (6 patients), and >3 days (16 patients). Of the 16 patients with trials lasting >3 days, responses for 10 were inconclusive or no response, 4 were delayed “equivocal” (2 at 3.5 days, 1 at 4 days, 1 at 5 days) and 2 were considered delayed but definite (1 at 5 days and 1 at 10 days).

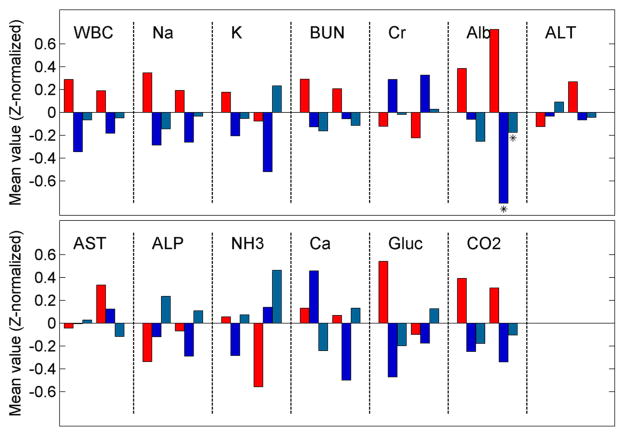

Figure 1 shows the results of comparisons between the metabolic profiles of patients with TPWs who did and did not exhibit an apparent clinical response to anticonvulsant drug trials. The only statistically significant difference found in the lab values between the groups of patients was that the 48-h low value of albumin in the BZD responder group was lower than in the non-responder group.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of metabolic profiles for responders and non-responders. Laboratory values (population means, z-normalized for ease of comparison) for patients with TPWs who did not respond to either a benzodiazepine (BZD) trial of non-sedating-AED (NSAED) trial (red) versus patients with TPWs who responded to either BZD (dark blue) versus patients who did not respond to a BZD trial but did respond to an NSAED trial (light blue). The two groups of bars in the box for each laboratory test represent the 48-h high (first group of 3 bars) and 48-h low (second group of 3 bars). Values for groups of responders whose difference from the corresponding non-responder group to a statistically significant degree, defined as a p value <0.05 on a 2-value t test, are marked with an asterisk. The only statistically significant differences found were for the 48-h low value of albumin in the BZD and NSAED responder groups were lower than in the non-responder group. Overall, these results suggest that the metabolic profiles of patients with TPWs who undergo empiric BZD or NSAED trials are similar among responders and non-responders (Color figure online)

One patient had an adverse event related to an NSAED trial. A trial of fosphenytoin was administered as a loading dose, and the patient became bradycardic with subsequent PEA arrest. He was rapidly resuscitated, a temporary pacer wire was placed, and he was admitted to the cardiac ICU. A PPM was not placed as it was thought that bradycardia was pharmacologically induced and his native rhythm returned. Mental status steadily improved over the course of several days, recovering to better than observed prior to the arrest. There were no adverse events attributable to BZD trials.

Discussion

Despite advancements in management and continuous EEG (cEEG) monitoring, differentiating between ictal versus non-ictal causes of GPDs continues to be a difficult problem [19]. Conventional wisdom holds that when GPDs have certain features considered to be characteristic of TPWs, specifically an antero-posterior phase lag on referential montage, and phase 2 amplitude predominance, it may be concluded that the pattern is not associated with seizures, and that treatment with anticonvulsants is unnecessary. However, other authors have suggested that TPWs seen in TME are often indistinguishable from GPDs associated with seizures or non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), and that conditions conventionally regarded as part of the TME spectrum (e.g., sepsis, renal failure, hepatic encephalopathy), far from being “protective” against seizures, are associated with rates of non-convulsive seizures and NCSE similar to those found in patients with acute brain injuries.

While a clinical improvement in response to a trial of anticonvulsant medications can be helpful, many physicians anecdotally believe that the yield of such trials is low in the setting of “triphasic wave” EEG patterns. Contrary to conventional wisdom, our results demonstrate a high response rate. In a cohort of patients with similar metabolic profiles and TPWs of uncertain significance, we found 34.4 % were definite responders to a trial of a BZD or non-sedating anticonvulsant drug, with clinically significant improvements in mental status or the appearance of previously absent normal EEG features. Only one patient in our cohort had a significant adverse event related to the trial. As we included only cases where there was equipoise regarding whether the etiology was ictal or metabolic, this indicates that these strategies can be helpful in determining the cause in many cases.

Our findings provide evidence for the “pro” side of an ongoing debate over the utility of empiric BZD trials in possible NCSE. On the “con” side, a retrospective study of advanced directive NCSE patients noted that NCSE patients aggressively treated with BZD prolonged hospital stay with no improved outcome [20]. In addition, a commonly cited drawback is that clinical responses can be difficult to ascertain, especially in elderly patients, due to the sedating effects of BZDs, which can lead to an inconclusive result for the BZD trial. Nevertheless, our patient population showed a high clinical responder rate to BZD or NSAED trials, with no notable BZD complication or extended hospital stay. Other previous findings that support the prognostic value of empiric anticonvulsant trials in this setting have found that EEG response to acute intravenous BZD may predict functional outcome [21]. The high responder rate also suggests that NCSE can often clinically masquerade as a metabolic encephalopathy or that both may co-exist, and may be under-diagnosed in this setting. A number of case reports have documented situations when a patient dramatically responds to BZD regimen only after failure of empiric metabolic treatment, with implications of reduced hospital stay and morbidity had NCSE been treated early [22]. TPW are not pathognomonic, show little correlation with prognosis, and can be non-specific, only appearing in 20 % of TME [23].

The dosage of BZD did not appear to be a significant factor in response rate, but this might be explained in part by the fact that high doses were rarely used. On the other hand, even low doses of BZDs in these patients are often sufficient to produce “equivocal” or non-diagnostic results (EEG improvement while the patient falls asleep), hence higher doses might not yield higher response rates.

The finding of a twofold higher response rate with NSAED usage indicates that this may be a useful strategy in cases who have failed to respond to BZD or in cases where a trial of BZD is not appropriate (e.g., concerns regarding respiratory status). Clinical improvement following treatment is often delayed when the diagnosis of status epilepticus is clear [24–26]. Consequently, it is not surprising that improvement was gradual in many patients in our TPW cohort among patients who eventually did respond. How many additional patients might have responded given more time is unknown, nor is it clear how to balance the probably modest but non-negligible risks of prolonged empiric AED trials in patients who do not initially respond [24–26].

In cases where both BZD and NSAED were administered, standard practice was to try a BZD first, then in case of an ambiguous result to try an NSAED. In most cases, times to improvement with NSAED were not immediate, and were longer than the typical half-life of the BZD. However, given the altered pharmacokinetics in many critically ill patients, it is possible that some cases of delayed improvement after BZD plus NSAED were due to an additive or synergistic effect. Conversely, the sedating effects of BZDs could obscure a beneficial effect of a subsequent NSAED trial by sedating the patient, leading to it being classified as a “delayed” response after the BZD effect subsided. Determining the optimal parameters for empiric trials in this setting, including matters relating to dosing and comparisons of BZD versus NSAED, is an important topic for future larger prospective studies.

In our series, patients often had a more prolonged trial of NSAED due to some perceived positive benefit by treating clinical teams. However, any future prospective study should probably follow strictly defined preset protocols with pre-defined time cutoffs. The relatively large number of patients with an inconclusive or equivocal result at the upper limits of trial duration in our series suggests that such future protocols may reasonably set a limitation on the number of days of an AED trial to a few days at most.

Perhaps surprisingly, our responder and non-responder cohorts exhibited no substantial clinically significant differences in metabolic traits. The only statistical exceptions were that patients with albumin levels tended to be higher in the BZD and NSAED responder groups, but this difference seems unlikely to be clinically important. The overall lack of substantial metabolic differences between responders versus non-responders makes predictions difficult, and further supports the practicality of BZD or NSAED trials in the setting of encephalopathy with TPW EEG patterns.

In interpreting our results, it is important to bear in mind that lack or improvement, or slow/delayed improvement of the mental state (and of the EEG) can be seen in both non-convulsive status epilepticus and in metabolic encephalopathies, and that non-convulsive status epilepticus and metabolic encephalopathies may co-exist. Consequently, in this study we have tried to avoid the philosophical and semantical conundrum of which patterns of generalized periodic discharge patterns a priori signify or originate from TME versus NCSE. Rather, we analyzed only responsiveness to BZD or NSAED. The relatively high rates of apparently “positive” responses in these cases of encephalopathy with TPWs suggest that the concept of “AED responsiveness” may be more useful than the conventional TME versus NCSE dichotomy.

Limitations to this study include the retrospective nature which introduces selection bias, subjectivity in clinical response adjudication by the primary clinical team and suboptimal control over other parameters in patients’ clinical care that may have concurrently affected their clinical and electrographic course. Although we attempted to classify improvement of encephalopathy in terms of gradation of certainty (delayed unequivocal vs. “equivocal”), a prospective study with a rigorous, standardized assessment, and pre-defined standards for improvement would be optimal, and should be done in future studies. Other possible limiting factors are the variability among physicians in EEG interpretation and the lack of a mandatory systematic approach to empiric drug trials.

The optimal role for BZDs and/or NSAED is yet to be determined. Determining the true diagnostic yield and potential clinical benefit of anticonvulsant trials in this setting will only be possible via further investigation with a larger, prospective randomized controlled study. Detailed analysis of electroencephalographic features of generalized periodic discharges, and correlation with clinical and imaging findings, may help determine which patients are likely to respond to and benefit from anticonvulsants. Ultimately, our work suggests possible benefit of systematic AED trials in patients with encephalopathy and “triphasic wave” EEG patterns.

Footnotes

Disclosures DOR, PMC, AM, LM, and BF report no relevant disclosures. NG received research support from the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research. MBW received research support from the National Institute of Health (NIH-NINDS, 1K23NS090900-01), the Phyllis & Jerome Lyle Rappaport Foundation, and the Andrew David Heitman Neuroendovascular Research Fund.

Contributor Information

Deirdre O’Rourke, Email: daorourke@mgh.harvard.edu.

Patrick M. Chen, Email: patrick.m.chen.DM@dartmouth.edu.

Nicolas Gaspard, Email: nicolas.gaspard@erasme.ulb.ac.be.

Brandon Foreman, Email: brandon.foreman@uc.edu.

Lauren McClain, Email: LMCCLAIN@mgh.harvard.edu.

Ioannis Karakis, Email: ioannis.karakis@emory.edu.

M. Brandon Westover, Email: mwestover@mgh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Bahamon-Dussan JE, Celesia GG, Grigg-Damberger MM. Prognostic significance of EEG triphasic waves in patients with altered state of consciousness. J Clin Neurophysiol Off Publ Am Electroencephalogr Soc. 1989;6:313–9. doi: 10.1097/00004691-198910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eidelman LA, Putterman D, Putterman C, Sprung CL. The spectrum of septic encephalopathy. Definitions, etiologies, and mortalities. JAMA. 1996;275:470–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickford RG, Butt HR. Hepatic coma: the electroencephalographic pattern. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:790–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI103134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogunyemi A. Triphasic waves during post-ictal stupor. Can J Neurol Sci. 1996;23:208–12. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100038531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primavera A, Traverso F. Triphasic waves in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Belg. 1990;90:274–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niimi Y, Hiratsuka H, Tomita H, Inaba Y, Moriiwa M, Kato M, et al. A case of metrizamide encephalopathy with triphasic waves on EEG. Nō Shinkei Brain Nerve. 1984;36:1167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Rodríguez JE, Barriga FJ, Santamaria J, Iranzo A, Pareja JA, Revilla M, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus associated with cephalosporins in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2001;111:115–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan PW, Birbeck G. Lithium-induced confusional states: nonconvulsive status epilepticus or triphasic encephalopathy? Epilepsia. 2006;47:2071–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hormes JT, Benarroch EE, Rodriguez M, Klass DW. Periodic sharp waves in baclofen-induced encephalopathy. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:814–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310132033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieser HG, Schindler K, Zumsteg D. EEG in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:935–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguglia U, Gambardella A, Oliveri RL, Lavano A, Camerlingo R, Quattrone A. Triphasic waves and cerebral tumors. Eur Neurol. 1990;30:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000116614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch LJ, LaRoche SM, Gaspard N, Gerard E, Svoronos A, Herman ST, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol Off Publ Am Electroencephalogr Soc. 2013;30:1–27. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182784729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaya D, Bingol CA. Significance of atypical triphasic waves for diagnosing nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav EB. 2007;11:567–77. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulanger J-M, Deacon C, Lécuyer D, Gosselin S, Reiher J. Triphasic waves versus nonconvulsive status epilepticus: EEG distinction. Can J Neurol Sci J Can Sci Neurol. 2006;33:175–80. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fountain NB, Waldman WA. Effects of benzodiazepines on triphasic waves: implications for nonconvulsive status epilepticus. J Clin Neurophysiol Off Publ Am Electroencephalogr Soc. 2001;18:345–52. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jirsch J, Hirsch LJ. Nonconvulsive seizures: developing a rational approach to the diagnosis and management in the critically ill population. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1660–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.11.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong DJ, Hirsch LJ. Which EEG patterns warrant treatment in the critically ill? Reviewing the evidence for treatment of periodic epileptiform discharges and related patterns. J Clin Neurophysiol Off Publ Am Electroencephalogr Soc. 2005;22:79–91. doi: 10.1097/01.wnp.0000158699.78529.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutter R, Kaplan PW. Electroencephalographic criteria for non-convulsive status epilepticus: synopsis and comprehensive survey: EEG criteria for NCSE. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claassen J, How I. Treat patients with EEG patterns on the ictal-interictal continuum in the neuro ICU. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:437–44. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litt B, Wityk RJ, Hertz SH, Mullen PD, Weiss H, Ryan DD, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the critically ill elderly. Epilepsia. 1998;39:1194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutter R, Stevens RD, Kaplan PW. Significance of triphasic waves in patients with acute encephalopathy: a nine-year cohort study. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124(10):1952–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holtkamp M, Meierkord H. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in the intensive care setting. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:169–81. doi: 10.1177/1756285611403826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagan KJ, Lee SI. Prolonged confusion following convulsions due to generalized nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Neurology. 1990;40:1689–94. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.11.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan PW. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the emergency room. Epilepsia. 1996;37:643–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drislane FW. Presentation, evaluation, and treatment of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav EB. 2000;1:301–14. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]