SUMMARY

The biophysics of blood flow can dictate the function of molecules and cells in the vasculature with consequent effects on haemostasis, thrombosis, embolism, and fibrinolysis. Flow and transport dynamics are very distinct for: (1) haemostasis vs. thrombosis and (2) venous vs. arterial episodes. Intraclot transport changes dramatically the moment haemostasis is achieved or the moment a thrombus becomes fully occlusive. With platelet concentrations that are 50–200-fold greater than platelet rich plasma, clots formed under flow have very different composition and structure compared to blood clotted statically in a tube. The platelet-rich, core/shell architecture is a prominent feature of self-limiting hemostatic clots formed under flow. Importantly, a critical threshold concentration of surface tissue factor is required for fibrin generation under flow. Once initiated by wall-derived tissue factor, thrombin generation and its spatial propagation within a clot can be modulated by: γ′-fibrinogen incorporated into fibrin, engageability of FIXa/VIIIa tenase within the clot, platelet-derived polyphosphate, transclot permeation, and reduction of porosity via platelet retraction. Fibrin imparts tremendous strength to a thrombus to resist embolism up to wall shear stresses of 2400 dyne/cm2. Extreme flows, as found in severe vessel stenosis or in mechanical assist devices, can cause von Willebrand Factor self-association into massive fibers along with shear induced platelet activation. Pathological VWF fibers are ADAMTS13-resistant, but are a substrate for fibrin generation due to FXIIa capture. Recently, microfluidic technologies have enhanced the ability to interrogate blood in the context of stenotic flows, acquired von Willebrand’s disease, hemophilia, traumatic bleeding, and drug action.

Keywords: shear stress, haemodynamics, von Willebrand Factor, platelet, thrombin, fibrin

INTRODUCTION

The physical processes of flow and mass transfer impact: the rate of clot growth, clot composition, clot stability, embolic risk, the molecular mechanisms that are operative during various stages of clot growth, the criteria for successful self-limiting haemostasis, the risk of occlusive thrombosis, and the efficacy or risk of pharmacological intervention. Haemodynamics dictates the collision rate of cells with each other and the vessel wall (the key metric being: shear rate) as well as the forces exerted on adhesion receptors, membranes, and clot assemblies (metric: shear stress) [See Supplement for equations and parameters in italics]. Additionally, soluble species undergo diffusive and convective transport (metric: Peclet number) that can influence reaction dynamics during clotting and fibrinolysis (metric: Damkohler number). This article reviews the interconnections of haemodynamics, mass transfer, and biorheology relevant to haemostasis and thrombosis.

Haemodynamics

Physiological flow is laminar with Reynolds numbers (Re) that are well below the threshold for turbulence [1], in contrast to the unique situations of severe stenosis [2], coarctation [3], mechanical heart valves [4], or arteriovenous fistulas [5]. Physical processes often dictate the localization of atheroprone endothelium [6], plaque rupture [7], or vein valve dysfunction [8] that then drive coronary thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis, or thromboembolism. For a given vessel diameter and blood viscosity and pressure drop (ΔP/L), the key prevailing haemodynamic metrics are: velocity profile, flow rate, wall shear rate, and wall shear stress. These variables can be controlled in laboratory experiments. However, in vivo haemodynamics are exceedingly more complex with time-dependent flows, compliant vessels, flow-induced vasodilation, changing microvascular resistance, and complex branching and asymmetric geometries. Many in vivo haemodynamics properties have been characterized at the microscopic and macroscope level (Table 1).

Table 1. Haemodynamic and transport parameters in the human vasculature relevant to thrombosis and haemostasis.

WSR, wall shear rate (s−1); WSS, wall shear stress (dyne/cm2). Non-wall values for shear rate or shear stress indicated as s−1 or dyne/cm2.

| Process | Prevailing biophysics (Comment) | [Ref.] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Physiology | s−1 | dyne/cm2 | |

|

|

|||

| Ascending aorta | 300 WSR | 2–10 WSS | [1] |

| Large arteries | 300–800 WSR | 10–30 WSS | [1] |

| Coronary artery (LCA/RCA) | 300–1500 WSR | 10–60 WSS | [101,102] |

| Carotid artery | 250 WSR | 10 WSS | [1] |

| Arterioles | 500–1600 WSR | 20–60 WSS | [1,103] |

| Capillary | 200–2000 WSR | high WSS* | [1] |

| Post-capillary venules | 50–200 WSR | 1–2 WSS | [104] |

| Veins | 20–200 WSR | 0.8–8 WSS | [103] |

| Low flow and venous haemodynamics | |||

| RBC Rouleaux formation | < 10 s−1 shear rate | [105] | |

| Neutrophil-venule rolling | 100–300 WSR | 1–4 WSS | [104] |

| Hydrodynamic Thresholding | ~100 WSR for platelet (GP1b-A1 VWF) | [37] | |

| Hydrodynamic Thresholding | ~100 WSR for PMNL rolling & strings | [106,107] | |

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | 0 – 200 s−1 shear rate (valve pocket) | [8,108] | |

| ADAMTS13/EC-released ULVWF | 0 WSS; 2.5 WSS | [90,109] | |

| Extreme Haemodynamics | |||

| Aortic coarctation | 140 to > 1000 dyne/cm2 (can be turbulent) | [110], [111] | |

| Coronary Stenosis (LAD) | 5000 – 100,000 WSR (w/recirculation zone) | [112] | |

| Carotid Stenosis | 40–360 WSS | [113] | |

| VWF unfolding in bulk | 3000–5000 s−1, 40–60 dyne/cm2 | [66,67,114] | |

| VWF fiber formation | 104–105 WSR on collagen or micropost | [68,70] | |

| Shear induced platelet activation | >5000 s−1 | [103] | |

| AV-fistula | 100–100 dyne/cm2, turbulent | [5] | |

| Left ventricle assist device (LVAD) | >5,000 to >100,000 s−1 (acquired VWD) | [115,116] | |

| Platelet lysis | > 250 dyne/cm2 | [103] | |

| Hemolysis | >1500 dyne/cm2 (exposure time dependent) | [117] | |

| Clotted blood and thrombus | |||

| Brownian diffusion coefficient, D | D = 5 × 10−7 cm2/s (for 50 kDa protein) | ||

| Thrombus tortuosity | T = 2–2.5 = D/Deff | [18] | |

| Fibrin permeability (3 mg/mL) | 4×10−11 (fine) to 4×10−9 cm2 (coarse) | [19] | |

| Fibrin permeability (156 mg/mL) | 1.5 × 10−12 cm2 | [118] | |

| Thrombus permeability | 2.7×10−14 cm2 | [26] | |

| Fibrin fiber elastic modulus | 14.5 MPa (crosslinked) | [119] | |

| VWF fiber elastic modulus | ~50 MPa | [70] | |

| Fibrin gel elastic modulus | ~10–200 kPa (10–100 mg/mL; low strains) | [120] | |

| Thrombus elastic modulus | 30 – 100 kPa | [121] | |

| Thrombus embolic threshold | >50,000 WSR (~2000 WSR without fibrin) | [22] | |

| Molecular and Cellular Mechanics | |||

| VWF A2 domain unfolding | 7–14 pN (21 pN in A1–A2–A3 context) | [122] | |

| αIIbβ3-fibrinogen bond strength | 5 – 50 pN (10 to 1-sec bond life) | [123] | |

| VWF A1-GPIbα bond strength | ~10–40 pN (<1-sec bond life) | [124] | |

| Force on adherent platelet | Fs (in pN) ≅ 1–5 x (WSS in dyne/cm2) | [38] | |

| Platelet contractile force | 29 nN per platelet | [125] | |

WSS difficult to define in capillaries.

RBC motions in flowing blood greatly enhance the diffusivity of platelets and create a radially-directed transport of platelets toward the wall, often described by a drift velocity [9–11]. The relatively cell free plasma layer (~2–5 μm thick) at the vessel wall or thrombus boundary is enriched ~3 to 5-fold in platelets and depleted of red blood cells. Small molecular weight solutes do not experience enhanced diffusive transport due to RBC motions [12]. Platelet accumulation in the cell free layer is central to clotting since a reduction in hematocrit can greatly reduce the rate and extent that a clot develops under flow [13], a rheological risk of iatrogenic hemodilution during resuscitation therapy for trauma. At a given hematocrit and for vessels greater than ~150 μm in diameter [14], blood viscosity is nearly constant (Newtonian) at shear rates > 100 s−1 that are sufficient to prevent rouleaux.

Porous media transport (intrathrombus)

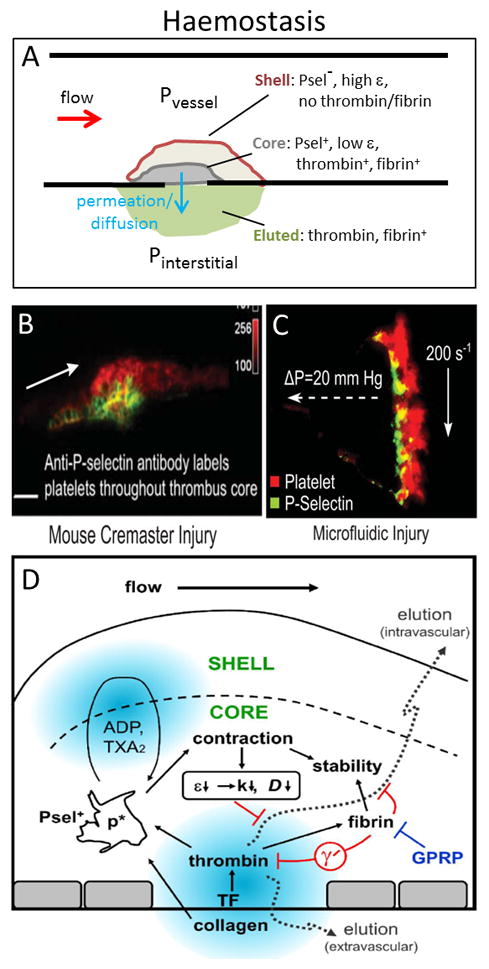

As platelets deposit on a thrombotic surface under flow, the platelet concentration in these dense deposits can become 50 to 200-fold greater than that of platelet rich plasma (~300,000 platelets/μL of PRP) [15,16]. These dense platelet deposits have a porosity of ε = 0.3–0.4 (core) to 0.7 (shell) [15,16] with pores ranging from 10’s of nanometers [17] to several microns [18] in size and potentially containing fibrin (Fig. 1). Darcy’s Law governs fluid permeation (a special type of convection) within a porous clot [19] of permeability k when local pressure gradients (∇P) exist to push a fluid of viscosity μ at a superficial velocity of v̄:

Fig. 1. Physical processes in haemostasis.

The core/shell architecture of hemostatic clots results in a self-limiting event that sustains a transclot pressure drop (ΔP = Pvessel − Pinterstitial) (A). In a mouse arteriole laser injury, the dense core is P-selectin positive and adjacent to the wound site and surrounded by a shell of less tightly bound, P-selectin negative platelets (B). A similar core/shell architecture is seen with human blood perfused over collagen/TF where the labeled P-selectin layer is also rich in thrombin and fibrin (C). The core region is highly contracted, thrombin and fibrin rich, and displays lower protein mobility than the shell, with fibrin playing a role in clot stability and limiting thrombin activity via γ′-fibrinogen (especially at venous shear rates) (D). Panels B, C, D from [30,50] with permission.

In addition to permeation as a transport mechanism, solutes can undergo diffusion. The pore size distribution, pore shape, and porosity are structural attributes of fibrin gels, platelet aggregates, and thrombi that impact the effective diffusion coefficient (Deff) and the dispersion coefficient (DL) (and permeability). Platelet retraction reduces both the porosity of the clot and the pore size with consequent effects on solute transport [20]. Correlations exist to predict the Brownian diffusion Coefficient (D) and Deff of a solute in porous media like clots (see Supplement). The diffusion of solutes is reduced by: (i) binding to cells, (ii) steric hindrance in small gaps, and/or (iii) tortuosity due to impermeable cell membrane barriers. In the dense platelet core of a clot, the exposed platelet surface area can exceed ~100 cm2 per μL-clot. Proteins that bind tightly to platelet membranes or receptors will have little mobility across the clot, as seen for Factor Xa mobility in platelet-fibrin clots [21]. The ratio of convective transport to diffusive transport inside a porous clot is the Peclet number, Pe = (v̄L)/Deff with Pe < 1 being diffusion-dominated transport and Pe > 1 being convection-dominated transport. While pure diffusion alone (v̄ = 0) is efficient in transporting small solutes and proteins over distances of tens of microns, this Brownian motion is extremely inefficient for moving solutes mm to cm distances, requiring hours to many days for a protein to move such a distance. For occlusive thrombi, permeation is the major mode of transport to allow thrombolytic agents to work on a reasonable time scale to treat coronary thrombosis [19], whereas catheter-mediated intrathrombus delivery is often required to overcome transport limits during lytic therapy for deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Constant flowrate vs. constant pressure drop experiments

A clotting episode may begin at a specific wall shear rate and wall shear stress, however the changing geometry of the growing clot causes striking changes in the wall shear stress and shear rate and associated changes in reaction and adhesion dynamics and mechanisms. While in vitro clotting experiments are often conducted at constant flow rate with a syringe pump, this is not physiologic. At constant flow rate in the lab experiment, pump pressure will build unrealistically as a clot becomes occlusive, resulting in a bullet-like embolic event [22]. In contrast, as a vessel becomes blocked in the body, flow is simply diverted to other vessels. To achieve thrombotic occlusion, experiments can be run at constant pressure drop using a set pressure head or flow can be allowed to be diverted as a channel becomes fully thrombosed. For small clots that do not obstruct the flow channel (<50% reduction of lumen), there is little change in pressure drop across the clot (although velocities and wall shear stress increase markedly to drive surface erosion) and thus little buildup of pressure on the upstream face of the clot to drive large scale embolization.

Transport during haemostasis

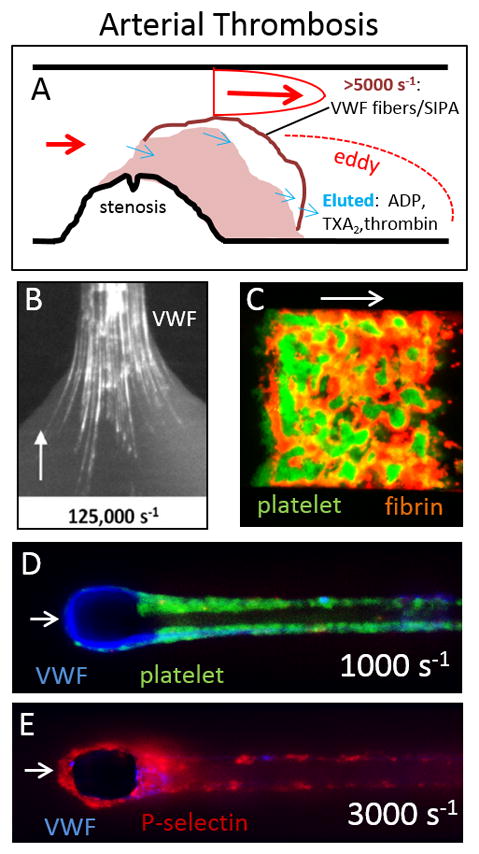

Complete severing of a vessel or puncturing of a vessel sidewall initially creates a dramatic pressure gradient to drive flow out of the pressurized vascular compartment into an interstitial compartment or to the atmosphere (Fig. 1A). The vessel rapidly loses pressure and vasoconstriction helps reduce blood loss. As platelets and coagulation produce a hemostatic plug to stop bleeding, pressure gradients exist across the porous thrombus to drive plasma constituents across the clot to the extravascular compartment. Thrombin and plasma, for example, can elute into the extravascular compartment [20,23] and drive fibrin polymerization to help anchor the hemostatic clot in place. In contrast, when an intravascular thrombosis is formed on a diseased or wounded vessel wall, that vessel wall is essentially impermeable and radially-directed transthrombus permeation is absent (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Physical processes in arterial thrombosis.

A ruptured atherosclerotic plaque triggers thrombosis under conditions of high wall shear stress and wall shear rate as blood jets through the stenosis (A). VWF factor is required for platelet capture under arterial flow conditions and extreme wall shear stresses can drive VWF fiber formation on an exposed collagen surface (B). Perfusion of whole blood over a 250 μm × 250 μm collagen/TF patch results in rapid platelet accumulation in dense clumps (green) that undergo retraction while fibrin (red) polymerizes under, around, and downstream of the platelets. Extreme wall shear rates (10,000 s−1) produce thick VWF fibers (blue) that grow around a 30-μm wide micropost that can subsequently bind platelets perfused at 1000 s−1 (D) that will activate and present P-selectin at 3000 s−1 (E). Panels B, D, E from [68,70] with permission.

Intrathrombus transport during thrombosis

As a thrombus grows intraluminally, blood flow is diverted around and over it. Although the lumen available is reduced and this causes the blood to dramatically accelerate (wall shear stress increases), there is little pressure drop associated with this jetting flow for < 75% net blockage of a vessel lumen (and symptoms of angina are seldom present). The pressure is slightly higher on the front face of the non-occlusive thrombosis relative to the downstream side and some small level of permeation can be expected within the thrombus, especially in the outer regions of the clot [24] (Fig. 2A). Deep within the clot and near the dysfunctional vessel wall, these small pressure gradients are likely minor and little permeation is expected in this most inner region [24]. Intrathrombus permeation velocities are always miniscule compared to the velocity in the flowing blood outside the clot. As a clot grows, numerous soluble constituents such as released ions, ADP, thromboxane, and thrombin will diffuse or permeate (where pressure gradients permit) out of the clot into the blood that is flowing around the clot to form a concentration boundary layer that may be as thick as the cell free layer (a few microns) or slightly greater [25,26]. The thickness of this concentration boundary layer can grow with distance downstream along a clotting surface and distal regions of a clot can display enhanced fibrin deposition [22,27]. Importantly, flow provides tremendous washout of species that enter the boundary layer and maintains a tremendous concentration gradient for diffusive transport [28]. If flow were to suddenly stop or occlusion to occur, such solutes would not be washed away and would increase locally in concentration driving biological events such as when ADP and thromboxane accumulate locally upon flow stoppage to drive platelet retraction [26].

Hemostasis vs. thrombosis

While hemostasis targets vascular wall integrity and thrombosis targets vascular wall dysfunction (usually without bleeding), each with their specific transport/biorheology attributes, there certainly can be overlap in molecular players. This overlap is exemplified by the bleeding risk with antithrombotic therapies and the thrombotic risk with hemostatic therapies. Despite the overlap in the molecular mechanisms employed in hemostasis with those that underlie arterial thrombosis, there are important differences as well. Hemostatic thrombi, for example, tend to be self-limited in size, while arterial thrombi are most problematic when they become occlusive. Both are typically enriched in platelets. Venous thrombi, especially in larger veins have characteristics that distinguish them from both hemostatic and arterial thrombi, tending to have greater participation of fibrin and red cells, and fewer platelets. Given these differences, transport and hemodynamics would be expected to be quite different in these different thrombi.

HAEMOSTASIS

Core-shell architecture: porosity, diffusion, permeation

Stalker et al. [29] used P-selectin positive platelets to define the dense core region immediately adjacent to the site of a laser injury of the mouse cremaster arteriole (Fig. 1B). The core is surrounded by a shell of loosely attached, P-selectin negative platelets. In arterioles, the core and shell are free of neutrophils and RBC, which can be present in venous laser injuries. The ~10 μm-thick core region has low porosity, high platelet density, platelet retraction, reduced albumin transport relative to the shell [20], P-selectin display, localized disulfide reductase activity (unpublished observations), thrombin [23] and fibrin localization [29]. Mice with mutations in contraction (diYF mutation in β3) display increases in protein transport, indicating that retraction is operative during the first 5 min of haemostasis [16]. ADP is operative in the shell region since a P2Y12 inhibitor reduces the size of the shell [29]. The concentrations of ADP and thromboxane are calculated to be ~5 μM and 0.1 μM in the clot interior and ~0.5 μM and 0.01 μM in the concentration boundary layer, respectively, for nonocclusive clots exposed to flow [25]. A similar core-shell architecture was found for human blood perfused over collagen/TF [22,23,30] where an increase in the transclot pressure drop from 0 Pa to 3200 Pa (24 mm-Hg) reduced the thickness of thrombin and fibrin locality and the thickness of the P-selectin positive core (Fig. 2C). The permeability k of human platelet deposits formed under arterial flow is 5 × 10−14 cm2, while platelet-fibrin clots have a permeability of 2.7 × 10−14 cm2 [26], indicating that platelets provide most of the resistance to fluid loss. Using a confocal image-derived architecture of the pore space in a thrombus, Voronov et al. [18] calculated mouse hemostatic clots to have a tortuosity of T = D/Deff ~ 2 to 2.5. For this in silico architecture, a given 50 kDa nonbinding protein was calculated to escape the arterial clot in about 10 sec, quite consistent with measurements using flash activated albumin in the laser injury model [20].

Failure to achieve haemostasis under flow conditions

Excessive bleeding can be linked to inadequate platelet activation, fibrin generation, and/or fibrin crosslinking, all defects that are distal to poor thrombin production. In a study of patients with severe, moderate, and mild hemophilia deficient in FVIII, FIX, XI, or VWF, severe hemophilic blood (< 1% factor level) was linked to insufficient thrombin generation to potentiate platelet deposition under flow [31]. Moderate hemophilic blood (1–6% factor level) displayed normal levels of platelet deposition, but dysfunctional fibrin production. An aPTT greater than 40 sec predicted a distinct failure to generate fibrin under flow conditions, regardless of genotype. In similar flow studies over collagen (no TF present), with hemophilic blood supplemented with reVIIa, Li et al. [32] found that reVIIa potentiated platelet deposition with little effect on fibrin production unless the contact pathway was allowed to participate (at low corn trypsin inhibitor levels). Similarly, in perfusion studies at 100 s−1 of hemophilia A blood over TF-rich surfaces, severe deficiency (1%) was associated with defective platelet and fibrin deposition, while moderate deficiency (1–5%) had partially defective fibrin production and mild (5–30%) deficiency had relatively normal platelet and fibrin production [33]. F8−/− and F9−/− hemophilic mouse blood displays marked deficits in platelet deposition and fibrin production when perfused over a TF-rich surface [34]. These studies confirm that for healthy blood under flow conditions, TF-surfaces generate (via TF/FVIIa) triggering levels of Factor Xa and thrombin (< 1 nM) sufficient to activate platelets, but the transition to and engagement of the “intrinsic” tenase (FIXa/VIIIa) is required for the ample production of thrombin (calculated to be >10 nM in the clot [33]) to make fibrin under flow conditions.

Bleeding in the context of von Willebrand disease (VWD) also provides insights into the role of haemodynamics in physiological haemostasis. Distinct from its role as a FVIII carrier, VWF is central to platelet GPIbα-mediated capture and adhesion during clotting at physiological arterial shear rates as prerequisite for αIIbβ3- and α2β1-mediated firm arrest [35,36]. With VWD, menstrual and mucosal (gum, nose, tooth extraction) bleeding, skin bruising, ecchymosis and GI-bleeding are linked to the high shear stresses of the mucosal arterioles, with elevated fibrinolysis in these specific situations being an important cofactor. Disruption of mucosal arterioles is the likely central event of VWD since shear rates and stresses are nominally high (Table 1) [1]. Gain of function mutations in the VWF A1 domain or in platelet GPIbα receptor are distinguished by enhanced bond lifetimes [37,38] and spontaneous clearance from plasma of large VWF. Loss of function mutations in the VWF A1 domain correspond to shortened bond lifetimes and defects in haemostasis [39], suggesting that laboratory measurements of bond life times are predictive of bleeding in VWD. From a biorheological perspective, the relative roles of subendothelial VWF, acutely-released endothelial ULVWF at the bleeding site, acutely-released platelet-derived large VWF, and wall recruitment of plasma VWF remain to be prioritized during normal haemostasis and the dysfunctional haemostasis of VWD. Pathological flows and acquired vWD: Extreme shear forces can also cause an acquired VWD. Patients with aortic stenosis or mitral valve regurgitation have reduced levels of functional VWF [40,41]. In continuous left ventricle assist devices (LVAD) that generate extreme shear rates (Table 1), the degradation of vWF results in an acquired vWD [42]. ADAMTS13 inhibitors may help mitigate the progression of acquired VWD in LVAD patients [43,44].

Making thrombin and fibrin under flow

For clotting events under flow, the initiation time of thrombin/fibrin appearance and the spatial propagation of thrombin generation away from the triggering surface to sustain clot growth are central attributes of study since they are the targets of hemostatic or anti-thrombotic therapy. In microfluidic experiments, platelets adhere to collagen immediately upon contact (t = 0) with an accelerating buildup of a deposit by 150 sec via ADP and thromboxane signaling (both of which are pharmacologically targetable under flow [45,46]). While platelets adhere to collagen at the start of these flow experiments, their numbers are relatively small in the first 50 sec when compared to subsequent deposition. The onset of fibrin generation occurs at varying times depending on the wall TF level and contact pathway participation: ~60–100 sec for TF-rich surfaces [22]; ~250 to 350 to 600 sec for no TF, but high to moderate to low FXIIa engagement by contact activation [32,47]; ~200 sec for raw blood over collagen (high FXIIa, but no TF) [48]; and >600––800 sec for no TF and strong FXIIa/FXIa antagonism with high levels of CTI (50 μg/ml) and anti-FXIa antibodies [48]. In contrast, high dose CTI (50 μg/mL)-treated whole blood under static conditions will not produce thrombin for >45 min, while addition of convulxin to activate platelets via GPVI will reduce this clotting time to ~20 min [49]. The incorporation of γ′-fibrinogen into fibrin during whole blood clotting on collagen/TF appears to help limit the mobility and activity of thrombin, especially at venous shear rates [50] (Fig. 2D).

A critical threshold concentration of TF on an injured surface is required to produce thrombin and fibrin under flow conditions. This threshold concentration has been measured [27,48] (and also theoretically predicted [51]) to be in the range of ~1 to 10 molecules-TF per μm2 for small focal 250-μm long patches of collagen/TF. Extremely low levels of circulating active cofactors and factors can amplify fibrin production under flow, as was seen for exogenous addition of 100 fM of TF. The concept of a spatial patch threshold has also been developed from studies that report that plasma cannot form sufficient prothrombinase on small patches of lipid/TF (<20 μm) under stagnant and flow conditions [52,53]. For thrombin production triggered by 200-μm long lipid/TF surfaces (lacking collagen), a patch threshold was detected for flowing blood failing to clot after 1000 sec at > 80 s−1 [54]. Interestingly, flowing whole blood will always clot on 200-μm long patches of collagen/TF at 200 or 1000 s−1 [22] (as in Fig. 2C) or in the laser injury model in mouse with <20 μm focal injuries [29] (Fig. 1B). Clearly, blood biology, surface chemistry for platelet adhesion and FXa generation, shear rate, injury size, and flow all interact to dictate a clotting event.

Recently, Zhu et al. demonstrated that if low levels of TF were present on the surface (0.1 to 0.2 TF-molecules per μm2), the release of polyphosphate by activated platelets was responsible for about half the thrombin and fibrin generated for clotting at 100 or 1000 s−1 [48]. In the absence of low levels of surface TF or in the presence of high levels of TF (~1 molecule per μm2), polyphosphate function was not a significant mediator of thrombin or fibrin production, suggesting that platelet released polyphosphate enhanced a thrombin feedback mechanism. Consistent with antibody experiments that prevented FXII activation of FXI or FXI activation of FIX, the observation with low wall TF was likely due to platelet released polyphosphate having an effect on thrombin feedback activation of FXIa. Platelet polyphosphate enhancement was especially important at 5 to 7 min after initiation of clotting, consistent with predictions of delayed onset of FXIa participation in clotting [55]. There was no evidence for platelet display of TF activity under flow, since blocking antibodies against FXIa completely prevented fibrin production [55].

Clot strength under flow

Fibrin impacts both clot growth and stability. Platelet deposits lacking fibrin can withstand maximal wall shear rates up to 5300 s−1 (159 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress), while platelet/fibrin thrombi formed under flow can withstand up to 83,000 s−1 (2500 dyne/cm2) before embolization [22]. Consistent with the core/shell architecture of hemostatic clots, Colace et al. [22] observed that thrombus forming on glass coated with collagen/TF (1000 s−1) reached a height of 60 μm within 5 min, however the fibrin was found within 20 μm nearest the TF-presenting glass surface. This layered structure of thrombus may have implications on clot mechanics and embolic potential. The strength and mechanics of clotted deposits formed under flow conditions remains an area of active investigation, requiring new approaches to create a clot structure under flow and then mechanically test clot strength. For example, in a buffer shear-step up assay after thrombus growth, PAR4 signaling was found to enhance platelet deposit stability when the deposits were formed on collagen without thrombin [56].

Fibrin polymerization under flow

Both thrombin and fibrin monomer are soluble species subject to dilution by flow. Protofibril extension and lateral aggregation of fibrin are kinetic processes that proceed best under static conditions and tend to be inhibited at wall shear rates above 200 to 300 s−1, [57,58] unless anchored to cells, protected within platelet aggregates, or occurring over significant clot lengths [27] where fibrin monomer concentrations can accumulate downstream of a clotting event. Neeves et al. [59] found that the Peclet number (Pe) and Damkohler number (Da) predicted fibrin morphology (3D fibrous gels, 2D mats, thin film) for wall shear rates between 10 and 100 s−1 and thrombin wall fluxes up to 10−11 nmol/μm2-sec.

THROMBOSIS

Arterial thrombosis and stenotic flows

Computational fluid dynamics and 3D vessel reconstruction from medical imaging provides estimates of patient-specific coronary and carotid haemodynamics [60,61]. Pulsatile stenotic flow presents extreme shear rates and shear stresses, time-dependent boundary layer separation and reattachment to accommodate an eddy distal of the stenosis whose length often scales with percent stenosis, and onset of fluid mechanical turbulence if Re > 300–400 [62–64] (Fig. 2A). For human arterial stenotic flows, peak shear rates can range from ~5,000 s−1 to 100,000 s−1 (150 to >3000 dyne/cm2) with spatial wall shear rate gradients (∇γw) on the order of 105 to 106 s−1/cm [61,65].

Clearly, vWF is essential for platelet adhesion at physiological and pathological arterial shear rates, making GPIbα-VWF antagonism an attractive anti-thrombotic target. As shear rates and shear stresses become pathological, VWF will aggregate in bulk viscometry tests and expose hydropohobic domains [66,67]. Using a stenosis flow chamber, Colace et al. [68] demonstrated vWF fiber aggregation from plasma on surface collagen fibers at extreme wall shear rates (>30,000 s−1) (Fig. 2B). In contrast to VWF extension in bulk flow that likely requires elongational flows, the wall shear rate may be the most suitable metric to predict formation of vWF fibers on an adsorbing wall. Similarly, Westein et al. [69] used a stenosis device to demonstrate enhanced platelet deposition on patterned vWF/fibrinogen when wall shear rates were ~ 4000 to 8000 s−1, particularly at the apex and distal of the stenosis. The direct formation of VWF fiber aggregates without endothelium or surface-coating of collagen can also be achieved with a micropost-impingement device [70]. Once formed, VWF fibers bind platelets (Fig. 2D) which become activated to display P-selectin if shear forces are high (Fig. 2E). Pure vWF fibers formed from plasma can bind FXIIa and FXIa and serve as a substrate for fibrin polymerization if the contact pathway is intact. Pure VWF fibers from plasma were resistant to ADAMTS13 and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) but sensitive to plasmin and trypsin. Interestingly, FVIII may be released from such vWF fibers [71]. In thrombotic flows, VWF is critical, not only at the initiation of the thrombotic event for platelet capture from the flow field, but also at intermediate and terminal stages of clotting when shear forces become pathological as the clot grows into the flow stream, potentially as an additional layer of vWF captures platelets far from the triggering surface (Fig. 2A), as has been observed in vitro [68] and in vivo [72].

Also, platelet deposition has been noted to occur focally in geometries that create extreme accelerating flows. While boundary layer separation can create an eddy distal of a coronary stenosis, microfluidic devices generally operate at Low Re and such recirculation zones are uncommon unless an extreme geometry is used. Nesbitt et al. [73,74] demonstrated localized platelet aggregation at the apex of a severe square stenosis in a microfluidic device. In addition to the effects of extreme spatial gradients of shear rate and shear stress on platelet activation and altered platelet mass transport [75], the vWF structure/function in these extreme flows may also participate in platelet accumulation.

Shear Induced Platelet Aggregation/Activation (SIPA) has been studied for >40 years to gain insight into platelet dysfunction induced by artificial devices, stenotic flows, and vWD. Whole blood or PRP exposed to a linear shear field in a cone-and-plate viscometer will display spontaneous aggregation at shear rates > 3000 to 5000 s−1. SIPA is VWF- and GPIbα-dependent [76] and occurs with concomitant intracellular calcium mobilization [77], altered protein phosphorylation [78], release of ADP [79], and αIIbβ3 activation [80]. Typically, platelet lysis is not part of SIPA unless shear stress exceeds 250 dyne/cm2. SIPA is a useful metric of biomechanical device performance (See Supplement for aggregation equations).

VWF and platelets at physiological and pathological flows

The physical size, multimer distribution, and complexity of VWF structure/function under flow have underpinned numerous clinical observations. Some established observations at physiological flows: (1) low levels or dysfunctional VWF results in a spectrum of bleeding phenotypes of von Willebrand disease (VWD); (2) Deficiency of ADAMTS13 activity on VWF A2 domain causes elevated endothelial-linked ULVWF and circulating ULVWF levels and associated TTP [81,82]; (3) VWF is essential for platelet adhesion at arterial shear rates and is associated with rapid GPIbα binding kinetics (high on-rate) [83]; (4) elevated levels of VWF increase venous thrombotic risk via elevated FVIII levels [84]; (5) platelet translocation on vWF surfaces indicates high off-rate kinetics (sub-second bond life times) [37]. Some established observations at pathologically high flows are: (1) SIPA is best mediated by large VWF and ULVWF [76,85]; (2) extreme flows cause soluble plasma VWF to self-associate into insoluble aggregates and fibers [67,68,86]; and (3) extreme flows in assist devices, valve stenosis, and coarctation lead to degradation of large VWF and associated bleeding risks [87–89]. Difficult to resolve issues are: (1) what are the relative roles of force-induced A1 affinity modulation vs. A1 hindrance by local domains vs. A1 hindrance within globular VWF? (2) To what extent is GPIbα-A1 interaction a rapid off-rate reaction typified by slip-bond kinetics vs. catch-slip bond kinetics during arterial thrombosis when VWF is most operative? (3) To what extent is hydrodynamic thresholding [37] at venous wall shear rate (~100 s−1) a result of single bond kinetics (i.e. catch bonding), cellular deformation, vs. multiple bonding adhesion dynamics? (4) To what extent do bulk elongational forces vs. extreme shear rates vs. wall-binding events result in the coil-stretch transition for VWF into an elongated fibrous structure during arterial thrombosis? (5) What are the relative roles of VWF elongation vs. platelet gradient sensing in clotting at extreme flows ? and (6) If shear is required for A2 domain exposure to ADAMTS13, why does ADAMTS13 bind ULVWF and release acutely-secreted uLVWF under static conditions lacking platelets [90]?

Venous thrombosis

The haemodynamics of venous thrombosis and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are quite distinct from coronary thrombosis: vein valve dysfunction is thought to create zones of poor mixing with stasis resulting in valve thrombosis. Upstream of a thrombosed valve, the resulting pressurization of the great veins causes massive vessel distension (the radiological signature), which likely drives endothelial dysfunction. Whereas rupture of plaque laden with TF drives arterial thrombosis, DVT is typically associated with stasis and either circulating TF [91] or intravascular production of TF by monocytes [92]. In concert with hypoxia and hyperacidosis, the role of low/no flow and hyperdistension on endothelial phenotype requires further study as a trigger in DVT.

Venous clots formed under low flow or no flow conditions are massive (often > 10-cm long) and rich in RBC, but can also have platelet-rich lines of Zahn regions. Stenosed vein valves can create high velocities but also create poorly mixed eddy regions and large pressure drop, setting the stage for thrombosis [8]. For a retrieved human pulmonary embolism [93], image analysis indicates that ~ 50 % of the clot “solid” volume was RBC and ~ 50% of the “pore” volume was retracted fibrin/platelets (with 25 % of the pore volume being platelets, indicative of a platelet density in the pore space that is 100-fold greater than PRP). Additionally, at pathologically low flows (< 100 s−1), RBC can adhere to activated platelets and neutrophils, binding events that are not seen at physiological shear rates [94]. Aleman et al. [95] demonstrated that FXIIIa bound to fibrinogen was critical for fibrin crosslinking and RBC retention. RBC retention during platelet-driven clot retraction was an important determinant of overall clot volume and required α–α crosslinks in fibrin but not transglutaminase activity on RBC substrates [96].

At venous wall shear rates and wall shear stresses (~100 s−1 and 1–2 dyne/cm2), neutrophil adhesive mechanisms involving endothelial or platelet P-selectin are fully operative. Platelet-platelet adhesion at venous shear rates is fully supported by αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interactions without a strict requirement for VWF. Neutrophil NETosis [97] and contact pathway activation [92] may also help drive DVT propagation. The in situ aging of venous thrombi for 1–2 weeks is associated with dramatic biomechanical stiffening due to replacement of fibrin by collagen [98]. External compression therapy prophylaxis of DVT was recently shown to result in diameter reductions in the peroneal veins with a 4-fold increase in wall shear stress and an associated increase in flow velocities [99]. To date, diagnostics based on biorheology metrics (plasma viscosity, hematocrit, RBC aggregation ability, thromboelastography) remain of limited utility for prediction of venous thromboembolic risk.

CONCLUSION

Implications of transport and biorheology for therapy

While challenging, finding drug approaches to target thrombosis without increased bleeding risks have focused on: (1) FXIIa, (2) FXIa, (3) platelet polyphosphate, (4) GPIbα-vWF bonding and (5) SIPA operative in arterial thrombosis, and (5) stenotic shear-induced drug release. Flow and transport can influence pharmacology in certain instances because platelets accumulate to great concentrations at the site of clotting (compared to PRP or whole blood in a tube). For example, apyrase degrades platelet-released ATP and ADP sufficiently fast in the tube, but apyrase actually promotes clotting under flow due to conversion of platelet-released ATP to ADP [100].

Blood and its components operate under a wide range of haemodynamics conditions, from stasis to depressed flows, from venous to arterial flows, to extreme flows of stenosis or other pathologies. Molecular and cellular mechanics, as well as biochemical kinetics, can be understood in the context of the macroscopic haemodynamics of vessel flow. Fortunately, numerous approaches exist for in vitro and in vivo study of blood function under relevant flow conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 HL103419, P01 HL40387, and P01 HL112722. The authors thank their many colleagues for fruitful discussions and the many scientists and researchers who have collaborated on this research.

Abbreviations

- ADAMTS13

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif

- DVT

deep vein thrombosis

- SIPA

shear induced platelet aggregation

- TF

tissue factor

- TTP

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- VWF

von Willebrand factor

- ULVWF

ultralarge VWF

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

L. F. Brass reports grants from The NIH during the conduct of the study as well as personal fees from Merck Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work.

S. L. Diamond has nothing to declare.

Addendum

L. F. Brass and S. L. Diamond designed and wrote the study.

References

- 1.Goldsmith HL, Turitto VT. Rheological aspects of thrombosis and haemostasis: basic principles and applications. ICTH-Report--Subcommittee on Rheology of the International Committee on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 1986;55:415–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kefayati S, Holdsworth DW, Poepping TL. Turbulence intensity measurements using particle image velocimetry in diseased carotid artery models: Effect of stenosis severity, plaque eccentricity, and ulceration. J Biomech. 2014;47:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzani A, Dyverfeldt P, Ebbers T, Shadden SC. In Vivo Validation of Numerical Prediction for Turbulence Intensity in an Aortic Coarctation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:860–70. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sotiropoulos F, Borazjani I. A review of state-of-the-art numerical methods for simulating flow through mechanical heart valves. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2009;47:245–56. doi: 10.1007/s11517-009-0438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivanesan S, How TV, Black RA, Bakran A. Flow patterns in the radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula: an in vitro study. J Biomech. 1999;32:915–25. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies PF, Civelek M, Fang Y, Fleming I. The atherosusceptible endothelium: endothelial phenotypes in complex haemodynamic shear stress regions in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:315–27. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohayon J, Finet G, Le Floc’h S, Cloutier G, Gharib AM, Heroux J, Pettigrew RI. Biomechanics of Atherosclerotic Coronary Plaque: Site, Stability and In Vivo Elasticity Modeling. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;42:269–79. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajd F, Vidmar J, Fabjan A, Blinc A, Kralj E, Bizjak N, Serša I. Impact of altered venous hemodynamic conditions on the formation of platelet layers in thromboemboli. Thromb Res. 2012;129:158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogelson AL, Neeves KB. Fluid Mechanics of Blood Clot Formation. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2015;47:377–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev-fluid-010814-014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh C, Eckstein EC. Transient lateral transport of platelet-sized particles in flowing blood suspensions. Biophys J. 1994;66:1706–16. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80962-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vahidkhah K, Diamond SL, Bagchi P. Platelet dynamics in three-dimensional simulation of whole blood. Biophys J. 2014;106:2529–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanne EE, Aucoin CP, Leonard EF. Shear rate and hematocrit effects on the apparent diffusivity of urea in suspensions of bovine erythrocytes. ASAIO J. 56:151–6. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181d4ed0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li R, Elmongy H, Sims C, Diamond S. Ex vivo recapitulation of trauma-induced coagulopathy and preliminary assessment of trauma patient platelet function under flow usign microfluidic technology. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000915. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei H, Fedosov DA, Caswell B, Karniadakis GE. Blood flow in small tubes: quantifying the transition to the non-continuum regime. J Fluid Mech. 2013:722. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2013.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stalker TJ, Traxler EA, Wu J, Wannemacher KM, Cermignano SL, Voronov R, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Hierarchical organization in the hemostatic response and its relationship to the platelet-signaling network. Blood. 2013;121:1875–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stalker TJ, Welsh JD, Tomaiuolo M, Wu J, Colace TV, Diamond SL, Brass LF. A systems approach to hemostasis: 3. Thrombus consolidation regulates intrathrombus solute transport and local thrombin activity. Blood. 2014;124:1824–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brass LF, Zhu L, Stalker TJ. Minding the gaps to promote thrombus growth and stability. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3385–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI26869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voronov RS, Stalker TJ, Brass LF, Diamond SL. Simulation of intrathrombus fluid and solute transport using in vivo clot structures with single platelet resolution. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41:1297–307. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0764-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond SL. Engineering design of optimal strategies for blood clot dissolution. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:427–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsh JD, Stalker TJ, Voronov R, Muthard RW, Tomaiuolo M, Diamond SL, Brass LF. A systems approach to hemostasis: 1. The interdependence of thrombus architecture and agonist movements in the gaps between platelets Blood. 2014;124:1808–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hathcock JJ, Nemerson Y. Platelet deposition inhibits tissue factor activity: in vitro clots are impermeable to factor Xa. Blood. 2004;104:123–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colace TV, Muthard RW, Diamond SL. Thrombus growth and embolism on tissue factor-bearing collagen surfaces under flow: role of thrombin with and without fibrin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1466–76. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.249789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh JD, Colace TV, Muthard RW, Stalker TJ, Brass LF, Diamond SL. Platelet-targeting sensor reveals thrombin gradients within blood clots forming in microfluidic assays and in mouse. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2344–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomaiuolo M, Stalker TJ, Welsh JD, Diamond SL, Sinno T, Brass LF. A systems approach to hemostasis: 2. Computational analysis of molecular transport in the thrombus microenvironment Blood. 2014;124:1816–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flamm MH, Colace TV, Chatterjee MS, Jing H, Zhou S, Jaeger D, Brass LF, Sinno T, Diamond SL. Multiscale prediction of patient-specific platelet function under flow. Blood. 2012;120:190–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muthard RW, Diamond SL. Blood clots are rapidly assembled hemodynamic sensors: flow arrest triggers intraluminal thrombus contraction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2938–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okorie UM, Denney WS, Chatterjee MS, Neeves KB, Diamond SL. Determination of surface tissue factor thresholds that trigger coagulation at venous and arterial shear rates: amplification of 100 fM circulating tissue factor requires flow. Blood. 2008;111:3507–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leiderman K, Fogelson AL. Grow with the flow: a spatial-temporal model of platelet deposition and blood coagulation under flow. Math Med Biol. 2011;28:47–84. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqq005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stalker TJ, Traxler EA, Wu J, Wannemacher KM, Cermignano SL, Voronov R, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Hierarchical organization in the hemostatic response and its relationship to the platelet-signaling network. Blood. 2013;121:1875–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthard RW, Diamond SL. Side view thrombosis microfluidic device with controllable wall shear rate and transthrombus pressure gradient. Lab Chip. 2013;13:1883–91. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41332b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colace TV, Fogarty PF, Panckeri KA, Li R, Diamond SL. Microfluidic assay of hemophilic blood clotting: distinct deficits in platelet and fibrin deposition at low factor levels. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:147–58. doi: 10.1111/jth.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R, Panckeri KA, Fogarty PF, Diamond SL. Recombinant factor VIIa enhances platelet deposition from flowing haemophilic blood but requires the contact pathway to promote fibrin deposition. Haemophilia. 2014;21(2):266–74. doi: 10.1111/hae.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onasoga-Jarvis Aa, Leiderman K, Fogelson AL, Wang M, Mancos-Johnson MJ, Di Paola Ja, Neeves KB. The effect of factor VIII deficiencies and replacement and bypass therapies on thrombus formation under venous flow conditions in microfluidic and computational models. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swieringa F, Kuijpers MJE, Lamers MME, van der Meijden PEJ, Heemskerk JWM. Rate-limiting roles of the tenase complex of factors VIII and IX in platelet procoagulant activity and formation of platelet-fibrin thrombi under flow. Haematologica. 2015;100:748–56. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.116863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alevriadou BR, Moake JL, Turner NA, Ruggeri ZM, Folie BJ, Phillips MD, Schreiber AB, Hrinda ME, McIntire LV. Real-time analysis of shear-dependent thrombus formation and its blockade by inhibitors of von Willebrand factor binding to platelets. Blood. 1993;81:1263–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goto S, Ikeda Y, Saldívar E, Ruggeri ZM. Distinct mechanisms of platelet aggregation as a consequence of different shearing flow conditions. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:479–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doggett TA, Girdhar G, Lawshe A, Schmidtke DW, Laurenzi IJ, Diamond SL, Diacovo TG. Selectin-like kinetics and biomechanics promote rapid platelet adhesion in flow: the GPIb(alpha)-vWF tether bond. Biophys J. 2002;83:194–205. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75161-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doggett TA, Girdhar G, Lawshe A, Miller JL, Laurenzi IJ, Diamond SL, Diacovo TG. Alterations in the intrinsic properties of the GPIbα-VWF tether bond define the kinetics of the platelet-type von Willebrand disease mutation, Gly233Val. Blood. 2003;102:152–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Zhou H, Diacovo A, Zheng XL, Emsley J, Diacovo TG. Exploiting the kinetic interplay between GPIbα-VWF binding interfaces to regulate hemostasis and thrombosis. Blood. 2014;124:3799–807. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-569392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollestelle MJ, Loots CM, Squizzato A, Renné T, Bouma BJ, de Groot PG, Lenting PJ, Meijers JCM, Gerdes VEA. Decreased active von Willebrand factor level owing to shear stress in aortic stenosis patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:953–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackshear JL, Wysokinska EM, Safford RE, Thomas CS, Shapiro BP, Ung S, Stark ME, Parikh P, Johns GS, Chen D. Shear stress-associated acquired von Willebrand syndrome in patients with mitral regurgitation. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1966–74. doi: 10.1111/jth.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crow S, Chen D, Milano C, Thomas W, Joyce L, Piacentino V, Sharma R, Wu J, Arepally G, Bowles D, Rogers J, Villamizar-Ortiz N. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in continuous-flow ventricular assist device recipients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.099. discussion 1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rauch A, Legendre P, Christophe OD, Goudemand J, van Belle E, Vincentelli A, Denis CV, Susen S, Lenting PJ. Antibody-based prevention of von Willebrand factor degradation mediated by circulatory assist devices. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:1014–23. doi: 10.1160/TH14-02-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartoli CR, Kang J, Restle DJ, Zhang DM, Shabahang C, Acker MA, Atluri P. Inhibition of ADAMTS-13 by Doxycycline Reduces von Willebrand Factor Degradation During Supraphysiological Shear Stress: Therapeutic Implications for Left Ventricular Assist Device-Associated Bleeding. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(11):860–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li R, Fries S, Li X, Grosser T, Diamond SL. Microfluidic assay of platelet deposition on collagen by perfusion of whole blood from healthy individuals taking aspirin. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1195–204. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.198101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li R, Diamond SL. Detection of platelet sensitivity to inhibitors of COX-1, P2Y, and P2Y using a whole blood microfluidic flow assay. Thromb Res. 2013;3848:515–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu S, Diamond SL. Contact activation of blood coagulation on a defined kaolin/collagen surface in a microfluidic assay. Thromb Res. 2014;134:1335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu S, Travers RJ, Morrissey JH, Diamond SL. FXIa and platelet polyphosphate as therapeutic targets during human blood clotting on collagen/tissue factor surfaces under flow. Blood. 2015;126:1494–502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-641472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterjee MS, Denney WS, Jing H, Diamond SL. Systems biology of coagulation initiation: kinetics of thrombin generation in resting and activated human blood. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:1000950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muthard RW, Welsh JD, Brass LF, Diamond SL. Fibrin, γ′-Fibrinogen, and Transclot Pressure Gradient Control Hemostatic Clot Growth During Human Blood Flow Over a Collagen/Tissue Factor Wound. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(3):645–54. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuharsky AL, Fogelson AL. Surface-Mediated Control of Blood Coagulation: The Role of Binding Site Densities and Platelet Deposition. Biophys J. 2001;80:1050–74. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kastrup CJ, Runyon MK, Shen F, Ismagilov RF. Modular chemical mechanism predicts spatiotemporal dynamics of initiation in the complex network of hemostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15747–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605560103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Onasoga-Jarvis AA, Puls TJ, O’Brien SK, Kuang L, Liang HJ, Neeves KB. Thrombin generation and fibrin formation under flow on biomimetic tissue factor-rich surfaces. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:373–82. doi: 10.1111/jth.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen F, Kastrup CJ, Liu Y, Ismagilov RF. Threshold response of initiation of blood coagulation by tissue factor in patterned microfluidic capillaries is controlled by shear rate. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2035–41. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fogelson AL, Hussain YH, Leiderman K. Blood clot formation under flow: the importance of factor XI depends strongly on platelet count. Biophys J. 2012;102:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neeves KB, Maloney SF, Fong KP, Schmaier AA, Kahn ML, Brass LF, Diamond SL. Microfluidic focal thrombosis model for measuring murine platelet deposition and stability: PAR4 signaling enhances shear-resistance of platelet aggregates. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guy RD, Fogelson AL, Keener JP. Fibrin gel formation in a shear flow. Math Med Biol. 2007;24:111–30. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dql022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tijburg PN, Ijsseldijk MJ, Sixma JJ, de Groot PG. Quantification of fibrin deposition in flowing blood with peroxidase-labeled fibrinogen. High shear rates induce decreased fibrin deposition and appearance of fibrin monomers. Arterioscler Thromb. 11:211–20. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neeves KB, Illing DAR, Diamond SL. Thrombin flux and wall shear rate regulate fibrin fiber deposition state during polymerization under flow. Biophys J. 2010;98:1344–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim HJ, Vignon-Clementel IE, Coogan JS, Figueroa CA, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. Patient-specific modeling of blood flow and pressure in human coronary arteries. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:3195–209. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schirmer CM, Malek AM. Patient based computational fluid dynamic characterization of carotid bifurcation stenosis before and after endovascular revascularization. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:448–54. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Long Q, Xu XY, Ramnarine KV, Hoskins P. Numerical investigation of physiologically realistic pulsatile flow through arterial stenosis. J Biomech. 2001;34:1229–42. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ojha M, Cobbold RS, Johnston KW, Hummel RL. Detailed visualization of pulsatile flow fields produced by modelled arterial stenoses. J Biomed Eng. 1990;12:463–9. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(90)90055-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young DF, Tsai FY. Flow characteristics in models of arterial stenoses. II. Unsteady flow. J Biomech. 1973;6:547–59. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(73)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Banerjee RK, Back LH, Back MR, Cho YI. Physiological flow analysis in significant human coronary artery stenoses. Biorheology. 2003;40:451–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shankaran H, Alexandridis P, Neelamegham S. Aspects of hydrodynamic shear regulating shear-induced platelet activation and self-association of von Willebrand factor in suspension. Blood. 2003;101:2637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh I, Themistou E, Porcar L, Neelamegham S. Fluid shear induces conformation change in human blood protein von Willebrand factor in solution. Biophys J. 2009;96:2313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colace TV, Diamond SL. Direct observation of von Willebrand Factor elongation and fiber formation on collagen during acute whole blood exposure to pathological flow. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:105–13. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westein E, van der Meer AD, Kuijpers MJE, Frimat J-P, van den Berg A, Heemskerk JWM. Atherosclerotic geometries exacerbate pathological thrombus formation poststenosis in a von Willebrand factor-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209905110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herbig BA, Diamond SL. Pathological von Willebrand factor fibers resist tissue plasminogen activator and ADAMTS13 while promoting the contact pathway and shear-induced platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1699–708. doi: 10.1111/jth.13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonazza K, Rottensteiner H, Schrenk G, Frank J, Allmaier G, Turecek PL, Scheiflinger F, Friedbacher G. Shear-Dependent Interactions of von Willebrand Factor with Factor VIII and Protease ADAMTS 13 Demonstrated at a Single Molecule Level by Atomic Force Microscopy. Anal Chem. 2015;87:150930065241003. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le Behot A, Gauberti M, Martinez De Lizarrondo S, Montagne A, Lemarchand E, Repesse Y, Guillou S, Denis CV, Maubert E, Orset C, Vivien D. GpIbα-VWF blockade restores vessel patency by dissolving platelet aggregates formed under very high shear rate in mice. Blood. 2014;123:3354–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-543074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nesbitt WS, Westein E, Tovar-Lopez FJ, Tolouei E, Mitchell A, Fu J, Carberry J, Fouras A, Jackson SP. A shear gradient-dependent platelet aggregation mechanism drives thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2009;15:665–73. doi: 10.1038/nm.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tovar-Lopez FJ, Rosengarten G, Westein E, Khoshmanesh K, Jackson SP, Mitchell A, Nesbitt WS. A microfluidics device to monitor platelet aggregation dynamics in response to strain rate micro-gradients in flowing blood. Lab Chip. 2010;10:291–302. doi: 10.1039/b916757a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tovar-Lopez FJ, Rosengarten G, Nasabi M, Sivan V, Khoshmanesh K, Jackson SP, Mitchell A, Nesbitt WS. An investigation on platelet transport during thrombus formation at micro-scale stenosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moake JL, Turner NA, Stathopoulos NA, Nolasco LH, Hellums JD. Involvement of large plasma von Willebrand factor (vWF) multimers and unusually large vWF forms derived from endothelial cells in shear stress-induced platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1456–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI112736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chow TW, Hellums JD, Moake JL, Kroll MH. Shear stress-induced von Willebrand factor binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib initiates calcium influx associated with aggregation. Blood. 1992;80:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Razdan K, Hellums JD, Kroll MH. Shear-stress-induced von Willebrand factor binding to platelets causes the activation of tyrosine kinase(s) Biochem J. 1994;302(3):681–6. doi: 10.1042/bj3020681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moake JL, Turner NA, Stathopoulos NA, Nolasco L, Hellums JD. Shear-induced platelet aggregation can be mediated by vWF released from platelets, as well as by exogenous large or unusually large vWF multimers, requires adenosine diphosphate, and is resistant to aspirin. Blood. 1988;71:1366–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Konstantopoulos K, Kamat SG, Schafer AI, Bañez EI, Jordan R, Kleiman NS, Hellums JD. Shear-induced platelet aggregation is inhibited by in vivo infusion of an anti-glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antibody fragment, c7E3 Fab, in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1995;91:1427–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moake JL, Rudy CK, Troll JH, Weinstein MJ, Colannino NM, Azocar J, Seder RH, Hong SL, Deykin D. Unusually large plasma factor VIII:von Willebrand factor multimers in chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1432–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212023072306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Levy GG, Nichols WC, Lian EC, Foroud T, McClintick JN, McGee BM, Yang AY, Siemieniak DR, Stark KR, Gruppo R, Sarode R, Shurin SB, Chandrasekaran V, Stabler SP, Sabio H, Bouhassira EE, Upshaw JD, Jr, Ginsburg D, Tsai HM. Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nature. 2001;413:488–94. doi: 10.1038/35097008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Savage B, Saldivar E, Ruggeri ZM. Initiation of platelet adhesion by arrest onto fibrinogen or translocation on von Willebrand factor. Cell. 1996;84:289–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Visser MCH, Sandkuijl LA, Lensen RPM, Vos HL, Rosendaal FR, Bertina RM. Linkage analysis of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor loci as quantitative trait loci. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1771–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Konstantopoulos K, Chow TW, Turner NA, Hellums JD, Moake JL. Shear stress-induced binding of von Willebrand factor to platelets. Biorheology. 1997;34:57–71. doi: 10.1016/S0006-355X(97)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shankaran H, Neelamegham S. Hydrodynamic forces applied on intercellular bonds, soluble molecules, and cell-surface receptors. Biophys J. 2004;86:576–88. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pareti FI, Lattuada A, Bressi C, Zanobini M, Sala A, Steffan A, Ruggeri ZM. Proteolysis of von Willebrand factor and shear stress-induced platelet aggregation in patients with aortic valve stenosis. Circulation. 2000;102:1290–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loeffelbein F, Funk D, Nakamura L, Zieger B, Grohmann J, Siepe M, Kroll J, Stiller B. Shear-stress induced acquired von Willebrand syndrome in children with congenital heart disease. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19:926–32. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goda M, Jacobs S, Rega F, Peerlinck K, Jacquemin M, Droogne W, Vanhaecke J, Van Cleemput J, Van den Bossche K, Meyns B. Time course of acquired von Willebrand disease associated with two types of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: HeartMate II and CircuLite Synergy Pocket Micro-pump. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:539–45. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turner N, Nolasco L, Moake J. Generation and breakdown of soluble ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:38–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thomas GM, Brill A, Mezouar S, Crescence L, Gallant M, Dubois C, Wagner DD. Tissue factor expressed by circulating cancer cell-derived microparticles drastically increases the incidence of deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1310–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Von Brühl M-L, Stark K, Steinhart A, Chandraratne S, Konrad I, Lorenz M, Khandoga A, Tirniceriu A, Coletti R, Köllnberger M, Byrne RA, Laitinen I, Walch A, Brill A, Pfeiler S, Manukyan D, Braun S, Lange P, Riegger J, Ware J, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209:819–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aleman MM, Walton BL, Byrnes JR, Wolberg AS. Fibrinogen and red blood cells in venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2014;133(Suppl):S38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goel MS, Diamond SL. Adhesion of normal erythrocytes at depressed venous shear rates to activated neutrophils, activated platelets, and fibrin polymerized from plasma. Blood. 2002;100:3797–803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aleman MM, Byrnes JR, Wang J-G, Tran R, Lam WA, Di Paola J, Mackman N, Degen JL, Flick MJ, Wolberg AS. Factor XIII activity mediates red blood cell retention in venous thrombi. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3590–600. doi: 10.1172/JCI75386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Byrnes JR, Duval C, Wang Y, Hansen CE, Ahn B, Mooberry MJ, Clark MA, Johnsen JM, Lord ST, Lam W, Meijers JCM, Ni H, Ariëns RAS, Wolberg AS. Factor XIIIa-dependent retention of red blood cells in clots is mediated by fibrin α-chain crosslinking. Blood. 2015;126:1940–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-652263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) impact on deep vein thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1777–83. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee Y-U, Lee AY, Humphrey JD, Rausch MK. Histological and biomechanical changes in a mouse model of venous thrombus remodeling. Biorheology. 2015;52:235–45. doi: 10.3233/BIR-15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang Y, Pierce I, Gatehouse P, Wood N, Firmin D, Xu XY. Analysis of flow and wall shear stress in the peroneal veins under external compression based on real-time MR images. Med Eng Phys. 2012;34:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maloney SF, Brass LF, Diamond SL. P2Y12 or P2Y1 inhibitors reduce platelet deposition in a microfluidic model of thrombosis while apyrase lacks efficacy under flow conditions. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2:183–92. doi: 10.1039/b919728a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jung J, Hassanein A, Lyczkowski RW. Hemodynamic computation using multiphase flow dynamics in a right coronary artery. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:393–407. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang J-M, Luo T, Tan SY, Lomarda AM, Wong ASL, Keng FYJ, Allen JC, Huo Y, Su B, Zhao X, Wan M, Kassab GS, Tan RS, Zhong L. Hemodynamic analysis of patient-specific coronary artery tree. Int j numer method biomed eng. 2015;31:e02708. doi: 10.1002/cnm.2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kroll MH, Hellums JD, McIntire LV, Schafer AI, Moake JL. Platelets and shear stress. Blood. 1996;88:1525–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lawrence MB, McIntire LV, Eskin SG. Effect of flow on polymorphonuclear leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. Blood. 1987;70:1284–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fedosov DA, Pan W, Caswell B, Gompper G, Karniadakis GE. Predicting human blood viscosity in silico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11772–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101210108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lawrence MB, Kansas GS, Kunkel EJ, Ley K. Threshold levels of fluid shear promote leukocyte adhesion through selectins (CD62L,P,E) J Cell Biol. 1997;136:717–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kadash KE, Lawrence MB, Diamond SL. Neutrophil string formation: hydrodynamic thresholding and cellular deformation during cell collisions. Biophys J. 2004;86:4030–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Karino T, Motomiya M. Flow through a venous valve and its implication for thrombus formation. Thromb Res. 1984;36:245–57. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(84)90224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dong J-F. Cleavage of ultra-large von Willebrand factor by ADAMTS-13 under flow conditions. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1710–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Garcia J, Kadem L. Fluid dynamics of coarctation of the aorta and effect of bicuspid aortic valve. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.LaDisa JF, Alberto Figueroa C, Vignon-Clementel IE, Kim HJ, Xiao N, Ellwein LM, Chan FP, Feinstein JA, Taylor CA. Computational simulations for aortic coarctation: representative results from a sampling of patients. J Biomech Eng. 2011;133:091008. doi: 10.1115/1.4004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Javadzadegan A, Yong ASC, Chang M, Ng ACC, Yiannikas J, Ng MKC, Behnia M, Kritharides L. Flow recirculation zone length and shear rate are differentially affected by stenosis severity in human coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H559–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00428.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kefayati S, Milner JS, Holdsworth DW, Poepping TL. In vitro shear stress measurements using particle image velocimetry in a family of carotid artery models: effect of stenosis severity, plaque eccentricity, and ulceration. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schneider SW, Nuschele S, Wixforth A, Gorzelanny C, Alexander-Katz A, Netz RR, Schneider MF. Shear-induced unfolding triggers adhesion of von Willebrand factor fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7899–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608422104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chan CHH, Pieper IL, Fleming S, Friedmann Y, Foster G, Hawkins K, Thornton CA, Kanamarlapudi V. The effect of shear stress on the size, structure, and function of human von Willebrand factor. Artif Organs. 2014;38:741–50. doi: 10.1111/aor.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Girdhar G, Xenos M, Alemu Y, Chiu W-C, Lynch BE, Jesty J, Einav S, Slepian MJ, Bluestein D. Device thrombogenicity emulation: a novel method for optimizing mechanical circulatory support device thromboresistance. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Leverett LB, Hellums JD, Alfrey CP, Lynch EC. Red blood cell damage by shear stress. Biophys J. 1972;12:257–73. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(72)86085-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wufsus AR, Macera NE, Neeves KB. The hydraulic permeability of blood clots as a function of fibrin and platelet density. Biophys J. 2013;104:1812–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Collet J-P, Shuman H, Ledger RE, Lee S, Weisel JW. The elasticity of an individual fibrin fiber in a clot. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:9133–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504120102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wufsus AR, Rana K, Brown A, Dorgan JR, Liberatore MW, Neeves KB. Elastic behavior and platelet retraction in low- and high-density fibrin gels. Biophys J. 2015;108:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Slaboch CL, Alber MS, Rosen ED, Ovaert TC. Mechano-rheological properties of the murine thrombus determined via nanoindentation and finite element modeling. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;10:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ying J, Ling Y, Westfield LA, Sadler JE, Shao J-Y. Unfolding the A2 domain of von Willebrand factor with the optical trap. Biophys J. 2010;98:1685–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Litvinov RI, Barsegov V, Schissler AJ, Fisher AR, Bennett JS, Weisel JW, Shuman H. Dissociation of bimolecular αIIbβ3-fibrinogen complex under a constant tensile force. Biophys J. 2011;100:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ju L, Dong J, Cruz MA, Zhu C. The N-terminal flanking region of the A1 domain regulates the force-dependent binding of von Willebrand factor to platelet glycoprotein Ibα. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32289–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lam WA, Chaudhuri O, Crow A, Webster KD, Li T-D, Kita A, Huang J, Fletcher DA. Mechanics and contraction dynamics of single platelets and implications for clot stiffening. Nat Mater. 2011;10:61–6. doi: 10.1038/nmat2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]