Abstract

Accurate protein phosphorylation analysis reveals dynamic cellular signaling events not evident from protein expression levels. The most dominant biochemical assay, western blotting, suffers from the inadequate availability and poor quality of phospho-specific antibodies for phosphorylated proteins. Furthermore, multiplexed assays based on antibodies are limited by steric interference between the antibodies. Here we introduce a multifunctionalized nanopolymer for the universal detection of phosphoproteins that, in combination with regular antibodies, allows multiplexed imaging and accurate determination of protein phosphorylation on membranes.

Keywords: antibodies, dendrimers, membranes, multiplexed analysis, phosphoproteins

Graphical abstract

Playing nicely together: Nanosized pIMAGO-Fluor binds to a target with a total protein antibody without steric hindrance. Multiplexed detection of phosphorylation and total protein levels can provide critical information about the true relative level of phosphorylation on membranes in western blotting or microarrays.

Protein phosphorylation is a major molecular mechanism for dynamically regulating cellular protein functions, and abnormalities lead to the onset and progression of numerous diseases.[1] Western blotting is the most common approach to detecting on-membrane phosphorylation in biological laboratories; however, the technique is severely limited by the availability and quality of phospho-specific antibodies, which constrain analyses to well-characterized phosphorylation events. An effective antibody has to be made for every single phosphorylation site on individual proteins; this is the bottleneck in many discovery efforts.[2] Researchers working on model organisms, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Drosophila melanogaster, and Arabidopsis thaliana, do not have access to commercial phospho-specific antibodies and have to use 32P radioactive labeling[3] or suboptimal staining reagents with lower selectivity and sensitivity, such as Pro-Q Diamond[4] and Phos-tag.[5]

We have previously introduced strategies based on multifunctionalized nanopolymers for phosphorylation analyses with high specificity.[6] The water-soluble nanopolymer is functionalized with titanium ions, thereby enabling strong and specific binding to phosphoproteins, and with “handle groups” for enrichment before MS analyses[6b, 7] or for detection.[6a, c, d] Multiple titanium ions and handle groups on each nanopolymer improve binding efficacy and enhance the signal, thus allowing efficient isolation or detection of phosphoproteins in low abundance.

In this report, we describe the design and development of a nanopolymer with fluorescence tags (pIMAGO-Fluor) to enable the direct detection of phosphoproteins on membranes. The unique features of the pIMAGO-Fluor design make it amenable to multiplexed assays. With the nano size of the reagent, it can be coupled to general antibodies for the simultaneous imaging and measurement of phosphorylation and total protein amounts with little steric hindrance.[6c] We demonstrate its applications through standard protein mixtures, in vitro kinase assays, and in situ phosphorylation of yeast Rad9 and Rad17 proteins after cell treatment with a DNA damage agent.

The synthesis and characterization of pIMAGO-Fluor are similar to procedures previously developed by our group.[6a, c, d] Briefly, some of the amines in the generation 4 polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer are functionalized with NHS-linked IRDye 680 fluorescent molecules, then phosphonic acid groups are covalently linked to the remaining free amines on the dendrimer through a carbodiimide-catalyzed reaction. The excess chemicals are removed by dialysis, and the resulting pIMAGO reagent is functionalized with TiIV ions. Multiple fluorescent groups per pIMAGO molecule lead to significant signal amplification, and the near-infrared fluorescent tags used here allow a further improvement in sensitivity and wider linear detection with minimum autofluorescence and bleaching issues.[8] A flowchart for detecting phosphoproteins by using pIMAGO-Fluor is shown in Figure 1A. Proteins are separated by using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a membrane, then the membrane is blocked (∼10 min) and incubated with pIMAGO-Fluor (∼1 h). For multiplexed assays, the membrane can be further incubated with a regular antibody that recognizes the protein (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1.

A) Simplified procedure schematic for pIMAGO-Fluor-based detection of phosphoproteins by western blot. B) Multiplexing proposal of pIMAGO-Fluor with an antibody, demonstrating apparent size difference between pIMAGO and an antibody.

To examine the specificity, sensitivity, and quantitative capabilities of pIMAGO-Fluor, we used a six-protein mixture separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a membrane. The mixture contained four non-phosphoproteins (bovine serum albumin, catalase, α-lactalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin) and two phosphorylated proteins (ovalbumin and β-casein). All were serially diluted, loaded at different amounts and had molecular weights discernible by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Figure 2A, pIMAGO-Fluor only detected the phosphorylated proteins and had an apparent specificity of >99%. The specificity was calculated by comparing the relative signal from phospho- and non-phosphoproteins (i.e., 4 ng of a phosphoprotein resulted in stronger signal than 400 ng of a non-phosphoprotein). The signal from β-casein being significantly stronger than that from ovalbumin was likely caused by the former having more reported phosphorylation sites (five compared to ovalbumin's one or two); a result that is not always delivered by phosphoprotein stains.[9] Moreover, β-casein was detected at the sub-nanogram level, thus demonstrating adequate sensitivity for most biological experiments. Finally, a quantitative curve for β-casein mean intensities was extracted from this analysis (Figure 2B); this showed an outstanding linearity of the approach (R2 = 0.992) and a sub-nanogram limit of quantitation (LOQ). For comparison, we carried out the same experiment using Pro-Q Diamond (ThermoFisher) staining for general phosphoprotein detection (Figure S1A in the Supporting Information). The results demonstrated comparatively lower sensitivity and specificity, with a relatively strong signal from non-phosphoproteins.

Figure 2.

A) pIMAGO-Fluor based detection of six-protein mixture separated by SDS-PAGE in amounts ranging from 400 to 0.39 ng for each protein. The two phosphorylated proteins are denoted by “P”. B) Graphic representation of detection linearity and quantitation for β-casein in (A).

One potential major application of pIMAGO-Fluor is detecting changes in phosphorylation during in vitro kinase or phosphatase assays. The assays are carried out routinely in biology labs and provide important information about the kinase–substrate or phosphatase–substrate relationship. Typically, the assay requires either prior knowledge of the phosphorylation sites in the case of antibody-based detection, the use of artificial substrates, which frequently introduces misleading information, or the handling of hazardous radioactive materials (e.g., 32P labeling). In the in vitro kinase assays detected by pIMAGO-Fluor, two pairs of important kinases and their known substrates were employed; Cdk1 and its substrate retinoblastoma (Rb; Figure 3A, B), and JNK1 and its substrate cJun (Figure 3C, D). pIMAGO-Fluor analysis showed a strong increase in the phosphorylation signal after the addition of ATP (Figure 3A, C; left); results that mirror those of the phospho-site-specific antibodies developed for these substrates (Figure 3B, D; left).

Figure 3.

Multiplexed detection of Cdk1 + Rb (A and B) and JNK1 + cJun (C and D) in in vitro kinase assays. The assay mixtures (with and without ATP) were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected in the 700 channel (red) by using pIMAGO-Fluor (A and C) or phospho-site-specific antibodies (B and D). Each membrane was also subsequently incubated with general anti-Rb or anti-cJun antibodies and detected in the 800 channel (green), and the signals were overlaid (yellow).

However, the ability to accurately quantify changes in protein phosphorylation does not depend only on the detection of phosphorylation itself, but rather on its measurement normalized against total protein amount. Each differential phosphorylation event detected can integrate changes in both protein expression and phosphorylation. This is particularly true when considering that 25% or more of what appears to be differentially phosphorylated human proteins can be actually attributed to changes in total protein amounts.[10] Therefore, phosphorylation stoichiometry often needs to be determined for true signaling profiling. Current strategies typically require two or more different antibodies in order to probe the whole protein and its phosphorylation status separately on the membrane. The first antibody needs to be stripped off before the second antibody is applied, and this procedure can potentially lead to a loss of antigen, resulting in inaccurate results. It is highly desirable to have a strategy to measure protein amount and phosphorylation on a membrane simultaneously.

The presented pIMAGO-Fluor reagents were prepared from polyamidoamine dendrimer generation 4 (PAMAM G4), which is approximately 14 kDa in size—drastically smaller than an antibody.[11] The competition for the same target protein is minimal due to greatly reduced steric hindrance (Figure 1B). The multiplexing assay based on pIMAGO-Fluor would allow simultaneous detection of total protein phosphorylation and protein amount (by using antibody) on the same blot. After incubation with pIMAGO-Fluor or the phospho-antibody, the membranes were treated with general protein antibodies (anti-Rb and anti-cJun; Figure 3; center). Because IRDye 680 was used in the first step, and IRDye 800 in the second, both signals were analyzed simultaneously by using a dual-channel imaging scanner (Figure 3; right). The results further demonstrate the effectiveness of pIMAGO-Fluor detection as an alternative route to expensive or unavailable phospho-antibodies. On the other hand, Pro-Q Diamond does not have the capability for such multiplexed detection with antibodies, as it cannot survive washes with TBST/PBST, a standard loading and washing buffer for antibodies (Figure S1 B).

Although the multiplexed results for pIMAGO-Fluor and phospho-antibodies in Figure 3 resulted in similar signals, this is not always the case. On some occasions, due to large size, the first bound antibody might hinder the binding of the second one, especially if the affinity sites are close. Without preliminary testing, it is difficult to predict which antibody pairs would present this issue. We report here an example of this phenomenon—a multiplexed detection of Syk-induced Cdb3 phosphorylation by using phospho-tyrosine and general anti-Cdb3 antibodies. Seven separate experiments were carried out, and a representative blot is shown in Figure 4A. The anti-Cdb3 signal artificially decreased by approximately 30% on average (quantitation is shown in Figure 4D), when compared to control (anti-Cdb3 detection only; Figure 4C). However, when pIMAGO-Fluor was used in multiplexed fashion with anti-Cdb3 detection, no decrease in anti-Cdb3 signal was observed (Figure 4B; quantitation in Figure 4D). The experiment clearly indicated that the pIMAGO-Fluor molecule facilitated more accurate simultaneous detection of total protein phosphorylation and protein amount.

Figure 4.

Multiplexed detection of Syk+Cdb3 in an vitro kinase assay. The assay mixtures (with and without ATP) were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected in the 700 channel (red) by using A) anti-pTyr antibody or B) pIMAGO-Fluor. Each membrane was also subsequently incubated with general anti-Cdb3 antibody and detected in the 800 channel (green), and the signals were overlaid (yellow). Numbers above the signal bands show the ratio differences compared to the control in (C). C) As a control for signal normalization, the kinase assay was also detected by anti-Cdb3 antibody alone. D) Quantitative representation of the ratio differences between pIMAGO-Fluor and anti-pTyr effects on subsequent anti-Cdb3 signal. The averages and error bars of standard deviations are based on seven different experiments (ns = differences were not statistically significant, *= differences were statistically significant at t-test p < 0.05).

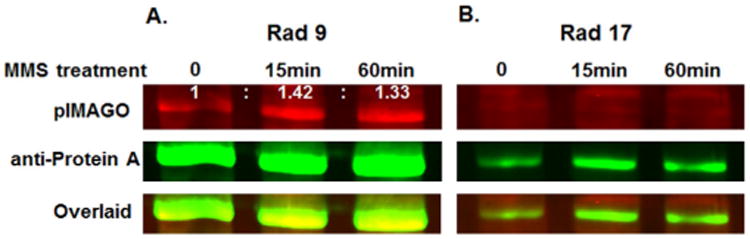

Besides multiplexed detection of in vitro phosphorylation assays, we demonstrate the ability of pIMAGO-Fluor to detect endogenous phosphorylation in budding yeast. Profiling of signaling networks in model organisms such as plants and yeast has been greatly limited by the lack of phospho-specific antibodies. In this study, we took advantage of a S. cerevisiae open reading frame (ORF) fusion library, in which each strain expresses a separate epitope-tagged gene from its natural chromosomal locus.[12] Strains expressing protein A-tagged Rad9 and Rad17 were selected from this library. Both Rad9 and Rad17, together with many other proteins, are an essential part of the checkpoint mechanism required for the proper detection and repair of DNA damage.[13] Failure to mitigate the damage from genotoxic stress signals can result in genome instability and contribute to disease, including cancer. Both Rad9 and Rad17 are phosphoproteins.[14] However, only Rad9 is thought to be hyperphosphorylated specifically in response to DNA damage checkpoint activation, such as occurs after treatment with methyl methanesulfonate (MMS).[14a] Analysis of such differential regulation of related proteins in the same complex can provide very important information about the detailed mechanisms within network signaling. To test our detection method, we treated cultures of the yeast strains expressing tagged Rad9 and Rad17 proteins with 0.01% MMS. Cells were harvested before, and 20 and 60 min post-treatment. Rad9 and Rad17 proteins were affinity purified from whole-cell extracts on IgG beads, and the resulting samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a membrane. Finally, the phosphorylation signal and total protein signal were detected simultaneously by using pIMAGO-Fluor (700 channel) and anti-protein A antibody (800 channel; Figure 5). Relative quantitation of the signal difference demonstrated an approximately 40% increase in Rad9 phosphorylation in MMS-treated samples after normalization with total protein signal (Figure 5 A). This is consistent with existing evidence that Rad9 is phosphorylated during the cell cycle even in the absence of DNA damage and undergoes further phosphorylation when the DNA damage checkpoint pathway is activated.[15] There were no obvious phosphoprotein bands or detectable phosphorylation increase in Rad17 samples following MMS treatment (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Multiplexed detection of protein A-tagged Rad9 (A) and Rad17 (B) affinity purified samples before and after treatment with DNA damage agent MMS. pIMAGO-Fluor was used to detect phosphorylation (red) and antiprotein A antibody for total protein amount (green). Numbers above the signal bands show the ratio differences compared to the untreated control after normalization with protein.

These data correlate well with previously published results,[14a] thus validating the use of pIMAGO-Fluor for one-step detection of in situ protein phosphorylation. Although pIMAGO-Fluor is limited in that it cannot pinpoint the exact sites of phosphorylation, we believe that it still offers a highly useful phosphorylation screening tool for projects for which antibodies are not available or their use is not desired.

In summary, we have introduced a strategy for the multiplexed imaging and measurement of protein phosphorylation based on a soluble dendrimer functionalized with near-IR fluorophores for one-step universal detection of protein phosphorylation in western blot format. Major applications for the new method include quantitative phosphorylation measurement, in vitro kinase assays, kinase and phosphatase activity profiling, kinase/phosphatase inhibitors screening, and detection of endogenous phosphorylation. The nanosize of pIMAGO-Fluor offers a unique ability to couple with a general antibody for the simultaneous determination of total protein and phosphoprotein amounts. The technology would be particularly useful in model organisms that typically do not have available phospho-specific antibodies. With high versatility, selectivity, and comparable sensitivity to antibody-based phospho-assays, pIMAGO-Fluor shows great potential to provide researchers with a novel and improved approach for routine phosphorylation assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants 5R01M088317 and 1R43EB015809 as well as NSF grant 1256600. Additional support was provided by the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research (P30 CA023168).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201600068.

References

- 1.a) Hunter T. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cohen P. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E127–E130. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Pawson T, Scott JD. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Haab BB, Dunham MJ, Brown PO. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-research0004. RESEARCH0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sevecka M, Wolf-Yadlin A, MacBeath G. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.005363. M110.005363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy GR, Philip R, Tan YH. Electrophoresis. 1994;15:417–440. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150150160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Steinberg TH, Agnew BJ, Gee KR, Leung WY, Goodman T, Schulenberg B, Hendrickson J, Beechem JM, Haugland RP, Patton WF. Proteomics. 2003;3:1128–1144. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Martin K, Steinberg TH, Cooley LA, Gee KR, Beechem JM, Patton WF. Proteomics. 2003;3:1244–1255. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Iliuk A, Martinez JS, Hall MC, Tao WA. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2767–2774. doi: 10.1021/ac2000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Iliuk AB, Martin VA, Alicie BM, Geahlen RL, Tao WA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2162–2172. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pan L, Iliuk A, Yu S, Geahlen RL, Tao WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18201–18204. doi: 10.1021/ja308453m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Iliuk A, Liu XS, Xue L, Liu X, Tao WA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:629–639. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.018010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Iliuk A, Jayasundera K, Wang WH, Schluttenhofer R, Geahlen RL, Tao WA. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2015;377:744–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2014.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jayasundera KB, Iliuk AB, Nguyen A, Higgins R, Geahlen RL, Tao WA. Anal Chem. 2014;86:6363–6371. doi: 10.1021/ac500599r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams KE, Ke S, Kwon S, Liang F, Fan Z, Lu Y, Hirschi K, Mawad ME, Barry MA, Sevick-Muraca EM. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:024017. doi: 10.1117/1.2717137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal GK, Thelen JJ. Proteomics. 2005;5:4684–4688. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Wu R, Dephoure N, Haas W, Huttlin EL, Zhai B, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009654. M111.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tsai CF, Wang YT, Yen HY, Tsou CC, Ku WC, Lin PY, Chen HY, Nesvizhskii AI, Ishihama Y, Chen YJ. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6622. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boas U, Heegaard PM. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:43–63. doi: 10.1039/b309043b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longhese MP, Foiani M, Muzi-Falconi M, Lucchini G, Plevani P. EMBO J. 1998;17:5525–5528. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Emili A. Mol Cell. 1998;2:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Albuquerque CP, Smolka MB, Payne SH, Bafna V, Eng J, Zhou H. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1389–1396. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700468-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chi A, Huttenhower C, Geer LY, Coon JJ, Syka JE, Bai DL, Shabanowitz J, Burke DJ, Troyanskaya OG, Hunt DF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Bonilla CY, Melo JA, Toczyski DP. Mol Cell. 2008;30:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vidanes GM, Sweeney FD, Galicia S, Cheung S, Doyle JP, Durocher D, Toczyski DP. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.