Abstract

The β-hemoglobinopathies are the most common monogenic disorders in humans, with symptoms arising after birth when the fetal γ-globin genes are silenced and the adult β-globin gene is activated. There is a growing appreciation that genome organization and the folding of chromosomes are key determinants of gene transcription. Underlying this function is the activity of transcriptional enhancers that increase the transcription of target genes over long linear distances. To accomplish this, enhancers engage in close physical contact with target promoters through chromosome folding or looping that is orchestrated by protein complexes that bind to both sites and stabilize their interaction. We find that enhancer activity can be redirected with concommitant changes in gene transcription. Both targeting the β-globin locus control region to the γ-globin gene in adult erythroid cells by tethering and epigenetic unmasking of a silenced γ-globin gene lead to increased frequency of LCR/γ-globin contacts and reduced LCR/β-globin contacts. The outcome of these manipulations is robust, pancellular γ-globin transcription activation with a concomitant reduction in β-globin transcription. These examples show that chromosome looping may be considered a therapeutic target for gene activation in β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease.

Keywords: thalassemia, fetal hemoglobin, globin switching, enhancer, chromatin looping

Introduction

How complex organisms with diverse tissue and cell types arise from the same genome is one of the most enduring and fascinating questions in biology. Enhancers are cis-acting DNA sequences that increase the transcriptional output of genes and, in so doing, orchestrate cell specific transcriptomes that underlie development and differentiation. The spacing between enhancers and target genes can be very large when measured in the linear genome.1 However, studies examining individual gene loci and the whole genome using chromosome conformation capture (3C) and related technologies show that active enhancers exist in physical proximity to their target genes in the nuclear space, a phenomenon referred to as chromatin looping.2–4 Other studies reveal that enhancers are sites of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) recruitment and noncoding transcription.5 The mechanistic intersection of these findings in determining a unique gene expression program is unclear. How chromatin loops between enhancers and genes are formed and maintained and their relationships to the transcription apparatus and to overall genome folding are central issues to resolve. This is necessary to understand how enhancer function drives a cell and developmental stage-specific transcriptome and to harness this novel level of gene regulation for potential therapeutic purposes.

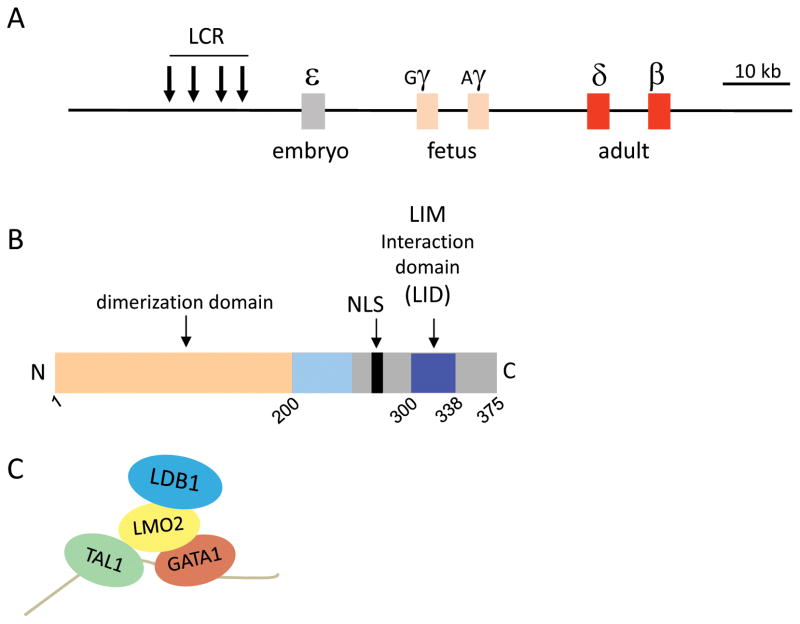

The human β-globin genes are expressed sequentially during development—from embryonic ε to fetal γ to adult δ and β—under the influence of the β-globin locus control region (LCR) enhancer, which lies at a considerable distance from the genes along chromosome 11 in humans (Fig. 1A). Expression of adult β-globin genes is correlated with silencing of fetal globin genes. Reversal of γ-globin silencing in adults is an important potential therapeutic avenue to treat hemoglobinopathies, including β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease, genetic diseases that become manifest only after the switch from γ-globin to β-globin transcription. Underlying the sequential expression of fetal γ-globin and adult β-globin genes during development is long range chromatin looping between the β-globin locus control region (LCR) enhancer and the active globin gene.6,7 Therefore, long-range chromatin looping is of fundamental interest and represents a poorly understood level at which expression of these genes may be modulated with widespread relevance to mammalian development in health and disease.

Figure 1.

Role of the LDB1 complex in regulation of expression of the β-globin genes. (A) Schematic diagram of the human β-globin gene locus. Rectangles represent genes, arrows represent DNase I–hypersensitive sites composing the LCR. (B) Domain organization of the LDB1 protein. (C) The LDB1 complex occupies chromatin by virtue of GATA1 and TAL1 binding to compound DNA motifs. These proteins are bridged by LMO2, which in turn binds to LDB1 through the LID.

In this review, we first summarize the current mechanistic understanding of the how the looping protein LDB1 functions to establish long-range communication between the LCR and the β-globin genes. We then consider two mechanisms, forced chromatin looping using an artificial LDB1-based protein and pharmacological manipulation of the β-globin epigenetic environment, to manipulate loops for a desired transcriptional outcome. We end by considering the challenges that remain to bring this novel approach to achieve a therapeutically useful outcome for β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease to fruition.

LDB1, an enhancer facilitator

Enhancers are regulatory DNA sequences that increase transcription of target genes. Enhancers are occupied by clusters of transcription factors that confer tissue specificity. The β-globin genes were the first mammalian genes for which a long-range enhancer–gene loop was shown using 3C.6 Once LCR looping had been described for the globin genes, investigations of the proteins involved in such structures followed apace. It was subsequently shown that KLF1, as well as GATA1 and its co-factor FOG1, was required for β-globin looping interactions.8,9 GATA1 and KLF1 both bind DNA and occupy the LCR and the β-globin promoter; nevertheless, the basis of the long-range looping between these sequences remained unclear. It has long been proposed that long-range interaction between genetic regulatory elements can be established and/or maintained by proteins capable of homodimerization.10 Based on studies in diverse animal models and in vitro, our interest settled on the LDB1 protein.

The highly conserved and widely expressed LIM domain–binding factor 1 (LDB1, also known as NLI), has no known enzymatic or DNA-binding activity (Fig. 1B). Intriguingly, LDB1 is the orthologue of Drosophila Chip, a protein that was cloned in a genetic screen looking for facilitators of long-range enhancer interactions.11 Moreover, LDB1 has an N-terminal dimerization domain through which it can self-interact in vitro.12–15 The LDB1 dimerization domain was shown to be important for LDB1 function in the developing nervous system in flies and vertebrates.16,17 LDB1 also has a C-terminal LIM-interaction domain (LID) through which it can interact with the diverse family of LIM-homeodomain and LIM-only proteins.

Notwithstanding broad expression of LDB1 in multiple tissues, it is required for erythropoiesis in the mouse. Ldb1−/− mice die at embryonic day 8.5 with multiple defects that include a complete absence of blood islands in the yolk sac.18 Furthermore, studies using conditional alleles of Ldb1 showed that it is required for both embryonic and adult erythropoiesis.19 Importantly, gel-shift experiments had shown that, in erythroid cell extracts, LDB1 can interact with the erythroid LIM-only protein LMO2 and with the major erythroid gene regulators and DNA binding factors GATA1 and TAL1.20 The function of such interaction was, however, unclear.

LDB1 homotypic interactions mediate β-globin locus enhancer looping

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we found that an LDB1/GATA1/TAL1/LMO2 complex occupies both the murine β-globin LCR and the β-globin gene promoter when the gene is actively transcribed in E14.5 fetal liver and in induced MEL cells.21 LMO2 provides association of LDB1 with DNA-binding factors GATA1 and TAL1 (Figure 1C). The complex binds to a compound E-box/GATA motif that is common in regulatory regions of erythroid genes, including the β-globin locus.20,22

We used the MEL cell system to investigate LDB1 function in erythroid cells, and found that reduction of LDB1 using RNA interference (RNAi) severely reduced the LCR/β-globin loops and gene transcription.21 The LDB1 complex also occupies the LCR and the γ-globin promoters that loop together in human CD34+ cells differentiated to produce high amounts of fetal hemoglobin.23 Thus, LDB1 mediates distinct chromatin loops between the LCR and active genes at the appropriate developmental stage, and LDB1 complex occupancy distinguishes active globin gene promoters. Moreover, ChIP-seq studies revealed that the LDB1 complex binds to virtually all erythroid enhancers, implying a broad role in erythropoiesis.24

LDB1 plays distinct roles in enhancer looping and transcriptional activation

During the maturation of fetal liver erythroid cells, β-globin loci migrate from the nuclear periphery to the interior of the nucleus, where they localize into foci of transcription enriched for RNA Pol II called transcription factories.25,26 3D-immuno-FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) revealed that reduction of LDB1 results in failure of the β-globin locus to migrate away from the nuclear periphery into nuclear transcription factories.27 Since LDB1 is required for both LCR looping and intranuclear migration, the question arises whether looping is necessary for intranuclear migration. Alternatively, looping might occur within transcription factories and might be mediated by Pol II density or even transcription per se.28 To directly ask whether β-globin/LCR looping requires transcription, we dissected individual subdomains of the LDB1 dimerization domain (LDB1-DD) and revealed distinct functional properties of conserved subdomains.

First, using an LDB1 knockdown-and-rescue approach in erythroid cells, we demonstrated that LDB1-DD is necessary for establishing the long-range β-globin/LCR interaction and for activation of β-globin gene expression.29 Moreover, fusion of LDB1-DD with LMO2 produced a protein that was capable of functional replacement of depleted endogenous LDB1 in LCR looping and activation of β-globin gene expression. These experiments show that the LDB1-DD is necessary and sufficient, within the LDB1 complex, for establishing the enhancer–promoter interaction in the β-globin locus. Interestingly, replacement of LDB1-DD by heterologous dimerization domains or directly fusing two LMO2 molecules yielded proteins that could not rescue looping or β-globin gene expression, hinting at the possibility that the LDB1 dimerization domain has a role in addition to its function in looping.

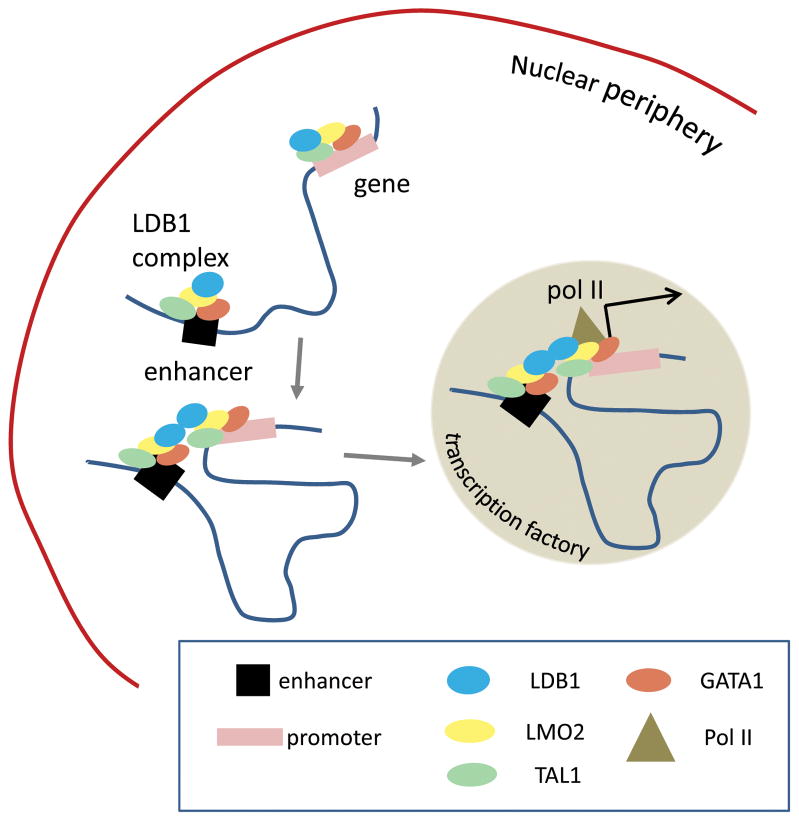

To explore this idea, we further dissected the LDB1-DD. LDB1-DD contains several evolutionarily conserved elements potentially capable of forming α-helices.29 Individual deletion of three of these elements across the N-terminal region of the LDB1-DD completely blocked LDB1 homodimerization and its ability to establish interaction between the LCR and the β-globin gene, confirming that LDB1 homodimerization is crucial for the interaction. None of these deleted forms of LDB1 rescued β-globin expression in the LDB1 knockdown background. However, we found that deletion of a small element at the C-terminal part of LDB1-DD (DD4/5) resulted in a mutated LDB1 protein capable of homodimerizing and establishing the long-range LCR interaction, but incapable of β-globin gene activation. This observation shows that transcription is not required for LCR looping, but leaves open the question of whether the looped inactive locus occupied by LDB1-DD4/5 can migrate away from the nuclear periphery. Again using 3D-immuno-FISH and ChIP assays, we found that lack of DD4/5 results in failure of the locus to migrate away from the nuclear lamina toward the nuclear interior. Moreover, RNA Pol II recruitment to the gene promoter is compromised, consistent with failure of the locus to localize within transcription factories. This observation leads to a model in which looping and transcriptional activation can be separated, in this locus, and in which looping does not require nuclear migration or transcription factory residence (Fig. 2). The phenomenon of enhancer looping before activation of target genes has recently been observed in the Drosophila embryo, however, the interactions were associated with paused RNA polymerase II, which was not the case at the β-globin locus.30

Figure 2.

Transcription-independent mechanism of enhancer–promoter interaction. Enhancer–promoter proximity is established by interaction between enhancer and promoter, each occupied by transcription factors. The looped locus then migrates to Pol II factories in the nuclear interior to achieve a high level of gene expression.

Finally, using biochemical approaches, we showed that the LDB1-DD4/5 region is critical for recruiting FOG1 protein to the LDB1 complex at the β-globin locus.29 FOG1 is required for β-globin gene promoter remodeling and RNA Pol II recruitment. Genome-wide expression analysis allowed us to identify a significant cohort of erythroid genes whose expression depends on LDB1-DD4/5 stabilization of FOG1 occupancy in chromatin. It has been shown that a mutation at the GATA-1 N-terminal zinc finger domain that ablates FOG1 interaction causes dyserythropoietic anemia.31 In view of this finding, it is interesting that almost half of LDB1-DD4/5–dependent genes are blood disease related, suggesting that FOG-1 stabilization within the LDB1 complex is a major determinant of normal expression of clinically important erythroid genes.

Collectively, these findings established LDB1 as an integrator protein providing long-range enhancer–promoter interaction as well as a transcription activation function. Importantly, our analysis shows that long-range interaction can be functionally separated from transcription activation and nuclear migration, arguing against models in which loops form owing to high levels of RNA Pol II in the vicinity of these elements or to transcription per se.28

Targeting LDB1 to the fetal globin genes in erythroid cells restructures enhancer looping

It has long been posited that reactivation of the fetal-expressed γ-globin gene in adult erythroid cells would have a positive effect on the clinical condition of patients with β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease.32 The γ-globin chains can functionally replace reduced β-globin chains in β-thalassemia and tetramerize with excess α-globin chains to produce fetal hemoglobin (HbF, α2γ2), relieving anemia. In sickle cell disease, elevated fetal hemoglobin antagonizes the polymerization of sickle hemoglobin, reducing the pathological effect this has on red blood cells. Although much research has examined γ-globin silencing, it is still incompletely understood. An important series of experiments recently revealed the transcription factor BCL11A as a bona fide γ-globin repressor and potential therapeutic target.33

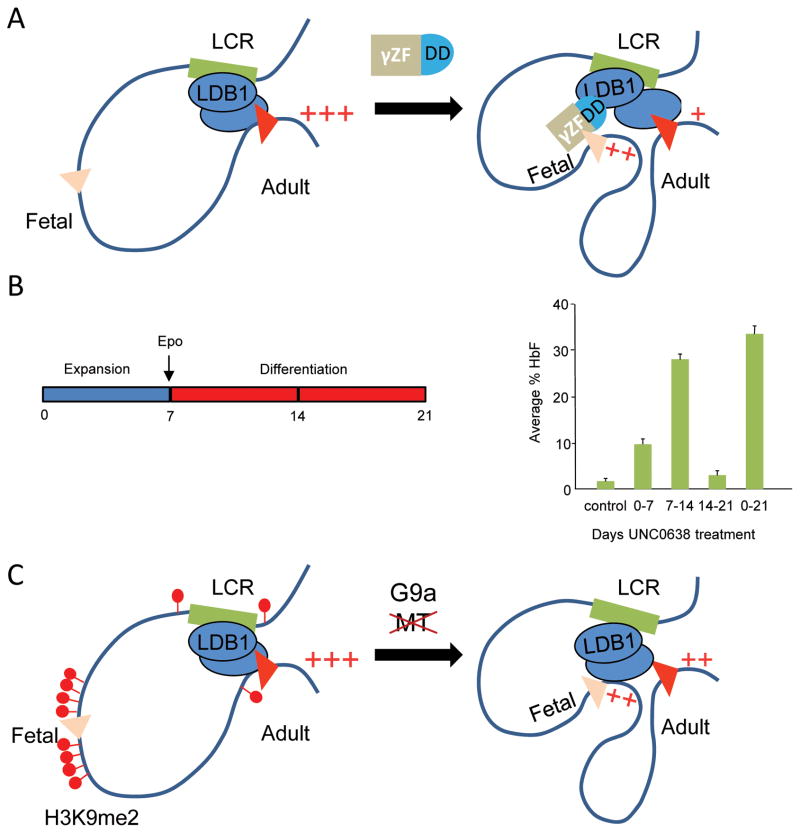

We had shown earlier that tethering the dimerization domain of LDB1 to the β-globin gene could force a loop to the LDB1-occupied LCR and partially rescue β-globin expression in immature murine erythroid cells not normally expressing the gene.34 Thus, we used a zinc-finger DNA-binding peptide (γZnF) to target the LDB1-DD to the silenced γ-globin gene promoters in human adult erythroid progenitor cells.35 As predicted from the role of the LDB1-DD in establishing long-range interactions, overexpression of a γZnF–DD fusion protein in differentiating adult hematopoetic CD34+ stem cells forced de novo loop formation between the LCR and the γ-globin genes concomitant with a decrease of interaction with the β-globin gene (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of manipulating long-range enhancer–promoter interaction to reactivate silenced fetal γ-globin gene in adult erythroid cells. (A) Model of the forced-looping approach. Artificial targeting of the LDB1 dimerization domain to the promoter of silenced γ-globin genes stimulates de novo loop formation with the LCR and reactivation of γ-globin gene expression. (B) UNC0638 treatment is most effective in raising HbF levels when carried out in the early stage of erythroid differentiation of progenitor cells. (C) Model illustrating that UNC0638 inhibition of G9a methyltransferase activity eliminates repressed chromatin from the silenced γ-globin gene promoters and stimulates LDB1 complex occupancy, de novo LCR looping, and reactivation of the expression of γ-globin genes.

γZnF-DD expression caused a strong reactivation of γ-globin gene transcription to 80% of the total γ- + β-globin mRNA, with a corresponding decrease of adult β-globin gene expression. 35 Of note, expression of numerous other erythroid genes (including GATA1, GATA2, KLF1, ERAF, BAND3, ALAS2, Spectrin, Ankyrin, and α-globin) was unaffected by the γZnF-DD protein, suggesting the specific nature of γZnF-DD reactivation of the γ-globin gene. The increase in γ-globin gene expression was associated with unchanged total hemoglobin levels and pan-cellular distribution of fetal hemoglobin in erythroblasts. HbF represented 40% of the total hemoglobin, which is more than enough to achieve therapeutic results in the β-hemoglobinopathies.36 These findings demonstrate that forced enhancer–gene looping can override stringent developmental gene silencing and suggest a novel approach to control the balance of globin gene transcription for therapeutic applications.

Pharmacological strategy for epigenetic restructuring of LCR looping

In adult erythroid cells, the γ-globin genes are silenced by diverse mechanisms, including histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2), but the underlying mechanisms are unclear.37 Previous observations suggest that G9a methyltransferase, responsible for establishing repressive H3K9me2 histone modification in euchromatin, is involved in repressing embryonic and activating adult globin gene expression in erythroid cells, implying a dual role for G9a in the regulation of β-globin genes.38 Our studies had shown a direct correlation between LDB1 distribution and active expression status of the β-globin genes.23 On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that G9a establishes repressive conditions preventing LDB1 complex occupancy at the γ-globin genes and, thus, looping to the LCR.

To examine this possibility, we used ex vivo differentiation of primary CD34+ adult human erythroid cells. We found that inhibition of G9a methyltransferase activity by the chemical compound UNC0638 resulted in a drastic increase of fetal γ-globin expression (up to 50% of total γ- + β-globin mRNA) with a corresponding decrease of adult β-globin gene expression.39,40 Inhibition of G9a methyltransferase activity did not significantly change expression of the α-globin gene or genes involved in regulation of β-globin gene expression and did not compromise cell differentiation. Reactivation of γ-globin gene expression caused significant (more that 30% of total hemoglobin) pan-cellular accumulation of fetal hemoglobin at the expense of adult hemoglobin.

Interestingly, the timing of treatment with UNC0638 was very important to the outcome of γ-globin activation in the adult erythroid cells.40 The strongest effect of the drug on the γ-globin genes and HbF production was observed when cells were treated at the time of induction of erythroid differentiation by addition of erythropoietin (Fig. 3B). In contrast, when cells were treated early, during the expansion phase of culture, there was little effect on γ-globin genes. This result could be attributed to removal of H3K9me2 from the γ-globin genes during drug treatment but re-establishment of the mark after drug removal.40 Likewise, drug treatment during the last phase of erythroid maturation failed to activate γ-globin genes. These results suggest that there is a window in early erythroid maturation when the choice of γ-globin or β-globin activation can be effectively manipulated.

UNC0638 treatment caused greatly decreased H3K9me2 histone modification across the β-globin locus, with the largest decrease seen at the γ-globin gene. In addition, redistribution of methyltransferase-inactive G9a from repressed adult β-globin to activated γ-globin genes was observed, further supporting the dual role of G9a in regulation of β-like globin gene expression.38 Notably, the LDB1 protein complex was also redistributed in the β-globin locus.40 LDB1 complex occupancy was decreased at the repressed β-globin gene and increased at the reactivated γ-globin gene. Most strikingly, shifting LDB1 complex occupancy toward the γ-globin genes caused de novo LCR/γ-globin looping at the expense of β-globin looping (Fig. 3C). These experiments show that G9a establishes epigenetic conditions repressing γ-globin genes in adult erythroid progenitor cells by preventing LCR loop formation and may be a promising target for therapies designed to ameliorate β-hemoglobinopathies.

Perspective: γ-globin repression and reactivation

Our recent work on the control of globin gene regulation, particularly on the higher-order chromatin organization of the locus, has highlighted a new approach to regulate these and other genes for potential therapeutic benefit. Reorganizing chromatin loop formation to favor LCR–γ-globin gene interactions decreases LCR–β-globin interactions, presumably attributable to the competition of these genes for the attention of the LCR. This reorganization results in increased fetal globin production concurrent with reduced adult globin production, leaving total hemoglobin levels unchanged. Pan-cellular activation of HbF after loop reorganization testifies to the robustness of this approach. These experiments constitute a proof of principle that chromatin loops can be manipulated in various ways to change gene expression, but this remains far from a therapeutic reality.

Expression of a ZnF fusion protein targeting the LCR to the γ-globin genes still depends on gene therapy technology, with the attendant risks of inefficient targeting and off-target effects. However, there is reason for optimism. First, gene therapy seeking to express the γ-globin (or β-globin) gene requires massive expression of the RNA, while expression of the γZnF peptide–LDB1 fusion protein need only be at a low level, less than 1% that of a globin gene. Second, it is estimated that levels of γ-globin expression in our experiments were achieved with only about one copy of the vector per cell. Third, γ-globin expression was quite high (80% of γ + β mRNA), suggesting that weaker promoters driving the γZnF–DD fusion protein would likely be as successful in reaching a therapeutic γ-globin production level, considered to be 30% HbF,36 with the advantage of greatly reduced off-target effects. Fourth, Zn-finger peptides are known to be very poorly immunogenic, reducing concerns about an adverse immunologic response. This approach requires further testing in animal models of β-hemoglobinopathies.

Inhibition of the methyltransferase activity of G9a by UNC0638 is highly specific to G9a.37,41 However, it cannot be used directly in clinical trials owing to poor pharmacogenetic properties. Recently, several UNC6038 derivatives with improved stability were reported, opening the possibility to test inhibition of G9a as a treatment for β-hemoglobinopathies in animal models and human subjects.41 Nevertheless, it remains to be seen how widespread the downstream effects of reduced G9a methyltransferase activity are in erythroid cells. We observed only a small delay in erythroid differentiation as measured by reduced GPA+ cells at the effective dose we tested, but this may be avoided, since lower doses are likely to be sufficient to raise γ-globin to therapeutically useful levels. The efficacy of inhibition of G9a methyltransferase activity in γ-globin induction in animals remains to be tested, but inhibition of other epigenetic modifiers, the histone demethylase LSD1 and HDAC1/2, were modestly effective in inducing HbF production (up to 1.2% and 4–16%, respectively) in a sickle cell disease mouse model and in human subjects.42,43 Interestingly, inhibition of HDAC1/2 caused conformational changes in the β-globin gene cluster similar to G9a inhibition. This suggests that the combination of G9a and HDAC1/2 inhibitors may have an enhanced effect on reactivating HbF production in adult erythroid cells, although increased side effects should also be considered.

Recent studies indicate that combinatorial use of stimulators of fetal hemoglobin that function along different pathways may have synergistic effects, although no combinatorial effect was seen in other work.42,44 Nevertheless, the possibility exists that combinations of drugs modulating the epigenetic status of γ-globin genes may yield a more prominent increase in fetal hemoglobin production. In this view, it will be important to reveal the full complement of repressive marks and repressive cofactors at the γ-globin gene in adult cells and to understand their interrelationships in order to further develop epigenetic modifiers as therapies for β-hemoglobinopathies. Together, these experiments suggest the power of harnessing and reorganizing chromatin loops to alter gene expression for therapeutic benefit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerd Blobel for stimulating discussions and the IntraMural Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institutes of Health for research support (DK 015508 to A.D.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Smallwood A, Ren B. Genome organization and long-range regulation of gene expression by enhancers. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(3):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Steensel B, Dekker J. Genomics tools for unraveling chromosome architecture. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plank JL, Dean A. Enhancer Function: Mechanistic and Genome-Wide Insights Come Together. Mol Cell. 2014;55(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stadhouders R, van den Heuvel A, Kolovos P, Jorna R, Leslie K, Grosveld F, Soler E. Transcription regulation by distal enhancers: who’s in the loop? Transcription. 2012;3(4):181–186. doi: 10.4161/trns.20720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonn S, Zinzen RP, Girardot C, Gustafson EH, Perez-Gonzalez A, Delhomme N, Ghavi-Helm Y, Wilczynski B, Riddell A, Furlong EE. Tissue-specific analysis of chromatin state identifies temporal signatures of enhancer activity during embryonic development. Nat Genet. 2012;44(2):148–156. doi: 10.1038/ng.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolhuis B, Palstra RJ, Splinter E, Grosveld F, de Laat W. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active β-globin locus. Mol Cell. 2002;10(6):1453–1465. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palstra RJ, Tolhuis B, Splinter E, Nijmeijer R, Grosveld F, de Laat W. The β-globin nuclear compartment in development and erythroid differentiation. Nat Genet. 2003;35(2):190–194. doi: 10.1038/ng1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drissen R, Palstra RJ, Gillemans N, Splinter E, Grosveld F, Philipsen S, de Laat W. The active spatial organization of the β-globin locus requires the transcription factor EKLF. Genes Dev. 2004;18(20):2485–2490. doi: 10.1101/gad.317004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vakoc CR, Letting DL, Gheldof N, Sawado T, Bender MA, Groudine M, Weiss MJ, Dekker J, Blobel GA. Proximity among distant regulatory elements at the β-globin locus requires GATA-1 and FOG-1. Mol Cell. 2005;17(3):453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Vliet PC, Verrijzer CP. Bending of DNA by transcription factors. Bioessays. 1993;15(1):25–32. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morcillo P, Rosen C, Baylies MK, Dorsett D. Chip, a widely expressed chromosomal protein required for segmentation and activity of a remote wing margin enhancer in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11(20):2729–2740. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breen JJ, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Dawid IB. Interactions between LIM domains and the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(8):4712–4717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurata LW, Pfaff SL, Gill GN. The nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI mediates homo- and heterodimerization of LIM domain transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(6):3152–3157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z, Huang S, Chang LS, Agulnick AD, Brandt SJ. Identification of a TAL1 target gene reveals a positive role for the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1 in erythroid gene expression and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(21):7585–7599. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7585-7599.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross AJ, Jeffries CM, Trewhella J, Matthews JM. LIM domain binding proteins 1 and 2 have different oligomeric states. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;399(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Meyel DJ, O’Keefe DD, Jurata LW, Thor S, Gill GN, Thomas JB. Chip and apterous physically interact to form a functional complex during Drosophila development. Mol Cell. 1999;4(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thaler JP, Lee SK, Jurata LW, Gill GN, Pfaff SL. LIM factor Lhx3 contributes to the specification of motor neuron and interneuron identity through cell-type-specific protein-protein interactions. Cell. 2002;110(2):237–249. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukhopadhyay M, Teufel A, Yamashita T, Agulnick AD, Chen L, Downs KM, Schindler A, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Dorward D, Westphal H. Functional ablation of the mouse Ldb1 gene results in severe patterning defects during gastrulation. Development. 2003;130(3):495–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Jothi R, Cui K, Lee JY, Cohen T, Gorivodsky M, Tzchori I, Zhao Y, Hayes SM, Bresnick EH, Zhao K, Westphal H, Love PE. Nuclear adaptor Ldb1 regulates a transcriptional program essential for the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(2):129–136. doi: 10.1038/ni.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadman IA, Osada H, Grutz GG, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/NLI proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16(11):3145–3157. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song S-H, Hou C, Dean A. A positive role for NLI/Ldb1 in long-range β-globin locus control region function. Mol Cell. 2007;28:810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soler E, Andrieu-Soler C, de Boer E, Bryne JC, Thongjuea S, Stadhouders R, Palstra RJ, Stevens M, Kockx C, van IW, Hou J, Steinhoff C, Rijkers E, Lenhard B, Grosveld F. The genome-wide dynamics of the binding of Ldb1 complexes during erythroid differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24(3):277–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.551810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiefer CM, Lee J, Hou C, Dale RK, Lee YT, Meier ER, Miller JL, Dean A. Distinct Ldb1/NLI complexes orchestrate gamma-globin repression and reactivation through ETO2 in human adult erythroid cells. Blood. 2011;118(23):6200–6208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-363101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Freudenberg J, Cui K, Dale R, Song SH, Dean A, Zhao K, Jothi R, Love PE. Ldb1-nucleated transcription complexes function as primary mediators of global erythroid gene activation. Blood. 2013;121:4575–4585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osborne CS, Chakalova L, Brown KE, Carter D, Horton A, Debrand E, Goyenechea B, Mitchell JA, Lopes S, Reik W, Fraser P. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nat Genet. 2004;36(10):1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/ng1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragoczy T, Bender MA, Telling A, Byron R, Groudine M. The locus control region is required for association of the murine beta-globin locus with engaged transcription factories during erythroid maturation. Genes Dev. 2006;20(11):1447–1457. doi: 10.1101/gad.1419506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song S-H, Kim A, Ragoczy T, Bender MA, Groudine M, Dean A. Multiple functions of Ldb1 required for β-globin activation during erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2010;116:2356–2364. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulger M, Groudine M. Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell. 2011;144(3):327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivega I, Dale RK, Dean A. Role of LDB1 in the transition from chromatin looping to transcription activation. Genes Dev. 2014;28(12):1278–1290. doi: 10.1101/gad.239749.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghavi-Helm Y, Klein FA, Pakozdi T, Ciglar L, Noordermeer D, Huber W, Furlong EE. Enhancer loops appear stable during development and are associated with paused polymerase. Nature. 2014;512(7512):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature13417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nichols KE, Crispino JD, Poncz M, White JG, Orkin SH, Maris JM, Weiss MJ. Familial dyserythropoietic anaemia and thrombocytopenia due to an inherited mutation in GATA1. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):266–270. doi: 10.1038/73480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sankaran VG, Xu J, Orkin SH. Advances in the understanding of haemoglobin switching. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):181–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauer DE, Orkin SH. Hemoglobin switching’s surprise: the versatile transcription factor BCL11A is a master repressor of fetal hemoglobin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;33:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng W, Lee J, Wang H, Miller J, Reik A, Gregory PD, Dean A, Blobel GA. Controlling long-range genomic interactions at a native locus by targeted tethering of a looping factor. Cell. 2012;149(6):1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng W, Rupon JW, Krivega I, Breda L, Motta I, Jahn KS, Reik A, Gregory PD, Rivella S, Dean A, Blobel GA. Reactivation of developmentally silenced globin genes by forced chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;158(4):849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinberg MH, Chui DH, Dover GJ, Sebastiani P, Alsultan A. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: a glass half full? Blood. 2014;123(4):481–485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-528067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X, Skutt-Kakaria K, Davison J, Ou YL, Choi E, Malik P, Loeb K, Wood B, Georges G, Torok-Storb B, Paddison PJ. G9a/GLP-dependent histone H3K9me2 patterning during human hematopoietic stem cell lineage commitment. Genes Dev. 2012;26(22):2499–2511. doi: 10.1101/gad.200329.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaturvedi CP, Hosey AM, Palii C, Perez-Iratxeta C, Nakatani Y, Ranish JA, Dilworth FJ, Brand M. Dual role for the methyltransferase G9a in the maintenance of beta-globin gene transcription in adult erythroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(43):18303–18308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906769106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vedadi M, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Liu F, Rival-Gervier S, Allali-Hassani A, Labrie V, Wigle TJ, Dimaggio PA, Wasney GA, Siarheyeva A, Dong A, Tempel W, Wang SC, Chen X, Chau I, Mangano TJ, Huang XP, Simpson CD, Pattenden SG, Norris JL, Kireev DB, Tripathy A, Edwards A, Roth BL, Janzen WP, Garcia BA, Petronis A, Ellis J, Brown PJ, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Jin J. A chemical probe selectively inhibits G9a and GLP methyltransferase activity in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(8):566–574. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krivega I, Byrnes C, de Vasconcellos JF, Lee YT, Kaushal M, Dean A, Miller JL. Inhibition of G9a methyltransferase stimulates fetal hemoglobin production by facilitating LCR/gamma globin looping. Blood. 2015;126:665–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu F, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Li F, Xiong Y, Korboukh V, Huang XP, Allali-Hassani A, Janzen WP, Roth BL, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of an in vivo chemical probe of the lysine methyltransferases G9a and GLP. J Med Chem. 2013;56(21):8931–8942. doi: 10.1021/jm401480r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui S, Lim KC, Shi L, Lee M, Jearawiriyapaisarn N, Myers G, Campbell A, Harro D, Iwase S, Trievel RC, Rivers A, DeSimone J, Lavelle D, Saunthararajah Y, Engel JD. The LSD1 inhibitor RN-1 induces fetal hemoglobin synthesis and reduces disease pathology in sickle cell mice. Blood. 2015;126(3):386–396. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-626259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradner JE, Mak R, Tanguturi SK, Mazitschek R, Haggarty SJ, Ross K, Chang CY, Bosco J, West N, Morse E, Lin K, Shen JP, Kwiatkowski NP, Gheldof N, Dekker J, DeAngelo DJ, Carr SA, Schreiber SL, Golub TR, Ebert BL. Chemical genetic strategy identifies histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 as therapeutic targets in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(28):12617–12622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006774107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fard AD, Hosseini SA, Shahjahani M, Salari F, Jaseb K. Evaluation of Novel Fetal Hemoglobin Inducer Drugs in Treatment of beta-Hemoglobinopathy Disorders. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2013;7(3):47–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]