Abstract

The clinical severity of sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, the major disorders of β-globin, can be ameliorated by increased production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Here, we provide a brief overview of the fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switch that occurs in humans shortly after birth and review our current understanding of one of the most potent known regulators of this switching process, the multiple zinc finger–containing transcription factor BCL11A. Originally identified in genome-wide association studies, multiple orthogonal lines of evidence have validated BCL11A as a key regulator of hemoglobin switching and as a promising therapeutic target for HbF induction. We discuss recent studies that have highlighted its importance in silencing the HbF-encoding genes and discuss opportunities that exist to further understand the regulation of BCL11A and its mechanism of action, which could provide new insight into opportunities to induce HbF for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: fetal hemoglobin, hemoglobin switching, BCL11A, thalassemia, therapy

Introduction

The disorders of β-hemoglobin, sickle cell disease (SCD), and β-thalassemia are among the most common forms of anemia in the world, with a particularly high prevalence in the developing world.1 In SCD, a single base mutation substitutes valine for glutamic acid at position six of the β-subunit of hemoglobin, resulting in the formation of sickle hemoglobin, which has an increased tendency to polymerize in the deoxygenated state.2 Consequently, red blood cells carrying high levels of sickle hemoglobin are readily deformed and can thereby block small blood vessels, impairing oxygen delivery to tissues. This can lead to clinical symptoms that include localized pain, respiratory problems, and organ damage.3 In β-thalassemia, insufficient production of mature β-globin polypeptide chains result in an excess of unpaired α-globin chains that can precipitate within erythroid precursors, impairing their maturation and leading to their death. Consequently, ineffective production of red blood cells occurs, leading to a severe anemia.4

Current treatments for the disorders of β-hemoglobin are primarily supportive. For example, red blood cell (erythrocyte) transfusions can reduce the incidence of sickle cell formation in SCD and prevent the complications of ineffective red blood cell production in β-thalassemia.5 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and gene therapy are potentially curative approaches in these diseases.4,6 However, these approaches are challenging to implement and have limitations to widespread use, particularly in the developing world.6

Fetal hemoglobin expression and disease

Hemoglobin, which is necessary for oxygen transport in the blood, is a tetramer composed of two subunits of α-globin polypeptide chains and two subunits of β-like globin polypeptides, along with heme prosthetic groups that bind to each subunit to allow effective oxygen transport. The human β-globin locus on chromosome 11, comprising five paralogous globin genes, is developmentally regulated, and therefore multiple distinct β-like globin molecules are produced during human development.7 ε-Globin is the major embryonic β-like hemoglobin expressed within the primitive erythrocyte lineage that is produced in the first trimester of gestation.8 Soon after and throughout the rest of the gestational period, γ-globin, encoded by two duplicated genes within the β-globin gene locus, is the major β-like globin expressed.9 The γ-globin chains associate with adult α-globin polypeptides to form fetal hemoglobin (HbF). In the months following birth, the expression of γ-globin is replaced by adult β-globin in a process referred to as the fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switch.

The severity of SCD and β-thalassemia can be ameliorated through increased HbF production. Initial anecdotal clinical observations showing the ameliorating effect of increased HbF production have been substantiated by larger-scale clinical studies in cohorts of patients with SCD and β-thalassemia.10-16 As a result, there has been a long-standing interest in identifying approaches to induce HbF in patients with β-hemoglobin disorders. Initial work focused on modulators of epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation, and resulted in the identification of 5-azacytidine as an inducer of HbF.17-19 However, it was unclear if such drugs worked through a direct epigenetic mechanism or through effects on cell cycle progression.20 This resulted in the testing of hydroxyurea, which is an S-phase cell cycle inhibitor, as a potential inducer of HbF. Hydroxyurea was able to induce HbF robustly in primate models,21 and subsequent studies have substantiated its ameliorating effect in patients with SCD.22 However, hydroxyurea has had limited success in β-thalassemia,23 and this is likely due to limitations in the extent of HbF that it can induce.

Molecular studies of HbF regulation identify BCL11A

To more robustly induce HbF for therapeutic purposes, an improved understanding of the molecular regulators of fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching and HbF silencing in adulthood is necessary. Early studies following the cloning of the globin genes had indicated a role for various erythroid transcription factors in globin gene regulation, including GATA1, KLF1, and SCL/TAL1,24 but all of these factors had more global roles in erythropoiesis and globin gene expression, rather than being specific regulators of HbF production.

In the past several years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that examine natural human variation in traits such as HbF expression have provided new insight.25,26 These GWAS revealed three major loci associated with HbF levels in both healthy cohorts and in patients with SCD, as well as β-thalassemia.15,26,27 The significantly associated loci included a region of chromosome 2 within the BCL11A gene, an intergenic region between the genes HBS1L and MYB on chromosome 6, and polymorphisms within the β-globin gene locus on chromosome 11. Importantly, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these loci can not only increase HbF levels, but have been shown to ameliorate the clinical severity of both β-thalassemia and SCD.14,15,27,28

While previous studies had implicated the multiple zinc-finger transcription factor BCL11A in B lymphocyte production and neurodevelopment,6 GWAS highlighted a potential and previously unappreciated role for this factor in globin gene regulation. Therefore, the role of BCL11A in HbF regulation was investigated.29 Expression of full-length forms of BCL11A was highest in adult erythroid precursor cells where little γ-globin was expressed and lowest in primitive and fetal liver erythroid precursors where γ-globin is highly expressed, suggesting that BCL11A acts as a silencer of the HbF-encoding genes.29 Consequently, RNA interference–mediated suppression of BCL11A led to robust induction of HbF in primary human erythroid cells.29 Additionally, the degree of γ-globin induction appeared to be linearly related to the extent of knockdown of BCL11A.29 Interestingly, no major perturbations in erythropoiesis were observed despite the robust induction of γ-globin. Subsequent studies have validated and extended these observations.30-32

In spite of the divergence of hemoglobin switching in mouse models compared to humans, an evolutionarily conserved role for BCL11A as a repressor of HbF could be demonstrated in mice.33 Transgenic mice with the human β-globin gene locus express the γ-globin genes in a pattern resembling that seen for the mouse embryonic globin genes.34 Mice with a hematopoietic- or erythroid-specific Bcl11a knockout failed to silence the HbF-encoding genes in definitive erythroid cells, resulting in expression of γ-globin, while erythropoiesis appeared to be normal.33 Additionally, hematopoietic-specific deletion of Bcl11a could reverse γ-globin silencing and prevent clinical complications in a mouse model of sickle cell disease, pointing to the potential for clinical benefit by targeting BCL11A in the disorders of β-hemoglobin.35

Studies of BCL11A regulation

Further studies of BCL11A have revealed that it appears to occupy chromatin within the human β-globin locus in primary erythroid cells, although it does not bind to the proximal promoter of the γ-globin genes.36 BCL11A also interacts with the hematopoietic transcription factors GATA1, SOX6, and ZFPM1/FOG1, as well as the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) chromatin remodeling and repressor complex.29,37 Interestingly, the NuRD complex includes HDAC1 and HDAC2, which have been reported to be critical for HbF silencing.38,39 However, despite an understanding of regions where BCL11A binds and the known identity of some partner proteins, the exact mechanisms by which BCL11A acts to silence the γ-globin genes remain unclear. In addition, multiple BCL11A isoforms have been shown to be expressed in human erythroid cells,29 yet whether there are differential roles for these various isoforms (particularly the full-length forms that are robustly expressed in adult erythroid cells and include both the XL and L isoforms) remains unknown.

Long-range interactions between BCL11A and multiple regions throughout the β-globin gene locus may mediate the silencing of the γ-globin genes, although whether this is a direct result of BCL11A suppression or an indirect effect due to γ-globin induction through another mechanism is unclear.36 In the absence of BCL11A, the conformation of the β-globin locus is altered such that its upstream enhancer, the locus control region (LCR), is juxtaposed with the transcriptionally activated γ-globin genes. BCL11A also has been shown to bind to several other transcriptional co-repressors, including the LSD1/CoREST (lysine demethylase/corepressor to repressor element 1–silencing transcription factor), SWI/SNF (mating-type switching/sucrose non-fermenting), and NCoR/SMRT (nuclear receptor co-repressor/silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors) complexes,37 although the extent to which each of these complexes may contribute to γ-globin silencing via BCL11A remains unclear.

The erythroid-specific transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 1 (KLF1) has been suggested to be a positive regulator of BCL11A expression in both mouse models and in human cells.3 In mice with a hypomorphic allele of Klf1, elevated embryonic globin expression was observed and suggested to be due to reduced BCL11A expression.40 Some patients with KLF1 missense mutations have been suggested to have persistence of HbF expression due to reduced transcription of BCL11A in erythroid cells, although there is variable HbF expression in some patients and BCL11A is only partially silenced by reducing KLF1 expression, suggesting that more complex mechanisms may underlie such observations.30

Further insight into the mechanism of action of BCL11A has been gained through the study of natural human deletions in the β-globin gene locus.41 Some deletions in the β-globin gene locus allow for robust HbF production in a condition termed hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH), while other conditions produce lower levels of HbF and are categorized by the term δβ-thalassemia. By mapping the differences between these conditions in a large number of cases, a ~ 3-kb region upstream of the δ-globin gene was shown to potentially have a key role in HbF silencing.42 Interestingly, this region shows chromatin occupancy by BCL11A, along with GATA1 and HDAC1, suggesting a potential mechanism through which this difference in HbF expression may be mediated. Subsequent studies have built upon and extended these observations.43,44

More recent work has also identified erythroid-specific regulatory elements of BCL11A that may harbor the common genetic variation identified through GWAS.45 Direct allele-specific effects for the variants within this region remain to be demonstrated in an isogenic setting. However, the key role of these regions in erythroid BCL11A mRNA expression strongly suggest that disruption of these elements by genome editing may be a promising therapeutic approach to induce HbF.46,47

Despite many outstanding questions about the mechanism through which BCL11A acts, it remains a promising therapeutic target. However, the extent to which BCL11A has a role in silencing HbF in humans and its other roles in vivo were unknown. Recent studies on rare human patients with small deletions involving BCL11A have shown that such patients can have substantial persistence of HbF, typically ranging between 15% and 30%.48 Haploinsufficiency of BCL11A could be demonstrated, and no other perturbations of hematologic or immunologic parameters could be found in the patients. Similar follow-up studies involving larger deletions, which may have some extent of compensation,49 have shown persistence of HbF,50 albeit to a lesser extent than patients with more limited deletions involving BCL11A. In addition, studies of such patients have also revealed that BCL11A is a key neurodevelopmental regulator that may also have a role in adult neural homeostasis,48 thus highlighting potential side effects that must be monitored in ongoing efforts to develop therapies aimed at perturbing BCL11A. Further studies of such in vivo phenotypes will likely provide important insight into the role of BCL11A in humans.

Outstanding questions and future opportunities

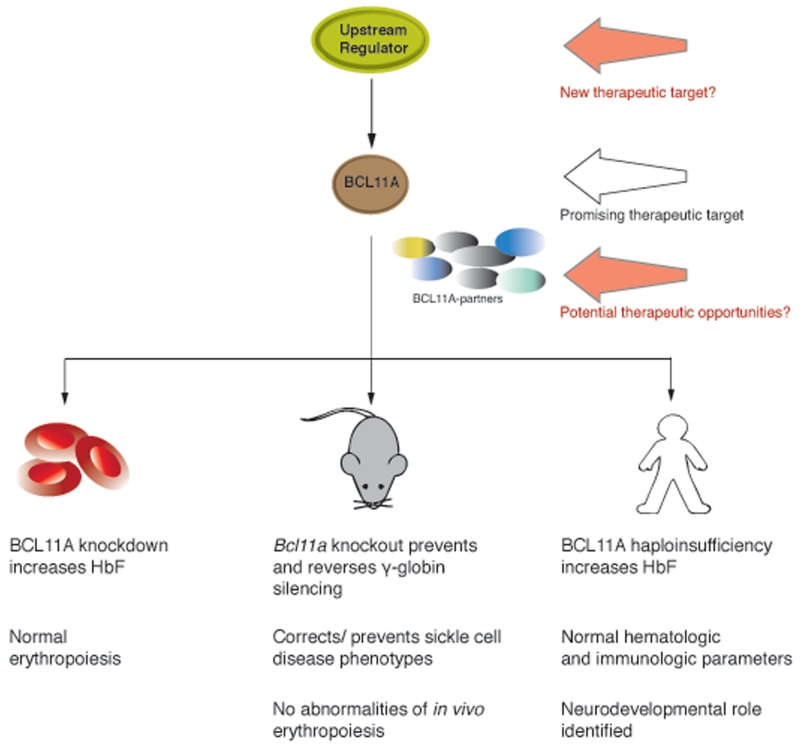

Given the work done on BCL11A, it is clearly a promising therapeutic target for HbF induction (Fig. 1). While gene therapy and genome editing approaches have focused on either introducing corrective globin genes or repairing primary mutations in β-hemoglobin disorders, an alternative approach would be to use such approaches to suppress BCL11A.4 Indeed, some preclinical studies have already shown effectiveness in using these approaches.31,51 While such efforts could provide important proof-of-principle demonstrations for targeting BCL11A, it is difficult to envision how such approaches can be effectively scaled to treat the extremely large number of patients with β-hemoglobin disorders worldwide.

Figure 1.

Therapeutic opportunities for targeting BCL11A to induce HbF and evidence highlighting their effectiveness and limitations. BCL11A is among the most promising of the therapeutic targets for induction of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and is depicted in brown. Other molecular partners of BCL11A are shown as a group of variably colored spheres. In green is a potential upstream regulator of BCL11A, which could represent a new therapeutic target for modulating BCL11A expression. The evidence for therapeutic effectiveness and potential limitations for modulating BCL11A from primary human cell culture systems, mouse models, and in vivo from human patients is summarized below.

As such, several important basic science questions need to be addressed to potentially identify more accessible opportunities to develop treatments aimed at altering BCL11A or its cofactors. As discussed above, the mechanisms by which BCL11A acts to silence the γ-globin genes remain unknown. Further mechanistic studies could provide important insight into how this process occurs and may identify opportunities to selectively alter BCL11A activity during this process. For example, by identifying key enzymatic cofactors of BCL11A or interacting partners, opportunities for therapeutic intervention may be identified. In addition, as discussed above, BCL11A expression is regulated during human development.29 The factors and mechanisms that underlie this regulation remain to be identified, but this may provide an important opportunity for therapeutic manipulation, as fetal erythroid cells have a similar overall developmental program as adults and understanding key differences could provide an opportunity to reverse ontogeny while not perturbing the normal erythroid differentiation program.

Clearly, a number of outstanding questions remain. However, if progress over the past several years is any indication, there is likely to be significant insight gained in the coming years. Indeed, it has only been approximately 8 years since BCL11A was first identified as a silencing factor of HbF, and a great deal of insight has already been gained. We suspect that basic scientific studies will provide additional important insight in the coming years that we hope will lead to new and more effective approaches for HbF induction.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Sankaran laboratory for helpful comments, discussions, and suggestions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (U01 HL117720, R01 DK103794, R21 HL120791).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood. 2010;115:4331–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-251348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sankaran VG. Targeted therapeutic strategies for fetal hemoglobin induction. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:459–465. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankaran VG, Weiss MJ. Anemia: progress in molecular mechanisms and therapies. Nature medicine. 2015;21:221–230. doi: 10.1038/nm.3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter JB, Shah FT. Iron overload in thalassemia and related conditions: therapeutic goals and assessment of response to chelation therapies. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2010;24:1109–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankaran VG, Nathan DG. Thalassemia: an overview of 50 years of clinical research. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2010;24:1005–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankaran VG, Nathan DG. Reversing the hemoglobin switch. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:2258–2260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1010767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peschle C, et al. Haemoglobin switching in human embryos: asynchrony of zeta----alpha and epsilon----gamma-globin switches in primitive and definite erythropoietic lineage. Nature. 1985;313:235–238. doi: 10.1038/313235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sankaran VG, Xu J, Orkin SH. Advances in the understanding of haemoglobin switching. British journal of haematology. 2010;149:181–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platt OS, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. The New England journal of medicine. 1994;330:1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt OS, et al. Pain in sickle cell disease. Rates and risk factors. The New England journal of medicine. 1991;325:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107043250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro O, et al. The acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: incidence and risk factors. The Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 1994;84:643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Premawardhena A, et al. Haemoglobin E beta thalassaemia in Sri Lanka. Lancet. 2005;366:1467–1470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galanello R, et al. Amelioration of Sardinian beta0 thalassemia by genetic modifiers. Blood. 2009;114:3935–3937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuinoon M, et al. A genome-wide association identified the common genetic variants influence disease severity in beta0-thalassemia/hemoglobin E. Human genetics. 2010;127:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0770-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musallam KM, et al. Fetal hemoglobin levels and morbidity in untransfused patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia. Blood. 2012;119:364–367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-382408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ley TJ, et al. 5-azacytidine selectively increases gamma-globin synthesis in a patient with beta+ thalassemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1982;307:1469–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212093072401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ley TJ, et al. 5-Azacytidine increases gamma-globin synthesis and reduces the proportion of dense cells in patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 1983;62:370–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeSimone J, Heller P, Hall L, Zwiers D. 5-Azacytidine stimulates fetal hemoglobin synthesis in anemic baboons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79:4428–4431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.14.4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamatoyannopoulos G. Control of globin gene expression during development and erythroid differentiation. Experimental hematology. 2005;33:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letvin NL, Linch DC, Beardsley GP, McIntyre KW, Nathan DG. Augmentation of fetal-hemoglobin production in anemic monkeys by hydroxyurea. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;310:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404053101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0708272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musallam KM, Taher AT, Cappellini MD, Sankaran VG. Clinical experience with fetal hemoglobin induction therapy in patients with beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2013;121:2199–2212. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-408021. quiz 2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cantor AB, Orkin SH. Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: an affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene. 2002;21:3368–3376. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menzel S, et al. A QTL influencing F cell production maps to a gene encoding a zinc-finger protein on chromosome 2p15. Nature genetics. 2007;39:1197–1199. doi: 10.1038/ng2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uda M, et al. Genome-wide association study shows BCL11A associated with persistent fetal hemoglobin and amelioration of the phenotype of beta-thalassemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:1620–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711566105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lettre G, et al. DNA polymorphisms at the BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and beta-globin loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels and pain crises in sickle cell disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804799105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danjou F, et al. Genetic modifiers of beta-thalassemia and clinical severity as assessed by age at first transfusion. Haematologica. 2012;97:989–993. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.053504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankaran VG, et al. Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Science. 2008;322:1839–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1165409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borg J, et al. Haploinsufficiency for the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 causes hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin. Nature genetics. 2010;42:801–805. doi: 10.1038/ng.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilber A, et al. Therapeutic levels of fetal hemoglobin in erythroid progeny of beta-thalassemic CD34+ cells after lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer. Blood. 2011;117:2817–2826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Q, et al. Repression of human gamma-globin gene expression by a short isoform of the NF-E4 protein is associated with loss of NF-E2 and RNA polymerase II recruitment to the promoter. Blood. 2006;107:2138–2145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sankaran VG, et al. Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A. Nature. 2009;460:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature08243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGrath KE, et al. A transient definitive erythroid lineage with unique regulation of the beta-globin locus in the mammalian embryo. Blood. 2011;117:4600–4608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, et al. Correction of sickle cell disease in adult mice by interference with fetal hemoglobin silencing. Science. 2011;334:993–996. doi: 10.1126/science.1211053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, et al. Transcriptional silencing of {gamma}-globin by BCL11A involves long-range interactions and cooperation with SOX6. Genes & development. 2010;24:783–798. doi: 10.1101/gad.1897310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J, et al. Corepressor-dependent silencing of fetal hemoglobin expression by BCL11A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:6518–6523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303976110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradner JE, et al. Chemical genetic strategy identifies histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 as therapeutic targets in sickle cell disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12617–12622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006774107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao H, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Jung M. Induction of human gamma globin gene expression by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Blood. 2004;103:701–709. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou D, Liu K, Sun CW, Pawlik KM, Townes TM. KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. Nature genetics. 2010;42:742–744. doi: 10.1038/ng.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. The Thalassaemia Syndromes. Edn. 4th Blackwell Science; Oxford, England: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sankaran VG, et al. A functional element necessary for fetal hemoglobin silencing. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:807–814. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghedira ES, et al. Estimation of the difference in HbF expression due to loss of the 5′ delta-globin BCL11A binding region. Haematologica. 2013;98:305–308. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.061994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prakobkaew N, Fucharoen S, Fuchareon G, Siriratmanawong N. Phenotypic expression of Hb F in common high Hb F determinants in Thailand: roles of alpha-thalassemia, 5′ delta-globin BCL11A binding region and 3′ beta-globin enhancer. European journal of haematology. 2014;92:73–79. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauer DE, et al. An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Science. 2013;342:253–257. doi: 10.1126/science.1242088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canver MC, et al. BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature. 2015;527:192–7. doi: 10.1038/nature15521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vierstra J, et al. Functional footprinting of regulatory DNA. Nature methods. 2015;12:927–930. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basak A, et al. BCL11A deletions result in fetal hemoglobin persistence and neurodevelopmental alterations. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:2363–2368. doi: 10.1172/JCI81163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi A, et al. Genetic compensation induced by deleterious mutations but not gene knockdowns. Nature. 2015;524:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature14580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Funnell AP, et al. 2p15-p16.1 microdeletions encompassing and proximal to BCL11A are associated with elevated HbF in addition to neurologic impairment. Blood. 2015;126:89–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-638528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guda S, et al. miRNA-embedded shRNAs for Lineage-specific BCL11A Knockdown and Hemoglobin F Induction. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2015;23:1465–1474. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]